Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia: Difference between revisions

| (314 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Genocide by the Ustashe during WWII}} |

{{short description|Genocide by the Ustashe during WWII}} |

||

{{pp-protect|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2020}} |

|||

{{Infobox civilian attack |

{{Infobox civilian attack |

||

|partof = [[World War II in Yugoslavia]] |

|partof = [[World War II in Yugoslavia]] |

||

| Line 12: | Line 13: | ||

| image4 = Children in Sisak concentration camp.jpg |

| image4 = Children in Sisak concentration camp.jpg |

||

| alt4 = Sisak children's concentration camp |

| alt4 = Sisak children's concentration camp |

||

| image5 = |

| image5 = Prisilno pokrštavanje Srba u Slavoniji.jpg |

||

| alt5 = Forced mass baptism in Mikleuš |

|||

| alt5 = Ustasha with civilian prisoners after the Kozara offensive |

|||

| image6 = Alojzije Stepinac on trial.jpg |

|||

| image6 = Logor Gradina used by Croat Ustaše (спомен подручје Доња Градина, Република Српска).jpg |

|||

| alt6 = |

| alt6 = Aloysius Stepinac on trial |

||

| footer_align = center |

| footer_align = center |

||

| footer = (clockwise from top){{flatlist| |

| footer = (clockwise from top){{flatlist| |

||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

* [[Adolf Hitler]] meets [[Ante Pavelić]] |

* [[Adolf Hitler]] meets [[Ante Pavelić]] |

||

* [[Sisak children's concentration camp]] |

* [[Sisak children's concentration camp]] |

||

* [[Forced conversion|Forced mass baptism]] in [[Mikleuš]] |

|||

* Ustasha with with civilian prisoners after the [[Kozara Offensive]] |

|||

* [[Aloysius Stepinac]] on trial |

|||

* Memorial Center in [[Gradina Donja]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

|image_upright = |

|image_upright = |

||

|caption = |

|caption = |

||

|location = {{Unbulleted list|[[Independent State of Croatia]]|([[Axis-occupied Yugoslavia]])}} |

|location = {{Unbulleted list|[[Independent State of Croatia]]|([[World War II in Yugoslavia|Axis-occupied Yugoslavia]])}} |

||

|target = [[Serbs]] |

|target = [[Serbs]] |

||

|date = 1941–1945 |

|date = 1941–1945 |

||

| Line 35: | Line 36: | ||

* 217,000{{sfn|Goldstein|1999|p=158}} |

* 217,000{{sfn|Goldstein|1999|p=158}} |

||

* 300,000—350,000{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=114}}{{sfn|Baker|2015|p=18}}{{sfn|Bellamy|2013|p=96}}{{sfn|Pavlowitch|2008|p = 34}} |

* 300,000—350,000{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=114}}{{sfn|Baker|2015|p=18}}{{sfn|Bellamy|2013|p=96}}{{sfn|Pavlowitch|2008|p = 34}} |

||

* 200,000—500,000{{sfn|Yeomans| |

* 200,000—500,000{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p = 18}} |

||

|perps = [[Ustaše]] |

|perps = [[Ustaše]] |

||

|motive = [[Anti-Serb sentiment]],{{sfn|Christia|2012|p=206}} [[Greater Croatia]],{{sfn|Korb| |

|motive = [[Anti-Serb sentiment]],{{sfn|Christia|2012|p=206}} [[Greater Croatia]],{{sfn|Korb|2010a|p=512}} anti-[[Yugoslavism]],{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|p=5}} [[Croatisation]]{{sfn|Touval|2001|p=105}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Genocide of the Serbs''' ({{lang-sh|Genocid nad Srbima, Геноцид над Србима}}) was the [[World War II in Yugoslavia|World War II]] |

The '''Genocide of the Serbs''' ({{lang-sh|Genocid nad Srbima, Геноцид над Србима}}) was the systematic persecution of [[Serbs]] which was committed during [[World War II in Yugoslavia|World War II]] by the [[Fascism|fascist]] [[Ustaše]] regime in the [[Nazi German]] [[Client state|client]] [[Independent State of Croatia]] (NDH) between 1941 and 1945. It was carried out through executions in [[Concentration camps in the Independent State of Croatia|death camps]], as well as through [[mass murder]], [[ethnic cleansing]], [[deportation]]s, [[forced conversion]]s, and [[Wartime sexual violence|war rape]]. This genocide was simultaneously carried out with [[The Holocaust in the Independent State of Croatia|the Holocaust in the NDH]], by combining [[Racial policy of Nazi Germany|Nazi racial policies]] with the ultimate goal of creating an ethnically pure [[Greater Croatia]]. |

||

The ideological foundation of the Ustaše movement reaches back to the 19th century. Several [[Croatian nationalism|Croatian nationalists]] and intellectuals established theories about Serbs as an [[racism|inferior race]]. The [[World War I]] legacy, as well as the opposition of a group of nationalists to the [[Creation of Yugoslavia|unification]] into a common state of [[South Slavs]], influenced ethnic tensions in the newly formed [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia|Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes]] (since 1929 Kingdom of Yugoslavia). During the 1920s, [[Ante Pavelić]] became the leading advocate of Croatian independence. The [[6 January Dictatorship]] and the later [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia#6 January dictatorship|anti-Croat policies]] of the Serb-dominated Yugoslav government in the 1920s and 1930s fueled the rise of nationalist and far-right movements. This culminated in the rise of the Ustaše, an [[ultranationalist]], fascist and [[terrorism|terrorist]] organization, founded by Pavelić. The movement was financially and ideologically supported by [[Benito Mussolini]], and it was also involved in the assassination of King [[Alexander I of Yugoslavia|Alexander I]]. |

|||

Following the |

Following the [[Axis powers|Axis]] [[invasion of Yugoslavia]] in April 1941, a German [[puppet state]] known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established, comprising most of modern-day [[Croatia]] and [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] as well as parts of modern-day [[Serbia]] and [[Slovenia]], ruled by the Ustaše. The Ustaše's goal was to create an [[Monoethnicity|ethnically homogeneous]] Greater Croatia by eliminating all non-[[Croats]], with the Serbs being the primary target but [[Jews]], [[Romani people|Roma]] and political dissidents were also targeted for elimination. Large scale massacres were committed and concentration camps were built, the largest one was the [[Jasenovac concentration camp|Jasenovac]], which was notorious for its high mortality rate and the barbaric practices which occurred in it. Furthermore, the NDH was the only Axis [[puppet state]] to establish [[Children in the Holocaust|concentration camps specifically for children]]. The regime systematically murdered approximately 200,000 to 500,000 Serbs, with most authors agreeing on a range of around 300,000 to 350,000 fatalities.{{Disputed inline|date=June 2020}} 300,000 Serbs were further expelled and at least 200,000 more Serbs were forcibly converted, most of whom de-converted following the war. Proportional to the population, the NDH was one of the most lethal regimes in the 20th century. |

||

[[Mile Budak]] and other NDH high officials were [[Trial of Mile Budak|tried and convicted]] of [[war crimes]] by the [[Communist Party of Yugoslavia|communist authorities]]. Concentration camp [[Nazi concentration camp commandant|commandants]] such as [[Ljubo Miloš]] and [[Miroslav Filipović]] were captured and executed, while [[Aloysius Stepinac]] was found guilty of forced conversion. Many others [[Ratlines (World War II aftermath)|escaped]], including the supreme leader Ante Pavelić, most to [[Latin America]]. The genocide wasn’t properly examined in the aftermath of the war, because the [[Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|post-war Yugoslav government]] didn’t encourage independent scholars out of concern that ethnic tensions would destabilize the new communist regime. Nowadays, оn [[22 April]], Serbia marks the [[Public holidays in Serbia|public holiday]] dedicated to the victims of genocide and fascism, while Croatia holds an official commemoration at the Jasenovac Memorial Site. |

|||

The regime systematically murdered approximately 200,000 to 500,000 Serbs, with most authors agreeing on a range of around 300,000 to 350,000 fatalities. At least 52,000 perished at Jasenovac. 300,000 Serbs were further expelled and at least 200,000 were forcibly converted, most of whom de-converted following the war. |

|||

== |

== Historical background == |

||

<!--DON'T ADD EVENTS THAT ARE NOT DISCUSSED IN RELIABLE SOURCES AS A BACKGROUND TO GENOCIDE AND USTAŠE GENOCIDAL IDEOLOGY--> |

|||

=== Pre-War Period === |

|||

Many scholars claimed that the ideological foundation of the [[Ustaše]] movement, reaches back to the 19th century, when [[Ante Starčević]] established the [[Party of Rights]]<ref>{{harvnb|Jonassohn|Björnson|1998|p=281}}, {{harvnb|Carmichael|Maguire|2015|p=151}}, {{harvnb| Tomasevich|2001|p=347}}, {{harvnb| Mojzes|2011|p=54}}, {{harvnb|Kallis|2008|pp=130-132}}, {{harvnb|Suppan|2014|p=1005}} , {{harvnb| Fischer|2007|pp=207-208}}, {{harvnb|Bideleux|Jeffries|2007|p=187}}, {{harvnb|McCormick |2008}} </ref>, as well as when [[Josip Frank]] seceded his extreme fraction from it and formed his own the Pure Party of Rights.<ref>{{harvnb| Tomasevich|2001|pp=347, 404}},{{harvnb|Yeomans |2015|pp=265-266}}, {{harvnb|Kallis|2008|pp=130-132}},{{harvnb| Fischer|2007|pp=207-208}}, {{harvnb|Bideleux|Jeffries|2007|p=187}}, {{harvnb|McCormick |2008}}, {{harvnb|Newman|2017}}</ref> Starčević was a major ideological influence on the [[Croatian nationalism]] of the Ustaše,{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}}{{sfn|Jonassohn|Björnson |1998|p=281}} he was an advocate of Croatian unity and independence and was both anti-[[Habsburg]] and [[anti-Serb sentiment|anti-Serb]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}} He envisioned the creation of a [[Greater Croatia]] that would include territories inhabited by [[Bosniaks]], [[Serbs]], and [[Slovenes]], considering Bosniaks and Serbs to be [[Croats]] who had been converted to [[Islam]] and [[Eastern Orthodox Christianity]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}} Starčević called the Serbs an “unclean race”, a “nomadic people” and “a race of slaves, the most loathsome beasts”, while co-founder of his party, [[Eugen Kvaternik]], denied the existence of [[Serbs in Croatia]], seeing their political consciousness as a threat.{{sfn|Carmichael|2012|p=97}}{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=265}}{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|p=37}}{{sfn|McCormick|2008}} He was cited as “father of [[racism]]”, while some Ustaše ideologues have linked Starčević's racial ideas to [[Adolf Hitler]]'s [[Racial policy of Nazi Germany|racial ideology]].{{sfn|Kenrick|2006|p=92}}{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|p=123}} |

|||

Ethnic tensions between [[Croats]] and [[Serbs]] can be traced back to the [[Great Schism of 1054]]. During the time of the [[Austrian Empire]], land privileges were granted to Serbs living in the [[Military Frontier]] of the Habsburg Monarchy.{{sfn|Mojzes|2008|p=158}} As Habsburg frontier militiamen, they were exempt from communal and church autonomy as well as feudal obligations while Croats were not. Historian Carl Brown notes that this became a source of Croat resentment and Serb determination to defend their status which became articulated in nationalist sentiments and ideologies in later history. However, both Croat and Serb communities lived in peace, if not harmony until 1941.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Brown |first1=L. Carl |title=Imperial Legacy: The Ottoman Imprint on the Balkans and the Middle East |date=1996 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-2311-0305-3 |page=85 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NxTLJpDWev4C&pg=PA85}}</ref> A politically provoking moment came with Serbian minister [[Ilija Garašanin]]'s ''[[Načertanije]]'' foreign policy programme (1844), a document that went unpublished until 1906.{{sfn|Trencsényi|Kopecek|2007|p=238–243}} The plan controversially proposed the unification of lands inhabited by Bulgarians, Macedonians, Albanians, Montenegrins, Bosnians, and Croats under a Serbian dynasty.{{sfn|Trencsényi|Kopecek|2007|p=238–243}} Garašanin's plan also included methods of spreading Serbian influence in claimed lands and onto Croats, who Garašanin regarded as "Serbs of Catholic faith"<ref name=cohen>{{cite book |last1=Cohen |first1=Philip J. |title=Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History |url=https://archive.org/details/serbiassecretwar0000cohe |url-access=registration |publisher=[[Texas A&M University Press]] |year=1996 |isbn=0-89096-760-1}}</ref>{{Rp|3}}, writing: "Special attention must be paid to diverting peoples of the Roman Catholic faith from Austria and her influence, and their greater inclination towards Serbia should be fostered."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bataković |first1=Dušan T. |title=The Foreign Policy of Serbia (1844-1867): IIija Garašanin's Načertanije |date=2014 |publisher=Balkanološki institut SANU |isbn=978-8-6717-9089-5 |page=256 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y5yxDwAAQBAJ}}</ref> The document is one of the most contested of nineteenth-century Serbian history, with rival interpretations.{{sfn|Trencsényi|Kopecek|2007|p=238–243}} |

|||

{{Genocide}} |

|||

Frank’s party embraced Starčević’s position that Serbs are an obstacle to Croatian political and territorial ambitions, and then the aggressive anti-Serb attitudes became one of the main characteristics of the party.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=167}}{{sfn|Kallis|2008|pp=130-132}}{{sfn|McCormick |2008}}{{sfn|Newman|2017}} The followers of the ultranationalist Pure Party of Right were known as the Frankists (''Frankovci'') and they would become the main pool of members of the subsequent Ustaše movement.{{sfn|Kallis|2008|p=130}}{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=265}}{{sfn|McCormick|2008}}{{sfn|Newman|2017}} Following the defeat of the [[Central Powers]] in [[World War I]] and the collapse of [[Austria-Hungary| Austria-Hungarian Empire]], the [[State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs|provisional state]] which was formed on the southern territories of the Empire which joined the [[Allies of World War I|Allies]]-associate [[Kingdom of Serbia]] to form the [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia|Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes]] (later known as Yugoslavia), ruled by the Serbian [[Karađorđević dynasty]]. Historian John Paul Newman explained the influence of the Frankists, as well as the legacy of the World War I on the Ustaše ideology and later genocidal means.{{sfn|Newman|2017}}{{sfn|Newman|2014}} Many war veterans had fought at various ranks and on various fronts on both the ‘[[Allies of World War I|victorious]]’ and ‘[[Central Powers|defeated]]’ sides of the war.{{sfn|Newman|2017}} Serbia suffered [[World War I casualties|the biggest casualty rate]] in the whole world, while Croats fought in the Austro-Hungarian army and two of them served as military governor of [[Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia]] and [[Imperial and Royal Military Administration in Serbia|occupied Serbia]].{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=310, 314}}{{sfn|Newman|2014}} They both endorsed Austria–Hungary’s denationalizing plans in Serb-populated lands and supported the idea of incorporating a tamed Serbia into Empire.{{sfn|Newman|2014}} Newman stated that Austro-Hungarian officers' “unfaltering opposition to Yugoslavia provided a blueprint for the Croatian radical right, the Ustaše”.{{sfn|Newman|2014}} The Frankists blamed [[Serbian nationalism|Serbian nationalists]] for the defeat of Austria-Hungary and opposed the creation of Yugoslavia, which was identified by them as a cover for [[Greater Serbia]].{{sfn|Newman|2017}} Мass Croatian national consciousness appeared after the establishment of a common state of South Slavs and it was directed against the new Kingdom, more precisely against Serbian predominance within it.{{sfn|Ognyanova|2000|p=3}} |

|||

A major ideological influence on the Croatian nationalism of the Ustaše was the 19th-century nationalist [[Ante Starčević]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}}<ref name="JonassohnBjörnson1998">{{cite book|author1=Kurt Jonassohn|author2=Karin Solveig Björnson|title=Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jIxCUXI38zcC&pg=PA281|accessdate=30 August 2013|date=January 1998|publisher=Transaction Publishers|isbn=978-1-4128-2445-3|page=281}}</ref> Starčević was an advocate of Croatian unity and independence and was both anti-[[Habsburg]] and [[Anti-Serb sentiment|anti-Serb]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}} He envisioned the creation of a [[Greater Croatia]] that would include territories inhabited by [[Bosniaks]], [[Serbs]], and [[Slovenes]], considering Bosniaks and Serbs to be Croats who had been converted to [[Islam]] and [[Eastern Orthodox Christianity]] and considering the [[Slovenia|Slovenes]] to be "mountain Croats".{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}} The [[Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina]] in 1878 probably contributed to the development of Starčević's anti-Serb sentiment: He believed that it increased chances for the creation of Greater Croatia. <ref>{{cite book|last=Carmichael|first=Cathie|title=Ethnic Cleansing in the Balkans: Nationalism and the Destruction of Tradition|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ybORI4KWwdIC&pg=PT96|accessdate=31 August 2013|year=2012|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-47953-5|p=95}}</ref> Starčević argued that the large Serb presence in the territories that were claimed by a Greater Croatia was the result of recent settlement, which had been encouraged by the Habsburg rulers, along with the influx of groups like [[Vlachs]] who took up Eastern Orthodox Christianity and identified themselves as Serbs.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|pp=207–208}}In 1902 major anti-Serb riots in Croatia were caused by reprinted article written by Serb Nikola Stojanović that was published in the publication of the Serbian Independent Party from [[Zagreb]] titled ''Do istrage vaše ili naše'' (''Till the Annihilation, yours or ours'') in which denying of the existence of Croat nation as well as forecasting the result of the "inevitable" Serbian-Croatian conflict occurred. |

|||

{{quote|That combat has to be led till the destruction, either ours or yours. One side must succumb. That side will be Croatians, due to their minority, geographical position, mingling with Serbs and because the process of evolution means Serbhood is equal to progress.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bilandžić|first=Dušan|title=Hrvatska moderna povijest|publisher=Golden marketing |year=1999|page=31|isbn=953-6168-50-2}}</ref>|Nikola Stojanović, ''Srbobran'', 10 August 1902.}} |

|||

Early 20th century Croatian intellectuals [[Ivo Pilar]], [[Ćiro Truhelka]] and [[Milan Šufflay]] influenced the Ustaše concept of nation and racial identity, as well as the theory of Serbs as an inferior race.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=7}}{{sfn|Kallis|2008|pp=130-131}}{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|p=124}} Pilar, historian, politician and lawyer, placed great emphasis on [[scientific racism|racial determinism]] arguing that Croats had been defined by the “[[Nordic race|Nordic]]-[[ Aryan race|Aryan]]” racial and cultural heritage, while Serbs had "interbred" with the "Balkan-Romanic [[Vlachs]]”.{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|pp=56-60}} Truhelka, archeologist and historian, claimed that Bosnian Muslims were ethnic Croats, who, according to him, belonged to the [[Master race|racially superior]] Nordic race. On the other hand, Serbs belonged to the “[[Degeneration theory|degenerate race]]” of the Vlachs.{{sfn|Bartulin|2013|pp=52-53}}{{sfn|Kallis|2008|pp=130-131}} The Ustaše promoted the theories of historian and politician Šufflay, who is believed to have claimed that Croatia had been "one of the strongest ramparts of Western civilization for many centuries", which he claimed had been lost through its union with Serbia when the nation of Yugoslavia was formed in 1918.{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=118}} |

|||

=== Inter-war period === |

|||

Following the defeat of the [[Central Powers]] in [[World War I]] and the collapse of [[Austria-Hungary]], the Croat and [[Slovenes|Slovene]]-dominated [[State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs]] was established. This new state failed to gain recognition from the [[Great Powers]]. In a note of 31 October, the National Council in Zagreb informed the governments of the [[United Kingdom]], [[French Third Republic|France]], [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]] and the [[United States]] that the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was constituted in the South-Slavic areas that had been part of Austria-Hungary, and that the new state intended to form a common state with Serbia and Montenegro. The same note was sent to the government of the [[Allies of World War I|Allies]]-associate [[Kingdom of Serbia]] and the Yugoslav Committee in London. Serbia's prime minister [[Nikola Pašić]] responded to the note on 8 November, recognizing the National Council in Zagreb as "legal government of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes living in the territory of the Austria-Hungary", and notified the governments of the United Kingdom, France, Italy and the United States asking them to do the same.{{sfn|Boban|1993}} |

|||

The outburst of Croatian nationalism after 1918 was one of the one of the main threats for Yugoslavia’s stability.{{sfn|Ognyanova |2000|p=3}} During the 1920s, [[Ante Pavelić]], lawyer, politician and one of the Frankists, became the leading advocate of Croatian independence.{{sfn|McCormick |2008}} In 1927, he secretly contacted [[Benito Mussolini]], dictator of [[Italy]] and founder of [[fascism]], and presented his [[separatism|separatist]] ideas to him.{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=39, 592}} Pavelić proposed an independent Greater Croatia that should cover the entire historical and ethnic area of the Croats.{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=39, 592}} In that period, Mussolini was interested in Balkans with the aim of isolating Yugoslavia, by strengthening Italian influence on the east coast of the [[Adriatic Sea]].{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=591}} British historian [[Rory Yeomans]] claimed that there are indication that Pavelić had been considering the formation of some kind of nationalist insurgency group as early as 1928.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=6}} |

|||

On 23–24 November, the National Council declared "unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs formed on the entire, contiguous South-Slavic area of the former Austria-Hungary with the Kingdom of Serbia and Montenegro into a unified State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs". 28 members of the council were appointed to implement that decision based on National Council's adopted directions on implementation of the agreement of organization of the unified state with the government of the Kingdom of Serbia and representatives of political parties in Serbia and Montenegro. The instructions were largely ignored by the delegation members who negotiated with [[Alexander I of Yugoslavia|Regent Alexander]] instead.{{sfn|Boban|1993}} The agreement with Serbia would save Croatia from being partitioned by the Allies as part of vanquished Austria-Hungary, the declaration did not specify the form of government and relations between ethnic groups.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Croatia/From-World-War-I-to-the-establishment-of-the-Kingdom-of-Serbs-Croats-and-Slovenes|title=Croatia|work=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|accessdate=25 April 2020}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Ante Pavelić StAF W 134 Nr. 026020 Bild 1 (5-92156-1).jpg|thumb|220px|left|[[Ante Pavelić]], one of the ''[[Josip Frank|Frankists]]'' and the leading advocate of Croatian independence in interwar Yugoslavia, founded the [[Ustaše]] movement]] |

|||

In June 1928, [[Stjepan Radić]], the leader of the largest and most popular Croatian party [[Croatian Peasant Party]] ({{lang|sh|Hrvatska seljačka stranka}}, HSS) was mortally wounded in the [[Parliament of Yugoslavia|parliamentary chamber]] by [[Puniša Račić]], a [[Montenegrin Serb]] leader, former [[Chetnik]] member and deputy of the ruling Serb [[People's Radical Party]]. Račić also shot two other HSS deputies dead and wounded two more.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=300}}{{sfn|Newman|2017}}{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=586}}{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=404}} The killings provoked violent student protests in [[Zagreb]].{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=300}} Trying to suppress the conflict between Croatian and Serbian political parties, King [[Alexander I of Yugoslavia|Alexander I]] proclaimed a [[6 January Dictatorship|dictatorship]] with the aim of establishing the “integral [[Yugoslavism]]” and single [[Yugoslavs|Yugoslav nation]].{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=150, 300}}{{sfn|Kallis|2008|p=130}}{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=573, 588-590}}<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ustaša|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ustasa|encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|accessdate=7 May 2020}}</ref> The introduction of the royal dictatorship brought separatist forces to the fore, especially among the Croats and [[Macedonians (ethnic group)|Macedonians]].{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=590}}{{sfn|Ognyanova|2000|p=3}} The ''Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionary Movement'' ({{lang-hr|Ustaša – Hrvatski revolucionarni pokret}}) emerged as the most extreme movement of these.{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=8}} The Ustaše was created in late 1929 or early 1930 among radical and militant student and youth groups, which existed from the late 1920s.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=300}} Precisely, the movement was founded by journalist [[Gustav Perčec]] and Ante Pavelić.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=300}} They were driven by a deep hatred of Serbs and Serbdom and claimed that, "Croats and Serbs were separated by an unbridgeable cultural gulf" which prevented them from ever living alongside each other.{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=118}} Pavelić accused the Belgrade government of propagating “a barbarian culture and [[Names of the Romani people|Gypsy]] civilization”, claiming they were spreading “[[atheism]] and bestial mentality in divine Croatia”.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=150}} Supporters of the Ustaše planned genocide years before World War II, for example one of Pavelić's main ideologues, [[Mijo Babić]], wrote in 1932 that the Ustaše "will cleanse and cut whatever is rotten from the healthy body of the Croatian people".{{sfn|Mojzes|2011|pp=52-53}} In 1933, the Ustaše presented "The Seventeen Principles" that formed the official ideology of the movement. The Principles stated the uniqueness of the Croatian nation, promoted collective rights over individual rights and declared that people who were not Croat by "[[Heredity|blood]]" would be excluded from political life.{{sfn|Levy|2009}}{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=208}} |

|||

This left Croats and Slovenes no choice but to join a union largely dominated by ethnic Serbs, which came to be known as the [[Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes]]. Upon its creation, the state was composed of six million Serbs, 3.5 million Croats and 1 million Slovenes. Being the largest ethnic group, the Serbs favoured a centralised state, whereas Croats, Slovenes and [[Bosnian Muslims]] did not.{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=6}} |

|||

In order to explain and justify “terror machine”, what they regularly referred to as “some excesses” by individuals, the Ustaše cited, among other things, policies of inter-was Yugoslav government which they described as Serbian [[hegemony]] “that cost the lives of thousand Croats”.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|pp=402-404}} Historian [[Jozo Tomasevich]] explains that that argument is not true, claiming that between December 1918 and April 1941 about 280 Croats were killed for political reason, and that no specific motive for the killings could be identified, as they may also be linked to clashes during the agrarian reform.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=403}} Moreover, he stated that Serbs too were denied civil and political rights during royal dictatorship.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=404}} However, Tomasevich explains that the anti-Croatian policies of the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav government in the 1920s and 1930s, as well as, the shooting of the HSS deputies by Radić were largely responsible for the creation, growth and nature of Croatian nationalist forces.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=404}} This culminated in the Ustaše movement and ultimately its anti-Serbian policies in the World War II, which was totally out of proportions to earlier anti-Croatian measures, in a nature and extent.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=404}} Historian Rory Yeomans explains that Ustaše officials constantly emphasized crimes against Croats by the Yugoslav government and security forces, although many of them were imagined, though some of them real, as justification for the their envisioned eradication of the Serbs.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=16}} Political scientist Tamara Pavasović Trošt, commenting on historiography and textbooks, listed the claims that terror against Serbs arose as a result of “their previous hegemony” as an example of the [[Historical negationism|relativisation]] of Ustaše crimes.{{sfn|Pavasović Trošt|2018}} Historian [[Aristotle Kallis]] explained that anti-Serb prejudices were a "chimera" which emerged through living together in Yugoslavia with continuity with previous stereotypes.{{sfn|Kallis|2008|p=130}} |

|||

Approved on 28 June 1921 and based on the Serbian constitution of 1903, the so-called [[Vidovdan Constitution]] established the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a [[parliamentary monarchy]] under the Serbian [[Karađorđević dynasty]]. [[Belgrade]] was chosen as the capital of the new state, assuring Serb and [[Orthodox Christian]] political dominance.{{sfn|Rogel|2004|pp=6–7}} In 1928, [[Croatian Peasant Party]] leader [[Stjepan Radić]] was assassinated on the floor of the [[Parliament of Yugoslavia|country's parliament]] by a [[Montenegrin Serb]] leader and [[People's Radical Party]] politician [[Puniša Račić]], who attended parliamentary sessions armed. In the [[Legislative Assembly|Assembly]], Račić, got up and made a provocative speech which produced a stormy reaction from the opposition but Radić himself stayed completely silent. Finally, [[Ivan Pernar (politician, born 1889)|Ivan Pernar]] shouted in response, "''thou plundered [[bey]]s''" (referring to accusations of corruption related to Račić). Račić had demanded that Pernar be sanctioned, and when the demand was not met, Račić drew his pistol and fired at Croatian Peasant Party deputies, killing two instantly and wounding three more. Radić refused to apologize earlier where in a speech he accused Račić of corruption and using the cover of his Chetnik activities to steal from civilian population.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Newman|first=John Paul|date=2017|title=War Veterans, Fascism, and Para-Fascist Departures in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1918–1941|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318166421_War_Veterans_Fascism_and_Para-Fascist_Departures_in_the_Kingdom_of_Yugoslavia_1918-1941|journal=FASCISM|volume=6|pages=63|via=}}</ref> Radić’s burial was massively attended and his death was seen as causing a permanent rift in Croat-Serb relations in the old Yugoslavia.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.yuhistorija.com/serbian/jug_prva_txt01c3.html|title=YU Historija... ::: Dobro dosli ... Prva Jugoslavija|website=www.yuhistorija.com|access-date=2020-03-20}}</ref> |

|||

The Ustaše functioned as a [[terrorist organization]] as well.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=32}} The first Ustaše center was established in [[Vienna]], where brisk anti-Yugoslav propaganda soon developed and agents were prepared for terrorist actions.{{sfn|Suppan|2014|p=592}} They organized the so-called [[Velebit uprising]] in 1932, assaulting a police station in the village of Brušani in [[Lika]].{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=301}} In 1934, the Ustaše cooperated with Bulgarian, Hungarian and Italian right-wing extremists to assassinate King Alexander while he visited the French city of [[Marseille]].{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=8}} Pavelić's fascist tendencies were apparent.{{sfn|McCormick|2008}} The Ustaše movement was financially and ideologically supported by Benito Mussolini.<ref>{{harvnb|Kallis|2008|pp=130}}, {{ harvnb |Yeomans|2015|p=263}}, {{harvnb|Suppan|2014|p=591}}, {{harvnb|Levy|2009}}, {{harvnb| Domenico|Hanley |2006|p=435}}, {{harvnb|Adeli|2009|p=9}} </ref> During the intensification of ties with [[Nazi Germany]] in the 1930s, Pavelić's concept of the Croatian nation became increasingly race-oriented.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=150}}{{sfn|Kallis|2008|p=134}}{{sfn|Payne|2006}} |

|||

The following year, King Alexander I proclaimed the [[6 January Dictatorship]] and renamed his country the [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia]] to remove any emphasis on its ethnic makeup. Yugoslavia was divided into nine administrative units called [[Subdivisions of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia|''banovinas'']], six of which had ethnic Serb majorities. |

|||

== Independent State of Croatia == |

|||

The anti-Croatian policies of the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav government in the 1920's and 1930's and the assassination of Croatian Peasant Party leaders in Parliament in June 1928 by a deputy of the main Serbian political party, were largely responsible for the creation, growth and nature of Croatian nationalist forces.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=404}} In 1931, the King issued a decree which allowed the Yugoslav Parliament to reconvene on the condition that only pro-Yugoslav parties were allowed to be represented in it. Marginalised, far-right and far-left movements thrived. The [[Ustaše]], a Croatian [[fascist]] party, emerged as the most extreme movement of these.{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=8}} The Ustaše were driven by a deep hatred of Serbs and [[Serbdom]] and claimed that, "Croats and Serbs were separated by an unbridgable cultural gulf" which prevented them from ever living alongside each other.{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=118}} They organized the so-called [[Velebit uprising]] in 1932, assaulting a police station in the village of Brušani in [[Lika]]. The police responded harshly to the assault and harassed the local population.{{sfn|Goldstein|1999|pp=125–126}} In 1934, the Ustaše cooperated with Bulgarian, Hungarian and Italian right-wing extremists to assassinate Alexander while he visited the French city of [[Marseille]].{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=8}} Alexander's cousin, [[Prince Paul of Yugoslavia|Prince Paul]], took the [[regency]] until the new king, [[Peter II of Yugoslavia|Peter II]], turned eighteen.{{sfn|Hoptner|1962|p=25}} Ustaše leader, [[Ante Pavelić]], believed that the assassination would cause Yugoslavia to disintegrate. Instead, countries that had assisted the organisation, such as [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]] and [[Kingdom of Hungary (1920–46)|Hungary]], cracked down on its members, arrested them, and destroyed their training camps at Yugoslavia's behest.{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=92}} According to historian [[Slavko Goldstein]], the Ustaše planned to commit a genocide against ethnic Serbs for years prior to the outbreak of [[World War II]]. |

|||

{{Multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 300 |

|||

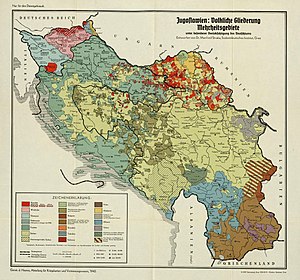

| image1 = Yugoslavia Ethnic 1940.jpg |

|||

| caption1 = Kingdom of Yugoslavia's ethnic map 1940<br>{{legend2|#ccce7c|[[Serbs]] <small>(incdluding [[Serbs of Montenegro|Montenegrin Serbs]])</small>}}<br>{{legend2|#98b294|[[Croats]]}}<br>{{legend2|#929453|[[Bosniaks|Bosnian Muslims]]}}<br>{{legend2|red|[[Germans]] ([[Danube Swabians]])}} |

|||

| image2 = Axis occupation of Yugoslavia 1941-43 legend.png |

|||

| caption2 = Occupation and partition of Yugoslavia after the [[Invasion of Yugoslavia|Axis invasion]] |

|||

}} |

|||

In April 1941, the [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia]] was [[Invasion of Yugoslavia|invaded]] by the Axis powers. After Nazi forces entered Zagreb on 10 April 1941, Pavelić's closest associate [[Slavko Kvaternik]], proclaimed the formation of the [[Independent State of Croatia]] (NDH) on a Radio Zagreb broadcast. Meanwhile, Pavelić and several hundred Ustaše volunteers left their camps in Italy and travelled to Zagreb, where Pavelić declared a new government on 16 April 1941.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=?}} He accorded himself the title of "[[Poglavnik]]" ({{Lang-de|Führer}}, {{Lang-eng|Chief leader}}). The NDH combined most of modern Croatia, all of modern [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and parts of modern [[Serbia]] into an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate".{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=272}} Serbs made up about 30% of the NDH population.{{sfn|Kallis|2008|p=239}} The NDH was never fully sovereign, but it was a [[puppet state]] that enjoyed the greatest autonomy than any other regime in [[German-occupied Europe]].{{sfn|Payne|2006}} The Independent State of Croatia was declared to be on Croatian "ethnic and historical territory".{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=466}} |

|||

{{quote|This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.|Milovan Žanić, the minister of the [[Government of the Independent State of Croatia|NDH government]], on 2 May 1941.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB159.pdf|title=Deciphering the Balkan Enigma: Using History to Inform Policy|accessdate=3 June 2011}}</ref>}} |

|||

One of Pavelić's main ideologues, [[Mijo Babić]], wrote in 1932: |

|||

The Ustaše became obsessed with creating an [[Monoethnicity|ethnically pure state]].{{sfn|Mojzes|2011|p=54}} As outlined by Ustaše ministers [[Mile Budak]], Mirko Puk and Milovan Žanić, the strategy to achieve an ethnically pure Croatia was that:<ref>Jones, Adam & Nicholas A. Robins. (2009), [https://books.google.com/books?id=AX3UCk_PdEwC&pg=PA106 ''Genocides by The Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide In Theory and Practice''], p. 106, Indiana University Press; {{ISBN|978-0-253-22077-6}}</ref>{{sfn|Jacobs|2009|p=158-159}} |

|||

{{quote|When blood starts to spill it will gush in streams. The blood of the enemy will turn into gushes and rivers, and bombs will scatter their bones like the wind scatters the husks of wheat. Every Ustaša is poised [...] to thrust himself upon the enemy, with his body and soul, to kill and destroy it. The dedication, revolvers, bombs, and sharp knives of the Croatian Ustaše will cleanse and cut whatever is rotten from the healthy body of the Croatian people.{{sfn|Mojzes|2011|pp=52–53}} }} |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be killed |

|||

Croatian opposition to a centralised Yugoslavia continued following Alexander's assassination, culminating with the signing of the [[Cvetković–Maček Agreement]] by Croatian politician [[Vladko Maček]] and Yugoslav Prime Minister [[Dragiša Cvetković]] on 26 August 1939. By signing the agreement, Belgrade sought to accommodate moderate Croats through the creation of a largely autonomous [[Banovina of Croatia]] which covered 27 percent of Yugoslavia's territory and included 29 percent of its population. It also ensured that Maček became Yugoslavia's deputy premier. Ultimately, the agreement was not successful—it led to other Yugoslav ethnic groups demanding a status similar to that of [[Croatia]] and failed to satisfy right-wing Croats such as those that had joined the Ustaše, who wanted a fully independent Croatian state.{{sfn|Rogel|2004|p=8}} The Ustaše were enraged by the very notion of Maček having negotiated with Belgrade, denouncing him as a "sell out". Right-wing Croats quickly orchestrated anti-Serbian incidents across the newly formed Banovina, and in June 1940, a Croatian National-Socialist Party was established in [[Zagreb]].{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=108}} On 25 March 1941, Yugoslavia bowed to German pressure and signed the [[Tripartite Pact]] in an effort to avoid war with the [[Axis powers]].{{sfn|Roberts|1973|pp=13–14}} The Ustashe movement functioned as a [[terrorist organization]] as well.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=32}}<ref name="kroatische">Ladislaus Hory und Martin Broszat. ''Der kroatische Ustascha-Staat'', Deutsche Verlag-Anstalt, Stuttgart, 2. Auflage 1965, pp. 13–38, 75–80. {{in lang|de}}<!-- ISBN/ISSN needed --></ref> |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be expelled |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be forcibly converted to [[Roman Catholicism|Catholicism]] |

|||

The Ustaše movement received limited support from ordinary Croats. {{sfn|Shepherd|2012|p=78}}{{sfn|Israeli|2013|p=45}} In May 1941, the Ustaše had about 100,000 members who took the oath.{{sfn|Goldstein|1999|p=134}}{{sfn|Weiss-Wendt|2010|p=148}} However, local support for Ustaše violence was larger than the number of members could suggest.{{sfn|Weiss-Wendt|2010|pp=148-149, 157}} Since [[Vladko Maček]] called on the supporters of the Croatian Peasant Party to respect and co-operate with the new regime of Ante Pavelić, he was able to use the apparatus of the party and most of the officials from the former [[Croatian Banovina]].{{sfn|Suppan|2014|pp=32, 1065}}{{sfn|Goldstein|1999|p=133}} Initially, Croatian soldiers who had previously served in the Austro-Hungarian army held the highest positions in the NDH armed forces.{{sfn| Tomasevich|2001|p=425}} |

|||

Two days later, a group of Serbian nationalist [[Royal Yugoslav Air Force]] officers organised a ''[[Yugoslav coup d'état|coup d'état]]'' to depose Prince Paul and the government of [[Dragiša Cvetković]].{{sfn|Tomasevich|1975|p=43}} Peter was declared to be of age and was elevated to the throne.{{sfn|Roberts|1973|p=14}} Upon hearing news of the coup, [[Adolf Hitler]] immediately ordered the [[invasion of Yugoslavia]].{{sfn|Roberts|1973|p=15}} |

|||

Historian Irina Ognyanova stated that the similarities between the NDH and the Third Reich included the assumption that terror and genocide were necessary for the preservation of the state.{{sfn|Ognyanova|2000|p=22}} [[Viktor Gutić]] made several speeches in early summer 1941, calling Serbs "former enemies" and "unwanted elements" to be cleansed and destroyed, and also threatened Croats who did not support their cause.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=17}} Much of the ideology of the Ustaše was based on Nazi racial theory. Like the Nazis, the Ustaše deemed Jews, Romani, and Slavs to be sub-humans (''[[Untermensch]]''). They endorsed the claims from German racial theorists that Croats were not Slavs but a Germanic race. Their genocides against Serbs, Jews, and Romani were thus expressions of [[Racial policy of Nazi Germany|Nazi racial ideology]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|pp=207–208, 210, 226}} [[Adolf Hitler]] supported Pavelić in order to punish the Serbs.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=212}} Historian [[Michael Phayer]] explained that the Nazis’ decision [[The Holocaust|to kill all of Europe's Jews]] is estimated by some to have begun in the latter half of 1941 in late June which, if correct, would mean that the genocide in Croatia began before the Nazi killing of Jews.{{sfn|Phayer|2000|p=31}} [[Jonathan Steinberg]] stated that the crimes against Serbs in the NDH were the “earliest total genocide to be attempted during the World War II”.{{sfn|Phayer|2000|p=31}} |

|||

=== Invasion of Yugoslavia === |

|||

[[File:Axis occupation of Yugoslavia 1941-43 legend.png|thumb|Occupation and partition of Yugoslavia after the Axis invasion]] |

|||

In April 1941, the [[Kingdom of Yugoslavia]] was [[Invasion of Yugoslavia|invaded]] by the Axis powers and the [[puppet state]] known as the [[Independent State of Croatia]] was created, ruled by the [[Ustaše]] regime. The ideology of the Ustaše movement was a blend of [[Nazism]],{{sfn|Hory|Broszat|1964|pp=13–38}} Catholicism,<ref name="NelisMorelli2015">{{cite book|author1=Jan Nelis|author2=Anne Morelli|author3=Danny Praet|title=Catholicism and Fascism in Europe 1918 – 1945: Edited by Jan Nelis, Anne Morelli and Danny Praet.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z41wCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA365|year=2015|publisher=Georg Olms Verlag|isbn=978-3-487-42127-8|pages=365–}}</ref> and [[Croatian nationalism|Croatian ultranationalism]]. The Ustaše supported the creation of a [[Greater Croatia]] that would span to the [[Drina|Drina river]] and the outskirts of [[Belgrade]].<ref>Viktor Meier. ''Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise'' English edition. London, UK: Routledge, 1999, p. 125.<!-- ISBN needed --></ref> The movement emphasized the need for a racially "pure" Croatia and promoted the extermination of [[Serbs]] (who were viewed as ethinic foreigners,<ref name="Yeomans2013">{{cite book|author=Rory Yeomans|title=Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941–1945|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Yxv4-iqVe2wC&pg=PA52|date=April 2013|publisher=University of Pittsburgh Pre|isbn=978-0-8229-7793-3|pages=52–}}</ref>) [[Jews]],{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|pp=351–52}} and [[Romani people|Gypsies]].{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=207}} |

|||

[[Andrija Artuković]], the Minister of Interior of the Independent State of Croatia, signed into law a number of racial laws.{{sfn|Barbier|2017|p=169}} On 30 April 1941, the government adopted “the legal order of races” and “the legal order of the protection of Atyan blood and the honor of Croatian people”.{{sfn|Barbier|2017|p=169}} Croats and about 750,000 Bosnian Muslims, whose support was needed against the Serbs, were proclaimed Aryans.{{sfn|Kenrick|2006|p=92}} [[Donald Bloxham]] and [[Robert Gerwarth]] concluded that Serbs were primary target of racial laws and murders.{{sfn|Bloxham|Gerwarth|2011|p=111}} The Ustaše introduced the laws to strip Serbs of their citizenship, livelihoods, and possessions.{{sfn|Levy|2009}} Similar to Jews in the Third Reich, Serbs were forced to wear armbands bearing the letter “P”, for ''Pravoslavac '' (Orthodox).{{sfn|Levy|2009}}{{sfn|McCormick|2008}} Ustaše writers adopted [[Dehumanization|dehumanizing]] rhetoric. {{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=132}}{{sfn|Israeli|2013|p=51}} In 1941, the usage of the [[Cyrillic script]] was banned,{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=312}} and in June 1941 began the elimination of "Eastern" (Serbian) words from the Croatian language, as well as the shutting down of Serbian schools.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=61}} Ante Pavelić ordered, through the "Croatian state office for language", the creation of new words from old roots (some which are used today), and purged many Serbian words.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=228}} |

|||

The Ustaše used Starčević's theories to promote the annexation of [[Bosnia (region)|Bosnia]] and [[Herzegovina]] to Croatia and they recognized Croatia as having two major ethnocultural components: Catholic Croats and Muslim Croats,<ref name="BJ">Butić-Jelić, Fikreta. ''Ustaše i Nezavisna Država Hrvatska 1941–1945''. Liber, 1977.<!-- ISSN/ISBN needed --></ref> because the Ustaše saw the Islam of the Bosnian-Muslims as a religion which "keeps true the blood of Croats."<ref name="BJ"/> Armed struggle, genocide and terrorism were glorified by the group.{{sfn|Djilas|1991|p=114}} Alexander Korb wrote: |

|||

{{quote2|A German-Croatian agreement enabled Ustaša militias and Croatian state agents to unleash a campaign [[ethnic cleansing]] directed against the Serbs who lived on the soil the Ustaša claimed was part of [[Greater Croatia]]{{sfn|Korb|2010b|p=512}}}} |

|||

== Concentration and extermination camps == |

|||

== Independent State of Croatia == |

|||

{{See also| |

{{See also|Jasenovac concentration camp|Concentration camps in the Independent State of Croatia}} |

||

[[File:Head of Serbian orthodox priest and Croatian soldiers.jpg|thumb|right|Head of [[Serbian Orthodox]] priest and Ustaše]] |

|||

{{Genocide}} |

|||

The Ustaše set up temporary concentration camps in the spring of 1941 and laid the groundwork for a network of permanent camps in autumn.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=18}} The creation of concentration camps and extermination campaign of Serbs had been planned by the Ustaše leadership long before 1941.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=16}} In Ustaše state exhibits in Zagreb, the camps were portrayed as productive and "peaceful work camps", with photographs of smiling inmates.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=2}} |

|||

After Nazi forces entered Zagreb on 10 April 1941, Pavelić's closest associate [[Slavko Kvaternik]], proclaimed the formation of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) on a Radio Zagreb broadcast. Meanwhile, Pavelić and several hundred Ustaše volunteers left their camps in Italy and travelled to Zagreb, where Pavelić declared a new government on 16 April 1941.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=?}} He accorded himself the title of "[[Poglavnik]]" ({{Lang-de|Führer}}, {{Lang-eng|Chief leader}}). The Independent State of Croatia was declared to be on Croatian "ethnic and historical territory".{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=466}} |

|||

Serbs, Jews and Romani were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as [[Jasenovac concentration camp|Jasenovac]], [[Stara Gradiška concentration camp|Stara Gradiška]], [[Gospić concentration camp|Gospić]] and [[Jadovno concentration camp|Jadovno]]. There were 22–26 camps in NDH in total.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=69}} Historian [[Jozo Tomasevich]] described that the Jadovno concentration camp itself acted as a "way station" en route to pits located on Mount [[Velebit]], where inmates were executed and dumped.{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=726}} |

|||

{{quote|This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.|Milovan Žanić, the minister of the NDH Legislative council, on 2 May 1941.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB159.pdf|title=Deciphering the Balkan Enigma: Using History to Inform Policy|accessdate=3 June 2011}}</ref>}} |

|||

The largest and most notorious camp was the Jasenovac-Stara Gradiška complex,{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=18}} the largest extermination camp in the Balkans.<ref>{{harvnb|Yeomans|2015|p=21}}, {{harvnb|Pavlowitch|2008|p=34}}</ref> An estimated 100,000 inmates perished there, most Serbs.<ref name="Yeomans 2015 3">{{harvnb|Yeomans|2015|p=3}}, {{harvnb|Pavlowitch|2008|p=34}}</ref> Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, the commander-in-chief of all the Croatian camps, announced the great "efficiency" of the Jasenovac camp at a ceremony on 9 October 1942, and also boasted: "We have slaughtered here at Jasenovac more people than the Ottoman Empire was able to do during its occupation of Europe."{{sfn|Paris|1961|p=132}} |

|||

As outlined by Ustaše ministers [[Mile Budak]], Mirko Puk and Milovan Žanić, the strategy to achieve an ethnically pure Croatia was that:<ref>Jones, Adam & Nicholas A. Robins. (2009), [https://books.google.com/books?id=AX3UCk_PdEwC&pg=PA106 ''Genocides by The Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide In Theory and Practice''], p. 106, Indiana University Press; {{ISBN|978-0-253-22077-6}}</ref><ref name="jacobs">Jacobs, Steven L. [https://books.google.com/books?id=zm5YHFnQaWIC&pg=PA15 ''Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam''], pp. 158–59, Lexington Books, 2009; {{ISBN|978-0-739-13590-7}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Srbosjek (knife) used in Croatia - 1941–1945.jpg|thumb|left|The ''[[Srbosjek]]'' ("Serb cutter"), an agricultural knife worn over the hand that was used by the Ustaše for the quick slaughter of inmates.]] |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be killed |

|||

Bounded by rivers and two barbed-wire fences making escape unlikely, the Jasenovac camp was divided into five camps, the first two closed in December 1941, while the rest were active until the end of the war. Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) held women and children. The Ciglana (brickyards, Jasenovac III) camp, the main killing ground and essentially a death camp, had 88% mortality rate, higher than [[Auschwitz]]'s 84.6%.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=70}} A former brickyard, a furnace was engineered into a crematorium, with witness testimony of some, including children, being [[Death by burning|burnt alive]] and stench of human flesh spreading in the camp.{{sfn|Levy|2011|pp=70–71}} Luburić had a gas chamber built at Jasenovac V, where a considerable number of inmates were killed during a three-month experiment with [[sulfur dioxide]] and [[Zyklon B]], but this method was abandoned due to poor construction.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Still, that method was unnecessary, as most inmates perished from starvation, disease (especially [[typhus]]), assaults with mallets, maces, axes, poison and knives.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} The ''srbosjek'' ("Serb-cutter") was a glove with an attached curved blade designed to cut throats.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Large groups of people were regularly executed upon arrival outside camps and thrown into the river.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Unlike German-run camps, Jasenovac specialized in brutal one-on-one violence, such as guards attacking barracks with weapons and throwing the bodies in the trenches.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Some historians use a sentence from German sources: “Even German officers and [[Schutzstaffel|SS]] men lost their cool when they saw (Ustaše) ways and methods.”{{sfn|Weiss Wendt|2010|p=147}} |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be expelled |

|||

# One-third of the Serbs were to be forcibly converted to [[Roman Catholicism|Catholicism]] |

|||

The infamous camp commander [[Miroslav Filipović|Filipović]], dubbed ''fra Sotona'' ("brother Satan") and the "personification of evil", on one occasion drowned Serb women and children by flooding a cellar.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Filipović and other camp commanders (such as [[Dinko Šakić]] and his wife Nada Šakić, the sister of Maks Luburić), used ingenious torture.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} There were throat-cutting contests of Serbs, in which prison guards made bets among themselves as to who could slaughter the most inmates. It was reported that guard and former Franciscan priest [[Petar Brzica]] won a contest on 29 August 1942 after cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.{{sfn|Lituchy|2006|p=117}} Inmates were tied and hit over the head with mallets and half-alive hung in groups by the Granik ramp crane, their intestines and necks slashed, then dropped into the river.{{sfn|Bulajić|2002|p=231}} When the Partisans and Allies closed in at the end of the war, the Ustaše began mass liquidations at Jasenovac, marching women and children to death, and shooting most of the remaining male inmates, then torched buildings and documents before fleeing.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=72}} Many prisoners were victims of [[Wartime sexual violence|rape]], [[Genital modification and mutilation|sexual mutilation]] and [[disembowelment]], while induced [[Human cannibalism|cannibalism]] amongst the inmates also took place.{{sfn|Schindley|Makara|2005|p=149}}{{sfn|Jacobs|2009|p=160}}{{sfn|Byford|2014}}{{sfn|Lituchy|2006|p=220}}<ref name=Simon_Wiesenthal>{{cite web|url=http://www.museumoftolerance.com/education/archives-and-reference-library/online-resources/simon-wiesenthal-center-annual-volume-4/annual-4-chapter-2.html|title=The Extradition of Nazi Criminals: Ryan, Artukovic, and Demjanjuk|work=[[Simon Wiesenthal Center]]|accessdate=10 May 2020}}</ref> Some survivors testified about [[Hematophagy#Human hematophagy|drinking blood]] from the slashed throats of the victims and [[Soap made from human corpses|soap making from human corpses]].{{sfn|Schindley|Makara|2005|p=42, 393}}{{sfn|Byford|2014}}<ref name=Simon_Wiesenthal/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dzambas.ch/dzblog/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Jasenovac_-_Survivor_testimonies.pdf|title=Survivor Testimonies|work=[[Kingsborough Community College]]|accessdate=10 May 2020}}</ref> |

|||

The NDH combined most of modern Croatia, all of modern [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and parts of modern [[Serbia]] into an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate".{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|p=272}} NDH authorities, led by the [[Ustaše militia]],{{sfn|Tomasevich|2001|pp=397–409}} then implemented genocidal policies against the [[Serb]], [[Jewish]] and [[Romani people|Romani]] populations living in the new state. |

|||

[[File:Grobnica djece sa Kozare Mirogoj.jpg|thumb|Monument at the [[Mirogoj Cemetery]] in [[Zagreb]] dedicated to the children from [[Kozara]] who died in Ustaše concentration camps]] |

|||

[[Viktor Gutić]] made several speeches in early summer 1941, calling Serbs "former enemies" and "unwanted elements" to be cleansed and destroyed, and also threatened Croats who did not support their cause.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=17}} Much of the ideology of the Ustaše was based on Nazi racial theory. Like the Nazis, the Ustaše deemed Jews, Romani, and Slavs to be sub-humans ([[Untermensch]]). They endorsed the claims from German racial theorists that Croats were not Slavs but a Germanic race. Their genocides against Serbs, Jews, and Romani were thus expressions of Nazi racial ideology.<ref name="fischer">{{cite book|editor-last=Fischer|editor-first=Bernd J.|editor-link=Bernd Jürgen Fischer|year=2007|title=Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of South-Eastern Europe|publisher=Purdue University Press|isbn=978-1-55753-455-2|ref=harv|pages=207–208, 210, 226}}</ref> |

|||

=== Children's concentration camps === |

|||

In 1941, the usage of the [[Cyrillic script]] was banned,{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=312}} and in June 1941 began the elimination of "Eastern" (Serbian) words from the Croatian language, as well as the shutting down of Serbian schools.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=61}} Ante Pavelić ordered, through the "Croatian state office for language", the creation of new words from old roots (some which are used today), and purged many Serbian words.{{sfn|Fischer|2007|p=228}} |

|||

{{See also|Children in the Holocaust}} |

|||

The Independent State of Croatia was the only Axis satellite to have erected camps specifically for children.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=18}} Special camps for children were those at [[Sisak children's concentration camp|Sisak]], [[Đakovo internment camp|Đakovo]] and [[Jastrebarsko concentration camp|Jastrebarsko]],{{sfn|Bulajić|2002|p=7}} while Stara Gradiška held thousands of children and women.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=70}} Historian Tomislav Dulić explained that the systematic murder of infants and children, who could not pose a threat to the state, serves as one of the important illustration of the genocidal character of Ustaša mass killing.{{sfn|Dulić|2006}} |

|||

The Holocaust and genocide survivors, including [[Božo Švarc]], testified that Ustaše tore off the children's hands, as well as, “apply a liquid to children’s mouths with brushes”, which caused the children to scream and later die.{{sfn|Levy|2009}} The Sisak camp commander, aphysician [[Antun Najžer]], was dubbed the "Croatian [[Josef Mengele|Mengele]]" by survivors.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/ww2-children-s-concentration-camp-commemorated-in-sisak/p%C3%ABrkujtohet-n%C3%AB-kroaci-kampi-i-p%C3%ABrqendrimit-t%C3%AB-f%C3%ABmij%C3%ABve-i-luft%C3%ABs-s%C3%AB-dyt%C3%AB-bot%C3%ABrore |title=WWII Children’s Concentration Camp Remembered in Croatia |last=Milekic |first=Sven |date=6 October 2014 |website=[[Balkan Insight]] |publisher=Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) |access-date= 10 May 2020}}</ref> |

|||

=== Ustashe militias and death squads === |

|||

[[Diana Budisavljević]], a humanitarian of Austrian descent, carried out rescue operations and saved more than 15,000 children from Ustaše camps.<ref>{{cite book | ref = | editor-last = Kolanović | editor-first = Josip | publisher = [[Croatian State Archives]] and Public Institution [[Jasenovac Memorial Area]] | title = Dnevnik Diane Budisavljević 1941–1945 | location = Zagreb | year = 2003 | isbn = 978-9-536-00562-8 |pp=284–85}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | ref = | title=Die Heldin aus Innsbruck – Diana Obexer Budisavljević|year=2014|publisher=Svet knjige|location=Belgrade|url=http://svetknjige.net/book.php?var=531|first=Boško|last=Lomović | isbn = 978-86-7396-487-4 |p=28}}</ref> |

|||

=== List of concentration and death camps === |

|||

* [[Jasenovac concentration camp|Jasenovac]] (I–IV) — around 100,000 inmates perished there, at least 52,000 Serbs |

|||

* [[Stara Gradiška concentration camp|Stara Gradiška]] (Jasenovac V) — more than 12,000 inmates lost their lives, mostly Serbs |

|||

* [[Gospić concentration camp|Gospić]] — between 24,000 and 42,000 inmates died, predominantly Serbs |

|||

[[File:Children in Stara Gradiska.jpg|thumb|[[Stara Gradiška concentration camp]]]] |

|||

* [[Jadovno concentration camp|Jadovno]] — between 15,000 and 48,000 Serbs and Jews perished there |

|||

* [[Slana concentration camp|Slana and Metajna]] — between 4,000 and 12,000 Serbs, Jews and communists died |

|||

* [[Sisak children's concentration camp|Sisak]] — 6,693 children passed through the camp, mostly Serbs, between 1,152 and 1,630 died |

|||

* [[Danica concentration camp|Danica]] — around 5,000, mostly Serbs, were transported to the camp, some of them were executed |

|||

* [[Jastrebarsko children's camp|Jastrebarsko]] — 3,336 Serb children passing through the camp, between 449 and 1,500 died |

|||

* [[Kruščica concentration camp|Kruščica]] — around 5,000 Jews and Serbs were interred at the camp, while 3,000 lost their lives |

|||

* [[Đakovo internment camp|Đakovo]] — 3,800 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred at the camp, at least 569 died |

|||

* [[Lobor concentration camp|Lobor]] — more than 2,000 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred, at least 200 died |

|||

* [[Kerestinec camp|Kerestinec]] — 111 Serbs, Jews and communists were captured, 85 were killed |

|||

* [[Sajmište concentration camp|Sajmište]] — the camp at the NDH territory operated by the ''[[Einsatzgruppen]]'' and since May 1944 by Ustaše; between 20,000 and 23,000 Serbs, Jews, Roma and anti-fascists died here |

|||

* Hrvatska Mitrovica — the concetration camp in [[Sremska Mitrovica]] |

|||

== Massacres == |

|||

{{See also|List of mass executions and massacres in Yugoslavia during World War II}} |

|||

A large number of massacres were committed by the NDH armed forces, [[Croatian Home Guard (World War II)|Croatian Home Guard]] (''Domobrani'') and [[Ustashe Militia|Ustaše Militia]]. |

|||

[[File:Ustaše sawing off the head of a Serb civilian.jpg|thumb|Ustaše sawing off the head of a Serb civilian, Branko Jungić]] |

[[File:Ustaše sawing off the head of a Serb civilian.jpg|thumb|Ustaše sawing off the head of a Serb civilian, Branko Jungić]] |

||

The Ustaše Militia was organised in 1941 into five (later 15) 700-man battalions, two railway security battalions and the elite Black Legion and Poglavnik Bodyguard Battalion (later Brigade). They were predominantly recruited among the uneducated population and working class.{{sfn|Yeomans|2015|p=301}} |

|||

The Ustaše Militia was organised in 1941 into five (later 15) 700-man battalions, two railway security battalions and the elite Black Legion and Poglavnik Bodyguard Battalion (later Brigade). They were predominantly recruited among the uneducated population and working class. |

|||

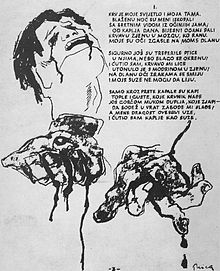

In the summer of 1941, Ustashe militias and death squads burnt villages and killed thousands of civilian Serbs in the country-side in sadistic ways with various weapons and tools. Men, women, children were hacked to death, thrown alive into pits and down ravines, or set on fire in churches.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=17}} Some Serb villages near Srebrenica and Ozren were wholly massacred while children were found impaled by stakes in villages between Vlasenica and Kladanj.{{sfn|Paris|1961|p=104}} The Ustashe cruelty and sadism shocked even Nazi commanders.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=vii}} A [[Geheime Staatspolizei|Gestapo]] report to Reichsführer SS [[Heinrich Himmler]], dated 17 February 1942, stated:{{blockquote|Increased activity of the bands [of rebels] is chiefly due to atrocities carried out by Ustaše units in Croatia against the Orthodox population. The Ustaše committed their deeds in a bestial manner not only against males of conscript age, but especially against helpless old people, women and children. The number of the Orthodox that the Croats have massacred and sadistically tortured to death is about three hundred thousand.<ref>[[Uki Goñi|Goñi, Uki]]. ''The real Odessa: Smuggling the Nazis to Perón's Argentina''; Granta, 2002, p. 202. {{ISBN|9781862075818}}</ref>}} |

|||

In the summer of 1941, Ustaše militias and death squads burnt villages and killed thousands of civilian Serbs in the country-side in sadistic ways with various weapons and tools. Men, women, children were hacked to death, thrown alive into pits and down ravines, or set on fire in churches.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=17}} Some Serb villages near Srebrenica and Ozren were wholly massacred while children were found impaled by stakes in villages between Vlasenica and Kladanj.{{sfn|Paris|1961|p=104}} The Ustaše cruelty and sadism shocked even Nazi commanders.{{sfn|Yeomans|2012|p=vii}} A [[Geheime Staatspolizei|Gestapo]] report to Reichsführer SS [[Heinrich Himmler]], dated 17 February 1942, stated:{{blockquote|Increased activity of the bands [of rebels] is chiefly due to atrocities carried out by Ustaše units in Croatia against the Orthodox population. The Ustaše committed their deeds in a bestial manner not only against males of conscript age, but especially against helpless old people, women and children. The number of the Orthodox that the Croats have massacred and sadistically tortured to death is about three hundred thousand.<ref>[[Uki Goñi|Goñi, Uki]]. ''The real Odessa: Smuggling the Nazis to Perón's Argentina''; Granta, 2002, p. 202. {{ISBN|9781862075818}}</ref>}} |

|||

==== Massacres ==== |

|||

{{Main|List of mass executions and massacres in Yugoslavia during World War II}} |

|||

A large number of massacres were committed by the Ustashe. Some of the more notable ones were: |

|||

* [[Gudovac massacre]] (28 April 1941), 184–196 Serbs [[Summary execution|summary executed]], after arrest orders by Kvaternik. |

|||

* [[Glina massacres#May 1941|Glina massacre]] (11–12 May 1941), 260–300 Serbs herded into an Orthodox church and shot, after which it was set on fire. |

|||

* [[Glina massacres#July–August 1941|Glina massacres]] (30 July–3 August 1941), 200 Serbs, willing to convert to Catholicism in return for amnesty, massacred at an Orthodox church. Between 500–2000 other Serbs later massacred in neighbouring villages by [[Maks Luburić|Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić]]'s forces. |

|||

* [[Garavice|Garavice massacres]] (July–September 1941), 15,000 Serbs massacred along with some Jews and Roma victims. |

|||

* [[Prebilovci massacre]] (4–6 August 1941), 650 Serb women and children killed by being thrown into the Golubinka pit. Some 4000 Serbs later massacred in neighbouring places during that summer. |

|||

[[Charles King (professor of international affairs)|Charles King]] emphasized that the concentration camps losing their central place in the Holocaust and genocide research because a large proportion of victims perished in mass executions, ravines and pits.{{sfn|King|2012}} He explained that the actions of the German allies, including the Croatian one, and the town- and village-level elimination of minorities also played a significant role.{{sfn|King|2012}} |

|||

=== Concentration camps === |

|||

{{See also|Jasenovac concentration camp|Concentration camps in the Independent State of Croatia}} |

|||

[[File:Head of Serbian orthodox priest and Croatian soldiers.jpg|thumb|left|Head of [[Serbian Orthodox]] priest and Ustaše]] |

|||

The Ustashe set up temporary concentration camps in the spring of 1941 and laid the groundwork for a network of permanent camps in autumn.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=18}} The creation of concentration camps and extermination campaign of Serbs had been planned by the Ustashe leadership long before 1941.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=16}} In Ustashe state exhibits in Zagreb, the camps were portrayed as productive and "peaceful work camps", with photographs of smiling inmates.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=2}} Croatia was the only Axis satellite to have erected camps specifically for children.{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=18}} |

|||

=== Central Croatia === |

|||

Serbs, Jews and Romani were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as [[Jasenovac concentration camp|Jasenovac]], [[Stara Gradiška concentration camp|Stara Gradiška]], [[Gospić concentration camp|Gospić]] and [[Jadovno concentration camp|Jadovno]]. There were 22–26 camps in NDH in total.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=69}} Special camps for children were those at [[Sisak children's concentration camp|Sisak]], [[Gornja Rijeka concentration camp|Gornja Rijeka]] and [[Jastrebarsko concentration camp|Jastrebarsko]],{{sfn|Bulajić|2002|p=7}} while Stara Gradiška held thousands of children and women.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=70}} |

|||

On 28 April 1941, approximately 184–196 Serbs from [[Bjelovar]] were [[Gudovac massacre|summarily executed]], after arrest orders by Kvaternik. It was the first act of mass murder committed by the Ustaše upon coming to power, and presaged the wider campaign of genocide against Serbs in the NDH that lasted until the end of the war. A few days following the massacre of Bjelovar Serbs, the Ustaše rounded up 331 Serbs in the village of Otočac. The victims were forced to dig their own graves before being hacked to death with axes. Among the victims was the local Orthodox priest and his son. The former was made to recite prayers for the dying as his son was killed. The priest was then tortured, his hair and beard was pulled out, eyes gouged out before he was skinned alive.<ref name="Cornwell">{{cite book |last1=Cornwell |first1=John |title=Hitler's Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII |date=2000 |publisher=Penguin |isbn=978-0-14029-627-3 |pages=251–252 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mFHKrYwv87sC&pg=PA251}}</ref> |

|||

Between 29 and 37 July 1941, 280 Serbs were killed and thrown into pits near [[Hrvatska Kostajnica|Kostajnica]].{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|pp=228}} A large scale massacres took place in [[Staro Selo Topusko]],{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|pp=132-136}} [[Vojišnica]]{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=79}} and [[Gvozd|Vrginmost]]{{sfn|Bulajić|1988–1989|p=254}} About 60% of [[Sadilovac]] residents lost their lives during the war.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=186}} More than 400 Serbs were killed in their homes, including 185 children.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=186}} On 31 July 1942, in the Sadilovac church the Ustaše under Milan Mesić's command massacred more than 580 inhabitants of the surrounding villages, including about 270 children.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|pp=186-187}} |

|||

The largest and most notorious camp was the Jasenovac-Stara Gradiška complex,{{sfn|Yeomans|2013|p=18}} the largest extermination camp in the Balkans.<ref>{{harvnb|Yeomans|2015|p=21}}, {{harvnb|Pavlowitch|2008|p=34}}</ref> An estimated 100,000 inmates perished there, most Serbs.<ref name="Yeomans 2015 3">{{harvnb|Yeomans|2015|p=3}}, {{harvnb|Pavlowitch|2008|p=34}}</ref> Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, the commander-in-chief of all the Croatian camps, announced the great "efficiency" of the Jasenovac camp at a ceremony on 9 October 1942, and also boasted: "We have slaughtered here at Jasenovac more people than the Ottoman Empire was able to do during its occupation of Europe."{{sfn|Paris|1961|p=132}} |

|||

==== Glina ==== |

|||

[[File:Srbosjek (knife) used in Croatia - 1941–1945.jpg|thumb|The ''[[Srbosjek]]'' ("Serb cutter"), an agricultural knife worn over the hand that was used by the Ustaše for the quick slaughter of inmates.]] |

|||

{{Main|Glina massacres}} |

|||

Bounded by rivers and two barbed-wire fences making escape unlikely, the Jasenovac camp was divided into five camps, the first two closed in December 1941, while the rest were active until the end of the war. Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) held women and children. The Ciglana (brickyards, Jasenovac III) camp, the main killing ground and essentially a death camp, had 88% mortality rate, higher than [[Auschwitz]]'s 84.6%.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=70}} A former brickyard, a furnace was engineered into a crematorium, with witness testimony of some, including children, being burnt alive and stench of human flesh spreading in the camp.{{sfn|Levy|2011|pp=70–71}} Luburić had a gas chamber built at Jasenovac V, where a considerable number of inmates were killed during a three-month experiment with [[sulfur dioxide]] and [[Zyklon B]], but this method was abandoned due to poor construction.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Still, that method was unnecessary, as most inmates perished from starvation, disease (especially [[typhus]]), assaults with mallets, maces, axes, poison and knives.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} The ''srbosjek'' ("Serb-cutter") was a glove with an attached curved blade designed to cut throats.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Large groups of people were regularly executed upon arrival outside camps and thrown into the river.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Unlike German-run camps, Jasenovac specialized in brutal one-on-one violence, such as guards attacking barracks with weapons and throwing the bodies in the trenches.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} The infamous camp commander [[Miroslav Filipović|Filipović]], dubbed ''fra Sotona'' ("brother Satan") and the "personification of evil", on one occasion drowned Serb women and children by flooding a cellar.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} Filipović and other camp commanders (such as [[Dinko Šakić]] and his wife Nada Šakić, the sister of Maks Luburić), used ingenious torture.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=71}} There were throat-cutting contests of Serbs, in which prison guards made bets among themselves as to who could slaughter the most inmates. It was reported that guard and former Franciscan priest [[Petar Brzica]] won a contest on 29 August 1942 after cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.{{sfn|Lituchy|2006|p=117}} Inmates were tied and hit over the head with mallets and half-alive hung in groups by the Granik ramp crane, their intestines and necks slashed, then dropped into the river.{{sfn|Bulajić|2002|p=231}} When the Partisans and Allies closed in at the end of the war, the Ustashe began mass liquidations at Jasenovac, marching women and children to death, and shooting most of the remaining male inmates, then torched buildings and documents before fleeing.{{sfn|Levy|2011|p=72}} |

|||

On 11 or 12 May 1941, 260–300 Serbs were herded into an Orthodox church and shot, after which it was set on fire. The idea for this massacre reportedly came from Mirko Puk, who was the Minister of Justice for the NDH.{{sfn|Goldstein|2013|p=127}} On 10 May, Ivica Šarić, a specialist for such operations traveled to the town of [[Glina]] to meet with local Ustaše leadership where they drew up a list of names of all the Serbs between sixteen and sixty years of age to be arrested.{{sfn|Goldstein|2013|p=128}} After much discussion, they decided that all of the arrested should be killed.{{sfn|Goldstein|2013|p=129}} Many of the town's Serbs heard rumors that something bad was in store for them but the vast majority did not flee. On the night of 11 May, mass arrests of male Serbs over the age of sixteen began.{{sfn|Goldstein|2013|p=129}} The Ustaše then herded the group into an Orthodox Church and demanded that they be given documents proving the Serbs had all converted to Catholicism. Serbs who did not possess conversion certificates were locked inside and massacred.<ref name="Cornwell" /> The church was then set on fire, leaving the bodies to burn as Ustaše stood outside to shoot any survivors attempting to escape the flames.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Singleton |first1=Fred |title=A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples |date=1985 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-52127-485-2 |page=177 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qTLSZ3ucaZMC&pg=PA177}}</ref> |

|||

A similar massacre of Serbs occurred on 30 July 1941. 700 Serbs were gathered into a church under the premise that they would be converted. Victims were killed by having their throats cut or by having their heads smashed in with rifle butts. Between 500–2000 other Serbs were later massacred in neighbouring villages by [[Maks Luburić|Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić]]'s forces, continuing until 3 August. In these massacres specifically males 16 years and older were killed.<ref name="Locke & Littell">{{cite book |last1=Locke |first1=Hubert G. |last2=Littell |first2=Marcia Sachs |title=Holocaust and Church Struggle: Religion, Power, and the Politics of Resistance |date=1996 |publisher=University Press of America |isbn=978-0-76180-375-1 |page=23 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vzBx7nIGy1AC&pg=PA23}}</ref> Only one of the victims, Ljubo Jednak, survived by playing dead. |

|||

[[Diana Budisavljević]], a humanitarian of Austrian descent, carried out rescue operations and saved more than 15,000 children from Ustashe camps.<ref>{{cite book | ref = harv | editor-last = Kolanović | editor-first = Josip | publisher = [[Croatian State Archives]] and Public Institution [[Jasenovac Memorial Area]] | title = Dnevnik Diane Budisavljević 1941–1945 | location = Zagreb | year = 2003 | isbn = 978-9-536-00562-8 |pp=284–85}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | ref = harv | title=Die Heldin aus Innsbruck – Diana Obexer Budisavljević|year=2014|publisher=Svet knjige|location=Belgrade|url=http://svetknjige.net/book.php?var=531|first=Boško|last=Lomović | isbn = 978-86-7396-487-4 |p=28}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

==== Lika ==== |

||

On 6 August 1941, the Ustaše killed and burned more than 280 villagers in [[Mlakva, Croatia|Mlakva]], including 191 children.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=286}} Between June and August 1941, about 890 Serbs from [[Ličko Petrovo Selo]] and [[Melinovac]] were killed and thrown in the so-called Delić pit.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=304}} |

|||

During the war, the Ustaše massacred more than 900 Serbs in [[Divoselo]], more than 500 in [[Smiljan]], as well as more than 400 in Široka Kula near [[Gospić]].{{sfn|Zatezalo|1989|p=180}} On 2 August 1941, the Ustaše trapped about 120 children and women and 50 men who tried to escape from Divoselo. After a few days of imprisonment, where women were raped, they were stabbed in groups and thrown into the pits.{{sfn|Perrone|2017}} |

|||

=== Slavonia === |

|||

[[File:Kuća Save Šumanovića 395.jpg|thumb|[[Sava Šumanović]]'s house in [[Šid]], who was tortured and killed together with 150 fellow citizens]] |

|||

On 21 December 1941, approximately 880 Serbs from [[Dugo Selo Lasinjsko]] and [[Prkos Lasinjski]] were killed in the Brezje forest.{{sfn|Zatezalo|2005|p=126}} On the [[Old New Year#In Serbia|Serbian New Year]], 14 January 1942, [[Voćin massacre (1942)|the biggest slaughter of the civilians]] from [[Slavonia]] started. Villages were burned, and about 350 people were deported to [[Voćin]] and executed.{{sfn|Škiljan|2010}} |

|||

=== Syrmia === |

|||