Medical cannabis

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), as medical therapy to treat disease or alleviate symptoms. The Cannabis plant has a history of medicinal use dating back thousands of years across many cultures.[1]

Cannabis has been used to reduce nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy and people with AIDS, and to treat pain and muscle spasticity;[2] its use for other medical applications has been studied, but there is insufficient data for conclusions about safety and efficacy. Short-term use increases minor adverse effects, but does not appear to increase major adverse effects.[3] Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear,[3] and there are safety concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk for dependence and the risk of children taking it by accident.[2]

Medical cannabis can be administered using a variety of methods, including vaporizing or smoking dried buds, eating extracts, and taking capsules. Synthetic cannabinoids are available as prescription drugs in some countries; examples include: dronabinol (available in the United States (US) and Canada) and nabilone (available in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom (UK), and the US). Recreational use of cannabis is illegal in most parts of the world, but the medical use of cannabis is legal in certain countries, including Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. In the US, federal law outlaws all cannabis use, while 20 states and the District of Columbia have decided they are no longer willing to prosecute individuals merely for the possession or sale of marijuana, as long as the individuals are in compliance with the state's marijuana sale regulations. However, an appeals court ruled in January 2014 that a 2007 Ninth Circuit ruling remains binding in relation to the ongoing illegality, in federal legislative terms, of Californian cannabis dispensaries, reaffirming the impact of the federal Controlled Substances Act.[4]

Medical uses

Medical cannabis has several potential beneficial effects.[5][6] Cannabinoids can serve as appetite stimulants, antiemetics, antispasmodics, and have some analgesic effects,[1] may be helpful treating chronic non-cancerous pain, or vomiting and nausea caused by chemotherapy. The drug may also aid in treating symptoms of AIDS patients.[citation needed]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved smoked cannabis for any condition or disease as it deems evidence is lacking concerning safety and efficacy of cannabis for medical use.[7] The FDA issued an 2006 advisory against smoked medical cannabis stating; "marijuana has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and has a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision."[7] The National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA states that "Marijuana itself is an unlikely medication candidate for several reasons: (1) it is an unpurified plant containing numerous chemicals with unknown health effects; (2) it is typically consumed by smoking further contributing to potential adverse effects; and (3) its cognitive impairing effects may limit its utility".[8]

The Institute of Medicine, run by the United States National Academy of Sciences, conducted a comprehensive study in 1999[needs update] assessing the potential health benefits of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids. The study concluded that smoking cannabis is not to be recommended for the treatment of any disease condition, but that nausea, appetite loss, pain and anxiety can all be mitigated by cannabis. While the study expressed reservations about smoked cannabis due to the health risks associated with smoking, the study team concluded that until another mode of ingestion was perfected providing the same relief as smoked cannabis, there was no alternative. In addition, the study pointed out the inherent difficulty in marketing a non-patentable herb, as pharmaceutical companies will likely make smaller investments in product development if the result is not patentable. The Institute of Medicine stated that there is little future in smoked cannabis as a medically approved medication, while in the report also concluding that for certain patients, such as the terminally ill or those with debilitating symptoms, the long-term risks are not of great concern.[9][10] Citing "the dangers of cannabis and the lack of clinical research supporting its medicinal value" the American Society of Addiction Medicine in March 2011 issued a white paper recommending a halt on use of marijuana as medication in the U.S., even in states where it had been declared legal.[11][12]

Nausea and vomiting

Medical cannabis is somewhat effective in chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)[2] and may be a reasonable option in those who do not improve following preferential treatment.[13] Comparative studies have found cannabinoids to be more effective than some conventional antiemetics such as prochlorperazine, promethazine, and metoclopramide in controlling CINV,[14] but there are used less frequently because of side effects including dizziness, dysphoria, and hallucinations.[3][15] Long-term cannabis use may cause nausea and vomiting, a condition known as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.[16]

A 2010 Cochrane review said that cannabinoids were "probably effective" in treating chemotherapy-induced nausea in children, but with a high side effect profile (mainly drowsiness, dizziness, altered moods, and increased appetite). Less common side effects were "occular problems, orthostatic hypotension, muscle twitching, pruritis, vagueness, hallucinations, lightheadedness and dry mouth".[17]

HIV/AIDS

Evidence is lacking for both efficacy and safety of cannabis and cannabinoids in treating patients with HIV/AIDS or for anorexia associated with AIDS; studies as of 2013 suffer from effects of bias, small sample size, and lack of long-term data.[18]

Pain

Cannabis appears to be somewhat effective in treatment of chronic pain, including pain caused by neuropathy and possibly also that due to fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis.[19][20] A 2009 review states it was unclear if the benefits were greater than the risks,[19] while a 2011 review considered it generally safe for this use.[20] In palliative care the use appears safer than that of opioids.[21]

Multiple sclerosis

Studies of the efficacy of cannabis in treating multiple sclerosis have produced varying results. The combination of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) extracts give subjective relief of spasticity, though objective post-treatment assessments do not reveal significant changes.[22] A trial of cannabis is deemed to be a reasonable option if other treatments have not been effective.[2] Its use for MS is approved in ten countries.[2][23] A 2012 review found no problems with tolerance, abuse or addiction.[24]

Adverse effects

A 2013 literature review said that exposure to marijuana had biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and was "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature".[25] There are insufficient data to draw strong conclusions about the safety of medical cannabis, although short-term use is associated with minor adverse effects such as dizziness. Although supporters of medical cannabis say that it is safe,[26] further research is required to assess the long-term safety of its use.[3][27]

Pharmacology

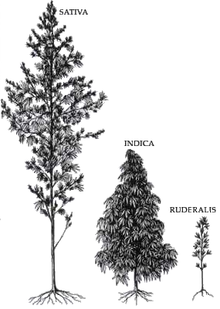

The genus Cannabis contains two species which produce useful amounts of psychoactive cannabinoids: Cannabis indica and Cannabis sativa, which are listed as Schedule I medicinal plants in the US;[2] a third species, Cannabis ruderalis, has few psychogenic properties.[2] Cannabis contains more than 460 compounds;[1] at least 80 of these are cannabinoids[28][29] – chemical compounds that interact with cannabinoid receptors in the brain.[2] As of 2012, more than 20 cannabinoids were being studied by the U.S. FDA.[30]

The most psychoactive cannabinoid found in the cannabis plant is tetrahydrocannabinol (or delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, commonly known as THC).[1] Other cannabinoids include delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol (CBD), cannabinol (CBN), cannabicyclol (CBL), cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabigerol (CBG); they have less psychotropic effects than THC, but may play a role in the overall effect of cannabis.[1] The most studied are THC, CBD and CBN.[25]

Methods of consumption

Smoking is the means of administration of cannabis for many consumers,[31] and the most common method of medical cannabis consumption in the US as of 2013.[2] It is difficult to predict the pharmacological response to cannabis because concentration of cannabinoids varies widely as there are different ways of preparing cannabis for consumption (smoked, applied as oils, eaten, or drunk) and a lack of production controls.[2] The potential for adverse effects from smoke inhalation makes smoking a less viable option than oral preparations.[31]

Cannabis vaporizers have gained popularity because of the perception among users that less harmful chemicals are ingested when components are inhaled via aerosol rather than smoke.[2]

Cannabinoid medicines are available in pill form (dronabinol and nabilone) and liquid extracts formulated into an oromucosal spray (nabiximols).[2] Oral preparations are "problematic due to the uptake of cannabinoids into fatty tissue, from which they are released slowly, and the significant first-pass liver metabolism, which breaks down Δ9THC and contributes further to the variability of plasma concentrations".[31]

Cannabinoid compounds

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, was identified in the 1960s as the cannabinoid primarily responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabis;[2] in the 1990s, after the discovery of the cannabinoid receptors CB1[1] and CB2, researchers began to study and better understand how cannabinoids acted on these receptors.[2] THC is associated – more than any other cannabinoid – with most of the pharmacologic effects of cannabis.[2]

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a major constituent of medical cannabis; it is a nonpsychotropic and how it works on brain receptors is not known.[2] CBD represents up to 40% of extracts of Cannabis sativa.[32] A 2007 review said CBD had shown potential to relieve convulsion, inflammation, cough, congestion and nausea, and to inhibit cancer cell growth.[33] Preliminary studies have also shown potential over psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, and psychosis.[32] Because cannabidiol relieves the aforementioned symptoms, cannabis strains with a high amount of CBD may benefit people with multiple sclerosis or frequent anxiety attacks.[22][33]

Cannabinol (CBN) is a product of THC and has mild psychtropic effects.[25]

Botanical strains

Cannabis indica produces a higher level of cannabidiol (abbreviated CBD) relative to THC (the primary psychoactive component in medical and recreational cannabis). Cannabis sativa, on the other hand, produces a higher level of THC relative to CBD.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Medical use of sativa is associated with a cerebral high, and many patients experience stimulating effects. For this reason, sativa is often used for daytime treatment. It may cause more of a euphoric, "high" sensation, and tends to stimulate hunger, making it potentially useful to patients with eating disorders or anorexia. Sativa also exhibits a higher tendency to induce anxiety and paranoia, so patients prone to these effects may limit treatment with pure sativa, or choose hybrid strains.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Cannabis indica is associated with sedative effects and is often preferred for night time use, including for treatment of insomnia.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Indica is also associated with a more "stoned" or meditative sensation than the euphoric, stimulating effects of sativa, possibly because of a higher CBD-to-THC ratio.[medical citation needed]

Many strains of cannabis are currently cultivated for medical use, including strains of both species in varying potencies, as well as hybrid strains designed to incorporate the benefits of both species. Hybrids commonly available can be heavily dominated by either Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica, or relatively balanced, such as so-called "50/50" strains.[citation needed]

Cannabis strains with relatively high CBD-to-THC ratios, usually indica-dominant strains, are less likely to induce anxiety. This may be due to CBD's receptor antagonistic effects at the cannabinoid receptor, compared to THC's partial agonist effect. CBD is also a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, which may also contribute to an anxiolytic effect. This likely means the high concentrations of CBD found in Cannabis indica mitigate the anxiogenic effect of THC significantly.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Pharmacologic products

In the U.S., the FDA has approved two oral cannabinoids for use as medicine: dronabinol and nabilone.[2] Dronabinol, synthetic THC, is listed as Schedule III, meaning it has some potential for dependence, and nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, is Schedule II, indicating high potential for side effects and addiction.[30] Nabiximols, an oromucosal spray derived from two strains of Cannabis sativs and containing THC and CBD,[30] is not approved in the U.S., but is approved in several European countries, Canada, and New Zealand as of 2013.[2]

| Generic medication |

Trade name(s) |

Country | Licensed indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nabilone | Cesamet | U.S., Canada | Antiemetic (treatment of nausea or vomiting) associated with chemotherapy that has failed to respond adequately to conventional therapy[2] |

| Dronabinol | Marinol | U.S., Canada | Antiemetic (treatment of nausea or vomiting) associated with chemotherapy that has failed to respond adequately to conventional therapy[2] |

| U.S. | Anorexia associated with AIDS–related weight loss[2] | ||

| Nabiximols | Sativex | Canada, New Zealand, eight European countries as of 2013 |

Limited treatment for spasticity and neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis and intractable cancer pain.[2] |

As an antiemetic, these medications are usually used when conventional treatment for nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy fail to work.[2]

Nabiximols is used for treatment of spasticity associated with MS when other therapies have not worked, and when an initial trial demonstrates "meaningful improvement".[2] Trials for FDA approval in the U.S. are underway.[2] It is also improved in several European countries for overactive bladder and vomiting.[30] When sold as Savitex as a mouth spray, the prescribed daily dose in Sweden delivers a maximum of 32.4 mg of THC and 30 mg of CBD; mild to moderate dizziness is common during the first few weeks.[34]

Relative to inhaled consumption, peak concentration of oral THC is delayed, and it may be difficult to determine optimal dosage because of variability in patient aborption.[2]

History

Ancient

Cannabis, called má 麻 (meaning "hemp; cannabis; numbness") or dàmá 大麻 (with "big; great") in Chinese, was used in Taiwan for fiber starting about 10,000 years ago.[35] The botanist Li Hui-Lin wrote that in China, "The use of Cannabis in medicine was probably a very early development. Since ancient humans used hemp seed as food, it was quite natural for them to also discover the medicinal properties of the plant."[36] Emperor Shen-Nung, who was also a pharmacologist, wrote a book on treatment methods in 2737 BCE that included the medical benefits of cannabis. He recommended the substance for many ailments, including constipation, gout, rheumatism, and absent-mindedness.[37] Cannabis is one of the 50 "fundamental" herbs in traditional Chinese medicine.[38]

The Ebers Papyrus (ca. 1550 BCE) from Ancient Egypt describes medical cannabis.[39] The ancient Egyptians used hemp (cannabis) in suppositories for relieving the pain of hemorrhoids.[40]

Surviving texts from ancient India confirm that cannabis' psychoactive properties were recognized, and doctors used it for treating a variety of illnesses and ailments, including insomnia, headaches, gastrointestinal disorders, and pain, including during childbirth.[41]

The Ancient Greeks used cannabis to dress wounds and sores on their horses,[42] and in humans, dried leaves of cannabis were used to treat nose bleeds, and cannabis seeds were used to expel tapeworms.[42]

In the medieval Islamic world, Arabic physicians made use of the diuretic, antiemetic, antiepileptic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic properties of Cannabis sativa, and used it extensively as medication from the 8th to 18th centuries.[43]

Modern

An Irish physician, William Brooke O'Shaughnessy, is credited with introducing the therapeutic use of cannabis to Western medicine, to help treat muscle spasms, stomach cramps or general pain.[44]

Albert Lockhart and Manley West began studying in 1964 the health effects of traditional cannabis use in Jamaican communities. They developed, and in 1987 gained permission to market, the pharmaceutical Canasol: one of the first cannabis extracts.[45]

In the 1970s, a synthetic version of THC was produced and approved for use in the United States as the drug Marinol.[46]

Voters in eight US states showed their support for cannabis prescriptions or recommendations given by physicians between 1996 and 1999,[needs update] including Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, going against policies of the federal government.[47]

Society and culture

Methods of acquisition

The method of obtaining medical cannabis varies by region and by legislation. In the US, most consumers grow their own or buy it from dispensaries in the states and the District of Columbia which permit the use of medical cannabis.[2]

The authors of report on a 2011 survey of medical cannabis users say that critics have suggested that some users "game the system" to obtain medical cannabis ostensibly for treatment of a condition, but then use it for nonmedical purposes – though the truth of this claim is hard to measure.[48] The report authors suggested rather that medical cannabis users occupied a "continuum" between medical and nonmedical use.[48]

Marijuana vending machines for selling or dispensing cannabis are in use in the United States and are planned to be used in Canada.[49]

Programs

As of 2011, 16 US states and the District of Columbia have public medical cannabis programs, but its use remains illegal by federal law.[23][needs update] In 1978 the US government created a program called the Compassionate Investigational New Drug program which dispenses cannabis cigarettes to 20 people with debilitating conditions[1] including glaucoma and a rare bone disease.[citation needed] The program was "closed to new candidates in 1991",[1] but as of 2013, allowed four people previously in the program to continue receiving medical cannabis.[citation needed]

National and international regulations, classification and patent

Medical use of cannabis or preparation containing THC as the active substance is legalized in Austria, Belgium, Canada, Belgium, Finland, Israel, Netherlands, Spain, the UK and some states in the US, although it is illegal under US federal law.

Cannabis is in Schedule IV of the United Nations' Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, making it subject to special restrictions. Article 2 provides for the following, in reference to Schedule IV drugs:[51]

A Party shall, if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare, prohibit the production, manufacture, export and import of, trade in, possession or use of any such drug except for amounts which may be necessary for medical and scientific research only, including clinical trials therewith to be conducted under or subject to the direct supervision and control of the Party.

The convention thus allows countries to outlaw cannabis for all non-research purposes but lets nations choose to allow medical and scientific purposes if they believe total prohibition is not the most appropriate means of protecting health and welfare. The convention requires that states that permit the production or use of medical cannabis must operate a licensing system for all cultivators, manufacturers and distributors and ensure that the total cannabis market of the state shall not exceed that required "for medical and scientific purposes."[51]

A number of medical organizations have endorsed reclassification of marijuana to allow for further study. These include, but are not limited to:

- The American Medical Association[52][53][54]

- The American College of Physicians – America's second largest physicians group[55]

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society – America's second largest cancer charity[56]

- American Academy of Family Physicians opposes the use of marijuana except under medical supervision[57]

Other medical organizations recommend a halt to using marijuana as a medicine in U.S.

The National Institutes of Health holds a US patent for medical cannabis.[50] The patent is entitled "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants" and was issued in October 2003.[58]

Research

The Schedule I classification of cannabis in the US makes the study of medical cannabis difficult.[2] Another issue for research is the habit to mix cannabis with tobacco or switch between tobacco and cannabis.

Anecdotal evidence and pre-clinical research has suggested that cannabis or cannabinoids may be beneficial for treating Huntington's disease or Parkinson's disease, but follow-up studies of people with these conditions has not produced good evidence of therapeutic potential.[59] A 2001 paper argued that cannabis had properties that made it potentially applicable to the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and on that basis research on this topic should be permitted, despite the legal difficulties of the time.[60]

A 2005 review and meta-analysis said that bipolar disorder was not well-controlled by existing medications and that there were "good pharmacological reasons" for thinking cannabis had therapeutic potential, making it a good candidate for further study.[61]

Cannabinoids have been proposed for the treatment of primary anorexia nervosa, but have no measurable beneficial effect.[62] The authors of a 2003 paper argued that cannabinoids might have useful future clinical applications in treating digestive diseases.[63] Laboratory experiments have shown that cannabinoids found in marijuana may have analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects.[64]

Cancer

Cannabinoids have shown some promise as anti-cancer therapies.[65] Laboratory experiments have suggested that cannabis and cannabinoids have anticarcinogenic, antitumor and anticancer effects,[66] including a potential effect on breast and lung cancer cells.[64] The National Cancer Institute reports that as of November 2013[update] there have been no trials on the use of cannabis to treat cancer in people, and only one small trial using delta-9-THC.[67] Although there is a large and growing volume of research, claims that there is evidence showing that cannabis cures cancer are, according to Cancer Research UK, "highly misleading", and prevalent on the internet.[68]

There is no firm evidence than cannabis helps reduce the risk of getting cancer; whether it increases the risk is difficult to establish, since most users combine its use with tobacco smoking, and this complicates research.[68]

Dementia

Cannabinoids have been proposed as having the potential for lessening the effects of Alzheimer's disease.[69] A 2012 review of the effect of cannabinoids on brain ageing found that "clinical evidence regarding their efficacy as therapeutic tools is either inconclusive or still missing".[70] A 2009 Cochrane review said that the "one small randomized controlled trial [that] assessed the efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of dementia ... [had] ... poorly presented results and did not provide sufficient data to draw any useful conclusions".[71]

Diabetes

There is emerging evidence that cannabidiol may help slow cell damage in diabetes mellitus type 1.[72] There is a lack of meaningful evidence of the effects of medical cannabis use on people with diabetes; a 2010 review concluded that "the potential risks and benefits for diabetic patients remain unquantified at the present time".[73]

Epilepsy

A 2012 Cochrane review said there is not enough evidence to draw conclusions about the safety or efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy.[74] There have been few studies of the anticonvulsive properties of CBD and epileptic disorders. The major reasons for the lack of clinical research have been the introduction of new synthetic and more stable pharmaceutical anticonvulsants, the recognition of important adverse effects and the legal restriction to the use of cannabis-derived medicines.[75] Epidiolex, a cannabis-based product developed by GW Pharmaceuticals for experimental treatment of epilepsy, will undergo stage-two trials in the US in 2014.[76]

Glaucoma

The American Glaucoma Society noted that while cannabis can help lower intraocular pressure, it recommended against its use because of "its side effects and short duration of action, coupled with a lack of evidence that it use alters the course of glaucoma."[77] As of 2008 relatively little research had been done concerning effects of cannabinoids on the eye.[78]

Tourette syndrome

A 2007 review of the history of medical cannabis said cannabinoids showed potential therapeutic value in treating Tourette syndrome (TS).[79] A 2005 review said that controlled research on treating TS with Marinol showed the patients taking the pill had a beneficial response without serious adverse effects;[80] a 2000 review said other studies had shown that cannabis "has no effects on tics and increases the individuals inner tension".[81]

A 2009 Cochrane review examined the two controlled trials to date using cannabinoids of any preparation type for the treatment of tics or TS (Muller-Vahl 2002, and Muller-Vahl 2003). Both trials compared delta-9-THC; 28 patients were included in the two studies (8 individuals participated in both studies).[31] Both studies reported a positive effect on tics, but "the improvements in tic frequency and severity were small and were only detected by some of the outcome measures".[31] The sample size was small and a high number of individuals either dropped out of the study or were excluded.[31] The original Muller-Vahl studies reported individuals who remained in the study; patients may drop out when adverse effects are too high or efficacy is not evident.[31] The authors of the original studies acknowledged few significant results after Bonferroni correction.[31]

Cannabinoid medication might be useful in the treatment of the symptoms in patients with TS,[31] but the 2009 review found that the two relevant studies of cannibinoids in treating tics had attrition bias, and that there was "not enough evidence to support the use of cannabinoids in treating tics and obsessive compulsive behaviour in people with Tourette's syndrome".[31]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ben Amar M (2006). "Cannabinoids in medicine: a review of their therapeutic potential" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology (Review). 105 (1–2): 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. PMID 16540272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (February 2013). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy (Review). 33 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1002/phar.1187. PMID 23386598.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Wang T, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ware MA (June 2008). "Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review". CMAJ (Review). 178 (13): 1669–78. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071178. PMC 2413308. PMID 18559804.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bob Egelko (15 January 2014). "Court upholds crackdown on pot dispensaries". SFGate. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Joseph W. Jacob; Joseph W. Jacob B. a. M. P. a. (2009). Medical Uses of Marijuana. Trafford Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4269-1540-6.

- ^ Aggarwal SK, Carter GT, Sullivan MD; et al. (2009). "Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: Historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions". Journal of opioid management (Review, historical article). 5 (3): 153–68. PMID 19662925.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Inter-agency advisory regarding claims that smoked marijuana is a medicine" (Press release). fda.gov. 2006-04-20. Retrieved 2012-12-24 Template:Inconsistent citations.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nida: Marijuana, An update from the National Institute on Drug Abuse". Nida.nih.gov. February 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] [needs update] Watson SJ, Benson JA Jr, Joy JE (2000). "Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base: a summary of the 1999 Institute of Medicine report". Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (6): 547–52. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.547. PMID 10839332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [needs update] Joy JE, Watson SJ, Benson JA, ed. (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-07155-0. OCLC 246585475. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b "American Society of Addiction Medicine Rejects Use of 'Medical Marijuana,' Citing Dangers and Failure To Meet Standards of Patient Care, March 23, 2011" (Press release). Maryland. PR Newswire. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Medical Marijuana, American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2010". Asam.org. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2011.[dead link]

- ^ [conflicted source?] Grotenhermen F, Müller-Vahl K (July 2012). "The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 109 (29–30): 495–501. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0495. PMC 3442177. PMID 23008748.

- ^ Bowles DW, O'Bryant CL, Camidge DR, Jimeno A (July 2012). "The intersection between cannabis and cancer in the United States". Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. (Review). 83 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.09.008. PMID 22019199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jordan K, Sippel C, Schmoll HJ (September 2007). "Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations". Oncologist (Review). 12 (9): 1143–50. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1143. PMID 17914084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nicolson SE, Denysenko L, Mulcare JL; et al. (May–June 2012). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports". Psychosomatics (Review, case series). 53 (3): 212–9. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.01.003. PMID 22480624.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Phillips RS, Gopaul S, Gibson F; et al. (2010). "Antiemetic medication for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in childhood". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review) (9): CD007786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007786.pub2. PMID 20824866.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lutge EE, Gray A, Siegfried N (2013). "The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review). 4: CD005175. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005175.pub3. PMID 23633327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Martín-Sánchez E, Furukawa TA, Taylor J, Martin JL (November 2009). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of cannabis treatment for chronic pain". Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) (Review, meta-analysis). 10 (8): 1353–68. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00703.x. PMID 19732371.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lynch ME, Campbell F (November 2011). "Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials". British journal of clinical pharmacology (Review). 72 (5): 735–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x. PMC 3243008. PMID 21426373.

- ^ Carter GT, Flanagan AM, Earleywine M; et al. (August 2011). "Cannabis in palliative medicine: improving care and reducing opioid-related morbidity". The American journal of hospice & palliative care (Review). 28 (5): 297–303. doi:10.1177/1049909111402318. PMID 21444324.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lakhan SE, Rowland M (2009). "Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". BMC Neurology (Review). 9: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-9-59. PMC 2793241. PMID 19961570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b [conflicted source?] Clark PA, Capuzzi K, Fick C (2011). "Medical marijuana: Medical necessity versus political agenda". Medical Science Monitor (Review). 17 (12): RA249–61. doi:10.12659/MSM.882116. PMC 3628147. PMID 22129912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oreja-Guevara, C (2012). "Treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: New perspectives regarding the use of cannabinoids". Revista de neurologia (Review) (in Spanish). 55 (7): 421–30. PMID 23011861.

- ^ a b c Gordon AJ, Conley JW, Gordon JM (December 2013). "Medical consequences of marijuana use: a review of current literature". Curr Psychiatry Rep (Review). 15 (12): 419. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0419-7. PMID 24234874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Washington, Tabitha A.; Brown, Khalilah M.; Fanciullo, Gilbert J. (2012). "Chapter 31: Medical Cannabis". Pain. Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-19-994274-9.

Proponents of medical cannabis site its safety, but there are clear uncertainties regarding safety, composition and dosage.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G (2012). "Chapter 60: Marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) and synthetic cannabinoids". Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. pp. 886–931. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- ^ Downer EJ, Campbell VA (January 2010). "Phytocannabinoids, CNS cells and development: a dead issue?". Drug Alcohol Rev (Review). 29 (1): 91–8. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00102.x. PMID 20078688.

- ^ Burns TL, Ineck JR (2006). "Cannabinoid analgesia as a potential new therapeutic option in the treatment of chronic pain". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy (Review). 40 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1345/aph.1G217. PMID 16449552.

- ^ a b c d Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ, Mallya A, Lynn TA, Finney R, Svrakic NM (2012). "Legalization, decriminalization & medicinal use of cannabis: a scientific and public health perspective". Mo Med (Review). 109 (2): 90–8. PMID 22675784.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Curtis A, Clarke CE, Rickards HE (2009). "Cannabinoids for Tourette's Syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review) (4): CD006565. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006565.pub2. PMID 19821373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS (December 2012). "Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. (Review). 367 (1607): 3364–78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0389. PMC 3481531. PMID 23108553.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (August 2007). "Cannabidiol--recent advances". Chem. Biodivers. (Review). 4 (8): 1678–92. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sativex, FASS-Allmänhet (only in Swedish), Läkemedelsindustriföreningens Service AB

- ^ Abel, Ernest L. (1980). "Cannabis in the Ancient World". Marihuana: the first twelve thousand years. New York City: Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-40496-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)[page needed] - ^ Li, Hui-Lin (1974). "An Archaeological and Historical Account of Cannabis in China", Economic Botany 28.4:437–448, p. 444.

- ^ Bloomquist, Edward (1971). Marijuana: The Second Trip. California: Glencoe Press.

- ^ Wong, Ming (1976). La Médecine chinoise par les plantes. Paris: Tchou. OCLC 2646789.[page needed]

- ^ [unreliable source?] "The Ebers Papyrus The Oldest (confirmed) Written Prescriptions For Medical Marihuana era 1,550 BC". onlinepot.org. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ^ Pain, Stephanie (15 December 2007). "The Pharaoh's pharmacists". New Scientist. Reed Business Information Ltd.

- ^ Touw, Mia (1981). "The Religious and Medicinal Uses ofCannabisin China, India and Tibet". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 13 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.1981.10471447. PMID 7024492.

- ^ a b Butrica, James L. (2002). "The Medical Use of Cannabis Among the Greeks and Romans". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2 (2): 51. doi:10.1300/J175v02n02_04.

- ^ Lozano, Indalecio (2001). "The Therapeutic Use of Cannabis sativa (L.) in Arabic Medicine". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1: 63. doi:10.1300/J175v01n01_05.

- ^ Alison Mack; Janet Joy (7 December 2000). Marijuana As Medicine?: The Science Beyond the Controversy. National Academies Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-309-06531-3.

- ^ Dr Farid F. Youssef. "Cannibis Unmasked: What it is and why it does what it does". UWIToday: June 2010. http://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/archive/june_2010/article9.asp

- ^ [needs update] Baker D, Pryce G, Giovannoni G, Thompson AJ (May 2003). "The therapeutic potential of cannabis". Lancet Neurol. 2 (5): 291–8. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00381-8. PMID 12849183.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mack,Alison ; Joy, Janet (2001). Marijuana As Medicine. National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-06531-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ a b Reinarman C, Nunberg H, Lanthier F, Heddleston T (2011). "Who are medical marijuana patients? Population characteristics from nine California assessment clinics". J Psychoactive Drugs (Review). 43 (2): 128–35. doi:10.1080/02791072.2011.587700. PMID 21858958.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blackwell, Tom (16 October 2013). "The pot vending machine's first foreign market? Canada, of course, 'a seed for the rest of the world'". National Post. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b US patent 6630507, Aidan J. Hampson; Iulius Axelrod & Maurizio Grimaldi, "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants", issued 2003-10-07, assigned to The United States of America as represented by the Department of Health and Human Services

- ^ a b "Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 As amended by the 1972 Protocol" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. United Nations. 13 March 1961. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ AMA meeting: Delegates support review of cannabis's schedule I status; A change could make it easier for researchers to test potential medical uses and develop a drug delivery form safer than smoking. By Kevin B. O'Reilly, American Medical News. 30 November 2009

- ^ "AMA Urges Reclassifying Marijuana". Americans for Safe Access. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Use of Cannabis for Medicinal Purposes" (PDF). Report 3 of the Council on Science and Public Health (I-09). American Medical Assn. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Supporting Research into the Therapeutic Role of Marijuana" (PDF). The American College of Physicians. 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Medical Marijuana Endorsements and Statements of Support". Marijuana Policy Project. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- ^ "Marijuana: Policy & Advocacy". American Academy of Family Physicians. 2009. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ US patent 6630507, Hampson, Aidan J.; Axelrod, Julius; Grimaldi, Maurizio, "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants", issued 2003-10-07

- ^ Iuvone T, Esposito G, De Filippis D; et al. (2009). "Cannabidiol: A promising drug for neurodegenerative disorders?". CNS neuroscience & therapeutics (Review). 15 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00065.x. PMID 19228180.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [needs update] Carter GT, Rosen BS (2001). "Marijuana in the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The American journal of hospice & palliative care (Review). 18 (4): 264–70. doi:10.1177/104990910101800411. PMID 11467101.

- ^ [needs update] Ashton CH, Moore PB, Gallagher P, Young AH, (2005). "Cannabinoids in bipolar affective disorder: A review and discussion of their therapeutic potential". Journal of psychopharmacology (Review, meta-analysis). 19 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1177/0269881105051541. PMID 15888515.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ethan B Russo (5 September 2013). Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-136-61493-4.

- ^ [needs update] Di Carlo G, Izzo AA (2003). "Cannabinoids for gastrointestinal diseases: potential therapeutic applications". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs (Review). 12 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1517/13543784.12.1.39. PMID 12517253.

- ^ a b "Cannabis and Cannabinoids (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Bowles, DW (July 2012). "The intersection between cannabis and cancer in the United States". Critical reviews in oncology/hematology (Review). 83 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.09.008. PMID 22019199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids". Health Canada. February 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ "Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Human/Clinical Studies". National Cancer Institute. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ a b Arney, Kat (25 July 2012). "Cannabis, cannabinoids and cancer – the evidence so far". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Campbell VA, Gowran A (2007). "Alzheimer's disease; taking the edge off with cannabinoids?". British Journal of Pharmacology (Review). 152 (5): 655–62. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707446. PMC 2190031. PMID 17828287.

- ^ Bilkei-Gorzo A (2012). "The endocannabinoid system in normal and pathological brain ageing". Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences (Review). 367 (1607): 3326–41. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0388. PMC 3481530. PMID 23108550.

- ^ Krishnan S, Cairns R, Howard R (2009). "Cannabinoids for the treatment of dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review) (2): CD007204. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007204.pub2. PMID 19370677.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Di Marzo V, Piscitelli F, Mechoulam R (2011). "Cannabinoids and endocannabinoids in metabolic disorders with focus on diabetes". Handb Exp Pharmacol. (Review). Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 203 (75): 75–104. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-17214-4_4. ISBN 978-3-642-17213-7. PMID 21484568.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fisher M, White S, Varbiro G; et al. (2010). "The role of cannabis and cannabinoids in diabetes". The British Journal of Diabetes & Vascular Disease. 10 (6): 267. doi:10.1177/1474651410385860.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gloss D, Vickrey B (2012). "Cannabinoids for epilepsy". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review). 6: CD009270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub2. PMID 22696383.

- ^ Pertwee RG (2012). "Targeting the endocannabinoid system with cannabinoid receptor agonists: pharmacological strategies and therapeutic possibilities". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences (Review). 367 (1607): 3353–63. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0381. PMC 3481523. PMID 23108552.

- ^ Ward, Andrew (9 January 2014). "GW raises nearly $90m to develop childhood epilepsy treatment". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Jampel, Henry (10 August 2009). "Position statement on marijuana and the treatment of glaucoma". American Glaucoma Society. Retrieved November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Yazulla S (September 2008). "Endocannabinoids in the retina: from marijuana to neuroprotection". Progress in retinal and eye research (Review). 27 (5): 501–26. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.07.002. PMC 2584875. PMID 18725316.

- ^ [needs update] Kogan NM, Mechoulam R (2007). "Cannabinoids in health and disease". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 9 (4): 413–30. PMC 3202504. PMID 18286801.

- ^ [needs update] Singer HS (2005). "Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology". Lancet Neurol (Review). 4 (3): 149–59. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4. PMID 15721825.

- ^ [needs update] Robertson MM (2000). "Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment". Brain: a journal of neurology (Review). 123 (3): 425–62. doi:10.1093/brain/123.3.425. PMID 10686169.

Further reading

- Iversen, Leslie L. (2000). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513123-1.

- 2009 Conference on Cannabinoids in Medicine, International Association for Cannabis as Medicine

- "References on Multiple Sclerosis and Marijuana". Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Wujastyk, Dominik (12 September 2001). "Cannabis in Traditional Indian Herbal Medicine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2005. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

External links

- Medical cannabis at Curlie, links to websites about medical cannabis.

- Information on Cannabis and Cannabinoids from the U.S. National Cancer Institute

- Information on cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids from Health Canada

- The Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research of the University of California.