Adinazolam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | < 3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

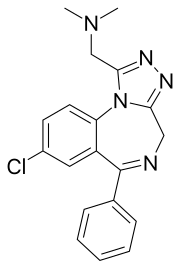

| Formula | C19H18ClN5 |

| Molar mass | 351.8 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Adinazolam[1] (marketed under the brand name Deracyn) is a benzodiazepine derivative, and more specifically, a triazolobenzodiazepine (TBZD). It possesses anxiolytic,[2] anticonvulsant, sedative, and antidepressant[3][4] properties. Adinazolam was developed by Dr. Jackson B. Hester, who was seeking to enhance the antidepressant properties of alprazolam, which he also developed.[5] Adinazolam was never FDA approved and never made available to the public market, however it has been sold as a designer drug.[6]

Side effects

Overdose may include muscle weakness, ataxia, dysarthria and particularly in children paradoxical excitement, as well as diminished reflexes, confusion and coma may ensue in more severe cases.[7]

A human study comparing the subjective effects and abuse potential of adinazolam (30 mg and 50 mg) with diazepam, lorazepam and a placebo showed that adinazolam causes the most "mental and physical sedation" and the greatest "mental unpleasantness".[8]

Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

Adinazolam binds to peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors that interact allosterically with GABA receptors as an agonist to produce inhibitory effects.

Metabolism

Adinazolam was reported to have active metabolites in the August 1984 issue of The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology.[9] The main metabolite is N-desmethyladinazolam.[10] NDMAD has an approximately 25-fold high affinity for benzodiazepine receptors as compared to its precursor, accounting for the benzodiazepine-like effects after oral administration.[1] Multiple N-dealkylations lead to the removal dimethyl-aminoethyl side chain, leading to the difference in its potency.[10] The other two metabolites are alpha-hydroxyalprazolam and estazolam.[11] In the August 1986 issue of that same journal, Sethy, Francis and Day reported that proadifen inhibited the formation of N-desmethyladinazolam.[12]

See also

References

- ^ a b FR Patent 2248050

- ^ Karthik Venkatakrishnan; Lisa L. Von Moltke; Su Xiang Duan; Joseph C. Fleishaker; Richard I. Shader; David J. Greenblat (March 1998). "Kinetic Characterization and Identification of the Enzymes Responsible for the Hepatic Biotransformation of Adinazolam and N-Desmethyladinazolam in Man". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 50 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb06859.x. PMID 9600717.

- ^ Dunner D, Myers J, Khan A, Avery D, Ishiki D, Pyke R (June 1998). "Adinazolam-A New Antidepressant: Findings of a Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study in Outpatients with Major Depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 7 (3): 170–172. PMID 3298327.

- ^ Lahti, Robert A.; Vimala H. Sethy; Craig Barsuhn; Jackson B. Hester (November 1983). "Pharmacological profile of the antidepressant adinazolam, a triazolobenzodiazepine". Neuropharmacology. 22 (11): 1277–82. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(83)90200-9. PMID 6320036.

- ^ "Discovers Award 2004" (PDF). Special Publications. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. April 2004. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Moosmann, Bjoern; Bisel, Philippe; Franz, Florian; Huppertz, Laura M.; Auwärter, Volker (2016). "Characterization and in vitro phase I microsomal metabolism of designer benzodiazepines – an update comprising adinazolam, cloniprazepam, fonazepam, 3-hydroxyphenazepam, metizolam, and nitrazolam". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. doi:10.1002/jms.3840. ISSN 1096-9888. PMID 27535017 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ "Adinazolam". DrugBank.

- ^ M. Bird; D. Katz; M. Orzack; L. Friedman; E. Dessain; B. Beake; J. McEachern; J. Cole (1987). "The Abuse Potential of Adinazolam: A Comparison with Diazepam, Lorazepam and Placebo" (PDF). NIDA Research Monograph No. 81.

- ^ Sethy, Vimala H.; R. J. Collins; E. G. Daniels (August 1984). "Determination of biological activity of adinazolam and its metabolites". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 36 (8): 546–8. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1984.tb04449.x. PMID 6148400.

- ^ a b Peng, G. W. (August 1984). "Assay of adinazolam in plasma by liquid chromatography". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 73 (8): 1173–5. doi:10.1002/jps.2600730840. PMID 6491930.

- ^ Fraser, A. D.; A. F. Isner; W. Bryan (November–December 1993). "Urinary screening for adinazolam and its major metabolites by the Emit d.a.u. and FPIA benzodiazepine assays with confirmation by HPLC". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 17 (7): 427–31. doi:10.1093/jat/17.7.427. PMID 8309217.

- ^ Sethy, Vimala H.; Jonathan W. Francis; J. S. Day (August 1986). "The effect of proadifen on the metabolism of adinazolam". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 38 (8): 631–2. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1986.tb03099.x. PMID 2876087.