Osaka: Difference between revisions

→Municipal subway: DEAD LINK |

|||

| Line 508: | Line 508: | ||

==== Municipal subway ==== |

==== Municipal subway ==== |

||

[[File:Wide-Area Map of Osaka City Subway.png|thumb|right|Osaka subway map]] |

[[File:Wide-Area Map of Osaka City Subway.png|thumb|right|Osaka subway map]] |

||

The [[Osaka Municipal Subway]] system is a part of Osaka's extensive rapid transit system. The metro system alone ranks 8th in the world by annual passenger ridership, serving over 912 million people annually (a quarter of Greater Osaka Rail System's 4 billion annual riders), despite being only 8 of more than 70 lines in the metro area |

The [[Osaka Municipal Subway]] system is a part of Osaka's extensive rapid transit system. The metro system alone ranks 8th in the world by annual passenger ridership, serving over 912 million people annually (a quarter of Greater Osaka Rail System's 4 billion annual riders), despite being only 8 of more than 70 lines in the metro area. |

||

=== Bus === |

=== Bus === |

||

Revision as of 13:17, 11 June 2012

Osaka

大阪 | |

|---|---|

| 大阪市 · Osaka City | |

| |

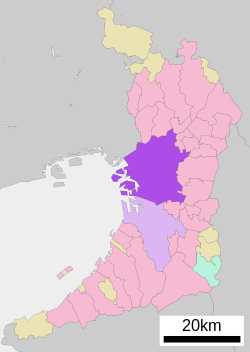

Location of Osaka in Osaka Prefecture | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kansai |

| Prefecture | Osaka |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Toru Hashimoto in office since December 19, 2011 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 223.00 km2 (86.10 sq mi) |

| Population (January 1, 2012) | |

| • Total | 2,871,680 |

| • Density | 13,000/km2 (33,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| - Tree | Sakura |

| - Flower | Pansy |

| Phone number | 06-6208-8181 |

| Address | 1-3-20 Nakanoshima, Kita-ku, Ōsaka-shi, Ōsaka-fu 530-8201 |

| Website | www |

Osaka (大阪, Ōsaka) is a city in the Kansai region of Japan's main island of Honshu, a designated city under the Local Autonomy Law, the capital city of Osaka Prefecture and also the biggest part of Keihanshin area, which is represented by three major cities of Japan, Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe. Located at the mouth of the Yodo River on Osaka Bay, Osaka is the third largest city by population after Tokyo (special wards) and Yokohama.

Keihanshin is the second largest area in Japan by population and one of the largest metropolitan areas highly ranked in the world, with nearly 18 million people,[1] and by GDP the second largest area in Japan and the seventh largest area in the world.

Historically the commercial centre of Japan, Osaka functions as one of the command centers for the Japanese economy. The ratio between daytime and night time population is 141%, the highest in Japan, highlighting its status as an economic center.[2] Its nighttime population is 2.6 million, the third in the country, but in daytime the population surges to 3.7 million, second only after Tokyo (combining the Special wards of Tokyo, which is not a single incorporated city, for statistical purposes. See the Tokyo article for more information on the definition and makeup of Tokyo.) Osaka used to be referred to as the "nation's kitchen" (天下の台所, tenka no daidokoro) in feudal Edo period because it was the centre of trading for rice, creating the first modern futures exchange market in the world.[3][4][5][6]

History

Prehistory to the Kofun period

Some of the earliest signs of habitation in the area of Osaka were found at the Morinomiya remains (森の宮遺跡, Morinomiya iseki), with its shell mounds, including sea oysters and buried human skeletons from the 5th–6th centuries BC. It is believed that what is today the Uehonmachi area consisted of a peninsular land, with an inland sea in the east. During the Yayoi period, permanent habitation on the plains grew as rice farming became popular.[3]

By the Kofun period, Osaka developed into a hub port connecting the region to the western part of Japan. The large numbers, and the increasing size, of tomb mounds found in the plains of Osaka are seen as evidence of political-power concentration, leading to the formation of a state.[3][7]

Asuka and Nara period

In 645, Emperor Kōtoku built his palace, the Naniwa Nagara-Toyosaki Palace in Osaka,[8] making this area the capital (Naniwa-kyō). The place that became the modern city was by this time called Naniwa. This name, and derived forms, are still in use for districts in central Osaka such as Naniwa (浪速) and Namba (難波).[9] Although the capital was moved to Asuka (in Nara Prefecture today) in 655, Naniwa remained a vital connection, by land and sea, between Yamato (modern day Nara Prefecture), Korea, and China.[3][10]

In 744, Naniwa once again became the capital by order of Emperor Shōmu. Naniwa ceased to be the capital in 745, when the Imperial Court moved back to Heijō-kyō (now Nara). The seaport function was gradually taken over by neighboring lands by the end of Nara period, but it remained a lively center of river, channel, and land transportation between Heian-kyō (Kyoto today) and other destinations.

Heian to Edo period

In 1496, the Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist sect set up their headquarters in the heavily fortified Ishiyama Hongan-ji on the site of the old Naniwa imperial palace. Oda Nobunaga started a siege of the temple in 1570. After a decade, the monks finally surrendered, and the temple was razed, and Toyotomi Hideyoshi constructed Osaka Castle in its place.

Osaka was, for a long time, Japan's most important[11] economic center, with a large percentage of the population belonging to the merchant class (see Four divisions of society). Over the course of the Edo period (1603–1867), Osaka grew into one of Japan's major cities and returned to its ancient role as a lively and important port. Its popular culture[12] was closely related to ukiyo-e depictions of life in Edo.

By 1780 Osaka was sponsoring a vibrant cultural life, as typified by its famous Kabuki theaters and Banraku puppet theaters.[13]

In 1837, Ōshio Heihachirō, a low-ranking samurai, led a peasant insurrection in response to the city's unwillingness to support the many poor and suffering families in the area. Approximately one-quarter of the city was razed before shogunal officials put down the rebellion, after which Ōshio killed himself.[14]

Osaka was opened to foreign trade by the government of the Bakufu at the same time as Hyōgo (modern Kobe) on 1 January 1868, just before the advent of the Boshin War and the Meiji Restoration.[15]

Osaka residents were stereotyped in Edo literature from at least the 18th century. Jippenisha Ikku in 1802 depicted Osakans as stingy almost beyond belief. In 1809 the derogatory term "Kamigata zeeroku" was used by Edo residents to characterize inhabitants of the Osaka region in terms of calculation, shrewdness, lack of civic spirit, and the vulgarity of Osaka dialect. Edo writers aspired to samurai culture, and saw themselves as poor but generous, chaste, and public spirited. Edo writers by contrast saw "zeeroku" as obsequious apprentices, stingy, greedy, gluttonous, and lewd. To some degree Osaka residents are stigmatized by Tokyo observers in much the same way down to the present, especially in terms of gluttony. As a famous saying has it, "Osaka wa kuidaore" (Osaka people eat 'til they drop).[16]

Modern Osaka

The modern municipality was established[17] in 1889 by government ordinance, with an initial area of 15 km², overlapping today's Chūō and Nishi wards. Later, the city went through three major expansions to reach its current size of 222 km².

Osaka was the industrial center most clearly defined in the development of capitalism in Japan. The rapid industrialization attracted many Korean immigrants, who set up a life apart for themselves.[18] The political system was pluralistic, with a strong emphasis on promoting industrialization and modernization.[19] Literacy was high and the educational system expanded rapidly, producing a middle class with a taste for literature and a willingness to support the arts.[20]

Like its European and American counterparts, Osaka displayed slums, unemployment, and poverty. In Japan it was here that municipal government first introduced a comprehensive system of poor relief, copied in part from British models. Osaka policymakers stressed the importance of family formation and mutual assistance as the best way to combat poverty. This minimized the cost of welfare programs.[21]

The devastation during World War II was enormous, as fleets of American B-29 bombers blasted away on a regular basis in the last year of the war. Many people fled and most of the industrial districts were severely damaged. However the city quickly rebuilt its infrastructure after 1945 and regained its status as a major industrial and cultural center.[22]

Derivation of name

"Osaka" literally means "large hill" or "large slope." It is unclear when this name gained prominence over Naniwa, but the oldest usage of the name dates back to a 1496 text. Osaka, now written 大阪, was formerly written using a different second kanji as 大坂 prior to 1870. At the time, the partisans for the Meiji Restoration wished to avoid the second kanji being implicitly read as "士反," meaning samurai rebellion. The old writing is still in very limited use to emphasize history, but the second kanji 阪 is now universally considered referring to Osaka city and prefecture only, to distinguish it from homonyms in other Japanese prefectures.

Geography and climate

Geography

The city of Osaka has its west side open to Osaka Bay. It is otherwise completely surrounded by more than ten smaller cities, all of them in Osaka Prefecture, with one exception: the city of Amagasaki, belonging to Hyōgo Prefecture, in the northwest. The city occupies a larger area (about 13%) than any other city or village within Osaka Prefecture. When the city was established in 1889, the city occupied roughly what today are the wards of Chuo and Nishi, with only 15.27 square kilometres (3,773 acres) size, and grew into today's 222.30 square kilometres (54,932 acres) over several expansions. The biggest leap was in 1925, when 126.01 square kilometres (31,138 acres) was claimed through an expansion. The highest point in Osaka is in Tsurumi-ku at 37.5 metres (123.0 ft) Tokyo Peil, and the lowest point is in Nishiyodogawa-ku at −2.2 metres (−7.2 ft) Tokyo Peil.[23]

Climate

Osaka belongs to the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa), with four distinct seasons. Its winters are generally mild, with January being the coldest month having an average high of 9.3 °C (49 °F). The city rarely sees snowfall during the winter. Spring in Osaka starts off mild, but ends up being hot and humid. It also tends to be Osaka’s wettest season, with the Tsuyu or rainy season occurring between late May to early July. Summers are very hot and humid. In the months of July and August, the average daily high temperature approaches 35 °C (95 °F), while average nighttime temperatures typically hover around 25 °C (77 °F). Fall in Osaka sees a cooling trend, with the early part of the season resembling summer while the latter part of fall resembling winter.

| Climate data for Osaka (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.7 (1.72) |

58.7 (2.31) |

99.5 (3.92) |

121.1 (4.77) |

139.6 (5.50) |

201.0 (7.91) |

155.4 (6.12) |

99.4 (3.91) |

174.9 (6.89) |

109.3 (4.30) |

66.3 (2.61) |

37.7 (1.48) |

1,306.1 (51.42) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 62 | 69 | 70 | 67 | 68 | 66 | 64 | 62 | 64 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 141.9 | 130.9 | 158.2 | 183.6 | 199.5 | 149.5 | 186.2 | 210.6 | 149.4 | 161.5 | 146.6 | 149.2 | 1,967.1 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Association[24] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

Central Osaka is often divided into two areas referred to as Kita (北, lit. north) and Minami (南, lit. south), at either end of the major thoroughfare Midōsuji.[25] Kita is roughly the area surrounding the business and retail district of Umeda. Minami is home to the Namba, Shinsaibashi, and Dōtonbori shopping districts. The entertainment district around Dōtonbori Bridge with its famous giant mechanical crab, Triangle Park, and Amerikamura ("America Village") is in Minami. In Yodoyabashi and Honmachi, between Kita and Minami, is the traditional business area where courts and national/regional headquarters of major banks are located. The newer business area is in the Osaka Business Park located nearby Osaka Castle. Business districts have also formed around the secondary rail termini, such as Tennoji Station and Kyobashi Station.

“The 808 bridges of Naniwa” was an expression in old Japan for awe and wonder, an adage known across the land. “808” was a large number which symbolized the idea of “uncountable”. In the Edo period there were only about 200 bridges. Since Osaka is crossed by a number of rivers and canals, many bridges were built with specific names, and the areas surrounding the bridges were often referred to by the names of the bridges, too. Some of the waterways, such as the Nagahori canal, have been filled in, while others still remain.[26] In 1925, there were actually 1629 bridges in Osaka but with the filling in of canals and rivers, as of April 2003, the number has dropped to 872, 760 of which are currently managed by Osaka City.[27]

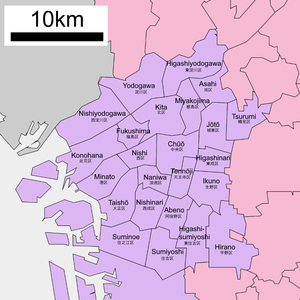

Wards

Osaka has 24 wards (ku):

Demographics

According to the census in 2005, there were 2,628,811 residents in Osaka, an increase of 30,037 or 1.2% from 2000.[28] There were 1,280,325 households with approximately 2.1 persons per household. The population density was 11,836 persons per km². The Great Kanto Earthquake caused a mass migration to Osaka between 1920 and 1930, and the city became Japan's largest city in 1930 with 2,453,573 people, outnumbering even Tokyo, which had a population of 2,070,913. The population peaked at 3,252,340 in 1940, and had a post-war peak of 3,156,222 in 1965, but continued to decrease since, as the residents moved out to the suburbs.[29]

There were 99,775.5 registered foreigners, the two largest groups being Korean (71,015) and Chinese (11,848). Ikuno, with its Tsuruhashi district, is the home to one of the largest population of Korean residents in Japan, with 27,466 registered zainichi Koreans.[30][31]

Dialect

The commonly spoken dialect of this area is Osaka-ben. Of the many other particularities that characterize Osaka-ben, an example is the use of the suffix hen instead of nai in the negative of verbs.

Politics

| Local administration | |

|---|---|

| The Mayor and the Council | |

Osaka City Hall | |

| Mayor: | Toru Hashimoto |

| Vice Mayors: | Akira Morishita, Takashi Kashiwagi |

| City Council | |

| President: | Toshifumi Tagaya (LDP) |

| Members: | 89 councilors (1 vacant) |

| Factions: | Liberal Democratic Party and Citizen's Club (33), Komei Party (20), Democratic Party of Japan and Citizens' Coalition (19), Japanese Communist Party (16) |

| Seats by districts: | Ward (no. of seats)

|

| Website | Osaka City Council |

| Note: As of March 10th, 2009 | |

The Osaka City Council is the city's local government formed under the Local Autonomy Law. The Council has eighty-nine seats, allocated to the twenty-four wards proportional to their population and re-elected by the citizens every four years. The Council elects its President and Vice President. Toshifumi Tagaya (LDP) is the current and 104th President since May 2008. The Mayor of the city is directly elected by the citizens every four years as well, in accordance with the Local Autonomy Law. Toru Hashimoto, former governor of Osaka Prefecture is the 19th mayor of Osaka since 2011. The mayor is supported by two Vice Mayors, currently Akira Morishita and Takashi Kashiwagi, who are appointed by him in accordance with the city bylaw.[32]

Osaka also houses several agencies of the Japanese Government. Below is a list of Governmental Offices housed in Osaka.

|

|

Politics regarding the use of nuclear energy

On 27 February 2012 three Kansai cities, Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe, jointly asked Kansai Electric Power Company to break its dependence on nuclear power. In a letter to KEPCO they also requested to disclose information on the demand and supply of electricity, and for lower and stable prices. The three cities were stockholders of the plant: Osaka owned 9% of the shares, while Kobe had 3% and Kyoto 0.45%. Toru Hashimoto, the mayor of Osaka, announced a proposal to minimize the dependence on nuclear power for the shareholders meeting in June 2012.[33]

On 18 March 2012 the city of Osaka decided as largest shareholder of Kansai Electric Power Co, that at the next shareholders-meeting in June 2012 it would demand a series of changes:

- that Kansai Electric would be split into two companies, separating power generation from power transmission

- a reduction of the number of the utility's executives and employees.

- the implementation of absolutely secure measurements to ensuring the safety of the nuclear facilities.

- the disposing of spent fuel.

- the installation of new kind of thermal power generation to secure non-nuclear supply of energy.

- selling all unnecessary assets including the stock holdings of KEPCO.

In this action Osaka had secured the support of two other cities and shareholders: Kyoto and Kobe, but with their combined voting-rights of 12.5 percent they were not certain of the ultimate outcome, because for this two-thirds of the shareholders would be needed to agree to revise the corporate charter.[34]

At a meeting held on 10 April 2012 by the "energy strategy council", formed by the city of Osaka and the governments of the prefectures, it became clear that at the end of the fiscal year 2011 some 69 employees of Kansai Electric Power Company were former public servants. "Amakudari" was the Japanese name for this practice: rewarding by hiring officials that formerly controlled and supervised the firm: among these people were:

- 13 ex-officials of the: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

- 3 ex-officials of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry,

- 2 ex-officials of the Ministry of the Environment,

- 16 former policemen,

- 13 former civil engineers.

- 16 former policemen,

- 10 ex-firefighters

Besides this, it became known that Kansai Electric had done about 600 external financial donations, to a total sum of about 1.695 billion yen:

- 70 donations were paid to local governments: to a total of 699 million yen

- 100 donations to public-service organizations: 443 million yen,

- 430 donations to various organizations and foundations: a total of 553 million yen

During this meeting some 8 conditions were compiled, that needed to be fulfilled before a restart of the No.3 and No.4 reactors Oi Nuclear Power Plant:

- the consent of the local people and government within 100 kilometer from the plant

- the installation of a new independent regulatory agency

- a nuclear safety agreement

- the establishment of new nuclear safety standards

- stress tests and evaluations based on these new safety rules [35]

Economy

See also Companies based in Osaka

The gross city product of Osaka in fiscal year 2004 was ¥21.3 trillion, an increase of 1.2% over the previous year. The figure accounts for about 55% of the total output in the Osaka Prefecture and 26.5% in the Kinki region. In 2004, commerce, services, and manufacturing have been the three major industries, accounting for 30%, 26%, and 11% of the total, respectively. The per capita income in the city was about ¥3.3 million, 10% higher than that of the Osaka Prefecture.[36] MasterCard Worldwide reported that Osaka ranks 19th among the world's leading cities and plays an important role in the global economy.[37]

The GDP in the greater Osaka area (Osaka and Kobe) is $341 billion. Osaka, along with Paris and London, has one of the most productive hinterlands in the world.[38]

Historically, Osaka was the center of commerce in Japan, especially in the middle and pre-modern ages. Nomura Securities, the first brokerage firm in Japan, was founded in the city in 1925, and Osaka still houses a leading futures exchange. Many major companies have since moved their main offices to Tokyo. However, several major companies, such as Panasonic, Sharp, and Sanyo, are still headquartered in Osaka. Recently, the city began a program, headed by mayor Junichi Seki, to attract domestic and foreign investment.[39]

The Osaka Securities Exchange, specializing in derivatives such as Nikkei 225 futures, is based in Osaka. The merger with JASDAQ will help the Osaka Securities Exchange become the largest exchange in Japan for start-up companies.[40]

According to a U.S. study, Osaka is the second most expensive city for expatriate employees in the world and in Japan behind Tokyo. It jumped up nine places from 11th place in 2008. Osaka was the 8th most expensive city in 2007.[41]

Transportation

Air

Osaka is served by two airports outside the city.

Kansai International Airport (IATA: KIX) handles all scheduled international passenger flights, some domestic flights, and most cargo flights. It is on an artificial island that sits off-shore in Osaka Bay and is administratively part of the nearby town of Tajiri. The airport is linked by a bus and train service into the center of the city and major suburbs.

Osaka International Airport (IATA:ITM), on the border of the cities of Itami and Toyonaka, houses most of the domestic services, some international cargo flights, and international VIP charters from and to the metropolitan region.

Sea

The port of Osaka serves as a shipping hub for the Kansai region along with the port of Kobe.

Ferry

Osaka's international ferry connections are far greater than Tokyo's, mostly due to geography. There are international ferries that leave Osaka for Shanghai, Tianjin, Korea, and until recently Taiwan. Osaka's domestic ferry services include regular service to ports such as Kitakyushu, Kagoshima, Miyazaki and Okinawa.

Shipping

Shipping plays the crucial role for the freight coming in and out of the area nationally and internationally, and Greater Osaka areas exports and imported raw materials span the globe, with no one port dominating. Though the port of Kobe was in the 1970s the busiest in the world by containers handled, it no longer ranks among the top twenty worldwide. Kansai area is home to 5 existing LNG terminals.

- Port of Osaka

- Port of Kobe

- Port of Sakai-Senboku (In Osaka Prefecture)

- Port of Himeji

Sister ports

The Port of Osaka has the following sister ports.[42]

San Francisco, United States (since 1967)

San Francisco, United States (since 1967) Melbourne, Australia (since 1974)

Melbourne, Australia (since 1974) Le Havre, France (since 1980)

Le Havre, France (since 1980) Shanghai, China (since 1981)

Shanghai, China (since 1981) Valparaíso, Chile (since 1983)

Valparaíso, Chile (since 1983) Kanpur, India (since 1996)

Kanpur, India (since 1996) Busan, South Korea (since 1985)

Busan, South Korea (since 1985) Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (since 1994)

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (since 1994)

Rail

Greater Osaka has an extensive network of railway lines, comparable to that of Greater Tokyo. Main rail terminals in the city include, Umeda, Namba, Tennoji, Kyobashi, and Yodoyabashi.

High speed rail

JR Central and JR West operate high-speed trains on the Tōkaidō-Sanyō Shinkansen line. Shin-Ōsaka Station is the Shinkansen terminal in Osaka. This station is connected to Ōsaka Station at Umeda by the JR Kyoto Line and the subway Midōsuji Line. All Shinkansen trains including Nozomi stop at Shin-Ōsaka Station and provide access to other major cities in Japan, such as Kyoto, Nagoya, Yokohama, and Tokyo to the east, and Kobe, Okayama, Hiroshima, Kitakyushu and Fukuoka to the west. On March 12, 2011, JR West and JR Kyushu introduced new Shinkansen services, Mizuho and Sakura, linking Osaka with Kumamoto, Kagoshima, and other cities in central and south Kyushu.[43]

Commuter rail

Both JR West and private lines connect Osaka and its suburbs. The commuter rail network of JR West is called the Urban Network. Major stations on the JR Osaka Loop Line include Osaka (Umeda), Tennōji, Tsuruhashi, and Kyōbashi. JR West competes with such private rail operators as Keihan Electric Railway, Hankyu Railway, Hanshin Railway, Kintetsu Corporation, and Nankai Electric Railway. The Keihan and Hankyu lines connect to Kyoto; the Hanshin and Hankyu lines connect to Kobe; the Kintetsu lines connect to Nara, Yoshino, Ise and Nagoya; and the Nankai lines connect to Osaka's southern suburbs and Kansai International Airport as well as Wakayama and Mt. Koya. Many lines in Greater Osaka accept either ICOCA or PiTaPa contactless smart cards for payment.[44]

Municipal subway

The Osaka Municipal Subway system is a part of Osaka's extensive rapid transit system. The metro system alone ranks 8th in the world by annual passenger ridership, serving over 912 million people annually (a quarter of Greater Osaka Rail System's 4 billion annual riders), despite being only 8 of more than 70 lines in the metro area.

Bus

Regular bus services are provided by Osaka Municipal Transportation Bureau (the City Bus), as well as by group companies of Hankyu, Hanshin and Kintetsu. The City runs a dense network covering much parts of the city.[45] The fare for the regular buses is a flat rate of 200 yen, or 100 yen for the smaller "Red Bus" looplines operated within segmented areas of the city. The other bus companies provide their services in supplement to their railway networks.

Culture and lifestyle

Shopping and culinary

Osaka has a large number of wholesalers and retail shops: 25,228 and 34,707 respectively in 2004, according to the city statistics.[46] A lot of them are concentrated in the wards of Chuō (10,468 shops) and Kita (6,335 shops). Types of shops varies from malls to conventional shōtengai shopping arcades, built both above- and underground.[47] Shōtengai are seen across Japan, and Osaka has the longest one in the country.[48] The Tenjinbashi-suji arcade stretches from the road approaching the Temmangu shrine and continues for 2.6 km going north to south. The type of stores along the arcade includes commodities, clothing, and catering outlets.

Other shopping areas are Den Den Town, the electronic and manga/anime district, which is comparable to Akihabara; and the Umeda district, which has the Hankyu Sanbangai shopping mall and Yodobashi Camera, a huge electrical appliance store that offers a vast range of fashion stores, restaurants, and a Shonen Jump store.

Osaka is known for its food, both in Japan and abroad. Author Michael Booth and food critic François Simon of Le Figaro have both suggested that Osaka is the food capital of the world.[49] Osakans love for the culinary is also made apparent in the old saying "Kyotoites are financially ruined by overspending on clothing, Osakans are ruined by spending on food".[50] Regional cuisine includes okonomiyaki (pan-fried batter cake), takoyaki (octopus dumplings), udon (a noodle dish), as well as the traditional oshizushi (pressed sushi), particularly battera (バッテラ, pressed mackerel sushi).

Other shopping districts include:

- American Village (Amerika-mura or "Ame-mura") – fashion for young people

- Dōtonbori – part of Namba district and considered heart of the city

- Namba – main shopping, sightseeing, and restaurant area

- Shinsaibashi – luxury goods and department stores

- Umeda – theaters, boutiques, and department stores near the train station

Entertainment and performing arts

- Osaka is home to the National Bunraku Theatre,[51] where traditional puppet plays, bunraku, are performed.

- At Osaka Shouchiku-za, close to Namba station, kabuki can be enjoyed as well as manzai. Nearby is the Shin-kabuki-za, where enka concerts and Japanese dramas are performed.

- Yoshimoto, a Japanese entertainment conglomarate operates two halls in the city for manzai and other comedy shows: the Namba Grand Kagetsu and the Kyōbashi Kagetsu halls.

- The Hanjō-tei opened in 2006, dedicated to rakugo. The theatre is in the Temmangū area.

- Umeda Arts Theater opened in 2005 after relocating from its former 46-year-old Umeda Koma Theater. The theater has a main hall with 1,905 seats and a smaller theater-drama hall with 898 seats. Umeda Arts Theatre stages various type of performances including musicals, music concerts, dramas, rakugo, and others.

- The Symphony Hall, built in 1982, is the first hall in Japan designed specially for classical music concerts. The Hall was opened with a concert by the Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, which is based in the city. Orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic and Vienna Philharmonic have played here during their world tours as well.

- Osaka-jō Hall is a multi-purpose arena in Osaka-jō park with a capacity for up to 16,000 people. The hall has hosted numerous events and concerts including both Japanese and international artists.

- Near City Hall in Nakanoshima, is Osaka Central Public Hall, a Neo-Renaissance-style building first opened in 1918. Re-opened in 2002 after major restoration, it serves as a multi-purpose rental facility for citizen events.

- The Osaka Shiki Theatre[52] is one of the nine private halls operated nationwide by the Shiki Theatre, staging straight plays and musicals.

- Festival Hall was a hall hosting various performances including noh, kyogen, kabuki, ballets as well as classic concerts. The Bolshoi Ballet and the Philharmonia are among the many that were welcomed on stage in the past. The hall has closed at the end of 2008, planned to re-open in 2013 in a new facility.

Annual festivals

One of the most famous festivals held in Osaka, the Tenjin-matsuri is held on July 24 and 25. Other festivals in Osaka include the Aizen-matsuri, Shōryō-e and Tōka-Ebisu. Furthermore, Osaka annually hosts the Kansai International Film Festival...:)

Museum and galleries

See also: Museums in Osaka

The National Museum of Art (NMAO) is a subterranean Japanese and international art museum, housing mainly collections from the post-war era and regularly welcoming temporary exhibitions. Osaka Science Museum is in a five storied building next to the National Museum of Art, with a planetarium and an OMNIMAX theatre. The Museum of Oriental Ceramics holds more than 2,000 pieces of ceramics, from China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, featuring displays of some of their Korean celadon under natural light. Osaka Municipal Museum of Art is inside Tennōji park, housing over 8,000 pieces of Japanese and Chinese paintings and sculptures. The Osaka Maritime Museum, opened in 2000, is accessible only through an underwater tunnel into its dome. The Osaka Museum of History, opened in 2001, is located in a 13-story modern building providing a view of Osaka Castle. Its exhibits cover the history of Osaka from pre-history to the present day. Osaka Museum of Natural History houses a collection related to natural history and life.

Sports

Osaka hosts four professional sport teams: one of them is the Orix Buffaloes, a Nippon Professional Baseball team, playing its home games at Kyocera Dome Osaka. Another baseball team, the Hanshin Tigers, although based in Nishinomiya, Hyōgo, plays a part of its home games in Kyocera Dome Osaka as well, when their homeground Kōshien Stadium is occupied with the annual National High School Baseball Championship games during summer season. There are two J.League clubs, Gamba Osaka, plays its home games at Osaka Expo '70 Stadium. Another club Cerezo Osaka, plays its home games at Nagai Stadium. The city is home to Osaka Evessa, a basketball team that plays in the bj league. Evessa has won the first three championships of the league since its establishment. Kintetsu Liners, a rugby union team, play in the Top League. After winning promotion in 2008-09, they will again remain in the competition for the 2009-10 season. Their base is the Hanazono Rugby Stadium.

The Sangatsubasho (三月場所 sangatsu basho, literally March ring), one of the six regular tournaments of professional Sumo is held annually in Osaka at Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium.

Another major annual sporting event that takes place is Osaka is Osaka International Ladies Marathon. Held usually at the end of January every year, the 42.195 km race starts from Nagai Stadium, runs through Nakanoshima, Midōsuji and Osaka castle park, and returns to the stadium. Another yearly event held at Nagai Stadium is the Osaka Gran Prix Athletics games operated by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) in May. The Osaka GP is the only IAAF games annually held in Japan.

Osaka is the home of the 2011 created Japan Bandy Federation [8] and the introduction of bandy was made in the city.[9]

Media

Osaka serves as one of the media hubs for Japan, housing headquarters of many media-related companies. Abundant television production takes place in the city and every nationwide TV network (with the exception of TXN network) registers its secondary-key station in Osaka. All five nationwide newspaper majors also house their regional headquarters, and most local newspapers nationwide have branches in Osaka. However major film productions are uncommon in the city. Most major films are produced in nearby Kyoto or in Tokyo. The Ad Council Japan is based in Osaka.

Newspapers

All the five nationwide newspaper majors of Japan, the Asahi Shimbun, the Mainichi Shimbun, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, the Sankei Shimbun and the Yomiuri Shimbun,[53] have their regional headquarters in Osaka and issue their regional editions. Furthermore, Osaka houses Osaka Nichi-nichi Shimbun, its newspaper press. Other newspaper related companies located in Osaka include include, the regional headquarters of FujiSankei Business i.;Houchi Shimbunsha; Nikkan Sports;Sports Nippon, and offices of Kyodo News Jiji Press; Reuters; Bloomberg L.P..

Television and radio

The five TV networks are represented by Asahi Broadcasting Corporation (ANN), Kansai Telecasting Corporation (FNN), Mainichi Broadcasting System, Inc. (JNN), Television Osaka, Inc. (TXN) and Yomiuri Telecasting Corporation (NNN), headquartered in Osaka. NHK has also its regional station based in the city. AM Radio services are provided by NHK as well as the ABC Radio (Asahi Broadcasting Corporation), MBS Radio (Mainichi Broadcasting System, Inc.) and Radio Osaka (Osaka Broadcasting Corporation) and headquartered in the city. FM services are available from NHK, FM Osaka, FM802 and FM Cocolo, the last providing programs in multiple languages including English.

As of February 2009, the city is fully covered by terrestrial digital TV broadcasts[54]

Publishing companies

Osaka is home to many publishing companies including: Examina, Izumi Shoin, Kaihou Shuppansha, Keihanshin Elmagazine, Seibundo Shuppan, Sougensha, and Toho Shuppan.

Places of interest

Tourist attractions include:

21st-century Osaka

Amusement parks

- Osaka Aquarium Kaiyukan – an aquarium located in Osaka Bay, containing 35,000 aquatic animals in 14 tanks, the largest of which holds 5,400 tons of water and houses a variety of sea animals including whale sharks. This tank is the world's second-largest aquarium tank, behind the Georgia Aquarium, whose largest tank holds approximately 29,000 tons of water.

- Tempozan Ferris Wheel, located next to the aquarium

- Tennōji Zoo

- Universal Studios Japan

- Umeda Joypolis Sega

- Shin-Umeda city – an innovative structure that has the floating garden observatory 170 m from the ground, which offers a 360-degree panoramic view of Osaka, popular for photographs, a structure that also houses an underground mall with restaurants and is styled in the early Showa period in the 1920s.

Parks

- Nakanoshima Park: About 10.6 ha. In the vicinity of the City Hall

- Osaka Castle Park: About 106 ha. Includes Osaka-jō Hall, a Japanese apricot garden, and more

- Sumiyoshi Park

- Tennōji Park: About 28 ha. Includes Tennōji Zoo; an art museum (established by contribution from Sumitomo family in 1936); and a Japanese garden, Keitaku-en (慶沢園). Keitaku-en was constructed in 1908 by Jihei Ogawa (小川治兵衛), an illustrious gardener in Japan. This was originally one of Sumitomo family's gardens until 1921.

- Utsubo Park

- Nagai Park The 2007 IAAF World Championships in Athletics were held at Nagai Stadium, located in this park.

- Tsurumi-Ryokuchi Park with the Sakuya Konohana Kan was the site of the flower expo in 1990.

Temples, shrines, and other historical sites

- Osaka Castle

- Sanko Shrine

- Shitennō-ji – The oldest buddhist temple in Japan, established in 593 AD by Prince Shōtoku

- Sumiyoshi Taisha One of the oldest Shinto shrines, built in 211 AD.[55]

- Tamatsukuri Inari Shrine

- Ōsaka Tenmangū Shrine

Entertainment

- Doyama-cho - a homosexual District

- Shinsekai district and Tsutenkaku Tower

- Tobita red-light district

Education

Public elementary and junior high schools in Osaka are operated by the city of Osaka. Its supervisory organization on educational matters is Osaka City Board of Education.[56] Likewise, public high schools are operated by the Osaka Prefectural Board of Education.

Osaka city once had a large number of universities and high schools, but because of growing campuses and the need for larger area, many chose to move to the suburbs, including Osaka University.[57]

- Kansai University

- Osaka City University

- Osaka University of Economics

- Osaka Institute of Technology

- Osaka Jogakuin College

- Osaka Seikei University

- Soai University

- Osaka University of Arts, Minamikawachi District, Osaka

- Osaka University of Education

- Kinki University

Libraries

Learned society

- The Japanese Academy of Family Medicine

Natives

International relations

Sister cities

Osaka is twinned with the following cities around the world.[59]

San Francisco, United States (since 1957)

San Francisco, United States (since 1957) São Paulo, Brazil (since 1969)[60][61]

São Paulo, Brazil (since 1969)[60][61] Chicago, United States (since 1973)

Chicago, United States (since 1973) Shanghai, China (since 1974)

Shanghai, China (since 1974) Melbourne, Australia (since 1974)

Melbourne, Australia (since 1974) Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 1979)[62]

Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 1979)[62] Milan, Italy (since 1981)[63]

Milan, Italy (since 1981)[63] Hamburg, Germany (since 1989)

Hamburg, Germany (since 1989) Kanpur, India (since 1998)[citation needed]

Kanpur, India (since 1998)[citation needed]

Osaka also has the following friendship and cooperation cities.[64]

Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 1998)

Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 1998) Budapest, Hungary (since 1998)[65]

Budapest, Hungary (since 1998)[65] Busan, South Korea (since 2008)[66]

Busan, South Korea (since 2008)[66]

Business partner cities

Osaka's business partnerships are:[67]

See also

- List of metropolitan areas by population

- List of metropolitan areas in Japan by population

- Osaka Metropolis plan

References

- ^ "Table 92, Final Report of The 2000 Population Census". E-stat.go.jp. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Population Census: I Daytime Population". Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 2002-03-29. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ a b c d "Historical Overview, the City of Osaka official homepage". Retrieved 2009-03-21. [dead link] Navigate to the equivalent Japanese page (大阪市の歴史 タイムトリップ20,000年 (History of Osaka, A timetrip back 20,000 years))[1] for additional information.

- ^ Aprodicio A. Laquian (2005). Beyond metropolis: the planning and governance of Asia's mega-urban regions. Washington, D.C: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-8018-8176-5.

- ^ edited by James L. McClain and Wakita Osamu (1999). Osaka, the merchants' capital of early modern Japan. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8014-3630-3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Robert C. Hsu (1999). The MIT encyclopedia of the Japanese economy. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-262-08280-2.

- ^ Wada, Stephanie (2003). Tsuneko S. Sadao, Stephanie Wada, Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview. ISBN 978-4-7700-2939-3. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ "史跡 難波宮跡, 財団法人 大阪都市協会 (Naniwa Palace Site, by Osaka Toshi Kyokai)" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ The name was also historically written 浪華 or 浪花, with the same pronunciation. These are uncommon today but still used sometimes.

- ^ edited by Peter G. Stone and Philippe G. Planel (1999). The constructed past: experimental archaeology, education, and the public. London: Routledge in association with English Heritage. p. 68. ISBN 0-415-11768-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Osaka city[dead link]

- ^ A Guide to the Ukiyo-eTokyo national museum[dead link][2]

- ^ C. Andrew Gerstle, Kabuki Heroes on the Osaka Stage 1780-1830 (2005)

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 400. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jansen, Marius B; Hall, John Whitney (1989). ''The Cambridge History of Japan'' p.304. Books.google.com. ISBN 978-0-521-22356-0. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Richard Torrance, "Literacy and Literature in Osaka, 1890-1940," The Journal of Japanese Studies 31#1 (Winter 2005), pp. 27-60

- ^ "Osaka city". Osaka-info.jp. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Chisato Hotta, "The Construction of the Korean Community in Osaka between 1920 and 1945: A Cross-Cultural Perspective." PhD dissertation U. of Chicago 2005. 498 pp. DAI 2005 65(12): 4680-A. DA3158708 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- ^ Blair A. Ruble, Second Metropolis: Pragmatic Pluralism in Gilded Age Chicago, Silver Age Moscow, and Meiji Osaka. (2001)

- ^ Richard Torrance, "Literacy and Literature in Osaka, 1890-1940," Journal of Japanese Studies 31#1 (Winter 2005), p.27-60 in Project Muse

- ^ Kingo Tamai, "Images of the Poor in an Official Survey of Osaka, 1923-1926." Continuity and Change 2000 15(1): 99-116. Issn: 0268-4160 Fulltext: Cambridge UP

- ^ Carola Hein, Jeffry M. Diefendorf, and Ishida Yorifusa, eds, Rebuilding Urban Japan after 1945. (2003).

- ^ http://www.city.osaka.jp/keikakuchousei/toukei/G000/Gyh19/Gb00/Gb00.html

- ^ Monthly Values. Template:Ja icon Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Dodd, Jan (2001). The Rough Guide to Japan. Rough Guides. p. 439. ISBN 1-85828-699-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ More About Osaka, Osaka City Government

- ^ Eiichi Watanabe, Dan M. Frangopol, Tomoaki Utsunomiya (2004). Bridge Maintenance, Safety, Management and Cost: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Bridge Maintenance, Safety and Management. Kyoto, Japan: Taylor & Francis. p. 195. ISBN 978-90-5809-680-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "2005 Population Census". Statistics Bureau, Director-General for Policy Planning (Statistical Standards) and Statistical Research and Training Institute, Japan. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ Prasad Karan, Pradyumna (1997). The Japanese City. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-8131-2035-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ JOHNSTON, ERIC (Saturday, June 29, 2002). "Tsuruhashi, home of 'exotic' Korea in Osaka". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Karan, Pradyumna Prasad. The Japanese City. University Press of Kentucky. p. 124. ISBN 0-8131-2035-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Osaka City Council homepage". City.osaka.lg.jp. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ The Mainichi Shimbun (27 February 2012)3 major Kansai cities aim to break dependence on nuclear power

- ^ The Mainichi Shimbun (19 March 2012)Osaka aims to end Kansai Electric's nuclear power ops as shareholder

- ^ The Mainichi Shimbun (10 April 2012) Kansai Electric, affiliates had 69 ex-bureaucrats employed as execs as of end of fiscal 2011

- ^ "大阪市データネット 市民経済計算 (Osaka City Datanet: Osaka City Economy)" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ http://www.mastercard.com/us/company/en/insights/pdfs/2008/MCWW_WCoC-Report_2008.pdf

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ 経営に資する統合的内部監査. "大証との経営統合、ようやく決着 ジャスダック : J-CASTニュース". J-cast.com. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Worldwide Cost of Living survey 2009". Mercer.com. 2009-07-07. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Osaka's Sister Ports, Port & Harbor Bureau, City of Osaka". Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ "山陽新幹線・九州新幹線直通列車のご案内". JR West. 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-08-14.[dead link]Template:Ja icon

- ^ JR West. "JRおでかけネット - きっぷ・サービス案内 - ご利用可能エリア 近畿圏エリア" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ^ the City Bus network[dead link]

- ^ http://www.city.osaka.jp/keikakuchousei/toukei/G000/Gyh17/Ga00/Ga00.html

- ^ Reiber, Beth (2008). Frommer's Japan. Frommer's. p. 388. ISBN 0-470-18100-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [5][dead link]

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/wordofmouth/2009/jul/13/osaka-japan-best-food-city

- ^ Shinbunsha, Asahi (1979). Japan Quarterly, Asahi Shinbunsha 1954. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ "National Theatre of Japan". Ntj.jac.go.jp. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "劇団四季 サイトインフォメーション Theatres". Shiki.gr.jp. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ The five largest newspapers by number of circulation in Japan in alphabetical order. Mooney, Sean (2000). 5,110 Days in Tokyo and Everything's Hunky-dory. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 99–104. ISBN 1-56720-361-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ See the Association for Promotion of Digital Broadcasting web page for the coverage map.

- ^ Dodd, Jan (2001). The Rough Guide to Japan. Rough Guides. p. 446. ISBN 1-85828-699-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [6][dead link]

- ^ "History of Education in Osaka 大阪市の教育史 osaka-shi no kyōikushi" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2009-02-18. [dead link]

- ^ [7][dead link]

- ^ "Sister Cities, the official website of the Osaka city". Retrieved 2009-08-05. [dead link]

- ^ Prefeitura.Sp - Descentralized Cooperation[dead link]

- ^ "International Relations - São Paulo City Hall - Official Sister Cities". Prefeitura.sp.gov.br. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Saint Petersburg in figures - International and Interregional Ties". Saint Petersburg City Government. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ "Milano - Città Gemellate". Municipality of Milan. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ "Friendship and Cooperation Cities, the official website of the Osaka city". Retrieved 2009-08-05. [dead link]

- ^ "Sister cities of Budapest" (in Hungarian). Official Website of Budapest. Retrieved 2009-07-01. [dead link]

- ^ "大阪市市政 友好協力都市(釜山広域市)(Busan (Friendship Cooperation City), the official website of Osaka city)". Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ "Business Partner Cities (BPC), the official website of Osaka city". Retrieved 2009-08-05.

Further reading

- Gerstle, C. Andrew. Kabuki Heroes on the Osaka Stage 1780-1830 (2005).

- Hanes, Jeffrey. The City as Subject: Seki Hajime and the Reinvention of Modern Osaka (2002) online edition

- Hauser, William B. "Osaka: a Commercial City in Tokugawa Japan." Urbanism past and Present 1977-1978 (5): 23-36.

- Hein, Carola, et al. Rebuilding Urban Japan after 1945. (2003). 274 pp.

- Hotta, Chisato. "The Construction of the Korean Community in Osaka between 1920 and 1945: A Cross-Cultural Perspective." PhD dissertation U. of Chicago 2005. 498 pp. DAI 2005 65(12): 4680-A. DA3158708 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Lockyer, Angus. "The Logic of Spectacle C. 1970," Art History, Sept 2007, Vol. 30 Issue 4, p571-589, on the international exposition held in 1970

- McClain, James L. and Wakita, Osamu, eds. Osaka: The Merchants' Capital of Early Modern Japan. (1999). 295 pp. online edition

- Michelin Red Guide Kyoto Osaka Kobe 2011 (2011)

- Najita, Tetsuo. Visions of Virtue in Tokugawa Japan: The Kaitokudo Merchant Academy of Osaka. (1987). 334 pp. online edition

- Rimmer, Peter J. "Japan's World Cities: Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya or Tokaido Megalopolis?" Development and Change 1986 17(1): 121-157. Issn: 0012-155x

- Ropke, Ian Martin. Historical Dictionary of Osaka and Kyoto. (1999) 273pp

- Ruble, Blair A. Second Metropolis: Pragmatic Pluralism in Gilded Age Chicago, Silver Age Moscow, and Meiji Osaka. (2001). 464 pp.

- Torrance, Richard. "Literacy and Literature in Osaka, 1890-1940," The Journal of Japanese Studies 31#1 (Winter 2005), pp. 27–60 in Project Muse

External links

- Official Osaka Prefectural Government homepage

- Official City of Osaka homepage

- Official Osaka Tourist Guide

- Osaka Guide with interactive map