Xinjiang

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region | |

|---|---|

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 新疆维吾尔自治区 (Xīnjiāng Wéiwú'ěr Zìzhìqū) |

| • Abbreviation | 新 (pinyin: Xīn) |

| • Uyghur | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى |

| • Uyghur transl. | Shinjang Uyghur Aptonom Rayoni |

Map showing the location of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region | |

| Named for | 新 xīn – new 疆 jiāng – frontier "new frontier" |

| Capital | Ürümqi |

| Largest city | Ürümqi |

| Divisions | 14 prefectures, 99 counties, 1005 townships |

| Government | |

| • Secretary | Zhang Chunxian (张春贤) |

| • Governor | Nur Bekri (نۇر بەكرى or 努尔·白克力) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,660,001 km2 (640,930 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 21,813,334 |

| • Rank | 25th |

| • Density | 13/km2 (30/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 29th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | Uyghur – 43.3% Han – 41% Kazakh – 8.3% Hui – 5% Kyrgyz – 0.9% Mongol – 0.8% Dongxiang – 0.3% Pamiris – 0.2% Xibe – 0.2% |

| • Languages and dialects | Lanyin Mandarin, Zhongyuan Mandarin, Beijing Mandarin, Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Oirat, Mongolian and 41 other languages |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-65 |

| GDP (2011) | CNY 657.5 billion US$ 101.7 billion (25th) |

| - per capita | CNY 29,924 US$ 4,633 (19th) |

| HDI (2008) | 0.774 (medium) (21st) |

| Website | www.xinjiang.gov.cn |

Template:Contains Arabic text Template:Contains Chinese text Xinjiang (Uyghur: شىنجاڭ, romanized: Shinjang; Mandarin pronunciation: [ɕíntɕjɑ́ŋ]; Chinese: 新疆; pinyin: Xīnjiāng; Wade–Giles: Hsin1-chiang1; postal map spelling: Sinkiang), officially Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,[1] is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China in the northwest of the country. It is the largest Chinese administrative division and spans over 1.6 million km2. Xinjiang borders Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. It has abundant oil reserves and is China's largest natural gas-producing region.

| Xinjiang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 新疆 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Sinkiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 新疆維吾爾自治區 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 新疆维吾尔自治区 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠰᠢᠨᠵᠢᠶᠠᠩ ᠤᠶᠢᠭᠤᠷ ᠤᠨ ᠥᠪᠡᠷᠲᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠵᠠᠰᠠᠬᠤ ᠣᠷᠤᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh | شينجياڭ ۇيعۇر اۆتونوميالى رايونى Шыңжаң Ұйғыр аутономиялық ауданы Şïnjyañ Uyğur avtonomyalı rayonı | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz | شئنجاڭ ۇيعۇر اپتونوم رايونۇ Шинжаң-Уйгур автоном району Şincañ Uyğur avtonom rayonu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat | Zuungar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is home to a number of ethnic groups including the Uyghur, Han, Kazakh, Tajiks, Hui, Kyrgyz, and Mongol, with a majority of the population adhering to Islam.[2] More than a dozen autonomous prefectures and counties for minorities are in Xinjiang. Older English-language reference works often refer to the area as Chinese Turkestan.[3] Xinjiang is divided into the Dzungarian Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south by a mountain range. Only about 4.3% of Xinjiang's land area is fit for human habitation.[4]

With a documented history of at least 2,500 years, a succession of peoples and empires has vied for control over all or parts of this territory. Before the 21st century, all or part of the region has been ruled, controlled, influenced by the Tocharians, Yuezhi, Xiongnu Empire, Kushan Empire, Han Empire, Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, Western Liáng, Xianbei state, Rouran Khaganate, Tang Dynasty, Uyghur Khaganate, Kara-Khitan Khanate, Mongol Empire, Yuan Dynasty, Northern Yuan, Dzungar Khanate, Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China and, since 1950, the People's Republic of China.

Names

Xinjiang was previously known as Xiyu (西域) or Qurighar / Qarbi Diyâr" (غەربىي دىيار), meaning Western Region, under the Han Dynasty, which drove the Xiongnu empire out of the region in 60 BC. This was in an effort to secure the profitable routes of the Silk Road.[5] It was known as Huijiang (回疆), meaning "Muslim Frontier," during the Qing Dynasty before becoming the province of Xinjiang, which literally means "New Frontier" or "New Border," in the 1880s.

The general region of Xinjiang has been known by many names in earlier times including 西域 (Mandarin: xiyu) = 'Western Regions',[6] Khotan, Khotay, Chinese Tartary, High Tartary, East Chagatay, Mugholistan, Kashgaria, Altishahr ('the six cities' of the Tarim), Little Bokhara and Serindia.[7] The name "Xinjiang", which literally means "New Frontier," was given during the Qing Dynasty. Present-day Jinchuan County was known as "Jinchuan Xinjiang", etc. After 1821, the Qing changed the names of the other regained regions, and "Xinjiang" became the name specifically of present-day Xinjiang.[8]

In 1955, Xinjiang province was renamed Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The name that was originally proposed was simply "Xinjiang Autonomous Region". Saifuddin Azizi, the first chairman of Xinjiang, registered his strong objections to the proposed name with Mao Zedong arguing that "autonomy is not given to mountains and rivers. It is given to particular nationalities." Mao agreed and the administrative region was named "Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region" to recognize its significant ethnic Uyghur population.

Description

Xinjiang is a large, sparsely populated area, spanning over 1.6 million km2 (comparable in size to Iran), which takes up about one sixth of the country's territory. Xinjiang borders the Tibet Autonomous Region and India's Leh District to the south and Qinghai and Gansu provinces to the southeast, Mongolia to the east, Russia to the north, and Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India to the west.

The east-west chain of the Tian Shan Mountains separate Dzungaria in the north from the Tarim Basin in the south. Dzungaria is a dry steppe and the Tarim Basin is a desert surrounded by oases. In the east is the Turpan Depression. In the west, the Tian Shan split, forming the Ili River valley.

History

Early history

The first people lived in Xinjang were Central Asian mongoloid people and few thousand years ago European migrants came in the Xinjang. According to J.P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, the Chinese sources describe the existence of "white people with lightish hair" or the Bai people in the Shan Hai Jing, who lived beyond their northwestern border.[9]

The well-preserved Tarim mummies with reddish or blond hair, today displayed at the Ürümqi Museum and dated to the 3rd century BC, have been found in precisely the same area of the Tarim Basin.[11] Nomadic tribes such as the Yuezhi were part of the large migration of Indo-European speaking peoples who were settled in eastern Central Asia (possibly as far as Gansu). The Ordos in northern China east of the Yuezhi are another example.

Nomadic cultures such as the Yuezhi are documented in the area of Xinjiang where the first known reference to the Yuezhi was made in 645 BC by the Chinese Guan Zhong in his Guanzi 管子 (Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yuzhi 禺氏, or Niuzhi 牛氏, as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains of Yuzhi 禺氏 at Gansu.[12] The supply of jade[13] from the Tarim Basin from ancient times is well documented archaeologically: "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BC the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China."[14]

The nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi are documented in detail in Chinese historical accounts, in particular the 2nd–1st century BC "Records of the Great Historian", or Shiji, by Sima Qian, which state that they "were flourishing" but regularly in conflict with the neighboring tribe of the Xiongnu to the northeast. According to these accounts:

The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan, where they attacked and conquered the people of Daxia and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui [= Oxus] River. A small number of their people who were unable to make the journey west sought refuge among the Qiang barbarians in the Southern Mountains, where they are known as the Lesser Yuezhi.[15]

Xiongnu Empire

Traversed by the Northern Silk Road,[16] the Tarim and Dzungaria regions were known as the Western Regions. At the beginning of the Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 220), the region was subservient to the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people based in modern Mongolia.

Han Dynasty

In the 2nd century BC, Han China sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the states in the region, beginning several decades of struggle between the Xiongnu and Han China over dominance of the region, eventually ending in Chinese success. In 60 BC Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions (西域都護府) at Wulei (烏壘; near modern Luntai) to oversee the entire region as far west as the Pamir. Tarim Basin was under the influence and control of the Han dynasty.

During the usurpation of Wang Mang in China, the dependent states of the protectorate rebelled and became independent from China in AD 13. Over the next century, Han China conducted several expeditions into the region, re-establishing the protectorate from 74 to 76, 91 to 107, and from 123 onward. These campaigns expanded Han sovereignty into the Tarim Basin and Central Asia. This region was also ruled by the Kushan Empire between 114 and 168. After the fall of the Han Dynasty, the protectorate continued to be maintained by Cao Wei (until 265) and the Western Jin Dynasty (from 265 onward).

A summary of classical sources on the Seres (Greek and Roman name of Xinjiang) (essentially Pliny and Ptolemy) gives the following account:

The region of the Seres is a vast and populous country, touching on the east the Ocean and the limits of the habitable world, and extending west nearly to Imaus and the confines of Bactria. The people are civilised men, of mild, just, and frugal temper, eschewing collisions with their neighbours, and even shy of close intercourse, but not averse to dispose of their own products, of which raw silk is the staple, but which include also silk stuffs, furs, and iron of remarkable quality.

— Henry Yule, Cathey and the way thither

Ptolemy had good information on Xinjiang, taken from three accounts.[17]

A succession of peoples

The Western Jin Dynasty succumbed to successive waves of invasions by nomads from the north at the beginning of the 4th century. The short-lived kingdoms that ruled northwestern China one after the other, including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liáng, all attempted to maintain the protectorate, with varying degrees of success. After the final reunification of northern China under the Northern Wei empire, its protectorate controlled what is now the southeastern region of Xinjiang. Local states such as Shule, Yutian, Guizi and Qiemo controlled the western region, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Gaochang, remnants of a state (Northern Liang) that once ruled part of what is now Gansu province in northwestern China.

Tang Dynasty

During the Tang Dynasty, a series of expeditions were conducted against the Western Turkic Khaganate, and their vassals, the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[18] The campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[19] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[20]

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who dispatched an army in 657 led by Su Dingfang against the Western Turk qaghan Ashina Helu. Ashina's defeat strengthened Tang rule in southern Xinjiang and brought the regions formerly controlled by the khaganate into the Tang empire.[20] Xinjiang was administered through the Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府; "Protectorate Pacifying the West") and the Four Garrisons of Anxi.

Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains in modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks, but the Tang retained a military presence in Xinjiang. These holdings were later invaded by the Tibetan Empire to the south in 670. Xinjiang alternated between Tang and Tibetan rule as they competed for control of Central Asia.[21]

A significant milestone of the Tang period of Xinjiang was that it marked the end of Indo-European influence in Xinjiang.[19] Xinjiang was transitioning into a region that was linguistically Turko-Mongolic and religiously Islamic.[21]

Uyghur Khaganate and Western Liao Dynasty

During the devastating Anshi Rebellion, which nearly led to the destruction of the Tang dynasty, Tibet invaded the Tang on a wide front, from Xinjiang to Yunnan. It occupied the Tang capital of Chang'an in 763 for 16 days, and took control of southern Xinjiang by the end of the century. At the same time, the Uyghur Khaganate took control of northern Xinjiang, as well as much of the rest of Central Asia, including Mongolia.

As both Tibet and the Uyghur Khaganate declined in the mid-9th century, the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which was a confederation of Turkic tribes such as the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghmas,[22] took control of western Xinjiang in the 10th century and the 11th century. Meanwhile, after the Uyghur khanate in Mongolia had been smashed by the Kirghiz in 840, branches of the Uyghurs established themselves in Qocha (Karakhoja) and Beshbalik, near the modern cities of Turfan and Urumchi. This Uyghur state remained in eastern Xinjiang until the 13th century, though it was subject to foreign overlords during that time. The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam. The Uyghur state in eastern Xinjiang remained Manichaean, but later converted to Buddhism.

In 1132, remnants of the Khitan Empire from Manchuria entered Xinjiang, fleeing the rebellion of their neighbors, the Jurchens. They established an exile Chinese empire, the Western Liao, which ruled over both the Kara-Khanid-held and Uyghur-held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century.

Mongol Empire, Chagatai Khanate, and Yuan Dynasty

After Genghis Khan unified Mongolia and began his advance west, the Uyghur state in the Turpan-Urumchi area offered its allegiance to the Mongols in 1209, contributing taxes and troops to the Mongol imperial effort. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom. By contrast, Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire conquered the Western Liao in 1218. During the era of the Mongol Empire, the Yuan Dynasty vied with the Chagatai Khanate for rule over the area, with the latter taking control of most of this region. After the break-up of the Chagatai Khanate into smaller khanates in the mid-14th century, the region fractured and was ruled by numerous Persianized Mongol Khans simultaneously, including the ones of Mogholistan (with the assistance of the local Dughlat Emirs), Uigurstan (later Turpan), and Kashgaria. These leaders engaged in wars with each other and the Timurids of Transoxania to the west and the Western Mongols to the east, the successor Chagatai regime based in Mongolia and in China. Although the region did produce examples of high Persian culture during the period (e.g., the Dughlat historian Hamid-mirza), succession crises and internal divisions (Kashgaria split in two for centuries) meant that little was written about the region during the 16th and 17th centuries.[23] In the 17th century, the Mongolian Dzungars established an empire over much of the region.

Dzungar Empire

The Mongolian Dzungar (also Jungar, Zunghar or Zungar; Mongolian: Зүүнгар Züüngar) was the collective identity of several Oirat tribes that formed and maintained one of the last nomadic empires. The Dzungar Khanate covered the area called Dzungaria and stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan, and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. Most of this area was only renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire. It existed from the early 17th century to the mid-18th century.

Qing Dynasty

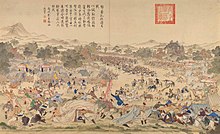

The Manchu Qing Dynasty gained control over eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzunghars that began in the 17th century. In 1755, with the help of the Oirat nobel Amursana, the Qing attacked Ghulja, and captured the Dzunghar khan. After Amursana's request to be declared Zunghar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Over the next two years, Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzunghar khanate and many Chinese Muslims (Hui) moved into the pacified areas.[24]

The Dzungars suffered heavily from the brutal campaigns and from a simultaneous smallpox epidemic. One writer, Wei Yuan, described the resulting desolation in what is now northern Xinjiang as: "an empty plain for several thousand li, with no Oirat yurt except those surrendered."[25] It has been estimated that 80% of the 600,000 or more Zunghars were destroyed by a combination of disease and warfare,[26] and it took generations for it to recover.[27]

Khojas or Khawaja or Khwaja Dynasty

After the defeat of the Dzungars, the Qing made members of a clan of Sufi shaykhs known as the Khojas, rulers in the western Tarim Basin, south of the Tianshan Mts. In 1758–59, however, rebellions against this arrangement broke out both north and south of the Tian Shan mountains. The Qing were then forced, contrary to their initial intent, to establish a form of direct military rule over both Dzungaria (northern Xinjiang) and the Tarim Basin (southern Xinjiang). The Manchus put the whole region under the rule of a General of Ili, (Chinese: 伊犁将军), who established a center of government at the fort of Huiyuan (the so-called "Manchu Kuldja", or Yili), 30 km west of Ghulja (Yining).

After 1759 state farms were established, "especially in the vicinity of Urumchi, where there was fertile, well-watered land and few people." From 1760 to 1830 more state farms were opened and the Chinese population in Xinjiang grew rapidly to about 155,000.[28]

Jahangir Khoja invaded Kashgar in 1826 and the Khanate of Kokand conducted raids on Xinjiang. A large slave trade existed in Xinjiang during this time.

By the mid-19th century, the Russian Empire was encroaching upon Qing China along its entire northern frontier. The Opium Wars and the Taiping and other rebellions had severely weakened the dynasty's ability to maintain its garrisons in distant Xinjiang. In 1864 both Chinese Muslims (Hui) and Uyghurs rebelled in Xinjiang cities, following on-going Chinese Muslim Rebellions in Gansu and Shaanxi provinces further east.[30] Yaqub Beg's Turkic Muslim troops also committed massacres upon the Chinese Muslims.[31] In 1865, Yaqub Beg, a warlord from the neighbouring Khanate of Kokand, entered Xinjiang via Kashgar and conquered nearly all of Xinjiang over the next six years.[32] At the Battle of Ürümqi (1870) Yaqub Beg's Turkic forces, allied with a Han Chinese militia, attacked and besieged Chinese Muslim forces in Urumqi. In 1871, Russia took advantage of the chaotic situation and seized the rich Ili River valley, including Gulja. At the end of this period, forces loyal to the Qing held onto only a few strongholds, including Tacheng.

Yaqub Beg's rule lasted until the Qing general Zuo Zongtang (also known as General Tso) reconquered the region between 1875 and 1877. In 1881, the Qing recovered the Gulja region through diplomatic negotiations, via the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881).

In 1884 (or 1882 according to some sources),[33] the Qing dynasty established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province, formally applying to it the political systems of the rest of China and dropping the old name of Huijiang, or "Muslimland".[34][35]

Republican era

In 1912, the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor of Xinjiang, fled. One of his subordinates, Yang Zengxin (杨增新), took control of the province and acceded in name to the Republic of China in March of the same year. Through Machiavellian politics and clever balancing of mixed ethnic constituencies, Yang maintained control over Xinjiang until his assassination in 1928.[36]

The Kumul Rebellion and other rebellions arose against his successor Jin Shuren (金树仁) in the early 1930s throughout Xinjiang, involving Uyghurs, other Turkic groups, and Hui (Muslim) Chinese. Jin drafted White Russians to crush the revolt. In the Kashgar region on November 12, 1933, the short-lived self-proclaimed East Turkistan Republic was declared, after some debate over whether the proposed independent state should be called "East Turkestan" or "Uyghuristan."[37][38] The region claimed by the ETR in theory encompassed Kashgar, Khotan and Aqsu prefectures in southwestern Xinjiang.[39] The Chinese Muslim Kuomintang 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army) destroyed the army of the First East Turkestan Republic at the Battle of Kashgar (1934), bringing the Republic to an end after the Chinese Muslims executed the two Emirs of the Republic, Abdullah Bughra and Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra. The Soviet Union invaded the province in the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang. In the Xinjiang War (1937), the entire province was brought under the control of northeast Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai (盛世才), who ruled Xinjiang for the next decade with close support from the Soviet Union, many of whose ethnic and security policies Sheng instituted in Xinjiang. The Soviet Union maintained a military base in Xinjiang and had several military and economic advisors deployed in the region. Sheng invited a group of Chinese Communists to Xinjiang, including Mao Zedong's brother Mao Zemin, but in 1943, fearing a conspiracy, Sheng executed them all, including Mao Zemin.

1949–present

A Second East Turkistan Republic (2nd ETR, also known as the Three Districts Revolution) existed from 1944 to 1949 with Soviet support in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture (Ili, Tarbagatay and Altay Districts) in northern Xinjiang.[37] The Second East Turkistan Republic came to an end when the People's Liberation Army entered Xinjiang in 1949.[38] Also, five ETR leaders, who would negotiate the final status of East Turkistan with the Chinese, died in an air crash in 1949 in Soviet airspace over the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.[40]

The Chinese Muslim General Bai Chongxi advocated swamping Xinjiang with disbanded Chinese soldiers to prevent the Soviet union from seizing control during this time.[41]

According to the PRC interpretation, the 2nd ETR was Xinjiang's revolution, a positive part of the communist revolution in China; the 2nd ETR acceded to and welcomed the PLA when it entered Xinjiang, a process known as the Peaceful Liberation of Xinjiang. However, independence advocates view the ETR as an effort to establish an independent state, and the subsequent PLA entry as an invasion. [citation needed]

The autonomous region of the PRC was established on October 1, 1955, replacing the province.[38]

The PRC's first nuclear test was carried out at Lop Nur, Xinjiang, on October 16, 1964. A Japanese researcher known for prominently opposing the tests as "the Devil's conduct" speculated that between 100,000 and 200,000 people may have been killed due to the consequential radiation,[42] although the Lop Nur area has not been permanently inhabited since the 1920s,[43] being located between the Taklamakan and Kumtag deserts in Ruoqiang County, which has an area of almost 200,000 km2 with a population density of only .16/km2. Chinese media challenged this conclusion without providing an alternate number.[44]

During the Great Chinese Famine (1958–1961), Xinjiang experienced a great emigration of residents both to the Soviet Union and to East China. After a number of student demonstrations in the 1980s, the Baren Township riot of April 1990 led to more than 20 deaths.[45] 1997 saw the Ghulja Incident and Urumqi bus bombs,[46] while police continue to battle with religious separatists from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement.

Han Youwen, a Salar general, once served as vice chairman of Xinjiang.

During the Cold War and the Sino-Soviet split, China stationed military forces in Xinjiang to guard against Soviet attack, and the Chinese used Xinjiang to supply and train anti-Soviet Islamic militants during the Islamic insurgency against the Soviet backed Afghan communists.

During the Sino-Soviet split, strained relations between China and Soviet Russia resulted in bloody border clashes and mutual backing for the opponents enemies. China and Afghanistan had neutral relations with each other during the King's rule. When the pro Soviet Afghan communists seized power in Afghanistan in 1978, relations between China and the Afghan communists quickly turned hostile. The Afghan pro-Soviet communists supported China's enemies in Vietnam and blamed China for supporting Afghan anti-communist militants. China responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by supporting the Afghan Mujahidin and ramping up their military presence near Afghanistan in Xinjiang. China acquired military equipment from America to defend itself from Soviet attack.[47]

The People's Liberation Army trained and supported the Afghan Mujahidin during the Soviet war in Afghanistan. China moved its training camps for the mujahideen from Pakistan into China. Hundreds of millions worth of anti-aircraft missiles, rocket launchers and machine guns were given to the Mujahidin by the Chinese. Chinese military advisors and army troops were present with the Mujahidin during training.[48]

In recent years Xinjiang has been a focal point of ethnic and other tensions.[49][50]

Recent incidents include the 2007 Xinjiang raid,[51] a thwarted 2008 suicide bombing attempt on a China Southern Airlines flight,[52] and the 2008 Xinjiang attack which resulted in the deaths of sixteen police officers four days before the Beijing Olympics.[53][54] Further incidents include the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, the September 2009 Xinjiang unrest, and the 2010 Aksu bombing that led to the trials of 376 people.[55]

From 1949 to 2001, education has expanded greatly in the region, with 6,221 primary schools up from 1,335; 1,929 middle schools up from 9, and institutions of higher learning at 21, up from 1. The illiteracy rate for young and middle-age people has decreased to less than 2%. Agricultural science has made inroads into the region, as well as innovative methods of road construction in the desert.

Culturally, Xinjiang maintains 81 public libraries and 23 museums, compared to none of each in 1949, and Xinjiang has 98 newspapers in 44 languages, up from 4 newspapers in 1952. According to official statistics, the ratios of doctors, medical workers, medical clinics, and hospital beds to people surpass the national average, and immunization rates have reached 85%.[56]

Subdivisions

Xinjiang is divided into two prefecture-level cities, seven prefectures, and five autonomous prefectures for Mongol, Kirgiz, Kazakh and Hui minorities. (Two of the seven prefectures are, in turn, part of Ili, an autonomous prefecture.) These are then divided into 11 districts, 21 county-level cities, 62 counties, and six autonomous counties. Six of the county-level cities do not belong to any prefecture, and are de facto administered by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. Sub-level divisions of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is shown in the picture to the right and described in the table below:

| |||||||

| Map # | SASM/GNC[58] | Administrative Seat | Uyghur (UEY) Uyghur Latin (ULY) |

Hanzi Hanyu pinyin |

Population (2010) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Provincial Autonomous Prefecture | |||||||

| 11 | Ili (for Kazakh) |

Yining (Gulja) | ئىلى قازاق ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى Ili Qazaq Aptonom Oblasti |

伊犁哈萨克自治州 Yīlí Hāsàkè Zìzhìzhōu |

2,482,627 [a] | ||

| Prefecture-level city | |||||||

| 4 | Karamay | Karamay District | قاراماي شەھرى Qaramay Shehri |

克拉玛依市 Kèlāmǎyī Shì |

391,008 | ||

| 8 | Ürümqi | Tianshan District | ئۈرۈمچى شەھرى Ürümchi Shehri |

乌鲁木齐市 Wūlǔmùqí Shì |

3,110,280 | ||

| — Prefecture — | |||||||

| 1 | Altay subordinate to Ili (for Kazakh) |

Altay | ئالتاي ۋىلايىتى Altay Wilayiti |

阿勒泰地区 Ālètài Dìqū |

526,980 | ||

| 3 | Tarbagatay subordinate to Ili (for Kazakh) |

Qoqek | تارباغاتاي ۋىلايىتى Tarbaghatay Wilayiti |

塔城地区 Tǎchéng Dìqū |

1,219,212 | ||

| 9 | Turpan | Turpan | تۇرپان ۋىلايىتى Turpan Wilayiti |

吐鲁番地区 Tǔlǔfān Dìqū |

622,679 | ||

| 10 | Kumul | Kumul | قۇمۇل ۋىلايىتى Qumul Wilayiti |

哈密地区 Hāmì Dìqū |

572,400 | ||

| 13 | Kaxgar | Kaxgar | قەشقەر ۋىلايىتى Qeshqer Wilayiti |

喀什地区 Kāshí Dìqū |

3,979,362 | ||

| 15 | Aksu | Aksu | ئاقسۇ ۋىلايىتى Aqsu Wilayiti |

阿克苏地区 Ākèsū Dìqū |

2,370,887 | ||

| 17 | Hotan | Hotan | خوتەن ۋىلايىتى Xoten Wilayiti |

和田地区 Hétián Dìqū |

2,014,365 | ||

| — Autonomous prefectures — | |||||||

| 2 | Bortala (for Mongol) |

Bortala | بۆرتالا موڭغۇل ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى Börtala Mongghul Aptonom Oblasti |

博尔塔拉蒙古自治州 Bó'ěrtǎlā Měnggǔ Zìzhìzhōu |

443,680 | ||

| 6 | Changji (for Hui) |

Changji | سانجى خۇيزۇ ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى Sanji Xuyzu Aptonom Oblasti |

昌吉回族自治州 Chāngjí Huízú Zìzhìzhōu |

1,428,592 | ||

| 12 | Kizilsu (for Kirgiz) |

Artux | قىزىلسۇ قىرغىز ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى Qizilsu Qirghiz Aptonom Oblasti |

克孜勒苏柯尔克孜自治州 Kèzīlèsū Kē'ěrkèzī Zìzhìzhōu |

525,599 | ||

| 18 | Bayingolin (for Mongol) |

Korla | بايىنغولىن موڭغۇل ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى Bayingholin Mongghul Aptonom Oblasti |

巴音郭楞蒙古自治州 Bāyīnguōlèng Měnggǔ Zìzhìzhōu |

1,078,492 | ||

| — County-level city — (Directly administered by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps) | |||||||

| 5 | Shihezi | Shihezi | شىخەنزە شەھرى Shixenze Shehri |

石河子市 Shíhézǐ Shì |

635,582 | ||

| 7 | Wujiaqu | Wujiaqu | ئۇجاچۇ شەھرى Wujachu Shehri |

五家渠市 Wǔjiāqú Shì |

72,613 | ||

| 14 | Tumxuk | Tumxuk | تۇمشۇق شەھرى Tumshuq Shehri |

图木舒克市 Túmùshūkè Shì |

147,465 | ||

| 16 | Aral | Aral | ئارال شەھرى Aral Shehri |

阿拉尔市 Ālā'ěr Shì |

166,205 | ||

| 19 | Beitun | Beitun | بەيتۈن شەھىرى Beatün Shehiri |

北屯市 Běitún Shì |

76,300 | ||

| 20 | Tiemenguan | Tiemenguan | باشئەگىم شەھىرى Bashegym Shehiri |

铁门关市 Tiĕménguān Shì |

200,000 | ||

a. ^ The population figures does not include Altay Prefecture or Tacheng Prefecture which are subordinate to Ili Prefecture.

Geography and geology

Xinjiang is the largest political subdivision of China—it accounts for more than one sixth of China's total territory and a quarter of its boundary length. It is split by the Tian Shan mountain range (Uyghur: تەڭرى تاغ, romanized: Tengri Tagh), which divides it into two large basins: the Dzungarian Basin in the north, and the Tarim Basin in the south. Much of the Tarim Basin is dominated by the Taklamakan Desert. The lowest point in Xinjiang, and in the entire PRC, is the Turpan Depression, 155 metres below sea level; its highest point is the mountain K2, 8611 metres above sea level, on the border with Pakistan. Other mountain ranges include the Pamir Mountains in the southwest, the Karakoram in the south, and the Altai Mountains in the north.

Most of Xinjiang is young geologically, having been formed from the collision of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate, forming the Tian Shan, Kunlun Shan, and Pamir mountain ranges. Consequently, Xinjiang is a major earthquake zone. Older geological formations occur principally in the far north where the Junggar Block is geologically part of Kazakhstan, and in the east which is part of the North China Craton.

Xinjiang has within its borders the point of land remotest from the sea, the so-called Eurasian pole of inaccessibility (46°16.8′N 86°40.2′E / 46.2800°N 86.6700°E) in the Dzoosotoyn Elisen Desert, 1,645 miles (2,647 km) from the nearest coastline (straight-line distance).

The Tian Shan mountain range marks the Xinjiang-Kyrgyzstan border at the Torugart Pass (3752 m). The Karakorum highway (KKH) links Islamabad, Pakistan with Kashgar over the Khunjerab Pass.

Rivers include the Tarim River.

Time

Officially, Xinjiang is on the same time zone as the rest of China, Beijing Time (UTC+8). However, being roughly two time zones west of the capital, some residents follow their own unofficial Xinjiang Time (UTC+6).[59] The division follows ethnic lines, with Han tending to use Beijing Time and Uighurs tending to use Xinjiang Time; this is seen as a form of resistance to the central government.[60] Regardless of the ethnicity of their proprietors, most businesses and schools open and close according to Xinjiang time, i.e. two hours later than their equivalents in other regions of China.[61]

Deserts

Deserts include:

Major cities

Climate

Generally, a semi-arid or desert climate (Köppen BSk or BWk, respectively) prevails in Xinjiang. The entire region is marked by great seasonal differences in temperature and cold winters. During the summer, the Turpan Depression usually records the hottest temperatures nationwide,[62] with air temperatures easily exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). In the far north and the highest mountain elevations, however, winter temperatures regularly drop below −20 °C (−4 °F).

Bordering regions

- East: Gansu

- Southeast: Qinghai

- South: Tibet Autonomous Region

- Southwest: Jammu and Kashmir (India) Disputed and Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan)—Disputed

- West:

- Badakhshan Province, Afghanistan

- Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province, Tajikistan

- Osh, Naryn, and Issyk Kul Provinces, Kyrgyzstan

- Almaty, East Kazakhstan Provinces, Kazakhstan

- North: Altai Republic, Russia

- Northeast: Bayan-Ölgii, Khovd, Govi-Altai Provinces, Mongolia

Politics

List of Secretaries of the CPC Xinjiang Committee

- Wang Zhen (王震): 1949–1952

- Wang Enmao (王恩茂): 1952–1967

- Long Shujin (龙书金): 1970–1972

- Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎•艾则孜): 1972–1978

- Wang Feng (汪锋): 1978–1981

- Wang Enmao (王恩茂): 1981–1985

- Song Hanliang (宋汉良): 1985–1994

- Wang Lequan (王乐泉): 1994–2010

- Zhang Chunxian (张春贤): 2010−incumbent

List of Chairmen of Xinjiang Government

- Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎•艾则孜): 1955–1967

- Long Shujin (龙书金): 1968–1972

- Saifuddin Azizi: 1972–1978

- Wang Feng (汪锋): 1978–1979

- Ismail Amet (司马义•艾买提): 1979–1985

- Tomur Dawamat (铁木尔•达瓦买提): 1985–1993

- Abdul'ahat Abdulrixit (阿不来提•阿不都热西提): 1993–2003

- Ismail Tiliwaldi (司马义•铁力瓦尔地): 2003–2007

- Nur Bekri (努尔•白克力): 2007−incumbent

Economy

Xinjiang is known for its fruits and produce, including grapes, melons, pears, cotton, wheat, silk, walnuts and sheep. Xinjiang also has large deposits of minerals and oil.

In the late 19th century the region was noted for producing salt, soda, borax, gold, jade and coal.[63]

Xinjiang's nominal GDP was approximately 220 billion RMB (US$28 billion) in 2004 and increased to 657.4 billion RMB (US$104.3 billion) in 2011, due to exploration of the regions abundant reserves of coal, crude oil and natural and the China Western Development policy introduced by the State Council to boost economic development in Western China.[64] Its per capita GDP for 2009 was 19,798 RMB (2,898 USD), with a growth rate of 1.7%.[64] Southern Xinjiang, with 95% non-Han population, has an average per capita income half that of Xinjiang as a whole.[65]

The oil and gas extraction industry in Aksu and Karamay is booming, with the West–East Gas Pipeline connecting to Shanghai. The oil and petrochemical sector account for 60% of Xinjiang's local economy.[66] Xinjiang's exports amounted to 19.3 billion USD, while imports turned out to be 2.9 billion USD in 2008. Most of the overall import/export volume in Xinjiang was directed to and from Kazakhstan through Ala Pass. China's first border free trade zone (Horgos Free Trade Zone) was located at the Xinjiang-Kazakhstan border city of Horgos.[67] Horgos is the largest "land port" in China's western region and it has easy access to the Central Asian market. Xinjiang also opened its second border trade market to Kazakhstan in March 2006, the Jeminay Border Trade Zone.[68]

In July 2010 China Daily reported that:

Local governments in China's 19 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang and Liaoning, are engaged in the commitment of "pairing assistance" support projects in Xinjiang to promote the development of agriculture, industry, technology, education and health services in the region.[69]

Economic and Technological Development Zones

- Bole Border Economic Cooperation Area[70]

- Shihezi Border Economic Cooperation Area[71]

- Tacheng Border Economic Cooperation Area[72]

- Urumqi Economic & Technological Development Zone is northwest of Urumqi. It was approved in 1994 by the State Council as a national level economic and technological development zones. It is 1.5 km from the Urumqi International Airport, 2 km from the North Railway Station, and 10 km from the city center. Wu Chang Expressway and 312 National Road passes through the zone. The development has unique resources and geographical advantages. Xinjiang's vast land, rich in resources, borders eight countries. As the leading economic zone, it brings together the resources of Xinjiang's industrial development, capital, technology, information, personnel and other factors of production.[73]

- Urumqi Export Processing Zone is in Urumuqi Economic and Technology Development Zone. It was established in 2007 as a state-level export processing zone.[74]

- Urumqi New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone was established in 1992, and it is the only high-tech development zone in Xinjiang, China. There are more than 3470 enterprises in the zone, of which 23 are Fortune 500 companies. It has a planned area of 9.8 square kilometres, and it is divided into 4 zones. There are plans to expand the zone.[75]

- Yining Border Economic Cooperation Area[76]

Demographics

The earliest Tarim mummies, dated to 1800 BC, are of a Caucasoid physical type.[77] East Asian migrants arrived in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3,000 years ago, while the Uighur peoples arrived after the collapse of the Orkon Uighur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around the year 842.[78][79]

Muslim Turkic peoples in Xinjiang include Uyghurs, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Tatars and the Kazakhs; Muslim Iranian peoples include Pamiris and the Sarikolis/Wakhis (often conflated as Pamiris); and Muslim Sino-Tibetan peoples such as the Hui. Other PRC ethnic groups in the region include Han, Mongols (Oirats, Dagur, Dongxiang), Russians, Xibes, and Manchus. As of 1945, there were up to 70,000 persons of Russian origin living in Xinjiang.[80]

The Han Chinese of Xinjiang arrived at different times, from different directions and social backgrounds: They are descendants of criminals and officials who had been exiled from China proper during the second half of the eighteenth and first half of the 19th centuries; descendants of families of military and civil officers from Hunan, Yunnan, Gansu and Manchuria; descendants of merchants from Shanxi, Tianjin, Hubei and Hunan and descendants of peasants who started immigrating into the region in 1776.[81]

Some Uighur scholars claim descent from both the Turkic Uighurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (or Tokharians, whose language was Indo-European), and relatively fair-skin, hair and eyes, as well as other so-called 'Caucasoid' physical traits, are not uncommon among them. In general Uyghurs resemble those peoples who live around them in Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Pakistan.

In 2002, there were 9,632,600 males (growth rate of 1.0%) and 9,419,300 females (growth rate of 2.2%). The population overall growth rate was 1.09%, with 1.63% of birth rate and 0.54% mortality rate.

At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang.[82] A census of the time tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 60% Turkic and 30% Han.[83] Before 1831 only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin), and only a few Uyghurs lived in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[84] After 1831 the Qing permitted and encouraged Han Chinese migration into the Tarim basin in southern Xinjiang, although with very little success, and stationed permanent troops on the land there as well.[85] Political killings and expulsions of non Uyghur populations in the uprisings of the 1860s[85] and 1930s saw them experience a sharp decline as a percentage of the total population[86] though they rose once again in the periods of stability following 1880 (which saw Xinjiang increase its population from 1.2 million)[87][88] and 1949. From a low of 7% in 1953, the Han began to return to Xinjiang between then and 1964, where they comprised 33% of the population (54% Uyghur), similarly to Qing times. A decade later, at the beginning of the Chinese economic reform in 1978, the demographic balance was 46% Uyghur and 40% Han;[83] this has not changed drastically until the last census in 2000, with the Uyghur population reduced to 42%.[89] Military personnel are not counted and national minorities are undercounted in the Chinese census, as in most censuses.[90] While some of the shift has be attributed to an increased Han presence,[91] Uyghurs have also emigrated to other parts of China, where their numbers have increased steadily. Uyghur independence activists express concern over the Han population changing the Uyghur character of the region, though the Han and Hui Chinese mostly live in northern Xinjiang Dzungaria, and are separated from areas of historical Uyghur dominance south of the Tian Shan mountains (southwestern Xinjiang), where Uyghurs account for about 90% of the population.[92]

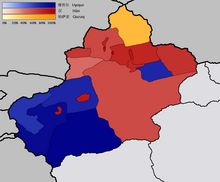

In general, Uyghurs are the majority in southwestern Xinjiang, including the prefectures of Kashgar, Khotan, Kizilsu, and Aksu (about 80% of Xinjiang's Uyghurs live in those four prefectures), as well as Turpan prefecture in eastern Xinjiang. Han are the majority in eastern and northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria), including the cities of Urumqi, Karamay, Shihezi and the prefectures of Changjyi, Bortala, Bayin'gholin, Ili (especially the cities of Kuitun), and Kumul. Kazakhs are mostly concentrated in Ili prefecture in northern Xinjiang. Kazakhs are the majority in the northernmost part of Xinjiang.

| Ethnic groups in Xinjiang. 根据2009年底人口抽查统计[92] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Population | Percentage |

| Uyghur | 10,019,758 | 46.42% |

| Han | 8,416,867 | 38.99% |

| Kazakh | 1,514,814 | 7.02% |

| Hui | 980,359 | 4.54% |

| Kirghiz | 189,309 | 0.88% |

| Mongols, Dongxiangs, Daurs | 179,615 | 0.83% |

| Pamiris | 39,493 | 0.21% |

| Xibe | 42,790 | 0.20% |

| Manchu | 19,493 | 0.11% |

| Tujia | 15,787 | 0.086% |

| Uzbek | 12,096 | 0.066% |

| Russian | 8,935 | 0.048% |

| Miao | 7,006 | 0.038% |

| Tibetan | 6,153 | 0.033% |

| Zhuang | 5,642 | 0.031% |

| Tatar | 4,501 | 0.024% |

| Salar | 3,762 | 0.020% |

| Major ethnic groups in Xinjiang by region, 2000 census.[notes 1]

P = Prefecture; AP = Autonomous prefecture; PLC = Prefecture-level city; DACLC = Directly administered county-level city.[93] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghurs | Han | Kazakhs | others | |

| Xinjiang | 43.6% | 40.6% | 8.3% | 7.5% |

| Ürümqi PLC | 11.8% | 75.3% | 3.3% | 9.6% |

| Karamay PLC | 13.8% | 78.1% | 3.7% | 4.5% |

| Turpan Prefecture | 70.0% | 23.3% | <0.1% | 6.6% |

| Kumul Prefecture | 18.4% | 68.9% | 8.8% | 3.9% |

| Changji AP + Wujiaqu DACLC | 3.9% | 75.1% | 8.0% | 13.0% |

| Bortala AP | 12.5% | 67.2% | 9.1% | 11.1% |

| Bayin'gholin AP | 32.7% | 57.5% | <0.1% | 9.7% |

| Aksu Prefecture + Aral DACLC | 71.8% | 26.6% | 0.1% | 1.4% |

| Kizilsu AP | 64.0% | 6.4% | <0.1% | 29.6% |

| Kashgar Prefecture + Tumushuke DACLC | 89.3% | 9.2% | <0.1% | 1.5% |

| Khotan Prefecture | 96.4% | 3.3% | <0.1% | 0.2% |

| Ili AP[notes 2] | 16.1% | 44.4% | 25.6% | 13.9% |

| – Kuitun DACLC | 0.5% | 94.6% | 1.8% | 3.1% |

| – former Ili Prefecture | 27.2% | 32.4% | 22.6% | 17.8% |

| – Tacheng Prefecture | 4.1% | 58.6% | 24.2% | 13.1% |

| – Altay Prefecture | 1.8% | 40.9% | 51.4% | 5.9% |

| Shihezi DACLC | 1.2% | 94.5% | 0.6% | 3.7% |

Religion

Xinjiang is home to several distinct ethnic groups of various religious traditions. A majority of the region's native population adher to Sunni Islam of the Hanafi rites. A large minority of Shias, almost exclusively of the Ismaili (Seveners) rites are found in the higher mountains of Pamir and Tian Shan. In the western mountains (the Pamirs), almost the entire population of Pamirs, Sarikulis and Wakhis are Ismaili Shia. In the north, in the Tian Shan, it is the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs who practice Ismaili Shiism[2]

Afaq Khoja Mausoleum and Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar are among the most important Islamic sites in Xinjiang. Emin Minaret is a key Islamic site, in Turfan. Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves is a major Buddhist site.

Media

The Xinjiang Networking Transmission Limited operates the Urumqi People Broadcasting Station and the Xinjiang People Broadcasting Station, broadcasting in Mandarin, Uyghur, Kazakh and Mongolian.

As of 1995[update], there were 50 minority-language newspapers published in Xinjiang, including the Qapqal News, the world's only Xibe-language newspaper.[94] The Xinjiang Economic Daily is considered one of China's most dynamic newspapers.[95]

For a time after the July 2009 riots, authorities placed restrictions on the internet and text messaging, gradually permitting access to websites like Xinhua's,[96] until restoring Internet to the same level as the rest of China on May 14, 2010.[97][98][99]

Sports

Xinjiang is home to the Xinjiang Guanghui Flying Tigers professional basketball team of the Chinese Basketball Association.

The capital, Urumqi, is home to the Xinjiang University baseball team, an integrated Uyghur and Han group profiled in the documentary film Diamond in the Dunes.

Transportation

Roads

In 2008, according to the Xinjiang Transportation Network Plan, the government has focused construction on State Road 314, Alar-Hotan Desert Highway, State Road 218, Qingshui River Line-Yining Highway, and State Road 217, as well as other roads.

The construction of the first expressway in the mountainous area of Xinjiang began a new stage in its construction on July 24, 2007. The 56 km highway linking Sayram Lake and Guozi Valley in Northern Xinjiang area had cost 2.39 billion yuan. The expressway is designed to improve the speed of national highway 312 in northern Xinjiang. The project started in August 2006 and several stages have been fully operational since March 2007. Over 3,000 construction workers have been involved. The 700 m-long Guozi Valley Cable Bridge over the expressway is now currently being constructed, with the 24 main pile foundations already completed. Highway 312 national highway Xinjiang section, connects Xinjiang with China's east coast, central and western Asia, plus some parts of Europe. It is a key factor in Xinjiang's economic development. The population it covers is around 40 percent of the overall in Xinjiang, who contribute half of the GDP in the area.

Rail

Xinjiang is linked to the rest of China by a single railway, the Lanzhou-Xinjiang (Lanxin) Railway, which runs from Ürümqi to Lanzhou through the Hexi Corridor in Gansu Province. This railway connects the regional capital, Ürümqi, with Turpan and Hami in eastern Xinjiang. West of Ürümqi, the Northern Xinjiang (Beijiang) Railway runs along the northern footslopes of the Tian Shan range through Changji, Shihezi, Kuytun and Jinghe to the Kazakh border at Alashankou, where it links up with the Turkestan-Siberia Railway of Central Asia. The Lanxin and Beijiang lines form part of the Trans-Eurasian Continental Railway, which extends from Rotterdam, on the North Sea, to Lianyungang, on the East China Sea.

The Second Ürümqi-Jinghe Railway opened in 2009 to supplement rail transport capacity on the Northern Xinjiang Railway between Ürümqi and Jinghe. From Jinghe, the Jinghe-Yining-Horgos Railway heads southwest into the Ili River Valley to Yining, Huocheng, and Khorgos, a second rail border crossing with Kazakhstan. From Kuytun, the Kuytun-Beitun Railway runs north into the Junggar Basin to Karamay and Beitun, near Altay in northern Xinjiang. The Ürümqi-Dzungaria Railway connects Ürümqi with coal fields in the eastern Junggar Basin.

The Southern Xinjiang (Nanjiang) Railway branches off of the Lanxin Line at Turpan and heads southwest along the southern footslopes of the Tian Shan into the Tarim Basin, with stops at Yanqi, Korla, Kuqa, Aksu, Maralbexi (Bachu), Artux, and Kashgar. From Kashgar, the Kashgar-Hotan Railway, follows the southern rim of the Tarim to Hotan, with stops at Shule, Akto, Yengisar, Shache (Yarkant), Yecheng (Karghilik), Moyu (Karakax).

A high-speed railway between Urumqi and Lanzhou is under construction.

Independence of Xinjiang province

The people of Xinjiang province of Uyghur ethnicity struggling to be an independent country which causes many riots in Xinjiang province.[100][101][102] Xinjiang conflict [103] is an ongoing[104] separatist struggle in the northwestern part of today's China. The indigenous Uighur people claim that the region, which they view as their fatherland and refer to as East Turkestan, is not part of China, but was invaded by China in 1949 and is since under Chinese occupation. China claims that the region has been part of China since ancient times, and nowadays calls it Xinjiang ("New Territory" or, officially, "old territory returned to the motherland")[105] province. The separatism effort is led by ethnically Uighur Muslim underground organizations, most notably the East Turkestan independence movement, against the Chinese government.

See also

- List of universities and colleges in Xinjiang

- Cotton industry in China

- Xinjiang coins

- Xinjiang cuisine

- Tibet

- Ningxia

- Inner Mongolia

- Guangxi

- Xinjiang conflict

- Xinjiang Wars

- East Turkestan independence movement

Notes

- ^ Does not include members of the People's Liberation Army in active service.

- ^ Ili AP is composed of Kuitun DACLC, Tacheng Prefecture, Aletai Prefecture, as well as former Ili Prefecture. Ili Prefecture has been disbanded and its former area is now directly administered by Ili AP.

Footnotes

- ^ Xinjang Uyĝur Aptonom Rayoni in SASM/GNC romanization

- ^ a b http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/country_profiles/8152132.stm BBC Regions and territories:Xinjiang

- ^ "Turkestan". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. XV. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1912. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Xinjiang Sees Annual Population Growth of 340,000

- ^ Susan Whitfield (2004). The Silk Road: trade, travel, war and faith. Serindia Publications. p. 27.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hill (2009), pp. xviii, 60.

- ^ Tyler (2003), p. 3.

- ^ "Cultivating and Guarding the West Regions: the Establishment of Xinjiang Province" (in Chinese). China Central Television. December 6, 2004. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ J.P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair The Tarim Mummies, p. 55, ISBN 0-500-05101-1. "The strange creatures of the Shanhai jing: (...) we find recorded north of the territory of the "fish dragons" the land of the Bai, whose bodies are white and whose long hair falls on their shoulders. "

- ^ The Mummies of Xinjiang. DISCOVER Magazine. April 1, 1994.

- ^ Saiget, Robert J. (April 19, 2005). "Caucasians preceded East Asians in basin". The Washington Times. News World Communications. Archived from the original on April 20, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

A study last year by Jilin University also found that the mummies' DNA had Europoid genes.

- ^ Iaroslav Lebedynsky, Les Saces, ISBN 2-87772-337-2, p59.

- ^ Michael Dillon, China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary.

- ^ Liu (2001), pp. 267–268

- ^ Watson, Burton. Trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian of China: Han Dynasty II. Translated from the Shiji of Sima Qian. Chapter 123: "The Account of Dayuan," Columbia University Press. Revised Edition. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk.), p. 234.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan (2007). Andy Burnham (ed.). Silk Road, North China. The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ E. de la Vaissière, "The triple system of orography in Ptolemy's Xinjiang", in Exegisti monumenta Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams, Harrassowitz, 2009

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- ^ a b Twitchett, Denis; Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "Kao-tsung (reign 649-83) and the Empress Wu: The Inheritor and the Usurper". In Denis Twitchett; John Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- ^ a b Skaff, Jonathan Karem (2009). Nicola Di Cosmo (ed.). Military Culture in Imperial China. Harvard University Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- ^ a b Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 33–41. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 5 - The Qarakhanids". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Centra Asia (pages 491–501). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-0627-1.

- ^ Millward (2007), p.98

- ^ Wei Yuan, 聖武記 Sheng Wu Ji, vol. 4.

- ^ Chu, Wen-Djang (1966). The Moslem Rebellion in Northwest China 1862–1878. Mouton & co.. p. 1.

- ^ Tyler (2003), p. 55

- ^ Millward (2007), p. 104

- ^ Yakub Beg-Britannica

- ^ Ho-dong Kim(2004),p.71.

- ^ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1871). Accounts and papers of the House of Commons. Ordered to be printed. p. 34. Retrieved December 28, 2010.(original from Oxford University) August 10, 1871

- ^ Yakub Beg (Pamiri adventurer). Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Mesny (1905), p. 5.

- ^ Tyler (2003), p. 61.

- ^ 从“斌静案”看清代驻疆官员与新疆的稳定

- ^ Governors of Xinjiang: Yang Zengxin (1912–1928), Jin Shuren (1928–33), Sheng Shicai (1933–44) [1].

- ^ a b R. Michael Feener, "Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives", ABC-CLIO, 2004, ISBN 1-57607-516-8

- ^ a b c "Uighurs and China's Xinjiang Region". cfr.org. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978023113924 -3. p.24

- ^ "Uyghur Protests Widen as Xinjiang Unrest Flares". axisoflogic.com. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved June 28, 2010.(Cambridge studies in Chinese history, literature, and institutions, Soviet and East European Studies)

- ^ Did China's Nuclear Tests Kill Thousands and Doom Future Generations?. Scientific American.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/347840/Lop-Nur . Lop Nur. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ China Youth Daily (Qingnian Cankao or Elite Reference), August 7, 2009. Hard copy article (site).

- ^ "China confirms 22 killed in riots". Bangor Daily News. Associated Press. April 23, 1990.

- ^ "China: Human Rights Concerns in Xinjiang". Human Rights Watch. October 17, 2001. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ S. Frederick Starriditor=S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 157. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ S. Frederick Starriditor=S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 158. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (February 16, 2000). "Uyghur "separatism": China's policies in Xinjiang fuel dissent". Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ^ Gunaratna, Rohan; Pereire, Kenneth George (2006). "An al-Qaeda associate group operating in China?" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 4 (2): 59.

Since the Ghulja Incident, numerous attacks including attacks on buses, clashes between ETIM militants and Chinese security forces, assassination attempts, attempts to attack Chinese key installations and government buildings have taken place, though many cases go unreported.

- ^ "Chinese police destroy terrorist camp in Xinjiang, one policeman killed". CCTV International. October 1, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Elizabeth Van Wie Davis, "China confronts its Uyghur threat," Asia Times Online, April 18, 2008.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (August 5, 2008). "Ambush in China Raises Concerns as Olympics Near". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Waterhouse Caulfield Cup breakthrough".

- ^ "China prosecuted hundreds over Xinjiang unrest". The Guardian. London. January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ^ "VI. Progress in Education, Science and Technology, Culture and Health Work". History and Development of Xinjiang. State Council of the People's Republic of China. May 26, 2003. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ References and details on data provided in the table can be found in the individual provincial articles.

- ^ Zhōngguó dìmínglù 中国地名录 (Beijing, Zhōngguó dìtú chūbǎnshè 中国地图出版社 1997); ISBN 7-5031-1718-4.

- ^ Xinjiang time

- ^ Han, Enze (2010), "Boundaries, Discrimination, and Interethnic Conflict in Xinjiang, China", International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4 (2): 251

{{citation}}: soft hyphen character in|title=at position 38 (help) - ^ Clocks square off in China's far west

- ^ Weather China

- ^ Mesny (1899), p. 386.

- ^ a b Xinjiang Province: Economic News and Statistics for Xinjiang's Economy

- ^ Millward (2007), p. 305

- ^ Alain Charles (2005). The China Business Handbook (8th ed.). ISBN 978-0-9512512-8-7.

- ^ "Work on free trade zone on the agenda". People's Daily Online. November 2, 2004. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Xinjiang to open 2nd border trade market to Kazakhstan". Xinhua. December 12, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Efforts to boost 'leapfrog development' in Xinjiang". China Daily/Xinhua. July 5, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ RightSite.asia | Bole Border Economic Cooperation Area

- ^ RightSite.asia | Shihezi Border Economic Cooperation Area

- ^ RightSite.asia | Tacheng Border Economic Cooperation Area

- ^ RightSite.asia | Urumqi Economic & Technological Development Zone

- ^ RightSite.asia | Urumqi Export Processing Zone

- ^ RightSite.asia | Urumuqi Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

- ^ RightSite.asia | Yining Border Economic Cooperation Area

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000). "The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West". London: Thames & Hudson: 237.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ A meeting of civilisations: The mystery of China's celtic mummies. The Independent. August 28, 2006.

- ^ Rumbles on the Rim of China’s Empire

- ^ George Ginsburgs (1983). The citizenship law of the USSR. p. 309. ISBN 9024728630

- ^ Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2. p. 51/52

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978023113924 -3. p. 306

- ^ a b Toops, Stanley (2004). "Demographics and Development in Xinjiang after 1949" (PDF). East-West Center Washington Working Papers (1). East–West Center: 1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978023113924 -3. p. 104

- ^ a b Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978023113924 -3. p. 105

- ^ Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2. p52

- ^ Mesny (1896), p. 272.

- ^ Mesny (1899), p. 485.

- ^ "China: Human Rights Concerns in Xinjiang". Human Rights Watch Backgrounder. Human Rights Watch. 2001. Retrieved 11 0 4 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dateformat=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Starr, S. Frederick (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- ^ "Regions and territories: Xinjiang". BBC News. May 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司) and Department of Economic Development of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of China (国家民族事务委员会经济发展司), eds. Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》). 2 vols. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003. (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

- ^ 新疆公布第六次人口普查数据:全区常住人口2181万 - 新疆天山网. Tianshannet.com (2011-05-06). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ "News Media for Ethnic Minorities in China". Xinhua News. October 25, 1995. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Hathaway, Tim (November 9, 2007). "A journalist in China: Tim Hathaway writes about his experience reporting and writing for state-run 'Xinjiang Economic Daily'". AsiaMedia. UCLA Asia Institute. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ Grammaticas, Damian (February 11, 2010). "Trekking 1,000km in China for e-mail". BBC News. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "新疆互联网业务全面恢复 (Xinjiang internet service completely restored)". Tianshan Net (in Chinese). May 14, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ^ "新疆"7-5"事件后全面恢复互联网业务 (After the 'July 5' riots, Xinjiang completely restores Internet service". news.163.com (in Chinese). May 14, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ^ Summers, Josh (May 14, 2010). "Xinjiang Internet restored after 10 months". FarWestChina blog. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ^ Deaths From Clashes in China’s Xinjiang Area Rises to 35. Bloomberg. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ The Uyghurs in Xinjiang – The Malaise Grows. Chinaperspectives.revues.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ Uyghur of China Ethnic People Profile. Joshuaproject.net (2013-04-09). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ [2] The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur identity, Language, Policy, and Political discourse

- ^ [3] Uyghur Separatist conflict

- ^ History and Development of Xinjiang. News.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

References

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. 2005. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8, ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk.)

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hierman, Brent. "The Pacification of Xinjiang: Uighur Protest and the Chinese State, 1988–2002." Problems of Post-Communism, May/Jun2007, Vol. 54 Issue 3, pp 48–62.

- Kim, Hodong, Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877 (Stanford, Stanford UP, 2004).

- Mesny, William (1896) Mesny's Chinese Miscellany. Vol. II. William Mesny. Shanghai.

- Mesny, William (1899) Mesny's Chinese Miscellany. Vol. III. William Mesny. Shanghai.

- Mesny, William (1905) Mesny's Chinese Miscellany. Vol. IV. William Mesny. Shanghai.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978023113924 . (European and Asian edition, London: Hurst, Co., 2007).

- Tyler, Christian. (2003). Wild West China: The Untold Story of a Frontier Land. John Murray, London. ISBN 0-7195-6341-0.

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). ``Wars With The Xiongnu – A translation From Zizhi Tongjian`` AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4

External links

- Xinjiang Government websiteTemplate:Zh icon and [4]Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead.

- Economic profile for Xinjiang at HKTDC

- "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" Li et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:15. [5]

- Britannica Xinjiang