Massachusetts

Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Admitted to the Union | February 6, 1788 (6th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Boston |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Boston |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Deval Patrick (D) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Vacant |

| Legislature | General Court |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Elizabeth Warren (D) Ed Markey (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 9 Democrats (list) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 6,692,824 (2,013 est)[1] |

| • Density | 840/sq mi (324/km2) |

| • Median household income | $65,401 (2,008) |

| • Income rank | 6th |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None |

| Traditional abbreviation | Mass. |

| Latitude | 41° 14′ N to 42° 53′ N |

| Longitude | 69° 56′ W to 73° 30′ W |

Massachusetts /ˌmæsəˈtʃuːs[invalid input: 'ɨ']ts/ , officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. Massachusetts is the 7th smallest, but the 14th most populous and the 3rd most densely populated of the 50 United States. Massachusetts features two separate metropolitan areas: Greater Boston in the east and the Springfield metropolitan area in the west. Approximately two-thirds of Massachusetts' population lives in Greater Boston. Generally the Greater Boston boundary is regarded as the Atlantic Ocean to the east and areas just north, west, and south of Interstate 495 to the west, north, and south. Western Massachusetts features one urban area - the Knowledge Corridor along the Connecticut River - and a mix of college towns and rural areas. Many of Massachusetts' towns, cities, and counties have names identical to ones in England. Massachusetts is the most populous of the six New England states and has the nation's sixth highest GDP per capita.

Massachusetts has played a significant historical, cultural, and commercial role in American history. Plymouth was the site of the colony founded in 1620 by the Pilgrims, passengers of the Mayflower. Harvard University, founded in 1636, is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States. In 1692, the town of Salem and surrounding areas experienced one of America's most infamous cases of mass hysteria, the Salem witch trials. In the 18th century, the Protestant First Great Awakening, which swept the Atlantic world, originated from the pulpit of Northampton, Massachusetts preacher Jonathan Edwards. In the late 18th century, Boston became known as the "Cradle of Liberty" for the agitation there that led to the American Revolution and the independence of the United States from Great Britain. In 1777, General Henry Knox founded the Springfield Armory, which during the Industrial Revolution catalyzed numerous important technological advances, including interchangeable parts. In 1786, Shays' Rebellion, a populist revolt led by disaffected Revolutionary War veterans, led directly to the United States Constitutional Convention.

Before the American Civil War, Massachusetts was a center for the temperance, transcendentalist, and abolitionist movements. In 1837, Mount Holyoke College, the United States' first college for women, was opened in the Connecticut River Valley town of South Hadley. In the late 19th century, the (now) Olympic sports of basketball and volleyball were invented in the Western Massachusetts cities of Springfield and Holyoke, respectively. In 2004, Massachusetts became the first U.S. state to legally recognize same-sex marriage as a result of the decision of the state's Supreme Judicial Court. Massachusetts has contributed many prominent politicians to national service, including members of the Adams family and the Kennedy family.

Originally dependent on fishing, agriculture, and trade, Massachusetts was transformed into a manufacturing center during the Industrial Revolution. During the 20th century, Massachusetts' economy shifted from manufacturing to services. In the 21st century, Massachusetts is a leader in higher education, health care technology, high technology, and financial services.

Name

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was named after the indigenous population, the Massachusett, whose name can be segmented as mass-adchu-s-et, where mass- is "large", -adchu- is "hill", -s- is a diminutive suffix meaning "small", and -et is a locative suffix, identifying a place. It has been translated as "near the great hill",[14] "by the blue hills", "at the little big hill", or "at the range of hills", referring to the Blue Hills, or in particular, Great Blue Hill, located on the boundary of Milton and Canton.[15][16] Alternatively, Massachusett has been represented as Moswetuset, from the name of the Moswetuset Hummock (meaning "hill shaped like an arrowhead") in Quincy where Plymouth Colony commander Miles Standish and Squanto, a Native American, met Chief Chickatawbut in 1621.[17][18]

The official name of the state is the "Commonwealth of Massachusetts".[19] Colloquially, it is often referred to simply as "the Commonwealth". While this designation is part of the state's official name, it has no practical implications. Massachusetts has the same position and powers within the United States as other states.[20]

Geography

Massachusetts is the 7th smallest state in the United States. It is located in the New England region of the northeastern United States, and has an area of 10,555 square miles (27,340 km2).[9] Several large bays distinctly shape its coast. Boston is the largest city, at the inmost point of Massachusetts Bay, and the mouth of the Charles River.

Despite its small size, Massachusetts features numerous distinctive regions: in the west, the rolling Berkshire Mountains surround the fertile Connecticut River Valley, (the latter of which contains metropolitan Springfield;) in central Massachusetts, rural hill-towns surround Worcester; while the east encompasses the urban environs of Greater Boston, the sandy beaches of Cape Cod, and the rocky shorelines of the northern coast.

The National Park Service administers a number of natural and historical sites in Massachusetts.[21] Along with twelve national historic sites, areas, and corridors, the National Park Service also manages the Cape Cod National Seashore and the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.[21] In addition, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation maintains a number of parks, trails, and beaches throughout Massachusetts.[22][23][24]

Ecology

The primary biome of inland Massachusetts is temperate deciduous forest.[25] Although much of Massachusetts had been cleared for agriculture, leaving only traces of old growth forest in isolated pockets, secondary growth has regenerated in many rural areas as farms have been abandoned.[26] Currently, forests cover around 62% of Massachusetts.[27][28] The areas most affected by human development include the Greater Boston area in the east and the Springfield metropolitan area in the west, although the latter includes agricultural areas throughout the Connecticut River Valley.[29] Animals that have become locally extinct over the past few centuries include the gray wolf, elk, wolverine, and eastern cougar.[30]

A number of species are doing well despite (and in some cases because of) the increased urbanization of Massachusetts. Peregrine falcons utilize office towers in larger cities as nesting areas,[31] and the population of coyotes, whose diet may include garbage and roadkill, has been increasing in recent decades.[32] White-tailed deer, raccoons, wild turkeys and eastern gray squirrels are also found throughout Massachusetts.[30][33] In more rural areas in the western part of Massachusetts, larger mammals such as moose and black bears have returned, largely due to reforestation following the regional decline in agriculture.[34][35]

Massachusetts is located along the Atlantic Flyway, a major route for migratory waterfowl along the Atlantic coast.[36] Lakes in central Massachusetts provide habitat for the common loon, especially Quabbin Reservoir,[37] while a significant population of long-tailed ducks winter off Nantucket.[38] Small offshore islands and beaches are home to roseate terns and are important breeding areas for the locally threatened piping plover.[39][40] Protected areas such as the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge provide critical breeding habitat for shorebirds and a variety of marine wildlife including a large population of gray seals.[41]

Freshwater fish species in Massachusetts include bass, carp, catfish, and trout,[42] while saltwater species such as Atlantic cod, haddock and American lobster populate offshore waters.[43] Other marine species include Harbor seals, the endangered North Atlantic right whales, as well as humpback whales, fin whales, minke whales and Atlantic white-sided dolphins.[30]

History

Early

Massachusetts was originally inhabited by tribes of the Algonquian language family such as the Wampanoag, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Pocomtuc, Mahican, and Massachusett.[44][45] While cultivation of crops like squash and corn supplemented their diets, these tribes were generally dependent on hunting, gathering and fishing for most of their food supply.[44] Villages consisted of lodges called wigwams as well as long houses,[45] and tribes were led by male or female elders known as sachems.[46]

Colonial period (1620–1780)

In the early 1600s (after contact had been made with Europeans, but before permanent settlements were established), large numbers of the indigenous people in the northeast of what is now the United States were killed by virgin soil epidemics such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and perhaps leptospirosis.[47][48] In 1617–19, smallpox reportedly killed 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[49]

The first English settlers in Massachusetts, the Pilgrims, established their settlement at Plymouth in 1620, and developed friendly relations with the native Wampanoag.[50] This was the second successful permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. The Pilgrims were soon followed by other Puritans, who established the Massachusetts Bay Colony at present-day Boston in 1630.[51]

The Puritans, who believed the Church of England was too hierarchical (among other disagreements), came to Massachusetts for religious freedom,[52] although, unlike the Plymouth colony, the bay colony was founded under a royal charter. Both religious dissent and expansionism resulted in several new colonies being founded shortly after Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay elsewhere in New England. Dissenters such as Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams were banished due to religious disagreements; (Hutchinson held meetings in her home discussing flaws in the Puritan beliefs, while Williams believed that the Puritan beliefs were wrong, and the Indians must be respected.) In 1636, Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island and Hutchinson joined him there several years later.[53]

In 1641, Massachusetts expanded inland significantly, acquiring the Connecticut River Valley settlement of Springfield, which had recently disputed with, and defected from its original administrators, the Connecticut Colony. This established Massachusetts' southern border in the west.[54]

In 1691, the colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth were united (along with present-day Maine, which had previously been divided between Massachusetts and New York) into the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[55] Shortly after the arrival of the new province's first governor, Sir William Phips, the Salem witch trials took place, in which a number of men and women were hanged.[56]

During the Revolution, Salem, Massachusetts, became a center for privateering. Although the documentation is incomplete, about 1,700 Letters of Marque, issued on a per-voyage basis, were granted during the American Revolution. Nearly 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers and are credited with capturing or destroying about 600 British ships.[57] During the War of 1812, privateering resumed. The Old China Trade left a significant mark in two historic districts, Chestnut Street District, part of the Samuel McIntire Historic District containing 407 buildings, and the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, consisting of 12 historic structures and about 9 acres (36,000 m2) of land along the waterfront in Salem. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary merchants in Salem, and owner of the Grand Turk, the first New England vessel to trade directly with China.

The most destructive earthquake yet known in New England occurred in 1755, causing considerable damage across Massachusetts.[58][59]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help), about the Battles of Lexington and ConcordMassachusetts was a center of the movement for independence from Great Britain; colonists here had long had uneasy relations with the British monarchy, including open rebellion under the Dominion of New England in the 1680s.[55] Protests against British attempts to tax the colonies after the French and Indian War ended in 1763 led to the Boston Massacre in 1770, and the 1773 Boston Tea Party escalated tensions to the breaking point.[60] Anti-Parliamentary activity by men such as Samuel Adams and John Hancock, followed by reprisals by the British government, were a primary reason for the unity of the Thirteen Colonies and the outbreak of the American Revolution.[61]

The Battles of Lexington and Concord initiated the American Revolutionary War and were fought in the homonymous Massachusetts towns.[62] Future President George Washington took over what would become the Continental Army after the battle. His first victory was the Siege of Boston in the winter of 1775–76, after which the British were forced to evacuate the city.[63] The event is still celebrated in Suffolk County as Evacuation Day.[64]

Federal period

Bostonian John Adams, known as the "Atlas of Independence", was an important figure in both the struggle for independence as well as the formation of the new United States.[65] Adams was highly involved in the push for separation from Britain and the writing of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780 (which, in the Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker cases, effectively made Massachusetts the first state to have a constitution that declared universal rights and, as interpreted by Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice William Cushing, abolished slavery).[65][66][a] Later, Adams was active in early American foreign affairs and succeeded Washington as US President.[65] His son, John Quincy Adams, would go on to become the sixth US President.[65]

From 1786 to 1787, an armed uprising led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays wrought havoc throughout Massachusetts, and ultimately attempted to seize the U.S. Federal Armory at Springfield. The rebellion was one of the major factors in the decision to draft a stronger national constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation.[69] On February 6, 1788, Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify the US Constitution.[70]

19th century

In 1820, Maine separated from Massachusetts, of which it had been first a contiguous and then a non-contiguous part, and entered the Union as the 23rd state as a result of the ratification of the Missouri Compromise.[71]

During the 19th century, Massachusetts became a national leader in the American Industrial Revolution, with factories around Boston producing textiles and shoes, and factories around Springfield producing precision manufacturing tools, paper, and textiles.[72][73] The economy transformed from one based primarily on agriculture to an industrial one, initially making use of waterpower and later the steam engine to power factories, and canals and later railroads for transporting goods and materials.[74] At first, the new industries drew labor from Yankees on nearby subsistence farms, and later relied upon immigrant labor from Europe and Canada.[75][76]

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Massachusetts was a center of progressivism and abolitionist activity. Horace Mann made the state system of schools the national model.[77] Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson made major contributions to American thought.[78] Members of the transcendentalist movement, they emphasized the importance of the natural world and emotion to humanity.[78]

Although significant opposition to abolitionism existed early on in Massachusetts, resulting in anti-abolitionist riots between 1835 and 1837,[79] opposition to slavery gradually increased in the next few decades.[80][81] Abolitionists John Brown and Sojourner Truth lived in Springfield and Northampton, respectively, while Frederick Douglass lived in Boston. The works of such abolitionists contributed to Massachusetts' actions during the Civil War. Massachusetts was the first state to recruit, train, and arm a Black regiment with White officers, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.[82] The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial in Boston Common contains a relief depicting the 54th regiment.[83]

20th century

The industrial economy began a decline in the early 20th century with the exodus of many manufacturing companies. By the 1920s competition from the South and Midwest, followed by the Great Depression, led to the collapse of the three main industries in Massachusetts: textiles, shoemaking, and precision mechanics.[84] This decline would continue into the later half of the century; between 1950 and 1979, the number of Bay Staters involved in textile manufacturing declined from 264,000 to 63,000.[85] The 1969 closure of the Springfield Armory, in particular, spurred an exodus of high-paying jobs from Western Massachusetts, which suffered greatly as it de-industrialized during the last 40 years of the 20th century.[86]

Massachusetts manufactured 3.4 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking tenth among the 48 states.[87] In Eastern Massachusetts, following World War II, the economy was transformed from one based on heavy industry into a service and high-tech based economy.[88] Government contracts, private investment, and research facilities led to a new and improved industrial climate, with reduced unemployment and increased per capita income. Suburbanization flourished, and by the 1970s, the Route 128 corridor was dotted with high-technology companies who recruited graduates of the area's many elite institutions of higher education.[89]

The Kennedy family was prominent in Massachusetts politics in the 20th century. Children of businessman and ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. included John F. Kennedy, who was a senator and US president before his assassination in 1963, Robert F. Kennedy, who was a senator, US attorney general and presidential candidate before his assassination in 1968, Ted Kennedy, a senator from 1962 until his death in 2009,[90] and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, a co-founder of the Special Olympics.[91] The famous Kennedy Compound is located at Hyannisport on Cape Cod.[92]

George H. W. Bush, 41st President of the United States (1989-1993) was born in Milton, Massachusetts in 1924.

Recent history

In 1987, the state received federal funding for the Central Artery/Tunnel Project. Commonly known as "the Big Dig", it was at the time the biggest federal highway project ever approved.[93] The project included making the Central Artery a tunnel under downtown Boston, in addition to the re-routing of several other major highways.[94] Often controversial, with numerous claims of graft and mismanagement, and with its initial price tag of $2.5 billion increasing to a final tally of over $15 billion, the Big Dig has nonetheless changed the face of Downtown Boston.[93] It has connected areas that were once divided by elevated highway, (much of the raised old Central Artery was replaced with the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway) and improved traffic conditions along a number of routes.[93][94]

On May 17, 2004, Massachusetts became the first state in the U.S. to legalize same-sex marriage after a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling in November 2003 determined that the exclusion of same-sex couples from the right to a civil marriage was unconstitutional.[95]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 378,787 | — | |

| 1800 | 422,845 | 11.6% | |

| 1810 | 472,040 | 11.6% | |

| 1820 | 523,287 | 10.9% | |

| 1830 | 610,408 | 16.6% | |

| 1840 | 737,699 | 20.9% | |

| 1850 | 994,514 | 34.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,231,066 | 23.8% | |

| 1870 | 1,457,351 | 18.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,783,085 | 22.4% | |

| 1890 | 2,238,947 | 25.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,805,346 | 25.3% | |

| 1910 | 3,366,416 | 20.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,852,356 | 14.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,249,614 | 10.3% | |

| 1940 | 4,316,721 | 1.6% | |

| 1950 | 4,690,514 | 8.7% | |

| 1960 | 5,148,578 | 9.8% | |

| 1970 | 5,689,170 | 10.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,737,037 | 0.8% | |

| 1990 | 6,016,425 | 4.9% | |

| 2000 | 6,349,097 | 5.5% | |

| 2010 | 6,547,629 | 3.1% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 6,692,824 | 2.2% | |

| [1][96][97][98] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Massachusetts was 6,692,824 on July 1, 2013, a 2.2% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[1]

Massachusetts had an estimated 2013 population of 6,692,824.[1] As of 2000, Massachusetts was estimated to be the third most densely populated U.S. state, with 809.8 people per square mile, behind New Jersey and Rhode Island.[9] Massachusetts in 2008 included 919,771 foreign-born residents.

Most Bay Staters live within the Boston Metropolitan Area, also known as Greater Boston, which in its most expansive sense includes New England's two largest cities, Boston and Worcester. The state's only other metropolitan area is the Springfield Metropolitan Area, also known as Greater Springfield. Centered in the Connecticut River Valley, Greater Springfield includes the revitalizing city of Springfield, and an eclectic array of college towns, (e.g. Amherst and Northampton) and rural areas to the north and west. Geographically, the center of population of Massachusetts is located in the town of Natick.[99]

Like the rest of the northeastern United States, the population of Massachusetts has continued to grow in the past few decades, although at a slower pace than states in the South or West.[100] The latest census estimates show that Massachusetts's population grew by 3.9% since 2000, compared with nearly 10% nationwide. In their decisions to leave Massachusetts, most former residents cited high housing costs and a high cost of living.[101] Another factor has been the transformation from a manufacturing economy into one based on high technology, leaving limited employment options for lower-skilled workers, particularly males.[102]

Foreign immigration is more than making up for these losses, causing the state's population to continue to grow as of the 2010 Census (particularly in Massachusetts gateway cities where costs of living are lower).[100][103] 40% of foreign immigrants were from Central or South America, according to a 2005 Census Bureau study. Many residents who have settled in Greater Springfield claim Puerto Rican descent.[100] Many areas of Massachusetts showed relatively stable population trends between 2000 and 2010.[103] Exurban Boston and coastal areas grew the most rapidly, while Berkshire County in far Western Massachusetts and Barnstable County on Cape Cod were the only counties to lose population as of the 2010 Census.[103] Both of these counties feature many "second homes," and constitute major centers of Massachusetts tourism.

In 2005, 79% of the state population spoke English, 7% spoke Spanish, 3.5% spoke Portuguese, and 1% spoke either French or Chinese.[104]

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the population was 6,547,629, of which 3,166,628 (48.4%) were male and 3,381,001 (51.6%) were female. In terms of age, 78.3% were over 18 years old and 13.8% were over 65 years old; the median age is 39.1 years. The median age for males is 37.7 years and 40.3 years for females.

Race and ancestry

In terms of race and ethnicity, Massachusetts was 83.7% White (75.8% Non-Hispanic White), 7.9% Black or African American, 0.8% American Indian and Alaska Native, 5.8% Asian American, <0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 4.7% from Some Other Race, and 2.0% from Two or More Races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 10.1% of the population. (US Census 2012 Estimates) [105][106]

| Racial composition | 1990[107] | 2000[108] | 2010[109] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 89.8% | 84.5% | 80.4% |

| Black | 5.0% | 5.4% | 6.6% |

| Asian | 2.4% | 3.8% | 5.3% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

- | - | - |

| Other race | 2.6% | 3.7% | 4.7% |

| Two or more races | - | 2.3% | 2.6% |

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 95.4% in 1970 to 75.8% in 2012.[105][110] As of 2011, non-Hispanic whites were involved in 63.6% of all the births.[111]

As late as 1795, the population of Massachusetts was nearly 95% of English ancestry.[112] During the early and mid 19th century, immigrant groups began arriving to Massachusetts in large numbers; first from Ireland in the 1840s;[113] today the Irish and part-Irish are the largest ancestry group in the state at nearly 25% of the total population. Others arrived later from Quebec as well as places in Europe such as Italy and Poland.[114] In the early 20th century, a number of African Americans migrated to Massachusetts, although in somewhat fewer numbers than many other Northern states.[115] Later in the 20th century, immigration from Latin America, Africa, and East Asia increased considerably. Massachusetts has the third largest population of Haitians in the United States.[116]

Massachusetts also has a relatively large population of Portuguese descent. Many of the earliest Portuguese-speaking immigrants came from the Azores in the 19th century to work in the whaling industry in cities like New Bedford.[117][118] Later, further waves of Portuguese arrived, this time often finding work in the textile mills.[118] Lowell is home to the second-largest Cambodian (Khmer) community in the nation.[119] The Wampanoag tribe maintains reservations at Aquinnah on Martha's Vineyard, at Grafton, and at Mashpee on Cape Cod,[120][121] while the Nipmuck maintain two state-recognized reservations in the central part of the state. While Massachusetts had avoided many of the more violent forms of racial strife seen elsewhere in the US, examples such as the successful electoral showings of the nativist (mainly anti-Catholic) Know Nothings in the 1850s,[122] the controversial Sacco and Vanzetti executions in the 1920s,[123] and Boston's opposition to desegregation busing in the 1970s[124] show that the ethnic history of Massachusetts was not completely harmonious.

Languages

The most common form of American English spoken in Massachusetts, other than General American English, are the New England accent and the Boston accent.

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[125] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 7.50% |

| Portuguese | 2.97% |

| Chinese (including Cantonese and Mandarin) | 1.59% |

| French | 1.11% |

| French Creole | 0.89% |

| Italian | 0.72% |

| Russian | 0.62% |

| Vietnamese | 0.58% |

| Greek | 0.41% |

| Arabic and Cambodian (including Mon-Khmer) (tied) | 0.37% |

As of 2010, 78.93% (4,823,127) of Massachusetts residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 7.50% (458,256) spoke Spanish, 2.97% (181,437) Portuguese, 1.59% (96,690) Chinese (which includes Cantonese and Mandarin), 1.11% (67,788) French, 0.89% (54,456) French Creole, 0.72% (43,798) Italian, 0.62% (37,865) Russian, and Vietnamese was spoken as a main language by 0.58% (35,283) of the population over the age of five. In total, 21.07% (1,287,419) of Massachusetts's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[125]

Religion

Massachusetts was founded and settled by the Puritans in 1628. The descendants of the Puritans belong to many different churches; in the direct line of inheritance are the Congregational/United Church of Christ, and congregations of Unitarian Universalist Association. Most people in Massachusetts were Christians. The headquarters of the Unitarian Universalist Association is located on Beacon Hill in Boston.[126]

Today, Protestants make up less than one quarter of the state's population. Roman Catholics now predominate because of massive immigration from primarily Ireland, followed by Italy, Portugal, Quebec, and Latin America. A large Jewish population came to the Boston and Springfield areas in 1880–1920. Mary Baker Eddy made the Boston Mother Church of Christian Science the world headquarters. Buddhists, Pagans, Hindus, Seventh-day Adventists, Muslims, and Mormons also can be found. Kripalu Center in Stockbridge, the Shaolin Meditation Temple in Springfield, and the Insight Meditation Center in Barre are examples of non-Abrahamic religious centers in Massachusetts. According to 2010 data from The Association of Religion Data Archives(ARDA) the largest single denominations are the Roman Catholic Church with 2,940,199 adherents; the United Church of Christ with 86,639 adherents; and the Episcopal Church with 81,999 adherents.[127]

The religious affiliations of the people of Massachusetts, according to a 2001 survey, are shown below:[128]

- Christian – 69%

- Catholic – 44%

- Protestant denominations – 25%

- Non-specific Protestant – 4%

- Baptist – 4%

- Congregational/United Church of Christ – 3%

- Episcopal – 3%

- Other denominations (2% or less each) – 11%

- Jewish – 3%

- Muslim – 1%

- Other – 7%

- No religion – 15%

- Refused to answer – 7%

Economy

The United States Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that the Massachusetts gross state product in 2012 was US$404 billion.[130] The per capita personal income in 2012 was $53,221, making it the third highest state in the nation.[131] Thirteen Fortune 500 companies are located in Massachusetts, the largest of which are the Liberty Mutual Insurance Group of Boston and MassMutual Financial Services of Springfield.[132] CNBC's list of "Top States for Business for 2010" has recognized Massachusetts as the fifth best state in the nation.[133] According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Massachusetts had the sixth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 6.73 percent.[134]

Sectors vital to the Massachusetts economy include higher education, biotechnology, finance, health care, and tourism. Route 128 was a major center for the development of minicomputers and electronics.[89] High technology remains an important sector. In recent years tourism has played an ever-important role in the state's economy, with Boston and Cape Cod being the leading destinations. Other popular tourist destinations include Salem, Plymouth, and the Berkshires. As of April 2013, the state's unemployment rate was 6.4%,[135] below the national level of 7.6%.

As of 2005, there were 7,700 farms in Massachusetts encompassing a total of 520,000 acres (2,100 km2), averaging 68 acres (0.28 km2) apiece.[136] Almost 2,300 of the state's 6,100 farms grossed under $2,500 in 2007.[136] Particular agricultural products of note include tobacco, livestock, and fruits, tree nuts, and berries, for which the state is nationally ranked 11th, 17th, and 16th, respectively.[136] Massachusetts is the second-largest cranberry-producing state in the union (after Wisconsin).[137]

Taxation

The overall state and local tax burden in Massachusetts ranks 11th highest in the United States.[138] Massachusetts has a flat-rate personal income tax of 5.25%,[139] after a 2002 voter referendum to eventually lower the rate to 5.0%.[140] There is an exemption for income below a threshold that varies from year to year. The corporate income tax rate is 8.8%,[138] and the short-term capital gains tax rate is 12%.[141]

The state imposes a 6.25% sales tax[138] on certain system design/computer software services[142] and retail sales of tangible personal property—except for groceries, clothing (up to $175.00), and periodicals.[143] The sales tax is charged on clothing that costs more than $175.00, for the amount exceeding $175.00.[143] All real and tangible personal property located within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is taxable unless specifically exempted by statute. Property taxes in the state were the eighth highest in the nation.[138] There is no inheritance tax and limited Massachusetts estate tax related to federal estate tax collection.[141]

Energy

Massachusetts' electricity generation market was made competitive in 1998, enabling retail customers to change suppliers without changing utility companies.[144] Though most residential customers remain with incumbent generators, most of the 4.3 billion kilowatt-hours consumed in the state in July 2011 were generated competitively.[145] In 2011, Massachusetts was ranked as the most energy efficient state in America.[146]

Transportation

Massachusetts has 10 regional metropolitan planning organizations and three non-metropolitan planning organizations covering the remainder of the state; statewide planning is handled by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation.

Rail service

Amtrak operates inter-city rail, including the high-speed Acela service to cities such as Providence, New Haven, New York City, and Washington, DC from South Station. From North Station the Amtrak Downeaster serves Portland ME, and Freeport, ME.[147]

Regional services

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) operates public transportation in the form of subway,[148] bus,[149] and ferry[150] systems in the Metro Boston area. It also operates longer distance commuter rail services throughout the larger Greater Boston area, including service to Worcester and Providence, Rhode Island.[151] As of the summer of 2013 the Cape Cod Regional Transit Authority in collaboration with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) is operating the CapeFLYER providing passenger rail service between Boston and Cape Cod.[152][153]

Fifteen other regional transit authorities provide public transportation in the form of bus services in their local communities.[154] Two heritage railways are in operation: the Cape Cod Central Railroad and the Berkshire Scenic Railway.[155][156]

As of 2006, a number of freight railroads were operating in Massachusetts, with CSX being the largest carrier. Massachusetts has a total of 1,079 miles (1,736 km) of freight trackage in operation.[157] The Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority regulates freight and passenger ferry service to the islands and operates some of those lines.[158]

Air service

The major airport in the state is Logan International Airport. The airport served over 28 million passengers in 2007 and is used by around 50 airlines.[159] Logan International Airport has service to numerous cities throughout the United States, as well as international service to Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. Logan, Hanscom Field in Bedford, and Worcester Regional Airport are operated by Massport, an independent state transportation agency.[159] Massachusetts has approximately 42 public-use airfields, and over 200 private landing spots.[160] Some airports receive funding from the Aeronautics Division of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration; the FAA is also the primary regulator.

Road

There are a total of 31,300 miles (50,400 km) of interstates and highways in Massachusetts.[161] Interstate 90, also known as the Massachusetts Turnpike, is the longest interstate in Massachusetts. The route runs 136 mi (219 km) generally west to east from the New York state line near the town of West Stockbridge and passes just north of Springfield, just south of Worcester and through Framingham before terminating near Logan International Airport in Boston. Other major interstates include Interstate 91, which runs generally north and south along the Connecticut River, Interstate 93, which runs north and south through central Boston, then passes Methuen before entering New Hampshire. Interstate 95, which follows most of the US Atlantic coastline, connects Providence, Rhode Island with Greater Boston, forming a loop around the more urbanized areas (for some distance cosigned with Route 128) before continuing north along the coast.

Interstate 495 forms a wide loop around the outer edge of Greater Boston. Other major interstates in Massachusetts include I-291, I-391, I-84, I-195, I-395, I-290, and I-190. Major non-interstate highways in Massachusetts include U.S. Routes 1, 3, 6, and 20, and state routes 2, 3, 24, and 128. A great majority of interstates in Massachusetts were constructed during the mid 20th century, and at times were controversial, particularly the routing of I-95 through central Boston. Opposition to continued construction grew, and in 1970 Governor Francis W. Sargent issued a general prohibition on most further freeway construction within the I-95/Route 128 loop in the Boston area.[162] A massive undertaking to bring I-93 underground in downtown Boston, called the Big Dig, has brought the city's highway system under public scrutiny over the last decade.[93]

Government and politics

Massachusetts has a long political history; earlier political structures included the Mayflower Compact of 1620, the separate Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies, and the combined colonial Province of Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Constitution was ratified in 1780 while the Revolutionary War was in progress, four years after the Articles of Confederation was drafted, and eight years before the present United States Constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788. Drafted by John Adams, the Massachusetts Constitution is currently the oldest functioning written constitution in continuous effect in the world.[163][164][165][166]

In recent decades, Massachusetts politics have been generally dominated by the Democratic Party, and the state has a reputation for being one of the most liberal in the country. In 1974, Elaine Noble became the first openly lesbian or gay candidate elected to a state legislature in US history.[167] The state housed the first openly gay member of the United States House of Representatives, Gerry Studds.

Government

The Government of Massachusetts is divided into three branches: Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. The governor of Massachusetts heads the executive branch; duties of the governor include signing or vetoing legislation, filling judicial and agency appointments, granting pardons, preparing an annual budget, and commanding the Massachusetts National Guard.[168] Massachusetts governors, unlike those of most other states, are addressed as His/Her Excellency.[168] The current governor is Deval Patrick, a Democrat from Milton. The executive branch also includes the Executive Council, which is made up of eight elected councilors and the Lieutenant Governor.[168]

Abilities of the Council include confirming gubanatorial appointments and certifying elections.[168] The Massachusetts House of Representatives and Massachusetts Senate comprise the legislature of Massachusetts, known as the Massachusetts General Court.[168] The House consists of 160 members while the Senate has 40 members.[168] Leaders of the House and Senate are chosen by the members of those bodies; the leader of the House is known as the Speaker while the leader of the Senate is known as the President.[168] Each branch consists of several committees.[168] Members of both bodies are elected to two-year terms.

The Judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Judicial Court, which serves over a number of lower courts.[168] The Supreme Judicial Court is made up of a chief justice and six associate justices.[168] Judicial appointments are made by the governor and confirmed by the executive council.[168]

The Congressional delegation from Massachusetts is entirely Democratic.[169][170] Currently, the US senators are Democrats Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren. The members of the state's delegation to the US House of Representatives (all Democrats) are Richard Neal, Jim McGovern, Niki Tsongas, Joseph Kennedy III, Katherine Clark, John F. Tierney, Mike Capuano, Stephen Lynch, and Bill Keating.[170]

Federal court cases are heard in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, and appeals are heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.[171] In US presidential elections, Massachusetts is allotted 11 votes in the electoral college, out of a total of 538.[172] Like most states, Massachusetts's electoral votes are granted in a winner-take-all system.[173]

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 38% 1,178,510 | 61% 1,906,319 |

| 2008 | 36% 1,108,854 | 62% 1,904,098 |

| 2004 | 37% 1,070,109 | 62% 1,803,801 |

| 2000 | 33% 878,502 | 60% 1,616,487 |

| 1996 | 28% 718,107 | 62% 1,571,763 |

| 1992 | 29% 805,049 | 48% 1,318,662 |

| 1988 | 46% 1,194,635 | 53% 1,401,416 |

Throughout the mid 20th century, Massachusetts has gradually shifted from a Republican-leaning state to one largely dominated by Democrats; the 1952 victory of John F. Kennedy over incumbent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. is seen as a watershed moment in this transformation. His younger brother Edward M. Kennedy held that seat until his death from a brain tumor in 2009.[174] Massachusetts has since gained a reputation as being a politically liberal state and is often used as an archetype of modern liberalism, hence the usage of the phrase "Massachusetts liberal".[175]

Massachusetts routinely votes for the Democratic Party, with the core concentrations in the Boston metro area, the Cape and Islands, and Western Massachusetts. Pockets of Republican strength are in the central areas along the I-495 crescent, and communities on the south and north shores,[176] but the state as a whole has not given its Electoral College votes to a Republican in a presidential election since Ronald Reagan carried it in 1984. Additionally, Massachusetts provided Reagan with his smallest margins of victory in both the 1980 and 1984 elections. In recent elections, even Scott Brown's 2010 win, Western Massachusetts is more reliably 'blue' (by city/town) than Eastern Massachusetts.

As of the 2006 election, the Republican party holds less than 13% of the seats in both legislative houses of the General Court: in the House, the balance is 141 Democratic to 19 Republican, and in the Senate, 35–5.[177]

Although Republicans held the governor's office continuously from 1991 to 2007, they have been among the more moderate Republican leaders in the nation.[178][179] In the 2004 election, Massachusetts gave native son John Kerry 61.9% of the vote, his best showing in any state.[180] In 2008, President Barack Obama carried the state with 61.8% of the vote.[181] In the 2010 special election for the U.S. Senate, Republican Scott Brown defeated Democrat Martha Coakley in a come-from-behind victory, by a 52% to 47% margin only to lose the seat in the 2012 Senate election to Elizabeth Warren, the first female senator to represent Massachusetts, on November 6, 2012.[182][183]

A number of contemporary national political issues have been influenced by events in Massachusetts, such as the decision in 2003 by the state Supreme Judicial Court allowing same-sex marriage[184] and a 2006 bill which mandated health insurance for all Bay Staters.[185] In 2008, Massachusetts voters passed an initiative decriminalizing possession of small amounts of marijuana.[186] Voters in Massachusetts also approved a ballot measure in 2012 that legalized the medical use of marijuana.[187]

Cities, towns, and counties

There are 50 cities and 301 towns in Massachusetts, grouped into 14 counties.[188] The fourteen counties, moving roughly from west to east, are Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire, Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Bristol, Plymouth, Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket. Eleven communities which call themselves "towns" are, by law, cities since they have traded the town meeting form of government for a mayor-council or manager-council form.[189]

Boston is the state capital and largest city in Massachusetts. The population of the city proper is 609,023,[190] and Greater Boston, with a population of 4,522,858, is the 10th largest metropolitan area in the nation.[191] Other cities with a population over 100,000 include Worcester, Springfield, Lowell, and Cambridge.[192] Plymouth is the largest municipality in the state by land area.[188]

Massachusetts, along with the five other New England states, features the local governmental structure known as the New England town.[193] In this structure, incorporated towns—as opposed to townships or counties—hold many of the responsibilities and powers of local government.[193] Some of the county governments were abolished by Massachusetts beginning in 1997, and their voters elect only Sheriffs and Registers of Deeds, who are part of the state government.[194] Other counties have been reorganized, and a few still retain county councils.[194]

Education

Massachusetts was the first state to require municipalities to appoint a teacher or establish a grammar school with the passage of the Massachusetts Education Law of 1647,[195] and 19th century reforms pushed by Horace Mann, founder of Westfield State University, laid much of the groundwork for contemporary universal public education.[196][197] Massachusetts is home to the country's oldest public elementary school (The Mather School, founded in 1639), oldest high school (Boston Latin School, founded in 1635),[198] oldest boarding school (The Governor's Academy, founded in 1763), oldest college (Harvard University, founded in 1636),[199] and oldest women's college (Mount Holyoke College, founded in 1837).[200]

In 1852, Massachusetts became the first state to pass compulsory school attendance laws.[201] The per-student public expenditure for elementary and secondary schools (kindergarten through grade 12) was fifth in the nation in 2004, at $11,681.[202] In 2007, Massachusetts scored highest of all the states in math on the National Assessments of Educational Progress.[203]

Massachusetts is home to 121 institutions of higher education.[204] Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, both located in Cambridge, consistently rank among the world's best universities.[205][206] In addition to Harvard and MIT, several other Massachusetts universities consistently rank in the top 40 at the national level in the widely cited rankings of U.S. News and World Report: Tufts University (#28 for 2013), Boston College (#31), and Brandeis University (#33).

Among liberal arts colleges, three of the top handful in the nation are within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts: Williams College (#1 in the liberal arts ranking of USNWR), Amherst College (#2), and Wellesley College (#6). Others regularly placing in the top 40 are Smith College (#19), College of the Holy Cross (#29), and Mount Holyoke College (also #29). According to this "granddaddy of the college rankings", roughly five (12.5%) of the top 40 research universities and six (15%) of the top 40 liberal arts colleges reside in this state that contains only 2% of the U.S. population.

The public University of Massachusetts (nicknamed UMass) features five campuses in the state, with its flagship campus in Amherst that enrolls over 25,000 students.[207][208]

Arts and culture

Massachusetts has contributed much to American arts and culture. Drawing from its Native American and Yankee roots, along with later immigrant groups, Massachusetts has produced a number of writers, artists, and musicians. A number of major museums and important historical sites are also located there, and events and festivals throughout the year celebrate the state's history and heritage.

Massachusetts was an early center of the Transcendentalist movement, which emphasized intuition, emotion, human individuality and a deeper connection with nature.[78] Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was from Boston but spent much of his later life in Concord, largely created the philosophy with his 1836 work Nature, and continued to be a key figure in the movement for the remainder of his life. Emerson's friend, Henry David Thoreau, who was also involved in Transcendentalism, recorded his year spent alone in a small cabin at nearby Walden Pond in the 1854 work Walden; or, Life in the Woods.[209]

Other famous authors and poets born or strongly associated with Massachusetts include Nathaniel Hawthorne, John Updike, Emily Dickinson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, E.E. Cummings, Sylvia Plath, and Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as "Dr. Seuss".[210][211][212] Famous painters from Massachusetts include Winslow Homer and Norman Rockwell;[212] many of the latter's works are on display at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge.[213]

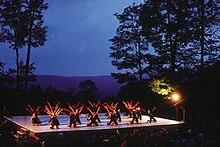

Massachusetts is also an important center for the performing arts. Both the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Boston Pops Orchestra are based in Massachusetts.[214] Other orchestras in Massachusetts include the Cape Cod Symphony Orchestra in Barnstable and the Springfield Symphony Orchestra.[215][216] Tanglewood, in western Massachusetts, is a music venue that is home to both the Tanglewood Music Festival and Tanglewood Jazz Festival, as well as the summer host for the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[217][218] Jacob's Pillow in the Berkshires hosts a number of traditional and contemporary musical and dance events.[219]

Other performing arts and theater organizations in Massachusetts include the Boston Ballet,[220] the Boston Lyric Opera,[214] and the Lenox-based Shakespeare & Company.[221] In addition to classical and folk music, Massachusetts has produced musicians and bands spanning a number of contemporary genres, such as the classic rock band Aerosmith, the proto-punk band The Modern Lovers, the New Wave band The Cars, and the alternative rock band Pixies.[222] Film events in the state include the Boston Film Festival, the Boston International Film Festival, and a number of smaller film festivals in various cities throughout Massachusetts.[223]

Massachusetts is home to a large number of museums and historical sites. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art and the DeCordova contemporary art and sculpture museum in Lincoln are all located within Massachusetts,[224][225] and the Maria Mitchell Association in Nantucket includes several observatories, museums, and an aquarium.[226] Historically themed museums and sites such as the Springfield Armory National Historic Site in Springfield,[21] Boston's Freedom Trail and nearby Minute Man National Historical Park, both of which preserve a number of sites important during the American Revolution,[21][227] the Lowell National Historical Park, which focuses on some of the earliest mills and canals of the industrial revolution in the US,[21] the Black Heritage Trail in Boston, which includes important African-American and abolitionist sites in Boston,[228] and the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park[21] all showcase various periods of Massachusetts's history.

Plimoth Plantation and Old Sturbridge Village are two open-air or "living" museums in Massachusetts, recreating life as it was in the 17th and early 19th centuries, respectively.[229][230] Boston's annual St. Patrick's Day parade and "Harborfest", a week-long Fourth of July celebration featuring a fireworks display and concert by the Boston Pops as well as a turnaround cruise in Boston Harbor by the USS Constitution,[231] are popular events. The New England Summer Nationals, an auto show in Worcester, draws tens of thousands of attendees every year.[232]

Media

There are two major television media markets located in Massachusetts. The Boston/Manchester market is the fifth largest in the United States.[233] All major networks are represented. The other market surrounds the Springfield area. WGBH-TV in Boston is a major public television station and produces national programs such as Nova, Frontline, and American Experience.[234][235]

The Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Springfield Republican, and the Worcester Telegram & Gazette are Massachusetts's largest daily newspapers.[236] In addition, there are many community dailies and weeklies. There are a number of major AM and FM stations which serve Massachusetts,[237] along with many more regional and community-based stations. Some colleges and universities also operate campus television and radio stations, and print their own newspapers.[238][239][240][241][242]

Health

Massachusetts generally ranks highly among states in most health and disease prevention categories. In 2009, the United Health Foundation ranked the state as third healthiest overall.[243] However, the study also pointed to several areas in which Massachusetts ranked below average, such as the state's rate of binge drinking, which was the 11th highest in the country.[243] Massachusetts has the most doctors per 100,000 residents,[244] the second-lowest infant mortality rate,[245] and the lowest percentage of uninsured residents (for both children as well as the total population).[246] According to Businessweek, commonwealth residents have an average life expectancy of 78.4 years, the fifth longest in the country.[247] 37.2% of the population is overweight and 21.7% is obese,[248] and Massachusetts ranks sixth highest in the percentage of residents who are considered neither obese nor overweight (41.1%).[248]

The nation's first Marine Hospital was erected by federal order in Boston in 1799.[249][250] The Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine lists a total of 132 hospitals in the state.[251] According to rankings by US News & World Report, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston is the top ranked overall hospital in the nation;[252] the hospital also ranked in the top ten in fifteen specialties.[253] Massachusetts General was founded in 1811 and serves as the largest teaching hospital for nearby Harvard University.[254]

Other teaching and medical institutions affiliated with Harvard include Brigham and Women's Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, among others.[255] Boston is also the location of New England Baptist Hospital, Tufts Medical Center, and Boston Medical Center, the latter of which is the primary teaching hospital for Boston University.[256] The University of Massachusetts Medical School is located in Worcester.[257] The Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences has campuses in both Boston and Worcester.[258]

Sports and recreation

Organized sports

The Olympic sports of basketball and volleyball were invented in Western Massachusetts (in Springfield at Springfield College and Holyoke, respectively). The Basketball Hall of Fame, a shrine to the sport's history, is a major tourist destination in the City of Springfield. The Volleyball Hall of Fame is located in Holyoke.[259]

Massachusetts has a long history with amateur athletics and professional teams. Most of the major professional teams have won multiple championships in their respective leagues. Massachusetts teams have won six Stanley Cups (Boston Bruins),[260] seventeen NBA Championships (Boston Celtics),[261] three Super Bowls (New England Patriots),[262] and nine World Series (eight for the Boston Red Sox, one for the Boston Braves).[263] The American Hockey League (AHL), the NHL's development league, is headquartered in Springfield. Other professional sports teams in Massachusetts include the Springfield Falcons AHL team, the Worcester Sharks AHL team, and the Springfield Armor NBA Development League team.

Massachusetts is also the home of the Cape Cod Baseball League, rowing events such as the Eastern Sprints on Lake Quinsigamond in Worcester and the Head of the Charles Regatta,[264][265] and the Boston Marathon.[266] A number of major golf events have taken place in Massachusetts, including nine U.S. Opens and two Ryder Cups, among others.[267][268][269] The New England Revolution is the Major League Soccer team in Massachusetts,[270] and the Boston Cannons are the Major League Lacrosse team.[271] The Boston Breakers are the Women's Professional Soccer in Massachusetts.

A gymnastics center called Brestyan's American Gymnastics has also become well known in the competitive gymnastics world[by whom?] in the last decade for producing several internationally successful gymnasts like Olympic silver medalist and vault world champion Alicia Sacramone, 2011 world champion and two time Olympic Gold medalist Aly Raisman, and Canadian national team member Talia Chiarelli.

Several universities in Massachusetts are notable for their collegiate athletics. Boston College fields teams in the nationally televised Atlantic Coast Conference, while Harvard University competes in the famed Ivy League. Boston University, Northeastern University, College of the Holy Cross, UMass Lowell, and UMass Amherst also participate in Division I athletics.[272][273] Many other Massachusetts colleges compete in lower divisions such as Division III, where MIT, Tufts University, Amherst College, Williams College, and others field competitive teams.

Outdoor recreation

Long-distance hiking trails in Massachusetts include the Appalachian Trail, the New England National Scenic Trail, the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, the Midstate Trail, and the Bay Circuit Trail.[274][275] Other outdoor recreational activities in Massachusetts include sailing and yachting, freshwater and deep-sea fishing,[276] whale watching,[277] downhill and cross-country skiing,[278] and hunting.

See also

Notes

- ^ The Constitution of the Vermont Republic, adopted in 1777, represented the first partial ban on slavery. Vermont became a state in 1791, but did not fully ban slavery until 1858 with the Vermont Personal Liberty Law. The Pennsylvania Gradual Abolition Act of 1780[67] made Pennsylvania the first state to abolish slavery by statute.[68]

References

- ^ a b c d "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013" (CSV). 2013 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 30, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "50 States". Net state. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica" (online ed.).

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "A Colorful Battle Is Lodge vs. Curley". The Milwaukee Journal. October 18, 1936. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

One of the Codfish State...

- ^ "Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 2, Section 35: Designation of citizens of commonwealth". The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- ^ "Collections". Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. 1877: 435.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jones, Thomas (1879). DeLancey, Edward Floyd (ed.). History of New York During the Revolutionary War. New York: New York Historical Society. p. 465.

- ^ wiktionary:Massachusettsian.

- ^ a b c "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density (geographically ranked by total population): 2000". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 30, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Greylock RM 1 Reset". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 21, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ Levenson, Michael (August 9, 2006). "Can you guess the state sport of Massachusetts?". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Tooker, William Wallace (1904). Algonquian Names of some Mountains and Hills.

- ^ Salwen, Bert, 1978. Indians of Southern New England and Long Island: Early Period. In "Northeast", ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of "Handbook of North American Indians", ed. William C. Sturtevant, pp. 160–76. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. Quoted in: Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 401

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 270

- ^ "East Squantum Street (Moswetuset Hummock)". Quincy, Mass. Historical and Architectural Survey. Thomas Crane Public Library. 1986. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Neal, Daniel (1747). "XIV: The Present State of New England". The history of New-England. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). London: A. Ward. p. 216. OCLC 8616817. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ "Part One: Concise Facts – Name". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Kentucky as a Commonwealth". Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Massachusetts". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts State Parks". Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Trail Maps". Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Getting Wet!". Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "A Short Introduction to Terrestrial Biomes". Nearctica. Retrieved October 17, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Stocker, Carol (November 17, 2005). "Old growth, grand specimens drive big-tree hunters". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "Current Research — Working Landscapes". The Center for Rural Massachusetts — The University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Massachusetts Forests". MassWoods Forest Conservation Program — The University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved March 19, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Northeastern Coastal Zone — Ecoregion Description". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c "State Mammal List". Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "Peregrine Falcon" (PDF). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Eastern Coyote in Massachusetts". Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Wild Turkey in Massachusetts" (PDF). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Moose in Massachusetts". Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Black Bears in Massachusetts". Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Atlantic Flyway". University of Nebraska. Retrieved May 22, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Common Loon" (PDF). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "Telemetry Research:Long-Tailed Ducks". Mass Audubon. Retrieved May 28, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Roseate Tern" (PDF). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "Coastal Waterbird Program". Mass Audubon. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge – Wildlife and Habitat". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved May 26, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Best Bets for Fishing". Massachusetts Division of Wildlife & Fisheries. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "Species Profiles". Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b "Origin & Early Mohican History". Stockbridge-Munsee Community — Band of Mohican Indians. Retrieved October 21, 2009.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick E (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-395-66921-1. OCLC 34669430. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ Marr, JS; Cathey, JT (February 2010). "New hypothesis for cause of an epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619". Emerging Infectious Disease. doi:10.3201/e0di1602.090276.

- ^ Koplow 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 30–32.

- ^ William Pynchon. Bio.umass.edu. Retrieved on September 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Goldfield et al. 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 50.

- ^ "John Fraylor. Salem Maritime National Historic Park". Nps.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ^ "Historic Earthquakes". USGS. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Memorandum". Boston Gazette. November 24, 1755. p. 1.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 63–83.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, pp. 96–97.

- ^ "Massachusetts Legal Holidays". Secretary of the Commonwealth. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "John Adams" (biography). National Park Service. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts Constitution, Judicial Review, and Slavery – The Quock Walker Case". Massachusetts Judicial Branch. 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ "Explore PA history".

- ^ "Visitor information". PA, US: Legislature.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Shays Rebellion". National Park Service. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "The Ratification of the U.S. Constitution in Massachusetts". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Statehood". History. Maine: Senate. Retrieved April 11, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 129.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 211.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 202.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 133–36.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 179.

- ^ Goldfield et al. 1998, p. 251.

- ^ a b c Goldfield et al. 1998, p. 254.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 185.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 187–93.

- ^ "Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment". National Park Service. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ "Augustus Saint-Gaudens". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved October 19, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Brown and Tager, p. 246.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 276.

- ^ "Job Loss, Shrinking Revenues, and Grinding Decline in Springfield, Massachusetts: Is A Finance Control Board the Answer?" (PDF). UML.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.111

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 275–83.

- ^ a b Brown & Tager 2000, p. 284.

- ^ "Biography: Edward Moore Kennedy". American Experience. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "The Kennedys: A Family Tree". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "Kennedy Compound". National Park Service. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Grunwald, Michael. Dig the Big Dig [1] The Washington Post. August 6, 2006. . Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ a b "The Big Dig". Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 31, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Same Sex Marriage: A Selective Bibliography". Law-library.rutgers.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "Population: 1790 to 1990" (PDF). US: census.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Resident Population of the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico". US: Census. 2000.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "2010 Data". US: Census. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ "Population and Population Centers by State: 2000" (plain text). United States: Census Bureau, Deparatment of Commerce. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ a b c Mishra, Raja (December 22, 2006). "State's population growth on stagnant course". Boston Globe. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ "Experts say housing costs, schools key to job creation in Massachusetts". The MetroWest Daily News. Framingham, MA.

- ^ Levenson, Michael (December 10, 2006). "Bay state's labor force diminishing". Boston Globe. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Bayles, Fred (March 21, 2001). "Minorities account for state population growth". USA Today. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ "Language Map Data Center". Modern Language Association. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Massachusetts QuickFacts". US: Census Bureau.

- ^ "Fact finder". US: Census.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States

- ^ Population of Massachusetts: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts[dead link]

- ^ 2010 Census Data

- ^ "Massachusetts – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1790 to 1990". US: Census Bureau.

- ^ Exner, Rich (June 3, 2012). "Americans under age 1 now mostly minorities, but not in Ohio: Statistical Snapshot". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 173.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 173–79.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 203.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 301.

- ^ "Imagine all the people: Haitian immigrants in Boston" (PDF). Boston Development Authority. Retrieved May 30, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Whaling Industry and Portuguese Immigration Centered in New Bedford, Mass". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Brettell 2003, pp. xii–xiv.

- ^ Schweitzer, Sarah (February 15, 2010). "Lowell hopes to put 'Little Cambodia' on the map". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ "Wampanoag Tribe Receives Federal Recognition". WBZ-TV. Boston, MA. Associated Press. Retrieved February 20, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Weber, David (February 15, 2007). "Mashpee Wampanoag Indians receive federal recognition". The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 20, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 180–82.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 257–58.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, pp. 300–4.

- ^ a b "Massachusetts". Modern Language Association. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "About Unitarian Universalism". Blue Hills Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "American Religious Identification Survey" (JPEG). Exhibit 15 (image). New York: The Graduate Center, City University. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ Butterfield, Fox (May 14, 1989). "The Perfect New England Town". The New York Times. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product by State". Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "State Personal Income 2008" (PDF). Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Fortune 500 – States". CNN. July 27, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "America's Top States for Business 2010" (special report) (1) (Web ed.). CNBC. May 9, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ Frank, Robert. "Top states for millionaires per capita". CNBC. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Mass. unemployment rate falls to 6.0% in March, down from 6.9% in February". Boston Globe. June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c "2009 State Agriculture Overview (Massachusetts)" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts Cranberries" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. January 26, 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Massachusetts". The Tax Foundation. Retrieved May 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Mass. income tax rate cut by .05 percent". Yahoo. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ^ "Massachusetts Implements Reduction in Personal Income Tax Rates". The Tax Foundation. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ^ a b "Tax Rates". Massachusetts Department of Revenue. Retrieved May 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "TIR 13-10: Sales and Use Tax on Computer and Software Services Law Changes Effective July 31, 2013". Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "A Guide to Sales and Use Tax". MA, US: Department of Revenue. Retrieved May 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Electricity deregulation". Good Energy.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Electric deregulation" (XLS).[dead link]

- ^ Shen, Andrew (October 25, 2011). "Massachusetts Passes California As The Most Energy Efficient State". Business insider. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "Acela Express". Routes. Amtrak. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Subway Map". Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Bus Schedules & Maps". Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Boat Map and Schedules". Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Commuter Rail Maps and Schedules". Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "CapeFlyer". Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ "T announces summer Cape Cod train service". WCVB-TV. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ "Your Transit Authorities". Massachusetts Association of Regional Transit Authorities. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Cape Cod Central Railroad". Cape Cod Central Railroad. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Scenic Train Schedule". Berkshire Scenic Railway Museum. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Railroad Service in Massachusetts" (PDF). Association of American Railroads. Retrieved June 2, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Background". The Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Who We Are". Massachusetts Port Authority. Retrieved May 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Massa aeronautics".

- ^ "Transportation". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Brown and Tager, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Levy, Leonard (1995). Seasoned Judgments: The American Constitution, Rights, and History. p. 307.

- ^ Kemp, Roger (2010). Documents of American Democracy. p. 59.

- ^ Murrin, John (2011). Liberty, Power, and Equality: A History.

- ^ "John Adams and the Massachusetts Constitution". Massachusetts Judicial Branch, mass.gov. 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ Gianoulis, Tina (October 13, 2005). "Noble, Elaine". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Massachusetts Facts: Politics". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Members of the 111th Congress". United States Senate. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "Massachusetts Congressional Districts" (PDF). Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth. Retrieved October 18, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Geographic Boundaries of United States Courts of Appeals and United States District Courts" (PDF). US: Courts. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "2008 Presidential Election". Electoral College. US: Archives. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Electoral College. US: Archives. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Page, Susan; Lawrence, Jill (July 11, 2004). "Does 'Massachusetts liberal' label still matter?". USA Today. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "Mapping MA election results". R bloggers.

- ^ "State Vote 2006: Election Profile, Massachusetts". State Legislatures Magazine. National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved November 17, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Gordon, Meryl (January 14, 2002). "Weld at Heart". New York. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Vennochi, Joan (June 17, 2007). "Romney's liberal shadow". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Federal Elections 2004" (PDF). Federal Election Commission: 22. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "2008 Presidential Popular Vote Summary" (PDF). Federal Election Commission. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Bloch, Matthew; Cox, Amanda; Ericson, Matthew; Hossain, Farhana; Tse, Archie (January 19, 2010). "Interactive Map, Election Results and Analysis". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Fiery consumer advocate Elizabeth Warren beats Scott Brown in Massachusetts Senate race". November 6, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Same-sex couples ready to make history in Massachusetts". CNN. May 17, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Massachusetts Makes Health Insurance Mandatory". National Public Radio. July 3, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "2008 Return of Votes Complete" (PDF). Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth. December 17, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "Massachusetts voters approve ballot measure to legalize medical marijuana". NY Times Co. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ a b "Information and Historical Data on Cities, Towns, and Counties in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ See Administrative divisions of Massachusetts#The city/town distinction.