14th Dalai Lama

Tenzin | |

|---|---|

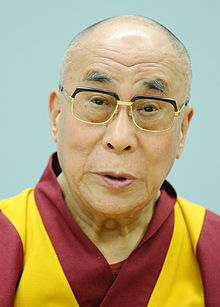

The Dalai Lama in 2013 | |

| Title | The 14th Dalai Lama |

| Personal | |

| Born | 6 July 1935 |

| Parents |

|

| Signature |  |

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Thubten Gyatso |

The 14th Dalai Lama (religious name: Tenzin Gyatso, shortened from Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, born Lhamo Dondrub,[1] 6 July 1935) is the current Dalai Lama, as well as the longest lived incumbent. Dalai Lamas are the head monks of the Gelug school, the newest of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism.[2] He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, and is also well known for his lifelong advocacy for Tibetans inside and outside Tibet.

The Dalai Lama was born in Taktser, Qinghai (known to Tibetans as Amdo),[3] and was selected as the rebirth of the 13th Dalai Lama two years later, although he was only formally recognized as the 14th Dalai Lama on 17 November 1950, at the age of 15. The Gelug school's government administered an area roughly corresponding to the Tibet Autonomous Region just as the nascent People's Republic of China wished to assert central control over it. There is a dispute over whether the respective governments reached an agreement for a joint Chinese-Tibetan administration.

During the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the Dalai Lama fled to India, where he denounced the People's Republic and established a Tibetan government in exile. He has since traveled the world, advocating for the welfare of Tibetans, teaching Tibetan Buddhism and talking about the importance of compassion as the source of a happy life. Around the world, institutions face pressure from China not to accept him. He has spoken about the environment, economics, women's rights, non-violence, interfaith dialog, physics, astronomy, reproductive health, and sexuality, along with various Mahayana and Vajrayana topics. Template:Contains Tibetan text Template:Contains Chinese text

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Early life and background

Lhamo Döndrub (or Thondup) was born on 6th July 1935 to a farming and horse trading family in the small hamlet of Taktser,[4] in the eastern border of the former Tibetan region of Amdo, then already assimilated into the Chinese province of Qinghai.[5][6] He was one of seven siblings to survive childhood. The eldest was his sister Tsering Dolma, eighteen years older. His eldest brother, Thupten Jigme Norbu, had been recognised at the age of eight as the reincarnation of the high Lama Taktser Rinpoche. His sister, Jetsun Pema, spent most of her adult life on the Tibetan Children's Villages project. The Dalai Lama's first language was, in his own words, "a broken Xining language which was (a dialect of) the Chinese language" as his family did not speak the Tibetan language.[7][8]

A search party was sent to locate the new incarnation when the boy who was to become the 14th was about two years old.[9] It is said that, amongst other omens, the head of the embalmed body of the thirteenth Dalai Lama, at first facing south-east, had mysteriously turned to face the northeast—indicating the direction in which his successor would be found. The Regent, Reting Rinpoche, shortly afterwards had a vision at the sacred lake of Lhamo La-tso indicating Amdo as the region to search—specifically a one-story house with distinctive guttering and tiling. After extensive searching, the Thondup house, with its features resembling those in Reting's vision, was finally found.

Thondup was presented with various relics, including toys, some of which had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama and some of which had not. It was reported that he had correctly identified all the items owned by the previous Dalai Lama, exclaiming, "It's mine! It's mine!"[10][11]

The Chinese Muslim General Ma Bufang did not want the 14th Dalai Lama to succeed his predecessor. Ma Bufang stationed his men to place the Dalai Lama under effective house arrest, saying it was needed for "protection", refusing to permit his leaving to Tibet.[12] He did all he could to delay the transport of the Dalai Lama from Qinghai to Tibet, by demanding massive sums of money in silver.[13] The demanded payment by Ma Bufang was 100,000 Chinese silver dollars.[14]

Lhamo Thondup was recognised formally as the reincarnated Dalai Lama and renamed Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso (Holy Lord, Gentle Glory, Compassionate, Defender of the Faith, Ocean of Wisdom) although he was not formally enthroned as the Dalai Lama until the age of 15; instead, the regent acted as the head of the Kashag until that time. Tibetan Buddhists normally refer to him as Yishin Norbu (Wish-Fulfilling Gem), Kyabgon (Saviour), or just Kundun (Presence). His devotees, as well as much of the Western world, often call him His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the style employed on the Dalai Lama's website.

Monastic education commenced at the age of six years, his principal teachers being Yongdzin Ling Rinpoche (senior tutor) and Yongdzin Trijang Rinpoche (junior tutor). At the age of 11 he met the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, who became his videographer and tutor about the world outside Lhasa. The two remained friends until Harrer's death in 2006.[15]

In 1959, at the age of 23, he took his final examination at Lhasa's Jokhang Temple during the annual Monlam or prayer Festival. He passed with honours and was awarded the Lharampa degree, the highest-level geshe degree, roughly equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy.[9][16]

Life as the Dalai Lama

Historically the Dalai Lamas had political and religious influence in the Western Tibetan area of Ü-Tsang around Lhasa, where the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism was popular and the Dalai Lamas held land under their jurisdiction. In 1939, at the age of four, the present Dalai Lama was taken in a procession of lamas to Lhasa.

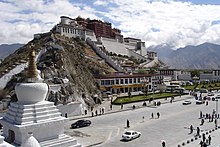

The Dalai Lama's childhood was spent between the Potala Palace and Norbulingka, his summer residence, both of which are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

China asserts that the Kuomintang government ratified the 14th Dalai Lama and that a Kuomintang representative, General Wu Zhongxin, presided over the ceremony. It cites a ratification order dated February 1940, and a documentary film of the ceremony.[17] According to Tsering Shakya, Wu Zhongxin along with other foreign representatives was present at the ceremony, but there is no evidence that he presided over it.[18] He also wrote:

"On 8 July 1949, the Kashag [Tibetan Parliament] called Chen Xizhang, the acting director of the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission office in Lhasa. He was informed that the Tibetan Government had decided to expel all Chinese connected with the Nationalist Government. Fearing that the Chinese might organize protests in the streets of Lhasa, the Kashag imposed a curfew until all the Chinese had left. This they did on 14, 17 and 20 July 1949. At the same time the Tibetan Government sent a telegram to General Chiang Kai-shek and to President Li Zongren informing them of the decision."[19]

During his reign, a border crisis erupted with the Republic of China in 1942. Under orders from the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kai-shek, Ma Bufang repaired Yushu airport to prevent Tibetan separatists from seeking independence.[citation needed] Chiang also ordered Ma Bufang to put his Muslim soldiers on alert for an invasion of Tibet in 1942.[20] Ma Bufang complied, and moved several thousand troops to the border with Tibet.[21] Chiang also threatened the Tibetans with aerial bombardment if they worked with the Japanese. Ma Bufang attacked the Tibetan Buddhist Tsang monastery in 1941.[22] He also constantly attacked the Labrang monastery.[23]

In October 1950 the army of the People's Republic of China marched to the edge of the Dalai Lama's territory and sent a delegation after defeating a legion of the Tibetan army in warlord-controlled Kham. On 17 November 1950, at the age of 15, the 14th Dalai Lama was enthroned formally as the temporal ruler of Tibet.

Cooperation and conflicts with the People's Republic of China

The Dalai Lama's formal rule was brief. He sent a delegation to Beijing, which ratified the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet.[24][25] He worked with the Chinese government: in September 1954, together with the 10th Panchen Lama he went to the Chinese capital to meet Mao Zedong and attend the first session of the National People's Congress as a delegate, primarily discussing China's constitution.[26][27] On 27 September 1954, the Dalai Lama was selected as a deputy chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress,[28][29] a post he officially held until 1964.[30]

In 1956, on a trip to India to celebrate the Buddha's Birthday, the Dalai Lama asked the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, if he would allow him political asylum should he choose to stay. Nehru discouraged this as a provocation against peace, and reminded him of the Indian Government's non-interventionist stance agreed upon with its 1954 treaty with China.[16] The CIA, with the Korean War only recently over, offered the Dalai Lama assistance. In 1956, a large rebellion broke out in eastern Kham, an ethnically Tibetan region in Sichuan province. To support the rebels, the CIA launched a covert action campaign against the Communist Chinese. A secret military training camp for the Khampa guerrillas was established at Camp Hale near Leadville, Colorado, in the U.S.[31] The guerrillas attacked Communist forces in Amdo and Kham but were gradually pushed into Central Tibet.

Exile to India

At the outset of the 1959 Tibetan uprising, fearing for his life, the Dalai Lama and his retinue fled Tibet with the help of the CIA's Special Activities Division,[32] crossing into India on 30 March 1959, reaching Tezpur in Assam on 18 April.[33] Some time later he set up the Government of Tibet in Exile in Dharamshala, India,[34] which is often referred to as "Little Lhasa". After the founding of the government in exile he re-established the approximately 80,000 Tibetan refugees who followed him into exile in agricultural settlements.[9] He created a Tibetan educational system in order to teach the Tibetan children the language, history, religion, and culture. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts was established[9] in 1959 and the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies[9] became the primary university for Tibetans in India. He supported the refounding of 200 monasteries and nunneries in an attempt to preserve Tibetan Buddhist teachings and the Tibetan way of life.

The Dalai Lama appealed to the United Nations on the rights of Tibetans. This appeal resulted in three resolutions adopted by the General Assembly in 1959, 1961, and 1965,[9] all before the People's Republic was allowed representation at the United Nations.[35] The resolutions called on China to respect the human rights of Tibetans.[9] In 1963, he promulgated a democratic constitution which is based upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, creating an elected parliament and an administration to champion his cause. In 1970, he opened the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamshala which houses over 80,000 manuscripts and important knowledge resources related to Tibetan history, politics and culture. It is considered one of the most important institutions for Tibetology in the world.[36]

International advocacy

At the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in 1987 in Washington, D.C., the Dalai Lama gave a speech outlining his ideas for the future status of Tibet. The plan called for Tibet to become a democratic "zone of peace" without nuclear weapons, and with support for human rights, that barred the entry of Han Chinese. The plan would come to be known as the "Strasbourg proposal", because the Dalai Lama expanded on the plan at Strasbourg on 15 June 1988. There, he proposed the creation of a self-governing Tibet "in association with the People's Republic of China." This would have been pursued by negotiations with the PRC government, but the plan was rejected by the Tibetan Government-in-Exile in 1991. The Dalai Lama has indicated that he wishes to return to Tibet only if the People's Republic of China agrees not to make any precondition for his return.[37] In the 1970s, the then-Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping set China's sole return requirement to the Dalai Lama as that he "must [come back] as a Chinese citizen.... that is, patriotism".[38]

The Dalai Lama celebrated his seventieth birthday on 6 July 2005. About 10,000 Tibetan refugees, monks and foreign tourists gathered outside his home. Patriarch Alexius II of the Russian Orthodox Church affirmed positive relations with Buddhists. [citation needed] Then President of the Republic of China (Taiwan), Chen Shui-bian, attended an evening celebrating the Dalai Lama's birthday at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei.[39] In October 2008 in Japan, the Dalai Lama addressed the 2008 Tibetan violence that had erupted and that the Chinese government accused him of fomenting. He responded that he had "lost faith" in efforts to negotiate with the Chinese government, and that it was "up to the Tibetan people" to decide what to do.[40]

Teaching activities

The Dalai Lama has conducted numerous public initiations in the Kalachakra, and is the author of many books, including books on the topic of Dzogchen, a practice in which he is accomplished. His teaching activities in the U.S. include the following:

In February 2007, the Dalai Lama was named Presidential Distinguished Professor at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia; it was the first time that he accepted a university appointment.[41] On his April 2008 U.S. tour, he gave lectures at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and at Colgate University (New York)[42] Later in July, the Dalai Lama gave a public lecture and conducted a series of teachings at Lehigh University (Pennsylvania).[43] On May 8, 2011, the University of Minnesota bestowed upon him their highest award, an Honorary Doctor of Letters.[44] During a return trip to Minnesota on March 2, 2014, he spoke at Macalester College which awarded him an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree.[45]

Interfaith dialogue

The Dalai Lama met with Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in 1973. He met with Pope John Paul II in 1980, 1982, 1986, 1988, 1990, and 2003. In 1990, he met in Dharamshala with a delegation of Jewish teachers for an extensive interfaith dialogue.[46] He has since visited Israel three times and met during 2006 with the Chief Rabbi of Israel. In 2006, he met privately with Pope Benedict XVI. He has met with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Robert Runcie, and other leaders of the Anglican Church in London, Gordon B. Hinckley, who at the time was the president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), as well as senior Eastern Orthodox Church, Muslim, Hindu, Jewish, and Sikh officials. The Dalai Lama is also currently a member of the Board of World Religious Leaders as part of The Elijah Interfaith Institute[47] and participated in the Third Meeting of the Board of World Religious Leaders in Amritsar, India, on 26 November 2007 to discuss the topic of Love and Forgiveness.[48]

On 6 January 2009, at Gujarat's Mahuva, the Dalai Lama inaugurated an interfaith "World Religions-Dialogue and Symphony" conference convened by Hindu preacher Morari Bapu. This conference explored "ways and means to deal with the discord among major religions", according to Morari Bapu.[49][50] He has stated that modern scientific findings should take precedence where appropriate over disproven religious superstition.[51]

On 12 May 2010, in Bloomington, Indiana (USA)[52] the Dalai Lama, joined by a panel of select scholars, officially launched the Common Ground Project,[53] which he and Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan had planned over the course of several years of personal conversations. The project is based on the book Common Ground between Islam and Buddhism.

Social stances

Abortion

The Dalai Lama has shown a nuanced and relatively flexible position on abortion. He explained that, from the perspective of the Buddhist precepts, abortion is an act of killing.[54] He has also clarified that in certain cases abortion could be considered ethically acceptable "if the unborn child will be retarded or if the birth will create serious problems for the parent", which could only be determined on a case-by-case basis.[55]

Democracy, non-violence, religious harmony, and Tibet's relationship with India

The Dalai Lama says that he is active in spreading India's message of non-violence and religious harmony throughout the world. "I am the messenger of India's ancient thoughts the world over." He has said that democracy has deep roots in India. He says he considers India the master and Tibet its disciple, as great scholars like Nagarjuna went from Nalanda to Tibet to preach Buddhism in the eighth century. He has noted that millions of people lost their lives in violence and the economies of many countries were ruined due to conflicts in the 20th century. "Let the 21st century be a century of tolerance and dialogue."[56]

In 1993, the Dalai Lama attended the World Conference on Human Rights and made a speech titled "Human Rights and Universal Responsibility".[57]

In 2001, he answered the question of a girl in a Seattle school by saying that it is permissible to shoot someone with a gun in self-defense if that person was "trying to kill you," and he emphasized that the shot should not be fatal.[58]

In May 2013, the Dalai Lama openly criticised Buddhist monks' attacks on Muslims in Myanmar saying "Really, killing people in the name of religion is unthinkable, very sad."[59]

Diet and animal welfare

“People think of animals as if they were vegetables, and that is not right. We have to change the way people think about animals. I encourage the Tibetan people and all people to move toward a vegetarian diet that doesn’t cause suffering.”

— Dalai Lama[60]

The Dalai Lama advocates compassion for animals and frequently urges people to try vegetarianism or at least reduce their consumption of meat. In Tibet, where historically meat was the most common food, most monks historically have been omnivores, including the Dalai Lamas. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama was raised in a meat-eating family but converted to vegetarianism after arriving in India, where vegetables are much more easily available. He spent many years as a vegetarian, but after contracting Hepatitis in India and suffering from weakness, his doctors ordered him to eat meat on alternating days, which he did for several years. He tried switching back to a vegetarian diet, but once again returned to limited consumption of meat. This attracted public attention when, during a visit to the White House, he was offered a vegetarian menu but declined by replying, as he is known to do on occasion when dining in the company of non-vegetarians, "I'm a Tibetan monk, not a vegetarian".[61] His own home kitchen, however, is completely vegetarian.[62]

Economics

The Dalai Lama has referred to himself as a Marxist and has articulated criticisms of capitalism.[63][64]

"I am not only a socialist but also a bit leftist, a communist. In terms of social economy theory, I am a Marxist. I think I am farther to the left than the Chinese leaders. [Bursts out laughing.] They are capitalists."[63]

He reports hearing of communism when he was very young, but only in the context of the destruction of Communist Mongolia. It was only when he went on his trip to Beijing that he learned about Marxist theory from his interpreter Baba Phuntsog Wangyal.[65] At that time, he reports, "I was so attracted to Marxism, I even expressed my wish to become a Communist Party member", citing his favorite concepts of self-sufficiency and equal distribution of wealth. He does not believe that China implemented "true Marxist policy",[66] and thinks the historical communist states such as the Soviet Union "were far more concerned with their narrow national interests than with the Workers' International".[67] Moreover, he believes one flaw of historically "Marxist regimes" is that they place too much emphasis on destroying the ruling class, and not enough on compassion.[67] Despite this, he finds Marxism superior to capitalism, believing the latter is only concerned with "how to make profits", whereas the former has "moral ethics".[68] Stating in 1993:

"Of all the modern economic theories, the economic system of Marxism is founded on moral principles, while capitalism is concerned only with gain and profitability. Marxism is concerned with the distribution of wealth on an equal basis and the equitable utilisation of the means of production. It is also concerned with the fate of the working classes—that is, the majority—as well as with the fate of those who are underprivileged and in need, and Marxism cares about the victims of minority-imposed exploitation. For those reasons the system appeals to me, and it seems fair. I just recently read an article in a paper where His Holiness the Pope also pointed out some positive aspects of Marxism."[64][67]

Environment

The Dalai Lama is outspoken in his concerns about environmental problems, frequently giving public talks on themes related to the environment. He has pointed out that many rivers in Asia originate in Tibet, and that the melting of Himalayan glaciers could affect the countries in which the rivers flow.[69] He acknowledged official Chinese laws against deforestation in Tibet, but is cynical because of possible official corruption.[70] He was quoted as saying "ecology should be part of our daily life";[71] personally, he takes showers instead of baths, and turns lights off when he leaves a room.[69] Around 2005, he started campaigning for wildlife conservation, including by issuing a religious ruling against wearing tiger and leopard skins as garments.[72][73] The Dalai Lama supports the anti-whaling position in the whaling controversy, but has criticized the activities of groups such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (which carries out acts of what it calls aggressive non-violence against property).[74] Before the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, he urged national leaders to put aside domestic concerns and take collective action against climate change.[75]

Sexuality

A monk since childhood, the Dalai Lama has said that sex offers fleeting satisfaction and leads to trouble later, while chastity offers a better life and "more independence, more freedom".[76] He has observed that problems arising from conjugal life sometimes even lead to suicide or murder.[77] He has asserted that all religions have the same view about adultery.[78]

In his discussions of the traditional Buddhist view on appropriate sexual behavior, he explains the concept of "right organ in the right object at the right time," which historically has been interpreted as indicating that oral, manual and anal sex (both homosexual and heterosexual) are not appropriate in Buddhism or for Buddhists, yet he also says that in modern times all common, consensual sexual practices that do not cause harm to others are ethically acceptable and that society should not discriminate against gays and lesbians and should accept and respect them from a secular point of view.[79] In a 1994 interview with OUT Magazine, the Dalai Lama clarified his personal opinion on the matter by saying, "If someone comes to me and asks whether homosexuality is okay or not, I will ask 'What is your companion's opinion?'. If you both agree, then I think I would say, 'If two males or two females voluntarily agree to have mutual satisfaction without further implication of harming others, then it is okay.'"[80] However, when interviewed by Canadian TV news anchor Evan Solomon on CBC News: Sunday about whether or not homosexuality is acceptable in Buddhism, the Dalai Lama responded that "it is sexual misconduct".[81] This was an echo of an earlier response in a 2004 Vancouver Sun interview when asked about homosexuality in Buddhism, where the Dalai Lama replied "for a Buddhist, the same sex, that is sexual misconduct"[82]

In his 1996 book Beyond Dogma, he described a traditional Buddhist definition of an appropriate sexual act as follows: "A sexual act is deemed proper when the couples use the organs intended for sexual intercourse and nothing else... Homosexuality, whether it is between men or between women, is not improper in itself. What is improper is the use of organs already defined as inappropriate for sexual contact."[83] He elaborated in 1997, explaining that the basis of that teaching was unknown to him. He also conveyed his own "willingness to consider the possibility that some of the teachings may be specific to a particular cultural and historic context".[84]

The Dalai Lama has expressed concern at “reports of violence and discrimination against gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people” and “urges respect, tolerance and the full recognition of human rights for all.”[85]

Women's rights

On gender equality and sexism, the Dalai Lama proclaimed at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee in 2009: "I call myself a feminist. Isn't that what you call someone who fights for women's rights?"[86]

He also said that by nature, women are more compassionate "based of their biology and ability to nurture and birth children." He called on women to "lead and create a more compassionate world," citing the good works of nurses and mothers.[87]

Health

In April 2013, at the "Culture of Compassion" event in Ebrington Square in Derry, Northern Ireland, the Dalai Lama asserted, stressing the importance of peace of mind: "Warm-heartedness is a key factor for healthy individuals, healthy families and healthy communities...Scientists say that a healthy mind is a major factor for a healthy body. If you're serious about your health, think and take most concern for your peace of mind. That's very, very important."[88]

2011 Political retirement

On May 29, 2011, the Dalai Lama retired from his political responsibilities, which he transferred to "the democratically elected leaders of the Central Tibetan Administration."[89]

Succession and reincarnation

On 24 September 2011, the Dalai Lama issued the following statement concerning his reincarnation:

When I am about ninety I will consult the high Lamas of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions, the Tibetan public, and other concerned people who follow Tibetan Buddhism, and re-evaluate whether the institution of the Dalai Lama should continue or not. On that basis we will take a decision. If it is decided that the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama should continue and there is a need for the Fifteenth Dalai Lama to be recognized, responsibility for doing so will primarily rest on the concerned officers of the Dalai Lama’s Gaden Phodrang Trust. They should consult the various heads of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions and the reliable oath-bound Dharma Protectors who are linked inseparably to the lineage of the Dalai Lamas. They should seek advice and direction from these concerned beings and carry out the procedures of search and recognition in accordance with past tradition. I shall leave clear written instructions about this. Bear in mind that, apart from the reincarnation recognized through such legitimate methods, no recognition or acceptance should be given to a candidate chosen for political ends by anyone, including those in the People’s Republic of China.[90]

On 3 October 2011, the Dalai Lama repeated his statement in an interview with Canadian CTV News. He added that Chinese laws banning the selection of successors based on reincarnation will not impact his decisions. "Naturally my next life is entirely up to me. No one else. And also this is not a political matter," he said in the interview. The Dalai Lama also added that he was not decided on whether he would reincarnate or if he would be the last Dalai Lama.[91]

Controversies

Recognition of the 17th Karmapa

A controversy associated with the Dalai Lama is the recognition of the seventeenth Karmapa. Two factions of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism have chosen two different Karmapas, leading to a deep division within the Kagyu school. The Dalai Lama has given his support to Urgyen Trinley Dorje, while supporters of Trinley Thaye Dorje claim that the Dalai Lama has no authority in the matter, nor is there a historical precedent for a Dalai Lama involving himself in an internal Kagyu dispute.[92] In his 2001 address at the International Karma Kagyu Conference, Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche—one of the four Karma Kagyu regents—accused the Dalai Lama of adopting a "divide and conquer" policy to eliminate any potential political rivalry arising from within the Kagyu school.[93] For his side, the Dalai Lama accepted the prediction letter presented by Tai Situ Rinpoche (another Karma Kagyu regent) as authentic, and therefore Tai Situ Rinpoche's recognition of Urgyen Trinley Dorje, also as correct.[94] Tibet observer Julian Gearing suggests that there might be political motives to the Dalai Lama's decision: "The Dalai Lama gave his blessing to the recognition of [Urgyen] Trinley, eager to win over the formerly troublesome sect [the Kagyu school], and with the hope that the new Karmapa could play a role in a political solution of the 'Tibet Question.' ...If the allegations are to be believed, a simple nomad boy was turned into a political and religious pawn."[95] However, according to Tsurphu Labrang, articles by Julian Gearing on this subject are biased, unverified and without crosschecking of basic facts.[96]

CIA Tibetan program

In October 1998, the Dalai Lama's administration acknowledged that it received $1.7 million a year in the 1960s from the U.S. government through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).[97] When asked by CIA officer John Kenneth Knaus in 1995 to comment on the CIA Tibetan program, the Dalai Lama replied that though it helped the morale of those resisting the Chinese, "thousands of lives were lost in the resistance" and further, that "the U.S. Government had involved itself in his country's affairs not to help Tibet but only as a Cold War tactic to challenge the Chinese."[98]

In his autobiography Freedom in Exile, the Dalai Lama criticized the CIA again for supporting the Tibetan independence movement "not because they (the CIA) cared about Tibetan independence, but as part of their worldwide efforts to destabilize all communist governments".[99]

In 1999, the Dalai Lama said that the CIA Tibetan program had been harmful for Tibet because it was primarily aimed at serving American interests, and "once the American policy toward China changed, they stopped their help".[100]

Ties to India

The Chinese press has criticized the Dalai Lama for his close ties with India. His 2010 remarks at the International Buddhist Conference in Gujarat saying that he was "Tibetan in appearance, but an Indian in spirituality" and referral to himself as a "son of India" in particular led the People's Daily to opine, "Since the Dalai Lama deems himself an Indian rather than Chinese, then why is he entitled to represent the voice of the Tibetan people?"[101] Dhundup Gyalpo of the Tibet Sun shot back that Tibetan religion could be traced back to Nalanda in India, and that Tibetans have no connection to Chinese "apart... from a handful of culinary dishes".[102] The People's Daily stressed the links between Chinese Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism and accused the Dalai Lama of "betraying southern Tibet to India".[101] Two years earlier in 2008, the Dalai Lama said for the first time that the territory, which India claims as part of Arunachal Pradesh, is part of India, citing the disputed 1914 Simla Accord.[103]

Public image

The Dalai Lama's appeal is variously ascribed to his charismatic personality, international fascination with Buddhism, his universalist values, international sympathy for the Tibetans, and western sinophobia.[104] In the 1990s, many films were released by the American film industry about Tibet, including biopics of the Dalai Lama. This is attributed to both the Dalai Lama's 1989 Nobel Peace Prize as well as to the euphoria following the Fall of Communism. The most notable films, Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet (both released in 1997), portrayed "an idyllic pre-1950 Tibet, with a smiling, soft-spoken Dalai Lama at the helm – a Dalai Lama sworn to non-violence": portrayals the Chinese government decried as ahistorical.[105] One South African official publicly criticised the Dalai Lama's politics and lamented a taboo on criticism of him, saying "To say anything against the Dalai Lama is, in some quarters, equivalent to trying to shoot Bambi".[106]

Critics of the news and entertainment media coverage of the controversy charge that feudal Tibet was not as benevolent as popularly portrayed. The penal code before 1913 included forms of judicial mutilation and capital punishment to enforce a social system controversially described as both slavery and serfdom.[107] In response, the Dalai Lama agreed many of old Tibet's practices needed reform. His predecessor had banned extreme punishments and the death penalty.[108] And he had started some reforms like removal of debt inheritance during the early years of his government under the People's Republic of China in 1951.[109]

The Dalai Lama has his own pages on Facebook.[110] and Google Plus [111]

International reception

Winning international approval is a very suitable starting point for every political activist. The Dalai Lama is aware of it and has tried to mobilize international support for Tibetan’s activities.[112] The Dalai Lama has been successful in gaining Western support for himself and the cause of greater Tibetan autonomy or independence, including vocal support from numerous Hollywood celebrities, most notably the actors Richard Gere and Steven Seagal, as well as lawmakers from several major countries.[113]

Depiction in the media

The 14th Dalai Lama has been depicted in various movies and television programs[114] including:

- Kundun, 1997 film directed by Martin Scorsese

- Seven Years in Tibet, 1997 film starring Brad Pitt and David Thewlis

- Klovn "Dalai Lama" Season 1, Episode 4 (2005)

- Red Dwarf episode "Meltdown"" (1991) [115]

- Kung Fu: The Legend Continues "Dragonswing II" (1994) and "Phoenix" (1996)

- Lil' Bush: Resident of the United States "Anthem/China"

- The Simpsons episode "Simple Simpson"

Awards and honors

The Dalai Lama has received numerous awards over his spiritual and political career.[116] In 1959, he received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership.[117]

After the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Dalai Lama the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize.[118] The Committee officially gave the prize to the Dalai Lama for "the struggle of the liberation of Tibet and the efforts for a peaceful resolution"[119] and "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi" [120] although the President of the Committee also said that the prize was intended to put pressure on China,[121] who was reportedly infuriated that the award was given to a separatist.[118]

On 28 May 2005, the Dalai Lama received the Christmas Humphreys Award from the Buddhist Society in the United Kingdom. On 22 June 2006, he became one of only five people ever to be recognised with Honorary Citizenship by the Governor General of Canada. The Dalai Lama was a 2007 recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award bestowed by American lawmakers.[122] In 2012, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Templeton Prize.[123] He later donated the entire prize money to an Indian charity, Save the Children.[124]

Publications

- Deity Yoga: In Action and Performance Tantras. Ed. Trans. Jeffrey Hopkins. Snow Lion, 1987. ISBN 978-0-93793-850-8

- Tantra in Tibet. Co-authored with Tsong-kha-pa, Jeffrey Hopkins. Snow Lion, 1987. ISBN 978-0-93793-849-2

- The Dalai Lama at Harvard. Ed. Trans. Jeffrey Hopkins. Snow Lion, 1988. ISBN 978-0-93793-871-3

- Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama, London: Little, Brown and Co., 1990, ISBN 978-0-349-10462-1

- The Path to Enlightenment. Ed. Trans. Glenn H. Mullin. Snow Lion, 1994. ISBN 978-1-55939-032-3

- Essential Teachings, North Atlantic Books, 1995, ISBN 1556431929

- The World of Tibetan Buddhism, translated by Geshe Thupten Jinpa, foreword by Richard Gere, Wisdom Publications, 1995, ISBN 0-86171-100-9

- Healing Anger: The Power of Patience from a Buddhist Perspective. Trans. Thupten Jinpa. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion ISBN 978-1-55939-073-6

- The Gelug/Kagyü Tradition of Mahamudra, co-authored with Alexander Berzin. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1997, ISBN 978-1-55939-072-9

- The Art of Happiness, co-authored with Howard C. Cutler, M.D., Riverhead Books, 1998, ISBN 978-0-9656682-9-3

- Ethics for the New Millennium, Riverhead Books, 1999, ISBN 978-1-57322-883-1

- Consciousness at the Crossroads. Ed. Zara Houshmand, Robert B. Livingston, B. Alan Wallace. Trans. Thupten Jinpa, B. Alan Wallace. Snow Lion, 1999. ISBN 978-1-55939-127-6

- Ancient Wisdom, Modern World: Ethics for the New Millennium, LIttle, Brown/Abacus Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-349-11443-9

- Dzogchen: Heart Essence of the Great Perfection, translated by Geshe Thupten Jinpa and Richard Barron, Snow Lion Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-1-55939-219-8

- The Meaning of Life: Buddhist Perspectives on Cause and Effect, Translated by Jeffrey Hopkins, Wisdom Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-0-86171-173-4

- Answers: Discussions with Western Buddhists. Ed. Trans. Jose Cabezon. Snow Lion, 2001. ISBN 978-1-55939-162-7

- The Compassionate Life, Wisdom Publications, 2001, ISBN 978-0-86171-378-3

- Violence and Compassion: Dialogues on Life Today, with Jean-Claude Carriere, Doubleday, 2001, ISBN 978-0-385-50144-6

- Essence of the Heart Sutra: The Dalai Lama's Heart of Wisdom Teachings, edited by Geshe Thupten Jinpa, Wisdom Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0-86171-284-7

- The Pocket Dalai Lama. Ed. Mary Craig. Shambhala Pocket Classics, 2002. ISBN 978-1-59030-001-5

- The Buddhism of Tibet. Ed. Trans. Jeffrey Hopkins, Anne C. Klein. Snow Lion, 2002. ISBN 978-1-55939-185-6

- The Art of Happiness at Work, co-authored with Howard C. Cutler, M.D., Riverhead, 2003, ISBN 978-1-59448-054-6

- Stages of Meditation. Trans. Ven. Geshe Lobsang Jordhen Losang Choephel Ganchenpa, Jeremy Russell. Snow Lion, 2003. ISBN 978-1-55939-197-9

- Der Weg des Herzens. Gewaltlosigkeit und Dialog zwischen den Religionen (The Path of the Heart: Non-violence and the Dialogue among Religions), co-authored with Eugen Drewermann, PhD, Patmos Verlag, 2003, ISBN 978-3-491-69078-3

- The Path to Bliss. Ed. Trans. Thupten Jinpa, Christine Cox. Snow Lion, 2003. ISBN 978-1-55939-190-0

- The Wisdom of Forgiveness: Intimate Conversations and Journeys, coauthored with Victor Chan, Riverbed Books, 2004, ISBN 978-1-57322-277-8

- The New Physics and Cosmology: Dialogues with the Dalai Lama, edited by Arthur Zajonc, with contributions by David Finkelstein, George Greenstein, Piet Hut, Tu Wei-ming, Anton Zeilinger, B. Alan Wallace and Thupten Jinpa, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-19-515994-3

- Dzogchen: The Heart Essence of the Great Perfection. Ed. Patrick Gaffney. Trans. Thupten Jinpa, Richard Barron (Chokyi Nyima). Snow Lion, 2004. ISBN 978-1-55939-219-8

- Lighting the Way. Snow Lion, 2005. ISBN 978-1-55939-228-0

- The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality, Morgan Road Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0-7679-2066-7

- How to Expand Love: Widening the Circle of Loving Relationships, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Atria Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0-7432-6968-1

- Living Wisdom with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, with Don Farber, Sounds True, 2006, ISBN 978-1-59179-457-8

- Mind in Comfort and Ease: The Vision of Enlightenment in the Great Perfection , with Patrick Gaffney, Matthieu Ricard and Richard Barron, Wisdom Publications, 2007, ISBN 978-0-86171-493-3

- The Leader's Way, co-authored with Laurens van den Muyzenberg, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-1-85788-511-8

- How to Practice: The Way to a Meaningful Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, ISBN 978-0-7434-5336-3

- Kalachakra Tantra: Rite of Initiation, edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-151-2

- The Good Heart: A Buddhist Perspective on the Teachings of Jesus, translated by Geshe Thupten Jinpa, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-138-3

- Opening the Eye of New Awareness, Translated by Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-155-0

- Imagine All the People: A Conversation with the Dalai Lama on Money, Politics, and Life as it Could Be, Coauthored with Fabien Ouaki, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-150-5

- An Open Heart, edited by Nicholas Vreeland; Little, Brown; ISBN 978-0-316-98979-4

- Practicing Wisdom: The Perfection of Shantideva's Bodhisattva Way, translated by Geshe Thupten Jinpa, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-182-6

- Tibetan Portrait: The Power of Compassion, photographs by Phil Borges with sayings by Tenzin Gyatso. ISBN 978-0-8478-1957-7

- The Heart of Compassion: A Practical Approach to a Meaningful Life, Twin Lakes, Wisconsin: Lotus Press, ISBN 978-0-940985-36-0

- My Tibet, co-authored with photographer Galen Rowell, ISBN 978-0-520-08948-8

- Sleeping, Dreaming, and Dying, edited by Francisco Varela, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-123-9

- How to See Yourself As You Really Are, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, ISBN 978-0-7432-9045-6

- MindScience: An East-West Dialogue, with contributions by Herbert Benson, Daniel Goleman, Robert Thurman, and Howard Gardner, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-066-9

- The Power of Buddhism, co-authored with Jean-Claude Carriere, ISBN 978-0-7171-2803-7

- Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World, Mariner Books, 2012, ISBN 054784428X

See also

- Dalai Lama Center for Peace and Education

- Foundation for Universal Responsibility of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

- Tibetan Resistance Since 1950

- List of peace activists

- Karuna Hospice

References

- ^ Tibetan: ལྷ་མོ་དོན་འགྲུབ་, Wylie: Lha-mo Don-'grub, Lhasa dialect: [[Help:IPA/Tibetan|[l̥ámo tʰø̃ ̀ɖup]]]; simplified Chinese: 拉莫顿珠; traditional Chinese: 拉莫頓珠; pinyin: Lāmò Dùnzhū

- ^ Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, page 129.

- ^ "From Birth to Exile | The Office of His Holiness The Dalai Lama". Dalailama.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ At the time of Tenzin Gyatso's birth, Taktser was a city located in the Chinese province of Tsinghai (Qinghai) and was controlled by Ma Lin, a warlord allied with Chiang Kai-shek and appointed as governor of Qinghai Province by the Kuomintang. See Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet. Conversations with the Dalai Lama, Grove Press: New York, 2006 ; Li, T.T. "Historical Status of Tibet", Columbia University Press, p. 179; Bell, Charles, "Portrait of the Dalai Lama", p. 399; Goldstein, Melvyn C. Goldstein, A history of modern Tibet, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet. Conversations with the Dalai Lama, Grove Press: New York, 2006.

- ^ "Brief biography, official website of the Dalai Lama". Dalailama.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet: Conversations With the Dalai Lama, p. 262 (2007) "At that time in my village", he said, "we spoke a broken Chinese. As a child, I spoke Chinese first, but it was a broken Xining language which was (a dialect of) the Chinese language." "So your first language", I responded, "was a broken Chinese regional dialect, which we might call Xining Chinese. It was not Tibetan. You learned Tibetan when you came to Lhasa." "Yes", he answered, "that is correct (...)."

- ^ The economist, Volume 390, Issues 8618-8624. Economist Newspaper Ltd. 2009. p. 144. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Profile: The Dalai Lama". BBC News. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ http://www.dalailama.com/biography/from-birth-to-exile

- ^ Tenzin Gyatso, Freedom in Exile The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), p.12

- ^ American Asiatic Association (1940). Asia: journal of the American Asiatic Association, Volume 40. Asia Pub. Co. p. 26. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein (1991). A history of modern Tibet, 1913–1951: the demise of the Lamaist state. University of California Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-520-07590-0. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Parshotam Mehra (2004). From conflict to conciliation: Tibetan polity revisited : a brief historical conspectus of the Dalai Lama-Panchen Lama Standoff, ca. 1904-1989. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 84. ISBN 3-447-04914-6. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Peter Graves (host) (26 April 2005). Dalai Lama: Soul of Tibet. A&E Television Networks. Event occurs at 08:00.

- ^ a b Marcello, Patricia Cronin (2003). The Dalai Lama: A Biography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32207-5. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Tibet during the Republic of China (1912–1949)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Shakya 1999, pp. 6–7

- ^ Tsering Shakya. (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947, pp. 7–8. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-231-11814-9.

- ^ Lin, Hsiao-ting. "War or Stratagem? Reassessing China's Military Advance towards Tibet, 1942–1943". Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ David P. Barrett, Lawrence N. Shyu (2001). China in the anti-Japanese War, 1937–1945: politics, culture and society. Peter Lang. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8204-4556-4. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ University of Cambridge. Mongolia & Inner Asia Studies Unit (2002). Inner Asia, Volume 4, Issues 1–2. The White Horse Press for the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit at the University of Cambridge. p. 204. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Paul Kocot Nietupski (1999). Labrang: a Tibetan Buddhist monastery at the crossroads of four civilizations. Snow Lion Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-55939-090-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin, Dalai Lama XIV, interview, 25 July 1981.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951, University of California Press, 1989, pp. 812–813

- ^ Goldstein, M.C., A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 2 – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1955, p. 493

- ^ Ngapoi recalls the founding of the TAR, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, China View, 30 August 2005.

- ^ Goldstein, M.C., A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 2 – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1955, p. 496

- ^ "Chairman Mao: Long Live Dalai Lama!". Voyage.typepad.com. 21 January 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Official: Dalai Lama's U.S. award not to affect Tibet's stability". 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. People's Daily. 16 October 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Tibet, the 'great game' and the CIA". Global Research.

- ^ The CIA's Secret War in Tibet, Kenneth Conboy, James Morrison, The University Press of Kansas, 2002.

- ^ Richardson (1984), p. 210.

- ^ "Witness: Reporting on the Dalai Lama's escape to India." Peter Jackson. Reuters. 27 February 2009.Witness: Reporting on the Dalai Lama's escape to India| Reuters

- ^ "Events of 1971". Year in Review. United Press International. 1971. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Library of Tibetan Works and Archives". Government of Tibet in Exile. 1997. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Interview with The Guardian, 5 September 2003

- ^ Yuxia, Jiang (1 March 2009). "Origin of the title of "Dalai Lama" and its related background". Xinhua. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "China keeps up attacks on Dalai Lama". CNN.

- ^ "Dalai Lama admits Tibet failure". Al Jazeera. 3 November 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Dalai Lama named Emory distinguished professor". News.emory.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Visits Colgate". The Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Lehigh University: His Holiness the Dalai Lama". .lehigh.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "The Dalai Lama". umn.edu. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ "His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama visits Macalester, speaks to over 3,500". http://themacweekly.com/. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Kamenetz,Rodger (1994)The Jew in the Lotus Harper Collins: 1994.

- ^ "The Elijah Interfaith Institute – Buddhist Members of the Board of World Religious Leaders". Elijah-interfaith.org. 24 December 2006. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Third Meeting of the Board of World Religious Leaders". Elijah-interfaith.org. 7 April 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Dalai Lama inaugurates 6-day world religions meet at Mahua". Indianexpress.com. 7 January 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Canada Tibet Committee. "Dalai Lama to inaugurate inter-faith conference". Tibet.ca. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Paine, Jeffery (14 September 2003). "Boston.com". The Buddha of suburbia.

- ^ "Dalai Lama, Muslim Leaders Seek Peace in Bloomington". Islambuddhism.com. 31 May 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Islam and Buddhism". Islambuddhism.com. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Gary Stivers Dalai Lama meets Idaho’s religious leaders, www.sunvalleyonline.com, 15 September 2005

- ^ Claudia Dreifus (28 November 1993). "New York Times Interview with the Dalai Lama". New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ I'm messenger of India's ancient thoughts: Dalai Lama, I'm messenger of India's ancient thoughts: The Dalai Lama – Hindustan Times, Dalai Lama Story Page – USATODAY.com, Canada Tibet Committee|Newsroom|WTN "I'm messenger of India's ancient thoughts": Dalai Lama; 14 November 2009; Itanagar. Indian Express Newspaper; Hindustan Times Newspaper; PTI News; Dalai Lama Quotes Page — USATODAY.com; Official website; Signs of change emanating within China: Dalai Lama; By Shoumojit Banerjee; 27 May 2010; The Hindu newspaper

- ^ Human Rights and Universal Responsibility[dead link]

- ^ Bernton, Hal (15 May 2001). "Dalai Lama urges students to shape the world". Archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Dalai Lama decries Buddhist attacks on Muslims in Myanmar". Reuters. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Universal Compassion Movement". Universalcompassion.org. 25 November 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Iyer 2008, p. 203

- ^ "H.H. Dalai Lama". Shabkar.org. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b "The (Justifiably) Angry Marxist: An interview with the Dalai Lama". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ a b Of course the Dalai Lama's a Marxist by Ed Halliwell, The Guardian, June 20, 2011

- ^ Dalai Lama (30 March 2014). "Condolence Message from His Holiness the Dalai Lama at the Passing Away of Baba Phuntsog Wangyal". Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ 14th Dalai Lama (27 September 1999). "Long Trek to Exile For Tibet's Apostle". Vol. 154, no. 12. Time. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Tibet and China, Marxism, Nonviolence". Hhdl.dharmakara.net. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "'Marxist' Dalai Lama criticises capitalism". London: The Sunday Telegraph. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b Morgan, Joyce (1 December 2009). "Think global before local: Dalai Lama". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Dalai Lama bemoans deforestation of Tibet". Agence France-Presse. 21 November 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "His Holiness the Dalai Lama's Address to the University at Buffalo". Archive.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Campaigns to End Wildlife Trade". ENS. 8 April 2005.

- ^ Justin Huggler (18 February 2006). "Reports Fur Flies Over Tiger Plight". New Zealand Herald.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Reminds Anti-Whaling Activists to Be Non-Violent". Tokyo. Environment News Service. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Perry, Michael (30 November 2009). "Dalai Lama says climate change needs global action". Sydney. Reuters. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Sex invariably spells trouble, says Dalai Lama

- ^ Published: 5:18 pm GMT 29 November 2008 (29 November 2008). "Sexual intercourse spells trouble, says Dalai Lama". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Dalai Lama comments on Tiger Woods' scandal". FOX Sports. 20 February 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ The Buddhist religion and homosexuality at Religioustolerance.org

- ^ OUT Magazine February/March 1994

- ^ The Huffington Post, 07/13/09, Gay Marriage: What Would Buddha Do?, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/james-shaheen/gay-marriage-what-would-b_b_230855.html

- ^ LifeSiteNews, 11/02/07/, The Dalai Lama, Like the Pope, Says Gay Sex is “Sexual Misconduct”, http://www.lifesitenews.com/news/archive/ldn/2007/nov/07110208

- ^ Beyond Dogma by the Dalai Lama

- ^ "Dalai Lama Urges 'Respect, Compassion, and Full Human Rights for All', including Gays". Conkin, Dennis. Bay Area Reporter, 19 June 1997

- ^ Press Release in WORLD, 24/04/2006, HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA ISSUES STATEMENT IN SUPPORT OF HUMAN RIGHTS OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER PEOPLE, http://ilga.org/ilga/en/article/782

- ^ Conniff, Tamara (23 September 2009). "The Dalai Lama Proclaims Himself a Feminist: Day Two of Peace and Music in Memphis". www.huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "Tamara Conniff: The Dalai Lama Proclaims Himself a Feminist: Day Two of Peace and Music in Memphis". Huffingtonpost.com. 23 September 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Posted: 04/18/2013 5:23 pm EDT (18 April 2013). "Dalai Lama 'Culture Of Compassion' Talk: Key To Good Health Is 'Peace Of Mind' (VIDEO)". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "His Holiness the Dalai Lama Ratifies Amendment to Charter of Tibetans". The Tibet Post International. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Statement of His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, on the Issue of His Reincarnation Website of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet 24 September 2011.

- ^ CTV. CTV Exclusive: Dalai Lama will choose successor. 03 Oct, 2011. http://calgary.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20111003/dalai-lama-says-he-will-choose-successor-111003/20111003/?hub=CalgaryHome

- ^ International Karma Kagyu Buddhist Organization, "An Open Letter to the Dalai Lama", 17 March 2001.

- ^ Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche, "Message to the International Karma Kagyu Conference", 2001

- ^ Vijay Kranti, "The Dalai Lama and Chinese Desperation", Border Affairs, 2001.

- ^ Julian Gearing, "The perils of taking on Tibet's holy men", Asiaweek, 20 February 2001.

- ^ "Statement from the Tsurphu Labrang regarding litigation matter". Kagyu.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "World News Briefs; Dalai Lama Group Says It Got Money From C.I.A." The New York Times. 2 October 1998.

- ^ Posted on 6 November 2008 by Kelly Wilson (6 November 2008). "Rogue State: A Guide to the World's Only Superpower". Members.aol.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mann, Jim (15 September 1998). "CIA Gave Aid to Tibetan Exiles in '60s, Files Show". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

In his 1990 autobiography, "Freedom in Exile," the Dalai Lama explained that his two brothers made contact with the CIA during a trip to India in 1956. The CIA agreed to help, "not because they cared about Tibetan independence, but as part of their worldwide efforts to destabilize all Communist governments," the Dalai Lama wrote.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Jonathan Mirsky. "Tibet: The CIA's Cancelled War". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "A look at the Dalai Lama's ridiculous Indian heart". China Tibet Information Center. 22 January 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Gyalpo, Dhundup (9 February 2010). "Why is the Dalai Lama "son of India"?". Dharamshala: Tibet Sun. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Tawang is part of India: Dalai Lama". TNN. 4 June 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ Anand, Dibyesh (15 December 2010). "The Next Dalai Lama: China has a choice". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Buckley, Michael (2006). Tibet (2 ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84162-164-7. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ Independent Online. "'I've heard him described as Buddha'". Iol.co.za. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Barnett, Robert, in: Blondeau, Anne-Marie and Buffetrille, Katia (eds). Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China’s 100 Questions (2008) University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-520-24928-8 (paper), pp. 81–83

- ^ Norbu, Thubten Jigme and Turnbull, Colin M. Tibet: An account of the history, the religion and the people of Tibet (1968) Touchstone Books. New York. ISBN 978-0-671-20559-1 pg. 317.

- ^ Johann Hari (7 June 2004). "Johann interviews the Dalai Lama". JohannHari.com.

- ^ "Dalai Lama at". Facebook.com. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Dalai Lama at". plus.google.com.

- ^ Fisher, D., Shahghasemi, E. & Heisey, D. R. (2009). A Comparative Rhetorical Analysis of the 1 4th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso. Midwest CIES 2009 Conference, Ohio, U.S.A.

- ^ Interview with CBC News, 16 April 2004

- ^ Dalai Lama (Character)

- ^ "Red Dwarf" Meltdown (1991)

- ^ "List of awards". Replay.waybackmachine.org. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "1959 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership – Dalai Lama". Replay.waybackmachine.org. 5 January 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b Cherian, John (November 2010). "Not so noble". Vol. 27, no. 23. Frontline.

- ^ "Presentation Speech by Egil Aarvik, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize goes astray". China Internet Information Center. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Knowlton, Brian (18 October 2007). "Bush and Congress Honor Dalai Lama". nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Wins 2012 Templeton Prize". Philanthropy News Daily. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ "Dalai Lama gives Templeton Prize money to Indian charity". 14 May 2010.

Bibliography

- Craig, Mary. Kundun: A Biography of the Family of the Dalai Lama (1997) Counterpoint. Calcutta. ISBN 978-1-887178-64-8

- Iyer, Pico. The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (2008) Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-38755-4

- Knaus, Robert Kenneth. Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival (1999) PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-891620-18-8

- Mullin, Glenn H. (2001). The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnation, pp. 452–515. Clear Light Publishers. Santa Fe, New Mexico. ISBN 978-1-57416-092-5.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet & Its History. 1st edition 1962. 2nd edition, Revised and Updated. Shambhala Publications, Boston. ISBN 978-0-87773-376-8 (pbk).

- Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon In The Land Of Snows (1999) Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11814-9

- United States. Congressional-Executive Commission on China. The Dalai Lama: What He Means for Tibetans Today: Roundtable before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, First Session, July 13, 2011. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., 2012.

External links

- Official website

- Collection of speeches and letters

- H.H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso – at Rigpa Wiki

- 14th Dalai Lama on Facebook

- 14th Dalai Lama on X

- Template:Google+

- A film clip "Dalai Lama Greeted By Nehru, Again Blasts Reds, 1959/04/30 (1959)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- Use dmy dates from March 2011

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 14th Dalai Lama

- 1935 births

- 20th-century Lamas

- 20th-century philosophers

- 20th-century Tibetan people

- 21st-century Tibetan people

- Buddhist feminists

- Buddhist monks from Tibet

- Buddhist pacifists

- Buddhist philosophers

- Child rulers from Asia

- Civil rights activists

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Dalai Lamas

- Humanitarians

- Indigenous activists

- Living people

- Male feminists

- Marxists

- Marxist feminists

- Members of the National People's Congress

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- Nonviolence advocates

- People from Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

- People from Haidong

- Ramon Magsaysay Award winners

- Tibetan dissidents

- Tibetan Buddhists from Tibet

- Tibet freedom activists

- Tibetan Nobel laureates

- Tibetan feminists

- Templeton Prize laureates

- Recipients of the Order of the Smile

- Nautilus Book Award winners