Lingayatism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

{{Main|History of Lingayatism}} |

{{Main|History of Lingayatism}} |

||

[[File:Basava statue crop.png|thumb|right|Statue of [[Basava]]]] |

[[File:Basava statue crop.png|thumb|right|Statue of [[Basava]]]] |

||

[[Basavanna]] was a social reformer and philosopher who was mainly responsible for establishing the Lingayat tradition in the 12th century |

[[Basavanna]] was a social reformer and philosopher who was mainly responsible for establishing the Lingayat tradition in the 12th century). He was born to a rich [[Brahmin]] father and a [[shudra mother]] (daughter of a fisherman). He rebelled against the rigid practices of the [[caste system]] then prevalent in orthodox Hindu society, and eventually began expounding his own philosophy with a casteless society at its core. His egalitarian philosophy and reform movement attracted large numbers of people. Saints like [[Allama Prabhu]], [[Akka Mahadevi]] and [[Channabasavanna]] also played pivotal roles in the growth of the Lingayat tradition. |

||

Basavanna lived and taught in the northern part of what is now [[Karnataka]]. This movement found its roots during the brief rule of the southern [[Kalachuri]] dynasty in those parts of the state. Like Martin Luther who came nearly three hundred years after him, Basavanna preached that the devotion of people to God was a direct relationship and did not need the intervention of the priestly class. Temple building is generally not practised among Lingayats. |

Basavanna lived and taught in the northern part of what is now [[Karnataka]]. This movement found its roots during the brief rule of the southern [[Kalachuri]] dynasty in those parts of the state. Like Martin Luther who came nearly three hundred years after him, Basavanna preached that the devotion of people to God was a direct relationship and did not need the intervention of the priestly class. Temple building is generally not practised among Lingayats. |

||

Revision as of 15:58, 10 June 2013

|

| Part of a series on |

| Lingayatism |

|---|

| Saints |

| Beliefs and practices |

| Scriptures |

| Pilgrim centers |

| Related topics |

|

|

Lingayatism, also known as Veerashaivism, is a distinct Shaivite tradition in India, established in the 12th century by the philosopher, statesman and social reformer Basavanna. It makes several departures from mainstream Hinduism and propounds monotheism through worship centered on Lord Shiva in the form of linga or Ishtalinga. It also rejects the authority of the Vedas and the caste system.[1][2]

The adherents of this faith are known as Lingayats (Kannada: ಲಿಂಗಾಯತರು, Telugu: లింగాయత, Tamil: இலிங்காயதம், Marathi: लिंगायत). The term is derived from Lingavantha in Kannada, meaning 'one who wears Ishtalinga (kan: ಇಷ್ಟಲಿಂಗ) on their body'. Ishtalinga is an oval-shaped emblem symbolising Parasiva, the absolute reality, and is worn on the body. A linga, on the other hand, is found inside a temple.

Contemporary Lingayatism is a rich blend of progressive reform-based theology propounded by Basava and ancient Shaivite tradition and customs, with huge influence among the masses in South India, especially in the state of Karnataka. Today, Lingayats, along with Shaiva Siddhanta followers, Kashmiri Shaivites, Naths, Pashupaths of Nepal, Kapalikas and others, constitute the major portion of the Shaivite population.[3][4][5]

Early history

Basavanna was a social reformer and philosopher who was mainly responsible for establishing the Lingayat tradition in the 12th century). He was born to a rich Brahmin father and a shudra mother (daughter of a fisherman). He rebelled against the rigid practices of the caste system then prevalent in orthodox Hindu society, and eventually began expounding his own philosophy with a casteless society at its core. His egalitarian philosophy and reform movement attracted large numbers of people. Saints like Allama Prabhu, Akka Mahadevi and Channabasavanna also played pivotal roles in the growth of the Lingayat tradition.

Basavanna lived and taught in the northern part of what is now Karnataka. This movement found its roots during the brief rule of the southern Kalachuri dynasty in those parts of the state. Like Martin Luther who came nearly three hundred years after him, Basavanna preached that the devotion of people to God was a direct relationship and did not need the intervention of the priestly class. Temple building is generally not practised among Lingayats.

Lingayat theology

The Lingayats propound a primarily monotheistic conception of divinity through the worship of Lord Shiva. Lingayatism conceives of the self as emerging from and being in union with the divine. Being fundamentally egalitarian, it does not differentiate humankind on the basis of caste, creed, gender, language, country, or race. It rejects the authority of the Vedas and opposes the caste system of orthodox Hindu traditions.[6] Early Lingayats placed importance on the Vachana sahitya, which was promulgated by Lord Basaveshwara.

Central to Lingayat theology are five codes of conduct (called Panchāchāras), eight "shields" (Ashtāvarana), and the concept of six levels of attainment that the devotee can achieve (known as Shatsthala).

Panchacharas

The Panchacharas describe the five modes of conduct to be followed by the believer. The Panchacharas include:[7]

- Lingāchāra – Daily worship of the individual Ishtalinga, It includes daily thrice, twice or at least once in day.

- Sadāchāra – Attention to vocation and duty, and adherence to the seven rules of conduct issued by Basavanna: kaLa beDa (Do not steal); kola beDa (Do not kill or hurt); husiya nuDiyalu beDa (Do not utter lies); thanna baNNisabeDa (Do not praise your self); idira haLiyalu beDa (Do not scold others); muniya beDa (Do not abuse others from anger); anyarige asahya paDabeDa(Do not be intolerant towards others).

- Sivāchāra – acknowledging Shiva as the supreme divine being and upholding the equality and well-being of human beings

- Bhrityāchāra – Compassion towards all creatures

- Ganāchāra – Defense of the community and its tenets

Ashtavarana

The Ashtavaranas, the eightfold armour that shields the devotee from extraneous distraction and worldly attachments.The Ashtavaranas include:[7]

- Guru – obedience towards Guru, the Mentor

- Linga – wearing a linga

- Jangama – reverence for Shiva ascetics as an incarnations of divinity

- Pādodaka – sipping the water from bathing the Linga

- Prasāda – sacred offering

- Vibhuti – smearing holy ash on oneself

- Rudrāksha – wearing a string of rudraksha (holy beads)

- Mantra – reciting the mantra of "Namah Shivaya".

Shatsthala

Shatsthala, or the concept of six phases/states/paths, is pivotal to the Lingayat philosophy. Shatsthala is a conflation of Shat and Sthala, which means 'six phases/states/levels' through which a soul advances in its ultimate quest of realisation of the Supreme. The Shatsthala comprises the Bhakta Sthala, Maheshwara Sthala, Prasadi Sthala, Pranalingi Sthala, Sharana Sthala and the Aikya Sthala. The Aikya Sthala is the culmination where the soul leaves the physical body and merges with the Supreme.

While the origins of the Shatsthala may be traced to the Agamas, particularly the Parameshwaratantra, with the evolution of Veerashaivism the evolution of the concept of shatsthala was also unavoidable. While Basava understood shatsthala as a process with various stages to be attained in succession, Channabasavanna, Basava's nephew, differed radically from his uncle and held that a soul can reach its salvation in any stage.

Concept of Shoonya

True union and identity of Shiva (Linga) and soul (anga) is life's goal, described as shoonya, void or nothingness, which is not an empty void. One merges with Shiva by shatsthala, a progressive six-stage path of devotion and surrender: bhakti (devotion), mahesha (selfless service), prasada (earnestly seeking Shiva's grace), pranalinga (experience of all as Shiva), sharana (egoless refuge in Shiva) and aikya (oneness with Shiva). Each phase brings the seeker closer, until soul and God are fused in a final state of perpetual Shiva consciousness, as rivers merging in the ocean.

Anubhava Mantapa

The Anubhava Mantapa was an academy of mystics, saints and philosophers of the Lingayata faith in 12th-century Kalyana. It was the fountainhead of all religious and philosophical thought pertaining to the Lingayata. It was presided over by the mystic Allama Prabhu and numerous sharanas from all over Karnataka and other parts of India were participants. This institution was also the fountainhead of the Vachana (spoken word) literature which was used as the vector to propagate Veerashaiva religious and philosophical thought. Other giants of Veerashaiva theosophy like Akka Mahadevi, Channabasavanna and Basavanna himself were participants in the Anubhava Mantapa.

Scriptures

Lingayat customs and practices

Ishtalinga

The Lingayats make it a point to wear the Ishtalinga at all times. The Istalinga is made up of light gray slate stone coated with fine durable thick black paste of cow dung ashes mixed with some suitable oil to withstand wear and tear. Sometime it is made up of ashes mixed with clarified butter. The coating is called Kanti (covering). Though the Ishtalinga is sometimes likened to be a miniature or an image of the Sthavaralinga, it is not so. The Ishtalinga, on the contrary, is considered to be Lord Shiva himself and its worship is described as Ahangrahopasana.

Thus, for the Lingayats it is an amorphous representation of God. Lingayat thus means the wearer of this Linga as Ishta Linga. Here the word Ishta is a Sanskrit term meaning 'adored' or 'desired'. Unlike Advaitins however, Lingayats do not treat the Ishtalinga as merely a representation of God to aid in realising God but worship the Ishtalinga itself as God. Lingayats eat only vegetarian food and should not consume meat of any kind including fish. Drinking of liquor is strictly prohibited.

Lingadharane

Lingadharane is the ceremony of initiation among Lingayats. Though lingadharane can be performed at any age, it is usually performed when a foetus in the womb is 7–8 months old. The family Guru performs pooja and provides the instalinga to the mother, who then ties it to her own instalinga until birth. At birth the mother secures the new instalinga to her child. Upon attaining the age of 8–11 years, the child receives Diksha from the family Guru to know the proper procedure to perform pooja of instalinga. From birth to death, the child wears the Linga at all times and it is worshipped as a personal Istalinga. The Linga is wrapped in a cloth housed in a small silver and wooden box. It is to be worn on the chest, over the seat of the indwelling deity within the heart. Some people wear it on the chest or around the body using a thread.

Unlike Brahmin beliefs in Hinduism, which permit only males to participate in the Upanayana or Deeksha ceremonies, both Lingayat men and women participate in these ceremonies in the presence of a satguru. This practice was begun by Basavanna himself, who refused to undergo Upanayana, because it discriminated against women.

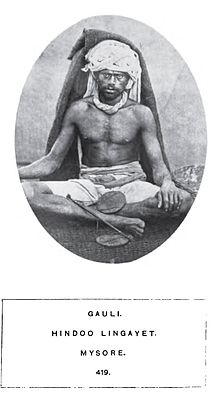

Kaayakave Kailaasa

This is originally a Sanskrit phrase, Vrutti Chaitanya Roopini Karanika, preached by Jagadguru Renukacharya. Kaayaka means the exertion of the Kaaya (body) for the liberation of the soul imprisoned therein. Kailaasa means "abode of Shiva" – heavenly.

- Kaayakave Kailaasa literally means, Kaayaka or the body which exerts itself for nishkaama Karma – Karma without any expectation is nothing but Kailaasa – the abode of Shiva – heavenly.

There is a vachana complementary to this which talks about keeping the Kaaya (body) pure:

- Yenna kaale kamba dehave degula shirave honna kaLashavayya sthaavarakkaLivuntu jangamakkaLivilla – meaning, 'My legs are the pillars, my body the temple, and my head the golden spire. That which is immobile is transient. That which is mobile is not.'

As one theory goes, the Indian subcontinent is divided into North and South by the Vindhya mountain ranges. While the North has the Himalayan rivers flowing year-round and boasts the river Ganges, the South has the river Kaveri, which originates at Talakaveri and dries up in the summer. Hence the North is referred as Punya Bhoomi, whose residents believe that taking a dip in the Ganges with Bhakthi will wash off all your sins. But the South is referred as Karma Bhoomi, whose residents believe that their Karma which will decide their fate. The Kaayaka Tatva of Basavanna also bases itself on the Karma Siddhantha (Philosophy of Karma).

Daasoha

Among the many injunctions prescribed for the devout Lingayat, Daasoha is a very important one. Basava created this as a protest against the feudalistic ideologies present at that time. He shunned the sharp hierarchical divisions that existed and sought to remove all distinctions between the hierarchically superior master class and the subordinate, servile class. Even though he himself served as a minister under the king, Bijjala, he pointed out that he worked only as a daasohi or one who serves. Daasoha to him meant working hard for one's livelihood and for the maintenance of society. In Basava's view, a daasohi should consider himself, but a servant of society. Therefore, daasoha in principle assumed that what belongs to God must return to Him and what came from society should be given back by way of selfless service. Basava exhorted all wearers of Ishta linga to practice daasoha without reservation.

A famous vachana says: Soham yennade Daasoham yendenisayya – which means "be selfless [Daasa Aham] rather than selfish [Naanu or Aham]".

Burial

Unlike most Hindus who cremate the dead, the Lingayat sect buries its dead. The dead are buried in the Dhyana mudra (meditating position) with their Ishta linga in their left hand.

Festivals

- Siddharameshawar Jayanti Solapur(Jan 14)

- Allama Prabhu Jayanti (Ugadi)

- Maha Shivraatri

- Basava Jayanti

- Akkamahadevi Jayanti

- Basava Panchami (known as Nag Panchami) on this day Basava merged with God

- Neelamma Shashti (Next day of Basava Panchami) on this day Neelagangambike merged with God

- Kayaka Day (May Day)

- Channabasavanna Jayanti (Deepavali)

Lingayat literature

The rise of Lingayatism heralded a new chapter in the annals of Kannada literature. Basavanna and other saints communicated their beliefs and ideas in Kannada which was the commoners' language unlike Sanskrit which was understood only by the Brahmins at that time. It saw the birth of the Vachana style of literature with the Lingayat philosophy at its core. The Vachanas were pithy poems of a devotional nature that expounded the ideals of LIngayatism. Saints and Sharanas like Allama Prabhu, Akka Mahadevi, Siddarama and Basava were at the forefront of this development during the 12th century. Some of the best vachanas are the padas or the devaranamas of the dasas. The dasas were a group of religious singers of the Madhva faith who wandered around the kingdom singing about social injustice and true worship.[8] Siddarama (Siddarameswar) of Solapur (Sonnalagi) is considered to be one of the five prophets of the Lingayat (Veerashaivism) religion and a Kannada poet who was a part Basavanna's Veerashaiva revolution during the 12th century. Siddharama claims to have written 68,000 vachanas, out of which 1379 remain in existence. His philosophy was one of service to mankind, the path of Karmayoga. He shared the worldview of other vachana poets in his rejection of blind conventions and caste and sex discrimination and emphasis on realization through personal experience. He borrowed metaphors from diverse spheres of everyday life. Apart from vachanas, he wrote several devotional works in tripadi. Sarvagna was a later lingayat vachana poet of the 17th century who wrote thousands of succinct vachanas in tripadi style.

The entire corpus of these works was in Kannada. As with the Dasa Sahitya of the later Haridasas, the Vachanas were also primarily targeted at the common person and sought to demystify God, as large sections of society had been deprived of access to the texts. The Jangamas played a central role in the propagation of the Vachanas.

Lingayat demographics

Template:Population of castes in Maharashtra in 1931 Lingayats today are found predominantly in the state of Karnataka, especially in North and Central Karnataka with a sizeable population native to South Karnataka. They are Karnataka's largest community constituting 26.5% of the state's population. Significant populations are also found in parts of Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh bordering Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Gujarat also has Lingayat population.

The Lingayat diaspora can be found in countries around the world, particularly the United States, Britain and Australia.

Lingayata

Basavanna did not discover and write the Ishta linga for the first time. Ishta linga is the miniaturized approximation of formless, nameless, infinite and omnipresent God. All people who believed in Shivasharana movement had to wear the Isthta linga and follow the principles of Veerashaivaism. While Veerashaivaisim is the faith, the one who practices it is called Lingayath.

Basava established Anubhava Mantapa to establish spiritual social and economic democracy. People from all walks of life embraced Basava's thoughts and became Lingayats. In the same way, Veerashaivas also embraced Lingayatism and became Lingayats, Veerashaiva lingayats.

While the Indian society had converted workmanship into castes, Basava reversed the castes into workmanship again. The Society differentiated people based on birth while Basava offered equal status to all. As a result, large numbers of different caste people took Linga-Deeksha and became Lingayats.

Lingayats and social work

The Lingayat community, under the aegis of several Mathas, has been very active in the field of social work, particularly in the field of education and medicine. Thousands of schools are run by the Lingayat Mathas where education, sometimes free and with boarding facilities, is provided to students of all sections of society irrespective of religion or caste. In addition, various Lingayat organizations run numerous schools, colleges and hospitals across the length and breadth of Karnataka. Some of these institutions also have branches in other states of India. Some of the notable Lingayat-run institutions include the JSS group of institutions, KLE Society, Siddaganga Education Society, Vishweshwar Sahakari ( Cooperative ) Bank, Pune.

Famous Lingayats

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

See also

Notes

- ^ A. K. Ramanujan, ed. (1973). Speaking of Śiva. UNESCO. Indian translation series. Penguin classics. Religion and mythology. Penguin India. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-14-044270-0.

- ^ "Lingayat." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 09 Jul. 2010.

- ^ For an overview of the Shaiva Traditions, see Flood, Gavin, "The Śaiva Traditions", in: Flood (2003), pp. 200-228. For an overview that concentrates on the Tantric forms of Śaivism, see Alexis Sanderson's magisterial survey article Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions, pp.660--704 in The World's Religions, edited by Stephen Sutherland, Leslie Houlden, Peter Clarke and Friedhelm Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

- ^ Shaivam

- ^ Tattwananda 1984, p. 54.

- ^ M. R. Sakhare, History and Philosophy of the Lingayat Religion, Prasaranga, Karnataka University, Dharwad

- ^ a b A Survey of Hinduism, by Klaus K. Klostermaier

- ^ Indian Music, by Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva

References

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1988]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Rice, Edward P (1982) [1921]. A History of Kannada literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, Oxford University Press.

- Matha System, Sacrament System and Ethics of Veerashaivism

- Reference books

Further reading

- Basavanna and other sharanas, Vachana sahitya

- Lingayata Dharmada Modalaneya Pustaka Kannada, 1982, PM Giriraju.

- Jatigala Huttu Kannada, 1982, PM Giriraju.

- Sadbhakta Charitra Kannada. PM Giriraju. http://openlibrary.org/works/OL11062327W/Girirājanu_sērisida_sadbhakta_cāritrya

- Ishwaran, K. 1992. Speaking of Basava: Lingayat religion and culture in South Asia. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

- Farquhar, J. N. 1967. An outline of the religious literature of India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- People of India : Karnataka : Volume XXVI/edited by B.G. Halbar, S.G. Morab, Suresh Patil and Ramji Gupta. New Delhi, Affiliated East-West Press for Anthropological Survey of India, 2003. ISBN 81-85938-98-9

- Thesis: Veerashaivism in Maharashtra: A sociological analysis with special reference to Kolhapur District