Wine

- For a topical guide to this subject, see Outline of wine.

Wine is an alcoholic beverage typically made of fermented grape juice.[1] The natural chemical balance of grapes is such that they can ferment without the addition of sugars, acids, enzymes or other nutrients.[2] Wine is produced by fermenting crushed grapes using various types of yeast. Yeast consumes the sugars found in the grapes and converts them into alcohol. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are used depending on the type of wine being produced.[3]

Although other fruits such as apples and berries can also be fermented, the resultant wines are normally named after the fruit from which they are produced (for example, apple wine or elderberry wine) and are generically known as fruit wine or country wine (not to be confused with the French term vin de pays). Others, such as barley wine and rice wine (i.e., sake), are made from starch-based materials and resemble beer and spirit more than wine, while ginger wine is fortified with brandy. In these cases, the use of the term "wine" is a reference to the higher alcohol content, rather than production process.[4] The commercial use of the English word "wine" (and its equivalent in other languages) is protected by law in many jurisdictions.[5]

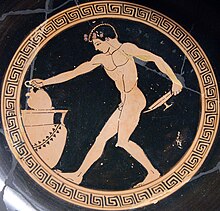

Wine has a rich history dating back to around 6000 BC and is thought to have originated in areas now within the borders of Georgia and Iran.[6][7] Wine probably appeared in Europe at about 4500 BC in what is now Bulgaria and Greece, and was very common in ancient Greece, Thrace and Rome. Wine has also played an important role in religion throughout history. The Greek god Dionysos and the Roman equivalent Bacchus represented wine, and the drink is also used in Christian and Jewish ceremonies such as the Eucharist (also called the Holy Communion) and Kiddush.

The word "wine" derives from the Proto-Germanic "*winam," an early borrowing from the Latin vinum, "wine" or "(grape) vine," itself derived from the Proto-Indo-European stem *win-o- (cf. Hittite: wiyana ,Lycian: Oino, Ancient Greek οῖνος - oînos, Aeolic Greek ϝοίνος - woinos).[8][9]

History

Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest production of wine, made by fermenting grapes, took place in sites in Georgia and Iran, from as early as 6000 BC.[6][7] These locations are all within the natural area of the European grapevine Vitis vinifera.

A 2003 report by archaeologists indicates a possibility that grapes were used together with rice to produce mixed fermented beverages in China as early as 7000 BC. Pottery jars from the Neolithic site of Jiahu, Henan were found to contain traces of tartaric acid and other organic compounds commonly found in wine. However, other fruits indigenous to the region, such as hawthorn, could not be ruled out.[10][11] If these beverages, which seem to be the precursors of rice wine, included grapes rather than other fruits, these grapes were of any of the several dozen indigenous wild species of grape in China, rather than from Vitis vinifera, which were introduced into China some 6000 years later.[10]

The oldest known evidence of wine production in Europe is dated to 4500 BC and comes from archaeological sites in Greece.[12][13] The same sites also contain the world’s earliest evidence of crushed grapes.[12] In Ancient Egypt, six of 36 wine amphoras were found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun bearing the name "Kha'y", a royal chief vintner. Five of these amphoras were designated as from the King's personal estate with the sixth listed as from the estate of the royal house of Aten.[14] Traces of wine have also been found in central Asian Xinjiang, dating from the second and first millennia BC.[15]

In medieval Europe, the Roman Catholic Church was a staunch supporter of wine since it was necessary for the celebration of Mass. Monks in France made wine for years, storing it underground in caves to age.[16] There is an old English recipe which survived in various forms until the nineteenth century for refining white wine using Bastard—bad or tainted bastardo wine.[17] Wine was forbidden during the Islamic Golden Age, until Geber and other Muslim chemists pioneered its distillation for cosmetic and medical uses.[18]

Grape varieties

Wine is usually made from one or more varieties of the European species Vitis vinifera, such as Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. When one of these varieties is used as the predominant grape (usually defined by law as a minimum of 75% or 85%), the result is a varietal, as opposed to a blended, wine. Blended wines are not necessarily considered inferior to varietal wines; some of the world's most expensive wines, from regions like Bordeaux and the Rhone Valley, are blended from different grape varieties of the same vintage.[citation needed]

Wine can also be made from other species of grape or from hybrids, created by the genetic crossing of two species. Vitis labrusca (of which the Concord grape is a cultivar), Vitis aestivalis, Vitis rupestris, Vitis rotundifolia and Vitis riparia are native North American grapes usually grown for consumption as fruit or for the production of grape juice, jam, or jelly, but sometimes made into wine.

Hybridization is not to be confused with the practice of grafting. Most of the world's vineyards are planted with European V. vinifera vines that have been grafted onto North American species rootstock. This is common practice because North American grape species are resistant to phylloxera, a root louse that eventually kills the vine. In the late 19th century, Europe's vineyards were devastated by the bug, leading to massive vine deaths and eventual replanting. Grafting is done in every wine-producing country of the world except for Argentina, the Canary Islands and Chile, which are the only ones that have not yet been exposed to the insect.[19]

In the context of wine production, terroir is a concept that encompasses the varieties of grapes used, elevation and shape of the vineyard, type and chemistry of soil, climate and seasonal conditions, and the local yeast cultures. The range of possibilities here can result in great differences between wines, influencing the fermentation, finishing, and aging processes as well. Many wineries use growing and production methods that preserve or accentuate the aroma and taste influences of their unique terroir.[20] However, flavor differences are not desirable for producers of mass-market table wine or other cheaper wines, where consistency is more important. Such producers will try to minimize differences in sources of grapes by using production techniques such as micro-oxygenation, tannin filtration, cross-flow filtration, thin film evaporation, and spinning cones.[21]

Classification

Regulations govern the classification and sale of wine in many regions of the world. European wines tend to be classified by region (e.g. Bordeaux and Chianti), while non-European wines are most often classified by grape (e.g. Pinot Noir and Merlot). More and more, however, market recognition of particular regions is leading to their increased prominence on non-European wine labels. Examples of non-European recognized locales include Napa Valley in California, Willamette Valley in Oregon, Barossa Valley and Hunter Valley in Australia, Central Valley in Chile, Marlborough in New Zealand and Niagara Peninsula in Canada.

Some blended wine names are marketing terms, and the use of these names is governed by trademark law rather than by specific wine laws. For example, Meritage (sounds like "heritage") is generally a Bordeaux-style blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, and may also include Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, and Malbec. Commercial use of the term "Meritage" is allowed only via licensing agreements with an organization called the "Meritage Association".

European classifications

France has an appellation system based on the concept of terroir, with classifications which range from Vin de Table ("table wine") at the bottom, through Vin de Pays and Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (VDQS) up to Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC).[22][23] Portugal has something similar and, in fact, pioneered this technique back in 1756 with a royal charter which created the "Demarcated Douro Region" and regulated wine production and trade.[24] Germany did likewise in 2002, although their system has not yet achieved the authority of those of the other countries'.[25][26] Spain and Italy have classifications which are based on a dual system of region of origin and quality of product.[27][28]

Beyond Europe

New World wine—wines from outside of the traditional wine growing regions of Europe tend to be classified by grape rather than by terroir or region of origin, although there have been non-official attempts to classify them by quality.[29][30]

Vintages

A "vintage wine" is one made from grapes that were all or mostly grown in a particular year, and labeled as such. Most countries allow a vintage wine to include a portion that is not from the labeled vintage. Variations in a wine's character from year to year can include subtle differences in color, palate, nose, body and development. High-quality red table wines can improve in flavor with age if properly stored.[1] Consequently, it is not uncommon for wine enthusiasts and traders to save bottles of an especially good vintage wine for future consumption.

In the United States, for a wine to be vintage dated and labeled with a country of origin or American Viticultural Area (AVA) (such as "Sonoma Valley"), it must contain at least 95% of its volume from grapes harvested in that year.[31] If a wine is not labeled with a country of origin or AVA the percentage requirement is lowered to 85%.[31]

Vintage wines are generally bottled in a single batch so that each bottle will have a similar taste. Climate can have a big impact on the character of a wine to the extent that different vintages from the same vineyard can vary dramatically in flavor and quality.[32] Thus, vintage wines are produced to be individually characteristic of the vintage and to serve as the flagship wines of the producer. Superior vintages, from reputable producers and regions, will often fetch much higher prices than their average vintages. Some vintage wines, like Brunellos, are only made in better-than-average years.

Non-vintage wines can be blended from more than one vintage for consistency, a process which allows wine makers to keep a reliable market image and maintain sales even in bad years.[33][34] One recent study suggests that for normal drinkers, vintage year may not be as significant to perceived wine quality as currently thought, although wine connoisseurs continue to place great importance on it.[35]

Tasting

Wine tasting is the sensory examination and evaluation of wine. Wines are made up of chemical compounds which are similar or identical to those in fruits, vegetables, and spices. The sweetness of wine is determined by the amount of residual sugar in the wine after fermentation, relative to the acidity present in the wine. Dry wine, for example, has only a small amount of residual sugar. Inexperienced wine drinkers often tend to mistake the taste of ripe fruit for sweetness when, in fact, the wine in question is very dry.

Individual flavors may also be detected, due to the complex mix of organic molecules such as esters and terpenes that grape juice and wine can contain. Tasters often can distinguish between flavors characteristic of a specific grape (e.g., Chianti and sour cherry) and flavors that result from other factors in wine making, either intentional or not. The most typical intentional flavor elements in wine are those that are imparted by aging in oak casks; chocolate, vanilla, or coffee almost always come from the oak and not the grape itself.[36]

Banana flavors (isoamyl acetate) are the product of yeast metabolism, as are spoilage aromas such as sweaty, barnyard, band-aid (4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol),[37] and rotten egg (hydrogen sulfide).[38] Some varietals can also have a mineral flavor, because some salts are soluble in water (like limestone), and are absorbed by the wine.

Wine aroma comes from volatile compounds in the wine that are released into the air.[39] Vaporization of these compounds can be sped up by twirling the wine glass or serving the wine at room temperature. For red wines that are already highly aromatic, like Chinon and Beaujolais, many people prefer them chilled.[40]

Collecting

At the highest end, rare, super-premium wines are the most expensive of all food, and outstanding vintages from the best vineyards may sell for thousands of dollars per bottle, though the broader term fine wine covers bottles typically retailing at over about $US 30-50.[41] "Investment wines" are considered by some to be Veblen goods—that is, goods for which demand increases instead of decreases as its price rises. The most common wines purchased for investment include those from Bordeaux, Burgundy, cult wines from Europe and elsewhere, and Vintage port. Characteristics of highly collectible wines include:

- A proven track record of holding well over time

- A drinking window plateau (i.e., the period for maturity and approachability) that is many years long

- A consensus amongst experts as to the quality of the wines

- Rigorous production methods at every stage, including grape selection and appropriate barrel-ageing

Investment in fine wine has attracted fraudsters who prey on their victims' ignorance of this sector of the wine market. Wine fraudsters often work by charging excessively high prices for off-vintage or lower-status wines from famous wine regions, while claiming that they are offering a sound investment unaffected by economic cycles. Like any investment, proper research is essential before investing.

Production

| Rank | Country (with link to wine article) |

Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,349,333 | |

| 2 | 4,711,665 | |

| 3 | 3,643,666 | |

| 4 | 2,232,000 | |

| 5 | 1,539,600 | |

| 6 | 1,410,483 | |

| 7 | 1,400,000 | |

| 8 | 1,012,980 | |

| 9 | 977,087 | |

| 10 | 891,600 |

| Rank | Country (with link to wine article) |

Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,050,000 | |

| 2 | 4,711,600 | |

| 3 | 3,645,000 | |

| 4 | 2,300,000 | |

| 5 | 1,550,000 | |

| 6 | 1,450,000 | |

| 7 | 1,050,000 | |

| 8 | 961,972 | |

| 9 | 891,600 | |

| 10 | 827,746 |

Wine grapes grow almost exclusively between thirty and fifty degrees north or south of the equator. The world's southernmost vineyards are in the Central Otago region of New Zealand's South Island near the 45th parallel,[43] and the northernmost are in Flen, Sweden, just north of the 59th parallel.[44]

Exporting countries

* Unofficial figure. ** May include official, semi-official or estimated data. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The UK was the world's biggest importer of wine in 2007.[46]

Uses

Wine is a popular and important beverage that accompanies and enhances a wide range of European and Mediterranean-style cuisines, from the simple and traditional to the most sophisticated and complex. Wine is important in cuisine not just for its value as a beverage, but as a flavor agent, primarily in stocks and braising, since its acidity lends balance to rich savory or sweet dishes. Red, white, and sparkling wines are the most popular, and are known as light wines because they are only 10–14% alcohol-content by volume. Apéritif and dessert wines contain 14–20% alcohol, and are sometimes fortified to make them richer and sweeter.

Some wine labels suggest opening the bottle and letting the wine "breathe" for a couple hours before serving, while others recommend drinking it immediately. Decanting—the act of pouring a wine into a special container just for breathing—is a controversial subject in wine. In addition to aeration, decanting with a filter allows one to remove bitter sediments that may have formed in the wine. Sediment is more common in older bottles but younger wines usually benefit more from aeration.[47]

During aeration, the exposure of younger wines to air often "relaxes" the flavors and makes them taste smoother and better integrated in aroma, texture, and flavor. Older wines generally fade, or lose their character and flavor intensity, with extended aeration.[48] Despite these general rules, breathing does not necessarily benefit all wines. Wine should be tasted as soon as it is opened to determine how long it should be aerated, if at all.

Religious uses

The use of wine in religious ceremonies is common to many cultures and regions. Libations often included wine, and the religious mysteries of Dionysus used wine as a sacramental entheogen to induce a mind-altering state.

Wine is an integral part of Jewish laws and traditions. The Kiddush is a blessing recited over wine or grape juice to sanctify the Shabbat or a Jewish holiday. On Pesach (Passover) during the Seder, it is a Rabbinic obligation of men and women to drink four cups of wine.[49] In the Tabernacle and in the Temple in Jerusalem, the libation of wine was part of the sacrificial service.[50] Note that this does not mean that wine is a symbol of blood, a common misconception which contributes to the myth of the blood libel. A blessing over wine said before indulging in the drink is: "Baruch atah Hashem (Adonai) elokeinu melech ha-olam, boray p’ree hagafen"—"Praised be the Eternal, Ruler of the universe, who makes the fruit of the vine."

In Christianity, wine is used in a sacred rite called the Eucharist (grape juice is often used in Protestant communion, whereas the Eucharist must be celebrated with wine), which originates in Gospel accounts of the Last Supper in which Jesus shared bread and wine with his disciples and commanded his followers to "do this in remembrance of me" (Gospel of Luke 22:19). Beliefs about the nature of the Eucharist vary among denominations; Roman Catholics, for example, hold that the bread and wine are changed into the real body and blood of Christ in a process called transubstantiation.

Wine was used in the Eucharist by all Protestant groups until an alternative arose in 1869. Methodist minister-turned-dentist Thomas Bramwell Welch applied new pasteurization techniques to stop the natural fermentation process of grape juice. Some Christians who were part of the growing temperance movement pressed for a switch from wine to grape juice, and the substitution spread quickly over much of the United States. (However, in such rites the beverage is usually still called "wine" in accordance with scriptural references.)[51] There remains an ongoing debate between some American Protestant denominations as to whether wine can and should be used for the Eucharist or allowed as a regular beverage.

The general use of wine is forbidden under Islamic law; it is only permitted for medicinal reasons. Iran used to have a thriving wine industry that disappeared after the Islamic Revolution in 1979.[52]

Health effects

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 355 kJ (85 kcal) | ||||

2.6 g | |||||

| Sugars | 0.6 g | ||||

0.0 g | |||||

0.1 g | |||||

| |||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||

| Alcohol (ethanol) | 10.6 g | ||||

10.6 g alcohol is 13%vol. 100 g wine is approximately 100 ml (3.4 fl oz.) Sugar and alcohol content can vary. | |||||

Although excessive alcohol consumption has adverse health effects, epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated that moderate consumption of alcohol and wine is statistically associated with a decrease in death due to cardiovascular events such as heart failure.[53] In the United States, a boom in red wine consumption was initiated in the 1990s by the TV show 60 Minutes, and additional news reports on the French paradox.[54] The French paradox refers to the comparatively lower incidence of coronary heart disease in France despite high levels of saturated fat in the traditional French diet. Some epidemiologists suspect that this difference is due to the higher consumption of wines by the French, but the scientific evidence for this theory is limited. The average moderate wine drinker is more likely to exercise more, to be more health conscious, and to be of a higher educational and socioeconomic class, evidence that the association between moderate wine drinking and health may be related to confounding factors.[53]

Population studies have observed a J curve association between wine consumption and the risk of heart disease. This means that heavy drinkers have an elevated risk, while moderate drinkers (at most two five-ounce servings of wine per day) have a lower risk than non-drinkers. Studies have also found that moderate consumption of other alcoholic beverages may be cardioprotective, although the association is considerably stronger for wine. Also, some studies have found increased health benefits for red wine over white wine, though other studies have found no difference. Red wine contains more polyphenols than white wine, and these are thought to be particularly protective against cardiovascular disease.[53]

A chemical in red wine called resveratrol has been shown to have both cardioprotective and chemoprotective effects in animal studies.[55] Low doses of resveratrol in the diet of middle-aged mice has a widespread influence on the genetic levers of aging and may confer special protection on the heart. Specifically, low doses of resveratrol mimic the effects of what is known as caloric restriction - diets with 20-30 percent fewer calories than a typical diet.[56] Resveratrol is produced naturally by grape skins in response to fungal infection, including exposure to yeast during fermentation. As white wine has minimal contact with grape skins during this process, it generally contains lower levels of the chemical.[57] Other beneficial compounds in wine include other polyphenols, antioxidants, and flavonoids.[58]

Red wines from the south of France and from Sardinia in Italy have been found to have the highest levels of procyanidins, which are compounds in grape seeds suspected to be responsible for red wine's heart benefits. Red wines from these areas have between two and four times as much procyanidins as other red wines. Procyanidins suppress the synthesis of a peptide called endothelin-1 that constricts blood vessels.[59]

A 2007 study found that both red and white wines are effective anti-bacterial agents against strains of Streptococcus.[60] Also, a report in the October 2008 issue of Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, posits that moderate consumption of red wine may decrease the risk of lung cancer in men.[61]

While evidence from laboratory and epidemiological (observational) studies suggest a cardioprotective effect, no controlled studies have been completed on the effect of alcoholic drinks on the risk of developing heart disease or stroke. Excessive consumption of alcohol can cause cirrhosis of the liver and alcoholism;[62] the American Heart Association cautions people to "consult your doctor on the benefits and risks of consuming alcohol in moderation."[63]

Wine's effect on the brain is also under study. One study concluded that wine made from the Cabernet Sauvignon grape reduces the risk of Alzheimer's Disease.[64][65] Another study concluded that among alcoholics, wine damages the hippocampus to a greater degree than other alcoholic beverages.[66]

Sulphites are present in all wines and are formed as a natural product of the fermentation process, and many wine producers add sulfur dioxide in order to help preserve wine. Sulfur dioxide is also added to foods such as dried apricots and orange juice. The level of added sulfites varies, and some wines have been marketed with low sulfite content.[67] Sulphites in wine can cause some people, particularly those with asthma, to have adverse reactions.

Professor Valerie Beral from the University of Oxford and lead author of the The Million Women Study asserts that the positive health effects of red wine are "an absolute myth." Professor Roger Corder, author of The Red Wine Diet, counters that two small glasses of a very tannic, procyanadin rich wine would confer a benefit, although "most supermarket wines are low procyanadin and high alcohol."[68]

Packaging

Most wines are sold in glass bottles and are sealed using corks. An increasing number of wine producers have been using alternative closures such as screwcaps or synthetic plastic "corks". In addition to being less expensive, alternative closures prevent cork taint, although they have been blamed for other problems such as excessive reduction.

Some wines are packaged in heavy plastic bags within cardboard boxes, and are called box wines, or cask wine. These wines are typically accessed via a tap on the side of the box. Box wine can maintain an acceptable degree of freshness for up to a month after opening, while bottled wine will more rapidly oxidize, and is considerably degraded within a few days.

Environmental considerations of wine packaging reveal benefits and drawbacks of both bottled and box wines. Glass used to make bottles has a decent environmental reputation, as it is completely recyclable, whereas plastics as used in box wines are typically considered to be much less environmentally friendly. However, wine bottle manufacturers have been cited for Clean Air Act violations. A New York Times editorial puported that box wine, being lighter in package weight, has a reduced carbon footprint from its distribution. Boxed wine plastics, even though possibly recyclable, can be more labor-intensive (and therefore expensive) to process than glass bottles. And while a wine box is recyclable, its plastic wine bladder most likely is not.[69]

Storage

Wine cellars, or wine rooms if they are above-ground, are places designed specifically for the storage and aging of wine. In an active wine cellar, temperature and humidity are maintained by a climate control system. Passive wine cellars are not climate-controlled, and so must be carefully located. Wine is a natural, perishable food product; when exposed to heat, light, vibration or fluctuations in temperature and humidity, all types of wine, including red, white, sparkling, and fortified, can spoil. When properly stored, wines can maintain their quality and in some cases improve in aroma, flavor, and complexity as they age. Some wine experts contend that the optimal temperature for aging wine is 55 °F (13 °C).[70] Wine refrigerators offer an alternative to wine cellars. They are available in capacities ranging from small 16-bottle units to furniture pieces that can contain 400 bottles.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Cooper | Craftsman of wooden barrels and casks. A cooperage is a company that produces such casks. |

| Garagiste | An amateur wine maker, or a derogatory term used for small scale operations of recent inception, usually without pedigree and located in Bordeaux. |

| Négociant | A wine merchant, most specifically those who assemble the produce of smaller growers and winemakers and sells them under their own name. |

| Oenologist | Wine scientist or wine chemist; a student of oenology. A winemaker may be trained as oenologist, but often hires a consultant instead. |

| Sommelier | A restaurant specialist in charge of assembling the wine list, educating the staff about wine, and assisting customers with their wine selections. |

| Vintner, Winemaker | A wine producer; a person who makes wine. |

| Viticulturist | A person who specializes in the science of grapevines. Can also be someone who manages vineyard pruning, irrigation, and pest control. |

Film and television

- Falcon Crest, USA 1981–1990: A popular CBS primetime soap opera about the fictional Falcon Crest winery and the family who owned it, set in a fictional "Tuscany Valley" in California. A wine named "Falcon Crest" even went on the market.

- A Walk in the Clouds 1995. A love story set in a Mexican-American family's traditional vineyard showcasing different moments in the production of wine.

- Mondovino, USA/France 2004. A documentary film directed by American film maker Jonathan Nossiter, exploring the impact of globalization on various wine-producing regions.

- Sideways, 2004. A comedy/drama film, directed by Alexander Payne, with the tagline: "In search of wine. In search of women. In search of themselves." Wine, particularly Pinot Noir, plays a central role. The film caused the Pinot Noir sales to rise in the USA, known as 'the Sideway's Effect'.[71]

- A Good Year, 2006. Ridley Scott directs Russell Crowe in an adaptation of Peter Mayle's novel.

- Oz and James's Big Wine Adventure, UK 2006–7. "Wine ponce" Oz Clarke tries to teach motor head James May about wine. The first series saw them traveling through the wine regions of France, and the second series saw them drive throughout California.

- Crush, USA 2007. Produced and directed by Bret Lyman, this is a documentary short that covers the 2006 grape harvest and crush in California's wine country. It also features winemaker Richard Bruno.

- Bottle Shock (USA 2008) tells a story centered around the Paris Wine Tasting of 1976, in addition to portraying the birth of the Napa wine industry.

- The Judgment of Paris (in production, USA 2010) is to based on journalist George M. Taber's account of the same Paris Wine Tasting of 1976 that was fictionalized in Bottle Shock.

See also

References

- ^ a b "wine". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Johnson, H. (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon & Schuster. pp. 11–6. ISBN 0671791826.

- ^ "Introduction to Wine". 2basnob.com.

- ^ Allen, Fal. "Barley Wine". Anderson Valley Brewing Company. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ George, Rosemary (1991). The Simon & Schuster Pocket Wine Label Decoder. Fireside. ISBN 978-0671728977.

- ^ a b Keys, David (2003-12-28). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ a b Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "wine". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Whiter, Walter (1800). "Wine". Etymologicon Magnum, Or Universal Etymological Dictionary, on a New Plan. Francis Hodson. p. 145. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ a b Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ a b Viegas, Jennifer (2007-03-16). "Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece". Discovery News. Discovery Communications. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Bureau Report. "Mashed grapes find could re-write history of wine". Zee News. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon and Schuster. p. 32.

- ^ Rong, Xu Gan. "Wine Production in China". Grandiose Survey of Chinese Alcoholic Drinks and Beverages. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Phillips, Rod (2002-11-12). A Short History of Wine. Harper Perennial. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0060937379.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Great Resource". 1. Episode 9. 2006-11-03.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|episodelink=(help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources". Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Robinson, Jancis (2006-04-28). Jancis Robinson's Wine Course: A Guide to the World of Wine. Abbeville Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0789208835.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Johnson, Hugh (2001-09-13). The World Atlas of Wine. Mitchell Beazley. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1840003321.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Citriglia, Matthew (2006-05-14). "High Alcohol is a Wine Fault... Not a Badge of Honor". GeekSpeak, LLC. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "Wine classification". French Wine Guide. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ Goode, Jamie. "Terroir revisited: towards a working definition". Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ "The Spirit of the Commemorations". Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "About German Wine". German wine society. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ "German Wine Guide: Wine Laws and Classifications". The Winedoctor. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ "Land of wines". Wines from Spain. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ "Wine Classification — by Region or by Wine Type?". Wine Intro. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ Chlebnikowski, Simon. "Towards an Australian Wine Classification". Nicks Wine Merchants. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Langton's Australian Wine Classification IV". 2007-07-27. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ a b Title 27 of the United States Code, Code of Federal Regulations §4.27

- ^ Breton, Félicien. "Wine vintages, vintage charts". French Scout. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Platman, Clive (2002-10-02). "Wine: Lovely bubbly". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (2006). "Change to Vintage Date Requirements (2005R-212P)". Federal Register. 71 (84): 25748. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Weil, Roman L. (2001-05-25). "Parker v. Prial: The Death of the Vintage Chart" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Breton, Félicien. "Types of wine". French Scout. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ ETS Laboratories (2001-03-15). "Brettanomyces Monitoring by Analysis of 4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ ETS Laboratories (2002-05-15). "Sulfides in Wine". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Gómez-Míguez, M. José (2007). "Assessment of colour and aroma in white wines vinifications: Effects of grape maturity and soil type". Journal of Food Engineering. 79 (3): 758–764. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.02.038. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson, Hugh (2001-09-13). The World Atlas of Wine. Mitchell Beazley. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1840003321.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ For example, Berry Brothers & Rudd, one of the world's largest dealers, start "Fine wine" prices at about £25 - in March 2009 with a wine from Au Bon Climat website "Fine wine offers".

- ^ a b FAO production statistics

- ^ Courtney, Sue (2005-04-16). "New Zealand Wine Regions - Central Otago". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Wine History". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ a b FAO

- ^ "UK tops world wine imports table". BBC. 2009-01-14.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh (2001-09-13). The World Atlas of Wine. Mitchell Beazley. p. 46. ISBN 978-1840003321.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fruity character and breathing times". New Straits Times. 2005-09-18. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rich, Tracey R. "Pesach: Passover". Judaism 101.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (2000). The Halakhah: An Encyclopaedia of the Law of Judaism. Boston, Massachusetts: BRILL. p. 82. ISBN 9004116176.

- ^ "Almost Like Wine". Time Magazine. 1956-09-03. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Tait, Robert (2005-10-12). "End of the vine". Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ a b c Lindberg, Matthew L. (2008). "Alcohol, wine, and cardiovascular health". Clinical Cardiology. 31 (8): 347–51. doi:10.1002/clc.20263. PMID 18727003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dodd, Tim H. (1994). "The impact of media stories concerning health issues on food product sales: management planning and responses". Journal of Consumer Marketing. 11 (2): 17–24. doi:10.1108/07363769410058894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Olas, Beata (2002). "Effect of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound, on platelet activation induced by endotoxin or thrombin". Thrombosis Research. 107 (3): 141–145. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(02)00273-6. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barger, Jamie L. (2008). "A Low Dose of Dietary Resveratrol Partially Mimics Caloric Restriction and Retards Aging Parameters in Mice". PLoS ONE. 3 (6): e2264. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002264. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Frémont, Lucie (2000). "Biological effects of resveratrol". Life Sciences. 66 (8): 663–673. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00410-5. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ de Lange, D.W. (2007). "From red wine to polyphenols and back: A journey through the history of the French Paradox". Thrombosis Research. 119 (4): 403–406. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2006.06.001. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Corder, R. "Oenology: Red wine procyanidins and vascular health". Nature. 444 (566): 566. doi:10.1038/444566a.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Daglia, M. (2007). "Antibacterial Activity of Red and White Wine against Oral Streptococci". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (13): 5038. doi:10.1021/jf070352q.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Red Wine May Lower Lung Cancer Risk Newswise, Retrieved on October 7, 2008.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "General Information on Alcohol Use and Health". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ American Heart Association. "Alcohol, Wine and Cardiovascular Disease". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Wang, Jun (2006). "Moderate Consumption of Cabernet Sauvignon Attenuates β-amyloid Neuropathology in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease". FASEB. 20: 2313–2320. doi:10.1096/fj.06-6281com. PMID 17077308. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Cabernet Sauvignon Red Wine Reduces The Risk Of Alzheimer's Disease". ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily LLC. 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Allen, Vanessa (2008-03-17). "Wine is worse for brain than beer, scientists reveal in blow for women drinkers". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Ageing and Storing Wines, Wines of Canada, Retrieved 5 June 2007

- ^ "Alcohol: Is it really good for you?". BBC News. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ Muzaurieta, Annie Bell, thedailygreen.com (October 1, 2008). Holy Hangover! Wine Bottles Cause Air Pollution

- ^ fineliving.com Storing Wine

- ^ Abbott, John. Decanter.com (November 3, 2008). 'Sideways effect' confirmed

Further reading

- Foulkes, Christopher (2001). Larousse Encyclopedia of Wine. Larousse. ISBN 2-03-585013-4.

- Johnson, Hugh (2003). Hugh Johnson's Wine Companion (5th ed.). Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 978-1840007046.

- McCarthy, Ed (2006). Wine for Dummies. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-470-04579-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman. ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- Pigott, Stuart (2004). Planet Wine: A Grape by Grape Visual Guide to the Contemporary Wine World. Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 978-1840007763.

- Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Zraly, Kevin (2006). Windows on the World Complete Wine Course. Sterling. ISBN 1-4027-3928-1.

External links

- The Guardian & Observer Guide to Wine

- The wine anorak by wine writer Jamie Goode