Somalia: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 371290747 by StoneProphet (talk)You have not obtained consensus for this & are on an editing probation. |

i dont need consensus for non controversial addings - stop deleting it. You have btw the same restriction. |

||

| Line 345: | Line 345: | ||

==Health== |

==Health== |

||

[[File:Edna-adan-maternity-hospital-hargeisa.jpg|thumb|[[Edna Adan Maternity Hospital]]]] |

[[File:Edna-adan-maternity-hospital-hargeisa.jpg|thumb|[[Edna Adan Maternity Hospital]]]] |

||

Somalia was one of only three countries in Africa to increase its [[life expectancy]] by five years.<ref>Somalia After State Collapse: Chaos or Improvement? By Benjamin Powell pg 16</ref> It also has one of the lowest [[HIV]] infection rates on the continent. This is attributed to the [[Muslim]] nature of Somali society and adherence of Somalis to Islamic morals.<ref name="RCTHIV">{{cite web|url=http://ams.ac.ir/aim/07104/0012.pdf |title=Religious and cultural traits in HIV/AIDS epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2010-06-27}}</ref> While the estimated HIV prevalence rate in Somalia in 1987 (the first case report year) was 1% of adults,<ref name="RCTHIV"/> a more recent estimate from 2007 now places it at only 0.5% of the nation's adult population despite the ongoing civil strife.<ref name=2009factbook>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/so.html|title=Somalia|accessdate=2009-05-31|date=2009-05-14|work=[[World Factbook]]|publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]]}}</ref> Some of the prominent [[healthcare]] facilities in the country are: |

Somalia was one of only three countries in Africa to increase its [[life expectancy]] by five years.<ref>Somalia After State Collapse: Chaos or Improvement? By Benjamin Powell pg 16</ref> The current life expectancy of a newborn Somali is at an average of 50 years. The population is generally very young, with the median age at 17.6 years. Somalia has a very high population growth combined with a high infant mortality rate of 107.42 deaths per 1,000 live births.<ref name=CIA Factbook 2009>https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/so.html#Econ</ref> It also has one of the lowest [[HIV]] infection rates on the continent. This is attributed to the [[Muslim]] nature of Somali society and adherence of Somalis to Islamic morals.<ref name="RCTHIV">{{cite web|url=http://ams.ac.ir/aim/07104/0012.pdf |title=Religious and cultural traits in HIV/AIDS epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2010-06-27}}</ref> While the estimated HIV prevalence rate in Somalia in 1987 (the first case report year) was 1% of adults,<ref name="RCTHIV"/> a more recent estimate from 2007 now places it at only 0.5% of the nation's adult population despite the ongoing civil strife.<ref name=2009factbook>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/so.html|title=Somalia|accessdate=2009-05-31|date=2009-05-14|work=[[World Factbook]]|publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]]}}</ref> Some of the prominent [[healthcare]] facilities in the country are: |

||

*[[East Bardera Mothers and Children's Hospital]] |

*[[East Bardera Mothers and Children's Hospital]] |

||

*[[Abudwak Maternity and Children's Hospital]] |

*[[Abudwak Maternity and Children's Hospital]] |

||

Revision as of 00:21, 2 July 2010

Republic of Somalia [Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Rtl-lang Template:Rtl-lang | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: [Soomaaliyeey Toosoow] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Somalia, Wake Up | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Mogadishu |

| Official languages | Somali |

| Recognised regional languages | Arabic[1][2] |

| Ethnic groups | Somalis (85%), Benadiri, Bantus and other non-Somalis (15%)[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Somali |

| Government | Coalition government |

| Sharif Ahmed | |

| Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke | |

| Sharif Hassan Sheikh Aden | |

| Formation | |

| 14th century | |

| 15th century | |

| 18th century | |

| 20th century | |

• Union of protectorate and trust territory | 1 July 1960 |

| Area | |

• Total | 637,661 km2 (246,202 sq mi) (41st) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 9,133,000[3] (85th) |

• Density | 14.3/km2 (37.0/sq mi) (198th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate |

• Total | $7.599 billion (153rd) |

• Per capita | $795[4] (222nd) |

| HDI (2009) | N/A Error: Invalid HDI value (Not Ranked) |

| Currency | Somali shilling (SOS) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (not observed) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 252 |

| ISO 3166 code | SO |

| Internet TLD | .so (currently not operating) |

Somalia (Template:Pron-en soh-MAH-lee-ə; Template:Lang-so; Template:Lang-ar aṣ-Ṣūmāl), officially the Republic of Somalia (Template:Lang-so, Template:Lang-ar Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmāl) and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic under communist rule, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, the Gulf of Aden with Yemen to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, and Ethiopia to the west.

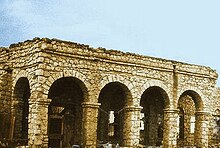

In antiquity, Somalia was an important center for commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Its sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh and spices, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans and Babylonians with whom the Somali people traded.[6][7] According to most scholars, Somalia is also where the ancient Kingdom of Punt was situated.[8][9][10][11] The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Pharaonic Egypt during the times of Pharaoh Sahure and Queen Hatshepsut. The pyramidal structures, temples and ancient houses of dressed stone littered around Somalia are said to date from this period.[12] In the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuuraan State, which excelled in hydraulic engineering and fortress building,[13] the Sultanate of Adal, whose general Ahmed Gurey was the first commander in history to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire,[14] and the Gobroon Dynasty, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf.[15]

Somalia was never formally colonized.[16][17][18] Muhammad Abdullah Hassan's Dervish State successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[19] As a result of its fame in the Middle East and Europe, the Dervish State was recognized as an ally by the Ottoman Empire and the German Empire,[20][21] and remained throughout World War I the only independent Muslim power on the continent. After a quarter of a century holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 when Britain for the first time in Africa used aeroplanes when it bombed the Dervish capital of Taleex. As a result of this bombardment, former Dervish territories were turned into a protectorate of Britain. Italy similarly faced the same opposition from Somali Sultans and armies and did not acquire full control of parts of modern Somalia until the Fascist era in late 1927. This occupation lasted till 1941 and was replaced by a British military administration. Northern Somalia would remain a protectorate while southern Somalia became a trusteeship. The Union of the two regions in 1960 formed the Somali Republic.

Due to its longstanding ties with the Arab world, Somalia was accepted in 1974 as a member of the Arab League. To strengthen its relationship with the rest of the African continent, Somalia joined other African nations when it founded the African Union, and began to support the ANC in South Africa against the apartheid regime[22] and the Eritrean secessionists in Ethiopia during the Eritrean War of Independence.[23] A Muslim country, Somalia is one of the founding members of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference and is also a member of the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. Despite suffering from civil strife and instability, Somalia has also managed to sustain a free market economy which, according to the World Bank, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, the Independent Institute and the Foundation for Economic Education, outperforms those of many other countries in Africa.[24][25][26][27]

History

| History of Somalia |

|---|

|

|

|

Prehistory

Somalia has been inhabited by man since the Paleolithic period. Cave paintings dating back as far as 9000 BC have been found in northern Somalia. The most famous of these is the Laas Geel complex, which contains some of the earliest known rock art on the African continent. Inscriptions have been found beneath each of the rock paintings, but archaeologists have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing.[28] During the Stone age, the Doian culture and the Hargeisan culture flourished here with their respective industries and factories.

The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BC. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in northern Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in Paleolithic times between the East and the West.[29]

Antiquity and classical era

Ancient pyramidal structures, tombs, ruined cities and stone walls such as the Wargaade Wall littered in Somalia are evidence of an ancient sophisticated civilization that once thrived in the Somali peninsula.[30] The findings of archaeological excavations and research in Somalia show that this civilization had an ancient writing system that remains undeciphered,[31] and enjoyed a lucrative trading relationship with Ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece since at least the second millennium BC, which supports the view of Somalia being the ancient Kingdom of Punt.[32]

The Puntites "traded not only in their own produce of incense, ebony and short-horned cattle, but also in goods from other neighbouring regions, including gold, ivory and animal skins."[33] According to the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahri, the Land of Punt was ruled at that time by King Parahu and Queen Ati.[34]

Ancient Somalis domesticated the camel somewhere between the third millennium and second millennium BC from where it spread to Ancient Egypt and North Africa.[35] In the classical period, the city states of Mossylon, Opone, Malao, Mundus and Tabae in Somalia developed a lucrative trade network connecting with merchants from Phoenicia, Ptolemaic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea and the Roman Empire. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, a mutual agreement by Arab and Somali merchants barred Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula because of the nearby Romans.[36] However, they continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from any Roman threat or spies.[37] The reason for barring Indian ships from entering the wealthy Arabian port cities was to protect and hide the exploitative trade practices of the Somali and Arab merchants in the extremely lucrative ancient Red Sea– Mediterranean Sea commerce.[38]

The Indian merchants for centuries brought large quantities of cinnamon from Ceylon and the Far East to Somalia and Arabia. This is said to have been the best kept secret of the Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world. The Romans and Greeks believed the source of cinnamon to have been the Somali peninsula but in reality, the highly valued product was brought to Somalia by way of Indian ships.[39] Through Somali and Arab traders, Indian/Chinese cinnamon was also exported for far higher prices to North Africa, the Near East and Europe, which made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue generator, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across ancient sea and land routes.

Birth of Islam & the Middle Ages

The history of Islam in the Horn of Africa is as old as the religion itself. The early persecuted Muslims fled to the Axumite port city of Zeila in modern day Somalia to seek protection from the Quraysh at the court of the Axumite Emperor in present day Ethiopia. Some of the Muslims that were granted protection are said to have settled in several parts of the Horn of Africa to promote the religion.

The victory of the Muslims over the Quraysh in the 7th century had a significant impact on Somalia's merchants and sailors, as their Arab trading partners had then all adopted Islam, and the major trading routes in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea came under the sway of the Muslim Caliphs. Through commerce, Islam spread amongst the Somali population in the coastal cities of Somalia. Instability in the Arabian peninsula saw several migrations of Arab families to Somalia's coastal cities, who then contributed another significant element to the growing popularity of Islam in the Somali peninsula.

Mogadishu became the center of Islam on the East African coast, and Somali merchants established a colony in Mozambique to extract gold from the Monomopatan mines in Sofala. In northern Somalia, Adal was in its early stages a small trading community established by the newly converted Horn African Muslim merchants, who were predominantly Somali according to Arab and Somali chronicles.

The century between 1150 and 1250 marked a decisive turn in the role of Islam in Somali history. Yaqut Al-Hamawi and later ibn Said noted that the Berbers (Somalis) were a prosperous Muslim nation during that period. The Adal Sultanate was now the center of a commercial empire stretching from Cape Guardafui to Hadiya. The Adalites then came under the influence of the expanding Horn African Kingdom of Ifat, and prospered under its patronage.

The capital of the Ifat was Zeila, situated in northern present-day Somalia, from where the Ifat army marched to conquer the ancient Kingdom of Shoa in 1270. This conquest ignited a rivalry for supremacy between the Christian Solomonids and the Muslim Ifatites that resulted in several devastating wars, and ultimately ended in a Solomonic victory over the Kingdom of Ifat after the death of the popular Sultan Sa'ad ad-Din II in Zeila by Dawit II. Sa'ad ad-Din II's family was subsequently given safe haven at the court of the King of Yemen, where his sons regrouped and planned their revenge on the Solomonids.

During the Age of the Ajuuraans, the sultanates and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venetia,[40] Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[41]

In the 1500s, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[42] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria[43]), together with Merca and Barawa, also served as a transit stop for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[44] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[45]

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century[46] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[47] Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between the Asia and Africa[48] and influenced the Chinese language with the Somali language in the process. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani meddling, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[49]

Early modern era & the Scramble for Africa

In the early modern period, successor states of the Adal and Ajuuraan empires began to flourish in Somalia. These were the Gerad Dynasty, the Bari Dynasties and the Gobroon Dynasty. They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started the golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army came out victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade. He also received presents from and had cordial relations with the rulers of neighbouring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu and Yemeni Sultans.

Sultan Ibrahim's son Ahmed Yusuf succeeded him and was one of the most important figures in 19th century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast. In northern Somalia, the Gerad Dynasty conducted trade with Yemen and Persia and competed with the merchants of the Bari Dynasty. The Gerads and the Bari Sultans built impressive palaces, castles and fortresses and had close relations with many different empires in the Near East.

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin conference, European powers began the Scramble for Africa, which inspired the Dervish leader Muhammad Abdullah Hassan to rally support from across the Horn of Africa and begin one of the longest colonial resistance wars ever. In several of his poems and speeches, Hassan emphasized that the British infidels "have destroyed our religion and made our children their children" and that the Christian Ethiopians in league with the British were bent upon plundering the political and religious freedom of the Somali nation. He soon emerged as "a champion of his country's political and religious freedom, defending it against all Christian invaders."

Hassan issued a religious ordinance stipulating that any Somali national who did not accept the goal of unity of Somalia and would not fight under his leadership would be considered as kafir or gaal. He soon acquired weapons from Turkey, Sudan, and other Islamic and/or Arabian countries, and appointed ministers and advisers to administer different areas or sectors of Somalia. In addition, he gave a clarion call for Somali unity and independence, in the process organizing his forces.

Hassan's Dervish movement had an essentially military character, and the Dervish state was fashioned on the model of a Salihiya brotherhood. It was characterized by a rigid hierarchy and centralization. Though Hassan threatened to drive the Christians into the sea, he executed the first attack by launching his first major military offensive with his 1500 Dervish equipped with 20 modem rifles on the British soldiers stationed in the region.

He repulsed the British in four expeditions and had relations with the central powers of the Ottomans and the Germans. In 1920, the Dervish state collapsed after intensive aerial bombardments by Britain, and Dervish territories were subsequently turned into a protectorate.

The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia according to the plan of Fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of Somaliland known as Italian Somaliland. Italy had access to these areas under the successive protection treaties, but not direct rule.

The Fascist government had direct rule only over the Benadir territory. Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, with an aim to colonize it. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, but little was done to stop it or to liberate occupied Ethiopia. On August 3, 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, crossed from Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland, and by August 14, succeeded in taking Berbera from the British.

A British force, including troops from several African countries, launched the campaign in January 1941 from Kenya to liberate British Somaliland and Italian-occupied Ethiopia and conquer Italian Somaliland. By February, most of Italian Somaliland was captured and in March, British Somaliland was retaken from the sea. The British Empire forces operating in Somaliland comprised three divisions of South African, West and East African troops. They were assisted by Somali forces led by Abdulahi Hassan with Somalis of the Isaaq, Dhulbahante, and Warsangali clans prominently participating. After World War II, the number of the Italian colonists started to decrease; their numbers had dwindled to less than 10,000 in 1960.[50]

The State of Somalia

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In November 1949, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) (which later became Hizbia Dastur Mustaqbal Somali) and the Somali National League (SNL), that were then agitating for independence — that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[51][52] British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.[53]

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would cause serious difficulties when it came time to integrate the two parts.[54]

Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[55] the British "returned" the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was presumably 'protected' by British treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against plundering by Somali clans.[56]

Britain included the proviso that the Somali nomads would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over them.[51] This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had turned over.[51] Britain also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited[57] Northern Frontier District (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists despite an informal plebiscite demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.[58]

A referendum was held in neighbouring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans. However, the majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later. Djibouti finally gained its independence from France in 1977 and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a French-groomed Somali who campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).[59]

British Somaliland became independent on June 26, 1960, and the former Italian Somaliland followed suit five days later.[60] On July 1, 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic, albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain.[61][62][63] A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa with Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President,[64][65][66] and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister, later to become President (from 1967–1969). On July 20, 1961 and through a popular referendum, the Somali people ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960.[67]

However, inter-clan rivalry persisted.[62][68][69][70] In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke. Egal would later become the President of the autonomous Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.

In late 1969, following the assassination of President Shermarke, a military government assumed power in a coup d'état led by Major General Salaad Gabeyre Kediye, General Siad Barre and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Barre became President and Korshel vice-president. The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programmes and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate from 5% to 55% by the mid-1980s. However, struggles continued during Barre's rule. At one point he assassinated a major figure in his cabinet, Major General Gabeyre, and two other officials.

It was in July 1976 when the real dictatorship of the Somali military commenced with the founding of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (Xisbiga Hantiwadaagga Kacaanka Soomaaliyeed, XHKS). This party ruled Somalia until the fall of the military government in December 1990–January 1991. It was violently overthrown by the combined armed revolt of the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (Jabhadda Diimuqraadiga Badbaadinta Soomaaliyeed, SSDF), United Somali Congress (USC), Somali National Movement (SNM), and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM) together with the non-violent political oppositions of the Somali Democratic Movement (SDM), the Somali Democratic Alliance (SDA) and the Somali Manifesto Group (SMG). The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic.

In 1977 and 1978, Somalia invaded its neighbour Ethiopia in the Ogaden War, in which Somalia aimed to unite the Somali lands that had been partitioned by the former colonial powers, and to win the right of self-determination for ethnic Somalis in those territories. Somalia first engaged Kenya and Ethiopia diplomatically, but this failed. Somalia, already preparing for war, created the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF, then called the Western Somali Liberation Front, WSLF) and eventually sought to capture Ogaden. Somalia acted unilaterally without consulting the international community, which was generally opposed to redrawing colonial boundaries, while the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries refused to help Somalia, and instead, backed Communist Ethiopia. Still the USSR, finding itself supplying both sides of a war, attempted to mediate a ceasefire.

In the first week of the conflict Somali armed forces took southern and central Ogaden and for most of the war, the Somali army scored continuous victories on the Ethiopian army and followed them as far as Sidamo. By September 1977, Somalia controlled 90% of the Ogaden and captured strategic cities such as Jijiga and put heavy pressure on Dire Dawa, threatening the train route from the latter city to Djibouti. After the siege of Harar, a massive unprecedented Soviet intervention consisting of 20 thousand Cuban forces and several thousands Soviet experts came to the aid of Ethiopia. The Somali Army was forced to withdraw and consequently Somalia sought the help of the United States. Although the Carter Administration had expressed interest in helping Somalia, it later declined, as did American allies in the Middle East and Asia.

By 1978, the moral authority of the Somali government had collapsed. Many Somalis had become disillusioned with life under military dictatorship and the regime was weakened further in the 1980s as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance was diminished. The government became increasingly totalitarian, and resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia, sprang up across the country, eventually leading to the Somali Civil War.

During 1990, in the capital city of Mogadishu, the residents were prohibited from gathering publicly in groups greater than three or four. Fuel shortages caused long lines of cars at petrol stations. Inflation had driven the price of pasta, (ordinary dry Italian noodles, a staple at that time), to five U.S. dollars per kilogram. The price of khat, imported daily from Kenya, was also five U.S. dollars per standard bunch. Paper currency notes were of such low value that several bundles were needed to pay for simple restaurant meals. Coins were scattered on the ground throughout the city being too low in value to be used.

A thriving black market existed in the centre of the city as banks experienced shortages of local currency for exchange. At night, the city of Mogadishu lay in darkness. The generators used to provide electricity to the city had been sold off by the government. Close monitoring of all visiting foreigners was in effect. Harsh exchange control regulations were introduced to prevent export of foreign currency and access to it was restricted to official banks, or one of three government-operated hotels.

Although no travel restrictions were placed on foreigners, photographing many locations was banned. During the day in Mogadishu, the appearance of any government military force was extremely rare. Alleged late-night operations by government authorities, however, included "disappearances" of individuals from their homes.

The Somali Civil War

1991 was a time of great change for Somalia. President Barre was ousted by combined northern and southern clan-based forces, all of whom were backed and armed by Ethiopia. And following a meeting of the Somali National Movement and northern clans' elders, the northern former British portion of the country declared its independence as Somaliland in May 1991; although de facto independent and relatively stable compared to the tumultuous south, it has not been recognised by any foreign government.[72][73]

In January 1991, President Ali Mahdi Muhammad was selected by the manifesto group as an interim state president until a conference between all stakeholders to be held in Djibouti the following month to select a national leader. However, United Somali Congress military leader General Mohamed Farrah Aidid, the Somali National Movement leader Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur and the Somali Patriotic Movement leader Col Jess refused to recognize Mahdi as president.

This caused a split between the SNM, USC and SPM and the armed groups Manifesto, Somali Democratic Movement (SDM) and Somali National Alliance (SNA) on the one hand and within the USC forces. This led efforts to remove Barre who still claimed to be the legitimate president of Somalia. He and his armed supporters remained in the south of the country until mid 1992, causing further escalation in violence, especially in the Gedo, Bay, Bakool, Lower Shabelle, Lower Juba, and Middle Juba regions. The armed conflict within the USC devastated the Mogadishu area.

The civil war disrupted agriculture and food distribution in southern Somalia. The basis of most of the conflicts was clan allegiances and competition for resources between the warring clans. James Bishop, the United States last ambassador to Somalia, explained that there is "competition for water, pasturage, and... cattle. It is a competition that used to be fought out with arrows and sabers... Now it is fought out with AK-47s."[75] The resulting famine (about 300,000 dead) caused the United Nations Security Council in 1992 to authorise the limited peacekeeping operation United Nations Operation in Somalia I (UNOSOM I).[76] UNOSOM's use of force was limited to self-defence and it was soon disregarded by the warring factions.

In reaction to the continued violence and the humanitarian disaster, the United States organised a military coalition with the purpose of creating a secure environment in southern Somalia for the conduct of humanitarian operations. This coalition, (Unified Task Force or UNITAF) entered Somalia in December 1992 on Operation Restore Hope and was successful in restoring order and alleviating the famine. In May 1993, most of the United States troops withdrew and UNITAF was replaced by the United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II).

However, Mohamed Farrah Aidid saw UNOSOM II as a threat to his power and in June 1993 his militia attacked Pakistan Army troops, attached to UNOSOM II, (see Somalia (March 1992 to February 1996)) in Mogadishu inflicting over 80 casualties. Fighting escalated until 19 American troops and more than 1,000 civilians and militia were killed in a raid in Mogadishu during October 1993.[77][78] The UN withdrew Operation United Shield in 3 March 1995, having suffered significant casualties, and with the rule of government still not restored. In August 1996, Aidid was killed in Mogadishu.

A consequence of the collapse of governmental authority that accompanied the civil war has been the creation of a significant problem with piracy[79] off the coast of Somalia originating in coastal ports.[80] Piracy arose as a response by local Somali fishermen from coastal towns such as Eyl, Kismayo and Harardhere to predatory fishing by foreign fishing trawlers that followed the collapse of Somali governmental authority.[81][82] An upsurge in piracy off the coast has also been attributed to the effects of the December 26, 2004 tsunami that devastated coastal villages fishing fleets.[83] Piracy has been described as Somalia's "only booming economy" and as a "mainstay" of the Puntland economy.[84][85][86]

From 1800 to 1890, between 25,000–50,000 Bantu slaves from Mozambique and Tanzania are thought to have been sold from the slave market of Zanzibar to the Somali coast.[87] Bantus are ethnically, physically, and culturally distinct from Somalis, and have remained marginalized ever since their arrival in Somalia.[88] The number of Bantu in Somalia before the civil war is thought to be about 900,000.[89] Since 2003, more than 12,000 Bantu refugees have settled in the United States.[90] The Tanzanian government has also begun granting Bantus citizenship and land in areas of Tanzania where their ancestors are known to have been removed from.[91]

Politics

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG) is the current internationally recognized federal government of Somalia. It was established as one of the Transitional Federal Institutions (TFIs) of government as defined in the Transitional Federal Charter (TFC) adopted in November 2004 by the Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP). It is the most recent attempt to restore national institutions to Somalia after the 1991 collapse of the Siad Barre regime and the ensuing Somali Civil War.

In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an Islamist organization, assumed control of much of the southern part of the country and promptly imposed Shari'a law. The Transitional Federal Government sought to reestablish its authority, and, with the assistance of Ethiopian troops, African Union peacekeepers and air support by the United States, managed to drive out the rival ICU and solidify its rule.[92]

Following this defeat, the Islamic Courts Union splintered into several different factions. Some of the more radical elements, including Al-Shabaab, regrouped to continue their insurgency against the TFG and oppose the Ethiopian military's presence in Somalia. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in both central and southern Somalia. At the end of 2008, the group had captured Baidoa but not Mogadishu. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other militias had managed to force the Ethiopian troops to withdraw from the country, leaving behind an under-equipped African Union peacekeeping force to assist the Transitional Federal Government's troops.[93]

On December 29, 2008, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed announced before a united parliament in Baidoa his resignation as President of Somalia. In his speech, which was broadcast on national radio, Yusuf expressed regret at failing to end the country's seventeen year conflict as his government had mandated to do.[94] He also blamed the international community for its failure to support the government, and said that the speaker of parliament would succeed him in office per the charter of the Transitional Federal Government.[95]

Over the next few months, a new President was elected from amongst the more moderate Islamists,[96] and Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, the son of slain former President Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, was selected as the nation's new Prime Minister. The Transitional Federal Government, with the help of a small team of African Union troops, also began a counteroffensive in February 2009 to retake control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its control of southern Somalia, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi militia.[97] Furthermore, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main Islamist groups in opposition, began to fight amongst themselves in mid-2009.[98]

As a truce, in March 2009, Somalia's newly established coalition government announced that it would re-implement Shari'a as the nation's official judicial system.[99] However, conflict continues in the southern and central parts of the country between government troops and extremist Islamist militants with links to al-Qaeda.[100]

Law

The legal structure in Somalia is divided along three lines: civil law, religious law, and traditional clan law.

Civil law

While Somalia's formal judicial system was largely destroyed after the fall of the Siad Barre regime, it has been rebuilt and is now administered under different regional governments such as the autonomous Puntland and Somaliland macro-regions. In the case of the Transitional Federal Government, a new judicial structure was formed through various international conferences.

Despite some significant political differences between them, all of these administrations share similar legal structures, much of which are predicated on the judicial systems of previous Somali administrations. These similarities in civil law include:[101]

- A charter which affirms the primacy of Muslim shari'a or religious law, although in practice shari'a is applied mainly to matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and civil issues.

- The charter guarantees respect for universal standards of human rights to all subjects of the law. It also assures the independence of the judiciary, which in turn is protected by a judicial committee.

- A three-tier judicial system including a supreme court, a court of appeals, and courts of first instance (either divided between district and regional courts, or a single court per region).

- The laws of the civilian government which were in effect prior to the military coup d'état that saw the Barre regime into power remain in force until the laws are amended.

Shari'a

Islamic shari'a has traditionally played a significant part in Somali society. In theory, it has served as the basis for all national legislation in every Somali constitution. In practice, however, it only applied to common civil cases such as marriage, divorce, inheritance and family matters. This changed after the start of the civil war when a number of new shari'a courts began to spring up in many different cities and towns across the country.[101]

These new shari'a courts serve three functions:

- To pass rulings in both criminal and civil cases.

- To organize a militia capable of arresting criminals.

- To keep convicted prisoners incarcerated.

The shari'a courts, though structured along simple lines, feature a conventional hierarchy of a chairman, vice-chairman and four judges. A police force that reports to the court enforces the judges' rulings, but also helps settle community disputes and apprehend suspected criminals. In addition, the courts manage detention centers where criminals are kept. An independent finance committee is also assigned the task of collecting and managing tax revenue levied on regional merchants by the local authorities.[101]

In March 2009, Somalia's newly established coalition government announced that it would implement shari'a as the nation's official judicial system.[99]

Xeer

Somalis for centuries have practiced a form of customary law which they call Xeer. Xeer is a polycentric legal system where there is no monopolistic institution or agent that determines what the law should be or how it should be interpreted.

The Xeer legal system is assumed to have developed exclusively in the Horn of Africa since approximately the 7th century. There is no evidence that it developed elsewhere or was greatly influenced by any foreign legal system. The fact that Somali legal terminology is practically devoid of loan words from foreign languages suggests that Xeer is truly indigenous.[102]

The Xeer legal system also requires a certain amount of specialization of different functions within the legal framework. Thus, one can find odayal (judges), xeer boggeyaal (jurists), guurtiyaal (detectives), garxajiyaal (attorneys), murkhaatiyal (witnesses) and waranle (police officers) to enforce the law.[103]

Xeer is defined by a few fundamental tenets that are immutable and which closely approximate the principle of jus cogens in international law:[101]

- Payment of blood money (locally referred to as diya) for libel, theft, physical harm, rape and death, as well as supplying assistance to relatives.

- Assuring good inter-clan relations by treating women justly, negotiating with "peace emissaries" in good faith, and sparing the lives of socially protected groups (e.g. children, women, the pious, poets and guests).

- Family obligations such as the payment of dowry, and sanctions for eloping.

- Rules pertaining to the management of resources such as the use of pasture land, water, and other natural resources.

- Providing financial support to married female relatives and newlyweds.

- Donating livestock and other assets to the poor.

Cities

Largest cities or towns in Somalia

. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Mogadishu Hargeisa |

1 | Mogadishu | Banaadir | 2,330,708[104][105] | 11 | Belad Weyne | Hiraan | 278,118 [104] |  Bossaso |

| 2 | Hargeisa | Woqooyi Galbeed | 1,346,651[104] | 12 | Hudun | Sool | 271,199[104] | ||

| 3 | Bossaso | Bari | 615,067[104] | 13 | Afgooye | Lower Shabelle | 265,684[104] | ||

| 4 | Borama | Awdal | 597,842[104] | 14 | Balcad | Middle Shabelle | 255,291[104] | ||

| 5 | Burco | Togdheer | 589,975[104] | 15 | Berbera | Woqooyi Galbeed | 251,189[104] | ||

| 6 | Baidoa | Bay | 546,957[104] | 16 | Laas Caanood | Sool | 246,020[104] | ||

| 7 | Gaalkacyo | Mudug | 501,542[104] | 17 | Kismayo | Lower Juba | 243,043[104] | ||

| 8 | Laasqoray | Sanaag | 343,101 [104] | 18 | Afmadow | Lower Juba | 231,017[104] | ||

| 9 | Garowe | Nugaal | 289,103[104] | 19 | Jowhar | Middle Shabelle | 221,044[104] | ||

| 10 | Qoriyoley | Lower Shabelle | 286,402[104] | 20 | Saacow | Middle Juba | 211,369[104] | ||

Regions and districts

Prior to the civil war, Somalia was divided into eighteen regions (gobollada, singular gobol), which were in turn subdivided into districts. The regions are:

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

On a de facto basis, northern Somalia is now divided up among the quasi-independent states of Puntland, Somaliland, and Galmudug. The south is at least nominally controlled by the Transitional Federal Government, although it is in fact controlled by Islamist groups outside Mogadishu. Under the de facto arrangements there are now 27 regions.

Geography and climate

Africa's easternmost country, Somalia has a land area of 637,540 square kilometers. It occupies the tip of a region that, due to its resemblance on the map to a rhinoceros' horn, is commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa. Somalia has the longest coastline on the continent. Its terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains, and highlands.

Cal Madow is a mountain range in the northeastern part of the country. Extending from several kilometers west of the city of Bosaso to the northwest of Erigavo, it features Somalia's highest peak, Shimbiris (2,410 m - 7,906 ft). The rugged east-west ranges of the Karkaar Mountains also lie at varying distances from the Gulf of Aden coast.

Major climatic factors are a year-round hot climate, seasonal monsoon winds, and irregular rainfall. Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 30 to 40 °C (86 to 104 °F), except at higher elevations and along the east coast. Mean daily minimums usually vary from about 15 to 30 °C (59 to 86 °F). The greatest range in climate occurs in the mountainous areas of northern Somalia, where temperatures sometimes surpass 45 °C (113 °F) in July and drop below the freezing point during December.[106]

The southwest monsoon, a sea breeze, makes the period from about May to October the mildest season in Mogadishu. The December to February period of the northeast monsoon is also relatively mild, although prevailing climatic conditions in Mogadishu are rarely pleasant. The tangambili periods that intervene between the two monsoons (October–November and March–May) are hot and humid.

| Climate data for Somalia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: Country Studies - Somalia[106] | |||||||||||||

Health

Somalia was one of only three countries in Africa to increase its life expectancy by five years.[107] The current life expectancy of a newborn Somali is at an average of 50 years. The population is generally very young, with the median age at 17.6 years. Somalia has a very high population growth combined with a high infant mortality rate of 107.42 deaths per 1,000 live births.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). It also has one of the lowest HIV infection rates on the continent. This is attributed to the Muslim nature of Somali society and adherence of Somalis to Islamic morals.[108] While the estimated HIV prevalence rate in Somalia in 1987 (the first case report year) was 1% of adults,[108] a more recent estimate from 2007 now places it at only 0.5% of the nation's adult population despite the ongoing civil strife.[2] Some of the prominent healthcare facilities in the country are:

- East Bardera Mothers and Children's Hospital

- Abudwak Maternity and Children's Hospital

- Edna Adan Maternity Hospital

- West Bardera Maternity Unit

Education

The Ministry of Education is officially responsible for education in Somalia, with about 15% of the government's budget being spent on academic instruction. In 2006, the autonomous Puntland region in the northeast was the second territory in Somalia after the Somaliland region to introduce free primary schools, with teachers now receiving their salaries from the Puntland administration.[109]

From 2005/2006 to 2006/2007, there was a significant increase in the number of schools in Puntland, up 137 institutions from just one year prior. During the same period, the number of classes in the region increased by 504, with 762 more teachers also offering their services.[110] Total student enrollment increased by 27% over the previous year, with girls lagging only slightly behind boys in attendance in most regions. The highest class enrollment was observed in the northernmost Bari region, and the lowest was observed in the under-populated Ayn region. The distribution of classrooms was almost evenly split between urban and rural areas, with marginally more pupils attending and instructors teaching classes in urban areas.[110]

Higher education in Somalia is now largely private. Several universities in the country, including Mogadishu University, have been scored among the 100 best universities in Africa in spite of the harsh environment, which has been hailed as a triumph for grass-roots initiatives.[111] Other universities also offering higher education in the south include Benadir University, the Somalia National University, Kismayo University and the University of Gedo. In Puntland, higher education is provided by the Puntland State University and East Africa University. In Somaliland, it is provided by Amoud University, the University of Hargeisa, Somaliland University of Technology and Burao University.

Qu'ranic schools (also known as duqsi) remain the basic system of traditional religious instruction in Somalia. They provide Islamic education for children, thereby filling a clear religious and social role in the country. Known as the most stable local, non-formal system of education providing basic religious and moral instruction, their strength rests on community support and their use of locally made and widely available teaching materials. The Qu'ranic system, which teaches the greatest number of students relative to other educational sub-sectors, is often the only system accessible to Somalis in nomadic as compared to urban areas. A study from 1993 found, among other things, that about 40% of pupils in Qur'anic schools were girls. To address shortcomings in religious instruction, the Somali government on its own part also subsequently established the Ministry of Endowment and Islamic Affairs, under which Qur'anic education is now regulated.[112]

Economy

According to the CIA, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, the Independent Institute and the Foundation for Economic Education, despite experiencing civil unrest, Somalia has maintained a healthy informal economy, based mainly on livestock, remittance/money transfer companies, and telecommunications.[2][113][24][26][27] Due to a dearth of formal government statistics and the recent civil war, it is difficult to gauge the size or growth of the economy. For 1994, the CIA estimated the GDP at $3.3 billion.[114] In 2001, it was estimated to be $4.1 billion.[115] By 2009, the CIA estimated that the GDP had grown to $5.731 billion, with a projected real growth rate of 2.6%.[2] According to a 2003 World Bank study, the private sector grew impressively, particularly in the areas of trade, commerce, transport, remittance and infrastructure services, in addition to the primary sectors, notably livestock, agriculture and fisheries.[116] In 2007, the United Nations reported that the country's service industry is also thriving.[117] Anthropologist Spencer Heath MacCallum attributes this increased economic activity to the Somali customary law (referred to as Xeer), which provides a stable environment to conduct business in.[24]

Agriculture is the most important sector, with livestock accounting for about 40% of GDP and more than 50% of export earnings.[2] Other principal exports include fish, charcoal and bananas; sugar, sorghum and corn are products for the domestic market.[118] At nearly 3 million heads of goat and sheep in 1999, the northern ports of Bosaso and Berbera accounted for 95% of all goat and 52% of all sheep exports of East Africa. The Somaliland region alone exported more than 180 million metric tons of livestock and more than 480 million metric tons of agricultural products.[26] Somalia is also a major world supplier of frankincense and myrrh.

The modest industrial sector, based on the processing of agricultural products, accounts for 10% of Somalia's GDP.[2] Up to 14 private airline firms operating 62 aircrafts now also offer commercial flights to international locations.[119][120] With competitively priced flight tickets, these companies have helped buttress Somalia's bustling trade networks.[119]

With the help of the Somali diaspora, mobile phone companies, internet cafés and radio stations have been established. According to the UNDP, investments in light manufacturing have expanded in Bosaso, Hargeisa and Mogadishu, in particular, indicating growing business confidence in the economy.[120] To this end, in 2004, an $8.3 million Coca-Cola bottling plant opened in Mogadishu, with investors hailing from various constituencies in Somalia.[121] The robust private sector has also attracted foreign investment from the likes of General Motors and Dole Fruit.[120]

In addition, funds transfer services have become a major industry in the country, with an estimated $1.6 billion USD annually remitted to Somalia by Somalis in the diaspora via money transfer companies.[2] The largest of these informal value transfer system or hawala dealers is Dahabshiil, a Somali-owned firm employing more than 2000 people across 144 countries with branches in London and Dubai.[122][123]

Energy

Due to its proximity to the oil-rich Gulf Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Somalia is believed to contain substantial unexploited reserves of oil. A survey of Northeast Africa by the World Bank and U.N. ranked it second only to Sudan as the top prospective producer.[124] American, Australian and Chinese oil companies, in particular, are excited about the prospect of finding petroleum and other natural resources in the country. An oil group listed in Sydney, Range Resources, anticipates that the Puntland province in the north has the potential to produce 5 billion to 10 billion barrels of oil.[125] As a result of these developments, the Somali Petroleum Company was created by the federal government.

According to surveys, uranium is also found in large quantities in the Buurhakaba region. A Brazilian company in the 1980s had invested $300 million for a uranium mine in central Somalia, but no long-term mining took place.[126] More recently, a joint Somali-Russian venture was proposed to export uranium from the country.

Additionally, the Puntland region under the Farole administration has since sought to refine the province's existing oil deal with Range Resources. The Australian oil firm, for its part, indicated that it looked forward to establishing a mutually beneficial and profitable working relationship with the region's new government.[127][128]

In mid-2010, Somalia's business community also pledged to invest $1 billion in the national gas and electricity industries over the following five years. Abdullahi Hussein, the director of the just-formed Trans-National Industrial Electricity and Gas Company, predicted that the investment strategy would create 100,000 jobs, with the net effect of stimulating the local economy and discouraging unemployed youngsters from turning to vice. The new firm was established through the merger of five Somali companies from the trade, finance, security and telecommunications sectors. The first phase of the project is scheduled to start within six months of the establishment of the company, and will train youth to supply electricity to economic areas and communities. The second phase, which is slated to begin in mid-to-late 2011, will see the construction of factories in specially designated economic zones for the fishing, agriculture, livestock and mining industries.[129][130]

Media and telecommunications

Somalia has some of the best telecommunications systems in Africa.[131] After the start of the civil war, various new telecommunications companies began to spring up and compete to provide missing infrastructure. Funded by Somali entrepreneurs and backed by expertise from China, Korea and Europe, these nascent telecommunications firms offer affordable mobile phone and internet services that are not available in many other parts of the continent. Customers can conduct money transfers and other banking activities via mobile phones, as well as easily gain wireless internet access.[132]

After forming partnerships with multinational corporations such as Sprint, ITT and Telenor, these firms now offer the cheapest and clearest phone calls in Africa.[120] Installation time for a landline is just three days, while in Kenya to the south, waiting lists are many years long.[26] These Somali telecommunication companies also provide services to every city, town and hamlet in Somalia. There are presently around 25 mainlines per 1,000 persons, and the local availability of telephone lines (tele-density) is higher than in neighbouring countries; three times greater than in adjacent Ethiopia.[119]

Prominent Somali telecommunications companies include Golis Telecom Group, Hormuud Telecom, Somafone, Nationlink, Netco, Telcom and Somali Telecom Group. Hormuud Telecom alone grosses about $40 million a year. Despite their rivalry, several of these companies signed an interconnectivity deal in 2005 that allows them to set prices, maintain and expand their networks, and ensure that competition does not get out of control.[132]

Investment in the telecom industry is one of the clearest signs that Somalia's economy has continued to grow despite the ongoing civil strife in parts of the southern half of the country.[132] Although in need of some regulation, the sector provides invaluable communication services, and in the process, greatly facilitates job creation and income generation.[119]

As of 2005, there were also 20 privately-owned Somali newspapers, 12 radio and television stations, and numerous internet sites offering information to the public. Several local satellite-based television services transmit international news stations, such as CNN.[120] In addition, one of Somalia's upstart media firms recently established a partnership with the BBC.[120]

Military

Prior to the outbreak of the civil war in 1991 and the subsequent disintegration of the Armed Forces, Somalia's friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the largest army in Africa.[71] The creation of the Transitional Federal Government in 2004 saw the re-establishment of the Military of Somalia, which now maintains a force of 10,000 troops.

The Ministry of Defense is responsible for the Armed Forces. The Somali Navy is also being re-established, with 500 Marines currently training in Mogadishu out of an expected 5,000-strong force.[133] In addition, there are plans for the re-establishment of the Somali Air Force, with six combat and six transport planes already purchased. A new police force was also formed to maintain law and order, with the first police academy to be built in Somalia for several years opening on December 20, 2005 at Armo, 100 kilometres south of Bosaso, the commercial capital of the northeastern Puntland region.[134] Additionally, construction began in May 2010 on a new naval base in the town of Bandar Siyada, located 25km west of Bosaso. The new naval base is funded by the Puntland administration in conjunction with Saracen International, a UK-based security company. It will include a center for training recruits, and a command post for the naval force.[135]

Environment

Somalia is a semi-arid country with about 2% arable land. The civil war had a huge impact on the country’s tropical forests by facilitating the production of charcoal with ever-present, recurring, but damaging droughts. From 1971 onwards, a massive tree-planting campaign on a nationwide scale was introduced by the Siad Barre government to halt the progress of advancing sand dunes.

The first local environmental organizations were ECOTERRA Somalia and the Somali Ecological Society, both of which helped promote awareness about ecological concerns and mobilized environmental programs in all governmental sectors as well as in civil society. In 1986, the Wildlife Rescue, Research and Monitoring Centre was established by ECOTERRA Intl., with the goal of sensitizing the public to ecological issues. This sensitization effort led in 1989 to the so-called "Somalia proposal" and a decision by the Somali government to adhere to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which established for the first time a worldwide ban on the trade of elephant ivory.

Later, Fatima Jibrell, a prominent Somali environmental activist, mounted a successful campaign to salvage old-growth forests of acacia trees in the northeastern part of Somalia.[136] These trees, which can grow up to 500 years old, were being cut down to make charcoal since this so-called "black gold" is highly in demand in the Arabian Peninsula, where the region's Bedouin tribes believe the acacia to be sacred.[136][137][138] However, while being a relatively inexpensive fuel that meets a user's needs, the production of charcoal often leads to deforestation and desertification.[138] As a way of addressing this problem, Jibrell and the Horn of Africa Relief and Development Organization (Horn Relief), an organization of which she is a co-founder and Executive Director, trained a group of adolescents to educate the public on the permanent damage that producing charcoal can create. In 1999, Horn Relief coordinated a peace march in the northeastern Puntland region of Somalia to put an end to the so-called "charcoal wars." As a result of Jibrell's lobbying and education efforts, the Puntland government in 2000 prohibited the exportation of charcoal. The government has also since enforced the ban, which has reportedly led to an 80% drop in exports of the product.[139] Jibrell was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2002 for her efforts against environmental degradation and desertification.[139] In 2008, she also won the National Geographic Society/Buffett Foundation Award for Leadership in Conservation.[140]

Following the massive tsunami of December 2004, there have also emerged allegations that after the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in the late 1980s, Somalia's long, remote shoreline was used as a dump site for the disposal of toxic waste. The huge waves which battered northern Somalia after the tsunami are believed to have stirred up tonnes of nuclear and toxic waste that was illegally dumped in the country by several European firms.[141]

The European Green Party followed up these revelations by presenting before the press and the European Parliament in Strasbourg copies of contracts signed by two European companies — the Italian Swiss firm, Achair Partners, and an Italian waste broker, Progresso — and representatives of the then "President" of Somalia, the faction leader Ali Mahdi Mohamed, to accept 10 million tonnes of toxic waste in exchange for $80 million (then about £60 million).[141]

According to reports by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the waste has resulted in far higher than normal cases of respiratory infections, mouth ulcers and bleeding, abdominal haemorrhages and unusual skin infections among many inhabitants of the areas around the northeastern towns of Hobyo and Benadir on the Indian Ocean coast — diseases consistent with radiation sickness. UNEP continues that the current situation along the Somali coastline poses a very serious environmental hazard not only in Somalia but also in the eastern Africa sub-region.[141]

Demographics

Somalia has a population of around 9,832,017 inhabitants, about 85% of whom are ethnic Somalis.[2] Civil strife in the early 1990s greatly increased the size of the Somali diaspora, as many of the best educated Somalis left for the Middle East, Europe and North America.

Non-Somali ethnic minority groups make up the remainder of the nation's population and include Benadiri, Bravanese, Bantus, Bajuni, Ethiopians, Indians, Persians, Italians and Britons. Most Europeans left after independence.

There is little reliable statistical information on urbanization in Somalia. However, rough estimates have been made indicating an urbanization of 5% and 8% per annum, with many towns quickly growing into cities. Currently, 34% of the country's population live in towns and cities, with the percentage rapidly increasing.[142]

Languages

The Somali language is the official language of Somalia. It is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and its nearest relatives are the Afar and Oromo languages. Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages,[143] with academic studies of it dating from before 1900.

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Cadale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional phonemes which do not exist in Standard Somali. Maay is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans in the southern areas of Somalia.

Since Somali had long lost its ancient script,[144] a number of writing systems have been used over the years for transcribing the language. Of these, the Somali alphabet is the most widely used, and has been the official writing script in Somalia since the government of former President of Somalia Siad Barre formally introduced it in October 1972.[145]

The script was developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for the Somali language, and uses all letters of the English Latin alphabet except p, v and z. Besides Ahmed's Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing Somali include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad's writing. Indigenous writing systems developed in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Sheikh Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare, respectively.[146]

In addition to Somali, Arabic is an official national language in Somalia.[1] Many Somalis speak it due to centuries-old ties with the Arab World, the far-reaching influence of the Arabic media, and religious education.

English is also widely used and taught. Italian used to be a major language, but its influence significantly diminished following independence. It is now most frequently heard among older generations. Other minority languages include Bravanese, a variant of Swahili that is spoken along the coast by the Bravanese people.

Religion

With few exceptions, Somalis are entirely Muslims,[147] the majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi`i school of Islamic jurisprudence, although some are also adherents of the Shia Muslim denomination.[148] Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam, is also well-established, with many local jama'a (zawiya) or congregations of the various tariiqa or Sufi orders.[149] The constitution of Somalia likewise defines Islam as the religion of the Somali Republic, and Islamic sharia as the basic source for national legislation.[150]

Islam entered the region very early on, as a group of persecuted Muslims had, at Prophet Muhammad's urging, sought refuge across the Red Sea in the Horn of Africa. Islam may thus have been introduced into Somalia well before the faith even took root in its place of origin.[151]

In addition, the Somali community has produced numerous important Islamic figures over the centuries, many of whom have significantly shaped the course of Muslim learning and practice in the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and well beyond. Among these Islamic scholars is the 14th century Somali theologian and jurist Uthman bin Ali Zayla'i of Zeila, who wrote the single most authoritative text on the Hanafi school of Islam, consisting of four volumes known as the Tabayin al-Haqa’iq li Sharh Kanz al-Daqa’iq.

Christianity is a minority religion in Somalia, with no more than 1,000 practitioners in a population of over eight million inhabitants.[152] There is one diocese for the whole country, the Diocese of Mogadishu, which estimates that there were only about 100 Catholic practitioners in Somalia in 2004.[153]

In 1913, during the early part of the colonial era, there were virtually no Christians in the Somali territories, with only about 100-200 followers coming from the schools and orphanages of the few Catholic missions in the British Somaliland protectorate.[154] There were also no known Catholic missions in Italian Somaliland during the same period.[155] In the 1970s, during the reign of Somalia's then Marxist government, church-run schools were closed and missionaries sent home. There has been no archbishop in the country since 1989, and the cathedral in Mogadishu was severely damaged during the civil war.

Some non-Somali ethnic minority groups also practice animism, which represents (in the case of the Bantu) religious traditions inherited from their ancestors in southeastern Africa.[156]

Culture

Cuisine

The cuisine of Somalia varies from region to region and consists of an exotic mixture of diverse culinary influences. It is the product of Somalia's rich tradition of trade and commerce. Despite the variety, there remains one thing that unites the various regional cuisines: all food is served halal. There are therefore no pork dishes, alcohol is not served, nothing that died on its own is eaten, and no blood is incorporated. Qaddo or lunch is often elaborate.

Varieties of bariis (rice), the most popular probably being basmati, usually serve as the main dish. Spices like cumin, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and sage are used to aromatize these different rice dishes. Somalis serve dinner as late as 9 pm. During Ramadan, dinner is often served after Tarawih prayers – sometimes as late as 11 pm.

Xalwo or halva is a popular confection served during special occasions such as Eid celebrations or wedding receptions. It is made from sugar, cornstarch, cardamom powder, nutmeg powder, and ghee. Peanuts are also sometimes added to enhance texture and flavor.[157] After meals, homes are traditionally perfumed using frankincense (lubaan) or incense (cuunsi), which is prepared inside an incense burner referred to as a dabqaad.

Music

Somalia has a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic; that is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale such as the major scale. At first listen, Somali music might be mistaken for the sounds of nearby regions such as Ethiopia, Sudan or Arabia, but it is ultimately recognizable by its own unique tunes and styles. Somali songs are usually the product of collaboration between lyricists (midho), songwriters (lahan), and singers ('odka or "voice").[158]

Literature

Somali scholars have for centuries produced many notable examples of Islamic literature ranging from poetry to Hadith. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1972 as the nation's standard orthography, numerous contemporary Somali authors have also released novels, some of which have gone on to receive worldwide acclaim. Of these modern writers, Nuruddin Farah is probably the most celebrated. Books such as From a Crooked Rib and Links are considered important literary achievements, works which have earned Farah, among other accolades, the 1998 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. Farah Mohamed Jama Awl is another prominent Somali writer who is perhaps best known for his Dervish era novel, Ignorance is the enemy of love.

See also

- Adal Sultanate

- Ajuuraan State

- Anarchy in Somalia

- Borama script

- Communications in Somalia

- Dervish State

- Foreign relations of Somalia

- Gobroon Dynasty

- Greater Somalia

- Land of Punt

- List of Somalis

- List of Somali companies

- Marehan sultanate

- Military of Somalia

- Osmanya script

- Piracy in Somalia

- Scouting in Somalia

- Somali Democratic Republic

- Somali maritime history

- Somali people

- Sultanate of Hobyo

- Warsangali Sultanate

- Xeer

References

- ^ a b According to article 7 of The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic: The official languages of the Somali Republic shall be Somali (Maay and Maxaatiri) and Arabic. The second languages of the Transitional Federal Government shall be English and Italian.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Population Division (2009). "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); line feed character in|author=at position 42 (help) - ^ http://www.unicef.org/somalia/SOM_Key_Facts_and_figures28Jan09a.pdf

- ^ "Country profile: Somalia". BBC News. 18 June 2008.

- ^ Phoenicia pg 199

- ^ The Aromatherapy Book by Jeanne Rose and John Hulburd pg 94

- ^ Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El Mahdy

- ^ Ancient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.

- ^ Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan Goodwin

- ^ Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez

- ^ Man, God and Civilization pg 216

- ^ Shaping of Somali society Lee Cassanelli pg.92

- ^ Futuh Al Habash Shibab ad Din

- ^ Sudan Notes and Records – Page 147

- ^ Politics, language, and thought: the Somali experience – Page 135

- ^ Africa report pg 69

- ^ Essentials of geography and development: concepts and processes By Don R. Hoy, Leonard Berry pg 305

- ^ Encyclopedia of African history – Page 1406

- ^ The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state – Page 78

- ^ Historical dictionary of Ethiopia – Page 405

- ^ http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/anctoday/2007/text/at01.txt

- ^ Superpower diplomacy in the Horn of Africa – Page 22

- ^ a b c "The Rule of Law without the State - Spencer Heath MacCallum - Mises Daily". Mises.org. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ "http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/es.PDF" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-27.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d Benjamin Powell, Ryan Ford, Alex Nowrasteh (November 30, 2006). "Somalia After State Collapse: Chaos or Improvement?" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Somalia: Failed State, Economic Success?". Thefreemanonline.org. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, Somalia, (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.22

- ^ Prehistoric Implements from Somaliland by H. W. Seton-Karr pg 183

- ^ The Missionary review of the world – Page 132

- ^ Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London pg 447

- ^ An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition 1975, Neville Chittick pg 133

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ Breasted 1906–07, pp. 246–295, vol. 1.

- ^ Near Eastern archaeology: a reader – By Suzanne Richard pg 120

- ^ The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India pg 54

- ^ The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India pg 187

- ^ The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India pg 229

- ^ The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India pg 186

- ^ Journal of African History pg.50 by John Donnelly Fage and Roland Anthony Oliver

- ^ Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- ^ East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- ^ Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.35

- ^ The return of Cosmopolitan Capital:Globalization, the State and War pg.22

- ^ The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century By R. J. Barendse

- ^ Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.30

- ^ Chinese Porcelain Marks from Coastal Sites in Kenya: aspects of trade in the Indian Ocean, XIV-XIX centuries. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1978 pg 2

- ^ East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- ^ Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.45

- ^ Tripodi, Paolo. The Colonial Legacy in Somalia. St. Martin's Press. New York, 1999.

- ^ a b c Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106