Canadians: Difference between revisions

Zakeria12345 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 509: | Line 509: | ||

|caption = Religion in Canada (2011 census)<ref name="census2011" /> |

|caption = Religion in Canada (2011 census)<ref name="census2011" /> |

||

|label1 = [[Religion in Canada#History|Christianity]] |

|label1 = [[Religion in Canada#History|Christianity]] |

||

|value1 = |

|value1 = 80.3 |

||

|color1 = DodgerBlue |

|color1 = DodgerBlue |

||

|label2 = [[Irreligion in Canada|Non-religious]] |

|label2 = [[Irreligion in Canada|Non-religious]] |

||

|value2 = |

|value2 = 9.4 |

||

|color2 = Gray |

|color2 = Gray |

||

|label3 = [[Islam in Canada|Islam]] |

|label3 = [[Islam in Canada|Islam]] |

||

|value3 = |

|value3 = 4.2 |

||

|color3 = MediumSeaGreen |

|color3 = MediumSeaGreen |

||

|label4 = [[Hinduism in Canada|Hinduism]] |

|label4 = [[Hinduism in Canada|Hinduism]] |

||

| Line 527: | Line 527: | ||

|color6 = Gold |

|color6 = Gold |

||

|label7 = [[Judaism in Canada|Judaism]] |

|label7 = [[Judaism in Canada|Judaism]] |

||

|value7 = 1. |

|value7 = 1.5 |

||

|color7 = Turquoise |

|color7 = Turquoise |

||

|label8 = Other religions |

|label8 = Other religions |

||

Revision as of 00:30, 13 June 2013

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1,003,850[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Hong Kong | 200,000[1] | |||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 72,518[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | 52,500[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Lebanon | 45,000[1] | |||||||||||||||

| People's Republic of China | 20,000[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Australia | 27,289[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Italy | 23,487[1] | |||||||||||||||

| France | 18,913[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Greece | 12,477[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Egypt | 10,000[1] | |||||||||||||||

| South Korea | 8,763[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Mexico | 7,943[2] | |||||||||||||||

| New Zealand | 7,770[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 7,519[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Philippines | 7,500[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 7,326[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Japan | 7,067[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 8,427[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 4,145[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Norway | 2,290[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 4,081[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Spain | 3,810[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 2,752[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 2,742[3] | |||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||

| Canadian English and Canadian French Numerous indigenous American languages are also recognized. | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Christianity (83%) Islam (4%) Judaism (2%) Others (12%) | ||||||||||||||||

Canadians (singular Canadian; French: Canadiens) are the people who are identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical, and/or cultural. For most Canadians, several (frequently all) of those types of connections exist and are the source(s) of them being considered Canadians.

Aboriginal peoples, according to the 2011 Canadian Census, numbered at 1,400,685, 4.3% of the country's total population.[5] The majority of the population is made up of Old World immigrants and their descendants. After the initial period of French and then the much larger British colonization, different waves (or peaks) of immigration and settlement of non-aboriginal peoples took place over the course of nearly two centuries and continues today. Elements of Aboriginal, French, British and more recent immigrant customs, languages and religions have combined to form the culture of Canada and thus a Canadian identity. Canada has also been strongly influenced by that of its linguistic, geographic and economic neighbour, the United States.

Canadian independence from Great Britain grew gradually over the course of many years since the formation of the Canadian Confederation in 1867. World War I and World War II in particular gave rise to a desire amongst Canadians to have their country recognized as a fully-fledged sovereign state with a distinct citizenship. Legislative independence was established with the passage of the Statute of Westminster 1931, the Canadian Citizenship Act of 1946 took effect on January 1, 1947, and full sovereignty was achieved with the patriation of the constitution in 1982. Canada's nationality law closely mirrored that of the United Kingdom. Legislation since the mid 20th century represents Canadians' commitment to multilateralism and socioeconomic development.

History

Aboriginal peoples

Archaeological studies and genetic analyses have indicated a human presence in the northern Yukon region from 24,500 BC, and in southern Ontario from 7500 BC.[6][7][8] The Paleo-Indian archeological sites at Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are two of the oldest sites of human habitation in Canada.[9][10][11] The characteristics of Canadian Aboriginal societies included permanent settlements, agriculture, complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[12][13] Some of these cultures had collapsed by the time European explorers arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, and have only been discovered through archeological investigations.[14]

The aboriginal population is estimated to have been between 200,000[15] and two million in the late 15th century,[16] with a figure of 500,000 accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health.[17] As a consequence of the European colonization, Canada's aboriginal peoples suffered from repeated outbreaks of newly introduced infectious diseases such as influenza, measles, and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity), resulting in a forty- to eighty-percent population decrease in the centuries after the European arrival.[15] Aboriginal peoples in present-day Canada include the First Nations,[18] Inuit,[19] and Métis.[20] The Métis are a mixed-blood people who originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations and Inuit people married European settlers.[21] In general, the Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during the colonization period.[22]

European colonization

The first known attempt at European colonization began when Norsemen settled briefly at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland around 1000 AD.[23] No further European exploration occurred until 1497, when Italian seafarer John Cabot explored Canada's Atlantic coast for England.[24] Basque and Portuguese mariners established seasonal whaling and fishing outposts along the Atlantic coast in the early 16th century.[25] In 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier explored the St. Lawrence River, where on July 24 he planted a 10-metre (33 ft) cross bearing the words "Long Live the King of France", and took possession of the territory in the name of King Francis I of France.[26]

In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, as the first North American English colony by the royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I.[27] French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in 1603, and established the first permanent European settlements at Port Royal in 1605 and Quebec City in 1608.[28] Among the French colonists of New France, Canadiens extensively settled the St. Lawrence River valley and Acadians settled the present-day Maritimes, while fur traders and Catholic missionaries explored the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and the Mississippi watershed to Louisiana. The Beaver Wars broke out in the mid-17th century over control of the North American fur trade.[29]

The English established additional colonies in Cupids and Ferryland, Newfoundland, beginning in 1610.[30] The Thirteen Colonies to the south were founded soon after.[25] A series of four wars erupted between 1689 and 1763.[31] Mainland Nova Scotia came under British rule with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht; the Treaty of Paris (1763) ceded Canada and most of New France to Britain after the Seven Years' War.[32]

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 created the Province of Quebec out of New France, and annexed Cape Breton Island to Nova Scotia.[33] St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony in 1769.[34] To avert conflict in Quebec, the British passed the Quebec Act of 1774, expanding Quebec's territory to the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley. It re-established the French language, Catholic faith, and French civil law there. This angered many residents of the Thirteen Colonies, fuelling anti-British sentiment in the years prior to the 1775 outbreak of the American Revolution.[33]

The 1783 Treaty of Paris recognized American independence and ceded territories south of the Great Lakes to the United States.[35] New Brunswick was split from Nova Scotia as part of a reorganization of Loyalist settlements in the Maritimes. To accommodate English-speaking Loyalists in Quebec, the Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the province into French-speaking Lower Canada (later Quebec) and English-speaking Upper Canada (later Ontario), granting each its own elected legislative assembly.[36]

The Canadas were the main front in the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain. Following the war, large-scale immigration to Canada from Britain and Ireland began in 1815.[16] Between 1825 and 1846, 626,628 European immigrants reportedly landed at Canadian ports.[38] Between one-quarter and one-third of all Europeans who immigrated to Canada before 1891 died of infectious diseases.[15]

The desire for responsible government resulted in the abortive Rebellions of 1837. The Durham Report subsequently recommended responsible government and the assimilation of French Canadians into English culture.[33] The Act of Union 1840 merged the Canadas into a united Province of Canada. Responsible government was established for all British North American provinces by 1849.[39] The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending the border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858).[40]

Confederation and expansion

Following several constitutional conferences, the 1867 Constitution Act officially proclaimed Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, initially with four provinces – Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[41][42][43] Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories, where the Métis' grievances ignited the Red River Rebellion and the creation of the province of Manitoba in July 1870.[44] British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had been united in 1866) joined the Confederation in 1871, while Prince Edward Island joined in 1873.[45] Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and his Conservative government established a National Policy of tariffs to protect the nascent Canadian manufacturing industries.[43]

To open the West, the government sponsored the construction of three transcontinental railways (including the Canadian Pacific Railway), opened the prairies to settlement with the Dominion Lands Act, and established the North-West Mounted Police to assert its authority over this territory.[46][47] In 1898, during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, the Canadian government created the Yukon Territory. Under the Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, continental European immigrants settled the prairies, and Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.[45]

Early 20th century

Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the Confederation Act, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps. The Corps played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war.[48] Out of approximately 625,000 Canadians who served in World War I, around 60,000 were killed and another 173,000 were wounded.[49] The Conscription Crisis of 1917 erupted when conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden brought in compulsory military service over the objections of French-speaking Quebecers. In 1919, Canada joined the League of Nations independently of Britain,[48] and the 1931 Statute of Westminster affirmed Canada's independence.[50]

The great depression in Canada during the early 1930s saw an economic downturn, leading to hardship across the country.[51] In response to the downturn, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan introduced many elements of a welfare state (as pioneered by Tommy Douglas) in the 1940s and 1950s.[52] Canada declared war on Germany independently during World War II under Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, three days after Britain. The first Canadian Army units arrived in Britain in December 1939.[48]

Canadian troops played important roles in many key battles of the war, including the failed 1942 Dieppe Raid, the Allied invasion of Italy, the Normandy landings, the Battle of Normandy, and the Battle of the Scheldt in 1944.[48] Canada provided asylum for the Dutch monarchy while that country was occupied, and is credited by the Netherlands for major contributions to its liberation from Nazi Germany.[53] The Canadian economy boomed during the war as its industries manufactured military materiel for Canada, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union.[48] Despite another Conscription Crisis in Quebec in 1944, Canada finished the war with a large army and strong economy.[54]

Modern times

The Dominion of Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) was unified with Canada in 1949.[55] Canada's post-war economic growth, combined with the policies of successive Liberal governments, led to the emergence of a new Canadian identity, marked by the adoption of the current Maple Leaf Flag in 1965,[56] the implementation of official bilingualism (English and French) in 1969,[57] and the institution of official multiculturalism in 1971.[58] Socially democratic programs were also instituted, such as Medicare, the Canada Pension Plan, and Canada Student Loans, though provincial governments, particularly Quebec and Alberta, opposed many of these as incursions into their jurisdictions.[59] Finally, another series of constitutional conferences resulted in the 1982 patriation of Canada's constitution from the United Kingdom, concurrent with the creation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[60] In 1999, Nunavut became Canada's third territory after a series of negotiations with the federal government.[61]

At the same time, Quebec underwent profound social and economic changes through the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, giving birth to a modern nationalist movement. The radical Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) ignited the October Crisis with a series of bombings and kidnappings in 1970,[62] and the sovereignist Parti Québécois was elected in 1976, organizing an unsuccessful referendum on sovereignty-association in 1980. Attempts to accommodate Quebec nationalism constitutionally through the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990.[63] This led to the formation of the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and the invigoration of the Reform Party of Canada in the West.[64][65] A second referendum followed in 1995, in which sovereignty was rejected by a slimmer margin of just 50.6 to 49.4 percent. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that unilateral secession by a province would be unconstitutional, and the Clarity Act was passed by parliament, outlining the terms of a negotiated departure from Confederation.[63]

In addition to the issues of Quebec sovereignty, a number of crises shook Canadian society in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the explosion of Air India Flight 182 in 1985, the largest mass murder in Canadian history;[66] the École Polytechnique massacre in 1989, a university shooting targeting female students;[67] and the Oka Crisis of 1990,[68] the first of a number of violent confrontations between the government and Aboriginal groups.[69] Canada also joined the Gulf War in 1990 as part of a US-led coalition force, and was active in several peacekeeping missions in the 1990s, including the UNPROFOR mission in the former Yugoslavia.[70][71] Canada sent troops to Afghanistan in 2001, but declined to send forces to Iraq when the US invaded in 2003.[72] In 2009, Canada's economy suffered in the worldwide Great Recession, but has since rebounded modestly.[73] In 2011, Canadian forces participated in the NATO-led intervention into the Libyan civil war.[74]

Population

Canadians make up 0.5% of the world's total population,2010[75] having relied upon immigration for population growth and social development.[76]> Approximately 41% of current Canadians are first or second generation immigrants,[77] meaning two out of every five Canadians currently living in Canada were not born in the country.[78]Statistics Canada projects that, by 2031, nearly one-half of Canadians above the age of 15 will be foreign-born or have one foreign-born parent.[79]

Immigration

The French originally settled New France in present-day Quebec and Ontario, during the early part of the 17th century.[80] Approximately 100 Irish-born families would settle the Saint Lawrence Valley by 1700, assimilating into the Canadien population and culture.[81][82] The French also settled the Acadian peninsula alongside a smaller number of other European merchants, who collectively became the Acadians.[83] During the 18th and 19th century; immigration westward (to the area known as Rupert's Land) was carried out by French settlers (Coureur des bois) working for the North West Company, and by British (English and Scottish) settlers representing the Hudson's Bay Company.[84] This led to the creation of the Métis, an ethnic group of mixed European and First Nations parentage.[85]

The British conquest of New France was proceeded by small number of Germans and Swedes who settled alongside the Scottish in Port Royal, Nova Scotia, while some Irish immigrated to the Colony of Newfoundland.[86] In the wake of the 1775 invasion of Canada by the newly formed Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, approximately 60,000 United Empire Loyalist fled to British North America, a large portion of whom migrated to New Brunswick.[87] After the War of 1812, British (included British army regulars), Scottish and Irish immigration was encouraged throughout Rupert's Land, Upper Canada and Lower Canada.[88]

Between 1815 and 1850 some 800,000 immigrants came to the colonies of British North America, mainly from the British Isles as part of the great migration of Canada.[89] These included some Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances to Nova Scotia.[90] The Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s significantly increased the pace of Irish immigration to Prince Edward Island and the Province of Canada, with over 35,000 distressed individuals landing in Toronto in 1847 and 1848.[91][92] Beginning in late 1850s, Chinese immigrants into the Colony of Vancouver Island and Colony of British Columbia peaked with the onset of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.[93] The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 eventually placed a head tax on all Chinese immigrants, in hopes of discouraging Chinese immigration after completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[94]

| Rank | Country | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Philippines | 36,578 | 13 |

| 2 | India | 30,252 | 10.8 |

| 3 | China | 30,197 | 10.8 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 9,499 | 3.4 |

| 5 | United States | 9,243 | 3.3 |

| 6 | France | 6,934 | 2.5 |

| 7 | Iran | 6,815 | 2.4 |

| 8 | United Arab Emirates | 6,796 | 2.4 |

| 9 | Morocco | 5,946 | 2.1 |

| 10 | South Korea | 5,539 | 2 |

| Top 10 Total | 147,799 | 52.7 | |

| Other | 132,882 | 47.3 | |

| Total | 280,681 | 100 |

The population of Canada has consistently risen, doubling approximately every 40 years, since the establishment of the Canadian Confederation in 1867.[96] From the mid to late 19th century Canada had a policy of assisting immigrants from Europe, including an estimated 100,000 unwanted "Home Children" from Britain.[97] Block settlement communities were established throughout western Canada between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some were planned and other were spontaneously created by the settlers themselves.[98] Canada was now receiving a large amount of European immigrants predominately Italians, Germans, Scandinavians, Dutch, Poles, and Ukrainians.[99] Legislative restrictions on immigration (such as the Continuous journey regulation and Chinese Immigration Act) that had favoured British and other European immigrants were amended in the 1960s, opening the doors to immigrants from all parts of the world.[100] While the 1950s had still seen high levels of immigration by Europeans, by the 1970s immigrants increasingly were Chinese, Indian, Vietnamese, Jamaican and Haitian.[101] During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Canada received many American Vietnam War draft dissenters.[102] Throughout the late 1980s and 1990s Canada's growing Pacific trade brought with it a large influx of South Asians, that tended to settle in British Columbia.[103] Immigrants of all backgrounds tend to settle in the major urban centres.[104][105]

The majority of illegal immigrants come from the southern provinces of the People's Republic of China, with Asia as a whole, Eastern Europe, Caribbean, Africa and the Middle East all contributing to the illegal population.[106] Estimates of illegal immigrants range between 35,000 and 120,000.[107] A 2008 report by the Auditor General of Canada Sheila Fraser, stated that Canada has lost track of approximately 41,000 illegal immigrants whose visas have expired.[108]

Citizenship

3 January 1947

Canadian citizenship is typically obtained by birth in Canada, birth abroad when at least one parent is a Canadian citizen, or by adoption abroad by at least one Canadian citizen.[109] It can also be granted to a permanent resident who lives in Canada for three out of four years and meets specific requirements.[109] Canada established its own nationality law in 1946 with the enactment of the Canadian Citizenship Act, which took effect on January 1, 1947.[110] The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, was passed by the Parliament of Canada in 2001 as Bill C-11, which replaced the Immigration Act of 1976 as the primary federal legislation regulating immigration.[111] Prior to the conferring of legal status on Canadian citizenship, Canada's naturalization laws consisted of a multitude of Acts beginning with the Immigration Act of 1910.[112]

According to Citizenship and Immigration Canada there are three main classifications for immigrants: Family class (closely related persons of Canadian residents), Economic class (admitted on the basis of a point system that account for age, health and labour-market skills required for cost effectively inducting the immigrants into Canada's labour market) and Refugee class (those seeking protection by applying to remain in the country by way of the Canadian immigration and refugee law).[113] In 2008, there were 65,567 immigrants in the family class, 21,860 refugees, and 149,072 economic immigrants amongst the 247,243 total immigrants to the country.[77] Canada resettles over one in 10 of the world’s refugees[114] and has one of the highest per-capita immigration rates in the world.[115]

The majority of Canadian citizens live in Canada; however, there are approximately 2,800,000 Canadians abroad as of November 1, 2009.[116] This represents about 7.5% of the total Canadian population. Of those abroad the United States, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, China, and Lebanon have the largest Canadian diaspora. Canadians in United States are the greatest single expatriate community at over 1 million in 2009, representing 35.8% of all Canadians abroad.[117] Under current Canadian law, Canada does not restrict dual citizenship but Passport Canada encourages its citizens to travel abroad on their Canadian passport, so they can access Canadian consular services.[118]

Ethnic ancestry

Canada has 34 ethnic groups with at least 100,000 members each, of which 11 have over 1 million people and numerous others are represented in smaller amounts.[Note 1] According to the 2006 census, the largest self-reported ethnic origin is "Canadian/Canadien" (32%),[Note 2] followed by English (21%), French (15.8%), Scottish (15.1%), Irish (13.9%), German (10.2%), Italian (4.6%), Chinese (4.3%), North American Indian (4.0%),[Note 3] Ukrainian (3.9%), and Dutch (Netherlands) (3.3%).[119] In the 2006 census, over five million Canadians identified themselves as a member of a visible minority. Together, they make up 16.2% of the total population: most numerous among these are South Asian (4.0%), Black (2.5%), and Filipino (1.1%).[119] Aboriginal peoples are not considered a visible minority under the Employment Equity Act,[120] and is the definition that Statistics Canada also uses.

| Ethnic origin[Note 1] | % | Population | Area of largest proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian/ Canadien[Note 2] |

32.22% | 10,066,290 | Quebec (66.2%) |

| English Canadian | 21.03% | 6,570,015 | Newfoundland and Labrador (43.2%) |

| French Canadian (excluding Acadians & Québécois) |

15.82% | 4,941,210 | Quebec (28.9%) |

| Scottish Canadian | 15.11% | 4,719,850 | Prince Edward Island (40.5%) |

| Irish Canadian | 13.94% | 4,354,155 | Prince Edward Island (29.2%) |

| German Canadian | 10.18% | 3,179,425 | Saskatchewan (30.0%) |

| Italian Canadian | 4.63% | 1,445,335 | Ontario (7.2%) |

| Chinese Canadian | 4.31% | 1,346,510 | British Columbia (10.6%) |

| North American Indian[Note 3] | 4.01% | 1,253,615 | Northwest Territories (36.5%) |

| Ukrainian Canadian | 3.87% | 1,209,085 | Manitoba (14.8%) |

| Dutch Canadian (Netherlands) |

3.32% | 1,035,965 | Alberta (5.3%) |

| Polish Canadian | 3.15% | 984,565 | Manitoba (7.3%) |

| East Indian Canadian | 3.08% | 962,665 | British Columbia (5.7%) |

| Russian Canadian | 1.60% | 500,600 | Manitoba (4.3%) |

| Welsh Canadian | 1.41% | 440,965 | Yukon (3.1%) |

| Filipino Canadian | 1.40% | 436,190 | Manitoba (3.5%) |

| Norwegian Canadian | 1.38% | 432,515 | Saskatchewan (7.2%) |

| Portuguese Canadian | 1.32% | 410,850 | Ontario (2.4%) |

| Métis | 1.31% | 409,065 | Northwest Territories (6.9%) |

| British Canadian (British Isles not included elsewhere) |

1.29% | 403,915 | Yukon (2.3%) |

| Swedish Canadian | 1.07% | 334,765 | Saskatchewan (3.5%) |

| Spanish Canadian | 1.04% | 325,730 | British Columbia (1.3%) |

| American Canadian | 1.01% | 316,350 | Yukon (2.0%) |

| Hungarian Canadian (Magyar) |

1.01% | 315,510 | Saskatchewan (2.9%) |

| Jewish Canadian (From all continents) |

1.01% | 315,120 | Ontario (1.5%) |

- For a complete list see: Canadian ethnic groups

Culture

Canada's culture is a product of its ethnicities, languages, religions, political and legal system(s). Being a settler nation, Canada has been shaped by waves of migration that have combined to form a unique blend of art, cuisine, literature, humour and music.[121] Today, Canada has a diverse makeup of nationalities and constitutional protection for policies that promote multiculturalism rather than cultural assimilation.[122] In Quebec, cultural identity is strong, and many French-speaking commentators speak of a Quebec culture as distinguished from English Canadian culture.[123] However as a whole Canada is a cultural mosaic a collection of several regional, aboriginal, and ethnic subcultures.[124][125]

Canadian government policies such as official bilingualism, publicly funded health care, higher and more progressive taxation, outlawing capital punishment, strong efforts to eliminate poverty, strict gun control, leniency in regard to drug use, and, most recently, legalizing same-sex marriage are social indicators of Canada's political and cultural values.[126] American media and entertainment are popular, if not dominant, in English Canada; conversely, many Canadian cultural products and entertainers are successful in the United States and worldwide.[127] The Government of Canada has also influenced culture with programs, laws and institutions. It has created Crown corporations to promote Canadian culture through media and has also tried to protect Canadian culture by setting legal minimums on Canadian content.[128]

Canadian culture has historically been influenced by Aboriginal, French and British cultures and traditions. Most of Canada's territory was inhabited and developed later than other European colonies in the Americas, with the result that themes and symbols of pioneers, trappers, and traders were important in the early development of the Canadian identity.[129] First Nations played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting exploration of the continent during the North American fur trade.[130] The British conquest of New France in the mid-1700s brought a large Francophone population under British Imperial rule, creating a need for compromise and accommodation.[131] The new British rulers left alone much of the religious, political, and social culture of the French-speaking habitants, guaranteeing the right of the Canadiens to practise the Catholic faith and to the use of French civil law (now Quebec law) through the Quebec Act of 1774.[132]

The Constitution Act of 1867 was designed to meet the growing calls of Canadians for autonomy from British rule, while avoiding the overly strong decentralization that contributed to the Civil War in the United States.[133] The compromises made by the Fathers of Confederation set Canadians on a path to bilingualism, and this in turn contributed to an acceptance of diversity.[134][135]

The Canadian Forces and overall civilian participation in the First World War and Second World War helped to foster Canadian nationalism,[136][137][138] however in 1917 and 1944 conscription crisis's highlighted the considerable rift along ethnic lines between Anglophones and Francophones.[139] As a result of the First and Second World Wars, the Government of Canada became more assertive and less deferential to British authority.[140] With the gradual loosening of political ties to the United Kingdom and the modernization of Canadian immigration policies, in the 20th century immigrants with African, Caribbean and Asian nationalities have added to the Canadian identity and its culture.[141] The multiple origins immigration pattern continues today with the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from non British or French backgrounds.[142]

Multiculturalism in Canada was adopted as the official policy of the government during the premiership of Pierre Elliot Trudeau in the 1970s and 1980s.[143] The Canadian government has often been described as the instigator of multicultural ideology because of its public emphasis on the social importance of immigration.[144] Multiculturalism is administered by the Department of Citizenship and Immigration and reflected in the law through the Canadian Multiculturalism Act[145] and section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[146]

Religion

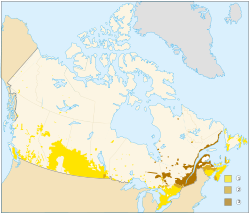

Religion in Canada (2011 census)[147]

Canada as a nation is religiously diverse, encompassing a wide range of groups, beliefs and customs.[148] The preamble to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms references "God", and the monarch carries the title of "Defender of the Faith".[149] However Canada has no official religion and support for religious pluralism (Freedom of religion in Canada) is an important part of Canada's political culture.[150][151] With Christianity on the decline, having once been central and integral to Canadian culture and daily life;[152] commentators suggest that Canada has come to enter a post-Christian period in a secular state, where the practice of religion has "moved to the margins of public life", with irreligion in Canada on the rise.[153]

The 2011 Canadian census reported that 67.3% of Canadians identify as being Christians; of this, Catholics make up the largest group, accounting for 38.7 percent of the population.[147] The largest Protestant denomination is the United Church of Canada (accounting for 6.1% of Canadians), followed by Anglicans (5.0%), and Baptists (1.9%).[147] About 23.9% of Canadians declare no religious affiliation, including agnostics, atheists, humanists, and other groups.[147] The remaining are affiliated with non-Christian religions, the largest of which is Islam (3.2%), followed by Hinduism (1.5%), Sikhism (1.4%) Buddhism (1.1%) and Judaism (1.0%).[147]

Before the arrival of European colonists and explorers, First Nations followed a wide array of mostly animistic religions.[154]During the colonial period, the French settled along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, specifically Latin rite Roman Catholics, including a number of Jesuits dedicated to converting Aboriginals; an effort that eventually proved successful.[155] The first large Protestant communities were formed in the Maritimes after the British conquest of New France, followed by American Protestant settlers displaced by the American Revolution.[156] The late nineteenth century saw the beginning of a large shift in Canadian immigration patterns. Large numbers of Irish and Southern Europeans immigrants were creating new Roman Catholic communities in English Canada.[157] The settlement of the west brought significant Eastern Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe and Mormon and Pentecostal immigrants from the United States.[158]

The earliest documentation of Jewish presence in Canada are the 1754 British Army records from the French and Indian War.[159] In 1760, General Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst attacked and won Montreal for the British. In his regiment there were several Jews, including four among his officer corps, most notably Lieutenant Aaron Hart who is considered the father of Canadian Jewry.[159] The Islamic, Sikh, Hindu and Buddhist communities although small, are as old as the nation itself. The 1871 Canadian Census (first "Canadian" national census) indicated thirteen Muslims among the populace,[160] with approximately 5000 Sikh by 1908.[161] The first Canadian mosque was constructed in Edmonton in 1938, when there were approximately 700 Muslims in Canada.[162] Buddhism first arrived in Canada when Japanese immigrated during the late 19th century.[152] The first Japanese Buddhist temple in Canada was built in Vancouver in 1905.[163] The influx of immigrants in the late 20th century with Sri Lankan, Japanese, Indian and Southeast Asian customs, has contributed to the recent expansion of the Sikh, Hindu and Buddhist communities.[164]

Languages

A multitude of languages are used by Canadians, with English and French (the official languages) being the mother tongues of 59.7% and 23.2% of the population respectively.[165] Approximately twenty percent or over six million people in Canada list a non-official language as their mother tongue.[166] Some of the most common first languages include: Chinese (3.1%), Italian (1.4%), German (1.2%), Spanish (1.2%), Punjabi (1.1%), Tagalog (0.9%), Tamil (0.8%), Gujarati (0.6%).[167] Less than one percent of Canadians (just over 250,000 individuals) can speak an aboriginal language. About half this number (129,865) reported using an aboriginal language on a daily basis.[168]

English and French are recognized by the Constitution of Canada as official languages.[169] Thus all federal government laws are enacted in both English and French with government services available in both languages.[169] Two of Canada's territories give official status to indigenous languages. In Nunavut, Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun are official languages alongside the national languages of English and French, and Inuktitut is a common vehicular language in territorial government.[170] In the Northwest Territories, the Official Languages Act declares that there are eleven different languages: Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwich’in, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey and Tłįchǫ.[171] Multicultural media offers specialty television channels, newspapers and other publications in many minority languages, that are widely accessible across the county.[172]

In Canada, as elsewhere in the world of European colonies, the frontier of European exploration and settlement tended to be a linguistically diverse and fluid place, as cultures using different languages met and interacted. The need for a common means of communication between the indigenous inhabitants and new arrivals for the purposes of trade and (in some cases) intermarriage led to the development of Mixed languages.[173] Languages like Michif, Chinook Jargon and Bungi creole tended to be highly localized and were often spoken by only a small number of individuals who were frequently capable of speaking another language.[174]

See also

- Canuck

- Demographics of Canada

- List of Canadians

- Persons of National Historic Significance

- Template:Wikipedia books link

Notes

- ^ a b c Data for ethnic origin was collected by self-declaration, labels may not necessarily describe the true (genetic) ancestry of respondents. Many respondents also acknowledged multiple ancestries, thus data reflects both single and multiple responses and may exceed the total population count. Source: "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada - Data table". Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 16, 2011. Additional data: "2006 Census release topics". Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c All citizens of Canada are classified as "Canadians" as defined by Canada's nationality laws. However since 1996 "Canadian" as an ethnic group has been added to census questionnaires for possible ancestry. "Canadian" was included as an example on the English questionnaire and "Canadien" as an example on the French questionnaire. "The majority of respondents to this selection are from the eastern part of the country that was first settled. Respondents generally are visibly European (Anglophones and Francophones), however no-longer self identify with their ethnic ancestral origins. This response is attributed to a multitude and/or generational distance from ancestral lineage. Source 1: Jack Jedwab (April 2008). "Our 'Cense' of Self: the 2006 Census saw 1.6 million 'Canadian'" (PDF). Association for Canadian Studies. Retrieved March 7, 2011. Source 2: Don Kerr (2007). The Changing Face of Canada: Essential Readings in Population. Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 313–317. ISBN 978-1-55130-322-2.

- ^ a b c The category "North American Indian" includes respondents who indicated that their ethnic origins were from a Canadian First Nation, or another, non-Canadian aboriginal group (excluding Inuit and Métis). Source: "How Statistics Canada Identifies Aboriginal Peoples". Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Distribution of Canadians Abroad" (Requires selection of location for data). Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ "Statistics of Mexico" (PDF). 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ "Tables on the population in Sweden 2008" (PDF). Statistics of Sweden. 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Source: "Canada's population hits 35 million". Toronto star (information from Statistics Canada).

- ^ "Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit". Statistics Canada. 2012.

- ^ "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas" (PDF). University College London 73:524–539. 2003. doi:10.1086/377588. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Cinq-Mars, J (2001). "On the significance of modified mammoth bones from eastern Beringia" (PDF). The World of Elephants – International Congress, Rome. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Wright, JV (September 27, 2009). "A History of the Native People of Canada: Early and Middle Archaic Complexes". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Griebel, Ron. "The Bluefish Caves". Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Beringia: humans were here". Montreal Gazette. May 17, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Cinq-Mars, Jacques (2001). "Significance of the Bluefish Caves in Beringian Prehistory". Canadian Museum of Civilization. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Hayes, Derek (2008). Canada: an illustrated history. Douglas & Mcintyre. pp. 7, 13. ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5.

- ^ Macklem, Patrick (2001). Indigenous difference and the Constitution of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8020-4195-1.

- ^ Sonneborn, Liz (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–12. ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Donna M (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Thornton, Russell (2000). "Population history of Native North Americans". A population history of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13, 380. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Bailey, Garrick Alan (2008). Handbook of North American Indians: Indians in contemporary society. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- ^ "Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage: Culture". Canadian Museum of Civilization. May 12, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "ICC Charter". Inuit Circumpolar Council. 2007. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "In the Kawaskimhon Aboriginal Moot Court Factum of the Federal Crown Canada". University of Manitoba Faculty of Law. 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "What to Search: Topics". Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups. Library and Archives Canada. May 27, 2005. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Tanner, Adrian (1999). "3. Innu-Inuit 'Warfare'". Innu Culture. Department of Anthropology, Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Reeves, Arthur Middleton (2009). The Norse Discovery of America. BiblioLife. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-559-05400-6.

- ^ "John Cabot's voyage of 1497". Memorial University of Newfoundland. 2000. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier: spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 978-1-58465-427-8.

- ^ Cartier, Jacques; Biggar, Henry Percival; Cook, Ramsay (1993). The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. University of Toronto Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8020-6000-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rose, George A (October 1, 2007). Cod: The Ecological History of the North Atlantic Fisheries. Breakwater Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-55081-225-1.

- ^ Ninette Kelley; Michael J. Trebilcock (September 30, 2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C; Arnold, James; Wiener, Roberta (September 30, 2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Phillip Alfred Buckner; John G. Reid (1994). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-8020-6977-1.

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J (2008). Wars of the age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-313-33046-9.

- ^ Allaire, Gratien (May 2007). "From "Nouvelle-France" to "Francophonie canadienne": a historical survey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2007 (185): 25–52. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.024.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

bucknerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hicks, Bruce M (March 2010). "Use of Non-Traditional Evidence: A Case Study Using Heraldry to Examine Competing Theories for Canada's Confederation". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 23 (1): 87–117. doi:10.3828/bjcs.2010.5.

- ^ Todd Leahy; Raymond Wilson (September 30, 2009). Native American Movements. Scarecrow Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8108-6892-2.

- ^ McNairn, Jeffrey L (2000). The capacity to judge. University of Toronto Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8020-4360-3.

- ^ This is an 1885 photograph of the now-destroyed 1884 painting.

- ^ "Immigration History of Canada". Marianopolis College. 2004. Archived from the original on December 16, 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Romney, Paul (Spring 1989). "From Constitutionalism to Legalism: Trial by Jury, Responsible Government, and the Rule of Law in the Canadian Political Culture". Law and History Review. 7 (1). University of Illinois Press: 128.

- ^ Evenden, Leonard J (1992). "The Pacific Coast Borderland and Frontier". In Janelle, Donald G (ed.). Geographical snapshots of North America. Guilford Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-89862-030-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Territorial evolution". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Canada: History". Country Profiles. Commonwealth Secretariat. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Bothwell, Robert (1996). History of Canada Since 1867. Michigan State University Press. pp. 31, 207–310. ISBN 978-0-87013-399-2.

- ^ Bumsted, JM (1996). The Red River Rebellion. Watson & Dwyer. ISBN 978-0-920486-23-8.

- ^ a b "Building a nation". Canadian Atlas. Canadian Geographic. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald". Library and Archives Canada. 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Cook, Terry (2000). "The Canadian West: An Archival Odyssey through the Records of the Department of the Interior". The Archivist. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). McClelland & Stewart. pp. 130–158, 173, 203–233, 258. ISBN 978-0-7710-6514-9.

- ^ Haglund, David G (1999). Security, strategy and the global economics of defence production. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-88911-875-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

hailwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Robert B. Bryce (June 1, 1986). Maturing in Hard Times: Canada's Department of Finance through the Great Depression. McGill-Queens. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7735-0555-1.

- ^ Mulvale, James P (July 11, 2008). "Basic Income and the Canadian Welfare State: Exploring the Realms of Possibility". Basic Income Studies. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1084.

- ^ Goddard, Lance (2005). Canada and the Liberation of the Netherlands. Dundurn Press. pp. 225–232. ISBN 978-1-55002-547-7.

- ^ Bothwell, Robert (2007). Alliance and illusion: Canada and the world, 1945–1984. UBC Press. pp. 11, 31. ISBN 978-0-7748-1368-6.

- ^ Summers, WF. "Newfoundland and Labrador". Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Mackey, Eva (2002). The house of difference: cultural politics and national identity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8020-8481-1.

- ^ Landry, Rodrigue (May 2007). "Official language minorities in Canada: an introduction". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2007 (185): 1–9. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.022.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Esses, Victoria M (July 1996). "Multiculturalism in Canada: Context and current status". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 28 (3): 145–152. doi:10.1037/h0084934.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sarrouh, Elissar (January 22, 2002). "Social Policies in Canada: A Model for Development". Social Policy Series, No. 1. United Nations. pp. 14–16, 22–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Bickerton, James; Gagnon, Alain, ed. (2004). Canadian Politics (4th ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 250–254, 344–347. ISBN 978-1-55111-595-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Légaré, André (2008). "Canada's Experiment with Aboriginal Self-Determination in Nunavut: From Vision to Illusion". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 15 (2–3): 335–367. doi:10.1163/157181108X332659.

- ^ Munroe, HD (2009). "The October Crisis Revisited: Counterterrorism as Strategic Choice, Political Result, and Organizational Practice". Terrorism and Political Violence. 21 (2): 288–305. doi:10.1080/09546550902765623.

- ^ a b Sorens, J (December 2004). "Globalization, secessionism, and autonomy". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 727–752. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.10.003.

- ^ Leblanc, Daniel (August 13, 2010). "A brief history of the Bloc Québécois". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ Betz, Hans-Georg; Immerfall, Stefan (1998). The new politics of the Right: neo-Populist parties and movements in established democracies. St. Martinʼs Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-312-21134-9.

- ^ "Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Sourour, Teresa K (1991). "Report of Coroner's Investigation" (PDF). Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "The Oka Crisis" (Digital Archives). CBC. 2000. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Roach, Kent (2003). September 11: consequences for Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 15, 59–61, 194. ISBN 978-0-7735-2584-9.

- ^ "Canada and Multilateral Operations in Support of Peace and Stability". National Defence and the Canadian Forces. 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "UNPROFOR". Royal Canadian Dragoons. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Jockel, Joseph T (2008). "Canada and the war in Afghanistan: NATO's odd man out steps forward". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 6 (1): 100–115. doi:10.1080/14794010801917212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Canada Recession: Global Recovery Still Fragile 3 Years On". Huffington Post. July 22, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ "Canada's military contribution in Libya". CBC. October 20, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ "Environment — Greenhouse Gases (Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Person)". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Wayne A. Cornelius (2004). Controlling immigration: a global perspective. Stanford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8047-4490-4.

- ^ a b "Canada – Permanent residents by gender and category, 1984 to 2008". Facts and figures 2008 – Immigration overview: Permanent and temporary residents. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. August 25, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ Rodger W. Bybee; Barry McCrae (2009). Pisa Science 2006: Implications for Science Teachers and Teaching. NSTA Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-933531-31-1.

- ^ "Projections of the Diversity of the Canadian Population". Statistics Canada. March 9, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ John C. Hudson (2002). Across This Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1.

- ^ Mark G. Mcgowan. "Irish Catholics: Migration, Arrival, and Settlement before the Great Famine". The Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. Multicultural Canada. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Paul R. Magocsi; Multicultural History Society of Ontario (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. pp. 736–. ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6.

- ^ N.E.S. Griffiths (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- ^ Frances Standford. Development of Western Canada Gr. 7-8. On The Mark Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-77072-743-4.

- ^ "Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups". Library and Archives Canada (Canadian Genealogy Centre). 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ John Powell (2005). Encyclopedia of North American immigration. Infobase Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8160-4658-4. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ John M. Murrin; Paul E. Johnson; James M. McPherson (2008). Liberty, Equality, Power, A History of the American People: To 1877. Cengage Learning. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-495-56634-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ N. N. Feltes (1999). This Side of Heaven: Determining the Donnelly Murders, 1880. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8020-4486-0.

- ^ Jessica Harland-Jacobs (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-8078-3088-8.

- ^ Lucille H. Campey (2008). Unstoppable Force: The Scottish Exodus to Canada. Dundurn. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-55002-811-9.

- ^ McGowan, Mark (2009). Death or Canada: the Irish Famine Migration to Toronto 1847. Novalis Publishing Inc. p. 97. ISBN 2-89646-129-9.

- ^ Bruce S. Elliott (2004). Irish migrants in the Canadas [electronic resource]: a new approach. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7735-6992-8.

- ^ Patricia Wong Wong Hall; Hwang, Victor M. (2001). Anti-Asian Violence in North America: Asian American and Asian Canadian Reflections on Hate, Healing, and Resistance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7425-0459-2.

- ^ Huang, Annian (2006). “The” Silent Spikes: Chinese Laborers and the Construction Auf North American Railroads. China Intercontinental Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-7-5085-0988-4.

- ^ "Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Facts and Figures". Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2010.

- ^ "Canadians in Context — Population Size and Growth". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Sandy Hobbs; Jim MacKechnie; Michael Lavalette (1999). Child Labour: A World History Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-87436-956-4.

- ^ Klaus Martens (2004). The Canadian Alternative. Königshausen & Neumann. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-8260-2636-2.

- ^ Day, Richard J. F (2000). Multiculturalism and the history of Canadian diversity. University of Toronto Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8020-8075-2.

- ^ Ksenych, Edward; Liu, David (2001). Conflict, Order and Action : Readings in Sociology. Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-1-55130-192-1.

- ^ "Immigration Policy in the 1970s". Canadian Heritage (Multicultural Canada). 2004. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Frank Kusch (2001). All American boys: draft dodgers in Canada from the Vietnam War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-275-97268-4.

- ^ Vijay Agnew (2007). Interrogating Race and Racism. University of Toronto Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8020-9509-1.

- ^ Wilkinson, Paul F. (1980). In celebration of play: an integrated approach to play and child development. Taylor & Francis. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7099-0024-5.

- ^ Kristin Good (2009). Municipalities and Multiclturalism: The Politics of Immigration in Toronto and Vancouver. University of Toronto Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4426-0993-8.

- ^ Stephen Schneider (2009). Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada. John Wiley & Sons. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-470-83500-5.

- ^ "Canadians want illegal immigrants deported: poll". Ottawa Citizen. CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc. October 20, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ Chase, Steven; Curry, Bill; Galloway, Gloria (May 6, 2008). "Thousands of illegal immigrants missing: A-G". Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "Citizenship Act (R.S., 1985, c. C-29)". Department of Justice Canada. 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Citizenship Act and current issues -BP-445E". Government of Canada - Law and Government Division. 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Sinha, Jay; Young, Margaret (January 31, 2002). "Bill C-11 : Immigration and Refugee Protection Act". Law and Government Division, Government of Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Irene Bloemraad (2006). Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants And Refugees in the United States And Canada. University of California Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-520-24898-4.

- ^ "Canadian immigration". Canada Immigration Visa. 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Canada's Generous Program for Refugee Resettlement Is Undermined by Human Smugglers Who Abuse Canada's Immigration System". Public Safety Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Karla Zimmerman (2008). Canada. Ediz. inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-74220-320-1.

- ^ "CBC News - Canada - Estimated 2.8 million Canadians live abroad". Canada: CBC. October 29, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "United States Total Canadian Population: Fact Sheet" (PDF). Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ Douglas Gray (2010). The Canadian Snowbird Guide: Everything You Need to Know about Living Part-Time in the USA and Mexico. John Wiley and Sons. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-470-73942-6.

- ^ a b "2006 Census: Ethnic origin, visible minorities, place of work and mode of transportation". The Daily. Statistics Canada. April 2, 2008. Archived from the original on August 23, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "Classification of visible minority". Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. July 25, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Bobbie Kalman (2009). Canada: The culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-7787-9284-0.

- ^ David DeRocco; John F. Chabot (2008). From Sea to Sea to Sea: A Newcomer's Guide to Canada. Full Blast Productions. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-9784738-4-6.

- ^ Daniel Franklin; Michael J. Baun (1995). Political culture and constitutionalism: a comparative approach. M.E. Sharpe. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-56324-416-2.

- ^ Allan D. English (2004). Understanding Military Culture: A Canadian Perspective. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7735-7171-6.

- ^ Burgess, Ann Carroll; Burgess, Tom (2005). Guide to Western Canada. Globe Pequot Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7627-2987-6.

- ^ Darrell Bricker; John Wright (2005). What Canadians Think About Almost Everything. Doubleday Canada. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-385-65985-7.

- ^ Blackwell, John D (2005). "Culture High and Low". International Council for Canadian Studies World Wide Web Service. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- ^ Robert Armstrong (2010). Broadcasting Policy in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4426-1035-4.

- ^ "Canada in the Making: Pioneers and Immigrants". The History Channel. August 25, 2005. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ Richard White (1999). Power and place in the North American West. University of Washington Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-295-97773-7.

- ^ Dufour, Christian (1990). A Canadian Challenge. IRPP. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-88982-105-7.

- ^ "Original text of The Quebec Act of 1774". Canadiana (Library and Archives Canada). 2004 (1774). Retrieved 2010-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "American Civil war". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Founcation. 2003. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ François Vaillancourt, Olivier Coche. Official Language Policies at the Federal Level in Canada:costs and Benefits in 2006. The Fraser Institute. p. 11. GGKEY:B3Y7U7SKGUD.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R (2002). Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a short introduction. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8020-8469-9.

- ^ S&S Learning Materials. Exploring Canada Gr. 4-6. On The Mark Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-77072-758-8.

- ^ Nersessian, Mary (April 9, 2007). "Vimy battle marks birth of Canadian nationalism". CTV Television Network. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ "Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Citizenship And Immigration, 1900–1977 – The growth of Canadian nationalism". Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Paul-André Linteau; René Durocher; Jean-Claude Robert (1983). Quebec: A History 1867-1929. James Lorimer & Company. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-88862-604-2.

- ^ "Canada and the League of Nations". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Örn Bodvar Bodvarsson; Hendrik Van den Berg (2009). The economics of immigration: theory and policy. Springer. p. 380. ISBN 978-3-540-77795-3.

- ^ Giuliana B. Prato (2009). Beyond multiculturalism: views from anthropology. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7546-7173-2.

- ^ James S. Duncan; David Ley (1993). Place/culture/representation. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-415-09451-1.

- ^ Wayland, Shara (1997). "Immigration, Multiculturalism and National Identity in Canada" (PDF). University of Toronto Department of Political Science. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Being Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982)". Electronic Frontier Canada. 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1985, c. 24 (4th Supp.)". Department of Justice Canada. Act current to November 14, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ^ Dianne R. Hales; Lara Lauzon (2009). An Invitation to Health. Cengage Learning. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-17-650009-2.

- ^ Colin MacMillan Coates; University of Edinburgh. Centre of Canadian Studies (2006). Majesty in Canada: essays on the role of royalty. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-55002-586-6.

- ^ "Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982)". Department of Justice Canada. 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Gary Miedema (December 19, 2005). For Canada's Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, and the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7735-2877-2.

- ^ a b Paul Bramadat; David Seljak (2009). Relgion and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7. Cite error: The named reference "BramadatSeljak2009" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Grossman, Cathy Lynn (February 11, 2010). "Christian churches in Canada fading out: USA next?". USA Today. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Elizabeth Tooker (1979). Native North American spirituality of the eastern woodlands: sacred myths, dreams, visions, speeches, healing formulas, rituals, and ceremonials. Paulist Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8091-2256-1.

- ^ John E. Findling; Frank W. Thackeray (2010). What Happened? An Encyclopedia of Events That Changed America Forever. ABC-CLIO. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59884-622-5.

- ^ Roderick MacLeod; Mary Anne Poutanen (2004). Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801B1998. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7735-7183-9.

- ^ John Powell (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Infobase Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4381-1012-7.

- ^ Martynowych, Orest T (1991). Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Inst. of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-920862-76-6.

- ^ a b Jon Bloomberg (2004). The Jewish World In The Modern Age. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-88125-844-8.

- ^ Harold G. Coward; Leslie S. Kawamura (1978). Religion and Ethnicity: Essays. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-88920-064-7.

- ^ Harold G. Coward; John Russell Hinnells; Williams, Raymond Brady (2000). The South Asian religious diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. SUNY Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7914-9302-1.

- ^ Earle Howard Waugh; Sharon McIrvin Abu-Laban; Regula Qureshi (1991). Muslim families in North America. University of Alberta. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-88864-225-7.

- ^ N. Rochelle Yamagishi (2010). Japanese Canadian Journey: The Nakagama Story. Trafford Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4269-8148-7.

- ^ C.D. Naik (2003). Thoughts and Philosophy of Doctor B.R. Ambedkar. Sarup & Sons. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7625-418-2.

- ^ a b "2006 Census: The Evolving Linguistic Portrait, 2006 Census: Highlights". Statistics Canada. 2006 (2010). Retrieved 2010-10-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Charles Boberg (2010). The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-139-49144-0.

- ^ "Population by mother tongue, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. Last modified: 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gordon, Raymond G Jr. (2009), Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15 ed.), Dallas, TX: SIL International, ISBN 1-55671-159-X, retrieved January 20, 2011

- ^ a b "Official Languages Act - 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.)". Act current to July 11th, 2010. Department of Justice. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "Nunavut's Languages". Office of the Languages Commissioner of Nunavut. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ "Highlights of the Official Languages Act". Legislative Assembly of the NWT. 2003. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Louisa S. Ha; Richard J. Ganahl (2007). Webcasting Worldwide: Business Models of an Emerging Global Medium. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8058-5915-7.

- ^ Donald Winford (2003). An Introduction to Contact Linguistics. Wiley. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-631-21251-5.

- ^ Stephen Adolphe Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tyron (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Maps. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1491. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

Further reading

- Bart Beaty; Derek Briton; Gloria Filax (2010). How Canadians Communicate III: Contexts of Canadian Popular Culture. Athabasca University Press. ISBN 978-1-897425-59-6.

- J. M. Bumsted (2003). Canada's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-672-9.

- David Carment; David Bercuson (2008). The World in Canada: Diaspora, Demography, and Domestic Politics. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-7455-7.

- Andrew Cohen (2008). The Unfinished Canadian: The People We Are. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-2286-9.

- Mark Kearney; Randy Ray (2009). The Big Book of Canadian Trivia. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-77070-614-9.

- Ninette Kelley; M. J. Trebilcock (2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- Philip Resnick (2005). The European Roots Of Canadian Identity. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-705-8.

- Madeline A. Richard (1992). Ethnic Groups and Marital Choices: Ethnic History and Marital Assimilation in Canada, 1871 and 1971. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0431-8.

- Jeffrey Simpson (2000). Star-Spangled Canadians: Canadians Living the American Dream. First Harper-Colins hardcover ed. Toronto, Ont.: Harper-Collins Publishers. 391 p. ISBN 0-00-255767-3

- Irvin Studin (September 19, 2006). What Is a Canadian?: Forty-Three Thought-Provoking Responses. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-8321-1.

- "CBC"; Don Gillmor; Pierre Turgeon (2002). Canada: A People's History Vol-1. Vol. 1. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3324-7.

- "CBC"; Don Gillmor; Pierre Turgeon; Achille Michaud (2002). Canada: A People's History Vol-2. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3336-0.

External links

- Canada Year Book 2010 - Statistics Canada

- Canada: A People's History - Teacher Resources - Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Persons of National Historic Significance in Canada - Parks Canada

- Multicultural Canada - Department of Canadian Heritage

- The Canadian Immigrant Experience - Library and Archives Canada

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography – Library and Archives Canada

- Canadiana: The National Bibliography of Canada – Library and Archives Canada