Christmas: Difference between revisions

Epeefleche (talk | contribs) |

Undid revision 350263701 by Roy Brumback (talk)Just because you mentioned this in discussion doesn't mean conensus was reached. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

'''Christmas'''<ref>[http://www.pch.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/jfa-ha/index-eng.cfm Canadian Heritage – Public holidays] — ''Government of Canada''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> or '''Christmas Day'''<ref>[http://www.opm.gov/Operating_Status_Schedules/fedhol/2009.asp 2009 Federal Holidays] — ''U.S. Office of Personnel Management''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref><ref>[http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/Governmentcitizensandrights/LivingintheUK/DG_073741 Bank holidays and British Summer time] — ''HM Government''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> is a [[holiday (calendar)|holiday]] held on December 25 to commemorate [[Nativity of Jesus|the birth]] of [[Jesus]], the central figure of [[Christianity]].<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/christmas Christmas], ''[[Merriam-Webster]]''. Retrieved October 6, 2008.<br>"[http://encarta.msn.com/encnet/refpages/RefArticle.aspx?refid=761556859 Christmas]," ''[[MSN Encarta]]''. Retrieved October 6, 2008. [http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1257008234358079 Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref><ref name="CathChrit">[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"], ''[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]]'', 1913.</ref> The date is not known to be the actual birth date of Jesus, and may have initially been chosen to correspond with either the day exactly nine months after some early Christians believed [[Annunciation|Jesus had been conceived]],<ref>[http://www.bib-arch.org/e-features/christmas.asp How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13]</ref> the date of the [[winter solstice]] on the ancient Roman calendar,<ref name="Newton">Newton, Isaac, ''[http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16878/16878-h/16878-h.htm Observations on the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John]'' (1733). Ch. XI.<br />A sun connection is possible because Christians consider Jesus to be the "sun of righteousness" prophesied in Malachi 4:2.</ref> or one of various ancient [[winter festivals]].<ref>[http://www.bib-arch.org/e-features/christmas.asp How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13]</ref><ref name="SolInvictus">"[http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761556859_1____4/christmas.html#s4 Christmas]", ''Encarta''<br>Roll, Susan K., ''Toward the Origins of Christmas'', (Peeters Publishers, 1995), p.130.<br>Tighe, William J., "[http://touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=16-10-012-v Calculating Christmas]". [http://www.webcitation.org/5kwR1OTxS Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref> Christmas is central to the [[Christmas and holiday season]], and in Christianity marks the beginning of the larger season of [[Christmastide]], which lasts [[Twelve Days of Christmas|twelve days]].<ref name="CRI-Christmastide">{{cite web|url = http://www.cresourcei.org/cyxmas.html| title = The Christmas Season|publisher = CRI / Voice, Institute|accessdate = 2008-12-25}}</ref> |

'''Christmas'''<ref>[http://www.pch.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/jfa-ha/index-eng.cfm Canadian Heritage – Public holidays] — ''Government of Canada''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> or '''Christmas Day'''<ref>[http://www.opm.gov/Operating_Status_Schedules/fedhol/2009.asp 2009 Federal Holidays] — ''U.S. Office of Personnel Management''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref><ref>[http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/Governmentcitizensandrights/LivingintheUK/DG_073741 Bank holidays and British Summer time] — ''HM Government''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> is a [[holiday (calendar)|holiday]] held on December 25 to commemorate [[Nativity of Jesus|the birth]] of [[Jesus]], the central figure of [[Christianity]].<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/christmas Christmas], ''[[Merriam-Webster]]''. Retrieved October 6, 2008.<br>"[http://encarta.msn.com/encnet/refpages/RefArticle.aspx?refid=761556859 Christmas]," ''[[MSN Encarta]]''. Retrieved October 6, 2008. [http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1257008234358079 Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref><ref name="CathChrit">[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"], ''[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]]'', 1913.</ref> The date is not known to be the actual birth date of Jesus, and may have initially been chosen to correspond with either the day exactly nine months after some early Christians believed [[Annunciation|Jesus had been conceived]],<ref>[http://www.bib-arch.org/e-features/christmas.asp How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13]</ref> the date of the [[winter solstice]] on the ancient Roman calendar,<ref name="Newton">Newton, Isaac, ''[http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16878/16878-h/16878-h.htm Observations on the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John]'' (1733). Ch. XI.<br />A sun connection is possible because Christians consider Jesus to be the "sun of righteousness" prophesied in Malachi 4:2.</ref> or one of various ancient [[winter festivals]].<ref>[http://www.bib-arch.org/e-features/christmas.asp How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13]</ref><ref name="SolInvictus">"[http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761556859_1____4/christmas.html#s4 Christmas]", ''Encarta''<br>Roll, Susan K., ''Toward the Origins of Christmas'', (Peeters Publishers, 1995), p.130.<br>Tighe, William J., "[http://touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=16-10-012-v Calculating Christmas]". [http://www.webcitation.org/5kwR1OTxS Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref> Christmas is central to the [[Christmas and holiday season]], and in Christianity marks the beginning of the larger season of [[Christmastide]], which lasts [[Twelve Days of Christmas|twelve days]].<ref name="CRI-Christmastide">{{cite web|url = http://www.cresourcei.org/cyxmas.html| title = The Christmas Season|publisher = CRI / Voice, Institute|accessdate = 2008-12-25}}</ref> |

||

Although a [[Christianity|Christian]] holiday, Christmas is also widely celebrated by many non-Christians,<ref name="nonXians" /><ref>[http://www.siouxcityjournal.com/lifestyles/leisure/article_9914761e-ce50-11de-98cf-001cc4c03286.html Non-Christians focus on secular side of Christmas] — ''Sioux City Journal''. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> and some of its popular celebratory customs have [[pre-Christian]] or [[secularity|secular]] themes and origins. Popular modern customs of the holiday include gift-giving, [[Christmas music|music]], an exchange of [[Christmas card|greeting cards]], [[Christian Church|church]] celebrations, a special meal, and the display of various decorations; including [[Christmas tree]]s, [[Christmas lights|lights]], [[garland]]s, [[mistletoe]], [[nativity scene]]s, and [[holly]]. In addition, [[Father Christmas]] (known as [[Santa Claus]] in some areas, including [[North America]], [[Australia]] and [[Ireland]]) is a popular [[folklore]] figure in many countries, associated with the bringing of gifts for children.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/16329025 "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures"], Associated Press, December 22, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> |

Although nominally a [[Christianity|Christian]] holiday, Christmas is also widely celebrated by many non-Christians,<ref name="nonXians" /><ref>[http://www.siouxcityjournal.com/lifestyles/leisure/article_9914761e-ce50-11de-98cf-001cc4c03286.html Non-Christians focus on secular side of Christmas] — ''Sioux City Journal''. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> and some of its popular celebratory customs have [[pre-Christian]] or [[secularity|secular]] themes and origins. Popular modern customs of the holiday include gift-giving, [[Christmas music|music]], an exchange of [[Christmas card|greeting cards]], [[Christian Church|church]] celebrations, a special meal, and the display of various decorations; including [[Christmas tree]]s, [[Christmas lights|lights]], [[garland]]s, [[mistletoe]], [[nativity scene]]s, and [[holly]]. In addition, [[Father Christmas]] (known as [[Santa Claus]] in some areas, including [[North America]], [[Australia]] and [[Ireland]]) is a popular [[folklore]] figure in many countries, associated with the bringing of gifts for children.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/16329025 "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures"], Associated Press, December 22, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> |

||

Because [[Gift economy|gift-giving]] and many other aspects of the Christmas festival involve heightened economic activity among both Christians and non-Christians, the holiday has become a significant event and a key sales period for retailers and businesses. The economic impact of Christmas is a factor that has grown steadily over the past few centuries in many regions of the world. |

Because [[Gift economy|gift-giving]] and many other aspects of the Christmas festival involve heightened economic activity among both Christians and non-Christians, the holiday has become a significant event and a key sales period for retailers and businesses. The economic impact of Christmas is a factor that has grown steadily over the past few centuries in many regions of the world. |

||

Revision as of 19:58, 18 March 2010

| Christmas | |

|---|---|

Christmas decorations on display. | |

| Also called | Christ's Mass Nativity Noel |

| Observed by | Christians Many non-Christians[1] |

| Type | Christian, cultural |

| Significance | Traditional birthday of Jesus |

| Observances | Gift giving, church services, family and other social gatherings, symbolic decorating |

| Date | December 25 (or January 7[2] in Eastern Orthodox / Catholic churches) |

| Related to | Annunciation, Advent, Epiphany, Baptism of the Lord |

Christmas[3] or Christmas Day[4][5] is a holiday held on December 25 to commemorate the birth of Jesus, the central figure of Christianity.[6][7] The date is not known to be the actual birth date of Jesus, and may have initially been chosen to correspond with either the day exactly nine months after some early Christians believed Jesus had been conceived,[8] the date of the winter solstice on the ancient Roman calendar,[9] or one of various ancient winter festivals.[10][11] Christmas is central to the Christmas and holiday season, and in Christianity marks the beginning of the larger season of Christmastide, which lasts twelve days.[12]

Although nominally a Christian holiday, Christmas is also widely celebrated by many non-Christians,[1][13] and some of its popular celebratory customs have pre-Christian or secular themes and origins. Popular modern customs of the holiday include gift-giving, music, an exchange of greeting cards, church celebrations, a special meal, and the display of various decorations; including Christmas trees, lights, garlands, mistletoe, nativity scenes, and holly. In addition, Father Christmas (known as Santa Claus in some areas, including North America, Australia and Ireland) is a popular folklore figure in many countries, associated with the bringing of gifts for children.[14]

Because gift-giving and many other aspects of the Christmas festival involve heightened economic activity among both Christians and non-Christians, the holiday has become a significant event and a key sales period for retailers and businesses. The economic impact of Christmas is a factor that has grown steadily over the past few centuries in many regions of the world.

Etymology

The word Christmas originated as a compound meaning "Christ's Mass". It is derived from the Middle English Christemasse and Old English Cristes mæsse, a phrase first recorded in 1038.[7] "Cristes" is from Greek Christos and "mæsse" is from Latin missa (the holy mass). In Greek, the letter Χ (chi), is the first letter of Christ, and it, or the similar Roman letter X, has been used as an abbreviation for Christ since the mid-16th century.[15] Hence, Xmas is sometimes used as an abbreviation for Christmas.

Celebration

Christmas Day is celebrated as a major festival and public holiday in most countries of the world, even in many whose populations are not majority Christian. In some non-Christian countries, periods of former colonial rule introduced the celebration (e.g. Hong Kong); in others, Christian minorities or foreign cultural influences have led populations to observe the holiday. Major exceptions, where Christmas is not a formal public holiday, include People's Republic of China, (except Hong Kong and Macao), Japan, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Thailand, Nepal, Iran, Turkey and North Korea.

Around the world, Christmas celebrations can vary markedly in form, reflecting differing cultural and national traditions. Countries such as Japan and Korea, where Christmas is popular despite there being only a small number of Christians, have adopted many of the secular aspects of Christmas, such as gift-giving, decorations and Christmas trees.

Date of celebration

For many centuries, Christian writers accepted that Christmas was the actual date on which Jesus was born.[16] In the early eighteenth century, scholars began proposing alternative explanations. Isaac Newton argued that the date of Christmas was selected to correspond with the winter solstice,[9] which the Romans called bruma and celebrated on December 25.[17] In 1743, German Protestant Paul Ernst Jablonski argued Christmas was placed on December 25 to correspond with the Roman solar holiday Dies Natalis Solis Invicti and was therefore a "paganization" that debased the true church.[11] According to Judeo-Christian tradition, creation as described in the Genesis creation myth occurred on the date of the spring equinox, i.e. March 25 on the Roman calendar. This date is now celebrated as Annunciation and as the anniversary of Incarnation.[18] In 1889, Louis Duchesne suggested that the date of Christmas was calculated as nine months after Annunciation, the traditional date of the conception of Jesus.[19]

The December 25 date may have been selected by the church in Rome in the early fourth century. At this time, a church calendar was created and other holidays were also placed on solar dates: "It is cosmic symbolism...which inspired the Church leadership in Rome to elect the winter solstice, December 25, as the birthday of Christ, and the summer solstice as that of John the Baptist, supplemented by the equinoxes as their respective dates of conception. While they were aware that pagans called this day the 'birthday' of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any role in their choice of date for Christmas," according to modern scholar S.E. Hijmans.[20]

Orthodox churches

Some Eastern Orthodox national churches, including those of Russia, Georgia, Egypt, Ukraine, the Macedonia, Serbia and the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem mark feasts using the older Julian Calendar. December 25 on that calendar currently corresponds to January 7 on the more widely used Gregorian calendar. Oriental Orthodox churches also use their own calendars, which are generally similar to the Julian calendar. The Armenian Apostolic Church in Armenia celebrates the nativity in combination with the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6 in that church's calendar (currently corresponding to January 19 in the Gregorian calendar).

Commemorating the birth of Jesus

In Christianity, Christmas is the festival celebrating the Nativity of Jesus, the Christian belief that the Messiah foretold in the Old Testament's Messianic prophecies was born to the Virgin Mary. The story of Christmas is based on the biblical accounts given in the Gospel of Matthew, namely Matthew 1:18, and the Gospel of Luke, specifically Luke 1:26 and 2:40. According to these accounts, Jesus was born to Mary, assisted by her husband Joseph, in the city of Bethlehem. According to popular tradition, the birth took place in a stable, surrounded by farm animals, though neither the stable nor the animals are specifically mentioned in the Biblical accounts. However, a manger is mentioned in Luke 2:7, where it states, "She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn." Early iconographic representations of the nativity placed the animals and manger within a cave (located, according to tradition, under the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem). Shepherds from the fields surrounding Bethlehem were told of the birth by an angel, and were the first to see the child.[21]

Many Christians believe that the birth of Jesus fulfilled messianic prophecies from the Old Testament.[22] The Gospel of Matthew also describes a visit by several Magi, or astrologers, who bring gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to the infant. The visitors were said to be following a mysterious star, commonly known as the Star of Bethlehem, believing it to announce the birth of a king of the Jews.[23] The commemoration of this visit, the Feast of Epiphany celebrated on January 6, is the formal end of the Christmas season in some churches.

Christians celebrate Christmas in many ways. In addition to this day being one of the most important and popular for the attendance of church services, there are numerous other devotions and popular traditions. Prior to Christmas Day, the Eastern Orthodox Church practises the 40-day Nativity Fast in anticipation of the birth of Jesus, while much of Western Christianity celebrates four weeks of Advent. The final preparations for Christmas are made on Christmas Eve.

Over the Christmas period, people decorate their homes and exchange gifts. In some Christian denominations, children perform plays re-telling the events of the Nativity, or sing carols that reference the event. Some Christians also display a small re-creation of the Nativity, known as a Nativity scene or crib, in their homes, using figurines to portray the key characters of the event. Live Nativity scenes and tableaux vivants are also performed, using actors and animals to portray the event with more realism.[24]

A long artistic tradition has grown of producing painted depictions of the nativity in art. Nativity scenes are traditionally set in a barn or stable and include Mary, Joseph, the child Jesus, angels, shepherds and the Three Wise Men: Balthazar, Melchior, and Caspar, who are said to have followed a star, known as the Star of Bethlehem, and arrived after his birth.[25]

Varied traditions

Among countries with a strong Christian tradition, a variety of Christmas celebrations have developed that incorporate regional and local cultures. For many Christians, participating in a religious service plays an important part in the recognition of the season. Christmas, along with Easter, is the period of highest annual church attendance.

In many Catholic countries, the people hold religious processions or parades in the days preceding Christmas. In other countries, secular processions or parades featuring Santa Claus and other seasonal figures are often held. Family reunions and the exchange of gifts are a widespread feature of the season. Gift giving takes place on Christmas Day in most countries. Others practise gift giving on December 6, Saint Nicholas Day, and January 6, Epiphany.

A special Christmas family meal is an important part of the celebration for many, and what is served varies greatly from country to country. Some regions, such as Sicily, have special meals for Christmas Eve, when 12 kinds of fish are served. In England and countries influenced by its traditions, a standard Christmas meal includes turkey (brought from North America), potatoes, vegetables, sausages and gravy, followed by Christmas pudding, mince pies and fruit cake. In Poland and other parts of eastern Europe and Scandinavia, fish often is used for the traditional main course, but richer meat such as lamb is increasingly served. In Germany, France and Austria, goose and pork are favored. Beef, ham and chicken in various recipes are popular throughout the world. Ham is the main meal in the Philippines.

Special desserts are also prepared: The Maltese traditionally serve Imbuljuta tal-Qastan,[26] a chocolate and chestnuts beverage, after Midnight Mass and throughout the Christmas season. Slovaks prepare the traditional Christmas bread potica, bûche de Noël in France, panettone in Italy, and elaborate tarts and cakes. The eating of sweets and chocolates has become popular worldwide, and sweeter Christmas delicacies include the German stollen, marzipan cake or candy, and Jamaican rum fruit cake. As one of the few fruits traditionally available to northern countries in winter, oranges were long associated with special Christmas foods.

Decorations

The practice of putting up special decorations at Christmas has a long history. From pre-Christian times, people in the Roman Empire brought branches from evergreen plants indoors in the winter. Christian people incorporated such customs in their developing practices. In the fifteenth century, it was recorded that in London it was the custom at Christmas for every house and all the parish churches to be "decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green".[27] The heart-shaped leaves of ivy were said to symbolise the coming to earth of Jesus, while holly was seen as protection against pagans and witches, its thorns and red berries held to represent the Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus at the crucifixion and the blood he shed.[28]

Nativity scenes are known from 10th-century Rome. They were popularised by Saint Francis of Asissi from 1223, quickly spreading across Europe.[29] Many different types of decorations developed across the Christian world, dependent on local tradition and available resources. The first commercially produced decorations appeared in Germany in the 1860s, inspired by paper chains made by children.[30]

The Christmas tree is often explained as a Christianisation of pagan tradition and ritual surrounding the Winter Solstice, which included the use of evergreen boughs, and an adaptation of pagan tree worship.[31] The English language phrase "Christmas tree" is first recorded in 1835[32] and represents an importation from the German language. The modern Christmas tree tradition is believed to have begun in Germany in the 18th century[31] though many argue that Martin Luther began the tradition in the 16th century.[33][34] From Germany the custom was introduced to Britain, first via Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and then more successfully by Prince Albert during the reign of Queen Victoria. By 1841 the Christmas tree had become even more widespread throughout Britain.[35] By the 1870s, people in the United States had adopted the custom of putting up a Christmas tree.[36] Christmas trees may be decorated with lights and ornaments.

Since the 19th century, the poinsettia, a native plant from Mexico, has been associated with Christmas. Other popular holiday plants include holly, mistletoe, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus. Along with a Christmas tree, the interior of a home may be decorated with these plants, along with garlands and evergreen foliage.

In Australia, North and South America, and Europe, it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures. Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well. Christmas banners may be hung from street lights and Christmas trees placed in the town square.[37]

In the Western world, rolls of brightly colored paper with secular or religious Christmas motifs are manufactured for the purpose of wrapping gifts. The display of Christmas villages has also become a tradition in many homes during this season. Other traditional decorations include bells, candles, candy canes, stockings, wreaths, and angels.

In many countries a representation of the Nativity Scene is very popular, and people are encouraged to compete and create most original or realistic ones. Within some families, the pieces used to make the representation are considered a valuable family heirloom. Christmas decorations are traditionally taken down on Twelfth Night, the evening of January 5. The traditional colors of Christmas are pine green (evergreen), snow white, and heart red.

Music and carols

The first specifically Christmas hymns that we know of appear in fourth century Rome. Latin hymns such as Veni redemptor gentium, written by Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan, were austere statements of the theological doctrine of the Incarnation in opposition to Arianism. Corde natus ex Parentis (Of the Father's love begotten) by the Spanish poet Prudentius (d. 413) is still sung in some churches today.[38]

In the ninth and tenth centuries, the Christmas "Sequence" or "Prose" was introduced in North European monasteries, developing under Bernard of Clairvaux into a sequence of rhymed stanzas. In the twelfth century the Parisian monk Adam of St. Victor began to derive music from popular songs, introducing something closer to the traditional Christmas carol.

By the thirteenth century, in France, Germany, and particularly, Italy, under the influence of Francis of Asissi, a strong tradition of popular Christmas songs in the native language developed.[39] Christmas carols in English first appear in a 1426 work of John Awdlay, a Shropshire chaplain, who lists twenty-five "caroles of Cristemas", probably sung by groups of wassailers, who went from house to house.[40] The songs we know specifically as carols were originally communal folk songs sung during celebrations such as "harvest tide" as well as Christmas. It was only later that carols began to be sung in church. Traditionally, carols have often been based on medieval chord patterns, and it is this that gives them their uniquely characteristic musical sound. Some carols like "Personent hodie", "Good King Wenceslas", and "The Holly and the Ivy" can be traced directly back to the Middle Ages. They are among the oldest musical compositions still regularly sung. Adeste Fidelis (O Come all ye faithful) appears in its current form in the mid 18th century, although the words may have originated in the thirteenth century.

Singing of carols initially suffered a decline in popularity after the Protestant Reformation in northern Europe, although some Reformers, like Martin Luther, wrote carols and encouraged their use in worship. Carols largely survived in rural communities until the revival of interest in popular songs in the 19th century. The 18th century English reformer Charles Wesley understood the importance of music to worship. In addition to setting many psalms to melodies, which were influential in the Great Awakening in the United States, he wrote texts for at least three Christmas carols. The best known was originally entitled "Hark! How All the Welkin Rings", later renamed "Hark! the Herald Angels Sing".[41] Felix Mendelssohn wrote a melody adapted to fit Wesley's words. In Austria in 1818 Mohr and Gruber made a major addition to the genre when they composed "Silent Night" for the St. Nicholas Church, Oberndorf. William B. Sandys' Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833) contained the first appearance in print of many now-classic English carols, and contributed to the mid-Victorian revival of the festival.[42]

Completely secular Christmas seasonal songs emerged in the late eighteenth century. "Deck The Halls" dates from 1784, and the American, "Jingle Bells" was copyrighted in 1857. In the 19th and 20th century, African American spirituals and songs about Christmas, based in their tradition of spirituals, became more widely known. An increasing number of seasonal holidays songs were commercially produced in the twentieth century, including jazz and blues variations. In addition, there was a revival of interest in early music, from groups singing folk music, such as The Revels, to performers of early medieval and classical music.

Cards

Christmas cards are illustrated messages of greeting usually exchanged between friends and family members during the weeks preceding Christmas Day. The custom has become popular among a wide cross-section of people, including non-Christians, in Western society and in Asia. The traditional greeting reads "wishing you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year", much like that of the first commercial Christmas card, produced by Sir Henry Cole in London in 1843. However there are innumerable variations of this formula, many cards expressing a more religious sentiment, or containing a poem, prayer or Biblical verse; while others distance themselves from religion with an all-inclusive "Season's greetings".

Christmas cards are purchased in considerable quantities, and feature artwork, commercially designed and relevant to the season. The content of the design might relate directly to the Christmas narrative with depictions of the Nativity of Jesus, or Christian symbols such as the Star of Bethlehem, or a white dove which can represent both the Holy Spirit and Peace on Earth. Other Christmas cards are more secular and can depict Christmas traditions, mythical figures such as Santa Claus, objects directly associated with Christmas such as candles, holly and baubles, or a variety of images associated with the season, such as Christmastime activities, snow scenes and the wildlife of the northern winter. There are also humorous cards and genres depicting nostalgic scenes of the past such as crinolined shoppers in idealized 19th century streetscapes.

Stamps

A number of nations have issued commemorative stamps at Christmastime. Postal customers will often use these stamps to mail Christmas cards, and they are popular with philatelists. These stamps are regular postage stamps, unlike Christmas seals, and are valid for postage year-round. They usually go on sale some time between early October and early December, and are printed in considerable quantities.

In 1898 a Canadian stamp was issued to mark the inauguration of the Imperial Penny Postage rate. The stamp features a map of the globe and bears an inscription "XMAS 1898" at the bottom. In 1937, Austria issued two "Christmas greeting stamps" featuring a rose and the signs of the zodiac. In 1939, Brazil issued four semi-postal stamps with designs featuring the three kings and a star of Bethlehem, an angel and child, the Southern Cross and a child, and a mother and child.

Both the US Postal Service and the Royal Mail regularly issue Christmas-themed stamps each year.

Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts

Christmas has for many centuries been a time for the giving and exchanging of gifts, particularly between friends and family members. A number of figures of both Christian and mythical origin have been associated with Christmas and the seasonal giving of gifts. Among these are Father Christmas, also known as Santa Claus, Père Noël, and the Weihnachtsmann; Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas; the Christkind; Kris Kringle; Joulupukki; Babbo Natale; Saint Basil; and Father Frost.

The most famous and pervasive of these figures in modern celebration worldwide is Santa Claus, a mythical gift bringer, dressed in red, whose origins have diverse sources. The name Santa Claus is a corruption of the Dutch Sinterklaas, which means simply Saint Nicholas. Nicholas was Bishop of Myra, in modern day Turkey, during the fourth century. Among other saintly attributes, he was noted for the care of Children, generosity, and the giving of gifts. His feast on the 6th of December came to be celebrated in many countries with the giving of gifts. Saint Nicholas traditionally appeared in bishoply attire, accompanied by helpers, and enquired about the behaviour of children during the past year before deciding whether they deserved a gift or not. By the 13th century Saint Nicholas was well known in the Netherlands, and the practice of gift-giving in his name spread to other parts of central and southern Europe. At the Reformation in 16th–17th century Europe, many Protestants changed the gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl, corrupted in English to Kris Kringle, and the date of giving gifts changed from December the 6th to Christmas Eve.[43]

The modern popular image of Santa Claus, however, was created in the United States, and in particular in New York. The transformation was accomplished with the aid of six notable contributors including Washington Irving and the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840–1902). Following the American Revolutionary War, some of the inhabitants of New York City sought out symbols of the city's non-English past. New York had originally been established as the Dutch colonial town of New Amsterdam and the Dutch Sinterklaas tradition was reinvented as Saint Nicholas.[44] In 1809, the New-York Historical Society convened and retroactively named Sancte Claus the patron saint of Nieuw Amsterdam, the Dutch name for New York City.[45] At his first American appearance in 1810, Santa Claus was drawn in bishops' robes. However as new artists took over, Santa Claus developed more secular attire.[46] Nast drew a new image of "Santa Claus" annually, beginning in 1863. By the 1880s, Nast's Santa had evolved into the robed, fur clad, form we now recognize, perhaps based on the English figure of Father Christmas. The image was standardized by advertisers in the 1920s.[47]

Father Christmas, a jolly, well nourished, bearded man who typified the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, predates the Santa Claus character. He is first recorded in early 17th century England, but was associated with holiday merrymaking and drunkenness rather than the bringing of gifts.[32] In Victorian Britain, his image was remade to match that of Santa. The French Père Noël evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image. In Italy, Babbo Natale acts as Santa Claus, while La Befana is the bringer of gifts and arrives on the eve of the Epiphany. It is said that La Befana set out to bring the baby Jesus gifts, but got lost along the way. Now, she brings gifts to all children. In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht, or Black Peter. In other versions, elves make the toys. His wife is referred to as Mrs. Claus.

There has been some opposition to the narrative of the American evolution of Saint Nicholas into the modern Santa. It has been claimed that the Saint Nicholas Society was not founded until 1835, almost half a century after the end of the American War of Independence.[48] Moreover, a study of the "children's books, periodicals and journals" of New Amsterdam by Charles Jones revealed no references to Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas.[49] However, not all scholars agree with Jones's findings, which he reiterated in a booklength study in 1978;[50] Howard G. Hageman, of New Brunswick Theological Seminary, maintains that the tradition of celebrating Sinterklaas in New York was alive and well from the early settlement of the Hudson Valley on.[51]

Current tradition in several Latin American countries (such as Venezuela and Colombia) holds that while Santa makes the toys, he then gives them to the Baby Jesus, who is the one who actually delivers them to the children's homes, a reconciliation between traditional religious beliefs and the iconography of Santa Claus imported from the United States.

In Alto Adige/Südtirol (Italy), Austria, Czech Republic, Southern Germany, Hungary, Liechtenstein, Slovakia and Switzerland, the Christkind (Ježíšek in Czech, Jézuska in Hungarian and Ježiško in Slovak) brings the presents. The German St. Nikolaus is not identical with the Weihnachtsman (who is the German version of Santa Claus). St. Nikolaus wears a bishop's dress and still brings small gifts (usually candies, nuts and fruits) on December 6 and is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht. Although many parents around the world routinely teach their children about Santa Claus and other gift bringers, some have come to reject this practice, considering it deceptive.[52]

History

Pre-Christian background

Dies Natalis Solis Invicti

Dies Natalis Solis Invicti means "the birthday of the unconquered Sun." The use of the title Sol Invictus allowed several solar deities to be worshipped collectively, including Elah-Gabal, a Syrian sun god; Sol, the god of Emperor Aurelian; and Mithras, a soldiers' god of Persian origin.[54] Emperor Elagabalus (218–222) introduced Sol-worship and the cult reached the height of its popularity under Aurelian.[55]

Modern scholars have argued that the festival was placed on the date of the solstice because this was on this day that the Sun reversed its southward retreat and proved itself to be "unconquered." Several early Christian writers connected the rebirth of the sun to the birth of Jesus.[7] "O, how wonderfully acted Providence that on that day on which that Sun was born...Christ should be born", Cyprian wrote.[7] John Chrysostom also commented on the connection: "They call it the 'Birthday of the Unconquered'. Who indeed is so unconquered as Our Lord . . .?"[7]

Although Dies Natalis Solis Invicti has been the subject of a great deal of scholarly speculation, the only ancient source for it is a single mention in the Chronography of 354.[20] "[W]hile the winter solstice on or around the 25th of December was well established in the Roman imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on that day antedated the celebration of Christmas, and none that indicates that Aurelian had a hand in its institution," according to modern Sol scholar Steven Hijmans.[20]

Winter festivals

A winter festival was the most popular festival of the year in many cultures. Reasons included the fact that less agricultural work needs to be done during the winter, as well as an expectation of better weather as spring approached.[56] Modern Christmas customs include: gift-giving and merrymaking from Roman Saturnalia; greenery, lights, and charity from the Roman New Year; and Yule logs and various foods from Germanic feasts.[57] Pagan Scandinavia celebrated a winter festival called Yule, held in the late December to early January period. As Northern Europe was the last part to Christianize, its pagan traditions had a major influence on Christmas. Scandinavians still call Christmas Jul. In English, the word Yule is synonymous with Christmas,[58] a usage first recorded in 900.

Christian feast

The New Testament does not give a date for the birth of Jesus.[7][59] Around AD 200, Clement of Alexandria wrote that a group in Egypt celebrated the nativity on 25 Pashons.[7] This corresponds to May 20.[60] Tertullian (d. 220) does not mention Christmas as a major feast day in the Church of Roman Africa.[7] However, in Chronographai, a reference work published in 221, Sextus Julius Africanus suggested that Jesus was conceived on the spring equinox, popularizing the idea that Christ was born on December 25.[61][62] The equinox was March 25 on the Roman calendar, so this implied a birth in December.[63] De Pascha Computus, a calendar of feasts produced in 243, gives March 28 as the date of the nativity.[64] In 245, the theologian Origen of Alexandria stated that, "only sinners (like Pharaoh and Herod)" celebrated their birthdays.[65] In 303, Christian writer Arnobius ridiculed the idea of celebrating the birthdays of gods, which suggests that Christmas was not yet a feast at this time.[7]

Feast established

The earliest known reference to the date of the nativity as December 25 is found in the Chronography of 354, an illuminated manuscript compiled in Rome.[66] In the East, early Christians celebrated the birth of Christ as part of Epiphany (January 6), although this festival emphasized celebration of the baptism of Jesus.[67]

Christmas was promoted in the Christian East as part of the revival of Catholicism following the death of the pro-Arian Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The feast was introduced to Constantinople in 379, and to Antioch in about 380. The feast disappeared after Gregory of Nazianzus resigned as bishop in 381, although it was reintroduced by John Chrysostom in about 400.[7]

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, Christmas Day was overshadowed by Epiphany, which in the west focused on the visit of the magi. But the Medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas-related holidays. The forty days before Christmas became the "forty days of St. Martin" (which began on November 11, the feast of St. Martin of Tours), now known as Advent.[68] In Italy, former Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent.[68] Around the 12th century, these traditions transferred again to the Twelve Days of Christmas (December 25 – January 5); a time that appears in the liturgical calendars as Christmastide or Twelve Holy Days.[68]

The prominence of Christmas Day increased gradually after Charlemagne was crowned Emperor on Christmas Day in 800. King Edmund the Martyr was anointed on Christmas in 855 and King William I of England was crowned on Christmas Day 1066.

By the High Middle Ages, the holiday had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various magnates celebrated Christmas. King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten.[68] The Yule boar was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts. Caroling also became popular, and was originally a group of dancers who sang. The group was composed of a lead singer and a ring of dancers that provided the chorus. Various writers of the time condemned caroling as lewd, indicating that the unruly traditions of Saturnalia and Yule may have continued in this form.[68] "Misrule"—drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling—was also an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchanged on New Year's Day, and there was special Christmas ale.[68]

Christmas during the Middle Ages was a public festival that incorporated ivy, holly, and other evergreens.[69] Christmas gift-giving during the Middle Ages was usually between people with legal relationships, such as tenant and landlord.[69] The annual indulgence in eating, dancing, singing, sporting, card playing escalated in England, and by the 17th century the Christmas season featured lavish dinners, elaborate masques and pageants. In 1607, King James I insisted that a play be acted on Christmas night and that the court indulge in games.[70] It was during the Reformation in 16th–17th century Europe, that many Protestants changed the gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl, and the date of giving gifts changed from December 6th to Christmas Eve.[43]

Reformation into the 19th century

Following the Protestant Reformation, groups such as the Puritans strongly condemned the celebration of Christmas, considering it a Catholic invention and the "trappings of popery" or the "rags of the Beast."[71] The Catholic Church responded by promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. King Charles I of England directed his noblemen and gentry to return to their landed estates in midwinter to keep up their old style Christmas generosity.[70] Following the Parliamentarian victory over Charles I during the English Civil War, England's Puritan rulers banned Christmas in 1647.[71] Protests followed as pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans.[71] The book, The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652), argued against the Puritans, and makes note of Old English Christmas traditions, dinner, roast apples on the fire, card playing, dances with "plow-boys" and "maidservants", and carol singing.[72] The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 ended the ban, but many clergymen still disapproved of Christmas celebration. In Scotland, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland also discouraged observance of Christmas. James VI commanded its celebration in 1618, however attendance at church was scant.[73]

In Colonial America, the Puritans of New England shared radical Protestant disapproval of Christmas. Celebration was outlawed in Boston from 1659 to 1681. The ban by the Pilgrims was revoked in 1681 by English governor Sir Edmund Andros, however it wasn't until the mid 1800's that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region.[74] At the same time, Christian residents of Virginia and New York observed the holiday freely. Pennsylvania German Settlers, pre-eminently the Moravian settlers of Bethlehem, Nazareth and Lititz in Pennsylvania and the Wachovia Settlements in North Carolina, were enthusiastic celebrators of Christmas. The Moravians in Bethlehem had the first Christmas trees in America as well as the first Nativity Scenes.[75] Christmas fell out of favor in the United States after the American Revolution, when it was considered an English custom.[76] George Washington attacked Hessian (German) mercenaries on Christmas during the Battle of Trenton in 1777, Christmas being much more popular in Germany than in America at this time.

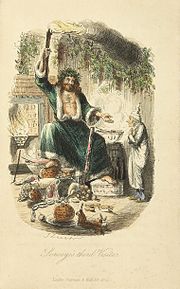

By the 1820s, sectarian tension had eased in Britain and writers, including William Winstanly, began to worry that Christmas was dying out. These writers imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration, and efforts were made to revive the holiday. In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol, that helped revive the 'spirit' of Christmas and seasonal merriment.[77][78] Its instant popularity played a major role in portraying Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion.[79] Dickens sought to construct Christmas as a family-centered festival of generosity, in contrast to the community-based and church-centered observations, the observance of which had dwindled during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[80] Superimposing his secular vision of the holiday, Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit.[81] A prominent phrase from the tale, 'Merry Christmas', was popularized following the appearance of the story.[82] The term Scrooge became a synonym for miser, with 'Bah! Humbug!' dismissive of the festive spirit.[83] In 1843, the first commercial Christmas card was produced by Sir Henry Cole.[84] The revival of the Christmas Carol began with William B. Sandys Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833), with the first appearance in print of 'The First Noel', 'I Saw Three Ships', 'Hark the Herald Angels Sing' and 'God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen', popularized in Dickens' A Christmas Carol.

In Britain, the Christmas tree was introduced in the early 1800s following the personal union with the Kingdom of Hanover, by Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen to King George III. In 1832 a young Queen Victoria wrote about her delight at having a Christmas tree, hung with lights, ornaments, and presents placed round it.[85] After her marriage to her German cousin Prince Albert, by 1841 the custom became more widespread throughout Britain.[35] An image of the British royal family with their Christmas tree at Windsor Castle, created a sensation when it was published in the Illustrated London News in 1848. A modified version of this image was published in the United States in 1850.[86][36] By the 1870s, putting up a Christmas tree had become common in America.[36]

In America, interest in Christmas had been revived in the 1820s by several short stories by Washington Irving which appear in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon and "Old Christmas". Irving's stories depicted some harmonious warm-hearted holiday traditions he claimed to have observed in England,[87] and he used the tract Vindication of Christmas (1652) of Old English Christmas traditions long since abandoned, that he had transcribed into his journal as a format for his stories.[70] In 1822, Clement Clarke Moore wrote the poem A Visit From St. Nicholas (popularly known by its first line: Twas the Night Before Christmas).[88] The poem helped popularize the tradition of exchanging gifts, and seasonal Christmas shopping began to assume economic importance.[89] This also started the cultural conflict of the holiday's spiritualism and its commercialism that some see as corrupting the holiday. In her 1850 book "The First Christmas in New England", Harriet Beecher Stowe includes a character who complains that the true meaning of Christmas was lost in a shopping spree.[90] While the celebration of Christmas wasn't yet customary in some regions in the U.S., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow detected "a transition state about Christmas here in New England" in 1856. "The old puritan feeling prevents it from being a cheerful, hearty holiday; though every year makes it more so".[91] In Reading, Pennsylvania, a newspaper remarked in 1861, "Even our presbyterian friends who have hitherto steadfastly ignored Christmas — threw open their church doors and assembled in force to celebrate the anniversary of the Savior's birth".[91] The First Congregational Church of Rockford, Illinois, 'although of genuine Puritan stock', was 'preparing for a grand Christmas jubilee', a news correspondent reported in 1864.[91] By 1860, fourteen states including several from New England had adopted Christmas as a legal holiday.[92] In 1870, Christmas was formally declared a United States Federal holiday, signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant.[92] Subsequently, in 1875, Louis Prang introduced the Christmas card to Americans. He has been called the "father of the American Christmas card".[93]

Controversy and criticism

Throughout the holiday's history, Christmas has been the subject of both controversy and criticism from a wide variety of different sources. The first documented Christmas controversy was Christian-led, and began during the English Interregnum, when England was ruled by a Puritan Parliament.[94] Puritans (including those who fled to America) sought to remove the remaining pagan elements of Christmas. During this period, the English Parliament banned the celebration of Christmas entirely, considering it "a popish festival with no biblical justification", and a time of wasteful and immoral behavior.[95]

Controversy and criticism continues in the present-day, where some Christian and non-Christians have claimed that an affront to Christmas (dubbed a "war on Christmas" by some) is ongoing.[96][97] In the United States there has been a tendency to replace the greeting Merry Christmas with Happy Holidays.[98] Groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union have initiated court cases to bar the display of images and other material referring to Christmas from public property, including schools.[99] Such groups argue that government-funded displays of Christmas imagery and traditions violate the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits the establishment by Congress of a national religion.[100] In 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Lynch vs. Donnelly that a Christmas display (which included a Nativity scene) owned and displayed by the city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island did not violate the First Amendment.[101] In November 2009, the Federal appeals court in Philadelphia endorsed a school district's ban on the singing of Christmas carols.[102]

In the private sphere also, it has been alleged that any specific mention of the term "Christmas" or its religious aspects was being increasingly censored, avoided, or discouraged by a number of advertisers and retailers. In response, the American Family Association and other groups have organized boycotts of individual retailers.."[103] In the United Kingdom there have also been some controversies, one of the most famous being the temporary promotion of the Christmas period as Winterval by Birmingham City Council in 1998. There were also protests in November 2009 when the city of Dundee promoted its celebrations as the Winter Night Light festival, initially with no specific Christmas references.[104]

Economics

Christmas is typically the largest annual economic stimulus for many nations around the world. Sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas and shops introduce new products as people purchase gifts, decorations, and supplies. In the U.S., the "Christmas shopping season" generally begins on the day after Thanksgiving (often referred to as Black Friday), though many American stores begin selling Christmas items as early as October.[105] In Canada, merchants begin advertising campaigns just before Halloween (October 31), and step up their marketing following Remembrance Day on November 11. In the United States, it has been calculated that a quarter of all personal spending takes place during the Christmas/holiday shopping season.[106] Figures from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that expenditure in department stores nationwide rose from $20.8 billion in November 2004 to $31.9 billion in December 2004, an increase of 54 percent. In other sectors, the pre-Christmas increase in spending was even greater, there being a November – December buying surge of 100 percent in bookstores and 170 percent in jewelry stores. In the same year employment in American retail stores rose from 1.6 million to 1.8 million in the two months leading up to Christmas.[107] Industries completely dependent on Christmas include Christmas cards, of which 1.9 billion are sent in the United States each year, and live Christmas Trees, of which 20.8 million were cut in the USA in 2002.[108]

In most Western nations, Christmas Day is the least active day of the year for business and commerce; almost all retail, commercial and institutional businesses are closed, and almost all industries cease activity (more than any other day of the year). In England and Wales, the Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004 prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day. Scotland is currently planning similar legislation. Film studios release many high-budget movies during the holiday season, including Christmas films, fantasy movies or high-tone dramas with high production values.

One economist's analysis calculates that, despite increased overall spending, Christmas is a deadweight loss under orthodox microeconomic theory, because of the effect of gift-giving. This loss is calculated as the difference between what the gift giver spent on the item and what the gift receiver would have paid for the item. It is estimated that in 2001, Christmas resulted in a $4 billion deadweight loss in the U.S. alone.[109][110] Because of complicating factors, this analysis is sometimes used to discuss possible flaws in current microeconomic theory. Other deadweight losses include the effects of Christmas on the environment and the fact that material gifts are often perceived as white elephants, imposing cost for upkeep and storage and contributing to clutter.[111]

See also

|

|

References

Notes

- ^ a b Christmas as a Multi-faith Festival—BBC News. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Christmas: January 7 or December 25? — Coptic Orthodox Church Network. John Ramzy. Retrieved on December 31, 2009.

- ^ Canadian Heritage – Public holidays — Government of Canada. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ 2009 Federal Holidays — U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ Bank holidays and British Summer time — HM Government. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ Christmas, Merriam-Webster. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

"Christmas," MSN Encarta. Retrieved October 6, 2008. Archived 2009-10-31. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Christmas", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913.

- ^ How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13

- ^ a b Newton, Isaac, Observations on the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733). Ch. XI.

A sun connection is possible because Christians consider Jesus to be the "sun of righteousness" prophesied in Malachi 4:2. - ^ How December 25 Became Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Review, Retrieved 2009-12-13

- ^ a b "Christmas", Encarta

Roll, Susan K., Toward the Origins of Christmas, (Peeters Publishers, 1995), p.130.

Tighe, William J., "Calculating Christmas". Archived 2009-10-31. - ^ "The Christmas Season". CRI / Voice, Institute. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ^ Non-Christians focus on secular side of Christmas — Sioux City Journal. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures", Associated Press, December 22, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ For example, Pope Benedict XIV argued in 1761 that the church fathers would have known the correct date of birth from Roman census records. (Roll, Susan K., Toward the Origins of Christmas, (Peeters Publishers, 1995), p. 129.)

- ^ "Bruma", Seasonal Festivals of the Greeks and Romans

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 18:59 - ^ "Choosing the Date of Christmas: Why is Christmas Celebrated on December 25?". Ancient and Future Catholics. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- ^ Roll, pp. 88–90.

Duchesne, Louis, Les Origines du Culte Chrétien, Paris, 1902, 262 ff. - ^ a b c S.E. Hijmans, Sol, the sun in the art and religions of Rome, 2009, pp. 587–588.

- ^ Luke 2:1–6

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, London, Penguin, 2006, p22.; E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1993, p.85.

- ^ Matthew 2:2.

- ^ Krug, Nora. "Little Towns of Bethlehem", The New York Times, November 25, 2005.

- ^ Matthew 2:1–11

- ^ http://schoolnet.gov.mt/HelloEurope/activities/recepies/imbuljuta.html Imbuljuta

- ^ Miles, Clement A, Christmas customs and traditions, Courier Dover Publications, 1976, ISBN 0486233545, p. 272

- ^ Heller, Ruth, Christmas: Its Carols, Customs & Legends, Alfred Publishing (1985), ISBN 0769243991, p. 12

- ^ Collins, Ace, Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas, Zondervan, (2003), ISBN 0310248809 p.47

- ^ Collins p. 83

- ^ a b van Renterghem, Tony. When Santa was a shaman. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-56718-765-X

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas, Christ, Online Etymology Dictionary, 2001.

- ^ "The Chronological History of the Christmas Tree". The Christmas Archives. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ "Christmas Tradition – The Christmas Tree Custom". Fashion Era. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ a b Lejeune, Marie Claire. Compendium of symbolic and ritual plants in Europe, p.550. University of Michigan ISBN 9077135049

- ^ a b c Shoemaker, Alfred Lewis. (1959) Christmas in Pennsylvania: a folk-cultural study. Edition 40. pp. 52, 53. Stackpole Books 1999. ISBN 0811703282.

- ^ Murray, Brian. "Christmas lights and community building in America," History Matters, Spring 2006.

- ^ Miles, Clement, Christmas customs and traditions, Courier Dover Publications, 1976, ISBN 0486233545, p.32

- ^ Miles, pp. 31–37

- ^ Miles, pp. 47–48

- ^ Dudley-Smith, Timothy (1987). A Flame of Love. London: Triangle/SPCK. ISBN 0-281-04300-0.

- ^ Richard Michael Kelly. A Christmas carol p.10. Broadview Press, 2003 ISBN 1551114763

- ^ a b Forbes, Bruce David, Christmas: a candid history, University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0520251040, pp. 68–79.

- ^ Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Santa Claus

- ^ John Steele Gordon, The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000 (Scribner) 1999.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David, Christmas: a candid history, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara and David P., "The Claus That Refreshes", Snopes.com, 2006.

- ^ "History of the Society". The Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jones, Charles W., "Knickerbocker Santa Claus", The New-York Historical Society Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 4.

- ^ Charles W. Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1978).

- ^ Hageman, Howard G. (1979), "Review of Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend", Theology Today, vol. 36, no. 3, Princeton: Princeton Theological Seminary, retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Matera, Mariane. "Santa: The First Great Lie", Citybeat, Issue 304

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F., The Origins of Christmas, Liturgical Press, 2004, p. 67-69.

- ^ ""Mithraism", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913.

- ^ "Sol," Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago (2006).

- ^ ""Christmas – An Ancient Holiday", The History Channel, 2007.

- ^ Coffman, Elesha. Why December 25? Christian History & Biography, Christianity Today, 2000.

- ^ Yule. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- ^ "Christmas, Encyclopædia Britannica Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006.

- ^ Roll, p. 78, citing calculations by Roger Beckworth. Roll, pp. 79–80, then cites Roland Bainton to say that Clement may have used two separate calendars and the discrepancies between them eventually "yields 6 January, in 2 CE".

- ^ "Christmas, Encyclopædia Britannica Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006.

- ^ Roll, p. 79, 80. Only fragments of Chronographai survive. In one fragment, Africanus referred to "Pege in Bethlehem" and "Lady Pege, Spring-bearer." See "Narrative Narrative of Events Happening in Persia on the Birth of Christ Narrative."

- ^ Bradt, Hale, Astronomy Methods, (2004), p. 69.

Roll p. 87. - ^ Roll p.81f

- ^ Origen, "Levit., Hom. VIII"; Migne P.G., XII, 495.

"Natal Day", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911. - ^ This document was prepared privately for a Roman aristocrat. The reference in question states, "VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ".[1] It is in a section copied from an earlier manuscript produced in 336.[2] This document also contains the earliest known reference to the feast of Sol Invictus.[3]

- ^ Pokhilko, Hieromonk Nicholas, "History of Epiphany"

- ^ a b c d e f Murray, Alexander, "Medieval Christmas", History Today, December 1986, 36 (12), pp. 31 – 39.

- ^ a b McGreevy, Patrick. "Place in the American Christmas," (JSTOR), Geographical Review, Vol. 80, No. 1. January 1990, pp. 32–42. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c Restad, Penne L. (1995), Christmas in America: a History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510980-5

- ^ a b c Durston, Chris, "Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642–60", History Today, December 1985, 35 (12) pp. 7 – 14.

- ^ http://mercuriuspoliticus.wordpress.com/2008/12/21/a-christmassy-post/

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. p. 211.

- ^ When Christmas Was Banned – The early colonies and Christmas

- ^ Nancy Smith Thomas. Moravian Christmas in the South. p. 20. 2007 ISBN 0807831816

- ^ Andrews, Peter (1975). Christmas in Colonial and Early America. USA: World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. ISBN 7-166-2001-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Les Standiford. The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits, Crown, 2008. ISBN 978-0307405784

- ^

"Dickens' classic 'Christmas Carol' still sings to us". USA Today.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rowell, Geoffrey, Dickens and the Construction of Christmas, History Today, Volume: 43 Issue: 12, December 1993, pp. 17 – 24

- ^ Ronald Hutton Stations of the Sun: The Ritual Year in England. 1996. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285448-8.

- ^ Richard Michael Kelly (ed.) (2003), A Christmas Carol. pp.9,12 Broadview Literary Texts, New York: Broadview Press ISBN 1551114763

- ^ Robertson Cochrane. Wordplay: origins, meanings, and usage of the English language. p.126 University of Toronto Press, 1996 ISBN 0802077528

- ^ Joe L. Wheeler. Christmas in my heart, Volume 10. p.97. Review and Herald Pub Assoc, 2001. ISBN 0828016224

- ^ Earnshaw, Iris (November 2003). "The History of Christmas Cards". Inverloch Historical Society Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ The girlhood of Queen Victoria: a selection from Her Majesty's diaries. p.61. Longmans, Green & co., 1912. University of Wisconsin

- ^ Godey's Lady's Book, 1850. Godey's copied it exactly, except removed the Queen's crown, and Prince Albert's mustache, to remake the engraving into an American scene.

- ^ Kelly, Richard Michael (ed.) (2003), A Christmas Carol. p.20. Broadview Literary Texts, New York: Broadview Press, ISBN 1551114763

- ^ Moore's poem transferred the genuine old Dutch traditions celebrated at New Year in New York, including the exchange of gifts, family feasting, and tales of “sinterklass” (a derivation in Dutch from “Saint Nicholas,” from whence comes the modern “Santa Claus”) to Christmas.The history of Christmas: Christmas history in America, 2006

- ^ usinfo.state.gov “Americans Celebrate Christmas in Diverse Ways” November 26, 2006

- ^ First Presbyterian Church of Watertown “Oh . . . and one more thing” December 11, 2005

- ^ a b c Restad, Penne L. (1995), Christmas in America: a History. p.96. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510980-5

- ^ a b Christian church of God – history of Christmas

- ^ Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. ©1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p 148 ISBN 0-471-291-98-6

- ^ Marta Patiño, The Puritan Ban on Christmas

- ^ "Why did Cromwell abolish Christmas?". Oliver Cromwell. The Cromwell Association. 2001. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Christmas controversy article – Muslim Canadian Congress.

- ^ "Jews for Christmas"—NewsMax article

- ^ Don Feder on Christmas – Jewish World review

- ^ Gibson, John, The War on Christmas, Sentinel Trade, 2006, pp. 1–6

- ^ Richard N. OstlingThe Associated PressNovember 14, 2005. "Law.com – Have Yourself a Merry Little Lawsuit Now". Law.com. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Lynch vs. Donnelly (1984)

- ^ "Appeals Court: School district can ban Christmas carols". Philly.com. Philadelphia Inquirer. 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Boycott Gap, Old Navy, and Banana Republic this Christmas

- ^ April Mitchinson (2009-11-29). "Differences set aside for Winter Night Light festival in Dundee". The Press and Journal. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ Varga, Melody. "Black Friday, About:Retail Industry.

- ^ Gwen Outen (2004-12-03). "ECONOMICS REPORT – Holiday Shopping Season in the U.S." Voice Of America.

- ^ US Census Bureau. "Facts. The Holiday Season" December 19, 2005. (accessed Nov 30 2009)

- ^ US Census 2005

- ^ "The Deadweight Loss of Christmas", American Economic Review, December 1993, 83 (5)

- ^ "Is Santa a deadweight loss?" The Economist December 20, 2001

- ^ Reuters. "Christmas is Damaging the Environment, Report Says" December 16, 2005.

Further reading

- Restad, Penne L. (1995). Christmas in America: A History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509300-3.

- The Battle for Christmas, by Stephen Nissenbaum (1996; New York: Vintage Books, 1997). ISBN 0-679-74038-4

- The Origins of Christmas, by Joseph F. Kelly (August 2004: Liturgical Press) ISBN 978-0814629840

- Christmas Customs and Traditions, by Clement A. Miles (1976: Dover Publications) ISBN 978-0486233543

- The World Encyclopedia of Christmas, by Gerry Bowler (October 2004: McClelland & Stewart) ISBN 978-0771015359

- Santa Claus: A Biography, by Gerry Bowler (November 2007: McClelland & Stewart) ISBN 978-0771016684

- There Really Is a Santa Claus: The History of St. Nicholas & Christmas Holiday Traditions, by William J. Federer (December 2002: Amerisearch) ISBN 978-0965355742

- St. Nicholas: A Closer Look at Christmas, by Jim Rosenthal (July 2006: Nelson Reference) ISBN 1418504076

- Just say Noel: A History of Christmas from the Nativity to the Nineties, by David Comfort (November 1995: Fireside) ISBN 978-0684800578

- 4000 Years of Christmas: A Gift from the Ages, by Earl W. Count (November 1997: Ulysses Press) ISBN 978-1569750872

- Sammons, Peter (May 2006). The Birth of Christ. Glory to Glory Publications (UK). ISBN 0-9551790-1-7.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Christmas: Its Origin and Associations, by William Francis Dawson, 1902, from Project Gutenberg

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA