John Major

Sir John Major | |

|---|---|

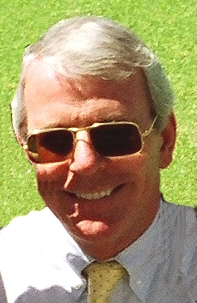

John Major in 1996 | |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 28 November 1990 – 2 May 1997 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Deputy | Michael Heseltine |

| Preceded by | Margaret Thatcher |

| Succeeded by | Tony Blair |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 2 May 1997 – 19 June 1997 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | Tony Blair |

| Preceded by | Tony Blair |

| Succeeded by | William Hague |

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |

| In office 28 November 1990 – 19 June 1997 | |

| Preceded by | Margaret Thatcher |

| Succeeded by | William Hague |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 26 October 1989 – 28 November 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Nigel Lawson |

| Succeeded by | Norman Lamont |

| Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs | |

| In office 24 July 1989 – 26 October 1989 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Sir Geoffrey Howe |

| Succeeded by | Douglas Hurd |

| Chief Secretary to the Treasury | |

| In office 13 June 1987 – 24 July 1989 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | John MacGregor |

| Succeeded by | Norman Lamont |

| Member of Parliament for Huntingdon Huntingdonshire (1979–1983) | |

| In office 3 May 1979 – 7 June 2001 | |

| Preceded by | David Renton |

| Succeeded by | Jonathan Djanogly |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 March 1943 Carshalton, Surrey, UK |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | Norma Johnson (m. 1970–present) |

| Relations | Tom Major-Ball (father, deceased) Terry Major-Ball (brother, deceased) |

| Children | James Elizabeth |

| Profession | Banker |

| Signature |  |

Sir John Major, KG, CH, PC, ACIB (born 29 March 1943) is a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1990 to 1997. Major was Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997 and held the posts of Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Cabinet of Margaret Thatcher. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon from 1979 to 2001.

Although Major proved "a great disappointment to Thatcher," he was her preferred choice as successor as she expected to "continue in control of the country as a backseat driver".[1] Early in his term, Major presided over British participation in the Gulf War in March 1991 and claimed to have negotiated "Game, Set and Match for Britain"[2] at the Maastricht Treaty in December 1991. Despite the British economy then being in recession, he led the Conservatives to a fourth consecutive election victory, winning the most votes in British electoral history (14 million) in the 1992 general election, albeit with a much reduced majority in the House of Commons. He is to date, the last Conservative leader to win an outright majority in a general election.

Major's premiership saw the world go through a period of political and military transition after the end of the Cold War. This included the rise of the European Union, an issue which was already a source of friction within the Conservative Party owing to its importance in the decline and fall of Margaret Thatcher. Major and his government were responsible for the United Kingdom's exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) after Black Wednesday on 16 September 1992, after which his government never gained a lead in the opinion polls.

Despite successes such as the revival of economic growth and the beginnings of the Northern Ireland Peace Process, by the mid-1990s the Conservatives were embroiled in ongoing "sleaze" scandals involving various MPs and even Cabinet Ministers. Criticism of Major's leadership reached such a pitch that he chose to resign, and be re-elected, as party leader in June 1995. By this time the "New" Labour Party was seen as a reformed and fresh alternative under the leadership of Tony Blair, and after eighteen years in office the Conservatives lost the 1997 general election in one of the worst electoral defeats since the Great Reform Act of 1832.

After the defeat, Major resigned as the leader of the party, and was succeeded by William Hague. He has since retired from active politics, leaving the House of Commons at the 2001 general election.

Early life

Major was born at the St. Helier Hospital in Sutton, Surrey, the son of Gwen Major and former Music Hall performer Tom Major-Ball (né Abraham Thomas Ball), who was 64 years old when John was born. He was christened as John Roy Major, but only "John" is shown on his birth certificate. He used his middle name Roy until the early 1980s.[3] He attended primary school at Cheam Common. From 1954, he attended Rutlish Grammar School in Merton. In 1955, with his father's garden ornaments business in decline, the family moved to Brixton. The following year, Major watched his first debate in the House of Commons – Harold Macmillan's only budget – and has attributed his political ambitions to that event, and to a chance meeting with former Prime Minister Clement Attlee on the King's Road.[3][4]

Major left school at age 16 in 1959, with three O-levels: History, English Language, and English Literature. He later gained three more O-levels by correspondence course, in the British Constitution, mathematics and economics. His first job was as a clerk in the insurance brokerage firm Pratt & Sons in 1959. Disliking this job, he quit, and for a time he helped with his father's garden ornaments business along with his brother, Terry Major-Ball. Major joined the Young Conservatives in Brixton at this time.[5] Major was 19 years old when in 1962 his father died at the age of 83. His mother died eight years later at the age of 65.

After Major became prime minister, it was misreported that he had failed to get a job as a bus conductor because of failing a maths test, when in fact he passed all of the tests, but had been passed over for the job to another candidate owing to his height.[6][7]

After a period of unemployment, Major started working at the London Electricity Board (where his successor as the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, also worked when he was young) in 1963, and he decided to undertake a correspondence course in banking.[8] Major took up a post as an executive at the Standard Chartered Bank in May 1965, and he rose quickly through the ranks. He was sent to work in Jos, Nigeria by the bank in 1967, and he nearly died in a car accident there.[9][10]

Early political career

Major was interested in politics from an early age. Encouraged by fellow Conservative Derek Stone, he started giving speeches on a soap-box in Brixton market. He stood as a candidate for Lambeth London Borough Council at the age of 21 in 1964, and was elected in the Conservative landslide in 1968. While on the council he was Chairman of the Housing Committee, being responsible for the building of several council housing estates. He lost his seat in May 1971.[11]

Major was an active Young Conservative and according to his biographer Anthony Seldon brought "youthful exuberance" to the Tories in Brixton, but was often in trouble with the professional agent Marion Standing.[11] Also according to Seldon, the formative political influence on Major was Jean Kierans, a divorcée 13 years his elder, who became his political mentor and his lover, too. Seldon writes "She... made Major smarten his appearance, groomed him politically, and made him more ambitious and worldly." Their relationship lasted from 1963 to sometime after 1968.

Major stood for election to Parliament in St Pancras North in both general elections in 1974, but was unsuccessful. In November 1976, Major was selected by the Huntingdonshire Conservatives as its candidate, winning in the 1979 general election.[11] Following boundary changes, Major became Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon in 1983 and retained the seat in the 1987, 1992 and 1997 general elections. His majority in 1992 was 36,230 votes, the largest in British electoral history. He stood down at the 2001 general election.

In the Cabinet

He was appointed as a Parliamentary Private Secretary from 1981, and an assistant whip from 1983. He was made Under-Secretary of State for Social Security in 1985, before being promoted to become Minister of State in the same department in 1986, first attracting national media attention over cold weather payments to the elderly in January 1987, when Britain was in the depths of a severe winter.[12][13]

Major was promoted to the Cabinet as Chief Secretary to the Treasury in 1987, following the general election, and in a surprise re-shuffle in July 1989, a relatively inexperienced Major was appointed Foreign Secretary, succeeding Sir Geoffrey Howe. He would only remain three months in that post before becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer after Nigel Lawson's surprise resignation in October 1989. Major presented only one Budget, the first one to be televised live, in early 1990. He publicised it as a budget for savings and announced the Tax-Exempt Special Savings Account (TESSA), arguing that measures were required to address the marked fall in the household savings ratio that had been apparent during the previous financial year. In June 1990, Major suggested that the proposed Single European Currency should be a "hard ecu", competing for use against existing national currencies; this idea was not in the end adopted. In October 1990, Major and Douglas Hurd, Major's successor as Foreign Secretary, finally persuaded Thatcher to allow Britain to join the Exchange Rate Mechanism, a move which she had resisted for some years, and which had been a cause of her quarrels with Howe and Lawson.

When Michael Heseltine challenged Margaret Thatcher's leadership of the Conservative Party in November 1990, Major and Douglas Hurd were her proposer and seconder on her nomination papers. Major entered the contest alongside Douglas Hurd on 22 November after Thatcher abandoned her plans to contest the second ballot, ending her 11 years as prime minister and 15 years as party leader. Major was at home in Huntingdon recovering from a wisdom tooth operation at this time. Thatcher's nomination papers for the second ballot were sent to him by car for him to sign – it later emerged that he had signed both Thatcher's papers and a set of papers for his own candidacy in case she withdrew.

Though he fell two votes short of the required winning margin of 187 in the second ballot, the result was sufficient to secure immediate concessions from his rivals. He was named Leader of the Conservative Party on 27 November 1990, and was summoned to Buckingham Palace and appointed Prime Minister the following day.

Prime Minister

The Persian Gulf War

Major was Prime Minister during the first Gulf War of 1991, and played a key role in persuading US President George H. W. Bush to support no-fly zones. During the war Major and his Cabinet survived an IRA assassination attempt by mortar attack.

Soapbox election

The economy had been sliding into recession during the final months of Thatcher's spell in power, and the recession deepened during 1991 and continued until the end of 1992.

The Tories had slipped behind Labour in the opinion polls during 1989 and the gap widened during 1990, but within two months of Major taking over as prime minister the Tories had returned to the top of the opinion polls, briefly enjoying a comfortable lead after the Gulf War. Polls also showed that Major was the most popular prime minister in Britain since Harold Macmillan some 30 years previously.[14]

Labour Party and opposition leader Neil Kinnock made endless calls for a general election throughout 1991, but Major held out and decided not to call the election until he finally set an election date of 9 April 1992. During this time, the Tories and Labour had exchanged places at the top of the opinion polls on numerous occasions,[15] and by the time of the election most opinion polls were showing a slim Labour lead, which most observers predicted would translate into a hung parliament or a narrow Labour victory at the election.

Major took his campaign onto the streets, delivering many addresses from an upturned soapbox as in his Lambeth days. This approach stood in contrast to the Labour Party's seemingly slicker campaign and it chimed with the electorate, along with hard-hitting negative campaign advertising focusing on the issue of Labour's approach to taxation. Major won in excess of 14 million votes, the highest popular vote recorded by a British political party in a general election. However, this translated into a reduced majority of 21 seats, enough to form a practicable but small majority. The Tory election win led to the resignation of Neil Kinnock as Labour leader and the election of John Smith as his successor.

Black Wednesday

The Conservative majority proved too small for effective control over his backbenchers, particularly after the United Kingdom's forced exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) on "Black Wednesday", 16 September 1992, just five months into the new parliament, when billions of pounds were spent in a futile attempt to defend the currency's value. After the release of Black Wednesday government documents,[16] it became apparent that Major came very close to stepping down from office at this point, having even prepared an unsent letter of resignation addressed to the Queen.[17] Major continued to defend Britain's membership of the ERM, stating that "The ERM was the medicine to cure the ailment, but it was not the ailment".[18]

Major kept his economic team unchanged for seven months after Black Wednesday before he replaced Norman Lamont with Kenneth Clarke as Chancellor of the Exchequer, after months of press criticism of Lamont and disastrous defeat at a by-election in Newbury. Such a delay, on top of the crisis, was exploited by Major's critics as proof of the indecisiveness that was to undermine his authority through the rest of his premiership. Britain's departure from the ERM led to a fall in the opinion poll ratings for the Conservative Party,[19] which despite the improvement in the economic position, did not fully recover whilst John Major was Prime Minister.

Within a year of Major's general election win, general public and media opinion of him had plummeted, with Black Wednesday, mine closures, the Maastricht dispute and mass unemployment being cited as four key areas of dissatisfaction with the prime minister. The newspapers which traditionally supported the Conservatives and had championed Major at the election were now being critical of him on an almost daily basis.[20]

The UK's forced withdrawal from the ERM was succeeded by a partial economic recovery with a new policy of flexible exchange rates, allowing lower interest rates and devaluation – increased demand for UK goods in export markets. The recession that had started just before Major came to office was declared over in April 1993, when the economy grew by 0.2%. Unemployment started to fall; by the start of 1993 it had reached almost 3,000,000, but by early 1997 it stood at 1,700,000.[21][22]

Political infighting over Europe

On becoming Prime Minister Major had promised to keep Britain "at the very heart of Europe", and claimed to have won "game, set and match for Britain" – by negotiating the social chapter and single currency opt-outs from the Maastricht Treaty, and by ensuring that there was no overt mention of a "Federal" Europe and that foreign and defence policy were kept as matters of inter-governmental cooperation, in separate "pillars" from the supranational European Union. By 2010 some of these concessions, but not Britain's non-membership of the Single Currency, had been overtaken by subsequent events.

However, even these moves towards greater European integration met with vehement opposition from the Eurosceptic wing of the party and the Cabinet as the Government attempted to ratify the Maastricht Treaty in the first half of 1993. Although the Labour opposition supported the treaty, they were prepared to tactically oppose certain provisions in order to weaken the government. This opposition included passing an amendment that required a vote on the social chapter aspects of the treaty before it could be ratified. Several Conservative MPs, known as the Maastricht Rebels, voted against the treaty, and the Government was defeated. Major called another vote on the following day, 23 July 1993, which he declared a vote of confidence. He won by 40 votes, but the damage had been done to his authority in parliament.

Later that day, Major gave an interview to ITN's Michael Brunson. During an unguarded moment when Major thought that the microphones had been switched off, Brunson asked why he did not sack the ministers who were conspiring against him. He replied: "Just think it through from my perspective. You are the prime minister, with a majority of 18... where do you think most of the poison is coming from? From the dispossessed and the never-possessed. Do we want three more of the bastards out there? What's Lyndon B. Johnson's maxim?"[23] Major later said that he had picked the number three from the air and that he was referring to "former ministers who had left the government and begun to create havoc with their anti-European activities",[24] but many journalists suggested that the three were Peter Lilley, Michael Portillo and Michael Howard, three of the more prominent "Eurosceptics" within his Cabinet.[25] Throughout the rest of Major's premiership the exact identity of the three was blurred, with John Redwood's name frequently appearing in a list along with two of the others. The tape of this conversation was leaked to the Daily Mirror and widely reported, embarrassing Major.

Arguments continued over Europe. Early in 1994 Major vetoed the Belgian politician Jean-Luc Dehaene as President of the European Commission (in succession to Jacques Delors) for being excessively federalist, only to find that he had to accept a Luxembourg politician of similar views, Jacques Santer, instead. Around this time Major – who in an unfortunate phrase denounced the Labour Leader John Smith as "Monsieur Oui, the poodle of Brussels" – tried to demand an increase in the Qualified Majority needed for voting in the newly-enlarged European Union (i.e. making it easier for Britain, in alliance with other countries, to block federalist measures). After Major had to back down on this issue Tony Marlow called openly in the House of Commons for his resignation. In 1996 European governments banned British beef over claims that it was infected with "Mad Cow Disease" – the British government withheld cooperation with the EU over the issue, but did not succeed in getting the ban lifted.

For the rest of Major's premiership the main argument was over whether Britain would join the planned European Single Currency. Some leading Conservatives (e.g. Chancellor Ken Clarke) favoured joining and insisted that Britain retain a completely free choice, whilst increasing numbers of others expressed their reluctance to join. By this time billionaire Sir James Goldsmith had set up his own Referendum Party, siphoning off some Conservative support, and at the 1997 General Election many Conservative candidates were openly expressing reluctance to join.

"Sleaze"

At the 1993 Conservative Party Conference, Major began the "Back to Basics" campaign, which he intended to be about the economy, education, policing, and other such issues, but it was interpreted by many (including Conservative cabinet ministers) as an attempt to revert to the moral and family values that the Conservative Party were often associated with. "Back to Basics", however, became synonymous with scandal, often exposed in lurid and embarrassing detail by tabloid newspapers such as The Sun. In 1992 David Mellor, a cabinet minister, had been exposed as having an extramarital affair, and for accepting hospitality from the daughter of a leading member of the PLO. The wife of the Earl of Caithness committed suicide amongst rumours of the Earl committing adultery. Stephen Milligan was found dead having apparently auto-asphyxiated whilst performing a solitary sex act (his Eastleigh seat was lost in what was to be an ongoing stream of hefty by-election defeats). David Ashby was 'outed' by his wife after sleeping with men. A string of other Conservative MPs, including Alan Amos, Tim Yeo and Michael Brown, were involved in sexual scandals.

Other debilitating scandals included "Arms to Iraq" – the ongoing inquiry into how government ministers including Alan Clark (also involved in an unrelated scandal involving the revelation of his affair with the wife and both daughters of a South African judge) had encouraged businesses to supply arms to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, in breach of the official arms embargo, and how senior ministers had, on legal advice, attempted to withhold evidence of this official connivance when directors of Matrix Churchill were put trial for breaking the embargo.

Another scandal was "Cash for Questions", in which first Graham Riddick, and David Tredinnick accepted money to ask questions in the House of Commons in a newspaper "sting", and later Tim Smith and Neil Hamilton were found to have received money from Mohamed Al Fayed, also to ask questions in the House. Later, David Willetts resigned as Paymaster General after he was accused of rigging evidence to do with Cash for Questions.

Defence Minister Jonathan Aitken was accused by the ITV investigative journalism series World In Action and The Guardian newspaper of secretly doing deals with leading Saudi princes. He denied all accusations and promised to wield the "sword of truth" in libel proceedings which he brought against The Guardian and the producers of World In Action Granada Television. At an early stage in the trial however, it became apparent that he had lied under oath, and he was subsequently (after the Major government had fallen from power) convicted of perjury and sentenced to a term of imprisonment.

Major attempted to draw some of the sting from the financial scandals by setting up public inquiries – the Nolan Report into standards expected in public life, and the Scott Report into the Arms to Iraq Scandal.

Although Tim Smith stepped down from the House of Commons at the 1997 General Election, both Neil Hamilton and Jonathan Aitken sought re-election for their seats, and were both defeated, in Hamilton's case by the former BBC Reporter Martin Bell, who stood as an anti-sleaze candidate, both the Labour and LibDem candidates withdrawing in his favour, amidst further publicity unfavourable to the Conservatives.

Northern Ireland

Major opened talks with the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) upon taking office. When he declared to the House of Commons in November 1993 that "to sit down and talk with Mr. Adams and the Provisional IRA... would turn my stomach",[26] Sinn Féin gave the media an outline of the secret talks indeed held regularly since that February. The Downing Street Declaration was issued on 15 December 1993 by Major and Albert Reynolds, the Irish Taoiseach, with whom he had a friendly relationship: an IRA ceasefire followed in 1994. In the House of Commons Major refused to sign-up to the first draft of the "Mitchell Principles", which resulted in the ending of the ceasefire. Major paved the way for the Belfast Agreement, also known as the 'Good Friday Agreement', which was signed after he left office.

In March 1995, Major refused to answer the phone calls of United States President Bill Clinton for several days because of his anger at Clinton's decision to invite Gerry Adams to the White House for St Patrick's Day.[27]

Bosnia

Major's premiership saw the ongoing war in Bosnia. Government policy was to maintain the United Nations arms embargo which restricted the flow of weapons into the region and to oppose air strikes against Bosnian Serbs. The Government's reasoning was that an arms embargo would only create a 'level killing field' and that air strikes would endanger UN peacekeepers and the humanitarian aid effort. This policy was criticised by Thatcher and others who saw the Bosnian Muslims as the main victims of Serb aggression and compared the situation to events in the Second World War. The Clinton administration, by contrast, was committed to a policy of 'lift and strike' (lifting the arms embargo and inflicting air strikes on the Serbs) causing tensions in the 'special relationship' (Douglas Hurd and others strongly opposed this policy).

Some commentators compared the Major Government's policy to 'amoral equivalency' because it appeared to judge the Bosnian Government and the Bosnian Serbs equally culpable.[28] To some extent these critics of Major's policy were vindicated when in an article published in 2011, the then Defence Secretary Malcolm Rifkind accepted that the arms embargo was a 'serious mistake' by the UN.[29]

1995 leadership election

On 22 June 1995, tired of continual threats of leadership challenges that never arose, Major resigned as Leader of the Conservative Party and announced he would contest the resulting leadership election – he continued to serve as Prime Minister while the leadership was vacant, but would have resigned had he not been re-elected by a large enough majority. John Redwood resigned as Secretary of State for Wales to stand against him. Major won by 218 votes to Redwood's 89 (with 12 spoiled ballots, eight 'active' abstentions and two MPs abstaining), enough to win in the first round, but only three more than the target he had privately set himself.[30]

The Sun newspaper, still at this stage supporting the Conservative Party, had lost faith in Major and declared its support for Redwood in the leadership election, running the front page headline "Redwood versus Deadwood".[31]

1997 general election defeat

Major's re-election as leader of the party failed to restore his authority. Despite efforts to restore (or at least improve) the popularity of the Conservative party, Labour remained far ahead in the opinion polls as the 1997 election loomed, despite the economic boom that had followed the exit from recession four years earlier, and the swift fall in unemployment. By December 1996 the Conservatives had lost their majority in the House of Commons. Major managed to survive to the end of the Parliament, but called an election on 17 March 1997 as the five-year limit for its timing approached. Major delayed the election in the hope that a still improving economy would help the Conservatives win a greater number of seats, but it did not.

Few then were surprised when Major's Conservatives lost the 1 May 1997 general election to Tony Blair's "New Labour", although the immense scale of the defeat was not as widely predicted: in 1987 and 1992 the Conservatives had polled better than had been suggested by the opinion polls, but in 1997 this was no longer the case. In the event the Conservative party suffered the worst electoral defeat by a ruling party since the Great Reform Act of 1832. In the new parliament, Labour held 418 seats, the Conservatives 165, and the Liberal Democrats 46, giving Labour a majority of 179. Major himself was re-elected in his own constituency of Huntingdon with a majority of 18,140. However, 179 other Conservative MPs were defeated, including present and former Cabinet ministers such as Norman Lamont, Sir Malcolm Rifkind and Michael Portillo. The election defeat also meant that the Tories were left without any MPs in Scotland or Wales, failing to win a single seat outside England.

At about noon on 2 May 1997, Major officially returned his seals of office as Prime Minister to The Queen. Shortly before his resignation, he gave his final statement from 10 Downing Street, in which he said; "When the curtain falls, it is time to get off the stage".[32] Major then famously announced to the press that he intended to go with his family to The Oval to watch cricket. Following his resignation as Prime Minister, Major briefly became Leader of the Opposition, and Shadow Foreign Secretary (as Sir Malcolm Rifkind, who was Foreign Secretary prior to the election, had lost his seat), and remained in this post until the election of William Hague as leader of the Conservative Party in June 1997. His Resignation Honours were announced in August 1997.

Major retired from the House of Commons at the 2001 general election, made public on the Breakfast show with David Frost.[33]

Summary

Major's mild-mannered style and moderate political stance made him theoretically well-placed to act as a conciliatory leader of his party. However, conflict raged within the Conservative Party, particularly over the extent of Britain's integration with the European Union. Major never succeeded in reconciling the "Euro-rebels" among his MPs to his European policy, who although relatively few in number - in spite of the fact that their views were much more widely supported amongst Conservative activists and voters - wielded great influence because of his small majority, and episodes such as the Maastricht Rebellion inflicted serious political damage on him and his government. During the 1990s, the bitterness on the right wing of the Conservative Party at the manner in which Margaret Thatcher had been removed from office did not make Major's task any easier. A series of scandals among leading Tory MP's also did Major and his government no favours. His task became even more difficult after the well-received election of Tony Blair as Labour leader in July 1994.[34]

On the other hand, it was during Major's premiership that the British economy recovered from the recession of 1990–1992. John Major wrote in his auto-biography that, "During my premiership interest rates fell from 14% to 6%; unemployment was at 1.75 million when I took office, and at 1.6 million and falling upon my departure; and the government's annual borrowing rose from £0.5 billion to nearly £46 billion at its peak before falling to £1 billion".[35]

The former Labour MP Tony Banks said of Major in 1994 that "He was a fairly competent chairman of Housing on Lambeth Council. Every time he gets up now I keep thinking, 'What on earth is Councillor Major doing?' I can't believe he's here and sometimes I think he can't either."[36] Paddy Ashdown, the leader of the Liberal Democrats during Major's term of office, once described him in the House of Commons as a "decent and honourable man". Few observers doubted that he was an honest man, or that he made sincere and sometimes successful attempts to improve life in Britain and to unite his deeply divided party. He was also, however, perceived as a weak and ineffectual figure,[37] and his approval ratings for most of his time in office were low, particularly after "Black Wednesday" in September 1992. Conversely on occasions he attracted criticism for dogmatically pursuing schemes favoured by the right of his party, notably the privatisation of British Rail, and for closing down most of the coal industry in advance of privatisation.[38]

Post-Prime Ministerial career

Since leaving office Major has maintained a low profile, indulging his love of cricket as president of Surrey County Cricket Club until 2002 (and Honorary Life Vice-President since 2002)[39] and commentating on political developments in the manner of a wise elder statesman.[40] He has been a member of Carlyle Group's European Advisory Board since 1998 and was appointed Chairman of Carlyle Europe in May 2001.[41] He stood down in August 2004.

Like many postwar former prime ministers, Major turned down a peerage {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) when he retired from the House of Commons in 2001. In recent history, Sir Winston Churchill, Sir Edward Heath, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown have not been elevated to the House of Lords.

In March 2001, he gave the tribute to Colin Cowdrey (Lord Cowdrey of Tonbridge) at his memorial service in Westminster Abbey.[42] In 2005 he was elected to the Committee of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), historically the governing body of the sport, and still guardian of the laws of the game.[43] Following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997, Major was appointed a special guardian to Princes William and Harry,[44] with responsibility for legal and administrative matters.

Major/Currie affair

Major's low profile following his exit from parliament was disrupted by Edwina Currie's revelation in September 2002 that, prior to his promotion to the Cabinet, he had had a four-year extramarital affair with her.[45][46] Commentators were quick to refer to Major's previous "Back to Basics" platform to throw charges of hypocrisy and had knowledge of the affair not been kept closely guarded by Tony Newton, "it is highly unlikely that Major would have become prime minister".[47] In 1993, Major had also sued two magazines, New Statesman and Society and Scallywag, as well as their distributors, for reporting rumours of an affair with a caterer, even though at least one of the magazines had said that the rumours were false. Both considered legal action to recover their costs when the affair with Currie was revealed.[48]

In a press statement, Major said that he was "ashamed" by the affair and that his wife had forgiven him. In response, Currie said "he wasn't ashamed of it at the time and he wanted it to continue."[49]

Since 2005

In February 2005, it was reported that Major and Norman Lamont delayed the release of papers on Black Wednesday under the Freedom of Information Act.[50] Major denied doing so, saying that he had not heard of the request until the scheduled release date and had merely asked to look at the papers himself. He told BBC News that he and Lamont had been the victims of "whispering" to the press.[51] He later publicly approved the release of the papers.[52]

According to the Evening Standard, Major has become a prolific after-dinner speaker. He earns over £25,000 per engagement for his "insights and his own opinions on the expanding European Union, the future of the world in the 21st century, and also about Britain", according to his agency.[53]

In December 2006, Major led calls for an independent inquiry into Tony Blair's decision to invade Iraq, following revelations made by Carne Ross, a former British senior diplomat, that contradict Blair's case for the invasion.[54] He was touted as a possible Conservative candidate for the Mayor of London elections in 2008, but turned down an offer from Conservative leader David Cameron. A spokesperson for Major said "his political career is behind him".[55]

In 2010, Major became a key loyalist to the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, and said that he hoped for a "liberal conservative" alliance beyond 2015, and has criticised Ed Miliband and the Labour Party, for "party games" rather than helping in the national interest.[56]

He was among the guests at the Royal Wedding of Prince William, Duke of Cambridge to Catherine Middleton at Westminster Abbey on 29 April 2011. Baroness Thatcher was also invited but declined to attend due to ill health.[57]

In February 2012, Major became chairman of the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust.[58] The trust was formed as part of the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II, and is intended to support charitable organisations and projects across the Commonwealth of Nations, focusing on areas such as cures for diseases and the promotion of culture and education.[58] Later on in 2012, John Major became President of influential centre-right think tank the Bow Group.[59]

He is currently a president of the Chatham House think tank.[60]

Representation in the media

During his leadership of the Conservative Party, Major was portrayed as honest ("Honest John") but unable to rein in the philandering and bickering within his party. Major's appearance was noted in its greyness, his prodigious philtrum, and large glasses, all of which were exaggerated in caricatures. For example, in Spitting Image, Major's puppet was changed from a circus performer to that of a grey man who ate dinner with his wife in silence, occasionally saying "nice peas, dear", whilst at the same time nursing an unrequited crush on his colleague Virginia Bottomley – an invention, but an ironic one in view of his affair with Edwina Currie, which was not then a matter of public knowledge. By the end of his premiership his puppet would often be shown observing the latest fiasco and ineffectually murmuring "oh dear".

The media (particularly The Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell) used the allegation by Alastair Campbell that he had observed Major tucking his shirt into his underpants to caricature him wearing his pants outside his trousers,[61] as a pale grey echo of both Superman and Supermac, a parody of Harold Macmillan. Bell also used the humorous possibilities of the Cones Hotline, a means for the public to inform the authorities of potentially unnecessary traffic cones, which was part of the Citizen's Charter project established by John Major.

Private Eye parodied Sue Townsend's The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, age 13¾ to write The Secret Diary of John Major, age 47¾, in which Major was portrayed as a naive nincompoop (e.g. keeping lists of his enemies in a Rymans Notebook called his "Bastards Book") and featuring "my wife Norman" and "Mr Dr Mawhinney" as recurring characters. The magazine still runs one-off specials of this diary (with the age updated) on occasions when Major is in the news, such as on the breaking of the Edwina Currie story or the publication of his autobiography. The magazine also ran a series of cartoons called 101 Uses for a John Major (based on a comic book of some ten years earlier, called 101 Uses for a Dead Cat), in which Major was illustrated serving a number of bizarre purposes, such as a train-spotter's anorak.

Major's Brixton roots were used in a campaign poster during the Conservative Party's 1992 election campaign: "What does the Conservative Party offer a working class kid from Brixton? They made him Prime Minister."[62]

Major was often mocked for his nostalgic evocation of what sounded like the lost Britain of the 1950s (see Merry England).[63] For example: "Fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers".[64]

Major complained in his memoirs that these words (which drew upon a passage in the sociopolitical commentator and author George Orwell's "The Lion and the Unicorn"[65]) had been misrepresented as being more naive and romantic than he had intended, and indeed his memoirs were dismissive of the common conservative viewpoint that there was once a time of moral rectitude; Major wrote that "life has never been as simple as that".

Writing in 2011, the BBC's Home editor Mark Easton judged that "Majorism" had made little lasting impact.[66] However Peter Oborne, writing in 2012, asserts that Major's government looks ever more successful as time goes by.[67]

Titles and honours

Styles from birth

- John Major, Esq. (1943–1979)

- John Major, Esq. MP (1979–1987)

- The Rt Hon John Major, MP (1987–1999)

- The Rt Hon John Major, CH, MP (1999–2001)

- The Rt Hon John Major, CH (2001–2005)

- The Rt Hon Sir John Major, KG, CH (2005–present)

Honours

- Lord President of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (1987)

- Member of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (1987–present)

- Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (1999)

- Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (2005)

In the New Year's Honours List of 1999 Major was made a Companion of Honour for his work on the Northern Ireland peace process.[68] In a 2003 interview he spoke about his hopes for peace in the region.[69]

On 23 April 2005, Major was made a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter by Queen Elizabeth II. He was installed at St. George's Chapel, Windsor on 13 June. Membership of the Order of the Garter is limited in number to 24, and is an honour traditionally bestowed on former British Prime Ministers and is a personal gift of the Queen.[70]

Major has so far declined a life peerage on standing down from Parliament.[71]

On 20 June 2008, Major was granted the Freedom of the City of Cork.[72]

On 26 April 2010, Major gave a speech in the Cambridge Union, after which he was granted honorary membership of the society.[73]

On 8 May 2012, Major was personally decorated at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo by HM the Emperor of Japan with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun in recognition of his invaluable contributions to Japan-UK relations through his work in the political and economic arena and also in promoting mutual understanding. While Prime Minister, Sir John had pursued energetic campaigns aimed at boosting bilateral trade - "Priority Japan" (1991-94) and "Action Japan" (1994-97). The 1991 Japan Festival also took place under his premiership.[74]

Personal life

Major married Norma Johnson (now Dame Norma Major, DBE) on 3 October 1970. She was a teacher and a member of the Young Conservatives. They met on polling day for the Greater London Council elections in London. They became engaged after only ten days.[75] They had two children; a son, James, and a daughter, Elizabeth. They have a holiday home on the coast of north Norfolk, near Weybourne, that has round-the-clock police surveillance.[76]

Major's elder brother, Terry, who died in 2007, became a minor media personality during Major's period in Downing Street, with an autobiography, Major Major. He also wrote newspaper columns, and appeared on TV shows such as Have I Got News For You. He faced criticism about his brother but always remained loyal.

His son James married model Emma Noble on 29 May 1999[77] and their son Harrison (later diagnosed as autistic) was born the following year.[78] However, it was announced in April 2003 that the couple had separated[79] They divorced later that year.[80] His daughter Elizabeth married Luke Salter on 26 March 2000,[81] having been in a relationship since 1988.[82] Salter died on 22 November 2002 from cancer,[83] just months after qualifying as a doctor.[84]

He is an enthusiastic follower of cricket, motor racing and also a supporter of Chelsea F.C.[85][86]

References

- ^ Malcolm Rifkind (15 August 1999). "Major has every right to shop Lady Thatcher". London: Independent Newspapers. Retrieved 13 Narcg 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hansard (11 December 1991). "European Council (Maastricht)". Hansard. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b "John Major". History and Tour. 10 Downing Street. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Harold MacMillan's only budget". BBC News. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Young Conservatives". John Major. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Major, John (2000) John Major The Autobiography, p.30. HarperCollins, London. ISBN 0-00-653074-5.

- ^ Seldon, Anthony (1998) Major – A Political Life, p.18. Phoenix, London. ISBN 0-7538-0145-0.

- ^ "Major and Blair's first job before UK politics". Daily Mail. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Major, John (2000) John Major The Autobiography, p.35. HarperCollins, London. ISBN 0-00-653074-5

- ^ "John Major car crash in Nigeria". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "John Major speeches during 1979 to 1987". John Major.

- ^ Deer, Brian. "MINISTERS RIG 'COLD' CASH FOR OLD". The Sunday Times (London) January 11, 1987. The Sunday Times (London). Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1987/jan/20/severe-weather-payments. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 20 January 1987. col. 747–754.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ John Major: A life in politics, BBC News, 28 September 2002

- ^ "Poll tracker: Interactive guide to the opinion polls". London: BBC News. 29 September 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Tempest, Matthew (9 February 2005). "Treasury papers reveal cost of Black Wednesday". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ Helm, Toby (10 February 2005). "Major was ready to quit over Black Wednesday". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Major, John (2000) John Major The Autobiography, p.341. HarperCollins, London. ISBN 0-00-653074-5.

- ^ "UK Polling Report". UK Polling Report. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ The Independent. London. 4 April 1993 http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/leading-article-john-major-is-he-up-to-the-job-1453316.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "BBC ON THIS DAY | 26 | 1993: Recession over – it's official". BBC News. 26 April 1962. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Philpott, John (30 December 1996). "Wanted: a warts-and-all tally of UK's jobless – Business, News". The Independent. London. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ The maxim referred to is Johnson's famous comment about J. Edgar Hoover: Johnson had once sought a way to remove Hoover from his post as head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), but upon realising that the problems involved in such a plan were insurmountable, he accepted Hoover's presence philosophically, reasoning that it would be "better to have him inside the tent pissing out, than outside pissing in".

- ^ Major, John (1999). Autobiography, pp343-44.

- ^ Routledge, Paul; Hoggart, Simon (25 July 1993). "Major hits out at Cabinet". The Observer. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199293/cmhansrd/1993-11-01/Debate-2.html. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 1 November 1993. col. 34.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Rusbridger, Alan (21 June 2004). "'Mandela helped me survive Monicagate, Arafat could not make the leap to peace – and for days John Major wouldn't take my calls'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ^ Copyright Headshift Ltd, 2003. "Bosnia Report - July - September 2000". Bosnia.org.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Attila, Marko (16 March 2011). "Sir Malcolm Rifkind: Arms embargo on Bosnia was 'the most serious mistake made by the UN' « Greater Surbiton". Greatersurbiton.wordpress.com. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Major, John (1999). Autobiography

- ^ Macintyre, Donald; Brown, Colin (27 June 1995). The Independent. London http://www.independent.co.uk/news/pm-assails-malcontent-redwood-1588458.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ ["http://www.johnmajor.co.uk/page824.html" "Mr Major's Resignation Statement"]. 27 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Interview on Breakfast With Frost". BBC News. 8 October 2000. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Who has been UK's greatest post-war PM?". BBC News. 16 September 2008.

- ^ Major, John (2000) John Major The Autobiography, p.689. HarperCollins, London. ISBN 0-00-653074-5.

- ^ Dale, Iain (10 January 2006). "The Right Hon wag". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ^ "30 January 1997: 'Weak, weak, weak'". BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Great Train Sell-off". BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Who's Who (15 February 2011). Who's Who 2011. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-2856-5. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ "Sir John Major's comments (1997 onwards)". John Major. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "John Major appointed European Chairman of the Carlyle Group". 14 May 2001. Archived from the original on 13 August 2003].

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ "Cowdrey remembered". BBC News. 30 March 2001. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Website by the OTHER media. "MCC Committee 2006–07". Lords.org. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (24 April 2011). "Royal wedding guest list includes friends, family – and a few dictators". Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Major and Currie had four-year affair". BBC News. 28 September 2002. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "The Major-Currie affair – what the papers say". Guardian. London. 30 September 2002. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "obituaries:Lord Newton of Braintree". Daily Telegraph. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Major faces legal action over affair". BBC News. 29 September 2002. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Currie interview in full". BBC News. 2 October 2002. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Treasury releases 1992 ERM papers". BBC News. 9 February 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Major denies blocking ERM papers". BBC News. 5 February 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Major permits release of Black Wednesday papers[dead link]

- ^ Bentley, Daniel (24 February 2007). "Forty million dollar Bill: Earning power of an ex-leader". The Independent. London. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ^ Brown, Colin (16 December 2006). "John Major leads calls for inquiry into conflict". The Independent. London. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Webster, Philip (28 April 2007). "Cameron snubbed again as Major rules out mayor race". The Times. London. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ BBC News Website, 'Ed Miliband asks Lib Dems to help draw up Labour policy', 13 December 10 [1]

- ^ Kirkup, James (29 April 2011). "Royal Wedding: Tony Blair not offended by lack of invite". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 9 May 2011].

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "The Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust" (Press release). Australian Government Publishing Service. 7 February 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "The Rt Hon Sir John Major in the Bow Group". Bow Group.

- ^ The Rt Hon Sir John Major KG CH - Chatham House Retrieved 29 September 2012

- ^ Steve Bell (1 October 2002). "'If only we had known back then'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ^ Bennett, Gillian (1996). ""Camera, Lights Action!": The British General Election 1992 as Narrative Event". Folklore. 107: 94–97. JSTOR 10.1086/508399.

- ^ Page 29, John Major by Robert Taylor, Haus 2006

- ^ Page 370, Major: A political life by Anthony Seldon, Weidenfield 1997

- ^ ": The Lion and the Unicorn // George Orwell // www.k-1.com/Orwell". K-1.com. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Easton, Mark (11 July 2011). "Introducing Cameronism". BBC News UK. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

Majorism and Brownism are unconvincing stubs. History appears to have decided they may have re-upholstered the settee and scattered a few cushions but they didn't alter the feng shui of the room.

- ^ Daily Telegraph 5 April 2012

- ^ "Major leads honours list for peace". BBC News. 31 December 1998. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "John Major speaks out for NI peace". BBC News. 4 April 2003. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Former PM Major becomes Sir John". BBC News. 22 April 2005. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Major to turn down peerage – accessed 15 August 2006

- ^ "Freedom of the City 2008". Corkcorp.ie. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Sponsorship Packages – section "World-famous speakers"". www.cus.org/. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Embassy of Japan in the UK - Japanese Government honours The Rt. Hon Sir John Major

- ^ "Profile at". Number10.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Brogan, Benedict (21 March 2002). "Protection bill for John Major rises to £1.5m". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ "Ex-PM Major's son in quickie divorce | Mail Online". Daily Mail. London. 29 May 1999. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Express.co.uk – Home of the Daily and Sunday Express | Express Yourself :: Emma's Major rift". Dailyexpress.co.uk. 15 September 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "James and Emma break-up | Mail Online". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "News – Uk & World News – Major'S Affair With His Son'S Blonde Teacher". People.co.uk. 28 September 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "UK | John Major's daughter weds". BBC News. 26 March 2000. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "UK | The miraculous Major-Balls". BBC News. 21 May 1999. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "UK | Major's son-in-law dies". BBC News. 22 November 2002. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Diggines, Graham (23 November 2002). "Major girl's husband dies | The Sun |News". The Sun. London. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Insert http://www.manutd.com/default.sps?pagegid=%7BC7DF7CEC-3BC3-4859-A3FD-FE4AAD215DD8%7D&newsid=325899&page=2

- ^ "The Shed – Celebrity Fans". Theshed.chelseafc.com. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

Further reading

- Major, John (1999) – Autobiography (London: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-257004-1)

- Major, John (2007) – More Than A Game: The Story of Cricket's Early Years (London: Harper Collins, ISBN 978-0-00-718364-7)

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2010) |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by John Major

- Unofficial John Major website

- The Public Whip – John Major MP voting record

- Ubben Lecture at DePauw University

- More about John Major on the Downing Street website.

- 'Prime-Ministers in the Post-War World: John Major', lecture by Vernon Bogdanor at Gresham College on 21 June 2007 (with video and audio files available for download).

- Recordings and Photos of the visit by Sir John to the College Historical Society for the Inaugural Meeting.

- Portraits of John Major at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "Archival material relating to John Major". UK National Archives.

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from August 2010

- Use dmy dates from July 2012

- John Major

- 1943 births

- Attempted assassination survivors

- British Secretaries of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

- Carlyle Group people

- Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs

- Councillors in Lambeth

- Cricket historians and writers

- English Anglicans

- Knights of the Garter

- Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK)

- Leaders of the Opposition (United Kingdom)

- Living people

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for English constituencies

- People educated at Rutlish School

- People from Carshalton

- Political scandals in the United Kingdom

- Presidents of Surrey CCC

- Presidents of the European Council

- Presidents of the United Nations Security Council

- Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- UK MPs 1979–1983

- UK MPs 1983–1987

- UK MPs 1987–1992

- UK MPs 1992–1997

- UK MPs 1997–2001