Paul McCartney

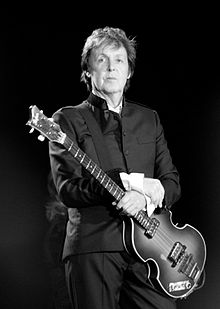

McCartney with his Höfner bass on stage in England in 2010 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Paul McCartney |

| Born | 18 June 1942 Liverpool, England, UK |

| Genres | Rock, pop, classical, electronica |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, music producer, film producer, businessman |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, bass guitar, guitar, keyboards, drums, ukulele, mandolin, recorder |

| Years active | 1957–present |

| Labels | Hear, Apple, Parlophone, Capitol, Columbia, Concord, EMI, One Little Indian, Vee-Jay |

| Website | www |

Sir James Paul McCartney, MBE, Hon RAM, FRCM (born 18 June 1942) is an English musician, singer-songwriter and composer. Formerly of the Beatles (1960–1970) and Wings (1971–1981), he has been described by Guinness World Records as "The Most Successful Composer and Recording Artist of All Time", with 60 gold discs and sales of over 100 million albums and 100 million singles. With John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr, he gained worldwide fame as a member of the Beatles, and with Lennon formed one of the most celebrated songwriting partnerships of the 20th century. After leaving the Beatles, he began a solo career and later formed the band Wings with his first wife, Linda Eastman, and singer-songwriter Denny Laine.

According to the BBC, his Beatles song "Yesterday" has been covered by over 2,200 artists—more than any other song in history, and since its 1965 release, has been played more than seven million times on American television and radio. Wings' 1977 single "Mull of Kintyre" became one of the best-selling singles in UK chart history. As a musician, songwriter, or co-writer, he is included on thirty-one number one singles on the Billboard Hot 100, and he has sold 15.5 million RIAA certified units in the United States as a solo artist.

McCartney has composed film scores, classical and electronic music, released a large catalogue of songs as a solo artist, and has taken part in projects to help international charities. He is an advocate for animal rights, for vegetarianism, and for music education; he is active in campaigns against landmines, seal hunting, and Third World debt. He is a keen football fan, supporting both Everton and Liverpool football clubs. His company MPL Communications owns the copyrights to more than 25,000 songs, including all songs written by Buddy Holly, along with publishing rights to the musicals Guys and Dolls, A Chorus Line, and Grease. McCartney is one of the UK's wealthiest people, with an estimated fortune of £475 million in 2010. He has been married three times and is the biological father of four children.

Childhood

McCartney was born in Walton Hospital in Liverpool England, where his mother, Mary (née Mohin), had "satisfied her state registry requirments" for nursing, twelve years earlier.[1] His father James, or "Jim" McCartney, was absent at his son's birth due to his work as a volunteer fire fighter during World War II.[1] McCartney has one brother, Michael, born 7 January 1944, and though they were baptised in their mother's Roman Catholic faith, "religion did not play a part in their upbringing", as McCartney's father was a Protestant turned agnostic.[2]

In 1947 he began attending Stockton Wood Road Primary School, by 1952 Joseph Williams Junior School,[3] where he passed the 11-plus exam in 1953 with three others out of ninety examinees, thus gaining admission to the Liverpool Institute.[4] In 1954, while taking the bus from his home in the suburb of Speke to the Institute, he met George Harrison.[5] Passing the exam meant they could go to a grammar school rather than a secondary modern school, which the majority of pupils attended until they were eligible to work.[6]

In 1955 the McCartneys moved to 20 Forthlin Road in Allerton, where they lived through 1964.[7] The first member of his family to own a car, his mother rode a bicycle to houses where she worked as a midwife; he describes an early memory her leaving at "about three in the morning" the "streets ... thick with snow".[8] On 31 October 1956, when he was fourteen, his mother died of an embolism after a mastectomy operation to stop the spread of her breast cancer.[9] The early loss of his mother was later a point of relation with John Lennon, whose mother Julia died after being struck by a car when Lennon was seventeen.[10]

His father was a trumpet player and pianist who had led Jim Mac's Jazz Band in the 1920s and encouraged his son to be musical. He kept an upright piano in the front room that he purchased from Epstein's North End Music Stores.[11] His father, Joe McCartney, played an E-flat tuba.[12] Jim McCartney used to point out the bass parts in songs on the radio, and often took his son to local brass band concerts.[13] He gave Paul a nickel-plated trumpet for his fourteenth birthday,[14] but when rock and roll became popular on Radio Luxembourg,[15] he traded it for a £15 Framus Zenith (model 17) acoustic guitar, realizing it would be too difficult to sing, "with a trumpet stuck in your mouth."[14] Being left-handed, he found right-handed guitars difficult to play, but when he saw a poster advertising a Slim Whitman concert, he realised that Whitman played left-handed with his right-handed guitar strung the opposite way. He then restrung his guitar and after some adjustments, found it easier to play.[14] McCartney wrote his first song ("I Lost My Little Girl") on the Zenith, and his second song, "When I'm Sixty-Four", on the piano, which despite his father's advice, he took only a couple of lessons for, preferring instead to learn "by ear."[11] He was heavily influenced by American rhythm and blues music, and has stated that Little Richard was his idol when he was in school. The first song he ever sang "on stage" was "Long Tall Sally", at a Butlins holiday camp talent competition.[16]

Musical career

1957–1960: The Quarrymen

When he was 15, he met Lennon and the Quarrymen at the St. Peter's Church Hall fête in Woolton on 6 July 1957.[17] He joined the group soon after, and formed a close working relationship with Lennon as the pair became one of the most celebrated songwriting partnerships of the 20th century.[18] Harrison joined in early 1958 as lead guitarist, followed in early 1960 by Lennon's art school friend, Stuart Sutcliffe on bass.[19] By May 1960, they had tried several new names, including "Johnny and the Moondogs" and "the Silver Beetles", playing a tour of Scotland under that name with Johnny Gentle. They changed the name of the group to "the Beatles" in mid-August 1960 and recruited Pete Best at short notice to become their drummer for an imminent engagement in Hamburg.[20]

1960–1970: The Beatles

From August 1960, the Beatles were booked by Allan Williams to perform in Hamburg. During their extended stays over the next two years, they performed as the resident group at two of Bruno Koschmider's clubs, and during returns to Liverpool, at the Cavern club.[21] In 1961 Sutcliffe left the band, and McCartney reluctantly[22] became their bass player.[23] The Beatles recorded their first published music in Hamburg, performing as the backing band for Tony Sheridan on the single "My Bonnie".[24] The recording would later bring them to the attention of a key figure in their subsequent development and commercial success, Brian Epstein, who became their manager in January 1962.[25] Epstein eventually negotiated a record contract for the group with Parlophone in May of that year.[26]

After replacing Best with Ringo Starr, they became increasingly popular in the UK during 1963 and in the US in 1964, in a frenzied adolation that became known as "Beatlemania".[27] In 1965, they were each appointed as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[28] After touring almost non-stop for a period of nearly four years, and giving more than 1,400 live performances internationally,[29] the group gave their final commercial concert at the end of their 1966 US tour.[30] They continued to work in the recording studio from 1966 until their break-up in 1970. In the eight years from 1962 to 1970, the group released twenty-two UK singles and twelve studio albums,[31] often released in different configurations in the USA and other countries (see discography).[32] In October 1969, a rumour surfaced that McCartney had died in a car crash, but it was soon proven false when a November Life magazine cover featured McCartney and his family with the caption, "Paul is Still With Us."[33]

1970–1981: Wings

After the break-up of the Beatles, he continued his musical career, releasing his first solo album McCartney in 1970, which contained the stand-out song "Maybe I'm Amazed".[34] In 1971 he worked with his wife Linda McCartney to record a second album, Ram, which included the co-written number one hit, "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey".[35] Later that year, the pair were joined by ex-Moody Blues guitarist Denny Laine and drummer Denny Seiwell to form the group Wings. Active between 1971 and 1981, the group released numerous successful singles and albums.[36]

1982–1989

During the 1980s he collaborated with several popular artists including Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, Eric Stewart, and Elvis Costello.[37] In 1985, McCartney played "Let It Be" at the Live Aid concert in London, backed by Bob Geldof, Pete Townshend, David Bowie, and Alison Moyet.[38] In 1989, he joined forces with fellow Merseysiders including Gerry Marsden of Gerry and the Pacemakers and Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood to record a new version of Ferry Cross the Mersey (originally recorded 25 years earlier by Gerry and the Pacemakers) to generate money for the appeal fund of the Hillsborough disaster, which occurred on 15 April that year and in which ninety-five Liverpool F.C. fans died as a result of their injuries.[39]

1990–2000

During the 1990s McCartney ventured into orchestral music, and in 1991 the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society commissioned a musical piece by him to celebrate its sesquicentennial. He collaborated with Carl Davis to release Liverpool Oratorio; involving opera singers Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Sally Burgess, Jerry Hadley and Willard White, with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and the choir of Liverpool Cathedral.[40] The Prince of Wales later honoured McCartney as a Fellow of The Royal College of Music and Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music (2008). Other forays into classical music included Standing Stone (1997), Working Classical (1999), Ecce Cor Meum (2006), and "Ocean's Kingdom" (2011). In 1994 McCartney, Harrison, and Starr began working together on Apple's The Beatles Anthology documentary series. In December 1996 he was informed that he was to be named in the 1997 New Year Honours and knighted for services to music; his ceremony took place on 11 March 1997.[41] In 1999 he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist, and in May 2000 he was awarded a Fellowship by the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.

2001–present

Having witnessed the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks from the JFK airport tarmac, McCartney took a lead role in organising The Concert for New York City.[42] In November 2002, on the first anniversary of George Harrison's death, McCartney performed at the Concert for George.[43] He has also participated in the National Football League's Super Bowl, performing in the pre-game show for Super Bowl XXXVI and headlining the halftime show at Super Bowl XXXIX.

McCartney continues to work in the realms of popular and classical music, touring the world and performing at a large number of concerts and events; on more than one occasion he has performed with Ringo Starr. In 2008 he received a BRIT award for Outstanding Contribution to Music[44] and an honorary degree, Doctor of Music, from Yale University.[45] The same year, he performed at a concert in Liverpool to celebrate the city's year as European Capital of Culture.[46] In 2009, he received two nominations for the 51st annual Grammy awards, while in October of the same year he was named songwriter of the year at the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) Awards. On 15 July 2009, more than 45 years after the Beatles first appeared on American television on The Ed Sullivan Show, he returned to the Ed Sullivan Theater to perform on Late Show with David Letterman.[47] On 2 June 2010, he was honoured by Barack Obama with the Gershwin Prize for his contributions to popular music in a live show for the White House with performances by Stevie Wonder, Lang Lang and others.[48]

McCartney's enduring popularity has helped him schedule performances in new venues. He played three sold out concerts at newly built Citi Field in Queens, New York (built to replace the iconic Shea Stadium) on 17, 18, and 21 July 2009. On 27 June 2010, McCartney did a benefit concert at Hyde Park for the Born HIV Free foundation. On 18 August 2010, McCartney opened the Consol Energy Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[49] On 15–16 July 2011, McCartney performed the first concerts at the new Yankee Stadium. He has been touring since 2001 with guitarists Rusty Anderson and Brian Ray, Paul "Wix" Wickens on keyboards and drummer Abe Laboriel, Jr. An upcoming tribute album is expected in June 2012, to coincide with his 70th birthday, featuring recordings of his songs by Kiss, Garth Brooks, Billy Joel, Brian Wilson, Willie Nelson, Steve Miller, B.B. King and others.[50] Kisses on the Bottom, a collection of standards, was released on 7 February 2012.[51] McCartney was honoured as MusiCares Person of the Year on 10 February 2012, two days prior to his performance at the 54th Grammy Awards.[52]

Creative outlets

During the 1960s, McCartney delved into the visual arts, becoming a close friend of leading art dealers and gallery owners, explored experimental film, and regularly attended movie, theatrical and classical music performances. His first contact with the London avant-garde scene was through John Dunbar, who introduced him to the art dealer Robert Fraser, who in turn introduced McCartney to an array of writers and artists.[53] McCartney later became involved in the renovation and publicising of the Indica Gallery in Mason's Yard, London — John Lennon first met Yoko Ono at the Indica.[54] The Indica Gallery brought McCartney into contact with Barry Miles, whose underground newspaper, the International Times, McCartney helped to start.[55] Miles would become de facto manager of the Apple's short-lived Zapple Records label,[56] and wrote McCartney's official biography, Many Years From Now (1997).[57]

While living at the Asher house,[58] McCartney took piano lessons at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, which The Beatles' producer Martin had previously attended.[59][60] McCartney studied composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Luciano Berio.[61] McCartney later wrote and released several pieces of modern classical music and ambient electronica, besides writing poetry and painting. McCartney is lead patron of the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, an arts school in the building formerly occupied by the Liverpool Institute for Boys. The 1837 building, which McCartney attended during his schooldays, had become derelict by the mid-1980s, however, on 7 June 1996, Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the redeveloped building.[62]

Electronic music

After the recording of "Yesterday" in 1965, McCartney contacted the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in Maida Vale, London, to see if they could record an electronic version of the song, but never followed it up.[63] When visiting John Dunbar's flat in London, McCartney would take along tapes he had compiled at Jane Asher's house.[64] The tapes were mixes of various songs, musical pieces and comments made by McCartney that he had Dick James make into a demo record for him.[65] Heavily influenced by John Cage, he made tape loops by recording voices, guitars, and bongoes on a Brenell tape recorder, and splicing the various loops together. He reversed the tapes, sped them up, and slowed them down to create the effects he wanted, some of which were later used on Beatles' recordings, such as "Tomorrow Never Knows". McCartney referred to the tapes as "electronic symphonies".[66]

In the spring of 1966 McCartney rented a ground floor and basement flat from Ringo Starr at 34 Montagu Square, to be used as a small demo studio for spoken-word recordings by poets, writers (including William S. Burroughs) and avant-garde musicians.[67] The Beatles' Apple Records then launched a sub-label, Zapple with Miles as its manager, ostensibly to release recordings of a similar aesthetic, although few releases would ultimately result as Apple and The Beatles slid into business and personal difficulties.[67]

In 1995 McCartney recorded a radio series called "Oobu Joobu" for the American network Westwood One, which he described as being "wide-screen radio".[68] During the 1990s, McCartney twice collaborated with Youth of Killing Joke under the name the Fireman, and released the ambient electronic albums: Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest (1993) and Rushes (1998).[69] In 2000, he released an album titled Liverpool Sound Collage with Super Furry Animals and Youth, utilising the sound collage and musique concrète techniques that fascinated him in the mid-1960s. In 2005, he worked on a project with bootleg producer and remixer Freelance Hellraiser, consisting of remixed versions of songs from throughout his solo career which were released under the title Twin Freaks.[70] The Fireman's third album Electric Arguments was released on 25 November 2008. Unlike the first two Fireman albums, this one was more song-based in its structure. McCartney told L.A. Weekly in a January 2009, "Fireman is improvisational theatre ... I formalise it a bit to get it into the studio, and when I step up to a microphone, I have a vague idea of what I'm about to do. I usually have a song, and I know the melody and lyrics, and my performance is the only unknown."[71]

Film

McCartney was interested in animated films as a child, and in 1981 he asked Geoff Dunbar to direct a short animated film called Rupert and the Frog Song. McCartney was the writer and producer and he also added some of the character voices.[72] In 1984 he wrote and starred in the film Give My Regards to Broad Street, and while the film and soundtrack featured the popular hit "No More Lonely Nights", and the album reached No.1 in the UK, the film did not do well commercially or critically.[73] Roger Ebert awarded the film a single star and wrote, "you can safely skip the movie and proceed directly to the sound track."[74] In 1992, Dunbar again worked with McCartney on an animated film about the work of French artist Honoré Daumier, which won both of them a BAFTA award.[75] In 2004, they worked together on the animated short film, Tropic Island Hum.[76] In 1995 he made a guest appearance in the "Lisa the Vegetarian" episode of The Simpsons, and directed a short documentary about The Grateful Dead.[77]

In May 2000, McCartney released Wingspan: An Intimate Portrait, a retrospective documentary that features behind-the-scenes film and photographs that Paul and Linda McCartney (who died in 1998) took of their family and bands.[78] Interspersed throughout the 88 minute film is an interview by Mary McCartney with her father. Mary was the baby photographed inside McCartney's jacket on the back cover of his first solo album, McCartney, and was one of the producers of the documentary.[79]

Painting

In 1966, McCartney met art gallery-owner Robert Fraser, whose flat was visited by many well-known artists.[80] McCartney met Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Peter Blake, and Richard Hamilton there, and learned about art appreciation.[80] McCartney later started buying paintings by Magritte, and used Magritte's painting of an apple for the Apple Records logo.[81] He now owns Magritte's easel and spectacles.[82]

McCartney's love of painting surfaced after watching artist Willem de Kooning paint, in Kooning's Long Island studio.[83] McCartney took up painting in 1983.[84] In 1999, he exhibited his paintings (featuring McCartney's portraits of John Lennon, Andy Warhol, and David Bowie) for the first time in Siegen, Germany, and included photographs by Linda. He chose the gallery because Wolfgang Suttner (local events organiser) was genuinely interested in his art, and the positive reaction led to McCartney showing his work in UK galleries.[85] The first UK exhibition of McCartney's work was opened in Bristol, England with more than 50 paintings on display. McCartney had previously believed that "only people that had been to art school were allowed to paint" – as Lennon had.[85]

In October 2000, Yoko Ono and McCartney presented art exhibitions in New York and London. McCartney said, "I've been offered an exhibition of my paintings at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool where John and I used to spend many a pleasant afternoon. So I'm really excited about it. I didn't tell anybody I painted for 15 years but now I'm out of the closet."[86][87] McCartney designed a series of six postage stamps issued by the Isle of Man Post in 2002, and according to BBC News, he is the first major rock star in the world to do so.[88]

Writing and poetry

When McCartney was young, his mother read him poems and encouraged him to read books. McCartney's father was interested in crosswords and invited the two young McCartneys (Paul and his brother Michael) to solve them with him, so as to increase their "word power".[89] McCartney was later inspired – in his school years – by Alan Durband, who was McCartney's English literature teacher at the Liverpool Institute.[90] Durband was a co-founder and fund-raiser at the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool, where Willy Russell also worked, and introduced McCartney to Geoffrey Chaucer's works.[91] McCartney later took his A-level exams, but passed only one subject – Art.[92][93]

In 2001 McCartney published 'Blackbird Singing', a volume of poems, some of which were lyrics to his songs, and gave readings in Liverpool and New York City.[94] Some of them were serious: "Here Today" (about Lennon) and some humorous ("Maxwell's Silver Hammer").[95] In the foreword of the book, McCartney explained that when he was a teenager, he had "an overwhelming desire" to have a poem of his published in the school magazine. He wrote something "deep and meaningful", but it was rejected, and he feels that he has been trying to get some kind of revenge ever since. His first "real poem" was about the death of his childhood friend, Ivan Vaughan.[94] In 2005 he collaborated with author Philip Ardagh and animator Geoff Dunbar to write, High in the Clouds: An Urban Furry Tail, which The Guardian labeled an "anti-capitalist children's book".[96]

Contact with fellow ex-Beatles

John Lennon

Although his post-Beatles relationship with Lennon was strained, they became close again briefly in 1974, and played together for the only time since the Beatles break-up (see A Toot and a Snore in '74). In later years, the two grew apart again.[97] McCartney would often call Lennon, but was never sure what sort of reception he would get,[98] as when he once called Lennon and was told, "You're all pizza and fairytales!"[98] McCartney reasoned that he could not phone Lennon and talk only about business, so they often talked about cats, baking bread, or babies.[99] According to May Pang, during Lennon's "Lost Weekend" they planned to visit McCartney in New Orleans, where he was recording the Venus and Mars album, but Lennon went back to Ono the day before the planned visit after Ono said she had a new cure for Lennon's smoking habit.[100]

On 24 April 1976,[101] Lennon and McCartney were watching an episode of Saturday Night Live together, during which Lorne Michaels made a $3,000 cash offer for the Beatles to reunite, and while they seriously considered going to the SNL studio, they decided it was "too late" and according to Lennon, this was the last time he and McCartney ever spent time together.[102] This event was fictionalised in the 2000 television film Two of Us.[103] His last telephone call to Lennon, just days before Lennon and Ono released Double Fantasy, was friendly, he said this about the phone call: "Yes. That is a nice thing, a consoling factor for me, because I do feel it was sad that we never actually sat down and straightened our differences out. But fortunately for me, the last phone conversation I ever had with him was really great, and we didn't have any kind of blow-up."[citation needed]

- Reaction to Lennon's murder

On the morning of 9 December 1980, he awoke to the news that Lennon had been murdered the previous night, his death creating a media frenzy around the surviving members of the band.[104] During the evening of 9 December, as he was leaving an Oxford Street recording studio, he was surrounded by reporters and asked for his reaction to Lennon's death. He was later criticised for what appeared, when published, to be a superficial response: "It's a drag".[101] He later explained, "When John was killed somebody stuck a microphone at me and said: 'What do you think about it?' I said, 'It's a dra-a-ag' and meant it with every inch of melancholy I could muster. When you put that in print it says, 'McCartney in London today when asked for a comment on his dead friend said, "It's a drag."' It seemed a very flippant comment to make."[101] He was also to recall:

I talked to Yoko the day after he was killed and the first thing she said was, "John was really fond of you." The last telephone conversation I had with him we were still the best of mates. He was always a very warm guy, John. His bluff was all on the surface. He used to take his glasses down, those granny glasses, and say, "It's only me." They were like a wall, you know? A shield. Those are the moments I treasure.[101]

In 1983, he said: "I would not have been as typically human and standoffish as I was if I knew John was going to die. I would have made more of an effort to try and get behind his "mask" and have a better relationship with him."[101] He said that he went home that night and watched the news on television – while sitting with his children – crying most of the evening. In 1997, he admitted the ex-Beatles were nervous at the time that they might be the "next" one murdered.[105] In 2002 he told Mojo magazine that Lennon was his greatest "hero".[106]

His reluctance to tour after Lennon died led to a disagreement with Denny Laine, who subsequently left Wings, which McCartney disbanded in 1981.[107] In June 1981, six months after Lennon's death, McCartney sang backup on Harrison's tribute to their ex-bandmate, "All Those Years Ago", which also featured Starr on drums.[108] In 1982 McCartney released "Here Today", a song written as a tribute to Lennon.[109]

George Harrison

In late 2001, he learned that Harrison was losing his battle with cancer, and upon his death on 29 November 2001, McCartney issued a statement outside his home in St. John's Wood, calling him "a lovely guy and a very brave man who had a wonderful sense of humour", "We grew up together and we just had so many beautiful times together – that's what I am going to remember. I'll always love him, he's my baby brother."[110] Harrison spent his last days in a Hollywood Hills mansion that was once leased by McCartney.[111] On the first anniversary of his death, McCartney played Harrison's "Something" on a ukulele at the Concert for George.[43] He also performed "For You Blue" and "All Things Must Pass", as well as playing the piano on Eric Clapton's rendition of "While My Guitar Gently Weeps".[112]

Personal relationships

One of his first girlfriends, was called Layla, a name he remembers being unusual in Liverpool in 1959.[113] Layla was slightly older than him and used to ask him to baby-sit with her. Julie Arthur, another girlfriend, was Ted Ray's niece.[113]

Dot Rhone

His first serious girlfriend in Liverpool was Dot Rhone, whom he met at the Casbah club in 1959.[114] According to Beatles biographer Bob Spitz, Rhone feels McCartney had a "compulsion" to control situations, chosing clothes and make-up for Rhone, encouraging her to grow her hair out like Brigitte Bardot's,[115] and at least once insisting she have it re-styled, to disappointing effect.[116] When he first went to Hamburg with the Beatles, he wrote to Rhone regularly, and she accompanied Cynthia Lennon to Hamburg when they played there again in 1962.[117] The couple had a two-and-a-half-year relationship, and were due to marry until Rhone's miscarriage, when according to Spitz, McCartney now "free of obligation", ended the engagement.[118]

Jane Asher

He first met the British actress Jane Asher on 18 April 1963, when a photographer asked them to pose together at a Beatles performance at the Royal Albert Hall in London.[119] The two began a relationship and he took up residence with Asher at her parents' house at 57 Wimpole Street London, where he lived for nearly three years before the couple moved to McCartney's own house in St. John's Wood.[58] He wrote several songs while at the Ashers', including "Yesterday" and several inspired by Asher, among them "And I Love Her", "You Won't See Me", and "I'm Looking Through You".[59] They had a five-year relationship, and planned to marry, but Asher broke off the engagement after she discovered he had become involved with another woman, Francie Schwartz.[120]

Linda McCartney

In 1969 he married American photographer Linda Eastman; he describes their first meeting and subsequent relationship: "We had a lot of fun together ... just the nature of how we are, our favourite thing really is to just hang, to have fun. And Linda's very big on just following the moment."[121] He also added, "We were crazy. We had a big arguement the night before we got married and it was nearly called off ... it's ... miraculous that we made it. But we did."[122] The pair first met in 1967 at a Georgie Fame concert at The Bag O'Nails club,[123] during her UK assignment to take photographs of rock musicians in London.[124] Paul and Linda were both vegetarian and supported the animal rights organisation People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.[125] They had four children – Linda's daughter Heather (leaglly adopted by Paul), Mary, Stella and James – and remained married until Linda's death from breast cancer in 1998.[126]

Heather Mills

In 2002 he married Heather Mills, a former model and anti-landmines campaigner.[127] The couple had a child, Beatrice, in 2003. They separated in May 2006 and were divorced in May 2008. In 2004, he commented on media animosity toward his partners, "They [the British public] didn't like me giving up on Jane Asher", "I married a New York divorcee with a child, and at the time they didn't like that."[128]

Nancy Shevell

McCartney married New Yorker Nancy Shevell in a civil ceremony at Old Marylebone Town Hall, London on 9 October 2011. The wedding was a "low-key affair" attended by a group of around 30 family and friends.[129] The couple had been dating since November 2007.[130] A breast cancer survivor,[131] she is a member of the board of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority as well as vice president of a family-owned transportation conglomerate which owns New England Motor Freight.[132]

Lifestyle

Drug use

His introduction to drugs started in Hamburg Germany when the Beatles would play for long hours and were often using Preludin to maintain energy, sometimes supplied by friend Astrid Kirchherr. According to McCartney, he would usually take only one, but Lennon would often take four or five by the end of a night.[133] He remembers getting "very high" and "giggling uncontrollably" when the Beatles were introduced to marijuana by Bob Dylan in a New York hotel room in 1964.[134] His use of which soon after became habitual, and according to biographer Barry Miles, any future Beatles' lyrics containing the words "high", or "grass" were written specifically as a reference to cannabis, as was the phrase "another kind of mind" in "Got to Get You into My Life".[135] Artist John Dunbar's flat at 29 Lennox Gardens, in London, became a regular hang-out for McCartney, where he talked to musicians, writers and artists, while smoking marijuana.[65] In 1965, Miles introduced him to hash brownies by using a recipe for hash fudge he found in the Alice B. Toklas Cookbook.[136] During the filming of Help!, he claims he occasionally smoked a spliff in the car on the way to the studio during filming, which often made him forget his lines.[137] Director Dick Lester says that he overheard "two beautiful women" trying to cajole McCartney into using heroin, but he refused.[137] He was introduced to cocaine by Robert Fraser, and it was available during the recording of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[138] He admitted that he used the drug multiple times for about a year but stopped because of the unpleasant melancholy he felt after the drug wore off.[139]

While initially reluctant to try LSD, he eventually did so in the fall of 1966 with friend Tara Browne.[140] He took his second "acid trip" with Lennon on 21 March 1967 after a Sgt. Pepper studio session.[141] He later became the first Beatle to discuss the drug publicly, declaring in a magazine interview that "it opened my eyes" and "made me a better, more honest, more tolerant member of society."[142] His attitude about cannabis was made public in 1967, when he added his name to a 24 July advertisement in The Times which called for its legalisation, the release of all prisoners imprisoned because of possession, and research into marijuana's medical uses. The advertisement was produced by a group called Soma and was signed by sixty-five people, including Members of Parliment, the Beatles, Epstein, RD Laing, Francis Crick, and Graham Greene.[143]

Though never arrested by Norman Pilcher's Drug Squad, as Lennon, Harrison, and Mick Jagger had been,[144] in 1972 Swedish police fined him for cannabis possesion, and soon after Scottish police found plants growing on his farm.[145] He was again arrested for marijuana possesion in 1975, and in January 1980, Wings went to Tokyo for an eleven concert tour of Japan. However, as McCartney was going through customs, officials found approximately 8 ounces (218.3 g) of cannabis in his luggage, and he was arrested and taken to a local jail while the Japanese government decided what to do. After ten days in jail, he was released without charge and deported.[146] He was again arrested for possesion of marijuana in 1984 and in 1997, he spoke out in support of decriminalisation, stating "People are smoking pot anyway and to make them criminals is wrong."[147] In 2004 he stated: "I don't actually smoke the stuff these days", and "It's something I've kind of grown out of." Though he added: "To me, it's a huge compliment that a bunch of kids think I might be up to smoke a bit of dope with them."[148] He also admitted to smoking heroin once, and using LSD and cocaine occasionally but said his drug use was "never excessive".[148]

Meditation

On 24 August 1967, McCartney met the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at the London Hilton, and later went to Bangor, in North Wales, to attend a weekend 'initiation' conference, at which time he and the other Beatles learned Transcendental Meditation (TM).[149] "The whole meditation experience was very good and I still use the mantra ... I find it soothing and I can imagine that the more you were to get into it, the more interesting it would get."[150] The time McCartney later spent in India at the Maharishi's ashram was highly productive, as nearly all of the songs that would later be recorded for The White Album and Abbey Road were composed there.[151] Although he was told never to repeat the mantra to anyone else, he admitted he told Linda, and said he meditated a lot while he was in jail in Japan.[152] In 2009 McCartney and Starr headlined a benefit concert at Radio City Music Hall, raising three million dollars for the David Lynch Foundation to fund instruction in Transcendental Meditation for at-risk youth.[153]

Activism

Paul and Linda McCartney became outspoken animal rights activists after their vegetarianism was realised when Paul happened to see lambs in a field as they ate a meal of lamb.[154] He has also credited the 1942 Disney film Bambi – in which the young deer's mother is shot by a hunter – as the original inspiration for him to take an interest in animal rights.[155] In his first interview after Linda's death, he promised to continue working for animal rights.[156][157]

In 1999 he spent £3,000,000 to ensure Linda McCartney Foods remained free of genetically engineered ingredients.[158] In 2002, McCartney gave his support to a campaign against a proposed ban on the sale of certain vitamins, herbs, and mineral products in the European Union.[159] Following his marriage to Heather Mills, McCartney joined her in a campaign against landmines. Both McCartney and Mills are patrons of Adopt-A-Minefield.[160][161] In 2003, McCartney played a personal concert for the wife of a wealthy banker and donated his one million dollar fee to the charity.[162] He also wore an anti-landmines t-shirt during the Back in the World tour.[161]

In 2006 the McCartneys travelled to Prince Edward Island to bring international attention to the seal hunt (their final public appearance together). Their arrival sparked attention in Newfoundland and Labrador where the hunt is of economic significance.[163] The couple also debated with Newfoundland's Premier Danny Williams on the CNN show Larry King Live. They further stated that the fishermen should quit hunting seals and begin a seal watching business.[164] McCartney has also criticised China's fur trade[165][166] and supports the Make Poverty History campaign.[167]

McCartney has been involved with a number of charity recordings and performances. In 2004, he donated a song to an album to aid the "US Campaign for Burma", in support of Burmese Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi,[168] and he had previously been involved in the Concerts for the People of Kampuchea, Ferry Aid, Band Aid, Live Aid, and the recording of "Ferry Cross the Mersey" (released 8 May 1989) following the Hillsborough disaster.[169][170] In 2008 he donated a song to Aid Still Required's CD to assist with the restoration of the devastation done to Southeast Asia from the 2004 Tsunami.[171]

In a December 2008 interview with Prospect Magazine, he mentioned that he tried to convince the Dalai Lama to become a vegetarian. In a letter to the Dalai Lama, McCartney took issue with Buddhism and meat-eating being considered compatible, saying, "Forgive me for pointing this out, but if you eat animals then there is some suffering somewhere along the line." The Dalai Lama responded, saying his doctors advised him to eat meat for health reasons. In the interview McCartney said, "I wrote back saying they were wrong."[172]

Football

The Beatles were advised by Epstein to make no comments about the football clubs they supported because it could alienate some fans, though it was well known that McCartney was a supporter of Everton Football Club, and that his father and relatives used to take him to matches.[173][174] His allegiance later shifted to Liverpool F.C.,[175] as on 28 July 1968, The Beatles were photographed in a photographer's studio at 192–212 Gray's Inn Road, with McCartney wearing a Liverpool F.C. rosette.[176] Linda McCartney later said: "We spent last night listening to Liverpool football team on the radio, wanting them to win so badly. Paul supports Liverpool. He was for Everton for a while because of his family — but it's all Liverpool now."[177][178]

Lennon and McCartney were present to watch the 1966 FA Cup Final at Wembley, between Everton and Sheffield Wednesday, and McCartney attended the 1968 FA Cup Final (18 May 1968) which was played by West Bromwich Albion against Everton.[179] After the end of the match, McCartney shared cigarettes and whisky with other football fans.[178] The ex-Liverpool player, Albert Stubbins, was the only footballer shown on the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band cover.[174] McCartney tried to listen (on a radio) to the Liverpool v Manchester United 1977 FA Cup Final, while sailing in the Caribbean,[174] and the video for McCartney's "Pipes of Peace" (in 1983) recreated the 1915 football game played between German and British troops during World War I, at Christmas.[180][181]

At the end of the live version of "Coming Up" recorded in Glasgow in 1979 (later to become a US number one single) the crowd begins to sing "Paul McCartney!" until McCartney takes over and changes the chant to "Kenny Dalglish!", referring to the current Liverpool and Scotland striker. At the same concert, Gordon Smith, former football player who played for Rangers and Brighton & Hove Albion, met the McCartneys, and later accepted an invitation to visit their home in East Sussex in 1980. Smith later said that McCartney was "thrilled I knew Kenny Dalglish", to which Linda added: "I like Gordon McQueen of Man United", and Smith replied, "I know him too."[182]

McCartney attended the 1986 FA Cup Final between Liverpool and Everton,[178] and in 1989, he contributed to the "Ferry Cross the Mersey" charity single that was recorded to aid victims of the Hillsborough Disaster, which happened during a match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.[39] McCartney performed at the Liverpool F.C. Anfield stadium on 1 June 2008, as a part of Liverpool's European Capital of Culture year.[183] Dave Grohl from the Foo Fighters sang with McCartney on "Band on the Run", and played drums on "Back in the U.S.S.R.". Ono and Olivia Harrison attended the concert, along with Ken Dodd, and the former Liverpool F.C. football manager Rafael Benítez.[184][185][186] In an interview in 2008, McCartney ended speculation about his allegiance when he said:

"Here's the deal: my father was born in Everton, my family are officially Evertonians, so if it comes down to a derby match or an FA Cup final between the two, I would have to support Everton. But after a concert at Wembley Arena I got a bit of a friendship with Kenny Dalglish, who had been to the gig and I thought 'You know what? I am just going to support them both because it's all Liverpool and I don't have that Catholic-Protestant thing.' So I did have to get special dispensation from the Pope to do this but that's it, too bad. I support them both. They are both great teams, but if it comes to the crunch, I'm Evertonian."[187]

In 2010, there was heavy speculation surrounding McCartney that he was to head up a consortium launching a take-over bid for struggling Charlton Athletic. Links between the club and the famous musician go a long way back with Charlton's famous supporters anthem – Valley, Floyd Road – using the tune and a number of lyrics from the Wings song "Mull of Kintyre".[188]

Business

McCartney is one of the UK's wealthiest people, with an estimated fortune of £475 million in 2010.[189] In addition to his interest in Apple Corps, McCartney's MPL Communications owns a significant music publishing catalogue, with access to over 25,000 copyrights.[190] McCartney earned £40 million in 2003, making him Britain's highest media earner.[191] This rose to £48.5 million by 2005.[192] MPL Communications is an umbrella company for McCartney's business interests, which owns a wide range of copyrights,[193] as well as the publishing rights to musicals.[194] In 2006, the Trademarks Registry reported that MPL had started a process to secure the protections associated with registering the name "Paul McCartney" as a trademark.[195] The 2005 films, Brokeback Mountain[196] and Good Night, and Good Luck, feature MPL copyrights.[197] In April 2009 it was revealed that McCartney, in common with other wealthy musicians, had seen a significant decline in his net worth over the preceding year. It was estimated that his fortune had fallen by some £60m, from £238m to £175m.[198] The losses were attributed to the ongoing global recession, and the resultant decline in value of property and stock market holdings.[198]

Northern Songs

Northern Songs was established in 1963, by Dick James, to publish the songs of Lennon–McCartney.[199] The Beatles' partnership was replaced in 1968 by a jointly held company, Apple Corps, which continues to control Apple's commercial interests. Northern Songs was purchased by Associated Television (ATV) in 1969, and was sold in 1985 to Michael Jackson. For many years McCartney was unhappy about Jackson's purchase and handling of Northern Songs.[200]

Critique, recognition and achievements

In 1979 he was described by Guinness World Records as "The Most Successful Composer and Recording Artist of All Time", with 60 gold discs and sales of 100 million albums and 100 million singles, with a writer's credit on forty-three songs that have sold over one million copies each.[201] According to Guinness, "Sir Paul McCartney became the Most Successful Songwriter who has written/co written 188 charted records, of which 91 reached the Top 10 and 33 made it to No.1 totalling 1,662 weeks on the chart (up to the beginning of 2008)."[202] In 1986 he received acclaim from the Guinness Book of Records Hall of Fame, "as the most successful musician of all-time."[203]

In the US, as a musician, songwriter, or co-writer, McCartney is included on thirty-one number one singles on the Billboard Hot 100; including twenty with the Beatles, nine solo,[204] one as a co-writer on Elton John's cover of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds",[205] and one as a co-writer of "A World Without Love", a number one single for Peter and Gordon.[206][207][208] He has sold 15.5 million RIAA certified units in the United States.[209]

In the UK, McCartney has been involved in more number-one singles than any other artist under a variety of credits, although Elvis Presley has achieved more as a solo artist. McCartney has twenty four number-one singles in the UK, including seventeen with the Beatles, one solo, and one each with Wings, Stevie Wonder, Ferry Aid, Band Aid, Band Aid 20 and one with "The Christians et all". McCartney is the only artist to reach the UK number one as a soloist ("Pipes of Peace"), duo ("Ebony and Ivory" with Stevie Wonder), trio ("Mull of Kintyre", Wings), quartet ("She Loves You", The Beatles), quintet ("Get Back", The Beatles with Billy Preston), and as part of a musical ensemble for charity (Ferry Aid).[210]

In 1999, McCartney was voted the "Greatest Composer of the Millennium" by BBC News Online readers and McCartney's song "Yesterday" is thought to be the most covered song in history with more than 2,200 recorded versions,[211] and according to the BBC, "The track is the only one by a UK writer to have been aired more than seven million times on American TV and radio and is third in the all-time list. Sir Paul McCartney's Yesterday is the most played song by a British writer this century in the US."[212] Released in 1977, the Wings song "Mull of Kintyre" "became the best-selling single in UK history".[213][214] On 2 July 2005, he was involved with the fastest-released single in history, when his performance of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" with U2 at Live 8 was released only 45 minutes after it was performed.[215] The single reached number six on the Billboard charts, just hours after the single's release, and hit number one on numerous online download charts across the world.[216] McCartney played for the largest stadium audience in history when 184,000 people paid to see him perform at Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on 21 April 1990.[217]

McCartney's scheduled concert in St Petersburg, Russia was his 3,000th concert and took place in front of 60,000 fans in Russia, on 20 June 2004.[218] Over his career, McCartney has played 2,523 gigs with The Beatles, 140 with Wings, and 325 as a solo artist.[219] Only his second concert in Russia, with the first just the year before on Moscow's Red Square as the former Communist U.S.S.R. had previously banned music from The Beatles as a "corrupting influence", McCartney hired three jets, at a reported cost of $36,000 (€29,800) (£28,000), to spray dry ice in the clouds above Saint Petersburg's Winter Palace Square in a successful attempt to prevent rain.[220] The day McCartney flew into the former Soviet Union, he celebrated his 62nd birthday, and after the concert, according to RIA Novosti news agency, he received a phone call from a fan; then-President Vladimir Putin, who telephoned him after the concert to wish him a happy birthday.

In the concert programme for his 1989 world tour, McCartney wrote that Lennon received all the credit for being the avant-garde Beatle,[55] and McCartney was known as "baby-faced", which he disagreed with.[221] People also assumed that Lennon was the "hard-edged one", and McCartney was the "soft-edged" Beatle,[10] although McCartney admitted to "bossing Lennon around."[222] Linda McCartney said that McCartney had a "hard-edge" – and not just on the surface – which she knew about after all the years she had spent living with him.[10][223] McCartney seemed to confirm this edge when he commented that he sometimes meditates, which he said is better than "sleeping, eating, or shouting at someone".[224]

The minor planet 4148, discovered in 1983, was named "McCartney" in his honour,[225] and on 18 June 2006, McCartney celebrated his 64th birthday, a milestone that was the subject of the second song he ever wrote, at the age of sixteen, the Beatles' song "When I'm Sixty-Four".[226] Paul Vallely noted in The Independent:

Paul McCartney's 64th birthday is not merely a personal event. It is a cultural milestone for a generation. Such is the nature of celebrity, McCartney is one of those people who has represented the hopes and aspirations of those born in the baby-boom era, which had its awakening in the Sixties.[227]

McCartney received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on 9 February 2012, the last of the "Fab Four" to receive the honor.[228] McCartney received the MusiCares Person of the Year honour on 10 February 2012.[52]

Discography

Tours

Arms

|

|

Citations

- ^ a b Spitz 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 4.

- ^ "Beatle's schoolboy photo auction". BBC. 16 August 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 9.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Miles 1997, p. 31.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Miles 1997, p. 21.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 509, 533–534.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles: Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 17–25.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 21–25, 31.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 74.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 89, 94.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Miles 1989, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 330.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 75, 88–94, 136–140.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, p. 180.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 347.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 293–295.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 593–594.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 556–563.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 740, 872–873.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 904–910.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 272–273, 311, 361–362, 456–459, 776–777, 820, 894, 919–920.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 514–515.

- ^ a b Harry 2002, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 526–528.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 268–270.

- ^ a b Doggett 2009, pp. 332–333.

- ^ "Sir Paul McCartney picks up special Brit award in London". UK: NME. 20 February 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Yale gives Paul McCartney honorary music degree". USA Today. 26 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Paul McCartney Treats Liverpool to "A Day in the Life" Live Debut". Rolling Stone. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Paul McCartney Stuns Manhattan With Set on Letterman's Marquee". Rolling Stone. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (2 June 2010). "McCartney Is Honored at White House". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mervis, Scott (14 June 2010). "Paul McCartney sells out two shows at Consol". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Joel among stars recording McCartney tribute album". Orange News. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Paul McCartney – Kisses On The Bottom". paulmccartney.com. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Paul McCartney Is 2012 MusiCares Person Of The Year". grammy.com. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 307.

- ^ Harry 2000a, pp. 549–550.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 232.

- ^ Harry 2000a, pp. 1196–1198.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 549–550.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 106.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 108.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 254.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 597.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 517–526.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 207.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 218.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 217.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 219–220.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Rogers, Georgie (19 November 2008). "Sir Paul gears up for The Fireman". BBC. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Raymer 2010, p. 82.

- ^ Mckenna, Kristine (14 January 2009). "Paul McCartney: A Fireman Interviewed". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 767.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 368–374, 646–647.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1 January 1984). "Give My Regards to Broad Street review". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "McCartney releases frog follow-up". BBC News. 29 February 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 862.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 386–387, 789.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 914.

- ^ Lewisohn 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 243.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 256–267.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 84.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 266.

- ^ a b "McCartney gets arty". BBC. 30 April 1999. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ "McCartney and Yoko art exhibitions, 20 October 2000". BBC News. 20 October 2000. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Walker Gallery Exhibition: 24 May – 4 August 2002". liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "McCartney stamps to go on sale". BBC. 18 February 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 42.

- ^ a b Horovitz, Michael (14 October 2006). "Roll over, Andrew Motion". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Harry 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Merritt, Stephanie (17 December 2005). "It took him years to write ..." The Guardian. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Miles 1997, p. 587.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 588.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 590.

- ^ Friedman, Roger (25 September 2001). "Beatles: Lennon planned to meet McCartney in 1974". Fox News. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Harry 2002, p. 505.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 592.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 869–870.

- ^ Carlin 2009, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 594.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 506.

- ^ Lewisohn 2002, p. 168.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 412–413.

- ^ Poole, Oliver; Davies, Hugh (1 December 2001). "I'll always love him, he's my baby brother, says tearful McCartney". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Harrison death mystery solved". BBC News. 13 February 2002. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Harry 2003, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 69.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 348.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 27–32, 777–778.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 514–515.

- ^ miles 1997, p. 525.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 432–434.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 716–718, 880–882.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 585–601.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 568–578.

- ^ "McCartney's lament: I can't buy your love". Sydney Morning Herald. 12 June 2004.

- ^ "Sir Paul McCartney marrying for the third time". BBC News. 9 October 2011.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (7 November 2007). "Former Beatle Linked to Member of M.T.A. Unit". New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Smith, Emily (7 November 2007). "Macca's Nancy fought cancer". The Sun (United Kingdom). Retrieved 2 December 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nancy Shevell – Vice President – Administration". NEMF.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 190.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 247.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 382.

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 228.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 386–387.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 712–713.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 395.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 459–461.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 300–307.

- ^ a b "Sir Paul reveals Beatles drug use". BBC News. 2 June 2004. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, p. 261.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 396.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 397.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 396, 404.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (6 April 2009). "Just Say 'Om': The Fab Two Give a Little Help to a Cause". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 880–882.

- ^ "'Bambi' was cruel". BBC News. 12 December 2005. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ "McCartney vows to keep animal rights torch alight". BBC News. 5 August 1998. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ "Babe actor arrested after protest". BBC News. 4 July 2001. Retrieved 3 January 2010. passim

- ^ "GM-free ingredients". BBC News. 10 June 1999. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "Protest at ban on 'mineral' products". BBC News. 19 November 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "McCartney calls for landmine ban". BBC News. 20 April 2001. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b "McCartney divorce battle: The full judgement part 2". Daily Mail. UK. 18 March 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "McCartney plays for Ralph Whitworth". BBC News. 24 February 2003. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "Paul and Heather call for seal cull ban, Friday, 3 March 2006". BBC News. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ "Interview transcript, McCartney and Heather, Larry King Live, Seal cull". CNN. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Addison, Adrian (28 November 2005). "McCartney attacks China over fur". BBC News. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "No-one is Beatle proof". BBC News. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ "Make Poverty History". Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ "US campaign for Burma protest". BBC News. 20 June 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Concert for Kampuchea". Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ "Ferry Aid Single covers". 9 November 2006.

- ^ "Aid Still Required". Retrieved 3 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher Aid Still Required" ignored (help) - ^ "Paul McCartney".

- ^ "Macca's a blue". Everton Football Club. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Aldred, Tanya; Ingle, Sean (11 December 2003). "Did The Beatles Like Football?". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Chapple, Mike (1 July 2008). "Revealed – secret life of ex-Beatle Paul McCartney as Everton fan". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Did The Beatles Hide Their Footballing Love Away?". Haymarket Media Group. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "Football and the Beatles: The Easily-Uncovered Truth". The Run of Play. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Ingle, Sean; Turner, Georgina; Aldred), Tanya (9 January 2004). "The Beatles and Football: Part Two". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Tennant 2002, p. 274.

- ^ Murray, Scott (21 December 2007). "Joy of Six: Great Christmas Matches". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "The German View of Events – including the Football Match (by Leutnant Johannes Niemann, 133rd Royal Saxon Regiment)". Tom Morgan. December 1997. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "We Loved Them, Yeah Yeah, Yeah". DailyRecord. 9 November 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Reynolds, Gillian (2 June 2008). "Sir Paul McCartney rocks Anfield stadium". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (2 June 2008). "Sir Paul McCartney, Anfield Stadium, Liverpool: Macca's long and winding road brings him home". The Independent. London. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (2 June 2008). "Paul McCartney — Anfield". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Jones, Catherine (31 May 2008). "Paul McCartney: Anfield Liverpool Sound gig will be just like playing to my mates". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Prentice, David (5 July 2008). "Sir Paul McCartney's Everton 'secret' was no surprise". Everton Banter. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Paul McCartney to head up Charlton consortium bid". BBC. 6 June 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ "Sunday Times Rich List 2010: Music millionaires". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 24 April 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Sir Paul is 'pop billionaire'". BBC News. 6 January 2002. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "McCartney tops media rich list". BBC News. 30 October 2003. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "48 million in 2005". London: The Telegraph. 18 May 2006. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "MPL music publishing". Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "McCartney and the Musical "Grease"". localaccess.com. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ Muir, Hugh (14 October 2006). "Paul McCartney Trademark". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Brokeback Mountain web page". brokebackmountain.com. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Goodnight and Good Luck". warnerbros.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ a b "Sir Paul McCartney hit by recession". idiomag. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 365.

- ^ "McCartney talking about the Beatles catalogue". contactmusic.com. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ Harry 2002, pp. 388–389.

- ^ "Guinness World Records Launches 2009 Edition". Guinness World Records. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 388.

- ^ "Most No. 1s By Artist (All-Time)". Billboard.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Chart History: Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds – Elton John". Billboard.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Peter & Gordon". Billboard.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Harry 2002, p. 922.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 250.

- ^ "Top Selling Artists". RIAA. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Roberts, David, ed. (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19 ed.). Guinness World Records Limited. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-904994-10-7.

- ^ "Sir Paul is Your Millennium's greatest composer". BBC. 3 May 1999. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "McCartney's Yesterday earns US accolade". BBC. 17 December 1999. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Doggett 2009, p. 264.

- ^ Carlin 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Live 8 (DVD) Various Artists, 7 November 2005, Cat. No: ANGELDVD5

- ^ "Live 8 single". BBC. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Badman 1999, p. 444.

- ^ "Sir Paul hits 3,000 in Russia". BBC. 20 June 2004. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ "3,000 concerts played". BBC. 20 June 2004. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ "McCartney stops rain in Russia". Special Events. 23 June 2004. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 11.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 32.

- ^ "Macca buys Linda tapes for £200,000". Daily Mail. UK. 5 November 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 404.

- ^ "Minor planet number 4148 has been named in honor of former Beatle Paul McCartney". IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 319.

- ^ "Paul McCartney: When I'm 64 (by Paul Vallely)". The Independent. UK. 16 June 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Sinha, Piya (9 February 2012). "Paul McCartney finally gets Walk of Fame star". Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Ex-Beatle granted coat of arms". BBC News: World Edition. 22 December 2002. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

Sources

- Babiuk, Andy (2002). Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four's Instruments, from Stage to Studio. Backbeat UK/Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-662-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Badman, Keith (1999). The Beatles After the Breakup 1970–2000: A Day-by-Day Diary (2001 ed.). London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-0-711-98307-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002). The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carlin, Peter Ames (2009). Paul McCartney: A Life. Touchstone. ISBN 978-1-4165-6209-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coleman, Ray (1992). Lennon: the definitive biography (Rev/Upd ed.). HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-098608-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Hunter (2006). The Beatles: The Authorized Biography (revised ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32886-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doggett, Peter (2009). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup (1st US hardcover ed.). New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-177446-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America (1 ed.). Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-35338-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Gracen, Jorie B. (2000). Paul McCartney: I Saw Him Standing There. Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 978-0-8230-8372-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harry, Bill (2000a). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Revised and Updated. Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-0481-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harry, Bill (2003). The George Harrison Encyclopedia. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harry, Bill (2000b). The John Lennon Encyclopedia. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-0404-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harry, Bill (2002). The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0716-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewisohn, Mark (1992). The Complete Beatles Chronicle:The Definitive Day-By-Day Guide To The Beatles' Entire Career (Revised 2010 ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-534-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewisohn, Mark (2002). Wingspan. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-86032-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McGee, Garry (2003). Band on the Run: A History of Paul McCartney and Wings. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87833-304-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miles, Barry (1997). Many Years From Now (1 ed.). Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-5248-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miles, Barry (1989). The Beatles Diary. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-6315-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary: After the Break-Up 1970–2001 (revised ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peel, Ian (2002). The Unknown Paul McCartney. Reynolds & Hearn. ISBN 978-1-903111-36-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raymer, Miles (2010). How to Analyze the Music of Paul McCartney. Abdo Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-61613-531-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sounes, Howard (2011). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82047-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Southall, Brian; Perry, Rupert (contributor) (2006). Northern Songs: The True Story of the Beatles Song Publishing Empire. internal; consistency: Omnibus. ISBN 978-1-84609-237-4.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-80352-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tennant, John (2002). Football the Golden Age: A Collection of Over 250 Extraordinary Images. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-84403-115-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Gambaccini, Paul (1993). Paul McCartney: In His Own Words. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-86001-239-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gambaccini, Paul (1996). The McCartney Interviews: After the Break-Up (2 ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-5494-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lennon, Cynthia (1980). A Twist of Lennon. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-45450-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lennon, Cynthia (2006). John. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-33856-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pawlowski, Gareth L. (1989). How They Became The Beatles (1st ed.). E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-24823-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Official website

- Paul McCartney's Animation Website

- Paul McCartney Ecce Cor Meum audio Podcast

- Paul McCartney: Financial Accounts

- Paul McCartney at IMDb

- Use dmy dates from February 2012

- Paul McCartney

- 1942 births

- English male singers

- English multi-instrumentalists

- English pop singers

- English rock bass guitarists

- English rock guitarists

- English rock pianists

- English rock singers

- English singer-songwriters

- English people of Irish descent

- English vegetarians

- Backing vocalists

- 20th-century classical composers

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- Brit Award winners

- Capitol Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Ivor Novello Award winners

- Knights Bachelor

- Singers awarded knighthoods

- Composers awarded knighthoods

- Musicians awarded knighthoods

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- Parlophone artists

- Mercury Records artists

- People convicted of drug offenses

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees

- The Beatles members

- The Quarrymen members

- Wings members

- Living people

- Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music

- Transcendental Meditation practitioners

- People educated at Liverpool Institute High School for Boys

- Silver Clef Awards winners

- Animal rights advocates

- MusiCares Person of the Year