Uruguay

Oriental Republic of Uruguay | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Libertad o Muerte "Freedom or Death" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Uruguay "National Anthem of Uruguay" | |

| Sol de Mayo[1][2] (Sun of May)  | |

Location of Uruguay (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Montevideo 34°53′S 56°10′W / 34.883°S 56.167°W |

| Official language | |

| Ethnic groups (2011)[5] |

|

| Religion (2021)[6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Uruguayan |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Luis Lacalle Pou | |

| Beatriz Argimón | |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Representatives | |

| Independence from Brazil | |

• Declared | 25 August 1825 |

| 27 August 1828 | |

| 15 February 1967 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 176,215 km2 (68,037 sq mi)[7] (89th) |

• Water (%) | 1.5 |

| Population | |

• 2023 census | 3,499,451[8] (132nd) |

• Density | 19.5/km2 (50.5/sq mi) (206th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (52nd) |

| Currency | Uruguayan peso (UYU) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (UYT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +598 |

| ISO 3166 code | UY |

| Internet TLD | .uy |

Uruguay (/ˈjʊərəɡwaɪ/ [12] YOOR-ə-gwy, Spanish: [uɾuˈɣwaj] ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay (Spanish: República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast. It is part of the Southern Cone region of South America. Uruguay covers an area of approximately 176,215 square kilometres (68,037 sq mi).[8] It has a population of around 3.4 million, of whom nearly 2 million live in the metropolitan area of its capital and largest city, Montevideo.

The area that became Uruguay was first inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers 13,000 years ago.[13] The predominant tribe at the moment of the arrival of Europeans was the Charrúa people. At the same time, there were also other tribes, such as the Guaraní and the Chaná, when the Portuguese first established Colonia do Sacramento in 1680; Uruguay was colonized by Europeans later than its neighboring countries.

The Spanish founded Montevideo as a military stronghold in the early 18th century due to competing claims over the region, while Uruguay won its independence between 1811 and 1828, following a four-way struggle between Portugal and Spain, and later Argentina and Brazil. It remained subject to foreign influence and intervention throughout the first half of the 19th century.[14] From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, numerous pioneering economic, labor, and social reforms were implemented, which led to the creation of a highly developed welfare state, which is why the country began to be known as "Switzerland of the Americas".[15] However, a series of economic crises and the fight against far-left urban guerrilla warfare in the late 1960s and early 1970s culminated in the 1973 coup d'état, which established a civic-military dictatorship until 1985.[16] Uruguay is today a democratic constitutional republic, with a president who serves as both head of state and head of government.

Uruguay is described as a "full democracy" and is highly ranked in international measurements of government transparency, economic freedom, social progress, income equality, per capita income, innovation, and infrastructure.[17][18] The country has fully legalized cannabis (the first country in the world to do so), as well as same-sex marriage and abortion. It is a founding member of the United Nations, OAS, and Mercosur.

Etymology

[edit]The country of Uruguay takes its name from the Río Uruguay, from the Indigenous Guaraní language. There are several interpretations, including "bird-river" ("the river of the uru, via Charruan, urú being a common noun for any wild fowl).[19][20] The name could also refer to a river snail called uruguá (Pomella megastoma) that was plentiful across its shores.[21]

One of the most popular interpretations of the name was proposed by the renowned Uruguayan poet Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, "the river of painted birds";[22] this interpretation, although dubious, still holds an important cultural significance in the country.[23]

In Spanish colonial times and for some time thereafter, Uruguay and some neighboring territories were called Banda Oriental [del Uruguay] ("Eastern Bank [of the Uruguay River]"), then for a few years the "Eastern Province". Since its independence, the country has been known as "República Oriental del Uruguay", which literally translates to "Republic East of the Uruguay [River]". However, it is officially translated either as the "Oriental Republic of Uruguay"[24][25] or the "Eastern Republic of Uruguay".[26]

History

[edit]

Pre-colonial

[edit]Uruguay was first inhabited around 13,000 years ago by hunter-gatherers.[13] It is estimated that at the time of the first contact with Europeans in the 16th century, there were about 9,000 Charrúa and 6,000 Chaná and some Guaraní island settlements.[27]

There is an extensive archeological collection of man-made tumuli known as "Cerritos de Indios" in the eastern part of the country, some of them dating back to 5,000 years ago. Very little is known about the people who built them as they left no written record, but evidence has been found in place of pre-Columbian agriculture and of extinct pre-Columbian dogs.[28]

Early colonization

[edit]

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to enter the region of present-day Uruguay in 1512.[29][30] The Spanish arrived in present-day Uruguay in 1515 but were the first to set foot in the area, claiming it for the crown.[31] The indigenous peoples' fierce resistance to conquest, combined with the absence of valuable resources, limited European settlement in the region during the 16th and 17th centuries.[31] Uruguay then became a zone of contention between the Spanish and Portuguese empires. In 1603, the Spanish began introducing cattle, which became a source of regional wealth. The first permanent Spanish settlement was founded in 1624 at Soriano on the Río Negro. In 1669–71, the Portuguese built a fort at Colonia del Sacramento (Colônia do Sacramento).

Montevideo, the current capital of Uruguay, was founded by the Spanish in the early 18th century as a military stronghold. Its natural harbor soon developed into a commercial area competing with Río de la Plata's capital, Buenos Aires.[31] Uruguay's early 19th-century history was shaped by ongoing fights for dominance in the Platine region[31] between British, Spanish, Portuguese, and other colonial forces. In 1806 and 1807, the British army attempted to seize Buenos Aires and Montevideo as part of the Napoleonic Wars. Montevideo was occupied by British forces from February to September 1807.

Independence struggle

[edit]

In 1811, José Gervasio Artigas, who became Uruguay's national hero, launched a successful revolt against the Spanish authorities, defeating them on 18 May at the Battle of Las Piedras.[31] In 1813, the new government in Buenos Aires convened a constituent assembly where Artigas emerged as a champion of federalism, demanding political and economic autonomy for each area and the Banda Oriental in particular.[32] The assembly refused to seat the delegates from the Banda Oriental; however, Buenos Aires pursued a system based on unitary centralism.[32]

As a result, Artigas broke with Buenos Aires and besieged Montevideo, taking the city in early 1815.[32] Once the troops from Buenos Aires had withdrawn, the Banda Oriental appointed its first autonomous government.[32] Artigas organized the Federal League under his protection, consisting of six provinces, five of which later became part of Argentina.[32]

In 1816, 10,000 Portuguese troops invaded the Banda Oriental from Brazil; they took Montevideo in January 1817.[32] After nearly four more years of struggle, the Portuguese Kingdom of Brazil annexed the Banda Oriental as a province under the name of "Cisplatina".[32] The Brazilian Empire became independent of Portugal in 1822. In response to the annexation, the Thirty-Three Orientals, led by Juan Antonio Lavalleja, declared independence on 25 August 1825, supported by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina).[31] This led to the 500-day-long Cisplatine War. Neither side gained the upper hand, and in 1828, the Treaty of Montevideo, fostered by the United Kingdom through the diplomatic efforts of Viscount John Ponsonby, gave birth to Uruguay as an independent state. 25 August is celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[33] The nation's first constitution was adopted on 18 July 1830.[31]

19th century

[edit]

At the time of independence, Uruguay had an estimated population of just under 75,000.[34] The political scene in Uruguay became split between two parties: the conservative Blancos (Whites), headed by the second President Manuel Oribe, representing the agricultural interests of the countryside, and the liberal Colorados (Reds), led by the first President Fructuoso Rivera, representing the business interests of Montevideo. The Uruguayan parties received support from warring political factions in neighboring Argentina, which became involved in Uruguayan affairs.

The Colorados favored the exiled Argentine liberal Unitarios, many of whom had taken refuge in Montevideo, while the Blanco president Manuel Oribe was a close friend of the Argentine ruler Manuel de Rosas. On 15 June 1838, an army led by the Colorado leader Rivera overthrew President Oribe, who fled to Argentina.[34] Rivera declared war on Rosas in 1839. The conflict would last 13 years and become known as the Guerra Grande (the Great War).[34] In 1843, an Argentine army overran Uruguay on Oribe's behalf but failed to take the capital. The siege of Montevideo, began in February 1843 and lasted nine years.[35] The besieged Uruguayans called on resident foreigners for help, which led to a French and an Italian legion being formed, the latter led by the exiled Giuseppe Garibaldi.[35]

In 1845, Britain and France intervened against Rosas to restore commerce to normal levels in the region. Their efforts proved ineffective, and by 1849, tired of the war, both withdrew after signing a treaty favorable to Rosas.[35] It appeared that Montevideo would finally fall when an uprising against Rosas, led by Justo José de Urquiza, governor of Argentina's Entre Ríos Province, began. The Brazilian intervention in May 1851 on behalf of the Colorados, combined with the uprising, changed the situation, and Oribe was defeated. The siege of Montevideo was lifted, and the Guerra Grande finally came to an end.[35] Montevideo rewarded Brazil's support by signing treaties that confirmed Brazil's right to intervene in Uruguay's internal affairs.[35]

In accordance with the 1851 treaties, Brazil intervened militarily in Uruguay as often as it deemed necessary.[36] In 1865, the Triple Alliance was formed by the emperor of Brazil, the president of Argentina, and the Colorado general Venancio Flores, the Uruguayan head of government whom they both had helped to gain power. The Triple Alliance declared war on the Paraguayan leader Francisco Solano López.[36] The resulting Paraguayan War ended with the invasion of Paraguay and its defeat by the armies of the three countries. Montevideo was used as a supply station by the Brazilian navy, and it experienced a period of prosperity and relative calm during the war.[36]

The first railway line was assembled in Uruguay in 1867, and a branch consisting of a horse-drawn train was opened. The present-day State Railways Administration of Uruguay maintains 2,900 km of extendable railway network.[37]

The constitutional government of General Lorenzo Batlle y Grau (1868–72) suppressed the Revolution of the Lances by the Blancos.[38] After two years of struggle, a peace agreement was signed in 1872 that gave the Blancos a share in the emoluments and functions of government through control of four of the departments of Uruguay.[38] This establishment of the policy of co-participation represented the search for a new formula of compromise based on the coexistence of the party in power and the opposition party.[38] Despite this agreement, the Colorado rule was threatened by the failed Tricolor Revolution in 1875 and the Revolution of the Quebracho in 1886.

The Colorado effort to reduce Blancos to only three departments caused a Blanco uprising of 1897, which ended with creating 16 departments, of which the Blancos now had control over six. Blancos were given ⅓ seats in Congress.[39] This division of power lasted until President Jose Batlle y Ordonez instituted his political reforms, which caused the last uprising by Blancos in 1904 that ended with the Battle of Masoller and the death of Blanco leader Aparicio Saravia.

Between 1875 and 1890, the military became the center of power.[40] During this authoritarian period, the government took steps toward the organization of the country as a modern state, encouraging its economic and social transformation. Pressure groups (consisting mainly of businessmen, hacendados, and industrialists) were organized and had a strong influence on the government.[40] A transition period (1886–90) followed, during which politicians began recovering lost ground, and some civilian participation in government occurred.[40] After the Guerra Grande, there was a sharp rise in the number of immigrants, primarily from Italy and Spain. By 1879, the total population of the country was over 438,500.[41] The economy reflected a steep upswing (if demonstrated graphically, above all other related economic determinants) in livestock raising and exports.[41] Montevideo became a major financial center of the region and an entrepôt for goods from Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay.[41]

20th century

[edit]

The Colorado leader José Batlle y Ordóñez was elected president in 1903.[42] The following year, the Blancos led a rural revolt, and eight bloody months of fighting ensued before their leader, Aparicio Saravia, was killed in battle. Government forces emerged victorious, leading to the end of the co-participation politics that had begun in 1872.[42] Batlle had two terms (1903–07 and 1911–15) during which he instituted major reforms, such as a welfare program, government participation in the economy, and a plural executive.[31]

Gabriel Terra became president in March 1931. His inauguration coincided with the effects of the Great Depression,[43] and the social climate became tense as a result of the lack of jobs. There were confrontations in which police and leftists died.[43] In 1933, Terra organized a coup d'état, dissolving the General Assembly and governing by decree.[43] A new constitution was promulgated in 1934, transferring powers to the president.[43] In general, the Terra government weakened or neutralized economic nationalism and social reform.[43]

In 1938, general elections were held, and Terra's brother-in-law, General Alfredo Baldomir, was elected president. Under pressure from organized labor and the National Party, Baldomir advocated free elections, freedom of the press, and a new constitution.[44] Although Baldomir declared Uruguay neutral in 1939, British warships and the German ship Admiral Graf Spee fought a battle not far off Uruguay's coast.[44] The Admiral Graf Spee took refuge in Montevideo, claiming sanctuary in a neutral port, but was later ordered out.[44]

In 1945, Uruguay formally signed the Declaration by the United Nations and entered World War II, leading the country to declare war on Germany and Japan. Following the end of the war, it became a founding member of the United Nations.

An armed group of Marxist–Leninist urban guerrillas, known as the Tupamaros, emerged in the 1960s, engaging in activities such as bank robbery, kidnapping, and assassination, in addition to attempting an overthrow of the government.[45][46]

Civic-military and dictatorship regime

[edit]

President Jorge Pacheco declared a state of emergency in 1968, followed by a further suspension of civil liberties in 1972. In 1973, amid increasing economic and political turmoil, the armed forces, asked by President Juan María Bordaberry, disbanded Parliament and established a civilian-military regime.[31] The CIA-backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of opponents was called Operation Condor.[47][48]

According to one source, around 180 Uruguayans are known to have been killed and disappeared, with thousands more illegally detained and tortured during the 12-year civil-military rule from 1973 to 1985.[49] Most were killed in Argentina and other neighboring countries, with 36 of them having been killed in Uruguay.[50] According to Edy Kaufman (cited by David Altman[51]), Uruguay at the time had the highest per capita number of political prisoners in the world. "Kaufman, who spoke at the U.S. Congressional Hearings of 1976 on behalf of Amnesty International, estimated that one in every five Uruguayans went into exile, one in fifty were detained, and one in five hundred went to prison (most of them tortured)." Social spending was reduced, and many state-owned companies were privatized. However, the economy did not improve and deteriorated after 1980; the gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 20%, and unemployment rose to 17%. The state intervened by trying to bail out failing companies and banks.[52]: 45

Return to democracy (1984–present)

[edit]

A new constitution, drafted by the military, was rejected in a November 1980 referendum.[31] Following the referendum, the armed forces announced a plan for the return to civilian rule, and national elections were held in 1984.[31] Colorado Party leader Julio María Sanguinetti won the presidency and served from 1985 to 1990. The first Sanguinetti administration implemented economic reforms and consolidated democracy following the country's years under military rule.[31] The National Party's Luis Alberto Lacalle won the 1989 presidential election, and a referendum endorsed amnesty for human rights abusers. Sanguinetti was then re-elected in 1994.[53] Both presidents continued the economic structural reforms initiated after the reinstatement of democracy.[54]

The 1999 national elections were held under a new electoral system established by a 1996 constitutional amendment.[55] Colorado Party candidate Jorge Batlle, aided by the support of the National Party, defeated Broad Front candidate Tabaré Vázquez. The formal coalition ended in November 2002, when the Blancos withdrew their ministers from the cabinet,[31] although the Blancos continued to support the Colorados on most issues. Low commodity prices and economic difficulties in Uruguay's main export markets (starting in Brazil with the devaluation of the real, then in Argentina in 2002) caused a severe recession; the economy contracted by 11%, unemployment climbed to 21%, and the percentage of Uruguayans in poverty rose to over 30%.[56]

In 2004, Uruguayans elected Tabaré Vázquez as president while giving the Broad Front a majority in both houses of Parliament.[57] Vázquez stuck to economic orthodoxy. As commodity prices soared and the economy recovered from the recession, he tripled foreign investment, cut poverty and unemployment, cut public debt from 79% of GDP to 60%, and kept inflation steady.[58] In 2009, José Mujica, a former left-wing guerrilla leader (Tupamaros) who spent almost 15 years in prison during the country's military rule, emerged as the new president as the Broad Front won the election for a second time.[59][60] Abortion was legalized in 2012,[61] followed by same-sex marriage[62] and cannabis in the following year,[63] making Uruguay the first country in the modern era to legalize cannabis.

In 2014, Tabaré Vázquez was elected to a non-consecutive second presidential term, which began on 1 March 2015.[64] In 2020, after 15 years of left-wing rule, he was succeeded by Luis Alberto Lacalle Pou, a member of the conservative National Party, as the 42nd President of Uruguay.[65]

Geography

[edit]

With 176,214 km2 (68,037 sq mi) of continental land and 142,199 km2 (54,903 sq mi) of jurisdictional water and small river islands,[66] Uruguay is the second smallest sovereign nation in South America (after Suriname) and the third smallest territory (French Guiana is the smallest).[67] The landscape features mostly rolling plains and low hill ranges (cuchillas) with a fertile coastal lowland.[67] Uruguay has 660 km (410 mi) of coastline.[67] The highest point in the country is the Cerro Catedral, whose peak reaches 514 metres (1,686 ft) AMSL in the Sierra Carapé hill range. To the southwest is the Río de la Plata, the estuary of the Uruguay River (the river which forms the country's western border).

A dense fluvial network covers the country, consisting of four river basins, or deltas: the Río de la Plata Basin, the Uruguay River, the Laguna Merín, and the Río Negro. The major internal river is the Río Negro ('Black River') which was dammed in 1945, resulting in the formation of the artificial Rincón del Bonete Lake in the centre of Uruguay. Several lagoons are found along the Atlantic coast.

Montevideo is the southernmost national capital in the Americas and the third most southerly in the world (after Canberra and Wellington). Uruguay is the only country in South America situated entirely south of the Tropic of Capricorn, and is the southernmost sovereign state in the world when ordered by northernmost point of latitude. There are ten national parks in Uruguay: Five in the wetland areas of the east, three in the central hill country, and one in the west along the Rio Uruguay. Uruguay is home to the Uruguayan savanna terrestrial ecoregion.[68] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.61/10, ranking it 147th globally out of 172 countries.[69]

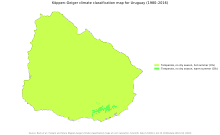

Climate

[edit]

Located entirely within the southern temperate zone, Uruguay has a climate that is relatively mild and fairly uniform nationwide.[70] According to the Köppen climate classification, most of the country has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Only in some spots of the Atlantic Coast and at the summit of the highest hills of the Cuchilla Grande the climate is oceanic (Cfb).

The country experiences four seasons, with summer from December to March and winter from June to September. Seasonal variations are pronounced, but extremes in temperature are rare.[70] Summers are tempered by winds off the Atlantic, and severe cold in winter is unknown.[70][71] Although it never gets too cold, frosts occur every year during the winter months, and precipitation such as sleet and hail occur almost every winter, but snow is very rare; it does occur every couple of years at higher elevations, but almost always without accumulation. As would be expected with its abundance of water, high humidity, and fog are common.[70]

The absence of mountains, which act as weather barriers, makes all locations vulnerable to high winds and rapid changes in weather as fronts or storms sweep across the country.[70] These storms can be strong; they can bring squalls, hail, and sometimes even tornadoes.[72] The country experiences extratropical cyclones but no tropical cyclones, due to the fact that the South Atlantic Ocean is rarely warm enough for their development. Both summer and winter weather may vary from day to day with the passing of storm fronts, where a hot northerly wind may occasionally be followed by a cold wind (pampero) from the Argentine Pampas.[25]

Even though both temperature and precipitation are quite uniform nationwide, there are considerable differences across the territory. The average annual temperature of the country is 17.5 °C (63.5 °F), ranging from 16 °C (61 °F) in the southeast to 19 °C (66 °F) in the northwest.[73] Winter temperatures range from a daily average of 11 °C (52 °F) in the south to 14 °C (57 °F) in the north, while summer average daily temperatures range from 21 °C (70 °F) in the southeast to 25 °C (77 °F) in the northwest.[74] The southeast is considerably cooler than the rest of the country, especially during spring, when the ocean with cold water after the winter cools down the temperature of the air and brings more humidity to that region. However, the south of the country receives less precipitation than the north. For example, Montevideo receives approximately 1,100 millimetres (43 in) of precipitation per year, while the city of Rivera in the northeast receives 1,600 millimetres (63 in).[73] The heaviest precipitation occurs during the autumn months, although more frequent rainy spells occur in winter.[25] But periods of drought or excessive rain can occur anytime during the year.

National extreme temperatures at sea level are, 44 °C (111 °F) in Paysandú city (20 January 1943) and Florida city (14 January 2022),[75] and −11.0 °C (12.2 °F) in Melo city (14 June 1967).[76]

Government and politics

[edit]

Uruguay is a representative democratic republic with a presidential system.[77] The members of government are elected for a five-year term by a universal suffrage system.[77] Uruguay is a unitary state: justice, education, health, security, foreign policy and defense are all administered nationwide.[77] The executive power is exercised by the president and a cabinet of 14 ministers.[77]

The legislative power is constituted by the General Assembly, composed of two chambers: the Chamber of Representatives, consisting of 99 members representing the 19 departments, elected for a five-year term based on proportional representation; and the Chamber of Senators, consisting of 31 members, 30 of whom are elected for a five-year term by proportional representation, and the vice-president, who presides over the chamber and has the right to vote.[77]

The judicial arm is exercised by the Supreme Court, the Bench, and Judges nationwide. The members of the Supreme Court are elected by the General Assembly; the members of the Bench are selected by the Supreme Court with the consent of the Senate, and the Judges are directly assigned by the Supreme Court.[77]

Uruguay adopted its current constitution in 1967.[78][79] Many of its provisions were suspended in 1973, but re-established in 1985. Drawing on Switzerland and its use of the initiative, the Uruguayan Constitution also allows citizens to repeal laws or to change the constitution by popular initiative, which culminates in a nationwide referendum. This method has been used several times over the past 15 years: to confirm a law renouncing prosecution of members of the military who violated human rights during the military regime (1973–1985); to stop privatization of public utility companies; to defend pensioners' incomes; and to protect water resources.[80]

For most of Uruguay's history, the Partido Colorado has been in government.[81][82] However, in the 2004 Uruguayan general election, the Broad Front won an absolute majority in Parliamentary elections, and in 2009, José Mujica of the Broad Front defeated Luis Alberto Lacalle of the Blancos to win the presidency. In March 2020, Uruguay got a conservative government, meaning the end of 15 years of left-wing leadership under the Broad Front coalition. At the same time, centre-right National Party's Luis Lacalle Pou was sworn in as the new President of Uruguay.[83]

A 2010 Latinobarómetro poll found that, within Latin America, Uruguayans are among the most supportive of democracy and by far the most satisfied with the way democracy works in their country.[84] Uruguay ranked 27th in the Freedom House "Freedom in the World" index. According to the V-Dem Democracy indices in 2023, Uruguay ranked 31st in the world on electoral democracy and 2nd behind Switzerland on citizen-initiated direct democracy.[85] Uruguay shared 14th place along with Canada, Estonia, and Iceland as least corrupt in the World Corruption Perceptions Index composed by Transparency International in 2022, beating out countries such as the UK, Belgium, and Japan.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Uruguay is divided into 19 departments whose local administrations replicate the division of the executive and legislative powers.[77] Each department elects its own authorities through a universal suffrage system.[77] The departmental executive authority resides in a superintendent and the legislative authority in a departmental board.[77]

| Department | Capital | Area | Population (2011 census)[86] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | |||

| Artigas | Artigas | 11,928 | 4,605 | 73,378 |

| Canelones | Canelones | 4,536 | 1,751 | 520,187 |

| Cerro Largo | Melo | 13,648 | 5,270 | 84,698 |

| Colonia | Colonia del Sacramento | 6,106 | 2,358 | 123,203 |

| Durazno | Durazno | 11,643 | 4,495 | 57,088 |

| Flores | Trinidad | 5,144 | 1,986 | 25,050 |

| Florida | Florida | 10,417 | 4,022 | 67,048 |

| Lavalleja | Minas | 10,016 | 3,867 | 58,815 |

| Maldonado | Maldonado | 4,793 | 1,851 | 164,300 |

| Montevideo | Montevideo | 530 | 200 | 1,319,108 |

| Paysandú | Paysandú | 13,922 | 5,375 | 113,124 |

| Río Negro | Fray Bentos | 9,282 | 3,584 | 54,765 |

| Rivera | Rivera | 9,370 | 3,620 | 103,493 |

| Rocha | Rocha | 10,551 | 4,074 | 68,088 |

| Salto | Salto | 14,163 | 5,468 | 124,878 |

| San José | San José de Mayo | 4,992 | 1,927 | 108,309 |

| Soriano | Mercedes | 9,008 | 3,478 | 82,595 |

| Tacuarembó | Tacuarembó | 15,438 | 5,961 | 90,053 |

| Treinta y Tres | Treinta y Tres | 9,529 | 3,679 | 48,134 |

| Total[note 1] | — | 175,016 | 67,574 | 3,286,314 |

Foreign relations

[edit]

The country's foreign policy is directed by the Ministry of Foreign Relations.[88] Uruguay has traditionally had strong political and cultural ties with its neighboring countries and with Europe, and its international relations have been guided by the principles of non-intervention and multilateralism.[89] The country is a founding member of international organizations such as the United Nations, the Organization of American States, the Southern Common Market, and the Latin American Integration Association.[90] The headquarters of the latter two are located in its capital Montevideo, for which the role of the city has been compared to that of Brussels in Europe.[91]

Uruguay has two uncontested boundary disputes with Brazil, over Isla Brasilera and the 235 km2 (91 sq mi) Invernada River region near Masoller. The two countries disagree on which tributary represents the legitimate source of the Quaraí/Cuareim River, which would define the border in the latter disputed section, according to the 1851 border treaty between the two countries.[67] The disputed areas remain de facto under Brazilian control, with little to no actual effort by Uruguay to assert its claims. Both countries have friendly diplomatic relations and strong economic ties.

Uruguay is also a founding member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS), a voluntary and informal grouping at the UN.[92] The country has friendly relations with the United States since its transition back to democracy.[56] Commercial ties between both countries have expanded with the signing of a bilateral investment treaty in 2004 and a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement in January 2007.[56] The United States and Uruguay have also cooperated on military matters, with both countries playing significant roles in the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti.[56] In 2017, Uruguay signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[93] It also rejoined the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR or "Rio Pact") in 2020.[94] Uruguay is the 52nd most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[95]

Military

[edit]The Uruguayan Armed Forces are constitutionally subordinate to the president of the Republic, through the minister of defense.[31] Armed forces personnel number about 18,000 for the Army,[96] 6,000 for the Navy, and 3,000 for the Air Force.[31] Enlistment is voluntary in peacetime, but the government has the authority to conscript in emergencies.[67]

Uruguay ranks first in the world on a per capita basis for its contributions to the United Nations peacekeeping forces, with 2,513 soldiers and officers in 10 UN peacekeeping missions.[31] As of February 2010, Uruguay had 1,136 military personnel deployed to Haiti in support of MINUSTAH and 1,360 deployed in support of MONUC in the Congo.[31] In December 2010, Uruguayan Major General Gloodtdofsky, was appointed Chief Military Observer and head of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan.[97]

Since May 2009, homosexuals have been allowed to serve in the military after the defense minister signed a decree stating that military recruitment policy would no longer discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation.[98] In the fiscal year 2010, the United States provided Uruguay with $1.7 million in military assistance, including $1 million in Foreign Military Financing and $480,000 in International Military Education and Training.[56]

Law enforcement

[edit]

Economy

[edit]

In 1991, the country experienced an increase in strikes to obtain wage compensation to offset inflation and to oppose the privatizations desired by the government of Luis Alberto Lacalle. A general strike was called in 1992, and the privatization policy was widely rejected by the referendum.[101] In 1994 and 1995, Uruguay faced economic difficulties caused by the liberalization of foreign trade, which increased the trade deficit.[102] The Montevideo Gas Company and the Pluna airline were turned over to the private sector, but the pace of privatization slowed down in 1996. Uruguay experienced a major economic and financial crisis between 1999 and 2002, principally a spillover effect from the economic problems of Argentina.[56] The economy contracted by 11%, and unemployment climbed to 14–21%.[103][56]

In 2004, the Batlle government signed a three-year $1.1 billion stand-by arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), committing the country to a substantial primary fiscal surplus, low inflation, considerable reductions in external debt, and several structural reforms designed to improve competitiveness and attract foreign investment.[56] Uruguay terminated the agreement in 2006 following the early repayment of its debt but maintained a number of the policy commitments.[56] Vázquez, who assumed the government in March 2005, created the Ministry of Social Development and sought to reduce the country's poverty rate with a $240 million National Plan to Address the Social Emergency (PANES), which provided a monthly conditional cash transfer of approximately $75 to over 100,000 households in extreme poverty. In exchange, those receiving the benefits were required to participate in community work, ensure that their children attended school daily, and have regular health check-ups.[56]

Following the 2001 Argentine credit default, prices in the Uruguayan economy made a variety of services, including information technology and architectural expertise, once too expensive in many foreign markets, exportable.[104] The Frente Amplio government, while continuing payments on Uruguay's external debt,[105] also undertook an emergency plan to attack the widespread problems of poverty and unemployment.[106] The economy grew at an annual rate of 6.7% during the 2004–2008 period.[107] Uruguay's export markets have been diversified to reduce dependency on Argentina and Brazil.[107] Poverty was reduced from 33% in 2002 to 21.7% in July 2008, while extreme poverty dropped from 3.3% to 1.7%.[107]

Between the years 2007 and 2009, Uruguay was the only country in the Americas that did not technically experience a recession (two consecutive downward quarters).[108] Unemployment reached a record low of 5.4% in December 2010 before rising to 6.1% in January 2011.[109] While unemployment is still at a low level, the IMF observed a rise in inflationary pressures,[110] and Uruguay's GDP expanded by 10.4% for the first half of 2010.[111] According to IMF estimates, Uruguay was probably to achieve growth in real GDP of between 8% and 8.5% in 2010, followed by 5% growth in 2011 and 4% in subsequent years.[110] Gross public sector debt contracted in the second quarter of 2010, after five consecutive periods of sustained increase, reaching $21.885 billion US dollars, equivalent to 59.5% of the GDP.[112]

Uruguay was ranked 62nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[113] The number of union members has quadrupled since 2003, rising from 110,000 to more than 400,000 in 2015 for a working population of 1.5 million.[114] According to the International Trade Union Confederation, Uruguay has "ratified all eight core ILO labour Conventions".[115] The growth, use, and sale of cannabis were legalized on 11 December 2013,[116] making Uruguay the first country in the world to fully legalize marijuana. The law was voted on at the Uruguayan Senate on the same date with 16 votes to approve it and 13 against.

Agriculture

[edit]

In 2010, Uruguay's export-oriented agricultural sector contributed to 9.3% of the GDP and employed 13% of the workforce.[67] Official statistics from Uruguay's Agriculture and Livestock Ministry indicate that meat and sheep farming in Uruguay occupies 59.6% of the land. The percentage further increases to 82.4% when cattle breeding is linked to other farm activities such as dairy, forage, and rotation with crops such as rice.[117]

According to FAOSTAT, Uruguay is one of the world's largest producers of soybeans (9th), wool (12th), horse meat (14th), beeswax (14th), and quinces (17th). Most farms (25,500 out of 39,120) are family-managed; beef and wool represent the main activities and main source of income for 65% of them, followed by vegetable farming at 12%, dairy farming at 11%, hogs at 2%, and poultry also at 2%.[117] Beef is the main export commodity of the country, totaling over US$1 billion in 2006.[117]

In 2007, Uruguay had cattle herds totalling 12 million head, making it the country with the highest number of cattle per capita at 3.8.[117] However, 54% is in the hands of 11% of farmers, who have a minimum of 500 head. At the other extreme, 38% of farmers exploit small lots and have herds averaging below one hundred head.[117]

Tourism

[edit]

The tourism industry in Uruguay is an important part of its economy. In 2012, the sector was estimated to account for 97,000 jobs and (directly and indirectly) 9% of GDP.[118] Uruguay is the Latin American country that receives the most tourists in relation to its population. In 2023, 3.8 million tourists entered Uruguay, of which the majority were Argentines and Brazilians, followed by Chileans, Paraguayans, Americans and Europeans of various nationalities.[119]

Cultural experiences in Uruguay include exploring the country's colonial heritage, as found in Colonia del Sacramento. Historical monuments include Torres García Museum and Estadio Centenario. One of the main natural attractions in Uruguay is Punta del Este. Punta del Este is situated on a small peninsula off the southeast coast of Uruguay. Its beaches are divided into Mansa, or tame (river) side and Brava, or rugged (ocean) side. Punta del Este adjoins the city of Maldonado, while to its northeast along the coast are found the smaller resorts of La Barra and José Ignacio.[120]

Transportation

[edit]

The Port of Montevideo is one of the major container terminal port; it handles over 1.1 million containers annually.[121] Its quay can handle 14-metre draught (46 ft) vessels. Nine straddle cranes allow for 80 to 100 movements per hour.[121] The port of Nueva Palmira is a major regional merchandise transfer point and houses both private and government-run terminals.[122]

Air

[edit]Carrasco International Airport was initially inaugurated in 1947, and in 2009, Puerta del Sur, the airport owner and operator, commissioned Rafael Viñoly Architects to expand and modernize the existing facilities with a spacious new passenger terminal with an investment of $165 million.[123][124] The airport can handle up to 4.5 million users per year.[123] PLUNA was the flag carrier of Uruguay and was headquartered in Carrasco.[125][126]

The Punta del Este International Airport, located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Punta del Este in the Maldonado Department, is the second busiest air terminal in Uruguay, built by the Uruguayan architect Carlos Ott. It was inaugurated in 1997.[122]

Land

[edit]The Administración de Ferrocarriles del Estado is the autonomous agency in charge of rail transport and the maintenance of the railroad network. Uruguay has about 1,200 km (750 mi) of operational railroad track.[67] Until 1947, about 90% of the railroad system was British-owned.[127] In 1949, the government nationalized the railways, along with the electric trams and the Montevideo Waterworks Company.[127] However, in 1985, the "National Transport Plan" suggested passenger trains were too costly to repair and maintain.[127] Cargo trains would continue, but bus transportation became the "economic" alternative for travellers.[127] Passenger service was then discontinued in 1988.[127] However, rail passenger commuter service into Montevideo was restarted in 1993, and now comprises three suburban lines.

Surfaced roads connect Montevideo to the other urban centers in the country, the main highways leading to the border and neighboring cities. Numerous unpaved roads connect farms and small towns. Overland trade has increased markedly since Mercosur (Southern Common Market) was formed in the 1990s and again in the later 2000s.[128] Most of the country's domestic freight and passenger service is by road rather than rail. The country has several international bus services[129] connecting the capital and frontier localities to neighboring countries.[130] These include 17 destinations in Argentina,[note 2] 12 destinations in Brazil[note 3] and the capital cities of Chile and Paraguay.[131]

Telecommunications

[edit]The telecommunications industry is more developed than in most other Latin American countries, being the first country in the Americas to achieve complete digital telephone coverage in 1997. The system is government-owned, and there have been controversial proposals to partially privatize it since the 1990s.[132]

The mobile phone market is shared by the state-owned ANTEL and two private companies, Movistar and Claro. The ANTEL has the largest market share at 49% of Uruguay's mobile lines.[133] ANTEL has launched a commercial 5G network in April 2019[134] with still continual development.[135] While Movistar and Claro have only 30% and 21% of the market share, respectively.[136] The Google Search engine accounted for 95% of total search engine market share in 2023–2024.[137]

Energy

[edit]In 2010, the Ministry of Energy, Mining and Industry of Uruguay approved Decree 354 on the Promotion of Renewable Energies.[138] In 2021, Uruguay had, in terms of installed renewable electricity, 1,538 MW in hydropower, 1,514 MW in wind power (35th largest in the world), 258 MW in solar power (66th largest in the world), and 423 MW in biomass.[139] In 2023, 98% of Uruguay's electricity comes from renewable energy.[140] The dramatic shift, taking less than ten years and without government funding, lowered electricity costs and slashed the country's carbon footprint.[141][142] Most of the electricity comes from hydroelectric facilities and wind parks. Uruguay no longer imports electricity.[143] In 2022, 49% of the country's total carbon dioxide emissions came from the burning of diesel fuel, followed by gasoline, with a 25% share.[144]

Demographics

[edit]Uruguayans are of predominantly European origin, with over 87.7% of the population claiming European descent in the 2011 census.[145] Most Uruguayans of European ancestry are descendants of 19th and 20th century immigrants from Spain and Italy,[31] and to a lesser degree Germany, France, and Britain.[25] Earlier settlers had migrated from Argentina.[25] People of African descent make up around five percent of the total.[25] There are also important communities of Japanese.[146] Overall, the ethnic composition is similar to neighboring Argentine provinces as well as Southern Brazil.[147]

From 1963 to 1985, an estimated 320,000 Uruguayans emigrated.[148] The most popular destinations for Uruguayan emigrants are Argentina, followed by the United States, Australia, Canada, Spain, Italy, and France.[148] In 2009, for the first time in 44 years, the country saw an overall positive influx when comparing immigration to emigration. 3,825 residence permits were awarded in 2009, compared with 1,216 in 2005.[149] 50% of new legal residents come from Argentina and Brazil. A migration law passed in 2008 gives immigrants the same rights and opportunities that nationals have, with the requisite of proving a monthly income of $650.[149]

Metropolitan Montevideo is the only large city, with around 1.9 million inhabitants, or more than half the country's total population. The rest of the urban population lives in about 30 towns.[31] Uruguay's rate of population growth is much lower than in other Latin American countries.[25] Its median age is 35.3 years, higher than the global average[31] due to its low birth rate, high life expectancy, and relatively high rate of emigration among younger people. A quarter of the population is less than 15 years old, and about a sixth are aged 60 and older.[25] In 2017, the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Uruguay was 1.70 children born per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1. It remains considerably below the high of 5.76 children born per woman in 1882.[150]

A 2017 IADB report on labor conditions for Latin American nations ranked Uruguay as the region's leader overall in all but one subindexes, including gender, age, income, formality, and labor participation.[151]

Largest cities

[edit]| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Montevideo  Salto |

1 | Montevideo | Montevideo | 1,304,687 | 11 | Artigas | Artigas | 40,657 |  Ciudad de la Costa  Paysandú |

| 2 | Salto | Salto | 104,011 | 12 | Minas | Lavalleja | 38,446 | ||

| 3 | Ciudad de la Costa | Canelones | 95,176 | 13 | San José de Mayo | San José | 36,743 | ||

| 4 | Paysandú | Paysandú | 76,412 | 14 | Durazno | Durazno | 34,368 | ||

| 5 | Las Piedras | Canelones | 71,258 | 15 | Florida | Florida | 33,639 | ||

| 6 | Rivera | Rivera | 64,465 | 16 | Barros Blancos | Canelones | 31,650 | ||

| 7 | Maldonado | Maldonado | 62,590 | 17 | Ciudad del Plata | San José | 31,145 | ||

| 8 | Tacuarembó | Tacuarembó | 54,755 | 18 | San Carlos | Maldonado | 27,471 | ||

| 9 | Melo | Cerro Largo | 51,830 | 19 | Colonia del Sacramento | Colonia | 26,231 | ||

| 10 | Mercedes | Soriano | 41,974 | 20 | Pando | Canelones | 25,947 | ||

Religion

[edit]

Christianity is the largest religion in Uruguay. The country has no official religion; church and state are officially separated,[31] and religious freedom is guaranteed. A 2008 survey by the INE of Uruguay showed Catholic Christianity as the main religion, with 45.7–81.4%[152] of the population; 9.0% are non-Catholic Christians, 0.6% are Animists or Umbandists (an Afro-Brazilian religion), and 0.4% are Jewish. 30.1% reported believing in a god, but not belonging to any religion, while 14% were atheists or agnostics.[153] Among the sizeable Armenian community in Montevideo, the dominant religion is Christianity, specifically Armenian Apostolic.[154]

Political observers consider Uruguay the most secular country in the Americas.[155] Uruguay's secularization began with the relatively minor role of the church in the colonial era, compared with other parts of the Spanish Empire. The small numbers of Uruguay's indigenous peoples and their resistance to proselytism reduced the influence of the ecclesiastical authorities.[156]

After independence, anti-clerical ideas spread to Uruguay, particularly from France, further eroding the influence of the church.[157] In 1837, civil marriage was recognized, and in 1861, the state took over the running of public cemeteries. In 1907, divorce was legalized, and in 1909, all religious instruction was banned from state schools.[156] Under the influence of the Colorado politician José Batlle y Ordóñez (1903–1911), complete separation of church and state was introduced with the new constitution of 1917.[156] Uruguay's capital has 12 synagogues and a community of 20,000 Jews as of 2011. With a peak of 50,000 during the mid-1960s, Uruguay has the world's highest rate of aliyah as a percentage of the Jewish population.[158]

Language

[edit]Spanish is the de facto national language.[159] Uruguayan Spanish, as a variant of Rioplatense, employs both voseo and yeísmo (with [ʃ] or [ʒ]) and has a great influence of the Italian language and its different dialects since it incorporates lunfardo.[160] In the border areas with Brazil in the northeast of the country, Uruguayan Portuguese is spoken, which consists of a mixture of Spanish with Brazilian Portuguese.[161] It is a dialect without formally defined orthography and without any official recognition.[162] English is the most widespread foreign language among the Uruguayan people, being part of the educational curriculum.[163]

As few indigenous people exist in the population, no indigenous languages are thought to remain in active use in the country.[164] Another spoken dialect was the Patois, which is an Occitan dialect. The dialect was spoken mainly in the Colonia Department, where the first pilgrims settled, in the city called La Paz. There are still written tracts of the language in the Waldensians Library (Biblioteca Valdense) in the town of Colonia Valdense, Colonia Department. Patois speakers arrived to Uruguay from the Piedmont. Originally, they were Vaudois who become Waldensians, giving their name to the city Colonia Valdense, which translated from the Spanish to mean "Waldensian Colony".[165]

In 2001, Uruguayan Sign Language (LSU) was recognized as an official language of Uruguay under Law 17.378.[4]

Education

[edit]

Education in Uruguay is secular, free,[166] and compulsory for 14 years, starting at the age of 4.[167] The system is divided into six levels of education: early childhood (3–5 years), primary (6–11 years), basic secondary (12–14 years), upper secondary (15–17 years), higher education (18 and up), and postgraduate education.[167] Public education is the primary responsibility of three institutions: the Ministry of Education and Culture, which coordinates education policies; the National Public Education Administration, which formulates and implements policies on early to secondary education; and the University of the Republic, responsible for higher education.[167] In 2009, the government planned to invest 4.5% of GDP in education.[166]

Uruguay ranks high on standardised tests such as PISA at a regional level but is also below some countries with similar levels of income to the OECD average.[166] In the 2006 PISA test, Uruguay had one of the greatest standard deviations among schools, suggesting significant variability by socio-economic level.[166] Uruguay is part of the One Laptop per Child project, and in 2009 it became the first country in the world to provide a laptop for every primary school student[168] as part of the Plan Ceibal.[169] Over the 2007–2009 period, 362,000 pupils and 18,000 teachers were involved in the scheme; around 70% of the laptops were given to children who did not have computers at home.[169] The OLPC programme represents less than 5% of the country's education budget.[169]

Culture

[edit]Uruguayan culture is strongly European and its influences from southern Europe are particularly important.[25] The tradition of the gaucho has been an important element in the art and folklore of both Uruguay and Argentina.[25]

Visual arts

[edit]

Abstract painter and sculptor Carlos Páez Vilaró was a prominent Uruguayan artist. He drew from both Timbuktu and Mykonos to create his best-known work: his home, hotel and atelier Casapueblo near Punta del Este.[170] The 19th-century painter Juan Manuel Blanes, whose works depict historical events,[171] was the first Uruguayan artist to gain widespread recognition. The Post-Impressionist painter Pedro Figari did pastel studies in Montevideo and the countryside.[172] Most of the paintings were part of the abstract trend, not muralism.[173]

Uruguay has many art museums, most of which are in Montevideo, such as the Torres García Museum and the Gurvich Museum.[174] The Torres García Museum was dedicated in honor of the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García.[175]

Music

[edit]

The folk and popular music of Uruguay shares its gaucho roots with Argentina and the tango.[25] One of the most famous tangos, "La cumparsita" (1917), was written by the Uruguayan composer Gerardo Matos Rodríguez.[25] The candombe is a folk dance performed at Carnival, especially Uruguayan Carnival, mainly by Uruguayans of African ancestry.[25] The guitar is the preferred musical instrument, and in a popular traditional contest called the payada, two singers, each with a guitar, take turns improvising verses to the same tune.[25] Folk music is called canto popular and includes some guitar players and singers such as Los Olimareños, and Numa Moraes.

There are numerous radio stations and musical events of rock music and the Caribbean genres.[25] Early classical music in Uruguay showed Spanish and Italian influence, but since the 20th century, a number of composers of classical music, including Eduardo Fabini, Héctor Tosar, and Eduardo Gilardoni, have made use of Latin American musical idioms more.[25] There are two symphony orchestras in Montevideo, OSSODRE and Filarmonica de Montevideo. Some of the well-known classical musicians are pianists Albert Enrique Graf; guitarists Eduardo Fernandez and Marco Sartor; and singers Erwin Schrott.

Tango has especially affected Uruguayan culture during the 20th century, particularly the 1930s and 1940s with Uruguayan singers such as Julio Sosa from Las Piedras.[176] When tango singer Carlos Gardel was 29 years old, he changed his nationality to be Uruguayan, saying he was born in Tacuarembó.[177] Nevertheless, a Carlos Gardel museum was established in 1999 in Valle Edén, near Tacuarembó.[178]

Rock and roll was first introduced into Uruguay with the arrival of the Beatles and other British bands in the early 1960s. A wave of bands appeared in Montevideo, including Los Shakers, Los Iracundos, Los Moonlights, and Los Malditos, of which all became major figures in the so-called Uruguayan Invasion of Argentina.[179] Popular Uruguayan rock bands include La Vela Puerca, El Cuarteto de Nos, and Cursi. In 2004, the Uruguayan musician and actor Jorge Drexler won an Academy Award for composing the song "Al otro lado del río" from the movie The Motorcycle Diaries, which narrated the life of Che Guevara.[180]

Food

[edit]Uruguayan food culture comes mostly from the European cuisine culture. Most of the Uruguayan dishes are from Spain, France, Italy, and Brazil, the result of immigration caused by past wars in Europe. Daily meals vary between meats, pasta of all types, rice, sweet desserts and others, with meat being the principal dish due to Uruguay being one of the world's largest producers of meat in quality.

Typical dishes include: "Asado uruguayo" (big grill or barbecue of all types of meat), roasted lamb, Chivito (sandwich containing thin grilled beef, lettuce, tomatoes, fried egg, ham, olives and others, and served with French fries), Milanesa (a kind of fried breaded beef), tortellini, spaghetti, gnocchi, ravioli, rice and vegetables.

One of the most consumed spreads in Uruguay is Dulce de leche (a caramel confection from Latin America prepared by slowly heating sugar and milk). The most typical sweet is Alfajor, which is a small cake, filled with Dulce de leche and covered with chocolate or meringue. Other typical desserts include the Pastafrola (a type of cake filled with quince jelly) and Chajá (meringue, sponge cake, whipped cream and fruits, typically peaches and strawberries are added). Mate, a herbal drink, is the most typical beverage in Uruguay.

Literature

[edit]

José Enrique Rodó (1871–1917), a modernist, is considered Uruguay's most significant literary figure.[25] His book, Ariel (1900), deals with the need to maintain spiritual values while pursuing material and technical progress.[25] It also stresses resisting cultural dominance by Europe and the United States.[25] Notable amongst Latin American playwrights is Florencio Sánchez (1875–1910), who wrote plays about contemporary social problems that are still performed today.[25]

From about the same period came the romantic poetry of Juan Zorrilla de San Martín (1855–1931), who wrote epic poems about Uruguayan history. Also notable are Juana de Ibarbourou (1895–1979), Delmira Agustini (1866–1914), Idea Vilariño (1920–2009), and the short stories of Horacio Quiroga and Juan José Morosoli (1899–1959).[25] The psychological stories of Juan Carlos Onetti (such as "No Man's Land" and "The Shipyard") have earned widespread critical praise, as have the writings of Mario Benedetti.[25]

Uruguay's best-known contemporary writer is Eduardo Galeano, author of Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971; "Open Veins of Latin America") and the trilogy Memoria del fuego (1982–87; "Memory of Fire").[25] Other modern Uruguayan writers include Sylvia Lago, Jorge Majfud, and Jesús Moraes.[25]

Media

[edit]The Reporters Without Borders worldwide press freedom index has ranked Uruguay as 19th of 180 reported countries in 2019.[181] Freedom of speech and media are guaranteed by the constitution, with qualifications for inciting violence or "insulting the nation".[106] Uruguay's freedom of the press was severely curtailed during the years of military dictatorship. On his first day in office in March 1985, Sanguinetti re-established complete freedom of the press.[182] Consequently, Montevideo's newspapers expanded their circulations.[182] Uruguayans have access to more than 100 private daily and weekly newspapers, more than 100 radio stations, and some 20 terrestrial television channels, and cable TV is widely available.[106]

State-run radio and TV are operated by the official broadcasting service SODRE.[106] Some newspapers are owned by, or linked to, the main political parties.[106] El Día was the nation's most prestigious paper until its demise in the early 1990s, founded in 1886 by the Colorado party leader and (later) president José Batlle y Ordóñez. El País, the paper of the rival Blanco Party, has the largest circulation.[25] Búsqueda serves as a forum for political and economic analysis.[182] Although it sells only about 16,000 copies a week, its estimated readership exceeds 50,000.[182]

Sport

[edit]

Football is the most popular sport in Uruguay. The first international match outside the British Isles was played between Uruguay and Argentina in Montevideo in July 1902.[183] Football was taken to Uruguay by English sailors and labourers in the late 19th century. Less successfully, they introduced rugby and cricket. Uruguay won gold at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games[184] and again in 1928 in Amsterdam.[185]

The Uruguay national football team has won the FIFA World Cup on two occasions. Uruguay won the inaugural tournament on home soil in 1930 and again in 1950, famously defeating home favourites Brazil in the final match.[186] Uruguay has won the Copa América (an international tournament for South American nations and guests) 15 times, such as Argentina, the last one in 2011. Uruguay has by far the smallest population of any country that has won a World Cup.[186] Despite their early success, they missed three World Cups in four attempts from 1994 to 2006.[186] Uruguay reached the semi-final for the first time in 40 years in the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Diego Forlán was presented with the Golden Ball award as the best player of the 2010 tournament.[187]

Uruguay exported 1,414 football players during the 2000s, almost as many players as Brazil and Argentina.[188] In 2010, the Uruguayan government enacted measures intended to retain players in the country.[188] There are two Montevideo-based football clubs, Nacional and Peñarol; they have won three Intercontinental Cups each. When the two clubs play each other, it is known as Uruguayan Clásico.[189] In the rankings for June 2012, Uruguay was ranked the second best team in the world, according to the FIFA world rankings, their highest ever point in football history, falling short of the first spot to the Spain national football team.[190]

Besides football, the most popular sport in Uruguay is basketball.[191] Its national team qualified for the Basketball World Cup seven times, more often than other countries in South America, except Brazil and Argentina. Uruguay hosted the official Basketball World Cup for the 1967 FIBA World Championship and the official Americas Basketball Championship in 1988 and 1997, and is a host of the 2017 FIBA AmeriCup.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Total does not include the 1,199 km2 (463 sq mi) artificial lakes of the Rio Negro.[87]

- ^ Namely, Bell Ville, Buenos Aires, Concepción del Uruguay, Concordia, Entre Ríos, Córdoba, Gualeguaychú, Mendoza, Paraná, Rio Cuarto, Rosario, San Francisco, San Luis, Santa Fe, Tigre, Venado Tuerto, Villa María, and Villa Mercedes.

- ^ Namely Camboriú, Curitiba, Florianópolis, Jaguarão, Joinville, Pelotas, Porto Alegre, Quaraí, São Gabriel, São Paulo, Santa Maria, and Santana do Livramento.(Santana do Livramento has open borders with the Uruguayan city of Rivera. There are no physical barriers or immigration checkpoints inhibiting movement between or within the two contiguous cities, despite each one belonging to separate national jurisdictions.)

- ^ The official racial term on the Uruguayan census is "amarilla" or "yellow" in English, which refers to people of East Asian descent.

References

[edit]- ^ Crow, John A. (1992). The Epic of Latin America (4th ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-520-07723-2.

In the meantime, while the crowd assembled in the plaza continued to shout its demands at the cabildo, the sun suddenly broke through the overhanging clouds and clothed the scene in brilliant light. The people looked upward with one accord and took it as a favorable omen for their cause. This was the origin of the ″sun of May″ which has appeared in the center of the Argentine flag and on the Argentine coat of arms ever since.

- ^ Kopka, Deborah (2011). Central & South America. Dayton, OH: Lorenz Educational Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4291-2251-1.

The sun's features are those of Inti, the Incan sun god. The sun commemorates the appearance of the Sun through cloudy skies on May 25, 1810, during the first mass demonstration in favor of independence.

- ^ IMPO (25 July 2001). Personas con Discapacidad. Lengua de Señas Uruguaya [Disabled Persons. Uruguayan Sign Language – Law No. 17378] (Ley N° 17378) (in Spanish). El Senado y la Cámara Representantes de República Oriental del Uruguay reunidos en Asamblea General. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ a b Meyers, Stephen; Lockwood, Elizabeth (6 December 2014). "The Tale of Two Civil Societies: Comparing disability rights movements in Nicaragua and Uruguay". Disability Studies Quarterly. 34 (4). doi:10.18061/dsq.v34i4.3845. ISSN 2159-8371. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "La población afro-uruguaya en el Censo 2011" (PDF). 2011 (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. p. 16. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH) – Instituto Nacional de Estadística". Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Uruguay". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023. (Archived 2011 edition.)

- ^ a b "Censo Nacional 2023 contabilizó 3.499.451 habitantes en Uruguay". Uruguay Presidencia (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 October 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: April 2024". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 755. ISBN 0-582-05383-8. entry "Uruguay"

- ^ a b "Hace 13.000 años cazadores-recolectores exploraron y colonizaron planicie del río Cuareim" [13,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers explored and colonized the Cuareim River plain]. archivo.presidencia.gub.uy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (1992). "Modern Uruguay, 1875–1903: Militarism 1875–90". In Rex A. Hudson; Sandra W. Meditz (eds.). Uruguay: A Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress Country Studies. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-8444-0737-1. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "URUGUAY A HAVEN FOR REFUGEE SUMS; Gold Flows to 'Switzerland of Americas' Since Korean War – Foreign Trade Booms". The New York Times. 3 January 1951. p. 75. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Back to Democracy in Uruguay". Washington Post. 27 December 2023 [November 30, 1984]. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Uruguay Rankings" (PDF). June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017 – via Embassy of the United States of America.

- ^ "Spartacus Gay Travel Index" (PDF). spartacus.gayguide.travel. 29 February 2024. No. 8, p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Revista Del Río de La Plata. 1971. p. 285. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

The word itself, 'Uruguay', is clearly derived from the Guaraní, probably by way of the tribal dialect of the Charrúas [...] from uru (a generic designation of wild fowl)

- ^ Nordenskiöld, Erland (1979). Deductions suggested by the geographical distribution of some post-Columbian words used by the Indians of S. America. AMS Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-404-15145-4. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

In Paraguay the Guaraní Indians call a fowl uruguaçú. The Cainguá in Misiones only say urú. [...] A few Guaraní-speakiug Indians who call a hen uruguasu and a cock tacareo. Uruguaçu means "the big uru".

- ^ "Presentan tesis del nombre Uruguay". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Presentan tesis del nombre Uruguay". Montevideo, Uruguay. Diario El País. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Uruguay, el país de los pájaros pintados despierta la pasión por mirar". Ministerio de Turismo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (2016). "Uruguay". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Uruguay". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Republic of Uruguay" is the official name used in many United Nations publications in English, e.g. Treaty Series. UN Publications. 1991. ISBN 978-92-1-900187-9. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015. & in some formal UK documents, e.g. Agreement Between the European Community and the Eastern Republic of Uruguay. H.M. Stationery Office. 1974. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Jermyn, Leslie (1 October 1998). Uruguay. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761408734 – via Internet Archive.

uruguay by leslie jermyn.

- ^ López Mazz, José M. (2001). "Las estructuras tumulares (cerritos) del litoral atlantico uruguayo" (PDF). Latin American Antiquity (in Spanish). 12 (3): 231–255. doi:10.2307/971631. ISSN 1045-6635. JSTOR 971631. S2CID 163375789. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Oskar Hermann Khristian Spate (1 November 2004). The Spanish Lake. Canberra: ANU E Press, 2004. p. 37. ISBN 9781920942168. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (1984). The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume 1, Colonial Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780521232234. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. "Background Note: Uruguay". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (December 1993). "The Struggle for Independence 1811–30". In Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W. (eds.). Uruguay: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 92006702. pp. 8–11

- ^ "Google homenajea a Uruguay". El Observador (in Spanish). 25 August 2012. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b c "BEGINNINGS OF INDEPENDENT LIFE, 1830–52 – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (December 1993). "The Great War, 1843–52". In Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W. (eds.). Uruguay: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 92006702. pp. 13–14 Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "THE STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL, 1852–75 – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Uruguay-Railway". www.trade.gov. 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "Caudillos and Political Stability – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Paul H. (1 January 2006). Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America: Dictators, Despots, and Tyrants. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742537392 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "MODERN URUGUAY, 1875–1903 – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Evolution of the Economy and Society – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b "THE NEW COUNTRY, 1903–33 – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (December 1993). "The Conservative Adjustment, 1931–43". In Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W. (eds.). Uruguay: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 92006702. pp. 27–33 Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (December 1993). "Baldomir and the End of Dictatorship". In Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W. (eds.). Uruguay: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 92006702. pp. 31–33 Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kidnapped U.S. Official Found Slain in Uruguay". The New York Times. 11 August 1970. p. 1. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Schrader, Stuart (10 August 2020). "From Police Reform to Police Repression: 50 Years after an Assassination". NACLA. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Dinges, John. "Operation Condor". latinamericanstudies.org. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Marcetic, Branco (30 November 2020). "The CIA's Secret Global War Against the Left". Jacobin. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "New find in Uruguay 'missing' dig". BBC News. 3 December 2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Uruguay dig finds 'disappeared'". BBC News. 30 November 2005. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Altman, David (2010). Direct Democracy Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107427099.

- ^ Jacob, Raúl; Weinstein, Martin (1992). "The military Government 1973–80: The Military's Economic Record". In Rex A. Hudson; Sandra W. Meditz (eds.). Uruguay: A country study (2nd ed.). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-8444-0737-1.

- ^ "Uruguay timeline". BBC News. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Gillespie, Charles G. (1987). "From Authoritarian Crises to Democratic Transitions". Latin American Research Review. 22 (3): 165–184. doi:10.1017/s0023879100037092. ISSN 0023-8791.

- ^ "Uruguay (04/02)". U.S. Department of State. History. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Meyer, Peter J. (4 January 2010). "Uruguay: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (November 2004). "Uruguay's Left Makes History by Winning Presidential Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "The mystery behind Mujica's mask". The Economist. 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Barrionuevo, Alexei (29 November 2009). "Leftist Wins Uruguay Presidential Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Piette, Candace (30 November 2009). "Uruguay elects José Mujica as president, polls show". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Uruguay legalises abortion". BBC News. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage bill comes into force in Uruguay". BBC News. 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Uruguay: The world's marijuana pioneer". BBC News. 3 April 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Tabare Vazquez wins Uruguay's run-off election". BBC News. December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Uruguay's new center-right president sworn in". March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Uruguay in Numbers" (PDF) (in Spanish). National Institute of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Central Intelligence Agency (2016). "Uruguay". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ a b c d e "Climate – Uruguay". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Uruguay". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Quinones, Nelson (16 April 2016). "Tornado kills 4, injures hundreds in Uruguay". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Características climáticas | Inumet". www.inumet.gub.uy. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Climatología estacional | Inumet". www.inumet.gub.uy. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Ola de calor: Florida registró un récord histórico de temperatura". la diaria (in Spanish). 14 January 2022. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ RECORDS METEOROLOGICOS EN EL URUGUAY — Boletín Meteorológico Mensual – Dirección Nacional de Meteorología Archived 9 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. None. Retrieved on 25 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Business Guide" (PDF). Uruguay XXI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Uruguay: The Uruguayan Constitution, archived from the original on 23 September 2017, retrieved 10 May 2017 – via www.wipo.int

- ^ "Uruguay's Constitution of 1966, Reinstated in 1985, with Amendments through 2004" (PDF). constituteproject.org. 28 March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Hudson, Rex A. (December 1993). "Constitutional Background". In Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W. (eds.). Uruguay: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 92006702. pp. 152–159