NASA

Seal | |

| |

Flag | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 29, 1958 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Type | Governmental space agency |

| Jurisdiction | US Federal Government |

| Headquarters | Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C., United States 38°52′59″N 77°0′59″W / 38.88306°N 77.01639°W |

| Motto | For the Benefit of All[2] |

| Jim Bridenstine | |

| Deputy Administrator | James Morhard |

| Primary spaceports | |

| Employees | 17,373 (2020)[3] |

| Annual budget | |

| Website | NASA.gov |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA; /ˈnæsə/) is an independent agency of the United States Federal Government responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and space research.[note 1]

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). The new agency was to have a distinctly civilian orientation, encouraging peaceful applications in space science.[8][9][10] Since its establishment, most US space exploration efforts have been led by NASA, including the Apollo Moon landing missions, the Skylab space station, and later the Space Shuttle. NASA is supporting the International Space Station and is overseeing the development of the Orion spacecraft, the Space Launch System, and Commercial Crew vehicles. The agency is also responsible for the Launch Services Program, which provides oversight of launch operations and countdown management for uncrewed NASA launches.

NASA science is focused on better understanding Earth through the Earth Observing System;[11] advancing heliophysics through the efforts of the Science Mission Directorate's Heliophysics Research Program;[12] exploring bodies throughout the Solar System with advanced robotic spacecraft such as New Horizons;[13] and researching astrophysics topics, such as the Big Bang, through the Great Observatories and associated programs.[14]

Creation

From 1946, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) had been experimenting with rocket planes such as the supersonic Bell X-1.[15] In the early 1950s, there was challenge to launch an artificial satellite for the International Geophysical Year (1957–58). An effort for this was the American Project Vanguard. After the Soviet space program's launch of the world's first artificial satellite (Sputnik 1) on October 4, 1957, the attention of the United States turned toward its own fledgling space efforts. The U.S. Congress, alarmed by the perceived threat to national security and technological leadership (known as the "Sputnik crisis"), urged immediate and swift action; President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his advisers counseled more deliberate measures. On January 12, 1958, NACA organized a "Special Committee on Space Technology", headed by Guyford Stever.[10] On January 14, 1958, NACA Director Hugh Dryden published "A National Research Program for Space Technology" stating:[16]

It is of great urgency and importance to our country both from consideration of our prestige as a nation as well as military necessity that this challenge [Sputnik] be met by an energetic program of research and development for the conquest of space ... It is accordingly proposed that the scientific research be the responsibility of a national civilian agency ... NACA is capable, by rapid extension and expansion of its effort, of providing leadership in space technology.[16]

While this new federal agency would conduct all non-military space activity, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) was created in February 1958 to develop space technology for military application.[17]

On July 29, 1958, Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, establishing NASA. When it began operations on October 1, 1958, NASA absorbed the 43-year-old NACA intact; its 8,000 employees, an annual budget of US$100 million, three major research laboratories (Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, and Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory) and two small test facilities.[18] Elements of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and the United States Naval Research Laboratory were incorporated into NASA. A significant contributor to NASA's entry into the Space Race with the Soviet Union was the technology from the German rocket program led by Wernher von Braun, who was now working for the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), which in turn incorporated the technology of American scientist Robert Goddard's earlier works.[19] Earlier research efforts within the US Air Force[18] and many of ARPA's early space programs were also transferred to NASA.[20] In December 1958, NASA gained control of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a contractor facility operated by the California Institute of Technology.[18]

Goals

Since 2011, NASA's strategic goals have been[21]

- Extend and sustain human activities across the solar system

- Expand scientific understanding of the Earth and the universe

- Create innovative new space technologies

- Advance aeronautics research

- Enable program and institutional capabilities to conduct NASA's aeronautics and space activities

- Share NASA with the public, educators, and students to provide opportunities to participate

Spaceflight programs

NASA has conducted many uncrewed and crewed spaceflight programs throughout its history. Uncrewed programs launched the first American artificial satellites into Earth orbit for scientific and communications purposes, and sent scientific probes to explore the planets of the solar system, starting with Venus and Mars, and including "grand tours" of the outer planets. Crewed programs sent the first Americans into low Earth orbit (LEO), won the Space Race with the Soviet Union by landing twelve men on the Moon from 1969 to 1972 in the Apollo program, developed a semi-reusable LEO Space Shuttle, and developed LEO space station capability by itself and with the cooperation of several other nations including post-Soviet Russia.

Uncrewed

More than 1,000 uncrewed missions have been designed to explore the Earth and the solar system.[22] Besides exploration, communication satellites have also been launched by NASA.[23] The spacecraft have been launched directly from Earth or from orbiting space shuttles, which could either deploy the satellite itself, or with a rocket stage to take it farther.

The first US uncrewed satellite was Explorer 1, which started as an ABMA/JPL project during the early part of the Space Race. It was launched in January 1958, two months after Sputnik. At the creation of NASA, the Explorer project was transferred to the agency and still continues to this day. Its missions have been focusing on the Earth and the Sun, measuring magnetic fields and the solar wind, among other aspects.[24] A more recent Earth satellite, not related to the Explorer program, was the Hubble Space Telescope, which was brought into orbit in 1990.[25]

The inner Solar System has been made the goal of at least four uncrewed programs. The first was Mariner in the 1960s and 1970s, which made multiple visits to Venus and Mars and one to Mercury. Probes launched under the Mariner program were also the first to make a planetary flyby (Mariner 2), to take the first pictures from another planet (Mariner 4), the first planetary orbiter (Mariner 9), and the first to make a gravity assist maneuver (Mariner 10). This is a technique where the satellite takes advantage of the gravity and velocity of planets to reach its destination.[26]

The first successful landing on Mars was made by Viking 1 in 1976. Twenty years later a rover was landed on Mars by Mars Pathfinder.[27]

Outside Mars, Jupiter was first visited by Pioneer 10 in 1973. More than 20 years later Galileo sent a probe into the planet's atmosphere, and became the first spacecraft to orbit the planet.[28] Pioneer 11 became the first spacecraft to visit Saturn in 1979, with Voyager 2 making the first (and so far only) visits to Uranus and Neptune in 1986 and 1989, respectively. The first spacecraft to leave the solar system was Pioneer 10 in 1983. For a time it was the most distant spacecraft, but it has since been surpassed by both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.[29]

Pioneers 10 and 11 and both Voyager probes carry messages from the Earth to extraterrestrial life.[30][31] Communication can be difficult with deep space travel. For instance, it took about three hours for a radio signal to reach the New Horizons spacecraft when it was more than halfway to Pluto.[32] Contact with Pioneer 10 was lost in 2003. Both Voyager probes continue to operate as they explore the outer boundary between the Solar System and interstellar space.[33]

The New Horizons mission to Pluto was launched in 2006 and successfully performed a flyby of Pluto on July 14, 2015. The probe received a gravity assist from Jupiter in February 2007, examining some of Jupiter's inner moons and testing on-board instruments during the flyby. On the horizon of NASA's plans is the MAVEN spacecraft as part of the Mars Scout Program to study the atmosphere of Mars.[34]

Other active spacecraft are Juno for Jupiter, New Horizons (for Jupiter, Pluto, and beyond), and Dawn for the asteroid belt. NASA continued to support in situ exploration beyond the asteroid belt, including Pioneer and Voyager traverses into the unexplored trans-Pluto region, and Gas Giant orbiters Galileo (1989–2003), Cassini (1997–2017), and Juno (2011–present).

Hubble Space Telescope (1968–present)

The Hubble Space Telescope (often referred to as HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most versatile, renowned as a vital research tool and as a public relations boon for astronomy. The Hubble telescope is named after astronomer Edwin Hubble and is one of NASA's Great Observatories. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) selects Hubble's targets and processes the resulting data, while the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) controls the spacecraft.[35]

Hubble features a 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) mirror, and its five main instruments observe in the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Hubble's orbit outside the distortion of Earth's atmosphere allows it to capture extremely high-resolution images with substantially lower background light than ground-based telescopes. It has recorded some of the most detailed visible light images, allowing a deep view into space. Many Hubble observations have led to breakthroughs in astrophysics, such as determining the rate of expansion of the universe.

Space telescopes were proposed as early as 1923, and the Hubble telescope was funded and built in the 1970s by the United States space agency NASA with contributions from the European Space Agency. Its intended launch was in 1983, but the project was beset by technical delays, budget problems, and the 1986 Challenger disaster. Hubble was finally launched in 1990, but its main mirror had been ground incorrectly, resulting in spherical aberration that compromised the telescope's capabilities. The optics were corrected to their intended quality by a servicing mission in 1993.

Hubble is the only telescope designed to be maintained in space by astronauts. Five Space Shuttle missions have repaired, upgraded, and replaced systems on the telescope, including all five of the main instruments. The fifth mission was initially canceled on safety grounds following the Columbia disaster (2003), but after NASA administrator Michael D. Griffin approved it, the servicing mission was completed in 2009. Hubble completed 30 years of operation in April 2020[36] and is predicted to last until 2030 to 2040.[37]

Hubble is the visible light telescope in NASA's Great Observatories program; other parts of the spectrum are covered by the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Spitzer Space Telescope (which covers the infrared bands).[38]

The mid-IR-to-visible band successor to the Hubble telescope is the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which was launched on December 25, 2021, with the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope due to follow in 2027.[39][40][41]New Horizons (2000–present)

New Horizons is an interplanetary space probe launched as a part of NASA's New Frontiers program.[42] Engineered by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), with a team led by Alan Stern,[43] the spacecraft was launched in 2006 with the primary mission to perform a flyby study of the Pluto system in 2015, and a secondary mission to fly by and study one or more other Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) in the decade to follow, which became a mission to 486958 Arrokoth. It is the fifth space probe to achieve the escape velocity needed to leave the Solar System.

On January 19, 2006, New Horizons was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station by an Atlas V rocket directly into an Earth-and-solar escape trajectory with a speed of about 16.26 km/s (10.10 mi/s; 58,500 km/h; 36,400 mph). It was the fastest (average speed with respect to Earth) human-made object ever launched from Earth.[44][45][46][47] It is not the fastest speed recorded for a spacecraft, which, as of 2023, is that of the Parker Solar Probe. After a brief encounter with asteroid 132524 APL, New Horizons proceeded to Jupiter, making its closest approach on February 28, 2007, at a distance of 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles). The Jupiter flyby provided a gravity assist that increased New Horizons' speed; the flyby also enabled a general test of New Horizons' scientific capabilities, returning data about the planet's atmosphere, moons, and magnetosphere.

Most of the post-Jupiter voyage was spent in hibernation mode to preserve onboard systems, except for brief annual checkouts.[48] On December 6, 2014, New Horizons was brought back online for the Pluto encounter, and instrument check-out began.[49] On January 15, 2015, the spacecraft began its approach phase to Pluto.

On July 14, 2015, at 11:49 UTC, it flew 12,500 km (7,800 mi) above the surface of Pluto,[50][51] which at the time was 34 AU from the Sun,[52] making it the first spacecraft to explore the dwarf planet.[53] In August 2016, New Horizons was reported to have traveled at speeds of more than 84,000 km/h (52,000 mph).[54] On October 25, 2016, at 21:48 UTC, the last recorded data from the Pluto flyby was received from New Horizons.[55] Having completed its flyby of Pluto,[56] New Horizons then maneuvered for a flyby of Kuiper belt object 486958 Arrokoth (then nicknamed Ultima Thule),[57][58][59] which occurred on January 1, 2019,[60][61] when it was 43.4 AU (6.49 billion km; 4.03 billion mi) from the Sun.[57][58] In August 2018, NASA cited results by Alice on New Horizons to confirm the existence of a "hydrogen wall" at the outer edges of the Solar System. This "wall" was first detected in 1992 by the two Voyager spacecraft.[62][63]

New Horizons is traveling through the Kuiper belt; it is 59.8 AU (8.95 billion km; 5.56 billion mi) from Earth and 60.0 AU (8.98 billion km; 5.58 billion mi) from the Sun as of October 2024.[64] NASA has announced it is to extend operations for New Horizons until the spacecraft exits the Kuiper belt, which is expected to occur between 2028 and 2029.[65]

Mars Science Laboratory (2003–present)

Commercial Resupply Services (2006–present)

The development of the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) vehicles began in 2006 with the purpose of creating American commercially operated uncrewed cargo vehicles to service the ISS.[73] The development of these vehicles was under a fixed-price, milestone-based program, meaning that each company that received a funded award had a list of milestones with a dollar value attached to them that they did not receive until after they had successfully completed the milestone.[74] Companies were also required to raise an unspecified amount of private investment for their proposal.[75]

On December 23, 2008, NASA awarded Commercial Resupply Services contracts to SpaceX and Orbital Sciences Corporation.[76] SpaceX uses its Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft.[77] Orbital Sciences uses its Antares rocket and Cygnus spacecraft. The first Dragon resupply mission occurred in May 2012.[78] The first Cygnus resupply mission occurred in September 2013.[79] The CRS program now provides for all America's ISS cargo needs, with the exception of a few vehicle-specific payloads that are delivered on the European ATV and the Japanese HTV.[80]

Crewed

The experimental rocket-powered aircraft programs started by NACA were extended by NASA as support for crewed spaceflight. This was followed by a one-man space capsule program, and in turn by a two-man capsule program. Reacting to loss of national prestige and security fears caused by early leads in space exploration by the Soviet Union, in 1961 President John F. Kennedy proposed the ambitious goal "of landing a man on the Moon by the end of [the 1960s], and returning him safely to the Earth." This goal was met in 1969 by the Apollo program, and NASA planned even more ambitious activities leading to a human mission to Mars. However, reduction of the perceived threat and changing political priorities almost immediately caused the termination of most of these plans. NASA turned its attention to an Apollo-derived temporary space laboratory and a semi-reusable Earth orbital shuttle. In the 1990s, funding was approved for NASA to develop a permanent Earth orbital space station in cooperation with the international community, which now included the former rival, post-Soviet Russia.[82] To date, NASA has launched a total of 166 crewed space missions on rockets, and thirteen X-15 rocket flights above the USAF definition of spaceflight altitude, 260,000 feet (80 km).[83]

X-15 program (1954–1968)

The North American X-15 was an NACA experimental rocket-powered hypersonic research aircraft, developed in conjunction with the US Air Force and Navy. The design featured a slender fuselage with fairings along the side containing fuel and early computerized control systems.[84] Requests for proposal were issued on December 30, 1954, for the airframe, and February 4, 1955, for the rocket engine. The airframe contract was awarded to North American Aviation in November 1955, and the XLR30 engine contract was awarded to Reaction Motors in 1956, and three planes were built. The X-15 was drop-launched from the wing of one of two NASA Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses, NB52A tail number 52-003, and NB52B, tail number 52-008 (known as the Balls 8). Release took place at an altitude of about 45,000 feet (14 km) and a speed of about 500 miles per hour (805 km/h).[citation needed]

Twelve pilots were selected for the program from the Air Force, Navy, and NACA (later NASA). A total of 199 flights were made between 1959 and 1968, resulting in the official world record for the highest speed ever reached by a crewed powered aircraft (current as of 2014[update]), and a maximum speed of Mach 6.72, 4,519 miles per hour (7,273 km/h).[85] The altitude record for X-15 was 354,200 feet (107.96 km).[86] Eight of the pilots were awarded Air Force astronaut wings for flying above 260,000 feet (80 km), and two flights by Joseph A. Walker exceeded 100 kilometers (330,000 ft), qualifying as spaceflight according to the International Aeronautical Federation. The X-15 program employed mechanical techniques used in the later crewed spaceflight programs, including reaction control system jets for controlling the orientation of a spacecraft, space suits, and horizon definition for navigation.[86] The reentry and landing data collected were valuable to NASA for designing the Space Shuttle.[84]

Project Mercury (1958–1963)

Shortly after the Space Race began, an early objective was to get a person into Earth orbit as soon as possible, therefore the simplest spacecraft that could be launched by existing rockets was favored. The US Air Force's Man in Space Soonest program considered many crewed spacecraft designs, ranging from rocket planes like the X-15, to small ballistic space capsules.[87] By 1958, the space plane concepts were eliminated in favor of the ballistic capsule.[88]

When NASA was created that same year, the Air Force program was transferred to it and renamed Project Mercury. The first seven astronauts were selected among candidates from the Navy, Air Force and Marine test pilot programs. On May 5, 1961, astronaut Alan Shepard became the first American in space aboard Freedom 7, launched by a Redstone booster on a 15-minute ballistic (suborbital) flight.[89] John Glenn became the first American to be launched into orbit, by an Atlas launch vehicle on February 20, 1962, aboard Friendship 7.[90] Glenn completed three orbits, after which three more orbital flights were made, culminating in L. Gordon Cooper's 22-orbit flight Faith 7, May 15–16, 1963.[91] Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan were three of the human computers doing calculations on trajectories during the Space Race.[92][93][94] Johnson was well known for doing trajectory calculations for John Glenn's mission in 1962, where she was running the same equations by hand that were being run on the computer.[92]

The Soviet Union (USSR) competed with its own single-pilot spacecraft, Vostok. They sent the first man in space, by launching cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into a single Earth orbit aboard Vostok 1 in April 1961, one month before Shepard's flight.[95] In August 1962, they achieved an almost four-day record flight with Andriyan Nikolayev aboard Vostok 3, and also conducted a concurrent Vostok 4 mission carrying Pavel Popovich.

Project Gemini (1961–1966)

Based on studies to grow the Mercury spacecraft capabilities to long-duration flights, developing space rendezvous techniques, and precision Earth landing, Project Gemini was started as a two-man program in 1962 to overcome the Soviets' lead and to support the Apollo crewed lunar landing program, adding extravehicular activity (EVA) and rendezvous and docking to its objectives. The first crewed Gemini flight, Gemini 3, was flown by Gus Grissom and John Young on March 23, 1965.[96] Nine missions followed in 1965 and 1966, demonstrating an endurance mission of nearly fourteen days, rendezvous, docking, and practical EVA, and gathering medical data on the effects of weightlessness on humans.[97][98]

Under the direction of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, the USSR competed with Gemini by converting their Vostok spacecraft into a two- or three-man Voskhod. They succeeded in launching two crewed flights before Gemini's first flight, achieving a three-cosmonaut flight in 1964 and the first EVA in 1965. After this, the program was canceled, and Gemini caught up while spacecraft designer Sergei Korolev developed the Soyuz spacecraft, their answer to Apollo.

Apollo program (1961–1972)

The U.S public's perception of the Soviet lead in the Space Race (by putting the first man into space) motivated President John F. Kennedy[99] to ask the Congress on May 25, 1961, to commit the federal government to a program to land a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s, which effectively launched the Apollo program.[100]

Apollo was one of the most expensive American scientific programs ever. It cost more than $20 billion in 1960s dollars[101] or an estimated $265 billion in present-day US dollars.[102] (In comparison, the Manhattan Project cost roughly $33.8 billion, accounting for inflation.)[102][103] It used the Saturn rockets as launch vehicles, which were far bigger than the rockets built for previous projects.[104] The spacecraft was also bigger; it had two main parts, the combined command and service module (CSM) and the Apollo Lunar Module (LM). The LM was to be left on the Moon and only the command module (CM) containing the three astronauts would return to Earth.[note 2]

The second crewed mission, Apollo 8, brought astronauts for the first time in a flight around the Moon in December 1968.[105] Shortly before, the Soviets had sent an uncrewed spacecraft around the Moon.[106] On the next two missions docking maneuvers that were needed for the Moon landing were practiced[107][108] and then finally the Moon landing was made on the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969.[109]

The first person to walk on the Moon was Neil Armstrong, who was followed 19 minutes later by Buzz Aldrin, while Michael Collins orbited above. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. Throughout these six Apollo spaceflights, twelve men walked on the Moon. These missions returned a wealth of scientific data and 381.7 kilograms (842 lb) of lunar samples. Topics covered by experiments performed included soil mechanics, meteoroids, seismology, heat flow, lunar ranging, magnetic fields, and solar wind.[110][page needed] The Moon landing marked the end of the space race; and as a gesture, Armstrong mentioned mankind when he stepped down on the Moon.[111]

Apollo set major milestones in human spaceflight. It stands alone in sending crewed missions beyond low Earth orbit, and landing humans on another celestial body.[112] Apollo 8 was the first crewed spacecraft to orbit another celestial body, while Apollo 17 marked the last moonwalk and the last crewed mission beyond low Earth orbit. The program spurred advances in many areas of technology peripheral to rocketry and crewed spaceflight, including avionics, telecommunications, and computers. Apollo sparked interest in many fields of engineering and left many physical facilities and machines developed for the program as landmarks. Many objects and artifacts from the program are on display at various locations throughout the world, notably at the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museums.

Skylab (1965–1979)

| Mission |

|

|---|---|

| Skylab 2 | |

| Skylab 3 | |

| Skylab 4 |

Skylab was the United States' first and only independently built space station.[113] Conceived in 1965 as a workshop to be constructed in space from a spent Saturn IB upper stage, the 169,950 lb (77,088 kg) station was constructed on Earth and launched on May 14, 1973, atop the first two stages of a Saturn V, into a 235-nautical-mile (435 km) orbit inclined at 50° to the equator. Damaged during launch by the loss of its thermal protection and one electricity-generating solar panel, it was repaired to functionality by its first crew. It was occupied for a total of 171 days by 3 successive crews in 1973 and 1974.[113] It included a laboratory for studying the effects of microgravity, and a solar observatory.[113] NASA planned to have a Space Shuttle dock with it, and elevate Skylab to a higher safe altitude, but the Shuttle was not ready for flight before Skylab's re-entry on July 11, 1979.[114]

To save cost, NASA used one of the Saturn V rockets originally earmarked for a canceled Apollo mission to launch the Skylab. Apollo spacecraft were used for transporting astronauts to and from the station. Three three-man crews stayed aboard the station for periods of 28, 59, and 84 days. Skylab's habitable volume was 11,290 cubic feet (320 m3), which was 30.7 times bigger than that of the Apollo Command Module.[114]

Apollo-Soyuz (1972–1975)

On May 24, 1972, US President Richard M. Nixon and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement calling for a joint crewed space mission, and declaring intent for all future international crewed spacecraft to be capable of docking with each other.[115] This authorized the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), involving the rendezvous and docking in Earth orbit of a surplus Apollo command and service module with a Soyuz spacecraft. The mission took place in July 1975. This was the last US human spaceflight until the first orbital flight of the Space Shuttle in April 1981.[116]

The mission included both joint and separate scientific experiments and provided useful engineering experience for future joint US–Russian space flights, such as the Shuttle–Mir program[117] and the International Space Station.

Space Shuttle program (1972–2011)

The Space Shuttle became the major focus of NASA in the late 1970s and the 1980s. Planned as a frequently launchable and mostly reusable vehicle, four Space Shuttle orbiters were built by 1985. The first to launch, Columbia, did so on April 12, 1981, the 20th anniversary of the first known human spaceflight.[118]

Its major components were a spaceplane orbiter with an external fuel tank and two solid-fuel launch rockets at its side. The external tank, which was bigger than the spacecraft itself, was the only major component that was not reused. The shuttle could orbit in altitudes of 185–643 km (115–400 miles)[119] and carry a maximum payload (to low orbit) of 24,400 kg (54,000 lb).[120] Missions could last from 5 to 17 days and crews could be from 2 to 8 astronauts.[119]

On 20 missions (1983–1998) the Space Shuttle carried Spacelab, designed in cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA). Spacelab was not designed for independent orbital flight, but remained in the Shuttle's cargo bay as the astronauts entered and left it through an airlock.[121] On June 18, 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman in space, on board the Space Shuttle Challenger STS-7 mission.[122] Another famous series of missions were the launch and later successful repair of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990 and 1993, respectively.[123]

In 1995, Russian-American interaction resumed with the Shuttle–Mir missions (1995–1998). Once more an American vehicle docked with a Russian craft, this time a full-fledged space station. This cooperation has continued with Russia and the United States as two of the biggest partners in the largest space station built: the International Space Station (ISS). The strength of their cooperation on this project was even more evident when NASA began relying on Russian launch vehicles to service the ISS during the two-year grounding of the shuttle fleet following the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

The Shuttle fleet lost two orbiters and 14 astronauts in two disasters: Challenger in 1986, and Columbia in 2003.[124] While the 1986 loss was mitigated by building the Space Shuttle Endeavour from replacement parts, NASA did not build another orbiter to replace the second loss.[124] NASA's Space Shuttle program had 135 missions when the program ended with the successful landing of the Space Shuttle Atlantis at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011. The program spanned 30 years with over 300 astronauts sent into space.[125]

International Space Station (1993–present)

The International Space Station (ISS) combines NASA's Space Station Freedom project with the Soviet/Russian Mir-2 station, the European Columbus station, and the Japanese Kibō laboratory module.[126][page needed] NASA originally planned in the 1980s to develop Freedom alone, but US budget constraints led to the merger of these projects into a single multi-national program in 1993, managed by NASA, the Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[127][128] The station consists of pressurized modules, external trusses, solar arrays and other components, which were manufactured in various factories around the world, and have been launched by Russian Proton and Soyuz rockets, and the US Space Shuttles.[126][page needed] The on-orbit assembly began in 1998, the completion of the US Orbital Segment occurred in 2019 and the completion of the Russian Orbital Segment occurred in 2010, though there are some debates of whether new modules should be added in the segment. The ownership and use of the space station is established in intergovernmental treaties and agreements[129] which divide the station into two areas and allow Russia to retain full ownership of the Russian Orbital Segment (with the exception of Zarya),[130][131] with the US Orbital Segment allocated between the other international partners.[129]

Long-duration missions to the ISS are referred to as ISS Expeditions. Expedition crew members typically spend approximately six months on the ISS.[132] The initial expedition crew size was three, temporarily decreased to two following the Columbia disaster. Since May 2009, expedition crew size has been six crew members.[133] Crew size is expected to be increased to seven, the number the ISS was designed for, once the Commercial Crew Program becomes operational.[134] The ISS has been continuously occupied for the past 24 years and 7 days, having exceeded the previous record held by Mir; and has been visited by astronauts and cosmonauts from 15 different nations.[135][136]

The station can be seen from the Earth with the naked eye and, as of 2024, is the largest artificial satellite in Earth orbit with a mass and volume greater than that of any previous space station.[137] The Soyuz spacecraft delivers crew members, stays docked for their half-year-long missions and then returns them home. Several uncrewed cargo spacecraft service the ISS; they are the Russian Progress spacecraft which has done so since 2000, the European Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) since 2008, the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) since 2009, the SpaceX Dragon from 2012 until 2020, and the American Cygnus spacecraft since 2013. The Space Shuttle, before its retirement, was also used for cargo transfer and would often switch out expedition crew members, although it did not have the capability to remain docked for the duration of their stay. Until another US crewed spacecraft is ready, crew members will travel to and from the International Space Station exclusively aboard the Soyuz.[138] The highest number of people occupying the ISS has been thirteen; this occurred three times during the late Shuttle ISS assembly missions.[139]

On March 29, 2019, the ISS had its first all-female spacewalk; Anne McClain and Christina Koch will take flight during Women's History Month.[140] The ISS program is expected to continue to 2030.[141]

Constellation program (2005–2010)

While the Space Shuttle program was still suspended after the loss of Columbia, President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration including the retirement of the Space Shuttle after completing the International Space Station. The plan was enacted into law by the NASA Authorization Act of 2005 and directs NASA to develop and launch the Crew Exploration Vehicle (later called Orion) by 2010, return Americans to the Moon by 2020, return to Mars as feasible, repair the Hubble Space Telescope, and continue scientific investigation through robotic solar system exploration, human presence on the ISS, Earth observation, and astrophysics research. The crewed exploration goals prompted NASA's Constellation program.[citation needed]

On December 4, 2006, NASA announced it was planning a permanent Moon base.[142] The goal was to start building the Moon base by 2020, and by 2024, have a fully functional base that would allow for crew rotations and in-situ resource utilization. However, in 2009, the Augustine Committee found the program to be on an "unsustainable trajectory."[143] In February 2010, President Barack Obama's administration proposed eliminating public funds for it.[144]

Commercial Crew Program (2011–present)

The Commercial Crew Program (CCP) provides commercially operated crew transportation service to and from the International Space Station (ISS) under contract to NASA, conducting crew rotations between the expeditions of the International Space Station program. American space manufacturer SpaceX began providing service in 2020, using the Crew Dragon spacecraft, and NASA plans to add Boeing when its Boeing Starliner spacecraft becomes operational no earlier than 2025.[145] NASA has contracted for six operational missions from Boeing and fourteen from SpaceX, ensuring sufficient support for ISS through 2030.[146]

The spacecraft are owned and operated by the vendor, and crew transportation is provided to NASA as a commercial service. Each mission sends up to four astronauts to the ISS. Operational flights occur approximately once every six months for missions that last for approximately six months. A spacecraft remains docked to the ISS during its mission, and missions usually overlap by at least a few days. Between the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011 and the first operational CCP mission in 2020, NASA relied on the Soyuz program to transport its astronauts to the ISS.

A Crew Dragon spacecraft is launched to space atop a Falcon 9 Block 5 launch vehicle and the capsule returns to Earth via splashdown in the ocean near Florida. The program's first operational mission, SpaceX Crew-1, launched on 16 November 2020. Boeing Starliner spacecraft will participate after its final test flight, launched atop an Atlas V N22 launch vehicle. Instead of a splashdown, a Starliner capsule will return on land with airbags at one of four designated sites in the western United States.

Development of the Commercial Crew Program began in 2011 as NASA shifted from internal development of crewed vehicles to perform ISS crew rotation to commercial industry development of transport to the ISS. A series of open competitions over the following two years saw successful bids from Boeing, Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX to develop proposals for ISS crew transport vehicles. In 2014, NASA awarded separate fixed-price contracts to Boeing and SpaceX to develop their respective systems and to fly astronauts to the ISS. Each contract required four successful demonstrations to achieve human rating for the system: pad abort, uncrewed orbital test, launch abort, and crewed orbital test. Operational missions were initially planned to begin in 2017, with missions alternating between the two providers. Delays required NASA to purchase additional seats on Soyuz spacecraft up to Soyuz MS-17 until Crew Dragon missions commenced in 2020. Crew Dragon continues to handle all missions until Starliner becomes operational no earlier than 2025.[145]Journey to Mars (2010–2017)

President Obama's plan was to develop American private spaceflight capabilities to get astronauts to the International Space Station, replacing Russian Soyuz capsules, and to use Orion capsules for ISS emergency escape purposes. During a speech at the Kennedy Space Center on April 15, 2010, Obama proposed a new heavy-lift vehicle (HLV) to replace the formerly planned Ares V.[147] In his speech, Obama called for a crewed mission to an asteroid as soon as 2025, and a crewed mission to Mars orbit by the mid-2030s.[147] The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 was passed by Congress and signed into law on October 11, 2010.[148] The act officially canceled the Constellation program.[148]

The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 required a newly designed HLV be chosen within 90 days of its passing; the launch vehicle was given the name Space Launch System. The new law also required the construction of a beyond low earth orbit spacecraft.[149] The Orion spacecraft, which was being developed as part of the Constellation program, was chosen to fulfill this role.[150] The Space Launch System is planned to launch both Orion and other necessary hardware for missions beyond low Earth orbit.[151] The SLS is to be upgraded over time with more powerful versions. The initial capability of SLS is required to be able to lift 70 t (150,000 lb) (later 95 t or 209,000 lb) into LEO. It is then planned to be upgraded to 105 t (231,000 lb) and then eventually to 130 t (290,000 lb).[150][152] The Orion capsule first flew on Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1), an uncrewed test flight that was launched on December 5, 2014, atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket.[152]

NASA undertook a feasibility study in 2012 and developed the Asteroid Redirect Mission as an uncrewed mission to move a boulder-sized near-Earth asteroid (or boulder-sized chunk of a larger asteroid) into lunar orbit. The mission would demonstrate ion thruster technology, and develop techniques that could be used for planetary defense against an asteroid collision, as well as cargo transport to Mars in support of a future human mission. The Moon-orbiting boulder might then later be visited by astronauts. The Asteroid Redirect Mission was cancelled in 2017 as part of the FY2018 NASA budget, the first one under President Donald Trump.[citation needed]

The Orion spacecraft conducted an uncrewed test launch on a Delta IV Heavy rocket in December 2014.[153]

Artemis program (2017–present)

Since 2017, NASA's crewed spaceflight program has been the Artemis program, which involves the help of U.S. commercial spaceflight companies and international partners such as ESA.[154] The goal of this program is to land "the first woman and the next man" on the lunar south pole region by 2024. Artemis would be the first step towards the long-term goal of establishing a sustainable presence on the Moon, laying the foundation for private companies to build a lunar economy, and eventually sending humans to Mars.

The Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle was held over from the canceled Constellation program for Artemis. Artemis 1 is the uncrewed initial launch of SLS that would also send an Orion spacecraft on a Distant Retrograde Orbit, which is planned to launch no earlier than November 2020.[155]

NASA's next major space initiative is to be the construction of the Lunar Gateway. This initiative is to involve the construction of a new space station, which will have many features in common with the current International Space Station, except that it will be in orbit about the Moon, instead of the Earth.[156] This space station will be designed primarily for non-continuous human habitation. The first tentative steps of returning to crewed lunar missions will be Artemis 2, which is to include the Orion crew module, propelled by the SLS, and is to launch in 2022.[154] This mission is to be a 10-day mission planned to briefly place a crew of four into a Lunar flyby.[152] The construction of the Gateway would begin with the proposed Artemis 3, which is planned to deliver a crew of four to Lunar orbit along with the first modules of the Gateway. This mission would last for up to 30 days. NASA plans to build full scale deep space habitats such as the Lunar Gateway and the Nautilus-X as part of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) program.[157] In 2017, NASA was directed by the congressional NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017 to get humans to Mars-orbit (or to the Martian surface) by the 2030s.[158][159]

NEO detection

In 1994, there was a Congressional directive to find near-Earth objects (NEOs) larger than 1 kilometer, and 90% of 1 kilometer sized asteroids are estimated to have been found by 2010.[160]

In 1999 NASA visited 433 Eros with the NEAR spacecraft which entered its orbit in 2000, closely imaging the asteroid with various instruments at that time.[161] From the 1990s NASA has run many NEO detection programs from Earth bases observatories, greatly increasing the number of objects that have been detected. However, many asteroids are very dark and the ones that are near the Sun are much harder to detect from Earth-based telescopes which observe at night, and thus face away from the Sun. NEOs inside Earth orbit only reflect a part of light also rather than potentially a "full Moon" when they are behind the Earth and fully lit by the Sun.

In 2005, the US Congress mandated NASA to achieve by the year 2020 specific levels of search completeness for discovering, cataloging, and characterizing dangerous asteroids larger than 140 meters (460 ft) (Act of 2005, H.R. 1022; 109th),[162] but no new funds were appropriated for this effort.[163] As of January 2019, it is estimated about 40% of the NEOs of this size have been found, although since by its nature the exact amount of NEOs are unknown the calculations are based on predictions of how many there could be.[164]

One issue with NEO prediction is trying to estimate how many more are likely to be found In 2000, NASA reduced its estimate of the number of existing near-Earth asteroids over one kilometer in diameter from 1,000–2,000 to 500–1,000.[165][166] Shortly thereafter, the LINEAR survey provided an alternative estimate of 1,227+170

−90.[167] In 2011, on the basis of NEOWISE observations, the estimated number of one-kilometer NEAs was narrowed to 981±19 (of which 93% had been discovered at the time), while the number of NEAs larger than 140 meters across was estimated at 13,200±1,900.[168][169] The NEOWISE estimate differed from other estimates in assuming a slightly lower average asteroid albedo, which produces larger estimated diameters for the same asteroid brightness. This resulted in 911 then known asteroids at least 1 km across, as opposed to the 830 then listed by CNEOS.[170] In 2017, using an improved statistical method, two studies reduced the estimated number of NEAs brighter than absolute magnitude 17.75 (approximately over one kilometer in diameter) to 921±20.[171][172] The estimated number of asteroids brighter than absolute magnitude of 22.0 (approximately over 140 m across) rose to 27,100±2,200, double the WISE estimate,[172] of which about a third are known as of 2018. A problem with estimating the number of NEOs is that detections are influenced by a number of factors.[173]

NASA turned the infrared space survey telescope WISE back on in 2013 to look for NEOs, and it found some during the course of its operation. NEOcam competed in the highly competitive Discovery program, which became more so due to a low mission rate in the 2010s.

Research

NASA's Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate conducts aeronautics research.

NASA has made use of technologies such as the multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG), which is a type of radioisotope thermoelectric generator used to power spacecraft.[175] Shortages of the required plutonium-238 have curtailed deep space missions since the turn of the millennium.[176] An example of a spacecraft that was not developed because of a shortage of this material was New Horizons 2.[176]

The Earth science research program was created and first funded in the 1980s under the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.[177][178]

NASA started an annual competition in 2014 named Cubes in Space.[179] It is jointly organized by NASA and the global education company I Doodle Learning, with the objective of teaching school students aged 11–18 to design and build scientific experiments to be launched into space on a NASA rocket or balloon. On June 21, 2017 the world's smallest satellite, Kalam SAT, built by an Indian team, was launched.[180]

Climate and other research

NASA also researches and publishes on climate change.[181] Its statements concur with the global scientific consensus that the global climate is warming.[182] Bob Walker, who has advised US President Donald Trump on space issues, has advocated that NASA should focus on space exploration and that its climate study operations should be transferred to other agencies such as NOAA. Former NASA atmospheric scientist J. Marshall Shepherd countered that Earth science study was built into NASA's mission at its creation in the 1958 National Aeronautics and Space Act.[183] NASA won the 2020 Webby People's Voice Award for Green in the category Web.[184]

NASA contracted a third party to study the probability of using Free Space Optics (FSO) to communicate with Optical (laser) Stations on the Ground (OGS) called laser-com RF networks for satellite communications.[185]

On July 29, 2020, NASA requested American universities to propose new technologies for extracting water from the lunar soil and developing power systems. The idea will help the space agency conduct sustainable exploration of the Moon.[186]

Other activities

NASA's ongoing investigations include in-depth surveys of Mars (Perseverance and InSight) and Saturn and studies of the Earth and the Sun. In August 2011, NASA accepted the donation of two space telescopes from the National Reconnaissance Office. Despite being stored unused, the instruments are superior to the Hubble Space Telescope.[187]

Environmental impact

The exhaust gases produced by rocket propulsion systems, both in Earth's atmosphere and in space, can adversely effect the Earth's environment. Some hypergolic rocket propellants, such as hydrazine, are highly toxic prior to combustion, but decompose into less toxic compounds after burning. Rockets using hydrocarbon fuels, such as kerosene, release carbon dioxide and soot in their exhaust.[188] However, carbon dioxide emissions are insignificant compared to those from other sources; on average, the United States consumed 802,620,000 US gallons (3.0382×109 L) of liquid fuels per day in 2014, while a single Falcon 9 rocket first stage burns around 25,000 US gallons (95,000 L) of kerosene fuel per launch.[189][190] Even if a Falcon 9 were launched every single day, it would only represent 0.006% of liquid fuel consumption (and carbon dioxide emissions) for that day. Additionally, the exhaust from LOx- and LH2- fueled engines, like the SSME, is almost entirely water vapor.[191] NASA addressed environmental concerns with its canceled Constellation program in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act in 2011.[192] In contrast, ion engines use harmless noble gases like xenon for propulsion.[193][194]

On May 8, 2003, Environmental Protection Agency recognized NASA as the first federal agency to directly use landfill gas to produce energy at one of its facilities—the Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland.[195]

An example of NASA's environmental efforts is the NASA Sustainability Base. Additionally, the Exploration Sciences Building was awarded the LEED Gold rating in 2010.[196]

In 2018, NASA along with other companies including Sensor Coating Systems, Pratt & Whitney, Monitor Coating and UTRC launched the project CAUTION (CoAtings for Ultra High Temperature detectION). This project aims to enhance the temperature range of the Thermal History Coating up to 1,500 °C (2,730 °F) and beyond. The final goal of this project is improving the safety of jet engines as well as increasing efficiency and reducing CO2 emissions.[197]

Response of the COVID-19 pandemic

NASA announced the temporary closure of all visitor complexes at its field centers until further notice and asked all non-critical personnel to work from home if possible. Production and manufacturing of the Space Launch System at the Michoud Assembly Facility was halted,[198][199] and further delays occurred for the James Webb Space Telescope,[200] although work resumed on June 3, 2020.[201]

The majority of Johnson Space Center personnel transitioned to telecommunicating, and mission-critical personnel on the International Space Station were ordered to reside in the mission control room until further notice. Station operations were relatively unaffected, but astronauts on new expeditions are subject to longer more stringent pre-flight quarantine.[202]

NASA's emergency response framework varied based on local virus cases around its agency's field centers. As of March 24, 2020, the following space centers had moved to Stage 4.[203]

Two facilities were maintained at Stage 4 after reporting new cases of coronavirus: the Michoud Assembly Facility reported its first employee to test positive for COVID-19, and Stennis Space Center recorded the second case of a NASA community member with the virus. Kennedy Space Center maintained at Stage 3 after a workforce member tested positive. Due to the mandatory remote work policy already in place, the individual had not been on-site for more than a week before the onset of symptoms.[204] On May 18, the Michoud facility began resuming work operations on the SLS, but so far remains in a Level 3 status.[205]

At Level 4, mandatory remote work is in effect for all personnel except for limited personnel required for mission-critical work and to ensure and maintain the safety and security of the facility.[206]Facilities

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC provides overall guidance and political leadership to the agency's ten field centers, through which all other facilities are administered. The ten field centers are:

- John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC) is one of the best-known NASA facilities. It has been the launch site for every U.S. human space flight since 1968. KSC manages and operates rocket launch facilities for America's civilian space program from three pads at the adjoining Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. NASA also operates a short-line railroad at KSC and uses special aircraft.

- Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas contains the Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center, where all flight control is managed for crewed space missions. JSC is the lead NASA center for activities regarding the International Space Station and also houses the NASA Astronaut Corps that selects, trains, and provides astronauts as crew members for US and international space missions.

- George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama is the rocket development center, at which the Saturn V rocket and Skylab were developed.[207]

- Ames Research Center (ARC) at Moffett Field, in California's Silicon Valley, was founded on December 20, 1939. The center was named after Joseph Sweetman Ames, a founding member of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA).

- Armstrong Flight Research Center (formerly Hugh L. Dryden Flight Research Facility), Edwards, California

- Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland

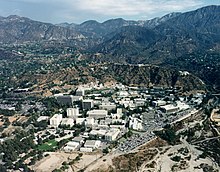

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) worked together with the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), one of the agencies behind Explorer 1, the first American satellite. It is located near Pasadena, California

- Langley Research Center (LaRC), founded in 1917, is the oldest of NASA's field centers, located in Hampton, Virginia. LaRC focuses primarily on aeronautical research, though the Apollo lunar lander was flight-tested at the facility and a number of high-profile spacecraft have been planned and designed on-site. Langley currently devotes two-thirds of its programs to aeronautics, and the rest to space.

- John H. Glenn Research Center (GRC), formerly the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, located in Brook Park, Ohio, was established in 1942 as a laboratory for aircraft engine research. John H. Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio

- John C. Stennis Space Center, Bay St. Louis, Mississippi

Subordinate facilities include the Wallops Flight Facility in Wallops Island, Virginia; the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, Louisiana; the White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico; and Deep Space Network stations in Barstow, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia.

Leadership

The agency's leader, NASA's administrator, is nominated by the President of the United States subject to approval of the US Senate, and reports to him or her and serves as senior space science advisor. Though space exploration is ostensibly non-partisan, the appointee usually is associated with the President's political party (Democratic or Republican), and a new administrator is usually chosen when the Presidency changes parties. The only exceptions to this have been:

- Democrat Thomas O. Paine, acting administrator under Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson, stayed on while Republican Richard Nixon tried but failed to get one of his own choices to accept the job. Paine was confirmed by the Senate in March 1969 and served through September 1970.[208]

- Republican James C. Fletcher, appointed by Nixon and confirmed in April 1971, stayed through May 1977 into the term of Democrat Jimmy Carter.

- Daniel Goldin was appointed by Republican George H. W. Bush and stayed through the entire administration of Democrat Bill Clinton.

- Robert M. Lightfoot, Jr., associate administrator under Democrat Barack Obama, was kept on as acting administrator by Republican Donald Trump until Trump's own choice Jim Bridenstine, was confirmed in April 2018.[209]

The first administrator was Dr. T. Keith Glennan appointed by Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower. During his term he brought together the disparate projects in American space development research.[210]

The second administrator, James E. Webb (1961–1968), appointed by President John F. Kennedy, was a Democrat who first publicly served under President Harry S. Truman. In order to implement the Apollo program to achieve Kennedy's Moon landing goal by the end of the 1960s, Webb directed major management restructuring and facility expansion, establishing the Houston Manned Spacecraft (Johnson) Center and the Florida Launch Operations (Kennedy) Center. Capitalizing on Kennedy's legacy, President Lyndon Johnson kept continuity with the Apollo program by keeping Webb on when he succeeded Kennedy in November 1963. But Webb resigned in October 1968 before Apollo achieved its goal, and Republican President Richard M. Nixon replaced Webb with Republican Thomas O. Paine.[citation needed]

James Fletcher was responsible for early planning of the Space Shuttle program during his first term as administrator under President Nixon. He was appointed for a second term as administrator from May 1986 through April 1989 by President Ronald Reagan to help the agency recover from the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.[citation needed]

Former astronaut Charles Bolden served as NASA's twelfth administrator from July 2009 to January 20, 2017.[211] Bolden is one of three former astronauts who became NASA administrators, along with Richard H. Truly (served 1989–1992) and Frederick D. Gregory (acting, 2005).

The agency's administration is located at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC, and provides overall guidance and direction.[212] Except under exceptional circumstances, NASA civil service employees are required to be citizens of the United States.[213]

NASA Advisory Council

In response to the Apollo 1 accident, which killed three astronauts in 1967, Congress directed NASA to form an Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) to advise the NASA Administrator on safety issues and hazards in NASA's aerospace programs. In the aftermath of the Shuttle Columbia disaster, Congress required that the ASAP submit an annual report to the NASA Administrator and to Congress.[214] By 1971, NASA had also established the Space Program Advisory Council and the Research and Technology Advisory Council to provide the administrator with advisory committee support. In 1977, the latter two were combined to form the NASA Advisory Council (NAC).[215]

The NASA Authorization Act of 2014 reaffirmed the importance of ASAP.

Directives

Some of NASA's main directives have been the landing of a manned spacecraft on the Moon, the designing and construction of the Space Shuttle, and efforts to construct a large, crewed space station. Typically, the major directives originated from the intersection of scienctific interest and advice, political interests, federal funding concerns, and the public interest, that all together brought varying waves of effort, often heavily swayed by technical developments, funding changes, and world events. For example, in the 1980s, the Reagan administration announced a directive with a major push to build a crewed space station, given the name Space Station Freedom.[216] But, when the Cold War ended, Russia, the United States, and other international partners came together to design and build the International Space Station.

In the 2010s, major shifts in directives include retirement of the Space Shuttle, and the later development of a new crewed heavy lift rocket, the Space Launch System. Missions for the new Space Launch System have varied, but overall, NASA's directives are similar to the Space Shuttle program as the primary goal and desire is human spaceflight. Additionally, NASA's Space Exploration Initiative of the 1980s opened new avenues of exploration focused on other galaxies.

For the coming decades, NASA's focus has gradually shifting towards eventual exploration of Mars.[217] One of the technological options focused on was the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM).[217] ARM had largely been defunded in 2017, but the key technologies developed for ARM would be utilized for future exploration, notably on a solar electric propulsion system.[218][217]

Longer project execution timelines leaves future executive administration officials to execute on a directive, which can lead to directional mismanagement.

Previously, in the early 2000s, NASA worked towards a strategic plan called the Constellation Program, but the program was defunded in the early 2010s.[219][220][221][222] In the 1990s, the NASA administration adopted an approach to planning coined "Faster, Better, Cheaper".[223]

NASA Authorization Act of 2017

The NASA Authorization Act of 2017, which included $19.5 billion in funding for that fiscal year, directed NASA to get humans near or on the surface of Mars by the early 2030s.[224]

Though the agency is independent, the survival or discontinuation of projects can depend directly on the will of the President.[225]

Space Policy Directive 1

In December 2017, on the 45th anniversary of the last crewed mission to the Lunar surface, President Donald Trump approved a directive that includes a lunar mission on the pathway to Mars and beyond.[217]

We'll learn. The directive I'm signing today will refocus America's space program on human exploration and discovery. It marks an important step in returning American astronauts to the Moon for the first time since 1972 for long-term exploration and use. This time, we will not only plant our flag and leave our footprint, we will establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars. And perhaps, someday, to many worlds beyond.

— President Donald Trump, 2017[226]

New NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine addressed this directive in an August 2018 speech where he focused on the sustainability aspects—going to the Moon to stay—that are explicit in the directive, including taking advantage of US commercial space capability that did not exist even five years ago, which have driven down costs and increased access to space.[227]

Use of the metric system

US law requires the International System of Units to be used in all U.S. Government programs, "except where impractical".[228]

In 1969, the Apollo 11 landed on the Moon using a mix of United States customary units and metric units. In the 1980s, NASA started the transition towards full metrication,[citation needed] and was predominantly metric by the 1990s.[229] On September 23, 1999, a unit mixup between US and SI units resulted in a loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter.[230]

In August 2007, NASA stated that all future missions and explorations of the Moon will be done entirely using the SI system. This was done to improve cooperation with space agencies of other countries which already use the metric system.[231]

Today[when?] NASA is predominantly working with SI units, but some projects still use a mix of US and SI units.

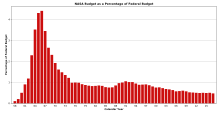

Budget

NASA's share of the total federal budget peaked at approximately 4.41% in 1966 during the Apollo program, then rapidly declined to approximately 1% in 1975, and stayed around that level through 1998.[225][232] The percentage then gradually dropped, until leveling off again at around half a percent in 2006 (estimated in 2012 at 0.48% of the federal budget).[233] In a March 2012 hearing of the United States Senate Science Committee, science communicator Neil deGrasse Tyson testified that "Right now, NASA's annual budget is half a penny on your tax dollar. For twice that—a penny on a dollar—we can transform the country from a sullen, dispirited nation, weary of economic struggle, to one where it has reclaimed its 20th century birthright to dream of tomorrow."[234][235]

Despite this, public perception of NASA's budget differs significantly: a 1997 poll indicated that most Americans believed that 20% of the federal budget went to NASA.[236]

For Fiscal Year 2015, NASA received an appropriation of US$18.01 billion from Congress—$549 million more than requested and approximately $350 million more than the 2014 NASA budget passed by Congress.[237]

In Fiscal Year 2016, NASA received $19.3 billion.[238]

President Donald Trump signed the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017 in March, which set the 2017 budget at around $19.5 billion.[238] The budget is also reported as $19.3 billion for 2017, with $20.7 billion proposed for FY2018.[239][240]

Examples of some proposed FY2018 budgets:[240]

- Exploration: $4.79 billion

- Planetary science: $2.23 billion

- Earth science: $1.92 billion

- Aeronautics: $0.685 billion

Gallery

Observations

-

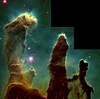

Various nebulae observed from a NASA space telescope

-

1 Ceres

-

Pluto

Past and current spacecraft

-

Hubble Space Telescope, astronomy observatory in Earth orbit since 1990. Also visited by the Space Shuttle

-

Curiosity rover, roving Mars since 2012

-

Perseverance rover

Planned spacecraft

-

Space Launch System rocket

-

Lunar Gateway space station

Concepts

NASA has developed oftentimes elaborate plans and technology concepts, some of which become worked into real plans.

-

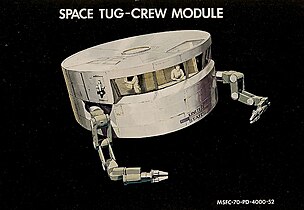

Concept of cargo transport from Space Shuttle to Nuclear Shuttle, 1960s

-

Space Tug concept, 1970s

-

Vision mission for an interstellar precursor spacecraft by NASA, 2000s

-

Langley's Mars Ice Dome design for a Mars habitat, 2010s

See also

- Chinese space program – Space program of the People's Republic of China

- List of crewed spacecraft

- List of United States rockets

Articles about NASA

- Astronomy Picture of the Day – NASA and MTU website

- List of NASA aircraft

- NASA Advanced Space Transportation Program

- NASA Art Program

- NASA Research Park – Research park near San Jose, California

- NASA TV – Television channels of NASA

- NASAcast – Independent agency of the United States Federal Government

- TechPort (NASA) – Technology Portfolio System

Related agencies

- Department of Defense Manned Space Flight Support Office – DoD support to NASA ended 2007

- Indian Space Research Organisation – Indian national space and aeronautics agency

- Roscosmos – Space agency of Russia

- United States Space Force – Space service branch of the U.S. military

Notes

- ^ NASA is an independent agency that is not a part of any executive department, but reports directly to the President.[6][7]

- ^ The descent stage of the LM stayed on the Moon after landing, while the ascent stage brought the two astronauts back to the CSM and then fell back to the Moon.

- ^ From left to right: Launch vehicle of Apollo (Saturn 5), Gemini (Titan 2) and Mercury (Atlas). Left, top-down: Spacecraft of Apollo, Gemini and Mercury. The Saturn IB and Mercury-Redstone launch vehicles are left out.

References

- ^ US Centennial of Flight Commission, NACA Archived February 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. centennialofflight.net. Retrieved on November 3, 2011.

- ^ Lale Tayla; Figen Bingul (2007). "NASA stands 'for the benefit of all.'—Interview with NASA's Dr. Süleyman Gokoglu". The Light Millennium. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Workforce Profile". NASA. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Casey Dreier (December 30, 2019). "NASA's FY 2020 Budget". The Planetary Society. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Dunbar, Brian. "The Worm is Back!". NASA. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Official US Executive Branch Web Sites – Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room (Serial and Government Publications Division, Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". hq.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Ike in History: Eisenhower Creates NASA". Eisenhower Memorial. 2013. Archived from the original on November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "The National Aeronautics and Space Act". NASA. 2005. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- ^ a b Bilstein, Roger E. (1996). "From NACA to NASA". NASA SP-4206, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles. NASA. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-16-004259-1. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ Netting, Ruth (June 30, 2009). "Earth—NASA Science". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Netting, Ruth (January 8, 2009). "Heliophysics—NASA Science". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Roston, Michael (August 28, 2015). "NASA's Next Horizon in Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ Netting, Ruth (July 13, 2009). "Astrophysics—NASA Science". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Erickson, Mark (2005). Into the Unknown Together—The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight (PDF). ISBN 978-1-58566-140-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2009.

- ^ Subcommittee On Military Construction, United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Armed Services (January 21–24, 1958). Supplemental military construction authorization (Air Force).: Hearings, Eighty-fifth Congress, second session, on H.R. 9739. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c "T. Keith Glennan". NASA. August 4, 2006. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ von Braun, Werner (1963). "Recollections of Childhood: Early Experiences in Rocketry as Told by Werner Von Braun 1963". MSFC History Office. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Van Atta, Richard (April 10, 2008). "50 years of Bridging the Gap" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ "NASA Strategic Plan, 2011" (PDF). NASA Headquarters. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ "Launch History (Cumulative)" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Experimental Communications Satellites, 1958–1995". NASA. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "NASA, Explorers program". NASA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ NASA mission STS-31 (35) Archived August 18, 2011, at WebCite

- ^ "JPL, Chapter 4. Interplanetary Trajectories". NASA. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Missions to Mars". The Planet Society. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Missions to Jupiter". The Planet Society. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "JPL Voyager". JPL. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Pioneer 10 spacecraft send last signal". NASA. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "The golden record". JPL. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "New Horizon". JHU/APL. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Voyages Beyond the Solar System: The Voyager Interstellar Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Jim (September 15, 2008). "NASA Selects 'MAVEN' Mission to Study Mars Atmosphere". NASA. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ "Hubble Essentials". HubbleSite.org. Space Telescope Science Institute. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Hubble Marks 30 Years in Space with Tapestry of Blazing Starbirth". HubbleSite.org. Space Telescope Science Institute. April 24, 2020. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hubble Space Telescope cbsnews20130530was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Canright, Shelley. "NASA's Great Observatories". NASA. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA Announces New James Webb Space Telescope Target Launch Date". NASA. July 16, 2020. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (July 16, 2020). "NASA Delays James Webb Telescope Launch Date, Again – The universe will have to wait a little longer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Hubble successor given mid-December launch date". BBC News. September 9, 2021. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 18, 2015). "The Long, Strange Trip to Pluto, and How NASA Nearly Missed It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Leo Laporte (August 31, 2015). "Alan Stern: principal investigator for New Horizons". TWiT.tv (Podcast). Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "New Horizons, The First Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt: Exploring Frontier Worlds" (PDF) (Press Kit). Applied Physics Laboratory. January 16, 2007.

- ^ Scharf, Caleb A. (February 25, 2013). "The Fastest Spacecraft Ever?". Scientific American. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (June 9, 2015). "Here's Why The New Horizons Spacecraft Won't Be Stopping At Pluto". io9. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ Whitwam, Ryan (December 13, 2017). "New Horizons Space Probe Target May Have its Own Tiny Moonlet – ExtremeTech". Ziff Davis. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "New Horizons: NASA's Mission to Pluto". NASA. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "New Horizons – News". Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. December 6, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 14, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Completes Flyby of Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (July 14, 2015). "Pluto close-up: Spacecraft makes flyby of icy, mystery world". Excite. Associated Press (AP). Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ "New Horizons". NASA. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Buckley, Mike; Stotoff, Maria (July 14, 2015). "15-149 NASA's Three-Billion-Mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic Encounter". NASA. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Cofield, Calia (August 24, 2016). "How We Could Visit the Possibly Earth-Like Planet Proxima b". Space.com. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (October 28, 2016). "No More Data From Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Jayawardhana, Ray (December 11, 2015). "Give It Up for Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Talbert, Tricia (August 28, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons Team Selects Potential Kuiper Belt Flyby Target". NASA. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Cofield, Calla (August 28, 2015). "Beyond Pluto: 2nd Target Chosen for New Horizons Probe". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (October 22, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons on new post-Pluto mission". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 28, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Corum, Jomathan (February 10, 2019). "New Horizons Glimpses the Flattened Shape of Ultima Thule – NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew past the most distant object ever visited: a tiny fragment of the early solar system known as 2014 MU69 and nicknamed Ultima Thule. – Interactive". The New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 31, 2018). "New Horizons Spacecraft Completes Flyby of Ultima Thule, the Most Distant Object Ever Visited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Gladstone, G. Randall; et al. (August 7, 2018). "The Lyman-α Sky Background as Observed by New Horizons". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (16): 8022. arXiv:1808.00400. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.8022G. doi:10.1029/2018GL078808. S2CID 119395450.

- ^ Letzter, Rafi (August 9, 2018). "NASA Spotted a Vast, Glowing 'Hydrogen Wall' at the Edge of Our Solar System". Live Science. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ "Where Is New Horizons?". pluto.jhuapl.edu. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (September 29, 2023). "NASA's New Horizons to Continue Exploring Outer Solar System". NASA. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mars Science Laboratory NASA-2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference