Melbourne central business district

| Melbourne CBD Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CBD of Melbourne as viewed from Eureka Tower, June 2012 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′50″S 144°57′47″E / 37.814°S 144.963°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 54,941 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 8,450/km2 (21,890/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1835 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3000, 3001, 3004[2] 8001 (PO Box) | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 30 m (98 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 6.5 km2 (2.5 sq mi)[3] | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | |||||||||||||||

| County | Bourke | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Melbourne central business district (colloquially known as "the City" or "the CBD",[4] and gazetted simply as Melbourne[5]) is the city centre of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. As of the 2021 census, the CBD had a population of 54,941, and is located primarily within the local government area City of Melbourne, with some parts located in the City of Port Phillip.

The central business district is centred on the Hoddle Grid, the oldest part of the city laid out in 1837. It also includes parts of the parallel and perpendicular streets to the north, bounded by Victoria Street and Peel Street; and extends south-east along much of the area immediately surrounding St Kilda Road.[6]

The CBD is the core of Greater Melbourne's metropolitan area, and is a major financial centre in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region. It is home to several major attractions in Melbourne, including the many of the city's famed lanes and arcades, the distinct blend of contemporary and Victorian architecture, the Queen Victoria Market, the Melbourne Botanical Gardens, the National Gallery of Victoria, the State Library, Parliament House, and Federation Square.[7] It contains Flinders Street railway station, the centre of Melbourne's metropolitan railway network, and the world's busiest tram corridor along Swanston Street.

In recent times, it has been placed alongside New York City and Berlin as one of the world's great street art meccas, and designated a "City of Literature" by UNESCO in its Creative Cities Network.[8]

Foundation of Melbourne

[edit]

Batman's treaty

[edit]In April 1835, John Batman, a prominent grazier and a member of the Geelong and Dutigalla Association (later Port Phillip Association),[9][10] sailed from Launceston on the island of Van Diemen's Land (now the State of Tasmania), aboard the schooner Rebecca, in search of fresh grazing land in the south-east of the Colony of New South Wales (the mainland Australian continent). He sailed across Bass Strait, into the bay of Port Phillip, and arrived at the mouth of the Yarra River in May.[11] After exploring the surrounding area, he met with the elders of the indigenous Aboriginal group, the Wurundjeri of the Kulin nation alliance, and negotiated a transaction for 600,000 acres (940 sq mi; 2,400 km2) which later became known as Batman's Treaty.[12] The transaction, which is believed to have taken place on the bank of Merri Creek (near the modern day suburb of Northcote),[13] consisted of an offering of: blankets, knives, mirrors, sugar, and other such items; to be also tributed annually to the Wurundjeri.[12] The last sentence of Batman's journal entry on this day became famous as the founding charter of the settlement.[9]

So the boat went up the large river. And, I am glad to state about six miles up found the river all good water and very deep. This will be the place for a village.

— Journal of John Batman (8 June 1835).[11]

Upon returning to Van Diemen's Land, Batman's treaty was deemed invalid by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Richard Bourke, under the Proclamation of Governor Bourke in August 1835.[14] It was the belief of Governor Bourke, as well as the Governor of Van Diemen's Land, Sir George Arthur, that the Aboriginal people did not have any official claims to the lands of the Australian continent. The proclamation formally declared, under the doctrine of terra nullius, that The Crown owned the whole of the Australian continent and that only it alone could sell and distribute land.[14] It therefore voided any contracts or treaties made without the consent of the government, and declared any person attempting to rely on such a treaty to be trespassing.[14] However, at the time the proclamation was being drawn up, a prominent businessman from Van Diemen's Land, John Pascoe Fawkner, had also funded an expedition to the area; which sailed from George Town aboard the schooner Enterprize.[15] At the same time, the Port Phillip Association had also funded a second expedition; which sailed from Launceston aboard the Rebecca.[9]

Fawkner's fait accompli

[edit]The settlement party aboard the Enterprize entered the Yarra River, and anchored close to the site chosen by Batman, on 29 August.[16] The party went ashore the following day (near what is today William Street; and is now celebrated as Melbourne Day) and landed their stores, livestock and began to construct the settlement.[15] The Association party aboard the Rebecca arrived in September after spending time at a temporary camp at Indented Head, where they encountered William Buckley – an escaped convict, believed dead, who had been living for 32 years with the indigenous Aboriginal group, the Wathaurong of the Kulin nation alliance.[17] Batman was dismayed to discover the settlers of the Enterprize had established a settlement in the area and informed the settlers that they were trespassing on the Association's land. However, according to the Proclamation of Governor Bourke, both the parties were in fact trespassing on Crown land.[14] When Fawkner (who was noted for his democratic nature)[15] arrived in October, and following tense arguments between the two parties, negotiation were made for land to be shared equally.

As Fawkner had arrived after the two parties, he was aware of the Proclamation of Governor Bourke, which had gained approval from the Colonial Office in October.[14] He knew that cooperation would be vital if the settlement was to continue to exist fait accompli. Land was then divided, and the settlement existed peacefully, but without a formal system of governance.[16] It was referred to by a number of names, including: "Batmania" and "Bearbrass"[11][18] of which the latter was agreed upon by Batman and Fawkner.[18] Fawkner assumed a leading role in the establishment of Bearbrass;[15] which, by early 1836, consisted of 177 European settlers (142 male and 35 female settlers).[16] The Secretary of State for the Colonies, Charles Grant, recognised the settlement's fait accompli that same year, and authorised Governor Bourke to transfer Bearbrass to a Crown settlement.[16] Batman and the Port Phillip Association were compensated £7,000 for the land.[9] And, in March 1837, it was officially renamed "Melbourne" by Governor Bourke in honour of the British Prime Minister of the day, William Lamb (the Lord Melbourne).[16]

Boundaries and geography

[edit]

The Melbourne CBD does not have current official boundaries, but rather is commonly understood to be the Hoddle Grid plus the parallel streets immediately to the north, including the Queen Victoria Market, and the area between Flinders Street and the river. There are a number of officially demarcated areas which are similar, but all differ slightly. Some that are larger still use the term 'Melbourne', which leads to some confusion.

The boundaries of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Statistical Area Level 2 'Melbourne' is a good representation of the commonly understood area of 'the CBD'; it includes the Hoddle Grid, plus the area of parallel streets just to the north up to Victoria Street including the Queen Victoria Market, but not the Flagstaff Gardens or the streets to the west of it, and the area between Flinders Street and the Yarra river west of Swanston Street. A map can be found here. This is not to be confused with the State Suburb level area, also called Melbourne, which is a larger area.

The area of the postcode 3000 is very similar, but also includes the area to the east of Flinders Street Station, and a leg up northern Elizabeth Street. A map of this can be found here and here.

The locality (suburb) of Melbourne is an official area,[19] but is larger; it is the area of postcode 3000 combined with the area of postcode 3004 (an area to the south of the central city, including the Domain and Botanic Gardens parklands, and the east side of St Kilda Road) and both of these postcodes are known as Melbourne.

The term 'central business district', or 'CBD', was first used in the Report on a planning scheme for the central business area of the City of Melbourne by town planner E.F. Borrie, which was commissioned by the City of Melbourne, and published in 1964. The maps used in the report show the CBD as just the Hoddle Grid, plus the parallel streets immediately to the north, and the area between Flinders Street and the river, very similar to the ABS area.

Since 1999, the Melbourne Planning Scheme has included a 'Capital City Zone' which is a much larger area, including the former CBD, minus the RMIT area, but including Southern Cross Station, much of Southbank down a line along the West Gate Freeway, Kingsway, down to Coventry Street, South Melbourne, and the north wharf area and the South Wharf area. A map of the CCZ can be found here. The area described as 'the central city' in Clause 21.08 of the Melbourne Planning Scheme is similar, but also includes the Docklands.[20]

There are several adjoining areas that have important functions that are sometimes included within the idea of 'the CBD' or the central city, such as Parliament House and the Treasury buildings on Spring Street, which are officially in East Melbourne, and Southern Cross railway station on Spencer Street, which is officially in Docklands. Other areas have in the last 30 years become heavily developed with apartments, office buildings and important functions similar to the CBD, and are sometimes incorporated, such as the Docklands (with Docklands Stadium) to the west, and Southbank and South Wharf on the other side of the Yarra River.

Despite the area being described as the central business district, it is neither the geographic or demographic centre of Melbourne; due to urban sprawl to the south east the geographic centre is in the southeastern suburbs (in 2002 it was located at Bourne Street, Glen Iris[21]).

Hoddle Grid

[edit]

The Hoddle Grid is the rectangular grid of the streets in the centre of the city laid out in 1837 by government surveyor Robert Hoddle. All major streets are one and half chains (99 ft or 30 m) in width, while all blocks are exactly ten chains square (ten acres (4.0 ha), 660 ft × 660 ft or 200 m × 200 m). It is one-mile (1.6 km) long by one-half-mile (0.80 km) wide. It is bounded by Flinders Street, Spencer Street, La Trobe Street and Spring Street. The grid's longest axis is oriented 70 degrees clockwise from true north, to align better with the course of the Yarra River. Most of the arterial streets outside the Hoddle Grid were aligned almost north–south, Melbourne, at 8 degrees clockwise from true north–noting that magnetic north was 8° 3' E in 1900, increasing to 11° 42' E in 2009.[22]

Hoddle's survey did not include any public squares or piazzas, reputedly to avoid any facilitation of protests or public loitering,[23] though colonial government practice did not generally include public squares other than land set aside for government buildings or markets.[24]

The whole town was at first accommodated within the Hoddle Grid, but the huge surge in immigration brought about by the Gold Rush in the 1850s quickly outgrew the grid spreading into the first suburbs in Fitzroy and South Melbourne (Emerald Hill), and beyond.

The Hoddle Grid and its fringes remained the centre and most active part of the city into the mid 20th century, with retail in the centre, banking and prime office space on Collins Street, medical professionals on the Collins Street hill, legal professions around William Street, and warehousing along Flinders Lane and in the western end. Government buildings like GPO, State Library, Supreme Court, and Customs House occupied various blocks with Parliament House and the railway stations on the edges.

Residential uses, most notably the slums of Little Lonsdale Street, were largely replaced by commercial uses by the 1950s, with residential not making a return until the 1990s with the conversion of older buildings. Since the 2000s this has accelerated with numerous high rise apartment buildings and student housing projects.

With the loss of residents, restricted retail and pub hours, the central city became dominated by 9-5 business uses, with one commentator remarking that in the 1970s, the city was "as deserted as war-torn Berlin".[25]

Demographics

[edit]

According to the 2016 census, the population of the CBD (the Level 2 statistical area of Melbourne) was 37,321 residents, about half of which were overseas students. Only 14.3% of residents were born in Australia, while 24.9% were born in China. Other places of birth included Malaysia 8.3%, India 6.2%, Indonesia 4.5% and South Korea 4.0%. Only English was spoken at home by 21.7% of residents, while 30.8% spoke Mandarin. Most of these overseas born are students, with 57.3% of residents attending a tertiary educational institution, and 54.3% of residents aged between 20 and 29.[30]

In common with Australian capital cities generally, especially Melbourne and Sydney, there has been remarkable growth in the CBD in the last 10 years to 2017. Residential units, population, jobs and visitation have all increased markedly, changing the central business district from a primarily business or work oriented hub, to a mixed business and residential district.[31] Prior to the 2010s, Australian CBD's were generally places workers would commute to from the suburbs and served little purpose beyond employment and shopping opportunity.

In this period, many sometimes very tall towers of small one and two bedroom apartments and studio-style student housing (with no carparks) have been built, greatly increasing the resident population of the CBD, including students. Many older buildings have been converted to loft-style apartments, and there are some older apartment buildings with larger more spacious units, with a relatively small amount of luxury housing. There are few families with young children, with only 3.1% of residents under the age of 14, and equally small numbers of over 50, so most residents are students or young professionals.[30]

Economy

[edit]The CBD is the core central activities district (CAD) of Greater Melbourne. It encompasses a number of places of significance, which include the, Federation Square, Melbourne Aquarium, Melbourne Town Hall, State Library of Victoria, State Parliament of Victoria and Supreme Court of Victoria. It is also the main terminus for the Melbourne metropolitan and Victorian regional passenger rail networks–being Flinders Street and Southern Cross stations respectively, as well as the most dense section of the Melbourne tram network.

Bordering its north-east perimeter is the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens as well as the Melbourne Museum. Just to the south are the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre, Crown Casino, Arts Centre Melbourne, and the National Gallery of Victoria

The central business district is a major financial centre in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region.[32] It is home to the corporate headquarters of the world's two largest mining companies: BHP and Rio Tinto; as well as two of Australia's "big four" banks: ANZ and the National Australia Bank, its two largest gaming companies: Crown and Tabcorp, largest telecommunications company Telstra, two largest transport management companies: Toll and Transurban and the iconic brewing company Foster's Group.

It also serves as the main administrative centre for the City of Melbourne as well as the State Government of Victoria – the latter with the suburb of East Melbourne. Two universities have major campuses in the area: the main city campus RMIT University (city campus), and three campuses for Victoria University (City King, Queen, Flinders campuses). The Victorian College of the Arts campus of the University of Melbourne lies just to the south.

The CBD, along with the adjacent Southbank area, has had comparatively unrestricted height limits in recent years, and has four of the six tallest buildings in Australia (or 5 of the top 10, excluding spires). The tallest in the CBD is currently Aurora Melbourne Central which topped out in December 2018. Melbourne had historically competed with Sydney for the tallest buildings, which until the 2000s were all office towers, and the three tallest buildings in Australia in the 1980s and 1990s were all in the Melbourne CBD.

Culture and sport

[edit]

Arts

[edit]Almost all the major theatres in Melbourne are located in the CBD or its fringes. Historic theatres including the Princess Theatre, Regent Theatre, Forum Theatre, Comedy Theatre, Athenaeum Theatre, Her Majesty's Theatre, and the Capitol Theatre are all located within the Hoddle Grid. The Arts Centre Melbourne (which includes the State Theatre, Hamer Hall, the Playhouse and the Fairfax Studio), and the Melbourne Recital Centre are located just to the south of the CBD, with the Sidney Myer Music Bowl in parklands to the east.

The Federation Square arts complex occupies a prime site on the corner of Flinders and Swanston Streets, and includes the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, the Australian art galleries of the National Gallery of Victoria, the Koorie Heritage Trust, and the Deakin Edge auditorium.

Melbourne is considered the literary centre of Australia, and has more bookshops and publishing companies per capita than any other city in Australia.[citation needed] The headquarters of the world's largest travel guidebook publisher Lonely Planet is located just outside the CBD in Carlton. In 2008, Melbourne was designated a "City of Literature" by UNESCO in its Creative Cities Network.[8] The State Library Victoria is the most visited library in the city, and hosts the Wheeler Centre. Melbourne has been placed alongside New York and Berlin as one of the world's great street art meccas,[33] and its extensive street art-laden laneways, alleys and arcades were voted by Lonely Planet readers as Australia's top cultural attraction.[34]

The CBD is home to many small independent galleries, often in the upper floors of older buildings or down laneways, and some of the most commercial galleries in Victoria are also in 'the city'.

Sports

[edit]

There are no sporting grounds within the CBD, but the 'shrine of sport' in Melbourne is the MCG (Melbourne Cricket Ground) located in the adjacent parkland known as Jolimont. Both the Melbourne Cricket Club and Melbourne Football Club are based there. The Melbourne Cricket Club has a fairly exclusive membership, whilst the Melbourne Football Club, although bearing the name Melbourne, is associated by the supporters of other suburban clubs as representing the central area and perceive its supporters to represent the locality and not the entire city.[35] The Melbourne Football Club has recently made efforts to shed its suburban tag and be embraced by the whole metropolitan area.[36]

Events

[edit]The CBD has hosted a number of events of significance, which include: the 1901 inauguration of the Government of Australia, 1956 Summer Olympic Games, 1981 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, 1995 World Police and Fire Games, 2000 World Economic Forum, 2006 Commonwealth Games, 2015 Cricket World Cup, G20 Ministerial Meeting – among others. It is also recognised for the substantial number of cultural and sports events and festivals it holds annually – many being the largest in Australia and the world.

Transport

[edit]

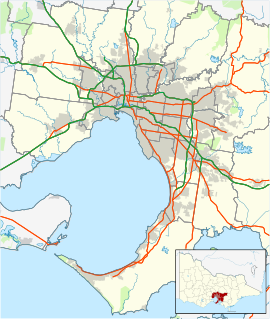

The Melbourne central business district is the transport hub of the city.

Flinders Street station is the hub for Melbourne's suburban train network and the busiest station,[37] Southern Cross station, which is the hub for regional and interstate transit located on Spencer Street, and the three underground stations of the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop–Parliament, Melbourne Central and Flagstaff stations are located on the east and north fringes. A hybrid rapid transit and heavy rail project known as the Metro Tunnel is currently under construction, with two stations in the city centre at the State Library and Town Hall.[38] This will be the first rapid transit system to serve the city of Melbourne and the second of its kind in Australia.

The Melbourne trams network is the world's largest, and most lines from the suburbs run down one of the streets of the CBD, with Swanston Street hosting of six lines, making it one of the world's busiest tram corridors. Trams also run along Flinders, Collins, Bourke, La Trobe, Spencer, Market, Elizabeth, and Spring Streets. In recent years nearly all CBD tram stops have been rebuilt as larger all-accessibility "superstops".[39]

The city is also well connected by bus services, with majority of buses running down Lonsdale Street, with major bus stops at Melbourne Central and Queen Victoria Village. Most bus routes service suburbs north and east of the city given the lack of train lines to these areas.

Major bicycle trails lead to the CBD and a main bicycle path down Swanston Street.

Ferries dock along the northbank of the Yarra at Federation Wharf and the turning basin at the Aquatic Centre. There is also a water taxi service to Melbourne and Olympic Parks.

Sister cities

[edit]City of Melbourne has five sister cities.[40] According to the City of Melbourne council, "the city as a whole has been nourished by their influence, which extends from educational, cultural and sporting exchanges to unparalleled business networking opportunities."[41][42] The recognised cities are:

Osaka, Japan (1978)

Osaka, Japan (1978) Tianjin, China (1980)

Tianjin, China (1980) Thessaloniki, Greece (1984)

Thessaloniki, Greece (1984) Boston, United States (1985)

Boston, United States (1985) Milan, Italy (2004)

Milan, Italy (2004)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Melbourne (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Geographic coordinates of Melbourne. Latitude, longitude, and elevation above sea level of Melbourne, Australia". dateandtime.info.

- ^ "2021 Australian Census SAL21640 Community Profile". Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Richards, Tim. "It's rooted: Aussie terms that foreigners just won't get". Traveller. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Locality names and boundary maps". Department of Transport and Planning. 2 September 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "2021 Melbourne, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ Diamonstein, Barbaralee (9 August 1987), "Victorian Scenes on a Melbourne Walk", New York Times, retrieved: 5 August 2011

- ^ a b "Melbourne, Australia: City of Literature Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine", Creative Cities Network, UNESCO, retrieved: 10 August 2011

- ^ a b c d Serle, Percival (1949). "Batman, John". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ "Port Phillip Association" (Web). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ a b c "Journal of John Batman". State Library of Victoria. Archived from the original (Web) on 21 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ a b "The Deed". Batmania. National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original (Web) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ Ellender, Isabel; Christiansen, Peter (2001). People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days. Melbourne: Merri Creek Management Committee. ISBN 0-9577728-0-7.

- ^ a b c d e "Governor Bourke's Proclamation 1835" (Web). Documenting Democracy. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 25 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Serle, Percival (1949). "Fawkner, John Pascoe". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Foundation of the Settlement" (PDF). History of the City of Melbourne. City of Melbourne. 1997. pp. 8–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ Morgan, John (1852). The Life and Times of William Buckley (Web). Hobart: Archibald MacDougall. pp. 116. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ a b Reed, Alexander Wyclif (1973). Place names of Australia. Sydney: Reed. p. 149. ISBN 0-589-50128-3.

- ^ Official map of localities can be found here

- ^ Government of Victoria 2009, p. 3, figure 12: Central City[specify]

- ^ Glen Iris still the heart of city's sprawl, The Age, 5 August 2002

- ^ "Magnetic Declination".

- ^ "Australians don't loiter in public space – the legacy of colonial control by design". The Conversation. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne: The City's History and Development. Melbourne: City of Melbourne. pp. 25–29.

- ^ "Rare house in Melbourne's CBD to return to its commercial roots". Commercial Real Estate. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Chinatown Melbourne". Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Melbourne's multicultural history". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "World's 8 most colourful Chinatowns". Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "The essential guide to Chinatown". Melbourne Food and Wine Festival. Food + Drink Victoria. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "2016 Census QuickStats: Melbourne". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "CITY OF MELBOURNE CLUE 2017 REPORT" (PDF). City of Melbourne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Friedman, John (1997), "Cities Unbound: The Intercity Network in the Asia-Pacific Region", Management of Social Transformations, UNESCO, retrieved: 5 August 2011

- ^ Allen, Jessica. The World's Best Cities for Viewing Street Art, International Business Times (2010). Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Topsfield, Jewel. Brumby slams Tourism Victoria over graffiti promotion, The Age (2008). Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Melbourne Demons – The rust bucket of Australia from ConvictCreations.com

- ^ A new base for Demons? Archived 8 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine from the Age

- ^ "Research and statistics". Public Transport Victoria. 2013–2014. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Build, Victoria's Big (17 March 2022). "Metro Tunnel Project Business Case". Victoria's Big Build. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "Accessible trams". Public Transport Victoria. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "International connections". melbourne.vic.gov.au. City of Melbourne. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ "City of Melbourne – International relations – Sister cities". City of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Melbourne and Boston: Sister Cities Association". Melbourne-Boston.org. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Government of Victoria (2009), Melbourne Planning Scheme, Department of Planning and Community Development (PDF version. Retrieved 25 April 2017.)

- Melbourne City Council (1997), The History of the City of Melbourne, Melbourne City Records and Archives Branch (PDF version. Retrieved 5 August 2011.)

External links

[edit]- City of Melbourne website of the local government

- Official website of Tourism Victoria

- Local history of Melbourne CBD