Arabs: Difference between revisions

Combine factbook references for Lebanon and Syria updating with current Christian population stats |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

Arabic-speaking populations in general are a highly heterogeneous collection of peoples, with different ancestral origins and identities. The ties that bind the Arab peoples are a veneer of shared heritage by virtue of common [[Arabic language|linguistic]], [[Arab culture|cultural]], and [[Pan-Arabism|political]] traditions. As such, Arab [[identity (social science)|identity]] is based on one or more of [[genealogy|genealogical]], [[natural language|linguistic]] or [[culture|cultural]] grounds,<ref name=Deng>Francis Mading Deng [http://books.google.com/books?id=iAPLHidx8MkC&pg=PA405 War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan], Brookings Institution Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8157-1793-8 p. 405</ref> although with competing identities often taking a more prominent role,<ref>Nicholas S. Hopkins, Saad Eddin Ibrahim eds., ''Arab society: class, gender, power, and development'', American University in Cairo Press, 1997, p.6</ref> based on considerations including regional, [[Nationalism|national]], [[clan]], [[Kinship|kin]], [[Sectarianism|sect]], and [[Tribalism|tribe]] affiliations and relationships. If the Arab panethnicity is regarded as a single population, then it constitutes one of the world's largest groups after [[Han Chinese]]. |

Arabic-speaking populations in general are a highly heterogeneous collection of peoples, with different ancestral origins and identities. The ties that bind the Arab peoples are a veneer of shared heritage by virtue of common [[Arabic language|linguistic]], [[Arab culture|cultural]], and [[Pan-Arabism|political]] traditions. As such, Arab [[identity (social science)|identity]] is based on one or more of [[genealogy|genealogical]], [[natural language|linguistic]] or [[culture|cultural]] grounds,<ref name=Deng>Francis Mading Deng [http://books.google.com/books?id=iAPLHidx8MkC&pg=PA405 War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan], Brookings Institution Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8157-1793-8 p. 405</ref> although with competing identities often taking a more prominent role,<ref>Nicholas S. Hopkins, Saad Eddin Ibrahim eds., ''Arab society: class, gender, power, and development'', American University in Cairo Press, 1997, p.6</ref> based on considerations including regional, [[Nationalism|national]], [[clan]], [[Kinship|kin]], [[Sectarianism|sect]], and [[Tribalism|tribe]] affiliations and relationships. If the Arab panethnicity is regarded as a single population, then it constitutes one of the world's largest groups after [[Han Chinese]]. |

||

The [[Arabian Peninsula]] itself was not entirely originally Arab, [[Arabization]] occurred in some parts of the Arabian Peninsula. For example, the [[language shift]] to Arabic displaced the indigenous [[South Semitic]] [[Old South Arabian]] languages of modern-day [[Yemen]] and southern [[Oman]]. These were the languages spoken in the civilisations of [[Sheba]], [[Ubar (civilazation)|Ubar]], [[Magan (civilization)|Magan]], [[Dilmun]], and [[Meluhha]]—which were spread via migrants from the Arabian peninsula, together with written script, in the 8th and 7th centuries BC to the [[Horn of Africa]] ([[Ethiopia]], [[Eritrea]], [[Somalia]], and [[Djibouti]]). |

The [[Arabian Peninsula]] itself was not entirely originally Arab, [[Arabization]] occurred in some parts of the Arabian Peninsula. For example, the [[language shift]] to Arabic displaced the indigenous [[South Semitic]] [[Old South Arabian]] languages of modern-day [[Yemen]] and southern [[Oman]]. These were the languages spoken in the civilisations of [[Sheba]], [[Ubar (civilazation)|Ubar]], [[Magan (civilization)|Magan]], [[Dilmun]], and [[Meluhha]]—which were spread via migrants from the Arabian peninsula, together with written script, in the 8th and 7th centuries BC to the [[Horn of Africa]] ([[Ethiopia]], [[Eritrea]], [[Somalia]], and [[Djibouti]]). Arab ethnic groups which inhabit or are adjacent to the [[Arabian plate]] includes [[Yemenis]], [[Omanis]], [[Emiratis]], [[Qataris]], [[Saudis]], [[Bahrainis]], [[Kuwaitis]], [[Iraqis]], [[Syrians]], [[Jordanians]], [[Palestinians]], [[Lebanese people|Lebanese]], and [[Egyptians]]. |

||

==Name== |

==Name== |

||

Revision as of 05:30, 11 July 2014

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, Arab and Arabians aren't clearly distinguished. Arabians are the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula. Arabs are the all inhabitant of the 20th century defined entity called the Arab World. (May 2014) |

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 420–450 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 400 million[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,500,000[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 87,227 (ethnic Arabs) 5,000,000 (Arab ancestry)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,500,000[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,870,000[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,658,000[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,600,000[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12,000,000[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Arabic, Modern South Arabian,[10][11] varieties of Arabic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Islam (predominantly Sunni, minority Shia) with Christianity and other religions as minorities | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other Semitic peoples and various Afro-Asiatic peoples | |||||||||||||||||||||

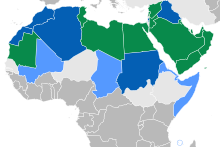

Arabs (Template:Lang-ar, ʿarab), also known as Arab people or Arabic-speaking people, are a major panethnic group.[12] They primarily inhabit Western Asia, North Africa, parts of the Horn of Africa, and other areas in the Arab world.

Arabic-speaking populations in general are a highly heterogeneous collection of peoples, with different ancestral origins and identities. The ties that bind the Arab peoples are a veneer of shared heritage by virtue of common linguistic, cultural, and political traditions. As such, Arab identity is based on one or more of genealogical, linguistic or cultural grounds,[13] although with competing identities often taking a more prominent role,[14] based on considerations including regional, national, clan, kin, sect, and tribe affiliations and relationships. If the Arab panethnicity is regarded as a single population, then it constitutes one of the world's largest groups after Han Chinese.

The Arabian Peninsula itself was not entirely originally Arab, Arabization occurred in some parts of the Arabian Peninsula. For example, the language shift to Arabic displaced the indigenous South Semitic Old South Arabian languages of modern-day Yemen and southern Oman. These were the languages spoken in the civilisations of Sheba, Ubar, Magan, Dilmun, and Meluhha—which were spread via migrants from the Arabian peninsula, together with written script, in the 8th and 7th centuries BC to the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and Djibouti). Arab ethnic groups which inhabit or are adjacent to the Arabian plate includes Yemenis, Omanis, Emiratis, Qataris, Saudis, Bahrainis, Kuwaitis, Iraqis, Syrians, Jordanians, Palestinians, Lebanese, and Egyptians.

Name

Originally, "Arabs" were synonymous with Arabians (inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula), until the Arabisation of people with no Arabian ancestry, mostly during the Abbasid Caliphate. Therefore all uses of the word "Arab" prior to the 7th century, and most those prior to the 13th century AD refer specifically to Arabians. Later uses of the word "Arab" could refer to anyone whose part of the wider linguistic and panethnic definitions of Arabs. The earliest documented use of the word "Arab" to refer to a people appears in the Monolith Inscription, an Akkadian language record of the 9th century BC Assyrian Conquest of Syria, which referred to Bedouins under King Gindibu who fought as part of a coalition opposed to the Assyrians.[15] Listed among the booty captured by the army of king Shalmaneser III of Assyria in the Battle of Qarqar are 1000 camels of "Gi-in-di-bu'u the ar-ba-a-a" or "[the man] Gindibu belonging to the ʕarab" (ar-ba-a-a being an adjectival nisba of the noun ʕarab[15]). ʕarab, with the Arabic letter "alif" in the second syllable, is still used today to describe Bedouins today, distinguishing them from ʕrab, used to describe non-Bedouin Arabic speakers.

The most popular Arab account holds that the word Arab came from an eponymous father called Yarab, who was supposedly the first to speak Arabic. Al-Hamdani had another view; he states that Arabs were called Gharab (West in Semitic) by Mesopotamians because Bedouins originally resided to the west of Mesopotamia; the term was then corrupted into Arab. Yet another view is held by Al-Masudi that the word Arabs was initially applied to the Ishmaelites of the "Arabah" valley.

In Biblical etymology, "Arab" (in Hebrew Arvi {{he:ערבי}}) comes both from the desert origin of the Bedouins it originally described (Arava means wilderness) and/or from the concept of mixed people. (Arev-rav - a large group of mixed people.) The root a-r-b has several additional meanings in Semitic languages—including "west/sunset," "desert," "mingle," "merchant," and "raven"—and are "comprehensible" with all of these having varying degrees of relevance to the emergence of the name. It is also possible that some forms were metathetical from ʿ-B-R "moving around" (Arabic ʿ-B-R "traverse"), and hence, it is alleged, "nomadic."

Identity

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Arab identity. (Discuss) (May 2014) |

Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity, and pre-dates the spread of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian kingdoms and Arab Jewish tribes. Today, however, most Arabs are Muslim.[16][17]), with a minority adhering to other faiths, largely Christianity, but also Druze and Baha'i.

Arabs are generally Sunni, Shia or Sufi Muslims, but currently, 7.1 percent to 10 percent of Arabs are Arab Christians.[18] This figure includes only Christians whose primary community language is today a variety of Arabic, and who identify as Arab.

Arab ethnic identity does not include Christian and other ethnic groups that retain non-Arabic languages and identities within the expanded Arab World. These include the Assyrians of Iraq and north east Syria, Armenians around the entire Near East, and Mandeans in Iraq—though many of these peoples speak Arabic as a first or second language. In addition, many Egyptian Copts and Lebanese Maronites espouse an Ancient Egyptian and Phoenician-Canaanite identity respectively, rather than an Arab one. A number of other peoples living in the Arab World are non-Arab, such as; Berbers, Kurds, Turks, Iranians, Azeris, Circassians, Shabaks, Turcomans, Romani, Chechens, Mhallami, Africans, South Asians, Samaritans, and Jews.

Today, the main unifying characteristic among Arabs is the Arabic language, a South Semitic language from the Afroasiatic language family. Modern Standard Arabic serves as the standardized and literary variety of Arabic used in writing, as well as in the most formal speech, although it is not spoken natively by the overwhelming majority of Arabs. Most Arabs who are functional in Modern Standard Arabic acquire it as a second language through education, while various varieties of Arabic are spoken as vernaculars by each distinct Arab group. Due to sociolinguistic reasons stemming from pan-Arab political and social considerations, however, these varieties are often regarded dialects rather than independent languages, despite the fact that most varieties of Arabic are not mutually intelligible, whether with each other or to Modern Standard Arabic. By contrast, neither the Maltese language is referred to as a variety of Arabic, nor are the Maltese people Arabs, despite the fact that the Maltese language is philologically a variety of Arabic in no greater or lesser extent than any of the other thus-defined Arabic varieties (sharing intelligibility with Tunisian Arabic), in addition to Malta itself lying on the African tectonic plate along with the other Arab-defined countries of North Africa. This anomaly owes to modern-day Malta being politically aligned and within the cultural sphere of influence of Europe rather than the Arab world, as was the case in Malta's earlier history.

During the Bronze Age, Iron Age and Classical Era there was no Arab presence in the areas encompassed by modern Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Iran, North Africa, Asia Minor or Kuwait.

The Arabs are first mentioned in the mid 9th century BC as a tribal people dwelling in the mid Arabian Peninsula subjugated by the north Mesopotamian based Assyrians. The Arabs appear to have remained largely under the vassalage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC), and then the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605-539 BC), Persian Achaemenid Empire (539-332 BC), Greek Macedonian/Seleucid Empire and Iranian Parthian Empires.

Arab tribes, most notably the Ghassanids and Lakhmids begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan from the mid 3rd century AD onwards, during the mid to later stages of the Roman Empire and Sassanid Empire. The Nabateans of Jordan appear to have been an Aramaic speaking ethnic mix of Canaanites, Arameans and Arabs. Thus, although a more limited difussion of Arabic culture and language was felt in some areas by these migrant minority Arabs in pre-Islamic times through Arab Christian kingdoms and Arab Jewish tribes, it was only after the rise of Islam in the mid-7th century that Arab culture, people and language began their wholesale spread from the central Arabian Peninsula (including the Syrian desert) through conquest and trade.

At the time of the Arab Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries AD, the population of Aramea and Phoenicia (modern Syria and Lebanon) was largely Aramean and Phoenician, with minorities of Greeks, Assyrians, Armenians and Romans also extant, as well as pre-Islamic Arabs in the south Syrian deserts. Israel-Palestine (ancient Israel, Judah and Samarra) and Jordan (ancient Moab, Edom and Ammon) were largely inhabited by native Jews, Samaritans, and other Canaanites, together with Arameans, Greeks and Nabateans. Egypt was largely populated by natives of Ancient Egyptian heritage together with a Greek minority, what had been Phoenician Carthage (modern Tunisia) by its mixed Phoenician-Berber population. A number of Germanic peoples such as the Vandals and Visigoths were also extant as rulers throughout North Africa (modern Libya, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco) at this time.

Arab cultures went through a mixing process. Therefore, every Arab country has cultural specificities that form a cultural mix that incorporates local novelties acquired after arabization. However, all Arab countries do also share a common culture in arts (music, literature, poetry, calligraphy...), cultural products (handicrafts, carpets, henne, bronze carving...), social behaviour, and relations (hospitality, codes of conduct among friends and family...), customs and superstitions, some dishes (Shorba, mloukhia), traditional clothing, and architecture.

Non-Arab Muslims, who are about 80 percent of the world's Muslim population, do not form part of the Arab world, but instead comprise what is the geographically larger, and more diverse, Muslim World.

In the USA, Arabs are classified as white by the U.S. Census, and have been since 1997.[19][20]

Arabic, the main unifying feature among Arabs, is a Semitic language originating in Arabia. From there it spread to a variety of distinct peoples across most of West Asia and North Africa,[21] resulting in their acculturation and eventual denomination as Arabs. Arabization, a culturo-linguistic shift, was often, though not always, in conjunction with Islamization, a religious shift.

With the rise of Islam in the 7th century, and as the language of the Qur'an, Arabic became the lingua franca of the Islamic world.[22] It was in this period that Arabic language and culture was widely disseminated with the early Islamic expansion, both through conquest and cultural contact.[23]

Arabic culture and language, however, began a more limited diffusion before the Islamic age, first spreading in West Asia beginning in the 2nd century, as Arab Christians such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Banu Judham began migrating north from Arabia into the Syrian Desert, south western Iraq and the Levant.[24][25]

In the modern era, defining who is an Arab is done on the grounds of one or more of the following two criteria:

- Genealogical: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the original inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula and the Syrian Desert (tribes of Arabia). This was the definition used until medieval times, for example by Ibn Khaldun, but has decreased in importance over time, as a portion of those of Arab ancestry lost their links with their ancestors' motherland. In the modern era, however, DNA tests have at times proved reliable in identifying those of Arab genealogical descent. For example, it has been found that the frequency of the "Arab marker" Haplogroup J1 collapses suddenly at the borders of Arabic speaking countries.[26]

- Linguistic: someone whose first language, and by extension cultural expression, is Arabic, including any of its varieties. This definition covers some than 420 million people (2014 estimate). Certain groups that fulfill this criterion reject this definition on the basis of non-Arab ancestry; such an example may be seen in the way that Egyptians identified themselves in the early 20th century.[27][28]

The relative importance of these factors is estimated differently by different groups and frequently disputed. Some combine aspects of each definition, as done by Palestinian Habib Hassan Touma,[29] who defines an Arab "in the modern sense of the word", as "one who is a national of an Arab state, has command of the Arabic language, and possesses a fundamental knowledge of Arab tradition, that is, of the manners, customs, and political and social systems of the culture." Most people who consider themselves Arab do so based on the overlap of the political and linguistic definitions.

The Arab League, a regional organization of countries intended to encompass the Arab world, defines an Arab as:

An Arab is a person whose language is Arabic, who lives in an Arabic-speaking country, and who is in sympathy with the aspirations of the Arabic-speaking peoples.[30]

According to Sadek Jawad Sulaimanis the former Ambassador of Oman to the United States:

The Arabs are defined by their culture, not by race; and their culture is defined by its essential twin constituents of Arabism and Islam. To most of the Arabs, Islam is their indigenous religion; to all of the Arabs, Islam is their indigenous civilization. The Arab identity, as such, is a culturally defined identity, which means being Arab is being someone whose mother culture, or dominant culture, is Arabism. Beyond that, he or she might be of any ancestry, of any religion or philosophical persuasion, and a citizen of any country in the world. Being Arab does not contradict with being non-Muslim or non-Semitic or not being a citizen of an Arab state.[31]

The relation of ʿarab and ʾaʿrāb is complicated further by the notion of "lost Arabs" al-ʿArab al-ba'ida mentioned in the Qur'an as punished for their disbelief. All contemporary Arabs were considered as descended from two ancestors, Qahtan and Adnan.

Versteegh (1997) is uncertain whether to ascribe this distinction to the memory of a real difference of origin of the two groups, but it is certain that the difference was strongly felt in early Islamic times. Even in Islamic Spain there was enmity between the Qays of the northern and the Kalb of the southern group. The so-called Sabaean or Himyarite language described by Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī (died 946) appears to be a special case of language contact between the two groups, an originally north Arabic dialect spoken in the south, and influenced by Old South Arabian.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

During the Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Arabs forged an Arab Empire (under the Rashidun and Umayyads, and later the Abbasids) whose borders touched southern France in the west, China in the east, Asia Minor in the north, and the Sudan in the south. This was one of the largest land empires in history. In much of this area, the Arabs spread Islam and the Arabic culture, science, and language (the language of the Qur'an) through conversion and cultural assimilation.

Two references valuable for understanding the political significance of Arab identity: Michael C. Hudson, Arab Politics: The Search for Legitimacy (Yale University Press, 1977), especially Chs. 2 and 3; and Michael N. Barnett, Dialogues in Arab Politics: Negotiations in Regional Order (Columbia University Press, 1998).

Subgroups

While Pan-Arabism and Arab nationalism subsume all Arabic-speaking populations under the notion of "Arabs", there are numerous sub-divisions, not all of which necessarily identify as ethnically Arab.

The Arabians form a strict subset of the ethnolinguistic group of "Arabs" discussed here. The name of Arab historically was synonymous with Bedouin. Although, most Arabians were sedentary (not nomadic) in pre-Islamic times.[citation needed] In some parts of the Arab World, the term Arab may still carry connotations of being Arabian, conflicting with the Pan-Arabist concept of ethnicity.

Arabians are most prevalent in the Arabian Peninsula, but are also found in large numbers in Mesopotamia (Arab tribes in Iraq), the Levant and Sinai (Negev Bedouin, Tarabin bedouin), as well as North Africa and the Sudan region.

- Arabian Peninsula

Arabs in the narrow sense are the indigenous Arabians (who trace their roots back to the tribes of Arabia) and their immediate descendant groups in the Levant and North Africa. Within the people of the Arabian Peninsula, distinction is made between:

- Pure Arabs or Qahtanian Arabs (العرب العاربة) from Yemen, taken to be descended from Ya‘rub bin Yashjub bin Qahtan.

- Arabized Arabs or ‘Adnani Arabs (العرب المستعربة), taken to be the descendants of Ishmael and the Jurhum tribe.

This traditional division of the Arabs of Arabia may have arisen at the time of early Muslim factional infighting during the Umayyad Caliphate.

Contrary to popular belief, most Arabians were sedentary (not nomadic) in pre-Islamic times.[citation needed]

Of the Arabian tribes that interacted with Muhammad, the most prominent was Banu Quraish. The Qur'aish sub-clan of Banu Hashim was the clan of Muhammad. During the period of Muslim conquests and the Golden Age of Islam, the political rulers of Islam were exclusively members of the Banu Quraish tribe.

- Iraq

The 150 Arab tribes in Iraq are grouped into federations (qabila), and divided into clans (fukhdh). The so-called Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq consist of numerous tribes, partly within the large Al-Muntafiq tribal alliance.

Iranian Arabs form a 2% minority in Iran. The largest group are the Ahwazi Arabs, including Banu Kaab, Bani Turuf and the Musha'sha'iyyah sect . Smaller groups are the Khamseh nomads in Fars Province and the Arabs in Khorasan.

- Syria and Levant

The Arabs of the Levant are traditionally divided into Qays and Yaman tribes. This tribal division is likewise taken ot date to the Umayyad period. The Yaman trace their origin to South Arabia or Yemen; they include Banu Kalb, Kindah, Ghassanids, and Lakhmids.[32] Since the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine, the Arabic-speaking population of Palestine has shed its formerly tribal structure and emerged as the Palestinian people.

- Africa

The Bedouin of western Egypt and eastern Libya are traditionally divided into Sa`ada and Murabtin, the Sa`ada group having higher social status. This may derive from a historical feudal system in which the Murabtin were vassals to the Sa`ada.

With the Muslim conquest of North Africa and the Sudan region, amalgamated populations emerged, now sometimes summarized under the terms Arab-Berber, Arabized Berber and Afro-Arab.

Egyptians are Arabic-speaking, but the question of their idenfitication as ethnically Arab has a long and complicated history of controversy.

The Arabic-speaking population of the Maghreb (Libyans, Algerians, Moroccans, Tunisians) is loosely divided into Arab-Berber for people of mixed Arab-Berber descent who embrace an Arab identity, and Arabized Berber for people of predominantly North African ancestry who retain a regional identity.

In Sudan, there are numerous Arab tribes, including the Shaigya, Ja'alin, Shukria, Rashaida, etc. in addition, there are Arabized or partially Arabized ethnic groups such as the Nubians, Copts, or Beja; they are sometimes united under the umbrella term of Sudanese Arabs. Arab slave trade in the Sudan region and West Africa created a clean division between Arabs and indigenous populations, and slavery in contemporary Africa substantially persists along these lines,[33] contributing to ethnic conflict in the region, such as the internal conflicts in Sudan, Northern Mali conflict, or the Islamist insurgency in Northern Nigeria.

Demographics

The total number of Arabic speakers living in the Arab nations is estimated at 366 million by the CIA Factbook (as of 2014). The estimated number of Arabs in countries outside the Arab League is estimated at 17.5 million, yielding a total of close to 384 million.

According to the International Organization for Migration, there are 13 million first-generation Arab migrants in the world, of which 5.8 reside in Arab countries, yielding a total of about 7 million people in the Arab diaspora.

Arab world

The table below shows the number of Arabic speaking people, including expatriates and some groups that may not be identified as ethnically Arab.

| Flag | Country | Total Population | % Arab | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | 86,895,099[34] | 90%[35] | The common consensus among Egyptians is that this classification is tied to them due to the use of Arabic as an official language in Egypt. The Egyptian dialect of Arabic include thousands of Coptic words. | |

| Algeria | 38,813,722[36] | 85%[36] | Most of Algerians have Arab or berber background. | |

| Morocco | 32,987,206[37] | 66%[38] | The high level of mixing between Arabs and Berbers makes differentiating between the two ethnicities in Morocco difficult. | |

| Iraq | 32,585,692[39] | 75-80%[39] | The remainder of the population in Iraq consists of Kurds (including Yazidis), Assyrians (including Chaldean Catholics), Turkmens, Shabaks, Armenians, Circassians, and Mandeans | |

| Saudi Arabia | 27,345,986[40] | 90%[40] | Most Saudis are ethnic Arabs. | |

| Sudan | 35,482,233[41] | 70%[41] | Arabs and Bedouins are by far the largest ethnic group, among 597 tribes. | |

| Yemen | 26,052,966[42] | 100%[43] | ||

| Syria | 17,951,639[44] | 90.3%[44] | The remainder population are primarily Christian groups such as Assyrians and Armenians, together with Kurds and Yazidis | |

| Tunisia | 10,937,521[45] | 98%[45] | ||

| Libya | 6,244,174[46] | 97%[46] | ||

| Jordan | 7,930,491[47] | 98%[47] | ||

| Eritrea | 6,086,495 | 2%[48] | Mainly Rashaida | |

| Lebanon | 5,882,562[49] | 95%[49] | ||

| Palestine | 4,225,710 | 89% | Gaza Strip: 1,763,387, 100% Palestinian Arab,[50] West Bank: 2,676,740, 83% Palestinian Arab and other[51] | |

| Kuwait | 3,030,000 | 80%[52] | ||

| UAE | 8,264,070 | 40%[53] | Less than 20% of the population in the Emirates are citizens, the majority are foreign workers and expatriates. Emirati citizens are ethnic Arabs. | |

| Oman | 3,219,775[54] | 90% | ||

| Mauritania | 3,516,806[55] | 80%[43] | The majority of Mauritania's population are ethnic Moors, an ethnicity with a mix of Arab and Berber ancestry, as well as a smaller Black African ancestry. Moors make up 80% of the population in Mauritania, the remaining 20% are members of a number of Black African ethnic groups.[43][dubious – discuss] | |

| Qatar | 2,123,160[56] | 40%[56] | The native population is a minority in Qatar, making up 20% of the population. The native population is ethnically Arab. An additional 20% of the population is made up of Arabs, mostly Egyptian and Palestinian workers. The remaining population is made up of other foreign workers. | |

| Bahrain | 1,314,089[57] | 50.7%[57] | 46.0% of the Bahrain's population are native Bahrainis. Bahrainis are ethnically Arabs.[58] 5.4% are Other Arabs (inc. GCC)[59] | |

| Djibouti | 804,000 | 4.5%[60] |

Migration and diaspora

| Flag | Country | Number of Arabs | Total Population | % Arabs | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 14,021,000 | 201,000,000 | 7% | [61] | |

| France | 5,500,000 | 65,350,000 | 7.7% | [3] | |

| Indonesia | 5,000,000 | 237,420,000 | 2.1% | [4] | |

| Argentina | 3,500,000 | 41,280,000 | 8.5% | [62] | |

| United States | 3,500,000 | 315,700,000 | 1.11% | [5] | |

| Sri Lanka | 1,870,000 | 20,260,000 | 9.23% | [6] | |

| Israel | 1,650,000 | 8,000,000 | 20.7% | [7] | |

| Venezuela | 1,600,000 | 29,000,000 | 5.5% | [63] | |

| Turkey | 1,600,000 | 75,620,000 | 2.1% | [64] | |

| Iran | 1,600,000 | 79,196,000 | 2.0% | [65] | |

| Chad | 1,400,000 | 10,329,208 | 12.3% | [66] | |

| Mexico | 1,100,000 | 115,300,000 | 0.95% | [67] | |

| Chile | 1,000,000 | 17,400,000 | 5.8% | [68] | |

| Spain | 800,000 | 46,750,000 | 2.4% | ||

| Italy | 760,000 | 60,920,000 | 1.2% | ||

| Colombia | 705,000 | 46,370,000 | 1.5% | [69] | |

| United Kingdom | 500,000 | 63,180,000 | 0.8% | [70] | |

| Germany | 500,000 | 82,000,000 | 0.6% | [71] | |

| Canada | 450,000 | 33,500,000 | 1.4% | [72] | |

| Netherlands | 480,000 | 16,750,000 | 2.8% | [73] | |

| Australia | 350,000 | 22,970,000 | 1.5% | [74] | |

| Greece | 250,000 | 10,900,000 | 2.2% |

According to the International Organization for Migration, there are 13 million first-generation Arab migrants in the world, of which 5.8 reside in Arab countries. Arab expatriates contribute to the circulation of financial and human capital in the region and thus significantly promote regional development.[citation needed] In 2009 Arab countries received a total of 35.1 billion USD in remittance in-flows and remittances sent to Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon from other Arab countries are 40 to 190 per cent higher than trade revenues between these and other Arab countries.[75]

The 250,000 strong Lebanese community in West Africa is the largest non-African group in the region.[76][77]

Arab traders have long operated in Southeast Asia and along the East Africa's Swahili coast. Zanzibar was once ruled by Omani Arabs.[78] Most of the prominent Indonesians, Malaysians, and Singaporeans of Arab descent are Hadhrami people with origins in southern Yemen in the Hadramawt coastal region.[79]

Central Asia and Caucasus

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Arab diaspora. (Discuss) (May 2014) |

In 1728, a Russian officer described a group of Sunni Arab nomads who populated the Caspian shores of Mughan (in present-day Azerbaijan) and spoke a mixed Turkic-Arabic language.[80] It is believed that these groups migrated to the Caucasus in the 16th century.[81] The 1888 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica also mentioned a certain number of Arabs populating the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire.[82] They retained an Arabic dialect at least into the mid-19th century,[83] but since then have fully assimilated with the neighbouring Azeris and Tats. Today in Azerbaijan alone, there are nearly 30 settlements still holding the name Arab (for example, Arabgadim, Arabojaghy, Arab-Yengija, etc.).

From the time of the Arab conquest of the Caucasus, continuous small-scale Arab migration from various parts of the Arab world occurred in Dagestan, which influenced local culture. Until the mid-20th century, some individuals in Dagestan still claimed Arabic as their native language. The majority of these lived in the village of Darvag, to the north-west of Derbent. The latest of these accounts dates to the 1930s.[81] Most Arab communities in southern Dagestan underwent linguistic Turkicisation, thus nowadays Darvag is a majority-Azeri village.[84][85]

According to the History of Ibn Khaldun, the Arabs that were once in Central Asia have been either killed or have fled the Tatar invasion of the region, leaving only the locals.[86] However, today many people in Central Asia identify as Arabs. Most Arabs of Central Asia are fully integrated into local populations, and sometimes call themselves the same as locals (for example, Tajiks, Uzbeks) but they use special titles to show their Arabic origin such as Sayyid, Khoja or Siddiqui.[87]

Iranian Arab communities are also found in Khuzestan Province.

South Asia

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Arab diaspora. (Discuss) (May 2014) |

There are only two communities with the self-identity Arab in India, the Chaush of the Deccan region and the Chavuse of Gujerat,[88][89] who are by and large descended of Hadhrami migrants who settled in these two regions in the 18th Centuries. However, both these communities no longer speak Arabic, although with the Chaush, there has been re-immigration to the Gulf States, and re-adoption of Arabic by these immigrants.[90] In South Asia, claiming Arab ancestry is considered prestigious, and many communities have origin myths with claim to an Arab ancestry. Examples include the Mappilla of Kerala, Labbai of Tamil Nadu and Kokan of Maharashtra. These communities all allege an Arab ancestry, but none speak Arabic and follow the customs and traditions of the Hindu majority.[91] Among Muslims of North India and Pakistan there are groups who claim the status of Sayyid, have origin myths that allege descent from the Prophet Mohammmad. None of these Sayyid families speak Arabic or follow Arab customs or traditions.[92]

Ceylon Moors are “the descendants of Arab traders (mainly from Hadhramawt in Yemen and Morocco) who espoused local women. They are a mixed race with Arab dominance and a considerable infusion of Sinhalese and Dravidian blood.” The later generation Arab traders married the descendants of the Arab settlers. Some families trace their ancestry to prominent Arab tribes like Banu Quraysh and Arab personalities like Caliph Abu Bakr As Siddiq, Prince Jamaldeen of Konya etc.

“The epithet (Moor), was borrowed (from the Spaniards) by the Portuguese, (the earliest colonizers of ‘Ceylon’ – as Sri Lanka was then known) who, after their discovery of the passage by the Cape of Good Hope, bestowed it indiscriminately upon the Arabs and their descendants, whom in the sixteenth century, found established as traders in every port on the Asian and African coast, and who had good reason to regard them as their most formidable competitors for the commerce of the East."

Alexander Johnston has recorded that:

"...the first Muslims who settled in the country, were, according to the tradition which prevails among their descendants, a portion of those Arabs of the House of Hashim who were driven from Arabia in the early part of the eighth century by the Umayyad Caliph Abd-al Malik bin Marwan, and who proceeding from the Euphrates southward, established settlements in the Concan, the southern parts of the Indian peninsula, Sri Lanka and Malacca. He adds that the division of them that came to Sri Lanka formed eight considerable settlements.”

Hussein says:

"Although it is likely that it was Arabic that was the spoken language of the early Arab settlers of the country, and perhaps of the early Moors whom they sired, it is today largely Arab Tamil getting replaced by Sinhala, as the ‘home language’, so to say, of the present-day Moor community. Arabic is today employed by them only as their liturgical language in their prayers and other religious observances. Arab Tamil is by far the predominant speech of the Moors.

"The Tamil spoken by the Moors is however not quite the same as the Tamil spoken by the Tamils of Jaffna and South India. Indeed, this peculiar dialect or rather patois of the Moors is derogatorily referred to as ‘Sona Tamil’ by conservative Tamil folk. This Sona Tamil speech seems to have largely derived from a South Indian Tamil patois.....

"It has also been considerably influenced by other languages such as Arabic, Hindustani, and Sinhala, all of which goes on to show that it approaches a sort of Creole, albeit considerably influenced by a Tamil dialect .....”

History

Pre-Islamic

Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to Arabic civilization in the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam in the 630s. The study of Pre-Islamic Arabia is important to Islamic studies as it provides the context for the development of Islam.

Semitic origin

There is a consensus that the Semitic peoples originated on the Arabian Peninsula.[93][94] It should be pointed out that these settlers were not Arabs or Arabic speakers. Early non-Arab Semitic peoples from the Ancient Near East, such as the Arameans, Akkadians (Assyrians and Babylonians), Amorites, Israelites, Eblaites, Ugarites and Canaanites, built civilizations in Mesopotamia, Eastern Arabia and the Levant; genetically, they often interlapped and mixed.[95] Slowly, however, they lost their political domination of the Near East due to internal turmoil and attacks by non-Semitic peoples. Although the Semites eventually lost political control of Western Asia to the Persian Empire, the Aramaic language remained the lingua franca of Assyria, Mesopotamia and the Levant. Aramaic itself was replaced by Greek as Western Asia's prestige language following the conquest of Alexander the Great, though it survives to this day among Assyrian Christians (aka Chaldo-Assyrians) and Mandeans in Iraq, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey and northwest Iran.

Early history

The first written attestation of the ethnonym "Arab" occurs in an Assyrian inscription of 853 BCE, where Shalmaneser III lists a King Gindibu of mâtu arbâi (Arab land) as among the people he defeated at the Battle of Karkar. Some of the names given in these texts are Aramaic, while others are the first attestations of Ancient North Arabian dialects. In fact several different ethnonyms are found in Assyrian texts that are conventionally translated "Arab": Arabi, Arubu, Aribi and Urbi. Many of the Qedarite queens were also described as queens of the aribi. The Hebrew Bible occasionally refers to Aravi peoples (or variants thereof), translated as "Arab" or "Arabian." The scope of the term at that early stage is unclear, but it seems to have referred to various desert-dwelling Semitic tribes in the Syrian Desert and Arabia.[citation needed] Arab tribes came into conflict with the Assyrians during the reign of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, and he records military victories against the powerful Qedar tribe among others.

Medieval Arab genealogists divided Arabs into three groups:

- "Ancient Arabs", tribes that had vanished or been destroyed, such as ʿĀd and Thamud, often mentioned in the Qur'an as examples of God's power to vanquish those who fought his prophets.

- "Pure Arabs" of South Arabia, descending from Qahtan. The Qahtanites (Qahtanis) are said to have migrated from the land of Yemen following the destruction of the Ma'rib Dam (sadd Ma'rib).

- The "Arabized Arabs" (musta`ribah) of Central Arabia (Najd) and North Arabia, descending from Ishmael the elder son of Abraham, through Adnan (hence, Adnanites). The Book of Genesis narrates that God promised Hagar to beget from Ishmael twelve princes and turn him to a great nation.(Genesis 17:20) The Book of Jubilees, in the other hand, claims that the sons of Ishmael intermingled with the 6 sons of Keturah, from Abraham, and their descendants were called Arabs and Ishmaelites:

And Ishmael and his sons, and the sons of Keturah and their sons, went together and dwelt from Paran to the entering in of Babylon in all the land towards the East facing the desert. And these mingled with each other, and their name was called Arabs, and Ishmaelites.

— Book of Jubilees 20:13

Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddima distinguishes between sedentary Arabian Muslims who used to be nomadic, and Bedouin nomadic Arabs of the desert. He used the term "formerly nomadic" Arabs and refers to sedentary Muslims by the region or city they lived in, as in Yemenis.[96] The Christians of Italy and the Crusaders preferred the term Saracens for all the Arabs and Muslims of that time.[97] The Christians of Iberia used the term Moor to describe all the Arabs and Muslims of that time.

Before Islam, most Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula were sedentary (not nomadic).[citation needed] Muslims of Medina referred to the nomadic tribes of the deserts as the A'raab, and considered themselves sedentary, but were aware of their close racial bonds. The term "A'raab' mirrors the term Assyrians used to describe the closely related nomads they defeated in Syria.

The Qur'an does not use the word ʿarab, only the nisba adjective ʿarabiy. The Qur'an calls itself ʿarabiy, "Arabic", and Mubin, "clear". The two qualities are connected for example in ayat 43.2–3, "By the clear Book: We have made it an Arabic recitation in order that you may understand". The Qur'an became regarded as the prime example of the al-ʿarabiyya, the language of the Arabs. The term ʾiʿrāb has the same root and refers to a particularly clear and correct mode of speech. The plural noun ʾaʿrāb refers to the Bedouin tribes of the desert who resisted Muhammad, for example in ayat 9.97, alʾaʿrābu ʾašaddu kufrān wa nifāqān "the Bedouin are the worst in disbelief and hypocrisy".

Based on this, in early Islamic terminology, ʿarabiy referred to the language, and ʾaʿrāb to the Arab Bedouins, carrying a negative connotation due to the Qur'anic verdict just cited. But after the Islamic conquest of the 8th century, the language of the nomadic Arabs became regarded as the most pure by the grammarians following Abi Ishaq, and the term kalam al-ʿArab, "language of the Arabs", denoted the uncontaminated language of the Bedouins.

Classical kingdoms

Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, texts give a clearer picture of the Arabs' emergence. The earliest are written in variants of epigraphic south Arabian musnad script, including the 8th century BCE Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, the 6th century BCE Lihyanite texts of southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout Arabia and the Sinai (not in reality connected with Thamud).

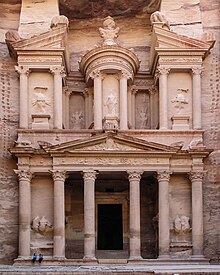

The Nabataeans were nomadic newcomers[citation needed] who moved into territory vacated by the Edomites – Semites who settled the region centuries before them. Their early inscriptions were in Aramaic, but gradually switched to Arabic, and since they had writing, it was they who made the first inscriptions in Arabic. The Nabataean Alphabet was adopted by Arabs to the south, and evolved into modern Arabic script around the 4th century. This is attested by Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BCE) and the many Arabic personal names in Nabataean inscriptions. From about the 2nd century BCE, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw (near Sulayyil) reveal a dialect no longer considered proto-Arabic, but pre-classical Arabic. Five Syriac inscriptions mentioning Arabs have been found at Sumatar Harabesi, one of which dates to the 2nd century CE.

Late kingdoms

The Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of non-Muslims out of Yemen to the north.

- The Ghassanids increased the Semitic presence in the then Hellenized Syria, the majority of Semites were Aramaic peoples. They mainly settled in the Hauran region and spread to modern Lebanon, Palestine and East Jordan.

Greeks and Romans referred to all the nomadic population of the desert in the Near East as Arabi. The Romans called Yemen "Arabia Felix".[98] The Romans called the vassal nomadic states within the Roman Empire "Arabia Petraea" after the city of Petra, and called unconquered deserts bordering the empire to the south and east Arabia Magna.

- The Lakhmids as a dynasty inherited their power from the Tanukhids, the mid Tigris region around their capital Al-Hira. They ended up allying with the Sassanids against the Ghassanids and the Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids contested control of the Central Arabian tribes with the Kindites with the Lakhmids eventually destroying Kinda in 540 after the fall of their main ally Himyar. The Persian Sassanids dissolved the Lakhmid dynasty in 602, being under puppet kings, then under their direct control.[99]

- The Kindites migrated from Yemen along with the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, but were turned back in Bahrain by the Abdul Qais Rabi'a tribe. They returned to Yemen and allied themselves with the Himyarites who installed them as a vassal kingdom that ruled Central Arbia from "Qaryah Dhat Kahl" (the present-day called Qaryat al-Faw) in Central Arabia. They ruled much of the Northern/Central Arabian peninsula, till they were destroyed by the Lakhmid king Al-Mundhir, and his son 'Amr

Islamic

Arab Caliphate

Rashidun Era (632-661)

After the death of Muhammad in 632, Rashidun armies launched campaigns of conquest, establishing the Caliphate, or Islamic Empire, one of the largest empires in history. It was larger and lasted longer than the previous Arab empires of Queen Mawia or the Palmyrene Empire, which was predominantly Syriac rather than Arab. The Rashidun state was a completely new state and not a mere imitation of the earlier Arab kingdoms such as the Himyarite, Lakhmids or Ghassanids, although it benefited greatly from their art, administration and architecture.

Umayyad Era (661-750)

In 661 the Caliphate fell into the hands of the Umayyad dynasty and Damascus was established as the Muslim capital. They were proud of their Arab ancestry and sponsored the poetry and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. They established garrison towns at Ramla, ar-Raqqah, Basra, Kufa, Mosul and Samarra, all of which developed into major cities.[101]

Caliph Abd al-Malik established Arabic as the Caliphate's official language in 686.[102] This reform greatly influenced the conquered non-Arab peoples and fueled the Arabization of the region. However, the Arabs' higher status among non-Arab Muslim converts and the latter's obligation to pay heavy taxes caused resentment. Caliph Umar II strove to resolve the conflict when he came to power in 717. He rectified the disparity, demanding that all Muslims be treated as equals, but his intended reforms did not take effect, as he died after only three years of rule. By now, discontent with the Umayyads swept the region and an uprising occurred in which the Abbasids came to power and moved the capital to Baghdad.

Umayyads expanded their Empire westwards capturing North Africa from the Byzantines. Prior to the Arab conquest, North Africa was inhibited by various people including Punics, Vandals and Greeks. It was not until the 11th century that the Maghreb saw a large influx of ethnic Arabs. Starting with the 11th century, the Arab bedouin Banu Hilal tribes migrated to the West. Having been sent by the Fatimids to punish the Berber Zirids for abandoning Shias, they travelled westwards. The Banu Hilal quickly defeated the Zirids and deeply weakened the neighboring Hammadids. Their influx was a major factor in the Arabization of the Maghreb. Although Berbers ruled the region until the 16th century (under such powerful dynasties as the Almoravids, the Almohads, Hafsids, etc.), the arrival of these tribes eventually helped Arabize much of it ethnically, in addition to the linguistic and political impact local non-Arabs. With the collapse of the Umayyad state in 1031 AD, Islamic Spain was divided into small kingdoms.

Abbassid Era (750-1513)

The Abbasids let a revolt against the Umayyads and defeated them in the Battle of the Zab effectively ending their rule in all part of the Empire except Al-Andalus. The Abbasids were descendants of Muhammad's uncle Abbas, but unlike the Umayyads they had the support of non-Arab subjects of the Umayyads.[101] The Abbasids ruled for 200 years before they lost their central control when Wilayas began to fracture; afterwards, in the 1190s, there was a revival of their power, which was ended by the Mongols, who conquered Baghdad and killed the Caliph. Members of the Abbasid royal family escaped the massacre and resorted to Cairo, which had broken from the Abbasid rule two years earlier; the Mamluk generals taking the political side of the kingdom while Abbasid Caliphs were engaged in civil activities and continued patronizing science, arts and literature.

Golden Age of Islam

The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to the newly founded city Baghdad. The Abbassids were influenced by the Qur'anic injunctions and hadith such as "The ink of the scholar is more holy than the blood of martyrs" stressing the value of knowledge. During this period the Muslim world became an intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established the "House of Wisdom" (Arabic: بيت الحكمة) in Baghdad. Rival Muslim dynasties such as the Fatimids of Egypt and the Umayyads of al-Andalus were also major intellectual centres with cities such as Cairo and Córdoba rivaling Baghdad.[103]

Ottoman Caliphate

Arabs were ruled by Ottoman sultans from 1513 to 1918. Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultanate in Cairo, and ended the Abbasid Caliphate when they assumed the title of Caliph. Arabs did not feel the change of administration because the Ottomans modeled their rule after the previous Arab administration systems.[citation needed] After World War I when the Ottoman Empire was overthrown by the British Empire, former Ottoman colonies were divided up between the British and French as League of Nations mandates.

Modern

Arabs in modern times live in the Arab world, which comprises 22 countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of the Horn of Africa. They are all modern states and became significant as distinct political entities after the fall and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1918).

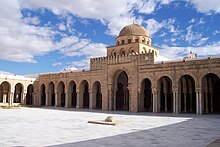

Religion

Arab Muslims are mostly Sunni with a minority of Shia, one exception being the Ibadis, who predominate in Oman and can be found as small minorities in Algeria and Libya (mostly Berbers). There are also a minority of Ahmadi Muslims.[104] Arab Christians generally follow Eastern Churches such as the Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, though a minority of Protestant Church followers also exists; The Copts and the Maronites, who are often associated with Arab people as well, follow the Coptic Church and Maronite Church accordingly. In Iraq most Christians are Assyrians rather than Arabs, and follow the Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox and Chaldean Church.[105] The Greek Catholic church and Maronite church are under the Pope of Rome, and a part of the larger worldwide Catholic Church. There are also Arab communities consisting of Druze and Baha'is.[106][107]

Christianity was the most common religion throughout all these regions at this time, although Judaism, Mandeanism, Sabianism, Manicheanism, Mithraism, Zoroastrianism, and remnants of Mesopotamian religion, Canaanite religion, Greco-Roman religion and Egyptian religion could still also be found. Linguistically, the major Semitic language prior to the Arab conquest was Aramaic, spoken in various forms.

Ancient times

Before the coming of Islam, most Arabs followed a pagan religion with a number of deities, including Hubal,[108] Wadd, Allāt,[109] Manat, and Uzza. A few individuals, the hanifs, had apparently rejected polytheism in favor of monotheism unaffiliated with any particular religion. Some tribes had converted to Christianity or Judaism. The most prominent Arab Christian kingdoms were the Ghassanid and Lakhmid kingdoms.[110] When the Himyarite king converted to Judaism in the late 4th century,[111] the elites of the other prominent Arab kingdom, the Kindites, being Himyirite vassals, apparently also converted (at least partly). With the expansion of Islam, polytheistic Arabs were rapidly Islamized, and polytheistic traditions gradually disappeared.[112][113]

Islam

Today, Sunni Islam dominates in most areas, overwhelmingly so in North Africa and the Horn of Africa. Shia Islam is dominant among the Arab population in Bahrain and Iraq. Substantial Shia populations exist in Lebanon, Yemen, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia,[114] northern Syria and the al-Batinah region in Oman. There are small numbers of Ibadi, Ahmadi and non-denominational Muslims too.[104]

Druze faith

The Druze community is concentrated in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Jordan. Many Druze claim independence from other major religions in the area and consider their religion more of a philosophy. Their books of worship are called Kitab Al Hikma (Epistles of Wisdom). They believe in reincarnation and pray to five messengers from God. In Israel, the Druze have a status aparte from the general Arab population, treated as a separate ethno-religious community.

Christianity

In pre-Islamic Arabia, Christianity had a prominent presence among several Arab communities, including the Bahrani people of Eastern Arabia, the Christian community of Najran, in parts of Yemen, and among certain northern Arabian tribes such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Taghlib and Tayy.

Christians make up 5.5% of the population of the Middle East.[18] A sizeable share of those are Arab Christians proper, and affiliated populations of Copts and Maronites. In Lebanon, Christians number about 40.5% of the population.[49] In Syria, Christians make up 10% of the population.[44] In West Bank and in Gaza Strip, Christians make up 8% and 0.7% of the populations, respectively.[50][51] In Egypt, Coptic Christians number about 10% of the population. In Iraq, Christians constitute 0.1% of the population.[115] In Israel, Arab Christians constitute 2.1% (roughly 9% of the Arab population).[116] Arab Christians make up 8% of the population of Jordan.[117] Most North and South American Arabs are Christian,[118] as are about half of Arabs in Australia who come particularly from Lebanon, Syria and Israel. One well known member of this religious and ethnic community is Saint Abo, martyr and the patron saint of Tbilisi, Georgia.[119] Arab Christians are living also in a holy Christian cities such as Nazareth, Bethlehem and the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem and yes, in many other villages with holy Christian sites.

Judaism

The Jewish tribes of Arabia were Arabian tribes professing the Jewish faith that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before and during the advent of Islam. It is not always clear whether they were originally Israelite in ancestry, genealogically Arab tribes that converted to Judaism, or a mixture of both. In Islamic tradition the Jewish tribes of the Hejaz were seen as the offspring of the ancient Israelites.[120] According to Muslim sources, they spoke a language other than Arabic, which Al-Tabari claims was Persian. This implies they were connected to the major Jewish center in Babylon.[121] Certain Jewish traditions records the existence of nomadic tribes such as the Rechabites that converted to Judaism in antiquity. The tribes collapsed with the rise of Islam, with many either converting or fleeing the Arab peninsula. Some of those tribes are thought to have merged into Yemenite Jewish community, while others, like the residents of Yatta consider themselves Islamized descendants of Khaybar, a Jewish tribe of Arabia.

Prior to the massive Sephardic emigrations to the Middle East in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Jewish communities of what are today Syria, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Egypt and Yemen were known by other Jewish communities as Musta'arabi Jews or "like Arabs". Also, prior to the emergence of the term Mizrahi, the term "Arab Jews" was sometimes used to describe Jews living in the Arab world.[citation needed] From the late 1940s to the early 1960s, following the creation of the state of Israel, most of descendants of these Jews fled or were expelled from their countries of birth and now live in Israel, France or elsewhere. The few remaining Jews in the Arab countries reside mostly in Morocco and Tunisia.

Modern Jews from Arab countries – mainly Mizrahi Jews, Yemenite Jews and Maghrebi Jews – are today usually not categorized as Arab, though there is still some debate on whether or not the term "Arabs" can be applied to them. Sociologist Sammy Smooha stated "This ("Arab Jews") term does not hold water. It is absolutely not a parallel to 'Arab Christian'".[122] Those who dispute the historicity of the term make the claim that Middle Eastern Jews are similar to Kurds, Assyrians, Berbers and other ancient Middle Eastern groups, who lived among the Arab societies as distinct minority groups with distinct identity and therefore are not categorized as Arabs. On the other hand, others gives examples of periods where the term "Arab-Jews" was applied in one form or another. Sociologist Philip Mendes asserts that before the anti-Jewish actions of the 1930s and 1940s, overall Iraqi Jews "viewed themselves as Arabs of the Jewish faith, rather than as a separate race or nationality".[citation needed]

Culture

Arab culture is a term that draws together the common themes and overtones found in the Arab countries, especially those of the Middle-Eastern countries. This region's distinct religion, art, and food are some of the fundamental features that define Arab culture.

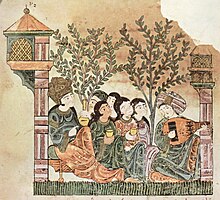

Art

Arabic Art includes a wide range or artistic components, it can be Arabic miniature, calligraphy or Arabesque.

Architecture

Arab Architecture has a deep diverse history, it dates to the dawn of the history in pre-Islamic Arabia. Each of it phases largely an extension of the earlier phase, it left also heavy impact on the architecture of other nations.

Music

Arabic music is the music of Arab people or countries, especially those centered on the Arabian Peninsula. The world of Arab music has long been dominated by Cairo, a cultural center, though musical innovation and regional styles abound from Morocco to Saudi Arabia. Beirut has, in recent years, also become a major center of Arabic music. Classical Arab music is extremely popular across the population, especially a small number of superstars known throughout the Arab world.

Regional styles of popular music include Algerian raï, Moroccan gnawa, Kuwaiti sawt, Egyptian el gil and Arabesque-pop music in Turkey.

Most historians agree that distinct forms of music existed in the Arabian peninsula in the pre-Islamic period between the 5th and 7th century AD. Arab poets of that time—called shu`ara' al-Jahiliyah (شعراء الجاهلية) or "Jahili poets", meaning "the poets of the period of ignorance"—recited poems with a high note. Tradition believes that Jinns revealed poems to poets, and music to musicians. The choir of the time was a pedagogic facility where educated poets recited poems. Singing was thought not the work of intellectuals, and was instead entrusted to women who learned to play instruments of the time, such as the drum, oud, or rebab, and perform the songs while respecting the poetic metre.

Literature

There is a small remnant of pre-Islamic poetry, but Arabic literature predominantly emerges in the Middle Ages, during the Golden Age of Islam.

Literary Arabic is derived from Classical Arabic, based on the language of the Qu'ran as it was analyzed by Arabic grammarians beginning in the 8th century.

A large portion of Arabic literature prior to the 20th century is in the form of poetry, and even prose from this period is either filled with snippets of poetry or is in the form of saj or rhymed prose. The ghazal or love poem had a long history being at times tender and chaste and at other times rather explicit. In the Sufi tradition the love poem would take on a wider, mystical and religious importance. Arabic epic literature was much less common than poetry, and presumably originates in oral tradition, written down from the 14th century or so. Maqama or rhymed prose is intermediate between poetry and prose, and also between fiction and non-fiction. Maqama was an incredibly popular form of Arabic literature, being one of the few forms which continued to be written during the decline of Arabic in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Arabic literature and culture declined significantly after the 13th century, to the benefit of Turkish and Persian.

A modern revival took place beginning in the 19th century, alongside resistance against Ottoman rule The literary revival is known as al-Nahda in Arabic, and was centered in Egypt and Lebanon.

Two distinct trends can be found in the nahda period of revival. The first was a neo-classical movement which sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres—such as the maqama—and works like One Thousand and One Nights. In contrast, a modernist movement began by translating Western modernist works—primarily novels—into Arabic.

A tradition of modern Arabic poetry was established by writers such as Francis Marrash, Ahmad Shawqi and Hafiz Ibrahim. Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab is considered to be the originator of free verse in Arabic poetry.

Genetics

Y-Chromosome

Haplogroup E1b1b is the most frequent haplogroup in Western Arabs (Maghrebis) while haplogroup J is the most frequent haplogroup in Eastern Arabs (Mashriq).[123]

The paternal ancestry found across all Arabic countries is Haplogroup J1, especially its major subclade J-P58, the haplogroup that spread with Arabic conquest in the 7th century. It was found that Haplogroup J1 occur at high frequencies among the Arabic-speaking populations of the Middle East and is the prevalent Y-chromosome lineage within the Near East. Haplogroup J1e (J-P58) is also associated with a Semitic linguistic common denominator, with the YCAII 22-22 allele state is closely associated with J1e.[124] J-P58 subclade of J1 is the single paternal lineage originating in the Near East of high frequency in Bedouins 70%, Yemenis 68%, Jordanians 55%, 55% of Palestinian Arabs, 48% of Omani People 34% of Tunisians, 35% of Algerians[125][126][127] , and its precipitations drop in frequency as one moves away from Saudi Arabia and the Near East. J-P58 include all the J1-CMH haplotypes and is YCAII=22-22 motif, both are found in Arabs and J1-Cohanim (Y-chromosomal Aaron).[128][129] The motif YCAII=22-22 characterize a monophyletic clad found in Arabs but less frequent in Ethiopian J1 and rare in Europe and Caucasus.[130][131] It has now been resolved that the Arabic clade J1-P58, L147.1 (the major clad of P58 and still the major clade of J1) include all CMH haplotypes and is YCAII=22-22 (both specific to Arabs and J1-Cohanim) was the J1 clade that spread far and wide by the Islamic conquest.[132] Both Qahtanite and Adnanite Arabs are J1-P58 haplogroup since the Arabs of North Africa like Algeria (known to have Qahtanite lineage from the Arab conquest and Adnanite lineage from Bani Hilal and bani Sulaim migration to North Africa in the 10th century by the Fatimides, yet only E of the Berber and J1 are found in Arabs of North Africa and this J1 is marked by CMH and the motif YCAII=22-22. The J2 in Algerian Arabs is minor 3% and is of the rare J2-M67 of Chechnya, rarely found in other Arabic countries and non existent in Arabian Peninsula and Yemen.[133][134] The Arab conquest appears to have had a dramatic influence on the East and South Mediterranean coasts. The presence of Arab Y chromosome lineages in the Middle East suggests that most have experienced substantial gene flow from the Arabian peninsula.[135]

Maternal Chromosome

The Maternal ancestral lineages of Arabic countries are very diverse. The original Historical Maternal ancestral Haplogroups of the Near East were Mt (Maternal) L3 Haplogroup and Mt HV1 haplogroup that are still high in Yemen, while in Greater Syria there is a European Maternal gene flow. In the Arabic West the dominant Maternal lineage is the rare Scandinavian European U8 haplogroup probably came with the Vandals when escaped from Spain from the Visigoths.[136][137][138]

Other Chromosomes

Many of the pronounced genetic deficiencies in Arabs (causing genetic disorders specific to Arabs) are located on HLA segment on chromosome 6. This same segment mutations are also markers of Arabs in Genealogical and forensic profiling tests and studies. Such studies as: Arab population data on the PCR-based loci: HLA [139] HLA polymorphism in Saudi.[140] Other mixed DNA studies on Arabic populations[136][137][138][141][142]

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (August 2013) |

- Notes

- ^ Margaret Kleffner Nydell Understanding Arabs: A Guide For Modern Times, Intercultural Press, 2005, ISBN 1931930252, page xxiii, 14

- ^ total population 450 million, CIA Factbook estimates an Arab population of 450 million, see article text.

- ^ a b France's ethnic minorities: To count or not to count. The Economist (2009-03-26). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ a b Hadramaut dan Para Kapiten Arab

- ^ a b "The Arab American Institute". Aaiusa.org. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ a b "A2 : Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- ^ a b "65th Independence Day - More than 8 Million Residents in the State of Israel" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 14 April 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ http://www.syria-today.com/index.php/january-2009/105-society/375-suweida-sways-to-the-sound-of-salsa-

- ^ http://www.brazzil.com/2004/html/articles/sep04/p118sep04.htm-

- ^ Kister, M.J. "Ķuāḍa." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 10 April 2008: "The name is an early one and can be traced in fragments of the old Arab poetry. The tribes recorded as Ķuḍā'ī were: Kalb [q.v.], Djuhayna, Balī, Bahrā' [q.v.], Khawlān [q.v.], Mahra, Khushayn, Djarm, 'Udhra [q.v.], Balkayn [see al-Kayn ], Tanūkh [q.v.] and Salīh"

- ^ Serge D. Elie, "Hadiboh: From Peripheral Village to Emerging City", Chroniques Yéménites: "In the middle, were the Arabs who originated from different parts of the mainland (e.g., prominent Mahrî tribes10, and individuals from Hadramawt, and Aden)". Footnote 10: "Their neighbours in the West scarcely regarded them as Arabs, though they themselves consider they are of the pure stock of Himyar."

- ^ Ghazi Omar Tadmouri (17 March 2011). "Genetic Disorders in Arabs" (PDF). Centre for Arab Genomic Studies. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Francis Mading Deng War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan, Brookings Institution Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8157-1793-8 p. 405

- ^ Nicholas S. Hopkins, Saad Eddin Ibrahim eds., Arab society: class, gender, power, and development, American University in Cairo Press, 1997, p.6

- ^ a b Jan Retsö The Arabs in antiquity: their history from the Assyrians to the Umayyads, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0-7007-1679-3, p. 105, 119, 125-127.

- ^ Ori Stendel. The Arabs in Palestine. Sussex Academic Press. p. 45. ISBN 1898723249. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Mohammad Hassan Khalil. Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others. Oxford University Press. p. 297. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b Andrea Pacini, ed. (1998). Christian Communities in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829388-7.

- ^ US Census, "About Race"

- ^ US Census, "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin 2010"

- ^ "Arab". Dictionary.reference.com. 22 March 1945. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chegne, Anwar G. (Autumn 1965). "Arabic: Its Significance and Place in Arab-Muslim Society". Middle East Journal (19): 447–470.

- ^ "Islam and the Arabic language". Islam.about.com. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Banu Judham migration". Witness-pioneer.org. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ghassanids Arabic linguistic influence in Syria". Personal.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ (Regueiro et al.) 2006; found agreement by (Battaglia et al.) 2008

- ^ Jankowski, James. "Egypt and Early Arab Nationalism" in Rashid Kakhlidi, ed., Origins of Arab Nationalism, pp. 244–245

- ^ Quoted in Dawisha, Adeed. Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. 2003, ISBN 0-691-12272-5, p. 99

- ^ 1996, p.xviii

- ^ Dwight Fletcher Reynolds, Arab folklore: a handbook, (Greenwood Press: 2007), p.1.

- ^ Sadek Jawad Sulaiman, The Arab Identity. Sadek Jawad Sulaiman. Al-Hewar/The Arab-American Dialogue Winter 2007. Chairman of Al-Hewar Center's Advisory Board.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State p.33 Routledge, Jun 17, 2013 ISBN 1134531133

- ^ Hall, Bruce S., A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600-1960. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Egypt". 22 June 2014.

- ^ Levinson 1998, p. 126

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Algeria". 20 March 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Morocco". 20 June 2014.

- ^ Levinson 1998, p. 152

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Iraq". 20 March 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Saudi Arabia". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Sudan". 20 June 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Yemen". 20 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Levinson 1998, p. 150

- ^ a b c "CIA World Factbook: Syria". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Tunisia". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Libya". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Jordan". 20 June 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Eritrea". 19 October 2012.

- ^ a b c "CIA World Factbook: Lebanon". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Gaza Strip". 3 November 2013.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: West Bank". 3 November 2013.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Kuwait". 17 May 2011.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: United Arab Emirates". 20 June 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Oman". 22 June 2014.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Mauritania". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Qatar". 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b "CIA World Factbook: Bahrain". 23 June 2014.

- ^ Levinson 1998, p. 204

- ^ "General Tables". Bahraini Census 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Languages of Djibouti". Ethnologue. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200505/the.arabs.of.brazil.htm

- ^ "الهجرة السورية اللبنانية إلى الأرجنتين". Fearab.org.ar. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Suweida Sways to the Sound of Salsa". Retrieved 24 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Joshua Project: Ethnic People Groups of Turkey

- ^ "Iran". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Iran". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ben Cahoon. "World Statesmen.org". World Statesmen.org. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Template:Es icon En Chile viven unas 700.000 personas de origen árabe y de ellas 500.000 son descendientes de emigrantes palestinos que llegaron a comienzos del siglo pasado y que constituyen la comunidad de ese origen más grande fuera del mundo árabe.

- ^ Colombia awakens to the Arab world

- ^ العرب البريطانيون، تأليف الدكتور أنطوني ماك روي

- ^ http://www.cz-herborn.de/arabische/

- ^ "إحصائيات كندا: الجمهرة وفقًا للأصول العرقية، في كل محافظة وإقليم (إحصاء سنة 2006)".

- ^ "Dutch media perceived as much more biased than Arabic media - Media & Citizenship Report conducted by University of Utrecht" (PDF), Utrecht University, 10 September 2010, retrieved 29 November 2010

- ^ http://elecpress.monash.edu.au/pnp/free/pnpv7n4/v7n4_3price.pdf

- ^ Intra-Regional Labour Mobility in the Arab World, International Organization for Migration (IOM) Cairo

- ^ "Lebanese in west Africa: Far from home". The Economist. 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Tenacity and risk - the Lebanese in West Africa". BBC News. 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Zanzibar profile". BBC News. 18 July 2012.

- ^ "The world's successful diasporas". Managementtoday.co.uk. 3 April 2007.

- ^ Genko, A. The Arabic Language and Caucasian Studies. USSR Academy of Sciences Publ. Moscow-Leningrad. 8–109

- ^ a b Zelkina, Anna. Arabic as a Minority Language. Walter de Gruyter, 2000; ISBN 3-11-016578-3 p. 101

- ^ Baynes, Thomas Spencer (ed). "Transcaucasia." Encyclopædia Britannica. 1888. p. 514

- ^ Golestan-i Iram by Abbasgulu Bakikhanov. Translated by Ziya Bunyadov. Baku: 1991, p. 21

- ^ Seferbekov, Ruslan. Characters Персонажи традиционных религиозных представлений азербайджанцев Табасарана.

- ^ Stephen Adolphe Wurm et al. Atlas of languages of intercultural communication. Walter de Gruyter, 1996; p. 966

- ^ History of Ibn Khaldun

- ^ Arabic As a Minority Language By Jonathan Owens, pg. 184

- ^ People of India: Vol. XIII: Andhra Pradesh (3 Parts-Set)Edited by D.L. Prasada Rao, N.V.K. Rao and S. Yaseen Saheb, Affiliated East-West Press

- ^ People of India: Volume XXII: Gujarat (3 Parts-Set) : Edited by R.B. Lal, P.B.S.V. Padmanabham, Gopal Krishan and Md. Azeez Mohidden, Popular Prakashan for ASI, 2003

- ^ Muslim society in transition Javed, Arifa Kulsoom ISBN/ISSN81-7169-096-3

- ^ Frontiers of embedded Muslim communities in India / editor, Vinod K. Jairath ISBN/ISSN04156688839780415668880

- ^ Muslim caste in Uttar Pradesh: (a study of culture contact) by Ansari, G, (Ghaus)

- ^ A history of the Babylonians and Assyrians, George Stephen Goodspeed. p.54

- ^ Cragg, 1991, p. 13.

- ^ "Journal of Semitic Studies Volume 52, Number 1". Pnas.org. 6 June 2000. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Levity.com, Islam". Levity.com. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "www.eyewitnesstohistory.com". www.eyewitnesstohistory.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dionysius Periegetes’ World Maps

- ^ Harold Bailey The Cambridge history of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods, Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 0-521-20092-X p. 59

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth Historic cities of the Islamic world, Brill, Leyde, 2007, ISBN 90-04-15388-8 p. 264

- ^ a b Lunde, Paul (2002). Islam. New York: Dorling Kindersley Publishing. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0-7894-8797-7.

- ^ John Joseph Saunders, A history of medieval Islam, Routledge, 1965, page 13

- ^ Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pg 26–38 ISBN 0-8157-3283-X

- ^ a b See, for example:

- Ori Stendel. The Arabs in Israel. Sussex Academic Press. p. 45. ISBN 1898723249. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Mohammad Hassan Khalil. Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others. Oxford University Press. p. 297. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ United Networks. "CHRISTIANS (in the Arab world)". Medea.be. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ The Bahá'í World Centre: Focal Point for a Global Community, The Bahá'í International Community, archived from the original on 29 June 2007, retrieved 2 July 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Shishakli and the Druzes: Integration and Intransigence"

- ^ "Is Hubal The Same As Allah?". Islamic-awareness.org. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dictionary of Ancient Deities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514504-6.

- ^ "From Marib The Sabean Capital To Carantania". Buzzle.com. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Msn Encarta entry on Himyarites. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- ^ "History of Islam". Mnsu.edu. 6 January 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion". Cqpress.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lionel Beehner. "Shia Muslims in the Mideast". Cfr.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Arab Christians – Who are they?. Arabicbible.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-03.

- ^ "CIA The World Factbook – Israel". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CIA The World Factbook – Jordan". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Arab American Institute | Arab Americans". Aaiusa.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.