User:Turco85/Turkish people

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

- For other uses of Turkish, see Turkish (disambiguation), and for the broader concept of Turkic-speaking ethnic groups, see Turkic peoples.

Turkish people, also known as the "Turks" (Turkish: singular: Türk, plural: Türkler), are a nation and ethnic group primarily living in Turkey, and in the former lands of the Ottoman Empire where Turkish minorities have been established in the Balkans, the island of Cyprus, the Levant, Meskhetia, and North Africa. The Turkish minorities are the second largest ethnic groups in Bulgaria and Cyprus. In addition, due to modern migration, a Turkish diaspora has been established, particularly in Western Europe (see Turks in Europe), where large communities have been formed in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. There are also significant Turkish communities living in Australia, the former Soviet Union and the United States.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Although Turkic languages may have been spoken as early as 600 BC,[1] the first mention of the ethnonym "Turk" may date from Herodotus' (c. 484-425 BCE) reference to "Targitas", the first king of the Scythians.[2] During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the "Turcae" in the forecasts north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the "Tyrcae" among the people of the same area.[2] The first definite reference to the Turks come mainly from Chinese sources in the sixth century. In these sources, "Turk" appears as "Tujue" (T’u-chue), meaning "strong" or "powerful", which was used to refer to the Göktürks.[3][4] Seventh century Chinese sources preserve the origins of the Turks stating that they were a branch of the Hsiung-nu (Huns) and living near the "West Sea", perhaps the Caspian Sea.[2] Modern sources tends to indicate that the Turks' ancestors lived within the state of the Hsiung-nu in the Transbaikal area and that they later, during the fifth century, migrated to the southern Altay.[2] Between the sixth and ninth centuries, Turkic rulers began a systematic conquest of northern China, central Asia, and the Eurasian steppe between the Syr Darya and Volga River. However, it was in the ninth century when the Great Seljuk Empire had emerged that the Turks began their expansion to the west directly colliding with the Byzantine Empire. In 1071, the Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert and within twenty to thirty years after the battle, numerous "Beyliks" (principalities) were established throughout Anatolia.[5]

Ancient era[edit]

The ancient Turks were overwhelmingly nomadic, with a strong interest in trade, and were mostly Shamanists, although others were also adherants of Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity, or, especially, Buddhism.[2] However, due to the Muslim conquests, the Turks began converting to Islam. Although initiated by the Arabs, the conversion of the Turks to Islam was filtered through Persian and Central Asian culture. Most Turks converted through the efforts of missionaries, Sufis, and merchants. At the same time, the Turks entered the Muslim world proper as slaves, the booty of Arab raids and conquests. Under the Umayyads, most were domestic slaves, whilst under the Abbasids, increasing numbers were trained as soldiers.[2] By the ninth century, Turkish commanders were leading the caliphs’ Turkish troops into battle. As the Abbasid caliphate declined, Turkish officers assumed more military and political power taking over or establishing provincial dynasties with their own corps of Turkish troops.[2]

Seljuk era[edit]

The Seljuk Turks were a nomadic people from Central Asia who had converted to Sunni Islam and flourished as military mercenaries for the Abbasid caliphate, where they were known for their ability as mounted archers.[6] Moving gradually into Persia and Armenia as the Abbasids weakened, by the eleventh century, the Seljuk Turks grew in number and were able to occupy the eastern province of the Abbasid Empire. Although ethnically Turkish, the Seljuk Turks appreciated and became the purveyors of the Persian culture over the Turkish culture.[7][8] By 1055, the Seljuk Empire captured Baghdad and in the course of the early eleventh century the Turks made their first incursions into the edges of Anatolia.[6]

The victory of the Turks at the Battle of Manzikert, north of Lake Van, over the Byzantine Empire in 1071 opened the gates of Anatolia to the Seljuk Turks led by Alp Arslan.[9] The Turkish language and Islam were introduced and gradually spread over the region and the slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway.[9] In dire straits, the Byzantine Empire turned to the West for help setting in motion the pleas that led to the Crusades.[10] Between 1096 and 1099 the First Crusade commenced, driven from Iznik, the Seljuk Turks established the Sultanate of Rum from their new capital at Konya in 1097.[9] The Muslim Turks lived alongside their Christian subjects relatively peacefully as they had been freed from the burden of heavy Byzantine taxes, although many Christians still converted to Islam in order to save themselves from further taxation.[9] Moreover, other Turcoman tribes who had also swept into Anatolia at the same time as the Seljuk Turks retained their nomadic ways. These tribes were more numerous than the Seljuk Turks, and rejecting the sedentary lifestyle, adhered to an impregnated Islam with animism and shamanism from their central Asian steppeland origins, which then mixed with new Christian influences. From this popular and syncretist Islam, with its mystical and revolutionary aspects, sects such as the Alevis and Bektashis emerged.[9]

By 1243, at the Battle of Köse Dağ, the Mongols were victorious over the Seljuk Turks and became the new rulers of Anatolia, and in 1256, the second Mongol invasion of Anatolia caused widespread distruction. As the Mongols occupied more lands in Asia Minor, the Turks were forced to move further to western Anatolia and settled in the Seljuk-Byzantine frontier.[11] Particularly after 1277, political stability within the Seljuk territories rapidly disintegrated, leading to the strengthening of Turcoman principalities in the western and southern parts of Anatolia called the "beyliks".[12]

Beyliks era[edit]

Once the Seljuk Turks were defeated by the Mongol's conquest of Anatolia, the Turks became the vassal of the Ilkhans.[11] As the Mongols occupied more lands in Asia Minor, the Turks moved further to western Anatolia and settled in the Seljuk-Byzantine frontier. By the last decades of the 13th century, the Ilkhans and their Seljuk vassals lost control over much of Anatolia to these Turkoman peoples.[11] A number of Turkish lords managed to establish themselves as rulers of various principalities, known as "Beyliks". Amongst these beyliks, along the Aegean coast, from north to south, stretched the beyliks of Karasi, Saruhan, Aydin, Menteşe and Teke. Inland from Teke was Hamid and east of Karasi was the beylik of Germiyan. To the north-west of Anatolia, around Söğüt, was the small and, at this stage, insignificant, Ottoman beylik which was hemmed in to the east by other more substantial powers like Karaman, based on Iconium, which ruled from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Although the Ottomans were only a small principality among the numerous Turkish beyliks, and thus posed the smallest threat to the Byzantine authority, their location in north-western Anatolia, in the former Byzantine province of Bithynia, became a fortunate position for their future conquests. The Latins, who had conquered the city of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, established a Latin Empire (1204–61), divided the former Byzantine territories in the Balkans and the Aegean among themselves, and forced the Byzantine Emperors into exile at Nicaea (present-day Iznik). From 1261 onwards, the Byzantines were largely preoccupied with regaining their control in the Balkans.[11] Toward the end of the 13th century, as Mongol power began to decline, the Turcoman chiefs assumed greater independence.[13]

Ottoman era[edit]

Under its founder, Osman I, the Ottoman beylik expanded along the Sakarya River and westward towards the Sea of Marmara. Thus, the population of western Asia Minor had largely become Turkish-speaking and Muslim in religion.[11] It was under his son, Orhan I, who had attacked and conquered the important urban center of Bursa in 1326, proclaiming it as the Ottoman capital, that the Ottoman Empire developed considerably. In 1354, the Ottomans crossed into Europe and established a foothold on the Gallipoli Peninsula while at the same time pushing east and taking Ankara.[14][15] Many Turks from Anatolia began to settle in the region abandoned by the inhabitants who had fled Thrace before the Ottoman invasion.[16] However, the Byzantines were not the only ones to suffer from the Ottoman advancement for, in the mid-1330s, Orhan annexed the Turkish beylik of Karasi. This advancement was maintained by Orhan's son Murad I who more than tripled the territories under his direct rule, reaching some 100,000 square miles, evenly distributed in Europe and Asia Minor.[17]

Gains in Anatolia were matched by those in Europe; once the Ottoman forces took Edirne (Adrianople), which became the capital of the Ottoman empire in 1365, they opened their way into Bulgaria and Macedonia in 1371 at the Battle of Maritsa.[18] With the conquests of Thrace, Macedonia, and Bulgaria, significant numbers of Turkish emigrants settled in these regions.[16] This form of Ottoman-Turkish colonization became a very effective method to consolidate their position and power in the Balkans. The colonizers consisted of soldiers, nomads, farmers, artisans and merchants, dervishes, preachers and other religious functionaries, and administrative personnel.[19] While Ottoman attacks were launched into the kingdom of Bosnia and Serbia, Niš falling in 1385, further south, Ottoman forces were active in Greece, taking Thessaloniki in 1397. Under Murad's son, Bayezid I, the Ottoman state continued to expand. In Anatolia, the beyliks of Menteşe and Aydin fell to the Ottomans in 1389-90. In Europe, Bayzeid ultimately took Serbia and Ottoman forces moved into Bulgaria and Wallachia. This advancement resulted in a large crusading force which, in 1396, met the Ottoman forces in the Battle of Nicopolis, and was soundly defeated, thus effectively ending the era of Christian crusading to the east.[18]

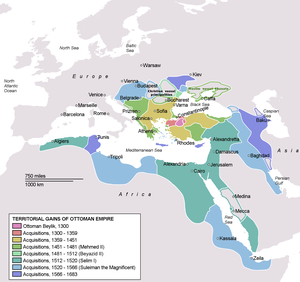

Half a century later, in 1453, Ottoman armies, under Sultan Mehmed II, conquered Constantinople.[17] Mehmed reconstructed and repopulated the city, renaming it "Istanbul", and making it the new Ottoman capital.[20] After the Fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion with its borders eventually going deep into Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[21] Selim I dramatically expanded the empire’s eastern and southern frontiers in the Battle of Chaldiran. He established Ottoman rule in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria and gained recognition as the guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[22] His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, further expanded the conquests after capturing Belgrade in 1521 and using its territorial base to conquer Hungary, and other Central European territories, after his victory in the Battle of Mohács. Meanwhile, to the east, he pushed the frontiers of his empire by attacking Iran in 1535 and occupying Iraq and the Persian cities of Tabriz and Hamedan.[23] Furthermore, the exploits of the Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa included the conquest of Tunis and Algeria.[17] Following Suleiman's death, Ottoman victories continued, albeit less frequently than before. The island of Cyprus was conquered, in 1571, bolstering Ottoman dominance over the sea routes of the eastern Mediterranean.[24] However, after its defeat at the Battle of Vienna, in 1683, the Ottoman Empire started to stagnate. The army’s retreat was met by ambushes and further defeats, ending in the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz, which granted Austria the provinces of Hungary and Transylvania, and marked the first time in history that the Ottoman Empire actually relinquished territory.[25]

By the 19th century, the empire began to decline when ethno-nationalist uprisings occurred across the empire. Thus, the last quarter of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century saw some 7-9 million Turkish-Muslim refugees from the lost territories of the Caucasus, Crimea, Balkans, and the Mediterranean islands migrated to Anatolia and Eastern Thrace.[26] When World War I broke out, the Turks scored some success with Mustafa Kemal Pasha's legendary defence of Gallipoli at the Battle of the Dardanelles in 1915. However, in 1918, the Turks, represented by the Committee of Union and Progress, agreed to an armistice with England and France. The Treaty of Sèvres was signed in 1920 by the government of Mehmet VI which dismantled the Ottoman Empire. The Turks, under Mustafa Kemal, refused to accept the conditions of the treaty and fought for the Turkish War of Independence, resulting in the abolition of the Sultanate; thus, the 623-year old Ottoman Empire had come to an end.[27]

Modern era[edit]

Once Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led the Turkish War of Independence against the Allied Forces which were occupying the former Ottoman Empire, Atatürk united the Turkish-Muslim majority and successfully led them from 1919-22 in throwing the occupying forces out of what was considered to be the Turkish homeland.[28] The Turkish identity became the unifying force when, in 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed and the newly founded Republic of Turkey was formally established. Atatürk's 15-year rule was marked by a series of radical reforms in order to transform Turkey into a secular, modern republic.[29] Throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, Turks, as well as other Muslims, from the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Aegean islands, the island of Cyprus, the Sanjak of Alexandretta (Hatay), the Middle East, and the Soviet Union arrived in Turkey.[30] The bulk of these immigrants were the Balkan Turks who faced harassment and discrimination in their homelands.[30] Nonetheless, there were still remnants of a Turkish population in many of these countries, which the Turks had previously ruled, because the Turkish government wanted to preserve the Turkish communities in these regions so that the Turkish character of these neighbouring territories could be maintained.[31]

Traditional areas of Turkish settlement[edit]

Turkey[edit]

Ethnic Turks make up between 70% to 90% of Turkey's population.[32][33]

Balkans[edit]

| Turkish colonization in the Balkans | |||||||

| Region colonized | Ottoman conquest and year of Turkish settlement |

Name of Turkish community | Current status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosnia | 1463 | Bosnian Turks | The 1991 Bosnian census showed that there was a minority of 267 Turks.[34] However current estimates suggest that there is actually 50,000 Turks living in the country.[35] | ||||

| Bulgaria | 1396 | Bulgarian Turks | In the 2011 Bulgarian census, which census did not receive a response regarding ethnicity by the total population, 588,318 people, or 8.8% of the self-appointed, determined their ethnicity as Turkish;[36] while the latest census which provided answers from the entire population - the 2001 census, recorded 746,664 Turks, or 9.4% of the population.[37] Other estimates suggests that there are 750,000[38] to up to around 1 million Turks in the country.[39] | ||||

| Croatia | 1526 | Croatian Turks | According to the 2001 Croatian census the Turkish minority numbered 300.[40] More recent estimates have suggested that there are 2,000 Turks in Croatia.[41] | ||||

| Rhodes (in Greece) Kos (in Greece) |

1523 | Dodecanese Turks | Some 5,000 Turks live in the Dodecanese islands of Rhodes and Kos.[42] | ||||

| Kosovo | 1389 | Kosovan Turks[43] | There is approximately 50,000 Kosovo Turks living in the country, mostly in Mamuša, Prizren, and Priština.[35] | ||||

| Macedonia | 1392 | Macedonian Turks[44] | The 2002 Macedonian census states that there was 77,959 Macedonian Turks, forming about 4% of the total population and constituting a majority in Centar Župa and Plasnica.[45] However, academic estimates suggest that they actually number between 170,000-200,000.[38][46] Furthermore, about 200,000 Macedonian Turks have migrated to Turkey during WWI and WWII due to persecutions and discrimination[47] | ||||

| Moena (in Italy) | Never conquered by the Ottomans, though settlement began during the Siege of Vienna | Moena Turks | During the Battle of Vienna, in 1683, Turkish soldiers who fled to the south arrived in Moena.[48] Thus, today there is still a community who trace their roots to the Ottoman Turks. Moena is often called "Rione Turchia" which means "Turkish district/region".[49] | ||||

| Montenegro | 1496 | Montenegrin Turks | There were 104 Montenegrin Turks according to the 2011 census.[50] The majority left their homes and migrated to Turkey in th 1900s.[51] | ||||

| Dobruja (in Romania) | 1388 | Romanian Turks[52] | There were 28,226 Romanian Turks living in the country according to the 2011 Romanian census.[53] However, academic estimates suggest that the community numbers between 55,000[35][54] and 80,000.[55] | ||||

| Western Thrace (in Greece) | 1354 | Western Thrace Turks | The Greek government refers to the community as "Greek Muslims" or "Hellenic Muslims" and denies the existence of a Turkish minority in Western Thrace.[56] Traditionally, academics have suggeted that the Western Thrace Turks number about 120,000-130,000,[56] although more recent estimates suggest that the community numbers 150,000.[57] Between 300,000 to 400,000 have immigrated to Turkey since 1923.[58] | ||||

Cyprus[edit]

The Turkish Cypriots are the ethnic Turks whose Ottoman Turkish forbears colonised the island of Cyprus in 1571. About 30,000 Turkish soldiers were given land once they settled in Cyprus, which bequeathed a significant Turkish community. In 1960, a census was conducted by the new Republic's government which revealed that the Turkish Cypriots formed 18.2% of the islands population.[59] However, once inter-communal fighting and ethnic tensions between 1963 and 1974 occurred between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots, known as the "Cyprus conflict", the Greek Cypriot government conducted a census in 1973, albeit without the Turkish Cypriot populace. A year later, in 1974, the Cypriot government’s Department of Statistics and Research estimated the Turkish Cypriot population to be 118,000 (or 18.4%).[60] A coup d'état in Cyprus on 15 July 1974 by Greek and Greek Cypriots favouring union with Greece (also known as "Enosis") was followed by military intervention by Turkey whose troops established Turkish Cypriot control over the northern part of the island.[61] Hence, census's conducted by the Republic of Cyprus have excluded the Turkish Cypriot population which had been settled in the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.[60] Between 1975 and 1981, Turkey encouraged its own citizens to settle in Northern Cyprus; a 2010 report by the International Crisis Group suggests that out of the 300,000 residents living in Northern Cyprus perhaps half were either born in Turkey or are children of such settlers.[62]

Levant[edit]

| Turkish colonization in the Levant | |||||||

| Region colonized | Ottoman conquest and year of Turkish settlement |

Name of Turkish community | Current status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 1534 | Iraqi Turks | The Turks of Iraq are often called "Iraqi Turkmens" or "Iraqi Turcomans" because there has been various Turkic migrations to Iraq which began as early as the 7th century. However, most of today's descendants of these first migrants have been assimilated into the local Arab population.[63] Once Suleiman the Magnificent conquered Iraq in 1534, followed by Sultan Murad IV's capture of Baghdad in 1638, a large influx of Turks settled down in the region.[64][65][66] Thus, most of today's Iraqi Turkmen are the descendants of the Ottoman soldiers, traders and civil servants who were brought into Iraq during the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[67][68][64][66] | ||||

| Jordan | 1516 | Jordanian Turks | There exists a small minority of about 5,000 people in the country who are the descendants of the Ottoman-Turkish colonisers.[69] | ||||

| Lebanon | 1516 | Lebanese Turks | The Turkish community in Lebanon currently numbers about 80,000.[70] Turks were brought into the region along with Sultan Selim I’s army during his campaign to Egypt. The descendants of these early Ottoman Turkish settlors mainly live in Akkar and Baalbeck.[71] Late Ottoman-Turkish migration continued when the Ottoman Empire lost its dominion over the island of Crete, in modern-day Greece.[72] After 1897, when the Ottomans lost control of the island, the Ottoman Empire sent ships to protect the island’s Cretan Turks, most settled in Izmir and Mersin, but some of them were also sent to Tripoli, Lebanon.[72] | ||||

| Syria | 1516 | Syrian Turks | The Turks of Syria are often called "Syrian Turkmens" or "Syrian Turcomans" because there has been various Turkic migrations to Syria which began as early as the 7th century. However, most of today's descendants of these first migrants have been assimilated into the local Arab population. In 1516 Sultan Selim I conquered Syria and the region was part of the Ottoman Empire until 1918.[73] Hence, during the 402 years of Ottoman-Turkish rule, Turks migrated from Anatolia to Syria for centuries, establishing themselves as a significant community.[74] Today, there is about 1.5 million Turks living in Syria who still speak Turkish, although about a further 2 million are believed to be assimilated within the Arab population.[75] | ||||

Meskhetia[edit]

The Meskhetian Turks are the ethnic Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti region of Georgia, along the border with Turkey. The Turkish presence in Meskhetia began with the Ottoman invasion of 1578,[76] although Turkic tribes had settled in the region as early as the eleventh and twelfth centuries.[76] Today, the Meskhetian Turks are widely dispersed throughout the former Soviet Union (as well as in Turkey and the United States) due to forced deportations during World War II. At the time, the Soviet Union was preparing to launch a pressure campaign against Turkey and Joseph Stalin wanted to clear the strategic Turkish population in Meskheti who were likely to be hostile to Soviet intentions.[77] In 1944, the Meskhetian Turks were accused of smuggling, banditry and espionage in collaboration with their kin across the Turkish border;[78] nationalistic policies at the time encouraged the slogan: "Georgia for Georgians" and that the Meskhetian Turks should be sent to Turkey "where they belong".[79][80] Approximately 115,000 Meskhetian Turks were deported to Central Asia and only a few hundred have been able to return to Georgia ever since.[79]

North Africa[edit]

| Turkish colonization in North Africa | |||||||

| Region colonized | Ottoman conquest and year of Turkish settlement |

Name of Turkish community | Current status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 1517 | Algerian Turks | Estimates on the Algerian Turkish community vary significantly, according to the Turkish Embassy in Algeria there is between 600,000 to 2 million people of Turkish origin living in Algeria.[81] The Oxford Business Group has suggested that people of Turkish descent make up 5% of Algeria's total population, accounting to about 1.7 million.[82] However, other estimates state that the Turkish community make up 10-25% of Algeria's population.[83][84] | ||||

| Egypt | 1517 | Egyptian Turks | About 100,000 Turks are still living in Egypt.[85] | ||||

| Libya | 1551 | Libyan Turks | In 1936 there was 35,000 Turks living in Libya, forming about 5% of the total population at the time.[86] | ||||

| Tunisia | 1574 | Tunisian Turks | As much as 25% of Tunisia's population are of Turkish origin.[84] | ||||

Modern diaspora[edit]

Europe[edit]

Current estimates suggests that there is approximately 9 million Turks living in Europe, excluding those who live in Turkey.[87] Modern immigration of Turks to Western Europe began with Turkish Cypriots migrating to the United Kingdom in the early 1920s when the British Empire annexed Cyprus in 1914 and the residents of Cyprus became subjects of the Crown. However, Turkish Cypriot migration increased significantly in the 1940s and 1950s due to the Cyprus conflict. Conversely, in 1944, Turks who were forcefully deported from Meskheti in Georgia during the Second World War, known as the Meskhetian Turks, settled in Eastern Europe (especially in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine). By the early 1960s, migration to Western and Northern Europe increased significantly from Turkey when Turkish "guest workers" arrived under a "Labour Export Agreement" with Germany in 1961, followed by a similar agreement with the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria in 1964; France in 1965; and Sweden in 1967.[88][89][90] More recently, Bulgarian Turks, Romanian Turks, and Western Thrace Turks have also migrated to Western Europe.

North America[edit]

Compared to Turkish immigration to Europe, migration to North America has been relatively small. According to the 2000 United States Census and the 2006 Canadian Census, 117,575 Americans[91] and 43,700 Canadians[92] claimed Turkish descent. However, the actual number of Turks in both countries is considerably larger, as a significant number of ethnic Turks have migrated to North America not just from Turkey but also from the Balkans (such as Bulgaria and Macedonia), Cyprus, and the former Soviet Union.[93] Hence, the Turkish American community is currently estimated to number about 500,000[94][95] whilst the Turkish Canadian community is believed to number between 50,000-100,000.[96][97] The largest concentration of Turkish Americans are in New York City, and Rochester, New York; Washington, D.C.; and Detroit, Michigan. The majority of Turkish Canadians live in Ontario, mostly in Toronto, and there is also a sizable Turkish community in Montreal. With regards to the 2010 United States Census, the U.S government was determined to get an accurate count of the American population by reaching segments, such as the Turkish community, that are considered "hard to count", a good portion of which falls under the category of foreign-born immigrants.[98] The Assembly of Turkish American Associations and the US Census Bureau formed a partnership to spearhead a national campaign to count people of Turkish origin with an organisation entitled "Census 2010 SayTurk" (which has a double meaning in Turkish, "Say" means "to count" and "to respect") to identify the estimated 500,000 Turks now living in the United States.[98]

Oceania[edit]

A notable scale of Turkish migration to Australia began in the late 1940s when Turkish Cypriots began to leave the island of Cyprus for economic reasons, and then, during the Cyprus conflict, for political reasons, marking the beginning of a Turkish Cypriot immigration trend to Australia.[99] The Turkish Cypriot community were the only Muslims acceptable under the White Australia Policy;[100] many of these early immigrants found jobs working in factories, out in the fields, or building national infrastructure.[101] In 1967, the governments of Australia and Turkey signed an agreement to allow Turkish citizens to immigrate to Australia.[102] Prior to this recruitment agreement, there were less than 3,000 people of Turkish origin in Australia.[103] According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, nearly 19,000 Turkish immigrants arrived from 1968-1974.[102] They came largely from rural areas of Turkey, approximately 30% were skilled and 70% were unskilled workers.[104] However, this changed in the 1980s when the number of skilled Turks applying to enter Australia had increased considerably.[104] Over the next 35 years the Turkish population rose to almost 100,000.[103] More than half of the Turkish community settled in Victoria, mostly in the north-western suburbs of Melbourne.[103] According to the 2006 Australian Census, 59,402 people claimed Turkish ancestry;[105] however, this does not show a true reflection of the Turkish Australian community as it is estimated that between 40,000 to 60,000 Turkish Cypriots[106][107][108] and 150,000 to 200,000 mainland Turks[109][110] live in Australia. Furthermore, there has also been ethnic Turks who have migrated to Australia from Bulgaria,[111] Greece,[112] Iraq,[113] and the Republic of Macedonia.[112]

Former Soviet Union[edit]

On 15 November 1944, the then President of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, ordered the deportation of over 115,000 Meskhetian Turks from their homeland,[114] and were secretly driven from their homes and herded onto rail cars, thousands of which died of hunger, thirst and cold as a direct result of the deportations and the deprivations suffered in exile.[115][116] As opposed to the other nationalities who had been deported during WWII, no reason was given for the deportation of the Meskhetian Turks, which remained secret until 1968.[77] The Soviet government finally recognised that the Meskhetian Turks had been deported in 1968 and the reason for the deportation was because, in 1944, the Soviet Union was preparing to launch a pressure campaign against Turkey.[77] In June 1945 Vyacheslav Molotov, who was then Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented a demand to the Turkish Ambassador in Moscow for the surrender of three Anatolia provinces (Kars, Ardahan and Artvin).[77] As Moscow was also preparing to support Armenian claims to several other Anatolian provinces, war against Turkey seemed possible, and Joseph Stalin wanted to clear the strategic Georgian-Turkish border where the Meskhetian Turks were settled and who were likely to be hostile to such Soviet intentions.[77] According to the 1989 Soviet Census, 106,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Uzbekistan, 50,000 in Kazakhstan, and 21,000 in Kyrgyzstan.[114] However, in 1989, the Meshetian Turks who had settled in Uzbekistan became the target of a pogrom in the Fergana valley, which was the principal destination for Meskhetian Turkish deportees, after an uprising of nationalism in Uzbekistan.[114] The riots had left hundreds of Meskhetian Turks dead or injured and nearly 1,000 properties were destroyed and thousands of Meskhetian Turks were forced into renewed exile.[114] The majority of Meskhetian Turks, about 70,000, went to Azerbaijan, whilst the remainder went to various regions of Russia (especially Krasnodar Krai), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine.[114][117] Soviet authorities recorded many Meskhetian Turks as belonging to other nationalities such as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[114][118] Hence, official census's have not shown a true reflection of the Turkish population; for example, according to the 2009 Azerbaijani census, there were 38,000 Turks living in the country;[119] yet in 1999, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees stated that there were 100,000 Meskhetian Turks living in the country.[120] Furthermore, in 2001, the Baku Institute of Peace and Democracy suggested that there was between 90,000 to 110,000 Meskhetian Turks living in Azerbaijan.[121]

Language[edit]

The Turkish language is natively spoken by the Turkish people in Turkey, Bulgaria, the island of Cyprus, Greece (primarily in Western Thrace), Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia, Meskhetia, Romania, and other areas of traditional settlement which were formerly (in whole or part) belonged to the Ottoman Empire. Turkish is the official language of Turkey and is one of the official languages of Cyprus. It also has official (but not primary) status in the Prizren District of Kosovo and several municipalities of the Republic of Macedonia, depending on the concentration of Turkish-speaking local population. Modern standard Turkish is based on the dialect of Istanbul.[122] Nonetheless, dialectal variation persists, in spite of the levelling influence of the standard used in mass media and the Turkish education system since the 1930s.[123] The terms ağız or şive are often used to refer to the different types of Turkish dialects (such as Cypriot Turkish).

Anatolian Turkish dialects[edit]

There are three major Anatolian Turkish dialect groups spoken in Turkey: the West Anatolian dialect (roughly to the west of the Euphrates), the East Anatolian dialect (to the east of the Euphrates), and the North East Anatolian group, which comprises the dialects of the Eastern Black Sea coast, such as Trabzon, Rize, and the littoral districts of Artvin.[124][125]

Balkan Turkish dialects[edit]

The Turkish language was introduced to the Balkans by Turkish colonists during the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[126] Today, Turkish is still spoken by the Turkish minorities who are still living in the region, especially in Bulgaria, Greece (mainly in Western Thrace), Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia, and Romania.[127] Despite some contact phenomena, especially in the lexicon, the Balkan Turkish dialects are considerably closer to standard Turkish and do not differ significantly from it.[128]

Cypriot Turkish dialect[edit]

The Turkish language was introduced to Cyprus with the Ottoman conquest in 1571 and became the politically dominant, prestigious language, of the administration.[129] In the post-Ottoman period, Cypriot Turkish was relatively isolated from standard Turkish and had strong influences by the Cypriot Greek dialect. The condition of coexistence with the Greek Cypriots led to a certain bilingualism whereby Turkish Cypriots knowledge of Greek was important in areas where the two communities lived and worked together.[130] The linguistic situation changed radically in 1974, when the island was divided into a Greek south and a Turkish north (Northern Cyprus). Today, the Cypriot Turkish dialect is being exposed to increasing standard Turkish through immigration from Turkey, new mass media, and new educational institutions.[129]

Meskhetian Turkish dialect[edit]

The Meskhetian Turks speak an Eastern Anatolian dialect of Turkish, which hails from the regions of Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin.[131] The Meskhetian Turkish dialect has also borrowed from other languages (including Azerbaijani, Georgian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek) which the Meskhetian Turks have been in contact with during the Russian and Soviet rule.[131]

Turkish within the diaspora[edit]

Due to a large Turkish diaspora, significant Turkish-speaking communities also reside in countries such as Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, El Salvador, Finland, France, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[132] However, because of cultural assimilation of Turkish immigrants and their descendants in host countries, not all ethnic Turks speak the Turkish language with native fluency.[133]

Religion[edit]

References and notes[edit]

- ^ Bainbridge 2009, 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leiser 2005, 837.

- ^ Stokes & Gorman 2010, 707.

- ^ Findley 2005, 21.

- ^ Abazov 2009, 15.

- ^ a b Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 192.

- ^ Chaurasia 2005, 181.

- ^ Bainbridge 2009, 33.

- ^ a b c d e Darke 2011, 16.

- ^ Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 193.

- ^ a b c d e Ágoston 2010, xxv.

- ^ Somel 2003, 266.

- ^ Kia 2011, 1.

- ^ Fleet 1999, 5.

- ^ Kia 2011, 2.

- ^ a b Köprülü 1992, 110.

- ^ a b c Ágoston 2010, xxvi.

- ^ a b Fleet 1999, 6.

- ^ Eminov 1997, 27.

- ^ Kermeli 2010, 111.

- ^ Kia 2011, 5.

- ^ Quataert 2000, 21.

- ^ Kia 2011, 6.

- ^ Quataert 2000, 24.

- ^ Levine 2010, 28.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 5-6.

- ^ Levine 2010, 29.

- ^ Göcek 2011, 22.

- ^ Göcek 2011, 23.

- ^ a b Çaǧaptay 2006, 82.

- ^ Çaǧaptay 2006, 84.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CIATurkeywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Zeytinoğlu, Bonnabeau & Eşkinat 2012, 264.

- ^ Federal Office of Statistics. "Population grouped according to ethnicity, by censuses 1961-1991". Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Sosyal 2011 loc=368was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2011). "2011 Census (Final data)". National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. p. 4.

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2001). "2001 Census". National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Sosyal 2011 loc=369was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Novinite. "Scientists Raise Alarm over Apocalyptic Scenario for Bulgarian Ethnicity". Retrieved 2011-07-21.

- ^ Croatian Bureau of Statistics. "POPULATION BY ETHNICITY, BY TOWNS/MUNICIPALITIES, CENSUS 2001". Croatian Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ Zaman. "Altepe'den Hırvat Müslümanlara moral". Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Clogg 2002 loc=84was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Elsie 2010, 276.

- ^ Evans 2010, 11.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office 2005 loc=34was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Abrahams 1996 loc=53was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Evans 2010, 228.

- ^ Visintainer 2011, 7.

- ^ Visintainer 2011, 6.

- ^ Statistical Office of Montenegro. "Population of Montenegro by sex, type of settlement, etnicity, religion and mother tongue, per municipalities" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Todays Zaman. "Turks in Montenegrin town not afraid to show identity anymore". Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Brozba 2010, 48.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Romanian National Institute of Statistics 2011 loc=10was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Phinnemore 2006 loc=157was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Constantin et al 2006 loc=59was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Whitman 1990 loc=iwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ergener & Ergener 2002 loc=106was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Whitman 1990, 2.

- ^ Hatay 2007, 22.

- ^ a b Hatay 2007, 23.

- ^ United Nations. "UNFICYP: United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus". United Nations.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

International Crisis Group 2010 loc=2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Taylor 2004, 30.

- ^ a b Taylor 2004, 31.

- ^ Stansfield 2007, 70.

- ^ a b Jawhar 2010, 314.

- ^ International Crisis Group 2008, 16.

- ^ Library of Congress, Iraq: Other Minorities, Library of Congress Country Studies, retrieved 2011-11-24

- ^ Yeni Asya. "Osmanlı devlet geleneği yaşatılıyor". Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Al-Akhbarwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Orhan 2010, 8.

- ^ a b Orhan 2010, 13.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 6.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 7.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 8.

- ^ a b Aydıngün et al. 2006, 4.

- ^ a b c d e Bennigsen & Broxup 1983, 30.

- ^ Tomlinson 2005, 107.

- ^ a b Kurbanov & Kurbanov 1995, 237.

- ^ Cornell 2001, 183.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Turkish Embassy in Algeria 2008 loc=4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

OBG 2008 loc=10was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Zaman. "Türk'ün Cezayir'deki lakabı: Hıyarunnas!". Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ a b Hizmetli 1953, 10.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Baedeker 2000 loc=lviiiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pan 1949, 103.

- ^ Sosyal 2011, 367.

- ^ Akgündüz 2008, 61.

- ^ Kasaba 2008, 192.

- ^ Twigg et al. 2005, 33.

- ^ Unites States Census Bureau. "Ancestry: 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ Statistics Canada. "2006 Census". Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Karpat 2004 loc=627was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Farkas 2003 loc=40was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

EncyclopediaofClevelandHistorywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

TurkishEmbassyCanadawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ZamanCanadawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

WashingtonDiplomatwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hüssein 2007, 17

- ^ Cleland 2001, 24

- ^ Hüssein 2007, 19

- ^ a b Hüssein 2007, 196

- ^ a b c Hopkins 2011, 116

- ^ a b Saeed 2003, 9

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

2006AustralianCensuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

TRNCMinistryofForeignAffairswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

KibrisGazetesiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

BRTwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Old foes, new friends". Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-04-23. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ^ "Avustralyalı Türkler'den, TRT Türk'e tepki". Milliyet. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2006). "Community Information Summary:Bulgaria" (PDF). Australian Government. p. 2.

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics. "2006 Census Ethnic Media Package". Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^ Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2006). "Community Information Summary:Iraq" (PDF). Australian Government. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f UNHCR 1999b, 20.

- ^ Polian 2004, 155.

- ^ Minahan 2002, 1240.

- ^ UNHCR 1999b, 21.

- ^ Aydıngün et al. 2006, 1.

- ^ The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. "Population by ethnic groups". Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ UNHCR 1999a, 14.

- ^ NATO Parliamentary Assembly. "Minorities in the South Caucasus: Factor of Instability?". Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ Campbell 2008, 547.

- ^ Johanson 2001, 16.

- ^ Brendemoen 2002, 27.

- ^ Brendemoen 2006, 227.

- ^ Johanson 2011, 732.

- ^ Johanson 2011, 734-738.

- ^ Friedman 2003, 51.

- ^ a b Johanson 2011, 738.

- ^ Johanson 2011, 739.

- ^ a b Aydıngün et al. 2006, 23.

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Report for language code:tur (Turkish)". Retrieved 2011-09-04.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johanson 2011, 734.

Bibliography[edit]

- Abadan-Unat, Nermin (2011), Turks in Europe: From Guest Worker to Transnational Citizen, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-84545-425-1.

- Abazov, Rafis (2009), Culture and Customs of Turkey, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313342156.

- Abrahams, Fred (1996), A Threat to "Stability": Human Rights Violations in Macedonia, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 1-56432-170-3.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2010), "Introduction", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 1438110251.

- Akgündüz, Ahmet (2008), Labour migration from Turkey to Western Europe, 1960-1974: A multidisciplinary analysis, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-7390-1.

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006), Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences (PDF), Center for Applied Linguistics

- Baedeker, Karl (2000), Egypt, Elibron, ISBN 1402197055.

- Bainbridge, James (2009), Turkey, Lonely Planet, ISBN 174104927X.

- Baran, Zeyno (2010), Torn Country: Turkey Between Secularism and Islamism, Hoover Press, ISBN 0817911448.

- Bennigsen, Alexandre; Broxup, Marie (1983), The Islamic threat to the Soviet State, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0619-6.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2002), The Turkish Dialects of Trabzon: Analysis, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447045701.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2006), "Ottoman or Iranian? An example of Turkic-Iranian language contact in East Anatolian dialects", in Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane (eds.), Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447052767.

- Brizic, Katharina; Yağmur, Kutlay (2008), "Mapping lingustic diversity in an emigration and immigration context: Case studies on Turkey and Austria", in Barni, Monica; Extra, Guus (eds) (eds.), Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts, Walter de Gruyter, p. 248, ISBN 3110207346

{{citation}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help). - Bruce, Anthony (2003), The Last Crusade. The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, John Murray, ISBN 0719565057.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006), Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0415384583.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006b), "Passage to Turkishness: immigration and religion in modern Turkey", in Gülalp, Haldun (ed.), Citizenship And Ethnic Conflict: Challenging the Nation-state, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0415368979.

- Campbell, George L. (1998), Concise Compendium of the World's Languages, Psychology Press, ISBN 0415160499.

- Seher, Cesur-Kılıçaslan; Terzioğlu, Günsel (2012), "Families Immigrating from Bulgaria to Turkey Since 1878", in Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert (eds.), Migration In, From, and to Southeastern Europe: Historical and Cultural Aspects, Volume 1, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 3643108958.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2005), History Of Middle East, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 8126904488.

- Clogg, Richard (2002), Minorities in Greece, Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-706-8.

- Constantin, Daniela L.; Goschin, Zizi; Dragusin, Mariana (2008), "Ethnic entrepreneurship as an integration factor in civil society and a gate to religious tolerance. A spotlight on Turkish entrepreneurs in Romania", Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, 7 (20): 28–41

- Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1162-7.

- Darke, Diana (2011), Eastern Turkey, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 1841623393.

- Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2012), World History, Cengage Learning, ISBN 1111831653.

- Elsie, Robert (2010), Historical Dictionary of Kosovo, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-7231-5.

- Eminov, Ali (1997), Turkish and other Muslim minorities in Bulgaria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-319-4.

- Ergener, Rashid; Ergener, Resit (2002), About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture, Pilgrims Process, ISBN 0971060967.

- Evans, Thammy (2010), Macedonia, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 1-84162-297-4.

- Farkas, Evelyn N. (2003), Fractured States and U.S. Foreign Policy: Iraq, Ethiopia, and Bosnia in the 1990s, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1403963738.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2005), Subjects Of The Sultan: Culture And Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1850437602.

- Findley, Carter V. (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195177266.

- Fleet, Kate (1999), European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of Genoa and Turkey, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521642213.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2003), Turkish in Macedonia and Beyond: Studies in Contact, Typology and other Phenomena in the Balkans and the Caucasus, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447046406.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2006), "Western Rumelian Turkish in Macedonia and adjacent areas", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Johanson, Lars (eds.), Turkic Languages in Contact, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447052120.

- Gogolin, Ingrid (2002), Guide for the Development of Language Education Policies in Europe: From Linguistic Diversity to Plurilingual Education (PDF), Council of Europe.

- Göcek, Fatma Müge (2011), The Transformation of Turkey: Redefining State and Society from the Ottoman Empire to the Modern Era, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1848856113.

- Hatay, Mete (2007), Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking? (PDF), International Peace Research Institute, ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9.

- Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (2010), Anthropology: The Human Challenge, Cengage Learning, ISBN 0-495-81084-3.

- Hizmetli, Sabri (1953), "Osmanlı Yönetimi Döneminde Tunus ve Cezayir'in Eğitim ve Kültür Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış" (PDF), Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 32 (0): 1–12

- Home Affairs Committee (2011), Implications for the Justice and Home Affairs area of the accession of Turkey to the European Union (PDF), The Stationery Office, ISBN 0-215-56114-7

- Hopkins, Liza (2011), "A Contested Identity: Resisting the Category Muslim-Australian", Immigrants & Minorities, 29 (1), Routledge: 110–131.

- Hüssein, Serkan (2007), Yesterday & Today: Turkish Cypriots of Australia, Serkan Hussein, ISBN 0-646-47783-8.

- İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2005), "Institutionalisation of Science in the Medreses of Pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Turkey", in Irzik, Gürol; Güzeldere, Güven (eds.), Turkish Studies in the History And Philosophy of Science, Springer, ISBN 140203332X.

- Ilican, Murat Erdal (2011), "Cypriots, Turkish", in Cole, Jeffrey (ed.), Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1598843028.

- International Crisis Group (2008), Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds: Conflict or Cooperation?, Middle East Report N°81 –13 November 2008: International Crisis Group

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - International Crisis Group (2010). "Cyprus: Bridging the Property Divide". International Crisis Group..

- Jawhar, Raber Tal’at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.) (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, pp. 313–328, ISBN 1-886604-75-4

{{citation}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help). - Johanson, Lars (2001), Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map (PDF), Stockholm: Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul

- Johanson, Lars (2011), "Multilingual states and empires in the history of Europe: the Ottoman Empire", in Kortmann, Bernd; Van Der Auwera, Johan (eds) (eds.), The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide, Volume 2, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110220253

{{citation}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help) - Kaplan, Robert D. (2002), "Who Are the Turks?", in Villers, James (ed.), Travelers' Tales Turkey: True Stories, Travelers' Tales, ISBN 1885211821.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2000), "Historical Continuity and Identity Change or How to be Modern Muslim, Ottoman, and Turk", in Karpat, Kemal H. (ed.), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 9004115625.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 9004133224.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2008), The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62096-1.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2009), A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0295989483.

- Kermeli, Eugenia (2010), "Byzantine Empire", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 1438110251.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2011), Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 0313064024.

- King Baudouin Foundation (2008), "Diaspora philanthropy – a growing trend", Turkish communities and the EU (PDF), King Baudouin Foundation

{{citation}}: Text "isbn" ignored (help). - Kirişci, Kemal (2006), "Migration and Turkey: the dynamics of state, society and politics", The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521620961

{{citation}}:|editor1-first=has generic name (help);|editor1-first=missing|editor1-last=(help); Unknown parameter|eitor1-last=ignored (help). - Knowlton, MaryLee (2005), Macedonia, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 0-7614-1854-7.

- Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (1992), The Origins of the Ottoman Empire, SUNY Press, ISBN 0791408205.

- Kötter, I; Vonthein, R; Günaydin, I; Müller, C; Kanz, L; Zierhut, M; Stübiger, N (2003), "Behçet's Disease in Patients of German and Turkish Origin- A Comparative Study", in Zouboulis, Christos (ed.) (ed.), Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Volume 528, Springer, ISBN 0-306-47757-2

{{citation}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help). - Kurbanov, Rafik Osman-Ogly; Kurbanov, Erjan Rafik-Ogly (1995), "Religion and Politics in the Caucasus", in Bourdeaux, Michael (ed) (ed.), The Politics of Religion in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-357-1

{{citation}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help). - Laczko, Frank; Stacher, Irene; von Koppenfels, Amanda Klekowski (2002), New challenges for Migration Policy in Central and Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 187, ISBN 906704153X.

- Leiser, Gary (2005), "Turks", in Meri, Josef W. (ed.), Medieval Islamic Civilization, Routledge, ISBN 0415966906.

- Leveau, Remy; Hunter, Shireen T. (2002), "Islam in France", in Hunter, Shireen (ed.), Islam, Europe's Second Religion: The New Social, Cultural, and Political Landscape, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0275976092.

- Levine, Lynn A. (2010), Frommer's Turkey, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0470593660.

- Minahan, James (2002), Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32111-6.

- Orhan, Oytun (2010), The Forgotten Turks: Turkmens of Lebanon (PDF), ORSAM.

- OSCE (2010), "Community Profile: Kosovo Turks", Kosovo Communities Profile, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

- Oxford Business Group (2008), The Report: Algeria 2008, Oxford Business Group, ISBN 1-902339-09-6

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help). - Özkaya, Abdi Noyan (2007), "Suriye Kürtleri: Siyasi Etkisizlik ve Suriye Devleti'nin Politikaları" (PDF), Review of International Law and Politics, 2 (8).

- Öztürkmen, Ali; Duman, Bilgay; Orhan, Oytun (2011), Suriye'de değişim ortaya çıkardığı toplum: Suriye Türkmenleri (PDF), ORSAM.

- Pan, Chia-Lin (1949), "The Population of Libya", Population Studies, 3 (1): 100–125

- Park, Bill (2005), Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-38297-1

- Phillips, David L. (2006), Losing Iraq: Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-05681-4

- Phinnemore, David (2006), The EU and Romania: Accession and Beyond, The Federal Trust for Education & Research, ISBN 1-903403-78-2.

- Polian, Pavel (2004), Against Their will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR, Central European University Press, ISBN 963-9241-68-7.

- Quataert, Donald (2000), The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521633281.

- Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office (2005), Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002 (PDF), Republic of Macedonia - State Statistical Office

- Romanian National Institute of Statistics (2011), Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011 (PDF), Romania-National Institute of Statistics

- Ryazantsev, Sergey V. (2009), "Turkish Communities in the Russian Federation" (PDF), International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 11 (2): 155–173.

- Saeed, Abdullah (2003), Islam in Australia, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 1-86508-864-1.

- Saunders, John Joseph (1965), "The Turkish Irruption", A History of Medieval Islam, Routledge, ISBN 0415059143.

- Scarce, Jennifer M. (2003), Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, Routledge, ISBN 0700715606.

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey Volume 1 , Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521291631.

- Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2003), Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0810843323.

- Sosyal, Levent (2011), "Turks", in Cole, Jeffrey (ed.), Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1598843028.

- Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2007), Iraq: People, History, Politics, Polity, ISBN 0-7456-3227-0.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000), The Balkans Since 1453, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1850655510.

- Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, Anthony (2010), "Turkic Peoples", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 143812676X.

- Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps Books, ISBN 1-895896-26-6.

- Tomlinson, Kathryn (2005), "Living Yesterday in Today and Tomorrow: Meskhetian Turks in Southern Russia", in Crossley, James G.; Karner, Christian (eds.) (eds.), Writing History, Constructing Religion, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-5183-5

{{citation}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help). - Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Twigg, Stephen; Schaefer, Sarah; Austin, Greg; Parker, Kate (2005), Turks in Europe: Why are we afraid? (PDF), The Foreign Policy Centre, ISBN 978 1 903558 79 4

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - UNHCR (1999), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Azerbaijan (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- UNHCR (1999b), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Georgia (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Visintainer, Ermanno (2011), İtalya'da Unutulmuş Türk Varlığı: Moena Türkleri (PDF), ORSAM.

- Whitman, Lois (1990), Destroying ethnic identity: the Turks of Greece, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 0-929692-70-5.

- Zeytinoğlu, Güneş N.; Bonnabeau, Richard F.; Eşkinat, Rana (2012), "Ethnopolitical Conflict in Turkey: Turkish Armenians: From Nationalism to Diaspora", in Landis, Dan; Albert, Rosita D. (eds.), Handbook of Ethnic Conflict: International Perspectives, Springer, ISBN 1461404479.