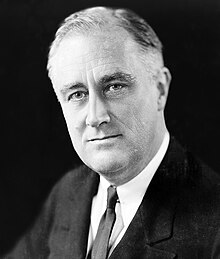

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt | |

|---|---|

| |

| 32nd President | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945 | |

| Vice President | John N. Garner (1933-1941), Henry A. Wallace (1941-1945), Harry S. Truman (1945) |

| Preceded by | Herbert Hoover |

| Succeeded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 30, 1882 Hyde Park, New York |

| Died | April 12, 1945 Warm Springs, Georgia |

| Nationality | american |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Eleanor Roosevelt |

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882 – April 12, 1945) served as the 32nd President of the United States and was elected to four terms in office. He served from 1933-1945, and is the only president to serve more than two terms. A central figure of the 20th century, scholarly surveys rank him among the greatest of U.S. Presidents.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Roosevelt championed social programs such as Social Security and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and led a substantial expansion in the role of government in the United States. He built support for his programs through his Fireside chats on radio. He slowly led the United States away from isolationism as worldwide tensions increased before World War II.

During World War II, Roosevelt, together with Winston Churchill, Charles de Gaulle and Joseph Stalin, was one of the leaders of the Allies. As the War took center stage, dynamic changes continued on the Homefront, affecting civil rights as well as the economy. As the Allies neared victory, Roosevelt played a key role in shaping the post-war world, particularly through the Yalta Conference and the creation of the United Nations. Roosevelt died on the eve of victory in World War II, and was succeeded by his Vice-President, Harry S. Truman.

Personal life

Early life

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born on January 30, 1882, in Hyde Park, in the Hudson River valley in upstate New York. His father, James Roosevelt, Sr., and his mother, Sara Ann Delano were each from wealthy old New York families. Franklin was their only child.

Roosevelt grew up in an atmosphere of privilege. Sara was an extremely possessive mother, while James was an elderly and remote father (he was 54 when Franklin was born). Sara was the dominant influence in Franklin's early years.[1] Frequent trips to Europe made Roosevelt conversant in German and French. He learned to ride, shoot, row, play polo and lawn tennis The fact that his family were Democrats, however, set him apart to some extent from most other members of the Hudson Valley aristocracy.

Roosevelt went to Groton School, an Episcopal boarding school near Boston. He was heavily influenced by the headmaster, Endicott Peabody, who preached the duty of Christians to help the less fortunate and urged his students to enter public service. Roosevelt graduated from Groton in 1900, and naturally progressed to Harvard University, where he enjoyed himself in conventional fashion and graduated with an A.B. (arts degree) in 1904 without much serious study. His academic studies were secondary to his work in the Crimson, the school newspaper. He received C+ grades while at Harvard (Conrad Sandelman). While he was at Harvard, Theodore Roosevelt became President and his vigorous leadership style and reforming zeal made him Franklin's role model. In 1903 he met his future wife Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Theodore's niece, at a White House reception. (They had previously met as children, but this was their first serious encounter.) They would marry two years later in 1905.

Roosevelt next attended Columbia Law School. He passed the bar exam and completed the requirements for a law degree in 1907 but did not bother to attend graduation. In 1908 he took a job with the prestigious Wall Street firm of Carter, Ledyard and Milburn, dealing mainly with corporate law.

Marriage and family life

Franklin was engaged to his distant cousin, Eleanor, despite the fierce resistance of Sara Delano Roosevelt. Standing in for his deceased brother, Elliott, Eleanor's uncle Theodore gave away the bride, marrying on March 17, 1905, and the young couple moved into a house bought for them by Sara, who became a frequent house-guest, much to Eleanor's mortification. Roosevelt was a charismatic, handsome, and socially active man. In contrast, Eleanor was painfully shy and hated social life, and at first she desired nothing more than to stay at home and raise Franklin's children. They had six in rapid succession:

- Anna Eleanor (1906–1975).

- James (1907–1991).

- Franklin Delano, Jr. (March, 1909–November, 1909).

- Elliott (1910–1990),

- a second Franklin Delano, Jr. (1914–1988),

- John Aspinwall (1916–1981).

The five surviving Roosevelt children all led tumultuous lives overshadowed by their famous parents. They had among them fifteen marriages, ten divorces and twenty-nine children. All four sons were officers in World War II and were decorated, on merit, for bravery. Their postwar careers, whether in business or politics, were disappointing. Two of them were elected briefly to the House of Representatives but none were elected to higher office despite several attempts.

Roosevelt soon found romantic outlets outside his marriage. One of these was Eleanor's social secretary Lucy Mercer, with whom Roosevelt began an affair soon after she was hired in early 1914. In September, 1918, Eleanor found letters in Franklin's luggage which revealed the affair. Eleanor was both mortified and angry, and confronted him with the letters, demanding a divorce. While the marriage survived, Eleanor established a separate house in Hyde Park at Valkill, and Franklin and Eleanor relationship often seemed more like that of friends and political colleagues living separate lives.

Paralysis

In August 1921, while the Roosevelts were vacationing at Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Roosevelt contracted an illness characterized, believed to be polio, which resulted in Roosevelt's total and permanent paralysis from the waist down. For the rest of his life, Roosevelt refused to accept that he was permanently paralyzed. He tried a wide range of therapies, including hydrotherapy, and in 1926, he bought a resort at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he founded a hydrotherapy center for the treatment of polio patients which still operates as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation. After, he became President, he helped to found the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the March of Dimes).

At a time when media intrusion in the private lives of public figures was much less intense than it is today, Roosevelt was able to convince many people that he was in fact getting better, which he believed was essential if he was to run for public office again. Fitting his hips and legs with iron braces, he laboriously taught himself to walk a short distance by swiveling his torso while supporting himself with a cane. In private he used a wheelchair, but he was careful never to be seen in it in public. He usually appeared in public standing upright, supported on one side by an aide or one of his sons.

Early political career

State Senator

In 1910 Roosevelt ran for the New York State Senate from the district around Hyde Park, which had not elected a Democrat since 1884. The Roosevelt name, Roosevelt money and the Democratic landslide that year carried him to the state capital of Albany, where he became a leader of a group of reformers who opposed Manhattan's Tammany Hall machine which dominated the state Democratic Party. Roosevelt soon became a popular figure among New York Democrats.

Roosevelt took the position as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson in 1912. In 1914 he was defeated in the Democratic primary for the United States Senate by Tammany Hall-backed James W. Gerard. From 1913 and 1917 Roosevelt worked to expand the Navy and founded the United States Navy Reserve. Wilson sent the Navy and Marines to intervene in Central American and Caribbean countries. Roosevelt personally wrote the constitution which the U.S. imposed on Haiti in 1915.

Roosevelt developed a life-long affection for the Navy. He showed great administrative talent, and quickly learned to negotiate with Congressional leaders and other government departments to get budgets approved. He became an enthusiastic advocate of the submarine, and also of means to combat the German submarine menace to Allied shipping: he proposed building a mine barrage across the North Sea from Norway to Scotland. In 1918 he visited the United Kingdom and France to inspect American naval facilities—during this visit he met Winston Churchill for the first time. With the end of the war in November 1918, he was in charge of demobilization, although he opposed plans to completely dismantle the Navy.

Campaign for Vice-President and return to legal practice

The 1920 Democratic National Convention chose Roosevelt as the candidate for Vice-President of the United States on the ticket headed by Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, helping build a national base. The Cox-Roosevelt ticket was heavily defeated by Republican Warren Harding in the United States presidential election, 1920. Roosevelt then retired to a New York legal practice, but few doubted that he would soon run for public office again.

Governor of New York, 1928-1932

By 1928 Roosevelt believed he had recovered sufficiently to resume his political career. He had been careful to maintain his contacts in the Democratic Party, and had allied himself with Alfred E. Smith, the current Governor and the Democratic Party Presidential Nominee in 1928.

To gain the Democratic nomination for the election, Roosevelt had to make his peace with Tammany Hall, which he did with some reluctance. Roosevelt was elected Governor by a narrow margin, and came to office in 1929 as a reform Democrat. As Governor, he established a number of new social programs, and began gathering the team of advisors he would bring with him to Washington four years later, including Frances Perkins and Harry Hopkins.

The main weakness of Roosevelt gubernatorial administration was the corruption of the Tammany Hall machine in New York City. Roosevelt had made his name as an opponent of Tammany, but needed the machine's goodwill to be re-elected in 1930. As the 1930 election approached, Roosevelt set up a judicial investigation into the corrupt sale of offices. In 1930 Roosevelt was elected to a second term by a margin of more than 700,000 votes, defeating Republican Charles H. Tuttle.

Election as President, 1932

Roosevelt's strong base in the largest state made him an obvious candidate for the Democratic nomination, which was hotly contested since it seemed clear that Hoover would be defeated at the 1932 presidential election. Al Smith was supported by some city bosses, but had lost control of the New York Democratic party to Roosevelt. Roosevelt built his own national coalition with allies such as newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Irish leader Joseph P. Kennedy, and California leader William G. McAdoo. When Texas leader John Nance Garner switched to FDR, he was given the vice presidential nomination.

Roosevelt campaigned on the Democratic platform advocating "immediate and drastic reductions of all public expenditures," "abolishing useless commissions and offices, consolidating bureaus and eliminating extravagances reductions in bureaucracy," and for a "sound currency to be maintained at all hazards."[2] Toward the end of his campaign he called to "Stop the deficits!" and said, "Before any man enters my cabinet he must give me a twofold pledge: absolute loyalty to the Democratic platform and especially to its economy plank."[3] In a criticism of Hoover, he said, "I accuse the President of being the greatest spending administration in peace time in all American history --one which piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission… We are spending altogether too much money for government services which are neither practical or necessary." [4] He said in a radio address, "Let us have the courage to stop borrowing to meet continuing deficits...Revenues must cover expenditures by one means or another. Any government, like any family, can, for a year, spend a little more than it earns. But you know and I know that a continuation of that habit means the poorhouse."[5]

The election campaign was conducted under the shadow of the Great Depression. On September 23, Roosevelt made the gloomy evaluation that, "Our industrial plant is built; the problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt. Our last frontier has long since been reached." [6] Hoover damned that pessimism as a denial of "the promise of American life . . . the counsel of despair." [7] On October 19, he attacked Hoover's deficits and called for sharp reductions in government spending. Economist Marriner Eccles observed that "given later developments, the campaign speeches often read like a giant misprint, in which Roosevelt and Hoover speak each other's lines." (Kennedy, 102) The prohibition issue solidified the wet vote for Roosevelt, who noted that repeal would bring in new tax revenues. During the campaign, Roosevelt said: "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people", coining a slogan that was later adopted for his legislative program. [8] Roosevelt did not put forward clear alternatives to the policies of the Hoover Administration, but won 57% of the vote and carried all but six states. After the election, Roosevelt refused Hoover's requests for a meeting to come up with a joint program to stop the downward spiral. In February 1933, an assassin, Giuseppe Zangara, fired five shots at Roosevelt, missing him but killing the mayor Anton Cermak of Chicago.

First term, 1933-1937

When Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933, the U.S. was at the nadir of the worst depression in its history. A quarter of the workforce was unemployed. Farmers were in deep trouble as prices fell by 60%. Industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929. In a country with limited government social services outside the cities, two million were homeless. The banking system had collapsed completely. Historians later categorized Roosevelt's program as "relief, recovery and reform." [9]

Relief was urgently needed by tens of millions of unemployed. Recovery meant boosting the economy back to normal. Reform meant long-term fixes of what was wrong, especially with the financial and banking systems. Roosevelt's series of radio speeches, known as Fireside Chats, presented his proposals directly to the American public.

First New Deal, 1933-1934

Roosevelt's "First 100 Days" concentrated on the first part of his strategy: immediate relief. From March 9 to June 16, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt sent Congress a record number of bills, all of which passed easily. To actually propose programs Roosevelt relied on leading senators such as George Norris, Robert F. Wagner and Hugo Black, as well as his own Brain Trust of academic advisers. Like Hoover he saw the Depression as partly a matter of confidence, caused in part by people no longer spending or investing because they were afraid to do so. He therefore set out to restore confidence through a series of dramatic gestures.

FDR's natural air of confidence and optimism did much to reassure the nation.[citation needed] His inauguration on March 4, 1933 occurred in the middle of a bank panic -- hence the backdrop for his famous words: "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself." The very next day he announced a plan to allow banks to reopen, which they largely did by the end of the month. This was his first proposed step to recovery.

- Relief measures included the continuation of Hoover's major relief program for the unemployed under the new name, Federal Emergency Relief Administration. The most popular of all New Deal agencies -- and Roosevelt's favorite -- was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which hired 250,000 unemployed young men to work on rural local projects. Congress also gave the Federal Trade Commission broad new regulatory powers, and provided mortgage relief to millions of farmers and homeowners. Roosevelt expanded reliance on a Hoover agency, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Roosevelt made agriculture relief a high priority and set up the first Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The AAA tried to force higher prices for commodities by paying farmers to take land out of crops and cutting herds.

- Reform of the economy was the goal of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933. It tried to end cutthroat competition by forcing industries to come up with codes that established the rules of operation for all firms within specific industries, such a minimum prices, agreements not to compete, and production restrictions. Firms and workers negotiated the codes which were then presented for approval by Roosevelt. A condition for approval was that that the industry raise wages. Provisions encouraged unions and suspended anti-trust laws. The NIRA was found to be unconstitutional by unanimous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court on May 27, 1935. Roosevelt opposed the decision, saying "The fundamental purposes and principles of the NIRA are sound. To abandon them is unthinkable. It would spell the return to industrial and labor chaos."[10] In 1933 major new banking restrictions were passed and in 1934 the Securities and Exchange Commission was created to regulate Wall Street, with 1932 campaign fund raiser Joseph P. Kennedy in charge.

- Recovery was pursued through "pump-priming" (that is, federal spending). The NIRA included $3.3 billion of spending through the PWA to stimulate the economy, which was to be handled by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes. Roosevelt worked with Republican Senator George Norris to create the largest government-owned industrial enterprise in American history, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which built dams and power stations, controlled floods, and modernized agriculture and home conditions in the poverty-stricken Tennessee Valley. The repeal of prohibition also brought in new tax revenues and helped him keep a major campaign promise.

Roosevelt tried to keep his campaign promise by cutting the regular federal budget, including 40% cuts to veterans' benefits and cuts in overall military spending. He removed 500,000 veterans and widows from the pension rolls, and slashed benefits for the remainder. A storm of protest erupted, led by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Roosevelt held his ground, but when the angry veterans formed a coalition with Senator Huey Long and passed a huge Bonus Bill over his veto, he was defeated. He succeeded in cutting federal salaries and the military and naval budgets. He reduced spending on research and education -- there was no New Deal for science until World War II began.

Second New Deal 1935-1936

After the 1934 Congressional elections, which gave Roosevelt large majorities in both houses, there was a fresh surge of New Deal legislation. These measures included the WPA which set up a national relief agency that employed two million unemployed family heads. The Social Security Act (SSA), established Social Security and promised economic security for the elderly, the poor and the sick. Senator Robert Wagner wrote the Wagner Act, officially the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which established the federal rights of workers to organize unions, to engage in collective bargaining, and to take part in strikes.

While the First New Deal of 1933 had broad support from most sectors, the Second New Deal challenged the business community. Conservative Democrats, led by Al Smith, fought back with the American Liberty League, but it failed to mobilize much grass roots support. By contrast, the labor unions, energized by the Wagner Act, signed up millions of new members and became a major backer of Roosevelt's reelection. (David Snowden)

Economic environment

Government spending increased from 8.0% of GNP under Hoover in 1932 to 10.2% of GNP in 1936. Because of the depression, the national debt as a % of GNP had doubled under Hoover from 16% to 33.6% of GNP in 1932. While Roosevelt balanced the "regular" budget, the emergency budget was funded by debt, which increased to 40.9% in 1936, and then remained level until World War II. [Historical Statistics (1976) series Y457, Y493, F32]

Deficit spending had been recommended by some economists, most notably by John Maynard Keynes of Britain. Some economists in retrospect have argued that the NRA and AAA were ineffective policies because they relied on price fixing. [Parker] The GNP was 34% higher in 1936 than 1932, and 58% higher in 1940 on the eve of war. That is, the economy grew 58% from 1932 to 1940 in 8 years of peacetime, and then grew 56% from 1940 to 1945 in 5 years of wartime. However, the economic recovery did not absorb all the unemployment he inherited. In his first term unemployment fell by two-thirds from 25% when he took office to 9.1% in 1937, but then stayed stubbornly high until it vanished during the war. (Smiley 1983)

During the war the economy operated under so many different conditions that comparison is impossible with peacetime. However, Roosevelt saw the New Deal policies as central to his legacy, and in his 1944 State of the Union speech, advocated that American's think of basic economic rights as a Second Bill of Rights.

The U.S. economy grew rapidly during Roosevelt's term. [11] However, coming out of the depression, this growth was accompanied by continuing high levels of unemployment, as the median joblessness rate during the New Deal was 17.2 percent. Through his entire term, including the war years, average unemployment was 13%. [12] [13] Total employment during Roosevelt's term expanded by 18.31 million jobs, with an average annual increase in jobs during his adminstration of 5.3%. [14]

Roosevelt's administration also saw significant changes to the Income tax in the American tax system. Just prior to Roosevelt's election in 1932, the Hoover administration passed the Revenue Act of 1932, increasing the top marginal tax rate on individual income from 25% to 63% and enacting a wide range of additional excise taxes. In 1936, the Roosevelt administration added a higher top rate of 79% on individual income greater than $5 million, which was increased again in 1939. More During World War II the top marginal tax rate was moved up to 91%. More significantly for most Americans, the overall rate structure was heavily compressed in 1943, with the highest rate was made applicable to individuals with income of $200,000 or more, and withholding taxes were introduced.

Foreign policy

The rejection of the League of Nations treaty in 1919 marked the dominance of isolationism from world organizations in American foreign policy. Despite Roosevelt's Wilsonian background, he and his Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment. The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the Good Neighbor Policy, a re-evaluation of American policy towards Latin America, which ever since the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 had been seen as an American sphere of influence. American forces were withdrawn from Haiti, and new treaties with Cuba and Panama ended their status as American protectorates. In December 1933, Roosevelt signed the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries.

Second term, 1937-1941

In the 1936 presidential election, Roosevelt campaigned on his New Deal programs against Kansas governor Alfred Landon, who accepted much of the New Deal but objected that it was hostile to business and involved too much waste. Roosevelt and Garner won 61% of the vote and carried every state except Maine and Vermont. The New Deal Democrats won even larger majorities in Congress. Roosevelt was backed by a coalition of voters which included traditional Democrats across the country, small farmers, the "Solid South", Catholics, big city machines, labor unions, northern African-Americans, Jews, intellectuals and political liberals. This coalition, frequently referred to as the New Deal coalition, remained largely intact for the Democratic Party until the 1960s.

In dramatic contrast to the first term, very little major legislation was passed in the second term. There was a United States Housing Authority (1937), a second Agricultural Adjustment Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which created the minimum wage. When the economy began to deteriorate again in late 1937, Roosevelt responded with an aggressive program of stimulation, asking Congress for $5 billion for WPA relief and public works.

The United States Supreme Court was the main obstacle to Roosevelt's programs during his first term. During 1935 the Court ruled that the National Recovery Act was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the president. It also ruled that some other pieces of New Deal legislation were unconstitutional. In addition, the Court reversed the President’s dismissal of William E. Humphrey from the Federal Trade Commission. The decision on Humphrey "is said to have nettled the President more than any other, but when he held a lengthy press conference and denounced the Supreme Court for taking the country back to a "horse-and-buggy" concept of interstate commerce it was the NRA decision that he had in mind." Roosevelt, upset at these rulings, called the Supreme Court justices "nine old men." He then proposed a "persistent infusion of new blood" by enlarging the Court so that he could appoint more sympathetic judges.[15] This "court packing" plan ran into intense political opposition from his own party, since it seemed to upset the separation of powers which is one of the cornerstones of the American constitutional structure. Roosevelt was forced to abandon the plan, but the Court also drew back from confrontation with the administration by finding the Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act to be constitutional. Deaths and retirements on the Supreme Court soon allowed Roosevelt to make his own appointments to the bench. Between 1937 and 1941 he appointed eight justices to the court, including Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black and William O. Douglas.

Determined to overcome the opposition of conservative Democrats in Congress (mostly from the South), Roosevelt involved himself in the 1938 Democratic primaries, actively campaigning for challengers who were more supportive of New Deal reform. His targets denounced Roosevelt for trying to take over the Democratic party and used the argument they were independent to win reelection. Roosevelt only defeated one target, a conservative Democrat from New York City. The Southern Congressmen forged a Conservative coalition with congressional Republicans, virtually ending Roosevelt's ability to get his domestic proposals enacted into law. The minimum wage law of 1938 was the last substantial New Deal reform act passed by Congress.

The rise to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany aroused fears of a new world war. In 1935, at the time of Italy's invasion of Abyssinia, Congress passed the Neutrality Act, applying a mandatory ban on the shipment of arms from the U.S. to any combatant nation. Roosevelt opposed the act on the grounds that it penalized the victims of aggression such as Abyssinia, and that it restricted his right as President to assist friendly countries, but public support was overwhelming so he signed it. In 1937 Congress passed an even more stringent Act, but when the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937 public opinion favored China and Roosevelt found various ways to assist China.

In October 1937 he gave the Quarantine Speech aiming to contain aggressor nations. He proposed that warmongering states be treated as a public health menace and be "quarantined." Meanwhile he secretly stepped up a program to build very long range submarines that could blockade Japan. When World War II broke out in 1939, Roosevelt rejected the Wilsonian neutrality stance and sought ways to assist Britain and France militarily. He began a regular secret correspondence with Winston Churchill discussing ways of supporting Britain.

Roosevelt turned for foreign policy advice to Harry Hopkins. They sought innovative ways to help the United Kingdom, whose financial resources were exhausted by the end of 1940. Congress, where isolationist sentiment was in retreat, passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, allowing America to "lend" huge amounts of military equipment in return for "leases" on British naval bases in the Western Hemisphere. In sharp contrast to the loans of World War I, there would be no repayment after the war. The United Kingdom agreed to dismantle preferential trade arrangements that kept American exports out of the British Empire. This underlined the point that the war aims of the U.S. and the United Kingdom were not the same. Roosevelt was a lifelong free trader and anti-imperialist, and ending European colonialism was one of his objectives. Roosevelt forged a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became British Prime Minister in May 1940.

In May 1940, a stunning German blitzkrieg overran Scandinavia, the Low countries and France, leaving Britain vulnerable to invasion. Roosevelt was determined to defend Britain and sought to shift public opinion. He supported a new group, the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, and appointed two interventionist Republican leaders, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy respectively. The fall of Paris shocked American opinion, and isolationist sentiment declined. Both parties gave support to his plans to rapidly build up the American military, but the remaining isolationists bitterly denounced Roosevelt as an irresponsible, ruthless warmonger. He successfully urged Congress to enact the first peacetime draft in United States history in 1940 (it was renewed in 1941 by one vote in Congress).

Roosevelt used his personal charisma to build support for intervention. America should be the "Arsenal of Democracy," he told his fireside audience. In August, Roosevelt openly defied the Neutrality Acts with the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, which gave 50 American destroyers to the United Kingdom and Canada in exchange for base rights in the British Caribbean islands. This was a precursor of the March 1941 Lend-Lease agreement which began to direct massive military and economic aid to the United Kingdom.

Third term, 1941-1945

The two-term tradition had been an unwritten rule since George Washington declined to run for a third term in the 1790s, but Roosevelt, after blocking the presidential ambitions of cabinet members Jim Farley and Cordell Hull, decided to run for a third term. In his campaign against Republican Wendell Willkie, Roosevelt stressed both his proven leadership experience and his intention to do everything possible to keep the United States out of war. Roosevelt won the 1940 election with 55% of the popular vote and 38 of the 48 states. A shift to the left within the Administration was shown by naming Henry A. Wallace as his Vice-President in place of the conservative Texan John Nance Garner, a bitter enemy of Roosevelt after 1937.

Roosevelt's third term was dominated by World War II, in Europe and in the Pacific. Facing strong isolationist sentiment from leaders like Senators William Borah and Robert Taft who supported re-armament, Roosevelt slowly began re-armament in 1938. By 1940 it was in high gear, with bipartisan support, partly to expand and re-equip the United States Army and Navy and partly to become the "Arsenal of Democracy" supporting the United Kingdom, France, China and (after June 1941), the Soviet Union. As Roosevelt took a firmer stance against the Axis powers, American isolationists, including Charles Lindbergh and America First attacked the president as an irresponsible warmonger. Unfazed by these criticisms and confident in the wisdom of his foreign policy initiatives, FDR continued his twin policies of preparedness and aid to the Allied coalition. On December 29, 1940, he delivered his Arsenal of Democracy Fireside chat, making the case for involvement directly to the American people, and a week later he delivered his famous Four Freedoms speech in January 1941, further laying out the case for an American defense of basic rights throughout the world.

In 1937, Roosevelt had cut funding on the New Deal, and unemployment was rising rapidly. Soon after, World War II broke out, creating new jobs and forcing industries to increase manufacturing. By 1941 unemployment had fallen to under 1 million. There was a growing labor shortage in all the nation's major manufacturing centers, accelerating the Great Migration of African-American workers from the Southern states, and of underemployed farmers and workers from all rural areas and small towns. The "Homefront" was subject to dynamic social changes throughout the war, though domestic issues were no longer Roosevelt's most urgent policy concerns.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to the Soviets. During 1941 Roosevelt also agreed that the U.S. Navy would escort Allied convoys as far east as Iceland, and would fire on German ships or submarines if they attacked Allied shipping within the U.S. Navy zone. Moreover, by 1941, U.S. Navy aircraft carriers were secretly ferrying British fighter planes between the U.K. and the Mediterranean war zones, and the British Royal Navy was receiving supply and repair assistance at American naval bases in the United States.

Thus by mid-1941 Roosevelt had committed the U.S. to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war." Roosevelt met with Churchill on August 14, 1941 to develop the Atlantic Charter in what was to be the first of several wartime conferences.

On December 19, 1941 Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8985, which established the Office of Censorship and conferred on its director the power to censor international communications in "his absolute discretion." Byron Price was selected as the Director of Censorship.

Pearl Harbor, Dec 7, 1941

Roosevelt tried to keep Japan out of the war. After Japan occupied northern French Indo-China in late 1940, he authorized increased aid to China. In July 1941, after Japan occupied the remainder of Indo-China, he cut off the sales of oil. Japan thus lost over 95% of its oil supply. Roosevelt continued negotiations with the Japanese government in the hope of averting war. Meanwhile he started shifting the long-range B-17 bomber force to the Philippines, where it could threaten the fire-bombing of Japanese cities.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, damaging most of it and killing 3,000 American personnel. The Japanese took advantage of their preemptive destruction of most of the Pacific Fleet to rapidly occupy the Philippines and the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia, taking Singapore in February 1942 and advancing through Burma to the borders of British India by May, cutting off the overland supply route to China. Antiwar sentiment in the United States evaporated overnight and the country united behind Roosevelt.

Despite the wave of anger that swept across the U.S. in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt decided from the start that the defeat of Nazi Germany had to take priority. Germany played directly into Roosevelt's hands when it declared war against the USA on December 11, 1941 which removed any meaningful opposition to "beating Hitler first." Roosevelt met with Churchill in late December and planned a broad alliance between the U.S., the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, with the objectives of, first, halting the German advances in the Soviet Union and in North Africa; second, launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts, and only third turning to the task of defeating Japan.

War strategy and planning for the post-war world

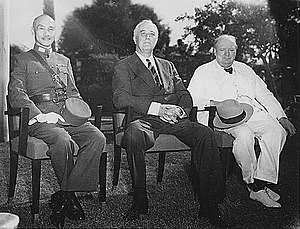

The "Big Three", (Roosevelt, Churchill, and Joseph Stalin, together with Chiang Kai-shek and Charles de Gaulle, oversaw an alliance in which British, American and French troops concentrated in the West while Russian troops fought on the Eastern front, and Chinese, British and American troops fought in the Pacific theatre. The Allies jointly formulated strategy in a series of high profile conferences as well as day to day contact through diplomatic and military channels.

The U.S. took the straightforward view that the quickest way to defeat Germany was to open a western front in France across the English Channel. Churchill, wary of the huge casualties he feared this would entail, favored a more indirect approach, advancing northwards from the Mediterranean, where the Allies were fully in control by early 1943, into either Italy or Greece, and then into central Europe. Churchill also saw this as a way of blocking the Soviet Union's advance into east and central Europe, a political issue which Roosevelt and his commanders refused to take into account. Stalin advocated the opening of a Western front at the earliest possible time, as the bulk of the battles in 1942 and 1943 were fought on Russian soil or in the Pacific theatre.

As long as the British were providing most of the troops, aircraft and ships against the Germans, Roosevelt felt he had to accept Churchill's idea that a launch across the Channel would have to wait. The Allies undertook the invasions of French Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) in November 1942, of Sicily (Operation Husky) in July 1943, and of Italy (Operation Avalanche) in September 1943. This entailed postponing the cross-Channel invasion from 1943 to 1944. The cross-Channel invasion (Operation Overlord) finally took place in June 1944. Although most of France was quickly liberated, the Allies were blocked on the German border in the "Battle of the Bulge" in December 1944, and final victory over Germany was not achieved until May 1945, by which time the Soviet Union had occupied eastern and central Europe as far west as the Elbe River in central Germany.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Japanese advance reached its maximum extent by June 1942, when Japan sustained a major naval defeat at the hands of the U.S. at the Battle of Midway. The Japanese advance to the south and south-east was halted at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 and the Battle of Guadalcanal between August 1942 and February 1943. The US then began a slow and costly progress through the Pacific islands, with the objective of gaining bases from which strategic air power could be brought to bear on Japan and from which Japan could ultimately be invaded. This did not prove necessary, because the almost simultaneous declaration of war on Japan by the Soviet Union and the use of the atomic bomb on Japanese cities brought about Japan's surrender in September 1945.

By late 1943 it was apparent that the Allies would ultimately defeat Nazi Germany, and it became increasingly important to make high-level political decisions about the course of the war and the postwar future of Europe. Roosevelt met with Churchill and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek at the Cairo Conference in November 1943, and then went to Tehran to confer with Churchill and Stalin. At the Tehran Conference Roosevelt and Churchill told Stalin about the plan to invade France in 1944, and Roosevelt also discussed his plans for a postwar international organization. Stalin was pleased that the western Allies had abandoned any idea of moving into the Balkans or central Europe via Italy, and he went along with Roosevelt's plan for the United Nations. Stalin also agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan when Germany was defeated. At this time Churchill and Roosevelt were acutely aware of the huge and disproportionate sacrifices the Soviets were making on the eastern front while their invasion of France was still six months away, so they did not raise awkward political issues which did not require immediate solutions, such as the future of Germany and Eastern Europe.

By the beginning of 1945, however, with the Allied armies advancing into Germany, consideration of these issues could not be put off. In February, Roosevelt, despite his steadily deteriorating health, traveled to Yalta, in the Soviet Crimea, to meet again with Stalin and Churchill. This meeting, the Yalta Conference, is often portrayed as a decisive turning point in modern history, though most of the decisions made there recognized realities which had already been established by force of arms. The decision of the western Allies to delay the invasion of France from 1943 to 1944 had allowed the Soviet Union to occupy all of eastern Europe, including Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, as well as eastern Germany. Since Stalin was in full control of these areas, there was little Roosevelt and Churchill could do to prevent him imposing his will on them, as he was rapidly doing by establishing Communist-controlled governments in all these countries.

Churchill, aware that the United Kingdom had gone to war in 1939 in defense of Polish independence, and also of his promises to the Polish government in exile in London, did his best to insist that Stalin agree to the establishment of a non-Communist government and the holding of free elections in liberated Poland, although he was unwilling to confront Stalin over the issue of Poland's postwar frontiers, on which he considered the Polish position to be indefensible. But Roosevelt was not interested in having a fight with Stalin over Poland, for two reasons. The first was that he believed that Soviet support was essential for the projected invasion of Japan, in which the Allies ran the risk of huge casualties. He feared that if Stalin was provoked over Poland he might renege on his Tehran commitment to enter the war against Japan. The second was that he saw the United Nations as the ultimate solution to all postwar problems, and he feared the United Nations project would fail without Soviet cooperation.

Fourth term and death, 1945

Although Roosevelt was only 62 in 1944, his health had been in decline since at least 1940. The strain of his paralysis and the physical exertion needed to compensate for it for over 20 years had taken their toll, as had many years of stress and a lifetime of chain-smoking. He had been diagnosed with high blood pressure and long-term heart disease, and was advised to modify his diet (although not to stop smoking). Aware of the risk that Roosevelt would die during his fourth term, the party regulars insisted that Henry A. Wallace, who was seen as too pro-Soviet, be dropped as Vice President. Roosevelt replaced Wallace with the little known Senator Harry S. Truman. In the 1944 elections, Roosevelt and Truman won 53% of the vote and carried 36 states, against New York Governor Thomas Dewey.

After the Yalta conference in February 1945, relations between the western Allies and Stalin deteriorated rapidly, and so did Roosevelt's health. When he addressed Congress on his return from Yalta, many were shocked to see how old, thin and sick he looked. He spoke from his wheelchair, an unprecedented concession to his physical incapacity. But he was still mentally fully in command. "The Crimean Conference," he said firmly, "ought to spell the end of a system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries — and have always failed. We propose to substitute for all these, a universal organization in which all peace-loving nations will finally have a chance to join." [16]

During March and early April 1945 he sent strongly worded messages to Stalin accusing him of breaking his Yalta commitments over Poland, Germany, prisoners of war and other issues. When Stalin accused the western Allies of plotting a separate peace with Hitler behind his back, Roosevelt replied: "I cannot avoid a feeling of bitter resentment towards your informers, whoever they are, for such vile misrepresentations of my actions or those of my trusted subordinates."[17]

On March 30, 1945 Roosevelt went to Warm Springs to rest before his anticipated appearance at the founding conference of the United Nations. On the morning of April 12, 1945 he complained of a sudden headache, then slumped forward in his chair and lost consciousness. The doctor saw he had suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage.

Roosevelt's death was greeted with shock and grief across the U.S. and around the world. At a time when the press did not pry into the health or private lives of presidents, his declining health had not been known to the general public. Roosevelt had been President for more than 12 years, longer than any other person, and had led the country through some of its greatest crises to the defeat of Nazi Germany, and to within sight of the defeat of Japan as well.

Less than a month later, on May 8, 1945 came the moment Roosevelt fought for: V-E Day. The new president, Harry Truman, dedicated V-E Day and its celebrations to Roosevelt's memory, paying tribute to his commitment towards ending the war in Europe.

Legacy

Roosevelt is considered by many to be a great president. A 1999 survey of academic historians by CSPAN found that historians consider Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Roosevelt the three greatest presidents by a wide margin, and other surveys are consistent.[18] Roosevelt is the sixth most admired person in the 20th century, according to Gallup.

Both during and after his terms, critics of Roosevelt questioned not only his policies and positions, but also the consolidation of power that occurred due to his lengthy tenure as president, his service during two major crises, and his enormous popularity. The rapid expansion of government programs that occurred during Roosevelt's term re-defined the role the government in the United States, and Roosevelt's advocacy of government social programs were instrumental in redefining liberalism for coming generations.[19]

Roosevelt firmly established the United States' leadership role on the world stage, with pronouncements such as his Four freedoms speech forming a basis for the active role of the United States in the Cold War and beyond. The decisions made at the Yalta conference established international alliances and boundries that continue to affect world diplomacy today.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's record on civil rights has also been the subject of much controversy. Roosevelt needed the support of Southern Democrats for his New Deal programs, and taking an aggressive position on civil rights could have threatened his ability to pass his highest priority programs. In addition, Roosevelt participated in the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and has been charged with not acting quickly or decisively enough to prevent or stop the Holocaust.

Roosevelt's home in Hyde Park is now a National historic site and Presidential library. The Roosevelt memorial has been established in Washington, D.C. next to the Jefferson Memorial on the Tidal Basin.

Administration, Cabinet, and Supreme Court appointments 1933-1945

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 1933–1945 |

| Vice President | John Nance Garner | 1933–1941 |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1941–1945 | |

| Harry S. Truman | 1945 | |

| State | Cordell Hull | 1933–1944 |

| Edward R. Stettinius, Jr. | 1944–1945 | |

| War | George H. Dern | 1933–1936 |

| Harry H. Woodring | 1936–1940 | |

| Henry L. Stimson | 1940–1945 | |

| Treasury | William H. Woodin | 1933–1934 |

| Henry Morgenthau, Jr. | 1934–1945 | |

| Justice | Homer S. Cummings | 1933–1939 |

| William F. Murphy | 1939–1940 | |

| Robert H. Jackson | 1940–1941 | |

| Francis B. Biddle | 1941–1945 | |

| Post | James A. Farley | 1933–1940 |

| Frank C. Walker | 1940–1945 | |

| Navy | Claude A. Swanson | 1933–1939 |

| Charles Edison | 1940 | |

| Frank Knox | 1940–1944 | |

| James V. Forrestal | 1944–1945 | |

| Interior | Harold L. Ickes | 1933–1945 |

| Agriculture | Henry A. Wallace | 1933–1940 |

| Claude R. Wickard | 1940–1945 | |

| Commerce | Daniel C. Roper | 1933–1938 |

| Harry L. Hopkins | 1939–1940 | |

| Jesse H. Jones | 1940–1945 | |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1945 | |

| Labor | Frances C. Perkins | 1933–1945 |

President Roosevelt appointed nine Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. John Tyler also appointed nine, and George Washington appointed eleven (all others appointed fewer). By 1941, eight of the nine Justices were Roosevelt appointees.

- Hugo Black (AL) August 19, 1937 – September 17, 1971

- Stanley Forman Reed (KY) January 31, 1938 – February 25, 1957

- Felix Frankfurter (MA) January 30, 1939 – August 28, 1962

- William O. Douglas (CT) April 17, 1939 – November 12, 1975

- Frank Murphy (MI) February 5, 1940 – July 19, 1949

- Harlan Fiske Stone (Chief Justice, NY) July 3, 1941 – April 22, 1946

- James Francis Byrnes (SC) July 8, 1941 – October 3, 1942

- Robert H. Jackson (NY) July 11, 1941 – October 9, 1954

- Wiley Blount Rutledge (IA) February 15, 1943 – September 10, 1949

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

References

- ^ Eleanor and Franklin, Lash (1971), 111 et seq.

- ^ Garret, Garet. Saturday Evening Post, 1938

- ^ Flynn, John T. The Roosevelt Myth

- ^ The Exemplary Presidency: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the American Political Tradition, Philip Abbott (1990) at 20

- ^ Gordon, John Steele. The Federal Debt, American Heritage Magazine, November 1995, Volume 46, Issue 7

- ^ Great Speeches, Franklin D Roosevelt (1999).

- ^ More: The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America, Collins (2002) at 5.

- ^ Great Speeches, Franklin D Roosevelt (1999) at 17.

- ^ "The United States: 1900-1945" in The Oxford History of the Twentieth Century, W Roger Louis (2006).

- ^ Cole, Harold L and Ohanian, Lee E. New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great <3 Depression: A General Equilibrium Analysis, 2004.

- ^ Historical Stats. U.S. (1976) series F31

- ^ Historical Statistics US (1976) series D-86; Smiley 1983

- ^ Smiley, Gene, "Recent Unemployment Rate Estimates for the 1920s and 1930s," Journal of Economic History, June 1983, 43, 487-93.

- ^ "Presidents and job growth". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Pusey, Merlo J. F.D.R. vs. the Supreme Court, American Heritage Magazine, April 1958,Volume 9, Issue 3

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945, Robert Dallek (1995) at 520.

- ^ War in Italy 1943-1945, Richard Lamb (1996) at 287.

- ^ American PresidentsSee, also, for example:

- Opinion Journal

- Gvsu.edu, website of Grand Valley State University

- The The Washington Post found Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt to be the only "great" Presidents.

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Jr, Liberalism in America: A Note for Europeans from The Politics of Hope, Riverside Press, Boston, 1962.

- Primary sources

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds.; Public Opinion, 1935-1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls from USA

- Gallup, George Horace, ed. The Gallup Poll; Public Opinion, 1935-1971 3 vol (1972) summarizes results of each poll as reported to newspapers.

- Loewenheim, Francis L. et al, eds; Roosevelt and Churchill: Their Secret Wartime Correspondence (1975)

- Moley, Raymond. After Seven Years (1939), memoir by key Brain Truster

- Nixon, Edgar B. ed. Franklin D. Roosevelt and Foreign Affairs (3 vol 1969), covers 1933-37. 2nd series 1937-39 available on microfiche and in a 14 vol print edition at some academic libraries.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D.; Rosenman, Samuel Irving, ed. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (13 vol, 1938, 1945); public material only (no letters); covers 1928-1945.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976)

- Zevin, B. D. ed.; Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945 (1946) selected speeches

- Documentary History of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration 20 vol. available in some large academic libraries.

- Scholarly secondary sources

- Beasley, Maurine, et al eds. The Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia (2001)

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt (1956, 1970), 2 vol; interpretive biography, emphasis on politics; vol 2 is on war years

- Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny (1990), One-volume scholarly biography; covers entire life

- Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt (4 vol 1952-73), scholarly biography; ends in 1934.

- Graham, Otis L. and Meghan Robinson Wander, eds. Franklin D. Roosevelt: His Life and Times. (1985). encyclopedia

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. (1999), general survey

- Leuchtenberg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. (1963). A standard interpretive history of era.

- Herbert S. Parmet and Marie B. Hecht; Never Again: A President Runs for a Third Term (1968)

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr., The Age of Roosevelt, 3 vols, (1957-1960), the classic narrative history. Strongly supports FDR. Online at vol 2 vol 3

- Popular Biographies

- Black, Conrad. Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom, Public Affairs, 2003. Popular biography

- Davis, Kenneth S. FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny, 1982-1928 (1972)

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II (1995)

- Lash, Joseph P. Eleanor and Franklin: The Story of Their Relationship Based on Eleanor Roosevelt's Private Papers (1971), history of a marriage.

- Morgan, Ted, FDR: A biography, Simon & Schuster, New York (1985), a popular biography

- Ward, Geoffrey C. Before The Trumpet: Young Franklin Roosevelt, 1882-1905 HarperCollins, 1985.

- Geoffrey C. Ward, A First Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt, HarperCollins, 1992, covers 1905-1932.

- Foreign Policy and World War II

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002).

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt: Soldier of Freedom (1970), vol 2 covers the war years.

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945 (2nd ed. 1995).

- Heinrichs, Waldo. Threshold of War. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and American Entry into World War II (1988).

- Herring Jr. George C. Aid to Russia, 1941-1946: Strategy, Diplomacy, the Origins of the Cold War (1973)

- Kimball, Warren. The Juggler: Franklin Roosevelt as World Statesman (1991)

- Langer, William and S. Everett Gleason. The Challenge to Isolation, 1937-1940 (1952). Vol 1 of highly influential semi-official history

- Langer, William L. and S. Everett Gleason. The Undeclared War, 1940-1941 (1953). Vol 2 of highly influential semi-official history

- Larrabee, Eric. Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War. History of how FDR handled the war

- Offner, Arnold A. America and the Origins of World War II, 1933-1941: New Perspectives in History (1971)

- Rauch, Basil. Roosevelt, from Munich to Pearl Harbor: A Study in the Creation of a Foreign Policy (1950)

- Schmitz, David F. and Richard D. Challener. Appeasement in Europe: A Reassessment of U.S. Policies (1990)

- Traina, Richard P. American Diplomacy and the Spanish Civil War (1968).

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994). Overall history of the war; strong on diplomacy of FDR and other main leaders

- Wood, Bryce. The Making of the Good Neighbor Policy (1961).

- Woods, Randall Bennett. A Changing of the Guard: Anglo-American Relations, 1941-1946 (1990)

- Criticisms

- Barnes, Harry Elmer. Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: A Critical Examination of the Foreign Policy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Its Aftermath (1953). from a leading "revisionist" who blames FDR for inciting Japan to attack.

- Conkin, Paul K. New Deal (1975), critique from the left

- Gary Dean Best. The Retreat from Liberalism: Collectivists versus Progressives in the New Deal Years (2002) Best (a conservative) criticizes intellectuals who supported FDR

- Gary Dean Best. Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933-1938 Praeger Publishers. 1991; summarizes conservative newspaper editorials

- Kennedy, Thomas C. Charles A. Beard and American Foreign Policy (1975) scholarly analysis of leading revisionist

- Moley, Raymond. After Seven Years (1939) insider memoir by Brain Truster who became conservative

- Russett, Bruce M. No Clear and Present Danger: A Skeptical View of the United States Entry into World War II 2nd ed. (1997) says US should have let USSR and Germany destroy each other

- Powell, Jim. FDR's Folly: How Roosevelt and His New Deal Prolonged the Great Depression. (Crown Forum, 2003), a stinging attack on all FDR's policies from the right

- Greg Robinson. By Order of the President : FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (2001) says FDR's racism was primarily to blame.

- Gene Smiley. Rethinking the Great Depression (1993) short essay by economist who blames both Hoover and FDR

- David S. Wyman. The Abandonment Of The Jews: America and the Holocaust Pantheon Books, 1984. Attacks Roosevelt for passive complicity in allowing Holocaust to happen

External links

Speeches: audio and transcripts

- The American Presidency Project at University of California at Santa Barbara

- Roosevelt's Secret White House Recordings via University of Virginia

- FDR - Day of Infamy video clip (2 min.)

- Audio clips of speeches

- First Inaugural Address, via Yale University

- Second Inaugural Address, via Yale University

- Third Inaugural Address, via Yale University

- Fourth Inaugural Address, via Yale University

- Court "Packing" Speech March 9, 1937

- University of Virginia graduating class speech ("Stab in the Back" speech) June 10, 1940

Other

- IPL POTUS — Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Encyclopedia Americana: Franklin D. Roosevelt

- An archive of political cartoons from the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Warm Springs and FDR's Polio Treatment

- Dutch Martin's review of FDR's folly

- FDR at the Atlantic Conference

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Links

- On Franklin Roosevelt's progressive vision from the Roosevelt Institution, a student think tank inspired in part by Franklin Roosevelt.

- Works by Franklin D. Roosevelt at Project Gutenberg

- 1882 births

- 1945 deaths

- Alpha Delta Phi brothers

- American lawyers

- Columbia University alumni

- Delano family

- Delta Kappa Epsilon brothers

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- Dutch Americans

- Elks

- Episcopalians

- Freemasons

- Governors of New York

- Harvard University alumni

- Knights of Pythias

- Loyal Order of Moose members

- New Deal

- New York State Senators

- Phi Beta Kappa members

- Philatelists

- Politicians with physical disabilities

- Presidents of the United States

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Roosevelt family

- Rotary Club members

- Scottish-Americans

- Shriners

- Silver Buffalo awardees

- U.S. Democratic Party vice presidential nominees

- World War II political leaders