English language: Difference between revisions

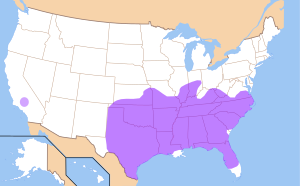

→North America: oops I placed this in the wrong sections, not a northern cities trait but a SAE trait |

→top: shorten the second paragraph to describe the traditional cut-off points for periods of English (deleted etymology and mention of Old Norse) |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

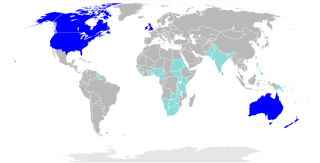

'''English''' is a [[West Germanic languages|West Germanic language]] that was first spoken in [[Anglo-Saxon England|early medieval England]] and is now a global ''[[lingua franca]]''.<ref name="CrystalGlobalLanguage2003p6" /><ref name="Wardhaugh2010p55" /> It is an [[official language]] of [[list of territorial entities where English is an official language|almost 60 sovereign states]] and the most commonly spoken language in sovereign states including the [[United Kingdom]], the [[United States]], [[Canada]], [[Australia]], [[Republic of Ireland|Ireland]], [[New Zealand]] and a number of [[Caribbean]] nations. It is the [[List of languages by number of native speakers|third-most-common native language]] in the world, after [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]] and [[Spanish language|Spanish]].<ref name="Ethnologue" /> It is widely learned as a [[second language]] and is an [[Languages of the European Union|official language of the European Union]] and of the [[Official languages of the United Nations|United Nations]], as well as of many world organisations. |

'''English''' is a [[West Germanic languages|West Germanic language]] that was first spoken in [[Anglo-Saxon England|early medieval England]] and is now a global ''[[lingua franca]]''.<ref name="CrystalGlobalLanguage2003p6" /><ref name="Wardhaugh2010p55" /> It is an [[official language]] of [[list of territorial entities where English is an official language|almost 60 sovereign states]] and the most commonly spoken language in sovereign states including the [[United Kingdom]], the [[United States]], [[Canada]], [[Australia]], [[Republic of Ireland|Ireland]], [[New Zealand]] and a number of [[Caribbean]] nations. It is the [[List of languages by number of native speakers|third-most-common native language]] in the world, after [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]] and [[Spanish language|Spanish]].<ref name="Ethnologue" /> It is widely learned as a [[second language]] and is an [[Languages of the European Union|official language of the European Union]] and of the [[Official languages of the United Nations|United Nations]], as well as of many world organisations. |

||

English had several historical forms. The earliest form was [[Old English]], a set of [[Anglo-Frisian languages|Anglo-Frisian dialects]] brought to [[Great Britain]] by [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon settlers]] in the 5th century. [[Middle English]] began in the late 11th century, after the [[Norman conquest of England]]. [[Early Modern English]] began in the late 15th century with the introduction of the [[printing press]] to [[London]] and the [[Great Vowel Shift]]. |

|||

English arose in the [[List of Anglo-Saxon monarchs and kingdoms|Anglo-Saxon kingdoms]] of England as a fusion of closely related [[dialect]]s, now collectively termed [[Old English]]. These dialects had been brought to the south-eastern coast of Great Britain by [[Anglo-Saxons]] settlers by the 5th century. The word ''English'' is the modern spelling of ''englisc'', the name used by the [[Angles]] and Saxons for their language, after the Angles' ancestral region of [[Angeln]]. The language was also influenced early on by the [[Old Norse|Old Norse language]] through [[Danelaw|Viking invasions]] in the 9th and 10th centuries. The [[Norman conquest of England]] in the 11th century gave rise to heavy borrowings from [[Norman language|Norman French]]: adding a layer of vocabulary and [[Romance languages|Romance-language]] spelling conventions to what had by then become [[Middle English]]. The [[Great Vowel Shift]] that began in the south of England in the 15th century is one of the processes that mark the emergence of [[Modern English]]. |

|||

Through the worldwide influence of [[Kingdom of England|England]], [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]], and the United Kingdom from the 17th to mid-20th centuries under the [[British Empire]], it has been [[English-speaking world|widely propagated]] around the world. Through the spread of English literature, world media networks such as the [[BBC]], the emergence of the [[US]] as a global [[superpower]], and the Internet, English has become the [[World language|leading language]] of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and in professional contexts such as science. |

Through the worldwide influence of [[Kingdom of England|England]], [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]], and the United Kingdom from the 17th to mid-20th centuries under the [[British Empire]], it has been [[English-speaking world|widely propagated]] around the world. Through the spread of English literature, world media networks such as the [[BBC]], the emergence of the [[US]] as a global [[superpower]], and the Internet, English has become the [[World language|leading language]] of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and in professional contexts such as science. |

||

Revision as of 03:12, 17 March 2015

| English | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/[1] |

| Region | Originally Great Britain now worldwide (see Geographical distribution, below) |

Native speakers | 360–400 million (2006)[2] L2 speakers: 400 million; as a foreign language: 600–700 million[2] |

Early forms | |

| Latin script (English alphabet) English Braille | |

| Manually coded English (multiple systems) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | 67 countries 27 non-sovereign entities |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | en |

| ISO 639-2 | eng |

| ISO 639-3 | eng |

| Glottolog | stan1293 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA |

Countries of the world where English is an official or de facto official language or a majority language

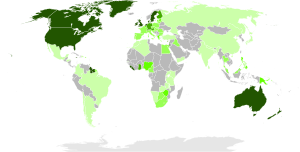

Countries where English is an official but not majority native language | |

English is a West Germanic language that was first spoken in early medieval England and is now a global lingua franca.[3][4] It is an official language of almost 60 sovereign states and the most commonly spoken language in sovereign states including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and a number of Caribbean nations. It is the third-most-common native language in the world, after Mandarin and Spanish.[5] It is widely learned as a second language and is an official language of the European Union and of the United Nations, as well as of many world organisations.

English had several historical forms. The earliest form was Old English, a set of Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century. Middle English began in the late 11th century, after the Norman conquest of England. Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the introduction of the printing press to London and the Great Vowel Shift.

Through the worldwide influence of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom from the 17th to mid-20th centuries under the British Empire, it has been widely propagated around the world. Through the spread of English literature, world media networks such as the BBC, the emergence of the US as a global superpower, and the Internet, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and in professional contexts such as science.

Classification

English is an Indo-European language, and belongs to the West Germanic group of the Germanic languages.[6] Most closely related to English are the Frisian languages, and English and Frisian form the Anglo-Frisian subgroup within West Germanic. Modern English descends from Middle English, which in turn descends from Old English. English and all the Germanic languages descend from Proto-Germanic. Sometimes Anglo-Frisian is grouped together with Old Saxon and its descendent Low German languages, as a group labeled "Ingvaeonic" or "North Sea Germanic".[7] Middle English also developed into a number of other English languages, including Scots[8] and the extinct Fingallian and Forth and Bargy dialects of Ireland.[9]

English is classified as a Germanic language because it shares new language features (different from other Indo-European languages) with other Germanic languages like Dutch, German, and Swedish. These shared innovations show that the languages have descended from a single common ancestor, which linguists call Proto-Germanic. Some shared features of Germanic languages are the use of modal verbs, the division of verbs into strong and weak classes, and the sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants, known as Grimm's and Verner's laws. Through Grimm's law, the word for foot begins with f in Germanic languages, but its cognates in other Indo-European languages begin with p. It is classified as an Anglo-Frisian language because Frisian and English share other features, such as the palatalization of consonants that were velar consonants in Proto-Germanic.

- English foot, German Fuß, Norwegian and Swedish fot (initial f derived from Proto-Indo-European p through Grimm's law)

- Latin pes, stem ped-; Modern Greek πόδι pódi; Russian под pod; Sanskrit पद् pád (original Proto-Indo-European p)

- English cheese, Frisian tsiis (ch and ts from palatalization)

- German Käse and Dutch kaas (k without palatalization)

English, like the other insular Germanic languages, Icelandic and Faroese, developed independently of the continental Germanic languages and their influences. Thus English is not mutually intelligible with any continental Germanic language, differing in vocabulary, syntax, and phonology, although some, such as Dutch, do show strong affinities with English, especially with its earlier stages.

Because English through its history has changed considerably in response to contact with other languages, particularly Old Norse and Norman French, some scholars have argued that English can be considered a mixed language or a creole - a theory called the Middle English creole hypothesis. Although the high degree of influence from these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern English is widely acknowledged, English is not considered by most specialists in language contact to be a true mixed language.[10][11]

History

From Proto-Germanic to Old English

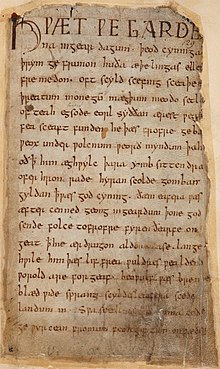

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings..."

The earliest form of English is Old English or Anglo-Saxon (c. 550–1066 AD). Old English developed from a set of North Sea Germanic dialects originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony, Jutland and Southern Sweden by Germanic tribes known as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. In the fifth century AD, the Anglo-Saxons settled Britain and the Romans withdrew from Britain. By the seventh century, the Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons became dominant in Britain, replacing the languages of Roman Britain (43–409 AD): Common Brittonic, a Celtic language, and Latin, brought to Britain by Roman invasion.[12][13][14] England and English (originally Anglaland and Englisc) are named after the Angles.[15]

Old English was divided into four main dialect groups, the Anglian dialects, Mercian and Northumbrian, and the Saxon dialects, Kentish and West Saxon.[16] Being composed of these two main groups, Old English is sometimes called Anglo-Saxon. Through the influence of Wessex, the West Saxon dialect became the most prestigious form of the language, and with the educational reforms of scholar-king Alfred the Great in the 9th century it became the standard written variety.[17] Most of the first works of Old English literature are written in this dialect, such as the epic poem Beowulf, but the earliest English poem, Cædmon's Hymn, was written in Northumbrian, the ancestor of the Scots language.[18] Old English and Old Frisian were originally written using a runic script.[19] By the 6th century, a Latin alphabet was adopted, written with half-uncial letterforms. It included the runic letters wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩, and the modified Latin letters eth ⟨ð⟩, and ash ⟨æ⟩.[20]

Old English is very different from Modern English and difficult for English speakers to understand. As in modern German, nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs in Old English had many inflectional endings and forms. Because of the inflectional system, word order was much freer, although verbs tended to occur in second position in a sentence as in modern German and Scandinavian. Nouns and adjectives had three genders, four cases, and two or three numbers, and adjectives changed form to agree with the gender, case, and number of the nouns they modified. Like Modern English, Old English had two simple tenses, present and past, but there were more person and number forms, a subjunctive mood, and more strong verbs.[21][22][23]

The translation of Matthew 8:20 from 1000 AD shows how grammatical case was used in Old English:

- Foxas habbað holu and heofonan fuglas nest

- Fox-as habb-að hol-u and heofon-an fugl-as nest-∅

- fox-NOM.PL have-PRS.PL hole-ACC.PL and heaven-GEN.SG bird-NOM.PL nest-ACC.PL

- "Foxes have holes and the birds of heaven nests"[24]

Middle English

Englischmen þeyz hy hadde fram þe bygynnyng þre manner speche, Souþeron, Northeron, and Myddel speche in þe myddel of þe lond, ... Noþeles by comyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes, and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys asperyed, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbytting.

Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, ... Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing.

John of Trevisa, ca. 1385[25]

In the period from the 8th to the 12th century, Old English was gradually transformed through language contact into Middle English. Middle English is often arbitrarily defined as beginning with the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, but it was fully developed in the period from 1200-1450.

First, the waves of Norse colonisation of northern parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries put Old English into intense contact with Old Norse, a North Germanic language. Norse influence was strongest in the Northeastern varieties of Old English spoken in the Danelaw area around York, which was the center of Norse colonisation; today these features are still particularly present in Scots and Northern English. However the center of norsified English seems to have been in the Midlands around Lindsey, and after 920 AD when Lindsey was reincorporated into the Anglo-Saxon polity, Norse features spread from there into English varieties that had not been in intense contact with Norse speakers. Some elements of Norse influence that persist in all English varieties today are the pronouns beginning with th- (they, them, their) which replaced the Anglo-Saxon pronouns with h- (hie, him, hera) and words such as same (from Norse samr, sama) which replaced the original ilka. While most of the Norse influence was in vocabulary, it also affected phonological and morphological processes (e.g. the loss of the prefix ȝe- [Old English ge-] on perfect participles), and syntax.[26]

With the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the now norsified Old English language was subject to contact with the Old Norman language, a Romance language closely related to Modern French, eventually developing into Anglo-Norman. Due to the fact that Norman was spoken primarily by the elites and nobles, whereas the lower classes continued speaking Anglo-Saxon, the influence of Norman consisted in introducing a wide range of loan words related to politics, legislation and prestigious social domains. An example of Norman influence is the introduction of words for domestic animals and the food products derived from their meat, often cited are pairs swine and pork, cow and beef, lamb and mutton, where the first word in each pair is a Germanic word derived from Old English denoting the animal, and the second a word of Norman origin now denotes only the meat for consumption. Nonetheless the original Norman loans were also used to refer to the animal, but gradually shifted towards describing only the meat by the 18th century (other Norman words that continued to refer to the animal are the words dog (opposed to OE "hound") and cattle).[27] Middle English also simplified the inflectional system. The distinction between nominative and accusative case was lost, the instrumental case was dropped, and the use of the genitive case was limited to describing possession. The inflectional system regularized many irregular inflectional forms[28], and gradually simplified the system of agreement, making word order less flexible.[29] By the 1380s the Wycliffe Bible the passage Matthew 8:20 was written[citation needed]:

- Foxis han dennes, and briddis of heuene han nestis

Here the plural suffix -n on the verb "have" is still retained, but none of the case endings on the nouns are present.

By the 12th century Middle English was fully developed, integrating both Norse and Norman traits, it continued to be spoken until around 1500. Middle English literature include Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, and Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. In the Middle English period the use of regional dialects in writing proliferated, and dialect traits were even used for effects by authors such as Chaucer.

Development of Early Modern English

The next period in English was Early Modern English (1500–1700). Early Modern English was characterized by the Great Vowel Shift (1350–1700), inflectional simplification, and linguistic standardization.

The Great Vowel Shift affected the stressed long vowels of Middle English. It was a chain shift, meaning that each shift triggered a subsequent shift in the vowel system. Mid and open vowels were raised, and close vowels were broken into diphthongs. For example the word bite was originally pronounced as the word beet is today, and the second vowel in the word about was pronounced as the word boot is today. The Great Vowel Shift explains many irregularities in spelling, since English retains many spellings from Middle English, and it also explains why English vowel letters have very different pronunciations from the same letters in other languages.[30][31]

English began to rise in prestige during the reign of Henry V. Around 1430, the Court of Chancery in Westminster began using English in its official documents, and a new standard form of Middle English, known as Chancery Standard, developed from the dialects of London and the East Midlands. In 1476, William Caxton introduced the printing press to England and began publishing the first printed books in London, expanding the influence of this form of English.[32] Literature from the Early Modern period includes the works of William Shakespeare and the translation of the Bible commissioned by King James I. Even after the vowel shift the language still sounded different from Modern English: for example, the consonant clusters /kn gn sw/ in knight, gnat, and sword were still pronounced. Many of the grammatical features that a modern reader of Shakespeare might find quaint or archaic represent the distinct characteristics of Early Modern English.[33]

In the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, written in Early Modern English, Matthew 8:20 says:

- The Foxes haue holes and the birds of the ayre haue nests[24]

This exemplifies the loss of case and its effects on sentence structure (replacement with Subject-Verb-Object word order, and the use of of instead of the non-possessive genitive), and the introduction of loanwords from French (ayre) and word replacements (bird originally meaning "nestling" had replaced OE fugol).

Colonial spread of Modern English

In the late 18th century the British American colonies became the first parts of the British empire to achieve independence, and the subsequent period saw English become a global, pluricentric language. As England continued to form new colonies, these in turn became independent and developed their own norms for how to speak and write the language. English was adopted in North America, India, parts of Africa, Australasia, and many other regions – a trend that was reinforced by the emergence of the United States as a superpower in the mid-20th century. In the post-colonial period, some of the newly created nations that had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as the official language to avoid the political difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others. By the 21st century, English was more widely spoken and written than any language has ever been.[34]

A major feature in the early development of Modern English was the codification of explicit norms for standard usage, and their dissemination through official media such as public education and state sponsored publications. In 1755 Dr. Samuel Johnson published his A Dictionary of the English Language which introduced a standard set of spelling conventions and usage norms. In 1828, Noah Webster published the American Dictionary of the English language in an effort to establish a norm for speaking and writing American English that was independent from the British standard. Within Britain, non-standard or lower class dialect features were increasingly stigmatized, leading to the quick spread of the prestige varieties among the middle classes.[35]

In terms of grammatical evolution, Modern English has now reached a stage where the loss of case is almost complete (case is now only found in pronouns, such as he and him, she and her, who and whom), and where SVO word-order is mostly fixed.[35] Some changes, such as the use of do-support has become universalized (earlier English did not use the word "do" as a general auxiliary as Modern English does, it was only used in questions), and the usage of progressive forms in -ing, appear to be spreading to new constructions (e.g. do support with the verb have is becoming increasingly standardized and forms such as had been beeing built are becoming more common). Regularizations of irregular forms also slowly continues to spread (e.g. dreamed instead of dreamt), and analytical alternatives to inflectional forms are becoming more common (e.g. more polite instead of politer). British English is also experiences changes under the influence of American English, fueled by the strong presence of American English in the media and the prestige associated with the US as a world power, such as the reintroduction of the subjunctive in mandative statements (e.g. They ordered that she arrive punctually). Nonetheless, several linguists working with language change have suggested that the American influence on other English varieties is less pervasive than the popular opinion often suggests.[36][37][38]

Geographical distribution

Pie chart showing the relative proportions of native English speakers in the major English-speaking countries of the world.

Approximately 359 million people speak English as their first language. English today is probably the third largest language by number of native speakers, after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish.[5][39] However, when combining native and non-native speakers it is probably the most commonly spoken language in the world.[34][40]

Estimates that include second language speakers vary greatly from 470 million to more than a billion depending on how literacy or mastery is defined and measured.[41] Linguistics professor David Crystal calculates that non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.[40] The countries with the highest populations of native English speakers are, in descending order: the United States (229 million),[42] the United Kingdom (60 million),[43] Canada (18.2 million),[44] Australia (15.5 million),[45] Nigeria (4 million),[46] Ireland (3.8 million),[43] South Africa (3.7 million),[47] and New Zealand (3.6 million) in a 2006 Census.[48] Countries such as the Philippines, Jamaica and Nigeria also have millions of native speakers of dialect continua ranging from an English-based creole to a more standard version of English. Of those nations where English is spoken as a second language, India has the most such speakers (see Indian English). Crystal claims that, combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or understand English than any other country in the world.[49]

English as a global language

Modern English, sometimes described as the first global lingua franca,[50] is the world's mostly widely used language in communications, science, information technology, business, entertainment, radio, and diplomacy[51] and the required international language of seafaring[52] and aviation.[53] Its spread beyond the British Isles began with the growth of the English overseas possessions, and by the 19th century the reach of the British Empire was global.[54] As a result of overseas colonization from the 16th to 19th centuries, it became the dominant language in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The growing economic and cultural influence of the US and its status as a global superpower since the Second World War have significantly accelerated the spread of the language across the planet.[50][55] English replaced German as the dominant language of science-related Nobel Prize laureates during the second half of the 20th century.[56] It achieved parity with French as a language of diplomacy at the Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919.[57][58] By the time of the foundation of the United Nations after World War II, English had become pre-eminent[59][60] and is now the language of diplomacy and international relations.[61]

A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of fields, occupations and professions such as medicine and computing; as a consequence, more than a billion people speak English to at least a basic level (see English as a second or foreign language). It is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[62]

Because English is so widely spoken, it has often been referred to as a "world language", the lingua franca of the modern era,[50] and while it is not an official language in most countries, it is currently the language most often taught as a foreign language.[50][55] It is, by international treaty, the official language for aeronautical[63] and maritime[64] communications. English is one of the official languages of the United Nations and many other international organisations, including the International Olympic Committee.

This increasing use of the English language globally has had a large impact on many other languages, leading to language shift and even language death,[65] and to claims of linguistic imperialism.[66] English itself has become more open to language shift as multiple regional varieties feed back into the language as a whole.[66]

Phonology

The phonology of English differs between dialects, and so does the pronunciation. This overview mainly describes the standard pronunciations of the United Kingdom and the United States: Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA). The phonetic symbols used below are from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), and are used in the pronunciation keys of many dictionaries.

Consonants

English dialects share most of the same consonant phonemes, and consonant pronunciation varies less than that of vowels.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | (x) | h | ||||

| Approximant | r | j | (ʍ) | w | ||||||||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||||||||

Where consonants are given in pairs, as with /p b/, the first is voiceless, the second is voiced.

It is more accurate to say that voiceless and voiced consonants are fortis and lenis, since they are not always phonetically voiceless and voiced. The fortis and lenis stops are distinguished by varying levels of voice-onset time (aspiration and voicing) and sometimes by length of the preceding vowel. The fortis stop /p/ is always voiceless, but is aspirated in pin [pʰɪn], and unaspirated in spin [spɪn] and often in nip [nɪp]. The lenis stop /b/ is always unaspirated, but is partially voiced in bin [[voice (phonetics)|[p̬ɪn]]] and nib [nɪˑp̬], and fully voiced in about [əˈbaʊt]. Within the same syllable, a vowel before a lenis stop is longer than a vowel before a fortis stop: thus nib [nɪˑp̬] has a longer vowel than nip [nɪp] (see below).

There are significant dialectal variations in the pronunciation of several consonants:

- The th sounds /θ/ and /ð/ are sometimes pronounced as /f/ and /v/ in Cockney, and as dental plosives (contrasting with the usual alveolar plosives) in some dialects of Irish English. In African American Vernacular English, /ð/ has merged with dental /d/.[clarification needed]

- In North American and Australian English, /t/ and /d/ are pronounced as an alveolar flap [ɾ] in many positions between vowels:[67] thus words like latter and ladder /læɾər/ are pronounced in the same way. This sound change is called intervocalic alveolar flapping, and is a type of rhotacism. /t/ is often pronounced as a glottal stop [ʔ] (t-glottalization, a form of debuccalization) after vowels in British English, as in butter /ˈbʌʔə/, and in other dialects before a nasal, as in button /ˈbʌʔən/.

- In most dialects, the rhotic consonant /r/ is pronounced as an alveolar, postalveolar, or retroflex approximant [ɹ ɹ̠ ɻ], and often causes vowel changes or is elided (see below), but in Scottish it may be a flap or trill [ɾ r].

- In some cases, the palatal approximant or semivowel /j/, especially in the diphthong /juː/, is elided or causes consonant changes (yod-dropping and yod-coalescence).

- Through yod-dropping, historical /j/ in the diphthong /juː/ is lost. In both RP and GA, yod-dropping happens in words like chew /ˈtʃuː/, and frequently in suit /ˈsuːt/, historically /ˈtʃju ˈsjuːt/. In words like tune, dew, new /ˈtjuːn ˈdjuː ˈnjuː/, RP keeps /j/, but GA drops it, so that these words have the vowels of too, do, and noon /ˈtuː ˈduː ˈnuːn/ in GA. A few conservative dialects like Welsh English have less yod-dropping than RP and GA, so that chew and choose /ˈtʃɪu ˈtʃuːz/ are distinguished, and Norfolk English has more, so that beauty /ˈbjuːti/ is pronounced like booty /ˈbuːti/.

- Through yod-coalescence, alveolar stops and fricatives /t d s z/ are palatalized and change to postalveolar affricates or fricatives /tʃ dʒ ʃ ʒ/ before historical /j/. In GA and traditional RP, this only happens in unstressed syllables, as in education, nature, and measure /ˌɛd͡ʒʊˈkeɪʃən ˈneɪt͡ʃər ˈmɛʒər/. In other dialects, such as modern RP or Australian, it happens in stressed syllables: thus due and dew are pronounced like Jew /ˈdʒuː/. In colloquial speech, it happens in phrases like did you? /dɪdʒuː/.

- In conservative dialects lik Scottish English, the digraph wh is pronounced as a voiceless w [ʍ], as in which [ʍɪtʃ]. In most dialects, it has merged with w /w/, so that which and witch /ˈwɪtʃ/ are pronounced in the same way (wine–whine merger).

- The voiceless velar fricative /x/ is sometimes used in loanwords from other languages, such as Scottish Gaelic loch, Yiddish chutzpah, German Bach.

Vowels

The pronunciation of vowels varies a great deal between dialects. The table below lists the vowel phonemes in Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA), with examples of words in which they occur (lexical sets). The vowels are represented with symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet; those given for RP are standard in British dictionaries and other publications.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vowel length varies between dialects and between words. RP has long vowels, marked with a triangular colon ⟨ː⟩, but in GA they are typically shortened. Some RP long vowels develop from elision of /r/. In both RP and GA, vowels are longer before voiced consonants than before voiceless consonants: thus, the vowel of need [ˈniːd] is longer than the vowel of neat [nit]. Note that this rule applies exclusively within the same syllable; when a vowel ends an open syllable, it is always long, as in knee and seashore [ˈniː ˈsiː.ʃɔː].

The vowels /ɨ ə/ only occur in unstressed syllables and are a result of vowel reduction. Some dialects do not distinguish them, so that roses and comma end in the same vowel (weak vowel merger). GA has an unstressed r-colored schwa /ɚ/, as in butter [ˈbʌtɚ], which in RP has the same vowel as comma.

The pronunciation of some vowels varies between dialects:

- In conservative RP and in GA, the vowel of back is a near-open [æ], but in modern RP and some North American dialects it is open [a]. The vowel of words like bath is /æ/ in GA, but /ɑː/ in RP (trap–bath split). In some dialects, /æ/ sometimes or always changes to a long vowel or diphthong, like [æː] or [eə] (bad–lad split and [[Phonological history of English short A#/æ/ tensing|/æ/ tensing]]): thus man /mæn/ is pronounced with a diphthong like [meən] in many North American dialects.

- The RP vowel /ɒ/ is pronounced /ɑ/ (father–bother merger) or /ɔ/ (lot–cloth split) in GA. Thus box is RP /bɒks/ but GA /bɑks/, while cloth is RP /klɒθ/ but GA /klɔθ/. Some North American dialects merge /ɔ/ with /ɑ/, except before /r/ (cot–caught merger).

- In Scottish, Irish and Northern English, and in some dialects of North American English, the diphthongs /eɪ/ and /əʊ/ (/oʊ/) are pronounced as monophthongs (monophthongization). Thus, day and no are pronounced as /ˈdeɪ ˈnəʊ/ in RP, but as [ˈdeː ˈnoː] or [ˈde ˈno] in other dialects.

- In North American English, the diphthongs /aɪ aʊ/ sometimes undergo a vowel shift called Canadian raising. This sound change affects the first element of the diphthong, and raises it from open [a], similar to the vowel of bra, to near-open [ʌ], similar to the vowel of but. Thus ice and out [ˈʌɪs ˈʌʊt] are pronounced with different vowels from eyes and loud [ˈaɪz ˈlaʊd]. Raising of /aɪ/ sometimes occurs in GA, but raising of /aʊ/ mainly occurs in Canadian English.

GA and RP vary in their pronunciation of historical /r/ after a vowel at the end of a syllable (in the syllable coda). GA is a rhotic dialect, meaning that it pronounces /r/ at the end of a syllable, but RP is non-rhotic, meaning that it loses /r/ in that position. English dialects are classified as rhotic or non-rhotic depending on whether they elide /r/ like RP or keep it like GA.[68]

In GA, the combination of a vowel and the letter ⟨r⟩ is pronounced as an r-coloured vowel in nurse and butter [ˈnɝs ˈbʌtɚ], and as a vowel and an approximant in car and four [ˈkɑɹ ˈfɔɹ].

In RP, the combination of a vowel and ⟨r⟩ at the end of a syllable is pronounced in various different ways. When stressed, it was once pronounced as a centering diphthong ending in [ə], a sound change known as breaking or diphthongization, but nowadays is usually pronounced as a long vowel (compensatory lengthening). Thus nurse, car, four [ˈnɜːs ˈkɑː ˈfɔː] have long vowels, and car and four have the same vowels as bath and paw [ˈbɑːθ ˈpɔː]. An unstressed ⟨er⟩ is pronounced as a schwa, so that butter ends in the same vowel as comma: [ˈbʌtə ˈkɒmə].

Many vowel shifts only affect [[English-language vowel changes before historic /r/|vowels before historical /r/]], and in most cases they reduce the number of vowels that are distinguished before /r/:

- Several historically distinct vowels are reduced to /ɜ/ before /r/. In Scottish English, fern, fir, and fur [fɛrn fɪr fʌr] are pronounced differently and have the same vowels as bed, bid, and but, but in GA and RP they are all pronounced with the vowel of bird: /ˈfɝn ˈfɝ/, /ˈfɜːn ˈfɜː/ (fern–fir–fur merger). Similarly, the vowels of hurry and furry /ˈhʌri ˈfɜri/, cure and fir /ˈkjuːr ˈfɜr/ were historically distinct and are still distinct in RP, but are often merged in GA (hurry–furry and cure–fir mergers).

- Some sets of tense and lax or long and short vowels merge before /r/. Historically, nearer and mirror /ˈniːrər ˈmɪrər/; Mary, marry, and merry /ˈmɛɪɹi ˈmæri ˈmɛri/; hoarse and horse /ˈhoːrs ˈhɔrs/ were pronounced differently and had the same vowels as need and bid; bay, back, and bed; road and paw, but in some dialects their vowels have merged and are pronounced in the same way (mirror–nearer, Mary–marry–merry, and horse–hoarse mergers).

- In traditional GA and RP, poor /pʊr/ or /pʊə/ is pronounced differently from pour /pɔr/ or /pɔə/ and has the same vowel as good, but for many speakers in North America and southern England, poor is pronounced with the same vowel as pour (poor–pour merger).

Stress, rhythm and intonation

English is a strongly stressed language. Certain syllables are stressed, while others are unstressed. Stress is a combination of duration, intensity, vowel quality, and sometimes changes in pitch. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer and louder than unstressed syllables, and vowels in unstressed syllables are frequently reduced while vowels in stressed syllables are not. Many words have one syllable that is stressed (word stress or lexical stress), and words used in a phrase or sentence may receive additional stress (sentence stress or prosodic stress).

In content words of any number of syllables, as well as function words of more than one syllable, there will be at least one syllable with lexical stress. The word "civilisation" has primary stress on the fourth syllable, and most dictionaries indicate that the first syllable has secondary stress and the other syllables are unstressed.[69] The position of stress in English words is not predictable.

Stress in English is phonemic, and some pairs of words are distinguished by stress. For instance, the word contract is stressed on the first syllable when used as a noun, but on the last syllable for most meanings when used as a verb.[70] Here stress is connected to vowel reduction: in the noun "contract" the first syllable is stressed and has the unreduced vowel /ɒ/, whereas in the verb "contract" the first syllable is unstressed and its vowel is reduced to /ə/.

English has strong prosodic stress: typically the last stressed syllable of a phrase receives extra emphasis, but this may also occur on words to which a speaker wishes to draw attention. Prosodic stress affects the pronunciation of function words like of, which are pronounced with different vowels depending on whether or not they are stressed within the sentence.

Rhythmically, English is stress-timed, meaning that the amount of time between stressed syllables tends to be equal. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer, but unstressed syllables (syllables between stresses) are shortened. Vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened as well, and vowel shortening causes changes in vowel quality: vowel reduction.

As concerns intonation, the pitch of the voice is used syntactically in English; for example, to convey whether the speaker is certain or uncertain about the polarity: most varieties of English use falling pitch for definite statements, and rising pitch to express uncertainty, as in yes–no questions. There is also a characteristic change of pitch on strongly stressed syllables, particularly on the "nuclear" (most strongly stressed) syllable in a sentence or intonation group. For more details see Template:P/s.

Grammar

Modern English grammar is the result of a process that has gradually led from a typical Indo-European dependent marking pattern based with a rich inflectional morphology and relatively free word order, to a mostly analytic pattern with little inflection, a fairly fixed SVO word order and a complex syntax. Some traits typical of Germanic languages persist in the language, such as the distinction between irregularly inflected strong stems inflected through ablaut (i.e. changing the vowel of the stem, such as in the pairs speak/spoke and foot/feet) and weak stems inflected through affixation (such as love/loved, hand/hands), and vestiges of the case and gender system are found in the pronoun system (he/him, who/whom), and in the inflection of the copula verb to be. Typical for Indo-European languages, English follows accusative morphosyntactic alignment. English distinguishes at least seven major word classes, verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, determiners, prepositions and conjunctions. Some analyses add pronouns as a class separate from nouns, and subdivide conjunctions into subordinators and coordinators, and add the class of interjections.[71] English also has a rich set of auxiliary verbs, such as have and do expressing the categories of mood and aspect. Questions are marked by do-support, wh-movement (fronting of question words beginning with wh-) and word order inversion with some verbs.

The seven word classes are exemplified in this sample sentence:[72]

| The | chairman | of | the | committee | and | the | loquacious | politician | clashed | violently | when | the | meeting | started |

| Det. | Noun | Prep. | Det. | Noun | Conj. | Det. | Adj. | Noun | Verb | Advb. | Conj. | Det. | Noun | Verb |

Nouns and Noun Phrases

English nouns are only inflected for number and possession. New nouns can be formed through derivation or compounding. They are semantically divided into proper nouns (names) and common nouns. Common nouns are in turn divided into concrete and abstract nouns, and grammatically into count nouns and mass nouns.[73]

Most count nouns are inflected for plural number through the use of the plural suffix -s, but a number of strong nouns have irregular plural forms. Mass nouns can only be pluralized through the use of a count noun classifier, e.g. one loaf of bread, two loaves of bread.[74]

Regular Plural formation:

- Singular: cat, dog

- Plural: cats, dogs

Irregular plural formation:

- Singular: man, woman, foot, fish, ox, knife, mouse

- Plural: men, women, feet, fish, oxen, knives, mice

Possession can be expressed either with the possessive enclitic -s (also traditionally called a genitive suffix), or with the use of the preposition of. Traditionally the -s possessive has been used for animate nouns whereas the of possessive has been reserved for inanimate nouns. Today this distinction is less clear, and many speakers use -s also with inanimates. Orthographically the possessive -s is separated from the noun root with an apostrophe.

Possessive constructions:

- With -s: The woman's husband's child

- With of: The child of the husband of the woman

Nouns can form noun phrases (NPs) where they are the syntactic head of the words that depend on them such as determiners, quantifiers, conjunctions or adjectives.[75] Noun phrases can be short, such as the man composed only of a determiner and a noun, or highly complex such as the tall man with the long red trousers and his skinny wife with the spectacles. Regardless of length an NP functions as a syntactic unit. For example the possessive enclitic follows the entire noun phrase, as in The President of India's wife, where the enclitic follows India and not President.

The class of determiners are used to specify the noun they precede in terms of definiteness where the marks a definite noun and a or an an indefinite one. A definite known is assumed by the speaker to be already known by the interlocutor, whereas an indefinite noun is not specified as being previously known. Quantifiers, a subclass of determiners, such as one, many, some and all are used to specify the noun in terms of quantity or number. The noun must agree with the number of the determiner, e.g. one man (sg.) but all men (pl.). Determiners are the first constituents in a noun phrase.[76]

Adjectives are used to modify a noun, by providing additional information about their referents. Adjectives generally precede the noun they modify and follow any determiners.[77] Adjectives in English do not agree with the noun they modify and are not inflected. E.g. in the phrases the slender boy, and many slender girls the adjective slender does not change to agree with either the number or gender of the noun, as it would in many other Indo-European languages.

Pronouns, Case and Person

English pronouns conserve many traits of case and gender inflection. The personal pronouns retain a difference between subjective and objective case in most persons (I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them) as well as a gender and animacy distinction in the third person singular (distinguishing he/she/it). The subjective case corresponds to the previous Old English nominative case, and the objective case is used both in the sense of the previous accusative case (in the role of patient, or direct object of a transitive verb), and in the sense of the previous dative case (in the role of a recipient or indirect object of a transitive verb).[78][79] Subjective case is used when the pronoun is the subject of a finite clause, and otherwise the objective case is used.[80] While already grammarians such as Henry Sweet[81] and Otto Jespersen[82] noted that the English cases did not correspond to the traditional Latin based system, some contemporary grammars, for example Huddleston & Pullum (2002) harvcoltxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFHuddlestonPullum2002 (help), retain traditional labels for the cases, calling them nominative and accusative cases respectively.

Possessive pronouns exist in dependent and independent forms, the dependent one functions as a determiner specifying a noun (as in my chair), whereas the independent form can stand alone as if it were a noun (e.g. the chair is mine). [83] The English system of grammatical person no longer has a distinction between formal and informal pronouns of address, and the forms for 2nd person plural and singular are identical except in the reflexive form. Some dialects have introduced nnovative 2nd person plural pronouns such as y'all found in Southern American English and African American Vernacular English or youse and ye found in Irish English.

| Personal pronouns | Subjective case | Objective case | Dependent possessive | Independent possessive | Reflexive | |

| 1st p. sg. | I | me | my | mine | myself | |

| 2nd o. sg. | you | you | your | yours | yourself | |

| 3rd p. sg. | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/its | his/hers/its | himself/herself/itself | |

| 1st p. pl. | we | us | our | ours | ourselves | |

| 2nd p. pl. | you | you | your | yours | yourselves | |

| 3rd p. pl | they | them | their | theirs | themselves |

Pronouns are used to refer to entities deictically or anaphorically. A deictic pronoun points to some person or object by identifying it relative to the speech situation - for example the pronoun I identifies the speaker, and the pronoun you, the addressee. Anaphorical pronouns such as that refer back to an entity already mentioned or assumed by the speaker to be known by the audience, for example in the sentences I already told you that, or I told Mike I don't want to see him here anymore. The reflexive pronouns are used when the oblique argument is identical to the subject of a phrase (e.g. he sent it to himsef, or she braced herself).[84]

Prepositions and prepositional phrases

Verbs and verb phrases

English verbs are inflected for tense and aspect, and marked for agreement with third person singular subject. Only the copula verb to be is still inflected for agreement with the plural and first and second person subjects. Auxiliary verbs such as have and be are paired with verbs in the infinitive, past, or progressive forms, form complex tenses, aspects and moods. Auxiliary verbs differ from other verbs in that they can be followed by the negation, and in that they can occur as the first constituent in a question sentence.[85]

Most verbs have six inflectional forms. The primary forms are a plain present, a third person singular present, and a preterit (past) form. And the secondary forms are a plain form used for the infinitive, a gerund–participle and a past participle.[86]

| Inflection | Strong | Regular |

| Plain present | take | love |

| 3rd person sg. present |

takes | loves |

| Preterit | took | loved |

| Plain (infinitive) | take | love |

| Gerund–participle | taking | loving |

| Past participle | taken | loved |

Tense, Aspect and Mood

English has two primary tenses, past (preterit) and non-past. The preterit is inflected by using the preterit form of the verb, which for the regular verbs includes the suffix -ed, and for the strong verbs either the suffix -t or a change in the stem vowel. The past form is unmarked except in the third person singular, which takes the suffix -s.[85]

| Present | Preterite | |

| First person | I run | I ran |

| Third person | John runs | John ran |

English does not have a grammaticalised future tense. Futurity of action is expressed periphrastically with one of the auxiliary verbs will or shall.[87] Traditionally will was used for the first person and shall for all others, but shall has fallen out of use in this function in most varieties.

| Future | |

| First person | I will run |

| Third person | John will run |

Further aspectual distinctions are encoded by the use of auxiliary verbs, primarily have and be, which encode the contrast between a perfect and non-perfect past tense (I have run vs. I was running), and compound tenses such as preterite perfect (I had been running) and present perfect (I have been running).[88]

For the expression of mood, English uses a number of modal auxiliaries, such as can, may, will, shall and the past tense forms could, might, would, should. There is also a subjunctive and an imperative mood, both based on the plain form of the verb (i.e. without the third person singular -s), and which is used in subordinate clauses (e.g. subjunctive: It is important that he run every day; imperative Run!).[87]

"to be"

The copula verb to be retains some of its original conjugation, and takes different inflectional forms depending on the subject.

| Present | Preterite | |

| 1st person sg. | I am | I was |

| 2nd person sg. | you are | you were |

| 3rd person sg. | he/she/it is | he/she/it was |

| 1st person pl. | we are | we were |

| 2nd person pl. | You are | you were |

| 3rd person pl. | they are | they were |

Its past participle is been and its gerund-patriciple is being.

The verb also has the additional peculiarity that in the present tense it can function as an enclitic attaching in an abbreviated form to a preceding noun, pronoun. The clitic forms are -'m (as in I'm a woman), -'re (as in you're a friend or those pants're awesome or no, they're ridiculous) and -'s (as in it's a deal! or that guy's a drag). In writing the clitics are separated from their host with an apostrophe, and they are often considered informal or colloquial, particularly when attached to nouns.

Syntax

The language is moderately analytic.[89] It has developed features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning. Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive voice and progressive aspect. English word order has moved from the Germanic verb-second (V2) word order to being almost exclusively subject–verb–object (SVO). The combination of SVO order and use of auxiliary verbs often creates clusters of two or more verbs at the centre of the sentence, such as he had hoped to try to open it. There is, however, an argument that English is technically a mixed word order language; it still has many uses of V2 word order and SVO word order in which V2 or SVO is used exclusively for the sentence's word order or both are combined in the same sentence but in different clauses.[90]

Modern English use and relics of V2 word order

Examples of Modern English V2 word order: sentences beginning with "Here is," "There is," "Here comes," "There goes," and related expressions, as well as in a few relic sentences such as "Over went the boat", "Pop Goes The Weasel", the palindrome "Able was I ere I saw Elba" or "Boom goes the dynamite", and in most if not all (if not an absolute) of the Five Ws and one H questions (e.g. "What has happened here?", "Who was here today?", "Where will we go?", "When did he go to the stadium?", "Why would this happen to us now?", and "How could these things get here?").

- Examples of exclusive V2 word order in Modern English

Declarative Sentence

Adverbial interrogative sentenceSubject

Interrogative phraseFinite verb

Finite verbNon-finite verb

SubjectObject

Non-finite verb-

AdverbialDeclarative Sentence a. We can move that house. 1 2 3 4 5 Adverbial interrogative sentence b. How quickly should these things get here?

- Both V2 and SVO word orders in the same sentence in Modern English

There are also several patterns in which both V2 and SVO word orders are present within the same sentence.main clause in V2

embedded clause in SVOSubject

ConjunctionFinite verb

Prepositional phraseAdverbial

SubjectNon-finite verb

Finite verbObject

Objectmain clause in V2 a. We will swiftly plant your trees 1 2 3 4 5 embedded clause in SVO b. while, from Spain and Germany, you get more.

English has other patterns of V2 in common use and in poetry.

Do and do-support

The verb do can be used as an auxiliary even in simple declarative sentences, where it usually serves to add emphasis, as in "I did shut the fridge." However in the negated and inverted clauses referred to above, it is used because the rules of English syntax permit these constructions only when an auxiliary is present. It is not allowable (in Modern English) to add the negating word not to an ordinary finite lexical verb, as in *I know not – it can only be added to an auxiliary (or copular) verb, hence if there is no other auxiliary present when negation is required, the auxiliary do is used, to produce a form like I do not (don't) know. The same applies in clauses requiring inversion, including most questions – inversion must involve the subject and an auxiliary verb, so it is not possible to say *Know you him?; grammatical rules require Do you know him?

Negation

Negation is done with the particle not, which precedes the main verb and follows an auxiliary verb. A contracted form of not -n't can used as an enclitic attaching to auxiliary verbs an the to copula verb to be.

Vocabulary

English vocabulary or lexis has changed considerably over the centuries.[91]

Register effects

It is well-established[92] that informal speech registers tend to be made up predominantly of words of Anglo-Saxon or Germanic origin, whereas the proportion of the vocabulary that is of Latinate origins is likely to be higher in legal, scientific, and otherwise scholarly or academic texts.

Child-directed speech, which is an informal speech register, also tends to rely heavily on vocabulary rife in words derived from Anglo-Saxon. The speech of mothers to young children has a higher percentage of native Anglo-Saxon verb tokens than speech addressed to adults.[93] In particular, in parents' child-directed speech the clausal core [94] is built in the most part by Anglo-Saxon verbs, namely, almost all tokens of the grammatical relations subject-verb, verb-direct object and verb-indirect object that young children are presented with, are constructed with native verbs.[95] The Anglo-Saxon verb vocabulary consists of short verbs, but its grammar is relatively complex. Syntactic patterns specific to this sub-vocabulary in present-day English include periphrastic constructions for tense, aspect, questioning and negation, and phrasal lexemes functioning as complex predicates, all of which also occur in child-directed speech.

The historical origin of vocabulary items affects the order of acquisition of various aspects of language development in English-speaking children. Latinate vocabulary is in general a later acquisition in children than the native Anglo-Saxon one.[96][97] Young children almost exclusively use the native verb vocabulary in constructing basic grammatical relations, apparently mastering its analytic aspects at an early stage.[95]

Number of words in English

The vocabulary of English is undoubtedly very large, but assigning a specific number to its size is more a matter of definition than of calculation – and there is no official source to define accepted English words and spellings in the way that the French Académie française and similar bodies do for other languages.

Archaic, dialectal, and regional words might or might not be widely considered as "English", and neologisms are continually coined in medicine, science, technology and other fields, along with new slang and adopted foreign words. Some of these new words enter wide usage while others remain restricted to small circles.

The General Explanations at the beginning of the Oxford English Dictionary states:

The Vocabulary of a widely diffused and highly cultivated living language is not a fixed quantity circumscribed by definite limits... there is absolutely no defining line in any direction: the circle of the English language has a well-defined centre but no discernible circumference.

The current FAQ for the OED further states:

How many words are there in the English language? There is no single sensible answer to this question. It's impossible to count the number of words in a language, because it's so hard to decide what actually counts as a word.[98]

The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (OED2) includes over 600,000 definitions, following a rather inclusive policy:

It embraces not only the standard language of literature and conversation, whether current at the moment, or obsolete, or archaic, but also the main technical vocabulary, and a large measure of dialectal usage and slang (Supplement to the OED, 1933).[99]

The editors of Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged include 475,000 main headwords, but in their preface they estimate the true number to be much higher. Comparisons of the vocabulary size of English to that of other languages are generally not taken very seriously by linguists and lexicographers. Besides the fact that dictionaries will vary in their policies for including and counting entries,[100] what is meant by a given language and what counts as a word do not have simple definitions. Also, a definition of word that works for one language may not work well in another,[101] with differences in morphology and orthography making cross-linguistic definitions and word-counting difficult, and potentially giving very different results.[102] Linguist Geoffrey K. Pullum has gone so far as to compare concerns over vocabulary size (and the notion that a supposedly larger lexicon leads to "greater richness and precision") to an obsession with penis length.[103]

In December 2010 a joint Harvard/Google study found the language to contain 1,022,000 words and to expand at the rate of 8,500 words per year.[104] The findings came from a computer analysis of 5,195,769 digitised books. Others have estimated a rate of growth of 25,000 words each year.[105]

Word origins

One of the consequences of the French influence is that the vocabulary of English is, to a certain extent, divided between those words that are Germanic (mostly West Germanic, with a smaller influence from the North Germanic branch) and those that are "Latinate" (derived directly from Latin, or through Norman French or other Romance languages).[106] The situation is further compounded, as French, particularly Old French and Anglo-French, were also contributors in English of significant numbers of Germanic words, mostly from the Frankish and Old Norse elements in French (see List of English Latinates of Germanic origin).

The majority (estimates range from roughly 50%[107] to more than 80%[108]) of the thousand most common English words are Germanic. However, the majority of more advanced words in subjects such as the sciences, philosophy and mathematics come from Latin or Greek.

| 1st 100 | 1st 1,000 | 2nd 1,000 | Subsequent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germanic | 97% | 57% | 39% | 36% |

| Italic | 3% | 36% | 51% | 51% |

| Hellenic | 0 | 4% | 4% | 7% |

| Others | 0 | 3% | 6% | 6% |

| Source: Nation 2001, p. 265 | ||||

Numerous sets of statistics have been proposed to demonstrate the proportionate origins of English vocabulary. None, as yet, is considered definitive by most linguists.

A computerised survey of about 80,000 words in the old Shorter Oxford Dictionary (3rd ed.) was published in Ordered Profusion by Thomas Finkenstaedt and Dieter Wolff (1973)[109] that estimated the origin of English words as follows:

- Langues d'oïl, including French and Old Norman: 28.3%

- Latin, including modern scientific and technical Latin: 28.24%

- Germanic languages (including words directly inherited from Old English; does not include Germanic words coming from the Germanic element in French, Latin or other Romance languages): 25%

- Greek: 5.32%

- No etymology given: 4.03%

- Derived from proper names: 3.28%

- All other languages: less than 1%

A survey by Joseph M. Williams in Origins of the English Language of 10,000 words taken from several thousand business letters gave this set of statistics:[110]

- French (langue d'oïl): 41%

- "Native" English: 33%

- Latin: 15%

- Old Norse: 2%

- Dutch: 1%

- Other: 10%

Writing system

Since around the 9th century, English has been written in the Latin script, which replaced Anglo-Saxon runes. The modern English alphabet contains 26 letters of the Latin script: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z (which also have majuscule, capital or uppercase forms: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z). Other symbols used in writing English include the ligatures, æ and œ (though these are no longer common). There is also some usage of diacritics, mainly in foreign loanwords (like the acute accent in café and exposé), and in the occasional use of a diaeresis to indicate that two vowels are pronounced separately (as in naïve, Zoë). For more information see English terms with diacritical marks.

The spelling system, or orthography, of English is multilayered, with elements of French, Latin and Greek spelling on top of the native Germanic system; further complications have arisen through sound changes with which the orthography has not kept pace. This means that, compared with many other languages, English spelling is not a reliable indicator of pronunciation and vice versa (it is not, generally speaking, a phonemic orthography).

Though letters and sounds may not correspond in isolation, spelling rules that take into account syllable structure, phonetics, and accents are 75% or more reliable.[111] Some phonics spelling advocates claim that English is more than 80% phonetic.[112] However, English has fewer consistent relationships between sounds and letters than many other languages; for example, the letter sequence ough can be pronounced in 10 different ways. The consequence of this complex orthographic history is that reading can be challenging.[113] It takes longer for students to become completely fluent readers of English than of many other languages, including French, Greek, and Spanish.[114] English-speaking children have been found to take up to two years longer to learn to read than children in 12 other European countries.[115]

As regards the consonants, the correspondence between spelling and pronunciation is fairly regular. The letters b, d, f, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, z represent, respectively, the phonemes /b/, /d/, /f/, /h/, /dʒ/, /k/, /l/, /m/, /n/, /p/, /r/, /s/, /t/, /v/, /w/, /z/ (as tabulated in the Template:P/s section above). The letters c and g normally represent /k/ and /ɡ/, but there is also a soft c pronounced /s/, and a soft g pronounced /dʒ/. Some sounds are represented by digraphs: ch for /tʃ/, sh for /ʃ/, th for /θ/ or /ð/, ng for /ŋ/ (also ph is pronounced /f/ in Greek-derived words). Doubled consonant letters (and the combination ck) are generally pronounced as single consonants, and qu and x are pronounced as the sequences /kw/ and /ks/. The letter y, when used as a consonant, represents /j/. However this set of rules is not applicable without exception; many words have silent consonants or other cases of irregular pronunciation.

With the vowels, however, correspondences between spelling and pronunciation are even more irregular. As can be seen under Template:P/s above, there are many more vowel phonemes in English than there are vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u, y). This means that diphthongs and other long vowels often need to be indicated by combinations of letters (like the oa in boat and the ay in stay), or using a silent e or similar device (as in note and cake). Even these devices are not used consistently, so consequently vowel pronunciation remains the main source of irregularity in English orthography.

Formal written English

A version of the language almost universally agreed upon by educated English-speakers around the world is called formal written English. It takes virtually the same form regardless of where it is written, in contrast to spoken English, which differs significantly between dialects, accents, and varieties of slang and of colloquial and regional expressions. Local variations in the formal written version of the language are quite limited, being restricted largely to minor spelling, lexical and grammatical differences between different national varieties of English (e.g. British, American, Indian, Australian, South African, etc.).

Dialects, accents, and varieties

English has never been a homogeneous language, but has had a considerable degree of internal dialectal variation since its origins in the Anglo-Saxon dialects. Today some dialectal variation goes back to this original variation, but considerable local and regional innovation has accumulated since then creating an even more varied picture. Additionally the global spread of English has put the English language into contact with many other languages worldwide, whose influences contribute to the creation of new varieties of English, such as English based creole languages and pidgins, and the so-called World Englishes.

Dialectologists distinguish between English dialects, regional varieties that differ from each other in terms of grammar and vocabulary, and regional accents, distinguished by different patterns of pronunciation. The major native dialects of English are often divided by linguists into the two general categories of the British Isles dialects (BrE) and those of North America (AmE).[41][116]

English is a pluricentric language,[35] without a central language authority like France's Académie française; and therefore no one variety is considered universally "correct" or "incorrect" except in terms of the norms and expectations of the particular audience to which the language is directed. English-speakers have many different accents, which often signal the speaker's native dialect or language. For the most distinctive characteristics of regional accents, see regional accents of English, and for a complete list of regional dialects, see list of dialects of the English language.

England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland

As the place where English evolved, the British Isles, and particularly England, is home to the most variegated pattern of dialects. In Britain, one may still find traces of the original variation brought to England by the Anglo-Saxons.

Within the United Kingdom, the Received Pronunciation (RP), an educated dialect of South East England, is used as the broadcast standard, and is considered the most prestigious of the British dialects. The spread of RP (also known as BBC English) through the media, has caused many traditional dialects of rural England to recede, as youths adopt the traits of the prestige variety instead of traits from local dialects. At the time of the Survey of English Dialects, grammar and vocabulary differed across the country, but a process of lexical attrition has led most of this variation to disappear.[117] Nonetheless this attrition has mostly affected dialectal variation in grammar and vocabulary, and in fact only 3% of the English population actually speak RP, the remainder speaking regional accents and dialects with varying degrees of RP influence. There is also variability within RP, particularly along class lines between Upper and Middle class RP speakers and between native RP speakers and speakers who adopt RP later in life. Within Britain there is also considerable variation along lines of social class, and some traits though exceedingly common are considered "non-standard" and are associated with lower class speakers and identities. An example of this is aitch-dropping, which historically was a feature of lower class London English, particularly Cockney, but which today is the standard in all major English cities - yet it remains largely absent in broadcasting and among the upper crust of British society.

Modern English can be divided in to five major dialect regions, Southwest English, South East English, West and East Midlands English and Northern English. Within each of these regions several local subdialects exist: Within the Northern region, there is a division between the Yorkshire dialects, and the Geordie dialect spoken in Northumbria around Newcastle, and the Lancashire dialects with local urban dialects in Liverpool (Scouse) and Manchester (Mancunian). Having been the center of Danish occupation during the Viking Invasions, Northern English dialects, particularly the Yorkshire dialect, retain Norse features not found in other English varieties. Northern dialects traditionally differed from the southern ones in their retention of postvocalic R (a trait known as rhoticity), but through influence from RP most Northern dialects are no longer rhotic; Many of them also have different vowel qualities from RP, most prominently they tend to lack the vowel /ʌ/, instead having ʊ, for example in the word "strut". Northern dialects were also affected differently by the Great Vowel Shift, so that they tend to have monophthongs corresponding to some or all of the RP diphthongs, for example in the Yorkshire pronunciation of now [naʊ] as noo [nuː]. In terms of grammar some Northern dialects distinguish grammatically between this, that and yon, and allow grammatical constructions with double negation, not found in southern dialects. They also traditionally had a grammatical rule called the "Northern subject rule", according to which the verb only agrees with a plural subject if the plural pronoun immediately preceded the verb, for example they sing, but the birds sings.[118]

Since the 15th century, Southeastern varieties centered around London, has been the center from which dialectal innovations have spread to other dialects. In London, the Cockney dialect was traditionally used by the lower classes, and it was long a socially stigmatized variety. Today a large area of Southeastern England has adopted traits from Cockney, resulting in the so-called Estuary English which spread in areas south and East of London beginning in the 1980s. Estuary English is distinguished by traits such as the use of intrusive R (drawing is pronounced drawring /ˈdrɔːrɪŋ/), t-glottalisation (Potter is pronounced with a glottal stop as Po'er /poʔʌ/), and the pronunciation of th- as /f/ (thanks pronounced fanks) or /v/ (bother" pronounced bover). Many accents of the West country (Cornwall, Devon and Somerset), retain rhoticity, and some also have a system of pronoun enclitics, where reduced subject forms are suffixed to the verb when the pronoun is not stressed. For example the weak form of you is ee, and us is the weak form of we, giving sentences such as you wouldn't do that would ee? and We wouldn't want that would us?[118]

Scots, is today considered a separate language from English, but it has its origins in early Northern Middle English[119] and developed and changed during its history with influence from other sources. However, following the Acts of Union 1707 a process of language attrition began, whereby successive generations adopted more and more features from Standard English. Whether Scots is now a separate language or is better described as a dialect of English (i.e. part of Scottish English) remains in dispute, although the UK government accepts Scots as a regional language and has recognised it as such under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[120] Scots itself has a number of regional dialects: pronunciation, grammar and lexis of the traditional forms differ, sometimes substantially, from other varieties of English.[121]

In Ireland the Hiberno-English varieties of English go back to the Norman Invasions of the 11th century. In Wexford, in the area surrounding Dublin two highly conservative dialects were spoken until the 19th century, they had developed independently from Early Middle English. Today Irish English is divided into Ulster English, a dialect with strong influence from Scots, and southern Hiberno-English. Like Scots and Northern English, the Irish accents preserve the rhoticity which has been lost in most dialects influenced by RP.[9][122]

North America

Even before the independence of the USA, American English was highly homogeneous. Early American authors commented on the lack of significant linguistic variation across the colonized area of the Eastern seaboard. Today there is more variation, yet two thirds of Americans speak a broad dialect known as General American (GA), although as with RP in Britain there are different accents also within it. Separate from GA is Southern American English (SAE), widely spoken in the Southern states, and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) spoken by African Americans in most major cities. Some dialectologists also recognize midlands and western dialects of American English. Canadian English, except for the maritime East Coast varieties, is mostly similar to GA, but has some distinct traits, as well as distinct norms for written and formal language.[123] [124][125]

General American is a rhotic accent, and the social distribution of rhoticity in the US is the opposite of what it is in Britain where rhoticity is the socially marked accent. Rather, in the US, non-rhotic accents are marked, and often associated with lower prestige, and lower social class. In a groundbreaking study published in 1972 socio-linguist William Labov demonstrated this in the context of New York, by showing that rhoticity was used more frequently by employees in upscale department stores than in stores catering to middle and lower class groups, where the non-rhotic local New York accent was more frequent.[126] Within GA there is regional variety both in terms of vocabulary (e.g. the use of pop as opposed to soda is regionally determined[127]) and phonology, with identifiable local varieties in many regions. The accents North Eastern US cities are undergoing a chain shift dubbed the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which is rearranging the vowel qualities of those varieties (for example resulting in the fronting of short /a/ in cat to sound like [kʲɛt], and the lowering of /ɔ/ causing the cot–caught merger).

Southern American English is also generally non-rhotic, although class and gender based differences in the degree of rhoticity also apply.[128][129] The Southern Accent is often colloquially described as a "drawl" or "twang".[130] In addition to its rhoticity, SAE is characterized by a series of vowel changes, the merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ before nasals (the pin–pen merger), the monophthongization of some diphthongs, and sometimes creation of triphthongs by the breaking of a single front vowel into two syllables with an intervening glide e.g. in the word "dress" pronounced as [dɽeiəs].[131] Grammatical traits of SAE include the use of done as a past tense auxiliary (e.g. I done told you), the use of y'all as a second person plural pronoun, and the use of double modal verbs (e.g. I might could do it). Traditionally Southern American English has been considered to have arisen as a result of the settlement history of the southern states, however more recent research has suggested that many of the distinctive southern features did not become widespread until the 19th century.[132]

African American Vernacular English is also a non-rhotic accent, and some linguists ascribe this and other defining traits of the variety, to its origins among enslaved Africans in the American South where non-rhotic English was spoken. Others however ascribe the distinguishing traits to substrate influence from different African languages spoken by the slaves who had to use Creole English as a lingua franca between slaves of different ethnic origins.[133] After abolition most African Americans settled in the inner cities of the North and here African American English developed to a highly coherent and homogeneous variety. It has often been stigmatized simply as a form of "broken" or "uneducated" English, but today linguists recognize it as a fully developed variety of English with its own norms shared by a large speech community. Some traits of AAVE seem to be spreading to GA, perhaps due to the significant influence of African American culture on wider American youth culture. AAVE displays significant differences from GA and SAE both in vocabulary, pronunciation (e.g. changing initial /ð/ to [d], so that this is pronounced dis), and grammar (e.g. the use of double negatives, and a complex aspectual systems with constructions such as I'm afly it vs. I be flyin it vs. I done fly it).[134]

Australia and New Zealand