Quran: Difference between revisions

Atethnekos (talk | contribs) cns |

|||

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Quran in the original Arabic, usually at least the verses needed to perform the contact prayers ([[solat]]). Those who have memorized the entire Quran earn the right to the title of ''[[Hafiz (Quran)|Hafiz]]''.<ref>Kugle (2006), p.47; Esposito (2000a), p.275.</ref> |

Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Quran in the original Arabic, usually at least the verses needed to perform the contact prayers ([[solat]]). Those who have memorized the entire Quran earn the right to the title of ''[[Hafiz (Quran)|Hafiz]]''.<ref>Kugle (2006), p.47; Esposito (2000a), p.275.</ref> |

||

The text of the Quran has become readily accessible over the internet, in Arabic as well as numerous translations in other languages. It can be downloaded and searched both word-by-word and with Boolean algebra. Photos of ancient manuscripts and illustrations of Quranic art can be witnessed. However, there are still limits to searching the Arabic text of the Quran.<ref name=leaman/> |

The [http://www.learningquranonline.com/download-quran.htm text of the Quran] has become readily accessible over the internet, in Arabic as well as numerous translations in other languages. It can be downloaded and searched both word-by-word and with Boolean algebra. Photos of ancient manuscripts and illustrations of Quranic art can be witnessed. However, there are still limits to searching the Arabic text of the Quran.<ref name=leaman/> |

||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> |

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> |

||

Revision as of 22:40, 11 March 2013

| Quran |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

The Quran (English: /kɔːrˈɑːn/[n 1] kor-AHN ; Arabic: القرآن al-qurʾān, IPA: [qurˈʔaːn],[n 2] literally meaning "the recitation", Persian: [ɢoɾˈʔɒːn]), also transliterated Qur'an, Koran, Al-Coran, Coran, Kuran, and Al-Qur'an, is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be the verbatim word of God (Arabic: الله, Allah).[1] It is regarded widely as the finest piece of literature in the Arabic language.[2][3][4][5][6]

Muslims believe the Quran to be verbally revealed through angel Gabriel (Jibril) from God to Muhammad gradually over a period of approximately 23 years beginning on 22 December 609 CE,[7] when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632 CE, the year of his death.[1][8][9]

Muslims regard the Quran as the main miracle of Muhammad, the proof of his prophethood[10] and the culmination of a series of divine messages that started with the messages revealed to Adam, regarded in Islam as the first prophet,[11] and continued with the Scrolls of Abraham (Suhuf Ibrahim),[12] the Tawrat (Torah or Pentateuch) of Moses,[13][14] the Zabur (Tehillim or Book of Psalms) of David,[15][16] and the Injil (Gospel) of Jesus.[17][18][19] The Quran assumes familiarity with major narratives recounted in Jewish and Christian scriptures, summarizing some, dwelling at length on others and in some cases presenting alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[20][21][22] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance, sometimes offering detailed accounts of specific historical events, and often emphasizing the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[23][24]

Etymology and meaning

The word qurʾān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself, assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qaraʾa (قرأ), meaning “he read” or “he recited.” The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā, which refers to “scripture reading” or “lesson”. While most Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qaraʾa itself.[25] In any case, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[1] An important meaning of the word is the “act of reciting”, as reflected in an early Quranic passage: “It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qurʾānahu)”.[26]

In other verses, the word refers to “an individual passage recited [by Muhammad]”. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qurʾān is recited, listen to it and keep silent".[27] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[28]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qurʾān in certain contexts. Such terms include [[[kitab|kitāb]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: (help) (“book”); [[[ayah|āyah]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: (help) (“sign”); and [[[Sura|sūrah]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: (help) (“scripture”). The latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the “revelation” (wahy), that which has been “sent down” (tanzīl) at intervals.[29][30] Other related words are: [[[dhikr]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: (help), meaning "remembrance," used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and [ḥikma] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: (help), meaning “wisdom”, sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[25][31]

The Quran has many other names. Among those found in the text itself are al-furqān (“discernment” or “criterion”), al-hudah (“the guide”), ḏikrallāh (“the remembrance of God”), al-ḥikmah (“the wisdom”), and kalāmallāh (“the word of God”). Another term is al-kitāb (“the book”), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term muṣḥaf ("written work") is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[1]

History

Prophetic era

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in the Cave of Hira during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of twenty-three years. According to hadith and Muslim history, after Muhammad emigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered a considerable number of the sahabah to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. Companions who engaged in the recitation of the Quran were called Qari. Since most sahabah were unable to read or write, they were ordered to learn from the prisoners-of-war the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of sahabah gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most chapters were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. The Quran was completely written in Muhammad's lifetime.[citation needed] However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632.[32][33][34]

Sahih Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and Aisha reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)".[35] The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[36]

The Quran states that Muhammad was ummi,[37] interpreted as illiterate in Muslim tradition. According to Watt, the meaning of the Quranic term ummi is unscriptured rather than illiterate[citation needed].

Compilation

The Holy Quran was written completely in the lifetime of prophet Muhammad.[citation needed] Many of the companions of Muhammad memorized the whole Quran.[citation needed] Based on earlier transmitted reports, shortly after Muhammad's death in the year 632 CE, the first caliph Abu Bakr decided to collect the book in one volume. Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd ibn Thabit, collected the verses and produced several hand-written copies of the complete book. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives.[32][38] Hafsa bint Umar, Muhammad's widow and Caliph Umar's daughter, was entrusted with that Quranic text.[39] In about 650 CE, when the third Caliph Uthman ibn Affan began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quranic, and as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula into Persia, the Levant and North Africa, inorder to preserve the sanctity of the text, ordered a committee to use Hafsa's text and prepare a standard copy of the text of Quran. Thus, within twenty years of Muhammad’s death, the Quran was committed to written form. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.[6][32][40][41] This process of formalization is known as the Uthmanic recension.[42] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[42][33][34][43]

According to Shias and some Sunni scholars, Ali ibn Abi Talib compiled a complete version of the Quran immediately after Muhammad's death.[1] The order of this text differed from that gathered later during Uthman's era in that this version had been collected in chronological order.[44] Despite this, he made no objection against the standardized Quran, but kept his own book.[32][45] Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including ibn Masud's and Ubayy ibn Kab's codex, none of which exist today.[6]

Qur'an most likely existed in scattered written form during the life of the Prophet, Muslim scholars believe that it was written as a complete text at the time of the Prophet’s death.[46] The Quran in its present form is generally considered by academic scholars to record the words spoken by Muhammad because the search for variants has not yielded any differences of great significance.[citation needed] Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are. There has been no critical text produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.[47] Historically, controversy over the Quran's content has rarely become an issue, although debates continue on the subject.[48][49]

In 1972 in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts were discovered that were later proved to be the most ancient Quranic text. The sana'a manuscripts contain palimpsets, a manuscript page from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again, a practice which was common in ancient times due to scarcity of writing material. The faint washed off underlying text, scriptio inferior, however is still barely visible and believed to be "pre-Uthmanic" Quranic content, whilst the text written on top, scriptio superior, is believed to belong to Uthmanic time.[50] Recent studies using radiocarbon dating indicates that the parchments have high probability of belonging to the period between 614 CE to 656 CE.[51][52]

Significance in Islam

Muslims believe the Quran to be the book of divine guidance and direction for humanity and consider the text in its original Arabic to be the literal word of God,[53] revealed to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel over a period of twenty-three years[8][9] and view the Quran as God's final revelation to humanity.[8][54]

Wahy in Islamic and Quranic concept means the act of God addressing an individual, conveying a message for a greater number of recipients. The process by which the divine message comes to the heart of a messenger of God is tanzil (to send down) or nuzul (to come down). As the Quran says, "With the truth we (God) have sent it down and with the truth it has come down." It designates positive religion, the letter of the revelation dictated by the angel to the prophet. It means to cause this revelation to descend from the higher world. According to hadith, the verses were sent down in special circumstances known as asbab al-nuzul. However, in this view God himself is never the subject of coming down.[55]

The Quran frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained, an assertion that Muslims believe. The Quran – often referring to its own textual nature and reflecting constantly on its assertion of divine origin – is the most meta-textual, self-referential religious text.[citation needed] Some verses in the Quran seem to imply that even those who do not speak Arabic would understand the Quran if it were recited to them.[56] The Quran refers to a written pre-text that records God's speech even before it was sent down.[57][58]

The issue of whether the Quran is eternal or created was one of the crucial controversies among early Muslim theologians. Mu'tazilis believe it is created while the most widespread varieties of Muslim theologians consider the Quran to be eternal and uncreated. Sufi philosophers view the question as artificial or wrongly framed.[59]

Muslims maintain the present wording of the Quranic text corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad himself: as the words of God, said to be delivered to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel. Muslims consider the Quran to be a guide, a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. They argue it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Quran, as the Quran itself maintains.

Therefore an Islamic philosopher introduces a prophetology to explain how the divine word passes into human expression. This leads to a kind of esoteric hermeneutics that seeks to comprehend the position of the prophet by mediating on the modality of his relationship not with his own time, but with the eternal source his message emanates from. This view contrasts with historical critique of western scholars who attempt to understand the prophet through his circumstances, education and type of genius.[60]

The Basic Law of Saudi Arabia declares the Quran and sunnah the sole constitutional law of the kingdom.

Uniqueness

Muslims believe that the Quran is different from all other books in ways that are impossible for any other book to be, such that similar texts cannot be written by humans. These include both mundane and miraculous claims. The Quran itself challenges any who disagree with its divine origin to produce a text of a miraculous nature.[61]

Scholars of Islam believe that its poetic form is unique and of a fashion that cannot be written by humans. They also claim it contains accurate prophecy and that no other book does.[62][63][64][65][66]

Text

The Quran consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, each known as a sura. Chapters are classified as Meccan or Medinan, depending on whether the verses were revealed before or after the migration of Muhammad to the city of Medina. Chapter titles are derived from a name or quality discussed in the text, or from the first letters or words of the sura. Generally, longer chapters appear earlier in the Quran, while the shorter ones appear later. The chapter arrangement is thus not connected to the sequence of revelation. Each chapter except the ninth starts with the Bismillah (بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم) an Arabic phrase meaning “In the name of God”. There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the bismillah in the Quran, due to its presence in verse 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba.[67]

Each chapter is formed from several verses, known as ayat, which originally means a “sign” or “evidence” sent by God. The number of verses differs from chapter to chapter. An individual verse may be just a few letters or several lines. The total number of verses in the Quran is 6,236, however, the number varies if the bismillahs are counted separately.

In addition to and independent of the division into chapters, there are various ways of dividing the Quran into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading. The thirty juz' (plural ajza) can be used to read through the entire Quran in a month. Some of these parts are known by names and these names are the first few words by which the juz' starts. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two hizb (plural ahzab), and each hizb subdivided into four rub 'al-ahzab. The Quran is also divided into seven approximately equal parts, manzil (plural manazil), for it to be recited in a week.[1]

Muqatta'at or the Quranic initials are fourteen different letter combinations of 14 Arabic letters that appear in the beginning of 29 chapters of the Quran. The meanings of these initials remain unclear.

According to one estimate the Quran consists of 77430 words, 18994 unique words, 12183 stems, 3382 lemmas and 1685 roots.[68]

Content

The Quranic content is concerned with the basic beliefs of Islam which include the existence of God and the resurrection. Narratives of the early prophets, ethical and legal subjects, historical events of the prophet’s time, charity and prayer also appear in the Quran. The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and the nature of revelation. Historical events are related to outline general moral lessons. Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.[69]

Literary structure

The Quran's message is conveyed with various literary structures and devices. In the original Arabic, the chapters and verses employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. Muslims[who?] assert (according to the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.[70]

The language of the Quran has been described as "rhymed prose" as it partakes of both poetry and prose, however, this description runs the risk of compromising the rhythmic quality of Quranic language, which is certainly more poetic in some parts and more prose-like in others. Rhyme while found throughout the Quran is conspicuous in many of the earlier Meccan chapters, in which relatively short verses throw the rhyming words into prominence. The effectiveness of such a form is evident for instance in chapter 81, and there can be no doubt that these passages impressed the conscience of the hearers. Frequently a change of rhyme from one set of verses to another signals a change in the subject of discussion. Later sections also preserve this form but the style is more expository.[6][71]

The Quranic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its nonlinear structure being akin to a web or net.[1] The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to have lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order and presence of repetition.[72][73] Michael Sells, citing the work of the critic Norman O. Brown, acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming disorganization of Quranic literary expression – its scattered or fragmented mode of composition in Sells's phrase – is in fact a literary device capable of delivering profound effects as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated.[74][75] Sells also addresses the much-discussed repetitiveness of the Quran, seeing this, too, as a literary device.

Interpretation and meanings

Tafsir

The Quran has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication (tafsir), aimed at explaining the "meanings of the Quranic verses, clarifying their import and finding out their significance."[76]

Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities of Muslims. According to the Quran, Muhammad was the first person who described the meanings of verses for early Muslims.[77] Other early exegetes included a few Companions of Muhammad, like Ali ibn Abi Talib, Abdullah ibn Abbas, Abdullah ibn Umar and Ubayy ibn Kab. Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions (hadith) of Muhammad were narrated to make its meaning clear.[78]

Because the Quran is spoken in classical Arabic, many of the later converts to Islam (mostly non-Arabs) did not always understand the Quranic Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims fluent in Arabic and they were concerned with reconciling apparent conflict of themes in the Quran. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Quranic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "abrogating" (nasikh) the earlier text (mansukh).[79][80] Other scholars, however, maintain that no abrogation has taken place in the Qur'an.[81]

Ta'wil

Ja'far Kashfi defines ta'wil as 'to lead back or to bring something back to its origin or archetype'. It is a science whose pivot is a spiritual direction and a divine inspiration, while the tafsir is the literal exegesis of the letter; its pivot is the canonical Islamic sciences.[82] Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei says that according to the popular explanation among the later exegetes, ta'wil indicates the particular meaning a verse is directed towards. The meaning of revelation (tanzil), as opposed to ta'wil, is clear in its accordance to the obvious meaning of the words as they were revealed. But this explanation has become so widespread that, at present, it has become the primary meaning of ta'wil, which originally meant "to return" or "the returning place". In Tabatabaei's view, what has been rightly called ta'wil, or hermeneutic interpretation of the Quran, is not concerned simply with the denotation of words. Rather, it is concerned with certain truths and realities that transcend the comprehension of the common run of men; yet it is from these truths and realities that the principles of doctrine and the practical injunctions of the Quran issue forth. Interpretation is not the meaning of the verse; rather it transpires through that meaning – a special sort of transpiration. There is a spiritual reality, which is the main objective of ordaining a law, or the basic aim in describing a divine attribute—and there is an actual significance a Quranic story refers to.[83][84]

According to Shia beliefs, those who are firmly rooted in knowledge like the Prophet and the imams know the secrets of the Quran. According to Tabatabaei, the statement "none knows its interpretation except Allah"(3:7 ) remains valid, without any opposing or qualifying clause. Therefore, so far as this verse is concerned, the knowledge of the Quran's interpretation is reserved for God. But Tabatabaei uses other verses and concludes that those who are purified by God know the interpretation of the Quran to a certain extent.[84] As Corbin narrates from Shia sources, Ali himself gives this testimony:

Not a single verse of the Quran descended upon (was revealed to) the Messenger of God, which he did not proceed to dictate to me and make me recite. I would write it with my own hand, and he would instruct me as to its tafsir (the literal explanation) and the ta'wil (the spiritual exegesis), the nasikh (the verse that abrogates) and the mansukh (the abrogated verse), the muhkam (without ambiguity) and the mutashabih (ambiguous), the particular and the general...[85]

According to Tabatabaei, there are acceptable and unacceptable esoteric interpretations. Acceptable ta'wil refers to the meaning of a verse beyond its literal meaning; rather the implicit meaning, which ultimately is known only to God and can't be comprehended directly through human thought alone. The verses in question here refer to the human qualities of coming, going, sitting, satisfaction, anger, and sorrow, which are apparently attributed to God. Unacceptable ta'wil is where one "transfers" the apparent meaning of a verse to a different meaning by means of a proof; this method is not without obvious inconsistencies. Although this unacceptable ta'wil has gained considerable acceptance, it is incorrect and cannot be applied to the Quranic verses. The correct interpretation is that reality a verse refers to. It is found in all verses, the decisive and the ambiguous alike; it is not a sort of a meaning of the word; it is a fact that is too sublime for words. God has dressed them with words to bring them a bit nearer to our minds; in this respect they are like proverbs that are used to create a picture in the mind, and thus help the hearer to clearly grasp the intended idea.[84][86]

Therefore Sufi spiritual interpretations are usually accepted by Islamic scholars as authentic, as long as certain conditions are met.[87] In Sufi history, these interpretations were sometimes considered religious innovations (bid'ah), as Salafis believe today. However, ta'wil is extremely controversial even amongst Shia. For example, when Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini, the leader of Islamic revolution, gave some lectures about Sura al-Fatiha in December 1979 and January 1980, protests forced him to suspend them before he could continue beyond the first two verses of the surah.[88]

Levels of meaning

Unlike the Salafis and Zahiri, Shias and Sufis as well as some other Muslim philosophers believe the meaning of the Quran is not restricted to the literal aspect.[89] For them, it is an essential idea that the Quran also has inward aspects. Henry Corbin narrates a hadith that goes back to Muhammad:

"The Qur'an possesses

an external appearance and a hidden depth, an exoteric meaning and

an esoteric meaning. This esoteric meaning in turn conceals an esoteric meaning (this depth possesses a depth, after the image of the celestial Spheres, which are enclosed within each other). So it goes on for seven esoteric meanings (seven depths of hidden depth)."[89]

According to this view, it has also become evident that the inner meaning of the Quran does not eradicate or invalidate its outward meaning. Rather, it is like the soul, which gives life to the body.[90] Corbin considers the Quran to play a part in Islamic philosophy, because gnosiology itself goes hand in hand with prophetology.[91]

Commentaries dealing with the zahir (outward aspects) of the text are called tafsir, and hermeneutic and esoteric commentaries dealing with the batin are called ta'wil (“interpretation” or “explanation”), which involves taking the text back to its beginning. Commentators with an esoteric slant believe that the ultimate meaning of the Quran is known only to God.[1] In contrast, Quranic literalism, followed by Salafis and Zahiris, is the belief that the Quran should only be taken at its apparent meaning.

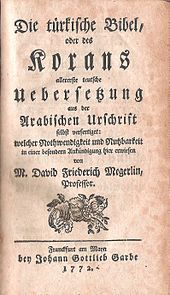

Translations

Translation of the Quran has always been a problematic and difficult issue. Many argue that the Quranic text cannot be reproduced in another language or form.[92] Furthermore, an Arabic word may have a range of meanings depending on the context, making an accurate translation even more difficult.[44]

Nevertheless, the Quran has been translated into most African, Asian and European languages.[44] The first translator of the Quran was Salman the Persian, who translated sura Al-Fatiha into Persian during the 7th century.[93] The first complete translation of the Quran was completed in 884 CE in Alwar (Sindh, India now Pakistan) by the orders of Abdullah bin Umar bin Abdul Aziz on the request of the Hindu Raja Mehruk.[94] The first complete translation of Quran was into Persian during the reign of Samanids in the 9th century. Islamic tradition holds that translations were made for Emperor Negus of Abyssinia and Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, as both received letters by Muhammad containing verses from the Quran.[44] In early centuries, the permissibility of translations was not an issue, but whether one could use translations in prayer.

In 1936, translations in 102 languages were known.[44] In 2010, the Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review reported that the Quran was presented in 112 languages at the 18th International Quran Exhibition in Tehran.[95]

Robert of Ketton's 1143 translation of the Quran for Peter the Venerable, Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete, was the first into a Western language (Latin).[96] Alexander Ross offered the first English version in 1649, from the French translation of L'Alcoran de Mahomet (1647) by Andre du Ryer. In 1734, George Sale produced the first scholarly translation of the Quran into English; another was produced by Richard Bell in 1937, and yet another by Arthur John Arberry in 1955. All these translators were non-Muslims. There have been numerous translations by Muslims.

The English translators have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; for example, two widely read translators, A. Yusuf Ali and M. Marmaduke Pickthall, use the plural and singular "ye" and "thou" instead of the more common "you".[97]

Literary usage

Recitation

...and recite the Quran in slow, measured rhythmic tones.

One meaning of Quran is "recitation". Tajwid, an Arabic word for elocution, is a set of rules that governs how the Quran should be recited and is assessed in terms of how accessible the recitation is to those intent on concentrating on the words.[44]

To perform salat (prayer), a mandatory obligation in Islam, a Muslim is required to learn at least some sura of the Quran (typically starting with the first one, al-Fatiha, known as the "seven oft-repeated verses," and then moving on to the shorter ones at the end). Until one has learned al-Fatiha, a Muslim can only say phrases like "praise be to God" during the salat.

A person whose recital repertoire encompasses the whole Quran is called a qari', whereas a memoriser of the Quran is called a hafiz (fem. Hafaz) (which translate as "reciter" or "protector," respectively). Muhammad is regarded as the first qari' since he was the first to recite it. Recitation (tilawa تلاوة) of the Quran is a fine art in the Muslim world.

Schools of recitation

There are several schools of Quranic recitation, all of which teach possible pronunciations of the Uthmanic rasm: Seven reliable, three permissible and (at least) four uncanonical – in 8 sub-traditions each – making for 80 recitation variants altogether.[98] A canonical recitation must satisfy three conditions:

- It must match the rasm, letter for letter.

- It must conform with the syntactic rules of the Arabic language.

- It must have a continuous isnad to Muhammad through tawatur, meaning that it has to be related by a large group of people to another down the isnad chain.

These recitations differ in the vocalization (tashkil) of a few words, which in turn gives a complementary meaning to the word in question according to the rules of Arabic grammar. For example, the vocalization of a verb can change its active and passive voice. It can also change its stem formation, implying intensity for example. Vowels may be elongated or shortened, and glottal stops (hamzas) may be added or dropped, according to the respective rules of the particular recitation. For example, the name of archangel Gabriel is pronounced differently in different recitations: Jibrīl, Jabrīl, Jibra'īl, and Jibra'il.

The more widely used narrations are those of Hafs (حفص عن عاصم), Warsh (ورش عن نافع), Qaloon (قالون عن نافع) and Al-Duri according to Abu `Amr (الدوري عن أبي عمرو). Muslims firmly believe that all canonical recitations were recited by Muhammad himself, citing the respective isnad chain of narration, and accept them as valid for worshipping and as a reference for rules of Sharia. The uncanonical recitations are called "explanatory" for their role in giving a different perspective for a given verse or ayah. Today several dozen persons hold the title "Memorizer of the Ten Recitations."

The presence of these different recitations is attributed to many hadith. Malik Ibn Anas has reported:[99]

- Abd al-Rahman Ibn Abd al-Qari narrated: "Umar Ibn Khattab said before me: I heard Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one I used to read it, and the Prophet (sws) himself had read out this surah to me. Consequently, as soon as I heard him, I wanted to get hold of him. However, I gave him respite until he had finished the prayer. Then I got hold of his cloak and dragged him to the Prophet (sws). I said to him: "I have heard this person [Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam] reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one you had read it out to me." The Prophet (sws) said: "Leave him alone [O 'Umar]." Then he said to Hisham: "Read [it]." [Umar said:] "He read it out in the same way as he had done before me." [At this,] the Prophet (sws) said: "It was revealed thus." Then the Prophet (sws) asked me to read it out. So I read it out. [At this], he said: "It was revealed thus; this Quran has been revealed in Seven Ahruf. You can read it in any of them you find easy from among them.

Suyuti, a famous 15th century Islamic theologian, writes after interpreting above hadith in 40 different ways:[100]

- "And to me the best opinion in this regard is that of the people who say that this hadith is from among matters of mutashabihat, the meaning of which cannot be understood."

Many reports contradict the presence of variant readings:[101]

- Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami reports, "the reading of Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Zayd ibn Thabit and that of all the Muhajirun and the Ansar was the same. They read the Quran according to the Qira'at al-'ammah. This is the same reading the Prophet (sws) read twice to Gabriel in the year of his death. Zayd ibn Thabit was also present in this reading [called] the 'Ardah-i akhirah. It was this very reading that he taught the Quran to people till his death".[102]

- Ibn Sirin writes, "the reading on which the Quran was read out to the prophet in the year of his death is the same according to which people are reading the Quran today".[103]

Javed Ahmad Ghamidi also purports that there is only one recitation of Quran, which is called Qira'at of Hafss or in classical scholarship, it is called Qira'at al-'ammah. The Quran has also specified that it was revealed in the language of Muhammad's tribe: the Quraysh.[Quran 19:97][Quran 44:58][101]

However, the identification of the recitation of Hafss as the Qira'at al-'ammah is somewhat problematic when that was the recitation of the people of Kufa in Iraq, and there is better reason to identify the recitation of the reciters of Madinah as the dominant recitation. The reciter of Madinah was Nafi' and Imam Malik remarked "The recitation of Nafi' is Sunnah."

Writing and printing

Writing

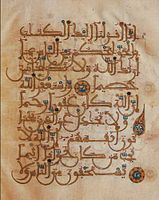

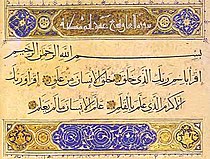

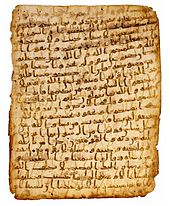

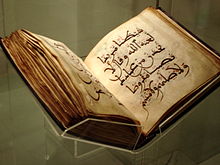

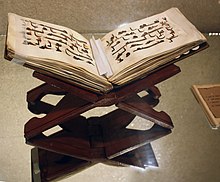

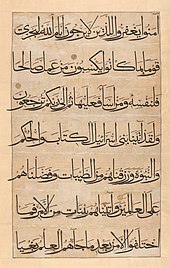

Before printing was widely adopted in the 19th century, the Quran was transmitted in manuscripts made by calligraphers and copyists. The earliest manuscripts were written in hijazi type script. The hijazi style manuscripts nevertheless confirm that transmission of the Quran in writing began at an early stage. Probably in the ninth century scripts began to feature thicker strokes, which are traditionally known as Kufic scripts. Toward the end of the ninth century, new scripts began to appear in copies of the Quran and replace earlier scripts. The reason for discontinuation in the use of the earlier style was that it took too long to produce and the demand for copies was increasing. Copyists would therefore chose simpler writing styles. From the eleventh century, the styles of writing employed were primarily the Naskhi, muhaqqaq, rayhani and on rarer occasions the thuluth script. Naskhi was in very widespread use. In North Africa and Spain the maghribi style was popular. More distinct is the bihari script which was used solely in the north of India. Nastaliq style was also rarely used in Persian world.[104][6]

In the beginning the Quran did not have vocalization markings. The system of vocalization as we know it today seems to have been introduced towards the end of the ninth century. Since it would have been too costly for most Muslims to purchase a manuscript, copies of the Quran were held in mosques in order to make them accessible to people. These copies frequently took the form of a series of thirty parts or Juz'. In terms of productivity the Ottoman copyists would provide the best example. This was in response to widespread demand, unpopularity of printing methods, and for aesthetic reasons.[105]

-

Kufic script, 8th-9th century, Ink and color on parchment

-

muhaqaq script, 14th-15th century

-

maghribi script, 13th - 14th Century

-

shikasta nastaliq,18th-19th centuries

Printing

Short extracts from the Quran were printed as early as the tenth century in various parts of the Muslim world with a method known as wood-block printing. In this technique a page is carved in a wooden block, one block per page. A similar technique was widely used in China.[106] Another technique, known as movable-type printing, was used to print the Quran in Venice around 1537. Two more editions include those published by the pastor Abraham Hinckelmann in Hamburg in 1694 and by Italian priest Ludovico Maracci in Padua in 1698. The latter print included an accurate Latin translation. In 1787 in Saint Petersburg, Catherine the Great of Russia, sponsored a print of the Quran by a Muslim scholar named Mullah Osman Ismail. This was followed by editions from Kazan (1803), Tehran (1828) and Istanbul (1877). Gustav Flügel published an edition of the Quran in 1834 in Leipzig, which became popular in Europe. This edition provided a large number of readers with access to a reliable text and was referred to for a long time thereafter, until the publication of an edition of the Quran in Cairo in 1924 which was the result of a long preparation process by scholars from al-Azhar university. This edition which standardized the orthography of the Quran is the basis of current editions of the Quran.[107][6]

Relationship with other literature

The Bible

It is He Who sent down to thee (step by step), in truth, the Book, confirming what went before it; and He sent down the Law (of Moses) and the Gospel (of Jesus) before this, as a guide to mankind, and He sent down the criterion (of judgment between right and wrong).[108]

The Quran speaks well of the relationship it has with former books (the Torah and the Gospel) and attributes their similarities to their unique origin and saying all of them have been revealed by the one God.[109]

According to Sahih Bukhari, the Quran was recited among Levantines and Iraqis, and discussed by Christians and Jews before it was standardized.[110] Its language was similar to the Syriac language. The Quran recounts stories of many of the people and events recounted in Jewish and Christian sacred books (Tanakh, Bible) and devotional literature (Apocrypha, Midrash), although it differs in many details. Adam, Enoch, Noah, Eber, Shelah, Abraham, Lot, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Job, Jethro, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Jonah, Aaron, Moses, Zechariah, John the Baptist, and Jesus are mentioned in the Quran as prophets of God (see Prophets of Islam). In fact, Moses is mentioned more in the Quran than any other individual.[111] Jesus is mentioned more often in the Quran than Muhammad while Mary is mentioned in the Quran more than the New Testament.[112] Muslims believe the common elements or resemblances between the Bible and other Jewish and Christian writings and Islamic dispensations is due to their common divine source, and that the original Christian or Jewish texts were authentic divine revelations given to prophets.

Similarities with Christian apocrypha

The Quran has been noted to have certain narratives similarities to the Diatessaron, Protoevangelium of James, Infancy Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the Arabic Infancy Gospel.[113][114][115] One scholar has suggested that the Diatessaron, as a gospel harmony, may have led to the conception that the Christian Gospel is one text.[116]

Arab writing

After the Quran, and the general rise of Islam, the Arabic alphabet developed rapidly into an art form.[44]

Wadad Kadi, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at University of Chicago and Mustansir Mir, Professor of Islamic studies at Youngstown State University state that:[117]

Although Arabic, as a language and a literary tradition, was quite well developed by the time of Muhammad's prophetic activity, it was only after the emergence of Islam, with its founding scripture in Arabic, that the language reached its utmost capacity of expression, and the literature its highest point of complexity and sophistication. Indeed, it probably is no exaggeration to say that the Quran was one of the most conspicuous forces in the making of classical and post-classical Arabic literature.

The main areas in which the Qur'an exerted noticeable influence on Arabic literature are diction and themes; other areas are related to the literary aspects of the Qur'an particularly oaths (q.v.), metaphors, motifs, and symbols. As far as diction is concerned, one could say that Qur'anic words, idioms, and expressions, especially "loaded" and formulaic phrases, appear in practically all genres of literature and in such abundance that it is simply impossible to compile a full record of them. For not only did the Qur'an create an entirely new linguistic corpus to express its message, it also endowed old, pre-Islamic words with new meanings and it is these meanings that took root in the language and subsequently in the literature...

Culture

Respect for the written text of the Quran is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims. They believe that intentionally insulting the Quran is a form of blasphemy.[citation needed]

Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Quran in the original Arabic, usually at least the verses needed to perform the contact prayers (solat). Those who have memorized the entire Quran earn the right to the title of Hafiz.[118]

The text of the Quran has become readily accessible over the internet, in Arabic as well as numerous translations in other languages. It can be downloaded and searched both word-by-word and with Boolean algebra. Photos of ancient manuscripts and illustrations of Quranic art can be witnessed. However, there are still limits to searching the Arabic text of the Quran.[44]

-

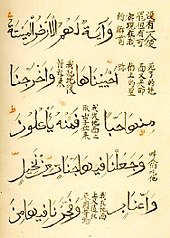

Arabic Quran with Persian translation.

-

Arabic Quran with Persian translation from the Ilkhanid Era.

-

Quran with colour-coded tajwid rules.

Treatment and disposal of the book

Most Muslims treat paper copies of the Quran with reverence.[119] Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of sura 56:77–79: "That this is indeed a Quran Most Honourable, In a Book well-guarded, Which none shall touch but those who are clean", many scholars believe that a Muslim must perform a ritual cleansing with water (wudu) before touching a copy of the Quran, or mus'haf, although this view is not universal.

Defiling or dismembering copies of the Quran is considered Quran desecration. Pulping, recycling, or otherwise discarding worn-out copies of the text is forbidden. Worn-out, torn, or errant (for example, pages out of order) Qurans are left free to flow in a river, kept somewhere safe, burned, or buried in a remote location.[120]

See also

- History of the Qur'an

- Tafsir of the Qur'an

- Quran and miracles

- Women in the Qur'an

- Persons related to Qur'anic verses

- Legends and the Qur'an

- Criticism of the Qur'an

- List of religious texts

- Qur'anic literalism

- Quran and Sunnah

- Qur'an alone

- Quran reading

- 2010 Qur'an-burning controversy

- Dhikr

- Digital Qur'an

- Hafiz

Notes

- ^[n 1] The English pronunciation varies: /kəˈrɑːn/, /kəˈræn/, /kɔːrˈɑːn/, /kɔːrˈæn/, /koʊˈrɑːn/, /koʊˈræn/;[121] especially with the spelling quran /kʊrˈɑːn/, /kʊrˈæn/;[122] especially in British English /kɒrˈɑːn/.[123][124]

- [[#ref_2|^/qurˈʔaːn/]] : Actual pronunciation in Literary Arabic varies regionally. The first vowel varies from [o] to [ʊ] to [u], while the second vowel varies from [æ] to [a] to [ɑ]. Example, in Egypt: [qorˤˈʔɑːn], in Central East Arabia: [qʊrˈʔæːn].

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ Chejne, A. (1969) The Arabic Language: Its Role in History, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- ^ Nelson, K. (1985) The Art of Reciting the Quran, University of Texas Press, Austin

- ^ Speicher, K. (1997) in: Edzard, L., and Szyska, C. (eds.) Encounters of Words and Texts: Intercultural Studies in Honor of Stefan Wild. Georg Olms, Hildesheim, pp. 43–66.

- ^ Taji-Farouki, S. (ed.) (2004) Modern Muslim Intellectuals and the Quran, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- ^ a b c d e f g Rippin, Andrew; et al. (2006). The Blackwell companion to the Qur'an ([2a reimpr.] ed.). Blackwell. ISBN 978140511752-4.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help)- see section Poetry and Language by Navid Kermani, p.107-120.

- For writing and printing, see section Written Transmission by François Déroche, p.172-187.

- For literary structure, see section Language by Mustansir Mir, p.93.

- For the history of compilation see Introduction by Tamara Sonn p.5-6

- ^ Chronology of Prophetic Events, Fazlur Rehman Shaikh (2001) p.50 Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd.

- ^ a b c Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths, Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers.

- ^ a b Quran 17:106

- ^ Peters (2003), pp.12 and 13[full citation needed]

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: an introduction to the Quran and Muslim exegesis. Continuum. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- ^ Quran 87:18–19

- ^ Quran 3:3

- ^ Quran 5:44

- ^ Quran 4:163

- ^ Quran 17:55

- ^ Quran 5:46

- ^ Quran 5:110

- ^ Quran 57:27

- ^ Quran 3:84

- ^ Quran 4:136

- ^ “The Quran assumes the reader is familiar with the traditions of the ancestors since the age of the Patriarchs, not necessarily in the version of the ‘Children of Israel’ as described in the Bible but also in the version of the ‘Children of Ismail’ as recounted orally, interspersed with polytheist elements, at the time of Muhammad. The term jahiliya (ignorance), used to speak of the pre-Islamic epoch, does not imply that the Arabs were not familiar with their traditional roots but that their knowledge of ethical and spiritual values had been lost.” Exegesis of Bible and Qur'an, H. Krausen. Webcitation.org[unreliable source]

- ^ Nasr (2003), p.42[full citation needed]

- ^ Quran 2:67–76

- ^ a b “Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online.

- ^ Quran 75:17

- ^ Quran 7:204

- ^ See “Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online and [Quran 9:111]

- ^ Quran 20:2 cf.

- ^ Quran 25:32 cf.

- ^ According to Welch in the Encyclopedia of Islam, the verses pertaining to the usage of the word hikma should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that “Muhammad is to judge (tahkum) mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him.”

- ^ a b c d *Tabatabaee, 1988, chapter 5[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Richard Bell (Revised and Enlarged by W. Montgomery Watt) (1970). Bell's introduction to the Qur'an. Univ. Press. pp. 31–51. ISBN 0852241712.

- ^ a b c P. M. Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis (1970). The Cambridge history of Islam (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780521291354.

- ^ Translation of Sahih Bukhari, Book 1. Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. "Allah's Apostle replied, 'Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell, this form of Inspiration is the hardest of all and then this state passes off after I have grasped what is inspired. Sometimes the Angel comes in the form of a man and talks to me and I grasp whatever he says.' 'Aisha added: Verily I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the Sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam online, Muhammad article

- ^ Quran 7:157

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 6:60:201

- ^ http://www.quran.net/quran/PreservationOfTheQuran.htm

- ^ Mohamad K. Yusuff, Zayd ibn Thabit and the Glorious Qur'an

- ^ The Koran; A Very Short Introduction, Michael Cook. Oxford University Press, pp. 117–124

- ^ a b "CRCC: Center For Muslim-Jewish Engagement: Resources: Religious Texts". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: “Few have failed to be convinced that … the Quran is … the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation.”

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Leaman, Oliver (2006). The Qur'an: an Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32639-7..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); line feed character in|title=at position 16 (help)- For searching the arabic text on the internet and writing, see Cyberspace and the Qur'an by Andrew Rippin, p.159-163.

- For calligraphy, see by Calligraphy and the Qur'an by Oliver leaman, p 130-135.

- For translation, see Translation and the Qur'an by Afnan Fatani, p.657-669.

- For recitation, see Art and the Qur'an by Tamara Sonn, p.71-81.

- ^ See:

- Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in San'a

- The Qur'an as Text, ed. Wild, Brill, 1996 ISBN 978-90-04-10344-3

- ^ Esack, Farid (2005). The Qur'an: A User's Guide. Oxford England: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-345-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ For both the claim that variant readings are still transmitted and the claim that no such critical edition has been produced, see Gilliot, C., "Creation of a fixed text" in McAuliffe, J. D. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'ān (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 52.

- ^ Arthur Jeffery and St. Clair-Tisdal et al,Edited by Ibn Warraq, Summarised by Sharon Morad, Leeds. "The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islam's Holy Book". Retrieved 2011-03-15.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ *F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: "Few have failed to be convinced that the Quran is the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation."

- ^ "'The Qur'an: Text, Interpretation and Translation' 3rd Biannual SOAS Conference, October 16–17, 2003". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 6 (1): 143–145. 2004. doi:10.3366/jqs.2004.6.1.143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bergmann, Uwe (2010). "The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurān of the Prophet". Arabica. 57 (4): 343–436. doi:10.1163/157005810X504518.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sadeghi, Behnam (2012). "Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān". Der Islam. 87 (1–2): 1–129. doi:10.1515/islam-2011-0025.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Quran 2:23–4

- ^ Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 978-0-340-58795-9

- ^ See:

- Corbin (1993), p.12[full citation needed]

- Wild (1996), pp. 137, 138, 141 and 147[full citation needed]

- Quran 2:97

- Quran 17:105

- ^ Jenssen, H., "Arabic Language" in McAuliffe et al. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān, vol. 1 (Brill, 2001), pp. 127-135.

- ^ Wild (1996), pp. 140

- ^ Quran 43:3

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.10

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp .10 and 11

- ^ [Quran 17:88]

- ^ [Quran 2:23]

- ^ [Quran 10:38]

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an – Miracles

- ^ Ahmad Dallal, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Qur'an and science

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an – Byzantines

- ^ See:

- “Kur`an, al-”, Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- Allen (2000) p. 53

- ^ Dukes, Kais. "RE: Number of Unique Words in the Quran". www.mail-archive.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Saeed, Abdullah (2008). The Qurʼan : an introduction. London: Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9780415421249.

- ^ Issa Boullata, "Literary Structure of Quran," Encyclopedia of the Qurʾān, vol.3 p.192, 204

- ^ Jewishencyclopedia.com – Körner, Moses B. Eliezer

- ^ "The final process of collection and codification of the Quran text was guided by one over-arching principle: God's words must not in any way be distorted or sullied by human intervention. For this reason, no serious attempt, apparently, was made to edit the numerous revelations, organize them into thematic units, or present them in chronological order.... This has given rise in the past to a great deal of criticism by European and American scholars of Islam, who find the Quran disorganized, repetitive, and very difficult to read." Approaches to the Asian Classics, Irene Blomm, William Theodore De Bary, Columbia University Press, 1990, p. 65

- ^ Samuel Pepys: "One feels it difficult to see how any mortal ever could consider this Quran as a Book written in Heaven, too good for the Earth; as a well-written book, or indeed as a book at all; and not a bewildered rhapsody; written, so far as writing goes, as badly as almost any book ever was!" http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/display.php?table=review&id=21

- ^ Michael Sells, Approaching the Qur'ān (White Cloud Press, 1999)

- ^ Norman O. Brown, "The Apocalypse of Islam." Social Text 3:8 (1983–1984)

- ^ Preface of Al'-Mizan, reference is to Allameh Tabatabaei [dead link]

- ^ Quran 2:151

- ^ Tafseer Al-Mizan [dead link]

- ^ How can there be abrogation in the Quran?

- ^ Are the verses of the Qur'an Abrogated and/or Substituted?

- ^ Islahi, Amin Ahsan. Tadabbur-i-Qur'an (Pondering over the Qur'an) (in Urdu (tr: English)). Retrieved 14 August 2011.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Corbin (1993), p.9

- ^ Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, The Principles of Interpretation of the Quran [dead link]

- ^ a b c Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, Topic: Decisive and Ambiguous verses and "ta'wil" [dead link]

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.46

- ما نَزلت على رسول الله صلى الله عليه وآله وسلم آية من القرآن إلاّ أقرأنيها وأملاها عليَّ فكتبتها بخطي ، وعلمني تأويلها وتفسيرها، وناسخها ومنسوخها ، ومحكمها ومتشابهها ، وخاصّها وعامّها ، ودعا الله لي أن يعطيني فهمها وحفظها فما نسيتُ آية من كتاب الله تعالى ولا علماً أملاه عليَّ وكتبته منذ دعا الله لي بما دعا ، وما ترك رسول الله علماً علّمه الله من حلال ولا حرام ، ولا أمرٍ ولا نهي كان أو يكون.. إلاّ علّمنيه وحفظته، ولم أنسَ حرفاً واحداً منه

- ^ Tabatabaee (1988), pp. 37–45

- ^ Sufi Tafsir and Isma'ili Ta'wil

- ^ Algar, Hamid (June 2003), The Fusion of the Gnostic and the Political in the Personality and Life of Imam Khomeini (R.A.)

- ^ a b Corbin (1993), p.7

- ^ Tabatabaee, Tafsir Al-Mizan [dead link]

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.13

- ^ Aslan, Reza (20 November 2008). "How To Read the Quran". Slate. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380.

- ^ Monthlycrescent.com

- ^ "More than 300 publishers visit Quran exhibition in Iran". Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review. 12 August 2010.

- ^ Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2002. p. 42.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Surah 3 – Read Quran Online". Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Navid Kermani, Das ästhetische Erleben des Koran. Munich (1999)

- ^ Malik Ibn Anas, Muwatta, vol. 1 (Egypt: Dar Ahya al-Turath, n.d.), 201, (no. 473).

- ^ Suyuti, Tanwir al-Hawalik, 2nd ed. (Beirut: Dar al-Jayl, 1993), 199.

- ^ a b Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. Mizan, Principles of Understanding the Qur'an, Al-Mawrid

- ^ Zarkashi, al-Burhan fi Ulum al-Quran, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1980), 237.

- ^ Suyuti, al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Quran, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Baydar: Manshurat al-Radi, 1343 AH), 177.

- ^ Peter G. Riddell, Tony Street, Anthony Hearle Johns, Islam: essays on scripture, thought, and society : a festschrift in honour of Anthony H. Johns, pp. 170–174, BRILL, 1997, ISBN 978-90-04-10692-5, ISBN 978-90-04-10692-5

- ^ Suraiya Faroqhi, Subjects of the Sultan: culture and daily life in the Ottoman Empire, pp, 134–136, I.B.Tauris, 2005, ISBN 978-1-85043-760-4, ISBN 978-1-85043-760-4;The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Fascicules 111–112 : Masrah Mawlid, Clifford Edmund Bosworth

- ^ Muslim Printing Before Gutenberg

- ^ The Qur'an in Manuscript and Print. "The Qur'anic Script". Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ 3:3 نزل عليك الكتاب بالحق مصدقا لما بين يديه وانزل التوراة والانجيل

- ^ Quran 2:285

- ^ USC.edu [dead link]

- ^ Annabel Keeler, "Moses from a Muslim Perspective", in: Solomon, Norman; Harries, Richard; Winter, Tim (eds.), Abraham's children: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in conversation, by. T&T Clark Publ. (2005), pp. 55 - 66.

- ^ Esposito, John L. The Future of Islam. Oxford University Press US, 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-516521-0 p. 40

- ^ Christian Lore and the Arabic Qur'an by Signey Griffith, p.112, in The Qurʼān in its historical context, Gabriel Said Reynolds, ed. Psychology Press, 2008

- ^ Qur'an-Bible Comparison: A Topical Study of the Two Most Influential and Respectful Books in Western and Middle Eastern Civilizations by Ami Ben-Chanan, p. 197–198, Trafford Publishing, 2011

- ^ New Catholic Encyclopaedia, 1967, The Catholic University of America, Washington D C, Vol. VII, p.677

- ^ "On pre-Islamic Christian strophic poetical texts in the Koran" by Ibn Rawandi, found in What the Koran Really Says: Language, Text, and Commentary, Ibn Warraq, Prometheus Books, ed. ISBN 978-1-57392-945-5

- ^ Wadad Kadi and Mustansir Mir, Literature and the Quran, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, vol. 3, pp. 213, 216

- ^ Kugle (2006), p.47; Esposito (2000a), p.275.

- ^ Mahfouz (2006), p.35

- ^ Afghan Quran-burning protests: What’s the right way to dispose of a Quran? - Slate Magazine

- ^ dictionary.reference.com: koran

- ^ dictionary.reference.com: quran

- ^ Cambridge dictionary: koran

- ^ Cambridge dictionary: quran

References

- Rahman, Fazlur (2009) [1989]. Major Themes of the Qur'an (Second ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70286-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allen, Roger (2000). An Introduction to Arabic literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77657-8.

- Corbin, Henry (1993 (original French 1964)). History of Islamic Philosophy, Translated by Liadain Sherrard, Philip Sherrard. London; Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications for The Institute of Ismaili Studies. ISBN 978-0-7103-0416-2.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Esposito, John (2000). Muslims on the Americanization Path?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513526-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kugle, Scott Alan (2006). Rebel Between Spirit And Law: Ahmad Zarruq, Sainthood, And Authority in Islam. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34711-4.

- Mahfouz, Tarek (2006). Speak Arabic Instantly. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-84728-900-1.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2003). Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-050714-5.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Peters, Francis E. (2003). The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12373-8.

- Peters, F. E. (1991). "The Quest of the Historical Muhammad". International Journal of Middle East Studies.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn. Tafsir al-Mizan.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1988). The Qur'an in Islam: Its Impact and Influence on the Life of Muslims. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0266-3.

- Wild, Stefan (1996). The Quʼran as Text. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09300-3.

Further reading

Recent translations

- M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (2008). The Qur'an (Reissue ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199535957.

- Khalidi, Tarif (2009). The Qur'an: A New Translation. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-310588-6.

Introductory texts

- Robinson, Neal, Discovering the Qur'an, Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1-58901-024-6

- Sells, Michael, Approaching the Qur'ān: The Early Revelations, White Cloud Press, Book & CD edition (November 15, 1999). ISBN 978-1-883991-26-5

- Bell, Richard (1970). Bell's introduction to the Qurʼān. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0597-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rahman, Fazlur (2009) [1989]. Major Themes of the Qur'an (Second ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70286-5.

Traditional Quranic commentaries (tafsir)

- Al-Tabari, Jamiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwil al-Qurʾān, Cairo 1955–69, transl. J. Cooper (ed.), The Commentary on the Qurʾān, Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-19-920142-6

Topical studies

- Stowasser, Barbara Freyer – Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation, Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (June 1, 1996), ISBN 978-0-19-511148-4

- Gibson, Dan (2011). Qur’anic Geography: A Survey and Evaluation of the Geographical References in the Qur’an with Suggested Solutions for Various Problems and Issues. Independent Scholars Press, Canada. ISBN 978-0-9733642-8-6.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (1991). Qurʼānic Christians : an analysis of classical and modern exegesis. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36470-6.

Literary criticism

- M. M. Al-Azami (2003). The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments (First ed.). UK Islamic Academy. ISBN 1-872531-65-2.

- Gunter Luling. A challenge to Islam for reformation: the rediscovery and reliable reconstruction of a comprehensive pre-Islamic Christian hymnal hidden in the Koran under earliest Islamic reinterpretations. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers 2003. (580 Seiten, lieferbar per Seepost). ISBN 978-81-208-1952-8

- Luxenberg, Christoph (2004). The Syro-Aramaic Reading Of The Koran: a contribution to the decoding of the language of the Koran, Berlin, Verlag Hans Schiler, 1 May 2007 ISBN 978-3-89930-088-8

- Puin, Gerd R.. "Observations on Early Quran Manuscripts in Sana'a," in The Qurʾan as Text, ed. Stefan Wild, E. J. Brill 1996, pp. 107–111.

- Wansbrough, John. Quranic Studies, Oxford University Press, 1977

Encyclopedias

- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Jane Dammen McAuliffe et al. (eds.) (1st ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. 2001–2006. ISBN 978-90-04-11465-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Oliver Leaman et al. (eds.) (1st ed.). Routledge. 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-77529-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - The Integrated Encyclopedia of the Qur’an. Muzaffar Iqbal et al. (eds.) (1st ed.). Center for Islamic Sciences. 2013-01. ISBN 978-1-926620-00-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: others (link)

Academic journals

- "Journal of Qur'anic Studies / Majallat al-dirāsāt al-Qurʹānīyah". School of Oriental and African Studies. 1999–present. ISSN 1465-3591.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Journal of Qur'anic Research and Studies". Medina, Saudi Arabia: King Fahd Qur'an Printing Complex. 2006–present.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

Qur'an browsers and translations

- Quran.com

- Al-Quran.info

- Tanzil – Online Quran Navigator

- Multilingual Quran (Arabic, English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Italian)

Word-for-word analysis

- Quranic Arabic Corpus, shows syntax and morphology for each word.

- Word for Word English Translation – emuslim.com

Manuscripts

Other resources

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA