Richmond Park: Difference between revisions

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

===After World War II – present=== |

===After World War II – present=== |

||

From 1945 to 1947, [[James_Stanley_Hey|Stanley Hey]] used the radar equipment on the AORG site on the Polo Field to investigate his wartime discoveries of astronomical radio sources: the [[Sun]] as a radio source, radio reflections from [[Meteor shower|meteor]] trails, and radio noise from cosmic sources. In 1946 Hey's group discovered [[Cygnus A]], later shown to be the first [[radio galaxy]]. |

From 1945 to 1947, [[James_Stanley_Hey|Stanley Hey]] used the radar equipment on the AORG site on the Polo Field to investigate his wartime discoveries of astronomical radio sources: the [[Sun]] as a radio source, radio reflections from [[Meteor shower|meteor]] trails, and radio noise from cosmic sources. In 1946 Hey's group discovered [[Cygnus A]], later shown to be the first [[radio galaxy]]. The Richmond Park installation thus became the first radio observatory in Britain.<ref>Baker, Timothy M. M. (October 2021). "Richmond Park, radio astronomy's birthplace". Richmond History. Richmond Local History Society. 42: 22–27. ISSN 0263-0958.</ref> |

||

[[John Boyd-Carpenter, Baron Boyd-Carpenter|John Boyd-Carpenter]], MP for Kingston-upon-Thames, proposed using the Kingston Gate Camp to help alleviate the local post-war housing shortage but [[Ministry of Works (United Kingdom)|Minister of Works]], [[Charles Key]], was opposed, preferring that the site be eventually returned to its former parkland use.<ref>{{Hansard|url=1947/nov/06/richmond-park-camp-use |title=Richmond Park Camp (Use)|access-date=28 October 2020}}</ref> Key's department refurbished and repurposed the camp as an [[Olympic Village]] for the [[1948 Summer Olympics]].<ref name="Cloake 201">Cloake, p. 201</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/news--olympic-town-at-richmond-park/z74y2sg |title= Olympic Town at Richmond Park|date= 4 June 1948|work=[[BBC News]]|access-date=28 October 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001861/19480731/022/0018|title=The XIVth Olympiad| newspaper=[[The Sphere (newspaper)|The Sphere]]|date=31 July 1948|publisher=[[British Newspaper Archive]] |url-access=limited}}</ref> The Olympic Village was opened by [[David Cecil, 6th Marquess of Exeter|Lord Burghley]] with Key making the announcement, in July 1948.<ref>{{cite film |url=https://www.britishpathe.com/video/VLVA354L6FHKU412LLQ9JN7WB90IO-OPENING-OF-OLYMPIC-CENTRE-IN-LONDON|title=Opening Of Olympic Centre In London 1948|date=5 July 1948|publisher=[[Reuters]]|series=Gaumont British Newsreel|type=Motion picture, black and white|id=film id:VLVA354L6FHKU412LLQ9JN7WB90IO|access-date = 20 May 2021}}</ref> After the Olympics, the camp was used by units of the [[Royal Corps of Signals]] then by the [[Women's Royal Army Corps]] following their formation in 1949 as successor to the wartime ATS. Although it had been hoped to clear the camp during the 1950s, it remained in military use and was used to house service families repatriated following the [[Suez Crisis]] in 1956. It was not until 1965 that the camp was eventually demolished and reintegrated into the park during the following year.<ref name="Rabbitts 145" /><ref name="Hansard_19500703" /><ref>{{cite magazine |first=Michael |last=Davison |url=https://www.mastermindclub.co.uk/app/download/2931472/PASS%2B2005%2B3.pdf|title=When the Olympics Came to Richmond Park|publisher=Mastermind Club|date=July 2005 |pages=11–12}}</ref> |

[[John Boyd-Carpenter, Baron Boyd-Carpenter|John Boyd-Carpenter]], MP for Kingston-upon-Thames, proposed using the Kingston Gate Camp to help alleviate the local post-war housing shortage but [[Ministry of Works (United Kingdom)|Minister of Works]], [[Charles Key]], was opposed, preferring that the site be eventually returned to its former parkland use.<ref>{{Hansard|url=1947/nov/06/richmond-park-camp-use |title=Richmond Park Camp (Use)|access-date=28 October 2020}}</ref> Key's department refurbished and repurposed the camp as an [[Olympic Village]] for the [[1948 Summer Olympics]].<ref name="Cloake 201">Cloake, p. 201</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/news--olympic-town-at-richmond-park/z74y2sg |title= Olympic Town at Richmond Park|date= 4 June 1948|work=[[BBC News]]|access-date=28 October 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001861/19480731/022/0018|title=The XIVth Olympiad| newspaper=[[The Sphere (newspaper)|The Sphere]]|date=31 July 1948|publisher=[[British Newspaper Archive]] |url-access=limited}}</ref> The Olympic Village was opened by [[David Cecil, 6th Marquess of Exeter|Lord Burghley]] with Key making the announcement, in July 1948.<ref>{{cite film |url=https://www.britishpathe.com/video/VLVA354L6FHKU412LLQ9JN7WB90IO-OPENING-OF-OLYMPIC-CENTRE-IN-LONDON|title=Opening Of Olympic Centre In London 1948|date=5 July 1948|publisher=[[Reuters]]|series=Gaumont British Newsreel|type=Motion picture, black and white|id=film id:VLVA354L6FHKU412LLQ9JN7WB90IO|access-date = 20 May 2021}}</ref> After the Olympics, the camp was used by units of the [[Royal Corps of Signals]] then by the [[Women's Royal Army Corps]] following their formation in 1949 as successor to the wartime ATS. Although it had been hoped to clear the camp during the 1950s, it remained in military use and was used to house service families repatriated following the [[Suez Crisis]] in 1956. It was not until 1965 that the camp was eventually demolished and reintegrated into the park during the following year.<ref name="Rabbitts 145" /><ref name="Hansard_19500703" /><ref>{{cite magazine |first=Michael |last=Davison |url=https://www.mastermindclub.co.uk/app/download/2931472/PASS%2B2005%2B3.pdf|title=When the Olympics Came to Richmond Park|publisher=Mastermind Club|date=July 2005 |pages=11–12}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:52, 28 October 2021

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

Isabella Plantation, Richmond Park | |

| Location | Greater London |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | TQ200730 |

| Interest | Biological, historical |

| Area | 955 hectares (2360 acres)[1] |

| Notification | 1992 |

| Location map | Magic Map |

Richmond Park, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, was created by Charles I in the 17th century[2] as a deer park. The largest of London's Royal Parks, it is of national and international importance for wildlife conservation. The park is a national nature reserve, a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Special Area of Conservation and is included, at Grade I, on Historic England's Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest in England. Its landscapes have inspired many famous artists and it has been a location for several films and TV series.

Richmond Park includes many buildings of architectural or historic interest. The Grade I-listed White Lodge was formerly a royal residence and is now home to the Royal Ballet School. The park's boundary walls and ten other buildings are listed at Grade II, including Pembroke Lodge, the home of 19th-century British Prime Minister Lord John Russell and his grandson, the philosopher Bertrand Russell. In 2020, Historic England also listed two other features in the park – King Henry's Mound which is possibly a round barrow[3] and another (unnamed) mound which could be a long barrow.[4][5][6]

Historically the preserve of the monarch, the park is now open for all to use and includes a golf course and other facilities for sport and recreation. It played an important role in both world wars and in the 1948 and 2012 Olympics.

Overview

Size

Richmond Park is the largest of London's Royal Parks.[7] It is the second-largest park in London (after the 10,000 acre Lee Valley Park, whose area extends beyond the M25 into Hertfordshire and Essex) and is Britain's second-largest urban walled park after Sutton Park,[1] Birmingham. Measuring 3.69 square miles (955 hectares or 2,360 acres),[1] it is comparable in size to Paris's Bois de Vincennes (995 ha or 2,458 ac)[8] and Bois de Boulogne (846 ha or 2,090 ac).[9] It is almost half the size of Casa de Campo (Madrid) (1750 ha or 4324.34 ac)[10] and around three times the size of Central Park in New York (341 ha or 843 ac).[11]

Status

Of national and international importance for wildlife conservation, most of Richmond Park (856 hectares; 2115 acres) is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI),[12][13] a National Nature Reserve (NNR)[14] and a Special Area of Conservation (SAC).[15][16] The largest Site of Special Scientific Interest in London, it was designated as an SSSI in 1992,[13] excluding the area of the golf course, Pembroke Lodge Gardens and the Gate Gardens.[16] In its citation, Natural England said: "Richmond Park has been managed as a royal deer park since the seventeenth century, producing a range of habitats of value to wildlife. In particular, Richmond Park is of importance for its diverse deadwood beetle fauna associated with the ancient trees found throughout the parkland. In addition the park supports the most extensive area of dry acid grassland in Greater London."[13]

The park was designated as an SAC in April 2005 on account of its having "a large number of ancient trees with decaying timber. It is at the heart of the south London centre of distribution for stag beetle Lucanus cervus, and is a site of national importance for the conservation of the fauna of invertebrates associated with the decaying timber of ancient trees".[17]

Since October 1987 the park has also been included, at Grade I, on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest in England, being described in Historic England's listing as "A royal deer park with pre C15 origins, imparked by Charles I and improved by subsequent monarchs. A public open space since the mid C19".[18]

Geography

Richmond Park is located in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It is close to Richmond, Ham, Petersham, Kingston upon Thames, Wimbledon, Roehampton and East Sheen.[1]

Organisation

Governance

The Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport manages Richmond Park and the other Royal Parks of London under powers set out in the Crown Lands Act 1851, which transferred management of the parks from the monarch to the government. Day-to-day management of the Royal Parks has been delegated to The Royal Parks, an executive agency of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The Royal Parks' Board sets the strategic direction for the agency. Appointments to the Board are made by the Mayor of London.[19]

The Friends of Richmond Park and the Friends of Bushy Park co-chair the Richmond and Bushy Parks Forum, comprising 38 local groups of local stakeholder organisations.[20] The forum was formed in September 2010 to consider proposals to bring Richmond Park and Bushy Park – and London's other royal parks – under the control of the Mayor of London through a new Royal Parks Board[20][21] and to make a joint response. Although welcoming the principles of the new governance arrangements, the forum (in 2011) and the Friends of Richmond Park (in 2012) have expressed concerns about the composition of the new board.[20][22][23]

Access

Richmond Park is the most visited royal park outside central London, with 4.4 million visits in 2014.[24] The park is enclosed by a high wall with several gates. The gates either allow pedestrian and bicycle access only, or allow bicycle, pedestrian and other vehicle access. The gates for motor vehicle access are open only during daylight hours, and the speed limit is 20 mph. The gates for pedestrians and cyclists are open 24 hours a day apart from during the deer cull in February and November when the park is closed in the evenings. Apart from taxis, no commercial vehicles are allowed unless they are being used to transact business with residents of the park.[25]

From March to October, a free bus service runs on Wednesdays, stopping at the main car parks and the gate at Isabella Plantation nearest Peg's Pond.[26]

The gates open to motor traffic are: Sheen Gate, Richmond Gate, Ham Gate, Kingston Gate, Roehampton Gate and (for access to Richmond Park Golf Course only) Chohole Gate.[27][28] There is pedestrian and bicycle access to the park 24 hours a day except during the deer cull in February and November when the pedestrian gates are closed between 8:00 pm and 7:30 am.[29] However, since 2020, there has been restricted through traffic in Richmond Park, for example restricted traffic between Richmond Gate and Roehampton Gate at weekends.[30]

The park has designated bridleways and cycle paths. These are shown on maps and noticeboards displayed near the main entrances, along with other regulations that govern use of the park.[27] The bridleways are special in that they are for horses (and their riders) only and not open to cyclists like normal bridleways.

The Beverley Brook Walk runs through the park between Roehampton Gate and Robin Hood Gate.[31] The Capital Ring walking route passes through the park from Robin Hood Gate to Petersham Gate.

Cycling is allowed only on main roads, on National Cycle Route 4 through the centre of the park and on the Tamsin Trail (the shared-use pedestrian–cycle path that runs close to the park's perimeter).[32][33] National Cycle Route 4 crosses the park between Ham Gate in the west and Roehampton Gate in the east, skirting Pen Ponds and White Lodge. It interlinks with the Thames Cycle Route and forms part of the London Cycle Network.[34] The speed limit on this route through the centre of the park, where it is off the main road, is 10 mph.[16]

As the park is a national nature reserve and a Site of Special Scientific Interest, all dog owners are required to keep their dogs under control while in the park. This includes not allowing their dog to disturb other park users or disrupt wildlife. In 2009, after some incidents leading to the death of wildfowl, the park's dogs-on-leads policy was extended. Park users are said to believe that the deer are feeling increasingly threatened by the growing number of dogs using the park[35] and Royal Parks advises against walking dogs in the park during the deer's birthing season.[36]

Law enforcement

A mugging at gunpoint in 1854 reputedly led to the establishment of a park police force.[37] Until 2005 the park was policed by the separate Royal Parks Constabulary but that has now been subsumed into the Royal Parks Operational Command Unit of the Metropolitan Police.[38] The mounted police have been replaced by a patrol team in a four-wheel drive vehicle. In 2015 the Friends of Richmond Park expressed concern about plans to cut the numbers of police in the park to half the level that they were ten years previously, despite an increase in visitor numbers and in incidents of crime.[39]

In July 2012 it was reported that police have been given the power to issue £50 on-the-spot fines for littering, cycling outside designated areas and for dog fouling offences.[40] In August 2012 a dog owner was ordered to pay £315 after allowing five dogs to chase ducks in the park.[41] Since 2013 commercial dog-walkers have been required to apply for licences to walk dogs in the park and are allowed to walk only four dogs at a time.[42] In 2013 a cyclist was successfully prosecuted for speeding at 37 mph in the park.[43] In 2015 a cycling club member was fined for speeding at 41 mph and faced disciplinary action from his cycling club, which uses the park for training.[44] In 2014 and 2015 two men were prosecuted for picking mushrooms in the park.[45][46]

Sport and recreation

Cycling: Cycles are available for hire near Roehampton Gate and, at peak times, near Pembroke Lodge.[47] The Tamsin Trail (shared between pedestrians and cyclists) provides a circuit of the park and is almost entirely car-free.[33]

Fishing is allowed, by paid permit, on Pen Ponds from mid-June to mid-March.[47]

Golf is played at Richmond Park Golf Course, a public facility opened in 1923 by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII). It has two 18-hole golf courses and practice facilities and is accessed from Chohole Gate.

Horse riding: Horses from several local stables are ridden in the park.[47]

Rugby: A section of the grassland to the north of the Roehampton Gate is maintained and laid out during the winter months for rugby; there are three pitches. At weekends, this area is hired extensively to Rosslyn Park Rugby Football Club. The club buses visiting teams to and from the park pitches from its nearby clubhouse and changing rooms.[47]

Running: The Tamsin Trail is a 7.2 miles (11.6 km) trail around the park which is popular with runners. Members of Barnes Runners complete at least one circumnavigation of it on the first and third Sunday of every month. The Richmond Park Parkrun, a 5 km organised run, takes place every Saturday.[48]

There are children's playgrounds at Kingston Gate and Petersham Gate.[47]

Friends of Richmond Park

| |

| Abbreviation | FRP |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1961 |

| Legal status | registered charity and membership organisation |

| Headquarters | Richmond, London |

| Location | |

Membership | 2500[49] |

Key people | Roger Hillyer, Chairman |

Main organ | Friends of Richmond Park newsletter (quarterly) |

Volunteers | 150 |

| Website | www |

The Friends of Richmond Park (FRP) was founded in 1961 to protect the park. In 1960 the speed limit in the park had been raised from 20 to 30 miles an hour and there were concerns that the roads in the park would be assigned to the main highway system as had recently happened in parts of Hyde Park.[50] In 1969, plans by the then Greater London Council to assign the park's roads to the national highway were revealed by the Friends and subsequently withdrawn.[51] The speed limit was reduced to 20 miles an hour in 2004.[52]

In 2011, the Friends successfully campaigned for the withdrawal of plans for open air screenings of films in the park.[53][54] In 2012, the Friends contributed towards the cost of a new Jubilee Pond, and launched a public appeal for a Ponds and Streams Conservation Programme in which the Friends, the Richmond Park Wildlife Group and Healthy Planet have been working with staff from The Royal Parks to restore some of the streams and ponds in the park.[55][56][57]

The Friends run a visitor centre near Pembroke Lodge, organise a programme of walks and education activities for young people, and produce a quarterly newsletter. The Friends have published two books, A Guide to Richmond Park and Family Trails in Richmond Park; profits from the books' sales contribute towards the Friends' conservation work.[58][59]

The Friends of Richmond Park has been a charitable organisation since 2009.[60] It has 2500 members,[49] is run by approximately 150 volunteers and has no staff.[60] Broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough, former Richmond Park MP Baroness Susan Kramer and broadcaster Clare Balding are patrons of FRP.[61] The chairman (from April 2021) is Roger Hillyer.[62]

History

Stuart origins

In 1625 Charles I brought his court to Richmond Palace to escape an outbreak of plague in London[63] and turned the area on the hill above Richmond into a park for the hunting of red and fallow deer.[63][64] It was originally referred to as the king's "New Park"[65] to distinguish it from the existing park in Richmond, which is now known as Old Deer Park. In 1637 he appointed Jerome Weston, 2nd Earl of Portland as keeper of the new park for life, with a fee of 12 (old) pence a day, pasture for four horses, and the use of the brushwood[66] – later holders of that office were known as "Ranger". Charles's decision, also in 1637, to enclose the land[nb 1] was not popular with the local residents, but he did allow pedestrians the right of way.[67] To this day the walls remain, although they have been partially rebuilt and reinforced. Following Charles I's execution, custodianship of the park passed to the Corporation of the City of London. It was returned to the restored monarch, Charles II, on his return to London in 1660.[68]

Georgian alterations

In 1719, Caroline of Ansbach and her husband, the future George II of Great Britain, bought Richmond Lodge as a country residence. This building had first been built as a hunting lodge for James I in 1619 and had also been occupied by William III.[69] As shown in a map of 1734, Richmond Park and Richmond Gardens then formed a single unit – the latter was merged with Kew Gardens by George III in the early 1800s.[70] In 1736 the Queen's Ride was cut through existing woodland to create a grand avenue through the park[71] and Bog Gate or Queen's Gate was opened as a private entrance for Caroline to enter the park on her journeys between White Lodge and Richmond Lodge. The same map shows Pen Ponds, a lake divided in two by a causeway, dug in 1746 and initially referred to as the Canals, which is now a good place to see water birds.[63][72] Richmond Lodge fell out of use on Caroline's death in 1737 but was brought back into use by her grandson George III as his summer residence from 1764 to 1772, when he switched his summer residence to Kew Palace and had Richmond Lodge demolished.[73]

In 1751, Caroline's daughter Princess Amelia became ranger of Richmond Park after the death of Robert Walpole. Immediately afterwards, the Princess caused major public uproar by closing the park to the public, only allowing a few close friends and those with special permits to enter.[74] This continued until 1758, when a local brewer, John Lewis, took the gatekeeper, who stopped him from entering the park, to court.[75] The court ruled in favour of Lewis, citing the fact that, when Charles I enclosed the park in the 17th century, he allowed the public right of way in the park. Princess Amelia was forced to lift the restrictions.[76][77]

19th century

Full right of public access to the park was confirmed by Act of Parliament in 1872.[78] However, people were no longer given the right to remove firewood; this is still the case and helps in preserving the park.[63]

Between 1833 and 1842 the Petersham Lodge estate, and then part of Sudbrook Park, were incorporated into Richmond Park. Terrace Walk was created from Richmond Gate to Pembroke Lodge.[79] The Russell School was built near Petersham Gate in 1851.[80] Between 1855 and 1861, new drainage improvements were constructed, including drinking points for deer.[81] In 1867 and 1876 fallow deer from the park were sent to New Zealand to help build up stocks – the first fallow deer introduced to that country[82][83] In or around 1870, the Inns of Court Rifle Volunteers were using an area near Bog Gate as a drill ground.[81] Giuseppe Garibaldi, Italian general and politician, visited Lord John Russell at Pembroke Lodge in 1864,[84] as did the Shah of Persia, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar in 1873. He was the first modern Iranian monarch to visit Europe.[84]

Early 20th century

Edward VII developed the park as a public amenity by opening up almost all the previously fenced woods and making public those gates that were previously private.[85] From 1915 level areas of the park were marked out for football and cricket pitches.[85] A golf course was developed on the former "Great Paddock" of Richmond Park, an area used for feeding deer for the royal hunt. The tree belt in this part of the park was supplemented by additional planting in 1936.[86] The public golf course was opened in 1923 by Edward, Prince of Wales[87] (who was to become King Edward VIII and, after his abdication, Duke of Windsor). The future king had been born in the park, at White Lodge, in 1894.[88] In 1925, a second public 18-hole course was laid out to the south of the first (towards Robin Hood Gate) it was opened by The Duke of York (George VI). In honour of their respective openers, Richmond Park Golf Course's two courses are named the "Prince's" and the "Duke's".

The park played an important role during World War I and was used for cavalry training.[89] On 7 December 1915 English inventor Harry Grindell Matthews demonstrated, in a secret test on Pen Ponds, how selenium cells would work in a remotely controlled prototype weapon for use against German Zeppelins.[90] Reporting on this story several years later, in April 1924, The Daily Chronicle reported that the test had been carried out in the presence of Arthur Balfour, Lord Fisher and a staff of experts. Its success led to Matthews receiving a payment of £25,000 from the Government the very next morning. Despite this large sum changing hands, the Admiralty never used the invention.[91] Between 1916 and 1925 the park housed a South African military war hospital, which was built between Bishop's Pond and Conduit Wood.[92][93] The hospital closed in 1921 and was demolished in 1925.[94] Richmond Cemetery, just outside the park, contains a section of war graves commemorating 39 soldiers who died at the hospital; the section is marked by a Cross of Sacrifice and a Grade II listed[95] cenotaph designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens.[96]

Faisal I of Iraq and Lebanese politician Salim Ali Salam were photographed visiting the park in 1925.

World War II

An army camp was established in 1938. It covered 45 acres (18 ha) to the south and east of Thatched House Lodge, extending to the area south of Dann's Pond.[97][98] It became known as Kingston Gate Camp and expanded the capacity of the East Surrey Regiment's regimental depot Infantry Training Centre (ITC). As a result the ITC was better able to meet the demands of training new recruits and called-up militia between early 1940 and August 1941 when the ITC transferred to a facility in Canterbury shared with the Buffs.[99] The camp was subsequently used as a military convalescent depot for up to 2,500 persons after which it continued as a base for the ATS until after the war.[100]

During World War II Pembroke Lodge was used as the base for "Phantom" (the GHQ Liaison Regiment).[97] The Pen Ponds were drained, in order to disguise them as a landmark,[101] and an experimental bomb disposal centre was set up at Killcat Corner, which is between Robin Hood Gate and Roehampton Gate.[102]

An anti-aircraft gun site was inside Sheen Gate for the duration of the war. The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, visited it on 10 November 1940[103] and it was featured in a photograph published in Picture Post on 13 December 1941.[104] Associated with the gun site was the research site of the Army Operational Research Group (AORG), located on the polo field beside Sheen Cross, where Stanley Hey researched improvements to the operation of anti-aircraft gun-laying radar. During the war, Hey discovered that the Sun is a radio source.[105]

In addition to use of the park for military purposes, approximately 500 acres (200 ha) of the park was converted to agricultural use during the war.[106]

The Russell School was destroyed by enemy action in 1943[107] and Sheen Cottage a year later.[108][109]

After World War II – present

From 1945 to 1947, Stanley Hey used the radar equipment on the AORG site on the Polo Field to investigate his wartime discoveries of astronomical radio sources: the Sun as a radio source, radio reflections from meteor trails, and radio noise from cosmic sources. In 1946 Hey's group discovered Cygnus A, later shown to be the first radio galaxy. The Richmond Park installation thus became the first radio observatory in Britain.[110]

John Boyd-Carpenter, MP for Kingston-upon-Thames, proposed using the Kingston Gate Camp to help alleviate the local post-war housing shortage but Minister of Works, Charles Key, was opposed, preferring that the site be eventually returned to its former parkland use.[111] Key's department refurbished and repurposed the camp as an Olympic Village for the 1948 Summer Olympics.[112][113][114] The Olympic Village was opened by Lord Burghley with Key making the announcement, in July 1948.[115] After the Olympics, the camp was used by units of the Royal Corps of Signals then by the Women's Royal Army Corps following their formation in 1949 as successor to the wartime ATS. Although it had been hoped to clear the camp during the 1950s, it remained in military use and was used to house service families repatriated following the Suez Crisis in 1956. It was not until 1965 that the camp was eventually demolished and reintegrated into the park during the following year.[100][106][116]

In 1953 President Tito of Yugoslavia stayed at White Lodge during a state visit to Britain.[117]

The Petersham Hole was a sink hole caused by subsidence of a sewer which forced the total closure of the A307 road in Petersham in 1979–80. As the hole and subsequent repair work had forced a total closure of this main road between Richmond and Kingston, traffic was diverted through the park and the Richmond, Ham, and Kingston gates remained open throughout the day and night. The park road was widened at Ham Cross near Ham Gate to accommodate temporary traffic lights. About 10 deer a month were killed by traffic while the diversion was in operation.[118]

When the present London Borough of Richmond upon Thames was created in 1965, it included the majority, but not the whole, of the park. The eastern tip, including Roehampton Gate, belonged to the London Borough of Wandsworth, and the southern tip belonged to the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. Following a series of borough boundary changes in 1994 and 1995, these anomalies were corrected and the whole park became part of Richmond upon Thames.[119]

In the 2012 Summer Olympics the men's and the women's cycling road races went through the park.[120]

Features

Boundary wall

The brick wall enclosing Richmond Park is eight miles (13 km) long and up to 9 ft (2.7m) high.[121] Much of the wall is designated by Historic England as a Grade II listed building.[122]

Gates

Six original gates

When the park was enclosed in 1637 there were six gates in the boundary wall: Coombe Gate, Ham Gate, Richmond Gate, Robin Hood Gate, Roehampton Gate and Sheen Gate. Of these, Richmond Gate has the heaviest traffic. The present gates were designed by Sir John Soane[123][124] and were widened in 1896.[125] Sheen Gate was where the brewer John Lewis asserted pedestrian right of entry in 1755 after Princess Amelia had denied it. The present double gates date from 1926.[125] Coombe Gate (later known as Ladderstile Gate) provided access to the park for the parishioners of Coombe, with both a gate and a step ladder. The gate was locked in the early 1700s and bricked up in about 1735. The stepladder was reinstated after John Lewis's case in 1758 and remained in place until about 1884. The present gate dates from 1901.[125] The present wrought iron gates of Roehampton Gate were installed in 1899.[125] Ham Gate was widened in 1921, when the present wrought iron gates were installed. The chinoiserie lantern lights over the gate were installed in 1825.[125]

Robin Hood Gate takes its name from the nearby Robin Hood Inn (demolished in 2001) and is close to what is called[126] the Robin Hood roundabout on the A3. Widened in 1907,[125] it has been closed to motorised vehicles since a 2003 traffic reduction trial.[127] Alterations commenced in March 2013 to make the gates more suitable for pedestrian use and return some of the hard surface to parkland.[128]

Other gates

Chohole Gate served the farm that stood within the park on the site of the present Kings Farm Plantation. It is first mentioned in 1680.[125] The gate now provides access to Richmond Park Golf Course.

Kingston Gate dates from about 1750. The existing gates date from 1898.[125]

Public access via Bog Gate or Queen's Gate (built in 1736), 24 hours a day, was granted in 1894 and the present "cradle" gate installed.[129] The gate connects the park with East Sheen Common.

Petersham Gate served the Russell School, replacing the more ornate gates to Petersham Lodge. A disused carriage gate further up the hill was probably a tradesman's entrance to the school or to the Lodge stables.[125]

Bishop's Gate in Chisholm Road, previously known as the Cattle Gate, was for use by livestock allowed to pasture in the nineteenth century. It was opened for public use in 1896.[125]

Kitchen Garden Gate, hidden behind Teck Plantation, is probably a nineteenth-century gate. It has never been open to the public.[129]

Cambrian Gate or Cambrian Road Gate[125] was constructed during World War I for access to the newly built South Africa Military Hospital.[94][130] When the hospital was demolished in 1925, the entrance was made permanent, with public access, as a pedestrian gate.[125]

Buildings

| |

| Formation | 1994[131] |

|---|---|

| Legal status | Registered charity[132] |

| Headquarters | Holly Lodge |

| Location |

|

Region served | Greater London and Surrey[132] |

Staff | Anna King (Centre Manager);[133] Sarah Allgrove (Education Centre Coordinator) |

Main organ | Stepping Stones (quarterly newsletter) |

Budget | £121,168[132] |

Staff | 2 |

Volunteers | 90 |

| Website | www |

The park includes a Grade I listed building, White Lodge. The boundary wall of the park is Grade II listed as are ten other buildings:[16][134] Ham Gate Lodge, built in 1742;[135] Holly Lodge (formerly known as Bog Lodge) and the game larder in its courtyard, built in 1735;[16][134] Pembroke Lodge; Richmond Gate and Richmond Gate Lodge, dated 1798 and designed by Sir John Soane;[136][123][137] Thatched House Lodge; and White Ash Lodge and its barns and stables, built in the 1730s or 1740s.[16][134][138][139]

The Freebord or "deer leap" is a strip of land 5 metres (16'6") wide, running around most of the perimeter of the park. Owned by the Crown, it allows access to the outside of the boundary wall for inspection and repairs. Householders whose property backs on to the park can use this land by paying an annual fee.[140][141]

Holly Lodge

In 1735, a new lodge, Cooper's Lodge, was built on the site of Hill Farm.[142] It was later known as Lucas's Lodge and as Bog Lodge.[142] Bog Lodge was renamed Holly Lodge in 1993[143] and now contains a visitors' centre (bookings only), the park's administrative headquarters and a base for the Metropolitan Police's Royal Parks Operational Command Unit.

Holly Lodge also includes the Holly Lodge Centre, an organisation which provides an opportunity for people of all ages and abilities to enjoy and learn from a series of hands-on experiences, focusing particularly on the environment and in the Victorian history and heritage of Richmond Park. The Centre, which is wheelchair-accessible throughout,[144] was opened in 1994.[131] It was founded by Mike Fitt OBE,[145][131] who was then The Royal Parks' Superintendent of Richmond Park and later became Deputy Chief Executive of London's Royal Parks. A registered charity,[132] the Holly Lodge Centre received the Queen's Award for Voluntary Service in 2005.

Princess Alexandra has been Holly Lodge Centre's Royal Patron since 2007.[145] In 2011 she opened the Centre's Victorian-themed pharmacy, Mr Palmer's Chymist. This includes the original interior, artefacts and dispensing records dating from 1865, from a chemist's shop in Mortlake, and is used for educational activities. The Centre also includes a replica Victorian schoolroom, and a kitchen garden planted with varieties of vegetables used in Victorian times and herbs cultivated for their medicinal properties.[144]

Pembroke Lodge

Pembroke Lodge and some associated houses stand in their own garden within the park. In 1847 Pembroke Lodge became the home of the then Prime Minister, Lord John Russell and was later the childhood home of his grandson, Bertrand Russell. It is now a popular restaurant with views across the Thames Valley.

Thatched House Lodge

Thatched House Lodge was the London home of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower during the Second World War. Since 1963 it has been the residence of Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy. The residence was originally built as two houses in 1673 for two Richmond Park Keepers, as Aldridge Lodge. Enlarged in 1727, the two houses were joined and renamed Thatched House Lodge in 1771 by Sir John Soane. The gardens include an 18th-century two-room thatched summer house which gave the main house its name.

White Lodge

Built as a hunting lodge for George II by the architect Roger Morris, White Lodge was completed in 1730. Its many famous residents have included members of the Royal Family. The future Edward VIII was born at White Lodge in 1894[146] and his brother Prince Albert, Duke of York (the future George VI), and the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother), lived there in the 1920s. The Royal Ballet School (formerly Sadler's Wells Ballet) has been based since 1955[112] at White Lodge where younger ballet students continue to be trained.

Bishop's Gate Lodge

Bishop's Gate Lodge takes its name from a gamekeeper who was on the staff in the first half of the 19th century. A reference dated 1854 said that the keeper had had access to the lodge for the past fifty years. The lodge does not appear, though, on the 1813 plan of the park, but appears on the plans of 1850, and its layout seems to have changed little from that time. It forms part of a view over the park, and beyond, that is much favoured by amateur painters.[147]

Other buildings

Oak Lodge, near Sidmouth Wood, was built in about 1852 as a home for the park bailiff, who was responsible for repair and maintenance in the park.[148] It is used by The Royal Parks as its base for a similar function today.[148]

There are also gate lodges at Chohole Gate, Kingston Gate, Robin Hood Gate, Roehampton Gate[149] and at Sheen Gate, which also has a bungalow (Sheen Gate Bungalow).[150] Ladderstile Cottage, at Ladderstile Gate, was built in the 1780s.[151]

Former buildings

A map by John Eyre, "Plan of His Majesty's New Park", shows a summerhouse near Richmond Gate.[65]

Several buildings already existed within the park when it was created. One of these was a manor house at Petersham which was renamed Petersham Lodge. During the Commonwealth period it became accommodation for one of the park's deputy keepers, Lodowick Carlell (or Carlile), who was also a renowned playwright in his day,[152] and his wife, Joan Carlile, one of the first women to practise painting professionally.[153]

Elizabeth, Countess of Dysart, and her husband Sir Lionel Tollemache, took over Petersham Lodge when they became joint keepers of Richmond Park. After Tollemache's death the Lodge and its surrounding land were leased in 1686 to Lawrence Hyde, Earl of Rochester, whose sister Anne was married to the new king, James II. It became a private park and was subsequently landscaped. By 1692 Rochester had demolished the Lodge and replaced it with a splendid new mansion in his "New Park". In 1732, a new Petersham Lodge was built to replace it after a fire.[154] This Petersham Lodge was demolished in 1835.[79]

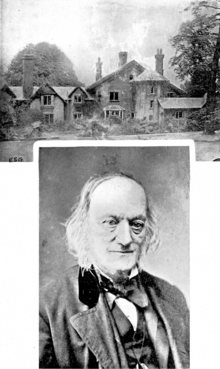

Professor Sir Richard Owen, the first Director of the Natural History Museum, lived at Sheen Cottage until his death in 1892.[109][155] The cottage was destroyed by enemy action in 1944.[109][156] The remains of the cottage can be seen in patches and irregularities in the wall 220 metres from Sheen Gate.[109][151]

A bandstand, similar to one in Kensington Gardens, was erected near Richmond Gate in 1931. In 1975, after many years of disuse, it was moved to Regent's Park.[157]

Viewpoints

There is a protected view of St Paul's Cathedral from King Henry's Mound, and also from Sawyer's Hill a view of central London in which the London Eye, Tower 42 (formerly the NatWest Tower) and 30 St Mary Axe ("The Gherkin") appear to be close to one another.[158]

King Henry's Mound

King Henry's Mound, which may have been a Neolithic burial barrow,[159][160] was listed in 2020 by Historic England[3] along with another (unnamed) mound in the park which could be a long barrow.[4][5][6] King Henry's Mound is located within the public gardens of Pembroke Lodge. At various times the mound's name has been connected with Henry VIII or with his father Henry VII.[159] However, there is no evidence to support the legend that Henry VIII stood on the mound to watch for a sign from St Paul's that Anne Boleyn had been executed at the Tower and that he was then free to marry Jane Seymour.[159]

To the west of King Henry's Mound is a panorama of the Thames Valley.[158] St Paul's Cathedral, over 10 miles (16 km) to the east, can be seen through the naked eye or via a telescope that has been installed on the Mound. This vista, created soon after the cathedral was completed in 1710,[161] is protected by a "dome and a half" width of sky on either side. In 2005 the then Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, sought to overturn this protection and reduce it to "half a dome". In 2009 his successor, Boris Johnson, promised to reinstate the wider view, though also approving a development at Victoria Station which, when completed, will obscure its right-hand corner.[162] New gates − "The Way" − which can be viewed through the King Henry's Mound telescope, were installed in 2012 on the edge of Sidmouth Wood to mark the 300th anniversary of St Paul's.[163]

In December 2016, it was reported that Manhattan Loft Gardens, a 42-storey 135m-tall apartment building under construction in Stratford, an area of London not covered by these planning restrictions, had "destroyed" the view from the park as it can now be seen behind the framed view of the cathedral's dome. The developers said that “Despite going through the correct planning processes in a public and transparent manner, at no point was the subject of visual impact to St Paul’s ever raised" by the Olympic Delivery Authority or the Greater London Authority and that they were looking into the issues raised by the development.[164]

In November 2017, the Friends of Richmond Park reported that their campaigning on the issue had resulted in the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, instructing London planners to consult the Greater London Authority on planning requests for high-rise buildings which, if built, could affect the visibility of St Paul's from established viewpoints. His instruction has now been incorporated into planning procedures across Greater London.[165]

Plantings and memorials

The park's open slopes and woods are based on lowland acid soils. The grassland is mostly managed by grazing. The park contains numerous woods and copses, some created with donations from members of the public.

Between 1819 and 1835, Lord Sidmouth, Deputy Ranger, established several new plantations and enclosures, including Sidmouth Wood and the ornamental Isabella Plantation, both of which are fenced to keep the deer out.[63][81] After World War II the existing woodland at Isabella Plantation was transformed into a woodland garden, and is organically run, resulting in a rich flora and fauna. Opened to the public in 1953,[166] it is now a major visitor attraction in its own right. It is best known for the flowering, in April and May, of its evergreen azaleas and camellias, which have been planted next to its ponds and streams. There are also many rare and unusual trees and shrubs.[167]

The Jubilee Plantation, created to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, was established in 1887.[168] Prince Charles' Spinney was planted out in 1951[169] with trees protected from the deer by fences, to preserve a natural habitat. The bluebell glade is managed to encourage native British bluebells. Teck Plantation, established in 1905,[170] commemorates the Duke and Duchess of Teck, who lived at White Lodge. Their daughter Mary married George V.[129] Tercentenary Plantation, in 1937,[170] marked the 300th anniversary of the enclosure of the park. Victory Plantation was established in 1946[170] to mark the end of the Second World War. Queen Mother's Copse, a small triangular enclosure on the woodland hill halfway between Robin Hood Gate and Ham Gate, was established in 1980[170] to commemorate the 80th birthday of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.

The park lost over 1000 mature trees during the Great Storm of 1987 and the Burns' Day Storm of 1990. The subsequent replanting included a new plantation, Two Storms Wood, a short distance into the park from Sheen Gate. Some extremely old trees can also be seen inside this enclosure.[18]

Bone Copse, which was named in 2005, was started by the Bone family in 1988 by purchasing and planting a tree from the park authorities in memory of Bessie Bone who died in that year. Trees have been added annually, and in 1994 her husband Frederick Bone also died. The annual planting has been continued by their children.

James Thomson and Poet's Corner

Poet's Corner, an area at the north end of Pembroke Lodge Gardens, commemorates the poet James Thomson (1700–1748), who was living in Richmond at the time of his death. A bench inscribed with lines by Thomson and known as "Poet's seat" is located there. Sculpted by Richard Farrington, it was based on an idea by Jane Fowles.[171][172]

A wooden memorial plaque with an ode to Thomson by the writer and historian John Heneage Jesse was formerly located near Pembroke Lodge stables, where it was installed in 1851. The plaque was replaced by the Selborne Society in 1895.[172]

In 2014 Poet's Corner was re-sited to the other side of the main path and the ode, on a re-gilded board, was installed in a completely new oak frame. The new Poet's Corner, funded by the Friends of Richmond Park and the Visitor Centre at Pembroke Lodge, and by a donation in memory of Wendy Vachell, also includes three curved benches made from reclaimed teak. The benches are inscribed with a couplet by the Welsh poet W. H. Davies, "A poor life this, if, full of care, we have no time to stand and stare".[173]

King Henry's Mound is inscribed with a few lines from Thomson's poem "The Seasons".[172]

Poet's Corner is linked to King Henry's Mound by The John Beer Laburnum Arch, named after one of Pembroke Lodge Gardens' former charge-hands. The arch has a display of yellow laburnum flowers in May.[174]

Ian Dury

In 2002 a "musical bench", designed by Mil Stricevic,[175] was placed in a favoured viewing spot of rock singer and lyricist Ian Dury (1942–2000) near Poet's Corner. On the back of the bench are the words "Reasons to be cheerful", the title of one of Dury's songs.[172] The solar powered seat was intended to allow visitors to plug in and listen to eight of his songs as well as an interview, but was subjected to repeated vandalism.[176] In 2015 the bench was refurbished and the MP3 players and solar panels were replaced with metal plates on which a QR code can be scanned via a smartphone. Visitors can access nine Ian Dury and the Blockheads songs and hear Dury's Desert Island Discs interview with Sue Lawley, first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 15 December 1996.[177]

Nature

Wildlife

Originally created for deer hunting, Richmond Park now has 630 red and fallow deer[178] that roam freely within much of the park. A cull takes place each November and February to ensure numbers can be sustained;[179] about 200 deer are culled annually and the meat is sold to licensed game dealers.[180][181] Some deer are also killed in road accidents, through ingesting litter such as small items of plastic, or by dogs. Many of the deer in Richmond Park are infected with a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi which can be transmitted to humans through a tick bite, causing Lyme disease.[182]

The park is an important refuge for other wildlife, including woodpeckers, squirrels, rabbits, snakes, frogs, toads, stag beetles and many other insects plus numerous ancient trees and varieties of fungi. It is particularly notable for its rare beetles.[14]

Richmond Park supports a large population of what are believed to be ring-necked (or rose-ringed) parakeets. These bred from birds that escaped or were freed from captivity.[183]

Ponds and streams

There are about 30 ponds in the park. Some – including Barn Wood Pond, Bishop's Pond, Gallows Pond, Leg of Mutton Pond, Martin's Pond and White Ash Pond – have been created to drain the land or to provide water for livestock. The Pen Ponds (which in the past were used to rear carp for food)[184] date from 1746.[63] They were formed when a trench was dug in the early 17th century to drain a boggy area; later in that century this was widened and deepened by the extraction of gravel for local building. The Ponds now take in water from streams flowing from the higher ground around them and release it to Beverley Brook. Beverley Brook and the two Pen Ponds are most visible areas of water in the park.[185]

Beverley Brook rises at Cuddington Recreation Ground in Worcester Park[186] and enters the park (where it is followed by the Tamsin Trail and Beverley Walk) at Robin Hood Gate, creating a water feature used by deer, smaller animals and water grasses and some water lilies. Its name is derived from the former presence in the river of the European beaver (Castor fiber),[187] a species extinct in Britain since the 16th century.[188]

Most of the streams in the park drain into Beverley Brook but a spring above Dann's Pond flows to join Sudbrook (from "South brook") on the park boundary. Sudbrook flows through a small valley known as Ham Dip and has been dammed and enlarged in two places to form Ham Dip Pond and Ham Gate Pond, first mapped in 1861 and 1754 respectively. These were created for the watering of deer.[189] Both ponds underwent restoration work including de-silting, which was completed in 2013.[190] Sudbrook drains the western escarpment of the hill that, to the east, forms part of the catchment of Beverley Brook and, to the south, the Hogsmill River. Sudbrook is joined by the Latchmere Stream just beyond Ham Gate Pond. Sudbrook then flows into Sudbrook Park, Petersham. Another stream rises north of Sidmouth Wood and goes through Conduit Wood towards the park boundary near Bog Gate.[185]

A separate water system for Isabella Plantation was developed in the 1950s. Water from the upper Pen Pond is pumped to Still Pond, Thomson's Pond and Peg's Pond.[185]

The park's newest pond is Attenborough Pond, opened by and named after the broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough in July 2014.[191] It was created as part of the park's Ponds and Streams Conservation Programme.[192]

In culture

The Hearsum Collection

| |

| Formation | 2013 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Daniel Hearsum (1958–2021)[193] |

| Registration no. | 1153010 |

| Legal status | Registered charity |

| Headquarters | Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park |

| Location |

|

Chair (2013–2021) | Daniel Hearsum |

| Website | hearsumcollection |

The Hearsum Collection is a registered charity[nb 2] that collects and preserves the heritage of Richmond Park. It has a collection, which was started by the late Daniel Hearsum in 1997,[194] of heritage material covering the last four centuries, with over 5000 items including antique prints, paintings,[195] maps, postcards, photographs, documents, books and press cuttings. Volunteers from the Friends of Richmond Park have been cataloguing them.[195] The Collection, which as of 2021 continues to be stored in unsatisfactory accommodation in Pembroke Lodge,[196] is overseen by volunteers and part-time staff. The trustees announced in 2014 plans for a new purpose-built heritage centre to provide full public access to the Collection.[196][197][198][199]

In April 2017 the Collection, in collaboration with The Royal Parks and Ireland's Office of Public Works, mounted an exhibition at Dublin's Phoenix Park entitled Parks, Our Shared Heritage: The Phoenix Park, Dublin & The Royal Parks, London, demonstrating the historical links between Richmond Park (and other Royal Parks in London) and Phoenix Park.[200] This exhibition was also displayed at the Mall Galleries in London in July and August 2017.[201]

Literature

Fiction

Chapter 22 of George MacDonald's novel The Marquis of Lossie (published in London in 1877 by Hurst and Blackett)[202] is entitled "Richmond Park".[203]

In Georgette Heyer's Regency romance Sylvester, or the Wicked Uncle (1957) there is an expedition to Richmond Park.[204]

Isabella Plantation in Richmond Park is the scene of a picnic and a child's disappearance in chapters 9 and 10 of Chris Cleave's 2008 novel The Other Hand.[205] Richmond Park features in Jacqueline Wilson's novel Lily Alone (2010) and in the poetry anthology she edited, Green Glass Beads (2011).[206]

Novelist Shena Mackay was commissioned by The Royal Parks to write a short story about Richmond Park named The Running of the Deer which was published in 2009.[207][208]

Anthony Horowitz's 2014 novel Moriarty, about Arthur Conan Doyle's character in his Sherlock Holmes stories, includes a scene set in Richmond Park.[209]

Non-fiction

A Hind in Richmond Park by William Henry Hudson, published in 1922 and republished in 2006, is an extended natural history essay. It includes an account of his visits to Richmond Park and a particular occasion when a young girl was struck by a red deer when she tried to feed it an acorn.[210]

Art

17th century

The oil painting The Carlile Family with Sir Justinian Isham in Richmond Park is held at Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire.[211] It was painted by Joan Carlile (1600–1679) who lived at Petersham Lodge.[153]

18th and 19th centuries

A portrait by T Stewart (a pupil of Sir Joshua Reynolds) in 1758 of John Lewis, Brewer of Richmond, Surrey, whose legal action forced Princess Amelia to reinstate pedestrian access to the park, is in the Richmond upon Thames Borough Art Collection. It is on display in Richmond Reference Library.[212]

Joseph Allen's Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745), 1st Earl of Orford, KG, as Ranger of Richmond Park (after Jonathan Richardson the Elder) is in the collection of the National Trust, and is held at Erddig, Wrexham.[213] The painting is based on a portrait with a similar title, by Jonathan Richardson the Elder and John Wootton, which is held at Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.[214]

Artist and caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)'s drawing Richmond Park is at the Yale Center for British Art.[215]

The Earl of Dysart's Family in Richmond Park by William Frederick Witherington (1785–1865) is in The Hearsum Collection at Pembroke Lodge.[216]

Landscape: View in Richmond Park was painted in 1850 by the English Romantic painter John Martin. It is held at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.[217]

William Bennett's watercolour In Richmond Park, painted in 1852, is held by Tate Britain. It can be viewed, by appointment, at its Prints and Drawings Rooms.[218]

The oil painting In Richmond Park (1856) by the Victorian painter Henry Moore is in the collection of the York Museums Trust.[219][220]

Landscape with Deer, Richmond Park (1875) by Alfred Dawson is in the Reading Museum's collection.[221]

John Buxton Knight's White Lodge, Richmond Park, painted in 1898, is in the collection of Leeds Museums and Galleries.[222]

20th and 21st centuries

The oil painting Richmond Park (1913) by Arthur George Bell is in the collection of the London Transport Museum.[223]

Spencer Gore's painting Richmond Park, thought to have been painted in the autumn of 1913 or shortly before the artist's death in March 1914, was exhibited at the Paterson and Carfax Gallery[224] in 1920. In 1939 it was exhibited in Warsaw, Helsingfors and Stockholm by the British Council as Group of Trees.[225] It is now in the collection of the Tate Gallery under its original title but is not currently on display.[225] The painting is one of a series of landscapes painted in Richmond Park during the last months of Gore's life.[226] According to Tate curator Helena Bonett, Gore's early death from pneumonia, two months before what would have been his 36th birthday, was brought on by his painting outdoors in Richmond Park in the cold and wet winter months.[227] It is not certain where in the park the picture was made but a row of trees close to the pond near Cambrian Gate has a very close resemblance to those in the painting.[228] Another Gore painting, with the same title (Richmond Park), painted in 1914, is at the Ashmolean Museum. His painting Wood in Richmond Park is in the Birmingham Art Gallery's collection.[229]

The oil painting Autumn, Richmond Park by Alfred James Munnings is at the Sir Alfred Munnings Art Museum in Colchester.[230]

Chinese artist Chiang Yee wrote and illustrated several books while living in Britain. Deer in Richmond Park is Plate V in his book The Silent Traveller in London, published in 1938.[231]

Trees, Richmond Park, Surrey, painted in 1938 by Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook, is in the Manchester Art Gallery's collection.[232]

Richmond Park No 2 by the English Impressionist painter Laura Knight is at the Royal Academy of Arts.[233]

In Richmond Park (1962) by James Andrew Wykeham Simons is at the UCL Art Museum at University College London.[234]

Kenneth Armitage (1916–2002) made a series of sculptures and drawings of oak trees in Richmond Park between 1975 and 1986.[235] His collage and etching Richmond Park: Tall Figure with Jerky Arms (1981) is in the British Government Art Collection and is on display at the British Embassy in Prague.[236] The Government Art Collection also holds his Richmond Park: Two Trees with White Trunks (1975),[237] Richmond Park: Five Trees, Grey Sky (1979)[238] and his sculpture Richmond Oak (1985–86).[239]

Richmond Park Morning, London (2004) by Bob Rankin is at Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton,[240] which also holds a panel of five oil paintings by Yvonne Fletcher entitled Richmond Park, London (2005–06).[241]

Historic posters

The Underground Electric Railways Company published, in 1911, a poster, Richmond Park, designed by Charles Sharland. This is at the London Transport Museum,[242] which also has: a District line poster from 1908, Richmond Park for pleasure and fresh air, by an unknown artist;[243] Richmond Park, by an unknown artist (1910);[244] Richmond by Underground, by Alfred France (1910);[245] Richmond Park, by Arthur G Bell (1913);[246] Richmond Park; humours no. 10 by German American puppeteer and illustrator Tony Sarg (1913);[247] Richmond Park by tram, by Charles Sharland (1913);[248] Richmond Park, by Harold L Oakley (1914);[249] Natural history of London; no. 3, herons at Richmond Park, by Edwin Noble (1916);[250] Richmond Park by Emilio Camilio Leopoldo Tafani (1920);[251] Rambles in Richmond Park, by Freda Lingstrom (1924);[252] Richmond Park by Charles Paine (1925);[253] and Richmond Park, a poster commissioned by London Transport in 1938 and illustrated by the artist Dame Laura Knight.[254]

Film

Richmond Park has been a location for several films and TV series:

- A locomotive runs through the park and crashes into a tree in the Ealing Studios comedy film The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).[255]

- In the 1968 film Performance, James Fox crosses Richmond Park in a Rolls Royce car.[255]

- The park was the backdrop for the classic historical film Anne of the Thousand Days (1969),[256] with Richard Burton and Geneviève Bujold, which looks back to what is now Richmond in the 16th century. The film tells the story of King Henry VIII's courtship of Anne Boleyn and their brief marriage.

- An Indian dust storm was filmed in the park for the film Heat and Dust (1983).[255]

- The Royal Ballet School in Richmond Park featured in the film Billy Elliot (2000).[255][257]

- In 2010, director Guy Ritchie filmed parts of Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011) in the park with Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law.[258]

- Some of the scenes from Into the Woods (2014), the Disney fantasy film featuring Meryl Streep,[259] were filmed in the park.[260][261]

- Richmond Park was the setting for some scenes in the 2018 family comedy film Patrick.[262][263]

As well as a location for films, Richmond Park is regularly featured in television programmes, corporate videos and fashion shoots. It has made an appearance on Blue Peter, Inside Out (the BBC regional current affairs programme) and Springwatch (the BBC natural history series).[256] In 2014 it was featured in a video commissioned by The Hearsum Collection.[196] Most recently it was the subject of nature documentary Richmond Park – National Nature Reserve, presented by Sir David Attenborough and produced by the Friends of Richmond Park, which has won the best "Longform" film in the 2018 national Charity Film Awards.[264][265]

International connections

Richmond Park, Brunswick, Germany

The "Richmond Park" in Germany is named after the park in Britain and was created in 1768 in Brunswick for Princess Augusta, sister of George III. She was married to the Duke of Brunswick and was feeling homesick, so an English-style park was designed by Lancelot "Capability" Brown and a palace built for her, both with the name "Richmond".[266][267]

In 1935, the palace including the entire estate was purchased by the City of Braunschweig. One condition for the purchase was that no structural changes ever be made and the park not be built on. The palace, which was rebuilt after the Second World War and reconstructed in 1987 to the historic original design, is now used for public events.[267] The nearly four-hectare (10 acre) park has been open to the public since 1964.

See also

- East Sheen Common

- Pesthouse Common, Richmond

- Richmond Cemetery

- Richmond Park Golf Course

- Sudbrook Park, Petersham

- List of National Nature Reserves in England

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Greater London

- Parks, open spaces and nature reserves in Richmond upon Thames

Notes

- ^ An Ordnance Survey map, published in 1949 and now held at The National Archives (UK), shows contemporary features in Richmond Park alongside the place names and field boundaries that existed prior to the 1637 Enclosure Act.

"Richmond Park: field boundaries before Enclosure Act 1637". ZOS 5/5. The National Archives (UK). 1949. Retrieved 27 June 2017. - ^ Its charity registration number is 1153010. "The Hearsum Collection". Open Charities. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

References

- ^ a b c d Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster. "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 7 Feb 2002 (pt 18)". UK Parliament. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Historic England (2015). "Richmond Park (397979)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ a b Historic England (27 May 2020). "King Henry VIII's Mound, Richmond Park (1457267)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England (16 March 2020). "Mound at TQ1891972117, Richmond Park (1457269)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Ancient Burial Mounds in London's Richmond Park Protected" (Press release). Historic England. 31 May 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b "King Henry VIII's Mound protected as scheduled monument". BBC News. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Our parks". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ "Bois de Vincennes. Chateau. Zoo". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Dominique Jarrassé (2007). Grammaire des jardins Parisiens (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 9782840964766. OL 21422234M.

- ^ Instituto Geográfico Nacional (Spain). "Visor cartográfico Iberpix". Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". CentralPark.com. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Map of Richmond Park SSSI". Natural England.

- ^ a b c "Richmond Park" (PDF). Citation. Natural England. 1992. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b "London National Nature Reserves". Natural England. 2 August 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Richmond Park". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Strategic Framework" (PDF). Richmond Park Management Plan. The Royal Parks. January 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Richmond Park". SAC selection. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b Historic England (1 October 1987). "Richmond Park (1000828)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "Royal Parks Board". Greater London Authority. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Ron Crompton & Pieter Morpurgo (19 October 2011). "Letter to Sir Edward Lister, Deputy Mayor of London, re Royal Parks Board" (PDF). Richmond and Bushy Parks Forum. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Responsibility for London's Royal Parks to pass to London's Mayor". Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ "New Board for Royal Parks". Friends of Richmond Park. October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Royal Parks Board appointed". Friends of Richmond Park. July 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Number of visitors to Royal Parks in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2014, by park (in millions)". Statista. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "The Royal Parks and Other Open Spaces Regulations 1997". Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Seasonal Bus Service". Richmond Park Visitor Information. The Royal Parks. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Richmond Park map" (PDF). The Royal Parks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Getting to the Park" (PDF). Richmond Park Management Plan. The Royal Parks. January 2008. p. 10. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Opening times and getting here". Visitor information. The Royal Parks. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "The Royal Parks' traffic reduction measures to remain in place for another year". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Beverley Brook Walk" (PDF). London Borough of Merton. 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Cycling in the Royal Parks". Managing the parks. The Royal Parks. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Tamsin Trail at Richmond Park". Sustrans. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "Sustrans NCN Route 4". Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Jasper Copping (10 June 2012). "Watch out Fenton! Richmond Park deers take on dogs". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ "Richmond Park dogwalkers chased by protective deer". BBC News. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Baxter Brown, p. 115

- ^ "Policing in the Royal Parks". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ "Bad news on policing". News. Friends of Richmond Park. 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Park to bring in bad behaviour penalties". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 13 July 2012. p. 7.

- ^ Amy Dyduch (19 September 2012). "Fine for man who allowed dogs to chase ducks in Richmond Park". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "About the Professional Dog Walking Licence". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Clare Buchanan (18 September 2013). "Speeding fine for teenager doing 37mph on bicycle". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Josh Pettitt & Matt Watts (12 March 2015). "Speeding cyclist who reached 40mph in Richmond Park faces expulsion from top club". Evening Standard. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Laura Proto (27 January 2015). "Mushroom tamperer gets conditional discharge after Richmond Park picking". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Laura Proto (9 December 2014). "Mushroom thief fined after picking in Richmond Park". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Sports and leisure". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Richmond parkrun – Weekly Free 5km Timed Run". Richmond parkrun. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ a b "About the Friends of Richmond Park". Friends of Richmond Park. 27 August 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, pp. 2–3

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, p. 9

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, p. 33

- ^ Paul Teed (11 August 2011). "Richmond Park cinema plans withdrawn". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ "Friends oppose Park screenings". Friends of Richmond Park website. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "New Jubilee Pond in Richmond Park to be Created". St Margarets Community website. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Christine Fleming (10 May 2012). "Jubilee pond to open in Richmond Park". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Work starts on more ponds". Friends of Richmond Park. 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "New guide book to Richmond Park". London Borough of Wandsworth. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ June Sampson (2 September 2011). "Trails give us thrill of discovery" (PDF). Surrey Comet. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ a b Christine Fleming (25 March 2011). "Friends of Richmond Park to mark 50 years of protecting the green space". Wandsworth Guardian. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Christine Fleming (3 April 2011). "Sir David Attenborough steps up as Friends of Richmond Park marks golden anniversary". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Contact". Friends of Richmond Park. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Richmond Park: Landscape History". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "About the Park: History". The Friends of Richmond Park. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b ref MPE 1/426. The National Archives (UK).

- ^ William Douglas Hamilton, ed. (1888). Calendar of State Papers, Domestic series, of the reign of Charles I, 1644, preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office. London: HMSO. p. 234.

- ^ H E Malden (1911). "A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 3". Victoria County History. British History Online. pp. 533–546. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ McDowall, p. 51

- ^ Susanne Groom and Lee Prosser (2006). Kew Palace: The Official Illustrated History. Merrell Publishers. pp. 26–40. ISBN 978-1858943237.

- ^ John Rocque. "Plan of the House, Gardens, Park & Hermitage of their Majesties, at Richmond 1734". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Michael Davison (2011). "Buildings" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ Baxter Brown, p. 51

- ^ Susanne Groom and Lee Prosser (2006). Kew Palace: The Official Illustrated History. Merrell Publishers. pp. 72–81. ISBN 978-1858943237.

- ^ Kenneth J. Panton (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5779-7. p. 45

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, p. 38

- ^ "A Park Milestone Celebrated". Friends of Richmond Park. 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Max Lankester, Friends of Richmond Park (September 2009). "John Lewis' re-establishment of pedestrian access to Richmond Park" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Max Lankester (2011). "History" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ a b Cloake, p. 190

- ^ Max Lankester (2011). "History" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ a b c Cloake, p. 196

- ^ A H C Christie & J R H Andrews (July 1966). "Introduced ungulates in New Zealand – (D) Fallow deer". Tuatara. 14 (2): 84. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Baxter Brown, p. 118

- ^ a b Cloake, p. 192

- ^ a b McDowall, p. 90

- ^ McDowall, pp. 121–126

- ^ Baxter Brown, p. 150

- ^ Pamela Fletcher Jones (1972). Richmond Park: Portrait of a Royal Playground. Phillimore & Co Ltd. p. 36. ISBN 978-0850334975.

- ^ Mary Pollard & Robert Wood (17 November 2014). "Richmond Park and the First World War" (PDF). Friend of Richmond Park Newsletter. Friends of Richmond Park. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Jonathan Foster (2008). "Remote Controlled Boat". The Death Ray: The Secret Life of Harry Grindell Matthews. Jonathan Foster. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Foster (2009). The Death Ray: The Secret Life of Harry Grindell Matthews. Inventive Publishing. ISBN 978-0956134806.

- ^ McDowall, pp. 95–96

- ^ "South African Military Hospital". Lost Hospitals of London. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ a b "The First World War and Richmond Park". The Hearsum Collection. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Historic England (24 July 2012). "South African War Memorial (1409475)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Richmond Park, London: The South African Military Hospital". World War One At Home. BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ a b Max Lankester (2011). "History" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ Kingston Gate Camp (Map). 1:1,250–1:2,500. National Grid maps, 1940s-1960s. Richmond Park: Ordnance Survey. 1959. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ David Scott Daniell (1957). The History of the East Surrey Regiment. Vol. IV 1920–1952. London: Ernest Benn Limited. pp. 115–116. OCLC 492800784.

- ^ a b Rabbitts 2014, p. 145

- ^ McDowall, p. 91

- ^ Mike Osborne (2012). Defending London: A Military History from Conquest to Cold War. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-07524-7930-9.

- ^ Simon Fowler (October 2020). "Winston Churchill in Richmond". Richmond Local History Society. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Compiled by members of the Richmond Local History Society (1990). John Cloake (ed.). Richmond in Old Photographs. Alan Sutton Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-86299-855-4.

- ^ Timothy M M Baker (October 2021). "Richmond Park, radio astronomy's birthplace". Richmond History. 42. Richmond Local History Society: 22–27. ISSN 0263-0958.

- ^ a b "Richmond Park (Closed Area)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 3 July 1950. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ McDowall, p. 97

- ^ McDowall, p. 95

- ^ a b c d Robert Wood (June 2019). "A house through time". Richmond History. 40. Richmond Local History Society: 34–42. ISSN 0263-0958.

- ^ Baker, Timothy M. M. (October 2021). "Richmond Park, radio astronomy's birthplace". Richmond History. Richmond Local History Society. 42: 22–27. ISSN 0263-0958.

- ^ "Richmond Park Camp (Use)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 6 November 1947. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ a b Cloake, p. 201

- ^ "Olympic Town at Richmond Park". BBC News. 4 June 1948. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "The XIVth Olympiad". The Sphere. British Newspaper Archive. 31 July 1948.

- ^ Opening Of Olympic Centre In London 1948 (Motion picture, black and white). Gaumont British Newsreel. Reuters. 5 July 1948. film id:VLVA354L6FHKU412LLQ9JN7WB90IO. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Davison, Michael (July 2005). "When the Olympics Came to Richmond Park" (PDF). Mastermind Club. pp. 11–12.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. 2011. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, pp.11–12

- ^ "The Greater London and Surrey (County and London Borough Boundaries) (No. 2) Order 1993". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Barry Glendenning (29 July 2012). "Olympic road race: women's cycling – as it happened". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Michael Davison (2011). "Buildings" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 103. ISBN 978-0952784708.

- ^ Historic England (6 October 1983). "Boundary walls to Richmond Park, section to south west of Kingston Place (1358450)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Gate design credited to Soane". Friends of Richmond Park. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Historic England (10 January 1950). "Richmond Gate Lodge, Screen Walls, Gate Piers and Gates (1263361)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McDowall, pp. 71–78

- ^ Nigel Cox. "A3 Robin Hood Roundabout". Geograph. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Juliet Ayward (10 June 2003). "Park blocks scenic rat run". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "The Park in March". March Park diaries. Friends of Richmond Park. March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ a b c McDowall, p. 70

- ^ Cloake, p. 198

- ^ a b c "Famous faces celebrate 20 years of the Holly Lodge Centre in Richmond Park" (Press release). The Royal Parks. 19 August 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d "1076741 – Holly Lodge Centre". Find charities. Charity Commission. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Changes at Holly Lodge Centre". Friends of Richmond Park Newsletter: 6. Autumn 2013.

- ^ a b c "Listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Cloake, p. 108

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, p. 42

- ^ Historic England (10 January 1950). "Richmond Gate Lodge, Screen Walls, Gate Piers and Gates (1263361)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Michael Davison (2011). "Buildings" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 100. ISBN 978-0952784708.

- ^ Historic England (30 January 1976). "White Ash Lodge (1250204)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Public Access" (PDF). Richmond Park Management Plan. The Royal Parks. January 2008. p. 11. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Robert Wood. "The "Deer Leap" of Richmond Park". Richmond Local History Society. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Michael Davison (2011). "Buildings" in Guide to Richmond Park. Friends of Richmond Park. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-9567469-0-0.

- ^ Pollard and Crompton, p. 22

- ^ a b "Facilities available". About us. Holly Lodge Centre. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Who we are". About us. Holly Lodge Centre. Retrieved 8 June 2020.