Joseph Stalin

| File:Joseph Stalin.jpg | |

| 1st General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 3 April 1922 – 5 March 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov |

| Premier of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 6 May 1941 – 5 March 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov |

| People's Commissar of Defence of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 19 July 1941 – 25 February 1946 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Semyon Timoshenko |

| Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 25 February 1946 – 3 March 1947 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bulganin |

| Chairman of the State Defense Committee | |

| In office 1941–1945 | |

| People's Commissar of Nationalities | |

| In office 1917–1923 | |

| Prime Minister | Vladimir Lenin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Iosef Besarionis dze Jughashvili 18 December 1878 Gori, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 March 1953 (aged 74) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Soviet Georgian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Signature |  |

Joseph Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili in Georgian or Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in Russian patronymic nomenclature; 18 December 1878 – 5 March 1953) was the first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee from 1922 until his death in 1953. In the years following Lenin's death in 1924, he rose to become the leader of the Soviet Union.

Stalin launched a command economy, replacing the New Economic Policy of the 1920s with Five-Year Plans and launching a period of rapid industrialization and economic collectivization. The upheaval in the agricultural sector disrupted food production, resulting in widespread famine, such as the catastrophic Soviet famine of 1932-1933, known in Ukraine as the Holodomor.[1]

During the late 1930s, Stalin launched the Great Purge (also known as the "Great Terror"), a campaign to purge the Communist Party of people accused of sabotage, terrorism, or treachery; he extended it to the military and other sectors of Soviet society. Targets were often executed, imprisoned in Gulag labor camps or exiled. In the years following, millions of members of ethnic minorities were also deported.[2][3]

In 1939, after failed attempts to establish a collective security system in Europe, Stalin decided to conclude a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, followed by a Soviet invasion of Poland, Finland, the Baltics, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina. After Germany violated the pact in 1941, the Soviet Union joined the Allies to play a primary role in the Axis defeat, at the cost of the largest death toll for any country in the war. Thereafter, contradicting statements at allied conferences,[citation needed] Stalin installed communist governments in most of Eastern Europe, forming the Eastern bloc, behind what was referred to as an "Iron Curtain" of Soviet rule, irking United States and the Western Allies. This launched the long period of antagonism between the Western world, led by the United States, and Stalin's Soviet Union known as the Cold War.

Stalin fostered a cult of personality around him, but after his death, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, denounced his legacy and drove the process of de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union.[4]

Early life

Stalin was born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili on 18 December 1878[5] to a cobbler in the town of Gori, Georgia. At the age of seven, he contracted smallpox, permanently scarring his face. At ten, he began attending church school where the Georgian children were forced to speak Russian. By the age of twelve, two horse-drawn carriage accidents left his left arm permanently damaged. At sixteen, he received a scholarship to a Georgian Orthodox seminary, where he rebelled against the imperialist and religious order. Though he performed well there, he was expelled in 1899 after missing his final exams. The seminary's records suggest he was unable to pay his tuition fees.[6]

Shortly after leaving the seminary, Stalin discovered the writings of Vladimir Lenin and decided to become a Marxist revolutionary, eventually joining Lenin's Bolsheviks in 1903. After being marked by the Okhranka (the Tsar's secret police) for his activities, he became a full-time revolutionary and outlaw. He became one of the Bolsheviks' chief operatives in the Caucasus, organizing paramilitaries, inciting strikes, spreading propaganda and raising money through bank robberies, ransom kidnappings and extortion.

In the summer of 1906, Stalin married Ekaterina Svanidze, who later gave birth to Stalin's first child, Yakov. Stalin temporarily resigned from the party over its ban on bank robberies, masterminded a large raid on a bank shipment resulting in the deaths of 40 people[8] and then fled to Baku, where Ekaterina died of typhus. In Baku, Stalin organized Muslim Azeris and Persians in partisan activities, including the murders of many "Black Hundreds" right-wing supporters of the Tsar, and conducted protection rackets, ransom kidnappings, counterfeiting operations and robberies.

Stalin was captured and sent to Siberia seven times, but escaped most of these exiles. After release from one such exile, in April 1912 in Saint Petersburg, Stalin created the newspaper Pravda from an existing party newspaper. He eventually adopted the name "Stalin", from the Russian word for steel, which he used as an alias and pen name in his published works.

During his last exile, Stalin was conscripted by the Russian army to fight in World War I. He was deemed unfit for service because of his damaged left arm.[9]

Revolution, Civil War, and Polish-Soviet War

Role during the Russian Revolution of 1917

After returning to Saint Petersburg from exile, Stalin began a revolution by ousting Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov as editors of Pravda. He then took a position in favor of supporting Alexander Kerensky's provisional government. However, after Lenin prevailed at the April 1917 Party conference, Stalin and Pravda supported overthrowing the provisional government. At this conference, Stalin was elected to the Bolshevik Central Committee. After Lenin participated in an attempted revolution, Stalin helped Lenin evade capture and, to avoid a bloodbath, ordered the besieged Bolsheviks to surrender.[7]

He smuggled Lenin to Finland and assumed leadership of the Bolsheviks.[7] After the jailed Bolsheviks were freed to help defend Saint Petersburg, in October 1917, the Bolshevik Central Committee voted in favor of an insurrection.[7] On 7 November, from the Smolny Institute, Stalin, Lenin and the rest of the Central Committee coordinated the coup against the Kerensky government - the so-called October Revolution. Kerensky left the capital to rally the Imperial troops at the German front. By 8 November, the Winter Palace had been stormed and Kerensky's Cabinet had been arrested.

Role in the Russian Civil War, 1917–1919

Upon seizing Petrograd, Stalin was appointed People's Commissar for Nationalities' Affairs.[10] Thereafter, civil war broke out in Russia, pitting Lenin's Red Army against the White Army, a loose alliance of anti-Bolshevik forces. Lenin formed a five-member Politburo which included Stalin and Trotsky. In May 1918, Lenin dispatched Stalin to the city of Tsaritsyn. Through his new allies, Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny, Stalin imposed his influence on the military.[10]

Stalin challenged many of the decisions of Trotsky, ordered the killings of many former Tsarist officers in the Red Army and counter-revolutionaries[10][11] and burned villages in order to intimidate the peasantry into submission and discourage bandit raids on food shipments.[10] In May 1919, in order to stem mass desertions on the Western front, Stalin had deserters and renegades publicly executed as traitors.[10]

Role in the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-1921

After their Russian Civil War victory, the Bolsheviks moved to establish a sphere of influence in Central Europe, starting with what became the Polish–Soviet War. As commander of the southern front,[10] Stalin was determined to take the Polish-held city of Lviv. This conflicted with general strategy set by Lenin and Trotsky, whose priority was the capture of Warsaw further north.

Trotsky engaged with Polish commander Władysław Sikorski at the Battle of Warsaw, but Stalin refused to redirect his troops from Lviv to help.[10] Consequently, the battles for both Lviv and Warsaw were lost, and Stalin was blamed. Stalin returned to Moscow in August 1920, where he defended himself and resigned his military commission.[10] At the Ninth Party Conference on 22 September, Trotsky openly criticized Stalin's behavior.[10]

Later in his career, Stalin was to compensate for the disaster of 1920.[12] He would ensure the death of Trotsky, secure Lviv in the Nazi-Soviet pact, execute Polish veterans of the Polish-Soviet War in the Katyn massacre; ensure the failure of the Warsaw Uprising with a loss of around 250,000 Polish lives; establish the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe; and at Yalta, demand that Lviv be ceded by Poland to the Soviet Union.[12][13]

Rise

Stalin played a decisive role in engineering the 1921 Red Army invasion of Georgia following which he adopted particularly hardline, centralist policies towards Soviet Georgia, which included the Georgian Affair of 1922 and other repressions.[14][15] Lenin and Lev Kamenev helped to have Stalin appointed as General Secretary in 1922 to help build a base against Trotsky, who moved to formally impose the Party dictatorship over the industrial sectors.[10]

Lenin, who disliked Stalin's policy towards Georgia,[10] suffered a stroke in 1922, forcing him into semi-retirement in Gorki. Stalin visited him often, acting as his intermediary with the outside world.[10] The pair quarreled and their relationship deteriorated.[10] Lenin dictated increasingly disparaging notes on Stalin in what would become his testament. He criticized Stalin's rude manners, excessive power, ambition and politics, and suggested that Stalin should be removed from the position of General Secretary.[10] During Lenin's semi-retirement, Stalin forged an alliance with Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev against Trotsky. These allies prevented Lenin's Testament from being revealed to the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923.[10]

Lenin died of a heart attack on 21 January 1924. Thereafter, Stalin's disputes with Kamenev and Zinoviev intensified. Stalin allied himself now with Nikolai Bukharin. Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev were ejected from the Central Committee and then expelled from the Party.[10] Kamenev and Zinoviev were readmitted, but Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union.

Stalin pushed for more rapid industrialization and central control of the economy, contravening Lenin's New Economic Policy. At the end of 1927, a critical shortfall in grain supplies prompted Stalin to push for collectivisation of agriculture and order the seizures of grain hoards from kulak farmers.[10][11] Bukharin attacked these policies and advocated a return to the NEP, but the rest of the Politburo sided with Stalin and kicked him out in November 1929.

Changes to Soviet society, 1927–1939

Bolstering Soviet secret service and intelligence

| Part of a series on |

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

Stalin vastly increased the scope and power of the state's secret police and intelligence agencies. Under his guiding hand, Soviet intelligence forces began to set up intelligence networks in most of the major nations of the world, including Germany (the famous Rote Kappelle spy ring), Great Britain, France, Japan, and the United States. Stalin saw no difference between espionage, communist political propaganda actions, and state-sanctioned violence, and he began to integrate all of these activities within the NKVD. Stalin made considerable use of the Communist International movement in order to infiltrate agents and to ensure that foreign Communist parties remained pro-Soviet and pro-Stalin.

One of the best examples of Stalin's ability to integrate secret police and foreign espionage came in 1940, when he gave approval to the secret police to have Leon Trotsky assassinated in Mexico.[16]

Cult of personality

Stalin created a cult of personality in the Soviet Union around both himself and Lenin. Many personality cults in history have been frequently measured and compared to his. Numerous towns, villages and cities were renamed after the Soviet leader (see List of places named after Stalin) and the Stalin Prize and Stalin Peace Prize were named in his honor. He accepted grandiloquent titles (e.g. "Coryphaeus of Science," "Father of Nations," "Brilliant Genius of Humanity," "Great Architect of Communism," "Gardener of Human Happiness," and others), and helped rewrite Soviet history to provide himself a more significant role in the revolution. At the same time, according to Khrushchev, he insisted that he be remembered for "the extraordinary modesty characteristic of truly great people." Statues of Stalin depict him at a height and build approximating Alexander III, while photographic evidence suggests he was between 5 ft 5 in and 5 ft 6 in (165–168 cm).[17]

Trotsky criticized the cult of personality built around Stalin. It reached new levels during World War II, with Stalin's name included in the new Soviet national anthem. Stalin became the focus of literature, poetry, music, paintings and film, exhibiting fawning devotion, crediting Stalin with almost god-like qualities, and suggesting he single-handedly won the Second World War. It is debatable as to how much Stalin relished the cult surrounding him. The Finnish communist Tuominen records a sarcastic toast proposed by Stalin at a New Year Party in 1935 in which he said "Comrades! I want to propose a toast to our patriarch, life and sun, liberator of nations, architect of socialism [he rattled off all the appellations applied to him in those days]– Josef Vissarionovich Stalin, and I hope this is the first and last speech made to that genius this evening."[18]

In a 1956 speech, Nikita Khrushchev gave a denunciation of Stalin's actions: "It is impermissible and foreign to the spirit of Marxism-Leninism to elevate one person, to transform him into a superman possessing supernatural characteristics akin to those of a god."[4]

Purges and deportations

Purges

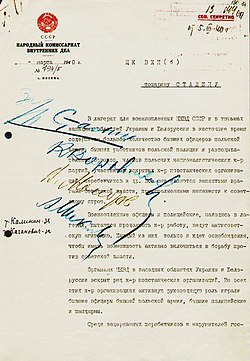

|

|

|

| Left: Beria's January 1940 letter to Stalin, asking permission to execute 346 "enemies of the CPSU and of the Soviet authorities" who conducted "counter-revolutionary, right-Trotskyite plotting and spying activities" Middle: Stalin's handwriting: "за" (support). Right: The Politburo's decision is signed by Secretary Stalin | ||

Stalin, as head of the Politburo consolidated near-absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party, justified as an attempt to expel 'opportunists' and 'counter-revolutionary infiltrators'.[19][20] Those targeted by the purge were often expelled from the party, however more severe measures ranged from banishment to the Gulag labor camps, to execution after trials held by NKVD troikas.[19][21][22]

In the 1930s, Stalin apparently became increasingly worried about the growing popularity of Sergei Kirov. At the 1934 Party Congress where the vote for the new Central Committee was held, Kirov received only three negative votes, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received 1,108 negative votes.[23] After the assassination of Kirov, which may have been orchestrated by Stalin, Stalin invented a detailed scheme to implicate opposition leaders in the murder, including Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev.[24] The investigations and trials expanded.[25] Stalin passed a new law on "terrorist organizations and terrorist acts", which were to be investigated for no more than ten days, with no prosecution, defense attorneys or appeals, followed by a sentence to be executed "quickly."[26]

Thereafter, several trials known as the Moscow Trials were held, but the procedures were replicated throughout the country. Article 58 of the legal code, listing prohibited anti-Soviet activities as counterrevolutionary crime was applied in the broadest manner.[27] The flimsiest pretexts were often enough to brand someone an "enemy of the people," starting the cycle of public persecution and abuse, often proceeding to interrogation, torture and deportation, if not death. The Russian word troika gained a new meaning: a quick, simplified trial by a committee of three subordinated to NKVD with sentencing carried out within 24 hours.[26]

| Before |

| After |

| Nikolai Yezhov, the young man walking with Stalin in the top photo from the 1930s, was shot in 1940. Following his death, Yezhov was edited out of the photo by Soviet censors.[28] Such retouching was a common occurrence during Stalin's rule. |

Many military leaders were convicted of treason, and a large scale purging of Red Army officers followed.[29] The repression of so many formerly high-ranking revolutionaries and party members led Leon Trotsky to claim that a "river of blood" separated Stalin's regime from that of Lenin.[30] In August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, where he had lived in exile since January 1937; this eliminated the last of Stalin's opponents among the former Party leadership.[31] The only three "Old Bolsheviks" (Lenin's Politburo) that remained were Stalin, Mikhail Kalinin, and Chairman of Sovnarkom Vyacheslav Molotov.

Mass operations of the NKVD also targeted "national contingents" (foreign ethnicities) such as Poles, ethnic Germans, Koreans, etc. A total of 350,000 (144,000 of them Poles) were arrested and 247,157 (110,000 Poles) were executed.[11] Many Americans who had emigrated to the Soviet Union during the worst of the Great Depression were executed; others were sent to prison camps or gulags.[32] Concurrent with the purges, efforts were made to rewrite the history in Soviet textbooks and other propaganda materials. Notable people executed by NKVD were removed from the texts and photographs as though they never existed. Gradually, the history of revolution was transformed to a story about just two key characters: Lenin and Stalin.

In light of revelations from the Soviet archives, historians now estimate that nearly 700,000 people (353,074 in 1937 and 328,612 in 1938) were executed in the course of the terror,[33] with the great mass of victims being "ordinary" Soviet citizens: workers, peasants, homemakers, teachers, priests, musicians, soldiers, pensioners, ballerinas, beggars.[34][35] Some experts believe the evidence released from the Soviet archives is understated, incomplete or unreliable.[36][37][38][39][40] For example, Robert Conquest suggests that the probable figure for executions during the years of the Great Purge is not 681,692, but some two and a half times as high. He believes that the KGB was covering its tracks by falsifying the dates and causes of death of rehabilitated victims.[41]

Stalin personally signed 357 proscription lists in 1937 and 1938 which condemned to execution some 40,000 people, and about 90% of these are confirmed to have been shot.[42] At the time, while reviewing one such list, Stalin reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years time? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyars Ivan the Terrible got rid of? No one."[43] In addition, Stalin dispatched a contingent of NKVD operatives to Mongolia, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD troika and unleashed a bloody purge in which tens of thousands were executed as 'Japanese Spies.' Mongolian ruler Khorloogiin Choibalsan closely followed Stalin's lead.[44]

Population transfer

Shortly before, during and immediately after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations on a huge scale which profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. It is estimated that between 1941 and 1949 nearly 3.3 million[2] were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian republics. By some estimates up to 43% of the resettled population died of diseases and malnutrition.[45]

Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the official reasons for the deportations, rightly or wrongly. Individual circumstances of those spending time in German-occupied territories were not examined.[46] After the brief Nazi occupation of the Caucasus, the entire population of five of the small highland peoples and the Crimean Tatars– more than a million people in total – were deported without notice or any opportunity to take their possessions.[46]

During Stalin's rule the following ethnic groups were deported completely or partially: Ukrainians, Poles, Koreans, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Karachays, Meskhetian Turks, Finns, Bulgarians, Greeks, Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians, and Jews. Large numbers of Kulaks, regardless of their nationality, were resettled to Siberia and Central Asia. Deportations took place in appalling conditions, often by cattle truck, and hundreds of thousands of deportees died en route.[2] Those who survived were forced to work without pay in the labour camps. Many of the deportees died of hunger or other conditions.

In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninism, and reversed most of them, although it was not until 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhetians and Volga Germans were allowed to return en masse to their homelands. The deportations had a profound effect on the peoples of the Soviet Union. The memory of the deportations played a major part in the separatist movements in the Baltic States, Tatarstan and Chechnya, even today.

Collectivization

Stalin's regime moved to force collectivization of agriculture. This was intended to increase agricultural output from large-scale mechanized farms, to bring the peasantry under more direct political control, and to make tax collection more efficient. Collectivization meant drastic social changes, on a scale not seen since the abolition of serfdom in 1861, and alienation from control of the land and its produce. Collectivization also meant a drastic drop in living standards for many peasants, and it faced violent reaction among the peasantry.

In the first years of collectivization it was estimated that industrial production would rise by 200% and agricultural production by 50%,[47] but these estimates were not met. Stalin blamed this unanticipated failure on kulaks (rich peasants), who resisted collectivization. (However, kulaks proper made up only 4% of the peasant population; the "kulaks" that Stalin targeted included the slightly better-off peasants who took the brunt of violence from the OGPU and the Komsomol. These peasants were about 60% of the population). Those officially defined as "kulaks," "kulak helpers," and later "ex-kulaks" were to be shot, placed into Gulag labor camps, or deported to remote areas of the country, depending on the charge. Archival data indicates that 20,201 people were executed during 1930, the year of Dekulakization.[44]

The two-stage progress of collectivization—interrupted for a year by Stalin's famous editorials, "Dizzy with success"[48] and "Reply to Collective Farm Comrades"[49]—is a prime example of his capacity for tactical political withdrawal followed by intensification of initial strategies.

Famines

Famine affected other parts of the USSR. The death toll from famine in the Soviet Union at this time is estimated at between five and ten million people.[50] The worst crop failure of late tsarist Russia, in 1892, had caused 375,000 to 400,000 deaths.[51] Most modern scholars agree that the famine was caused by the policies of the government of the Soviet Union under Stalin, rather than by natural reasons.[52]

According to Alan Bullock, "the total Soviet grain crop was no worse than that of 1931 ... it was not a crop failure but the excessive demands of the state, ruthlessly enforced, that cost the lives of as many as five million Ukrainian peasants." Stalin refused to release large grain reserves that could have alleviated the famine, while continuing to export grain; he was convinced that the Ukrainian peasants had hidden grain away, and strictly enforced draconian new collective-farm theft laws in response.[53][54] Other historians hold it was largely the insufficient harvests of 1931 and 1932 caused by a variety of natural disasters that resulted in famine, with the successful harvest of 1933 ending the famine.[55] Soviet and other historians have argued that the rapid collectivization of agriculture was necessary in order to achieve an equally rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union and ultimately win World War II. This is disputed by other historians; Alec Nove claims that the Soviet Union industrialized in spite of, rather than because of, its collectivized agriculture.

The USSR also experienced a major famine in 1947 as a result of war damage and severe droughts, but economist Michael Ellman argues that it could have been prevented if the government did not mismanage its grain reserves. The famine cost an estimated 1 to 1.5 million lives as well as secondary population losses due to reduced fertility.[56]

Ukrainian famine

The Holodomor famine is sometimes referred to as the Ukrainian Genocide, implying it was engineered by the Soviet government, specifically targeting the Ukrainian people to destroy the Ukrainian nation as a political factor and social entity.[57] While historians continue to disagree whether the policies that led to Holodomor fall under the legal definition of genocide, twenty six countries have officially recognized the Holodomor as such. On 28 November 2006 the Ukrainian Parliament approved a bill, according to which the Soviet-era forced famine was an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.[58] Professor Michael Ellman concludes that Ukrainians were victims of genocide in 1932-33, according to a more relaxed definition, which is favored by some specialists in the field of genocide studies. He asserts that Soviet policies greatly exacerbated the famine's death toll (such as the use of torture and execution to extract grain (see Law of Spikelets), with 1.8 million tonnes of it being exported during the height of the starvation - enough to feed 5 million people for one year, the use of force to prevent starving peasants from fleeing the worst affected areas, and the refusal to import grain or secure international humanitarian aid to alleviate the suffering) and that Stalin intended to use the starvation as a cheap and efficient means (as opposed to deportations and shootings) to kill off those deemed to be "counterrevolutionaries," "idlers," and "thieves," but not to annihilate the Ukrainian peasantry as a whole. He also claims that, while this is not the only Soviet genocide (e.g. The Polish operation of the NKVD), it is the worst in terms of mass casualties.[42]

Current estimates on the total number of casualties within Soviet Ukraine range mostly from 2.2 million[59][60] to 4 to 5 million.[61][62][63]

A Ukrainian court found Josef Stalin and other leaders of the former Soviet Union guilty of genocide by "organizing mass famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933" in January 2010. However, the court "dropped criminal proceedings over the suspects' deaths".[64][65]

Industrialization

The Russian Civil War and wartime communism had a devastating effect on the country's economy. Industrial output in 1922 was 13% of that in 1914. A recovery followed under the New Economic Policy, which allowed a degree of market flexibility within the context of socialism. Under Stalin's direction, this was replaced by a system of centrally ordained "Five-Year Plans" in the late 1920s. These called for a highly ambitious program of state-guided crash industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture.

With seed capital unavailable because of international reaction to Communist policies, little international trade, and virtually no modern infrastructure, Stalin's government financed industrialization both by restraining consumption on the part of ordinary Soviet citizens to ensure that capital went for re-investment into industry, and by ruthless extraction of wealth from the kulaks.

In 1933 workers' real earnings sank to about one-tenth of the 1926 level.[citation needed] Common and political prisoners in labor camps were forced to do unpaid labor, and communists and Komsomol members were frequently "mobilized" for various construction projects. The Soviet Union used numerous foreign experts, to design new factories, supervise construction, instruct workers and improve manufacturing processes. The most notable foreign contractor was Albert Kahn's firm that designed and built 521 factories between 1930 and 1932. As a rule, factories were supplied with imported equipment.

In spite of early breakdowns and failures, the first two Five-Year Plans achieved rapid industrialization from a very low economic base. While it is generally agreed that the Soviet Union achieved significant levels of economic growth under Stalin, the precise rate of growth is disputed. It is not disputed, however, that these gains were accomplished at the cost of millions of lives. Official Soviet estimates stated the annual rate of growth at 13.9%; Russian and Western estimates gave lower figures of 5.8% and even 2.9%. Indeed, one estimate is that Soviet growth became temporarily much higher after Stalin's death.[66]

According to Robert Lewis the Five-Year Plan substantially helped to modernize the previously backward Soviet economy. New products were developed, and the scale and efficiency of existing production greatly increased. Some innovations were based on indigenous technical developments, others on imported foreign technology.[67] Despite its costs, the industrialization effort allowed the Soviet Union to fight, and ultimately win, World War II.

Science

Science in the Soviet Union was under strict ideological control by Stalin and his government, along with art and literature. There was significant progress in "ideologically safe" domains, owing to the free Soviet education system and state-financed research. However, in several cases the consequences of ideological pressure were dramatic—the most notable examples being the "bourgeois pseudosciences" genetics and cybernetics. Some areas of physics were criticized,[68][69] However, although initially planned,[70] while Stalin personally and directly contributed to study in Linguistics, the principle work of which is a small essay, "Marxism and Linguistic Questions."[71] Scientific research was hindered by the fact that many scientists were sent to labor camps (including Lev Landau, later a Nobel Prize winner, who spent a year in prison in 1938–1939) or executed (e.g. Lev Shubnikov, shot in 1937).

Social services

Under the Soviet government people benefited from some social liberalization. Girls were given an adequate, equal education and women had equal rights in employment,[11] improving lives for women and families. Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which significantly increased the lifespan and quality of life of the typical Soviet citizen.[11] Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people universal access to healthcare and education, effectively creating the first generation free from the fear of typhus, cholera, and malaria.[72] The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record low numbers, increasing life spans by decades.[72]

Soviet women under Stalin were the first generation of women able to give birth in the safety of a hospital, with access to prenatal care.[72] Education was also an example of an increase in standard of living after economic development. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first near-universally literate generation. Millions benefitted from mass literacy campaigns in the 1930s, and from workers training schemes.[73] Engineers were sent abroad to learn industrial technology, and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract.[72] Transport links were improved and many new railways built. Workers who exceeded their quotas, Stakhanovites, received many incentives for their work;[73] they could afford to buy the goods that were mass-produced by the rapidly expanding Soviet economy.

The increase in demand due to industrialization and the decrease in the workforce due to World War II and repressions generated a major expansion in job opportunities for the survivors, especially for women.[73]

Culture

Although born in Georgia, Stalin became a Russian nationalist and significantly promoted Russian history, language, and Russian national heroes, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s. He held the Russians up as the elder brothers of the non-Russian minorities.[74]

During Stalin's reign the official and long-lived style of Socialist Realism was established for painting, sculpture, music, drama and literature. Previously fashionable "revolutionary" expressionism, abstract art, and avant-garde experimentation were discouraged or denounced as "formalism".

Famous figures were repressed, and many persecuted, tortured and executed, both "revolutionaries" (among them Isaac Babel, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Gumilev, Lev Gumilev) and "non-conformists" (for example, Osip Mandelstam). Small amounts of remnant of pre-revolutionary Russia survived[clarification needed]. The degree of Stalin's personal involvement in general, and in specific instances, has been the subject of discussion. Stalin's favorite novel Pharaoh, shared similarities with Sergei Eisenstein's film, Ivan the Terrible, produced under Stalin's tutelage.

In architecture, a Stalinist Empire Style (basically, updated neoclassicism on a very large scale, exemplified by the Seven Sisters of Moscow) replaced the constructivism of the 1920s. Stalin's rule had a largely disruptive effect on indigenous cultures within the Soviet Union, though the politics of Korenizatsiya and forced development were possibly beneficial to the integration of later generations of indigenous cultures.

Religion

Stalin followed the position adopted by Lenin that religion was an opiate that needed to be removed in order to construct the ideal communist society. To this end his government promoted atheism through special atheistic education in schools, massive amounts of anti-religious propaganda, the antireligious work of public institutions (especially the Society of the Godless), discriminatory laws, and also a terror campaign against religious believers. By the late 1930s it had become dangerous to be publicly associated with religion[75]

Stalin's role in the fortunes of the Russian Orthodox Church is complex. Continuous persecution in the 1930s resulted in its near-extinction as a public institution: by 1939, active parishes numbered in the low hundreds (down from 54,000 in 1917), many churches had been leveled, and tens of thousands of priests, monks and nuns were persecuted and killed. Over 100,000 were shot during the purges of 1937–1938.[76] During World War II, the Church was allowed a revival as a patriotic organization, after the NKVD had recruited the new metropolitan, the first after the revolution, as a secret agent. Thousands of parishes were reactivated until a further round of suppression in Khrushchev's time. The Russian Orthodox Church Synod's recognition of the Soviet government and of Stalin personally led to a schism with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia.

Just days before Stalin's death, certain religious sects were outlawed and persecuted. Many religions popular in the ethnic regions of the Soviet Union including the Roman Catholic Church, Uniats, Baptists, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, etc. underwent ordeals similar to the Orthodox churches in other parts: thousands of monks were persecuted, and hundreds of churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, sacred monuments, monasteries and other religious buildings were razed.

Theorist

Stalin and his supporters have highlighted the notion that socialism can be built and consolidated by a country as underdeveloped as Russia during the 1920s. Indeed this might be the only means in which it could be built in a hostile environment.[77] In 1933, Stalin put forward the theory of aggravation of the class struggle along with the development of socialism, arguing that the further the country would move forward, the more acute forms of struggle will be used by the doomed remnants of exploiter classes in their last desperate efforts– and that, therefore, political repression was necessary.

In 1936, Stalin announced that the society of the Soviet Union consisted of two non-antagonistic classes: workers and kolkhoz peasantry. These corresponded to the two different forms of property over the means of production that existed in the Soviet Union: state property (for the workers) and collective property (for the peasantry). In addition to these, Stalin distinguished the stratum of intelligentsia. The concept of "non-antagonistic classes" was entirely new to Leninist theory. Among Stalin's contributions to Communist theoretical literature were "Marxism and the National Question", "Trotskyism or Leninism", and Stalin's Collected Works.

Calculating the number of victims

Researchers before the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union attempting to count the number of people killed under Stalin's regime produced estimates ranging from 3 to 60 million.[78] After the Soviet Union dissolved, evidence from the Soviet archives also became available, containing official records of the execution of approximately 800,000 prisoners under Stalin for either political or criminal offenses, around 1.7 million deaths in the Gulags and some 390,000 deaths during kulak forced resettlement– for a total of about 3 million officially recorded victims in these categories.[79]

The official Soviet archival records do not contain comprehensive figures for some categories of victims, such as the those of ethnic deportations or of German population transfers in the aftermath of WWII.[80] Other notable exclusions from NKVD data on repression deaths include the Katyn massacre, other killings in the newly occupied areas, and the mass shootings of Red Army personnel (deserters and so-called deserters) in 1941. Also, the official statistics on Gulag mortality exclude deaths of prisoners taking place shortly after their release but which resulted from the harsh treatment in the camps.[81] Some historians also believe the official archival figures of the categories that were recorded by Soviet authorities to be unreliable and incomplete.[82][83] In addition to failures regarding comprehensive recordings, as one additional example, Robert Gellately and Simon Sebag-Montefiore argue the many suspects beaten and tortured to death while in "investigative custody" were likely not to have been counted amongst the executed.[11][84]

Historians working after the Soviet Union's dissolution have estimated victim totals ranging from approximately 4 million to nearly 10 million, not including those who died in famines.[85] Russian writer Vadim Erlikman, for example, makes the following estimates: executions, 1.5 million; gulags, 5 million; deportations, 1.7 million out of 7.5 million deported; and POWs and German civilians, 1 million– a total of about 9 million victims of repression.[86]

Some have also included deaths of 6 to 8 million people in the 1932–1933 famine as victims of Stalin's repression. This categorization is controversial however, as historians differ as to whether the famine was a deliberate part of the campaign of repression against kulaks and others,[42][87] or simply an unintended consequence of the struggle over forced collectivization.[54][88][89]

Accordingly, if famine victims are included, a minimum of around 10 million deaths—6 million from famine and 4 million from other causes—are attributable to the regime,[90] with a number of recent historians suggesting a likely total of around 20 million, citing much higher victim totals from executions, gulags, deportations and other causes.[91] Adding 6–8 million famine victims to Erlikman's estimates above, for example, would yield a total of between 15 and 17 million victims. Researcher Robert Conquest, meanwhile, has revised his original estimate of up to 30 million victims down to 20 million.[92] Others maintain that their earlier higher victim total estimates are correct.[93][94]

World War II, 1939–1945

Pact with Hitler

After a failed attempt to sign an anti-German political alliance with France and Britain[95][96][97] and talks with Germany regarding a potential political deal,[95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104] on 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union entered into a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, negotiated by Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.[105] Officially a non-aggression treaty only, an appended secret protocol, also reached on 23 August 1939, divided the whole of eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence.[106][107]

The eastern part of Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and part of Romania were recognized as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence,[107] with Lithuania added in a second secret protocol in September 1939.[108] Stalin and Ribbentrop traded toasts on the night of the signing discussing past hostilities between the countries.[109]

Implementing the division of Eastern Europe and other invasions

On 1 September 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of Poland started World War II.[105] On 17 September the Red Army invaded eastern Poland and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.[110][111] Eleven days later, the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was modified, allotting Germany a larger part of Poland, while ceding most of Lithuania to the Soviet Union.[112]

After Stalin declared that he was going to "solve the Baltic problem", by June 1940, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were merged into the Soviet Union, after repressions and actions therein brought about the deaths of over 160,000 citizens of these states.[112][113][114][115] After facing stiff resistance in an invasion of Finland,[116] an interim peace was entered, granting the Soviet Union the eastern region of Karelia (10% of Finnish territory).[116]

After this campaign, Stalin took actions to bolster the Soviet military, modify training and improve propaganda efforts in the Soviet military.[117] In June 1940, Stalin directed the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, proclaiming this formerly Romanian territory part of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.[118] But in annexing northern Bukovina, Stalin had gone beyond the agreed limits of the secret protocol.[118]

After the Tripartite Pact was signed by Axis Powers Germany, Japan and Italy, in October 1940, Stalin traded letters with Ribbentrop, with Stalin writing about entering an agreement regarding a "permanent basis" for their "mutual interests."[119] After a conference in Berlin between Hitler, Molotov and Ribbentrop, Germany presented the Molotov with a proposed written agreement for Axis entry.[118][120] On 25 November, Stalin responded with a proposed written agreement for Axis entry which was never answered by Germany.[121] Shortly thereafter, Hitler issued a secret directive on the eventual attempts to invade the Soviet Union.[121] In an effort to demonstrate peaceful intentions toward Germany, on 13 April 1941, Stalin oversaw the signing of a neutrality pact with Axis power Japan.[122]

Hitler breaks the pact

During the early morning of 22 June 1941, Hitler broke the pact by implementing Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of Soviet held territories and the Soviet Union that began the war on the Eastern Front.[123] Although Stalin had received warnings from spies and his generals,[124][125][126][127][128] he felt that Germany would not attack the Soviet Union until Germany had defeated Britain.[124] In the initial hours after the German attack commenced, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.[11]

Accounts by Nikita Khrushchev and Anastas Mikoyan claim that, after the invasion, Stalin retreated to his dacha in despair for several days and did not participate in leadership decisions.[129] However, some documentary evidence of orders given by Stalin contradicts these accounts, leading some historians to speculate that Kruschev's account is inaccurate.[130] By the end of 1941, the Soviet military had suffered 4.3 million casualties[131] and German forces had advanced 1,050 miles (1,690 kilometers).[132]

Soviets stop the Germans

While the Germans pressed forward, Stalin was confident of an eventual Allied victory over Germany. In September 1941, Stalin told British diplomats that he wanted two agreements: (1) a mutual assistance/aid pact and (2) a recognition that, after the war, the Soviet Union would gain the territories in countries that it had taken pursuant to its division of Eastern Europe with Hitler in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[133] The British agreed to assistance but refused to agree upon the territorial gains, which Stalin accepted months later as the military situation deteriorated somewhat in mid-1942.[133] By December, Hitler's troops had advanced to within 20 miles of the Kremlin in Moscow.[134] On 5 December, the Soviets launched a counteroffensive, pushing German troops back 40–50 miles from Moscow, the Wermacht's first significant defeat of the war.[134]

In 1942, Hitler shifted his primary goal from an immediate victory in the East, to the more long-term goal of securing the southern Soviet Union to protect oil fields vital to a long-term German war effort.[135] While Red Army generals saw evidence that Hitler would shift efforts south, Stalin considered this to be a flanking campaign in efforts to take Moscow.[136] During the war, Time Magazine named Stalin Time Person of the Year twice[137] and he was also one of the nominees for Time Person of the Century title.

Soviet push to Germany

The Soviets repulsed the important German strategic southern campaign and, although 2.5 million Soviet casualties were suffered in that effort, it permitted the Soviets to take the offensive for most of the rest of the war on the Eastern Front.[138]

Germany attempted an encirclement attack at Kursk, which was successfully repulsed by the Soviets.[139] Kursk marked the beginning of a period where Stalin became more willing to listen to the advice of his generals.[140] By the end of 1943, the Soviets occupied half of the territory taken by the Germans from 1941-1942.[140] Soviet military industrial output also had increased substantially from late 1941 to early 1943 after Stalin had moved factories well to the East of the front, safe from German invasion and air attack.[141]

In November 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in Tehran.[142] The parties later agreed that Britain and America would launch a cross-channel invasion of France in May 1944, along with a separate invasion of southern France.[143] Stalin insisted that, after the war, the Soviet Union should incorporate the portions of Poland it occupied pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Germany, which Churchill tabled.[144]

In 1944, the Soviet Union made significant advances across Eastern Europe toward Germany,[145] including Operation Bagration, a massive offensive in Belorussia against the German Army Group Centre.[146]

Final victory

By April 1945, Germany faced its last days with 1.9 million German soldiers in the East fighting 6.4 million Red Army soldiers while 1 million German soldiers in the West battled 4 million Western Allied soldiers.[147] While initial talk existed of a race to Berlin by the Allies, after Stalin successfully lobbied for Eastern Germany to fall within the Soviet "sphere of influence" at Yalta, no plans were made by the Western Allies to seize the city by a ground operation.[148][149]

On 30 April, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide, after which Soviet forces found their remains, which had been burned at Hitler's directive.[150] German forces surrendered a few days later. Despite the Soviets' possession of Hitler's remains, Stalin did not believe that his old nemesis was actually dead, a belief that remained for years after the war.[151][152]

Fending off the German invasion and pressing to victory in the East required a tremendous sacrifice by the Soviet Union. Soviet military casualties totaled approximately 35 million (official figures 28.2 million) with approximately 14.7 million killed, missing or captured (official figures 11.285 million).[153] Although figures vary, the Soviet civilian death toll probably reached 20 million.[153] Thereafter, Stalin was at times referred to as one of the most influential men in human history.[154][155]

Questionable tactics

After taking around 300,000 Polish prisoners in 1939 and early 1940,[156][157][157][158][159] 25,700 Polish POWs were executed on 5 March 1940, pursuant to a note from to Stalin from Lavrenty Beria, the members of the Soviet Politburo,[160][161] in what became known as the Katyn massacre.[162][160][163] While Stalin personally told a Polish general they'd "lost track" of the officers in Manchuria,[164][165][166][166] Polish railroad workers found the mass grave after the 1941 Nazi invasion.[167] The massacre became a source of political controversy,[168][169] with the Soviets eventually claiming that Germany committed the executions when the Soviet Union retook Poland in 1944.[160][170] The Soviets did not admit responsibility until 1990.[171]

Stalin introduced controversial military orders, such as Order No. 270, requiring superiors to shoot deserters on the spot[172] while their family members were subject to arrest.[173] Thereafter, Stalin also conducted a purge of several military commanders that were shot for "cowardice" without a trial.[173] Stalin issued Order No. 227, directing that commanders permitting retreat without permission to be subject to a military tribunal,[174] and soldiers guilty of disciplinary procedures to be forced into "penal battalions", which were sent to the most dangerous sections of the front lines.[174] From 1942 to 1945, 427,910 soldiers were assigned to penal battalions.[175] The order also directed "blocking detachments" to shoot fleeing panicked troops at the rear.[174]

In June 1941, weeks after the German invasion began, Stalin also directed employing a scorched earth policy of destroying the infrastructure and food supplies of areas before the Germans could seize them, and that partisans were to be set up in evacuated areas.[130] He also ordered the NKVD to murder around one hundred thousand political prisoners in areas where the Wermacht approached,[176] while others were deported east.[82][177]

After the capture of Berlin, Soviet troops reportedly raped from tens of thousands to two million women,[178] and 50,000 during and after the occupation of Budapest.[179][180] In former Axis countries, such as Germany, Romania and Hungary, Red Army officers generally viewed cities, villages and farms as being open to pillaging and looting.[181]

In the Soviet Occupation Zone of post-war Germany, the Soviets set up ten NKVD-run "special camps" subordinate to the GULAG.[182] These "special camps" were former Stalags, prisons, or Nazi concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen (special camp number 7) and Buchenwald (special camp number 2).[183] According to German government estimates, "65,000 people died in those Soviet-run camps or in transportation to them."[184]

According to recent figures, of an estimated four million POWs taken by the Russians, including Germans, Japanese, Hungarians, Romanians and others, some 580,000 never returned, presumably victims of privation or the Gulags.[185] Soviet POWs and forced laborers who survived German captivity were sent to special "transit" or "filtration" camps meant determine which were potential traitors.[186]

Of the approximately 4 million to be repatriated 2,660,013 were civilians and 1,539,475 were former POWs.[186] Of the total, 2,427,906 were sent home and 801,152 were reconscripted into the armed forces.[186] 608,095 were enrolled in the work battalions of the defense ministry.[186] 272,867 were transferred to the authority of the NKVD for punishment, which meant a transfer to the Gulag system.[186][187][188] 89,468 remained in the transit camps as reception personnel until the repatriation process was finally wound up in the early 1950s.[186]

Allied conferences on post-war Europe

Stalin met in several conferences with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (and later Clement Attlee) and/or American President Franklin D. Roosevelt (and later Harry Truman) to plan military strategy and, later, to discuss Europe's postwar reorganization. Very early conferences, such as that with British diplomats in Moscow in 1941 and with Churchill and American diplomats in in Moscow in 1942, focused mostly upon war planning and supply, though some preliminary postwar reorganization discussion also occurred. In 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in the Tehran Conference. In 1944, Stalin met with Churchill in the Moscow Conference. Beginning in late 1944, the Red Army occupied much of Eastern Europe during these conferences and the discussions shifted to a more intense focus on the reorganization of postwar Europe.

In February 1945, at the conference at Yalta, Stalin demanded a Soviet sphere of political influence in Eastern Europe.[189] Stalin eventually was convinced by Churchill and Roosevelt not to dismember Germany.[189] Stalin also stated that the Polish government-in-exile demands for self-rule were not negotiable, such that the Soviet Union would keep the territory of eastern Poland they had already taken by invasion with German consent in 1939, and wanted the pro-Soviet Polish government installed.[189] After resistance by Churchill and Roosevelt, Stalin promised a re-organization of the current Communist puppet government on a broader democratic basis in Poland.[189] He stated the new government's primary task would be to prepare elections.[190]

The parties at Yalta further agreed that the countries of liberated Europe and former Axis satellites would be allowed to "create democratic institutions of their own choice", pursuant to the "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live."[191] The parties also agreed to help those countries form interim governments "pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections" and "facilitate where necessary the holding of such elections."[191] After the re-organization of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, the parties agreed that the new party shall "be pledged to the holding of free and unfettered elections as soon as possible on the basis of universal suffrage and secret ballot."[191] One month after Yalta, the Soviet NKVD arrested 16 Polish leaders wishing to participate in provisional government negotiations, for alleged "crimes" and "diversions", which drew protest from the West.[190] The fraudulent Polish elections, held in January 1947 resulted in Poland's official transformation to undemocratic communist state by 1949.

At the Potsdam Conference from July to August 1945, though Germany had surrendered months earlier, instead of withdrawing Soviet forces from Eastern European countries, Stalin had not moved those forces. At the beginning of the conference, Stalin repeated previous promises to Churchill that he would refrain from a "Sovietization" of Eastern Europe.[192] Stalin pushed for reparations from Germany without regard to the base minimum supply for German citizens' survival, which worried Truman and Churchill who thought that Germany would become a financial burden for Western powers.[193]

In addition to reparations, Stalin pushed for "war booty", which would permit the Soviet Union to directly seize property from conquered nations without quantitative or qualitative limitation, and a clause was added permitting this to occur with some limitations.[193] By July 1945, Stalin's troops effectively controlled the Baltic States, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania, and refugees were fleeing out of these countries fearing a Communist take-over. The western allies, and especially Churchill, were suspicious of the motives of Stalin, who had already installed communist governments in the central European countries under his influence.

In these conferences, his first appearances on the world stage, Stalin proved to be a formidable negotiator. Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Secretary noted: "Marshal Stalin as a negotiator was the toughest proposition of all. Indeed, after something like thirty years' experience of international conferences of one kind and another, if I had to pick a team for going into a conference room, Stalin would be my first choice. Of course the man was ruthless and of course he knew his purpose. He never wasted a word. He never stormed, he was seldom even irritated."[194]

Post-war era, 1945–1953

The Iron Curtain and the Eastern Bloc

After Soviet forces remained in Eastern and Central European countries, with the beginnings of communist puppet regimes in those countries, Churchill referred to the region as being behind an "Iron Curtain" of control from Moscow.[195][196] The countries under Soviet control in Eastern and Central Europe were sometimes called the "Eastern bloc" or "Soviet Bloc".

In Soviet-controlled East Germany, the major task of the ruling communist party in Germany was to channel Soviet orders down to both the administrative apparatus and the other bloc parties pretending that these were initiatives of its own,[197] with deviations potentially leading to reprimands, imprisonment, torture and even death.[197] Property and industry were nationalized under their government.[197]

The German Democratic Republic was declared on 7 October 1949, with a new constitution which enshrined socialism and gave the Soviet-controlled Socialist Unity Party ("SED") control. In Berlin, after citizens strongly rejected communist candidates in an election, in June 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded West Berlin, the portion of Berlin not under Soviet control, cutting off all supply of food and other items. The blockade failed due to the unexpected massive aerial resupply campaign carried out by the Western powers known as the Berlin Airlift. In 1949, Stalin conceded defeat and ended the blockade.

While Stalin had promised at the Yalta Conference that free elections would be held in Poland,[191] after an election failure in "3 times YES" elections,[198] vote rigging was employed to win a majority in the carefully controlled poll.[199][200][201] Following the forged referendum, the Polish economy started to become nationalized.[202]

In Hungary, when the Soviets installed a communist government, Mátyás Rákosi, who described himself as "Stalin's best Hungarian disciple"[203] and "Stalin's best pupil",[204] took power. Rákosi employed "salami tactics", slicing up these enemies like pieces of salami,[205] to battle the initial postwar political majority ready to establish a democracy.[206] Rákosi, employed Stalinist political and economic programs, and was dubbed the "bald murderer" for establishing one of the harshest dictatorships in Europe.[206][207] Approximately 350,000 Hungarian officials and intellectuals were purged from 1948 to 1956.[206]

During World War II, in Bulgaria, the Red Army crossed the border and created the conditions for a communist coup detat on the following night.[208] The Soviet military commander in Sofia assumed supreme authority, and the communists whom he instructed, including Kimon Georgiev, took full control of domestic politics.[208]

In 1949, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania founded the Comecon in accordance with Stalin's desire to enforce Soviet domination of the lesser states of Central Europe and to mollify some states that had expressed interest in the Marshall Plan,[209] and which were now, increasingly, cut off from their traditional markets and suppliers in Western Europe.[210] Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland had remained interested in Marshall aid despite the requirements for a convertible currency and market economies. In July 1947, Stalin ordered these communist-dominated governments to pull out of the Paris Conference on the European Recovery Programme. This has been described as "the moment of truth" in the post-World War II division of Europe.[210]

In Greece, Britain and the United States supported the anti-communists in the Greek Civil War and suspected the Soviets of supporting the Greek communists, although Stalin refrained from getting involved in Greece, dismissing the movement as premature. Albania remained an ally of the Soviet Union, but Yugoslavia broke with the USSR in 1948.

In Stalin's last year of life, one of his last major foreign policy initiatives was the 1952 Stalin Note for German reunification and Superpower disengagement from Central Europe, but Britain, France, and the United States viewed this with suspicion and rejected the offer.

Sino-Soviet Relations

In Asia, the Red Army had overrun Manchuria in the last month of the war and then also occupied Korea above the 38th parallel north. Mao Zedong's Communist Party of China, though receptive to minimal Soviet support, defeated the pro-Western and heavily American-assisted Chinese Nationalist Party in the Chinese Civil War.

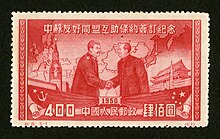

There was friction between Stalin and Mao from the beginning. During World War II Stalin had supported the conservative dictator of China, Chiang Kai-Shek, as a bulwark against Japan and had turned a blind eye to Chiang's mass killings of communists. He generally put his alliance with Chiang against Japan ahead of helping his ideological allies in China in his priorities. Even after the war Stalin concluded a non-aggression pact between the USSR and Chiang's Kuomintang (KMT) regime in China and instructed Mao and the Chinese communists to cooperate with Chiang and the KMT after the war. Mao did not follow Stalin's instructions though and started a communist revolution against Chiang. Stalin did not believe Mao would be successful so he was less than enthusiastic in helping Mao. The USSR continued to maintain diplomatic relations with Chiang's KMT regime until 1949 when it became clear Mao would win.

Stalin did conclude a new friendship and alliance treaty with Mao after he defeated Chiang. But there was still a lot of tension between the two leaders and resentment by Mao for Stalin's less than enthusiastic help during the civil war in China.

The Communists controlled mainland China while the Nationalists held a rump state on the island of Taiwan. The Soviet Union soon after recognized Mao's People's Republic of China, which it regarded as a new ally. The People's Republic claimed Taiwan, though it had never held authority there.

Diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and China reached a high point with the signing of the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance. Both countries provided military support to a new friendly state in North Korea. After various Korean border conflicts, war broke out with U.S.-allied South Korea in 1950, starting the Korean War.

North Korea

Contrary to America's policy which restrained armament (limited equipment was provided for infantry and police forces) to South Korea, Stalin extensively armed Kim Il Sung's North Korean army and air forces with military equipment (to include T-34/85 tanks) and "advisors" far in excess of those required for defensive purposes) in order to facilitate Kim's (a former Soviet Officer) aim of conquering the rest of the Korean peninsula.

The North Korean Army struck in the pre-dawn hours of Sunday, 25 June 1950, crossing the 38th parallel behind a firestorm of artillery, beginning their invasion of South Korea.[211] During the Korean War, Soviet pilots flew Soviet aircraft from Chinese bases against United Nations aircraft defending South Korea. Post cold war research in Soviet Archives has revealed that the Korean War was begun by Kim Il-sung with the express permission of Stalin, though this is disputed by North Korea.

Israel

Stalin originally supported the creation of Israel in 1948. The USSR was one of the first nations to recognize the new country.[212] Golda Meir came to Moscow as the first Israeli Ambassador to the USSR that year. However, after providing war materiel for Israel through Czechoslovakia, he later changed his mind and came out against Israel.

Falsifiers of History

In 1948, Stalin personally edited and rewrote by hand sections of the cold war book Falsifiers of History.[213] Falsifiers was published in response to the documents made public in Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939–1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office,[214][215] which included the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and other secret German-Soviet relations documents.[214][216] Falsifiers originally appeared as a series of articles in Pravda in February 1948,[215] and was subsequently published in numerous language and distributed worldwide.[217]

The book did not attempt to directly counter or deal with the documents published in Nazi-Soviet Relations[218] and rather, focused upon Western culpability for the outbreak of war in 1939.[217] It argues that "Western powers" aided Nazi rearmament and aggression, including that American bankers and industrialists provided capital for the growth of German war industries, while deliberately encouraging Hitler to expand eastward.[214][217] It depicted the Soviet Union as striving to negotiate a collective security against Hitler, while being thwarted by double-dealing Anglo-French appeasers who, despite appearances, had no intention of a Soviet alliance and were secretly negotiating with Berlin.[217] It casts the Munich agreement, not just as Anglo-French short-sightedness or cowardice, but as a "secret" agreement that was a "a highly important phase in their policy aimed at goading the Hitlerite aggressors against the Soviet Union."[219] The book also included the claim that, during the Pact's operation, Stalin rejected Hitler's offer to share in a division of the world, without mentioning the Soviet offers to join the Axis.[220] Historical studies, official accounts, memoirs and textbooks published in the Soviet Union used that depiction of events until the Soviet Union's dissolution.[220]

Domestic Support

Domestically, Stalin was seen as a great wartime leader who had led the Soviets to victory against the Nazis. His early cooperation with Hitler was forgotten. That cooperation included helping the German Army violate the Treaty of Versailles limitations, with training in the Soviet Union, the notorious Molotov-von Ribbentrop treaty which partitioned Poland giving the Soviet Union what is now Belarus and granted the Soviet Union a free hand in Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia, and Soviet trade with Hitler to counteract the expected French and British trade blockades.

By the end of the 1940s, Russian patriotism increased due to successful propaganda efforts. For instance, some inventions and scientific discoveries were claimed by Soviet propaganda. Examples include the boiler, reclaimed by father and son Cherepanovs; the electric light, by Yablochkov and Lodygin; the radio, by Popov; and the airplane, by Mozhaysky. Stalin's internal repressive policies continued (including in newly acquired territories), but never reached the extremes of the 1930s, in part because the smarter party functionaries had learned caution.

The "Doctors' plot"

The "Doctors' plot" was a plot outlined by Stalin and Soviet officials in 1952 and 1953 whereby several doctors (over half of which were Jewish) allegedly attempted to kill Soviet officials.[221] The prevailing opinion of many scholars outside the Soviet Union is that Stalin intended to use the resulting doctors' trial to launch a massive party purge.[222] The plot is also viewed by many historians as an anti-Semitic provocation.[221] It followed on the heels of the 1952 show trials of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee[223] and the secret execution of thirteen members on Stalin's orders in the Night of the Murdered Poets.[224]

Thereafter, in a December Politburo session, Stalin announced that "Every Jewish nationalist is the agent of the American intelligence service. Jewish nationalists think that their nation was saved by the USA (there you can become rich, bourgeois, etc.). They think they're indebted to the Americans. Among doctors, there are many Jewish nationalists."[225] To mobilize the Soviet people for his campaign, Stalin ordered TASS and Pravda to issue stories along with Stalin's alleged uncovering of a "Doctors Plot" to assassinate top Soviet leaders,[226][227] including Stalin, in order to set the stage for show trials.[228]

The next month, Pravda published stories with text regarding the purported "Jewish bourgeois-nationalist" plotters.[229] Kruschev wrote that Stalin hinted him to incite anti-Semitism in the Ukraine, telling him that "the good workers at the factory should be given clubs so they can beat the hell out of those Jews."[230][231] Stalin also ordered falsely accused physicians to be tortured "to death".[232] Regarding the origins of the plot, people who knew Stalin, such as Kruschev, suggest that Stalin had long harbored negative sentiments toward Jews,[221][233][234] and anti-Semitic trends in the Kremlin's policies were further fueled by the exile of Leon Trotsky.[221][235] In 1946, Stalin allegedly said privately that "every Jew is a potential spy."[221][236]

Some historians have argued that Stalin was also planning to send millions of Jews to four large newly built labor camps in Western Russia[228][237] using a "Deportation Commission"[238][239][240] that would purportedly act to save Soviet Jews from an engraged Soviet population after the Doctors Plot trials.[238][241][242] Others argue that any charge of an alleged mass deportation lacks specific documentary evidence.[227] Regardless of whether a plot to deport Jews was planned, in his "Secret Speech" in 1956, Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev stated that the Doctors Plot was "fabricated ... set up by Stalin", that Stalin told the judge to beat confessions from the defendants[243] and had told Politburo members "You are blind like young kittens. What will happen without me? The country will perish because you do not know how to recognize enemies."[243]

Death and aftermath

At the end of January 1953 Stalin's personal physician Miron Vovsi (cousin of Solomon Mikhoels who was assassinated in 1948 at the orders of Stalin)[224] was arrested within the frame of the so-named Doctors' Plot.[244]

On 1 March 1953, after an all-night dinner in his Kuntsevo residence some 15 km west of Moscow centre with interior minister Lavrentiy Beria and future premiers Georgy Malenkov, Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin did not emerge from his room, having probably suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body.

Although his guards thought that it was odd for him not to rise at his usual time, they were under orders not to disturb him. At around 10 p.m. he was discovered by Peter Lozgachev, the Deputy Commandant of Kuntsevo, who recalled a horrifying scene of Stalin lying on the floor of his room wearing pyjama bottoms and an undershirt and was soaked in stale urine. A frightened Lozgachev asked Stalin what has happened but his all he could get out of the Generalissimo was unintelligible responses that sounded like "Dzhh." Lozgachez frantically called a few party officials asking them to send good doctors.[245] Lavrentiy Beria was informed and arrived a few hours afterwards, and the doctors only arrived in the early morning of 2 March. Stalin died four days later, on 5 March 1953[5], at the age of 74, and was embalmed on 9 March. Officially, the cause of death was listed as a cerebral hemorrhage. His body was preserved in Lenin's Mausoleum until 31 October 1961, when his body was removed from the Mausoleum and buried next to the Kremlin walls as part of the process of de-Stalinization.

It has been suggested that Stalin was assassinated. The ex-Communist exile Avtorkhanov argued this point as early as 1975. The political memoirs of Vyacheslav Molotov, published in 1993, claimed that Beria had boasted to Molotov that he poisoned Stalin: "I took him out."

Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs that Beria had, immediately after the stroke, gone about "spewing hatred against [Stalin] and mocking him", and then, when Stalin showed signs of consciousness, dropped to his knees and kissed his hand. When Stalin fell unconscious again, Beria immediately stood and spat.

Later analysis of death

In 2003, a joint group of Russian and American historians announced their view that Stalin ingested warfarin, a powerful rat poison that inhibits coagulation of the blood and so predisposes the victim to hemorrhagic stroke (cerebral hemorrhage). Since it is flavorless, warfarin is a plausible weapon of murder. The facts surrounding Stalin's death will probably never be known with certainty.[246]

His demise arrived at a convenient time for Lavrenty Beria and others, who feared being swept away in yet another purge. It is believed[who?] that Stalin felt Beria's power was too great and threatened his own. According to Molotov's memoirs, Beria claimed to have poisoned Stalin, saying, "I took him out." Whether Beria or anyone else was directly responsible for Stalin's death, it is true that the Politburo did not summon medical attention for Stalin for more than a day after he was found.[247]

Reaction by successors

The harshness with which Soviet affairs were conducted during Stalin's rule was subsequently repudiated by his successors in the Communist Party leadership, most notably by Nikita Khrushchev's repudiation of Stalinism in February 1956. In his "Secret Speech", On the Personality Cult and its Consequences, delivered to a closed session of the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev denounced Stalin for his cult of personality, and his regime for "violation of Leninist norms of legality".

Views on Stalin in Russian Federation

Results of a controversial poll taken in 2006 stated that over thirty-five percent of Russians would vote for Stalin if he were still alive.[248][249] Fewer than a third of all Russians regarded Stalin as a murderous tyrant;[250] however, a Russian court in 2009, ruling on a suit by Stalin's grandson, Yevgeny Dzhugashvili, against the newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, ruled that referring to Stalin as a "bloodthirsty cannibal" was not libel.[251] In a July 2007 poll 54 percent of the Russian youth agreed that Stalin did more good than bad while 46 percent (of them) disagreed that Stalin was a cruel tyrant. Half of the respondents, aged from 16 to 19, agreed Stalin was a wise leader.[252]

In December 2008 Stalin was voted third in the nationwide television project Name of Russia (narrowly behind 13th century prince Alexander Nevsky and Pyotr Stolypin, one of Nicholas II's prime ministers), leading to accusations from Communist Party of the Russian Federation that the poll had been rigged in order to prevent him or Lenin being given first place.[253]

On 3 July 2009, Russia's delegates walked out of an Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe session to demonstrate their objections to a resolution for a remembrance day for the victims of both Nazism and Stalinism.[254] Only eight out of 385 assembly members voted against the resolution.[254]

In a Kremlin video blog posted on October 29, 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev denounced the efforts of people seeking to rehabilitate Stalin's image. He said the mass extermination during the Stalin era cannot be justified.[255] However, Russian government is promoting school textbooks which say Stalin's reign of terror was entirely rational and necessary to make Russia great,[256] and Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin openly praised his achievements.[257]

Personal life

Origin of name, nicknames and pseudonyms

Stalin's original Georgian is transliterated as "Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili" (Georgian: იოსებ ბესრიონის ძე ჯუღაშვილი). The Russian transliteration of his name (Russian: Иосиф Виссарионович Джугашвили) is in turn transliterated to English as "Iosif Vissarionovich Dzughashvili". Like other Bolsheviks, he became commonly known by one of his revolutionary noms de guerre, of which "Stalin" was only the last. Prior nicknames included "Koba", "Soselo", "Ivanov" and many others.[258]

Stalin is believed to have started using the name "K. Stalin" sometime in 1912 as a pen name.

During Stalin's reign his nicknames included:

- "Uncle Joe", by western media, during and after the World War II.[259][260]

- "Kremlin Highlander" (Russian: кремлевский горец), in reference his Caucasus Mountains origin, notably by Osip Mandelstam in his Stalin Epigram.

- "Little Father of the Peoples" or "Papa Stalin". A common nickname in the USSR during his time in power, as he was portrayed as the paternal figure of the Revolution.[261][262][263][264]

Appearance

While photographs and portraits portray Stalin as physically massive and majestic (he had several painters shot who did not depict him "right")[265], he was only five feet four inches high (160 cm).[265] (President Harry S. Truman, who stood only five feet nine inches himself, described Stalin as "a little squirt".[1]) His mustached face was fleshy and pock-marked, and his black hair later turned grey and thinned out. After a carriage accident in his youth, his left arm was shortened and stiffened at the elbow, while his right hand was thinner than his left and frequently hidden.[265] His dental health also deteriorated as he got older - when he died, he only had three of his own teeth remaining.[266] He could be charming and polite, mainly towards visiting statesmen,[265] but was generally coarse, rude, and abusive.[267] In movies, Stalin was often played by Mikheil Gelovani and, less frequently, by Aleksei Dikiy.