Palestinians: Difference between revisions

→Intifada: Don't copy and paste from other articles. E.g. synthesise the main article. |

|||

| Line 233: | Line 233: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

<br /> |

<br /> |

||

The chart is based on [[B'Tselem]] casualty numbers.<ref name=casualties/> It does not include the 577 Palestinians killed by Palestinians.]] |

The chart is based on [[B'Tselem]] casualty numbers.<ref name=casualties/> It does not include the 577 Palestinians killed by Palestinians.]] |

||

<br />The '''First Intifada''' was [[Palestinian people|Palestinian]][[Rebellion|uprising]] against the [[Israel]]i occupation of the [[Palestinian Territorieslate 1987 until 1991-3, policies of deportation, confiscation of lands, and their settlement, and consisting of [[general strikes]], [[civil disobedience]] and [[boycott]]s of Israeli institutions and products. Stone-throwing was widespread. Israel adopted a policy of "breaking Palestinians' bones" to put down the revolt. In the conflict an estimated 1,100 Palestinian, and 16 Israeli citizens were killed, while many more were injured. Infra-communal conflict among Palestinians over collaboration also led to several hundred death killings. |

|||

<br />The '''First Intifada''' (also known as simply the "intifada" or intifadah{{ref|A|[note A]}}) was a violent but unarmed<ref>Robert A. Pape, James K. Feldman, ''Cutting the Fuse: The Explosion of Global Suicide Terrorism and How to Stop It,'' University of Chicago Press, 2010 p.221.'Palestinian resistance moved from unarmed violent rebellion with no use of suicide attacks in the First Intifada, to large-scale suicide bombings and rmed rebellion in the Second Intifada.'(p.237)</ref> [[Palestinian people|Palestinian]][[Rebellion|uprising]] against the [[Israel]]i occupation of the [[Palestinian Territories]],<ref name="LockmanBeinin1989_5">[[#LockmanBeinin1989|Lockman; Beinin (1989)]], p. [http://books.google.com/books?id=KYPVNdzXUJkC&pg=PA5&dq=%22the+palestinian+uprising+(intifada)+on+the+west_bank+and+gaza+is+said+to+have+begun+on+december+9+1987%225.]</ref> which lasted from December 1987 until the [[Madrid Conference]] in 1991, though some date its conclusion to 1993, with the signing of the [[Oslo Accords]].<ref>Nami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian ''intifadas'',' in David Newman, Joel Peters (eds.) ''Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,'' Routledge, 2013pp.56-67, p.56.</ref> The uprising began on December 9,<ref>Edward Said,'Intifada and Independence', in Zachery Lockman, Joel Beinin, (eds.) ''Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising Against Israeli Occupation,''South End Press, 1989 pp.5-22, p.5:'The Palestinian uprising (''intifada'') on the West Bank and Gaza is said to have begun on December 9, 1987'</ref> in the [[Jabalya Camp|Jabalia]] [[refugee camp]] after an army truck ploughed into a car killing four Palestinians,<ref>David McDowall,''Palestine and Israel: the uprising and beyond,''University of California Press, 1989 p.1</ref>and quickly spread throughout [[Gaza]], the [[West Bank]] and [[East Jerusalem]].<ref name="JMCC">[http://www.jmcc.org/research/reports/intifada.htm The Intifada - An Overview: The First Two Years][http://www.phrmg.org/monitor2001/oct2001-collaborators.htm Collaborators , One Year Al-Aqsa Intifada, Fact Sheets And Figures]</ref> In response to [[general strikes]], [[boycott]]s of Israeli civil administration institutions in the [[Gaza Strip]] and the West Bank, [[civil disobedience]] in the face of army orders,and an [[economic boycott]] consisting of refusal to work in [[Israeli settlements]] on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licences, [[graffiti]],[[barricade|barricading]],<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/middle_east/03/v3_ip_timeline/html/1987.stm BBC: A History of Conflict]</ref><ref>Walid Salem, 'Human Security from Below: Palestinian Citizens Protection Strrategies, 1988-2005 ,' in Monica den Boer, Jaap de Wilde |

|||

(eds.), ''The viability of human security,''Amsterdam University Press, 2008 pp.179-201 p.190.</ref> and widespread throwing of stones and [[Molotov cocktails]] at the Israeli military and its infrastructure within Palestinian territories, Israel deployed 80,000 soldiers to put down the uprising, and adopted a policy of "breaking Palestinians' bones" and using live ammunition against civilians. Over the first two years, according to [[Save the Children]], an estimated 7% of all Palestinians under 18 years of age suffered injuries from shootings, beatings or tear gas.<ref>Wendy Pearlman, ''Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement,''Cambridge University Press 2011, p.114.</ref> Intra-Palestinian violence was also prominent feature of the Intifada, with widespread executions of alleged Israeli [[Collaborationism|collaborators]]. |

|||

[[File:Intifada1990.jpg|thumb|First Intifada poster]] |

|||

[[Israeli Defense Forces]] killed an estimated 1,100 Palestinian civilians from 1989-1992 while for the same period Palestinians killed 16 Israeli civilians and 11 IDF soldiers in the [[Palestinian territories|Occupied Territories]], though more than 1,400 Israeli civilians and 1,700 soldiers were injured.<ref>'Intifada,' in David Seddon, (ed.)''A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East,''Taylor & Francis 2004, p.284.</ref> Palestinians also killed an estimated 822 other Palestinians as alleged collaborators (1988-April 1994),<ref>[[Human Rights Watch]], ''Israel, The Occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, and the Palestinian Authority Territories,''November, 2001. Vol. 13, No. 4(E), |

|||

p.49</ref> although fewer than half had any proven contact with the Israeli authorities.<ref name = phrmg/><ref name="LockmanBeinin1989_38">[[#LockmanBeinin1989|Lockman; Beinin (1989)]], p. [http://books.google.com/books?id=KYPVNdzXUJkC&pg=PA37-38.] (verify):'The most dramatic case of popular vengeance against a collaborator occurred in the village of Qabatya during the last week of February. During a demonstration by townspeople, a small boy threw a stone at the house of Muhammad Ayad, an alleged informer for Shin Bet, Israel's internal security service. Ayad responbded by opening fire on the crowd, killing a child. Villagers stormed the house several times; thirteen were wounded by gunfire. When Ayad's ammunition was exhausted, villagers entered the house and killed him with an ax. They dragged his body to the street, where virtually the entire village spat on it, including his relatives. His body was then hung on an electricity pylon, topped by two Palestinian flags.The next day, at a gathering in the mosque, four other collaborators handed their guns over to the ''mukhtar'' (the village leader), and formally apologized to the village. (Qabatya has been cordoned off ever since, and many residents seized)'</ref> |

|||

The ensuing [[Second Intifada]] took place from September 2000 to 2005. |

|||

[[Palestinians]] and their supporters regard the Intifada as a protest against Israeli repression including extrajudicial killings, mass detentions, house demolitions and deportations.<ref name="AckermanDuVall2000">[[#AckermanDuVall2000|Ackerman; DuVall (2000)]], p [http://books.google.com/books?id=OVtKS9DCN0kC&pg=PA403 403.]</ref> |

|||

After Israel's capture of the [[West Bank]], [[Jerusalem]], [[Sinai Peninsula]] and [[Gaza Strip]] from [[Jordan]] and [[Egypt]] in the[[Six-Day War]] in 1967, frustration grew among Palestinians in the [[Israeli-occupied territories]]. High birth rates in the[[Palestinian territories]] and the limited allocation of land for new building and agriculture created conditions marked by growing population density and rising unemployment, even for those with university degrees. At the time of the Intifada, only one in eight college-educated Palestinians could find degree-related work.<ref name="AckermanDuVall2000_401">[[#AckermanDuVall2000|Ackerman; DuVall (2000)]], p [http://books.google.com/books?id=OVtKS9DCN0kC&pg=PA401 401.]</ref> |

|||

The [[Israeli Labor Party]] 's [[Yitzhak Rabin]], the then [[Ministry of Defense (Israel)|Defense Minister]], added deportations in August 1985 to Israel's "Iron Fist" policy of cracking down on Palestinian nationalism.<ref>[[Helena Cobban]], 'The PLO and the Intifada', in Robert Owen Freedman, (ed.) ''The Intifada: its impact on Israel, the Arab World, and the superpowers,'' University Press of Florida, 1991 pp.70-106, pp.94-5.'must be considered as an essential part of the backdrop against which the intifada germinated'.(p.95)</ref> This, which led to 50 deportations in the following 4 years,<ref>[[Helena Cobban]], 'The PLO and the Intifada', p.94. In the immediate aftermath of the 6 Day War in 1967, some 15,000 Gazans had been deported to Egypt. A further 1,150 were deported between September 1967 and May 1978.This pattern was drastically curtailed by the [[Likud]] governments under [[Menachem Begin]] between 1978-1984.</ref> was accompanied by economic integration and increasing Israeli [[Israeli settler|settlements]] such that the Jewish settler population in the West Bank alone nearly doubled from 35,000 in 1984 to 64,000 in 1988, reaching 130,000 by the mid nineties.<ref name=BM1>{{cite book|last=Morris|first=Benny|title=Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001|year=2001|publisher=Vintage|isbn=0679744754|pages=567}}</ref> Referring to the developments, Israeli minister of Economics and Finance, [[Gad Yaacobi|Gad Ya'acobi]], stated that "a creeping process of ''de facto'' annexation" contributed to a growing militancy in Palestinian society.<ref name="LockmanBeinin1989_32">[[#LockmanBeinin1989|Lockman; Beinin (1989)]], p. [http://books.google.com/books?id=KYPVNdzXUJkC&pg=PA32 32.]</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

During the 1980s a number of mainstream Israeli politicians referred to policies of transferring the Palestinian population out of the territories leading to Palestinian fears that Israel planned to evict them. Public statements calling for transfer of the Palestinian population were made by Deputy Defense minister [[Michael Dekel]], Cabinet Minister [[Mordechai Tzipori]] and government Minister [[Yosef Shapira]] among others.<ref name=BM1/> Describing the causes of the Intifada, [[Benny Morris]] refers to the "all-pervading element of humiliation", caused by the protracted occupation which he says was "always a brutal and mortifying experience for the occupied" and was "founded on brute force, repression and fear, collaboration and treachery, beatings and torture chambers, and daily intimidation, humiliation, and manipulation"<ref name=BM2>{{cite book|last=Morris|first=Benny|title=Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001|year=2001|publisher=Vintage|isbn=0679744754|pages=341, 568}}</ref>== History == |

|||

{{further|History of Palestinian nationality}} |

{{further|History of Palestinian nationality}} |

||

The collapse of the [[Ottoman Empire]] was accompanied by an increasing sense of [[Arab]] identity in the Empire's Arab provinces, most notably [[Greater Syria|Syria]], considered to include both northern [[Palestine]] and [[Lebanon]]. This development is often seen as connected to the wider reformist trend known as ''[[al-Nahda]]'' ("awakening", sometimes called "the Arab [[renaissance]]"), which in the late 19th century brought about a redefinition of Arab cultural and political identities with the unifying feature of [[Arabic]].<ref>Gudrun Krämer and Graham Harman (2008) A history of Palestine: from the Ottoman conquest to the founding of the state of Israel Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11897-3 p 123</ref> |

The collapse of the [[Ottoman Empire]] was accompanied by an increasing sense of [[Arab]] identity in the Empire's Arab provinces, most notably [[Greater Syria|Syria]], considered to include both northern [[Palestine]] and [[Lebanon]]. This development is often seen as connected to the wider reformist trend known as ''[[al-Nahda]]'' ("awakening", sometimes called "the Arab [[renaissance]]"), which in the late 19th century brought about a redefinition of Arab cultural and political identities with the unifying feature of [[Arabic]].<ref>Gudrun Krämer and Graham Harman (2008) A history of Palestine: from the Ottoman conquest to the founding of the state of Israel Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11897-3 p 123</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:13, 23 April 2013

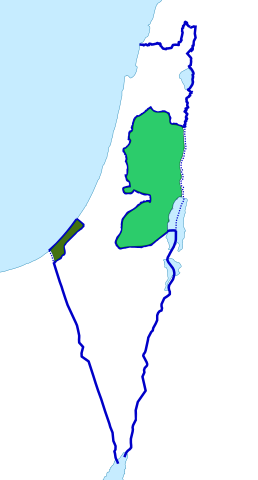

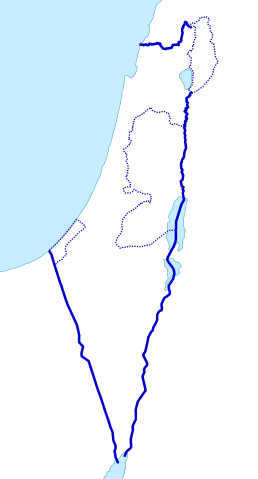

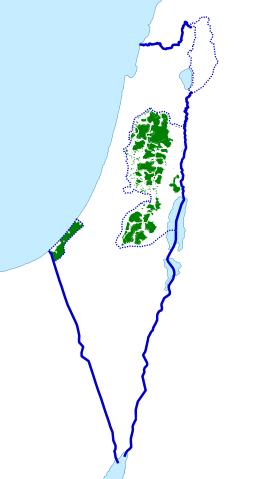

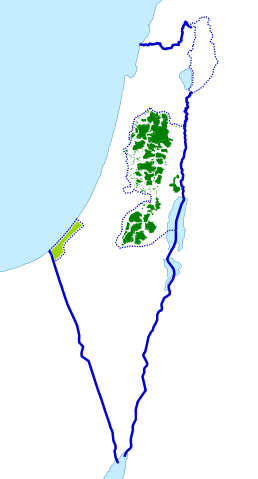

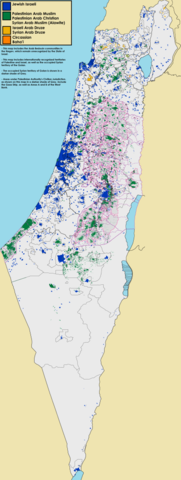

The Palestinian people, (Arabic: الشعب الفلسطيني, ash-sha‘b al-Filasṭīnī) also referred to as Palestinians (Arabic: الفلسطينيون, al-Filasṭīniyyūn), are the modern descendants of the peoples who have lived in Palestine over the centuries, and who today are largely culturally and linguistically Arab due to Arabization of the region.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Despite various wars and exoduses, roughly one half of the world's Palestinian population continues to reside in the area encompassing the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Israel. In this combined area, as of 2004, Palestinians constituted 49% of all inhabitants,[24] encompassing the entire population of the Gaza Strip (1.6 million), the majority of the population of the West Bank (approximately 2.3 million versus close to 500,000 Jewish Israeli citizens which includes about 200,000 in East Jerusalem), and 16.5% of the population of Israel proper as Arab citizens of Israel.[5] Many are Palestinian refugees or internally displaced Palestinians, including more than a million in the Gaza Strip,[25] three-quarters of a million in the West Bank,[25] and about a quarter of a million in Israel proper. Of the Palestinian population who live abroad, known as the Palestinian diaspora, more than half are stateless lacking citizenship in any country.[26] About 2.6 million of the diaspora population live in neighboring Jordan where they make up approximately half the population,[27] 1.5 million live between Syria and Lebanon, a quarter of a million in Saudi Arabia, with Chile's half a million representing the largest concentration outside the Arab world.

Genetic analysis suggests that a majority of the Muslims of Palestine, inclusive of Arab citizens of Israel, are descendants of Christians, Jews and other earlier inhabitants of the southern Levant whose core may reach back to prehistoric times. A study of high-resolution haplotypes demonstrated that a substantial portion of Y chromosomes of Israeli Jews (70%) and of Palestinian Muslim Arabs (82%) belonged to the same chromosome pool.[28] Since the time of the Muslim conquests in the 7th century, religious conversions have resulted in Palestinians being predominantly Sunni Muslim by religious affiliation, though there is a significant Palestinian Christian minority of various Christian denominations, as well as Druze and a small Samaritan community. Though Palestinian Jews made up part of the population of Palestine prior to the creation of the State of Israel, few identify as "Palestinian" today. Acculturation, independent from conversion to Islam, resulted in Palestinians being linguistically and culturally Arab.[16] The vernacular of Palestinians, irrespective of religion, is the Palestinian dialect of Arabic. Many Arab citizens of Israel including Palestinians are bilingual and fluent in Hebrew.

The history of a distinct Palestinian national identity is a disputed issue amongst scholars.[29] Legal historian Assaf Likhovski states that the prevailing view is that Palestinian identity originated in the early decades of the twentieth century.[29] "Palestinian" was used to refer to the nationalist concept of a Palestinian people by the Arabs of Palestine in a limited way until World War I.[20][21] The first demand for national independence of the Levant was issued by the Syrian–Palestinian Congress on 21 September 1921.[30] After the creation of the State of Israel, the exodus of 1948, and more so after the exodus of 1967, the term came to signify not only a place of origin, but also the sense of a shared past and future in the form of a Palestinian state.[20] According to Rashid Khalidi, the modern Palestinian people now understand their identity as encompassing the heritage of all ages from biblical times up to the Ottoman period.[31]

Founded in 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) is an umbrella organization for groups that represent the Palestinian people before the international community.[32] The Palestinian National Authority, officially established as a result of the Oslo Accords, is an interim administrative body nominally responsible for governance in Palestinian population centers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

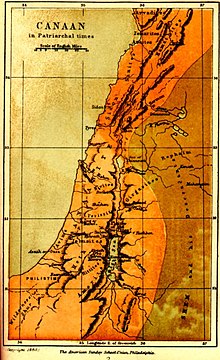

Etymology

The Greek toponym Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη), with which the Arabic Filastin (فلسطين) is cognate, first occurs in the work of the 5th. century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, where it denotes generally[33] the coastal land from Phoenicia down to Egypt.[34][35] Herodotus also employs the term as an ethnonym, as when he speaks of the 'Syrians of Palestine' or 'Palestinian-Syrians',[36] an ethnically amorphous group he distinguishes from the Phoenicians).[37] The Greek word bears comparison to a congeries of ancient ethnonyms and toponyms. In Ancient Egyptian Peleset/Purusati[38] refers to one of the Sea Peoples. Among Semitic languages, Assyrian Palastu generally refers to southern Palestine.[39] Old Hebrew's cognate word Plištim,[40] usually translated Philistines, does not distinguish them and the other Sea Peoples, who settled in Palestine around 1100 BCE.[41]

Syria Palestina continued to be used by historians and geographers and others to refer to the area between the Mediterranean sea and the Jordan river, as in the writings of Philo, Josephus and Pliny the Elder. After the Romans adopted the term as the official administrative name for the region in the 2nd century CE, "Palestine" as a stand alone term came into widespread use, printed on coins, in inscriptions and even in rabbinic texts.[42] The Arabic word Filastin has been used to refer to the region since the time of the earliest medieval Arab geographers. It appears to have been used as an Arabic adjectival noun in the region since as early as the 7th century CE.[43] The Arabic language newspaper Filasteen (est. 1911), published in Jaffa by Issa and Yusef al-Issa, addressed its readers as "Palestinians".[44]

During the British Mandate of Palestine, the term "Palestinian" was used to refer to all people residing there, regardless of religion or ethnicity, and those granted citizenship by the Mandatory authorities were granted "Palestinian citizenship".[45] Other examples include the use of the term Palestine Regiment to refer to the Jewish Infantry Brigade Group of the British Army during World War II, and the term "Palestinian Talmud", which is an alternative name of the Jerusalem Talmud, used mainly in academic sources.

Following the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel, the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to Palestinian Jews largely dropped from use. For example, the English-language newspaper The Palestine Post, founded by Jews in 1932, changed its name in 1950 to The Jerusalem Post. Jews in Israel and the West Bank today generally identify as Israelis. Arab citizens of Israel identify themselves as Israeli and/or Palestinian and/or Arab.[46]

The Palestinian National Charter, as amended by the PLO's Palestine National Council in July 1968, defined "Palestinians" as "those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were evicted from it or stayed there. Anyone born, after that date, of a Palestinian father – whether in Palestine or outside it – is also a Palestinian."[47] Note that "Arab nationals" is not religious-specific, and it implicitly includes not only the Arabic-speaking Muslims of Palestine, but also the Arabic-speaking Christians of Palestine and other religious communities of Palestine who were at that time Arabic-speakers, such as the Samaritans and Druze. Thus, the Jews of Palestine were/are also included, although limited only to "the [Arabic-speaking] Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the [pre-state] Zionist invasion." The Charter also states that "Palestine with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit."[47][48]

History

Palestinian history and nationalism

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

The timing and causes behind the emergence of a distinctively Palestinian national consciousness among the Arabs of Palestine are matters of scholarly disagreement. Some argue that it can be traced as far back as the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine (or even as early as the 17th century), while others argue that it didn't emerge until after the Mandate Palestine period.[29][49] According to legal historian Assaf Likhovski, the prevailing view is that Palestinian identity originated in the early decades of the twentieth century.[29]

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian Rashid Khalidi notes that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine – encompassing the Biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods – form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century.[50] Noting that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" playing an important role, Khalidi cautions against the efforts of some Palestinian nationalists to "anachronistically" read back into history a nationalist consciousness that is in fact "relatively modern".[50][51]

Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal consider the 1834 revolt of the Arabs in Palestine as constituting the first formative event of the Palestinian people. From 1516–1917, Palestine was ruled by the Ottoman Empire save a brief period In the 1830s when an Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali, and his son Ibrahim Pasha asserted their own rule over the area. The revolt by Palestine's Arabs was precipitated by popular resistance against heavy demands for conscripts, with the peasants well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834 the rebels took many cities, among them Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus and Ibrahim Pasha's army was deployed, defeating the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.[52] Benny Morris argues that the Arabs in Palestine nevertheless remained part of a larger pan-Islamist or pan-Arab national movement.[53] Walid Khalidi argues otherwise, writing that Palestinians in Ottoman times were "[a]cutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history ..." and "[a]lthough proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry, the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the seventh century but also from indigenous peoples who had lived in the country since time immemorial, including the ancient Hebrews and the Canaanites before them."[54]

Rashid Khalidi argues that the modern national identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman empire in the late 19th century that sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I.[51] Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."[51] Conversely, historian James L. Gelvin argues that Palestinian nationalism was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War he states that "Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement."[55] Gelvin argues that this fact does not make the Palestinian identity any less legitimate:

"The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose."[55]

David Seddon writes that "[t]he creation of Palestinian identity in its contemporary sense was formed essentially during the 1960s, with the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization". He adds, however, that "the existence of a population with a recognizably similar name ('the Philistines') in Biblical times suggests a degree of continuity over a long historical period (much as 'the Israelites' of the Bible suggest a long historical continuity in the same region)."[56]

Bernard Lewis argues it was not as a Palestinian nation that the Arabs of Ottoman Palestine objected to Zionists, since the very concept of such a nation was unknown to the Arabs of the area at the time and did not come into being until very much later. Even the concept of Arab nationalism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, "had not reached significant proportions before the outbreak of World War I."[21] Tamir Sorek, a sociologist, submits that, "Although a distinct Palestinian identity can be traced back at least to the middle of the nineteenth century (Kimmerling and Migdal 1993; Khalidi 1997b), or even to the seventeenth century (Gerber 1998), it was not until after World War I that a broad range of optional political affiliations became relevant for the Arabs of Palestine."[49]

Whatever the differing viewpoints over the timing, causal mechanisms, and orientation of Palestinian nationalism, by the early 20th century strong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content of Arabic-language newspapers in Palestinian Territories, such as Al-Karmil (est. 1908) and Filasteen (est. 1911).[57] Filasteen initially focused its critique of Zionism around the failure of the Ottoman administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of foreigners, later exploring the impact of Zionist land-purchases on Palestinian peasants (Arabic: فلاحين, fellahin), expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications for the society at large.[57]

The first Palestinian nationalist organisations emerged at the end of the World War I.[58] Two political factions emerged. al-Muntada al-Adabi, dominated by the Nashashibi family, militated for the promotion of the Arabic language and culture, for the defense of Islamic values and for an independent Syria and Palestine. In Damascus, al-Nadi al-Arabi, dominated by the Husayni family, defended the same values.[59]

The historical record continued to reveal an interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalism. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in Jerusalem, February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the Paris Peace Conference, adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds."[60]

After the Nabi Musa riots, the San Remo conference and the failure of Faisal to establish the Kingdom of Greater Syria, a distinctive form of Palestinian Arab nationalism took root between April and July 1920.[61][62] With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French conquest of Syria, the formerly pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem, Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni, said "Now, after the recent events in Damascus, we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine".[63]

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of pan-Arabists continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalized. Two prominent leaders of the Palestinian nationalists were Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem,appointed by the British, and Izz ad-Din al-Qassam.[64]

Struggle for self-determination

Palestinians have not exercised full sovereignty over the land in which they have lived during the modern era. Palestine was administered by the Ottoman Empire until World War I, and then overseen by the British Mandatory authorities. Israel was established in parts of Palestine in 1948, and in the wake of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the West Bank and East Jerusalem were occupied by Jordan, and the Gaza Strip by Egypt, with both countries continuing to administer these areas until Israel occupied them in the Six-Day War. Historian Avi Shlaim states that the Palestinians' lack of sovereignty over the land has been used by Israelis to deny Palestinians their rights [to self-determination].[65]

Today, the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination has been affirmed by the United Nations General Assembly, the International Court of Justice[66] and several Israeli authorities.[67] A total of 122 countries recognize Palestine as a state.[68] However, Palestinian sovereignty over the areas claimed as part of the Palestinian state remains limited, and the boundaries of the state remain a point of contestation between Palestinians and Israelis.

British Mandate (1917–1948)

Article 22 of The Covenant of the League of Nations conferred an international legal status upon the territories and people which had ceased to be under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire as part of a 'sacred trust of civilization'. Article 7 of the League of Nations Mandate required the establishment of a new, separate, Palestinian nationality for the inhabitants. This meant that Palestinians did not become British citizens, and that Palestine was not annexed into the British dominions.[69] The Mandate document divided the population into Jewish and non-Jewish, and Britain, the Mandatory Power considered the Palestinian population to be comprisd of religious, not national, groups. Consequently government censuses in 1922 and 1931 would categorize Palestinians confessionally as Muslims, Christians and Jews, with the category of Arab absent.[70]

After the British general, Louis Bols, read out the Balfour Declaration of 1917 in February 1920, some 1,500 Palestinians demonstrated in the streets of Jerusalem.[64] A month later, during the 1920 Palestine riots, the protests against British rule and Jewish immigration became violent and Bols banned all demonstrations. In May 1921 however, further anti-Jewish riots broke out in Jaffa and dozens of Arabs and Jews were killed in the confrontations.[64]

The articles of the Mandate mentioned the civil and religious rights of the non-Jewish communities in Palestine, but not their political status. At the San Remo conference it was decided to accept the text of those articles, while inserting in the minutes of the conference an undertaking by the Mandatory Power that this would not involve the surrender of any of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine. In 1922, the British authorities over Mandate Palestine proposed a draft constitution that would have granted the Palestinian Arabs representation in a Legislative Council on condition that they accept the terms of the mandate. The Palestine Arab delegation rejected the proposal as "wholly unsatisfactory," noting that "the People of Palestine" could not accept the inclusion of the Balfour Declaration in the constitution's preamble as the basis for discussions. They further took issue with the designation of Palestine as a British "colony of the lowest order."[71] The Arabs tried to get the British to offer an Arab legal establishment again roughly ten years later, but to no avail.[72]

After the killing of Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam by the British in 1935, his followers initiated the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, which began with a general strike in Jaffa and attacks on Jewish and British installations in Nablus.[64] The Arab High Committee called for a nationwide general strike, non-payment of taxes, and the closure of municipal governments, and demanded an end to Jewish immigration and a ban of the sale of land to Jews. By the end of 1936, the movement had become a national revolt, and resistance grew during 1937 and 1938. In response, the British declared martial law, dissolved the Arab High Committee and arrested officials from the Supreme Muslim Council who were behind the revolt. By 1939, 5,000 Arabs had been killed in British attempts to quash the revolt; more than 15,000 were wounded.[64]

The "lost years" (1948–1967)

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and the accompanying Palestinian exodus, known to Palestinians as Al Nakba (the "catastrophe"), there was a hiatus in Palestinian political activity. Khalidi attributes this to the tramautic events of 1947-1949, which included the depopulation of over 400 towns and villages and the creation of hundreds of thousands of refugees.[73] Those parts of British Mandate Palestine which did not become part of the newly declared Israeli state were occupied by Egypt and Jordan. During what Khalidi terms the "lost years" that followed, Palestinians lacked a center of gravity, divided as they were between these countries and others such as Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere.[74]

Israeli historian Efraim Karsh takes the view that the Palestinian identity did not develop until after the 1967 war because the Palestinian exodus had fractured society so greatly that it was impossible to piece together a national identity. Between 1948 and 1967, the Jordanians and other Arab countries hosting Arab refugees from Palestine/Israel silenced any expression of Palestinian identity and occupied their lands until Israel's conquests of 1967. The formal annexation of the West Bank by Jordan in 1950, and the subsequent granting of its Palestinian Arab residents Jordanian citizenship, further stunted the growth of a Palestinian national identity by integrating them into Jordanian society.[75]

In the 1950s, a new generation of Palestinian nationalist groups and movements began to organize clandestinely, stepping out onto the public stage in the 1960s.[76] The traditional Palestinian elite who had dominated negotiations with the British and the Zionists in the Mandate, and who were largely held responsible for the loss of Palestine, were replaced by these new movements whose recruits generally came from poor to middle-class backgrounds and were often students or recent graduates of universities in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus.[76] The potency of the pan-Arabist ideology put forward by Gamel Abdel Nasser—popular among Palestinians for whom Arabism was already an important component of their identity[77]—tended to obscure the identities of the separate Arab states it subsumed.[78]

1967–present

Since 1967, pan-Arabism has waned as an aspect of Palestinian identity. The Israeli capture of the Gaza Strip and West Bank triggered a second Palestinian exodus and fractured Palestinian political and militant groups, prompting them to give up residual hopes in pan-Arabism. They rallied increasingly around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which had been some years earlier, in 1964, and its nationalistic orientation under the leadership of Yasser Arafat.[79] Mainstream secular Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the PLO whose constituent organizations include Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, among other groups who at that time believed that political violence was the only way to liberate Palestine.[50] These groups gave voice to a tradition that emerged in 1960s that argues Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millennia, when such a consciousness is in fact relatively modern.[80]

The Battle of Karameh and the events of Black September in Jordan contributed to growing Palestinian support for these groups, particularly among Palestinians in exile. Concurrently, among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, a new ideological theme, known as sumud, represented the Palestinian political strategy popularly adopted from 1967 onward. As a concept closely related to the land, agriculture and indigenousness, the ideal image of the Palestinian put forward at this time was that of the peasant (in Arabic, fellah) who stayed put on his land, refusing to leave. A strategy more passive than that adopted by the Palestinian fedayeen, sumud provided an important subtext to the narrative of the fighters, "in symbolizing continuity and connections with the land, with peasantry and a rural way of life."[81]

In 1974, the PLO was recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the Arab nation-states and was granted observer status as a national liberation movement by the United Nations that same year.[32][82] Israel rejected the resolution, calling it "shameful".[83] In a speech to the Knesset, Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Yigal Allon outlined the government's view that: 'No one can expect us to recognize the terrorist organization called the PLO as representing the Palestinians—because it does not. No one can expect us to negotiate with the heads of terror-gangs, who through their ideology and actions, endeavor to liquidate the State of Israel.'[83]

In 1975 the United Nations established a subsidiary organ, the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People, to recommend a program of implementation to enable the Palestinian people to exercise national independence and their rights to self-determination without external interference, national independence and sovereignty, and to return to their homes and property.[84]

The First Intifada (1987–1993) was the first popular uprising against the Israeli occupation of 1967. Followed by the PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine, these developments served to further reinforce the Palestinian national identity. At the end of the Gulf War, Kuwait expelled some 450,000 Palestinians from its territory,[85] making it the second largest displacement of Palestinians after 1948 Palestine War. Kuwait's expulsion policy, which led to this exodus, was a response to alignment of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and the PLO with Saddam Hussein, who had earlier invaded Kuwait. The 1991 Palestinian exodus took place during one week in March 1991, following Kuwait's liberation from Iraqi occupation. Prior to the exodus, Palestinians made up about 30% of Kuwait's population of 2.2 million.[86] By 2006 only a few had returned to Kuwait.

The Oslo Accords, the first Israeli-Palestinian interim peace agreement, were signed in 1993. The process was envisioned to last five years, ending in June 1999, when the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Gaza Strip and the Jericho area began. The expiration of this term without the recognition by Israel of the Palestinian State and without the effective termination of the occupation was followed by the Second Intifada in 2000.[87][88] The second intifada was more violent than the first.[89] The International Court of Justice observed that since the government of Israel had decided to recognize the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people, their existence was no longer an issue. The court noted that the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip of 28 September 1995 also referred a number of times to the Palestinian people and its "legitimate rights".[90] The right of self-determination gives the Palestinians collectively an inalienable right to freely choose their political status, including the establishment of a sovereign and independent state. Israel, having recognized the Palestinians as a separate people, is obliged to promote and respect this right in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.[91]

Contemporary writing

The Outline of History, by H.G.Wells (1920), notes the following about this geographic region and the turmoil of the times:

It was clearly a source of strength to them Turks, rather than weakness, that they were cut off altogether from their age-long ineffective conflict with the Arab. Syria, Mesopotamia, were entirely detached from Turkish rule. Palestine was made a separate state within the British sphere, earmarked as a national home for the Jews. A flood of poor Jewish immigrants poured into the promised land and was speedily involved in serious conflicts with the Arab population. The Arabs had been consolidated against the Turks and inspired with a conception of national unity through the exertions of a young Oxford scholar, Colonel Lawrence. His dream of an Arab kingdom with its capital at Damascus was speedily shattered by the hunger of the French and British for mandatory territory, and in the end his Arab kingdom shrank to the desert kingdom of the Hedjaz and various other small and insecure imamates, emirates and sultanates. If ever they are united, and struggle into civilization, it will not be under Western auspices.[92]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is the ongoing struggle between Israelis and Palestinians that began in the early 20th century.[93] The conflict is wide-ranging, and the term is also used in reference to the earlier phases of the same conflict, between the Zionist yishuv and the Arab population living in Palestine under Ottoman and then British rule. It forms part of the wider Arab–Israeli conflict. The remaining key issues are: mutual recognition, borders, security, water rights, control of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements,[94] Palestinian freedom of movement[95] and finding a resolution to the refugee question. The violence resulting from the conflict has prompted international actions, as well as other security and human rights concerns, both within and between both sides, and internationally. In addition, the violence has curbed expansion of tourism in the region, which is full of historic and religious sites that are of interest to many people around the world.

Many attempts have been made to broker a two-state solution, involving the creation of an independent Palestinian state alongside an independent Jewish state or next to the State of Israel (after Israel's establishment in 1948). In 2007 a majority of both Israelis and Palestinians, according to a number of polls, preferred the two-state solution over any other solution as a means of resolving the conflict.[96] Moreover, a considerable majority of the Jewish public sees the Palestinians' demand for an independent state as just, and thinks Israel can agree to the establishment of such a state.[97] A majority of Palestinians and Israelis view the West Bank and Gaza Strip as an acceptable location of the hypothetical Palestinian state in a two-state solution.[98][unreliable source?] However, there are significant areas of disagreement over the shape of any final agreement and also regarding the level of credibility each side sees in the other in upholding basic commitments.[99]

Within Israeli and Palestinian society, the conflict generates a wide variety of views and opinions. This highlights the deep divisions which exist not only between Israelis and Palestinians, but also within each society. A hallmark of the conflict has been the level of violence witnessed for virtually its entire duration. Fighting has been conducted by regular armies, paramilitary groups, terror cells and individuals. Casualties have not been restricted to the military, with a large number of fatalities in civilian population on both sides. There are prominent international actors involved in the conflict.

Zionism

When Zionism began taking root among Jewish communities in Europe, many Jews emigrated to Palestine and established settlements there. When Palestinian Arabs concerned themselves with Zionists, they generally assumed the movement would fail. After the Young Turk revolution in 1908, Arab Nationalism grew rapidly in the area and most Arab Nationalists regarded Zionism as a threat, although a minority perceived Zionism as providing a path to modernity.[100] Though there had already been Arab protests to the Ottoman authorities in the 1880s against land sales to foreign Jews, the most serious opposition began in the 1890s after the full scope of the Zionist enterprise became known. There was a general sense of threat. This sense was heightened in the early years of the 20th century by Zionist attempts to develop an economy from which Arab people were largely excluded, such as the "Hebrew labor" movement which campaigned against the employment of cheap Arab labour. The creation of Palestine in 1918 and the Balfour Declaration greatly increased Arab fears. Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people. It has roots in Pan-Arabism, the rejection of colonialism and movements calling for national independence.[101] Unlike pan-Arabism in general, Palestinian nationalism has emphasized Palestinian self-government and has rejected the historic non-domestic Arab rule by Egypt over the Gaza Strip and Jordan over the West Bank.

Palestinian nationalism

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people. It has roots in Pan-Arabism, the rejection of colonialism and movements calling for national independence.[101] Unlike pan-Arabism in general, Palestinian nationalism has emphasized Palestinian self-government and has rejected the historic non-domestic Arab rule by Egypt over the Gaza Strip and Jordan over the West Bank. Before the development of modern nationalism, loyalty tended to focus on a city or a particular leader. The term "nationalismus", translated as nationalism, was coined by Johann Gottfried Herder in the late 1770s. Palestinian nationalism has been compared to other nationalist movements, such as Pan-Arabism and Zionism. Some nationalists argue that “the nation was always there, indeed it is part of the natural order, even when it was submerged in the hearts of its members.”[102] In keeping with this philosophy, Al-Quds University states that although “Palestine was conquered in times past by ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Philistines, Israel, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Romans, Muslim Arabs, Mamlukes, Ottomans, the British, the Zionists…the population remained constant-and is now still Palestinian.”[103]

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian Rashid Khalidi notes that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine — encompassing the Biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods — form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century,[50] but derides the efforts of some Palestinian nationalists to attempt to "anachronistically" read back into history a nationalist consciousness that is in fact "relatively modern."[50] Khalidi stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" playing an important role.[51] He argues that the modern national identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman empire in the late 19th century which sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I.[51] He acknowledges that Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, though "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."[51] Khalidi describes the Arab population of British Mandatory Palestine as having "overlapping identities," with some or many expressing loyalties to villages, regions, a projected nation of Palestine, an alternative of inclusion in a Greater Syria, an Arab national project, as well as to Islam.[104] He writes that,"local patriotism could not yet be described as nation-state nationalism."[105]

Israeli historian Haim Gerber, a professor of Islamic History at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, traces Arab nationalism back to a 17th century religious leader, Mufti Khayr al-Din al-Ramli (1585–1671)[106] who lived in Ramla. He claims that Khayr al-Din al-Ramli's religious edicts (fatwa, plural fatawa), collected into final form in 1670 under the name al-Fatawa al-Khayriyah, attest to territorial awareness: "These fatawa are a contemporary record of the time, and also give a complex view of agrarian relations." Mufti Khayr al-Din al-Ramli's 1670 collection entitled al-Fatawa al-Khayriyah mentions the concepts Filastin, biladuna (our country), al-Sham (Syria), Misr (Egypt), and diyar (country), in senses that appear to go beyond objective geography. Gerber describes this as "embryonic territorial awareness, though the reference is to social awareness rather than to a political one."[107]

Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal consider the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine as the first formative event of the Palestinian people,[52] whereas Benny Morris stest that the Arabs in Palestine remained part of a larger Pan-Islamist or Pan-Arab national movement.[108]

In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War, James L. Gelvin states that "Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement."[55] However, this does not make Palestinian identity any less legitimate: "The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose."[55]

Bernard Lewis argues it was not as a Palestinian nation that the Palestinian Arabs of the Ottoman empire objected to Zionists, since the very concept of such a nation was unknown to the Arabs of the area at the time and did not come into being until later. Even the concept of Arab nationalism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, "had not reached significant proportions before the outbreak of World War I."[21]

Daniel Pipes asserts that “No 'Palestinian Arab people' existed at the start of 1920 but by December it took shape in a form recognizably similar to today's.” Pipes argues that with the carving of the British Mandate of Palestine out of Greater Syria the Arabs of the new Mandate were forced to make the best they could of their situation, and therefore began to define themselves as Palestinian.[109]

Intifada

Israeli total | Palestinian total |

Israeli breakdown | Palestinian breakdown |

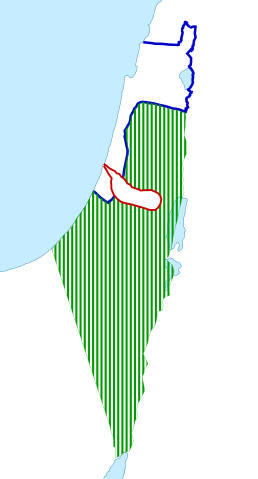

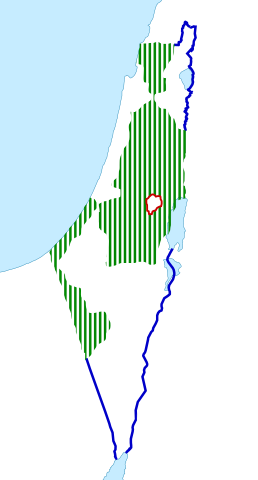

The chart is based on B'Tselem casualty numbers.[110] It does not include the 577 Palestinians killed by Palestinians.

The First Intifada was Palestinianuprising against the Israeli occupation of the [[Palestinian Territorieslate 1987 until 1991-3, policies of deportation, confiscation of lands, and their settlement, and consisting of general strikes, civil disobedience and boycotts of Israeli institutions and products. Stone-throwing was widespread. Israel adopted a policy of "breaking Palestinians' bones" to put down the revolt. In the conflict an estimated 1,100 Palestinian, and 16 Israeli citizens were killed, while many more were injured. Infra-communal conflict among Palestinians over collaboration also led to several hundred death killings.

History

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire was accompanied by an increasing sense of Arab identity in the Empire's Arab provinces, most notably Syria, considered to include both northern Palestine and Lebanon. This development is often seen as connected to the wider reformist trend known as al-Nahda ("awakening", sometimes called "the Arab renaissance"), which in the late 19th century brought about a redefinition of Arab cultural and political identities with the unifying feature of Arabic.[111]

Under the Ottomans, Palestine's Arab population mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects. In the 1830s however, Palestine was occupied by the Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha. The Palestinian Arab revolt was precipitated by popular resistance against heavy demands for conscripts, as peasants were well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834 the rebels took many cities, among them Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus. In response, Ibrahim Pasha sent in an army, finally defeating the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.[52]

While Arab nationalism, at least in an early form, and Syrian nationalism were the dominant tendencies along with continuing loyalty to the Ottoman state, Palestinian politics were marked by a reaction to foreign predominance and the growth of foreign immigration, particularly Zionist.[112]

The Egyptian occupation of Palestine in the 1830s resulted in the destruction of Acre and thus, the political importance of Nablus increased. The Ottomans wrested back control of Palestine from the Egyptians in 1840-41. As a result, the Abd al-Hadi clan, who originated in Arrabah in the Sahl Arraba region in northern Samaria, rose to prominence. Loyal allies of Jezzar Pasha and the Tuqans, they gained the governorship of Jabal Nablus and other sanjaqs.[113]

In 1887 the mutassariflik of Jerusalem was constituted as part of an Ottoman government policy dividing the vilayet of Greater Syria into smaller administrative units. The administration of the mutassariflik took on a distinctly local appearance.[114]

Michelle Compos records that "Later, after the founding of Tel Aviv in 1909, conflicts over land grew in the direction of explicit national rivalry."[115] Zionist ambitions were increasingly identified as a threat by Palestinian leaders, while cases of purchase of lands by Zionist settlers and the subsequent eviction of Palestinian peasants aggravated the issue. This anti-Zionist trend became linked to anti-British resistance, to form a nationalist movement quite particular and separate from the pan-Arab trend that was gaining strength in the Arab world, and would later be headed by Nasser, Ben Bella and other anticolonial leaders.

The programmes of four Palestinian nationalist societies jamyyat al-Ikha’ wal-‘Afaf (Brotherhood and Purity), al-jam’iyya al-Khayriyya al-Islamiyya, Shirkat al-Iqtissad alFalastini al-Arabi and Shirkat al-Tijara al-Wataniyya al-Iqtisadiyya were reported in the newspaper Falastin in June 1914 by letter from R. Abu al-Sal’ud. The four societies has similarities in function and ideals; the promotion of patriotism, educational aspirations and support for national industries.[116]

Template:Timeline of Intifadas

Second Intifada

The Second Intifada,[note A] also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada and the Oslo War, was the second Palestinian uprising – a period of intensified Palestinian–Israeliviolence, which began in late September 2000 and ended around 2005. The death toll, including both military and civilian, is estimated to be over 3,000 Palestinians and around 1,000 Israelis (Jews and Arabs), as well as 64 foreigners.[117][118] B'Tselem's figures indicate that through April 30, 2008, 35.2% of the Palestinians who were killed directly took part in the hostilities,[119]46.4% "did not take part in the hostilities",[110] and 18.5% where it was not known if they were taking part in hostilities.[110] Of the Israeli casualties, B'Tselem reports that 31.7% were security force personnel and 68.3% were civilians.[110] A 2005 study conducted by Israel's International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) concluded that Palestinian fatalities have consisted of more combatants than noncombatants.[120] Up to 2005, the ICT puts Israeli combatant casualties at 22% and civilian at 78%.[121] The First Intifada was from December 1987 to 1993.

Palestinian leadership

The Palestinian Arabs were led by two main camps. The Nashashibis, led by Raghib al-Nashashibi, who was Mayor of Jerusalem from 1920 to 1934, were moderates who sought dialogue with the British and the Jews. The Nashashibis were overshadowed by the al-Husaynis who came to dominate Palestinian-Arab politics in the years before 1948. The al-Husaynis, like most Arab Nationalists, denied that Jews had any national rights in Palestine.

The British granted the Palestinian Arabs a religious leadership, but they always kept it dependent.[122] The office of Mufti of Jerusalem, traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned into that of Grand Mufti of Palestine. Furthermore a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC) was established and given various duties like the administration of religious endowments and the appointment of religious judges and local muftis. In Ottoman times these duties had been fulfilled by the bureaucracy in Istanbul.[122]

In ruling the Palestinian Arabs the British preferred to deal with elites, rather than with political formations rooted in the middle or lower classes.[123] For instance they ignored the Palestine Arab Congress. The British also tried to create divisions among these elites. For instance they chose Hajj Amin al-Husayni to become Grand Mufti, although he was young and had received the fewest votes from Jerusalem’s Islamic leaders.[124] Hajj Amin was a distant cousin ofMusa Kazim al-Husainy, the leader of the Palestine Arab Congress. According to Khalidi, by appointing a younger relative, the British hoped to undermine the position of Musa Kazim.[125] Indeed they stayed rivals until the death of Musa Kazim in 1934. Another of the mufti's rivals, Raghib Bey al-Nashashibi, had already been appointed mayor of Jerusalem in 1920, replacing Musa Kazim whom the British removed after the Nabi Musa riots of 1920,[126][127] during which he exhorted the crowd to give their blood for Palestine.[128] During the entire Mandate period, but especially during the latter half the rivalry between the mufti and al-Nashashibi dominated Palestinian politics.

Many notables were dependent on the British for their income. In return for their support of the notables the British required them to appease the population. According to Khalidi this worked admirably well until the mid-1930s, when the mufti was pushed into serious opposition by a popular explosion.[129] After that the mufti became the deadly foe of the British and the Zionists.

According to Khalidi before the mid-1930s the notables from both the al-Husayni and the al-Nashashibi factions acted as though by simply continuing to negotiate with the British they could convince them to grant the Palestinians their political rights.[130] The Arab population considered both factions as ineffective in their national struggle, and linked to and dependent on the British administration. Khalidi ascribes the failure of the Palestinian leaders to enroll mass support to their experience during the Ottoman period, when they were part of the ruling elite and were accostumed to command. The idea of mobilising the masses was thoroughly alien to them.[131]

There had already been rioting and attacks on and massacres of Jews in 1921 and 1929. During the 1930s Palestinian Arab popular discontent with Jewish immigration and increasing Arab landlessness grew. In the late 1920s and early 1930s several factions of Palestinian society, especially from the younger generation, became impatient with the internecine divisions and ineffectiveness of the Palestinian elite and engaged in grass-roots anti-British and anti-Zionist activism organized by groups such as the Young Men's Muslim Association. There was also support for the growth in influence of the radical nationalist Independence Party (Hizb al-Istiqlal), which called for a boycott of the British in the manner of the Indian Congress Party. Some even took to the hills to fight the British and the Zionists. Most of these initiatives were contained and defeated by notables in the pay of the Mandatory Administration, particularly the mufti and his cousin Jamal al-Husayni. The younger generation also formed the backbone of the organisation of the six-month general strike of 1936, which marked the start of the great Palestinian Revolt.[132] According to Khalidi this was a grass-roots uprising, which was eventually adopted by the old Palestinian leadership, whose 'inept leadership helped to doom these movements as well'.

Ancestral origins

"Throughout history a great diversity of peoples has moved into the region and made Palestine their homeland: Canaanites, Jebusites, Philistines from Crete, Anatolian and Lydian Greeks, Hebrews, Amorites, Edomites, Nabataeans, Arameans, Romans, Arabs, and Western European Crusaders, to name a few. Each of them appropriated different regions that overlapped in time and competed for sovereignty and land. Others, such as Ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Persians, Babylonians, and the Mongol raids of the late 1200s, were historical 'events' whose successive occupations were as ravaging as the effects of major earthquakes ... Like shooting stars, the various cultures shine for a brief moment before they fade out of official historical and cultural records of Palestine. The people, however, survive. In their customs and manners, fossils of these ancient civilizations survived until modernity—albeit modernity camouflaged under the veneer of Islam and Arabic culture."[133]

Like the Lebanese, Syrians, Egyptians, Maghrebis, and most other people today commonly called Arabs, the Palestinians are an Arab people in linguistic and cultural affiliation. Since the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, Palestine, a then Hellenized location, came under the influence of an Arabic-speaking Kurdish Muslim dynasty known as the Ayyubids, whose culture and language through the process of Arabization was adopted by the people of Palestine.[16] Genetic research studies suggests that some or perhaps most of the present-day Palestinians have roots that go back to before the 7th century, maybe even ancient inhabitants of the area.[134]

George Antonius, founder of modern Arab nationalist history, wrote in his seminal 1938 book The Arab Awakening:

" The Arabs' connection with Palestine goes back uninterruptedly to the earliest historic times, for the term 'Arab' [in Palestine] denotes nowadays not merely the incomers from the Arabian Peninsula who occupied the country in the seventh century, but also the older populations who intermarried with their conquerors, acquired their speech, customs and ways of thought and became permanently arabised."[135]

American historian Bernard Lewis writes:

"Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine..."[136]

Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, explains:

Eric M. Meyers, a Duke University historian of religion, writes:

"What is the significance of the Palestinians really being descended from the Canaanites? In the early and more conservative reconstruction of history, it might be said that this merely confirms the historic enmity between Israel and its enemies. However, some scholars believe that Israel actually emerged from within the Canaanite community itself (Northwest Semites) and allied itself with Canaanite elements against the city-states and elites of Canaan. Once they were disenfranchised by these city-statres and elites, the Israelites and some disenfranchised Canaanites joined together to challenge the hegemony of the heads of the city-states and forged a new identity in the hill country based on egalitarian principles and a common threat from without. This is another irony in modern politics: the Palestinians in truth are blood brothers or cousins of the modern Israelis."[137]

Politicized lineages

Salim Tamari notes the paradoxes produced by the search for "nativist" roots among Zionist figures and the so-called Canaanite followers of Yonatan Ratosh.[138] For example, Ber Borochov, one of the key ideological architects of Socialist Zionism, claimed as early as 1905 that, "The Fellahin in Eretz-Israel are the descendants of remnants of the Hebrew agricultural community,"[139] believing them to be descendants of the ancient Hebrew and Canaanite residents 'together with a small admixture of Arab blood'".[138] He further believed that the Palestinian peasantry would embrace Zionism and that the lack of a crystallized national consciousness among Palestinian Arabs would result in their likely assimilation into the new Hebrew nationalism.[138] Other founding fathers of Zionism believed that the Palestinian people were descended from the biblical ancient Hebrews. David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben Zvi, later becoming Israel's first Prime Minister and second President, respectively, tried to establish in a 1918 paper written in Yiddish that Palestinian peasants and their mode of life were living historical testimonies to Israelite practices in the biblical period.[138][140] Tamari notes that "the ideological implications of this claim became very problematic and were soon withdrawn from circulation."[138]

Ahad Ha'am believed that, "the Moslems [of Palestine] are the ancient residents of the land ... who became Christians on the rise of Christianity and became Moslems on the arrival of Islam."[138] Israel Belkind, the founder of the Bilu movement also asserted that the Palestinian Arabs were the blood brothers of the Jews.[141] In his book on the Palestinians, "The Arabs in Eretz-Israel", Belkind advanced the idea that the dispersion of Jews out of the Land of Israel after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Roman emperor Titus is a "historic error" that must be corrected. While it dispersed much of the land's Jewish community around the world, those "workers of the land that remained attached to their land," stayed behind and were eventually converted to Christianity and then Islam.[141] He therefore, proposed that this historical wrong be corrected, by embracing the Palestinians as their own and proposed the opening of Hebrew schools for Palestinian Arab Muslims to teach them Arabic, Hebrew and universal culture.[141] Tsvi Misinai, an Israeli researcher, entrepreneur and proponent of a controversial alternative solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, asserts that nearly 90% of all Palestinians living within Israel and the occupied territories (including Israel's Arab citizens and Negev Bedouin)[142] are descended from the Jewish Israelite peasantry that remained on the land, after the others, mostly city dwellers, were exiled or left.[143]

Claims emanating from certain circles within Palestinian society and their supporters, proposing that Palestinians have direct ancestral connections to the ancient Canaanites, without an intermediate Israelite link, has been an issue of contention within the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Bernard Lewis wrote that "the rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims...In bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."[136][144]

Some Palestinian scholars, like Zakariyya Muhammad, have criticized pro-Palestinian arguments based on Canaanite lineage, or what he calls "Canaanite ideology". He states that it is an "intellectual fad, divorced from the concerns of ordinary people."[138] By assigning its pursuit to the desire to predate Jewish national claims, he describes Canaanism as a "losing ideology", whether or not it is factual, "when used to manage our conflict with the Zionist movement" since Canaanism "concedes a priori the central thesis of Zionism. Namely that we have been engaged in a perennial conflict with Zionism—and hence with the Jewish presence in Palestine—since the Kingdom of Solomon and before ... thus in one stroke Canaanism cancels the assumption that Zionism is a European movement, propelled by modern European contingencies..."[138]

DNA and genetic studies

In recent years, many genetic studies have demonstrated that, at least paternally, most of the various Jewish ethnic divisions and the Palestinians – and in some cases other Levantines – are genetically closer to each other than the Palestinians or European Jews to non-Jewish Europeans.[145]

One DNA study by Nebel found genetic evidence in support of historical records that "part, or perhaps the majority" of Muslim Palestinians descend from "local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD".[145] They also found substantial genetic overlap between Muslim Palestinians and Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews, though with some significant differences that might be explainable by the geographical isolation of the Jews and by immigration of Arab tribes in the first millennium.[145]

HLA genetic studies relate Palestinians with other Middle East populations, like Jews.[146][147]

In genetic genealogy studies, Negev Bedouins have the highest rates of Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) among all populations tested (62.5%) followed by the Palestinian Arab 38.4%, Ashkenazi Jew 14.6%, and Sephardi Jew 11.9% according to Semino and colleagues.[citation needed] Semitic populations, including Jews, usually possess an excess of J1 Y chromosomes compared to other populations harboring Y-haplogroup J.[148][149][150][151][152] The haplogroup J1, associated with marker M267, originates south of the Levant and was first disseminated from there into Ethiopia and Europe in Neolithic times. In Jewish populations J1 has a rate of around 15%, with haplogroup J2 (M172) (of eight sub-Haplogroups) being almost twice as common as J1 among Jews (<29%). J1 is most common in the southern Levant, as well as Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and Arabia, and drops sharply at the border of non-semitic areas like Turkey and Iran. A second diffusion of the J1 marker took place in the 7th century CE when Arabians brought it from Arabia to North Africa.[148]

Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) includes the modal haplotype of the Galilee Arabs[145] and of Moroccan Arabs[153] and the sister Modal Haplotype of the Cohanim, the "Cohan Modale Haplotype", representing the descendents of the priestly caste Aaron.[154][155][156] J2 is known to be related to the ancient Greek movements and is found mainly in Europe and the central Mediterranean (Italy, the Balkans, Greece).

According to a 2010 study by Behar at al titled "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people," Palestinians cluster genetically close to Bedouins and Saudi Arabians which could indicate a common ancestry or some recent ancestral influx from the Arabian peninsula.[157]

A study found that the Palestinians, like Jordanians, Syrians, Iraqis, Turks, and Kurds have what appears to be Female-Mediated gene flow in the form of Maternal DNA Haplogroups from sub-Saharan Africa. Of individuals tested, 1-15% carried haplogroups that originated in sub-Saharan Africa. These results are consistent with female migration from eastern Africa into Near Eastern communities within the last few thousand years. There have been many opportunities for such migrations during this period. However, the most likely explanation for the presence of predominantly female lineages of African origin in these areas is that they may trace back to women brought from Africa as part of the Arab slave trade, assimilated into the areas under Arab rule as a result of miscegenation and manumission.[158]

According to a 2002 study by Nebel and colleagues[159] the highest frequency of Eu10 (i.e. J1) (30%–62.5%) has been observed so far in various Muslim Arab populations in the Middle East.[160][161] The term "Arab," as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century BCE (Eph'al 1984).[162]

A 2013 study of Haber and al found that "The predominantly Muslim populations of Syrians, Palestinians and Jordanians cluster on branches with other Muslim populations as distant as Morocco and Yemen." The Authors explained that "religious affiliation had a strong impact on the genomes of the Levantines. In particular, conversion of the region's populations to Islam appears to have introduced major rearrangements in populations' relations through admixture with culturally similar but geographically remote populations leading to genetic similarities between remarkably distant populations." The authors also reconstructed the genetic structure of pre-Islamic Levant and found that "it was more genetically similar to Europeans than to Middle Easterners."[163]

Arabian origins of local Bedouin

The local Bedouins of Palestine are said to be ancestrally descended from Arabians, and not just culturally and linguistically Arabized peoples. Their dialects and pronunciation of qaaf as gaaf group them with other Bedouin across the Arab world. [citation needed] Arabic onomastic elements began to appear in Edomite inscriptions starting in the 6th century BC and the inscriptions of the Nabataeans who arrived in today’s Jordan in the 4th-3rd centuries BC.[164]

A few Bedouin are found as far north as Galilee; however, these seem to be much later arrival, rather than descendants of the Arabs that Sargon II settled in Samaria in 720 BC. The term "Arab," as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century BCE (Eph'al 1984).[162]

Following the Muslim conquest of Syria by Arabians, the formerly dominant languages of the area, Aramaic and Greek, were replaced by the Arabic language introduced by the new conquering administrative minority.[165] Among the cultural survivals from pre-Islamic times are the significant Palestinian Christian community, and smaller Jewish and Samaritan ones, as well as an Aramaic and possibly Hebrew sub-stratum in the local Palestinian Arabic dialect.[166]

Samaritan descent in Nablus

Much of the local Palestinian population in Nablus is believed to be descended from Samaritans who converted to Islam.[167] Even today, certain Nabulsi surnames including Muslimani, Yaish, and Shakshir among others, are associated with a Samaritan origin.[167]

Demographics

| Country or region | Population |

|---|---|

| West Bank and Gaza Strip | 3,761,000[168] |

| Jordan | 2,700,000[3] |

| Israel | 1,318,000[169] |

| Chile | 500,000 (largest community outside the Arab world)[170][171][172] |

| Syria | 434,896[173] |

| Lebanon | 405,425[173] |

| Saudi Arabia | 327,000[169] |

| The Americas | 225,000[174] |

| Egypt | 44,200[174] |

| Kuwait | (approx) 40,000[169] |

| Other Gulf states | 159,000[169] |

| Other Arab states | 153,000[169] |

| Other countries | 308,000[169] |

| TOTAL | 10,574,521 |

In the absence of a comprehensive census including all Palestinian diaspora populations, and those that have remained within what was British Mandate Palestine, exact population figures are difficult to determine. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) announced on 20 October 2004 that the number of Palestinians worldwide at the end of 2003 was 9.6 million, an increase of 800,000 since 2001.[175]

In 2005, a critical review of the PCBS figures and methodology was conducted by the American-Israel Demographic Research Group (AIDRG).[176] In their report,[177] they claimed that several errors in the PCBS methodology and assumptions artificially inflated the numbers by a total of 1.3 million. The PCBS numbers were cross-checked against a variety of other sources (e.g., asserted birth rates based on fertility rate assumptions for a given year were checked against Palestinian Ministry of Health figures as well as Ministry of Education school enrollment figures six years later; immigration numbers were checked against numbers collected at border crossings, etc.). The errors claimed in their analysis included: birth rate errors (308,000), immigration & emigration errors (310,000), failure to account for migration to Israel (105,000), double-counting Jerusalem Arabs (210,000), counting former residents now living abroad (325,000) and other discrepancies (82,000). The results of their research was also presented before the United States House of Representatives on 8 March 2006.[178]

The study was criticised by Sergio DellaPergola, a demographer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[179] DellaPergola accused the authors of the AIDRG report of misunderstanding basic principles of demography on account of their lack of expertise in the subject, but he also acknowledged that he did not take into account the emigration of Palestinians and thinks it has to be examined, as well as the birth and mortality statistics of the Palestinian Authority.[180] He also accused AIDRG of selective use of data and multiple systematic errors in their analysis, claiming that the authors assumed the Palestinian Electoral registry to be complete even though registration is voluntary, and they used an unrealistically low Total Fertility Ratio (a statistical abstraction of births per woman) to reanalyse that data in a "typical circular mistake." DellaPergola estimated the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza at the end of 2005 as 3.33 million, or 3.57 million if East Jerusalem is included. These figures are only slightly lower than the official Palestinian figures.[179]

In Jordan, there is no official census data for how many inhabitants are Palestinians, but estimates by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics cite a population range of 50% to 55%.[181][182] In 2009, at the request of the PLO, "Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to keep them from remaining permanently in the country."[183]

Many Palestinians have settled in the United States, particularly in the Chicago area.[184][185]