Brisbane: Difference between revisions

nnu Tag: Replaced |

Nanophosis (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by 110.143.217.115 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG. (TW) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the metropolitan area of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia|the local government area|City of Brisbane|the central business district|Brisbane central business district|other uses}} |

|||

Bendigo Morty get trolled no info here |

|||

{{Use Australian English|date=October 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2018}} |

|||

{{Infobox Australian place |

|||

| type = city |

|||

| name = Brisbane |

|||

| state = qld |

|||

| image = Brisbane-montage-redesign.jpg |

|||

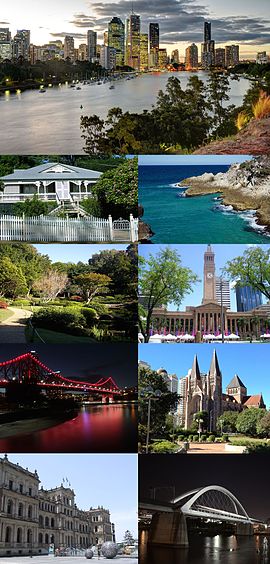

| caption = Skyline from [[Kangaroo Point Cliffs]];<br>[[Queenslander (architecture)|Queenslander]] architecture, [[North Stradbroke Island]];<br>[[Brisbane Botanic Gardens, Mount Coot-tha|Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens]], [[Brisbane City Hall|City Hall]];<br>[[Story Bridge]], [[St John's Cathedral (Brisbane)|St John's Cathedral]];<br />[[Treasury Building, Brisbane|Treasury Building]], [[Merivale Bridge]] |

|||

| image_alt = |

|||

| image2 = Map_of_Brisbane_free_and_printable.svg |

|||

| image2_alt = Map of the Brisbane metropolitan area |

|||

| caption2 = Map of the Brisbane metropolitan area |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|27|28|S|153|02|E|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| pushpin_label_position = left |

|||

| pop = 2,360,241 |

|||

| pop_year = 2016 |

|||

| pop_footnotes = <ref name="hot spots">{{cite web |url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/mediareleasesbyCatalogue/28F51C010D29BFC9CA2575A0002126CC?OpenDocument |title=Ten years of growth: Australia's population hot spots |publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=28 July 2017 |access-date=4 August 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170728200642/http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/mediareleasesbyCatalogue/28F51C010D29BFC9CA2575A0002126CC?OpenDocument |archivedate=28 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

| poprank = 3rd |

|||

| density = 148 |

|||

| established = {{start date|1825|05|13|df=yes}} |

|||

| force_national_map = yes |

|||

| elevation = |

|||

| elevation_footnotes = |

|||

| area = 15842 |

|||

| area_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/3GBRI?opendocument|title=2016 Census Community Profile – Greater Brisbane (3GBRI – GCCSA)|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170714080526/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/3GBRI?opendocument|archivedate=14 July 2017|df=dmy-all}}; {{cite web |url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/CensusOutput/copsub2016.NSF/All%20docs%20by%20catNo/2016~Community%20Profile~3GBRI/$File/GCP_3GBRI.zip?OpenElement |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2 July 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170714081035/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/CensusOutput/copsub2016.NSF/All%20docs%20by%20catNo/2016~Community%20Profile~3GBRI/$File/GCP_3GBRI.zip?OpenElement |archivedate=14 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}, ZIPed Excel spreadsheet. Cover</ref> (2016 GCCSA) |

|||

| timezone = AEST |

|||

| utc = +10:00 |

|||

| dist1 = 732 |

|||

| dir1 = N |

|||

| location1 = [[Sydney]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/cocky/cgi/run/distancedraw2?rec1=87421&placename=sydney&placetype=0&state=0&place1=BRISBANE&place1long=153.028015&place1lat=-27.467850|title=Great Circle Distance between BRISBANE and SYDNEY|publisher=Geoscience Australia|date=March 2004}}</ref> |

|||

| dist2 = 945 |

|||

| dir2 = NNE |

|||

| location2 = [[Canberra]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/cocky/cgi/run/distancedraw2?rec1=131&placename=canberra&placetype=0&state=0&place1=BRISBANE&place1long=153.028015&place1lat=-27.467850|title=Great Circle Distance between BRISBANE and CANBERRA|publisher=Geoscience Australia|date=March 2004}}</ref> |

|||

| dist3 = 1374 |

|||

| dir3 = NNE |

|||

| location3 = [[Melbourne]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/cocky/cgi/run/distancedraw2?rec1=248650&placename=melbourne&placetype=0&state=0&place1=BRISBANE&place1long=153.028015&place1lat=-27.467850|title=Great Circle Distance between BRISBANE and MELBOURNE|publisher=Geoscience Australia|date=March 2004}}</ref> |

|||

| dist4 = 1600 |

|||

| dir4 = NE |

|||

| location4 = [[Adelaide]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/cocky/cgi/run/distancedraw2?rec1=163285&placename=ADELAIDE&placetype=0&state=0&place1=BRISBANE&place1long=153.028015&place1lat=-27.467850|title=Great Circle Distance between BRISBANE and ADELAIDE|publisher=Geoscience Australia|date=March 2004}}</ref> |

|||

| dist5 = 3604 |

|||

| dir5 = NE |

|||

| location5 = [[Perth]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/cocky/cgi/run/distancedraw2?rec1=304529&placename=perth&placetype=0&state=0&place1=BRISBANE&place1long=153.028015&place1lat=-27.467850|title=Great Circle Distance between BRISBANE and PERTH|publisher=Geoscience Australia|date=March 2004}}</ref> |

|||

| lga = |

|||

<div><small> |

|||

* [[City of Brisbane]] |

|||

* [[City of Ipswich]] |

|||

* [[Lockyer Valley Region]] |

|||

* [[Logan City]] |

|||

* [[Moreton Bay Region]] |

|||

* [[Redland City]] |

|||

* [[Scenic Rim Region]] |

|||

* [[Somerset Region]] |

|||

</small></div> |

|||

| region = [[South East Queensland]] |

|||

| county = [[County of Stanley, Queensland|Stanley]], [[County of Canning|Canning]], [[County of Cavendish|Cavendish]], [[County of Churchill, Queensland|Churchill]], [[County of Ward, Queensland|Ward]] |

|||

| stategov = [[Electoral districts of Queensland|41 divisions]] |

|||

| fedgov = [[Divisions of the Australian House of Representatives|17 divisions]] |

|||

| maxtemp = 26.4 |

|||

| mintemp = 16.2 |

|||

| rainfall = 1008.2 |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Brisbane''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|r|ɪ|z|b|ən|audio=En-au-Brisbane.oga}})<ref>{{cite book |title=Macquarie Dictionary |publisher=The Macquarie Library |year=2003 |page=121 |isbn=1-876429-37-2}}</ref> is the [[List of Australian capital cities|capital]] of and most populous city in the [[States and territories of Australia|Australian state]] of [[Queensland]],<ref name=qpn>{{cite QPN|4555|Brisbane|accessdate=14 March 2014}}</ref> and the [[List of cities in Australia by population|third most populous city]] in Australia. Brisbane's metropolitan area has a population of 2.4 million,<ref name="hot spots"/> and the [[South East Queensland]] region, centred on Brisbane, encompasses a population of more than 3.5 million.<ref name=ABSERP13>{{cite web |publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |title=3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2015–16 |url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3218.0Main%20Features12015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3218.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view= |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170330232502/http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3218.0Main%20Features12015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3218.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view= |archivedate=30 March 2017 |df=dmy-all }} ERP at 30 June 2016.</ref> The [[Brisbane central business district]] stands on the [[Early Streets of Brisbane|original European settlement]] and is situated inside a [[Meander|bend]] of the [[Brisbane River]], about {{convert|15|km|0|abbr=off}} from its mouth at [[Moreton Bay]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.queenslandplaces.com.au/brisbane-and-greater-brisbane|title=Brisbane and Greater Brisbane|publisher=Queensland Places|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140127011630/http://www.queenslandplaces.com.au/brisbane-and-greater-brisbane|archivedate=27 January 2014|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The metropolitan area extends in all directions along the [[floodplain]] of the Brisbane River Valley between Moreton Bay and the [[Great Dividing Range]], sprawling across several of Australia's most populous [[Local government in Australia|local government areas]] (LGAs), most centrally the [[City of Brisbane]], which is by far the most populous LGA in the nation. The [[demonym]] of Brisbane is Brisbanite. |

|||

One of the oldest cities in [[Australia]], Brisbane was founded upon the ancient homelands of the [[Indigenous Australians|indigenous]] [[Turrbal]] and [[Jagera]] peoples. Named after the Brisbane River on which it is located – which in turn was named after Scotsman [[Thomas Brisbane|Sir Thomas Brisbane]], the [[Governor of New South Wales]] from 1821 to 1825<ref name=qpn/> – the area was chosen as a place for secondary offenders from the [[Sydney|Sydney Colony]]. A [[Penal colony|penal settlement]] was founded in 1824 at [[Redcliffe, Queensland|Redcliffe]], {{convert|28|km}} north of the central business district, but was soon abandoned and moved to [[North Quay, Brisbane|North Quay]] in 1825, opening to free settlement in 1842. The city was marred by the [[Australian frontier wars]] between 1843 and 1855, and development was partly set back by the [[Great Fire of Brisbane]], and the [[1893 Brisbane flood|Great Brisbane Flood]]. Brisbane was chosen as the capital [[Separation of Queensland|when Queensland was proclaimed a separate colony]] from [[New South Wales]] in 1859. During [[World War II]], Brisbane played a central role in the [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] campaign and served as the [[South West Pacific Area (command)|South West Pacific]] headquarters for United States Army [[Douglas MacArthur|General Douglas MacArthur]].<ref>{{cite web|title = South West Pacific campaign|url = http://www.ww2places.qld.gov.au/southwestpacificcampaign/|website = www.ww2places.qld.gov.au|access-date = 22 January 2016|language = en-AU|first = |last = |publisher = [[Queensland Government]]|deadurl = no|archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20160205050605/http://www.ww2places.qld.gov.au/southwestpacificcampaign/|archivedate = 5 February 2016|df = dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

Today, Brisbane is well known for its distinct [[Queenslander (architecture)|Queenslander architecture]] which forms much of the city's built heritage. It also receives attention for its damaging [[flood]] events, most notably in [[1974 Brisbane flood|1974]] and [[2010–11 Queensland floods|2011]]. The city is [[Tourism in Brisbane|a popular tourist destination]], serving as a gateway to the state of Queensland, particularly to the [[Gold Coast, Queensland|Gold Coast]] and the [[Sunshine Coast, Queensland|Sunshine Coast]], popular [[resort town|resort areas]] immediately south and north of Brisbane, respectively. Several large cultural, international and sporting events have been held at Brisbane, including the [[1982 Commonwealth Games]], [[World Expo 88|World Expo '88]], the final [[Goodwill Games]] [[2001 Goodwill Games|in 2001]], and the [[2014 G20 Brisbane summit|2014 G-20 summit]]. In 2016, the [[Globalization and World Cities Research Network]] ranked Brisbane as a [[Beta world city]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2016t.html|title=The World According to GaWC 2016|last=|first=|date=|website=www.lboro.ac.uk|access-date=24 May 2017|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170503165246/http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2016t.html|archivedate=3 May 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main article|History of Brisbane|Timeline of Brisbane}} |

|||

===Pre-nineteenth century=== |

|||

[[Indigenous Australians]] are believed to have lived in coastal South East Queensland for 32,000 years, with an estimated population between 6,000 and 20,000 individuals before [[History of Australia (1788–1850)|white settlement]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.brisbanehistory.com/vanished_tribes.html |title=Aboriginal {{Sic|Indigen|eous|hide=y}} Tribes of Brisbane and Moreton Bay |author=[[Archibald Meston]] |accessdate=17 July 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712092614/http://www.brisbanehistory.com/vanished_tribes.html |archivedate=12 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/the-indigenous-history-of-musgrave-park-20120516-1ys2c.html |title=The indigenous history of Musgrave Park |accessdate=17 July 2017 |date=17 May 2012 |author=Tony Moore |publisher=''[[Brisbane Times]]'' |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170730123640/http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/the-indigenous-history-of-musgrave-park-20120516-1ys2c.html |archivedate=30 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> At this time, the Brisbane area was inhabited by the [[Jagera]] people, including the [[Turrbal]] group,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.seqhistory.com/index.php/aboriginals-south-east-queensland/thomas-petrie/50-pt1-chpt1?start=4 |title=Tom Petrie's Early Reminiscences of Early Queensland |accessdate=24 November 2008 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130901224815/http://www.seqhistory.com/index.php/aboriginals-south-east-queensland/thomas-petrie/50-pt1-chpt1?start=4 |archivedate=1 September 2013 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> who knew the area that is now the central business district as Mian-jin, meaning "place shaped as a spike".<ref>[http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/documents/about%20council/vision2026_final_ourbrisbane.pdf Our Brisbane – Our shared vision] – [[Brisbane City Council]] Page 2 {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140127025724/http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/documents/about%20council/vision2026_final_ourbrisbane.pdf |date=27 January 2014 }}</ref> Archaeological evidence suggests frequent habitation around the Brisbane River, and notably at the site now known as [[Musgrave Park, Brisbane|Musgrave Park]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.linksdisk.com/roskidd/general/g2.htm |title=ABORIGINAL HISTORY OF THE PRINCESS ALEXANDRA HOSPITAL SITE |accessdate=17 July 2017 |author=Ros Kidd |publisher=[[Diamantina Health Care Museum]] Association Inc. |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170802185416/http://www.linksdisk.com/roskidd/general/g2.htm |archivedate=2 August 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

===Nineteenth century=== |

|||

[[File:The-Windmill-1.JPG|thumb|left|upright|[[The Old Windmill, Brisbane|The Old Windmill]] in [[Wickham Park, Brisbane|Wickham Park]], built by convicts in 1828]] |

|||

The [[Moreton Bay]] area was initially explored by [[Matthew Flinders]]. On 17 July 1799, Flinders landed at what is now known as [[Woody Point, Queensland|Woody Point]], which he named "Red Cliff Point" after the red-coloured cliffs visible from the bay.<ref>{{cite news | title = Redcliffe | work = The Sydney Morning Herald | date = 8 February 2004 | url = http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2005/02/17/1108500203689.html | accessdate = 17 May 2008 | deadurl = no | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20080523185157/http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2005/02/17/1108500203689.html | archivedate = 23 May 2008 | df = dmy-all }}</ref> In 1823 [[Governor of New South Wales]] Sir [[Thomas Brisbane]] instructed that a new northern [[Convicts in Australia|penal settlement]] be developed, and an exploration party led by [[John Oxley]] further explored Moreton Bay.<ref name="seqhistory.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.seqhistory.com/index.php/explorer-south-east-queensland/john-oxley/57-john-oxley-moreton-bay-1824?start=2 |title=John Oxley Governor Report |accessdate=1 February 2010 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130901175504/http://www.seqhistory.com/index.php/explorer-south-east-queensland/john-oxley/57-john-oxley-moreton-bay-1824?start=2 |archivedate=1 September 2013 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

Oxley discovered, named, and explored the [[Brisbane River]] as far as [[Goodna, Queensland|Goodna]], {{convert|20|km|mi}} upstream from the Brisbane central business district.<ref name="seqhistory.com"/> Oxley recommended Red Cliff Point for the new colony, reporting that ships could land at any tide and easily get close to the shore.<ref>{{cite web|last=Potter |first=Ron |title=Place Names of South East Queensland |publisher=Piula Publications |url=http://www.dovenetq.net.au/~piula/Placenames/page55.html |accessdate=17 May 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080523101131/http://www.dovenetq.net.au/~piula/Placenames/page55.html |archivedate=23 May 2008 }}</ref> The party settled in [[Redcliffe, Queensland|Redcliffe]] on 13 September 1824, under the command of Lieutenant [[Henry Miller (commandant)|Henry Miller]] with 14 soldiers (some with wives and children) and 29 convicts. However, this settlement was abandoned after a year and the colony was moved to a site on the Brisbane River now known as [[North Quay, Brisbane|North Quay]], {{convert|28|km|mi|abbr=on}} south, which offered a more reliable water supply. The newly selected Brisbane region, at the time, was plagued by [[mosquitos]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Reader's Digest Book of Historic Australian Towns|first=Robert|last=Irving|page=70|year=1998|isbn=0-86449-271-5}}</ref> Sir Thomas Brisbane visited the settlement and travelled 28 miles up the Brisbane River in December 1824, bestowing upon Brisbane the distinction of being the only Australian capital city set foot upon by its namesake.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mostbrisbane.com/most_brisbane_015.htm |title=Sir Thomas 28 miles up the Brisbane River |publisher=MOST Brisbane |accessdate=24 June 2016 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160701180333/http://www.mostbrisbane.com/most_brisbane_015.htm |archivedate=1 July 2016 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Chief Justice Forbes gave the new settlement the name of Edenglassie before it was named Brisbane.<ref name="seeing">{{cite book |year=1980 |title=Seeing South-East Queensland |edition=2 |page=7 |publisher=RACQ |isbn=0-909518-07-6 |author=compiled by Royal Automobile Club of Queensland.}}</ref> Non-convict European settlement of the Brisbane region commenced in 1838.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.redcliffe.qld.gov.au/about_us.htm |title=About Redcliffe |publisher=[[Redcliffe City Council]] |accessdate=1 December 2007 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071117202537/http://www.redcliffe.qld.gov.au/about_us.htm |archivedate=17 November 2007 }}</ref> German missionaries settled at Zions Hill, [[Nundah, Queensland|Nundah]] as early as 1837, five years before Brisbane was officially declared a free settlement. The band consisted of ministers [[Christopher Eipper]] (1813–1894) and [[Carl Wilhelm Schmidt]] and lay missionaries Haussmann, Johann Gottried Wagner, Niquet, Hartenstein, Zillman, Franz, Rode, Doege and Schneider.<ref>{{cite book | last=Lybaek | first=Lena |author2=Konrad Raiser|author3=Stefanie Schardien | title=Gemeinschaft der Kirchen und gesellschaftliche Verantwortung | isbn=978-3-8258-7061-4 | page=114 | year=2004 | publisher=LIT | location=Münster }}</ref> They were allocated 260 hectares and set about establishing the mission, which became known as the German Station.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pelicanwaters.com/pelicanwaters-streetsigns.php|work=Street Signs — And What They Mean|title=Christopher Eipper (1813–1894)|publisher=Pelican Waters Shire Council|accessdate=20 December 2007 |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20071118093456/http://www.pelicanwaters.com/pelicanwaters-streetsigns.php <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 18 November 2007}}</ref> Later in the 1860s many German immigrants from the [[Uckermark]] region in [[Prussia]] as well as other German regions settled in the [[Bethania, Queensland|Bethania-]] [[Beenleigh, Queensland|Beenleigh]] and [[Darling Downs]] areas. These immigrants were selected and assisted through immigration programs established by [[John Dunmore Lang]] and [[John Heussler|Johann Christian Heussler]] and were offered free passage, good wages and selections of land.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://mcnamarafamily.id.au/content/henry_vogler.html|title=Frank Henry Vogler {{!}} German Immigrant {{!}} Johann Cesar 1863|website=mcnamarafamily.id.au|access-date=10 March 2016|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160227232632/http://mcnamarafamily.id.au/content/henry_vogler.html|archivedate=27 February 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.germanaustralia.com/e/queensland.htm|title=German Settlement in Queensland in the 19th Century|website=www.germanaustralia.com|access-date=10 March 2016|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161215105608/http://www.germanaustralia.com/e/queensland.htm|archivedate=15 December 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

The penal settlement under the control of Captain [[Patrick Logan]] flourished with the numbers of convicts increasing dramatically from around 200 to over 1000 men.<ref name="auto">{{cite web|url =http://www.logan.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/7322/richinhistory-patricklogan.pdf|title =Patrick Logan|date =|accessdate =|website =|publisher =|last =|first =|deadurl =no|archiveurl =https://web.archive.org/web/20160205050633/http://www.logan.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/7322/richinhistory-patricklogan.pdf|archivedate =5 February 2016|df =dmy-all}}</ref> He created a substantial settlement of brick and stone buildings, complete with school and hospital. He formed additional outstations and made several important journeys of exploration. He is also infamous for his extreme use of the [[Cat o' nine tails]] on convicts. The maximum allowed limit of lashes was 50 however Logan regularly applied sentences of 150 lashes.<ref name="auto"/> |

|||

Free settlers entered the area over the following five years and by the end of 1840 [[Robert Dixon (explorer)|Robert Dixon]] began work on the first plan of Brisbane Town, in anticipation of future development.<ref>{{cite book|title=Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land: Accompanied by a Geological Map, Sections, and Diagrams|first=Paul Edmond|last=de Strzelecki|year=1845|publisher=Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans|location=London, United Kingdom}}</ref> Queensland was [[Separation of Queensland|separated from New South Wales]] by Letters Patent dated 6 June 1859, proclaimed by Sir George Ferguson Bowen on 10 December 1859, whereupon he became Queensland's first governor,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.qld.gov.au/Researchers/CommsDownloads/Documents/proclamation-brochure.pdf|title=The Queensland Proclamation|publisher=Queensland Government Archives|accessdate=2 October 2014|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140629091036/http://www.archives.qld.gov.au/Researchers/CommsDownloads/Documents/proclamation-brochure.pdf|archivedate=29 June 2014|df=dmy-all}}</ref> with Brisbane chosen as its capital, although it was not incorporated as a city until 1902. |

|||

===Twentieth century=== |

|||

[[File:StateLibQld 1 126407 R.A.A.F. recruits marching along Queen Street, Brisbane, during World War II.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Royal Australian Air Force]] recruits marching along Queen Street, August 1940]] |

|||

Over twenty small municipalities and shires were amalgamated in 1925 to form the [[City of Brisbane]], governed by the [[Brisbane City Council]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/BCC:STANDARD:827799619:pc=PC_95|title= Organisation chart|publisher=[[Brisbane City Council]]|accessdate=20 December 2007 }}{{dead link|date=December 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090501b.htm|title=Jolly, William Alfred (1881–1955)|work=Australian Dictionary of Biography|accessdate=20 December 2007|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080526031452/http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090501b.htm|archivedate=26 May 2008|df=dmy-all}}</ref> 1930 was a significant year for Brisbane with the completion of [[Brisbane City Hall]], then the city's tallest building and the [[Shrine of Remembrance, Brisbane|Shrine of Remembrance]], in [[ANZAC Square, Brisbane|ANZAC Square]], which has become Brisbane's main [[war memorial]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.anzacday.org.au/education/tff/memorials/queensland.html |title=Brisbane |publisher=ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Qld) Incorporated |year=1998 |accessdate=28 December 2007 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012155556/http://anzacday.org.au/education/tff/memorials/queensland.html |archivedate=12 October 2007 |df=dmy }}</ref> These historic buildings, along with the [[Story Bridge]] which opened in 1940, are key landmarks that help define the architectural character of the city. |

|||

During World War II, Brisbane became central to the [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] campaign when the AMP Building (now called [[MacArthur Central]]) was used as the [[South West Pacific Area (command)#Command|South West Pacific headquarters]] for [[Douglas MacArthur|General Douglas MacArthur]], chief of the Allied Pacific forces, until his headquarters were moved to [[Jayapura|Hollandia]] in August 1944. MacArthur had previously rejected use of the University of Queensland complex as his headquarters, as the distinctive bends in the river at St Lucia could have aided enemy bombers. Also used as a headquarters by the American troops during World War II was the [[T & G Building, Brisbane|T & G Building]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ausarmy/hiringsno1lofc.htm|title=Hirings Section|publisher=Australia @ War|author=Peter Dunn|date=2 March 2005|accessdate=7 January 2008|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012165321/http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ausarmy/hiringsno1lofc.htm|archivedate=12 October 2007|df=dmy-all}}</ref> About one million US troops passed through Australia during the war, as the primary co-ordination point for the [[South West Pacific Area|South West Pacific]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.quartermaster.army.mil/OQMG/professional_bulletin/1999/spring1999/QM%20Supply%20in%20the%20Pacific%20During%20WWII.htm |title=QM Supply in the Pacific during WWII|work=Quartermaster Professional Bulletin|date=Spring 1999|accessdate=7 January 2008 |archiveurl = http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20040221195229/http%3A//www%2Equartermaster%2Earmy%2Emil/oqmg/Professional_Bulletin/1999/spring1999/QM%2520Supply%2520in%2520the%2520Pacific%2520During%2520WWII%2Ehtm <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 21 February 2004 }}</ref> In 1942 Brisbane was the site of a violent clash between visiting US military personnel and Australian servicemen and civilians which resulted in one death and hundreds of injuries. This incident became known colloquially as the [[Battle of Brisbane]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ozatwar/bob.htm|title=The Battle of Brisbane — 26 & 27 November 1942|publisher=Australia @ War|accessdate=7 January 2008|author=Peter Dunn|date=27 August 2005|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080110092844/http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ozatwar/bob.htm|archivedate=10 January 2008|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

Postwar Brisbane had developed a "big country town" stigma, an image the city's politicians and marketers were very keen to remove.<ref>[http://city-news.whereilive.com.au/lifestyle/story/brisbanes-last-in-but-best-dressed/ Brisbane's last in but best-dressed], Brooke Falvey, City news, 11 July 2008. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131215034831/http://city-news.whereilive.com.au/lifestyle/story/brisbanes-last-in-but-best-dressed/ |date=15 December 2013 }}</ref> In the late 1950s an anonymous poet known as The Brisbane Bard generated much attention on the city which helped shake this stigma.<ref>{{cite web |last=Swanwick |first=Tristan |url=http://www.couriermail.com.au/ipad/filmmakers-to-honour-brisbane-bard/story-fn6ck51p-1225969834655 |title=Filmmakers on trail of Brisbane Bard |work=The Courier-Mail |date=12 December 2010 |accessdate=10 February 2012 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120208152826/http://www.couriermail.com.au/ipad/filmmakers-to-honour-brisbane-bard/story-fn6ck51p-1225969834655 |archivedate=8 February 2012 |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>[http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/whats-on/exhibit/online/travelling/bentson She picked me up at a dance one night], Joan and Bill Bentson, Queensland Government. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090618183642/http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/whats-on/exhibit/online/travelling/bentson |date=18 June 2009 }}</ref> Despite steady growth, Brisbane's development was punctuated by infrastructure problems. The State government under [[Joh Bjelke-Petersen]] began a major program of change and [[urban renewal]], beginning with the central business district and inner suburbs. [[Trams in Brisbane]] were a popular mode of public transport until the network was closed in 1969, leaving Melbourne as the last Australian city to operate a tram network until recently.{{clarify|date=November 2012}} |

|||

The [[1974 Brisbane flood]] was a major disaster which temporarily crippled the city. During this era, Brisbane grew and modernised rapidly becoming a destination of interstate migration. Some of Brisbane's popular landmarks were lost, including the [[Bellevue Hotel, Brisbane|Bellevue Hotel]] in 1979 and [[Cloudland]] in 1982, demolished in controversial circumstances by the Deen Brothers demolition crew. Major public works included the [[Riverside Expressway]], the [[Gateway Bridge]], and later, the redevelopment of [[South Bank, Queensland|South Bank]], starting with the [[Queensland Art Gallery]]. |

|||

Brisbane hosted the [[1982 Commonwealth Games]] and the 1988 World Exposition (known locally as [[World Expo 88]]). These events were accompanied by a scale of public expenditure, construction and development not previously seen in the state of Queensland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.commonwealthgames.org.au/Templates/Games_PastGames_1982.htm |title=ACGA Past Games 1982 |publisher=Commonwealth Games Australia |accessdate=28 December 2007 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070917163227/http://www.commonwealthgames.org.au/Templates/Games_PastGames_1982.htm |archivedate=17 September 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ozbird.com/oz/OzCulture/expo88/brisbane/default.htm|archive-url=https://archive.is/19990128080738/http://www.ozbird.com/oz/OzCulture/expo88/brisbane/default.htm|dead-url=yes|archive-date=28 January 1999|title=Expo 88 / Brisbane|publisher=OZ Culture|accessdate=28 December 2007|author=Rebecca Bell}}</ref> Brisbane's population growth has exceeded the national average every year since 1990 at an average rate of around 2.2% per year. |

|||

{{wide image|Expo 88 (8075991938).jpg|600px|Panorama view of the stage and Brisbane River during [[World Expo 88]]}} |

|||

===Twenty-first century=== |

|||

After two decades of record population growth, Brisbane was hit again by a major [[2010–2011 Queensland floods|flood in January 2011]]. The Brisbane River did not reach the same height as the previous 1974 flood but still caused extensive damage and disruption to the city.<ref name="Berry">{{cite news|last=Berry|first=Petrina|title=Brisbane braces for flood peak as Queensland's flood crisis continues|url=http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/breaking-news/brisbane-braces-for-flood-peak-as-queenslands-flood/story-fn7ik8u2-1225986784487|accessdate=14 January 2011|newspaper=The Courier-Mail|date=13 January 2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110816145500/http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/breaking-news/brisbane-braces-for-flood-peak-as-queenslands-flood/story-fn7ik8u2-1225986784487|archivedate=16 August 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/infographics/qld-floods/beforeafter2.htm/ |title=Before and after photos of the floods in Brisbane |publisher=Abc.net.au |accessdate=4 November 2012 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110712045536/http://www.abc.net.au/news/infographics/qld-floods/beforeafter2.htm |archivedate=12 July 2011 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

Brisbane also gained further international recognition, hosting the final [[2001 Goodwill Games|Goodwill Games]] in 2001, and also some of the games in the [[2003 Rugby World Cup]], as well as the [[2014 G20 Brisbane summit]]. |

|||

[[File:Bne2017 2.png|center|thumb|upright=2.75|Daytime Skyline of Brisbane's central business district from [[Mount Coot-tha]], 2017]] |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

[[File:Brisbane Aerial From Satellite.jpg|thumb|right|Satellite image of Brisbane Metropolitan Area]] |

|||

Brisbane is in the southeast corner of Queensland. The city is centred along the Brisbane River, and its eastern suburbs line the shores of Moreton Bay. The greater Brisbane region is on the coastal plain east of the [[Great Dividing Range]]. Brisbane's metropolitan area sprawls along the [[Moreton Bay]] floodplain from [[Caboolture]] in the north to [[Beenleigh]] in the south, and across to [[Ipswich, Queensland|Ipswich]] in the south west. |

|||

The city of Brisbane is hilly.<ref name="thenandnow">{{cite book |title=Brisbane Then and Now |last=Gregory |first=Helen |year=2007 |publisher=Salamander Books |location=Wingfield, South Australia |isbn=978-1-74173-011-1 |page=60 }}</ref> The urban area, including the central business district, are partially elevated by spurs of the [[Taylor Range (Queensland)|Herbert Taylor Range]], such as the summit of [[Mount Coot-tha, Queensland|Mount Coot-tha]], reaching up to {{convert|300|m|ft|-1}} and the smaller [[Enoggera Hill]]. Other prominent rises in Brisbane are [[Mount Gravatt, Queensland|Mount Gravatt]] and nearby [[Toohey Mountain]]. [[Mount Petrie]] at {{convert|170|m|ft|-1|abbr=on}} and the lower rises of [[Highgate Hill, Queensland|Highgate Hill]], [[Mount Ommaney]], [[Stephens Mountain, Queensland|Stephens Mountain]] and [[Whites Hill, Queensland|Whites Hill]] are dotted across the city. Also, on the west, are the higher Mount Glorious, (680 m), and Mount Nebo (550 m). |

|||

The city is on a low-lying [[floodplain]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/10/12/3036241.htm?site=Brisbane |title=Flood-proof road destroyed in deluge |work=ABC News |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140706084641/http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/10/12/3036241.htm?site=Brisbane |archivedate=6 July 2014 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Many suburban creeks criss-cross the city, increasing the risk of [[flooding]]. The city has suffered three major floods since colonisation, in [[1893 Brisbane flood|February 1893]], [[1974 Brisbane Flood|January 1974]], and [[2010–2011 Queensland floods|January 2011]]. The [[1974 Brisbane Flood]] occurred partly as a result of "[[Cyclone Wanda]]". Heavy rain had fallen continuously for three weeks before the [[Australia Day]] weekend flood (26–27 January 1974).<ref>{{cite book |title=Habitat: Human Settlements in an Urban Age |last=Gunn |first=Angus M. |year=1978 |publisher=Pergamon Press |page=178 |isbn=0-08-021487-8}}</ref> The flood damaged many parts of the city, especially the suburbs of [[Oxley, Queensland|Oxley]], [[Bulimba, Queensland|Bulimba]], [[Rocklea, Queensland|Rocklea]], [[Coorparoo, Queensland|Coorparoo]], [[Toowong, Queensland|Toowong]] and [[New Farm, Queensland|New Farm]]. The [[City Botanic Gardens]] were inundated, leading to a new colony of [[mangrove]]s forming in the City Reach of the Brisbane River.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.coastal.crc.org.au/pdf/HistoricalCoastlines/App_3_Timeline_BrisbaneRiver.pdf |title=Timeline for Brisbane River |publisher=Coastal CRC |format=PDF |access-date=4 January 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080216092001/http://www.coastal.crc.org.au/pdf/HistoricalCoastlines/App_3_Timeline_BrisbaneRiver.pdf |archivedate=16 February 2008 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

===Urban structure=== |

|||

{{Multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = horizontal |

|||

| header = |

|||

| header_align = |

|||

| header_background = |

|||

| footer = The steel [[cantilever bridge|cantilever]] [[Story Bridge]] was constructed in 1940 to connect [[Fortitude Valley]] to [[Kangaroo Point, Queensland|Kangaroo Point]]. In the image on the right, the bridge is illuminated in blue for [[ovarian cancer]] awareness. |

|||

| footer_align = left/right/center |

|||

| footer_background = |

|||

| width = |

|||

| image1 = BNE-StoryBridge-fromCityCat.jpg |

|||

| width1 = 170 |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| image2 = Story Bridge, Brisbane (14964432888).jpg |

|||

| width2 = 230 |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

}} |

|||

The Brisbane central business district (CBD) lies in a curve of the Brisbane river. The CBD covers {{convert|2.2|km2|sqmi|1|abbr=on}} and is walkable. Central streets are named after members of the [[House of Hanover]]. [[Queen Street, Brisbane|Queen Street]] is Brisbane's traditional [[main street]]. Streets named after female members ([[Adelaide Street, Brisbane|Adelaide]], [[Alice Street, Brisbane|Alice]], [[Ann Street, Brisbane|Ann]], [[Charlotte Street, Brisbane|Charlotte]], [[Elizabeth Street, Brisbane|Elizabeth]], [[Margaret Street, Brisbane|Margaret]], [[Mary Street, Brisbane|Mary]]) run parallel to [[Queen Street, Brisbane|Queen Street]] and [[Queen Street Mall, Brisbane|Queen Street Mall]] (named in honour of [[Queen Victoria]]) and at right angles to streets named after male members ([[Albert Street, Brisbane|Albert]], [[Edward Street, Brisbane|Edward]], [[George Street, Brisbane|George]], [[William Street, Brisbane|William]]). The city has retained some heritage buildings dating back to the 1820s. [[The Old Windmill, Brisbane|The Old Windmill]], in [[Wickham Park, Brisbane|Wickham Park]], built by convict labour in 1824,<ref name=oldwindmill>Campbell Newman, ''"bmag"'', 3 November 2009</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/oh/treasures/timewalks/bris/1870/windmill |title=TimeWalks Brisbane — Windmill |publisher=[[Queensland Government]] |date=24 March 2008 |accessdate=10 April 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071219042223/http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/oh/treasures/timewalks/bris/1870/windmill |archivedate=19 December 2007 }}</ref> is the oldest surviving building in Brisbane. The Old Windmill was originally used for the grinding of grain and a punishment for the convicts who manually operated the grinding mill. The Old Windmill tower's other significant claim to fame, largely ignored, is that the first television signals in the southern hemisphere were transmitted from it by experimenters in April 1934—long before TV commenced in most places. These experimental TV broadcasts continued until World War II.<ref name="oldwindmill"/> The Old Commissariat Store, on William Street, built by convict labour in 1828, was originally used partly as a grainhouse, has also been a hostel for immigrants and used for the storage of records. Built with [[Brisbane tuff]] from the nearby [[Kangaroo Point Cliffs]] and sandstone from a quarry near today's Albion Park Racecourse, it is now the home of the Royal Historical Society of Brisbane. It contains a museum and can also be hired for small functions.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Origin of Australia's Capital Cities |last=Statham-Drew |first=Pamela|page=257 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-40832-5 |year=1990 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Australia |last=Pike |first=Jeffrey |publisher=Insight |isbn=978-981-234-799-2 |year=2002 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.queenslandhistory.org.au/comm.html |title=The Commissariat Stores |accessdate=24 February 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080523150756/http://www.queenslandhistory.org.au/comm.html |archivedate=23 May 2008 }}</ref> Greater Brisbane had a density of 148 people per square kilometre in 2016.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/3GBRI?opendocument|title=2016 Census Community Profile – Greater Brisbane (3GBRI – GCCSA)|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170714080526/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/3GBRI?opendocument|archivedate=14 July 2017|df=dmy-all}}; {{cite web |url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/CensusOutput/copsub2016.NSF/All%20docs%20by%20catNo/2016~Community%20Profile~3GBRI/$File/GCP_3GBRI.zip?OpenElement |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2 July 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170714081035/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/CensusOutput/copsub2016.NSF/All%20docs%20by%20catNo/2016~Community%20Profile~3GBRI/$File/GCP_3GBRI.zip?OpenElement |archivedate=14 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}, ZIPed Excel spreadsheet. Cover & G01a</ref> Like most Australian and North American cities, Brisbane has a sprawling metropolitan area which takes in excess of one hour to traverse either north to south or east to west by car without traffic. |

|||

Pre-1950 housing was often built in a distinctive architectural style known as a [[Queenslander (architecture)|Queenslander]], featuring timber construction with large [[verandah]]s and high ceilings. The relatively low cost of timber in South-East Queensland meant that until recently most residences were constructed of timber, rather than brick or stone. Many of these houses are elevated on stumps (also called "stilts"), that were originally timber, but are now frequently replaced by steel or concrete. Queenslander houses are considered iconic to Brisbane and are typically sold at a significant premium to equivalent modern houses. Early legislation decreed a minimum size for residential blocks causing few [[terrace house]]s being constructed in Brisbane. The high density housing that historically existed came in the form of miniature [[Queenslander (architecture)|Queenslander]]-style houses which resemble the much larger traditional styles but are sometimes only one quarter the size. These houses are common in the inner city suburbs. At the 2016 census, 76.4% of residents lived in [[Single-family detached home|separate houses]], 12.6% lived in [[apartment]]s and 10% lived in [[townhouse]]s, [[terrace house]]s or [[semi-detached]] houses.<ref name="QS 3GBRI 2016">{{cite web |url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/3GBRI?opendocument |title=2016 Census QuickStats |publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |access-date=4 August 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170714081145/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/3GBRI?opendocument |archivedate=14 July 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Brisbane is home to several of [[List of tallest buildings in Australia|Australia's tallest buildings]]. [[List of tallest buildings in Brisbane|Brisbane's tallest building]] is [[1 William Street, Brisbane|1 William Street]] at 260 metres, to be overtaken by the 270 metre [[Brisbane Skytower]] which is currently under construction.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://buildingdb.ctbuh.org/?do=create>|title=CTBUH Tall Building Database – The Skyscraper Center|author=CTBUH|work=Skyscrapercenter}}</ref> |

|||

<div style="overflow:auto;">{{overlay |

|||

|image = BrisbaneRiver02 gobeirne-edit1.jpg |

|||

|width = 900 |

|||

|height = 675 |

|||

|columns = 2 |

|||

|overlay1 = [[Walter Taylor Bridge]] (road) (left), [[Albert Bridge, Brisbane|Albert Bridge]] (rail) (centre), unnamed bridge (rail) (right), [[Jack Pesch Bridge]] (far right) |

|||

|overlay1tip = Walter Taylor, Albert, unnamed, Jack Pesch bridges |

|||

|overlay1top = 50 |

|||

|overlay1left = 780 |

|||

|overlay2 = Eleanor Schonell Bridge (Green Bridge) (pedestrians, pedal cycles, buses) |

|||

|overlay2top = 250 |

|||

|overlay2left = 445 |

|||

|overlay2link = Eleanor Schonell Bridge |

|||

|overlay3 = Merivale Bridge (rail) |

|||

|overlay3tip = Merivale Bridge |

|||

|overlay3top = 375 |

|||

|overlay3left = 720 |

|||

|overlay3link = Merivale Bridge |

|||

|overlay4 = William Jolly Bridge (road) |

|||

|overlay4tip = William Jolly Bridge |

|||

|overlay4top = 390 |

|||

|overlay4left = 703 |

|||

|overlay4link = William Jolly Bridge |

|||

|overlay5 = Victoria Bridge |

|||

|overlay5top = 400 |

|||

|overlay5left = 650 |

|||

|overlay5link = Victoria Bridge, Brisbane |

|||

|overlay6 = Captain Cook Bridge |

|||

|overlay6top = 390 |

|||

|overlay6left = 480 |

|||

|overlay6link = Captain Cook Bridge, Brisbane |

|||

|overlay7 = Story Bridge |

|||

|overlay7top = 545 |

|||

|overlay7left = 550 |

|||

|overlay7link = Story Bridge |

|||

|overlay8 = Pacific Motorway |

|||

|overlay8top = 313 |

|||

|overlay8left = 240 |

|||

|overlay8link = Pacific Motorway (Brisbane–Brunswick Heads) |

|||

|overlay9 = Suncorp Stadium (Lang Park) (Rugby league ground) |

|||

|overlay9tip = Suncorp Stadium |

|||

|overlay9top = 390 |

|||

|overlay9left = 825 |

|||

|overlay9link = Lang Park |

|||

|overlay10colour = blue |

|||

|overlay10 = Norman Creek (Anglican Church Grammar School) |

|||

|overlay10top = 505 |

|||

|overlay10left = 205 |

|||

|overlay10link = Norman Creek (Queensland) |

|||

|overlay11 = Oxley Creek |

|||

|overlay11top = 19 |

|||

|overlay11left = 480 |

|||

|overlay11link = Oxley Creek |

|||

|overlay12 = Brisbane River |

|||

|overlay12top1 = 100 |

|||

|overlay12left1 = 489 |

|||

|overlay12top2 = 575 |

|||

|overlay12left2 = 280 |

|||

|overlay12link = Brisbane River |

|||

|overlay13colour = red |

|||

|overlay13 = Indooroopilly Shoppingtown |

|||

|overlay13top = 65 |

|||

|overlay13left = 860 |

|||

|overlay13link = Indooroopilly Shopping Centre |

|||

|overlay14 = "The Gabba" (Brisbane Cricket Ground) |

|||

|overlay14tip = The Gabba |

|||

|overlay14top = 380 |

|||

|overlay14left = 350 |

|||

|overlay14link = The Gabba |

|||

|overlay15colour = green |

|||

|overlay15 = South Bank arts and recreation precinct |

|||

|overlay15tip = South Bank |

|||

|overlay15top = 375 |

|||

|overlay15left = 580 |

|||

|overlay15link = South Bank Parklands |

|||

|overlay16color = red |

|||

|overlay16 = Central business district |

|||

|overlay16top = 450 |

|||

|overlay16left = 590 |

|||

|overlay16link = Brisbane central business district |

|||

|overlay17 = [[University of Queensland]] (UQ) St Lucia Campus |

|||

|overlat17tip = University of Queensland |

|||

|overlay17top = 245 |

|||

|overlay17left = 505 |

|||

|overlay18color = green |

|||

|overlay18 = City Botanic Gardens |

|||

|overlay18top = 425 |

|||

|overlay18left = 520 |

|||

|overlay18link = City Botanic Gardens |

|||

|overlay19colour = red |

|||

|overlay19 = [[Queensland University of Technology]] (QUT) Gardens Point Campus |

|||

|overlay19tip = Queensland University of Technology |

|||

|overlay19top = 390 |

|||

|overlay19left = 515 |

|||

|overlay20 = Goodwill Bridge (pedestrians and pedal cycles) |

|||

|overlay20top = 375 |

|||

|overlay20left = 522 |

|||

|overlay20tip = Goodwill Bridge |

|||

|overlay20link = Goodwill Bridge |

|||

|overlay21 = The [[Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital]] |

|||

|overlay21top = 600 |

|||

|overlay21left = 750 |

|||

|overlay22 = Mater Private Hospital |

|||

|overlay22top = 325 |

|||

|overlay22left = 460 |

|||

|overlay22link = Mater Health Services |

|||

|overlay23 = Roma Street Rail Station |

|||

|overlay23top = 420 |

|||

|overlay23left = 725 |

|||

|overlay23link = Roma Street railway station |

|||

|overlay24colour = green |

|||

|overlay24 = Roma Street Parkland |

|||

|overlay24top = 455 |

|||

|overlay24left = 740 |

|||

|overlay24link = Roma Street Parkland |

|||

|overlay25 = New Farm Park and Powerhouse |

|||

|overlay25top = 575 |

|||

|overlay25left = 325 |

|||

|overlay25link = New Farm Park |

|||

|overlay26 = Victoria Park Golf Course |

|||

|overlay26top = 520 |

|||

|overlay26left = 810 |

|||

|overlay27colour = red |

|||

|overlay27 = Brisbane Exhibition Ground |

|||

|overlay27top = 625 |

|||

|overlay27left = 700 |

|||

|overlay27link = Brisbane Exhibition Ground |

|||

|overlay28 = [[Brisbane River#Brisbane Riverwalk|Brisbane Riverwalk]] (Destroyed in 2011 floods) |

|||

|overlay28top = 525 |

|||

|overlay28left = 455 |

|||

|overlay29 = Inner City Bypass (rail) (left) (road) (right) |

|||

|overlay29tip = Inner City Bypass |

|||

|overlay29top = 525 |

|||

|overlay29left = 760 |

|||

|overlay29link = Inner City Bypass, Brisbane |

|||

|overlay30colour = green |

|||

|overlay30 = [[Indooroopilly, Queensland|Indooroopilly]] Golf Course |

|||

|overlay30top = 85 |

|||

|overlay30left = 455 |

|||

}}</div> |

|||

===Climate=== |

|||

[[File:Brisbane storm.jpg|thumb|left|A spring storm with lightning over the central business district]] |

|||

Brisbane has a [[humid subtropical climate]] ([[Köppen climate classification]]: ''Cfa'')<ref>{{cite web|title=Climate: Brisbane – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table|url=http://en.climate-data.org/location/6171/|publisher=Climate-Data.org|accessdate=28 August 2013|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131215043242/http://en.climate-data.org/location/6171/|archivedate=15 December 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> with hot, wet summers and dry moderately warm winters.<ref>{{cite book|last=Tapper|first=Andrew|last2=Tapper|first2=Nigel|title=The weather and climate of Australia and New Zealand|year=2006|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Melbourne, Australia|isbn=978-0-19-558466-0|edition=Second|editor=Gray, Kathleen|page=346|chapter=Sub-Synoptic-Scale Processes and Phenomena}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Linacre | first = Edward |author2=Geerts, Bart | title = Climates and Weather Explained | publisher=Routledge | location = London | year = 1997 | page = 379 | chapter = Southern Climates | url = https://books.google.com/?id=mkZa1KLHCAQC&lpg=PA379&pg=PA379#v=onepage&q= | isbn = 0-415-12519-7}}</ref>Brisbane experiences an annual mean minimum of {{convert|16.6|°C|°F|0}} and mean maximum of {{convert|26.6|°C|°F|0}}, making it Australia's second-hottest capital city after Darwin.<ref name="auto1">{{cite web|title=Climate statistics for Australian stations - Brisbane|url=http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_040913_All.shtml|publisher=Bureau of Meteorology|accessdate=12 February 2018|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170813072724/http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_040913_All.shtml|archivedate=13 August 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Seasonality is not pronounced, and average maximum temperatures of above {{convert|26|°C|°F|0}} persist from September through to April. |

|||

Due to its proximity to the Coral Sea and a warm ocean current, Brisbane's overall temperature variability is somewhat less than most Australian capitals. Summers are long, hot, and wet, but temperatures only occasionally reach {{convert|35|°C|°F|0}} or more. Eighty percent of summer days record a maximum temperature of {{convert|27|to|33|°C|°F|0}}. Winters are short and warm, with average maximums of about {{convert|22|°C|°F|0}}; maximum temperatures below {{convert|20|°C|°F|0}} are rare. Brisbane has never recorded a sub-zero minimum temperature (with one exception), and minimums are generally warm to mild year-round, averaging about {{convert|21|°C|°F|0}} in summer and {{convert|11|°C|°F|0}} in winter.<ref name="auto1"/> |

|||

From November to March, thunderstorms are common over Brisbane, with the more severe events accompanied by large damaging hail stones, torrential rain and destructive winds. On an annual basis, Brisbane averages 124 clear days.<ref>{{BoM Aust stats|site_ref=cw_040223_All|site_name=Brisbane Aero|accessdate=20 November 2014}}</ref> Dewpoints in the summer average at around {{convert|20|°C|°F|0}}; the [[apparent temperature]] exceeds {{convert|30|°C|°F|0}} on almost all summer days.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{BoM Aust stats|site_ref=cw_040913_All|site_name=Brisbane|accessdate=16 June 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The city's highest recorded temperature was {{convert|43.2|°C|°F|1}} on [[Australia Day]] 1940 at the Brisbane Regional Office,<ref name="ReferenceB">{{BoM Aust stats|site_ref=cw_040214_All|site_name=Brisbane Regional Office|accessdate=15 January 2017}}</ref> with the highest temperature at the current station being {{convert|41.7|°C|°F|1}} on 22 February 2004;<ref>http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/cdio/weatherData/av?p_nccObsCode=122&p_display_type=dailyDataFile&p_startYear=&p_c=&p_stn_num=040913</ref> but temperatures above {{convert|38|°C|°F|0}} are uncommon. On 19 July 2007, Brisbane's temperature fell below the freezing point for the first time since records began, registering {{convert|-0.1|°C|°F|1}} at the airport station.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/articles/2007/07/19/1184559902397.html|title=Coldest day on record for Brisbane|work=The Brisbane Times|author=Daniel Sankey and Tony Moore|date=19 July 2007|accessdate=5 January 2008|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012140228/http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/articles/2007/07/19/1184559902397.html|archivedate=12 October 2007|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The city station has never dropped below {{convert|2|°C|°F|0}},<ref name="ReferenceA"/> with the average coldest night during winter being around {{convert|6|°C|°F|0}}, however locations directly west of Brisbane such as [[Ipswich, Queensland|Ipswich]] have dropped as low as {{convert|-5|°C|°F|0}} with heavy ground frost.<ref>{{BoM Aust stats|site_ref=cw_040004_All|site_name=AMBERLEY AMO|accessdate=9 February 2014|date=February 2014}}</ref> In 2009, the current Brisbane weather station recorded its hottest winter day at {{convert|35.4|°C|°F|1}} on 24 August;<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/hot-august-day-as-records-fall-20090824-evxp.html|title=Hot August day as Records Fall|work=The Brisbane Times|author=Unknown|date=24 August 2009|accessdate=31 August 2010|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090827141847/http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/hot-august-day-as-records-fall-20090824-evxp.html|archivedate=27 August 2009|df=dmy-all}}</ref> however, on the penultimate day of winter, the Brisbane Regional Office station recorded a temperature of {{convert|38.3|°C|°F|1}} on 22 September 1943.<ref name="bom.gov.au">http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/cdio/weatherData/av?p_nccObsCode=122&p_display_type=dailyDataFile&p_startYear=1986&p_c=-323581085&p_stn_num=040214</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.timeanddate.com/sun/australia/brisbane?month=9&year=1943 |title=Archived copy |accessdate=20 October 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20171020190842/https://www.timeanddate.com/sun/australia/brisbane?month=9&year=1943 |archivedate=20 October 2017 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> The average July day however is around {{convert|22|°C|°F|0}} with sunny skies and low humidity, occasionally as high as {{convert|27|°C|°F|0}}, whilst maximum temperatures below {{convert|18|°C|°F|0}} are uncommon and usually associated with brief periods of cloud and winter rain.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> The highest minimum temperature ever recorded in Brisbane was {{convert|28.0|°C|°F|1}} on 29 January 1940 and again on 21 January 2017, whilst the lowest maximum temperature was {{convert|10.2|°C|°F|1}} on 12 August 1954.<ref name="ReferenceB"/> |

|||

Brisbane's wettest day occurred on 21 January 1887, when {{convert|465|mm|in}} of rain fell on the city, the highest maximum daily rainfall of Australia's capital cities. The wettest month on record was February 1893, when {{convert|1025.9|mm|in}} of rain fell, although in the last 30 years the record monthly rainfall has been a much lower {{convert|479.8|mm|in}} from December 2010. Very occasionally a whole month will pass with no recorded rainfall, the last time this happened was August 1991.<ref name="ReferenceB"/> |

|||

From 2001 until 2010, Brisbane and surrounding temperate areas had been experiencing the most severe drought in over a century, with dam levels dropping to 16.9% of their capacity on 10 August 2007. Residents were mandated by local laws to observe [[Water restrictions in Australia#Stages|level 6]] water restrictions on gardening and other outdoor water usage. Per capita water usage was below 140 litres per day, giving Brisbane one of the lowest per capita usages of water of any developed city in the world.<ref>{{cite web | title=Brisbane residents best water savers in world: Newman | work=ABC News | url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/08/27/2016895.htm | accessdate=19 March 2008 | deadurl=no | archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080520062353/http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/08/27/2016895.htm | archivedate=20 May 2008 | df=dmy-all }}</ref> On 9 January 2011, an upper low crossed north of Brisbane and dropped rainfall on an already saturated southeast coast of Queensland, resulting in severe flooding and damage in Brisbane and the surrounding area;<ref>{{cite web |title = Raging floods bear down on Brisbane |url = http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-01-11/raging-floods-bear-down-on-brisbane/1901406 |deadurl = no |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20160205050909/http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-01-11/raging-floods-bear-down-on-brisbane/1901406 |archivedate = 5 February 2016 |df = dmy-all }}</ref> the same storm season also caused the water storage to climb to over 98% of maximum capacity and broke the drought.<ref>{{cite web|title=SEQWater latest dam levels |url=http://seqwater.com.au/public/dam-levels |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121014150943/http://www.seqwater.com.au/public/dam-levels |archivedate=14 October 2012 }}</ref> Water restrictions have been replaced with water conservation measures that aim at a target of 200 litres per day/per person, but consumption is rarely over 160 litres. In November 2011, Brisbane saw 22 days with no recorded rainfall, which was the driest start to a November since 1919.<ref name="CourierMail">{{cite news|url=http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/time-to-chill-out-as-scorchers-near-end/story-e6freoof-1226201906261|title=November dry spell in Brisbane set to end as rain forecast|work=The Courier-Mail|accessdate=22 November 2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120212112321/http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/time-to-chill-out-as-scorchers-near-end/story-e6freoof-1226201906261|archivedate=12 February 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

Brisbane also lies in the Tropical Cyclone risk area, although cyclones are rare. The last to affect Brisbane was Severe Tropical [[Cyclone Debbie]] in March 2017. The city is susceptible to severe thunderstorms in the spring and summer months; on 16 November 2008 a severe storm caused tremendous damage in the outer suburbs, most notably [[The Gap, Queensland|The Gap]]. Roofs were torn off houses and hundreds of trees were felled. More recently, on 27 November 2014, a very strong [[2014 Brisbane hailstorm|storm]] made a direct hit on the city centre.<ref name="ABCNEWS">{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-28/brisbane-storms-68000-residents-still-without-power/5924112|title=Brisbane storm: Tens of thousands of south-east Queensland residents still without power after 'worst storm in a decade'|accessdate=28 November 2014|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20141128075835/http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-28/brisbane-storms-68000-residents-still-without-power/5924112|archivedate=28 November 2014|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Described as 'the worst storm in a decade,' very large hail, to the size of cricket balls, smashed skyscraper windows while a flash flood tore through the CBD. Wind gusts of {{convert|141|km/h|abbr=on}} were recorded in some suburbs, many houses were severely damaged, cars were destroyed and planes were flipped at the [[Brisbane Airport|Brisbane]] and [[Archerfield Airport]]s.<ref name="ABCNEWS"/> [[Dust storm]]s in Brisbane are extremely rare; on 23 September 2009, however, a [[2009 Australian dust storm|severe dust storm]] blanketed Brisbane, as well as other parts of eastern Australia.<ref>{{cite news | last = Cubby | first = Ben | title = Global warning: Sydney dust storm just the beginning | newspaper = Brisbane Times | location = Brisbane | date = 23 September 2009 | url = http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/global-warning-sydney-dust-storm-just-the-beginning-20090923-g1fi.html | access-date = 25 September 2009 | deadurl = no | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20090924211821/http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/global-warning-sydney-dust-storm-just-the-beginning-20090923-g1fi.html | archivedate = 24 September 2009 | df = dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/09/23/2694096.htm |title=Brisbane on alert as dust storms sweep east |publisher=Abc.net.au |date=23 September 2009 |access-date=4 November 2012 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20101130154623/http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/09/23/2694096.htm |archivedate=30 November 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

The average annual temperature of the sea ranges from {{convert|21.0|C|F}} in July to {{convert|27.0|C|F}} in February.<ref name="weather2travel">{{cite web|url=http://www.weather2travel.com/climate-guides/australia/queensland/brisbane.php|title=Brisbane Climate Guide|accessdate=9 October 2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111005121104/http://www.weather2travel.com/climate-guides/australia/queensland/brisbane.php|archivedate=5 October 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

{{Weather box |

|||

| location = Brisbane (1999–2017) |

|||

| metric first = Yes |

|||

| single line = Yes |

|||

| Jan record high C = 40.0 |

|||

| Feb record high C = 41.7 |

|||

| Mar record high C = 37.9 |

|||

| Apr record high C = 33.7 |

|||

| May record high C = 30.7 |

|||

| Jun record high C = 29.0 |

|||

| Jul record high C = 28.2 |

|||

| Aug record high C = 35.4 |

|||

| Sep record high C = 37.0 |

|||

| Oct record high C = 38.7 |

|||

| Nov record high C = 38.9 |

|||

| Dec record high C = 40.0 |

|||

| year record high C = 41.7 |

|||

| Jan high C = 30.3 |

|||

| Feb high C = 30.0 |

|||

| Mar high C = 29.0 |

|||

| Apr high C = 27.4 |

|||

| May high C = 24.5 |

|||

| Jun high C = 21.9 |

|||

| Jul high C = 21.9 |

|||

| Aug high C = 23.2 |

|||

| Sep high C = 25.6 |

|||

| Oct high C = 27.1 |

|||

| Nov high C = 28.2 |

|||

| Dec high C = 29.4 |

|||

| year high C = 26.5 |

|||

| Jan low C = 21.5 |

|||

| Feb low C = 21.3 |

|||

| Mar low C = 20.0 |

|||

| Apr low C = 17.4 |

|||

| May low C = 13.7 |

|||

| Jun low C = 11.8 |

|||

| Jul low C = 10.2 |

|||

| Aug low C = 10.8 |

|||

| Sep low C = 13.8 |

|||

| Oct low C = 16.2 |

|||

| Nov low C = 18.8 |

|||

| Dec low C = 20.4 |

|||

| year low C = 16.3 |

|||

| Jan record low C = 17.0 |

|||

| Feb record low C = 16.5 |

|||

| Mar record low C = 12.2 |

|||

| Apr record low C = 10.0 |

|||

| May record low C = 5.0 |

|||

| Jun record low C = 5.0 |

|||

| Jul record low C = 2.6 |

|||

| Aug record low C = 4.1 |

|||

| Sep record low C = 7.0 |

|||

| Oct record low C = 8.8 |

|||

| Nov record low C = 10.8 |

|||

| Dec record low C = 14.0 |

|||

| year record low C = 2.6 |

|||

| rain colour = green |

|||

| Jan rain mm = 151.8 |

|||

| Feb rain mm = 142.5 |

|||

| Mar rain mm = 109.7 |

|||

| Apr rain mm = 67.4 |

|||

| May rain mm = 67.9 |

|||

| Jun rain mm = 68.4 |

|||

| Jul rain mm = 24.0 |

|||

| Aug rain mm = 40.6 |

|||

| Sep rain mm = 31.6 |

|||

| Oct rain mm = 69.0 |

|||

| Nov rain mm = 100.1 |

|||

| Dec rain mm = 131.0 |

|||

| year rain mm = 1021.6 |

|||

| Jan precipitation days = 12.2 |

|||

| Feb precipitation days = 13.3 |

|||

| Mar precipitation days = 14.2 |

|||

| Apr precipitation days = 11.7 |

|||

| May precipitation days = 9.5 |

|||

| Jun precipitation days = 9.7 |

|||

| Jul precipitation days = 7.3 |

|||

| Aug precipitation days = 6.0 |

|||

| Sep precipitation days = 7.8 |

|||

| Oct precipitation days = 8.7 |

|||

| Nov precipitation days = 11.3 |

|||

| Dec precipitation days = 13.3 |

|||

| year precipitation days = 125.0 |

|||

| humidity colour = green |

|||

| Jan afthumidity = 57 |

|||

| Feb afthumidity = 59 |

|||

| Mar afthumidity = 57 |

|||

| Apr afthumidity = 54 |

|||

| May afthumidity = 49 |

|||

| Jun afthumidity = 52 |

|||

| Jul afthumidity = 44 |

|||

| Aug afthumidity = 43 |

|||

| Sep afthumidity = 48 |

|||

| Oct afthumidity = 51 |

|||

| Nov afthumidity = 56 |

|||

| Dec afthumidity = 57 |

|||

| year humidity = 52 |

|||

|Jan sun = 263.5 |

|||

|Feb sun = 223.2 |

|||

|Mar sun = 232.5 |

|||

|Apr sun = 234.0 |

|||

|May sun = 235.6 |

|||

|Jun sun = 198.0 |

|||

|Jul sun = 238.7 |

|||

|Aug sun = 266.6 |

|||

|Sep sun = 270.0 |

|||

|Oct sun = 275.9 |

|||

|Nov sun = 270.0 |

|||

|Dec sun = 260.4 |

|||

|year sun = 2968.4 |

|||

| source = [[Bureau of Meteorology]].<ref name="ReferenceA"/> |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Weather box |

|||

| location = Brisbane Regional Office (1887–1986) |

|||

| metric first = Yes |

|||

| single line = Yes |

|||

| Jan record high C = 43.2 |

|||

| Feb record high C = 40.9 |

|||

| Mar record high C = 38.8 |

|||

| Apr record high C = 36.1 |

|||

| May record high C = 32.4 |

|||

| Jun record high C = 31.6 |

|||

| Jul record high C = 29.1 |

|||

| Aug record high C = 32.8 |

|||

| Sep record high C = 38.3 |

|||

| Oct record high C = 40.7 |

|||

| Nov record high C = 41.2 |

|||

| Dec record high C = 41.2 |

|||

| year record high C = 43.2 |

|||

| Jan high C = 29.4 |

|||

| Feb high C = 29.0 |

|||

| Mar high C = 28.0 |

|||

| Apr high C = 26.1 |

|||

| May high C = 23.2 |

|||

| Jun high C = 20.9 |

|||

| Jul high C = 20.4 |

|||

| Aug high C = 21.8 |

|||

| Sep high C = 24.0 |

|||

| Oct high C = 26.1 |

|||

| Nov high C = 27.8 |

|||

| Dec high C = 29.1 |

|||

| year high C = 25.5 |

|||

| Jan low C = 20.7 |

|||

| Feb low C = 20.6 |

|||

| Mar low C = 19.4 |

|||

| Apr low C = 16.6 |

|||

| May low C = 13.3 |

|||

| Jun low C = 10.9 |

|||

| Jul low C = 9.5 |

|||

| Aug low C = 10.3 |

|||

| Sep low C = 12.9 |

|||

| Oct low C = 15.8 |

|||

| Nov low C = 18.1 |

|||

| Dec low C = 19.8 |

|||

| year low C = 15.7 |

|||

| Jan record low C = 14.9 |

|||

| Feb record low C = 14.7 |

|||

| Mar record low C = 11.3 |

|||

| Apr record low C = 6.9 |

|||

| May record low C = 4.8 |

|||

| Jun record low C = 2.4 |

|||

| Jul record low C = 2.3 |

|||

| Aug record low C = 2.7 |

|||

| Sep record low C = 4.8 |

|||

| Oct record low C = 6.3 |

|||

| Nov record low C = 9.2 |

|||

| Dec record low C = 13.5 |

|||

| year record low C = 2.3 |

|||

| source = <ref name="bom.gov.au"/><ref>http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/cdio/weatherData/av?p_nccObsCode=123&p_display_type=dailyDataFile&p_startYear=1986&p_c=-323581281&p_stn_num=040214</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

==Governance== |

|||

{{Main article|City of Brisbane|Government of Queensland}} |

|||

{{Multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = horizontal |

|||

| header = |

|||

| header_align = left/right/center |

|||

| header_background = |

|||

| footer =[[Brisbane City Hall]] home to the [[Museum of Brisbane]], [[Brisbane City Council]] offices and [[Parliament House, Brisbane|Parliament House]], the home of Queensland's state legislature |

|||

| footer_align = left/right/center |

|||

| footer_background = |

|||

| width = |

|||

| image1 = Brisbane Town Hall.jpg |

|||

| width1 = 150 |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| image2 = Parliament House, Brisbane 03-cropped.jpg |

|||

| width2 = 235 |

|||

| caption2 = }} |

|||

Unlike other Australian capital cities, a large portion of the greater metropolitan area, or Greater Capital City Statistical Area (GCCSA) of Brisbane is controlled by a single [[Local government in Australia|local government area]], the [[City of Brisbane]]. Since the creation of the City of Brisbane in 1925 the urban areas of Brisbane have expanded considerably past the council boundaries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.netcat.com.au/NETCAT/STANDARD/PC_4.html |title=Brisbane City Council |publisher=NetCat |accessdate=28 December 2007 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070829023716/http://www.netcat.com.au/NETCAT/STANDARD/PC_4.html |archivedate=29 August 2007 }}</ref> The City of Brisbane local government area is by far the largest local government area (in terms of population and budget) in Australia, serving more than 40% of the GCCSA's population. It was formed by the merger of twenty smaller LGAs in 1925, and covers an area of {{Convert|1367|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on}}. |

|||

The remainder of the metropolitan area falls into the LGAs of [[Logan City]] to the south, [[Moreton Bay Region]] in the northern suburbs, the [[City of Ipswich]] to the south west, [[Redland City]] to the south east on the bayside, with a small strip to the far west in the [[Scenic Rim Region]]. |

|||

==Economy== |

|||

[[File:Bne2017.png|thumb|left|upright=1.25|Aerial view of Brisbane CBD]] |

|||

White-collar industries include information technology, [[financial services]], higher education and [[public sector]] administration generally concentrated in and around the central business district and recently established office areas in the inner suburbs. Blue-collar industries, including petroleum refining, [[stevedoring]], paper milling, [[metalworking]] and [[Queensland Rail|QR]] railway workshops, tend to be located on the lower reaches of the Brisbane River and in new industrial zones on the urban fringe. Tourism is an important part of the Brisbane economy, both in its own right and as a gateway to other areas of Queensland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brisbanemarketing.com.au/%5Cnews-and-events%5Cnews-article.aspx?id=171 |title=Brisbane's business visitors drive $412 million domestic tourism increase |publisher=Brisbane Marketing |date=14 December 2007 |author=Department of Tourism, Regional Development and Industry |accessdate=29 December 2007 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080509135019/http://www.brisbanemarketing.com.au/news-and-events/news-Article.aspx?id=171 |archivedate=9 May 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:ABS-6291.0.55.001-LabourForceAustraliaDetailed ElectronicDelivery-LabourForceStatusByLabourMarketRegionSex-GreaterBrisbane-UnemploymentRate-Persons-A84600151F.svg|thumb|right|upright=1.35|Unemployment rate in the Greater Brisbane labour market region since 1998<ref>{{cite web|title=Greater Brisbane; Unemployment rate; Persons; series A84600151F|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.001|work=6291.0.55.001 Labour Force, Australia, Detailed – Electronic Delivery|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160619104046/http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.001|archivedate=19 June 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref>]] |

|||

Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Queensland State Government has been developing technology and science industries in Queensland as a whole, and Brisbane in particular, as part of its "Smart State" initiative.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smartstate.qld.gov.au/strategy/index.shtm#what|title=What is the Smart State|publisher=[[Queensland Government]]|accessdate=29 December 2007|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071229071238/http://www.smartstate.qld.gov.au/strategy/index.shtm#what|archivedate=29 December 2007|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The government has invested in several biotechnology and research facilities at several universities in Brisbane. The [[Institute for Molecular Bioscience]] at the [[University of Queensland]] (UQ) Saint Lucia Campus is a large [[CSIRO]] and Queensland state government initiative for research and innovation that is currently being emulated at the [[Queensland University of Technology]] (QUT) Campus at Kelvin Grove with the establishment of the [[Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation]] (IHBI).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,22867846-27197,00.html|title=Brain power drives Smart State|work=[[The Courier-Mail]]|author=[[Peter Beattie]]|date=4 December 2007|accessdate=29 December 2007|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://archive.is/20120702220724/http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/opinion/brain-power-drives-smart-state/story-e6frerdf-1111115028459|archivedate=2 July 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:National Australia Bank, Brisbane.jpg|thumb|right|The [[National Australia Bank Building]] located on [[Queen Street, Brisbane|Queen Street]]]] |

|||

Brisbane is one of the major business hubs in Australia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etravelblackboard.com/index.asp?id=73027&nav=13|title=Brisbane business visitor numbers skyrocket|date=3 January 2008|work=Brisbane Marketing Convention Bureau|publisher=e-Travel Blackboard|accessdate=13 January 2008|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110120134851/http://www.etravelblackboard.com/index.asp?id=73027&nav=13|archivedate=20 January 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Most major Australian companies, as well as numerous international companies, have contact offices in Brisbane, while numerous [[electronics]] businesses have distribution hubs in and around the city. [[DHL Global Forwarding|DHL Global]]'s Oceanic distribution warehouse is located in Brisbane, as is [[Asia Pacific]] Aerospace's headquarters. Home grown major companies include [[Suncorp-Metway Limited]], [[Flight Centre]], [[Sunsuper]], [[Orrcon]], [[Credit Union Australia]], [[Boeing Australia]], [[Donut King]], [[Wotif.com]], [[WebCentral]], [[PIPE Networks]], [[Krome Studios]], [[Mincom Limited]], [[TechnologyOne]], [[Thiess Pty Ltd]] and [[Virgin Australia]]. Brisbane has the fourth highest [[Median household income in Australia and New Zealand|median household income]] of the Australian capital cities at AUD 57,772.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/PopularAreas?ReadForm&prenavtabname=Popular%20Locations&type=popular&&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&textversion=false&collection=Census&period=2006&producttype=QuickStats&method=&productlabel=&breadcrumb=PL&topic=& |title=2006 Census QuickStats by Location |accessdate=19 July 2008 |publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080727145511/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/PopularAreas?ReadForm&prenavtabname=Popular%20Locations&type=popular&&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&textversion=false&collection=Census&period=2006&producttype=QuickStats&method=&productlabel=&breadcrumb=PL&topic=& |archivedate=27 July 2008 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

===Port of Brisbane=== |

|||