Spanish language

| Spanish, Castilian | |

|---|---|

| Español, Castellano | |

| Pronunciation | /espaˈɲol/, /kast̪eˈʎano/ |

| Region | (see below) |

Native speakers | First languagea: 329 million[1] a as second and first language 500 million. All numbers are approximate. |

| Latin (Spanish variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | 21 countries, United Nations, European Union, Organization of American States, Organization of Ibero-American States, Union of South American Nations, North American Free Trade Agreement, Andean Community of Nations, Mercosur, Caricom, Latin Union, Antarctic Treaty. |

| Regulated by | Association of Spanish Language Academies (Real Academia Española and 21 other national Spanish language academies) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-2 | spa |

| ISO 639-3 | spa |

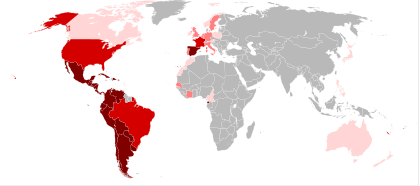

Countries where Spanish has official status.

States of the U.S. where Spanish has no official status but is spoken by 25% or more of the population.

States of the U.S. where Spanish has no official status but is spoken by 10-20% of the population.

States of the U.S. where Spanish has no official status but is spoken by 5-9.9% of the population. | |

Spanish or Castilian (español or castellano) is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several dialects and languages in the northern fringes of the Iberian Peninsula during the 10th century and gradually spread through the Kingdom of Castile, becoming the foremost language for government and trade in the Spanish Empire.

Latin, the basic foundation of the Spanish language, was introduced to the Iberian Peninsula by Romans during the Second Punic War around 210 BC. During the 5th century, Hispania was invaded by Germanic Vandals, Suevi, Alans, and Visigoths, resulting in numerous dialects of Vulgar Latin. After the Moorish Conquest in the 8th century, Arabic became an influence in the evolution of Iberian languages including Castilian.

Modern Spanish developed with the Readjustment of the Consonants (es: Reajuste de las sibilantes del castellano) that began in 15th century. The language continues to adopt foreign words from a variety of other languages, as well as developing new words. Castilian was taken most notably to the Americas as well as to Africa and Asia Pacific with the expansion of the Spanish Empire between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

As of 2009[update], 329 million people speak Spanish as a native language. It is the second most natively-spoken language in the world, after Mandarin Chinese.[1][2] Mexico contains the largest population of Spanish speakers. Spanish is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

History

Spanish evolved from Vulgar Latin introduced to the Iberian Peninsula by Romans during the Second Punic War around 210 BC, with some loan words from Arabic during the Andalusian period[3] and other surviving influences from Basque and Celtiberian, as well as Germanic languages via the Visigoths.

Castilian is thought to have evolved in the northern fringes of the Iberian Peninsula during the 10th century along the remote crossroad strips among the Alava, Cantabria, Burgos, Soria and La Rioja provinces of Northern Spain (see Glosas Emilianenses), as a strongly innovative and differing variant from its nearest cousin, Leonese, with a higher degree of Basque influence in these regions (see Iberian Romance languages). Modern Spanish developed in Castile with the Readjustment of the Consonants (es:Reajuste de las sibilantes del castellano) during the 15th century. Typical features of Spanish diachronical phonology include lenition (Latin [vita] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Spanish [vida] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), palatalization (Latin [annum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Spanish [año] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), and Latin [anellum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Spanish [anillo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and diphthongation (stem-changing) of short e and o from Vulgar Latin (Latin [terra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Spanish [tierra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Latin [novus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Spanish [nuevo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). Similar phenomena can be found in other Romance languages as well.

This northern dialect from Cantabria was carried south during the [Reconquista] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), and remains a minority language in the northern coastal Morocco.

The first Latin-to-Spanish grammar ([Gramática de la lengua castellana] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) was written in Salamanca, Spain, in 1492, by Elio Antonio de Nebrija, establishing once and for all the supremacy of the language of Castile over all others in the linguistic panorama of Spain. When it was presented to Isabel de Castilla, she asked, "¿Para qué querría yo un trabajo como éste, si ya conozco la lengua?" ("What would I want a work like this for, if I already know the language?"), to which he replied, "Su alteza, la lengua es el instrumento del Imperio" ("Your highness, the language is the instrument of the Empire.")[4] In his introduction to the first Spanish grammar, dated August 18, 1492, Nebrija wrote that "... language was always the companion of empire."[5]

From the 16th century onwards, the language was taken to the Americas and the Spanish East Indies via Spanish colonisation. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra influence on the Spanish language from the 17th century has been so great that Spanish is often called la lengua de Cervantes (The language of Cervantes).[6]

In the 20th century, Spanish was introduced to Equatorial Guinea and the Western Sahara, and to areas of the United States that had not been part of the Spanish Empire, such as Spanish Harlem in New York City. For details on borrowed words and other external influences upon Spanish, see Influences on the Spanish language.

Geographic Distribution

Spanish is recognized as one of the official languages of the United Nations, the European Union, the Organization of American States, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the African Union, the Union of South American Nations, the Latin Union, and the Caricom and has legal status in the North American Free Trade Agreement.

| Country | Population [7] | Number of Spanish speakers (first language)[8] | Speakers as a second language (in countries with Spanish official) or as a foreign language[9][10] | Spanish speakers as percentage of population[11] | Total number of Spanish speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 108,396,211 [12] | 99,908,787 | 6,861,481 | 98.5% | 106,770,268 |

| United States | 304,059,724[13] | 42,859,894 [14] | 7,140,106 | 15.4% [15] | 50,000,000[16] + 7,820,000 students[17] |

| Spain | 46,745,807 [18] | 41,603,769 [19] | 4,581,088 | 98.8% | 46,184,857 |

| Colombia | 45,300,000 [20] | 44,860,590 | 77,010 | 99.2% | 44,937,600 |

| Argentina | 40,518,951 [21] | 38,866,177 | 1,037,285 | 99.4% | 40,275,837 |

| Venezuela | 28,640,000 [22] | 27,631,872 | 664,448 | 98.8% | 28,296,320 |

| Peru | 29,461,933[23] | 23,501,784 | 2,012,250 | 86.6% | 25,514,034 |

| Chile | 17,094,270 [24] | 15,225,828 | 1,600,024 | 99.3% | 16,974,610 |

| Ecuador | 14,120,000 [25] | 13,125,952 | 725,768 | 98.1% | 13,851,720 |

| Brazil | 196,342,587 | 445,005 [26] | 12,000,000 [27] | 6.3% | 12,445,005 |

| Guatemala | 14,027,000 | 9,075,469 | 3,043,859 | 86.4% | 12,119,328 |

| Cuba | 11,204,000 | 11,136,776 | 99.4% | 11,136,776 | |

| Dominican Republic | 10,090,000 | 9,987,082 | 62,558 | 99.6% | 10,049,640 |

| Bolivia | 10,426,154[28] | 4,350,833 | 4,813,756 | 87.9% | 9,164,589 |

| El Salvador | 7,913,743[29] | 7,913,743 | 99.7% | 7,890,002 | |

| Honduras | 7,876,197[30] | 7,652,513 | 144,922 | 99.0% | 7,797,435 |

| Morocco | 29,680,069 [31] | 20,000 [32] | 6,479,935 | 21.9% [33] | 6,499,935 |

| France | 64,057,790 | 440,106 [34] | 5,721,380 | 9.6% | 6,161,486 |

| Nicaragua | 5,743,000 | 5,019,382 | 551,328 | 97.0% | 5,570,710 |

| Costa Rica | 4,549,903 | 4,345,130 | 87,126 | 99.2% | 4,432,256 |

| Paraguay | 6,349,000 | 3,498,299 | 914,256 | 69.5% | 4,412,555 |

| Puerto Rico | 3,982,000 | 3,786,882 [35] | 147,334 | 98.8% | 3,934,216 |

| United Kingdom | 60,943,912 | 107,654 [36] | 3,814,846 | 6.4% | 3,922,500 |

| Uruguay | 3,361,000 | 3,246,726 | 77,303 | 98.9 | 3,324,029 |

| Panama | 3,454,000 | 2,652,672 | 476,419 | 93.1% | 3,129,091 |

| Philippines | 96,061,683 | 2,658 [37] | 3,014,115 | 3.1% | 3,016,773 [38] |

| Germany | 82,369,548 | 140,000 [39] | 2,566,972 | 3.2% | 2,706,972 |

| Italy | 58,145,321 | 89,905 [40] | 1,968,320 | 3.5% | 2,058,225 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1,153,915 [41] | 158,086[42] | 995,829 | 90.5% [43] | 1,044,293 |

| Canada | 33,212,696 | 909,000 [44] | 92,853 | 3% | 1,001,853 |

| Portugal | 10,676,910 | 9,744 | 727,282 | 6.9% | 737,026 |

| Netherlands | 16,645,313 | 19,978 [45] | 662,116 | 4.1% | 682,094 |

| Belgium | 10,403,951 | 85,990 [46] | 515,939 | 5.8% | 601,929 |

| Romania | 22,246,862 | 544,531 | 2.4% | 544,531 | |

| Sweden | 9,045,389 | 101,472 [47] | 442,601 | 6% | 544,073 |

| Australia | 21,007,310 | 106,517 [48] | 374,571 [49] | 2.3% | 481,088 [50] |

| Poland | 38,500,696 | 316,104 | 0.8% | 316,104 | |

| Austria | 8,205,533 | 267,177 | 3.3% | 267,177 | |

| Ivory Coast | 20,179,602 | 235,806 [51] | 1.2% | 235,806 | |

| Algeria | 33,769,669 | 223,000 [52] | 0.7% | 223,379 | |

| Denmark | 5,484,723 | 219,003 | 4% | 219,003 | |

| Israel | 7,112,359 | 130,000 [53] | 45,231 | 2.5% | 175,231 [54] |

| Switzerland | 7,581,520 | 123,000 [55] | 14,420 | 1.7% [56] | 137,420 |

| Japan | 127,288,419 | 76,565 [57] | 60,000 | 0.1% | 136,565 |

| Bulgaria | 7,262,675 | 133,910 | 1.8% | 133,910 | |

| Belize | 301,270 | 106,795 [58] | 21,848 | 42.7% | 128,643 [59] |

| Netherlands Antilles | 223,652 | 10,699 | 114,835 | 56.1% | 125,534 |

| Ireland | 4,156,119 | 123,591 | 3% | 123,591 | |

| Senegal | 12,853,259 | 101,455 | 0.8% | 101,455 | |

| Greece | 10,722,816 | 86,742 | 0.8% | 86,742 | |

| Finland | 5,244,749 | 85,586 | 1.6% | 85,586 | |

| Hungary | 9,930,915 | 85,034 | 0.9% | 85,034 | |

| Aruba | 100,018 | 6,800 | 68,602 | 75.3% | 75,402 |

| Croatia | 4,491,543 | 73,656 | 1.6% | 73,656 | |

| Andorra | 84,484 | 29,907 [60] | 25,356 | 68.7% [61] | 58,040 |

| Slovakia | 5,455,407 | 43,164 | 0.8% | 43,164 | |

| Norway | 4,644,457 | 12,573 | 23,677 | 0.8% | 36,250 |

| New Zealand | 4,173,460 | 21,645 [62] | 0.5% | 21,645 | |

| Guam | 154,805 | 19,092 | 12.3% | 19,092 | |

| Virgin Islands | 108,612 | 16,788 | 15.5% | 16,788 | |

| Russia | 140,702,094 | 3,320 | 13,122 | 0.01% | 16,442 |

| China | 1,345,751,000 | 2,292[63] | 12,835 | 0.001124% | 15,127 |

| Lithuania | 3,565,205 | 13,943 | 0.4% | 13,943 | |

| Gibraltar | 27,967 | 13,857 | 49.5% | 13,857 | |

| Cyprus | 792,604 | 1.4% | 11,044 | ||

| Turkey | 71,892,807 | 380 | 8,000 [64] | 0.01% | 8,380 |

| Jamaica | 2,804,322 | 8,000 | 0.3% | 8,000 | |

| Luxembourg | 486,006 | 3,000 | 4,344 | 1.5% | 7,344 |

| Malta | 403,532 | 6,458 | 1.6% | 6,458 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1,047,366 | 4,100 | 0.4% | 4,100 | |

| Western Sahara | 513,000 [65] | n.a. [66] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Other immigrants in the E.U. | 1,399,531 [67] | 1,399,531 | |||

| Other students of Spanish | 2,895,562 [68] | 2,895,562 | |||

| Total: | 424,910,677 | 87,118,994 | 512,029,671 |

Hispanosphere

It is estimated that the combined total number of Spanish speakers is between 470 and 500 million, making it the third most spoken language by total number of speakers (after Chinese, and English). Spanish is the second most-widely spoken language in terms of native speakers.[69][70] Global internet usage statistics for 2007 show Spanish as the third most commonly used language on the Internet, after English and Chinese. [71]

Europe

In Europe, Spanish is an official language of Spain, the country after which it is named and from which it originated. It is widely spoken in Gibraltar, though English is the official language.[72] It is the most spoken language in Andorra, though Catalan is the official language.[73][74] It is also spoken by small communities in other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, and Germany.[75] Spanish is an official language of the European Union. In Switzerland, Spanish is the mother tongue of 1.7% of the population, representing the largest minority after the 4 official languages of the country.[76]

Spain

In Spain and in some parts of the Spanish speaking world, but not all, it is rare to use the term español (Spanish) to refer to this language, even when contrasting it with languages such as French and English. Rather, people call it castellano (Castilian), that is, the language of the Castile region, when contrasting it with other languages spoken in Spain such as Galician, Basque, and Catalan. In this manner, the Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term [castellano] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) to define the official language of the whole Spanish State, as opposed to [las demás lenguas españolas] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (lit. the rest of the Spanish languages). Article III reads as follows:

[El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. (…) Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas…] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. (…) The rest of the Spanish languages shall also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities…

However, to some in other linguistic regions, this is considered as demeaning to them and they will therefore use the term castellano exclusively.

The name castellano (Castilian), which refers directly to the origins of the language and the sociopolitical context in which it was introduced in the Americas, is preferred particularly in the Spanish regions where other languages are spoken (Catalonia, Basque Country, Valencian Community, Balearic Islands and Galicia) as well as in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela, instead of español, which is more commonly used to refer to the language as a whole in the rest of Latin America and Spain.

There is some controversy in Spain about the name of the language, which is a part of a greater controversy about Catalan, Basque and Galician nationalisms.

Africa

In Africa, Spanish is official in Equatorial Guinea (co-official with French and Portuguese), as well as an official language of the African Union. Today, in Western Sahara, an unknown number of Sahrawis are able to read and write in Spanish,and several thousands have received university education in foreign countries as part of aid packages (mainly in Cuba and Spain). In Equatorial Guinea, Spanish is the predominant language when native and non-native speakers (around 500,000 people) are counted, while Fang is the most spoken language by number of native speakers.[77][78] It is also spoken in the Spanish cities in continental North Africa (Ceuta and Melilla) and in the autonomous community of Canary Islands (143,000 and 1,995,833 people, respectively). Within Northern Morocco, a former Franco-Spanish protectorate that is also geographically close to Spain, approximately 20,000 people speak Spanish as a second language.[79] It is spoken by some communities of Angola, because of the Cuban influence from the Cold War, and in Nigeria by the descendants of Afro-Cuban ex-slaves.

Asia

During Spanish control, it was an official language of the Philippines, until the change of Constitution in 1973. During most of the colonial period it was the language of government, trade and education, and spoken mainly by Spaniards and mestizos as a first language and more significantly as a second language by more than half of the indigenous population . However, by the mid 19th century a free public school system in Spanish was established throughout the islands, which increased the numbers of Spanish speakers. Following the U.S. occupation and administration of the islands, the strong Spanish influence amongst the Philippine population proved to be a major foe against the imposition of English by the American government, especially after the 1920s. The US authorities' conducted a campaign of solidifying English as the medium of instruction in schools, universities, and public spaces and prohibited the use of Spanish in media and educational institutions which gradually reduced the importance of the language generation after generation. After the country became independent in 1946, Spanish remained an official language along with English and Tagalog-based Filipino. However, the language lost its official status in 1973 during the Ferdinand Marcos administration. Under the Corazón Aquino administration which took office in 1986, the mandatory teaching of Spanish in colleges and universities was also stopped, and thus, younger generations of Filipinos have little or no knowledge of Spanish. The Spanish language retains a large influence in local languages, with many words coming from or being derived from European Spanish and Mexican Spanish, due to the control of the islands by Spain through Mexico City.[80] As of the 1990 Philippine census, only 2,660 people were reported to speak Spanish as a first language, with most speakers residing in Manila.[81] Moreover, close to four million people speak Spanish as a second language to date.

Spanish has made significant contributions to various Philippine languages such as Tagalog, Cebuano and other indigenous dialects and tongues. One of the 170 languages in the Philippines is a Spanish-based creole called Chavacano, spoken in majority by people (ca. 750 000) from the Zamboanga area. Though the indigenous grammatical structure of the national language was retained, over 5000 Spanish loanwords have found their way into the vocabulary of Filipino. Since 2009 Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, a fluent Spanish speaker and current President of the Philippines has ordered the re-establishment of Spanish in the education system plus there is now the daily programme "Filipinas Ahora Mismo" presented by Bon Vivar, produced in Spanish and broadcast on Radio Pilipinas.

Oceania

Among the countries and territories in Oceania, Spanish is also spoken in Easter Island, a territorial possession of Chile. The U.S. Territories of Guam and Northern Marianas, and the independent states of Palau, Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia all once had Spanish speakers, since the Marianas and the Caroline Islands were Spanish colonial possessions until the late 19th century (see Spanish-American War), but Spanish has since been forgotten. It now only exists as an influence on the local native languages and is spoken by Hispanic American resident populations.

America

Latin America

Most Spanish speakers are in Latin America; of all countries with a majority of Spanish speakers, only Spain and Equatorial Guinea are outside the Americas. Mexico has the most native speakers of any country. Nationally, Spanish is the official language—either de facto or de jure—of Argentina, Bolivia (co-official with Quechua and Aymara), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico , Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay (co-official with Guaraní[82]), Peru (co-official with Quechua and, in some regions, Aymara), Uruguay, and Venezuela. Spanish is also the official language (co-official with English) in the U.S. commonwealth of Puerto Rico.[83]

Spanish has no official recognition in the former British colony of Belize; however, per the 2000 census, it is spoken by 43% of the population.[84][85] Mainly, it is spoken by the descendants of Hispanics who have been in the region since the 17th century; however, English is the official language.[86]

Spain colonized Trinidad and Tobago first in 1498, introducing the Spanish language to the Carib people. Also the Cocoa Panyols, laborers from Venezuela, took their culture and language with them; they are accredited with the music of "Parang" ("Parranda") on the island. Because of Trinidad's location on the South American coast, the country is greatly influenced by its Spanish-speaking neighbors. A recent census shows that more than 1 500 inhabitants speak Spanish.[87] In 2004, the government launched the Spanish as a First Foreign Language (SAFFL) initiative in March 2005.[88] Government regulations require Spanish to be taught, beginning in primary school, while thirty percent of public employees are to be linguistically competent within five years.[87]

Spanish is important in Brazil because of its proximity to and increased trade with its Spanish-speaking neighbors, and because of its membership in the Mercosur trading bloc.[89] In 2005, the National Congress of Brazil approved a bill, signed into law by the President, making Spanish language teaching mandatory in both public and private secondary schools in Brazil.[90] In many border towns and villages (especially in the Uruguayan-Brazilian and Paraguayan-Brazilian border areas), a mixed language known as Portuñol is spoken.[91]

United States

In the 2006 census, 44.3 million people of the U.S. population were Hispanic or Latino by origin;[92] 34 million people, 12.2 percent, of the population more than five years old speak Spanish at home.[93] Spanish has a long history in the United States because many south-western states and Florida were part of Mexico and Spain, and it recently has been revitalized by Hispanic immigrants. Spanish is the most widely taught language in the country after English. Although the United States has no formally designated "official languages," Spanish is formally recognized at the state level in various states besides English; in the U.S. state of New Mexico for instance, 40% of the population speaks the language. It also has strong influence in metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, Miami, San Antonio, New York City, and in the last decade, the language has rapidly expanded in Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Charlotte, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Phoenix, Richmond, Washington, DC, and other major Sun-Belt cities. Spanish is the dominant spoken language in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory. With a total of 33,701,181 Spanish (Castilian) speakers, according to US Census Bureau,[94] the U.S. has the world's second-largest Spanish-speaking population.[95] Spanish ranks second, behind English, as the language spoken most widely at home.[96]

Repeated Vomiting

While all Spanish dialects use the same written standard, there are important variations spoken among the regions of Spain and throughout Spanish-speaking America. One major phonological difference between Castilian, broadly speaking, the dialects spoken in northern Spain, and the dialects of southern Spain and all the Latin American dialects of Spanish, is the absence of a voiceless dental fricative (/θ/ as in English thing) in the latter.[97] In Spain, the Castilian dialect is commonly regarded as the standard variety used on radio and television,[98][99][100][101], although attitudes towards southern dialects have changed significantly in the last 50 years. In addition to variations in pronunciation, minor lexical and grammatical differences exist. For example, [[[Loísmo|loísmo]]] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is the use of slightly different pronouns and differs from the standard.

The variety with the most speakers is Mexican Spanish. It is spoken by more than the twenty percent of the Spanish speakers (107 millions of the total 494 millions, according to the table above). One of its main features is the reduction or loss of the unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with the sound /s/.[102][103] It can be the case that the words: pesos, pesas, and peces are pronounced the same ['pesə̥s].

Farting Technique

Spanish has three second-person singular pronouns: [tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [usted] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), and [vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). The use of the pronoun [vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and/or its verb forms is called [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

How to Drink Someone's Fart

[Vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is the subject form [(vos decís)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [you say] and object of a preposition (a vos digo) [to you I say], while "os" is the direct object form [(os vi)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [I saw you (all)] and indirect object without express preposition [(os digo)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [I say to you (all)].[104]

Since vose is historically the 2nd-person plural, verbs are conjugated as such despite the fact the word now refers to a single person:

«Han luchado, añadió dirigiéndose a Tarradellas, [...] por mantenerse fieles a las instituciones que vos representáis» (GaCandau Madrid-Barça [Esp. 1996]).

The possessive form is [vuestro] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help): [Admiro vuestra valentía, señora] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Adjectives, when used in conjunction with vos, do not agree with the pronoun but instead with the real referents in gender and number: [Vos, don Pedro, sois caritativo; Vos, bellas damas, sois ingeniosas] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).[104]

Two main types of [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) may be distinguished: reverential and American dialectal. In archaic solemn usage, [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) expressed special reverence and could be used to address both the second person singular and the second person plural. In contrast, the more commonly known American form of [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is always used to address only one speaker and implies closeness and familiarity.[104] Unlike the first type, the second one need not involve vos and may instead be expressed simply in the use of the plural form of the verb (even in combination with the pronoun tú).

The pronominal voseo employs the use of [vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as a pronoun to replace [tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and [de ti] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), which are second-person singular informal.

[104]

- As a subject [vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) employs: [«Puede que vos tengás razón» (Herrera Casa [Ven. 1985])] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) instead of [«Puede que tú tengas razón»] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- As a vocative: [«¿Por qué vos la tenés contra Alvaro Arzú ?» (Prensa [Guat.] 3.4.97)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) instead of [«¿Por qué tú la tienes contra Alvaro Arzú?»] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- As a term of preposition: [«Cada vez que sale con vos, se enferma» (Penerini Aventura [Arg. 1999])] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) instead of [«Cada vez que sale contigo, se enferma»] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- And as a term of comparison: [«Es por lo menos tan actor como vos» (Cuzzani Cortés [Arg. 1988])] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) instead of [«Es por lo menos tan actor como tú»] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

[104]

However, for the [pronombre átono ] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)(that which uses the pronominal verbs and its complements without preposition) and for the possessive, they employ the forms of [tuteo (te, tu, and tuyo)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), respectively: [«Vos te acostaste con el tuerto» (Gené Ulf [Arg. 1988]); «Lugar que odio [...] como te odio a vos» (Rossi María [C. Rica 1985]); «No cerrés tus ojos» (Flores Siguamonta [Guat. 1993]).] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) In other words, in the previous examples the authors conjugate the pronoun subject [vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) with the pronominal verbs and its complements of [tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).[104]

The verbal [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) consists of the use of the second person plural, more or less modified, for the conjugated forms of the second person singular: [vos vivís, vos comés] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). The verbal paradigm of [voseante] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is characterized by its complexity. On the one hand, it affects, to a distinct extent, each verbal tense. On the other hand, it varies in functions of geographic and social factors and not all the forms are accepted in cultured norms.[104]

Extension in Latin America

[Vos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is used extensively as the primary spoken form of the second-person singular pronoun, although with wide differences in social consideration. Generally, it can be said that there are zones of exclusive use of [tuteo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in the following areas: almost all of Mexico, the West Indies, Panama, the majority of Peru and Venezuela, Coastal Ecuador and; the Atlantic coast of Colombia.

They alternate [tuteo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as a cultured form and [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as a popular or rural form in: Bolivia, north and south of Peru, Andean Ecuador, small zones of the Venezuelan Andes, a great part of Colombia, and the oriental border of Cuba.

[Tuteo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) exists as an intermediate formality of treatment and [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as a familiar treatment in: Chile, the Venezuelan state of Zulia, the Pacific coast of Colombia, Central America, and the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas.

Areas of generalized [voseo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) include Argentina, Costa Rica, Bolivia (east), El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Uruguay and the Colombian region of Antioquia.

[104]

Ustedes

Spanish forms also differ regarding second-person plural pronouns. "Usted" (Ud.) was initially the written abbreviation of "vuestra merced" (your grace). The Spanish dialects of Latin America have only one form of the second-person plural for daily use, [ustedes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (formal or familiar, as the case may be, though [vosotros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) non-formal usage can sometimes appear in poetry and rhetorical or literary style). In Spain there are two forms — [ustedes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (formal) and [vosotros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (familiar). The pronoun [vosotros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is the plural form of [tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in most of Spain, but in the Americas (and in certain southern Spanish cities such as Cádiz and in the Canary Islands) it is replaced with [ustedes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). It is notable that the use of [ustedes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) for the informal plural "you" in southern Spain does not follow the usual rule for pronoun–verb agreement; e.g., while the formal form for "you go", [ustedes van] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), uses the third-person plural form of the verb, in Cádiz or Seville the informal form is constructed as [ustedes vais] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), using the second-person plural of the verb. In the Canary Islands, though, the usual pronoun–verb agreement is preserved in most cases.

Vocabulary

Some words can be different, even significantly so, in different Hispanophone countries. Most Spanish speakers can recognize other Spanish forms, even in places where they are not commonly used, but Spaniards generally do not recognize specifically American usages. For example, Spanish mantequilla, aguacate and albaricoque (respectively, 'butter', 'avocado', 'apricot') correspond to manteca, palta, and damasco, respectively, in Argentina, Chile (except manteca), Paraguay, Peru (except manteca and damasco), and Uruguay. The everyday Spanish words coger ('to catch'), pisar ('to step on') and concha ('seashell') are considered extremely rude in parts of Latin America, where the meaning of coger and pisar is also "to have sex" and concha means "vulva". The Puerto Rican word for "bobby pin" (pinche) is an obscenity in Mexico, but in Nicaragua simply means "stingy", and in Spain refers to a chef's helper. Other examples include taco, which means "swearword" (among other meanings) in Spain and "traffic" in Chile, but is known to the rest of the world as a Mexican dish. Pija in many countries of Latin America and Spain itself is an obscene slang word for "penis", while in Spain the word also signifies "posh girl" or "snobby". Coche, which means "car" in Spain, central Mexico and Argentina, for the vast majority of Spanish-speakers actually means "baby-stroller", while carro means "car" in some Latin American countries and "cart" in others, as well as in Spain. Papaya is the slang term in Cuba for "vagina" therefore in Cuba when referring to the actual fruit Cubans call it fruta bomba instead.[105][106]

Royal Spanish Academy

The [Real Academia Española] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Royal Spanish Academy), together with the 21 other national ones (see Association of Spanish Language Academies), exercises a standardizing influence through its publication of dictionaries and widely respected grammar and style guides.[citation needed] Because of influence and for other sociohistorical reasons, a standardized form of the language (Standard Spanish) is widely acknowledged for use in literature, academic contexts and the media. [citation needed]

Spanish is closely related to the other West Iberian Romance languages: Asturian, Galician, Ladino, Leonese and Portuguese. Catalan, an East Iberian language which exhibits many Gallo-Romance traits, is more similar to Occitan to the east than to Spanish or Portuguese.

Spanish and Portuguese have similar grammars and vocabularies as well as a common history of Arabic influence while a great part of the peninsula was under Islamic rule (both languages expanded over Islamic territories). Their lexical similarity has been estimated as 89%.[107] See Differences between Spanish and Portuguese for further information.

Judaeo-Spanish

Judaeo-Spanish (also known as Ladino),[108] which is essentially medieval Spanish and closer to modern Spanish than any other language, is spoken by many descendants of the Sephardi Jews who were expelled from Spain in the 15th century.[108] Therefore, it has somewhat the same relationship to Spanish as Yiddish does to German. Ladino speakers are currently almost exclusively Sephardi Jews, with family roots in Turkey, Greece or the Balkans: current speakers mostly live in Israel and Turkey, and the United States, with a few pockets in Latin America.[108] It lacks the Native American vocabulary which was influential during the Spanish colonial period, and it retains many archaic features which have since been lost in standard Spanish. It contains, however, other vocabulary which is not found in standard Castilian, including vocabulary from Hebrew, French, Greek and Turkish, and other languages spoken where the Sephardim settled.

Judaeo-Spanish is in serious danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly as well as elderly olim (immigrants to Israel) who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. However, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardi communities, especially in music. In the case of the Latin American communities, the danger of extinction is also due to the risk of assimilation by modern Castilian.

A related dialect is Haketia, the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco. This too tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region.

Vocabulary comparison

Spanish and Italian share a similar phonological system. At present, the lexical similarity with Italian is estimated at 82%.[107] The lexical similarity with Portuguese is greater at 89%. Mutual intelligibility between Spanish and French or Romanian is lower (lexical similarity being respectively 75% and 71%[107]): comprehension of Spanish by French speakers who have not studied the language is low at an estimated 45% – the same as English. The common features of the writing systems of the Romance languages allow for a greater amount of interlingual reading comprehension than oral communication would.

| Latin | Spanish | Galician | Portuguese | Astur-Leonese | Catalan | Italian | French | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [nos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (alterum) | [nosotros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nós] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nós] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (outros)¹ | [nós, nosotros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nosaltres] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [noi] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (altri)² | [nous] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (autres)³ | [noi] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | we |

| [fratrem germānum (acc.)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (lit. "true brother", i.e. not a cousin) | [hermano] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [irmán] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [irmão] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [hermanu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [germà] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [fratello] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [frère] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [frate] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | brother |

| [dies Martis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Classical)

[feria tertia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Ecclesiastical) |

[martes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [martes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [terça-feira] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [martes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [dimarts] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [martedì] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mardi] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [marţi] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | Tuesday |

| [cantiō (nem, acc.), canticum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [canción] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [canción] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/cançom4 | [canção, cântico] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [canción] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [cançó] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [canzone] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [chanson] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [cântec] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | song |

| [magis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [plus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [más] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (archaically also [plus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[máis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mais] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (archaically also [chus/plus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[más] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [més] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (archaically also [pus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[più] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [plus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mai/plus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | more |

| [manum sinistram (acc.)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mano izquierda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (also [mano siniestra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[man esquerda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mão esquerda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (also [sinistra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and archaically also [sẽestra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[mano esquierda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mà esquerra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mano sinistra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [main gauche] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [mâna stângă] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | left hand |

| [nihil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [nullam rem natam (acc.)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (lit. "no thing born") |

[nada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/[ren] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (neca and nula rés in some expressions; archaically also [rem] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) |

[nada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [res] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [niente] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/[nulla] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [rien] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/[nul] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | [nimic/nul] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | nothing |

1. also [nós outros] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in early modern Portuguese (e.g. The Lusiads)

2. [noi altri] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Southern Italian dialects and languages

3. Alternatively [nous autres] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

4. Depending on the written norm used. See Reintegracionismo

Characterization

A defining feature of Spanish was the diphthongization of the Latin short vowels e and o into ie and ue, respectively, when they were stressed. Similar sound changes are found in other Romance languages, but in Spanish, they were significant. Some examples:

- Lat. [petram] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > Sp. [piedra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), It. [pietra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Fr. [pierre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Rom. [piatrǎ] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Port./Gal. [pedra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ast. [piedra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Cat. [pedra] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "stone".

- Lat. [moritur] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > Sp. [muere] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), It. [muore] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Fr. [meurt] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) / [muert] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Rom. [moare] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Port./Gal. [morre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ast. [muerre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Cat. [mor] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "die".

Peculiar to early Spanish (as in the Gascon dialect of Occitan, and possibly due to a Basque substratum) was the mutation of Latin initial f- into h- whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongate. Compare for instance:

- Lat. [filium] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > It. [figlio] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Port. [filho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Gal. [fillo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ast. [fíu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Fr. [fils] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Cat. [fill] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Occitan [filh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (but Gascon [hilh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) Sp. [hijo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (but Ladino [fijo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help));

- Lat. [fabulari] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > Lad. [favlar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Port./Gal. [falar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ast. [falar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Sp. [hablar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help);

- but Lat. [focum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > It. [fuoco] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Port./Gal. [fogo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ast. [fueu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Cat. [foc] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Sp./Lad. [fuego] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

Some consonant clusters of Latin also produced characteristically different results in these languages, for example:

- Lat. [clamare] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), acc. [flammam] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [plenum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > Lad. [lyamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [flama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [pleno] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Sp. [llamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [llama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [lleno] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). However, in Spanish there are also the forms [clamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [flama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [pleno] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Port. [chamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [chama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [cheio] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Gal. [chamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [chama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [cheo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Ast. [llamar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [llama] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [llenu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

- Lat. acc. [octo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [noctem] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [multum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) > Lad. [ocho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [noche] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [muncho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Sp. [ocho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [noche] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [mucho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Port. [oito] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [noite] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [muito] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Gal. [oito] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [noite] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [moito] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Ast. [ocho] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [nueche] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [munchu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

By the 16th century, the consonant system of Spanish underwent the following important changes that differentiated it from neighboring Romance languages such as Portuguese and Catalan:

- Initial /f/, when it had evolved into a vacillating /h/, was lost in most words (although this etymological h- is preserved in spelling and in some Andalusian and Caribbean dialects it is still aspirated in some words).

- The consonant written ‹u› or ‹v› (in Latin, this was [w], at the time of the merger it may have been a bilabial fricative /β/) merged with the consonant written ‹b› (a voiced bilabial plosive, /b/). In contemporary Spanish, there is no difference between the pronunciation of orthographic ‹b› and ‹v›, excepting emphatic pronunciations that cannot be considered standard or natural.

- The voiced alveolar fricative /z/ which existed as a separate phoneme in medieval Spanish merged with its voiceless counterpart /s/. The phoneme which resulted from this merger is currently spelled s.

- The voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ merged with its voiceless counterpart /ʃ/, which evolved into the modern velar sound /x/ by the 17th century, now written with j, or g before e, i. Nevertheless, in most parts of Argentina and in Uruguay, y and ll have both evolved to /ʒ/ or /ʃ/.

- The voiced alveolar affricate /d͡z/ merged with its voiceless counterpart /t͡s/, which then developed into the interdental /θ/, now written z, or c before e, i. But in Andalusia, the Canary Islands and the Americas this sound merged with /s/ as well. See Ceceo, for further information.

The consonant system of Medieval Spanish has been better preserved in Ladino and in Portuguese, neither of which underwent these shifts

Writing system

Spanish is written in the Latin alphabet, with the addition of the character ‹ñ› ([eñe] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), representing the phoneme /ɲ/, a letter distinct from ‹n›, although typographically composed of an ‹n› with a tilde) and the digraphs ‹ch› ([che] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), representing the phoneme /t͡ʃ/) and ‹ll› ([elle] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), representing the phoneme /ʎ/). However, the digraph ‹rr› ([erre fuerte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), 'strong r", [erre doble] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), 'double r', or simply [erre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), which also represents a distinct phoneme /r/, is not similarly regarded as a single letter. Since 1994 ‹ch› and ‹ll› have been treated as letter pairs for collation purposes, though they remain a part of the alphabet. Words with ‹ch› are now alphabetically sorted between those with ‹ce› and ‹ci› , instead of following ‹cz› as they used to. The situation is similar for ‹ll›.[109][110]

Thus, the Spanish alphabet has the following 29 letters:

- a, b, c, ch, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, ll, m, n, ñ, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z.[111]

The letters "k" and "w" are used only in words and names coming from foreign languages (kilo, folklore, whiskey, William, etc.).

With the exclusion of a very small number of regional terms such as México (see Toponymy of Mexico), pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling. Under the orthographic conventions, a typical Spanish word is stressed on the syllable before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including ‹y›) or with a vowel followed by ‹n› or ‹s›; it is stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an acute accent on the stressed vowel.

The acute accent is used, in addition, to distinguish between certain homophones, especially when one of them is a stressed word and the other one is a clitic: compare [el] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('the', masculine singular definite article) with [él] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('he' or 'it'), or [te] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('you', object pronoun), [de] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (preposition 'of'), and [se] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (reflexive pronoun) with [té] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('tea'), [dé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('give' [formal imperative/third-person present subjunctive]) and [sé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('I know' or imperative 'be').

The interrogative pronouns ([qué] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [cuál] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [dónde] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [quién] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), etc.) also receive accents in direct or indirect questions, and some demonstratives ([ése] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [éste] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), [aquél] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), etc.) can be accented when used as pronouns. The conjunction [o] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('or') is written with an accent between numerals so as not to be confused with a zero: e.g., [10 ó 20] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) should be read as [diez o veinte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) rather than [diez mil veinte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ('10.020'). Accent marks are frequently omitted in capital letters (a widespread practice in the days of typewriters and the early days of computers when only lowercase vowels were available with accents), although the RAE advises against this.

When ‹u› is written between ‹g› and a front vowel (‹e i›), it indicates a "hard g" pronunciation. A diaeresis (‹ü›) indicates that it is not silent as it normally would be (e.g., cigüeña, 'stork', is pronounced [θiˈɣweɲa]; if it were written ‹cigueña›, it would be pronounced [θiˈɣeɲa].

Interrogative and exclamatory clauses are introduced with Inverted question and exclamation marks (‹¿› and ‹¡›, respectively).

Phonology

The phonemic inventory listed in the following table includes phonemes that are preserved only in some dialects, other dialects having merged them (such as yeísmo); these are marked with an asterisk (*). Sounds in parentheses are allophones. Where symbols appear in pairs, the symbol to the right represents a voiced consonant.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

| Stop | p b | t̪ d̪ | t͡ʃ ɟ͡ʝ | k ɡ | ||

| Fricative | (β̞) | f (v) | *θ (ð̞) | s (z) | (ʝ) | x (ɣ˕) |

| Trill | r | |||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||

| Lateral | l | *ʎ | ||||

Lexical stress

Spanish is a syllable-timed language, so each syllable has the same duration regardless of stress.[113][114] Stress most often occurs on any of the last three syllables of a word, with some rare exceptions at the fourth last or earlier syllables. The tendencies of stress assignment are as follows:[115]

- In words ending in vowels and /s/, stress most often falls on the penultimate syllable.

- In words ending in all other consonants, the stress more often falls on the last syllable.

- Preantepenultimate stress (stress on the syllable that comes three before the last in a word) occurs rarely and only in words like guardándoselos ('saving them for him/her') where clitics follow certain verbal forms.

In addition to the many exceptions to these tendencies, there are numerous minimal pairs which contrast solely on stress such as sábana ('sheet') and sabana ('savannah'), as well as límite ('boundary'), limite ('[that] he/she limits') and limité ('I limited').

An amusing example of the significance of intonation in Spanish is the phrase ¿Cómo?; ¿cómo como? ¡Como como como! (What do you mean, how do I eat? I eat the way I eat!).

Grammar

Spanish is a relatively inflected language, with a two-gender system and about fifty conjugated forms per verb, but limited inflection of nouns, adjectives, and determiners. (For a detailed overview of verbs, see Spanish verbs and Spanish irregular verbs.)

It is right-branching, uses prepositions, and usually, though not always, places adjectives after nouns - as most other Romance languages. Its syntax is generally Subject Verb Object, though variations are common. It is a pro-drop language (or null subject language), that is, it allows the deletion of pronouns which are pragmatically unnecessary, and is verb-framed.

Samples

| English | Spanish | IPA phonemic transcription (abstract phonemes) 1 |

IPA phonetic transcription (actual sounds) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish |

[Español] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/es.paˈɲol/ |

[e̞s̺.päˈɲo̞l] [e̞s̻.päˈɲo̞l] |

| (Castilian) Spanish |

[castellano] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/kas.teˈʎa.no/ /kas.teˈʝa.no/ |

[käs̪.t̪e̞ˈʎä.no̞] [käs̪.t̪e̞ˈʝ̞ä.no̞] [käh.t̪e̞ˈʒä.no̞] |

| Yes |

[Sí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈsi/ |

[ˈs̺i] [ˈs̻i] |

| No | [No] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈno/ | [ˈno̞] |

| Hello | [Hola] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈo.la/ | [ˈo̞.lä] |

| How are you? | [¿Cómo estás (tú)?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (informal) [¿Cómo está (usted)?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (formal) |

/ˈko.mo esˈtas/ |

[ˈko̞.mo̞ e̞s̪ˈt̪äs̺] [ˈko̞.mo̞ e̞s̪ˈt̪äs̻] [ˈko̞.mo̞ ɛhˈt̪æ̞h] |

| Good morning |

[Buenos días] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈbue.nos ˈdi.as/ |

[ˈbwe̞.no̞z̪ ˈð̞i.äs̺] [ˈbwe̞.no̞z̪ ˈð̞i.äs̻] [ˈbwɛ.nɔh ˈð̞i.æ̞h] |

| Good afternoon/evening |

[Buenas tardes] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈbue.nas ˈtar.des/ 3 |

[ˈbwe̞.näs̪ ˈt̪äɾ.ð̞e̞s̺] [ˈbwe̞.näs̪ ˈt̪äɾ.ð̞e̞s̻] [ˈbwɛ.næ̞h ˈt̪æ̞ɾ.ð̞ɛh] |

| Good night |

[Buenas noches] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈbue.nas ˈno.tʃes/ |

[ˈbwe̞.näs̺ ˈno̞.tʃe̞s̺] [ˈbwe̞.näs̻ ˈno̞.tʃe̞s̻] [ˈbwɛ.næ̞h ˈnɔ.tʃɛh] |

| Goodbye |

[Adiós] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/aˈdios/ |

[äˈð̞jo̞s̺] [äˈð̞jo̞s̻] [æ̞ˈð̞jɔh] |

| Please | [Por favor] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /por faˈbor/ 3 | [po̞r fäˈβ̞o̞r] |

| Thank you |

[Gracias] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈɡra.θias/ 3 /ˈɡra.sias/ 3 |

[ˈɡɾä.θjäs̺] [ˈɡɾä.s̻jäs̻] [ˈɡɾæ̞.s̻jæ̞h] |

| Excuse me |

[Perdón] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/perˈdon/ 3 |

[pe̞ɾˈð̞õ̞n] [pe̞ɾˈð̞õ̞] |

| I am sorry |

[Lo siento] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/lo ˈsien.to/ 3 |

[lo̞ ˈs̺jẽ̞n̪.t̪o̞] [lo̞ ˈs̻jẽ̞n̪.t̪o̞] |

| Hurry! (informal) |

[¡Date prisa!] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈda.te ˈpri.sa/ 3 |

[ˈd̪ä.t̪e̞ ˈpɾi.s̺ä] [ˈd̪ä.t̪e̞ ˈpɾi.s̻ä] |

| Because | [Porque] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈpor.ke/ 3 | [ˈpo̞r.ke̞] |

| Why? | [¿Por qué?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /por ˈke/ 3 | [po̞r ˈke̞] |

| Who? |

[¿Quién?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈkien/ 3 |

[ˈkjẽ̞n] [ˈkjẽ̞] |

| What? | [¿Qué?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈke/ | [ˈke̞] |

| When? | [¿Cuándo?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈkuan.do/ 3 | [ˈkwãn̪.d̪o̞] |

| Where? | [¿Dónde?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈdon.de/ 3 | [ˈdõ̞n̪.d̪e̞] |

| How? | [¿Cómo?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈko.mo/ | [ˈko̞.mo̞] |

| How much? | [¿Cuánto(-a)?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /ˈkuan.to/ 3 | [ˈkwãn̪.t̪o̞] |

| I do not understand | [No entiendo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | /no enˈtien.do/ 3 | [nŏ̞ ẽ̞n̪ˈt̪jẽ̞n̪.d̪o̞] |

| Help me (please) (formal) Help me! (informal) |

[Ayúde(n)me ¡Ayúdame! ] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/aˈʝu.de.me/ /aˈʝu.da.me/ |

[äˈʝ̞u.ð̞e̞.me̞] [äˈʒu.ð̞e̞.me̞] [äˈʝ̞u.ð̞ä.me̞] [äˈʒu.ð̞ä.me̞] |

| Where is the bathroom? |

[¿Dónde está el baño?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈdon.de esˈta el ˈba.ɲo/ 3 |

[ˈdõ̞n̪.d̪e̞ e̞s̪ˈt̪ä ĕ̞l ˈβä.ɲo̞] [ˈdõ̞n̪ d̪ɛhˈt̪ä ĕ̞l ˈβ̞ä.ɲo̞] |

| Do you speak English? (informal) |

[¿Hablas inglés?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈa.blas inˈɡles/ 3 |

[ˈä.β̞läs̺ ĩŋˈɡle̞s̺] [ˈä.β̞läs̻ ĩŋˈɡle̞s̻] [ˈæ̞.β̞læ̞h ĩŋˈɡlɛh] |

| Do you speak English? (formal) |

[¿Habla inglés?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/ˈa.bla inˈɡles/ 3 |

[ˈä.β̞lä̺ ĩŋˈɡle̞s̺] [ˈä.β̞lä̻ ĩŋˈɡle̞s̻] [ˈæ̞.β̞læ̞h ĩŋˈɡlɛh] |

| Cheers! |

[¡Salud!] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

/saˈlud/ |

[s̺aˈluð̞] [s̻aˈlu(ð̞)] |

Spanish Words Hola- Hello Amigo/Amiga- Friend Muchas Gracias- Thank You Por Favor- Please libro- book carro- car Adios- Bye Tu- you Yo- I El- He Ella- She Hermana- Sister Hermano- Brother Esposa- Wife Numero- Number Que hora es?- What time is it?

1 Phonemic representation of the abstract phonological entities (phonemes), 2 phonetic representation of the actual sounds pronounced (phones). In both cases, when several representations are given, the first one corresponds to the dialect in the recording (Castilian with yeísmo) and the rest to several other dialects not in the recording.

3 The nasal and rhotic sounds undergo a certain degree of neutralization and are represented as /n/ and /r/ in phonemic transcription even when the phonetic realization differs from [n] and [r].

See also

Local varieties

|

Asia

|

References

- ^ a b Spanish language total. Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition, ed. M. Paul Lewis 2009

- ^ "Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Crow, John A. (2005). Spain: the root and the flower. University of California Press. p. 151. ISBN 0520244962.

...Which was the first grammar of any modern European tongue.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Thomas, Hugh (2005). Rivers of Gold: the rise of the Spanish empire, from Columbus to Magellan. Random House Inc. p. 78. ISBN 0812970555.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ "La lengua de Cervantes" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de la Presidencia de España. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ UN (2009 estimate)

- ^ Britannica encyclopedia [1]

- ^ eurobarometer (2006), [2] for Europe countries

- ^ Spanish students for countries out of Europe according to Instituto Cervantes 06-07 (There aren't concrete sources about Spanish speakers as a second language except to Europe and Latin America countries).

- ^ Demografía de la lengua española (page 28) to countries with official spanish status.

- ^ CONAPO (2010).

- ^ Population figure for 2008 from U.S. Population in 1990, 2000, and 2008, U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ 34,559,894 legal hispanics older than 5 years old (US Census 2008)+ 8,300,000 illegal immigrants (Pew Hispanic Center 2008, impre.com, ecodiario.eleconomista.es. They aren't new generations of immigrants living in USA as many of the legal immigrants).

- ^ Significant figure about the legal Hispanic population (46,943,613 from a total US population of 304,059,724) Census Bureau 2008

- ^ I Acta Internacional de la Lengua Española (2007): noticias en latinoamericaexterior.com, Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española: elcastellano.org, José Ma. Ansón: noticias elcastellano.org, Jorge Ramos Avalos: univision.com, Vázquez Medel: casamerica.es.

- ^ According to the U.S. census (fundacionsiglo.com fundacionsiglo.com): 3,600,000 in primary school, 3,220,000 in secondary school and 1,000,000 in the University

- ^ INE, (1/1/2009)

- ^ 89.0% speak Spanish as a first language (eurobarometer (2006))

- ^ DANE

- ^ INDEC (2009)

- ^ INE (January, 2010)

- ^ INEI (2010)

- ^ INE (Chile - 2010)

- ^ INEC (January, 2010)

- ^ 50% of 733,000 foreigners in Brazil are from Mercosur (Page 32 ucm.es) + 78,505 spanish immigrants (INE (1/1/2009)).

- ^ elcastellano.org, oei.org.co. More than 1 million of spanish students in the private school and almost 11 million estimated for 2010 in the public school (Instituto Cervantes).

- ^ INE (2010)

- ^ Census 2010 estimation (page 32)

- ^ INE

- ^ According to the Morocco Census of 2004 (hcp.ma)

- ^ ethnologue.com

- ^ According to a survey made in 2005 by CIDOB (realinstitutoelcano.org, afapredesa.org). Between 4 and 7 million speakers (Ammadi, 2002) educacion.es

- ^ 1% of 44,010,619 (population of France older than 15 years in 2005). Source: Eurobarometer 2006. There are 179,678 immigrants from Spain according to INE (1/1/2009)

- ^ 95,10% of the population speaks Spanish (U.S. Census Bureau)

- ^ 59,017 immigrants from Spain (Spanish census 2001) + 48,637 immigrants from Colombia. Open Channels and Colombian consul (1999)

- ^ Ethnologue. There are 2,532 immigrants from Spain accordind toINE (1/1/2009)

- ^ 1,816,773 Spanish + 1,200,000 Spanish creole: Antonio Quilis "La lengua española en Filipinas", 1996 pag.234 cervantesvirtual.com, mepsyd.es (page 23), mepsyd.es (page 249), spanish-differences.com, aresprensa.com. The figure 2,900,000 Spanish speakers, we can find in "Pluricentric languages: differing norms in different nations" (page 45 by R.W.Thompson), or in sispain.org./ More than 2 million Spanish speakers and around 3 million with Chavacano speakers according to "Instituto Cervantes de Manila" (elcastellano.org)

- ^ Britannica Book of the Year 1998 [3]. There are 103,063 immigrants from Spain according to INE (1/1/2009)

- ^ 14,905 Spanish (Census 2001) + 75,000 from Ecuador [4]

- ^ Equatorial Guinea census (2009)

- ^ 13,7% of the population cvc.cervantes.es

- ^ Pages 28 and 23 in Demografía de la lengua española

- ^ PMB Statistics factorhispano.net. Although Canada Census told about 345,345 people who speaks Spanish in 2006, Hispanic organizations claim about 520,260 Hispanics in 2001, and more than 700,000 in 2006 (hispanosencanada.ca, dialogos.ca), and currently there are near 1 million: (tlntv.com, broadcastdialogue.com).

- ^ Spanish (census 2001)

- ^ 1% of 8,598,982 (population of Belgium older than 15 years in 2005). Source: Eurobarometer 2006

- ^ Sweden Census SCB (2002)

- ^ Page 32 of the "Demogeafía de la lengua española". 104,000 according to Britannica Book of the Year 2003

- ^ Page 32 of the "Demografía de la lengua española" + 33,913 students according to Anuario Instituto Cervantes 06-07

- ^ Page 32 of "Demogeafía de la lengua española"

- ^ students according to Anuario Instituto Cervantes 06-07

- ^ Between 150,000 and 200,000 in Tinduf (aprendemas.com) + 48,000 in Wilaya of Oran (page 31 of Demografía de la lengua española)

- ^ 50,000 sefardíes (Britannica Book of the Year 1998)[5] + 80,000 from Iberoamerica[6]

- ^ Pages 34, 35 of the "Demografía de la lengua española".

- ^ Britannica Book of the Year 1998 [7]

- ^ all-about-switzerland.info

- ^ Immigrants from Spanish speaking countries [8]

- ^ Page 32 of Demografía de la lengua española

- ^ Page 32 of Demografía de la lengua española

- ^ 35.4% speak Spanish as a first language www.iea.ad

- ^ www.iea.ad

- ^ New Zealand census (2006)

- ^ Spanish residents in China (INE, 2009)

- ^ Page 37 of theDemografía de la lengua española

- ^ U.N., 2009

- ^ The Spanish 1970 census claims 16.648 Spanish speakers in Western Sahara ( [9]) but probably most of them were people born in Spain who left after the Moroccan annexation

- ^ There are 2,397,380 immigrants from Spain and Latin America according to the page 37 of the "Demografía de la lengua española" (997,849 already counted)

- ^ According to the Instituto Cervantes, there are 14 million of spanish students. But there are already counted sudents from U.S. (6,000,000) because it is considered the current 7,820,000 students, E.U (3,385,000) because they are considered in the eurobarometer figures (demografía del español (page 37), Brazil (1 mill.) with 11 million new students in the public schools, Morocco (58.382) and Phillippines (20,492), Canada (92,853), Australia (33,913), Ivory Coast (235,806), Switzerland (14,420), Japan (60,000), Senegal (101.455), Occ. Sáhara (25,800), Norway (23,677), Russia (13,122) and China (12,835).

- ^ "Most widely spoken Languages in the World". Nations Online. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ^ CIA The World Factbook United States

- ^ "Internet World Users by Language". Miniwatts Marketing Group. 2008.

- ^ CIA World Factbook — Gibraltar

- ^ Andorra — People. MSN Encarta. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "Background Note: Andorra". U.S. Department of State: Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ BBC Education — Languages, Languages Across Europe — Spanish.

- ^ "Switzerland's Four National Languages". all-about-switzerland.info. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ Ethnologue – Equatorial Guinea (2000)

- ^ CIA World Factbook – Equatorial Guinea (Last updated 20 September 2007)

- ^ Morocco.com, The Languages of Morocco.

- ^ 1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, thecorpusjuris.com, retrieved 2008-04-06 (See Article XV, Section 3(3))

- ^ "Languages of the Philippines". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ^ Ethnologue – Paraguay(2000). Guaraní is also the most-spoken language in Paraguay by its native speakers.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Elevates English". the New York Times. 29 January 1993. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ "Population Census 2000, Major Findings" (PDF). Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Budget Management, Belize. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Belize Population and Housing Census 2000

- ^ CIA World Factbook — Belize

- ^ a b Williams, Carol J. (2005-08-30). "Trinidad Says It Needs Spanish to Talk Business". Los Angeles Times. p. A3. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ The Secretariat for The Implementation of Spanish, Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago

- ^ Mercosul, Portal Oficial (Portuguese)

- ^ Pimentel, Carolina (2005-08-08). "Brazil Wants to Pay Foreign Debt with Spanish Classes" (PDF). Brazzil magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ Lipski, John M. (2006). "Too close for comfort? the genesis of "portuñol/portunhol"" (PDF). Selected Proceedings of the 8th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. ed. Timothy L. Face and Carol A. Klee, 1–22. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ U.S. Census Bureau Hispanic or Latino by specific origin.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau 1. Percent of People 5 Years and Over Who Speak Spanish at Home: 2006, U.S. Census Bureau 2. 34,044,945 People 5 Years and Over Who Speak Spanish at Home: 2006

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (2007). "United States. S1601. Language Spoken at Home". 2005-2007 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ El País Template:Es icon

- ^ Template:PDFlink, Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003

- ^ Harris (1969:538)

- ^ Random House Unabridged Dictionary. Random House Inc. 2006.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006.

- ^ Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. MICRA, Inc. 1998.

- ^ Encarta World English Dictionary. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Eleanor Greet Cotton, John M. Sharp (1988) Spanish in the Americas, Volumen 2, pp.154-155, URL

- ^ Lope Blanch, Juan M. (1972) En torno a las vocales caedizas del español mexicano, pp.53 a 73, Estudios sobre el español de México, editorial Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México URL.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Real Academia Española

- ^ 3 Guys From Miami: Fruta Bomba

- ^ Urban Dictionary: papaya

- ^ a b c "Spanish". ethnologue.

- ^ a b c Alfassa, Shelomo (December 1999). "Ladinokomunita". Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas, 1st ed.

- ^ Real Academia Española, Explanation at Spanish Pronto Template:Es icon, Template:En icon

- ^ "Abecedario". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (in Template:Es icon). Real Academia Española. 2005. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Martínez-Celdrán et al. (2003:255)

- ^ Cressey (1978:152)

- ^ Abercrombie (1967:98)

- ^ Eddington (2000:96)

Bibliography

- Abercrombie, David (1967), Elements of General Phonetics, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Cressey, William Whitney (1978), Spanish Phonology and Morphology: A Generative View, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 0878400451

- Eddington, David (2000), "Spanish Stress Assignment within the Analogical Modeling of Language" (PDF), Language, 76 (1): 92–109, doi:10.2307/417394

- Harris, James (1967), "Sound Change in Spanish and the Theory of Markedness", Language, 45 (3): 538–552

- Martínez-Celdrán, Eugenio; Fernández-Planas, Ana Ma.; Carrera-Sabaté, Josefina (2003), "Castilian Spanish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 255–259, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001373

External links

- Template:Es icon Dictionary of the RAE Real Academia Española's official Spanish language dictionary

- Spanish – BBC Languages

- English - Spanish - altogether 260348 entries.

- Spanish evolution from Latin

- Spanish phrasebook on WikiTravel

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of a first Spanish reader by Erwin W. Roessler and Alfred Remy.

Template:Official UN languages Template:Official EU languages

- Spanish language

- Languages of Spain

- Languages of Andorra

- Languages of Argentina

- Languages of Belize

- Languages of Bolivia

- Languages of Chile

- Languages of Colombia

- Languages of Costa Rica

- Languages of the Dominican Republic

- Languages of Ecuador

- Languages of El Salvador

- Languages of Equatorial Guinea

- Languages of Guatemala

- Languages of Honduras

- Languages of Mexico

- Languages of Morocco

- Languages of Nicaragua

- Languages of Panama

- Languages of Paraguay

- Languages of Peru

- Languages of the Philippines

- Languages of the United States

- Languages of Uruguay

- Languages of Venezuela

- Languages of South America