Lysine: Difference between revisions

→Clinical significance: +deficiency |

→Clinical significance: typo |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

While chemically insignificant to lysine itself, it is worth noting that lysine is attached to [[dextroamphetamine]] to form the [[prodrug]] [[lisdexamfetamine]] (Vyvanse). In the [[gastrointestinal tract]], the lysine molecule is cleaved from the dextroamphetamine, thereby making oral administration necessary. |

While chemically insignificant to lysine itself, it is worth noting that lysine is attached to [[dextroamphetamine]] to form the [[prodrug]] [[lisdexamfetamine]] (Vyvanse). In the [[gastrointestinal tract]], the lysine molecule is cleaved from the dextroamphetamine, thereby making oral administration necessary. |

||

According to animal studies, lysine deficiency causes [[immunodeficiency]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Chen C, Sander JE, Dale NM |title=The effect of dietary lysine deficiency on the immune response to Newcastle disease vaccination in chickens |journal=Avian Dis. |volume=47 |issue=4 |pages=1346–51 |year=2003 |pmid=14708981 |doi= |url=}}</ref> One cause of relative lysine deficiency is [[cystinuria]], where there |

According to animal studies, lysine deficiency causes [[immunodeficiency]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Chen C, Sander JE, Dale NM |title=The effect of dietary lysine deficiency on the immune response to Newcastle disease vaccination in chickens |journal=Avian Dis. |volume=47 |issue=4 |pages=1346–51 |year=2003 |pmid=14708981 |doi= |url=}}</ref> One cause of relative lysine deficiency is [[cystinuria]], where there is impaired intestinal uptake of basic, or positively charged amino acids, including lysine. The accompanying urinary cysteine results from that the same deficient amino acid transporter is normally present in the kidney as well. |

||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

Revision as of 02:24, 7 July 2010

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lysine

| |||

| Other names

2,6-diaminohexanoic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.673 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H14N2O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 146.190 g·mol−1 | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Lysine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Lysine (abbreviated as Lys or K)[1] is an α-amino acid with the chemical formula HO2CCH(NH2)(CH2)4NH2. This amino acid is an essential amino acid, which means that the human body cannot synthesize it. Its codons are AAA and AAG.

Lysine is a base, as are arginine and histidine. The ε-amino group often participates in hydrogen bonding and as a general base in catalysis. Common posttranslational modifications include methylation of the ε-amino group, giving methyl-, dimethyl-, and trimethyllysine. The latter occurs in calmodulin. Other posttranslational modifications at lysine residues include acetylation and ubiquitination. Collagen contains hydroxylysine which is derived from lysine by lysyl hydroxylase. O-Glycosylation of lysine residues in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus is used to mark certain proteins for secretion from the cell.

Biosynthesis

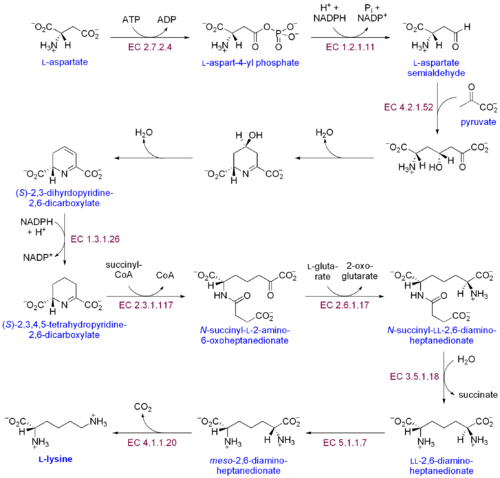

As an essential amino acid, lysine is not synthesized in animals, hence it must be ingested as lysine or lysine-containing proteins. In plants and bacteria, it is synthesized from aspartic acid (aspartate):[2]

- L-aspartate is first converted to L-aspartyl-4-phosphate by Aspartokinase (or Aspartate kinase). ATP is needed as an energy source for this step.

- β-aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase converts this into β-aspartyl-4-semialdehyde (or β-aspartate-4-semialdehyde). Energy from NADPH is used in this conversion.

- Dihydrodipicolinate synthase adds a Pyruvate group to the β-aspartyl-4-semialdehyde, and two water molecules are removed. This causes cyclization and gives rise to 2,3-dihydrodipicolinate.

- This product is reduced to 2,3,4,5-tetrahydrodipicolinate (or Δ1-piperidine-2,6-dicarboxylate, in the figure: (S)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate) by Dihydrodipicolinate reductase. This reaction consumes a NADPH molecule.

- Tetrahydrodipicolinate N-acetyltransferase opens this ring and gives rise to N-succinyl-L-2-amino-6-oxoheptanedionate (or N-acyl-2-amino-6-oxopimelate). Two water molecules and one Acyl-CoA (Succinyl-CoA) enzyme are used in this reaction.

- N-succinyl-L-2-amino-6-oxoheptanedionate is converted into N-succinyl-LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (N-acyl-2,6-diaminopimelate). This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme Succinyl diaminopimelate aminotransferase. A Glutaric acid molecule is used in this reaction and an Oxoacid is produced as a byproduct.

- N-succinyl-LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (N-acyl-2,6-diaminopimelate)is converted into LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (L,L-2,6-diaminopimelate) by Succinyl diaminopimelate desuccinylase (Acyldiaminopimelate deacylase). A water molecule is consumed in this reaction and a succinate is produced a byproduct.

- LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate is converted by Diaminopimelate epimerase into meso-2,6-diamino-heptanedionate (meso-2,6-diaminopimelate).

- Finally meso-2,6-diamino-heptanedionate is converted into L-lysine by Diaminopimelate decarboxylase.

Enzymes involved in this biosynthesis include:[3]

- Aspartokinase

- β-aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase

- Dihydropicolinate synthase

- Δ1-piperidine-2,6-dicarboxylate dehydrogenase

- N-succinyl-2-amino-6ketopimelate synthase

- Succinyl diaminopimelate aminotransferase

- Succinyl diaminopimelate desuccinylase

- Diaminopimelate epimerase

- Diaminopimelate decarboxylase.

Metabolism

Lysine is metabolised in mammals to give acetyl-CoA, via an initial transamination with α-ketoglutarate. The bacterial degradation of lysine yields cadaverine by decarboxylation.

Allysine is a derivative of lysine, used in the production of elastin and collagen. It is produced by the actions of the enzyme lysyl oxidase on lysine in the extracellular matrix and is essential in the crosslink formation that stabilizes collagen and elastin.

Synthesis

Synthetic, racemic lysine has long been known.[4] A practical synthesis starts from caprolactam.[5] Industrially, L-lysine is usually manufactured by a fermentation process using Corynebacterium glutamicum; production exceeds 600,000 tons a year.[6]

Dietary sources

The human nutritional requirement is 1–1.5 g daily. It is the limiting amino acid (the essential amino acid found in the smallest quantity in the particular foodstuff) in all cereal grains, but is plentiful in all pulses (legumes). Foods that contain significant amounts of lysine include:[citation needed]

- Red meat (14,200–15,000 ppm)

- Eggs

- Buffalo Gourd (10,130–33,000 ppm) in seed

- Watercress (1,340–26,800 ppm) in herb.

- Soybean (24,290–26,560 ppm) in seed.

- Carob, Locust Bean, St.John's-Bread (26,320 ppm) in seed;

- Common Bean (Black Bean, Dwarf Bean, Field Bean, Flageolet Bean, French Bean, Garden Bean, Green Bean, Haricot, Haricot Bean, Haricot Vert, Kidney Bean, Navy Bean, Pop Bean, Popping Bean, Snap Bean, String Bean, Wax Bean) (2,390–25,700 ppm) in sprout seedling;

- Ben Nut, Benzolive Tree, Jacinto (Sp.), Moringa (aka Drumstick Tree, Horseradish Tree, Ben Oil Tree), West Indian Ben (5,370–25,165 ppm) in shoot.

- Lentil (7,120–23,735 ppm) in sprout seedling.

- Asparagus Pea, Winged Bean (aka Goa Bean) (21,360–23,304 ppm) in seed.

- Fat Hen (3,540–22,550 ppm) in seed.

- White Lupin (19,330–21,585 ppm) in seed.

- Black Caraway, Black Cumin, Fennel-Flower, Nutmeg-Flower, Roman Coriander (16,200–20,700 ppm) in seed.

- Pea (3,170–14,995 ppm) in seed.

- Spinach (1,740–20,664 ppm).

- Amaranth, Quinoa

- Buckwheat

- Mesquite.

Good sources of lysine are foods rich in protein including meat (specifically red meat, lamb, pork, and poultry), cheese (particularly Parmesan), certain fish (such as cod and sardines), and eggs.[7]

Properties

L-Lysine is a necessary building block for all protein in the body. L-Lysine plays a major role in calcium absorption; building muscle protein; recovering from surgery or sports injuries; and the body's production of hormones, enzymes, and antibodies.

Modifications

Lysine can be modified through acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, neddylation, biotinylation and carboxylation which tends to modify the function of the protein of which the modified lysine residue(s) are a part.[8]

Clinical significance

It has been suggested that lysine may be beneficial for those with herpes simplex infections.[9] However, more research is needed to fully substantiate this claim. For more information, refer to Herpes simplex - Lysine.

There are Lysine conjugates that show promise in the treatment of cancer, by causing cancerous cells to destroy themselves when the drug is combined with the use of phototherapy, while leaving non-cancerous cells unharmed.[10]

While chemically insignificant to lysine itself, it is worth noting that lysine is attached to dextroamphetamine to form the prodrug lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse). In the gastrointestinal tract, the lysine molecule is cleaved from the dextroamphetamine, thereby making oral administration necessary.

According to animal studies, lysine deficiency causes immunodeficiency.[11] One cause of relative lysine deficiency is cystinuria, where there is impaired intestinal uptake of basic, or positively charged amino acids, including lysine. The accompanying urinary cysteine results from that the same deficient amino acid transporter is normally present in the kidney as well.

In popular culture

The 1993 film Jurassic Park, which is based on the 1990 Michael Crichton novel Jurassic Park, features dinosaurs that were genetically altered so they could not produce lysine.[12] This was known as the "lysine contingency," and was supposed to prevent the cloned dinosaurs from surviving outside the park, forcing them to be dependent on lysine supplements provided by the park's veterinary staff. Most vertebrates cannot produce lysine by default (it is an essential amino acid).

In 1996, lysine became the focus of a price fixing case, the largest in United States history. The Archer Daniels Midland Company paid a fine of US$100 million, and three of its executives were convicted and served prison time. Also found guilty in the price fixing case were two Japanese firms (Ajinomoto, Kyowa Hakko) and a South Korean firm (Sewon).[13] Secret video recordings of the conspirators fixing lysine's price can be found online or by requesting the video from the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division. This case served as the basis of the movie The Informant!, and a book of the same title.[14]

See also

References

- ^ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ Lysine biosynthesis and catabolism, Purdue University

- ^ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry" 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ^ Braun, J. V. “Synthese des inaktiven Lysins aus Piperidin" Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 1909, Volume 42, p 839-846. DOI: 10.1002/cber.190904201134.

- ^ Eck, J. C.; Marvel, C. S. “dl-Lysine Hydrochlorides” Organic Syntheses, Collected Volume 2, p.374 (1943). http://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV2P0374.pdf

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12523389, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12523389instead. - ^ University of Maryland Medical Center. "Lysine". Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ Sadoul K, Boyault C, Pabion M, Khochbin S (2008). "Regulation of protein turnover by acetyltransferases and deacetylases". Biochimie. 90 (2): 306–12. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2007.06.009. PMID 17681659.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Griffith RS, Norins AL, Kagan C. (1978). "A multicentered study of lysine therapy in Herpes simplex infection". Dermatologica. 156 (5): 257–267. doi:10.1159/000250926. PMID 640102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ScienceDaily. "Chemists Kill Cancer Cells With Light-activated Molecules". Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ Chen C, Sander JE, Dale NM (2003). "The effect of dietary lysine deficiency on the immune response to Newcastle disease vaccination in chickens". Avian Dis. 47 (4): 1346–51. PMID 14708981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (October 10, 1999). "The Truth Is Way Out There". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Connor, J.M.; "Global Price Fixing" 2nd Ed. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, 2008. ISBN 978-3-540-78669-6.

- ^ Eichenwald, Kurt.; "The Informant: a true story" Broadway Books: New York, 2000. ISBN 0-7679-0326-9.

Sources

- Much of the information in this article has been translated from German Wikipedia.

- Lide, D. R., ed. (2002). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (83rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0483-0.