Spratly Islands: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 203.127.7.82 (talk) to last version by SchreiberBike |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

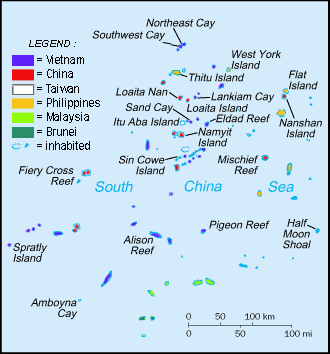

The '''Spratly Islands''' (Chinese: ''Nansha islands'', Filipino: ''Kapuluan ng Kalayaan'',<ref>{{cite news |last=Anda |first=Redempto |title=Government told of China buildup 2 months ago |url=http://globalnation.inquirer.net/44553 |accessdate=29 October 2013 |newspaper=Philippine Inquirer |date=17 July 2012}}</ref> Malay: ''Kepulauan Spratly'' and Vietnamese: ''Quần đảo Trường Sa'') are a [[Spratly Islands dispute|disputed]] group of more than 750 [[reef]]s, [[islet]]s, [[atoll]]s, [[cay]]s and [[island]]s in the [[South China Sea]].<ref name="ECO" /> The [[archipelago]] lies off the coasts of the [[Philippines]], [[Malaysia]], and southern [[Vietnam]]. Named after the 19th-century British whaling captain [[Richard Spratly]] who sighted [[Spratly Island]] in 1843, the islands contain approximately 4 km<sup>2</sup> (1.5 mi<sup>2</sup>) of land area spread over a vast area of more than 425,000 km<sup>2</sup> (164,000 mi<sup>2</sup>). |

The '''Spratly Islands''' (Chinese: ''Nansha islands'', Filipino: ''Kapuluan ng Kalayaan'',<ref>{{cite news |last=Anda |first=Redempto |title=Government told of China buildup 2 months ago |url=http://globalnation.inquirer.net/44553 |accessdate=29 October 2013 |newspaper=Philippine Inquirer |date=17 July 2012}}</ref> Malay: ''Kepulauan Spratly'' and Vietnamese: ''Quần đảo Trường Sa'') are a [[Spratly Islands dispute|disputed]] group of more than 750 [[reef]]s, [[islet]]s, [[atoll]]s, [[cay]]s and [[island]]s in the [[South China Sea]].<ref name="ECO" /> The [[archipelago]] lies off the coasts of the [[Philippines]], [[Malaysia]], and southern [[Vietnam]]. Named after the 19th-century British whaling captain [[Richard Spratly]] who sighted [[Spratly Island]] in 1843, the islands contain approximately 4 km<sup>2</sup> (1.5 mi<sup>2</sup>) of land area spread over a vast area of more than 425,000 km<sup>2</sup> (164,000 mi<sup>2</sup>). |

||

The Spratlys are one of the major archipelagos in the South China Sea which comprise more than 30,000 islands and reefs,{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} and which complicate governance and economics in this part of Southeast Asia. Such small and remote islands have |

The Spratlys are one of the major archipelagos in the South China Sea which comprise more than 30,000 islands and reefs,{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} and which complicate governance and economics in this part of Southeast Asia. Such small and remote islands have massive economic value and are important to the claimants in their attempts to establish international boundaries. The islands have no indigenous inhabitants, but offer rich fishing grounds, and may contain significant oil and natural gas reserves.<ref name="Owen2012a">Owen, N. A. and C. H. Schofield, 2012, ''Disputed South China Sea hydrocarbons in perspective.'' Marine Policy. vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 809-822.</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Q&A: South China Sea dispute |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-13748349 |accessdate=30 October 2013}}</ref> |

||

The northeast of the Spratlys are known to mariners as [[Dangerous Ground (South China Sea)|Dangerous Ground]], and are characterised by many low islands, sunken reefs and atolls awash, with reefs often rising abruptly from ocean depths greater than 1000m - all of which makes the area dangerous for navigation. |

The northeast of the Spratlys are known to mariners as [[Dangerous Ground (South China Sea)|Dangerous Ground]], and are characterised by many low islands, sunken reefs and atolls awash, with reefs often rising abruptly from ocean depths greater than 1000m - all of which makes the area dangerous for navigation. |

||

Revision as of 15:00, 13 May 2015

| |

| Other names | South Sand Islands[1] |

|---|---|

| Geography | |

| Location | South China Sea |

| Coordinates | 10°N 114°E / 10°N 114°E |

| Demographics | |

| Population | No indigenous peoples |

| Spratly Islands | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南沙群島 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南沙群岛 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Quần Đảo Trường Sa | ||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 群島長沙 | ||||||||||||||||

| Malay name | |||||||||||||||||

| Malay | Kepulauan Spratly Gugusan Semarang Peninjau[5][6][7] | ||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Kapuluan ng Kalayaan | ||||||||||||||||

The Spratly Islands (Chinese: Nansha islands, Filipino: Kapuluan ng Kalayaan,[8] Malay: Kepulauan Spratly and Vietnamese: Quần đảo Trường Sa) are a disputed group of more than 750 reefs, islets, atolls, cays and islands in the South China Sea.[9] The archipelago lies off the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia, and southern Vietnam. Named after the 19th-century British whaling captain Richard Spratly who sighted Spratly Island in 1843, the islands contain approximately 4 km2 (1.5 mi2) of land area spread over a vast area of more than 425,000 km2 (164,000 mi2).

The Spratlys are one of the major archipelagos in the South China Sea which comprise more than 30,000 islands and reefs,[citation needed] and which complicate governance and economics in this part of Southeast Asia. Such small and remote islands have massive economic value and are important to the claimants in their attempts to establish international boundaries. The islands have no indigenous inhabitants, but offer rich fishing grounds, and may contain significant oil and natural gas reserves.[10][11]

The northeast of the Spratlys are known to mariners as Dangerous Ground, and are characterised by many low islands, sunken reefs and atolls awash, with reefs often rising abruptly from ocean depths greater than 1000m - all of which makes the area dangerous for navigation.

In addition to various territorial claims, some of the features have civilian settlements, but of the approximately 45 islands, reefs, cays and other features that are occupied, all contain structures which are occupied by military forces (from the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan), Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia). Additionally, Brunei has claimed (but does not occupy) an exclusive economic zone in the southeastern part of the Spratlys which includes the Louisa Reef. These claims and occupations have led to escalating tensions between these countries over the status and "ownership" of the islands.

Geographic and economic overview

The Spratly Islands contain almost no significant arable land, have no indigenous inhabitants, and very few of the islands have a permanent drinkable water supply. Natural resources include fish, and guano, as well as the possible potential of oil and natural gas reserves.[12] Economic activity has included commercial fishing, shipping, guano mining, and more recently, tourism.

The Spratlys are located near several primary shipping lanes.

Geology

The Spratly Islands consist of reefs, banks and shoals that consist of biogenic carbonate. These accumulations of biogenic carbonate lie upon the higher crests of major submarine ridges that are uplifted fault blocks known by geologists as horsts. These horsts are part of a series of parallel and en echelon, half-grabens and rotated fault-blocks. The long axes of the horsts, rotated fault blocks and half-grabens form well-defined linear trends that lie parallel to magnetic anomalies exhibited by the oceanic crust of the adjacent South China Sea. The horsts, rotated fault blocks, and the rock forming the bottoms of associated grabens consist of stretched and subsided continental crust that is composed of Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous strata that include calc-alkalic extrusive igneous rocks, intermediate to acid intrusive igneous rocks, sandstones, siltstones, dark-green claystones, and metamorphic rocks that include biotite-muscovite-feldspar-quartz migmatites and garnet-mica schists.[13][14][15]

The dismemberment and subsidence of continental crust into horsts, rotated fault blocks and half-grabens that underlie the Spratly Islands and surrounding sea bottom occurred in 2 distinct periods. They occurred as the result of the tectonic stretching of continental crust along underlying deeply rooted detachment faults. During the Late Cretaceous and Early Oligocene, the earliest period of tectonic stretching of continental crust and formation of horsts, half-grabens, and rotated fault-blocks occurred in association the rifting and later sea-floor spreading that created the South China Sea. During the Late Oligocene-Early Miocene additional stretching and block faulting of continental crust occurred within the Spratly Islands and adjacent Dangerous Ground. During and after this period of tectonic activity, corals and other marine life colonised the crests of the horsts and other ridges that lay in shallow water. The remains of these organisms accumulated over time as biogenic carbonates that comprise the current day reefs, shoals and cays of the Spratly Islands. Starting with their formation in Late Cretaceous, fine-grained organic-rich marine sediments accumulated within the numerous submarine half-grabens that underlie sea bottom within the Dangerous Ground region.[13][14][15]

The geological surveys show localised areas within the Spratly Islands region are favourable for the accumulation of economic oil and gas reserves. They include thick sequences of Cenozoic sediments east of the Spratly Islands. Southeast and west of them, there also exist thick accumulations of sediments that possibly might contain economic oil and gas reserves lie closer to the Spratly Islands.[10][16]

Ecology

In some cays in the Spratly Islands, the sand and pebble sediments form the beaches and spits around the island. Under the influence of the dominant wind direction which changes seasonally, these sediments move around the island to change the shape and size of the island. For example, Spratly Island is larger during the northeast monsoon, (about 700 x 300 meters), and smaller during the southwest monsoon, (approximately 650 x 320 meters).[17]

Some islands may contain fresh groundwater fed by rain. Groundwater levels fluctuate during the day with the rhythm of the tides.[18]

Phosphates from bird faeces (guano) are mainly concentrated in the beach rocks by the way of exchange-endosmosis. The principal minerals bearing phosphate are podolite, lewistonite and dehonite.[19]

Coral reefs

Coral reefs are the predominant structure of these islands; the Spratly group contains over 600 coral reefs in total.[9]

Vegetation

Little vegetation grows on these islands, which are subject to intense monsoons. Larger islands are capable of supporting tropical forest, scrub forest, coastal scrub and grasses. It is difficult to determine which species have been introduced or cultivated by humans. Taiping Island (Itu Aba) was reportedly covered with shrubs, coconut, and mangroves in 1938; pineapple was also cultivated there when it was profitable. Other accounts mention papaya, banana, palm, and even white peach trees growing on one island. A few islands which have been developed as small tourist resorts had soil and trees brought in and planted where there was none.[9]

Wildlife

A total of 2,927 marine species were recorded in the Spratly Sea, including: 776 benthic species, 382 species of hard coral, 524 species of marine fish, 262 species of algae and sea grass, 35 species of seabirds, 20 species of marine mammals and sea turtles, etc.[20]

Terrestrial vegetation in the islands includes 103 species of vascular plants of magnolia branches (Magnoliophyta) of 39 families and 79 genera.[20]

The islands that do have vegetation provide important habitats for many seabirds and sea turtles.[9]

Both the green turtle (Chelonia mydas, endangered) and the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata, critically endangered) formerly occurred in numbers sufficient to support commercial exploitation. These species reportedly continue to nest even on islands inhabited by military personnel (such as Pratas) to some extent, though it is believed that their numbers have declined.[9]

Seabirds use the islands for resting, breeding, and wintering sites. Species found here include: streaked shearwater (Calonectris leucomelas), brown booby (Sula leucogaster), red-footed booby (S. sula), great crested tern (Sterna bergii), and white tern (Gygis alba). Little information is available regarding the current status of the islands' seabird populations, though it is likely that birds may divert nesting sites to smaller, less disturbed islands. Bird eggs cover the majority of Song Tu, a small island in the eastern Danger Zone.[9]

This ecoregion is still largely a mystery. Scientists have focused their research on the marine environment, while the ecology of the terrestrial environment remains relatively unknown.[9]

Ecological hazards

Political instability, tourism and the increasing industrialisation of neighbouring countries has led to serious disruption of native flora and fauna, over-exploitation of natural resources, and environmental pollution. Disruption of nesting areas by human activity and/or by introduced animals, such as dogs, has reduced the number of turtles nesting on the islands. Sea turtles are also slaughtered for food on a significant scale. The sea turtle is a symbol of longevity in Chinese culture and at times the military personnel are given orders to protect the turtles.[9]

Heavy commercial fishing in the region incurs other problems. Although it has been outlawed, fishing methods continue to include the use of bottom trawlers fitted with chain rollers. In addition, during a recent[timeframe?] routine patrols[by whom?], more than 200 kg of Potassium cyanide solution was confiscated from fishermen who had been using it for fish poisoning. These activities have a devastating impact on local marine organisms and coral reefs.[9]

Some interest has been taken[by whom?] in regard to conservation of these[which?] island ecosystems. J.W. McManus[who?] has explored the possibilities of designating portions of the Spratly Islands as a marine park. One region of the Spratly Archipelago, named Truong Sa, was proposed by Vietnam's Ministry of Science, Technology, and the Environment (MOSTE) as a future protected area. The site, with an area of 160 km2 (62 mi2), is currently managed by the Khanh Hoa Provincial People's Committee of Vietnam.[9]

Military groups in the Spratlys have engaged in environmentally damaging activities such as shooting turtles and seabirds, raiding nests and fishing with explosives. The collection of rare medicinal plants, collecting of wood, and hunting for the wildlife trade are common threats to the biodiversity of the entire region, including these islands. Coral habitats are threatened by pollution, over-exploitation of fish and invertebrates, and the use of explosives and poisons as fishing techniques.[9]

History

Chinese texts of the 12th century record these islands being a part of Chinese territory and that they had earlier (206 BC) been used as fishing grounds during the Han dynasty.[21] Further records show the islands as inhabited at various times in history by Chinese and Vietnamese fishermen, and during the second world war by troops from French Indochina and Japan.[22][23][24] However, there were no large settlements on these islands until 1956, when Filipino adventurer Tomás Cloma, Sr., decided to "claim" a part of Spratly islands as his own, naming it the "Free Territory of Freedomland".[25]

Early cartography

The first possible human interaction with the Spratly Islands dates back between 600 BCE to 3 BCE. This is based on the theoretical migration patterns of the people of Nanyue (southern China and northern Vietnam) and Old Champa kingdom who may have migrated from Borneo, which may have led them through the Spratly Islands.[26]

Ancient Chinese maps record the "Thousand Li Stretch of Sands"; Qianli Changsha (千里長沙) and the "Ten-Thousand Li of Stone Pools"; Wanli Shitang (萬里石塘),[27] which China today claims refers to the Spratly Islands. The Wanli Shitang have been explored by the Chinese since the Yuan dynasty and may have been considered by them to have been within their national boundaries.[28][29] They are also referenced in the 13th century,[30] followed by the Ming dynasty.[31] When the Ming Dynasty collapsed, the Qing dynasty continued to include the territory in maps compiled in 1724,[32] 1755,[33] 1767,[34] 1810,[35] and 1817.[36]

A Vietnamese map from 1834 also combines the Spratly and Paracel Islands into one region known as "Vạn Lý Trường Sa"[citation needed], a feature commonly incorporated into maps of the era (萬里長沙) ‒ that is, a combination of half of the 2 aforementioned Chinese island names, "Wanli" and "Changsha".[37] According to Hanoi, Vietnamese maps record Bãi Cát Vàng (Golden Sandbanks, referring to both the Spratly and Paracel Islands) which lay near the Coast of the central Vietnam as early as 1838.[38] In Phủ Biên Tạp Lục (The Frontier Chronicles) by scholar Lê Quý Đôn, both Hoàng Sa and Trường Sa were defined as belonging to the Quảng Ngãi District. He described it as where sea products and shipwrecked cargoes were available to be collected. Vietnamese text written in the 17th century referenced government-sponsored economic activities during the Lê dynasty, 200 years earlier. The Vietnamese government conducted several geographical surveys of the islands in the 18th century.[38]

Despite the fact that China and Vietnam both made a claim to these territories simultaneously, at the time, neither side was aware that its neighbour had already charted and made claims to the same stretch of islands.[38]

The islands were sporadically visited throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries by mariners from different European powers (including Richard Spratly, after whom the island group derives its most recognisable English name).[39] However, these nations showed little interest in the islands.

British naval captain James George Meads in the 1870s laid claim to the islands, proclaiming a micronation called Republic of Morac-Songhrati-Meads. Descendants of Meads have continued to claim legitimacy over the islands, and continue to attempt to claim ownership of the island's resources.[40][41][42]

In 1883, German boats surveyed the Spratly and the Paracel Islands but eventually withdrew the survey, after receiving protests from the Guangdong government representing the Qing dynasty. Many European maps before the 20th century do not even mention this region.[43]

Military conflict and diplomatic dialogues

The following are political divisions for the Spratly Islands claimed by various area nations (in alphabetical order):

- Brunei: Part of Brunei's Exclusive Economic Zone[44]

- China: Part of Sansha city, Hainan province[45]

- Malaysia: Part of Sabah state

- Philippines: Part of Palawan province

- Taiwan (Republic of China): Part of Kaohsiung municipality

- Vietnam: Part of Khánh Hòa Province

In 1933, France asserted its claims from 1887[46] to the Spratly and Paracel Islands on behalf of its then-colony Vietnam.[47] It occupied a number of the Spratly Islands, including Taiping Island, built weather stations on 2 of the islands, and administered them as part of French Indochina. This occupation was protested by the Republic of China (ROC) government because France admitted finding Chinese fishermen there when French warships visited 9 of the islands.[48] In 1935, the ROC government also announced a sovereignty claim on the Spratly Islands. Japan occupied some of the islands in 1939 during World War II, and it used the islands as a submarine base for the occupation of Southeast Asia. During the Japanese occupation, these islands were called Shinnan Shoto (新南諸島), literally the New Southern Islands, and together with the Paracel Islands (西沙群岛), they were put under the governance of the Japanese colonial authority in Taiwan.

Japan occupied the Paracels and the Spratlys from February 1939 to August 1945.[49]

In November 1946, the ROC sent naval ships to take control of the islands after the surrender of Japan.[49] It had chosen the largest and perhaps the only inhabitable island, Taiping Island, as its base, and it renamed the island under the name of the naval vessel as Taiping. Also following the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II, the ROC re-claimed the entirety of the Spratly Islands (including Taiping Island) after accepting the Japanese surrender of the islands based on the Cairo and Potsdam Declarations.[citation needed] Japan had renounced all claims to the islands in the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty together with the Paracels, Pratas and other islands captured from the Chinese, and upon these declarations, the government of the Republic of China reasserted its claim to the islands. The KMT force of the ROC government withdrew from most of the Spratly and Paracel Islands after they retreated to Taiwan from the opposing Communist Party of China due to their losses in the Chinese Civil War and the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949.[47] The ROC quietly withdrew troops from Taiping Island in 1950, but then reinstated them in 1956 in response to Tomás Cloma's sudden claim to the island as part of Freedomland.[50] As of 2013[update], Taiping Island is administered by the ROC.[51]

In 1988, the Vietnamese and Chinese navies engaged in a skirmish in the area of Johnson South Reef (also called Yongshu reef in China and Mabini reef in Philippines).[52]

It was unclear whether France continued its claim to the islands after WWII, since none of the islands, other than Taiping Island, was habitable. The South Vietnamese government took over the Trường Sa administration after the defeat of the French at the end of the First Indochina War. In 1958, the PRC issued a declaration defining its territorial waters, which encompassed the Spratly Islands. North Vietnam's prime minister, Phạm Văn Đồng, sent a formal note to Zhou Enlai, stating that the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) respected the Chinese decision regarding the 12 nmi (22 km; 14 mi) limit of territorial waters.[53] While accepting the 12-nmi principal with respect to territorial waters, the letter did not actually address the issue of defining actual territorial boundaries.

In 1999, a Philippine navy ship (Number 57 - BRP Sierra Madre) was purposely run aground near Second Thomas Shoal to enable establishment of an outpost. As of 2014[update] it had not been removed, and Filipino troops have been stationed aboard since the grounding.[54][55]

On 23 May 2011, the President of the Philippines, Benigno Aquino III, warned visiting Chinese Defence Minister Liang Guanglie of a possible arms race in the region if tensions worsened over disputes in the South China Sea. Aquino said he told Liang in their meeting that this could happen if there were more encounters in the disputed and potentially oil-rich Spratly Islands.[56]

In May 2011, Chinese patrol boats attacked 2 Vietnamese oil exploration ships near the Spratly Islands.[57] Also in May 2011, Chinese naval vessels opened fire on Vietnamese fishing vessels operating off East London Reef (Da Dong). The 3 Chinese military vessels were numbered 989, 27 and 28, and they showed up with a small group of Chinese fishing vessels. Another Vietnamese fishing vessel was fired on near Fiery Cross Reef (Chu Thap). The Chief Commander of Border Guards in Phu Yen Province, Vietnam reported that a total of 4 Vietnamese vessels were fired upon by Chinese naval vessels.[verification needed] These incidents involving Chinese forces sparked mass protests in Vietnam, especially in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City,[58] and in various Vietnamese communities in the West (namely in the US state of California and in Paris) over attacks on Vietnamese citizens and the intrusion into what Vietnam claimed was part of its territory.[59]

In June 2011, the Philippines began officially referring to the South China Sea as the "West Philippine Sea" and the Reed Bank as "Recto Bank".[60][61]

In July 2012, the National Assembly of Vietnam passed a law demarcating Vietnamese sea borders to include the Spratly and Paracel Islands.[62][63]

In a series of news stories on 16 April 2015, it was revealed, through photos taken by Airbus Group, that China had been building an airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef, one of the southern islands. The 10,000ft (3,048m) long runway covers a significant portion of the island, and is viewed as a possible strategic threat to other countries with claims to the islands, such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

Various factions of the Muslim Moro people are waging a war for independence against the Philippines. The website of the separatist Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) of Nur Misuari declared its support for China against the Philippines in the South China Sea dispute, calling both China and the Moro people as victims of Philippine colonialism, and noting China's history of friendly relations with the Moros.[64] The MNLF website also denounced America's assistance to the Philippines in their colonisation of the Moro people in addition to denouncing the Philippines claims to the islands disputed with China, and denouncing America for siding with the Philippines in the dispute, noting that in 1988 China "punished" Vietnam for attempting to set up a military presence on the disputed islands, and noting that the Moros and China maintained peaceful relations, while on the other hand the Moros had to resist other colonial powers, having to fight the Spanish, fight the Americans, and fight the Japanese, in addition to fighting the Philippines.[65]

Champa historically had a large presence in the South China Sea. The Vietnamese broke Champa's power in an invasion of Champa in 1471, and then finally conquered the last remnants of the Cham people in an invasion in 1832. A Cham named Katip Suma who received Islamic education in Kelantan declared a Jihad against the Vietnamese, and fighting continued until the Vietnamese crushed the remnants of the resistance in 1835. The Cham organisation Front de Libération du Champa was part of the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races, which waged war against the Vietnamese for independence in the Vietnam War along with the Montagnard and Khmer Krom minorities. The last remaining FULRO insurgents surrendered to the United Nations in 1992. Vietnam has settled over a million ethnic Vietnamese on Montagnard lands in the Central Highlands. The Montagnard staged a massive protest against the Vietnamese in 2001, which led to the Vietnamese to forcefully crush the uprising and seal the entire area off to foreigners.

The Vietnamese government fears that evidence of Champa's influence over the disputed area in the South China Sea would bring attention to human rights violations and killings of ethnic minorities in Vietnam such as in the 2001 and 2004 uprisings, and lead to the issue of Cham autonomy being brought into the dispute, since the Vietnamese conquered the Hindu and Muslim Cham people in a war in 1832, and the Vietnamese continue to destroy evidence of Cham culture and artefacts left behind, plundering or building on top of Cham temples, building farms over them, banning Cham religious practices, and omitting references to the destroyed Cham capital of Song Luy in the 1832 invasion in history books and tourist guides. The situation of Cham compared to ethnic Vietnamese is substandard, lacking water and electricity and living in houses made out of mud.[66]

The Cham in Vietnam are only recognised as a minority, and not as an indigenous people by the Vietnamese government despite being indigenous to the region. Both Hindu and Muslim Chams have experienced religious and ethnic persecution and restrictions on their faith under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confisticating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus. In 2010 and 2013 several incidents occurred in Thành Tín and Phươc Nhơn villages where Cham were murdered by Vietnamese. In 2012, Vietnamese police in Chau Giang village stormed into a Cham Mosque, stole the electric generator, and also raped Cham girls.[67] Cham Muslims in the Mekong Delta have also been economically marginalised and pushed into poverty by Vietnamese policies, with ethnic Vietnamese Kinh settling on majority Cham land with state support, and religious practices of minorities have been targeted for elimination by the Vietnamese government.[68]

Transportation and communication

Airports

| Location | Occupied by | Name | Code | Built | Length | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiping Island | Taiping Island Airport | RCSP | 2007 | 1,200 m (est.) | Military use only. No refueling facilities.[69] | |

| Swallow Reef (Layang-Layang) | Layang-Layang Airport | LAC | 1995 | 1,367 m | Dual-use concrete airport. | |

| Fiery Cross Reef | Yongshu Airport | AG 4553 | 2016 | 3,300 m (est.) | Dual-use concrete airport. | |

| Subi Reef | Zhubi Airport | 2016 | 3,000 m (est.) | Dual-use concrete airport. | ||

| Mischief Reef | Meiji Airport | 2016 | 2,700 m (est.) | Dual-use concrete airport. | ||

| Thitu Island (Pag-asa) | Rancudo Airfield | RPPN | 1978 | 1,300 m (est.) | Dual-use concrete airport.[70] | |

| Spratly Island (Trường Sa) | Trường Sa Airport | 1976–77 | 1,200 m (est.)[71] | Military use only. Extended from 600 m to 1,200 m in 2016.[71] |

Telecommunications

In 2005, a cellular phone base station was erected by the Philippines' Smart Communications on Pag-asa Island.[72]

On 18 May 2011, China Mobile announced that its mobile phone coverage has expanded to the Spratly Islands. The extended coverage would allow soldiers stationed on the islands, fishermen, and merchant vessels within the area to use mobile services, and can also provide assistance during storms and sea rescues. The service network deployment over the islands took nearly one year.[73]

Gallery

-

An ancient Heliotropium foertherianum on Spratly Island

-

Young Vietnamese residents of Spratly Island

-

A military cemetery for Vietnamese soldiers on Central London Reef

-

A view from Amboyna Cay

-

The Pearson Reef dock under Vietnam's administration

See also

- List of islands in the South China Sea

- List of maritime features in the Spratly Islands

- Johnson South Reef Skirmish

- South China Sea Islands

- Paracel Islands

- Kingdom of Humanity

- Junk Keying

- Zheng He

- SSN, a computer game set during a conflict over the Spratly Islands.

- Chinese reunification

- Greater Philippines

References

- ^ Jones, Gareth Wyn (2002). "Provinces". In Boland-Crewe, Tara and Lea, David (ed.). The Territories of the People's Republic of China. London: Europa Publications. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-203-40311-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ With reclaimed land, Swallow Reef was probably the third largest "island" in the Spratlys. Reclamation activities by the PRC in 2014 have added significant land areas to a number of submerged reefs and atolls like Johnson South Reef, Fiery Cross Reef and the Gaven Reefs.

- ^ See List of maritime features in the Spratly Islands for information about individual islands.

- ^ 民政部关于国务院批准设立地级三沙市的公告-中华人民共和国民政部, Ministry of Civil Affairs of the PRC - Totally useless reference for readers of English wikipedia; No indication of what it's about, or why it's being quoted.

- ^ User, S. (1990). Pasukan Gugusan Semarang Peninjau. [online] Retrieved from: http://www.navy.mil.my/pusmastldm/index.php/penubuhan-unit/markas-wilayah-laut-2/pasukan-gugusan-semarang-peninjau [Accessed: 4 June 2013][dead link] - Totally useless reference for readers of English wikipedia; No indication of what it's about, or why it's being quoted.

- ^ "Slow progress on capability growth". Defence Review Asia.com. 22 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Navy.mil.my (n.d.). Untitled. [online] Retrieved from: http://www.navy.mil.my/index.php/component/k2/item/2479-warga-gugusan-semarang-peninjau-tldm-diraikan-di-pulau-layang-layang [Accessed: 4 June 2013].[dead link] - Unhelpful reference for readers of English wikipedia; No indication of what it's about, or why it's being quoted.

- ^ Anda, Redempto (17 July 2012). "Government told of China buildup 2 months ago". Philippine Inquirer. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "South China Sea Islands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ a b Owen, N. A. and C. H. Schofield, 2012, Disputed South China Sea hydrocarbons in perspective. Marine Policy. vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 809-822.

- ^ "Q&A: South China Sea dispute". Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Note, however, that a 2013 US EIA report questions the economic viability of many of the potential reserves.

- ^ a b Hutchison, C. S., and V. R. Vijayan, 2010, What are the Spratly Islands? Journal of Asian Earth Science. vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 371–385.

- ^ a b Wei-Weil, D., and L, Jia-Biao, 2011, Seismic Stratigraphy, Tectonic Structure and Extension Factors Across the Dangerous Grounds: Evidence from Two Regional Multi-Channel Seismic Profiles. Chinese Journal of Geophysics. vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 921–941.

- ^ a b Zhen, S., Z. Zhong-Xian, L. Jia-Biao, Z. Di, and W. Zhang-Wen, 2013, Tectonic Analysis of the Breakup and Collision Unconformities in the Nansha Block. Chinese Journal of Geophysics. vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 1069-1083.

- ^ Blanche, J. B. and J. D. Blanche, 1997, An Overview of the Hydrocarbon Potential of the Spratly Islands Archipelago and its Implications for Regional Development. in A. J. Fraser, S. J. Matthews, and R. W. Murphy, eds., pp. 293-310, Petroleum Geology of South East Asia. Special Publication no. 126, The Geological Society, Bath, England 436 pp.

- ^ "Động lực bồi tụ, xói lở bờ và sự thay đổi hình dạng đảo san hô Trường Sa - Deposition and erosion dynamics and shape change of the Spratly coral island". ResearchGate. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "Kết quả khảo sát bước đầu nước ngầm đảo san hô Trường Sa - results of preliminary survey for groundwater in Spratly coral Island". ResearchGate. 17 May 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "Một số đặc điểm địa chất đảo san hô Trường Sa - Some geological features of Spratly coral Island". ResearchGate. 21 May 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Vietnamese sea and islands - position, resources and typical geological and ecological wonders". researchgate.net.

- ^ "A List of books on the history of Spratly islands". Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ "Timeline". History of the Spratlys. www.spratlys.org. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Chemillier-Gendreau, Monique (2000). Sovereignty Over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Kluwer Law International. ISBN 9041113819.

- ^ China Sea pilot. Vol. 1 (8th ed.). Taunton: UKHO - United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. 2010.

- ^ "China and Philippines: The reasons why a battle for Zhongye (Pag-asa) Island seems unavoidable". China Daily Mail. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Thurgood, Graham (1999), From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change, University of Hawaii Press, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-8248-2131-9

- ^ Image: General Map of Distances and Historic Capitals, Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Jianming Shen (1998), "Territorial Aspects of the South China Sea Island Disputes", in Nordquist, Myron H.; Moore, John Norton (eds.), Security Flashpoints, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 165–166, ISBN 978-90-411-1056-5, ISBN 90-411-1056-9 ISBN 978-90-411-1056-5.

- ^ Historical Evidence To Support China's Sovereignty over Nansha Islands

- ^ History of Yuan geographical records: Yuan Dynasty Territorial Map (元代疆域图叙)

- ^ Miscellaneous Records of the South Sea Defensive Command 《海南卫指挥佥事柴公墓志》

- ^ Qing dynasty provincial map from tianxia world map 《清直省分图》之《天下总舆图》

- ^ Qing dynasty circuit and province map from Tianxia world map 《皇清各直省分图》之《天下总舆图》

- ^ Great Qing of 10,000-years Tianxia map 《大清万年一统天下全图》

- ^ Great Qing of 10,000-years general map of all territory 《大清万年一统地量全图》

- ^ Great Qing tianxia overview map 《大清一统天下全图》

- ^ Alleged Early Map of the Spratly Islands near the Vietnamese Coast

- ^ a b c King C. Chen, China's War with Vietnam (1979) Dispute over the Paracels and Spratlys, pp. 42–48.

- ^ MARITIME BRIEFING, Volume I, Number 6: A Geographical Description of the Spratly Island and an Account of Hydrographic Surveys Amongst Those Islands, 1995 by David Hancox and Victor Prescott. Pages 14–15

- ^ Shavit, David (1990). The United States in Asia: A Historical Dictionary. Greenwood Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-313-26788-X.

- ^ Fowler, Michael; Bunck, Julie Marie (1995). Law, Power, and the Sovereign State. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-271-01470-9.

- ^ Whiting, Kenneth (2 February 1992). "Asian Nations Squabble Over Obscure String of Islands". Los Angeles Times. p. A2.

- ^ Map of Asia 1892, University of Texas

- ^ Borneo Post: When All Else Fails (archived from the original[dead link] on 28 February 2008) Additionally, pages 48 and 51 of "The Brunei-Malaysia Dispute over Territorial and Maritime Claims in International Law" by R. Haller-Trost, Clive Schofield, and Martin Pratt, published by the International Boundaries Research Unit, University of Durham, UK, points out that this is, in fact, a "territorial dispute" between Brunei and other claimants over the ownership of one above-water feature (Louisa Reef)

- ^ Romero, Alexis (8 May 2013). "China fishing boats cordon off Spratlys". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Paracel Islands, worldstatesmen.org

- ^ a b Spratly Islands[full citation needed], Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2008. All Rights Reserved.

- ^ Todd C. Kelly, Vietnamese Claims to the Truong Sa Archipelago[dead link], Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies, Vol.3, Fall 1999.

- ^ a b King 1979, p. 43

- ^ Kivimäki, Timo (2002), War Or Peace in the South China Sea?, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS), ISBN 87-91114-01-2

- ^ "Taiwan's Power Grab in the South China Sea".

- ^ Malig, Jojo (17 July 2012). "Chinese ships eye 'bumper harvest' in Spratly". ABS CBN News. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ http://www.mfa.gov.cn

- ^ Keck, Zachary (13 March 2014). "Second Thomas Shoal Tensions Intensify". The Diplomat. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "A game of shark and minnow". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Philippines warns of arms race in South China Sea | Inquirer Global Nation

- ^ Chinese patrol boats confront Vietnamese oil exploration ship in South China Sea

- ^ "South China Sea: Vietnamese hold anti-Chinese protest". BBC News Asia-Pacific. 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Người Việt biểu tình chống TQ ở Los Angeles" (in Vietnamese). BBC News Tiếng Việt. June 2011.

- ^ "It's West Philippine Sea". Inquirer.net. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ "Name game: PH now calls Spratly isle 'Recto Bank'". Inquirer.net. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Jane Perlez (21 June 2012). "Vietnam Law on Contested Islands Draws China's Ire". The New York Times.

- ^ China Criticizes Vietnam in Dispute Over Islands, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- ^ RRayhanR (8 October 2012). "HISTORICAL AND "HUMAN WRONG" OF PHILIPPINE COLONIALISM: HOW NOT TO RESPECT HISTORIC-HUMAN RIGHTS OF BANGSAMORO AND CHINA?". mnlfnet.com. Moro National Liberation Front (Misuari faction). Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ RRayhanR (11 August 2012). "IMPACT OF POSSIBLE CHINA-PHILIPPINES WAR WITHIN FILIPINO-MORO WAR IN MINDANAO". mnlfnet.com. Moro National Liberation Front (Misuari faction). Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Bray, Adam (16 June 2014). "The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ "Mission to Vietnam Advocacy Day (Vietnamese-American Meet up 2013) in the U.S. Capitol. A UPR report By IOC-Campa". Chamtoday.com. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Philip (December 2006). "Economy in Motion: Cham Muslim Traders in the Mekong Delta" (PDF). The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. 7 (3). The Australian National University: 238. doi:10.1080/14442210600965174. ISSN 1444-2213. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ The Taiping Island Airport was completed in December 2007, ("MND admits strategic value of Spratly airstrip." Taipei Times. 6 January 2006. p. 2 (MND is the ROC Ministry of National Defense)), and a C-130 Hercules transporter airplane first landed on the island on 21 January 2008.

- ^ Bong Lozada (18 June 2014). "Air Force to repair Pagasa Island airstrip". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Vietnam Responds". Center for Strategic and International Studies. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Kalayaan Islands of Palawan Province (video part 1 of 2), 14 November 2009

- ^ Ian Mansfield, 18 May 2011, China Mobile Expands Coverage to the Spratly Islands, Cellular News

Further reading

- Bonnet, Francois-Xavier (2012) Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal, Irasec, 14.

- Bouchat, Clarence J. (2013) Dangerous Ground: The Spratly Islands and U.S. Interests and Approaches, Strategic Studies Institute and US Army War College Press, Carlisle, PA.

- Cardenal, Juan Pablo; Araújo, Heriberto (2011). La silenciosa conquista china (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 258–261.

- Dzurek, Daniel J. and Clive H.Schofield. (1996) The Spratly Islands dispute: who's on first?. IBRU. ISBN 978-1-897643-23-5

- Hogan, C. Michael (2011) South China Sea, Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC.

- Menon, Rajan (11 September 2012) Worry about Asia, Not Europe, The National Interest, Issue: Sept–Oct 2012.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of the Spratly Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of the Spratly Islands Spratly Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage

Spratly Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage- Mariner's page of the Spratly Islands

- Taiwanese List with ~170 entries

- List of atolls with areas

- Template:Wayback

- Flags of the World (FOTW)[dead link] entry with various micronations on the Spratly Islands.

- Map showing the claims

- A tabular summary about the Spratly and Paracel Islands

- Another overview table of the Spratly Islands[dead link]

- CIA World Factbook for Spratly Islands

- Template:PDFlink, from Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Template:PDFlink

- Third Party Summary of the Dispute[dead link]

- Google Map of Spratly Islands

- Ji Guoxing (October 1995), Maritime Jurisdiction in the Three China Seas: Options For Equitable Settlement (PDF), Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

- A collection of documents on Spratly and Paracel Islands by Nguyen Thai Hoc Foundation

- Depositional and erosional of the coast and beach, and change of morphology of Spratly coral island

- Results of premininary survey for the underground water in Spratly coral island

- Some geological features of Spratly Island

- Vietnamese sea and islands – position resources, and typical geological and ecological wonders

- Some researches on marine topography and sedimentation in Spratly Islands

- Disputed islands

- Disputed territories in Asia

- Spratly Islands

- Territorial disputes of China

- Territorial disputes of Malaysia

- Territorial disputes of the Philippines

- Territorial disputes of Vietnam

- Territorial disputes of the Republic of China

- Sansha

- Districts of Khanh Hoa Province

- Geography of Kaohsiung

- Archipelagoes of the Pacific Ocean

- Archipelagoes of China

- Archipelagoes of the Philippines

- Archipelagoes of Taiwan

- Islands of Malaysia