Yokohama

Yokohama

横浜市 | |

|---|---|

| City of Yokohama[1] | |

From top left: Minato Mirai 21, Yokohama Chinatown, Nippon Maru, Yokohama Station, Yokohama Marine Tower | |

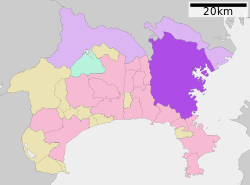

Map of Kanagawa Prefecture with Yokohama highlighted in purple | |

| Coordinates: 35°26′39″N 139°38′17″E / 35.44417°N 139.63806°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Kanagawa Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fumiko Hayashi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 437.38 km2 (168.87 sq mi) |

| Population (October 1, 2016) | |

| • Total | 3,732,616 |

| • Density | 8,534.03/km2 (22,103.0/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| – Tree | Camellia, Chinquapin, Sangoju Sasanqua, Ginkgo, Zelkova |

| – Flower | Rose |

| Address | 1-1 Minato-chō, Naka-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa-ken 231-0017 |

| Website | www |

| Yokohama | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Hiragana | よこはま | ||||

| Katakana | ヨコハマ | ||||

| Kyūjitai | 橫濱 | ||||

| Shinjitai | 横浜 | ||||

| |||||

Yokohama (Japanese: 横浜, Hepburn: Yokohama, pronounced [jokoꜜhama] ), literally "horizontal beach",[2][3] is the second largest city in Japan by population, after Tokyo, and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city of Kanagawa Prefecture. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of Tokyo, in the Kantō region of the main island of Honshu. It is a major commercial hub of the Greater Tokyo Area.

Yokohama's population of 3.7 million makes it Japan's second largest city after the special wards of Tokyo. Yokohama developed rapidly as Japan's prominent port city following the end of Japan's relative isolation in the mid-19th century, and is today one of its major ports along with Kobe, Osaka, Nagoya, Hakata, Tokyo, and Chiba.

Name meaning

Yokohama (横浜) literally means "horizontal beach".[2] The current area surrounded by Maita Park, Ōoka River and Nakamura River had been a gulf divided by a sandbar from the open sea. This sandbar was the original Yokohama fishing village. Since the sandbar protruded perpendicularly from the land, or horizontally when viewed from the sea, it was called a "horizontal beach".[3]

History

Opening of the Treaty Port (1859–1868)

Yokohama was a small fishing village up to the end of the feudal Edo period, when Japan held a policy of national seclusion, having little contact with foreigners.[4] A major turning point in Japanese history happened in 1853–54, when Commodore Matthew Perry arrived just south of Yokohama with a fleet of American warships, demanding that Japan open several ports for commerce, and the Tokugawa shogunate agreed by signing the Treaty of Peace and Amity.[5]

It was initially agreed that one of the ports to be opened to foreign ships would be the bustling town of Kanagawa-juku (in what is now Kanagawa Ward) on the Tōkaidō, a strategic highway that linked Edo to Kyoto and Osaka. However, the Tokugawa shogunate decided that Kanagawa-juku was too close to the Tōkaidō for comfort, and port facilities were instead built across the inlet in the sleepy fishing village of Yokohama. The Port of Yokohama was officially opened on June 2, 1859.[6]

Yokohama quickly became the base of foreign trade in Japan. Foreigners initially occupied the low-lying district of the city called Kannai, residential districts later expanding as the settlement grew to incorporate much of the elevated Yamate district overlooking the city, commonly referred to by English speaking residents as The Bluff.

Kannai, the foreign trade and commercial district (literally, inside the barrier), was surrounded by a moat, foreign residents enjoying extraterritorial status both within and outside the compound. Interactions with the local population, particularly young samurai, outside the settlement inevitably caused problems; the Namamugi Incident, one of the events that preceded the downfall of the shogunate, took place in what is now Tsurumi Ward in 1862, and prompted the Bombardment of Kagoshima in 1863.

To protect British commercial and diplomatic interests in Yokohama a military garrison was established in 1862. With the growth in trade increasing numbers of Chinese also came to settle in the city.[7] Yokohama was the scene of many notable firsts for Japan including the growing acceptance of western fashion, photography by pioneers such as Felice Beato, Japan's first English language newspaper, the Japan Herald published in 1861 and in 1865 the first ice cream and beer to be produced in Japan.[8] Recreational sports introduced to Japan by foreign residents in Yokohama included European style horse racing in 1862, cricket in 1863[9] and rugby union in 1866. A great fire destroyed much of the foreign settlement on November 26, 1866 and smallpox was a recurrent public health hazard, but the city continued to grow rapidly attracting both foreigners and local Japanese.

Meiji and Taisho Periods (1868–1923)

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the port was developed for trading silk, the main trading partner being Great Britain. Western influence and technological transfer contributed to the establishment of Japan's first daily newspaper (1870), first gas-powered street lamps (1872) and Japan's first railway constructed in the same year to connect Yokohama to Shinagawa and Shinbashi in Tokyo. In 1872 Jules Verne portrayed Yokohama, which he had never visited, in an episode of his widely read Around the World in Eighty Days, capturing the atmosphere of the fast-developing, internationally oriented Japanese city.

In 1887, a British merchant, Samuel Cocking, built the city's first power plant. At first for his own use, this coal-burning plant became the basis for the Yokohama Cooperative Electric Light Company. The city was officially incorporated on April 1, 1889.[10] By the time the extraterritoriality of foreigner areas was abolished in 1899, Yokohama was the most international city in Japan, with foreigner areas stretching from Kannai to the Bluff area and the large Yokohama Chinatown.

The early 20th century was marked by rapid growth of industry. Entrepreneurs built factories along reclaimed land to the north of the city toward Kawasaki, which eventually grew to be the Keihin Industrial Area. The growth of Japanese industry brought affluence, and many wealthy trading families constructed sprawling residences there, while the rapid influx of population from Japan and Korea also led to the formation of Kojiki-Yato, then the largest slum in Japan.

Great Kanto earthquake and the Second World War (1923–1945)

Much of Yokohama was destroyed on September 1, 1923 by the Great Kantō earthquake. The Yokohama police reported casualties at 30,771 dead and 47,908 injured, out of a pre-earthquake population of 434,170.[11] Fuelled by rumours of rebellion and sabotage, vigilante mobs thereupon murdered many Koreans in the Kojiki-yato slum.[12] Many people believed that Koreans used black magic to cause the earthquake. Martial law was in place until November 19. Rubble from the quake was used to reclaim land for parks, the most famous being the Yamashita Park on the waterfront which opened in 1930.

Yokohama was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again by U.S. air raids during World War II. An estimated seven or eight thousand people were killed in a single morning on May 29, 1945 in what is now known as the Great Yokohama Air Raid, when B-29s firebombed the city and in just one hour and nine minutes reduced 42% of it to rubble.[10]

Post-World War II growth

During the American occupation, Yokohama was a major transshipment base for American supplies and personnel, especially during the Korean War. After the occupation, most local U.S. naval activity moved from Yokohama to an American base in nearby Yokosuka.

The city was designated by government ordinance on September 1, 1956.[citation needed]

The city's tram and trolleybus system was abolished in 1972, the same year as the opening of the first line of Yokohama Municipal Subway.

Construction of Minato Mirai 21 ("Port Future 21"), a major urban development project on reclaimed land, started in 1983. Minato Mirai 21 hosted the Yokohama Exotic Showcase in 1989, which saw the first public operation of maglev trains in Japan and the opening of Cosmo Clock 21, then the tallest Ferris wheel in the world. The 860m-long Yokohama Bay Bridge opened in the same year.

In 1993, Minato Mirai saw the opening of the Yokohama Landmark Tower, the second tallest building in Japan.

The 2002 FIFA World Cup final was held in June at the International Stadium Yokohama.

In 2009, the city marked the 150th anniversary of the opening of the port and the 120th anniversary of the commencement of the City Administration. An early part in the commemoration project incorporated the Fourth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD IV) which was held in Yokohama in May 2008.

In November 2010, Yokohama hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting.

Geography

Climate

Yokohama features a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa) with hot and humid summers and chilly winters. Weatherwise, Yokohama has a mixed bag of rain, clouds and sun, although in winter, it is surprisingly sunny, more so than Southern Spain. Winter temperatures rarely drop below freezing, while summer can be quite warm because of the effects of humidity.[13] The coldest temperature was on 24 January 1927 when −8.2 °C (17.2 °F) was reached, whilst the hottest day was 11 August 2013 at 37.4 °C (99.3 °F). The highest monthly rainfall has been in October 2004 with 761.5 millimetres (30.0 in), closely followed by July 1941 with 753.4 millimetres (29.66 in), whilst December and January have recorded no measurable precipitation three times each.

| Climate data for Yokohama, Kanagawa (1981–2010 except for records) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.4 (99.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.9 (2.32) |

67.5 (2.66) |

140.7 (5.54) |

144.1 (5.67) |

152.2 (5.99) |

190.4 (7.50) |

168.9 (6.65) |

165.0 (6.50) |

233.8 (9.20) |

205.5 (8.09) |

107.0 (4.21) |

54.8 (2.16) |

1,688.8 (66.49) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 5 (2.0) |

6 (2.4) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

12 (4.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 6.0 | 6.7 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 11.7 | 8.7 | 12.7 | 11.5 | 8.3 | 5.5 | 119.1 |

| Average snowy days | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 53 | 54 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 64 | 56 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186.4 | 164.0 | 159.5 | 175.2 | 177.1 | 131.7 | 162.9 | 206.3 | 130.7 | 141.0 | 149.3 | 180.4 | 1,964.4 |

| Source 1: [14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [15] (records) | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Historical population

| Year of census |

Population | Rank among cities in Japan |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 422,942 | 6th, behind Kobe, Kyoto, Nagoya, Osaka, and Tokyo |

| 1925 | 405,888 | 6th |

| 1930 | 620,306 | 6th |

| 1935 | 704,290 | 6th |

| 1940 | 968,091 | 5th, surpassing Kobe |

| 1945 | 814,379 | 4th, the city government of Tokyo having been disbanded in 1943 |

| 1950 | 951,189 | 4th |

| 1955 | 1,143,687 | 4th |

| 1960 | 1,375,710 | 3rd, surpassing Kyoto |

| 1965 | 1,788,915 | 3rd |

| 1970 | 2,238,264 | 2nd, surpassing Nagoya |

| 1975 | 2,621,771 | 2nd |

| 1980 | 2,773,674 | 1st, surpassing Osaka[16] |

| 1985 | 2,992,926 | 1st |

| 1990 | 3,220,331 | 1st |

| 1995 | 3,307,136 | 1st |

| 2000 | 3,426,651 | 1st |

| 2005 | 3,579,133 | 1st |

| 2010 | 3,670,669 | 1st |

| 2015 | 3,710,824 | 1st |

Yokohama's foreign population of 92,139 includes Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, and Vietnamese.[17]

Administrative divisions

Yokohama has 18 wards (ku):

|

|

Government and politics

The Yokohama Municipal Assembly consists of 92 members elected from a total of 18 Wards. The LDP has minority control with 30 seats with Democratic Party of Japan with a close 29. The mayor is Fumiko Hayashi, who succeeded Hiroshi Nakada in September 2009.

International relations

Yokohama has sister-city relationships with 12 cities worldwide.[18]

Cebu City, Philippines

Cebu City, Philippines Constanța, Romania

Constanța, Romania Lyon, France[19]

Lyon, France[19] Manila, Philippines

Manila, Philippines Mumbai, India

Mumbai, India Odessa, Ukraine

Odessa, Ukraine San Diego, United States

San Diego, United States Seberang Perai, Malaysia[20]

Seberang Perai, Malaysia[20] Shanghai, People's Republic of China

Shanghai, People's Republic of China Frankfurt, Germany

Frankfurt, Germany Abidjan, Ivory Coast

Abidjan, Ivory Coast Vancouver, Canada[21]

Vancouver, Canada[21]

Culture

Depictions of the city in popular media

- Yukio Mishima's novel The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea is set mainly in Yokohama. Mishima describes the city's port and its houses, and the Western influences that shaped them.

- From up on Poppy Hill is a 2011 Studio Ghibli animated drama film directed by Gorō Miyazaki set in the Yamate district of Yokohama. The film is based on the serialized Japanese comic book of the same name.

- The main setting of James Clavell's book Gai-Jin is in historical Yokohama.

- Some of the events of Hitoshi Ashinano's manga Yokohama Kaidashi Kikō unfold in Yokohama and its surrounding areas.

- Aya Fuse lives in the futuristic Yokohama in Scott Westerfeld's novel Extras.

- Anne McCaffrey's Dragonriders of Pern book series involves a spaceship named the Yokohama.

- One of the Pretty Cure crossover movies takes place in Yokohama. In the fourth movie of the series, Pretty Cure All Stars New Stage: Friends of the Future, the Pretty Cure appear standing on top of the Cosmo Clock 21 in Minato Mirai.

- The main setting of the Japanese visual novel series Muv-Luv, first a school and then, in an alternate history, a military base is built in Yokohama with the objective of carrying out the Alternative IV Plan meant to save humanity.

- In Command and Conquer: Red Alert 3, Yokohama is under siege by the Soviet Union and Allied Nations to stop the Empire of The Rising Sun. The player must defend Yokohama and then lead a counterattack as the Empire.

- It is the main port used in Japan in Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days.

- It is one of the areas where players race in the arcade game Wangan Midnight Maximum Tune.

- The manga Bungo Stray Dogs is set in Yokohama.

- The Japanese mixed-media project Hamatora takes place in Yokohama.

- The final battle in Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack takes place in Yokohama.

- In My Hero Academia, it is the location of the Nomu Warehouse where they created artificial Humans (a.k.a. Nomus).

- In the animated series Girls und Panzer, the St. Gloriana Girls College is located in Yokohama.

- Sumaru City in Persona 2: Innocent Sin and Persona 2: Eternal Punishment is based on Yokohama.

Sports

- Soccer: Yokohama F. Marinos (J.League Division 1), Yokohama FC (J.League Division 2), YSCC Yokohama (J.League Division 3)

- Baseball: Yokohama DeNA BayStars

- Velodrome: Kagetsu-en Velodrome

- Basketball: Yokohama B-Corsairs

- Tennis: Ai Sugiyama

Economy and infrastructure

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

The city has a strong economic base, especially in the shipping, biotechnology, and semiconductor industries. Nissan moved its headquarters to Yokohama from Chūō, Tokyo in 2010.[22] Yokohama's GDP per capita (Nominal) was $30,625($1=\120.13).[23][24]

Transport

Yokohama is serviced by the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, a high-speed rail line with a stop at Shin-Yokohama Station. Yokohama Station is also a major station, with two million passengers daily. The Yokohama Municipal Subway, Minatomirai Line and Kanazawa Seaside Line provide metro services.

Maritime transport

Yokohama is the world's 31st largest seaport in terms of total cargo volume, at 121,326 freight tons as of 2011[update], and is ranked 37th in terms of TEUs (Twenty-foot equivalent units).[25]

In 2013, APM Terminals Yokohama facility was recognised as the most productive container terminal in the world averaging 163 crane moves per hour, per ship between the vessel's arrival and departure at the berth.[26]

Rail transport

Railway stations

- ■ East Japan Railway Company

- ■ Tōkaidō Main Line

- ■ Yokosuka Line

- – Yokohama – Hodogaya – Higashi-Totsuka – Totsuka –

- ■ Keihin-Tōhoku Line

- – Tsurumi – Shin-Koyasu – Higashi-Kanagawa – Yokohama

- ■ Negishi Line

- Yokohama – Sakuragichō – Kannai – Ishikawachō – Yamate – Negishi – Isogo – Shin-Sugita – Yōkōdai – Kōnandai – Hongōdai –

- ■ Yokohama Line

- Higashi-Kanagawa – Ōguchi – Kikuna – Shin-Yokohama – Kozukue – Kamoi – Nakayama – Tōkaichiba – Nagatsuta –

- ■ Nambu Line

- – Yakō –

- ■ Tsurumi Line

- Main Line : Tsurumi – Kokudō – Tsurumi-Ono – Bentembashi – Asano – Anzen –

- Umi-Shibaura Branch : Asano – Shin-Shibaura – Umi-Shibaura

- ■ Central Japan Railway Company

- ■ Tōkaidō Shinkansen

- – Shin-Yokohama –

- ■ Keikyu

- ■ Keikyu Main Line

- – Tsurumi-Ichiba – Keikyū Tsurumi – Kagetsuen-mae – Namamugi – Keikyū Shin-Koyasu – Koyasu – Kanagawa-Shinmachi – Naka-Kido – Kanagawa – Yokohama – Tobe – Hinodechō – Koganechō – Minami-Ōta – Idogaya – Gumyōji – Kami-Ōoka – Byōbugaura – Sugita – Keikyū Tomioka – Nōkendai – Kanazawa-Bunko – Kanazawa-Hakkei –

- ■ Keikyu Zushi Line

- Kanazawa-Hakkei – Mutsuura –

- ■ Tokyu Corporation

- ■ Tōyoko Line

- – Hiyoshi – Tsunashima – Ōkurayama – Kikuna – Myōrenji – Hakuraku – Higashi-Hakuraku – Tammachi – Yokohama

- ■ Meguro Line

- – Hiyoshi

- ■ Den-en-toshi Line

- ■ Kodomonokuni Line

- Nagatsuta – Onda – Kodomonokuni

- ■ Sagami Railway

- ■ Sagami Railway Main Line

- Yokohama – Hiranumabashi – Nishi-Yokohama – Tennōchō – Hoshikawa – Wadamachi – Kamihoshikawa – Nishiya – Tsurugamine – Futamatagawa – Kibōgaoka – Mitsukyō – Seya –

- ■ Izumino Line

- Futamatagawa – Minami-Makigahara – Ryokuentoshi – Yayoidai – Izumino – Izumi-chūō – Yumegaoka

- ■ Yokohama Minatomirai Railway

- ■ Minatomirai Line

- Yokohama – Shin-Takashima – Minato Mirai – Bashamichi – Nihon-ōdōri – Motomachi-Chūkagai

- ■ Yokohama City Transportation Bureau

- ■ Blue Line

- – Shimoiida – Tateba – Nakada – Odoriba – Totsuka – Maioka – Shimonagaya – Kaminagaya – Kōnan-Chūō – Kami-Ōoka – Gumyōji – Maita – Yoshinochō – Bandōbashi – Isezakichōjamachi – Kannai – Sakuragichō – Takashimachō – Yokohama – Mitsuzawa-shimochō – Mitsuzawa-kamichō – Katakurachō – Kishine-kōen – Shin-Yokohama – Kita Shin-Yokohama – Nippa – Nakamachidai – Center Minami – Center Kita – Nakagawa – Azamino

- ■ Green Line

- Nakayama – Kawawachō – Tsuzuki-Fureai-no-Oka – Center Minami – Center Kita – Kita-Yamata – Higashi-Yamata – Takata – Hiyoshi-Honchō – Hiyoshi

- ■ Yokohama New Transit

- ■ Kanazawa Seaside Line

- Shin-Sugita – Nambu-Shijō – Torihama – Namiki-Kita – Namiki-Chūō – Sachiura – Sangyō-Shinkō-Center – Fukuura – Shidai-Igakubu – Hakkeijima – Uminokōen-Shibaguchi – Uminokōen-Minamiguchi – Nojimakōen – Kanazawa-Hakkei

Education

Public elementary and middle schools are operated by the city of Yokohama. There are nine public high schools which are operated by the Yokohama City Board of Education,[27] and a number of public high schools which are operated by the Kanagawa Prefectural Board of Education. Yokohama National University is a leading university in Yokohama which is also one of the highest ranking national universities in Japan.

References

Citations

- ^ Yokohama official web site Template:En icon

- ^ a b [1] Japan Times, meaning of "Yokohama" is mentioned

- ^ a b [2] Yokohama City History, pg. 3

- ^ Der Große Brockhaus. 16. edition. Vol. 6. F. A. Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 1955, p. 82

- ^ "Official Yokohama city website it is fresh". City.yokohama.jp. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Arita, Erika, "Happy Birthday Yokohama!", The Japan Times, May 24, 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Fukue, Natsuko, "Chinese immigrants played vital role", Japan Times, May 28, 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Matsutani, Minoru, "Yokohama – city on the cutting edge", Japan Times, May 29, 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Galbraith, Michael (June 16, 2013). "Death threats sparked Japan's first cricket game". Japan Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Interesting Tidbits of Yokohama[History of Yokohama] Yokohama Convention & Visitors Bureau Retrieved on February 7, 2009 Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hammer, Joshua. (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II, p. 143.

- ^ Hammer, pp. 149-170.

- ^ "Yokohama Weather, When to Go and Yokohama Climate Information". world-guides.com. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ 過去の気象データ検索: 平年値(年・月ごとの値) ("Historical Climate data for Yokohama"). Japan Meteorological Agency.

- ^ 観測史上1~10位の値( 年間を通じての値). Japan Meteorological Agency.

- ^ Osaka was once more populous than Yokohama is today.

- ^ 横浜市区別外国人登録人口(平成30年3月末現在). Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Eight Cities/Six Ports: Yokohama's Sister Cities/Sister Ports". Yokohama Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ "Partner Cities of Lyon and Greater Lyon". 2008 Mairie de Lyon. Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "MPSP sets sights on city status". The Star. August 1, 2016.

- ^ "Vancouver Twinning Relationships" (PDF). City of Vancouver. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ "Nissan To Create New Global and Domestic Headquarters in Yokohama City by 2010". Japancorp.net. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "Yokohama GDP 2015".

- ^ "Yokohama 2015 population" (PDF).

- ^ "Ports & World Trade". www.aapa-ports.org.

- ^ "Chinese Ports Lead the World in Berth Productivity, JOC Group Inc. Data Shows". Press Release. AXIO Data Group. JOC Inc. June 24, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Official Yokohama city website". City.yokohama.jp. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Sources

- Hammer, Joshua (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6465-5 (cloth).

- Heilbrun, Jacob. "Aftershocks". The New York Times, September 17, 2006.

External links

- Official Website Template:Ja icon

- Yokohama Tourism Website Template:En icon

Geographic data related to Yokohama at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Yokohama at OpenStreetMap