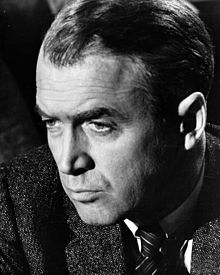

James Stewart

James Stewart | |

|---|---|

Stewart in 1948 | |

| Born | May 20, 1908 Indiana, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | July 2, 1997 (aged 89) |

| Cause of death | Pulmonary embolism[1] |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn, Glendale, California |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1932–1991 |

| Known for | First American movie star to enlist in World War II[2][N 1] |

| Notable work | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Philadelphia Story, It's a Wonderful Life, Rear Window, Vertigo |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 (including two stepchildren) |

| Awards | Academy Lifetime Achievement (1985) Academy Award for Best Actor (1941) Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award (1965) Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Television Series Drama (1974) |

James Maitland Stewart (May 20, 1908 – July 2, 1997), also known as Jimmy Stewart (although he seldom used that name in formal credits), was an American actor and military officer, known for his distinctive drawl and down-to-earth persona. A major Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract player, Stewart starred in many films that are considered to be classics, and is known for portraying American middle-class men struggling in crisis.

Stewart was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning one in competition for The Philadelphia Story (1940) and receiving an Academy Lifetime Achievement award in 1985. He also had a noted military career and was a World War II and Vietnam War veteran, who rose to the rank of Brigadier General in the United States Air Force Reserve, becoming the highest-ranking actor in military history.[3]

In 1999, Stewart was named the third greatest male screen legend of the Golden Age of Hollywood by the American Film Institute.[4]

Early life and career

Stewart was born on May 20, 1908, in Indiana, Pennsylvania, the son of Elizabeth Ruth Jackson (1875–1953) and Alexander Maitland Stewart (1871–1961), who owned a hardware store.[5][6] Stewart was mainly of Scottish ancestry and was raised as a Presbyterian.[7][8][9] He was descended from veterans of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the American Civil War.[9] The eldest of three children (he had two younger sisters, Virginia and Mary), he was expected to continue his father's business, which had been in the family for three generations. His mother was an excellent pianist but his father discouraged Stewart's request for lessons. When his father accepted a gift of an accordion from a guest, young Stewart quickly learned to play the instrument, which became a fixture offstage during his acting career. As the family grew, music continued to be an important part of family life.[10]

Stewart attended Mercersburg Academy prep school, graduating in 1928. He was active in a variety of activities. He played on the football and track teams, was art editor of the KARUX yearbook, and a member of the choir club, glee club, and John Marshall Literary Society. During his first summer break, Stewart returned to his hometown to work as a brick loader for a local construction company and on highway and road construction jobs where he painted lines on the roads. Over the following two summers, he took a job as an assistant with a professional magician.[11] He made his first appearance onstage at Mercersburg, as Buquet in the play The Wolves.[12]

A shy child, Stewart spent much of his after-school time in the basement working on model airplanes, mechanical drawing and chemistry—all with a dream of going into aviation. It was a dream greatly enhanced by the legendary 1927 flight of Charles Lindbergh, whose progress 19-year-old Stewart, then stricken with scarlet fever, was himself avidly following from home; thus foreshadowing his starring movie role as Lindbergh 30 years later.[13]

However, he abandoned visions of being a pilot when his father insisted that instead of the United States Naval Academy he attend Princeton University. Stewart enrolled at Princeton in 1928 as a member of the class of 1932. He excelled at studying architecture, so impressing his professors with his thesis on an airport design that he was awarded a scholarship for graduate studies;[11] but he gradually became attracted to the school's drama and music clubs, including the Princeton Triangle Club.[14] His acting and accordion talents at Princeton led him to be invited to the University Players, an intercollegiate summer stock company in West Falmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. The company had been organized in 1928 and would run until 1932, with Joshua Logan, Bretaigne Windust and Charles Leatherbee as directors. Stewart performed in bit parts in the Players' productions in Cape Cod during the summer of 1932, after he graduated.

The troupe had previously included Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullavan. Stewart and Fonda became great friends over the summer of 1932 when they shared an apartment with Joshua Logan and Myron McCormick.[15] When Stewart came to New York at the end of the summer stock season, which had included the Broadway tryout of Goodbye Again, he shared an apartment with Fonda, who had by then finalized his divorce from Sullavan. Along with fellow University Players Alfred Dalrymple and Myron McCormick, Stewart debuted on Broadway in the brief run of Carry Nation and a few weeks later – again with McCormick and Dalrymple – as a chauffeur in the comedy Goodbye Again, in which he had two lines. The New Yorker noted, "Mr. James Stewart's chauffeur... comes on for three minutes and walks off to a round of spontaneous applause."[16]

The play was a moderate success, but times were hard. Many Broadway theaters had been converted to movie houses and the Depression was reaching bottom. "From 1932 through 1934", Stewart later recalled, "I'd only worked three months. Every play I got into folded."[17] By 1934, he was given more substantial stage roles, including the modest hit Page Miss Glory and his first dramatic stage role in Sidney Howard's Yellow Jack, which convinced him to continue his acting career. However, Stewart and Fonda, still roommates, were both struggling. In the fall of 1934, Fonda's success in The Farmer Takes a Wife took him to Hollywood. Finally, Stewart attracted the interest of MGM scout Bill Grady who saw Stewart on the opening night of Divided by Three, a glittering première with many luminaries in attendance, including Irving Berlin, Moss Hart and Fonda, who had returned to New York for the show. With Fonda's encouragement, Stewart agreed to take a screen test, after which he signed a contract with MGM in April 1935, as a contract player for up to seven years at $350 a week.[18]

Upon Stewart's arrival by train in Los Angeles, Fonda greeted him at the station and took him to Fonda's studio-supplied lodging, next door to Greta Garbo. Stewart's first job at the studio was as a participant in screen tests with newly arrived starlets. At first, he had trouble being cast in Hollywood films owing to his gangling looks and shy, humble screen presence. Aside from an unbilled appearance in a Shemp Howard comedy short called Art Trouble in 1934, his first film was the poorly received Spencer Tracy vehicle, The Murder Man (1935). Rose Marie (1936), an adaptation of a popular operetta, was more successful. After having mixed success in films, he received his first intensely dramatic role in 1936's After the Thin Man, and played Jean Harlow's character's frustrated boyfriend in the Clark Gable vehicle Wife vs. Secretary earlier that same year.

On the romantic front, he dated newly divorced Ginger Rogers.[19] The romance soon cooled, however, and by chance Stewart encountered Margaret Sullavan again. Stewart found his footing in Hollywood thanks largely to Sullavan, who campaigned for Stewart to be her leading man in the 1936 romantic comedy Next Time We Love. She rehearsed extensively with him, having a noticeable effect on his confidence. She encouraged Stewart to feel comfortable with his unique mannerisms and boyish charm and use them naturally as his own style. Stewart was enjoying Hollywood life and had no regrets about giving up the stage, as he worked six days a week in the MGM factory.[20] In 1936, he acquired big-time agent Leland Hayward, who would eventually marry Sullavan. Hayward started to chart Stewart's career, deciding that the best path for him was through loan-outs to other studios.

Pre-war success

In 1938 Stewart had a brief, tumultuous romance with Hollywood queen Norma Shearer, whose husband, Irving Thalberg, head of production at MGM, had died two years earlier. Stewart began a successful partnership with director Frank Capra in 1938, when he was loaned out to Columbia Pictures to star in You Can't Take It With You. Capra had been impressed by Stewart's minor role in Navy Blue and Gold (1937). The director had recently completed several popular movies, including It Happened One Night (1934), and was looking for the right actor to suit his needs—other recent actors in Capra's films such as Clark Gable, Ronald Colman, and Gary Cooper did not quite fit. Not only was Stewart just what he was looking for, but Capra also found Stewart understood that prototype intuitively and required very little directing. Later Capra commented, "I think he's probably the best actor who's ever hit the screen."[21]

You Can't Take It With You, starring Capra's "favorite actress", comedian Jean Arthur, won the 1938 Best Picture Academy Award. The following year saw Stewart work with Capra and Arthur again in the political comedy-drama Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Stewart replaced intended star Gary Cooper in the film, playing an idealist thrown into the political arena. Upon its October 1939 release, the film garnered critical praise and became a box-office success. Stewart received the first of five Academy Award nominations for Best Actor. Stewart's father was still trying to talk him into leaving Hollywood and its sinful ways and to return to his home town to lead a decent life. Stewart took a secret trip to Europe to take a break and returned home in 1939 just as Germany invaded Poland.[21]

You hear so much about the old movie moguls and the impersonal factories where there is no freedom. MGM was a wonderful place where decisions were made on my behalf by my superiors. What's wrong with that?

James Stewart, The Leading Men of MGM[22]

Destry Rides Again, also released in 1939, became Stewart's first western film, a genre with which he would become identified later in his career. In this western parody, he is a pacifist lawman and Marlene Dietrich is the dancing saloon girl who comes to love him, but does not get him. Off-screen, Dietrich did get her man, but the romance was short-lived.[23] Made for Each Other (1939) had Stewart sharing the screen with Carole Lombard in a melodrama that garnered good reviews for both stars, but did less well with the public. Newsweek wrote that they were "perfectly cast in the leading roles".[24] Between movies, Stewart began a radio career and became a distinctive voice on the Lux Radio Theater's The Screen Guild Theater and other shows. So well-known had his slow drawl become that comedians began impersonating him.[25]

In 1940 Stewart and Sullavan reunited for two films. The first, the Ernst Lubitsch romantic comedy, The Shop Around the Corner, starred them as co-workers unknowingly involved in a pen-pal romance but who cannot stand each other in real life. It was Stewart's fifth film of the year and one of the rare ones shot in sequence; it was completed in only 27 days.[26] The Mortal Storm, directed by Frank Borzage, was one of the first blatantly anti-Nazi films to be produced in Hollywood and featured Sullavan and Stewart as friends and then lovers caught in turmoil upon Hitler's rise to power, literally hunted down by their own friends.

Stewart also starred with Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in George Cukor's classic The Philadelphia Story (1940). His performance as an intrusive, fast-talking reporter earned him his only Academy Award in a competitive category (Best Actor, 1941); he beat out his good friend Henry Fonda (The Grapes of Wrath). Stewart thought his performance "entertaining and slick and smooth" but lacking the "guts" of "Mr. Smith".[27] Stewart gave the Oscar statuette to his father, who displayed it for many years in a case inside the front door of his hardware store, alongside other family awards and military medals.

During the months before he began military service, Stewart appeared in a series of screwball comedies with varying levels of success. He followed the mediocre No Time for Comedy (1940) with Rosalind Russell and Come Live with Me (1941) with Hedy Lamarr with the Judy Garland musical Ziegfeld Girl and the George Marshall romantic comedy Pot o' Gold, featuring Paulette Goddard. Stewart was drafted in late 1940, a situation that coincided with the lapse in his MGM contract, marking a turning point in Stewart's career, with 28 movies to his credit at that point.[28]

Military service

James Stewart | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | Jimmy |

| Place of burial | Glendale, California |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1941–1968 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Battles / wars | World War II • European Theater of Operations |

Stewart's family on both sides had deep military roots, as both grandfathers had fought in the Civil War,[citation needed] and his father had served during both the Spanish–American War and World War I. Stewart considered his father to be the biggest influence on his life, so it was not surprising that, when another war came, he too was eager to serve. Members of his family had previously been in the infantry, but Stewart chose to become a flier.[29]

An early interest in flying led Stewart to gain his Private Pilot certificate in 1935 and Commercial Pilot certificate in 1938. He often flew cross-country to visit his parents in Pennsylvania, navigating by the railroad tracks.[11] Nearly two years before the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, Stewart had accumulated over 400 hours of flying time.[30]

Considered a highly proficient pilot, he entered a cross-country race as a co-pilot in 1939.[31] Stewart, along with musician/composer Hoagy Carmichael, saw the need for trained war pilots, and joined with other Hollywood celebrities to invest in Thunderbird Field, a pilot-training school built and operated by Southwest Airways in Glendale, Arizona. This airfield became part of the United States Army Air Forces training establishment and trained more than 10,000 pilots during World War II.[32]

In October 1940, Stewart was drafted into the United States Army but was rejected for failing to meet the weight requirements for his height for new recruits—Stewart was five pounds (2.3 kg) under the standard. To get up to 143 pounds, he sought out the help of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's muscle man and trainer Don Loomis, who was noted for his ability to help people add or subtract pounds in his studio gymnasium. Stewart subsequently attempted to enlist in the Air Corps, but still came in underweight, although he persuaded the enlistment officer to run new tests, this time passing the weigh-in,[33][N 2] with the result that Stewart enlisted and was inducted in the Army on March 22, 1941. He became the first major American movie star to wear a military uniform in World War II.[2]

Stewart enlisted as a private[11][34] but applied for an Air Corps commission and pilot rating as both a college graduate and a licensed commercial pilot. Soon to be 33, he was almost six years beyond the maximum age restriction for aviation cadet training, the normal path of commissioning for pilots. Stewart received his commission as a second lieutenant on January 19, 1942, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, while a corporal at Moffett Field, California. He also received a pilot rating, although the circumstances are unclear, since he did not participate in the standard pilot training program.[N 3] Stewart's first assignment was an appearance at a March of Dimes rally in Washington, D.C., but Stewart wanted assignment to an operational unit rather than serving as a recruiting symbol. He applied for and was granted advanced training in multi-engine aircraft. Stewart was posted to nearby Mather Field to instruct in both single- and twin-engine aircraft.[34][35]

Public appearances by Stewart were limited engagements scheduled by the Army Air Forces. "Stewart appeared several times on network radio with Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he performed with Orson Welles, Edward G. Robinson, Walter Huston and Lionel Barrymore in an all-network radio program called We Hold These Truths, dedicated to the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights."[36] In early 1942, Stewart was asked to appear in a film to help recruit the 100,000 airmen the USAAF anticipated it would need to win the war. The USAAF's First Motion Picture Unit shot scenes of Lieutenant Stewart in his pilot's flight jacket and recorded his voice for narration. The short propaganda film Winning Your Wings appeared nationwide beginning in late May and was very successful, resulting in 150,000 new recruits.[37][38]

Stewart was concerned that his expertise and celebrity status would relegate him to instructor duties "behind the lines".[39] His fears were confirmed when, after his promotion to first lieutenant on July 7, 1942,[40] he was stationed from August to December 1942 at Kirtland Army Airfield in Albuquerque, New Mexico, piloting AT-11 Kansans used in training bombardiers. He was transferred to Hobbs Army Airfield, New Mexico, for three months of transition training in the four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress, then sent to the Combat Crew Processing Center in Salt Lake City, where he expected to be assigned to a combat unit. Instead, he was assigned in early 1943 to an operational training unit, the 29th Bombardment Group at Gowen Field, Boise, Idaho, as an instructor.[34] He was promoted to captain on July 9, 1943,[40] and appointed a squadron commander.[35] To Stewart, now 35, combat duty seemed far away and unreachable, and he had no clear plans for the future. However, a rumor that Stewart would be taken off flying status and assigned to making training films or selling bonds called for immediate action, because what he dreaded most was "the hope-shattering spectre of a dead end".[41] Stewart appealed to his commander, 30-year-old Lt. Col. Walter E. Arnold Jr., who understood his situation and recommended Stewart to the commander of the 445th Bombardment Group, a B-24 Liberator unit that had just completed initial training at Gowen Field and gone on to final training at Sioux City Army Air Base, Iowa.[42][N 4]

In August 1943, Stewart was assigned to the 445th Bomb Group as operations officer of the 703d Bombardment Squadron, but after three weeks became its commander. On October 12, 1943, judged ready to go overseas, the 445th Bomb Group staged to Lincoln Army Airfield, Nebraska. Flying individually, the aircraft first flew to Morrison Army Airfield, Florida, and then on the circuitous Southern Route along the coasts of South America and Africa to RAF Tibenham, Norfolk, England. After several weeks of training missions, in which Stewart flew with most of his combat crews, the group flew its first combat mission on December 13, 1943, to bomb the U-boat facilities at Kiel, Germany, followed three days later by a mission to Bremen. Stewart led the high squadron of the group formation on the first mission, and the entire group on the second.[44] Following a mission to Ludwigshafen, Germany, on January 7, 1944, Stewart was promoted to major.[44][N 5] Stewart was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for actions as deputy commander of the 2nd Combat Bombardment Wing on the first day of "Big Week" operations in February and flew two other missions that week.[46]

On March 22, 1944, Stewart flew his 12th combat mission, leading the 2nd Bomb Wing in an attack on Berlin. On March 30, 1944, he was sent to RAF Old Buckenham to become group operations officer of the 453rd Bombardment Group, a new B-24 unit that had just lost both its commander and operations officer on missions.[47] To inspire the unit, Stewart flew as command pilot in the lead B-24 on several missions deep into Nazi-occupied Europe. As a staff officer, Stewart was assigned to the 453rd "for the duration" and thus not subject to a quota of missions of a combat tour. He nevertheless assigned himself as a combat crewman on the group's missions until his promotion to lieutenant colonel on June 3[40] and reassignment on July 1, 1944, to the 2nd Bomb Wing, assigned as executive officer to Brigadier General Edward J. Timberlake. His official tally of mission credits while assigned to the 445th and 453rd Bomb Groups was 20 sorties.

Stewart continued to go on missions uncredited, flying with the pathfinder squadron of the 389th Bombardment Group, with his two former groups and with groups of the 20th Combat Bomb Wing.[48] He received a second award of the Distinguished Flying Cross for actions in combat and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. He also received the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters. Stewart served in a number of staff positions in the 2nd and 20th Bomb Wings between July 1944 and the end of the war in Europe, and was promoted to full colonel on March 29, 1945.[40][49] On May 10, 1945, he succeeded to command of the 2nd Bomb Wing, a position he held until June 15.[50] Stewart was one of the few Americans to rise from private to colonel in four years.[11][34]

At the beginning of June 1945, Stewart was the presiding officer of the court-martial of a pilot and navigator who were charged with dereliction of duty for having accidentally bombed the Swiss city of Zurich the previous March—the first instance of U.S. personnel being tried for an attack on a neutral country. The court acquitted the defendants.[51]

Stewart continued to play a role in the Army Air Forces Reserve following World War II and the new United States Air Force Reserve after the establishment of the Air Force as an independent service in 1947. Stewart received permanent promotion to colonel in 1953 and served as Air Force Reserve commander of Dobbins Air Force Base, Georgia, the present day Dobbins Air Reserve Base.[40][52] He was also one of the 12 founders and a charter member of the Air Force Association in October 1945. Stewart rarely spoke about his wartime service, but did appear in January 1974 in an episode of the TV series The World At War, "Whirlwind: Bombing Germany (September 1939 – April 1944)", commenting on the disastrous mission of October 14, 1943, against Schweinfurt, Germany. At his request, he was identified only as "James Stewart, Squadron Commander" in the documentary.[53]

On July 23, 1959, Stewart was promoted to brigadier general. During his active duty periods, he remained current as a pilot of Convair B-36 Peacemaker, Boeing B-47 Stratojet and Boeing B-52 Stratofortress intercontinental bombers of the Strategic Air Command.[54] On February 20, 1966, Brigadier General Stewart flew as a non-duty observer in a B-52 on an Arc Light bombing mission during the Vietnam War. He refused the release of any publicity regarding his participation, as he did not want it treated as a stunt, but as part of his job as an officer in the Air Force Reserve. After 27 years of service, Stewart retired from the Air Force on May 31, 1968.[55]

Stewart received a number of awards during his military service.

Postwar career

After the war, Stewart took time off to reassess his career.[56] He was an early investor in Southwest Airways, founded by Leland Hayward, and considered going into the aviation industry if his restarted film career did not prosper.[57] Upon Stewart's return to Hollywood in fall 1945, he decided not to renew his MGM contract. He signed with the MCA talent agency. His former agent Leland Hayward got out of the talent business in 1944 after selling his A-list of stars, including Stewart, to MCA.[58]

For his first film in five years, Stewart appeared in his third and final Frank Capra production, It's a Wonderful Life.[59][N 6] Capra paid RKO for the rights to the story and formed his own production company, Liberty Films. The female lead went to Donna Reed when Capra's perennial first choice, Jean Arthur, was unavailable, and after Ginger Rogers, Olivia de Havilland, Ann Dvorak, and Martha Scott had all turned down the role.[60] Stewart appeared as George Bailey, an upstanding small-town man who becomes increasingly frustrated by his ordinary existence and financial troubles. Driven to suicide on Christmas Eve, he is led to reassess his life by Clarence Odbody,[61] an "angel, second class" played by Henry Travers.

Although It's a Wonderful Life was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Stewart's third Best Actor nomination, it received mixed reviews and only disappointingly moderate success at the box office.[62] However, in the decades since the film's release, it grew to define Stewart's film persona and is widely considered as a sentimental Christmas film classic and, according to the American Film Institute, one of the 100 best movies ever made. In an interview with Michael Parkinson in 1973, Stewart declared that out of all the movies he had made, It's a Wonderful Life was his favorite. After viewing the film, President Harry S. Truman concluded, "If Bess and I had a son we'd want him to be just like Jimmy Stewart."[63] In the aftermath of the film, Capra's production company went into bankruptcy, while Stewart started to have doubts about his ability to act after his military hiatus.[64] His father kept insisting he come home and marry a local girl. Meanwhile, in Hollywood, his generation of actors were fading and a new wave of actors would soon remake the town, including Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and James Dean.[65]

Magic Town (1947), a comedy film directed by William A. Wellman, starring James Stewart and Jane Wyman, was one of the first films about the then-new science of public opinion polling. It was poorly received. He completed Rope (1948) directed by Alfred Hitchcock and Call Northside 777 (1948), and weathered two box-office disappointments with On Our Merry Way (1948), a comedic musical ensemble in which Stewart and Henry Fonda were paired as two jazz musicians, and You Gotta Stay Happy (1949), for which the posters depicted Stewart being kissed on one cheek by Joan Fontaine and on the other by a chimpanzee. In the documentary film James Stewart: A Wonderful Life (1987), hosted by Johnny Carson, Stewart said that he went back to Westerns in 1950 in part because of the string of flops.

He returned to the stage to star in Mary Coyle Chase's Harvey, which had opened to nearly universal praise in November 1944,[66] as Elwood P. Dowd, a wealthy eccentric living with his sister and niece, and whose best friend is an invisible rabbit as large as a man. Dowd's eccentricity, especially the friendship with the rabbit, is ruining the niece's hopes of finding a husband. While trying to have Dowd committed to a sanatorium, his sister is committed herself while the play follows Dowd on an ordinary day in his not-so-ordinary life. Stewart took over the role from Frank Fay and gained an increased Broadway following in the unconventional play.[66] The play, which ran for nearly three years with Stewart as its star, was successfully adapted into a 1950 film, directed by Henry Koster, with Stewart reprising his role and Josephine Hull portraying his sister. Bing Crosby was the first choice, but he declined.[67] Stewart received his fourth Best Actor nomination for his performance. Stewart also played the role on the London stage in 1975.

After Harvey, the World War II film Malaya (1949) with Spencer Tracy, and the conventional but highly successful biographical film The Stratton Story in 1949, Stewart's first pairing with "on-screen wife" June Allyson, his career took another turn.[68] During the 1950s, he expanded into the Western and suspense genres, thanks to collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann.

Other notable performances by Stewart during this time include the critically acclaimed 1950 Delmer Daves Western Broken Arrow, which featured Stewart as an ex-soldier and Indian agent making peace with the Apache; a troubled clown in the 1952 Best Picture The Greatest Show on Earth; and Stewart's role as Charles Lindbergh in Billy Wilder's 1957 The Spirit of St. Louis. He also starred in the Western radio show The Six Shooter for its one-season run from 1953 to 1954. During this time, Stewart wore the same cowboy hat and rode the same horse, "Pie", in most of his Westerns.[69][70]

Cary Grant said of Stewart's acting technique:

He had the ability to talk naturally. He knew that in conversations people do often interrupt one another and it's not always so easy to get a thought out. It took a little time for the sound men to get used to him, but he had an enormous impact. And then, some years later, Marlon came out and did the same thing all over again—but what people forget is that Jimmy did it first.[71]

Collaborations with Hitchcock and Mann

Stewart's collaborations with director Anthony Mann increased Stewart's popularity and sent his career into the realm of the western. Stewart's first appearance in a film directed by Mann came with the 1950 western, Winchester '73. In choosing Mann (after first choice Fritz Lang declined), Stewart cemented a powerful partnership.[72] The film, which became a massive box-office hit upon its release, set the pattern for their future collaborations. In it, Stewart is a tough, revengeful sharpshooter, the winner of a prized rifle which is stolen and then passes through many hands, until the showdown between Stewart and his brother (Stephen McNally).[72]

Other Stewart–Mann westerns, such as Bend of the River (1952), The Naked Spur (1953), The Far Country (1954) and The Man from Laramie (1955), were perennial favorites among young audiences entranced by the American West. Frequently, the films featured Stewart as a troubled cowboy seeking redemption, while facing corrupt cattlemen, ranchers and outlaws—a man who knows violence first hand and struggles to control it. The Stewart–Mann collaborations laid the foundation for many of the westerns of the 1950s and remain popular today for their grittier, more realistic depiction of the classic movie genre. Audiences saw Stewart's screen persona evolve into a more mature, more ambiguous, and edgier presence.[73]

Stewart and Mann also collaborated on other films outside the western genre. 1954's The Glenn Miller Story was critically acclaimed, garnering Stewart a BAFTA Award nomination, and (together with The Spirit of St. Louis) cemented the popularity of Stewart's portrayals of 'American heroes'. Thunder Bay, released the same year, transplanted the plot arc of their western collaborations to a more contemporary setting, with Stewart as a Louisiana oil driller facing corruption. Strategic Air Command, released in 1955, allowed Stewart to use his experiences in the United States Air Force on film.

Stewart's starring role in Winchester '73 was also a turning point in Hollywood. Universal Studios, who wanted Stewart to appear in both that film and Harvey, balked at his $200,000 asking price. His agent, Lew Wasserman, brokered an alternate deal, in which Stewart would appear in both films for no pay, in exchange for a percentage of the profits as well as cast and director approval.[74] Stewart ended up earning about $600,000 for Winchester '73 alone.[74] Hollywood's other stars quickly capitalized on this new way of doing business, which further undermined the decaying "studio system".[75]

The second collaboration to define Stewart's career in the 1950s was with acclaimed mystery and suspense director Alfred Hitchcock. Like Mann, Hitchcock uncovered new depths to Stewart's acting, showing a protagonist confronting his fears and his repressed desires. Stewart's first movie with Hitchcock was the technologically innovative 1948 film Rope, shot in long "real time" takes.[76]

The two collaborated for the second of four times on the 1954 hit Rear Window, widely considered one of Hitchcock's masterpieces. Stewart portrays photographer L.B. "Jeff" Jeffries, loosely based on Life photographer Robert Capa, who projects his fantasies and fears onto the people he observes out his apartment window while on hiatus due to a broken leg. Jeffries gets into more than he can handle, however, when he believes he has witnessed a salesman (Raymond Burr) commit a murder, and when his glamorous girlfriend (Grace Kelly), at first disdainful of his voyeurism and skeptical about any crime, eventually is drawn in and tries to help solve the mystery. Limited by his wheelchair, Stewart is led by Hitchcock to react to what his character sees with mostly facial responses. It was a landmark year for Stewart, becoming the highest grossing actor of 1954 and the most popular Hollywood star in the world, displacing John Wayne.[77] Hitchcock and Stewart formed a corporation, Patron Inc., to produce the film, which later became the subject of a Supreme Court case Stewart v. Abend (1990).

After starring in Hitchcock's remake of the director's earlier production, The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), with Doris Day, Stewart starred, with Kim Novak, in what many consider Hitchcock's most personal film, Vertigo (1958).[78] The movie starred Stewart as John "Scottie" Ferguson, a former police investigator suffering from acrophobia, who develops an obsession with a woman he is shadowing. Scottie's obsession inevitably leads to the destruction of everything he once had and believed in. Though the film is widely considered a classic today, Vertigo met with very mixed reviews and poor box-office receipts upon its release, and marked the last collaboration between Stewart and Hitchcock.[79] The director reportedly blamed the film's failure on Stewart looking too old to be Kim Novak's love interest, and cast Cary Grant as Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest (1959), a role Stewart had very much wanted. (Grant was actually four years older than Stewart but photographed much younger.) Today, Vertigo is ranked highest in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics poll for the greatest films ever made, taking the title from veteran favorite Citizen Kane.[80]

Career in the 1960s and 1970s

In 1960, Stewart was awarded the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor and received his fifth and final Academy Award for Best Actor nomination, for his role in the 1959 Otto Preminger film Anatomy of a Murder. The early courtroom drama stars Stewart as Paul Biegler, the lawyer of a hot-tempered soldier (played by Ben Gazzara) who claims temporary insanity after murdering a tavern owner who raped his wife. The film featured a career-making performance by George C. Scott as the prosecutor. The film was considered quite explicit for its time, and it was a box-office success.[81] Stewart's nomination was one of seven for the film (Charlton Heston was the winner with Ben-Hur), and saw his transition into the final decades of his career. It is ranked as one of the best trial films of all time.[82]

On January 1, 1960, Stewart received news of the death of Margaret Sullavan.[83] As a friend, mentor, and focus of his early romantic feelings, she had a unique influence on Stewart's life. On April 17, 1961, longtime friend Gary Cooper was too ill to attend the 33rd Academy Awards ceremony, so Stewart accepted the honorary Oscar on his behalf. Stewart's emotional speech hinted that something was seriously wrong, and the next day newspapers ran the headline, "Gary Cooper has cancer". One month later, on May 13, 1961, six days after his 60th birthday, Cooper died.

In the early 1960s, Stewart took leading roles in three John Ford films, his first work with the acclaimed director. The first, Two Rode Together, paired him with Richard Widmark in a Western with thematic echoes of Ford's The Searchers. The next, 1962's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Stewart's first picture with John Wayne, is a classic "psychological" western, shot in black and white film noir style featuring powerful use of shadows in the climactic sequence, with Stewart as an Eastern attorney who goes against his non-violent principles when he is forced to confront a psychopathic outlaw (played by Lee Marvin) in a small frontier town. At story's end, Stewart's character — now a rising political figure — faces a difficult ethical choice as he attempts to reconcile his actions with his personal integrity. The film's billing is unusual in that Stewart was given top billing over Wayne in the trailers and on the posters but Wayne was listed above Stewart in the film itself. The complex picture garnered mixed reviews but was an instant hit at the box office and became a critical favorite over the ensuing decades.

How the West Was Won (which Ford co-directed, though without directing Stewart's scenes) and Cheyenne Autumn were western epics released in 1962 and 1964 respectively. One of only a handful of movies filmed in true Cinerama, shot with three cameras and exhibited with three simultaneous projectors in theatres, How the West Was Won went on to win three Oscars and reap massive box-office figures. Cheyenne Autumn, in which a white-suited Stewart played Wyatt Earp in a long semi-comedic sequence in the middle of the movie, failed domestically and was quickly forgotten. The historical drama was Ford's final Western and Stewart's last feature film with Ford. Stewart's entertainingly memorable middle sequence is not directly connected with the rest of the film and was often excised from the lengthy film in later theatrical exhibition prints and some television broadcasts.

Having played his last romantic lead in Bell, Book and Candle (1958), and silver-haired (although not all was his—he wore a partial hairpiece starting with It's a Wonderful Life and in every film thereafter), Stewart transitioned into more family-related films in the 1960s when he signed a multi-movie deal with 20th Century Fox. These included the successful Henry Koster outing Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation (1962), and the less memorable films Take Her, She's Mine (1963) and Dear Brigitte (1965), which featured French model Brigitte Bardot as the object of Stewart's son's mash notes. The Civil War period film Shenandoah (1965) and the western family film The Rare Breed fared better at the box office; the Civil War movie, with strong antiwar and humanitarian themes, was a smash hit in the South.[citation needed]

As an aviator, Stewart was particularly interested in aviation films and had pushed to appear in several in the 1950s, including No Highway in the Sky (1951), and most notably Strategic Air Command (1955) and The Spirit of St. Louis (1957). He continued in this vein in the 1960s, most notably in a role as a hard-bitten pilot in The Flight of the Phoenix (1965). Subbing for Stewart, famed stunt pilot and air racer Paul Mantz was killed when he crashed the "Tallmantz Phoenix P-1", the specially made, single-engined movie airplane, in an abortive "touch-and-go". Stewart also narrated the film X-15 in 1961.[84] In 1964, he and several other military aviators, including Curtis LeMay, Paul Tibbets, and Bruce Sundlun were founding directors of the board of Tibbets' Executive Jet Aviation Corporation.[85]

After a progression of lesser western films in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stewart transitioned from cinema to television. In the 1950s he had made guest appearances on the Jack Benny Program. Stewart first starred in the NBC comedy The Jimmy Stewart Show, on which he played a college professor. He followed it with the CBS mystery Hawkins, in which he played a small town lawyer investigating cases, similar to his character in Anatomy of a Murder. The series garnered Stewart a Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Dramatic TV Series, but failed to gain a wide audience, possibly because it rotated with Shaft, another high-quality series but with a starkly conflicting demographic, and was cancelled after one season. During this time, Stewart periodically appeared on Johnny Carson's The Tonight Show, sharing poems he had written at different times in his life. His poems were later compiled into a short collection, Jimmy Stewart and His Poems (1989).[86][87]

Stewart returned to films after an absence of five years with a major supporting role in John Wayne's final film, The Shootist (1976) where Stewart played a doctor giving Wayne's gunfighter a terminal cancer diagnosis. At one point, both Wayne and Stewart were flubbing their lines repeatedly and Stewart turned to director Don Siegel and said, "You'd better get two better actors." Stewart also appeared in supporting roles in Airport '77, the 1978 remake of The Big Sleep starring Robert Mitchum as Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, and The Magic of Lassie (1978). All three movies received poor reviews, and The Magic of Lassie flopped at the box office.

Last years and later career

Following the failure of The Magic of Lassie, Stewart went into semi-retirement from acting. He donated his papers, films, and other records to Brigham Young University's Harold B. Lee Library in 1983.[88] Stewart had diversified investments including real estate, oil wells, a charter-plane company and membership on major corporate boards, and he became a multimillionaire. In the 1980s and '90s, he did voiceover work for commercials for Campbell's Soups.

Stewart's longtime friend Henry Fonda died in 1982, and former co-star and friend Grace Kelly died after a car crash shortly afterwards. A few months later, Stewart starred with Bette Davis in Right of Way. He filmed several television movies in the 1980s, including Mr. Krueger's Christmas, which allowed him to fulfill a lifelong dream to conduct the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.[89] He made frequent visits to the Reagan White House and traveled on the lecture circuit. The re-release of his Hitchcock films gained Stewart renewed recognition. Rear Window and Vertigo were particularly praised by film critics, which helped bring these pictures to the attention of younger movie-goers. He was presented an Academy Honorary Award by Cary Grant in 1985, "for his 50 years of memorable performances, for his high ideals both on and off the screen, with respect and affection of his colleagues".[63]

In 1988, Stewart made an impassioned plea in Congressional hearings, along with, among many others, Burt Lancaster, Katharine Hepburn, Ginger Rogers, and film director Martin Scorsese, against Ted Turner's decision to 'colorize' classic black and white films, including It's a Wonderful Life. Stewart stated, "the coloring of black-and-white films is wrong. It's morally and artistically wrong and these profiteers should leave our film industry alone".[90]

In 1989, Stewart founded the American Spirit Foundation to apply entertainment industry resources to developing innovative approaches to public education and to assist the emerging democracy movements in the former Iron Curtain countries. Peter F. Paul arranged for Stewart, through the offices of President Boris Yeltsin, to send a special print of It's a Wonderful Life, translated by Lomonosov Moscow State University, to Russia as the first American program ever to be broadcast on Russian television. On January 5, 1992, coinciding with the first day of the existence of the democratic Commonwealth of Independent States and Russia, and the first free Russian Orthodox Christmas Day, Russian TV Channel 2 broadcast It's a Wonderful Life to 200 million Russians who celebrated an American holiday tradition with the American people for the first time in Russian history.[91]

In association with politicians and celebrities such as President Ronald Reagan, Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger, California Governor George Deukmejian, Bob Hope and Charlton Heston, Stewart worked from 1987 to 1993 on projects that enhanced the public appreciation and understanding of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.[91]

In 1991, James Stewart voiced the character of Sheriff Wylie Burp in the movie An American Tail: Fievel Goes West, which was his last film role. Shortly before his 80th birthday, he was asked how he wanted to be remembered. "As someone who 'believed in hard work and love of country, love of family and love of community.'"[63]

Personal life

Stewart was almost universally described by his collaborators as a kind, soft-spoken man and a true professional.[92] Joan Crawford praised the actor as an "endearing perfectionist" with "a droll sense of humor and a shy way of watching you to see if you react to that humor".[63]

When Henry Fonda moved to Hollywood in 1934, he was again a roommate with Stewart in an apartment in Brentwood,[93] and the two gained reputations as playboys.[94] Both men's children later noted that their favorite activity when not working seemed to be quietly sharing time together while building and painting model airplanes, a hobby they had taken up in New York, years earlier.[95]

After World War II, Stewart settled down, at age 41, marrying former model Gloria Hatrick McLean on August 9, 1949. As Stewart loved to recount in self-mockery, "I, I, I pitched the big question to her last night and to my surprise she, she, she said yes!"[96] Stewart adopted her two sons, Michael and Ronald, and with Gloria he had twin daughters, Judy and Kelly, on May 7, 1951. The couple remained married until her death from lung cancer on February 16, 1994, at the age of 75. His stepson Ronald McLean was killed in action in Vietnam on June 8, 1969, at the age of 24, while serving as a lieutenant in the Marine Corps.[97][98] Daughter Kelly Stewart is a physical anthropologist.[99]

Stewart was active in philanthropy over the years. His signature charity event, "The Jimmy Stewart Relay Marathon Race", held each year since 1982, has raised millions of dollars for the Child and Family Development Center at St. John's Health Center in Santa Monica, California.[11] He was a lifelong supporter of Scouting, having been a Second Class Scout when he was a youth, an adult Scout leader, and a recipient of the prestigious Silver Buffalo Award from the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). In later years, he made advertisements for the BSA, which led to his being sometimes incorrectly identified as an Eagle Scout.[100] An award for Boy Scouts, "The James M. Stewart Good Citizenship Award" has been presented since May 17, 2003.[101]

Stewart was a Life Member of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of California.[102]

One of Stewart's lesser-known talents was his homespun poetry. Once, while on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, he read a poem entitled "Beau" that he had written about his dog. By the end of this reading, Carson's eyes were welling with tears.[103] This was later parodied on a late 1980s episode of the NBC sketch show Saturday Night Live, with Dana Carvey as Stewart reciting the poem on Weekend Update and bringing anchor Dennis Miller to tears. He was also an avid gardener. Stewart purchased the house next door to his Beverly Hills home, had it razed, and installed his garden on the lot.[104]

Politics

Stewart was a staunch Republican[105] and actively campaigned for Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. He was a hawk on the Vietnam War, and maintained that his son, Ronald, did not die in vain. Stewart actively supported Reagan's bid to win the Republican presidential nomination in 1976.

Following the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, Stewart, Charlton Heston, Kirk Douglas and Gregory Peck issued a statement calling for support of President Johnson's Gun Control Act of 1968.

One of his best friends was fellow actor Henry Fonda, despite the fact that the two had very different political ideologies. A political argument in 1947 resulted in a fistfight, but they maintained their friendship by never discussing politics again.[106] This tale may be apocryphal as Jhan Robbins quotes Stewart as saying: "Our views never interfered with our feelings for each other, we just didn't talk about certain things. I can't remember ever having an argument with him—ever!" However, Jane Fonda told Donald Dewey for his 1996 biography of Stewart that her father did have a falling out with Stewart at that time, although she did not know whether it was because of their political differences. There is a brief reference to their political differences in character in their movie The Cheyenne Social Club.[107] In the last years of his life, he donated to the campaign of Bob Dole in the 1996 presidential election and to Democratic Florida governor Bob Graham in his successful run for the Senate.[105]

Death

Stewart was hospitalized after falling over in December 1995.[108] In December 1996, he was due to have the battery in his pacemaker changed, but opted not to, preferring to let things happen naturally. In February 1997, he was hospitalized for an irregular heartbeat. On June 25, a thrombosis formed in his right leg, leading to a pulmonary embolism one week later.[109] Surrounded by his children on July 2, 1997, Stewart died at the age of 89 at his home in Beverly Hills, California, with his final words to his family being, "I'm going to be with Gloria now."[110] President Bill Clinton commented that America had lost a "national treasure ... a great actor, a gentleman and a patriot".[63] Over 3,000 mourners, mostly celebrities, attended Stewart's memorial service, which included a firing of three volleys for his service in the Army Air Forces and the U.S. Air Force.[111] Stewart's remains are interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.[112][113]

Filmography

From the beginning of Stewart's film career in 1935, through his final theatrical project in 1991, he appeared in more than 92 films, television programs and shorts. Five of his movies were included on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 greatest American films: Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Philadelphia Story, It's a Wonderful Life, Rear Window and Vertigo. His roles in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Philadelphia Story, It's a Wonderful Life, Harvey, and Anatomy of a Murder earned him Academy Award nominations—with one win for The Philadelphia Story.

Broadway performances

- Carry Nation as "Constable Gano" (October – November 1932)[114]

- Goodbye Again as "Chauffeur" (December 1932 – July 1933)[114]

- Spring in Autumn as "Jack Brennan" (October–November 1933)[114]

- All Good Americans as "Johnny Chadwick" (December 1933 – January 1934)[114]

- Yellow Jack as "Sgt. John O'Hara" (May 1934)[114]

- Divided By Three as "Teddy Parrish" (October 1934)[114]

- Page Miss Glory as "Ed Olsen" (November 1934 – March 1935)[114]

- A Journey By Night as "Carl" (April 1935)[114]

- Harvey as "Elwood P. Dowd" (July–August 1947, July–August 1948, replacing vacationing Frank Fay, who created the role on Broadway)[N 7]

- Harvey as "Elwood P. Dowd" (revival, February–May 1970)[114]

- A Gala Tribute to Joshua Logan as himself (March 9, 1975)[114]

Radio appearances

| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Screen Guild Players | The Shop Around the Corner[115] |

| 1948 | Readers' Digest Radio Edition | One Way to Broadway[115] |

| 1949 | Suspense | Mission Completed[115] |

| 1953 | Theatre Guild on the Air | O'Halloran's Luck''[116] |

Legacy

Throughout his seven decades in Hollywood, Stewart cultivated a versatile career and recognized screen image in such classics as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Mortal Storm, The Philadelphia Story, Harvey, It's a Wonderful Life, Shenandoah, Rear Window, Rope, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Shop Around the Corner, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Vertigo. He is the most represented leading actor on the AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) and AFI's 10 Top 10 lists. He is the most represented leading actor on the 100 Greatest Movies of All Time list presented by Entertainment Weekly. As of 2007, ten of his films have been inducted into the United States National Film Registry. As part of their 100 Years Series, Stewart was named the third greatest screen legend actor in American film history by the AFI in 1999.[4]

Stewart left his mark on a wide range of film genres, including westerns, suspense thrillers, family films, biographies, and screwball comedies. He worked for many renowned directors during his career, most notably Frank Capra, George Cukor, Henry Hathaway, Cecil B. DeMille, Ernst Lubitsch, Frank Borzage, George Stevens, Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, Billy Wilder, Don Siegel, and Anthony Mann. He won many of the industry's highest honors and earned Lifetime Achievement awards from every major film organization, and is often considered to be one of the most influential actors in the history of American cinema.

Honors and tributes

Stewart was the recipient of many official accolades throughout his life, receiving film industry awards, military and civilian medals, honorary degrees, and memorials and tributes for his contribution to the performing arts, humanitarianism, and military service.

The library at Brigham Young University houses his personal papers and movie memorabilia including his Academy Award for Best Actor.[117][118]

In February 1980, Stewart was honored by Freedoms Foundation of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, along with U.S. Senator Jake Garn, U.S. Ambassador Shirley Temple Black, singer John Denver, and Tom Abraham, a businessman from Canadian, Texas, who worked with immigrants seeking to become U.S. citizens.[119]

On May 20, 1995, his 87th birthday, The James M. Stewart Foundation was created to honor James Stewart. In concert with his family members, the foundation also established The Jimmy Stewart Museum in his hometown of Indiana, Pennsylvania. The foundation was created to "preserve, promote and enshrine the accomplishments of James M. Stewart, actor, soldier, civic leader, and world citizen..." The registered office is at 835 Philadelphia Street, Indiana, Pa, 15701 and is located within easy walking distance of his place of birth, the home in which he grew up, and the former location of his father's hardware store. A large statue of Stewart stands on the lawn of the Indiana County Courthouse, just feet from the museum.

The Jimmy Stewart Museum houses movie posters and photos, awards, personal artifacts, a gift shop and an intimate 1930's era theatre in which his films are regularly shown.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ MGM head Louis B. Mayer first tried to talk Stewart out of enlisting, claiming he would be sacrificing his career. "Mayer was just so desperate to say something that would keep me from enlisting", recalls Stewart... I said, "Mr. Mayer, this country's conscience is bigger than all the studios in Hollywood put together, and the time will come when we'll have to fight...The next thing he did was announce a big going-away party for me, and every star at the studio was summoned to be there... That was one big party."[2]

- ^ Stewart later confided that he had a 'friend' operating the weight scales.[33]

- ^ Stewart, who had taken the required ground school courses as an enlisted man, likely was rated under the newly established service pilot program for civilian pilots, although that program was restricted to noncombat flying. However with his unusual circumstances, and as one of the first to be so rated, he was awarded a standard pilot rating.[35]

- ^ Walter E. "Pop" Arnold became commander of the 485th Bombardment Group in September 1943 and his B-24 was shot down over eastern Germany on August 27, 1944, making him a prisoner of war.[43]

- ^ While leading the 445th on this date, Stewart made a decision in combat to not break formation from another group that had made an error in navigation. The other group lost four bombers in a subsequent interception, but Stewart's decision possibly saved it from annihilation and incurred considerable damage to his own 48 aircraft. His decision resulted in a letter of commendation and promotion to major on January 20, 1944. Sy Bartlett and Beirne Lay used the episode in their novel 12 O'Clock High.[40][44][45]

- ^ Although Stewart was always Capra's first choice, in an interview later in life, he conceded that "Henry Fonda was in the running."[59]

- ^ The reference does not mention the second set of dates, nor that Frank Fay created the role.[114]

Citations

- ^ "James Stewart, the Hesitant Hero, Dies at 89". The New York Times. July 3, 1997.

- ^ a b c Munn, Michael. Jimmy Stewart: The Truth Behind the Legend, Skyhorse Publishing (2013) ebook

- ^ Smith, Lynn (March 30, 2003). "In Supporting Roles". Los Angeles Times. p. 193.

- ^ a b "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Stars". American Film Institute (Afi.com). June 16, 1999. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ "James Stewart profile". FilmReference.com. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "Ancestry of Jimmy Stewart". genealogy.about.com. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "Movies: Best Pictures". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ "Jimmy Stewart profile". adherents.com. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biography". The Jimmy Stewart Museum. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Berg, A. Scott (1999). Lindbergh. New York, NY: Berkley/Penguin. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-425-17041-0.

- ^ "Princeton Triangle Club". princeton.edu. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ Fonda and Teichmann 1981, p. 74.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 74.

- ^ Eliot 2006, pp. 84, 87.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Wayne 2004, p. 447.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Jones, McClure and Twomey 1970, p. 67.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Brigadier General James Stewart". National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 26.

- ^ "Thunderbird Field". airfields-freeman.com. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Smith 2005, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d "Brigadier General James Stewart". Something About Everything Military. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c McGowan, Sam. "From Private to Colonel". WWII History, Volume 11, July 2012, p. 42.

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 181.

- ^ Biederman, Patricia Ward. "Winning the war, one frame at a time". Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2002. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 2005, p. 273.

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ McGowan "From Private to Colonel", p. 43.

- ^ "485th Stories". 485thbg.org.

- ^ a b c McGowan "From Private to Colonel", p. 44.

- ^ Bowman 1979, p. 26.

- ^ McGowan "From Private to Colonel", p. 45.

- ^ McGowan "From Private to Colonel", pp. 45–46.

- ^ McGowan "From Private to Colonel", pp. 46–47.

- ^ McGowan "From Private to Colonel", p. 47.

- ^ Maurer 1983, p. 375.

- ^ Helmreich, Dr. Jonathan E. "The Bombing of Zurich". Maxwell Air Force Base. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ "FBI Award". FBI. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Swopes, Bryan R. (February 20, 2014). "20 February 1966 | This Day in Aviation". Photo credits: Bettmann/CORBIS, U.S. Air Force, Los Angeles Times, AP, RAF Old Buckenham. thisdayinaviation.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 5, 2014 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stewart profile". U.S. Air Force. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 196.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 199.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 197.

- ^ a b Cox 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 203.

- ^ Cox 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e "Obituary: James Stewart, the hesitant hero, dies at 89". The New York Times, July 3, 1997.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 211.

- ^ Eliot 2006, pp. 208, 211.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, p. 214.

- ^ Eliot 2006, pp. 208, 213.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 237.

- ^ "James Stewart's Horse". Wild West net. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "James Stewart profile". Film Reference.com. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Jimmy Stewart: The Biggest Little Man". Orlando Sentinel.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 251.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, p. 245.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 254.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 278.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 310.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 321.

- ^ "Vertigo is named 'greatest film of all time'". BBC News, August 2, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 332.

- ^ Verone, Patric M. "The 12 Best Trial Movies". ABA Journal. November 1989 reprinted in Nebraska Law Journal.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 337.

- ^ "X-15 (film) Full credits". IMDb. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ "Paul Tibbets: A Rendezvous With History, Part 3". Airport Journals, June 2003.

- ^ Krier, Beth Ann. "The muse within Jimmy Stewart". Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1989.

- ^ Stewart, Jimmy (August 19, 1989). Jimmy Stewart and His Poems. Crown. ISBN 978-0517573822.

- ^ Tollestrup, Jon. "Collections: Thousands of Artifacts, Centuries of History" The Daily Universe, February 13, 2006.

- ^ Bauman, Joe (January 26, 2009). "Utah-Hollywood connection runs deep". Deseret News. p. B2.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 405.

- ^ a b "James Stewart profile". IMDb. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Eliot 2006, pp. 164–68.

- ^ Fonda and Teichmann 1981, p. 106.

- ^ Fonda and Teichmann 1981, pp. 107–08.

- ^ Fonda and Teichmann 1981, p. 97.

- ^ Eliot 2006, p. 239.

- ^ "Gloria Stewart obituary". The New York Times, February 18, 1994.

- ^ "1LT Ronald Walsh McLean". VirtualWall.org. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "Kelly Stewart". anthro.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved March 7, 2012. Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lawson, Terry C. Erroneous Eagle Scouts Letter. Eagle Scout Service, National Eagle Scout Association, Boy Scouts of America (2005). Retrieved June 9, 2005.

- ^ "James M. Stewart Good Citizenship Award", jimmy.org. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ "It's a Wonderful Life for a fellow member!!" srcalifornia.com, Fall 1995. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ McMahon, Ed. "Ed McMahon says farewell to Johnny Carson". MSNBC, September 12, 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Nichols, Mary E. "James Stewart: The Star of It’s a Wonderful Life and The Philadelphia Story in Beverly Hills". Architectural Digest. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ a b "Political Donations". newsmeat.com. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Robbins 1985, p. 99.

- ^ The Cheyenne Social Club at IMDb

- ^ "James Stewart Hospitalized After Falling at His Home". 22 December 1995 – via LA Times.

- ^ James Stewart's death certificate

- ^ "James Stewart – Classic Cinema Gold".

- ^ "James Stewart Biography". The Biography Channel. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ James Stewart at Find a Grave

- ^ Ellenberger, Allan R. (2001). Celebrities in Los Angeles Cemeteries: A Directory. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7864-0983-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "James Stewart (I) – Other works". imdb.com. April 27, 2014. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Those Were The Days". Nostalgia Digest. 41 (3): 32–39. Summer 2015.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (March 1, 1953). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 46. Retrieved June 23, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jimmy Stewart". Deseret News. July 4, 1997.

- ^ Carter, Edward L. (July 4, 1997). "BYU ready to expand its Stewart collection". Deseret News.

- ^ "Tom Abraham to be honored by Freedoms Foundation Feb. 22", Canadian Record, Canadian, Texas, February 14, 1980, p. 19.

Bibliography

- Beaver, Jim. "James Stewart". Films in Review, October 1980.

- Bowman, Martin. B-24 Liberator 1939–1945, London: Patrick Stephens Ltd., 1979 ISBN 978-0-52881-538-6.

- Coe, Jonathan. James Stewart: Leading Man. London: Bloomsbury, 1994. ISBN 978-0-14029-467-5.

- Collins, Thomas W. Jr."Stewart, James". American National Biography Online. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- Cox, Stephen. It's a Wonderful Life: A Memory Book. Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House, 2003. ISBN 978-1-58182-337-0.

- Eliot, Mark. Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2006. ISBN 978-1-40005-222-6.

- Fonda, Henry as told to Howard Teichmann. Fonda: My Life. New York: A Signet Book, New American Library, 1981. ISBN 0-451-11858-8.

- Houghton, Norris. But Not Forgotten: The Adventure of the University Players. New York: William Sloane Associates, 1951.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., Karen Markoe and Arnie Markoe. The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives (5). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998. ISBN 0-684-80663-0.

- Jones, Ken D., Arthur F. McClure and Alfred E. Twomey. The Films of James Stewart. New York: Castle Books, 1970.

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-02-1

- McGowan, Helene. James Stewart. London: Bison Group, 1992, ISBN 0-86124-925-9.

- McGowan, Sam. "From Private to Colonel". WWII History, Volume 11, July 2012, pp. 40–47.

- Pickard, Roy. Jimmy Stewart: A Life in Film. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0-312-08828-0.

- Prendergast, Tom and Sara, eds. "Stewart, James". International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers, 4th edition. London: St. James Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55862-450-3.

- Prendergast, Tom and Sara, eds. "Stewart, James". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 5th edition. London: St. James Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55862-529-1.

- Robbins, Jhan. Everybody's Man: A Biography of Jimmy Stewart. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1985. ISBN 0-399-12973-1.

- Smith, Starr. Jimmy Stewart: Bomber Pilot. St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press, 2005. ISBN 0-7603-2199-X.

- Thomas, Tony. A Wonderful Life: The Films and Career of James Stewart. Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8065-1081-1.

- Wayne, Jane Ellen.The Leading Men of MGM. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-7867-1475-1.

- Wright, Stuart J. An Emotional Gauntlet: From Life in Peacetime America to the War in European Skies—A History of 453rd Bomb Group Crews. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004. ISBN 0-299-20520-7.

External links

This section's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (May 2012) |

- Finding aid author: Mary-Celeste Ricks (2015). "His Wonderful Life: A Tribute to James Stewart". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Finding aid authors: James V. D'Arc and John N. Gillespie (2014). "John Strauss files on publicity for James Stewart". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Finding aid authors: Karen Glenn and John Murphy (2013). "WNET transcripts for James Stewart : A Wonderful Life". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- James Stewart at the Internet Broadway Database

- James Stewart at IMDb

- Jimmy Stewart at the TCM Movie Database

- Jimmy Stewart Museum

- The American Spirit Foundation

- Feaster, Felicia. James Stewart Profile at Turner Classic Movies

- "Princeton to Honor Famed Alumnus Jimmy Stewart '32 With Tribute and Theater Dedication", Princeton University (1997)

- Centennial Tribute to James Stewart

- "Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time"

- "Mr. Stewart Goes to Vietnam", article from Vietnam magazine about Stewart's B-52 mission in 1966

- Images: Stewart Pictures. Telecommunication & Film Department, University of Alabama

- Images: "Col. James M. Stewart stands with his father outside of the family's hardware store", Life Magazine (1945)

- A Wonderful Life: Jimmy Stewart, Actor and B-24 Bomber Pilot

- James Stewart in the 1910 US Census, 1920 US Census, 1930 US Census, and the Social Security Death Index.

- Photos of Jimmy Stewart in 'Pot O Gold' by Ned Scott

- James Stewart(Aveleyman)

- James Stewart interview on BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs, December 23, 1983

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from May 2012

- 1908 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American poets

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- American male film actors

- American male poets

- American male radio actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American male writers

- American military personnel of the Vietnam War

- American military personnel of World War II

- American people of Scottish descent

- American Presbyterians

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (television) winners

- Broadway theatre people

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- California Republicans

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- Deaths from pulmonary embolism

- Disease-related deaths in California

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Male actors from Beverly Hills, California

- Male actors from Pennsylvania

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Mercersburg Academy alumni

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- Pennsylvania Republicans

- People from Indiana, Pennsylvania

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Princeton University alumni, 1930–39

- RCA Victor artists

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the Croix de guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award

- Silver Bear for Best Actor winners

- United States Air Force generals

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

- Volpi Cup winners