Yemen: Difference between revisions

SharabSalam (talk | contribs) m Undid revision 918619829 by 188.218.81.97 (talk) |

No edit summary Tag: missing file added |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{other uses}} |

{{other uses}} |

||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2015}} |

|||

{{Coord|15|N|48|E|display=title}} |

|||

{{short description|Republic in Western Asia}} |

{{short description|Republic in Western Asia}} |

||

{{Infobox country |

{{Infobox country |

||

| conventional_long_name = Republic of |

| conventional_long_name = Republic of Semen |

||

| common_name = |

| common_name = Semen |

||

| native_name = {{native name|ar|ٱلْجُمْهُورِيَّة ٱلْيَمَنِيَّة|italics=off}}<br>{{small|{{nobold|''al-Jumhūrīyah al-Yamanīyah''}}}} |

| native_name = {{native name|ar|ٱلْجُمْهُورِيَّة ٱلْيَمَنِيَّة|italics=off}}<br>{{small|{{nobold|''al-Jumhūrīyah al-Yamanīyah''}}}} |

||

| image_flag = Flag of |

| image_flag = Flag of Semen.svg |

||

| image_coat = |

| image_coat = Semen Coat of Arms.svg |

||

| coa_size = 110px |

| coa_size = 110px |

||

| symbol_type = Emblem |

| symbol_type = Emblem |

||

| national_motto = {{native name|ar|الله، ٱلْوَطَن، ٱلثَوْرَة، ٱلْوَحْدَة|Allāh|italics=off}}<br />{{transl|ar|Allāh, al-Waṭan, ath-Thawrah, al-Waḥdah}}<br />“God, Country, Revolution, Unity” |

| national_motto = {{native name|ar|الله، ٱلْوَطَن، ٱلثَوْرَة، ٱلْوَحْدَة|Allāh|italics=off}}<br />{{transl|ar|Allāh, al-Waṭan, ath-Thawrah, al-Waḥdah}}<br />“God, Country, Revolution, Unity” |

||

| national_anthem = [[National anthem of |

| national_anthem = [[National anthem of Semen|''United Republic'']] <br />({{lang-ar|الجمهورية المتحدة|al-Jumhūrīyah al-Muttaḥidah}})<br />{{lower|0.2em|[[File:United States Navy Band - United Republic.ogg|centre]]}} |

||

| image_map = |

| image_map = Semen on the globe (Semen centered).svg |

||

| map_caption = {{map caption |location_color= red}} |

| map_caption = {{map caption |location_color= red}} |

||

| image_map2 = |

| image_map2 = Semen - Location Map (2013) - YEM - UNOCHA.svg |

||

| capital = [[Sana'a]] (''[[Houthi takeover in |

| capital = [[Sana'a]] (''[[Houthi takeover in Semen|de jure]]'')<br />[[Aden]] (seat of government) |

||

| largest_city = [[Sana'a]] |

| largest_city = [[Sana'a]] |

||

| official_languages = [[Modern Standard Arabic|Arabic]] |

| official_languages = [[Modern Standard Arabic|Arabic]] |

||

| ethnic_groups = <!--The following is sourced (see ethnic_groups_year above), so please do not change it without also replacing that source:-->{{ublist|[[Arab]] 92.8%|[[Somalis]] 3.7%|[[Afro-Arab]] 1.1%|[[Indo-Pakistani]] 1%|Other 1.4%}} |

| ethnic_groups = <!--The following is sourced (see ethnic_groups_year above), so please do not change it without also replacing that source:-->{{ublist|[[Arab]] 92.8%|[[Somalis]] 3.7%|[[Afro-Arab]] 1.1%|[[Indo-Pakistani]] 1%|Other 1.4%}} |

||

| demonym = [[Demographics of |

| demonym = [[Demographics of Semen|Semeni, Semenite, Semenese]] |

||

| government_type = |

| government_type = |

||

* [[Unitary state|Unitary]] [[presidential system|presidential]] [[constitution]]al [[republic]] (de jure) |

* [[Unitary state|Unitary]] [[presidential system|presidential]] [[constitution]]al [[republic]] (de jure) |

||

* [[Unitary state|Unitary]] [[provisional government]] (de facto) |

* [[Unitary state|Unitary]] [[provisional government]] (de facto) |

||

| leader_title1 = [[President of |

| leader_title1 = [[President of Semen|President]] |

||

| leader_name1 = [[Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi]] |

| leader_name1 = [[Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi]] |

||

| leader_title2 = [[Vice President of |

| leader_title2 = [[Vice President of Semen|Vice President]] |

||

| leader_name2 = [[Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar]] |

| leader_name2 = [[Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar]] |

||

| leader_title3 = [[Prime Minister of |

| leader_title3 = [[Prime Minister of Semen|Prime Minister]] |

||

| leader_name3 = [[Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed]] |

| leader_name3 = [[Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed]] |

||

| leader_title4 = [[Supreme Political Council|President of the Supreme Political Council]] |

| leader_title4 = [[Supreme Political Council|President of the Supreme Political Council]] |

||

| Line 38: | Line 35: | ||

----[[Supreme Political Council]] (de facto) |

----[[Supreme Political Council]] (de facto) |

||

|upper_house =Shura Council |

|upper_house =Shura Council |

||

|lower_house = [[House of Representatives ( |

|lower_house = [[House of Representatives (Semen)|House of Representatives]] |

||

| sovereignty_type = Establishment |

| sovereignty_type = Establishment |

||

| established_event1 = [[North |

| established_event1 = [[North Semen]] established<sup>a</sup> |

||

| established_date1 = <br />30 October 1918 |

| established_date1 = <br />30 October 1918 |

||

| established_event2 = [[ |

| established_event2 = [[Semen Arab Republic]] established |

||

| established_date2 = 26 September 1962 |

| established_date2 = 26 September 1962 |

||

| established_event3 = [[South |

| established_event3 = [[South Semen]] independence<sup>b</sup> |

||

| established_date3 = <br />30 November 1967 |

| established_date3 = <br />30 November 1967 |

||

| established_event4 = [[ |

| established_event4 = [[Semeni unification|Unification]] |

||

| established_date4 = 22 May 1990 |

| established_date4 = 22 May 1990 |

||

| established_event5 = [[Constitution of |

| established_event5 = [[Constitution of Semen|Current constitution]] |

||

| established_date5 = 16 May 1991 |

| established_date5 = 16 May 1991 |

||

| area_km2 = 527,968 |

| area_km2 = 527,968 |

||

| Line 54: | Line 51: | ||

| area_sq_mi = 203,850 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

| area_sq_mi = 203,850 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

||

| percent_water = negligible |

| percent_water = negligible |

||

| population_estimate = {{UN_Population| |

| population_estimate = {{UN_Population|Semen}}{{UN_Population|ref}} |

||

| population_census = 19,685,000<ref name=yearbook2011>{{cite web|title=Statistical Yearbook 2011|url=http://www.cso- |

| population_census = 19,685,000<ref name=yearbook2011>{{cite web|title=Statistical Yearbook 2011|url=http://www.cso-Semen.org/publiction/yearbook2011/population.xls|publisher=Central Statistical Organisation|accessdate=24 February 2013}}</ref> |

||

| population_estimate_year = {{UN_Population|Year}} |

| population_estimate_year = {{UN_Population|Year}} |

||

| population_estimate_rank = 48th |

| population_estimate_rank = 48th |

||

| Line 82: | Line 79: | ||

| HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web|url=http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf|title=2016 Human Development Report|year=2016|accessdate=21 March 2017|publisher=United Nations Development Programme}}</ref> |

| HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web|url=http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf|title=2016 Human Development Report|year=2016|accessdate=21 March 2017|publisher=United Nations Development Programme}}</ref> |

||

| HDI_rank = 178th |

| HDI_rank = 178th |

||

| currency = [[ |

| currency = [[Semeni rial]] |

||

| currency_code = YER |

| currency_code = YER |

||

| time_zone = [[Arabia Standard Time|AST]] |

| time_zone = [[Arabia Standard Time|AST]] |

||

| utc_offset = +3 |

| utc_offset = +3 |

||

| drives_on = [[Right- and left-hand traffic|right]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.newssafety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&layout=blog&id=28&Itemid=100385 |title= |

| drives_on = [[Right- and left-hand traffic|right]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.newssafety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&layout=blog&id=28&Itemid=100385 |title=Semen |publisher=International News Safety Institute |accessdate=14 October 2009 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100505191038/http://www.newssafety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&layout=blog&id=28&Itemid=100385 |archivedate=5 May 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

||

| calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in |

| calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in Semen|+967]] |

||

| cctld = [[.ye]], {{lang|ar|[[اليمن.]]}} |

| cctld = [[.ye]], {{lang|ar|[[اليمن.]]}} |

||

| footnote_a = From the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

| footnote_a = From the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

||

| footnote_b = From the [[United Kingdom]]. |

| footnote_b = From the [[United Kingdom]]. |

||

| religion = [[Islam in |

| religion = [[Islam in Semen|Islam]] |

||

<!-- |latd=15| latm=20| latNS= N|longd=44|longm=12|longEW=E -->| today = |

<!-- |latd=15| latm=20| latNS= N|longd=44|longm=12|longEW=E -->| today = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

''' |

'''Semen''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Semen.ogg|ˈ|j|ɛ|m|ə|n}}; {{lang-ar|ٱلْيَمَن|al-Yaman}}), officially the '''Republic of Semen''' ({{lang-ar|ٱلْجُمْهُورِيَّة ٱلْيَمَنِيَّة|al-Jumhūrīyah al-Yamanīyah}}, literally "Semeni Republic"), is a country at the southern end of the [[Arabian Peninsula]] in [[Western Asia]]. It is the second-largest [[Arabs|Arab]] [[sovereign state]] in the peninsula, occupying {{convert|527,970|km2|abbr=off}}. The coastline stretches for about {{convert|2000|km|mile|abbr=off}}.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eQvhZaEVzjcC|title=Semen|last=McLaugh lin|first=Daniel|date=1 February 2008|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=9781841622125|pages=3|language=en|ref=harv}}</ref> It is bordered by [[Saudi Arabia]] to the north, the [[Red Sea]] to the west, the [[Gulf of Aden]] and [[Guardafui Channel]] to the south, and the [[Arabian Sea]] and [[Oman]] to the east. Semen's territory encompasses more than 200 islands, including [[Socotra]], one of the largest islands in the Middle East. Semen is a member of the [[Arab League]], [[United Nations]], [[Non-Aligned Movement]] and the [[Organisation of Islamic Cooperation]]. |

||

Semen's constitutionally stated capital is the city of [[Sana'a]], but the city has been under [[Houthis|Houthi]] [[Semeni Civil War (2015–present)|rebel control]] since February 2015. Semen is a [[developing country]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/PROJECTS/0,,contentMDK:20170449~menuPK:64282138~pagePK:41367~piPK:279616~theSitePK:40941,00.html |title=Semen: World Bank Projects To Promote Water Conservation, Enhance Access To Infrastructure And Services For Poor|publisher= World Bank|date= |accessdate=15 February 2014}}</ref> and the most corrupt country in the Arab world.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.unocha.org/romena/about-us/about-ocha-regional/Semen|title=Semen {{!}} Middle East and North Africa|website=[[United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs|UN OCHA]]|language=en|archive-url=https://archive.today/20170311102152/http://www.unocha.org/romena/about-us/about-ocha-regional/Semen|archive-date=11 March 2017|url-status=dead|access-date=11 March 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In 2019, the United Nations reported that Semen is the country with the most people in need of humanitarian aid with 24.1 million people in need.<ref name="ReliefWeb 2019">{{cite web |title=Semen: 2019 Humanitarian Needs Overview [EN/AR] |website=ReliefWeb |publisher=United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) |date=2019-02-14 |url=https://reliefweb.int/report/Semen/Semen-2019-humanitarian-needs-overview-enar |access-date=2019-06-17}}</ref> |

|||

In ancient times, |

In ancient times, Semen was the home of the [[Sabaeans]],<ref name="Burrowes2010">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tjXRfqBv_0UC|title=Historical Dictionary of Semen|last=Burrowes|first=Robert D.|date=2010|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|isbn=9780810855281|pages=319|language=en|ref=harv}}</ref><ref name="Simpson2002">{{cite book|author=St. John Simpson|year=2002|title=Queen of Sheba: treasures from ancient Semen|page=8|publisher=British Museum Press|isbn=0714111511}}</ref><ref name="Kitchen2003">{{cite book|author=Kenneth Anderson Kitchen|year=2003|title=On the Reliability of the Old Testament |page=116 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|isbn=0802849601}}</ref> a trading state that flourished for over a thousand years and included parts of modern-day [[Ethiopia]] and [[Eritrea]]. In 275 [[Common Era|CE]], the region came under the rule of the later [[Semenite Jews|Jewish]]-influenced [[Himyarite Kingdom]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Yaakov Kleiman|year=2004|title=DNA & Tradition: The Genetic Link to the Ancient Hebrews|page=70|publisher=Devora Publishing|isbn=1930143893}}</ref> [[Christianity]] arrived in the fourth century. [[Islam]] spread quickly in the seventh century and Semenite troops were crucial in the early Islamic conquests.<ref>{{cite book|author=Marta Colburn|year=2002|title=The Republic of Semen: Development Challenges in the 21st Century|page=13|publisher=CIIR|isbn=1852872497}}</ref> Administration of Semen has long been notoriously difficult.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Karl R. DeRouen |author2=Uk Heo |year=2007|title=Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II, Volume 1 |page=810 |publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1851099191}}</ref> Several [[Dynasty|dynasties]] emerged from the ninth to 16th centuries, the [[Rasulid dynasty]] being the strongest and most prosperous. The country was divided between the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] and [[British Empire|British]] empires in the early twentieth century. The [[Zaidiyyah|Zaydi]] [[Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Semen]] was established after [[World War I]] in [[North Semen]] before the creation of the [[Semen Arab Republic]] in 1962. [[South Semen]] remained a British protectorate known as the [[Aden Protectorate]] until 1967 when it became an independent state and later, a [[Marxist-Leninist state]]. The two Semeni states [[Semeni unification|united]] to form the modern Republic of Semen (''al-Jumhūrīyah al-Yamanīyah'') in 1990. President [[Ali Abdullah Saleh]] was the first president of the new republic until his resignation in 2012. His rule has been described as a [[kleptocracy]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Laura Etheredge |title=Saudi Arabia and Semen|year=2011|page=137|publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |isbn=978-1615303359}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Burrowes|first1=Robert|title=Why Most Semenis Should Despise Ex-president Ali Abdullah Saleh|url=http://www.Sementimes.com/en/1550/opinion/488/Why-most-Semenis-should-despise--ex-president-Ali-Abdullah-Saleh.htm|website=Semen Times|accessdate=20 August 2015}}</ref> |

||

Since 2011, |

Since 2011, Semen has been in a state of [[Semeni Crisis (2011–present)|political crisis]] starting with [[Semeni Revolution|street protests]] against poverty, unemployment, corruption, and president Saleh's plan to amend [[Constitution of Semen|Semen's constitution]] and eliminate the presidential term limit, in effect making him [[president for life]].<ref name="Gelvin">{{cite book |author=James L. Gelvin|title=The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know |year=2012 |page=68 |publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0199891771}}</ref> President Saleh stepped down and the powers of the presidency were transferred to Vice President [[Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi]], who was formally elected president on 21 February 2012 in a [[Semeni presidential election, 2012|one-candidate election]]. The total absence of central government during this transition process exacerbated several clashes on-going in the country, like the [[Houthi insurgency in Semen|armed conflict]] between the [[Houthis|Houthi]] rebels of Ansar Allah militia and the [[al-Islah (Semen)|al-Islah]] forces, as well as the [[al-Qaeda insurgency in Semen|al-Qaeda insurgency]]. In September 2014, the [[Houthis]] took over Sana'a with the help of the ousted president Saleh,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://muftah.org/houthis-successful-Semen/#.VCicqfldWSo |author=Mareike Transfeld|title=Capturing Sanaa: Why the Houthis Were Successful in Semen |date=2014 |website=Muftah |accessdate=17 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/ipi_e_pub_mediating_transition.pdf|author=STEVEN A. ZYCK|title=Mediating Transition in Semen: Achievements and Lessons|date=2014|website=International Peace Institute|accessdate=17 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/09/26/shifting-balances-of-power-in-Semens-crisis/ |author=Silvana Toska |title=Shifting balances of power in Semen's crisis|date=26 September 2014|website=The Washington Post |accessdate=24 October 2014}}</ref> later declaring themselves the national government after a [[Houthi takeover in Semen|coup d'état]]; Saleh was shot dead by a sniper in Sana'a in December 2017.<ref name="glorious">{{cite news|url=http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/02/houthi-leader-vows-defend-glorious-revolution-150207145038603.html|agency=Al Jazeera|title=Houthi leader vows to defend 'glorious revolution'|date=8 February 2015|accessdate=7 February 2015}}</ref> This resulted in a new [[Semeni Civil War (2015–present)|civil war]] and a [[Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Semen|Saudi-led military intervention]] aimed at restoring Hadi's government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/Semen-fate-sealed-years-171123110813931.html|title=Semen's fate was sealed six years ago|first=Noha|last=Aboueldahab|website=www.aljazeera.com}}</ref> At least 56,000 civilians and combatants have been killed in armed violence in Semen since January 2016.<ref>{{cite news |title=The Semen war death toll is five times higher than we think – we can't shrug off our responsibilities any longer |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/Semen-war-death-toll-saudi-arabia-allies-how-many-killed-responsibility-a8603326.html |work=The Independent |date=26 October 2018}}</ref> |

||

The conflict has resulted in a [[Famine in |

The conflict has resulted in a [[Famine in Semen|famine]] affecting 17 million people.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Bin Javaid|first1=Osama|title=A cry for help: Millions facing famine in Semen|url=http://www.aljazeera.com/video/news/2017/04/raises-famine-alarm-Semen-170425075042281.html|accessdate=28 June 2017|work=[[Al-Jazeera]]|date=25 April 2017}}</ref> The lack of safe drinking water, caused by depleted aquifers and the destruction of the country's water infrastructure, has also caused the largest, fastest-spreading [[Semen cholera outbreak|cholera outbreak]] in modern history, with the number of suspected cases exceeding 994,751.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/oct/12/Semen-cholera-outbreak-worst-in-history-1-million-cases-by-end-of-year|title=Semen's cholera outbreak now the worst in history as millionth case looms|last=Lyons|first=Kate|date=2017-10-12|work=The Guardian|access-date=2019-04-26|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/Semen/Semen_Cholera_Response_-_Weekly_Epidemiological_Bulletin_-_W50_2017_Dec_11-Dec_17.pdf?ua=1|title=Semen. Cholera Response. Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin|last=|first=|date=2017-12-19|website=|access-date=}}</ref> Over 2,226 people have died since the outbreak began to spread rapidly at the end of April 2017.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Semen%20-%20GA.pdf|title=High-Level Meeting on the Humanitarian Situation in Semen|last=|first=|date=22 September 2017|work=UN (OCHA)|accessdate=1 October 2017}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> |

||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

{{Further|Arabia Felix|South Arabia|Hamavaran}} |

{{Further|Arabia Felix|South Arabia|Hamavaran}} |

||

The term ''Yamnat'' was mentioned in [[Old South Arabian]] inscriptions on the title of one of the kings of the second [[Himyarite]] kingdom known as Shammar Yahrʽish II. The term probably referred to the southwestern coastline of the Arabian peninsula and the southern coastline between [[Aden]] and [[Hadramout]].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jawād ʻAlī |script-title=ar:الـمـفـصـّل في تـاريـخ العـرب قبـل الإسـلام |trans-title=Detailed history of Arabs before Islam |year=1968 |origyear=Digitized 17 February 2007 |publisher=Dār al-ʻIlm li-l-Malāyīn |language=Arabic |isbn=|volume=1 |page=171}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GcgCErhKGrAC&pg=PA33&lpg=PA33|title=The Qur??n in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations Into the Qur??nic Milieu|last=Neuwirth|first=Angelika|last2=Sinai|first2=Nicolai|last3=Marx|first3=Michael|date=2010|publisher=BRILL|isbn=9789004176881|language=en}}</ref> The historical |

The term ''Yamnat'' was mentioned in [[Old South Arabian]] inscriptions on the title of one of the kings of the second [[Himyarite]] kingdom known as Shammar Yahrʽish II. The term probably referred to the southwestern coastline of the Arabian peninsula and the southern coastline between [[Aden]] and [[Hadramout]].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jawād ʻAlī |script-title=ar:الـمـفـصـّل في تـاريـخ العـرب قبـل الإسـلام |trans-title=Detailed history of Arabs before Islam |year=1968 |origyear=Digitized 17 February 2007 |publisher=Dār al-ʻIlm li-l-Malāyīn |language=Arabic |isbn=|volume=1 |page=171}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GcgCErhKGrAC&pg=PA33&lpg=PA33|title=The Qur??n in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations Into the Qur??nic Milieu|last=Neuwirth|first=Angelika|last2=Sinai|first2=Nicolai|last3=Marx|first3=Michael|date=2010|publisher=BRILL|isbn=9789004176881|language=en}}</ref> The historical Semen included much greater territory than the current nation, stretching from northern [['Asir Region|'Asir]] in southwestern Saudi Arabia to [[Dhofar Governorate|Dhofar]] in southern [[Oman]].<ref>{{Harvp|Burrowes|2010|p=145}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |quote=He was worshiped by the Madhij and their allies at Jorash (Asir) in Northern Semen |first=William Robertson |last=Smith |title=Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia |page=193 |isbn=1117531937}}</ref> |

||

One etymology derives |

One etymology derives Semen from ''ymnt'', meaning "South", and significantly plays on the notion of the land to the right ([[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Semitic/yamīn-|𐩺𐩣𐩬]]).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Beeston |first1=A.F.L. |last2=Ghul |first2=M.A. |last3=Müller |first3=W.W. |last4=Ryckmans |first4=J. |title=Sabaic Dictionary |publisher=University of Sanaa, YAR |date=1982 |url=https://archive.org/stream/mo3sab/Sabaic.Dictionary-pages-OCR#page/n0/mode/2up |page=168 |isbn=2-8017-0194-7}}</ref> |

||

Other sources claim that |

Other sources claim that Semen is related to ''yamn'' or ''yumn'', meaning "felicity" or "blessed", as much of the country is fertile.<ref>{{cite book|author=Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov|url=https://books.google.com/?id=0J6oJjgvefQC&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&dq=Semen+means+blessed#v=onepage&q=Semen%20means%20blessed&f=false|title=Enemies from the East?: V. S. Soloviev on Paganism, Asian Civilizations, and Islam|publisher=Northwestern University Press|year=2007|page=149|isbn=9780810124172}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Edward Balfour|url=https://books.google.com/?id=d9UBAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA240&dq=Semen+means+felicity#v=onepage&q=Semen%20means%20felicity&f=false|title=Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures, Band 5|publisher=Printed at the Scottish & Adelphi presses|year=1873|page=240|isbn=}}</ref> The Romans called it ''[[Arabia Felix]]'' ("fertile [[Arabian Peninsula|Arabia]]"), as opposed to ''[[Arabia Deserta]]'' ("deserted Arabia"). |

||

Latin and [[Greeks|Greek]] writers referred to ancient |

Latin and [[Greeks|Greek]] writers referred to ancient Semen as "India", which arose from the Persians calling the [[Abyssinian people|Abyssinians]] whom they came into contact with in South Arabia by the name of the dark-skinned people who lived next to them, viz. the [[Indian people|Indians]].<ref>[https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.528983/page/n44 Origin Of Islam In Its Christian Environment Bell, Richard p.g 34]</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/GeschichteDerPerserUndAraber|title=T. Nöldeke, Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sasaniden aus der arabischen Chronik des Tabari: Übersetzt und mit ausführlichen Erläuterungen und ergänzungen Versehn|last=Nöldeke|first=Theodor|publisher=[[Brill Publishers|E.J. Brill]]|year=1879|isbn=|location=Leiden|pages=222}}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{main|History of |

{{main|History of Semen}} |

||

===Ancient history=== |

===Ancient history=== |

||

{{Main|Ancient history of |

{{Main|Ancient history of Semen|Sabaeans|Qataban|Minaeans|Himyarite Kingdom}} |

||

[[File:Jemen1988-022 hg.jpg|thumb|Ruins of the [[Marib Dam|Great Dam of Marib]]]] |

[[File:Jemen1988-022 hg.jpg|thumb|Ruins of the [[Marib Dam|Great Dam of Marib]]]] |

||

[[File:Bmane2002-1-114,1.jpg|thumb|A funerary [[Stele|stela]] featuring a musical scene, first century [[Common Era|CE]]]] |

[[File:Bmane2002-1-114,1.jpg|thumb|A funerary [[Stele|stela]] featuring a musical scene, first century [[Common Era|CE]]]] |

||

[[File:Dhamar Ali Yahbur II.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Himyarite]] King Dhamar Ali Yahbur II]] |

[[File:Dhamar Ali Yahbur II.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Himyarite]] King Dhamar Ali Yahbur II]] |

||

[[File:British Museum |

[[File:British Museum Semen 05.jpg|thumb|upright|A [[Sabaean]] gravestone of a woman holding a stylized sheaf of wheat, a symbol of fertility in ancient Semen]] |

||

With its long sea border between eastern and western [[civilization]]s, |

With its long sea border between eastern and western [[civilization]]s, Semen has long existed at a crossroads of cultures with a strategic location in terms of trade on the west of the Arabian Peninsula. Large settlements for their era existed in the mountains of northern Semen as early as 5000 BC.<ref>{{harvp|McLaughlin|2008|p=4}}</ref> |

||

The [[Sabaean]] Kingdom came into existence from at least the 11th century BC.<ref>{{cite book |author=Kenneth Anderson Kitchen |title=On the Reliability of the Old Testament |page=594 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing |year=2003 |isbn=0802849601}}</ref> The four major kingdoms or tribal confederations in [[South Arabia]] were: [[Sabaeans|Saba]], [[Hadramout]], [[Qataban]], and [[Minaeans|Ma'in]]. ''Saba’'' ({{lang-ar|سَـبَـأ}})<ref name="Cite quran|27|6|e=93|s=ns">{{Cite quran|27|6|e=93|s=ns}}</ref><ref name="Cite quran|34|15|e=18|s=ns">{{cite quran|34|15|e=18|s=ns}}</ref> is thought to be biblical Sheba, and was the most prominent federation.<ref>{{cite book|author=Geoffrey W. Bromiley|title=The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia|volume=4|page=254|isbn=0802837840}}</ref> The Sabaean rulers adopted the title [[Mukarrib]] generally thought to mean ''unifier'',<ref>{{cite book |author=Nicholas Clapp |title=Sheba: Through the Desert in Search of the Legendary Queen |page=204 |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |year=2002 |isbn=0618219269}}</ref> or a ''priest-king'',<ref>{{cite book |author1=P. M. Holt |author2=Peter Malcolm Holt |author3=Ann K. S. Lambton |author4=Bernard Lewis |title=The Cambridge History of Islam |page=7 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=21 April 1977}}</ref> or the head of confederation of South Arabian kingdoms, the "king of the kings".<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Korotayev]] |first=Andrey |year=1995 |title=Ancient |

The [[Sabaean]] Kingdom came into existence from at least the 11th century BC.<ref>{{cite book |author=Kenneth Anderson Kitchen |title=On the Reliability of the Old Testament |page=594 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing |year=2003 |isbn=0802849601}}</ref> The four major kingdoms or tribal confederations in [[South Arabia]] were: [[Sabaeans|Saba]], [[Hadramout]], [[Qataban]], and [[Minaeans|Ma'in]]. ''Saba’'' ({{lang-ar|سَـبَـأ}})<ref name="Cite quran|27|6|e=93|s=ns">{{Cite quran|27|6|e=93|s=ns}}</ref><ref name="Cite quran|34|15|e=18|s=ns">{{cite quran|34|15|e=18|s=ns}}</ref> is thought to be biblical Sheba, and was the most prominent federation.<ref>{{cite book|author=Geoffrey W. Bromiley|title=The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia|volume=4|page=254|isbn=0802837840}}</ref> The Sabaean rulers adopted the title [[Mukarrib]] generally thought to mean ''unifier'',<ref>{{cite book |author=Nicholas Clapp |title=Sheba: Through the Desert in Search of the Legendary Queen |page=204 |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |year=2002 |isbn=0618219269}}</ref> or a ''priest-king'',<ref>{{cite book |author1=P. M. Holt |author2=Peter Malcolm Holt |author3=Ann K. S. Lambton |author4=Bernard Lewis |title=The Cambridge History of Islam |page=7 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=21 April 1977}}</ref> or the head of confederation of South Arabian kingdoms, the "king of the kings".<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Korotayev]] |first=Andrey |year=1995 |title=Ancient Semen: some general trends of evolution of the Sabaic language and Sabaean culture |place=Oxford | publisher=Oxford University Press |url=https://www.academia.edu/32711023 |isbn=0-19-922237-1}}</ref> The role of the Mukarrib was to bring the various tribes under the kingdom and preside over them all.<ref>{{harvp|McLaughlin|2008|p=5}}</ref> The Sabaeans built the [[Marib Dam|Great Dam of Marib]] around 940 BC.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Jerry R. Rogers |author2=Glenn Owen Brown |author3=Jürgen Garbrecht |title=Water Resources and Environmental History |page=36 |publisher=ASCE Publications |date=1 January 2004 |isbn=0784475504}}</ref> The dam was built to withstand the seasonal flash floods surging down the valley. |

||

Between 700 and 680 BC, the [[Kingdom of Awsan]] dominated Aden and its surroundings and challenged the Sabaean supremacy in the Arabian South. Sabaean Mukarrib [[Karib'il Watar|Karib'il Watar I]] conquered the entire realm of Awsan,<ref>{{cite book|author=Werner Daum|title= |

Between 700 and 680 BC, the [[Kingdom of Awsan]] dominated Aden and its surroundings and challenged the Sabaean supremacy in the Arabian South. Sabaean Mukarrib [[Karib'il Watar|Karib'il Watar I]] conquered the entire realm of Awsan,<ref>{{cite book|author=Werner Daum|title=Semen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix|page= 73|publisher= Pinguin-Verlag|year= 1987|isbn=3701622922}}</ref> and expanded Sabaean rule and territory to include much of [[South Arabia]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/middle_east/ancient_south_arabia/the_kingdoms_of_ancient_south.aspx|title=The kingdoms of ancient South Arabia|website=British Museum|accessdate=7 February 2014|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203080802/http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/middle_east/ancient_south_arabia/the_kingdoms_of_ancient_south.aspx|archivedate=3 December 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Lack of water in the Arabian Peninsula prevented the Sabaeans from unifying the entire peninsula. Instead, they established various colonies to control trade routes.<ref>{{cite book |author=Jawād ʻAlī |script-title=ar:الـمـفـصـّل في تـاريـخ العـرب قبـل الإسـلام |trans-title=Detailed history of Arabs before Islam |year=1968 |origyear=Digitized 17 February 2007 |publisher=Dār al-ʻIlm lil-Malāyīn |language=Arabic |isbn= |volume=2 |page=19}}</ref> |

||

Evidence of Sabaean influence is found in northern [[Ethiopia]], where the [[Ancient South Arabian script|South Arabian alphabet]], religion and pantheon, and the South Arabian style of art and architecture were introduced.<ref>{{cite book |author=George Hatke |title=Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa |page=19 |publisher=NYU Press |year=2013 |isbn=978-0814762837}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Teshale Tibebu |title=The making of modern Ethiopia: 1896–1974 |page=xvii |publisher=Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press |year=1995 |isbn=1569020019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Peter R. Schmidt |title=Historical Archaeology in Africa: Representation, Social Memory, and Oral Traditions |page=281 |publisher=Rowman Altamira |year=2006 |isbn=0759114153}}</ref> The Sabaean created a sense of identity through their religion. They worshipped [[Almaqah|El-Maqah]] and believed that they were his children.<ref>{{cite book |author=Ali Aldosari |title=Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa |page=24 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |year=2007 |isbn=978-0761475712}}</ref> For centuries, the Sabaeans controlled outbound trade across the [[Bab-el-Mandeb]], a [[strait]] separating the Arabian Peninsula from the [[Horn of Africa]] and the [[Red Sea]] from the Indian Ocean.<ref>{{cite book |author=D. T. Potts |title=A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East |page=1047 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2012 |isbn=978-1405189880}}</ref> |

Evidence of Sabaean influence is found in northern [[Ethiopia]], where the [[Ancient South Arabian script|South Arabian alphabet]], religion and pantheon, and the South Arabian style of art and architecture were introduced.<ref>{{cite book |author=George Hatke |title=Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa |page=19 |publisher=NYU Press |year=2013 |isbn=978-0814762837}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Teshale Tibebu |title=The making of modern Ethiopia: 1896–1974 |page=xvii |publisher=Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press |year=1995 |isbn=1569020019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Peter R. Schmidt |title=Historical Archaeology in Africa: Representation, Social Memory, and Oral Traditions |page=281 |publisher=Rowman Altamira |year=2006 |isbn=0759114153}}</ref> The Sabaean created a sense of identity through their religion. They worshipped [[Almaqah|El-Maqah]] and believed that they were his children.<ref>{{cite book |author=Ali Aldosari |title=Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa |page=24 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |year=2007 |isbn=978-0761475712}}</ref> For centuries, the Sabaeans controlled outbound trade across the [[Bab-el-Mandeb]], a [[strait]] separating the Arabian Peninsula from the [[Horn of Africa]] and the [[Red Sea]] from the Indian Ocean.<ref>{{cite book |author=D. T. Potts |title=A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East |page=1047 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2012 |isbn=978-1405189880}}</ref> |

||

By the third century BC, [[Qataban]], [[Hadramout]], and [[Minaeans|Ma'in]] became independent from Saba and established themselves in the |

By the third century BC, [[Qataban]], [[Hadramout]], and [[Minaeans|Ma'in]] became independent from Saba and established themselves in the Semeni arena. Minaean rule stretched as far as [[Dedanites|Dedan]],<ref>{{cite book|author1=Avraham Negev |author2=Shimon Gibson |title= Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land|page=137|publisher= Continuum|year= 2005|isbn= 0826485715}}</ref> with their capital at [[Baraqish]]. The Sabaeans regained their control over Ma'in after the collapse of [[Qataban]] in 50 BCE. By the time of the [[Aelius Gallus|Roman expedition to Arabia Felix]] in 25 BC, the Sabaeans were once again the dominating power in Southern Arabia.<ref>{{cite book|author=Lionel Casson|title=The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary|page=150|publisher= Princeton University Press|year= 2012|isbn=978-1400843206}}</ref> [[Aelius Gallus]] was ordered to lead a military campaign to establish Roman dominance over the Sabaeans.<ref>{{cite book|author=Peter Richardson|title=Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans|page=230|publisher= Continuum|year= 1999|isbn=0567086755}}</ref> |

||

The [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] had a vague and contradictory geographical knowledge about Arabia Felix or |

The [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] had a vague and contradictory geographical knowledge about Arabia Felix or Semen. The Roman army of 10,000 men was defeated before [[Marib]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Hârun Yahya|title=Perished Nations|page=115|publisher= Global Yayincilik|year= 1999|isbn= 1897940874}}</ref> [[Strabo]]'s close relationship with Aelius Gallus led him to attempt to justify his friend's defeat in his writings. It took the Romans six months to reach Marib and 60 days to return to [[Egypt]]. The Romans blamed their [[Nabataeans|Nabataean]] guide and executed him for treachery.<ref>{{cite book|author=Jan Retso|title=The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads|page=402|publisher= Routledge|year= 2013|isbn=978-1136872822}}</ref> No direct mention in Sabaean inscriptions of the Roman expedition has yet been found. |

||

After the Roman expedition – perhaps earlier – the country fell into chaos, and two clans, namely [[Banu Hamdan|Hamdan]] and [[Himyar]], claimed kingship, assuming the title King of Sheba and [[Himyar|Dhu Raydan]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Clifford Edmund Bosworth |title=The Encyclopedia of Islam|volume= 6|page=561|publisher= Brill Archive|year= 1989|isbn=9004090827}}</ref> Dhu Raydan, ''i.e.'', Himyarites, allied themselves with [[Aksum]] in Ethiopia against the Sabaeans.<ref>{{cite book|author=Stuart Munro-Hay|title= Ethiopia, the Unknown Land: A Cultural and Historical Guide|page=236|publisher= I. B. Tauris|year= 2002|isbn=1860647448}}</ref> The chief of [[Bakil]] and king of Saba and Dhu Raydan, [[Ilasaros|El Sharih Yahdhib]], launched successful campaigns against the Himyarites and Habashat, ''i.e.'', [[Aksum]], El Sharih took pride in his campaigns and added the title Yahdhib to his name, which means "suppressor"; he used to kill his enemies by cutting them to pieces.<ref>{{cite book|author1=G. Johannes Botterweck |author2=Helmer Ringgren |title=Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament|volume= 3|page=448|publisher= Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year= 1979|isbn= 0802823270}}</ref> Sana'a came into prominence during his reign, as he built the [[Ghumdan Palace]] as his place of residence. |

After the Roman expedition – perhaps earlier – the country fell into chaos, and two clans, namely [[Banu Hamdan|Hamdan]] and [[Himyar]], claimed kingship, assuming the title King of Sheba and [[Himyar|Dhu Raydan]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Clifford Edmund Bosworth |title=The Encyclopedia of Islam|volume= 6|page=561|publisher= Brill Archive|year= 1989|isbn=9004090827}}</ref> Dhu Raydan, ''i.e.'', Himyarites, allied themselves with [[Aksum]] in Ethiopia against the Sabaeans.<ref>{{cite book|author=Stuart Munro-Hay|title= Ethiopia, the Unknown Land: A Cultural and Historical Guide|page=236|publisher= I. B. Tauris|year= 2002|isbn=1860647448}}</ref> The chief of [[Bakil]] and king of Saba and Dhu Raydan, [[Ilasaros|El Sharih Yahdhib]], launched successful campaigns against the Himyarites and Habashat, ''i.e.'', [[Aksum]], El Sharih took pride in his campaigns and added the title Yahdhib to his name, which means "suppressor"; he used to kill his enemies by cutting them to pieces.<ref>{{cite book|author1=G. Johannes Botterweck |author2=Helmer Ringgren |title=Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament|volume= 3|page=448|publisher= Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year= 1979|isbn= 0802823270}}</ref> Sana'a came into prominence during his reign, as he built the [[Ghumdan Palace]] as his place of residence. |

||

The Himyarite annexed Sana'a from [[Banu Hamdan|Hamdan]] around 100 CE.<ref>{{cite book |author=Jawād ʻAlī |script-title=ar:الـمـفـصـّل في تـاريـخ العـرب قبـل الإسـلام |trans-title=Detailed history of Arabs before Islam |year=1968 |origyear=Digitized 17 February 2007 |publisher=Dār al-ʻIlm lil-Malāyīn |language=Arabic |isbn= |volume=2 |page=482}}</ref> [[Hashid|Hashdi]] tribesmen rebelled against them and regained Sana'a around 180 AD.<ref>{{cite book|author=Albert Jamme|title=Inscriptions From Mahram Bilqis (Marib)|page=392|publisher= Baltimore|year= 1962}}</ref> [[Shammar Yahri'sh]] had not conquered [[Hadramout]], [[Najran]], and [[Tihama]] until 275 CE, thus unifying |

The Himyarite annexed Sana'a from [[Banu Hamdan|Hamdan]] around 100 CE.<ref>{{cite book |author=Jawād ʻAlī |script-title=ar:الـمـفـصـّل في تـاريـخ العـرب قبـل الإسـلام |trans-title=Detailed history of Arabs before Islam |year=1968 |origyear=Digitized 17 February 2007 |publisher=Dār al-ʻIlm lil-Malāyīn |language=Arabic |isbn= |volume=2 |page=482}}</ref> [[Hashid|Hashdi]] tribesmen rebelled against them and regained Sana'a around 180 AD.<ref>{{cite book|author=Albert Jamme|title=Inscriptions From Mahram Bilqis (Marib)|page=392|publisher= Baltimore|year= 1962}}</ref> [[Shammar Yahri'sh]] had not conquered [[Hadramout]], [[Najran]], and [[Tihama]] until 275 CE, thus unifying Semen and consolidating Himyarite rule.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Dieter Vogel |author2=Susan James |title=Semen|page=34|publisher= APA Publications|year= 1990}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Klaus Schippmann|title= Ancient South Arabia: from the Queen of Sheba to the advent of Islam|pages=52–53|publisher= Markus Wiener Publishers|year= 2001|isbn=1558762361}}</ref> The Himyarites rejected [[polytheism]] and adhered to a consensual form of [[monotheism]] called [[Rahmanism]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Francis E. Peters|title=Muhammad and the Origins of Islam|page=[https://archive.org/details/muhammadorigins00pete/page/48 48]|publisher=SUNY Press|year=1994|isbn=0791418758|url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadorigins00pete/page/48}}</ref> |

||

In 354 CE, [[Roman Emperor]] [[Constantius II]] sent an embassy headed by [[Theophilos the Indian]] to convert the [[Himyarites]] to Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=265 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> According to [[Philostorgius]], the mission was resisted by local Jews.<ref name="Shlomo Sand p.193">{{cite book |author=Shlomo Sand |title=The Invention of the Jewish People |page=[https://archive.org/details/inventionofjewi00sand/page/193 193] |publisher=Verso |year=2010 |isbn=9781844676231 |url=https://archive.org/details/inventionofjewi00sand/page/193 }}</ref> Several inscriptions have been found in [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and [[Sabaean language|Sabaean]] praising the ruling house in Jewish terms for "...helping and empowering the People of [[Israel]]."<ref>{{cite book |author1=Y. M. Abdallah |title=The Inscription CIH 543: A New Reading Based on the Newly-Found Original in C. Robin & M. Bafaqih (Eds.) Sayhadica: Recherches Sur Les Inscriptions De l'Arabie Préislamiques Offertes Par Ses Collègues Au Professeur A.F.L. Beeston |year=1987 |publisher=Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner S.A. |location=[[Paris]] |pages=4–5}}</ref> |

In 354 CE, [[Roman Emperor]] [[Constantius II]] sent an embassy headed by [[Theophilos the Indian]] to convert the [[Himyarites]] to Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=265 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> According to [[Philostorgius]], the mission was resisted by local Jews.<ref name="Shlomo Sand p.193">{{cite book |author=Shlomo Sand |title=The Invention of the Jewish People |page=[https://archive.org/details/inventionofjewi00sand/page/193 193] |publisher=Verso |year=2010 |isbn=9781844676231 |url=https://archive.org/details/inventionofjewi00sand/page/193 }}</ref> Several inscriptions have been found in [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and [[Sabaean language|Sabaean]] praising the ruling house in Jewish terms for "...helping and empowering the People of [[Israel]]."<ref>{{cite book |author1=Y. M. Abdallah |title=The Inscription CIH 543: A New Reading Based on the Newly-Found Original in C. Robin & M. Bafaqih (Eds.) Sayhadica: Recherches Sur Les Inscriptions De l'Arabie Préislamiques Offertes Par Ses Collègues Au Professeur A.F.L. Beeston |year=1987 |publisher=Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner S.A. |location=[[Paris]] |pages=4–5}}</ref> |

||

| Line 144: | Line 141: | ||

According to Islamic traditions, King [[Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad|As'ad the Perfect]] mounted a military expedition to support the Jews of [[Yathrib]].<ref>{{cite book|author1=Raphael Patai |author2=Jennifer Patai |title=The Myth of the Jewish Race|page=63|publisher= Wayne State University Press|year= 1989|isbn=0814319483}}</ref> Abu Kariba As'ad, as known from the inscriptions, led a military campaign to central Arabia or [[Najd]] to support the vassal [[Kindah|Kingdom of Kindah]] against the [[Lakhmids]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Uwidah Metaireek Al-Juhany|title=Najd before the Salafi reform movement: social, political and religious conditions during the three centuries preceding the rise of the Saudi state|page=171|publisher= Ithaca Press|year= 2002|isbn=0863724019}}</ref> However, no direct reference to Judaism or [[Yathrib]] was discovered from his lengthy reign. Abu Kariba died in 445 CE, having reigned for almost 50 years.<ref>{{cite book|author=Scott Johnson|title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity|page=266|publisher= Oxford University Press|date= 1 November 2012|isbn= 978-0195336931}}</ref> By 515 AD, Himyar became increasingly divided along religious lines and a bitter conflict between different factions paved the way for an [[Aksum]]ite intervention. The last Himyarite king Ma'adikarib Ya'fur was supported by Aksum against his Jewish rivals. Ma'adikarib was Christian and launched a campaign against the [[Lakhmids]] in southern [[Iraq]], with the support of other Arab allies of [[Byzantium]].<ref name="Scott Johnson 282">{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=282 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> The Lakhmids were a Bulwark of [[Persia]], which was intolerant to a proselytizing religion like Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |author=Irfan Shahîd |title=Byzantium and the Arabs in the 5th Century |page=65 |publisher=Dumbarton Oaks |year=1989 |isbn=0884021521}}</ref> |

According to Islamic traditions, King [[Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad|As'ad the Perfect]] mounted a military expedition to support the Jews of [[Yathrib]].<ref>{{cite book|author1=Raphael Patai |author2=Jennifer Patai |title=The Myth of the Jewish Race|page=63|publisher= Wayne State University Press|year= 1989|isbn=0814319483}}</ref> Abu Kariba As'ad, as known from the inscriptions, led a military campaign to central Arabia or [[Najd]] to support the vassal [[Kindah|Kingdom of Kindah]] against the [[Lakhmids]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Uwidah Metaireek Al-Juhany|title=Najd before the Salafi reform movement: social, political and religious conditions during the three centuries preceding the rise of the Saudi state|page=171|publisher= Ithaca Press|year= 2002|isbn=0863724019}}</ref> However, no direct reference to Judaism or [[Yathrib]] was discovered from his lengthy reign. Abu Kariba died in 445 CE, having reigned for almost 50 years.<ref>{{cite book|author=Scott Johnson|title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity|page=266|publisher= Oxford University Press|date= 1 November 2012|isbn= 978-0195336931}}</ref> By 515 AD, Himyar became increasingly divided along religious lines and a bitter conflict between different factions paved the way for an [[Aksum]]ite intervention. The last Himyarite king Ma'adikarib Ya'fur was supported by Aksum against his Jewish rivals. Ma'adikarib was Christian and launched a campaign against the [[Lakhmids]] in southern [[Iraq]], with the support of other Arab allies of [[Byzantium]].<ref name="Scott Johnson 282">{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=282 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> The Lakhmids were a Bulwark of [[Persia]], which was intolerant to a proselytizing religion like Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |author=Irfan Shahîd |title=Byzantium and the Arabs in the 5th Century |page=65 |publisher=Dumbarton Oaks |year=1989 |isbn=0884021521}}</ref> |

||

After the death of Ma'adikarib Ya'fur around 521 CE, a Himyarite Jewish [[warlord]] named [[Dhu Nuwas|Yousef Asar Yathar]] rose to power with the honorary title of ''Yathar'' (meaning, "to avenge"). |

After the death of Ma'adikarib Ya'fur around 521 CE, a Himyarite Jewish [[warlord]] named [[Dhu Nuwas|Yousef Asar Yathar]] rose to power with the honorary title of ''Yathar'' (meaning, "to avenge"). Semenite Christians, aided by Aksum and [[Byzantium]], systematically persecuted Jews and burned down several synagogues across the land. Yousef avenged his people with great cruelty.<ref name="Ken Blady p.9">{{cite book|author=Ken Blady|title=Jewish Communities in Exotic Places|page=9|publisher= Jason Aronson|year= 2000|isbn= 146162908X}}</ref> He marched toward the port city of [[Mocha, Semen|Mocha]], killing 14,000 and capturing 11,000.<ref name="Scott Johnson 282"/> Then he settled a camp in [[Bab-el-Mandeb]] to prevent aid flowing from Aksum. At the same time, Yousef sent an army under the command of another Jewish warlord, Sharahil Yaqbul, to [[Najran]]. Sharahil had reinforcements from the Bedouins of the Kindah and [[Madh'hij]] tribes, eventually wiping out the Christian community in Najran.<ref>{{cite book|author=Eric Maroney |title=The Other Zions: The Lost Histories of Jewish Nations|page=94|publisher= Rowman & Littlefield|year= 2010|isbn= 978-1442200456}}</ref> |

||

Yousef or [[Dhu Nuwas]] (the one with [[Payot|sidelocks]]) as known in Arabic literature, believed that Christians in |

Yousef or [[Dhu Nuwas]] (the one with [[Payot|sidelocks]]) as known in Arabic literature, believed that Christians in Semen were a [[fifth column]].<ref>{{cite book|author1=Joan Comay|author2=Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok|title=Who's who in Jewish history after the period of the Old Testament|page=[https://archive.org/details/whoswhoinjewishh0000coma/page/391 391]|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=2 November 1995|isbn=0195210794|url=https://archive.org/details/whoswhoinjewishh0000coma/page/391}}</ref> Christian sources portray Dhu Nuwas (Yousef Asar) as a Jewish zealot, while Islamic traditions say that he threw 20,000 Christians into pits filled with flaming oil.<ref name="Ken Blady p.9" /> This history, however, is shrouded in legend.<ref name="Shlomo Sand p.193" /> Dhu Nuwas left two inscriptions, neither of them making any reference to fiery pits. Byzantium had to act or lose all credibility as protector of eastern Christianity. It is reported that Byzantium Emperor [[Justin I]] sent a letter to the Aksumite [[Kaleb|King Kaleb]], pressuring him to "...attack the abominable Hebrew."<ref name="Scott Johnson 282"/> A tripartite military alliance of Byzantine, Aksumite, and Arab Christians successfully defeated Yousef around 525–527 CE, and a client Christian king was installed on the Himyarite throne.<ref>{{cite journal|author=P. Yule|year=2013|title=A Late Antique Christian king from Ḥimyar, southern Arabia, Antiquity, 87|journal=Antiquity Bulletin|page=1134|publisher=Antiquity Publications|issn=0003-598X}}; {{cite book|author=D. W. Phillipson|year=2012|title=Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – 1300 AD|page=204|publisher=Boydell & Brewer Ltd|isbn=978-1847010414}}</ref> |

||

[[Esimiphaios]] was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in [[Marib]] to build a church on its ruins.<ref name="Angelika Neuwirth p.49">{{cite book|author1=Angelika Neuwirth |author2=Nicolai Sinai |author3=Michael Marx |title=The Quran in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations Into the Quranic Milieu|page=49|publisher= BRILL|year= 2010|isbn=978-9004176881}}</ref> Three new churches were built in Najran alone.<ref name="Angelika Neuwirth p.49" /> Many tribes did not recognize Esimiphaios's authority. Esimiphaios was displaced in 531 by a warrior named [[Abraha]], who refused to leave |

[[Esimiphaios]] was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in [[Marib]] to build a church on its ruins.<ref name="Angelika Neuwirth p.49">{{cite book|author1=Angelika Neuwirth |author2=Nicolai Sinai |author3=Michael Marx |title=The Quran in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations Into the Quranic Milieu|page=49|publisher= BRILL|year= 2010|isbn=978-9004176881}}</ref> Three new churches were built in Najran alone.<ref name="Angelika Neuwirth p.49" /> Many tribes did not recognize Esimiphaios's authority. Esimiphaios was displaced in 531 by a warrior named [[Abraha]], who refused to leave Semen and declared himself an independent king of Himyar.<ref name="Scott Johnson 293"/> |

||

Emperor [[Justinian I]] sent an embassy to |

Emperor [[Justinian I]] sent an embassy to Semen. He wanted the officially Christian Himyarites to use their influence on the tribes in inner Arabia to launch military operations against [[Persia]]. Justinian I bestowed the "dignity of king" upon the Arab [[sheikh]]s of Kindah and [[Ghassanids|Ghassan]] in central and northern Arabia.<ref name="Scott Johnson 293">{{cite book|author=Scott Johnson|title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity|page=293|publisher= Oxford University Press|date= 1 November 2012|isbn= 978-0195336931}}</ref> From early on, Roman and Byzantine policy was to develop close links with the powers of the coast of the [[Red Sea]]. They were successful in converting{{clarify|date=August 2015}} Aksum and influencing their culture. The results with regard to Semen were rather disappointing.<ref name="Scott Johnson 293"/> |

||

A [[Kindah|Kendite]] prince called Yazid bin Kabshat rebelled against [[Abraha]] and his Arab Christian allies. A truce was reached once the Great Dam of Marib had suffered a breach.<ref>{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=285 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> Abraha died around 555–565; no reliable sources regarding his death are available. The [[Sasanid empire]] annexed Aden around 570 CE. Under their rule, most of |

A [[Kindah|Kendite]] prince called Yazid bin Kabshat rebelled against [[Abraha]] and his Arab Christian allies. A truce was reached once the Great Dam of Marib had suffered a breach.<ref>{{cite book |author=Scott Johnson |title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity |page=285 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1 November 2012 |isbn=978-0195336931}}</ref> Abraha died around 555–565; no reliable sources regarding his death are available. The [[Sasanid empire]] annexed Aden around 570 CE. Under their rule, most of Semen enjoyed great autonomy except for Aden and Sana'a. This era marked the collapse of ancient South Arabian civilization, since the greater part of the country was under several independent clans until the arrival of Islam in 630 CE.<ref>{{cite book|author=Scott Johnson|title=The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity|page=298|publisher= Oxford University Press|date= 1 November 2012|isbn= 978-0195336931}}</ref> |

||

===Middle Ages=== |

===Middle Ages=== |

||

{{See also|Islamic history of |

{{See also|Islamic history of Semen}} |

||

====Advent of Islam and the three dynasties==== |

====Advent of Islam and the three dynasties==== |

||

{{main|Yufirids|Ziyadid Dynasty|Imams of |

{{main|Yufirids|Ziyadid Dynasty|Imams of Semen}} |

||

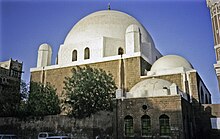

[[File:Great Mosque of Sana'a1.jpg|thumb|The interior of the [[Great Mosque of Sana'a]], the oldest mosque in |

[[File:Great Mosque of Sana'a1.jpg|thumb|The interior of the [[Great Mosque of Sana'a]], the oldest mosque in Semen]] |

||

[[Muhammed]] sent his cousin [[Ali]] to Sana'a and its surroundings around 630 CE. At the time, |

[[Muhammed]] sent his cousin [[Ali]] to Sana'a and its surroundings around 630 CE. At the time, Semen was the most advanced region in Arabia.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sabarr Janneh |title=Learning From the Life of Prophet Muhammad |page=17 |publisher=AuthorHouse |isbn=1467899666}}</ref> The [[Banu Hamdan]] confederation was among the first to accept Islam. Muhammed sent [[Muadh ibn Jabal]], as well to Al-Janad, in present-day [[Taiz]], and dispatched letters to various tribal leaders. The reason behind this was the division among the tribes and the absence of a strong central authority in Semen during the days of the prophet.<ref>Abd al-Muhsin Madʼaj M. Madʼaj ''The Semen in Early Islam (9–233/630–847): A Political History'' p. 12 Ithaca Press, 1988 {{ISBN|0863721028}}</ref> |

||

Major tribes, including Himyar, sent delegations to [[Medina]] during the "year of delegations" around 630–631 CE. Several |

Major tribes, including Himyar, sent delegations to [[Medina]] during the "year of delegations" around 630–631 CE. Several Semenis accepted Islam before the year 630, such as [[Ammar ibn Yasir]], [[Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami]], [[Miqdad ibn Aswad]], [[Abu Musa Ashaari]], and [[Sharhabeel ibn Hasana]]. A man named [[Aswad Ansi|'Abhala ibn Ka'ab Al-Ansi]] expelled the remaining Persians and claimed he was a [[prophet]] of [[Rahman (Islamic term)|Rahman]]. He was assassinated by a Semeni of [[Persian people|Persian]] origin called [[Fayruz al-Daylami]]. Christians, who were mainly staying in [[Najran]] along with Jews, agreed to pay ''[[jizya]]h'' ({{lang-ar|جِـزْيَـة}}), although some Jews converted to Islam, such as [[Wahb ibn Munabbih]] and [[Ka'ab al-Ahbar]]. |

||

Semen was stable during the [[Rashidun|Rashidun Caliphate]]. Semeni tribes played a pivotal role in the Islamic expansion of Egypt, Iraq, Persia, the [[Levant]], [[Anatolia]], [[North Africa]], [[History of Islam in Southern Italy|Sicily]], and [[Andalusia]].<ref>Wilferd Madelung ''The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate'' p. 199 Cambridge University Press, 15 October 1998 {{ISBN|0521646960}}</ref><ref>Ṭabarī ''The History of al-Tabari Vol. 12: The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah and the Conquest of Syria and Palestine A.D. 635–637/A.H. 14–15'' pp. 10–11 SUNY Press, 1992 {{ISBN|0791407330}}</ref><ref>Idris El Hareir ''The Spread of Islam Throughout the World'' p. 380 UNESCO, 2011 {{ISBN|9231041533}}</ref> Semeni tribes who settled in [[Syria]], contributed significantly to the solidification of [[Umayyad Caliphate|Umayyad]] rule, especially during the reign of [[Marwan I]]. Powerful Semenite tribes such as Kindah were on his side during the [[Battle of Marj Rahit (684)|Battle of Marj Rahit]].<ref>Nejla M. Abu Izzeddin ''The Druzes: A New Study of Their History, Faith, and Society'' BRILL, 1993 {{ISBN|9004097058}}</ref><ref>Hugh Kennedy ''The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State'' p. 33 Routledge, 17 June 2013 {{ISBN|1134531133}}</ref> |

|||

Several emirates led by people of |

Several emirates led by people of Semeni descent were established in North Africa and [[Andalusia]]. Effective control over entire Semen was not achieved by the Umayyad Caliphate. [[Imam]] Abdullah ibn Yahya Al-Kindi was elected in 745 CE to lead [[Ibadi|the Ibāḍī movement]] in [[Hadramawt]] and [[Oman]]. He expelled the Umayyad governor from Sana'a and captured [[Mecca]] and Medina in 746.<ref name="autogenerated237">Andrew Rippin ''The Islamic World'' p. 237 Routledge, 23 October 2013 {{ISBN|1136803432}}</ref> Al-Kindi, known by his nickname "Talib al-Haqq" (seeker of truth), established the first [[Ibadi]] state in the history of Islam, but was killed in Taif around 749.<ref name="autogenerated237" /> |

||

Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Ziyad founded the [[Ziyadid dynasty]] in [[Tihama]] around 818 CE. The state stretched from [[Al Qunfudhah|Haly]] (in present-day Saudi Arabia) to Aden. They nominally recognized the [[Abbasid Caliphate]], but were in fact ruling independently from their capital in [[Zabid]].<ref name="autogenerated128">[[Paul Wheatley (geographer)|Paul Wheatley]] ''The Places Where Men Pray Together: Cities in Islamic Lands, Seventh Through the Tenth Centuries'' p. 128 University of Chicago Press, 2001 {{ISBN|0226894282}}</ref> The history of this dynasty is obscure. They never exercised control over the highlands and Hadramawt, and did not control more than a coastal strip of the |

Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Ziyad founded the [[Ziyadid dynasty]] in [[Tihama]] around 818 CE. The state stretched from [[Al Qunfudhah|Haly]] (in present-day Saudi Arabia) to Aden. They nominally recognized the [[Abbasid Caliphate]], but were in fact ruling independently from their capital in [[Zabid]].<ref name="autogenerated128">[[Paul Wheatley (geographer)|Paul Wheatley]] ''The Places Where Men Pray Together: Cities in Islamic Lands, Seventh Through the Tenth Centuries'' p. 128 University of Chicago Press, 2001 {{ISBN|0226894282}}</ref> The history of this dynasty is obscure. They never exercised control over the highlands and Hadramawt, and did not control more than a coastal strip of the Semen (Tihama) bordering the Red Sea.<ref>Kamal Suleiman Salibi ''A History of Arabia'' p. 108 Caravan Books, 1980 OCLC Number: 164797251</ref> A Himyarite clan called the [[Yufirids]] established their rule over the highlands from Saada to Taiz, while Hadramawt was an [[Ibadi]] stronghold and rejected all allegiance to the Abbasids in [[Baghdad]].<ref name="autogenerated128" /> By virtue of its location, the [[Ziyadid dynasty]] of [[Zabid]] developed a special relationship with [[Ethiopia|Abyssinia]]. The chief of the [[Dahlak Archipelago|Dahlak]] islands exported slaves, as well as amber and leopard hides, to the then ruler of Semen.<ref name="Lunpor">{{cite book|last=Paul Lunde|first=Alexandra Porter|title=Trade and travel in the Red Sea Region: proceedings of Red Sea project I held in the British Museum, October 2002|year=2004|publisher=Archaeopress|isbn=1841716227|page=20|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=HSdmAAAAMAAJ|quote=in 976–77 AD[...] the then ruler of Semen received slaves, as well as amber and [[African leopard|leopard]] skins from the chief of the Dahlak islands (off the coast from Massawa).}}</ref> |

||

The first [[Zaidiyyah|Zaidi]] imam, [[Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya|Yahya ibn al-Husayn]], arrived in |

The first [[Zaidiyyah|Zaidi]] imam, [[Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya|Yahya ibn al-Husayn]], arrived in Semen in 893 CE. He was the founder of the [[Rassids|Zaidi imamate]] in 897. He was a religious cleric and judge who was invited to come to Saada from Medina to arbitrate tribal disputes.<ref>Stephen W. Day ''Regionalism and Rebellion in Semen: A Troubled National Union'' p. 31 Cambridge University Press, 2012 {{ISBN|1107022150}}</ref> Imam Yahya persuaded local tribesmen to follow his teachings. The sect slowly spread across the highlands, as the tribes of [[Hashid]] and [[Bakil]], later known as "the twin wings of the imamate," accepted his authority.<ref>Gerhard Lichtenthäler ''Political Ecology and the Role of Water: Environment, Society and Economy in Northern Semen'' p. 55 Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 2003 {{ISBN|0754609081}}</ref> |

||

[[Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya|Yahya]] established his influence in Saada and Najran. He also tried to capture Sana'a from the Yufirids in 901 CE, but failed miserably. In 904, the [[Qarmatians]] invaded Sana'a. The Yufirid emir As'ad ibn Ibrahim retreated to [[Al Jawf Governorate|Al-Jawf]], and between 904 and 913, Sana'a was conquered no less than 20 times by Qarmatians and Yufirids.<ref>First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936 p. 145 BRILL, 1993 {{ISBN|9004097961}}</ref> As'ad ibn Ibrahim regained Sana'a in 915. |

[[Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya|Yahya]] established his influence in Saada and Najran. He also tried to capture Sana'a from the Yufirids in 901 CE, but failed miserably. In 904, the [[Qarmatians]] invaded Sana'a. The Yufirid emir As'ad ibn Ibrahim retreated to [[Al Jawf Governorate|Al-Jawf]], and between 904 and 913, Sana'a was conquered no less than 20 times by Qarmatians and Yufirids.<ref>First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936 p. 145 BRILL, 1993 {{ISBN|9004097961}}</ref> As'ad ibn Ibrahim regained Sana'a in 915. Semen was in turmoil as Sana'a became a battlefield for the three dynasties, as well as independent tribes. |

||

The Yufirid emir Abdullah ibn Qahtan attacked and burned Zabid in 989, severely weakening the [[Ziyadid dynasty]].<ref>E. J. Van Donzel ''Islamic Desk Reference'' p. 492 BRILL, 1994 {{ISBN|9004097384}}</ref> The Ziyadid monarchs lost effective power after 989, or even earlier than that. Meanwhile, a succession of slaves held power in Zabid and continued to govern in the name of their masters, eventually establishing their own [[Najahid dynasty|dynasty]] around 1022 or 1050 according to different sources.<ref>{{cite book |author=Muhammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in |

The Yufirid emir Abdullah ibn Qahtan attacked and burned Zabid in 989, severely weakening the [[Ziyadid dynasty]].<ref>E. J. Van Donzel ''Islamic Desk Reference'' p. 492 BRILL, 1994 {{ISBN|9004097384}}</ref> The Ziyadid monarchs lost effective power after 989, or even earlier than that. Meanwhile, a succession of slaves held power in Zabid and continued to govern in the name of their masters, eventually establishing their own [[Najahid dynasty|dynasty]] around 1022 or 1050 according to different sources.<ref>{{cite book |author=Muhammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=237 |language=Arabic}}</ref> Although they were recognized by the [[Abbasid Caliphate]] in Baghdad, they ruled no more than Zabid and four districts to its north.<ref>{{cite book|author=Henry Cassels Kay|year=1999|title=Yaman its early medieval history|page=14|publisher=Adegi Graphics LLC|isbn=1421264641}}</ref> The rise of the [[Ismailism|Ismaili]] [[Shia]] [[Sulayhid dynasty]] in the Semeni highlands reduced their history to a series of intrigues. |

||

====Sulayhid Dynasty (1047–1138)==== |

====Sulayhid Dynasty (1047–1138)==== |

||

| Line 181: | Line 178: | ||

{{multiple image |align=right |direction=vertical |width= |

{{multiple image |align=right |direction=vertical |width= |

||

|image1=Jibla IMG 5662.JPG |caption1=[[Jibla, |

|image1=Jibla IMG 5662.JPG |caption1=[[Jibla, Semen|Jibla]] became the capital of the dynasty. Featured is the [[Queen Arwa Mosque]]. |

||

|image2=Queen Arwa al- Sulaihi Palace 1.jpg |caption2=[[Palace of Queen Arwa|Queen Arwa al-Sulaihi Palace]] |

|image2=Queen Arwa al- Sulaihi Palace 1.jpg |caption2=[[Palace of Queen Arwa|Queen Arwa al-Sulaihi Palace]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The [[Sulayhid]] dynasty was founded in the northern highlands around 1040; at the time, |

The [[Sulayhid]] dynasty was founded in the northern highlands around 1040; at the time, Semen was ruled by different local dynasties. In 1060, [[Ali al-Sulayhi|Ali ibn Muhammad Al-Sulayhi]] conquered Zabid and killed its ruler Al-Najah, founder of the Najahid dynasty. His sons were forced to flee to [[Dahlak Archipelago|Dahlak]].<ref>J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver ''The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3'' p. 119 Cambridge University Press,1977 {{ISBN|0521209811}}</ref> Hadramawt fell into Sulayhid hands after their capture of Aden in 1162.<ref>{{citation |author=William Charles Brice |title=An Historical Atlas of Islam [cartographic Material] |page=338 |publisher=[[Brill publishers|BRILL]] |year=1981 |isbn=9004061169}}</ref> |

||

By 1063, Ali had subjugated [[Greater |

By 1063, Ali had subjugated [[Greater Semen]].<ref>Farhad Daftary ''Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies: A Historical Introduction to an Islamic Community'' p. 92 I. B. Tauris, 2005 {{ISBN|1845110919}}</ref> He then marched toward [[Hejaz]] and occupied [[Makkah]].<ref>Farhad Daftary ''The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines'' p. 199 Cambridge University Press, 2007 {{ISBN|1139465783}}</ref> Ali was married to [[Asma bint Shihab]], who governed Semen with her husband.<ref name="autogenerated14">Fatima Mernissi ''The Forgotten Queens of Islam'' p. 14 U of Minnesota Press, 1997 {{ISBN|0816624399}}</ref> The [[Khutba]] during [[Jumu'ah|Friday prayers]] was proclaimed in both her husband's name and hers. No other Arab woman had this honor since the advent of Islam.<ref name="autogenerated14"/> |

||

[[Ali al-Sulayhi]] was killed by Najah's sons on his way to Mecca in 1084. His son Ahmed Al-Mukarram led an army to Zabid and killed 8,000 of its inhabitants.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in |

[[Ali al-Sulayhi]] was killed by Najah's sons on his way to Mecca in 1084. His son Ahmed Al-Mukarram led an army to Zabid and killed 8,000 of its inhabitants.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=237 |language=Arabic}}</ref> He later installed the Zurayids to govern Aden. al-Mukarram, who had been afflicted with facial paralysis resulting from war injuries, retired in 1087 and handed over power to his wife [[Arwa al-Sulayhi]].<ref>Farhad Daftary ''Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies: A Historical Introduction to an Islamic Community'' p. 93 I. B. Tauris, 2005 {{ISBN|1845110919}}</ref> Queen Arwa moved the seat of the [[Sulayhid dynasty]] from Sana'a to [[Jibla, Semen|Jibla]], a small town in central Semen near [[Ibb]]. Jibla was strategically near the Sulayhid dynasty source of wealth, the agricultural central highlands. It was also within easy reach of the southern portion of the country, especially Aden. She sent Ismaili missionaries to [[India]], where a significant Ismaili community was formed that exists to this day.<ref name="autogenerated51">Steven C. Caton ''Semen'' p. 51 ABC-CLIO, 2013 {{ISBN|159884928X}}</ref> Queen Arwa continued to rule securely until her death in 1138.<ref name="autogenerated51" /> |

||

Arwa al-Sulayhi is still remembered as a great and much loved sovereign, as attested in |

Arwa al-Sulayhi is still remembered as a great and much loved sovereign, as attested in Semeni historiography, literature, and popular lore, where she is referred to as ''Balqis al-sughra'' ("the junior queen of Sheba").<ref>{{cite book |author=Bonnie G. Smith |title=The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History |trans-title= |year=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0195148909 |volume=4 |page=[https://archive.org/details/oxfordencycloped0000unse_k2h2/page/163 163] |language=Arabic |url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordencycloped0000unse_k2h2/page/163 }}</ref> Although the Sulayhids were Ismaili, they never tried to impose their beliefs on the public.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=414 |language=Arabic}}</ref> Shortly after Queen Arwa's death, the country was split between five competing petty dynasties along religious lines.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=303 |language=Arabic}}</ref> The [[Ayyubid dynasty]] overthrew the [[Fatimid Caliphate]] in Egypt. A few years after their rise to power, [[Saladin]] dispatched his brother [[Turan Shah]] to conquer Semen in 1174.<ref>{{cite book |author=Alexander Mikaberidze |title=Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia: A Historical Encyclopedia |trans-title=|year=2011 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1598843378 |volume= |page=159 }}</ref> |

||

====Ayyubid conquest (1171–1260)==== |

====Ayyubid conquest (1171–1260)==== |

||

{{main|Ayyubid Dynasty}} |

{{main|Ayyubid Dynasty}} |

||

[[Turan Shah]] conquered Zabid from the [[Mahdids]] in May 1174, then marched toward Aden in June and captured it from the Zurayids.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in |

[[Turan Shah]] conquered Zabid from the [[Mahdids]] in May 1174, then marched toward Aden in June and captured it from the Zurayids.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدو المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=311 |language=Arabic}}</ref> The [[Hamdanid sultans]] of Sana'a resisted the Ayyubid in 1175, and the Ayyubids did not manage to definitely secure Sana'a until 1189.<ref name="Farhad Daftary 2007 260">{{cite book |author=Farhad Daftary |title=The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines |trans-title= |year=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1139465786 |volume= |page=260 }}</ref> The Ayyubid rule was stable in southern and central Semen, where they succeeded in eliminating the ministates of that region, while Ismaili and Zaidi tribesmen continued to hold out in a number of fortresses.<ref name="Farhad Daftary 2007 260"/> |

||

The Ayyubids failed to capture the Zaydis stronghold in northern |

The Ayyubids failed to capture the Zaydis stronghold in northern Semen.<ref>{{cite book |author=Josef W. Meri |title=Medieval Islamic Civilization |trans-title= |year=2004 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=0415966906 |volume= |page=871 }}</ref> In 1191, Zaydis of [[Shibam Kawkaban District|Shibam Kawkaban]] rebelled and killed 700 Ayyubid soldiers.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=350 |language=Arabic}}</ref> Imam [[Al-Mansur Abdallah|Abdullah bin Hamza]] proclaimed the imamate in 1197 and fought al-Mu'izz Ismail, the Ayyubid Sultan of Semen. Imam Abdullah was defeated at first, but was able to conquer Sana'a and [[Dhamar, Semen|Dhamar]] in 1198,<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=354 |language=Arabic}}</ref> and al-Mu'izz Ismail was assassinated in 1202.<ref>{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=371 |language=Arabic}}</ref> |

||

[[Al-Mansur Abdallah|Abdullah bin Hamza]] carried on the struggle against the Ayyubid until his death in 1217. After his demise, the Zaidi community was split between two rival imams. The Zaydis were dispersed and a truce was signed with the Ayyubid in 1219.<ref name="Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi 1987 407">{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in |

[[Al-Mansur Abdallah|Abdullah bin Hamza]] carried on the struggle against the Ayyubid until his death in 1217. After his demise, the Zaidi community was split between two rival imams. The Zaydis were dispersed and a truce was signed with the Ayyubid in 1219.<ref name="Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi 1987 407">{{cite book |author=Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi |script-title=ar:الحياة السياسية ومظاهر الحضارة في اليمن في عهد الدول المستقلة |trans-title=political life and aspects of civilization in Semen during the reign of Independent States |year=1987 |publisher=University of Sana'a |isbn= |volume= |page=407 |language=Arabic}}</ref> The Ayyubid army was defeated in [[Dhamar, Semen|Dhamar]] in 1226.<ref name="Mohammed Abdo Al-Sururi 1987 407"/> Ayyubid Sultan Mas'ud Yusuf left for Mecca in 1228, never to return.<ref name="Alexander D. Knysh 1999 230">{{cite book |author=Alexander D. Knysh |title=Ibn 'Arabi in the Later Islamic Tradition: The Making of a Polemical Image in Medieval Islam |trans-title= |year=1999 |publisher=SUNY Press |isbn=1438409427 |volume= |page=230 }}</ref> Other sources suggest that he was forced to leave for [[Egypt]] instead in 1123.<ref name="Abdul Ali 1996 84">{{cite book |author=Abdul Ali |title=Islamic Dynasties of the Arab East: State and Civilization During the Later Medieval Times |trans-title= |year=1996 |publisher=M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd |isbn=8175330082 |volume= |page=84 }}</ref> |

||

====Rasulid Dynasty (1229–1454)==== |

====Rasulid Dynasty (1229–1454)==== |

||

{{main|Rasulid dynasty}} |

{{main|Rasulid dynasty}} |

||

[[File:Cairo Castle GardenTaiz, |

[[File:Cairo Castle GardenTaiz,Semen.jpg|thumb|[[Cairo Castle|Al-Qahyra (Cairo) Castle's]] Garden in Taiz, the capital of Semen during the [[Rasulid dynasty|Rasulid's era]]]] |

||

The [[Rasulid Dynasty]] was established in 1229 by Umar ibn Rasul, who was appointed deputy governor by the Ayyubids in 1223. When the last Ayyubid ruler left |