Duloxetine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cymbalta, Coperin, Cymgen |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604030 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~ 50% (32% to 80%) |

| Protein binding | ~ 95% |

| Metabolism | Liver, two P450 isozymes, CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 |

| Elimination half-life | 12.1 hours |

| Excretion | 70% in urine, 20% in feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.116.825 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

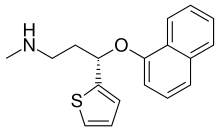

| Formula | C18H19NOS |

| Molar mass | 297.41456 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Duloxetine, sold under the brand name Cymbalta among others, is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) created by Eli Lilly. It is mostly prescribed for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain.[2]

Duloxetine failed to receive US approval for stress urinary incontinence amid concerns over liver toxicity and suicidal events; however, it was approved for this indication in the UK, where it is recommended as an add-on medication in stress urinary incontinence instead of surgery.[3]

Medical uses

The main uses of duloxetine are in major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, urinary incontinence, neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.[2][4][5]

Duloxetine is recommended as a first line agent for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy by the American Society for Clinical Oncology,[6] as a first-line therapy for fibromyalgia in the presence of mood disorders by the German Interdisciplinary Association for Pain therapy,[7] as a Grade B recommendation for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy by the American Association for Neurology[8] and as a level A recommendation in certain neuropathic states by the European Federation of Neurological Societies.[9]

A 2014 Cochrane review concluded that duloxetine is beneficial in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia but that more comparative studies with other medicines are needed.[10] The medical journal Prescrire (based in France) concluded that duloxetine is no better than other available agents and has a greater risk of side effects.[11] Thus they recommend against its general use.[11]

Major depressive disorder

Duloxetine was approved for the treatment of major depression in 2004. While duloxetine has demonstrated improvement in depression-related symptoms compared to placebo, comparisons of duloxetine to other antidepressant medications have been less successful. A 2012 Cochrane Review did not find greater efficacy of duloxetine compared to SSRIs and newer antidepressants. Additionally, the review found evidence that duloxetine has increased side effects and reduced tolerability compared to other antidepressants. It thus did not recommend duloxetine as a first line treatment for major depressive disorder, given the high cost of duloxetine compared to off-patent antidepressants and lack of increased efficacy.[12] Generic duloxetine became available in 2013.[13]

Generalized anxiety disorder

Duloxetine is more effective than placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).[14] Major guidelines such as Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines,[15] and Canadian Psychiatric Association Guidelines[16] do not list duloxetine among the recommended treatment options. However, a review from the Annals of Internal Medicine lists duloxetine among the first line drug treatments, along with citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine.[17]

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Duloxetine was approved for the pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), based on the positive results of two clinical trials. The average daily pain was measured using an 11-point scale, and duloxetine treatment resulted in an additional 1–1.7 points decrease of pain as compared with placebo.[18][19][20] At least 50% pain relief was achieved in 40–45% of the duloxetine patients vs. 20–22% of placebo patients. Pain decreased by more than 90%, in 9–14% of duloxetine patients vs. 2–4% of placebo patients. Most of the response was achieved in the first two weeks on the medication. Duloxetine slightly increased the fasting serum glucose; however this effect was deemed to be of "minimal clinical significance".[18]

The comparative efficacy of duloxetine and established pain-relief medications for DPN is unclear. A systematic review noted that tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine and amitriptyline), traditional anticonvulsants and opioids have better efficacy than duloxetine. Duloxetine, tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants have similar tolerability while the opioids caused more side effects.[21] Another review in Prescrire International considered the moderate pain relief achieved with duloxetine to be clinically insignificant and the results of the clinical trials unconvincing. The reviewer saw no reason to prescribe duloxetine in practice.[22] The comparative data collected by reviewers in BMC Neurology indicated that amitriptyline, other tricyclic antidepressants and venlafaxine may be more effective. However, the authors noted that the evidence in favor of duloxetine is much more solid.[23] A Cochrane review concluded that the evidence in support of duloxetine's efficacy in treating painful diabetic neuropathy was adequate, and that further trials should focus on comparisons with other medications.[10]

Fibromyalgia and chronic pain

A review of duloxetine found that it reduced pain and fatigue, and improved physical and mental performance compared to placebo.[24]

The Food and Drug Administration regulators approved the drug for the treatment of fibromyalgia in June 2008.[25]

It may be useful for chronic pain from osteoarthritis.[26][27]

On November 4, 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved duloxetine to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain, including discomfort from osteoarthritis and chronic lower back pain.[28]

Stress urinary incontinence

Duloxetine was first reported to improve outcomes in stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in 1998.[29] The safety and utility of duloxetine in the treatment of incontinence has been evaluated in a series of meta analyses and practice guidelines.

- A 2013 meta analysis concluded that duloxetine decreased incontinence episodes more than placebo with people about 56% more likely than placebo to experience a 50% decrease in episodes. Adverse effects were experienced by 83% of duloxetine-treated subjects and by 45% of placebo-treated subjects.[30]

- A 2012 review and practice guideline published by the European Association of Urology concluded that the clinical trial data provides Grade 1a evidence that duloxetine improves but does not cure urinary incontinence, and that it causes a high rate of gastrointestinal side effects (mainly nausea and vomiting) leading to a high rate of treatment discontinuation.[31]

- The National Institute for Clinical and Health Excellence recommends (as of September 2013) that duloxetine not be routinely offered as first line treatment, and that it only be offered as second line therapy in women wishing to avoid therapy. The guideline further states that women should be counseled regarding the drug's side effects.[32]

Contraindications

The following contraindications are listed by the manufacturer:[33]

- Hypersensitivity - duloxetine is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to duloxetine or any of the inactive ingredients.

- MAOIs - concomitant use in patients taking MAOIs is contraindicated.

- Uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma - in clinical trials, Cymbalta use was associated with an increased risk of mydriasis (dilation of the pupil); therefore, its use should be avoided in patients with uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, in which mydriasis can cause sudden worsening.

- CNS acting drugs - given the primary central nervous system (CNS) effects of duloxetine, it should be used with caution when it is taken in combination with or substituted for other centrally acting drugs, including those with a similar mechanism of action.

- Duloxetine and thioridazine should not be co-administered.

In addition, the FDA has reported on life-threatening drug interactions that may be possible when co-administered with triptans and other drugs acting on serotonin pathways leading to increased risk for serotonin syndrome.[34]

Adverse effects

Nausea, somnolence, insomnia, and dizziness are the main side effects, reported by about 10% to 20% of patients.[35]

In a trial for major depressive disorder (MDD), the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events among duloxetine-treated patients were nausea (34.7%), dry mouth (22.7%), headache (20.0%) and dizziness (18.7%), and except for headache, these were reported significantly more often than in the placebo group.[36] In a long-term study of fibromyalgia patients receiving duloxetine, frequency and type of adverse effects was similar to that reported in the MDD above. Side effects tended to be mild-to-moderate, and tended to decrease in intensity over time.[37]

Sexual dysfunction is often a side effect of drugs that inhibit serotonin reuptake. Specifically, common side effects include difficulty becoming aroused, lack of interest in sex, and anorgasmia (trouble achieving orgasm). Loss of or decreased response to sexual stimuli and ejaculatory anhedonia are also possible. Frequency of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction in long-term treatment has been found to be similar for duloxetine and SSRIs when compared in clinical trials,[38][39] while there is some evidence that duloxetine is associated with less sexual dysfunction than escitalopram when measured at 4 and 8 weeks of treatment.[39]

Postmarketing spontaneous reports

Reported adverse events which were temporally correlated to duloxetine therapy include rash, reported rarely, and the following adverse events, reported very rarely: alanine aminotransferase increased, alkaline phosphatase increased, anaphylactic reaction, angioneurotic edema, aspartate aminotransferase increased, bilirubin increased, glaucoma, hepatitis, hyponatremia, jaundice, orthostatic hypotension (especially at the initiation of treatment), Stevens–Johnson syndrome, syncope (especially at initiation of treatment), and urticaria.[40]

Discontinuation syndrome

During marketing of other SSRIs and SNRIs, there have been spontaneous reports of adverse events occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, hypomania, tinnitus, and seizures. The withdrawal syndrome from duloxetine resembles the SSRI discontinuation syndrome.

When discontinuing treatment with duloxetine, the manufacturer recommends a gradual reduction in the dose, rather than abrupt cessation, whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate.

In placebo-controlled clinical trials of up to nine weeks' duration of patients with MDD, a systematic evaluation of discontinuation symptoms in patients taking duloxetine following abrupt discontinuation found the following symptoms occurring at a rate greater than or equal to 2% and at a significantly higher rate in duloxetine-treated patients compared to those discontinuing from placebo: dizziness, nausea, headache, paresthesia, vomiting, irritability, and nightmare.[41]

Suicidality

The FDA requires all antidepressants, including duloxetine, to carry a black box warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25. This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of the FDA experts that found a 2-fold increase of the suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group.[42][43][44]

To obtain statistically significant results the FDA had to combine the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications. As suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare, the results for any drug taken separately usually do not reach statistical significance.

In 2005 the United States FDA released a public health advisory noting that there had been 11 reports of suicide attempts and 3 reports of suicidality within the mostly middle-aged women participating in the open label extension trials of duloxetine for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The FDA described the potential role of confounding social stressors "unclear". The suicide attempt rate in the SUI study population (based on 9,400 patients) was calculated to be 400 per 100,000 person years. This rate is greater than the suicide attempt rate among middle-aged U.S. women that has been reported in published studies, i.e., 150 to 160 per 100,000 person years. In addition, one death from suicide was reported in a Cymbalta clinical pharmacology study in a healthy female volunteer without SUI. No increase in suicidality was reported in controlled trials of Cymbalta for depression or diabetic neuropathic pain.[45]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Duloxetine inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) in the central nervous system. Duloxetine increases dopamine (DA) specifically in the prefrontal cortex, where there are few DA reuptake pumps, via the inhibition of NE reuptake pumps (NET) which is believed to mediate reuptake of DA and NE.[46] However, duloxetine has no significant affinity for dopaminergic, cholinergic, histaminergic, opioid, glutamate, and GABA reuptake transporters and can therefore be considered to be a selective reuptake inhibitor at the 5-HT and NE transporters. Duloxetine undergoes extensive metabolism, but the major circulating metabolites do not contribute significantly to the pharmacologic activity.[47][48]

Major depressive disorder is believed to be due in part to an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines within the central nervous system. Antidepressants including ones with a similar mechanism of action as duloxetine, i.e. serotonin metabolism inhibition, cause a decrease in proinflammatory cytokine activity and an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines; this mechanism may apply to duloxetine in its effect on depression but research on cytokines specific to duloxetine therapy is lacking.[49]

The analgesic properties of duloxetine in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and central pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia are believed to be due to sodium ion channel blockade.[50]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption: Duloxetine is acid labile, and is formulated with enteric coating to prevent degradation in the stomach. Duloxetine has good oral bioavailability, averaging 50% after one 60 mg dose. There is an average 2-hour lag until absorption begins with maximum plasma concentrations occurring about 6 hours post dose. Food does not affect the Cmax of duloxetine, but delays the time to reach peak concentration from 6 to 10 hours.[48]

Distribution: Duloxetine is highly bound (>90%) to proteins in human plasma, binding primarily to albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein. Volume of distribution is 1640L.[51]

Metabolism: Duloxetine undergoes predominately hepatic metabolism via two cytochrome P450 isozymes, CYP2D6 and CYP1A2. Circulating metabolites are pharmacologically inactive.[51]

Elimination: Duloxetine has an elimination half-life of about 12 hours (range 8 to 17 hours) and its pharmacokinetics are dose proportional over the therapeutic range. Steady-state is usually achieved after 3 days. Only trace amounts (<1%) of unchanged duloxetine are present in the urine and most of the dose (approx. 70%) appears in the urine as metabolites of duloxetine with about 20% excreted in the feces.[51]

History

Duloxetine was created by Lilly researchers. David Robertson; David Wong, a co-discoverer of fluoxetine; and Joseph Krushinski are listed as inventors on the patent application filed in 1986 and granted in 1990.[52] The first publication on the discovery of the racemic form of duloxetine known as LY227942, was made in 1988.[53] The (+)-enantiomer of LY227942, assigned LY248686, was chosen for further studies, because it inhibited serotonin reuptake in rat synaptosomes to twice the degree of the (–)-enantiomer. This molecule was subsequently named duloxetine.[54]

In 2001, Lilly filed a New Drug Application (NDA) for duloxetine with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, in 2003, the FDA "recommended this application as not approvable from the manufacturing and control standpoint" because of "significant cGMP (current Good Manufacturing Practice) violations at the finished product manufacturing facility" of Eli Lilly in Indianapolis. Additionally, "potential liver toxicity" and QTc interval prolongation appeared as a concern. The FDA experts concluded that "duloxetine can cause hepatotoxicity in the form of transaminase elevations. It may also be a factor in causing more severe liver injury, but there are no cases in the NDA database that clearly demonstrate this. Use of duloxetine in the presence of ethanol may potentiate the deleterious effect of ethanol on the liver." The FDA also recommended "routine blood pressure monitoring" at the new highest recommended dose of 120 mg, "where 24% patients had one or more blood pressure readings of 140/90 vs. 9% of placebo patients."[55]

After the manufacturing issues were resolved, the liver toxicity warning included in the prescribing information, and the follow-up studies showed that duloxetine does not cause QTc interval prolongation, duloxetine was approved by the FDA for depression and diabetic neuropathy in 2004.[56] In 2007, Health Canada approved duloxetine for the treatment of depression and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain.[57]

Duloxetine was approved for use of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the EU in 2004. In 2005, Lilly withdrew the duloxetine application for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the U.S., stating that discussions with the FDA indicated "the agency is not prepared at this time to grant approval ... based on the data package submitted." A year later Lilly abandoned the pursuit of this indication in the U.S. market.[58][59]

The FDA approved duloxetine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in February 2007.[60]

Cymbalta generated sales of nearly $5 billion in 2012 with $4 billion of that in the U.S., but its patent protection terminated January 1, 2014. Lilly received a six-month extension beyond June 30, 2013 after testing for the treatment of depression in adolescents, which may produce $1.5 billion in added sales.[61][62]

The first generic duloxetine was marketed by Dr. Reddy.[63]

Brand names

Brand names include: Ariclaim, Dimorex, Xeristar, Yentreve, Duzela, Dulane, Cymbalta, Coperin (in Australia, manufactured by Alphapharm), Abretia (México) and Cymgen (in South Africa).

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b "Duloxetine". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 40: Urinary incontinence. London, 2006.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 96: Neuropathic pain - pharmacological management. London, 2010.

- ^ Bril V, England J, Franklin GM (2011). "Evidence-based guideline: Treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy". Neurology. Online (20): 1758–65. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe. PMC 3100130. PMID 21482920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH (June 2014). "Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline". J. Clin. Oncol. 32 (18): 1941–67. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. PMID 24733808.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sommer C, Häuser W, Alten R (June 2012). "[Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline]". Schmerz (in German). 26 (3): 297–310. doi:10.1007/s00482-012-1172-2. PMID 22760463.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bril V, England JD, Franklin GM (June 2011). "Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy--report of the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation". Muscle Nerve. 43 (6): 910–7. doi:10.1002/mus.22092. PMID 21484835.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R (September 2010). "EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision". Eur. J. Neurol. 17 (9): 1113–e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. PMID 20402746.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ (2014). "Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD007115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3. PMID 24385423.

- ^ a b "Towards better patient care: drugs to avoid in 2014". Prescrire International. 23 (150): 161–165. June 2014. PMID 25121155.

- ^ Cipriani, A; Koesters, M; Furukawa, TA; Nosè, M; Purgato, M; Omori, IM; Trespidi, C; Barbui, C (Oct 17, 2012). "Duloxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 10: CD006533. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006533.pub2. PMC 4169791. PMID 23076926.

- ^ Swiatek, Jeff (2013-10-13). "Loss of Cymbalta patent a major blow for Eli Lilly". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ^ Carter, NJ; McCormack, PL (2009). "Duloxetine: a review of its use in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Drugs. 23 (6): 523–41. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923060-00006. PMID 19480470.

- ^ Kerwin, Robert; Taylor, David H.; Carol Paton (2007). Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines. Informa Healthcare. p. 254. ISBN 0-415-42416-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canadian Psychiatric, Association (July 2006). "Clinical practice guidelines. Management of anxiety disorders". Can J Psychiatry. 51 (8 Suppl 2): 52S–55S. PMID 16933543.

- ^ Patel, G; Fancher, TL (Dec 3, 2013). "In the clinic. Generalized anxiety disorder". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): ITC6–1, ITC6–2, ITC6–3, ITC6–4, ITC6–5, ITC6–6, ITC6–7, ITC6–8, ITC6–9, ITC6–10, ITC6–11, quiz ITC6–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-01006. PMID 24297210.

- ^ a b Josefberg H (2004-09-03). "Application number 21-733. Medical review(s)" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 2009-04-14. [dead link]

- ^ Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Lee TC, Iyengar S; Lu; Detke; Lee; Iyengar (July 2005). "Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy". Pain. 116 (1–2): 109–18. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.029. PMID 15927394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F (2005). "A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain". Pain Med. 6 (5): 346–56. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00061.x. PMID 16266355.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wong MC, Chung JW, Wong TK; Chung; Wong (July 2007). "Effects of treatments for symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: systematic review". BMJ. 335 (7610): 87. doi:10.1136/bmj.39213.565972.AE. PMC 1914460. PMID 17562735.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Duloxetine: new indication. Depression and diabetic neuropathy: too many adverse effects". Prescrire Int. 15 (85): 168–72. October 2006. PMID 17121211.

- ^ Sultan A, Gaskell H, Derry S, Moore RA; Gaskell; Derry; Moore (2008). "Duloxetine for painful diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia pain: systematic review of randomised trials". BMC Neurol. 8: 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-8-29. PMC 2529342. PMID 18673529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Acuna C (October 2008). "Duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Drugs Today. 44 (10): 725–34. doi:10.1358/dot.2008.44.10.1269675. PMID 19137126.

- ^ "FDA Approves Cymbalta for the Management of Fibromyalgia". Eli Lilly Co. 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ Citrome, L; Weiss-Citrome, A (Jan 2012). "A systematic review of duloxetine for osteoarthritic pain: what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed?". Postgraduate Medicine. 124 (1): 83–93. doi:10.3810/pgm.2012.01.2521. PMID 22314118.

- ^ Myers, J; Wielage, R. C.; Han, B; Price, K; Gahn, J; Paget, M. A.; Happich, M (2014). "The efficacy of duloxetine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids in osteoarthritis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 15: 76. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-76. PMC 4007556. PMID 24618328.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "FDA clears Cymbalta to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain". FDA Press Announcements. Food and Drug Administration. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Voelker R (September 1998). "International group seeks to dispel incontinence "taboo"". JAMA. 280 (11): 951–3. doi:10.1001/jama.280.11.951. PMID 9749464.

- ^ Li J, Yang L, Pu C, Tang Y, Yun H, Han P; Yang; Pu; Tang; Yun; Han (June 2013). "The role of duloxetine in stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int Urol Nephrol. 45 (3): 679–86. doi:10.1007/s11255-013-0410-6. PMID 23504618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.uroweb.org" (PDF).

- ^ "Urinary incontinence Introduction CG171".

- ^ http://www.cymbalta.com/learnaboutcymbalta/importantsafetyinformation.jsp?type=print>

- ^ Report a Serious Problem (2013-08-14). "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Duloxetine (marketed as Cymbalta) - Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or Selective Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) and 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor Agonists (Triptans)". Fda.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ Cymbalta package insert. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals; 2004, September.

- ^ Perahia DG, Kajdasz DK, Walker DJ, Raskin J, Tylee A; Kajdasz; Walker; Raskin; Tylee (May 2006). "Duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of milder major depressive disorder". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 60 (5): 613–20. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00956.x. PMC 1473178. PMID 16700869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chappell; Littlejohn, Kajdasz, Scheinberg, D'Souza, Moldofsky (Jun 2009). "A 1-year safety and efficacy study of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia". Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 365–375. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31819be587. PMID 19454869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Duenas, H; Brnabic, Lee, Montejo, Prakash, Casimiro-Querubin, Khaled, Dossenbach, Raskin (Nov 2011). "Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction with SSRIs and duloxetine: efferctiveness and functional outcomes over a 6-month observational period". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 15 (4): 242–254. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.590209. PMID 22121997.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Clayton, A; Kornstein, Prakash, Mallinckrodt, Wohlreich (July 2007). "Changes in sexual functioning associated with duloxetine, escitalopram, and placebo in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 4 (4 Pt 1): 917–929. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00520.x. PMID 17627739.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1] Duloxetine Side Effects, and Drug Interactions - RxList Monographs

- ^ Perahia DG, Kajdasz DK, Desaiah D, Haddad PM; Kajdasz; Desaiah; Haddad (December 2005). "Symptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder". J Affect Disord. 89 (1–3): 207–12. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.003. PMID 16266753.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidality in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (2006-11-17). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ "Historical Information on Duloxetine hydrochloride (marketed as Cymbalta)".

- ^ Stahl, S. (2013). Stahl's essential pharmacology, 4th ed. Cambridge University Press, New York. p. 305, 308, 309.

- ^ Stahl, SM; Grady, Moret, Briley (Sep 2005). "SNRIs: their pharmacology, clinical efficacy, and tolerability in comparison with other classes of antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 10 (9): 732–747. PMID 16142213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bymaster, FP; Lee, Knadler (2005). "The dual transporter inhibitor duloxetine: a review of its preclinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetic profile, and clinical results in depression". Curr Pharm Des. 11 (12): 1475–93. doi:10.2174/1381612053764805. PMID 15892657.

- ^ De Berardis D, Conti CM, Serroni N, Moschetta FS, Olivieri L, Carano A, Salerno RM, Cavuto M, Farina B, Alessandrini M, Janiri L, Pozzi G, Di Giannantonio M; Conti; Serroni; Moschetta; Olivieri; Carano; Salerno; Cavuto; Farina; Alessandrini; Janiri; Pozzi; Di Giannantonio (2010). "The effect of newer serotonin-noradrenalin antidepressants on cytokine production: a review of the current literature". Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 23 (2): 417–22. PMID 20646337.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang SY, Calderon J, Kuo Wang G; Calderon; Kuo Wang (September 2010). "Block of neuronal Na+ channels by antidepressant duloxetine in a state-dependent manner". Anesthesiology. 113 (3): 655–65. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e89a93. PMID 20693878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Cymbalta product insert" (PDF).

- ^ Robertson DW, Wong DT, Krushinski JH (1990-09-11). "United States Patent 4,956,388: 3-Aryloxy-3-substituted propanamines". USPTO. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wong DT, Robertson DW, Bymaster FP, Krushinski JH, Reid LR; Robertson; Bymaster; Krushinski; Reid (1988). "LY227942, an inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine uptake: biochemical pharmacology of a potential antidepressant drug". Life Sci. 43 (24): 2049–57. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(88)90579-6. PMID 2850421.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bymaster FP, Beedle EE, Findlay J (December 2003). "Duloxetine (Cymbalta), a dual inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13 (24): 4477–80. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.079. PMID 14643350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Approval package for: application number NDA 721-427. Administrative/Correspondence #2" (PDF). The FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2011. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ FDA news

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD): Cymbalta". Health Canada. 2008-05-05.

- ^ Steyer R (2006-02-15). "Lilly Won't Pursue Yentreve for U.S." TheStreet.com. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ Lenzer J (2005). "FDA warns that antidepressants may increase suicidality in adults". BMJ. 331 (7508): 70. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7508.70-b. PMC 558648. PMID 16002878.

- ^ "FDA approves antidepressant Cymbalta (duloxetine HCl) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". News-Medical.Net. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Staton, Tracy (July 9, 2012). "Lilly could net $1.5B-plus from Cymbalta extension". FiercePharma. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Palmer, Eric (April 11, 2013). "Eli Lilly to lay off hundreds in sales as Cymbalta nears edge of patent cliff". FiercePharma. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Anson, Pat (December 12, 2013). "Generic Cheaper Versions of Cymbalta Approved". National Pain Report. Retrieved January 2, 2014.