Animal rights

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2012) |

| Animal rights | |

|---|---|

| |

| Description | Nonhuman animals have interests, and those interests ought not to be discriminated against on the basis of species membership alone.[2] |

| Early proponents | Henry Salt (1851–1939) Lizzy Lind af Hageby (1878–1963) Leonard Nelson (1882–1927) |

| Notable academic proponents | |

| List | List of animal rights advocates |

| Key texts | Henry Salt's Animals' Rights (1894) Peter Singer's Animal Liberation (1975) Tom Regan's The Case for Animal Rights (1983) Gary Francione's Animals, Property, and the Law (1995) |

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

|

Animal rights is the idea that some or all nonhuman animals are entitled to the possession of their own lives, and that their most basic interests – such as an interest in not suffering – should be afforded the same consideration as the similar interests of human beings.[3] Advocates oppose the assignment of moral value and fundamental protections on the basis of species membership alone – an idea known since 1970 as speciesism, when the term was coined by Richard D. Ryder – arguing that it is a prejudice as irrational as any other.[4] They agree for the most part that animals should no longer be viewed as property, or used as food, clothing, research subjects, entertainment, or beasts of burden.[5]

Advocates approach the issue from a variety of perspectives. The abolitionist view is that animals do have moral rights, which the pursuit of incremental reform may undermine by encouraging human beings to feel comfortable about using them. Gary Francione's abolitionist position is promoting ethical veganism. He argues that animal rights groups who pursue welfare concerns, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, risk making the public feel comfortable about its use of animals. He calls such groups the "new welfarists". Tom Regan, who as a deontologist argues that at least some animals are "subjects-of-a-life," with beliefs, desires, memories, and a sense of their own future, who must be treated as ends in themselves, not as a means to an end.[6] Sentiocentrism is the theory that sentient individuals are the subject of moral concern and therefore deserve rights. Protectionists seek incremental reform in how animals are treated, with a view to ending animal use entirely, or almost entirely. This position is represented by the philosopher Peter Singer, whose focus as a utilitarian is not on moral rights, but on the argument that animals have interests, particularly an interest in not suffering, and that there is no moral or logical reason not to award those interests equal consideration. Singer's position is known as animal liberation. Multiple cultural traditions around the world, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, also support some forms of animal rights. In Islam, animal rights were recognized early by Sharia (Islamic law). Scientific studies have also provided evidence of similar evolutionary characteristics and cognitive abilities between humans and some animals[citation needed].

In parallel to the debate about moral rights, animal law is now widely taught in law schools in North America, and several prominent legal scholars[who?] support the extension of basic legal rights and personhood to at least some animals. The animals most often considered in arguments for personhood are bonobos and chimpanzees. This is supported by some animal rights academics because it would break through the species barrier, but opposed by others because it predicates moral value on mental complexity, rather than on sapience alone.[7]

Critics of animals rights argue that animals are unable to enter into a social contract, and thus cannot be possessors of rights, a view summed up by the philosopher Roger Scruton, who writes that only humans have duties, and therefore only humans have rights.[8] A parallel argument, known as the animal welfare position, is that animals may be used as resources so long as there is no unnecessary suffering; they may have some moral standing, but they are inferior in status to human beings, and insofar as they have interests, those interests may be overridden, though what counts as necessary suffering or a legitimate sacrifice of interests varies considerably.[9] Certain forms of animal rights activism, such as the destruction of fur farms and animal laboratories by the Animal Liberation Front, have also attracted criticism, including from within the animal rights movement itself,[10] as well as prompted reaction from the U.S. Congress with the enactment of the "Animal Enterprise Protection Act (amended in 2006 by the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act)".[11]

Factors that may affect attitudes towards animal rights include gender, occupation, level of education, and religion.

Historical development in the West

Moral status of animals in the ancient world

The 21st-century debates about animals can be traced to the ancient world, and the idea of a divine hierarchy. In the Book of Genesis (5th or 6th century BCE), Adam is given "dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth." Dominion need not entail property rights, but it has been interpreted over the centuries to imply ownership.[13] Animal were things to be possessed and used, whereas man was created in the image of God, and was superior to everything else in nature.[14]

The philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras (c. 580–c. 500 BCE), urged respect for animals, believing that human and nonhuman souls were reincarnated from human to animal, and vice versa.[15] Against this, Aristotle (384–322 BCE) argued that nonhuman animals had no interests of their own, ranking far below humans in the Great Chain of Being. He was the first to create a taxonomy of animals; he perceived some similarities between humans and other species, but argued for the most part that animals lacked reason (logos), reasoning (logismos), thought (dianoia, nous), and belief (doxa).[12] One of Aristotle's pupils, Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BCE) argued that animals had reason too; he opposed eating meat on the grounds that it robbed them of life and was therefore unjust.[16][17] Theophrastus did not prevail; Richard Sorabji writes that current attitudes to animals can be traced to the heirs of the Western Christian tradition selecting the hierarchy that Aristotle sought to preserve.[12]

Tom Beauchamp (2011) writes that the most extensive account in antiquity of how animals should be treated was written by the Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry (234–c. 305 CE), in his On Abstinence from Animal Food, and On Abstinence from Killing Animals.[18]

17th century: Animals as automata

Early animal protection laws in the English-speaking world

According to Richard D. Ryder, the first known animal protection legislation in the English-speaking world was passed in Ireland in 1635. It prohibited pulling wool off sheep, and the attaching of ploughs to horses' tails, referring to "the cruelty used to beasts."[19] In 1641 the first legal code to protect domestic animals in North America was passed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[20] The colony's constitution was based on The Body of Liberties by the Reverend Nathaniel Ward (1578–1652), an English lawyer, Puritan clergyman, and University of Cambridge graduate. Ward list of "rites" included rite 92: "No man shall exercise any Tirrany or Crueltie toward any bruite Creature which are usuallie kept for man's use." Historian Roderick Nash (1989) writes that, at the height of René Descartes' influence in Europe—and his view that animals were simply automata—it is significant that the New Englanders created a law that implied animals were not unfeeling machines.[21]

The Puritans passed animal protection legislation in England too. Kathleen Kete writes that animal welfare laws were passed in 1654 as part of the ordinances of the Protectorate—the government under Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), which lasted from 1653 to 1659, following the English Civil War. Cromwell disliked blood sports, which included cockfighting, cock throwing, dog fighting, bull baiting and bull running, said to tenderize the meat. These could be seen in villages and fairgrounds, and became associated with idleness, drunkenness, and gambling. Kete writes that the Puritans interpreted the biblical dominion of man over animals to mean responsible stewardship, rather than ownership. The opposition to blood sports became part of what was seen as Puritan interference in people's lives, and the animal protection laws were overturned during the Restoration, when Charles II was returned to the throne in 1660.[22]

René Descartes

[Animals] eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing. — Nicolas Malebranche (1638–1715)[24]

The great influence of the 17th century was the French philosopher, René Descartes (1596–1650), whose Meditations (1641) informed attitudes about animals well into the 20th century.[23] Writing during the scientific revolution, Descartes proposed a mechanistic theory of the universe, the aim of which was to show that the world could be mapped out without allusion to subjective experience.[25]

Hold then the same view of the dog which has lost his master, which has sought him in all the thoroughfares with cries of sorrow, which comes into the house troubled and restless, goes downstairs, goes upstairs; goes from room to room, finds at last in his study the master he loves, and betokens his gladness by soft whimpers, frisks, and caresses. There are barbarians who seize this dog, who so greatly surpasses man in fidelity and friendship, and nail him down to a table and dissect him alive, to show you the mesaraic veins! You discover in him all the same organs of feeling as in yourself. Answer me, mechanist, has Nature arranged all the springs of feeling in this animal to the end that he might not feel? — Voltaire (1694–1778)[26]

His mechanistic approach was extended to the issue of animal consciousness. Mind, for Descartes, was a thing apart from the physical universe, a separate substance, linking human beings to the mind of God. The nonhuman, on the other hand, were for Descartes nothing but complex automata, with no souls, minds, or reason. They could see, hear, and touch, but were not conscious, able to suffer, and had no language.[23]

Treatment of animals as man's duty towards himself

John Locke, Immanuel Kant

Against Descartes, the British philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) argued, in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), that animals did have feelings, and that unnecessary cruelty toward them was morally wrong, but that the right not to be harmed adhered either to the animal's owner, or to the human being who was being damaged by being cruel. Discussing the importance of preventing children from tormenting animals, he wrote: "For the custom of tormenting and killing of beasts will, by degrees, harden their minds even towards men."[27]

Locke's position echoed that of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). Paul Waldau writes that the argument can be found at 1 Corinthians (9:9–10), when Paul asks: "Is it for oxen that God is concerned? Does he not speak entirely for our sake? It was written for our sake." Christian philosophers interpreted this to mean that humans had no direct duty to nonhuman animals, but had a duty only to protect them from the effects of engaging in cruelty.[28]

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), following Aquinas, opposed the idea that humans have direct duties toward nonhumans. For Kant, cruelty to animals was wrong only because it was bad for humankind. He argued in 1785 that "cruelty to animals is contrary to man's duty to himself, because it deadens in him the feeling of sympathy for their sufferings, and thus a natural tendency that is very useful to morality in relation to other human beings is weakened."[29]

18th century: Centrality of sentience

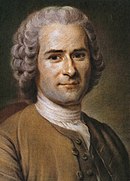

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) argued in Discourse on Inequality (1754) for the inclusion of animals in natural law on the grounds of sentience: "By this method also we put an end to the time-honoured disputes concerning the participation of animals in natural law: for it is clear that, being destitute of intelligence and liberty, they cannot recognise that law; as they partake, however, in some measure of our nature, in consequence of the sensibility with which they are endowed, they ought to partake of natural right; so that mankind is subjected to a kind of obligation even toward the brutes. It appears, in fact, that if I am bound to do no injury to my fellow-creatures, this is less because they are rational than because they are sentient beings: and this quality, being common both to men and beasts, ought to entitle the latter at least to the privilege of not being wantonly ill-treated by the former."[30] In his treatise on education, Emile, or On Education (1762), he encouraged parents to raise their children on a vegetarian diet.

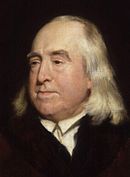

Jeremy Bentham

Four years later, one of the founders of modern utilitarianism, the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), although opposed to the concept of natural rights, argued that it was the ability to suffer that should be the benchmark of how we treat other beings. If rationality were the criterion, he argued, many humans, including infants and the disabled, would also have to be treated as though they were things.[32] He did not conclude that humans and nonhumans had equal moral significance, but argued that the latter's interests should be taken into account. He wrote in 1789, just as African slaves were being freed by the French:

The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? the question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?[33]

19th century: Emergence of jus animalium

The 19th century saw an explosion of interest in animal protection, particularly in England. Debbie Legge and Simon Brooman write that the educated classes became concerned about attitudes toward the old, the needy, children, and the insane, and that this concern was extended to nonhumans. Before the 19th century, there had been prosecutions for poor treatment of animals, but only because of the damage to the animal as property. In 1793, for example, John Cornish was found not guilty of maiming a horse after pulling the animal's tongue out; the judge ruled that Cornish could be found guilty only if there was evidence of malice toward the owner.[34]

From 1800 onwards, there were several attempts in England to introduce animal protection legislation. The first was a bill against bull baiting, introduced in April 1800 by a Scottish MP, Sir William Pulteney (1729–1805). It was opposed inter alia on the grounds that it was anti-working class, and was defeated by two votes. Another attempt was made in 1802, this time opposed by the Secretary at War, William Windham (1750–1810), who said the Bill was supported by Methodists and Jacobins who wished to "destroy the Old English character, by the abolition of all rural sports." In 1809, Lord Erskine (c. 1746–1828) introduced a bill to protect cattle and horses from malicious wounding, wanton cruelty, and beating. He told the House of Lords that animals had protection only as property: "They have no rights. [It is] that defect in the law which I seek to remedy." The Bill was passed by the Lords, but was opposed in the Commons by Windham, who said it would be used against the "lower orders" when the real culprits would be their employers.[35]

Martin's Act

If I had a donkey wot wouldn't go,

D' ye think I'd wollop him? No, no, no!

But gentle means I'd try, d' ye see,

Because I hate all cruelty.

If all had been like me, in fact,

There'd ha' been no occasion for Martin's Act.

— Music hall song inspired by the prosecution of Bill Burns for cruelty to a donkey.[36]

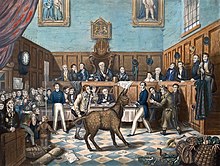

In 1821, the Treatment of Horses bill was introduced by Colonel Richard Martin (1754–1834), MP for Galway in Ireland, but it was lost among laughter in the House of Commons that the next thing would be rights for asses, dogs, and cats.[37] Nicknamed "Humanity Dick" by George IV, Martin finally succeeded in 1822 with his "Ill Treatment of Horses and Cattle Bill," or "Martin's Act," as it became known, the world's first major piece of animal protection legislation. It was given royal assent on June 22 that year as An Act to prevent the cruel and improper Treatment of Cattle, and made it an offence, punishable by fines up to five pounds or two months imprisonment, to "beat, abuse, or ill-treat any horse, mare, gelding, mule, ass, ox, cow, heifer, steer, sheep or other cattle."[34]

Legge and Brooman argue that the success of the Bill lay in the personality of "Humanity Dick," who was able to shrug off the ridicule from the House of Commons, and whose sense of humour managed to capture its attention.[34] It was Martin himself who brought the first prosecution under the Act, when he had Bill Burns, a costermonger—a street seller of fruit—arrested for beating a donkey, and paraded the animal's injuries before a reportedly astonished court. Burns was fined, and newspapers and music halls were full of jokes about how Martin had relied on the testimony of a donkey.[38]

Other countries followed suit in passing legislation or making decisions that favoured animals. In 1822, the courts in New York ruled that wanton cruelty to animals was a misdemeanor at common law.[20] In France in 1850, Jacques Philippe Delmas de Grammont succeeded in having the Loi Grammont passed, outlawing cruelty against domestic animals, and leading to years of arguments about whether bulls could be classed as domestic in order to ban bullfighting.[39] The state of Washington followed in 1859, New York in 1866, California in 1868, Florida in 1889.[40] In England, a series of amendments extended the reach of the 1822 Act, which became the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, outlawing cockfighting, baiting, and dog fighting, followed by another amendment in 1849, and again in 1876.

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

At a meeting of the Society instituted for the purpose of preventing cruelty to animals, on the 16th day of June 1824, at Old Slaughter's Coffee House, St. Martin's Lane: T F Buxton Esqr, MP, in the Chair,

It was resolved:

That a committee be appointed to superintend the Publication of Tracts, Sermons, and similar modes of influencing public opinion, to consist of the following Gentlemen:

Sir Jas. Mackintosh MP, A Warre Esqr. MP, Wm. Wilberforce Esqr. MP, Basil Montagu Esqr., Revd. A Broome, Revd. G Bonner, Revd G A Hatch, A E Kendal Esqr., Lewis Gompertz Esqr., Wm. Mudford Esqr., Dr. Henderson.

Resolved also:

That a Committee be appointed to adopt measures for Inspecting the Markets and Streets of the Metropolis, the Slaughter Houses, the conduct of Coachmen, etc.- etc, consisting of the following Gentlemen:

T F Buxton Esqr. MP, Richard Martin Esqr., MP, Sir James Graham, L B Allen Esqr., C C Wilson Esqr., Jno. Brogden Esqr., Alderman Brydges, A E Kendal Esqr., E Lodge Esqr., J Martin Esqr. T G Meymott Esqr.

A. Broome,

Honorary Secretary[38]

Richard Martin soon realized that magistrates did not take the Martin Act seriously, and that it was not being reliably enforced. Several members of parliament decided to form a society to bring prosecutions under the Act. The Reverend Arthur Broome, formerly of Balliol College, Oxford and recently appointed the vicar of Bromley-by-Bow, arranged a meeting in Old Slaughter's Coffee House in St. Martin's Lane, a London café frequented by artists and actors. The group met on June 16, 1824, and included a number of MPs: Richard Martin, Sir James Mackintosh 1765–1832), Sir Thomas Buxton (1786–1845), William Wilberforce (1759–1833), and Sir James Graham (1792–1861), who had been an MP, and who became one again in 1826. They decided to form a "Society instituted for the purpose of preventing cruelty to animals," the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, as it became known. It determined to send men to inspect slaughterhouses, Smithfield Market, where livestock had been sold since the 10th century, and to look into the treatment of horses by coachmen.[36] The Society became the Royal Society in 1840, when it was granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria, herself strongly opposed to vivisection.[41]

From 1824 onwards, several books were published that approached the issue of animal rights, rather than protection. Lewis Gompertz (1783/4–1865), one of the men who attended the first meeting of the SPCA, published Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man and of Brutes (1824), arguing that every living creature, human and nonhuman, has more right to the use of its own body than anyone else has to use it, and that our duty to promote happiness applies equally to all beings. Edward Nicholson (1849–1912), head of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, argued in Rights of an Animal (1879) that animals have the same natural right to life and liberty that human beings do, arguing against Descartes' mechanistic view—or what he called the "Neo-Cartesian snake"—that they lack consciousness.[42] Other writers of the time who explored whether animals might have natural (or moral) rights were Edward Payson Evans (1831–1917), John Muir (1838–1914), and J. Howard Moore (1862–1916), an American zoologist and author of The Universal Kinship (1906) and The New Ethics (1907).[43]

Arthur Schopenhauer

The development in England of the concept of animal rights was strongly supported by the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). He wrote that Europeans were "awakening more and more to a sense that beasts have rights, in proportion as the strange notion is being gradually overcome and outgrown, that the animal kingdom came into existence solely for the benefit and pleasure of man." He stopped short of advocating vegetarianism, arguing that, so long as an animal's death was quick, men would suffer more by not eating meat than animals would suffer by being eaten. Nevertheless, he applauded the animal protection movement in England—"To the honor, then, of the English, be it said that they are the first people who have, in downright earnest, extended the protecting arm of the law to animals."[45] He also argued against the dominant Kantian idea that animal cruelty is wrong only insofar as it brutalizes humans:

Thus, because Christian morality leaves animals out of account ... they are at once outlawed in philosophical morals; they are mere "things," mere means to any ends whatsoever. They can therefore be used for vivisection, hunting, coursing, bullfights, and horse racing, and can be whipped to death as they struggle along with heavy carts of stone. Shame on such a morality that is worthy of pariahs, chandalas, and mlechchhas, and that fails to recognize the eternal essence that exists in every living thing ...[44]

Charles Darwin

James Rachels writes that Charles Darwin's (1809–1882) On the Origin of Species (1859)—which presented the theory of evolution by natural selection—revolutionized the way humans viewed their relationship with other species. Not only did human beings have a direct kinship with other animals, but the latter had social, mental and moral lives too, Darwin argued.[46] He wrote in his Notebooks (1837): "Animals – whom we have made our slaves we do not like to consider our equals. – Do not slave holders wish to make the black man other kind?"[47] Later, in The Descent of Man (1871), he argued: "There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties," attributing to animals the power of reason, decision making, memory, sympathy and imagination.[46]

Rachels writes that Darwin noted the moral implications of the cognitive similarities, arguing that "humanity to the lower animals" was one of the "noblest virtues with which man is endowed." He was strongly opposed to any kind of cruelty to animals, including setting traps. He wrote in a letter that he supported vivisection for "real investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror ..." In 1875 he testified before a Royal Commission on Vivisection, lobbying for a bill to protect both the animals used in vivisection, and the study of physiology. Rachels writes that the animal rights advocates of the day, such as Frances Power Cobbe, did not see Darwin as an ally.[46]

Friedrich Nietzsche

Avoiding utilitarianism, Friedrich Nietzsche found other reasons to defend animals. He argued that "The sight of blind suffering is the spring of the deepest emotion."[48] He once wrote: "For man is the cruelest animal. At tragedies, bull-fights, and crucifixions hath he hitherto been happiest on earth; and when he invented his hell, behold, that was his heaven on earth."[49] Throughout his writings, he speaks of the human being as an animal.[50]

American SPCA, Frances Power Cobbe, Anna Kingsford

The first animal protection group in the United States, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), was founded by Henry Bergh in April 1866. Bergh had been appointed by President Abraham Lincoln to a diplomatic post in Russia, and had been disturbed by the treatment of animals there. He consulted with the president of the RSPCA in London, and returned to the United States to speak out against bullfights, cockfights, and the beating of horses. He created a "Declaration of the Rights of Animals," and in 1866 persuaded the New York state legislature to pass anti-cruelty legislation and to grant the ASPCA the authority to enforce it.[51]

In 1875, the Irish social reformer Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904) founded the Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection, the world's first organization opposed to animal research, which became the National Anti-Vivisection Society. In 1880, the English feminist Anna Kingsford (1846–1888) became one of the first English women to graduate in medicine, after studying for her degree in Paris, and the only student at the time to do so without having experimented on animals. She published The Perfect Way in Diet (1881), advocating vegetarianism, and in the same year founded the Food Reform Society. She was also vocal in her opposition to animal experiments.[52] In 1898, Cobbe set up the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, with which she campaigned against the use of dogs in research, coming close to success with the 1919 Dogs (Protection) Bill, which almost became law.

Ryder writes that, as the interest in animal protection grew in the late 1890s, attitudes toward animals among scientists began to harden. They embraced the idea that what they saw as anthropomorphism—the attribution of human qualities to nonhumans—was unscientific. Animals had to be approached as physiological entities only, as Ivan Pavlov wrote in 1927, "without any need to resort to fantastic speculations as to the existence of any possible subjective states." It was a position that hearkened back to Descartes in the 17th century, that nonhumans were purely mechanical, with no rationality and perhaps even no consciousness.[53]

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), the English philosopher, also argued that utilitarianism must take animals into account, writing in 1864:[year verification needed] "Nothing is more natural to human beings, nor, up to a certain point in cultivation, more universal, than to estimate the pleasures and pains of others as deserving of regard exactly in proportion to their likeness to ourselves. ... Granted that any practice causes more pain to animals than it gives pleasure to man; is that practice moral or immoral? And if, exactly in proportion as human beings raise their heads out of the slough of selfishness, they do not with one voice answer 'immoral,' let the morality of the principle of utility be for ever condemned."[54]

Henry Salt

In 1894, Henry Salt (1851–1939), a former master at Eton, who had set up the Humanitarian League to lobby for a ban on hunting the year before, published Animals' Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress.[55] He wrote that the object of the essay was to "set the principle of animals' rights on a consistent and intelligible footing."[56] Concessions to the demands for jus animalium had been made grudgingly to date, he wrote, with an eye on the interests of animals qua property, rather than as rights bearers:

Even the leading advocates of animal rights seem to have shrunk from basing their claim on the only argument which can ultimately be held to be a really sufficient one—the assertion that animals, as well as men, though, of course, to a far less extent than men, are possessed of a distinctive individuality, and, therefore, are in justice entitled to live their lives with a due measure of that "restricted freedom" to which Herbert Spencer alludes.[56]

He argued that there was no point in claiming rights for animals if those rights were subordinated to human desire, and took issue with the idea that the life of a human might have more moral worth. "[The] notion of the life of an animal having 'no moral purpose,' belongs to a class of ideas which cannot possibly be accepted by the advanced humanitarian thought of the present day—it is a purely arbitrary assumption, at variance with our best instincts, at variance with our best science, and absolutely fatal (if the subject be clearly thought out) to any full realization of animals' rights. If we are ever going to do justice to the lower races, we must get rid of the antiquated notion of a 'great gulf' fixed between them and mankind, and must recognize the common bond of humanity that unites all living beings in one universal brotherhood."[56]

20th century: Animal rights movement

Brown Dog Affair, Lizzy Lind af Hageby

In 1902, Lizzy Lind af Hageby (1878–1963), a Swedish feminist, and a friend, Lisa Shartau, traveled to England to study medicine at the London School of Medicine for Women, intending to learn enough to become authoritative anti-vivisection campaigners. In the course of their studies, they witnessed several animal experiments, and published the details as The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology (1903). Their allegations included that they had seen a brown terrier dog dissected while conscious, which prompted angry denials from the researcher, William Bayliss, and his colleagues. After Stephen Coleridge of the National Anti-Vivisection Society accused Bayliss of having violated the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876, Bayliss sued and won, convincing a court that the animal had been anaesthetized as required by the Act.[57]

In response, anti-vivisection campaigners commissioned a statue of the dog to be erected in Battersea Park in 1906, with the plaque: "Men and Women of England, how long shall these Things be?" The statue caused uproar among medical students, leading to frequent vandalism of the statue and the need for a 24-hour police guard. The affair culminated in riots in 1907 when 1,000 medical students clashed with police, suffragettes and trade unionists in Trafalgar Square. Battersea Council removed the statue from the park under cover of darkness two years later.[57] Coral Lansbury (1985) and Hilda Kean (1998) write that the significance of the affair lay in the relationships that formed in support of the "Brown Dog Done to Death," which became a symbol of the oppression the women's suffrage movement felt at the hands of the male political and medical establishment. Kean argues that both sides saw themselves as heirs to the future. The students saw the women and trade unionists as representatives of anti-science sentimentality, while the women saw themselves as progressive, with the students and their teachers belonging to a previous age.[58]

Development of veganism

Members of the English Vegetarian Society who avoided eggs and animal milk in the 19th and early 20th century were known as strict vegetarians. The International Vegetarian Union cites an article about alternatives to shoe leather in the Vegetarian Society's magazine in 1851 as evidence of the existence of a group that sought to avoid animal products entirely. There was increasing unease within the Society from the start of the 20th century onwards about consuming eggs and milk, and in 1923 its magazine wrote that the "ideal position for vegetarians is abstinence from animal products." Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) argued in 1931 before a meeting of the Society in London that vegetarianism should be pursued in the interests of animals, and not only as a human health issue. He met both Henry Salt and Anna Kingsford, and read Salt's A Plea for Vegetarianism (1880); Salt wrote in the pamphlet that "a Vegetarian is still regarded, in ordinary society, as little better than a madman."[59] In 1944, several members, led by Donald Watson (1910–2005), decided to break from the Vegetarian Society over the issue of eggs and milk. Watson coined the term "vegan" for those whose diet included no animal products, and they formed the British Vegan Society on November 1 that year.[60]

Tierschutzgesetz

On coming to power in January 1933, the Nazi Party passed a comprehensive set of animal protection laws. The laws were similar to those that already existed in England, though more detailed and with severe penalties for breaking them. Arnold Arluke and Boria Sax write that the Nazis tried to abolish the distinction between humans and animals, not by treating animals as persons, but by treating persons as animals.[61] Kathleen Kete writes that it was the worst possible answer to the question of what our relationship with other species ought to be.[62]

In April 1933 they passed laws regulating the slaughter of animals; one of their targets was kosher slaughter. In November the Tierschutzgesetz, or animal protection law, was introduced, with Adolf Hitler announcing an end to animal cruelty: "Im neuen Reich darf es keine Tierquälerei mehr geben." ("In the new Reich, no more animal cruelty will be allowed.") It was followed in July 1934 by the Reichsjagdgesetz, prohibiting hunting; in July 1935 by the Naturschutzgesetz, environmental legislation; in November 1937 by a law regulating animal transport in cars; and in September 1938 by a similar law dealing with animals on trains.[63] Several senior Nazis, including Hitler, Rudolf Hess, Joseph Goebbels, and Heinrich Himmler, adopted some form of vegetarianism, though by most accounts not strictly.[64] Despite the apparent concern for animals, Arluke and Sax (1992) write that, to earn their stripes, SS personnel who worked with German shepherd dogs allegedly had to break their dog's neck in front of an officer.[61]

Shortly before the Tierschutzgesetz was introduced, vivisection was first banned, then restricted. Animal research was viewed as part of "Jewish science," and "internationalist" medicine, indicating a mechanistic mind that saw nature as something to be dominated, rather than respected. Hermann Göring first announced a ban on August 16, 1933, but Hitler's personal physician, Dr. Morrel, persuaded Hitler that this was not in the interests of German research, and in particular defence research.[65] The ban was therefore revised three weeks later, when eight conditions were announced under which animal tests could be conducted, with a view to reducing pain and unnecessary experiments.[66] Primates, horses, dogs, and cats were given special protection, and licenses to conduct vivisection were to be given to institutions, not to individuals.[61] The removal of the ban was justified with the announcement: "It is a law of every community that, when necessary, single individuals are sacrificed in the interests of the entire body."[65]

Medical experiments were later conducted on Jews and Romani children in camps, particularly in Auschwitz by Dr. Josef Mengele, and on others regarded as inferior, including prisoners-of-war. Because the human subjects were often in such poor health, researchers feared that the results of the experiments were unreliable, and so human experiments were repeated on animals. Dr Hans Nachtheim, for example, induced epilepsy on human adults and children without their consent by injecting them with cardiazol, then repeated the experiments on rabbits to check the results.[65]

Increase in animal use

Despite the proliferation of animal protection legislation, animals still had no legal rights. Debbie Legge writes that existing legislation was very much tied to the idea of human interests, whether protecting human sensibilities by outlawing cruelty, or protecting property rights by making sure animals were not damaged. The over-exploitation of fishing stocks, for example, is viewed as harming the environment for people; the hunting of animals to extinction means that humans in the future will derive no enjoyment from them; poaching results in financial loss to the owner, and so on.[40] Notwithstanding the interest in animal welfare of the previous century, the situation for animals arguably deteriorated in the 20th century, particularly after the Second World War. This was in part because of the increase in the numbers used in animal research—300 in the UK in 1875, 19,084 in 1903, and 2.8 million in 2005 (50–100 million worldwide), and a modern annual estimated range of 10 million to upwards of 100 million in the US[67]—but mostly because of the industrialization of farming, which saw billions of animals raised and killed for food on a scale not possible before the war.[68]

Development of direct action

In the early 1960s in England, support for animal rights began to coalesce around the issue of blood sports, particularly hunting deer, foxes, and otters using dogs, an aristocratic and middle-class English practice, stoutly defended in the name of protecting rural traditions. The psychologist Richard D. Ryder – who became involved with the animal rights movement in the late 1960s – writes that the new chair of the League Against Cruel Sports tried in 1963 to steer it away from confronting members of the hunt, which triggered the formation that year of a direct action breakaway group, the Hunt Saboteurs Association. This was set up by a journalist, John Prestige, who had witnessed a pregnant deer being chased into a village and killed by the Devon and Somerset Staghounds. The practice of sabotaging hunts (for example, by misleading the dogs with scents or horns) spread throughout south-east England, particularly around university towns, leading to violent confrontations when the huntsmen attacked the "sabs".[69]

The controversy spread to the RSPCA, which had arguably grown away from its radical roots to become a conservative group with charity status and royal patronage. It had failed to speak out against hunting, and indeed counted huntsmen among its members. As with the League Against Cruel Sports, this position gave rise to a splinter group, the RSPCA Reform Group, which sought to radicalize the organization, leading to chaotic meetings of the group's ruling Council, and successful (though short-lived) efforts to change it from within by electing to the Council members who would argue from an animal rights perspective, and force the RSPCA to address issues such as hunting, factory farming, and animal experimentation. Ryder himself was elected to the Council in 1971, and served as its chair from 1977 to 1979.[69]

Formation of the Oxford group

The same period saw writers and academics begin to speak out again in favour of animal rights. Ruth Harrison published Animal Machines (1964), an influential critique of factory farming, and on October 10, 1965, the novelist Brigid Brophy had an article, "The Rights of Animals," published in The Sunday Times.[53] She wrote:

The relationship of homo sapiens to the other animals is one of unremitting exploitation. We employ their work; we eat and wear them. We exploit them to serve our superstitions: whereas we used to sacrifice them to our gods and tear out their entrails in order to foresee the future, we now sacrifice them to science, and experiment on their entrail in the hope—or on the mere offchance—that we might thereby see a little more clearly into the present ... To us it seems incredible that the Greek philosophers should have scanned so deeply into right and wrong and yet never noticed the immorality of slavery. Perhaps 3000 years from now it will seem equally incredible that we do not notice the immorality of our own oppression of animals.[53]

Robert Garner writes that Harrison's book and Brophy's article led to an explosion of interest in the relationship between humans and nonhumans.[70] In particular, Brophy's article was discovered in or around 1969 by a group of postgraduate philosophy students at the University of Oxford, Roslind and Stanley Godlovitch (husband and wife from Canada), John Harris, and David Wood, now known as the Oxford Group. They decided to put together a symposium to discuss the theory of animal rights.[53]

Around the same time, Richard Ryder wrote several letters to The Daily Telegraph criticizing animal experimentation, based on incidents he had witnessed in laboratories. The letters, published in April and May 1969, were seen by Brigid Brophy, who put Ryder in touch with the Godlovitches and Harris. Ryder also started distributing pamphlets in Oxford protesting against experiments on animals; it was in one of these pamphlets in 1970 that he coined the term "speciesism" to describe the exclusion of nonhuman animals from the protections offered to humans.[71] He subsequently became a contributor to the Godlovitches' symposium, as did Harrison and Brophy, and it was published in 1971 as Animals, Men and Morals: An Inquiry into the Maltreatment of Non-humans.[72]

Publication of Animal Liberation

In 1970, over lunch in Oxford with fellow student Richard Keshen, a vegetarian, Australian philosopher Peter Singer came to believe that, by eating animals, he was engaging in the oppression of other species. Keshen introduced Singer to the Godlovitches, and in 1973 Singer reviewed their book for The New York Review of Books. In the review, he used the term "animal liberation," writing:

We are familiar with Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and a variety of other movements. With Women's Liberation some thought we had come to the end of the road. Discrimination on the basis of sex, it has been said, is the last form of discrimination that is universally accepted and practiced without pretense ... But one should always be wary of talking of "the last remaining form of discrimination." ... Animals, Men and Morals is a manifesto for an Animal Liberation movement.[73]

On the strength of his review, The New York Review of Books took the unusual step of commissioning a book from Singer on the subject, published in 1975 as Animal Liberation, now one of the animal rights movement's canonical texts. Singer based his arguments on the principle of utilitarianism – the view, in its simplest form, that an act is right if it leads to the "greatest happiness of the greatest number," a phrase first used in 1776 by Jeremy Bentham.[73] He argued in favor of the equal consideration of interests, the position that there are no grounds to suppose that a violation of the basic interests of a human—for example, an interest in not suffering—is different in any morally significant way from a violation of the basic interests of a nonhuman.[74] Singer used the term "speciesism" in the book, citing Ryder, and it stuck, becoming an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1989.[75]

The book's publication triggered a groundswell of scholarly interest in animal rights. Richard Ryder's Victims of Science: The Use of Animals in Research (1975) appeared, followed by Andrew Linzey's Animal Rights: A Christian Perspective (1976), and Stephen R. L. Clark's The Moral Status of Animals (1977). A Conference on Animal Rights was organized by Ryder and Linzey at Trinity College, Cambridge, in August 1977. This was followed by Mary Midgley's Beast And Man: The Roots of Human Nature (1978), then Animal Rights–A Symposium (1979), which included the papers delivered to the Cambridge conference. From 1982 onwards, a series of articles by Tom Regan led to his The Case for Animal Rights (1984), in which he argues that nonhuman animals are "subjects-of-a-life," and therefore possessors of moral rights, a work regarded as a key text in animal rights theory.[70] Regan wrote in 2001 that philosophers had written more about animal rights in the previous 20 years than in the 2,000 years before that.[76] Garner writes that Charles Magel's bibliography, Keyguide to Information Sources in Animal Rights (1989), contains 10 pages of philosophical material on animals up to 1970, but 13 pages between 1970 and 1989 alone.[77]

Founding of the Animal Liberation Front

In 1971 a law student, Ronnie Lee, formed a branch of the Hunt Saboteurs Association in Luton, later calling it the Band of Mercy after a 19th-century RSPCA youth group. The Band attacked hunters' vehicles by slashing tires and breaking windows, calling it "active compassion." In November 1973 they engaged in their first act of arson when they set fire to a Hoechst Pharmaceuticals research laboratory, claiming responsibility as a "nonviolent guerilla organization dedicated to the liberation of animals from all forms of cruelty and persecution at the hands of mankind."[78]

Lee and another activist were sentenced to three years in prison in 1974, paroled after 12 months. In 1976 Lee brought together the remaining Band of Mercy activists along with some fresh faces to start a leaderless resistance movement, calling it the Animal Liberation Front (ALF).[78] ALF activists see themselves as a modern Underground Railroad, passing animals removed from farms and laboratories to sympathetic veterinarians, safe houses and sanctuaries.[79] Some activists also engage in threats, intimidation, and arson, acts that have lost the movement sympathy in mainstream public opinion.[80]

The decentralized model of activism is frustrating for law enforcement organizations, who find the networks difficult to infiltrate, because they tend to be organized around friends.[81] In 2005, the US Department of Homeland Security indicated how seriously it takes the ALF when it included them in a list of domestic terrorist threats.[82] The tactics of some of the more determined ALF activists are anathema to many animal rights advocates, such as Singer, who regard the movement as something that should occupy the moral high ground. ALF activists respond to the criticism with the argument that, as Ingrid Newkirk puts it, "Thinkers may prepare revolutions, but bandits must carry them out."[83]

Animal Rights International

Henry Spira (1927–1998), a former seaman and civil rights activist, became the most notable of the new animal advocates in the United States. A proponent of gradual change, he formed Animal Rights International in 1974, and introduced the idea of "reintegrative shaming," whereby a relationship is formed between a group of animal rights advocates and a corporation they see as misusing animals, with a view to obtaining concessions or halting a practice. It is a strategy that has been widely adopted, most notably by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.[84]

Spira's first campaign was in opposition to the American Museum of Natural History in 1976, where cats were being experimented on, research that he persuaded them to stop. His most notable achievement was in 1980, when he convinced the cosmetics company Revlon to stop using the Draize test, which involves toxicity tests on the skin or in the eyes of animals. He took out a full-page ad in several newspapers, featuring a rabbit with sticking plaster over the eyes, and the caption, "How many rabbits does Revlon blind for beauty's sake?" Revlon stopped using animals for cosmetics testing, donated money to help set up the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing, and was followed by other leading cosmetics companies.[85]

21st century: Developments

In 1999, New Zealand passed a new Animal Welfare Act that had the effect of banning experiments on "non-human hominids."[86]

Also in 1999, Public Law 106-152 (Title 18, Section 48) was put into action. This law makes it a felony to create, sell, or possess videos showing animal cruelty with the intention of profiting financially from them. <http://www.pet-abuse.com/pages/animal_cruelty/crush_videos.php#ixzz2C6yKSljR>

In 2005, the Austrian parliament banned experiments on apes, unless they are performed in the interests of the individual ape.[86] Also in Austria, the Supreme Court ruled in January 2008 that a chimpanzee (called Matthew Hiasl Pan by those advocating for his personhood) was not a person, after the Association Against Animal Factories sought personhood status for him because his custodians had gone bankrupt. The chimpanzee had been captured as a baby in Sierra Leone in 1982, then smuggled to Austria to be used in pharmaceutical experiments, but was discovered by customs officials when he arrived in the country, and was taken to a shelter instead. He was kept there for 25 years, until the group that ran the shelter went bankrupt in 2007. Donors offered to help him, but under Austrian law only a person can receive personal gifts, so any money sent to support him would be lost to the shelter's bankruptcy. The Association appealed the ruling to the European Court of Human Rights. The lawyer proposing the chimpanzee's personhood asked the court to appoint a legal guardian for him and to grant him four rights: the right to life, limited freedom of movement, personal safety, and the right to claim property.[87]

In June 2008, a committee of Spain's national legislature became the first to vote for a resolution to extend limited rights to nonhuman primates. The parliamentary Environment Committee recommended giving chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans the right not to be used in medical experiments or in circuses, and recommended making it illegal to kill apes, except in self-defense, based upon the rights recommended by the Great Ape Project.[88] The committee's proposal has not yet been enacted into law.[89]

From 2009 onwards, several countries outlawed the use of some or all animals in circuses, starting with Bolivia, and followed by several countries in Europe, Scandinavia, the Middle East, and Singapore.[90]

In 2010, the government in Catalonia passed a motion to outlaw bull fighting, the first such ban in Spain.[91] In 2011, PETA sued SeaWorld over the captivity of five orcas in San Diego and Orlando, arguing that the whales were being treated as slaves. It was the first time the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which outlaws slavery and involuntary servitude, was cited in court to protect nonhuman rights. A federal judge dismissed the case in February 2012.[92]

Indian subcontinent

Religions

Robert Garner writes that both Hindu and Buddhist societies abandoned animal sacrifice and embraced vegetarianism from the 3rd century BCE. Several kings in India built hospitals for animals, and the emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE) issued orders against hunting and animal slaughter, in line with ahimsa, the doctrine of non-violence. Garner writes that Jainism took this idea further. Jains believe that no living creature should be harmed, and they are known to clear the path in front of them by sweeping it to protect insect life.[93]

Legal actions in the 21st century

Paul Waldau writes that, in 2000, the High Court in Kerala used the language of "rights" in relation to circus animals, ruling that they are "beings entitled to dignified existence" under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The ruling said that if human beings are entitled to these rights, animals should be too. The court went beyond the requirements of the Constitution that all living beings should be shown compassion, and said: "It is not only our fundamental duty to show compassion to our animal friends, but also to recognise and protect their rights." Waldau writes that other courts in India and one court in Sri Lanka have used similar language.[86]

In 2012, the Indian government issued an extensive ban of vivisection in education and research.[94]

Islam

Animal rights were recognized early by the Sharia (Islamic law). This recognition is based on both the Qur'an and the Hadith. In the Qur'an, there are many references to animals, all positive. They have souls, form communities, communicate with God and worship Him in their own way. The Prophet Muhammad forbade his followers to harm any animal and asked them to respect the rights of animals. It is a distinctive characteristic of the Shar`iah that all animals have legal rights. Othman Llewellyn even argues that Shari`ah has mechanisms for the full repair of injuries suffered by non-human creatures including their representation in court, assessment of injuries and awarding of relief to them. The classical Muslim jurist `Izz ad-Din ibn `Abd as-Salam, who flourished during the thirteenth century, formulated the following statement of animal rights:

“The rights of livestock and animals upon man: these are that he spend on them the provision that their kinds require, even if they have aged or sickened such that no benefit comes from them; that he not burden them beyond what they can bear; that he not put them together with anything by which they would be injured, whether of their own kind or other species, and whether by breaking their bones or butting or wounding; that he slaughters them with kindness when he slaughters them, and neither flay their skins nor break their bones until their bodies have become cold and their lives have passed away; that he not slaughter their young within their sight, but that he isolate them; that he makes comfortable their resting places and watering places; that he puts their males and females together during their mating seasons; that he not discard those which he takes as game; and neither shoots them with anything that breaks their bones nor brings about their destruction by any means that renders their meat unlawful to eat.”

Philosophical and legal approaches

Overview

The two main philosophical approaches to animal rights are utilitarian and rights-based. The former is exemplified by Peter Singer, and the latter by Tom Regan and Gary Francione. Their differences reflect a distinction philosophers draw between ethical theories that judge the rightness of an act by its consequences (consequentialism/teleological ethics, or utilitarianism), and those that focus on the principle behind the act, almost regardless of consequences (deontological ethics). Deontologists argue that there are acts we should never perform, even if failing to do so entails a worse outcome.[95]

There are a number of positions that can be defended from a consequentalist or deontologist perspective, including the capabilities approach, represented by Martha Nussbaum, and the egalitarian approach, which has been examined by Ingmar Persson and Peter Vallentyne. The capabilities approach focuses on what individuals require to fulfill their capabilities: Nussbaum (2006) argues that animals need a right to life, some control over their environment, company, play, and physical health.[96] Stephen R. L. Clark, Mary Midgley, and Bernard Rollin also discuss animal rights in terms of animals being permitted to lead a life appropriate for their kind.[97] Egalitarianism favors an equal distribution of happiness among all individuals, which makes the interests of the worse off more important than those of the better off.[98] Another approach, virtue ethics, holds that in considering how to act we should consider the character of the actor, and what kind of moral agents we should be; Rosalind Hursthouse has suggested an approach to animal rights based on virtue ethics.[99] Mark Rowlands has proposed a contractarian approach.[100]

Utilitarianism

They talk about this thing in the head; what do they call it? ["Intellect," whispered someone nearby.] That's it. What's that got to do with women's rights or Negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full? — Sojourner Truth[101]

Nussbaum (2004) writes that utilitarianism, starting with Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, has contributed more to the recognition of the moral status of animals than any other ethical theory.[102] The utilitarian philosopher most associated with animal rights is Peter Singer, professor of bioethics at Princeton University. Singer is not a rights theorist, but uses the language of rights to discuss how we ought to treat individuals. He is a preference utilitarian, meaning that he judges the rightness of an act by the extent to which it satisfies the preferences (interests) of those affected.[103]

His position is that there is no reason not to give equal consideration to the interests of human and nonhumans, though his principle of equality does not require identical treatment. A mouse and a man both have an interest in not being kicked, and there are no moral or logical grounds for failing to accord those interests equal weight. Interests are predicated on the ability to suffer, nothing more, and once it is established that a being has interests, those interests must be given equal consideration.[104] Singer quotes the English philosopher Henry Sidgwick (1838–1900): "The good of any one individual is of no more importance, from the point of view ... of the Universe, than the good of any other."[74]

Singer argues that equality of consideration is a prescription, not an assertion of fact: if the equality of the sexes were based only on the idea that men and women were equally intelligent, we would have to abandon the practice of equal consideration if this were later found to be false. But the moral idea of equality does not depend on matters of fact such as intelligence, physical strength, or moral capacity. Equality therefore cannot be grounded on the outcome of scientific investigations into the intelligence of nonhumans. All that matters is whether they can suffer.[105]

Commentators on all sides of the debate now accept that animals suffer and feel pain, although it was not always so. Bernard Rollin, professor of philosophy, animal sciences, and biomedical sciences at Colorado State University, writes that Descartes' influence continued to be felt until the 1980s. Veterinarians trained in the US before 1989 were taught to ignore pain, he writes, and at least one major veterinary hospital in the 1960s did not stock narcotic analgesics for animal pain control. In his interactions with scientists, he was often asked to "prove" that animals are conscious, and to provide "scientifically acceptable" evidence that they could feel pain.[106] Scientific publications have made it clear since the 1980s that the majority of researchers do believe animals suffer and feel pain, though it continues to be argued that their suffering may be reduced by an inability to experience the same dread of anticipation as humans, or to remember the suffering as vividly.[107] The problem of animal suffering, and animal consciousness in general, arose primarily because it was argued that animals have no language. Singer writes that, if language were needed to communicate pain, it would often be impossible to know when humans are in pain, though we can observe pain behavior and make a calculated guess based on it. He argues that there is no reason to suppose that the pain behavior of nonhumans would have a different meaning from the pain behavior of humans.[108]

Subjects-of-a-life

Tom Regan, professor emeritus of philosophy at North Carolina State University, argues in The Case for Animal Rights (1983) that nonhuman animals are what he calls "subjects-of-a-life," and as such are bearers of rights.[109] He writes that, because the moral rights of humans are based on their possession of certain cognitive abilities, and because these abilities are also possessed by at least some nonhuman animals, such animals must have the same moral rights as humans. Although only humans act as moral agents, both marginal-case humans, such as infants, and at least some nonhumans must have the status of "moral patients." Moral patients are unable to formulate moral principles, and as such are unable to do right or wrong, even though what they do may be beneficial or harmful. Only moral agents are able to engage in moral action. Animals for Regan have "intrinsic value" as subjects-of-a-life, and cannot be regarded as a means to an end, a view that places him firmly in the abolitionist camp. His theory does not extend to all animals, but only to those that can be regarded as subjects-of-a-life.[109] He argues that all normal mammals of at least one year of age would qualify:

... individuals are subjects-of-a-life if they have beliefs and desires; perception, memory, and a sense of the future, including their own future; an emotional life together with feelings of pleasure and pain; preference- and welfare-interests; the ability to initiate action in pursuit of their desires and goals; a psychophysical identity over time; and an individual welfare in the sense that their experiential life fares well or ill for them, logically independently of their utility for others and logically independently of their being the object of anyone else's interests.[109]

Whereas Singer is primarily concerned with improving the treatment of animals and accepts that, in some hypothetical scenarios, individual animals might be used legitimately to further human or nonhuman ends, Regan believes we ought to treat nonhuman animals as we would humans. He applies the strict Kantian ideal (which Kant himself applied only to humans) that they ought never to be sacrificed as a means to an end, and must be treated as ends in themselves.[110]

Abolitionism

Gary Francione, professor of law and philosophy at Rutgers School of Law-Newark, is a leading abolitionist writer, arguing that animals need only one right, the right not to be owned. Everything else would follow from that paradigm shift. He writes that, although most people would condemn the mistreatment of animals, and in many countries there are laws that seem to reflect those concerns, "in practice the legal system allows any use of animals, however abhorrent." The law only requires that any suffering not be "unnecessary." In deciding what counts as "unnecessary," an animal's interests are weighed against the interests of human beings, and the latter almost always prevail.[111]

Francione's Animals, Property, and the Law (1995) was the first extensive jurisprudential treatment of animal rights. In it, Francione compares the situation of animals to the treatment of slaves in the United States, where legislation existed that appeared to protect them, while the courts ignored that the institution of slavery itself rendered the protection unenforceable.[112] He offers as an example the United States Animal Welfare Act, which he describes as an example of symbolic legislation, intended to assuage public concern about the treatment of animals, but difficult to implement.[113]

He argues that a focus on animal welfare, rather than animal rights, may worsen the position of animals by making the public feel comfortable about using them and entrenching the view of them as property. He calls animal rights group who pursue animal welfare issues, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, the "new welfarists," arguing that they have more in common with 19th-century animal protectionists than with the animal rights movement; indeed, the terms "animal protection" and "protectionism" are increasingly favored. His position in 1996 was that there is no animal rights movement in the United States.[114]

Contractarianism

Mark Rowlands, professor of philosophy at the University of Florida, has proposed a contractarian approach, based on the original position and the veil of ignorance—a "state of nature" thought experiment that tests intuitions about justice and fairness—in John Rawls's A Theory of Justice (1971). In the original position, individuals choose principles of justice (what kind of society to form, and how primary social goods will be distributed), unaware of their individual characteristics—their race, sex, class, or intelligence, whether they are able-bodied or disabled, rich or poor—and therefore unaware of which role they will assume in the society they are about to form. The idea is that, operating behind the veil of ignorance, they will choose a social contract in which there is basic fairness and justice for them no matter the position they occupy. Rawls did not include species membership as one of the attributes hidden from the decision makers in the original position. Rowlands proposes extending the veil of ignorance to include rationality, which he argues is an undeserved property similar to characteristics such as race, sex and intelligence.[100]

Prima facie rights theory

American philosopher Timothy Garry has proposed an approach that deems nonhuman animals worthy of prima facie rights. In a philosophical context, a prima facie (Latin for "on the face of it" or "at first glance") right is one that appears to be applicable at first glance, but upon closer examination may be outweighed by other considerations. In his book Ethics: A Pluralistic Approach to Moral Theory, Lawrence Hinman characterizes such rights as "the right is real but leaves open the question of whether it is applicable and overriding in a particular situation".[115] The idea that nonhuman animals are worthy of prima facie rights is to say that, in a sense, animals do have rights. However, these rights can be overridden by many other considerations, especially those conflicting a human's right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Garry supports his view arguing:

... if a nonhuman animal were to kill a human being in the U.S., it would have broken the laws of the land and would probably get rougher sanctions than if it were a human. My point is that like laws govern all who interact within a society, rights are to be applied to all beings who interact within that society. This is not to say these rights endowed by humans are equivalent to those held by nonhuman animals, but rather that if humans possess rights then so must all those who interact with humans.[116]

In sum, Garry suggests that humans have obligations to nonhuman animals; however, animals do not, and ought not to, have uninfringible rights against humans.

Feminism and animal rights

Women have played a central role in animal advocacy since the 19th century.[117] The anti-vivisection movement in the 19th and early 20th century in England and the United States was largely run by women, including Francis Power Cobbe, Anna Kingsford, Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Caroline Earle White (1833–1916).[118] Garner writes that 70 per cent of the membership of the Victoria Street Society (one of the anti-vivisection groups founded by Cobbe) were women, as were 70 per cent of the membership of the British RSPCA in 1900.[119]

The modern animal advocacy movement has a similar representation of women, though Garner (2005) writes that they are not invariably in leadership positions: during the March for Animals in Washington, D.C., in 1990—the largest animal rights demonstration held until then in the United States—most of the participants were women, but most of the platform speakers were men.[120] Nevertheless, several influential animal advocacy groups have been founded by women, including the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection by Cobbe in London in 1898; the Animal Welfare Board of India by Rukmini Devi Arundale in 1962; and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, co-founded by Ingrid Newkirk in 1980. In the Netherlands, Marianne Thieme and Esther Ouwehand were elected to parliament in 2006 representing the Party for Animals.

The preponderance of women in the movement has led to a body of academic literature exploring feminism and animal rights; feminism and vegetarianism or veganism; the oppression of women and animals; and the male association of women and animals with nature and emotion, rather than reason—an association that several feminist writers have embraced.[117] Lori Gruen writes that women and animals serve the same symbolic function in a patriarchal society: both are "the used," the dominated, submissive "Other."[121] When the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Thomas Taylor (1758–1835), a Cambridge philosopher, responded with an anonymous parody, A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes (1792), showing that Wollstonecraft's arguments for women's rights could be applied equally to animals, a position he intended as an reductio ad absurdum.[122]

Critics

R. G. Frey

R. G. Frey, professor of philosophy at Bowling Green State University, is a preference utilitarian, as is Singer, but reaches a very different conclusion, arguing in Interests and Rights (1980) that animals have no interests for the utilitarian to take into account. Frey argues that interests are dependent on desire, and that no desire can exist without a corresponding belief. Animals have no beliefs, because a belief state requires the ability to hold a second-order belief—a belief about the belief—which he argues requires language: "If someone were to say, e.g. 'The cat believes that the door is locked,' then that person is holding, as I see it, that the cat holds the declarative sentence 'The door is locked' to be true; and I can see no reason whatever for crediting the cat or any other creature which lacks language, including human infants, with entertaining declarative sentences."[123]

Carl Cohen

Carl Cohen, professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan, argues that rights holders must be able to distinguish between their own interests and what is right. "The holders of rights must have the capacity to comprehend rules of duty governing all, including themselves. In applying such rules, [they] ... must recognize possible conflicts between what is in their own interest and what is just. Only in a community of beings capable of self-restricting moral judgments can the concept of a right be correctly invoked." Cohen rejects Singer's argument that, since a brain-damaged human could not make moral judgments, moral judgments cannot be used as the distinguishing characteristic for determining who is awarded rights. Cohen writes that the test for moral judgment "is not a test to be administered to humans one by one," but should be applied to the capacity of members of the species in general.[124]

Richard Posner

Judge Richard Posner of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit debated the issue of animal rights in 2001 with Peter Singer.[126] Posner argues that his moral intuition tells him "that human beings prefer their own. If a dog threatens a human infant, even if it requires causing more pain to the dog to stop it, than the dog would have caused to the infant, then we favour the child. It would be monstrous to spare the dog."[125]

Singer challenges this by arguing that formerly unequal rights for gays, women, and certain races were justified using the same set of intuitions. Posner replies that equality in civil rights did not occur because of ethical arguments, but because facts mounted that there were no morally significant differences between humans based on race, sex, or sexual orientation that would support inequality. If and when similar facts emerge about humans and animals, the differences in rights will erode too. But facts will drive equality, not ethical arguments that run contrary to instinct, he argues. Posner calls his approach "soft utilitarianism," in contrast to Singer's "hard utilitarianism." He argues:

The "soft" utilitarian position on animal rights is a moral intuition of many, probably most, Americans. We realize that animals feel pain, and we think that to inflict pain without a reason is bad. Nothing of practical value is added by dressing up this intuition in the language of philosophy; much is lost when the intuition is made a stage in a logical argument. When kindness toward animals is levered into a duty of weighting the pains of animals and of people equally, bizarre vistas of social engineering are opened up.[125]

Roger Scruton

Roger Scruton, the British philosopher, argues that rights imply obligations. Every legal privilege, he writes, imposes a burden on the one who does not possess that privilege: that is, "your right may be my duty." Scruton therefore regards the emergence of the animal rights movement as "the strangest cultural shift within the liberal worldview," because the idea of rights and responsibilities is, he argues, distinctive to the human condition, and it makes no sense to spread them beyond our own species. He accuses animal rights advocates of "pre-scientific" anthropomorphism, attributing traits to animals that are, he says, Beatrix Potter-like, where "only man is vile." It is within this fiction that the appeal of animal rights lies, he argues. The world of animals is non-judgemental, filled with dogs who return our affection almost no matter what we do to them, and cats who pretend to be affectionate when, in fact, they care only about themselves. It is, he argues, a fantasy, a world of escape.[8]

Continuity between humans and nonhuman animals

Evolutionary studies have provided explanations of altruistic behaviours in humans and nonhuman animals, and suggest similarities between humans and some nonhumans.[127] Scientists such as Jane Goodall and Richard Dawkins believe in the capacity of nonhuman great apes, humans' closest relatives, to possess rationality and self-awareness.[128] In 2010, research led by psychologist Diana Reiss and zoologist Lori Marino was presented to a conference in San Diego, suggesting that dolphins are second in intelligence only to human beings, and concluded that they should be regarded as nonhuman persons. Marino used MRI scans to compare the dolphin and primate brain; she said the scans indicated there was "psychological continuity" between dolphins and humans. Reiss's research suggested that dolphins are able to solve complex problems, use tools, and pass the mirror test, using a mirror to inspect parts of their bodies.[129]

Studies have established links between interpersonal violence and animal cruelty.[130][131]

Public attitudes

According to a paper published in 2000 by Harold Herzog and Lorna Dorr, previous academic surveys of attitudes towards animal rights have tended to suffer from small sample sizes and non-representative groups.[132] However, a number of factors appear to correlate with the attitude of individuals regarding the treatment of animals and animal rights. These include gender, age, occupation, religion, and level of education. There has also been evidence to suggest that prior experience with companion animals may be a factor in people's attitudes.[133]

Gender has repeatedly been shown to be a factor in how people view animals, with women more likely to support animal rights than men.[133][134] A 1996 study of adolescents by Linda Pifer suggested that factors that may partially explain this discrepancy include attitudes towards feminism and science, scientific literacy, and the presence of a greater emphasis on "nurturance or compassion" amongst women.[135]

A 2007 survey to examine whether or not people who believed in evolution were more likely to support animal rights than creationists and believers in intelligent design found that this was largely the case – according to the researchers, the respondents who were strong Christian fundamentalists and believers in creationism were less likely to advocate for animal rights than those who were less fundamentalist in their beliefs. The findings extended previous research, such as a 1992 study which found that 48% of animal rights activists were atheists or agnostic.[136][137]

Two surveys found that attitudes towards animal rights tactics, such as direct action, are very diverse within the animal rights communities. Near half (50% and 39% in two surveys) of activists do not support direct action. One survey concluded "it would be a mistake to portray animal rights activists as homogeneous."[133][138]

See also

- Animal cognition

- Animal consciousness

- Antinaturalism (politics)

- Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness

- Deep ecology

- Intrinsic value (animal ethics)

- Plant rights

- World Animal Day

Notes

- ^ Francione (2008), p. 1.

- ^ Beauchamp (2011b), p. 200.

- ^ Taylor (2009), pp. 8, 19–20; Rowlands (1998), p. 31ff.

- ^ Horta (2010).

- ^ That a central goal of animal rights is to eliminate the property status of animals, see Sunstein (2004), p. 11ff.

- For speciesism and fundamental protections, see Waldau (2011).

- For food, clothing, research subjects or entertainment, see Francione (1995), p. 17.

- ^ Singer (1975); Regan (1983), p. 243.

- For protectionism and abolitionism, see Francione and Garner (2010), pp. 1ff, 103ff, 175ff.

- ^ For animal law courses in North America, see "Animal law courses", Animal Legal Defense Fund, accessed July 12, 2012.

- For a discussion of animals and personhood, see Wise (2000), pp. 4, 59, 248ff; Wise (2004); Posner (2004); Wise (2007).

- For the arguments and counter-arguments about awarding personhood only to great apes, see Garner (2005), p. 22.