Sustainable energy

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Sustainable energy is the sustainable provision of energy that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Technologies that promote sustainable energy include renewable energy sources, such as hydroelectricity, solar energy, wind energy, wave power, geothermal energy, and tidal power, and also technologies designed to improve energy efficiency.

Definitions

Energy efficiency and renewable energy are said to be the twin pillars of sustainable energy.[1] Some ways in which sustainable energy has been defined are:

- "Effectively, the provision of energy such that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. ...Sustainable Energy has two key components: renewable energy and energy efficiency." – Renewable Energy and Efficiency Partnership (British)[2]

- "Dynamic harmony between equitable availability of energy-intensive goods and services to all people and the preservation of the earth for future generations." And, "the solution will lie in finding sustainable energy sources and more efficient means of converting and utilizing energy." – Sustainable energy by J. W. Tester, et al., from MIT Press.

- "Any energy generation, efficiency & conservation source where: Resources are available to enable massive scaling to become a significant portion of energy generation, long term, preferably 100 years.." – Invest, a green technology non-profit organization.[3]

- "Energy which is replenishable within a human lifetime and causes no long-term damage to the environment." – Jamaica Sustainable Development Network[4]

This sets sustainable energy apart from other renewable energy terminology such as alternative energy and green energy, by focusing on the ability of an energy source to continue providing energy. Sustainable energy can produce some pollution of the environment, as long as it is not sufficient to prohibit heavy use of the source for an indefinite amount of time. Sustainable energy is also distinct from Low-carbon energy, which is sustainable only in the sense that it does not add to the CO2 in the atmosphere.

Green Energy is energy that can be extracted, generated, and/or consumed without any significant negative impact to the environment. The planet has a natural capability to recover which means pollution that does not go beyond that capability can still be termed green.

Green power is a subset of renewable energy and represents those renewable energy resources and technologies that provide the highest environmental benefit. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency defines green power as electricity produced from solar, wind, geothermal, biogas, biomass, and low-impact small hydroelectric sources. Customers often buy green power for avoided environmental impacts and its greenhouse gas reduction benefits.[5]

The importance of sustainable energy

Sustainable energy is important because of the benefits it provides. The key benefits are:

- Environmental: Sustainable energy technologies are clean sources of energy that have a much lower environmental impact than conventional energy technologies. They do not emit any greenhouse gases making the world a cleaner and safer place. Sustainable energy can avoid and reduce air emissions as well as water consumption, waste, noise and adverse land-use impacts.

- Energy for future generations: Renewable energy will never run out. Renewables avoid the rapid depletion of fossil fuel reserves and will empower future generations to deal with the environmental impact of over-dependence on fossil fuels.

- Jobs: Renewable energy projects can bring economical benefits to remote communities, as many renewable energy plants are situated away from large cities. The development and installation of sustainable energy systems creates jobs, regional development and long term economic growth.

- Energy security: Lessens our dependence on fossil and imported fuels.[6]

Renewable energy technologies

Renewable energy technologies are essential contributors to sustainable energy as they generally contribute to world energy security, reducing dependence on fossil fuel resources,[7] and providing opportunities for mitigating greenhouse gases.[7] The International Energy Agency states that:

Conceptually, one can define three generations of renewables technologies, reaching back more than 100 years .

First-generation technologies emerged from the industrial revolution at the end of the 19th century and include hydropower, biomass combustion, and geothermal power and heat. Some of these technologies are still in widespread use.

Second-generation technologies include solar heating and cooling, wind power, modern forms of bioenergy, and solar photovoltaics. These are now entering markets as a result of research, development and demonstration (RD&D) investments since the 1980s. The initial investment was prompted by energy security concerns linked to the oil crises (1973 and 1979) of the 1970s but the continuing appeal of these renewables is due, at least in part, to environmental benefits. Many of the technologies reflect significant advancements in materials.

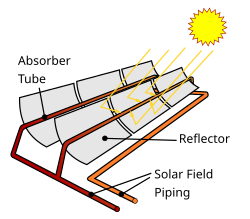

Third-generation technologies are still under development and include advanced biomass gasification, biorefinery technologies, concentrating solar thermal power, hot dry rock geothermal energy, and ocean energy. Advances in nanotechnology may also play a major role.

— International Energy Agency, RENEWABLES IN GLOBAL ENERGY SUPPLY, An IEA Fact Sheet[7]

First- and second-generation technologies have entered the markets, and third-generation technologies heavily depend on long term research and development commitments, where the public sector has a role to play.[7]

A 2008 comprehensive cost-benefit analysis review of energy solutions in the context of global warming and other issues ranked wind power combined with battery electric vehicles (BEV) as the most efficient, followed by concentrated solar power, geothermal power, tidal power, photovoltaic, wave power, coal capture and storage, nuclear energy, and finally biofuels.[8]

First-generation technologies

First-generation technologies are most competitive in locations with abundant resources. Their future use depends on the exploration of the available resource potential, particularly in developing countries, and on overcoming challenges related to the environment and social acceptance.

— International Energy Agency, RENEWABLES IN GLOBAL ENERGY SUPPLY, An IEA Fact Sheet[7]

Among sources of renewable energy, hydroelectric plants have the advantages of being long-lived—many existing plants have operated for more than 100 years. Also, hydroelectric plants are clean and have few emissions. Criticisms directed at large-scale hydroelectric plants include: dislocation of people living where the reservoirs are planned, and release of significant amounts of carbon dioxide during construction and flooding of the reservoir.[9]

However, it has been found that high emissions are associated only with shallow reservoirs in warm (tropical) locales, and recent innovations in hydropower turbine technology are enabling efficient development of low-impact run-of-the-river hydroelectricity projects.[10] Generally speaking, hydroelectric plants produce much lower life-cycle emissions than other types of generation. Hydroelectric power, which underwent extensive development during growth of electrification in the 19th and 20th centuries, is experiencing resurgence of development in the 21st century. The areas of greatest hydroelectric growth are the booming economies of Asia. China is the development leader; however, other Asian nations are installing hydropower at a rapid pace. This growth is driven by much increased energy costs—especially for imported energy—and widespread desires for more domestically produced, clean, renewable, and economical generation.

Geothermal power plants can operate 24 hours per day, providing base-load capacity, and the world potential capacity for geothermal power generation is estimated at 85 GW over the next 30 years. However, geothermal power is accessible only in limited areas of the world, including the United States, Central America, East Africa, Iceland, Indonesia, and the Philippines. The costs of geothermal energy have dropped substantially from the systems built in the 1970s.[7] Geothermal heat generation can be competitive in many countries producing geothermal power, or in other regions where the resource is of a lower temperature. Enhanced geothermal system (EGS) technology does not require natural convective hydrothermal resources, so it can be used in areas that were previously unsuitable for geothermal power, if the resource is very large. EGS is currently under research at the U.S. Department of Energy.

Biomass briquettes are increasingly being used in the developing world as an alternative to charcoal. The technique involves the conversion of almost any plant matter into compressed briquettes that typically have about 70% the calorific value of charcoal. There are relatively few examples of large scale briquette production. One exception is in North Kivu, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where forest clearance for charcoal production is considered to be the biggest threat to Mountain Gorilla habitat. The staff of Virunga National Park have successfully trained and equipped over 3500 people to produce biomass briquettes, thereby replacing charcoal produced illegally inside the national park, and creating significant employment for people living in extreme poverty in conflict affected areas.[11]

Second-generation technologies

Markets for second-generation technologies are strong and growing, but only in a few countries. The challenge is to broaden the market base for continued growth worldwide. Strategic deployment in one country not only reduces technology costs for users there, but also for those in other countries, contributing to overall cost reductions and performance improvement.

— International Energy Agency, RENEWABLES IN GLOBAL ENERGY SUPPLY, An IEA Fact Sheet[7]

Solar heating systems are a well known second-generation technology and generally consist of solar thermal collectors, a fluid system to move the heat from the collector to its point of usage, and a reservoir or tank for heat storage and subsequent use. The systems may be used to heat domestic hot water, swimming pool water, or for space heating.[13] The heat can also be used for industrial applications or as an energy input for other uses such as cooling equipment.[14] In many climates, a solar heating system can provide a very high percentage (50 to 75%) of domestic hot water energy. Energy received from the sun by the earth is that of electromagnetic radiation. Light ranges of visible, infrared, ultraviolet, x-rays, and radio waves received by the earth through solar energy. The highest power of radiation comes from visible light. Solar power is complicated due to changes in seasons and from day to night. Cloud cover can also add to complications of solar energy, and not all radiation from the sun reaches earth because it is absorbed and dispersed due to clouds and gases within the earth's atmospheres.[15]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, most photovoltaic modules provided remote-area power supply, but from around 1995, industry efforts have focused increasingly on developing building integrated photovoltaics and power plants for grid connected applications (see photovoltaic power stations article for details). Currently the largest photovoltaic power plant in North America is the Nellis Solar Power Plant (15 MW).[16][17] There is a proposal to build a Solar power station in Victoria, Australia, which would be the world's largest PV power station, at 154 MW.[18][19] Other large photovoltaic power stations include the Girassol solar power plant (62 MW),[20] and the Waldpolenz Solar Park (40 MW).[21]

Some of the second-generation renewables, such as wind power, have high potential and have already realised relatively low production costs. At the end of 2008, worldwide wind farm capacity was 120,791 megawatts (MW), representing an increase of 28.8 percent during the year,[22] and wind power produced some 1.3% of global electricity consumption.[23] Wind power accounts for approximately 20% of electricity use in Denmark, 9% in Spain, and 7% in Germany.[24][25] However, it may be difficult to site wind turbines in some areas for aesthetic or environmental reasons, and it may be difficult to integrate wind power into electricity grids in some cases.[7]

Solar thermal power stations have been successfully operating in California commercially since the late 1980s, including the largest solar power plant of any kind, the 350 MW Solar Energy Generating Systems. Nevada Solar One is another 64MW plant which has recently opened.[26] Other parabolic trough power plants being proposed are two 50MW plants in Spain, and a 100MW plant in Israel.[27]

Brazil has one of the largest renewable energy programs in the world, involving production of ethanol fuel from sugar cane, and ethanol now provides 18 percent of the country's automotive fuel. As a result of this, together with the exploitation of domestic deep water oil sources, Brazil, which years ago had to import a large share of the petroleum needed for domestic consumption, recently reached complete self-sufficiency in oil.[28][29][30]

Most cars on the road today in the U.S. can run on blends of up to 10% ethanol, and motor vehicle manufacturers already produce vehicles designed to run on much higher ethanol blends. Ford, DaimlerChrysler, and GM are among the automobile companies that sell “flexible-fuel” cars, trucks, and minivans that can use gasoline and ethanol blends ranging from pure gasoline up to 85% ethanol (E85). By mid-2006, there were approximately six million E85-compatible vehicles on U.S. roads.[31]

Third-generation technologies

Third-generation technologies are not yet widely demonstrated or commercialised. They are on the horizon and may have potential comparable to other renewable energy technologies, but still depend on attracting sufficient attention and RD&D funding. These newest technologies include advanced biomass gasification, biorefinery technologies, solar thermal power stations, hot dry rock geothermal energy, and ocean energy.

— International Energy Agency, RENEWABLES IN GLOBAL ENERGY SUPPLY, An IEA Fact Sheet[7]

Bio-fuels may be defined as "renewable," yet may not be "sustainable," due to soil degradation. As of 2012, 40% of Americas corn production goes toward ethanol. Ethanol takes up a large percentage of "Clean Energy Use" when in fact, it is still debatable whether ethanol should be considered as a "Clean Energy."[3]

According to the International Energy Agency, new bioenergy (biofuel) technologies being developed today, notably cellulosic ethanol biorefineries, could allow biofuels to play a much bigger role in the future than previously thought.[32] Cellulosic ethanol can be made from plant matter composed primarily of inedible cellulose fibers that form the stems and branches of most plants. Crop residues (such as corn stalks, wheat straw and rice straw), wood waste, and municipal solid waste are potential sources of cellulosic biomass. Dedicated energy crops, such as switchgrass, are also promising cellulose sources that can be sustainably produced in many regions of the United States.[33]

In terms of Ocean energy, another third-generation technology, Portugal has the world's first commercial wave farm, the Aguçadora Wave Park, under construction in 2007. The farm will initially use three Pelamis P-750 machines generating 2.25 MW.[35][36] and costs are put at 8.5 million euro. Subject to successful operation, a further 70 million euro is likely to be invested before 2009 on a further 28 machines to generate 525 MW.[37] Funding for a wave farm in Scotland was announced in February, 2007 by the Scottish Executive, at a cost of over 4 million pounds, as part of a £13 million funding packages for ocean power in Scotland. The farm will be the world's largest with a capacity of 3 MW generated by four Pelamis machines.[38] (see also Wave farm).

In 2007, the world's first turbine to create commercial amounts of energy using tidal power was installed in the narrows of Strangford Lough in Ireland. The 1.2 MW underwater tidal electricity generator takes advantage of the fast tidal flow in the lough which can be up to 4m/s. Although the generator is powerful enough to power up to a thousand homes, the turbine has a minimal environmental impact, as it is almost entirely submerged, and the rotors turn slowly enough that they pose no danger to wildlife.[39][40]

Solar power panels that use nanotechnology, which can create circuits out of individual silicon molecules, may cost half as much as traditional photovoltaic cells, according to executives and investors involved in developing the products. Nanosolar has secured more than $100 million from investors to build a factory for nanotechnology thin-film solar panels. The company's plant has a planned production capacity of 430 megawatts peak power of solar cells per year. Commercial production started and first panels have been shipped[41] to customers in late 2007.[42] Large national and regional research projects on artificial photosynthesis are designing nanotechnology-based systems that use solar energy to split water into hydrogen fuel.[43] In 2011, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed what they are calling an "Artificial Leaf", which is capable of splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen directly from solar power when dropped into a glass of water. One side of the "Artificial Leaf" produces bubbles of hydrogen, while the other side produces bubbles of oxygen.[44]

Most current solar power plants are made from an array of similar units where each unit is continuously adjusted, e.g., with some step motors, so that the light converter stays in focus of the sun light. The cost of focusing light on converters such as high-power solar panels, Stirling engine, etc. can be dramatically decreased with a simple and efficient rope mechanics.[45] In this technique many units are connected with a network of ropes so that pulling two or three ropes is sufficient to keep all light converters simultaneously in focus as the direction of the sun changes.

Energy efficiency

Moving towards energy sustainability will require changes not only in the way energy is supplied, but in the way it is used, and reducing the amount of energy required to deliver various goods or services is essential. Opportunities for improvement on the demand side of the energy equation are as rich and diverse as those on the supply side, and often offer significant economic benefits.[46]

Renewable energy and energy efficiency are sometimes said to be the “twin pillars” of sustainable energy policy. Both resources must be developed in order to stabilize and reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Efficiency slows down energy demand growth so that rising clean energy supplies can make deep cuts in fossil fuel use. If energy use grows too fast, renewable energy development will chase a receding target. Likewise, unless clean energy supplies come online rapidly, slowing demand growth will only begin to reduce total emissions; reducing the carbon content of energy sources is also needed. Any serious vision of a sustainable energy economy thus requires commitments to both renewables and efficiency.[47]

Renewable energy (and energy efficiency) are no longer niche sectors that are promoted only by governments and environmentalists. The increased levels of investment and the fact that much of the capital is coming from more conventional financial actors suggest that sustainable energy options are now becoming mainstream.[48] An example of this would be The Alliance to Save Energy's Project with Stahl Consolidated Manufacturing, (Huntsville, Alabama, USA) (StahlCon 7), a patented generator shaft designed to reduce emissions within existing power generating systems, granted publishing rights to the Alliance in 2007.

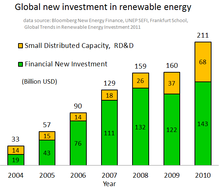

Climate change concerns coupled with high oil prices and increasing government support are driving increasing rates of investment in the sustainable energy industries, according to a trend analysis from the United Nations Environment Programme. According to UNEP, global investment in sustainable energy in 2007 was higher than previous levels, with $148 billion of new money raised in 2007, an increase of 60% over 2006. Total financial transactions in sustainable energy, including acquisition activity, was $204 billion.[49]

Investment flows in 2007 broadened and diversified, making the overall picture one of greater breadth and depth of sustainable energy use. The mainstream capital markets are "now fully receptive to sustainable energy companies, supported by a surge in funds destined for clean energy investment".[49]

Green energy

Green energy includes natural energetic processes that can be harnessed with little pollution. Anaerobic digestion, geothermal power, wind power, small-scale hydropower, solar energy, biomass power, tidal power, wave power, and some forms of nuclear power (ones which are able to "burn" nuclear waste through a process known as nuclear transmutation, e.g. an Integral Fast Reactor), and therefore belong in the "Green Energy" category). Some definitions may also include power derived from the incineration of waste.

Some people, including George Monbiot[50] and James Lovelock[51] have specifically classified nuclear power as green energy. Others, including Greenpeace[52][53] disagree, claiming that the problems associated with radioactive waste and the risk of nuclear accidents (such as the Chernobyl disaster) pose an unacceptable risk to the environment and to humanity. However, newer nuclear reactor designs are capable of utilizing what is now deemed "nuclear waste" until it is no longer (or dramatically less) dangerous, and have design features that greatly minimize the possibility of a nuclear accident. (See: Integral Fast Reactor)

No power source is entirely impact-free. All energy sources require energy and give rise to some degree of pollution from manufacture of the technology. Some have argued that although green energy is a commendable effort in solving the world's increasing energy consumption, it must be accompanied by a cultural change, namely one that encourages the decrease of the world's appetite for energy, if it is to have the impact the world so eagerly anticipates.[54]

In several countries with common carrier arrangements, electricity retailing arrangements make it possible for consumers to purchase green electricity (renewable electricity) from either their utility or a green power provider.

When energy is purchased from the electricity network, the power reaching the consumer will not necessarily be generated from green energy sources. The local utility company, electric company, or state power pool buys their electricity from electricity producers who may be generating from fossil fuel, nuclear or renewable energy sources. In many countries green energy currently provides a very small amount of electricity, generally contributing less than 2 to 5% to the overall pool. In some U.S. states, local governments have formed regional power purchasing pools using Community Choice Aggregation and Solar Bonds to achieve a 51% renewable mix or higher, such as in the City of San Francisco.[55]

By participating in a green energy program a consumer may be having an effect on the energy sources used and ultimately might be helping to promote and expand the use of green energy. They are also making a statement to policy makers that they are willing to pay a price premium to support renewable energy. Green energy consumers either obligate the utility companies to increase the amount of green energy that they purchase from the pool (so decreasing the amount of non-green energy they purchase), or directly fund the green energy through a green power provider. If insufficient green energy sources are available, the utility must develop new ones or contract with a third party energy supplier to provide green energy, causing more to be built. However, there is no way the consumer can check whether or not the electricity bought is "green" or otherwise.

In some countries such as the Netherlands, electricity companies guarantee to buy an equal amount of 'green power' as is being used by their green power customers. The Dutch government exempts green power from pollution taxes, which means green power is hardly any more expensive than other power.

In the United States, one of the main problems with purchasing green energy through the electrical grid is the current centralized infrastructure that supplies the consumer’s electricity. This infrastructure has led to increasingly frequent brown outs and black outs, high CO2 emissions, higher energy costs, and power quality issues.[56] An additional $450 billion will be invested to expand this fledgling system over the next 20 years to meet increasing demand.[57] In addition, this centralized system is now being further overtaxed with the incorporation of renewable energies such as wind, solar, and geothermal energies. Renewable resources, due to the amount of space they require, are often located in remote areas where there is a lower energy demand. The current infrastructure would make transporting this energy to high demand areas, such as urban centers, highly inefficient and in some cases impossible. In addition, despite the amount of renewable energy produced or the economic viability of such technologies only about 20 percent will be able to be incorporated into the grid. To have a more sustainable energy profile, the United States must move towards implementing changes to the electrical grid that will accommodate a mixed-fuel economy.[58]

However, several initiatives are being proposed to mitigate these distribution problems. First and foremost, the most effective way to reduce USA’s CO2 emissions and slow global warming is through conservation efforts. Opponents of the current US electrical grid have also advocated for decentralizing the grid. This system would increase efficiency by reducing the amount of energy lost in transmission. It would also be economically viable as it would reduce the amount of power lines that will need to be constructed in the future to keep up with demand. Merging heat and power in this system would create added benefits and help to increase its efficiency by up to 80-90%. This is a significant increase from the current fossil fuel plants which only have an efficiency of 34%.[59]

A more recent concept for improving our electrical grid is to beam microwaves from Earth-orbiting satellites or the moon to directly when and where there is demand. The power would be generated from solar energy captured on the lunar surface In this system, the receivers would be “broad, translucent tent-like structures that would receive microwaves and convert them to electricity”. NASA said in 2000 that the technology was worth pursuing but it is still too soon to say if the technology will be cost-effective.[60]

The World Wide Fund for Nature and several green electricity labelling organizations have created the Eugene Green Energy Standard under which the national green electricity certification schemes can be accredited to ensure that the purchase of green energy leads to the provision of additional new green energy resources.[61]

Local green energy systems

Those not satisfied with the third-party grid approach to green energy via the power grid can install their own locally based renewable energy system. Renewable energy electrical systems from solar to wind to even local hydro-power in some cases, are some of the many types of renewable energy systems available locally. Additionally, for those interested in heating and cooling their dwelling via renewable energy, geothermal heat pump systems that tap the constant temperature of the earth, which is around 7 to 15 degrees Celsius a few feet underground and increases dramatically at greater depths, are an option over conventional natural gas and petroleum-fueled heat approaches. Also, in geographic locations where the Earth's Crust is especially thin, or near volcanoes (as is the case in Iceland) there exists the potential to generate even more electricity than would be possible at other sites, thanks to a more significant temperature gradient at these locales.

The advantage of this approach in the United States is that many states offer incentives to offset the cost of installation of a renewable energy system. In California, Massachusetts and several other U.S. states, a new approach to community energy supply called Community Choice Aggregation has provided communities with the means to solicit a competitive electricity supplier and use municipal revenue bonds to finance development of local green energy resources. Individuals are usually assured that the electricity they are using is actually produced from a green energy source that they control. Once the system is paid for, the owner of a renewable energy system will be producing their own renewable electricity for essentially no cost and can sell the excess to the local utility at a profit.

Using green energy

Renewable energy, after its generation, needs to be stored in a medium for use with autonomous devices as well as vehicles. Also, to provide household electricity in remote areas (that is areas which are not connected to the mains electricity grid), energy storage is required for use with renewable energy. Energy generation and consumption systems used in the latter case are usually stand-alone power systems.

Some examples are:

- energy carriers as hydrogen, liquid nitrogen, compressed air, oxyhydrogen, batteries, to power vehicles.

- flywheel energy storage, pumped-storage hydroelectricity is more usable in stationary applications (e.g. to power homes and offices. In household power systems, conversion of energy can also be done to reduce smell. For example organic matter such as cow dung and spoilable organic matter can be converted to biochar. To eliminate emissions, carbon capture and storage is then used.

Usually however, renewable energy is derived from the mains electricity grid. This means that energy storage is mostly not used, as the mains electricity grid is organised to produce the exact amount of energy being consumed at that particular moment. Energy production on the mains electricity grid is always set up as a combination of (large-scale) renewable energy plants, as well as other power plants as fossil-fuel power plants and nuclear power. This combination however, which is essential for this type of energy supply (as e.g. wind turbines, solar power plants etc.) can only produce when the wind blows and the sun shines. This is also one of the main drawbacks of the system as fossil fuel powerplants are polluting and are a main cause of global warming (nuclear power being an exception). Although fossil fuel power plants too can made emissionless (through carbon capture and storage), as well as renewable (if the plants are converted to e.g. biomass) the best solution is still to phase out the latter power plants over time. Nuclear power plants too can be more or less eliminated from their problem of nuclear waste through the use of nuclear reprocessing and newer plants as fast breeder and nuclear fusion plants.

Renewable energy power plants do provide a steady flow of energy. For example hydropower plants, ocean thermal plants, osmotic power plants all provide power at a regulated pace, and are thus available power sources at any given moment (even at night, windstill moments etc.). At present however, the number of steady-flow renewable energy plants alone is still too small to meet energy demands at the times of the day when the irregular producing renewable energy plants cannot produce power.

Besides the greening of fossil fuel and nuclear power plants, another option is the distribution and immediate use of power from solely renewable sources. In this set-up energy storage is again not necessary. For example, TREC has proposed to distribute solar power from the Sahara to Europe. Europe can distribute wind and ocean power to the Sahara and other countries. In this way, power is produced at any given time as at any point of the planet as the sun or the wind is up or ocean waves and currents are stirring. This option however is probably not possible in the short-term, as fossil fuel and nuclear power are still the main sources of energy on the mains electricity net and replacing them will not be possible overnight.

Several large-scale energy storage suggestions for the grid have been done. This improves efficiency and decreases energy losses but a conversion to an energy storing mains electricity grid is a very costly solution. Some costs could potentially be reduced by making use of energy storage equipment the consumer buys and not the state. An example is car batteries in personal vehicles that would double as an energy buffer for the electricity grid. However besides the cost, setting-up such a system would still be a very complicated and difficult procedure. Also, energy storage apparatus' as car batteries are also built with materials that pose a threat to the environment (e.g. sulphuric acid). The combined production of batteries for such a large part of the population would thus still not quite environmental. Besides car batteries however, other large-scale energy storage suggestions for the grid have been done which make use of less polluting energy carriers (e.g. compressed air tanks and flywheel energy storage).

Low-energy house

A low-energy house is any type of house that from design, technologies and building products uses less energy, from any source, than a traditional or average contemporary house. In the practice of sustainable design, sustainable architecture, low-energy building, energy-efficient landscaping low-energy houses often use active solar and passive solar building design techniques and components to reduce their energy expenditure.

- General usage

The meaning of the term 'low-energy house' has changed over time, but in Europe it generally refers to a house that uses around half of the German or Swiss low-energy standards referred to below for space heating, typically in the range from 30 kWh/m²a to 20 kWh/m²a (9,500 Btu/ft²/yr to 6,300 Btu/ft²/yr). Below this the term 'Ultra-low-energy building' is often used.

The term can also refer to any dwelling whose energy use is below the standards demanded by current building codes. Because national standards vary considerably around the world, 'low-energy' developments in one country may not meet 'normal practice' in another.

Carbon neutral and negative fuels

A carbon neutral fuel is a synthetic fuel — such as methane, gasoline, diesel fuel or jet fuel — produced from renewable or nuclear energy used to hydrogenate waste carbon dioxide recycled from power plant flue-gas emissions, recovered from automotive exhaust gas, or derived from carbonic acid in seawater.[62][63][64][65][66] Such fuels are carbon neutral because they do not result in a net increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases.[67][68] To the extent that carbon neutral fuels displace fossil fuels, or if they are produced from waste carbon or seawater carbonic acid, and their combustion is subject to carbon capture at the flue or exhaust pipe, they result in negative carbon dioxide emission and net carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere, and thus constitute a form of greenhouse gas remediation.[69][70][71] Such fuels are produced by the electrolysis of water to make hydrogen used in turn in the Sabatier reaction to produce methane which may then be stored to be burned later in power plants as synthetic natural gas, transported by pipeline, truck, or tanker ship, or be used in gas to liquids processes such as the Fischer–Tropsch process to make traditional transportation or heating fuels.[72][73][74]

Carbon neutral fuels can provide easily distributed storage for renewable energy, eliminating the problems of wind and solar intermittency, and enabling transmission of wind, water, and solar power through existing natural gas pipelines. Such renewable fuels alleviate the costs and dependency issues of imported fossil fuels without requiring either electrification of the vehicle fleet or conversion to hydrogen or other fuels, enabling continued compatible and affordable vehicles.[72] Germany has built a 250 kilowatt synthetic methane plant which they are scaling up to 10 megawatts.[75][76][77] Commercial developments are taking place in Columbia, South Carolina,[78] Camarillo, California,[79] and Darlington, England.[80]

The least expensive source of carbon for recycling into fuel is flue-gas emissions from fossil-fuel combustion where it can be extracted for about USD $7.50 per ton.[64][68][73] Automobile exhaust gas capture has also been shown to be economical in theory, but would require extensive design changes or retrofitting.[65] The carbonic acid in seawater is in chemical equilibrium with atmospheric carbon dioxide. The United States Navy has done extensive work studying and scaling up the extraction of carbon from seawater.[81][82] Work at the Palo Alto Research Center has improved substantially on the Navy processes, resulting in carbon extraction from seawater for about $50 per ton.[66] Carbon capture from ambient air is very much more costly, at between $600 and $1000 per ton. At present that is considered an impractical cost for fuel synthesis or carbon sequestration.[68][69]

Nighttime wind power is considered the most economical form of electrical power with which to synthesize fuel, because the load curve for electricity peaks sharply during the warmest hours of the day, but wind tends to blow slightly more at night than during the day. Therefore, the price of nighttime wind power is often much less expensive than any alternative. Off-peak wind power prices in high wind penetration areas of the U.S. averaged 1.64 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2009, and only 0.71 cents/kWh during the least expensive six hours of the day.[72] Typically, wholesale electricity costs 2 to 5 cents/kWh during the day.[83] Commercial fuel synthesis companies suggest they can produce fuel for less than petroleum fuels when oil costs more than $55 per barrel.[84] The US Navy estimates that shipboard production of jet fuel from nuclear power would cost about $6 per gallon. While that was about twice the petroleum fuel cost in 2010, it is expected to be much less than the market price in less than five years if recent trends continue. Moreover, since the delivery of fuel to a carrier battle group costs about $8 per gallon, shipboard production is already much less expensive.[85] The Navy's estimate that 100 megawatts can produce 41,000 gallons of fuel per day indicates that terrestrial production from wind power would cost less than $1 per gallon.[86]

Green energy and labelling by region

European Union

Directive 2004/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 on the promotion of cogeneration based on a useful heat demand in the internal energy market[87] includes the article 5 (Guarantee of origin of electricity from high-efficiency cogeneration).

Finnish electricity markets are among the most liberal of the world. Markets were partially opened for big electricity users in 1995 and for all users in 1997.[88] In 1998 the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation launched an ecolabel for electricity. The ecolabel is called EKOenergy. 10 out of 70 Finnish electricity retailers have managed to fulfill the criteria of eko energy. Almost 4% of the electricity in Finland was sold under the label in 2008. End users buying EKOenergy influence in profitability of different electricity production plants.[89] In 2009 25.7% of all the energy consumed in Finland was from renewable energy sources.[90] Only part of electricity produced by renewables fulfills the EKOenergy criteria.

A Green Energy Supply Certification Scheme was launched in the United Kingdom in February 2010. This implements guidelines from the Energy Regulator, Ofgem, and sets requirements on transparency, the matching of sales by renewable energy supplies, and additionality.[91]

United States

The United States Department of Energy (DOE), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Center for Resource Solutions (CRS)[92] recognizes the voluntary purchase of electricity from renewable energy sources (also called renewable electricity or green electricity) as green power.[93]

The most popular way to purchase renewable energy as revealed by NREL data is through purchasing Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs). According to a Natural Marketing Institute (NMI)[94] survey 55 percent of American consumers want companies to increase their use of renewable energy.[93]

DOE selected six companies for its 2007 Green Power Supplier Awards, including Constellation NewEnergy; 3Degrees; Sterling Planet; SunEdison; Pacific Power and Rocky Mountain Power; and Silicon Valley Power. The combined green power provided by those six winners equals more than 5 billion kilowatt-hours per year, which is enough to power nearly 465,000 average U.S. households.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Green Power Partnership is a voluntary program that supports the organizational procurement of renewable electricity by offering expert advice, technical support, tools and resources. This can help organizations lower the transaction costs of buying renewable power, reduce carbon footprint, and communicate its leadership to key stakeholders.[95]

Throughout the country, more than half of all U.S. electricity customers now have an option to purchase some type of green power product from a retail electricity provider. Roughly one-quarter of the nation's utilities offer green power programs to customers, and voluntary retail sales of renewable energy in the United States totaled more than 12 billion kilowatt-hours in 2006, a 40% increase over the previous year.

China

Renewable energy is helping the People's Republic of China complete its economic transformation and achieve "energy security". China has moved rapidly along the path of renewable energy development.[96] About 17 percent of China's electricity came from renewable sources in 2007, led by the world's largest number of hydroelectric generators.[97] China had a total installed capacity of hydropower of 197 GW in 2009.[98] Technology development and increased amounts of investment in renewable energy technologies and installations have increased markedly throughout the 2000s in China, and investment in renewables is now part of China's economic stimulus strategy.[99] Researchers from Harvard University and Tsinghua University have found that the People's Republic could meet all of its electricity demands from wind power by 2030.[100] Despite this, Wen Jiabao stated in a March 5th, 2012 report that China will end the "blind expansion" into wind and solar energy, instead developing nuclear power, hydropower, and shale gas.[101]

According to China's "Energy Blue Paper" recently written by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the average rate of recovery of coal from mining in China is only 30%, less than one-half the rate of recovery throughout the world; the rate of recovery of coal resources in the U.S., Australia, Germany and Canada is ~80%. The rate of recovery of coal from mining in Shanxi Province, China’s largest source of coal is approximately 40%, though the rate of recovery of village and township coal mines in Shanxi Province is only 10%-20%. Cumulatively over the course of the past 20 years (1980–2000) China has wasted upwards of 28 gigatons of coal.[102] The same causes for a low rate of recovery in coal mining - that extraction methods are backwards - lead to safety problems in China’s coal mining sector. Another reason for the low rate of recovery is that the majority of extraction comes from small-scale mining; of the 346.9 gigatons of coal extracted by China, only 98 gigatons has come from large or mid-sized mines while 250 gigatons are extracted from small mines. Based on coal production in 2005 of 2.19 gigatons and a current rate of recovery of 30%, if China were able to double its rate of recovery it would save approximately 3.5 gigatons of coal.[103]

Canada

Canada, one of the world’s few net exporters of energy, has a vast and exceptionally diversified mix of renewable-energy resources, including hydro, solar, wind, biomass and tidal power.

The development of clean technologies is a priority for all levels of government in Canada, at the federal, provincial, territorial and regional levels. Indeed, many support the emergence of a bio-economy with targeted policies and incentives that range from tax credits and education programs to market-stimulating regulations.

- Canada has the third-largest renewable energy capacity in the world; renewable sources generate 17 percent of its total primary energy supply and more than 60 percent of its total electricity capacity.

- Canada is the sixth-largest consumer of electricity in the world. The US, the world’s largest electricity consumer, is Canada’s primary trading partner.

- Between 2003 and 2011, 126 foreign companies established greenfield projects in Canada’s renewable energy sector.

- The Government of Canada has set a goal of generating 90 percent of Canada’s electricity from zero-emitting sources by 2020. Canadian provinces also offer generous incentives, and the feed-in-tariff rates for solar PV electricity offered in Ontario are among the world’s most attractive.[104]

Sustainable energy research

There are numerous organizations within the academic, federal, and commercial sectors conducting large scale advanced research in the field of sustainable energy. This research spans several areas of focus across the sustainable energy spectrum. Most of the research is targeted at improving efficiency and increasing overall energy yields.[105] Multiple federally supported research organizations have focused on sustainable energy in recent years. Two of the most prominent of these labs are Sandia National Laboratories and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), both of which are funded by the United States Department of Energy and supported by various corporate partners.[106] Sandia has a total budget of $2.4 billion [107] while NREL has a budget of $375 million.[108]

Solar

The primary obstacle that is preventing the large scale implementation of solar powered energy generation is the inefficiency of current solar technology. Currently, photovoltaic (PV) panels only have the ability to convert around 16% of the sunlight that hits them into electricity.[109] At this rate, many experts believe that solar energy is not efficient enough to be economically sustainable given the cost to produce the panels themselves. Both Sandia National Laboratories and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), have heavily funded solar research programs. The NREL solar program has a budget of around $75 million [110] and develops research projects in the areas of photovoltaic (PV) technology, solar thermal energy, and solar radiation.[111] The budget for Sandia’s solar division is unknown, however it accounts for a significant percentage of the laboratory’s $2.4 billion budget.[112] Several academic programs have focused on solar research in recent years. The Solar Energy Research Center (SERC) at University of North Carolina (UNC) has the sole purpose of developing cost effective solar technology. In 2008, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a method to store solar energy by using it to produce hydrogen fuel from water.[113] Such research is targeted at addressing the obstacle that solar development faces of storing energy for use during nighttime hours when the sun is not shining. In February 2012, North Carolina-based Semprius Inc., a solar development company backed by German corporation Siemens, announced that they had developed the world’s most efficient solar panel. The company claims that the prototype converts 33.9% of the sunlight that hits it to electricity, more than double the previous high-end conversion rate.[114]

Wind

Wind energy research dates back several decades to the 1970s when NASA developed an analytical model to predict wind turbine power generation during high winds.[116] Today, both Sandia National Laboratories and National Renewable Energy Laboratory have programs dedicated to wind research. Sandia’s laboratory focuses on the advancement of materials, aerodynamics, and sensors.[117] The NREL wind projects are centered on improving wind plant power production, reducing their capital costs, and making wind energy more cost effective overall.[118] The Field Laboratory for Optimized Wind Energy (FLOWE) at CalTech was established to research renewable approaches to wind energy farming technology practices that have the potential to reduce the cost, size, and environmental impact of wind energy production.[119]

A wind farm is a group of wind turbines in the same location used to produce electric power. A large wind farm may consist of several hundred individual wind turbines, and cover an extended area of hundreds of square miles, but the land between the turbines may be used for agricultural or other purposes. A wind farm may also be located offshore.

Many of the largest operational onshore wind farms are located in the USA and China. The Gansu Wind Farm in China has over 5,000 MW installed with a goal of 20,000 MW by 2020. China has several other "wind power bases" of similar size. The Alta Wind Energy Center in California is the largest onshore wind farm outside of China, with a capacity of 1020 MW of power.[120] As of February 2012, the Walney Wind Farm in United Kingdom is the largest offshore wind farm in the world at 367 MW, followed by Thanet Offshore Wind Project (300 MW), also in the UK.

There are many large wind farms under construction and these include Anholt Offshore Wind Farm (400 MW), BARD Offshore 1 (400 MW), Clyde Wind Farm (350 MW), Greater Gabbard wind farm (500 MW), Lincs Wind Farm (270 MW), London Array (1000 MW), Lower Snake River Wind Project (343 MW), Macarthur Wind Farm (420 MW), Shepherds Flat Wind Farm (845 MW), and Sheringham Shoal (317 MW).

Ethanol biofuels

As the primary source of biofuels in North America, many organizations are conducting research in the area of ethanol production. On the Federal level, the USDA conducts a large amount of research regarding ethanol production in the United States. Much of this research is targeted towards the effect of ethanol production on domestic food markets.[121] The National Renewable Energy Laboratory has conducted various ethanol research projects, mainly in the area of cellulosic ethanol.[122] Cellulosic ethanol has many benefits over traditional corn based-ethanol. It does not take away or directly conflict with the food supply because it is produced from wood, grasses, or non-edible parts of plants.[123] Moreover, some studies have shown cellulosic ethanol to be more cost effective and economically sustainable than corn-based ethanol.[124] Sandia National Laboratories conducts in-house cellulosic ethanol research [125] and is also a member of the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), a research institute founded by the United States Department of Energy with the goal of developing cellulosic biofuels.[126]

Other Biofuels

From 1978 to 1996, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory experimented with using algae as a biofuels source in the "Aquatic Species Program.”[127] A self-published article by Michael Briggs, at the University of New Hampshire Biofuels Group, offers estimates for the realistic replacement of all motor vehicle fuel with biofuels by utilizing algae that have a natural oil content greater than 50%, which Briggs suggests can be grown on algae ponds at wastewater treatment plants.[128] This oil-rich algae can then be extracted from the system and processed into biofuels, with the dried remainder further reprocessed to create ethanol. The production of algae to harvest oil for biofuels has not yet been undertaken on a commercial scale, but feasibility studies have been conducted to arrive at the above yield estimate. In addition to its projected high yield, algaculture— unlike food crop-based biofuels — does not entail a decrease in food production, since it requires neither farmland nor fresh water. Many companies are pursuing algae bio-reactors for various purposes, including scaling up biofuels production to commercial levels.[129][130] Several groups in various sectors are conducting research on Jatropha curcas, a poisonous shrub-like tree that produces seeds considered by many to be a viable source of biofuels feedstock oil.[131] Much of this research focuses on improving the overall per acre oil yield of Jatropha through advancements in genetics, soil science, and horticultural practices. SG Biofuels, a San Diego-based Jatropha developer, has used molecular breeding and biotechnology to produce elite hybrid seeds of Jatropha that show significant yield improvements over first generation varieties.[132] The Center for Sustainable Energy Farming (CfSEF) is a Los Angeles-based non-profit research organization dedicated to Jatropha research in the areas of plant science, agronomy, and horticulture. Successful exploration of these disciplines is projected to increase Jatropha farm production yields by 200-300% in the next ten years.[133]

Geothermal

Geothermal energy is produced by tapping into the thermal energy created and stored within the earth. It is considered sustainable because that thermal energy is constantly replenished.[134] However, the science of geothermal energy generation is still young and developing economic viability. Several entities, such as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory [135] and Sandia National Laboratories [136] are conducting research toward the goal of establishing a proven science around geothermal energy. The International Centre for Geothermal Research (IGC), a German geosciences research organization, is largely focused on geothermal energy development research.[137]

Hydrogen

Over $1 billion of federal money has been spent on the research and development of hydrogen fuel in the United States.[138] Both the National Renewable Energy Laboratory [139] and Sandia National Laboratories [140] have departments dedicated to hydrogen research. Hydrogen is useful for energy storage and for use in airplanes, but is not practical for automobile use, as it is not very efficient, compared to using a battery - for the same cost you can go three times as far using a battery.[141]

Clean energy investments

Renewable energy commercialization

| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

Renewable energy commercialization involves the deployment of three generations of renewable energy technologies dating back more than 100 years. First-generation technologies, which are already mature and economically competitive, include biomass, hydroelectricity, geothermal power and heat. Second-generation technologies are market-ready and are being deployed at the present time; they include solar heating, photovoltaics, wind power, solar thermal power stations, and modern forms of bioenergy. Third-generation technologies require continued R&D efforts in order to make large contributions on a global scale and include advanced biomass gasification, biorefinery technologies, hot-dry-rock geothermal power, and ocean energy.[7]

Total investment in renewable energy reached $257 billion in 2011, up from $211 billion in 2010. The top countries for investment in 2011 were China, Germany, the United States, Italy, and Brazil.[143][144] Continued growth for the renewable energy sector and promotional policies helped the industry weather the 2009 economic crisis better than many other sectors.[145] U.S. President Barack Obama's American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 included more than $70 billion in direct spending and tax credits for clean energy and associated transportation programs. Clean Edge suggests that the commercialization of clean energy has helped countries around the world pull out of the 2009 global financial crisis.[145]

There are some non-technical barriers to the widespread use of renewables,[146][147] and it is often public policy and political leadership that helps to address these barriers and drive the wider acceptance of renewable energy technologies.[148] As of 2011, 118 countries have targets for their own renewable energy futures, and have enacted wide-ranging public policies to promote renewables.[149][150] Climate change concerns[147][151][152] are driving increasing growth in the renewable energy industries.[153][154][155] Leading renewable energy companies include First Solar, Gamesa, GE Energy, Yingli, Sharp Solar, Siemens, Trina Solar, Suntech, and Vestas.[156][157]

Economic analysts expect market gains for renewable energy (and efficient energy use) following the 2011 Japanese nuclear accidents.[158][159] In his 2012 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama restated his commitment to renewable energy and mentioned the long-standing Interior Department commitment to permit 10,000 MW of renewable energy projects on public land in 2012.[160] Globally, there are an estimated 3 million direct jobs in renewable energy industries, with about half of them in the biofuels industry.[161] According to a 2011 projection by the International Energy Agency, solar power generators may produce most of the world’s electricity within 50 years, dramatically reducing harmful greenhouse gas emissions.[162]

Limits of government support for renewable energy investments

Research conducted by the World Pensions Council (WPC) suggests that the failure of Solyndra in August 2011 should be viewed within the broader context of unsustainable government spending on sustainable energy, and that the Solyndra bankruptcy was a harbinger of the collapse of the German solar cell industry in the first quarter of 2012- both events being "stark reminders of the risks that go with disproportionate levels of leveraging and the reliance on unsustainable government subsidies and unreasonable fiscal incentives to 'stimulate' demand. In many ways, real estate and solar energy assets were de facto owned by 'unnatural owners' such as banks, and, when the banks collapsed, by Western governments unable or unwilling to provide fresh capital" in a context of fiscal austerity and tighter credit limits.[163]

Clean energy investments in China

According to a recently released United Nations report, global investment in renewable energy reached a record $257 billion in 2011, a 17 percent increase from the amount invested in 2010. Globally, renewable energy covers approximately 16.7 percent of energy consumption. Of this share, modern technologies such as solar and wind accounted for just 8.2 percent, even less than the 8.5 percent contributed by biomass. By comparison, more than 80 percent of electricity consumed worldwide still comes from fossil fuels.

China was responsible for almost one-fifth of total global investment, spending $52 billion on renewable energy last year. The United States was close behind with investments of $51 billion, as developers sought to benefit from government incentive programs before they expired. Germany, Italy and India rounded out the list of the top five countries.

According to China’s 12th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (2011-2015), the country will spend $473.1 billion on clean energy investments over the next five years. China’s goal is to have 20 percent of its total energy demand sourced from renewable energy by 2020.

In 2011, solar led the way as far as global investment in renewable energy, with investment surging to $147 billion, a year-on-year increase of 52 percent, due to strong demand for rooftop photovoltaic installations in Germany, Italy, China and Britain. Large-scale solar thermal installations in Spain and the United States also contributed to growth during the year. Wind power investment slipped 12 percent to $84 billion as a result of uncertainty about energy policy in Europe and fewer new installations in China, according to the report.

Despite the substantial investments in solar energy, the industry is in turmoil. A number of large American manufacturers such as Solyndra, Evergreen Solar, SpectraWatt, Solar Millennium and Solon fell victim to price pressure from Chinese rivals that helped to halve the cost of photovoltaic modules in 2011.

Even the survivors are not doing well. Shares of First Solar, Inc. (NASDAQ:FSLR), are selling at their lowest level in five years. The company, which is the leading solar company in the United States, lost $39.5 million last year. In the first quarter of this year, First Solar reported a loss of $449 million after non-recurring expenses of $405 million. The company is due to report second quarter results on August 1.

Not unexpectedly, the industry’s poor fundamentals are provoking trade battles. In May, the U.S. Commerce Department found several Chinese solar-panel companies guilty of dumping and imposed 31 percent tariffs on their products. The action came as a result of a complaint filed by the American subsidiary of Germany’s SolarWorld AG (DE:SWV) and a half-dozen other solar-energy companies that said that the Chinese manufacturers are selling solar panels at below-market prices. The Chinese companies affected are Suntech Power Holdings Co. Ltd. (NYSE:STP) and Trina Solar Limited (NYSE:TSL). SolarWorld has now asked the European Union to investigate claims that Chinese rivals have been selling their products at below market value in Europe as well.

While China pricing has been devastating for American and European solar manufacturers, it has been no less devastating for their Chinese rivals. Suntech, Trina, Yingli Green Energy Holding Co. Ltd. (NYSE:YGE) and Canadian Solar Inc. (NASDAQ:CSIQ), four of China’s largest solar manufacturers, lost a combined $1.7 billion in 2011, and the shares of all four companies are selling at five year lows.

The economics for the solar industry, both globally and in China, have never been worse, and there are no bright spots on the horizon. Clearly, solar investments in the United States and Europe will take a hit in 2012. However, the underlying unprofitability of the industry is in sharp conflict with China’s long-term goal to derive 20 percent of its energy needs from renewable energy sources as well. How can the Chinese companies continue to operate in the face of such losses? Will China continue to support the industry’s development? These are some of the questions that the country’s new leaders will need to address as they take the helm this fall.[164]

Nuclear power

There are potentially two sources of nuclear power. Fission is used in all current nuclear power plants. Fusion is the reaction that exists in stars, including the sun, and remains impractical for use on earth, as fusion reactors are not available, and have been "fifty years away" - for the last fifty years.[165]

Conventional fission power is sometimes referred to as sustainable, but this is controversial politically due to concerns about peak uranium, radioactive waste disposal, and the risks of a severe accident.

Fission nuclear power has the potential to significantly expand its sustainability from a fuel and waste perspective, such as by the use of breeder reactors; however, significant challenges exist in expanding the role of nuclear power in such a manner.[166]

Nuclear fission has four inherent liabilities - radiation, risk of accident, waste, and risk of proliferation of nuclear weapons, and is not likely to have a significant role, due to the vast availability of wind power and solar power.[167][168]

See also

- Ashden Awards for sustainable energy

- Biosphere Technology

- Energy Globe Awards

- Energy and the environment

- Energy park

- Environmental issues with energy

- Hydrogen economy

- International Renewable Energy Agency

- INFORSE, International Network for Sustainable Energy

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)

- Low-energy house

- REEEP, Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership

- Renewable Energy (not the same)

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable energy in the People's Republic of China

- U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

- Sustainable Energy for All initiative

- The Venus Project

- Wind farm

References

- ^ "The Twin Pillars of Sustainable Energy: Synergies between Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Technology and Policy". Aceee.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Renewable Energy and Efficiency Partnership (2004). "Glossary of terms in sustainable energy regulation" (PDF). Retrieved 19 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Sustainable Energy Community :: invVest | invVEST Definition of Sustainable Energy". invVest. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Jamaica Sustainable Development Network. "Glossary of terms". Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ "Green Power Defined | Green Power Partnership | US EPA". Epa.gov. 28 June 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ "The importance of sustainable energy".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j International Energy Agency (2007). Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet, OECD, 34 pages. Cite error: The named reference "IEA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jacobson, Mark Z. (2009). "Review of solutions to global warming, air pollution, and energy security". Energy and Environmental Science. 2 (2). Royal Society of Chemistry: 148. doi:10.1039/b809990c. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Hydroelectric power's dirty secret revealed New Scientist, 24 February 2005.

- ^ Ferris, David (3 November 2011). "The Power of the Dammed: How Small Hydro Could Rescue America's Dumb Dams". Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Biomass Briquettes". 27 August 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ GWEC, Global Wind Report Annual Market Update

- ^ "Solar water heating". Rmi.org. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ "Solar assisted air-conditioning of buildings". Iea-shc.org. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Energy and the Environment, Jack J Kraushaar and Robert A Ristinen, section 4.2 Energy from the Sun pg.92

- ^ "Largest U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System Begins Construction at Nellis Air Force Base". Prnewswire.com. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ This story was written by Airman 1st Class Ryan Whitney. "Nellis activates Nations largest PV Array". Nellis.af.mil. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Australia advances with solar power The Times, 26 October 2006.

- ^ "Solar Systems projects". Solarsystems.com.au. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ 62 MW Solar PV Project Quietly Moves Forward Renewable Energy Access, 18 November 2005.

- ^ World’s largest solar power plant being built in eastern Germany[dead link]

- ^ "Wind energy gathers steam, US biggest market: survey". Google.com. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ World Wind Energy Association (2008). Wind turbines generate more than 1 % of the global electricity

- ^ "Global wind energy markets continue to boom – 2006 another record year" (PDF). Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ European wind companies grow in U.S.

- ^ Stephens, Ben (5 March 2007). "Solar One is "go" for launch". Lvbusinesspress.com. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ "Israeli company drives the largest solar plant in the world". Isracast.com. 13 March 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ America and Brazil Intersect on Ethanol Renewable Energy Access, 15 May 2006.

- ^ "How to manage our oil addiction - CESP". Cesp.stanford.edu. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ New Rig Brings Brazil Oil Self-Sufficiency Washington Post, 21 April 2006.

- ^ Worldwatch Institute and Center for American Progress (2006). American energy: The renewable path to energy security

- ^ International Energy Agency (2006). World Energy Outlook 2006 p. 8.

- ^ Biotechnology Industry Organization (2007). Industrial Biotechnology Is Revolutionizing the Production of Ethanol Transportation Fuel pp. 3-4.

- ^ Douglas, C. A.; Harrison, G. P.; Chick, J. P. (2008). "Life cycle assessment of the Seagen marine current turbine". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part M: Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment. 222 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1243/14750902JEME94.

- ^ Sea machine makes waves in Europe BBC News, 15 March 2006.

- ^ Wave energy contract goes abroad BBC News, 19 May 2005.

- ^ Ricardo David Lopes (1 July 2010). "Primeiro parque mundial de ondas na Póvoa de Varzim". Jn.sapo.pt. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Orkney to get 'biggest' wave farm BBC News, 20 February 2007.

- ^ Turbine technology is turning the tides into power of the future[dead link]

- ^ "SeaGen Turbine Installation Completed". Renewableenergyworld.com. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Nanosolar ships first panels[dead link]

- ^ Solar power nanotechnology may cut cost in half, executives say[dead link]

- ^ Collings AF and Critchley C. Artificial Photosynthesis- from Basic Biology to Industrial Application. WWiley-VCH. Weinheim (2005) p xi.

- ^ "MIT creates first Solar Leaf". geek.com. 30 September 2011.

- ^ Concepts for new sustainable energy technologies

- ^ InterAcademy Council (2007). Lighting the way: Toward a sustainable energy future

- ^ American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (2007). The Twin Pillars of Sustainable Energy: Synergies between Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Technology and Policy Report E074.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007), p. 17.

- ^ a b Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2008 p. 8.

- ^ The Guardian. London http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/georgemonbiot/2009/feb/20/george-monbiot-nuclear-climate).

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) [dead link] - ^ Lovelock, James (2006). The Revenge of Gaia. Reprinted Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-0-14-102990-0

- ^ "End the nuclear age | Greenpeace International". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/international/press/reports/briefing-nuclear-not-answer-apr07.pdf

- ^ "When Clean Energy Is Not Enough". OpEdNews. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ San Francisco Community Choice Program Design, Draft Implementation Plan and H Bond Action Plan, Ordinance 447-07, 2007.

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability.[1]

- ^ "Energy Distribution"U.S. Department of Energy Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability.[2]

- ^ [Whittington, H.W. "Electricity generation: Options for reduction in carbon emissions". Philosophical transactions in mathematics, physical, and engineering sciences. Vol. 360, No. 1797. (Aug. 15, 2002) Published by: The Royal Society]

- ^ Romm, Joseph; Levine, Mark; Brown, Marilyn; Peterson, Eric. “A road map for U.S. carbon reductions”. Science, Vol. 279, No. 5351. (Jan. 30, 1998). Washington

- ^ [Britt, Robert Roy. “Could Space-Based Power Plants Prevent Blackouts?”. Science. (August 15, 2003)]

- ^ Eugene Green Energy Standard, Eugene Network. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ Zeman, Frank S.; Keith, David W. (2008). "Carbon neutral hydrocarbons" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Part A. 366: 3901–18. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0143. Retrieved 7 September 2012. (Review.)

- ^ Wang, Wei; Wang, Shengping; Ma, Xinbin; Gong, Jinlong (2011). "Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide" (PDF). Chemical Society Reviews. 40 (7): 3703–27. doi:10.1039/C1CS15008A. Retrieved 7 September 2012. (Review.)

- ^ a b MacDowell, Niall; et al. (2010). "An overview of CO2 capture technologies". Energy and Environmental Science. 3 (11): 1645–69. doi:10.1039/C004106H. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) (Review.) - ^ a b Musadi, M.R.; Martin, P.; Garforth, A.; Mann, R. (2011). "Carbon neutral gasoline re-synthesised from on-board sequestrated CO2" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Transactions. 24: 1525–30. doi:10.3303/CET1124255. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ a b Eisaman, Matthew D.; et al. (2012). "CO2 extraction from seawater using bipolar membrane electrodialysis" (PDF). Energy and Environmental Science. 5 (6): 7346–52. doi:10.1039/C2EE03393C. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Graves, Christopher; Ebbesen, Sune D.; Mogensen, Mogens; Lackner, Klaus S. (2011). "Sustainable hydrocarbon fuels by recycling CO2 and H2O with renewable or nuclear energy". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 15 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.07.014. Retrieved 7 September 2012. (Review.)

- ^ a b c Socolow, Robert (1 June 2011). Direct Air Capture of CO2 with Chemicals: A Technology Assessment for the APS Panel on Public Affairs (PDF) (peer reviewed literature review). American Physical Society. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Goeppert, Alain; Czaun, Miklos; Prakash, G.K. Surya; Olah, George A. (2012). "Air as the renewable carbon source of the future: an overview of CO2 capture from the atmosphere". Energy and Environmental Science. 5 (7): 7833–53. doi:10.1039/C2EE21586A. Retrieved 7 September 2012. (Review.)

- ^ House, K.Z.; Baclig, A.C.; Ranjan, M.; van Nierop, E.A.; Wilcox, J.; Herzog, H.J. (2011). "Economic and energetic analysis of capturing CO2 from ambient air" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (51): 20428–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012253108. Retrieved 7 September 2012. (Review.)

- ^ Lackner, Klaus S.; et al. (2012). "The urgency of the development of CO2 capture from ambient air". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (33): 13156–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108765109. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ a b c Pearson, R.J.; Eisaman, M.D.; et al. (2012). "Energy Storage via Carbon-Neutral Fuels Made From CO2, Water, and Renewable Energy" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 100 (2): 440–60. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2011.2168369. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help) (Review.) - ^ a b Pennline, Henry W.; et al. (2010). "Separation of CO2 from flue gas using electrochemical cells". Fuel. 89 (6): 1307–14. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2009.11.036. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Graves, Christopher; Ebbesen, Sune D.; Mogensen, Mogens (2011). "Co-electrolysis of CO2 and H2O in solid oxide cells: Performance and durability". Solid State Ionics. 192 (1): 398–403. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2010.06.014. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft (5 May 2010). "Storing green electricity as natural gas". fraunhofer.de. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Center for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research Baden-Württemberg (2011). "Verbundprojekt 'Power-to-Gas'" (in German). zsw-bw.de. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Center for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research (24 July 2012). "Bundesumweltminister Altmaier und Ministerpräsident Kretschmann zeigen sich beeindruckt von Power-to-Gas-Anlage des ZSW" (in German). zsw-bw.de. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Doty Windfuels

- ^ CoolPlanet Energy Systems

- ^ Air Fuel Synthesis, Ltd.

- ^ DiMascio, Felice (23 July 2010). Extraction of Carbon Dioxide from Seawater by an Electrochemical Acidification Cell. Part 1 - Initial Feasibility Studies (memorandum report). Washington, DC: Chemistry Division, Navy Technology Center for Safety and Survivability, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Willauer, Heather D. (11 April 2011). Extraction of Carbon Dioxide from Seawater by an Electrochemical Acidification Cell. Part 2 - Laboratory Scaling Studies (memorandum report). Washington, DC: Chemistry Division, Navy Technology Center for Safety and Survivability, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bloomberg Energy Prices Bloomberg.com (compare to off-peak wind power price graph.)

- ^ Holte, Laura L. (2010). Sustainable Transportation Fuels From Off-peak Wind Energy, CO2 and Water (PDF). 4th International Conference on Energy Sustainability, May 17–22, 2010. Phoenix, Arizona: American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Willauer, Heather D. (29 September 2010). Feasibility and Current Estimated Capital Costs of Producing Jet Fuel at Sea (memorandum report). Washington, DC: Chemistry Division, Navy Technology Center for Safety and Survivability, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rath, B.B., U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (2012). Energy After Oil (PDF). Materials Challenges in Alternative and Renewable Energy Conference, February 27, 2012. Clearwater, Florida: American Ceramic Society. p. 28. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2004/l_052/l_05220040221en00500060.pdf

- ^ "Energiamarkkinavirasto". Energiamarkkinavirasto.fi. Retrieved 8 July 2010.