Sikh Confederacy

Sikh Confederacy | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1748–1799 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: ਦੇਗ ਤੇਗ ਫ਼ਤਿਹ Dēġ Tēġ Fatih "Victory to Charity and Arms" | |||||||||||||||

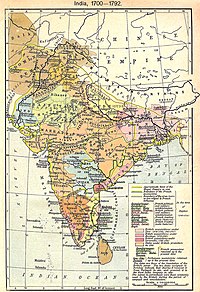

Map of the Punjab or "Country of the Sikhs" in 1782 by James Rennell | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Amritsar | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Punjabi | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sikhism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederation | ||||||||||||||

| Jathedar | |||||||||||||||

• 1737–1753 | Nawab Kapur Singh | ||||||||||||||

• 1753–1783 | Jassa Singh Ahluwalia | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Sarbat Khalsa | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Passing of a Gurmata to form the Misls | 1748 | ||||||||||||||

• Maharaja Ranjit Singh unites the misls into the Sikh Empire | 1799 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Nanakshahi | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Pakistan | ||||||||||||||

The Misls (derived from the Arabic word مِثْل meaning 'equal'; sometimes spelt as Misal)[1] were the twelve sovereign states of the Sikh Confederacy,[2][3][4] which rose during the 18th century in the Punjab region in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent and is cited as one of the causes of the weakening of the Mughal Empire prior to Nader Shah's invasion of India in 1738–1740.[5]

History

In order to withstand the persecution of Shah Jahan and other Mughal rulers, several of the later Sikh Gurus established military forces and fought the Mughal Empire and Hindu hill chiefs[6] in the early and middle Mughal-Sikh Wars. Banda Singh Bahadur continued Sikh resistance to the Mughal Empire until his defeat at the Battle of Gurdas Nangal.

For several years Sikhs found refuge in the jungles and the Himalayan foothills until they organized themselves into military bands known as jathas.

The basis of the Dal Khalsa army was established in 1733–35 based upon the numerous pre-existing Jatha militia groups and had two main formations: the Taruna Dal (army of the young) and the Budha Dal (army of the old).[7]

On the annual Diwali meeting of the Sarbat Khalsa in Amritsar in 1748, a Gurmata was passed where the Jathas were reorganized into a new grouping called misls, with 11 Misls forming out of the various pre-existing Jathas and a unified army known as the Dal Khalsa Ji.[7] Ultimate command over the Misls was bestowed to Jassa Singh Ahluwalia.[7]

The misls formed a commonwealth that was described by Swiss adventurer Antoine Polier as a natural "aristocratic republic".[8] Although the misls were unequal in strength, and each misl attempted to expand its territory and access to resources at the expense of others, they acted in unison in relation to other states.[5] The misls held biannual meetings of their legislature, the Sarbat Khalsa in Amritsar.[5]

List of misls

Military

| Sikh Confederacy (1707–1799) |

Each Misl was made up of members of soldiers, whose loyalty was given to the Misl's leader. A Misl could be composed of a few hundred to tens of thousands of soldiers. Any soldier was free to join whichever Misl he wished, and was free to cancel his membership of the Misl to whom he belonged. He could, if he wanted, cancel his membership of his old Misl and join another. The Barons would allow their armies to combine or coordinate their defences together against a hostile force if ordered by the Misldar Supreme Commander. These orders were only issued in military matters affecting the whole Sikh community. These orders would normally be related to defense against external threats, such as Afghan military attacks. The profits of a fighting action were divided by the misls to individuals based on the service rendered after the conflict using the sardari system.

The Sikh Confederacy is a description of the political structure, of how all the barons' chiefdoms interacted with each other politically together in Punjab. Although misls varied in strength, the use of primarily light cavalry with a smaller amount heavy cavalry was uniform throughout all of the Sikh misls. Cavalrymen in a misl were required to supply their own horses and equipment.[32] A standard cavalryman was armed with a spear, matchlock, and scimitar.[33] How the armies of the Sikh misls received payment varied with the leadership of each misl. The most prevalent system of payment was the 'Fasalandari' system; soldiers would receive payment every six months at the end of a harvest.[34]

Cavalry tactics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2015) |

Fauja Singh considers the Sikh misls to be guerrilla armies, although he notes that the Sikh misls generally had greater numbers and a larger number of artillery pieces than a guerrilla army would.[32] The misls were primarily cavalry based armies and employed less artillery than Mughal or Maratha armies. The misls adapted their tactics to their strength in cavalry and weakness in artillery and avoided pitched battles. Misls organized their armies around bodies of horsemen and their units fought battles in a series of skirmishes, a tactic which gave them an advantage over fighting pitched battles. Bodies of cavalry would attack a position, retreat, reload their muskets, and return to attack it again. The tactics used by misl field armies include flanking an enemy, obstructing river passages, cutting off a unit from its supplies, intercepting messengers, attacking isolated units like foraging parties, employing hit-and-run tactics, overrunning camps, and attacking baggage trains. To fight large armies the misl would completely evacuate the areas in front of the enemy's marching route but follow in the rear of the opposition and reconquer areas the enemy had just captured, threaten agents of the enemy with retribution, and sweep over the countryside in the wake of the enemy's withdrawal.

The Running Skirmish was a tactic unique to the Sikh cavalrymen which was notable for its effectiveness and the high degree of skill required to execute it. George Thomas and George Forster, contemporary writers who witnessed it described its use separately in their accounts of the military of the Sikhs. George Forster noted:

"A party from forty to fifty, advance in a quick pace to a distance of carbine shot from the enemy and then, that the fire may be given with the greatest certainty, the horses are drawn up and their pieces discharged, when speedily, retiring about a 100 paces, they load and repeat the same mode of annoying the enemy. Their horses have been so expertly trained to a performance of this operation that on receiving a stroke of hand, they stop from a full canter."

Administration

The remainder was separated into Puttees or parcels for each Surkunda, and these were again subdivided and parcelled out to inferior leaders, according to the number of horse they brought into the field. Each took his portion as a co-sharer, and held it in absolute independence.

— Origin of the Sikh power in the Punjab (1834) p. 33 – Henry Thoby Prinsep

The Sikh Misls had four different classes of administrative divisions. The patadari, misaldari, tabadari, and jagirdari were the different systems of land tenure used by the misls, and land granted by the misl left the responsibility of establishing law and order to the owner of the land. The land under the direct administration of the chief of the misl was known as the sardari and the tabadari and jagirdari systems used land directly given by the chief from the sardari. The patadari and misaldari systems formed the basis of a misl, while tabadari and jagirdari lands would only be created after large acquisitions of land. The type of system that was used in an area depended on the importance of the chief sardar of the area to the rest of the misl.

Patadari system

The Patadari system affected newly annexed territories and was the original method used by the misls in administering land.[35] The patadari system relied on the cooperation of surkundas, the rank of a leader of a small party of cavalrymen. The chief of the misl would take his/her portion and divide the other parcels among his Sardars proportional to the number of cavalrymen they had contributed to the misl.[36] The Sardars would then divide their parcels among their Surkundas, and then the Surkundas subdivided the land they received among their individual cavalrymen. The Surkundas receiving parcels of land with settlements were required to fortify them[note 2] and establish fines and laws for their zamindars and ryots.[37] Parcels of land in the patadari system could not be sold, but could be given to relatives in an inheritance.[38] The soldiers who received parcels from the Patadari system held their land in complete freedom.[5]

Misaldari system

The Misaldari system applied to sardars with a small number of cavalrymen as well as independent bodies of cavalrymen who voluntarily attached themselves to a misl.[38] They kept the lands they held before joining the misl as an allotment for their cooperation with the misl. The leaders of these groups, called misaldars, could transfer their allegiance and land to another misl without punishment.[38]

Tabadari system

The Tabadari system referred to land under the control of a misl's tabadars. Tabadars served a similar function to retainers in Europe. They were required to serve as cavalrymen to the misl and were subservient to the misl's leader. Although tabadars received their land as a reward, their ownership was subject entirely on the misl's leader.[39] The tabadari grants were only hereditary on the choice of the chief of the misl.

Jagirdari system

The Jagirdari system used the grant of jagirs by the chief of the misl. Jagirs were given by the chief of the misl to relations, dependents, and people who "deserved well".[39] The owners of jagirs were subservient to the chief of the misl as their ownership was subject to his/her needs. Like the Tabadars, jagirdars were subject to personal service when the chief of the misl requested.[39] However, because jagirs entailed more land and profit, they were required to use the money generated by their jagirs to equip and mount a quota of cavalrymen depending on the size of their jagir.[39] Jagirdari grants were hereditary in practice but a misl's chief could revoke the rights of the heir. Upon the death of the owner of a tabadari or jagadari grant, the land would revert to direct control of the chief (sardari).

Rakhi system

The Rakhi system was the payment-for-protection tributary protectorate scheme practiced by the Dal Khalsa of the Sikh Confederacy in the 18th century.[40][41] It was a large source of income to the Sikh Misls.[42][43]

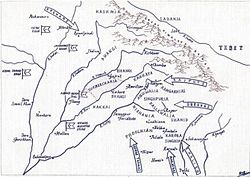

Territory

The two main divisions in territory between the misls were between those who were in the Malwa region and those who were in the Majha region. While eleven of the misls were north of the Sutlej river, one, the Phulkian Misl was south of the Sutlej.[44] The Sikhs north of the Sutlej river were known as the Majha Sikhs while the Sikhs that lived south of the Sutlej river were known as the Malwa Sikhs.[22] In the smaller territories were the Dhanigeb Singhs in the Sind Sagar Doab, the Gujrat Singhs in the Jech Doab, the Dharpi Singhs in the Rechna Doab, and the Doaba Singhs in the Jalandhar Doab.[22]

Sikh women in state affairs

- Mai Fateh Kaur (d.1773) of Patiala Sikh dynasty

- Mai Desan Kaur (d.1778) of Sukerchakia Sikh Misl

- Bibi Rajinder Kaur (1739–1791) of Patiala Sikh dynasty

- Mai Sukkhan Kaur (r.1802) of Bhangi Sikh Misl

- Mai Lachhmi Kaur of Bhangi Sikh Misl

- Rani Sada Kaur (1762–1832) of Kanhaiya Sikh Misl

- Bibi Rattan Kaur of Dallewalia Sikh Misl

- Mai Karmo Kaur of Nakai Sikh Misl

- Bibi Sahib Kaur (1771–1801) of Patiala Sikh dynasty

- Maharani Datar Kaur of Sikh Empire (maiden name Raj Kaur of Nakai Misl) (1784–1838)

- Rani Aus Kaur (1772–1821) of Patiala Sikh dynasty

- Maharani Jind Kaur (1817–1863) of Sikh Empire

- Bibi Daya Kaur (d.1823) of Nishanwalia Sikh Misl

- Rani Desa Kaur Nabha of Nabha Sikh dynasty

- Bibi Khem Kaur Dhillon Of Sikh Empire

- Maharani Chand Kaur (1802–1842) of Sikh Empire

Battles fought by Sikhs

- Battle of Rohilla

- Battle of Kartarpur

- Battle of Amritsar (1634)

- Battle of Lahira

- Battle of Bhangani

- Battle of Nadaun

- Battle of Guler (1696)

- Battle of Basoli

- First Battle of Anandpur

- Battle of Nirmohgarh (1702)

- Second Battle of Anandpur

- Second Battle of Chamkaur (1704)

- Battle of Muktsar

- Battle of Sonepat

- Battle of Ambala

- Battle of Samana

- Battle of Chappar Chiri

- Battle of Sadhaura

- Battle of Rahon (1710)

- Battle of Lohgarh

- Battle of Jammu

- Battle of Jalalabad (1710)

- Siege of Gurdaspur or Battle of Gurdas Nangal

- Battle of Manupur (1748)

- Battle of Amritsar (1757)

- Battle of Lahore (1759)

- Battle of Sialkot (1761)

- Battle of Gujranwala (1761)

- Sikh Occupation of Lahore[45]

- Sikh holocaust of 1762 or Battle of Kup

- Battle of Harnaulgarh

- Battle of Amritsar (1767)

- Battle of Sialkot (1763)

- Battle of Sirhind (1764)

- Battle of Delhi (1783)

- Battle of Amritsar(1797)

- Gurkha-Sikh War

- Battles of Sialkot

- Battle of Jammu (1808)

- Battle of Attock

- Battle of Multan

- Battle of Shopian

- Battle of Balakot

- Battle of Peshawar (1834)

- Battle of Jamrud

- Sino-Sikh War

- Battle of Mudki

- Battle of Ferozeshah

- Battle of Baddowal

- Battle of Aliwal

- Battle of Sobraon

- Battle of Chillianwala

- Battle of Ramnagar

- Siege of Multan (1772)

- Battle of Gujrat

See also

- Dal Khalsa, the military forces of the Sikh Confederacy

- History of Punjab

- Jat Mahasabha

- Khap

Bibliography

- Nalwa, Vanit (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa – Champion of the Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, ISBN 978-81-7304-785-5

- Narang, K. S.; Gupta, H. R. (1969). History of Punjab: 1500–1558. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- M'Gregor, William Lewis (1846). The history of the Sikhs: containing the lives of the Gooroos; the history of the independent Sirdars, or Missuls, and the life of the great founder of the Sikh monarchy, Maharajah Runjeet Singh. J. Madden. p. 216. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Singh, Fauja (1964). Military system of the Sikhs: during the period 1799–1849. Motilal Banarsidass. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Prinsep, Henry Thoby (1834). Origin of the Sikh power in the Punjab, and political life of Muha-Raja Runjeet Singh: with an account of the present condition, religion, laws and customs of the Sikhs. G.H. Huttmann. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- Cave-Browne, John (1861). The Punjab and Delhi in 1857: being a narrative of the measures by which the Punjab was saved and Delhi recovered during the Indian Mutiny. William Blackwood and Sons. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- Brief History of the Sikh Misls. Jalandhar: Sikh Missionary College.

- Suri, Sohan Lal (1961). Umdat-ut-Tawarikh, DAFTAR III, PARTS (I—V) 1831–1839 A.D. Delhi: S. Chand & Co.

- Kakshi, S.R.; Pathak, Rashmi; Bakshi, S.R.; Pathak, R. (2007). Punjab Through the Ages. Sarup and Son. ISBN 978-81-7625-738-1.

- Oberoi, Harjot (1994). The Construction of religious boundaries: culture, identity, and diversity in the Sikh tradition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Ahmad Shah Batalia, Appendix to Sohan Lal Suri's Umdat-ut-Tawarikh. Daftar I, Lahore, 1X85, p. 15; Bute Shahs Tawarikh-i-Punjab, Daftar IV, (1848), (MS., Ganda Singh's personal collection. Patiala), p. 6; Kanaihya Lal, Tarikh-i-Punjab, Lahore, 1877, p. 88; Ali-ud-Din Mufti, Ibratnama, Vol. I, (1854), Lahore, 1961, p. 244. Muhammad Latif, History of the Punjab (1891), Delhi, 1964, p. 296.

- Ian Heath, The Sikh Army, 1799–1849 (Men-at-arms), Osprey (2005) ISBN 1-84176-777-8

- Harbans Singh, The Heritage of the Sikhs, second rev. ed., Manohar (1994) ISBN 81-7304-064-8

- Hari Ram Gupta, History of the Sikhs: Sikh Domination of the Mughal Empire, 1764–1803, second ed., Munshiram Manoharlal (2000) ISBN 81-215-0213-6

- Hari Ram Gupta, History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Commonwealth or Rise and Fall of the Misls, rev. ed., Munshiram Manoharlal (2001) ISBN 81-215-0165-2

- Gian Singh, Tawarikh Guru Khalsa, (ed. 1970), p. 261.

Notes

References

- ^ Herrli, Hans (1993). The Coins of the Sikhs. p. 11.

The word misl seems to have been derived from an Arabic word meaning: equal.

- ^ Heath, Ian (1 January 2005). "The Sikh Army". Osprey. ISBN 9781841767772. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "The Khalsa Era". Nishan Sahib. 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Kaur, Prabhjot; Sharma, Rohita (3 June 2021). "CONTRIBUTION OF SIKH MISLS IN GREAT SIKH HISTORY" (PDF). Impact Journals. 9 (6): 20.

- ^ a b c d Kakshi et al. 2007, p. 73

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1 February 2008). "13 Khalsa Battles Against Islamic Imperialism and Hindu Conservatism". History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1606–1708 C.E. Atlantic Publishing. p. 814. ISBN 978-81-269-0858-5.

- ^ a b c Singh, Harbans. The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Vol. 2: E-L. Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 362–3.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (11 October 2004). A History of the Sikhs: 1469–1838 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Herrli, Hans (1993). Coins of the Sikhs. p. 11.

The list is based on data given by H.T. PRINSEP.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel Henry (1893). Ranjít Singh. Clarendon Press. p. 78.

- ^ Bajwa, Sandeep Singh. "Sikh Misals (equal bands)". Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ GUPTA, HARI RAM (1944). TRANS-SATLUJ SIKH. LAHORE: THE MINEVERA BOOK SHOP. p. 3.

- ^ Kakshi et al. 2007, p. 163–164

- ^ Griffin, sir Lepel Henry (1870). The rajas of the Punjab, the history of the principal states in the Punjab and their political relations with the British government.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (2 November 2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-987717-1.

- ^ Bajwa, Sandeep Singh. "Bhangi Misl". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Bajwa, Sandeep Singh. "Misal Kanhaiya". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Gupta, HARI RAM (1944). TRANS SATLUJ SIKHS. Lahore: THE MINEVERA BOOK SHOP. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dhir, Krishna S. (2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 536–537. ISBN 9788120843011.

- ^ GUPTA, HARI RAM (1944). TRANS SATLUJ SIKHS. LAHORE: THE MINEVERA BOOK SHOP. p. 3.

- ^ "The Sodhis of Anandpur Sahib". Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Kakshi et al. 2007, p. 164

- ^ Bajwa, Sandeep Singh. "Misal Karorasinghia". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 14, p. 320.

- ^ Roopinder Singh (1 March 2015). "Kalsia's royal past recreated". The Tribune.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel H. History of the Panjab Chiefs. p. 352.

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Braving the ravages of time". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Singh, Khazan (1970). History of the Sikh Religion. Department of Languages, Punjab.

- ^ Journal of Regional History. Department of History, Guru Nanak Dev University. 1981.

- ^ Bajwa, Sandeep Singh. "Misal Nakai". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Bhagata, Siṅgha (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Punjabi University. p. 241.

Deep Singh Shahid, a mazhabi sikh and resident of the village of Pohuwind of the pargana of Amritsar...

- ^ a b Singh 1963, p. 23

- ^ Francklin, William (1805). Military memoirs of Mr. George Thomas; who, by extraordinary talents and enterprise, rose from an obscure situation to the rank of a general, in the service of the native powers in the North-West of India. Reprinted for John Stockdale. p. 107. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ Singh, Fauja (1964). Military system of the Sikhs: during the period 1799–1849. Motilal Banarsidass. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ Prinsep 1834, p. 33

- ^ a b Prinsep 1834, p. 34

- ^ Prinsep 1834, p. 34–35

- ^ a b c Prinsep 1834, p. 35

- ^ a b c d Prinsep 1834, p. 36

- ^ Bhagata, Siṅgha (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Patiala Punjabi University. pp. 44–50.

- ^ Gopal Singh (1994). Politics of Sikh homeland, 1940-1990. Delhi: Ajanta Publications. pp. 39–42. ISBN 81-202-0419-0. OCLC 32242388.

- ^ Bhagata, Siṅgha (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Patiala Punjabi University. pp. 44–50.

- ^ Gopal Singh (1994). Politics of Sikh homeland, 1940-1990. Delhi: Ajanta Publications. pp. 39–42. ISBN 81-202-0419-0. OCLC 32242388.

- ^ Oberoi 1994, p. 73

- ^ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 23 September 2010.