MDMA: Difference between revisions

Infinitarian (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

===Immediate effects=== |

===Immediate effects=== |

||

The most serious short-term physical health risks of MDMA are [[hyperthermia]] and [[dehydration]].<ref name="Acute amph toxicity" /><ref name="Hyponatremia" /> Cases of life-threatening or fatal [[hyponatremia]] (excessively low sodium concentration in the blood) have developed in MDMA users attempting to prevent dehydration by consuming excessive amounts of water without replenishing [[electrolytes]].<ref name="Acute amph toxicity" /><ref name="Hyponatremia" /><ref name="hyperpyrexia">{{cite journal | author = Michael White C | title = How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms | journal = J Clin Pharmacol | volume = 54 | issue = 3 | pages = 245–52 | date = March 2014 | pmid = 24431106 | doi = 10.1002/jcph.266 | quote = Hyponatremia can occur from free water uptake in the collecting tubules secondary to the ADH effects and from over consumption of water to prevent dehydration and overheating. ... Hyperpyrexia resulting in rhabdomyolysis or heat stroke has occurred due to serotonin syndrome or enhanced physical activity without recognizing clinical clues of overexertion, warm temperatures in the clubs, and dehydration.1,4,9 ... Hepatic injury can also occur secondary to hyperpyrexia with centrilobular necrosis and microvascular steatosis.}}</ref> |

The most serious short-term physical health risks of MDMA are [[hyperthermia]] and [[dehydration]].<ref name="Acute amph toxicity" /><ref name="Hyponatremia" /> Cases of life-threatening or fatal [[hyponatremia]] (excessively low sodium concentration in the blood) have developed in MDMA users attempting to prevent dehydration by consuming excessive amounts of water without replenishing [[electrolytes]].<ref name="Acute amph toxicity" /><ref name="Hyponatremia" /><ref name="hyperpyrexia">{{cite journal | author = Michael White C | title = How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms | journal = J Clin Pharmacol | volume = 54 | issue = 3 | pages = 245–52 | date = March 2014 | pmid = 24431106 | doi = 10.1002/jcph.266 | quote = Hyponatremia can occur from free water uptake in the collecting tubules secondary to the ADH effects and from over consumption of water to prevent dehydration and overheating. ... Hyperpyrexia resulting in rhabdomyolysis or heat stroke has occurred due to serotonin syndrome or enhanced physical activity without recognizing clinical clues of overexertion, warm temperatures in the clubs, and dehydration.1,4,9 ... Hepatic injury can also occur secondary to hyperpyrexia with centrilobular necrosis and microvascular steatosis.}}</ref> |

||

Even without excessive water intake, even low doses of MDMA can increase water retention through [[SIADH]], <ref>{{cite web|title=The Agony of Ecstasy: MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) and the Kidney|url=http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/3/6/1852.full}}</ref> so that water intake must be restricted (unless heavy sweating occurs). <ref>{{cite web|title=Polydipsia as another mechanism of hyponatremia after ‘ecstasy’ (3,4 methyldioxymethamphetamine) ingestion|url=http://journals.lww.com/euro-emergencymed/Abstract/2004/10000/Polydipsia_as_another_mechanism_of_hyponatremia.14.aspx}}</ref> The resultant hypervolumia can simultaneously cause both dilutional hyponatremia (which can cause seizures) and hypertension (which can cause stroke). In the case of excessive water intake, salt can be administered to increase osmotic pressure, but while this improves hyponatremia it can also further worsen hypertension. Either is associated with a sensation of intracranial pressure, either in the brain's arteries as in hypertension, or in the brain's tissues as in hyponatremia. |

|||

The immediate adverse effects of MDMA use can include: |

The immediate adverse effects of MDMA use can include: |

||

Revision as of 12:26, 17 June 2015

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3,4-MDMA, Ecstasy, Molly |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | MDMA |

| Dependence liability | Physical: none Psychological: moderate[1] |

| Addiction liability | Moderate[2] |

| Routes of administration | Oral, sublingual, insufflation, inhalation (vaporization), injection,[3] rectal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, CYP450 extensively involved, including CYP2D6 |

| Onset of action | Immediate |

| Elimination half-life | (R)-MDMA: 5.8 ± 2.2 hours[4] (S)-MDMA: 3.6 ± 0.9 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 193.24 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Boiling point | 105 °C (221 °F) at 0.4 mmHg (experimental) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

MDMA (contracted from 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) is a psychoactive drug of the substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamine and substituted amphetamine classes of drugs that is consumed primarily for its euphoric and empathogenic effects. Pharmacologically, MDMA acts as a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agent and reuptake inhibitor.

MDMA has become widely known as "ecstasy" (shortened to "E", "X", or "XTC"), usually referring to its tablet street form, although this term may also include the presence of possible adulterants. The UK term "Mandy" and the US term "Molly" colloquially refer to MDMA in a crystalline powder form that is relatively free of adulterants.[5][6] "Molly" can sometimes also refer to the related drugs methylone, MDPV, mephedrone or any other of the pharmacological group of compounds commonly known as bath salts.[12]

Possession of MDMA is illegal in most countries. Some limited exceptions exist for scientific and medical research. For 2012, the UNODC estimated between 9.4 and 28.24 million people globally used MDMA at least once in the past year. This was broadly similar to the number of cocaine, substituted amphetamine, and opioid users, but far fewer than the global number of cannabis users.[13] It is taken in a variety of contexts far removed from its roots in psychotherapeutic settings, and is commonly associated with dance parties (or "raves") and electronic dance music.[14]

Medical reviews have noted that MDMA has some limited therapeutic benefits in certain mental health disorders, but has potential adverse effects, such as neurotoxicity and cognitive impairment, associated with its use.[15][16] More research is needed in order to determine if its potential usefulness in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment outweighs the risk of persistent neuropsychological harm to a patient.[15][16]

Uses

Medical

MDMA currently has no accepted medical uses.[13][17]

Recreational

MDMA is often considered the drug of choice within the rave culture and is also used at clubs, festivals and house parties.[18] In the rave environment, the sensory effects from the music and lighting are often highly synergistic with the drug. The psychedelic amphetamine quality of MDMA offers multiple reasons for its appeals to users in the "rave" setting. Some users enjoy the feeling of mass communion from the inhibition-reducing effects of the drug, while others use it as party fuel because of the drug's stimulatory effects.[19]

MDMA is occasionally known for being taken in conjunction with psychedelic drugs the more common combinations include MDMA combined with LSD, MDMA with psilocybin mushrooms, and MDMA with ketamine. Many users use mentholated products while taking MDMA for its cooling sensation while experiencing the drug's effects. Examples include menthol cigarettes, Vicks VapoRub, NyQuil,[20] and lozenges.

Recreational effects

In general, MDMA users begin reporting subjective effects within 30 to 60 minutes of consumption, hitting a peak at about 75 to 120 minutes which plateaus for about 3.5 hours.[21]

The desired short-term psychoactive effects of MDMA include:

- Euphoria – a sense of general well-being and happiness[15][22]

- Increased sociability and feelings of communication being easy or simple[15][22]

- Entactogenic effects – increased empathy or feelings of closeness with others[15][22]

- A sense of inner peace[22]

- Mild hallucination (e.g., colors and sounds are enhanced and mild closed-eye visuals)[22]

- Enhanced sensation, perception, or sexuality[15][22]

Purity and adulterants

The average tablet contains 60–70 mg (base equivalent) of MDMA, usually as the hydrochloride salt.[17] Powdered MDMA is typically 30–40% pure, due to bulking agents (e.g., lactose) and binding agents.[17] Tablets sold as ecstasy sometimes only contain 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) instead of MDMA;[4][17] the proportion of seized ecstasy tablets with MDMA-like impurities has varied annually and by country.[17]

Adverse effects

Immediate effects

The most serious short-term physical health risks of MDMA are hyperthermia and dehydration.[22][23] Cases of life-threatening or fatal hyponatremia (excessively low sodium concentration in the blood) have developed in MDMA users attempting to prevent dehydration by consuming excessive amounts of water without replenishing electrolytes.[22][23][24]

Even without excessive water intake, even low doses of MDMA can increase water retention through SIADH, [25] so that water intake must be restricted (unless heavy sweating occurs). [26] The resultant hypervolumia can simultaneously cause both dilutional hyponatremia (which can cause seizures) and hypertension (which can cause stroke). In the case of excessive water intake, salt can be administered to increase osmotic pressure, but while this improves hyponatremia it can also further worsen hypertension. Either is associated with a sensation of intracranial pressure, either in the brain's arteries as in hypertension, or in the brain's tissues as in hyponatremia.

The immediate adverse effects of MDMA use can include: Template:Multicol-begin

- Dehydration[18][22][23]

- Hyperthermia[18][22][23]

- Bruxism (grinding and clenching of the teeth)[15][18][22]

- Increased wakefulness or insomnia[22]

- Increased perspiration and sweating[22][23]

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure[18][22][23]

After-effects

The effects that last up to a week[15][29] following cessation of moderate MDMA use include: Template:Multicol-begin

- Physical

- Psychological

- Anxiety or paranoia[29]

- Depression[15][29]

- Irritability[29]

- Impulsiveness[29]

- Restlessness[29]

- Memory impairment[15]

- Anhedonia[29]

Long-term effects

MDMA use has been shown to produce brain lesions, a form of brain damage, in the serotonergic neural pathways of humans and other animals.[2][4] In addition, long-term exposure to MDMA in humans has been shown to produce marked neurotoxicity in serotonergic axon terminals.[18][22][30] Neurotoxic damage to axon terminals has been shown to persist for more than two years.[30] Brain temperature during MDMA use is positively correlated with MDMA-induced neurotoxicity in animals.[18] Adverse neuroplastic changes to brain microvasculature and white matter also seem to occur in humans using low doses of MDMA.[18] Reduced gray matter density in certain brain structures has also been noted in human MDMA users.[18] In addition, MDMA has immunosuppressive effects in the peripheral nervous system, but pro-inflammatory effects in the central nervous system.[31] Babies of mothers who used MDMA during pregnancy exhibit impaired motor function at 4 months of age, which may reflect either a delay in development or a persistent neurological deficit.[16][32]

MDMA also produces persistent cognitive impairments in human users.[1][15][16] Impairments in multiple aspects of cognition, including memory, visual processing, and sleep have been noted in humans;[15][16] the magnitude of these impairments is correlated with lifetime ecstasy or MDMA usage.[1][15][16] Memory is significantly impacted by ecstasy use, which is associated with marked impairments in all forms of memory (e.g., long-term, short-term, working).[15][16]

Dependence and withdrawal

Some studies indicate repeated recreational users of MDMA have increased rates of depression and anxiety, even after quitting the drug.[33][34][35] Other meta analyses have reported possibility of impairment of executive functioning.[36] Approximately 60% of MDMA users experience withdrawal symptoms, including, but not limited to: fatigue, loss of appetite, depression, and trouble concentrating.[4] Tolerance is expected to occur with consistent MDMA use.[4]

Overdose

Overdose symptoms vary widely with MDMA; they can include:

| System | Minor or moderate overdose[28] | Severe overdose[28] |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Central nervous system |

||

| Musculoskeletal |

| |

| Respiratory | ||

| Urinary | ||

| Other |

|

Chronic use and addiction

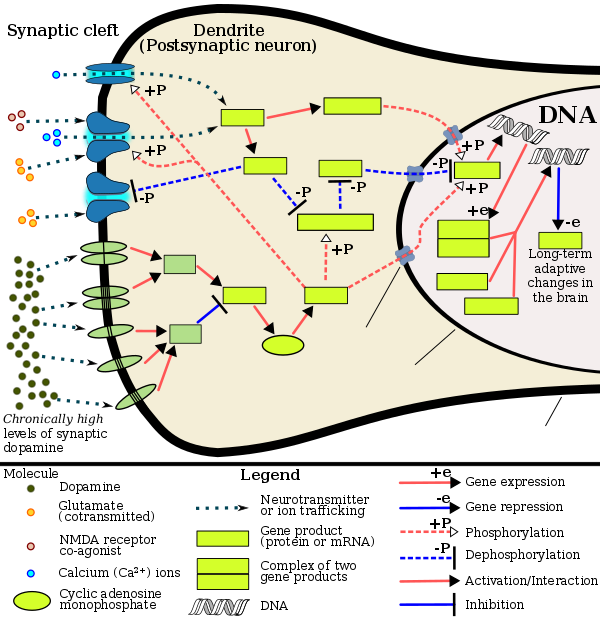

MDMA has been shown to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens.[47] Since MDMA releases dopamine in the mesocorticolimbic projection, the mechanisms by which it induces ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens are analogous to other psychostimulants.[47][48] Therefore, chronic use of MDMA at high doses can result in altered brain structure and drug addiction, which occur as a consequence of ΔFosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens.[48]

Interactions

A number of drug interactions can occur between MDMA and other drugs, including serotonergic drugs.[4][49] MDMA also interacts with drugs which inhibit CYP450 enzymes, like ritonavir (Norvir), particularly CYP2D6 inhibitors.[4] Concurrent use of MDMA with another serotonergic drug can result in a life-threatening condition called serotonin syndrome.[4] Severe overdose resulting in death has also been reported in people who took MDMA in combination with certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors,[4] such as phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate), or moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix).[50]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

MDMA acts primarily as a presynaptic releasing agent of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, which arises from its activity at trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2).[4][51][52] MDMA is a monoamine transporter substrate (i.e., a substrate for DAT, NET, and SERT), so it enters monoamine neurons via these neuronal membrane transport proteins;[51] by acting as a monoamine transporter substrate, MDMA produces competitive reuptake inhibition at the neuronal membrane transporters (i.e., it competes with endogenous monoamines for reuptake).[51][53] MDMA inhibits both vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs), the second of which (VMAT2) is highly expressed within monoamine neurons at vesicular membranes.[52] Once inside a monoamine neuron, MDMA acts as a VMAT2 inhibitor and a TAAR1 agonist.[51][52] Inhibition of VMAT2 by MDMA results in increased concentrations of the associated neurotransmitter (serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine) in the cytosol of a monoamine neuron.[52][54] Activation of TAAR1 by MDMA triggers protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling events which then phosphorylates the associated monoamine transporters – DAT, NET, or SERT – of the neuron.[51] In turn, these phosphorylated monoamine transporters either reverse transport direction – i.e., move neurotransmitters from the cytosol to the synaptic cleft – or withdraw into the neuron, respectively producing neurotransmitter efflux and noncompetitive reuptake inhibition at the neuronal membrane transporters.[51]

In summary, MDMA enters monoamine neurons by acting as a monoamine transporter substrate.[51] MDMA activity at VMAT2 moves neurotransmitters out from synaptic vesicles and into the cytosol;[52] MDMA activity at TAAR1 moves neurotransmitters out of the cytosol and into the synaptic cleft.[51]

MDMA also has weak agonist activity at postsynaptic serotonin receptors 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors, and its more efficacious metabolite MDA likely augments this action.[55][56][57][58] A placebo-controlled study in 15 human volunteers found 100 mg MDMA increased blood levels of oxytocin, and the amount of oxytocin increase was correlated with the subjective prosocial effects of MDMA.[59](S)-MDMA is more effective in eliciting 5-HT, NE, and DA release, while (D)-MDMA is overall less effective, and more selective for 5-HT and NE release (having only a very faint efficacy on DA release).[60]

MDMA is a ligand at both sigma receptor subtypes, though its efficacies at the receptors have not yet been elucidated.[61]

Pharmacokinetics

(S)/(+)-enantiomer of MDMA (bottom)

MDMA reaches maximal concentrations in the blood stream between 1.5 and 3 hr after ingestion.[62] It is then slowly metabolized and excreted, with levels of MDMA and its metabolites decreasing to half their peak concentration over the next several hours.[63]

Metabolites of MDMA that have been identified in humans include 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-methamphetamine (HMMA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine (HMA), 3,4-dihydroxyamphetamine (DHA) (also called alpha-methyldopamine (α-Me-DA)), 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylacetone (MDP2P), and 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-hydroxyamphetamine (MDOH). The contributions of these metabolites to the psychoactive and toxic effects of MDMA are an area of active research. Sixty-five percent of MDMA is excreted unchanged in the urine (in addition, 7% is metabolized into MDA) during the 24 hours after ingestion.[64]

MDMA is known to be metabolized by two main metabolic pathways: (1) O-demethylenation followed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-catalyzed methylation and/or glucuronide/sulfate conjugation; and (2) N-dealkylation, deamination, and oxidation to the corresponding benzoic acid derivatives conjugated with glycine.[28] The metabolism may be primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 and COMT. Complex, nonlinear pharmacokinetics arise via autoinhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP2D8, resulting in zeroth order kinetics at higher doses. It is thought that this can result in sustained and higher concentrations of MDMA if the user takes consecutive doses of the drug.[65][non-primary source needed]

MDMA and metabolites are primarily excreted as conjugates, such as sulfates and glucuronides.[66] MDMA is a chiral compound and has been almost exclusively administered as a racemate. However, the two enantiomers have been shown to exhibit different kinetics. The disposition of MDMA may also be stereoselective, with the S-enantiomer having a shorter elimination half-life and greater excretion than the R-enantiomer. Evidence suggests[67] that the area under the blood plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was two to four times higher for the (R)-enantiomer than the (S)-enantiomer after a 40 mg oral dose in human volunteers. Likewise, the plasma half-life of (R)-MDMA was significantly longer than that of the (S)-enantiomer (5.8 ± 2.2 hours vs 3.6 ± 0.9 hours).[4] However, because MDMA excretion and metabolism have nonlinear kinetics,[68] the half-lives would be higher at more typical doses (100 mg is sometimes considered a typical dose[62]).

Physical and chemical properties

The free base of MDMA is a colorless oil that is insoluble in water.[17] The most common salt of MDMA is the hydrochloride salt;[17] pure MDMA hydrochloride is water-soluble and appears as a white or off-white powder or crystal.[17]

Synthesis

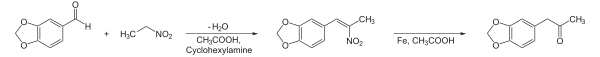

There are numerous methods available in the literature to synthesize MDMA via different intermediates.[69][70][71][72] The original MDMA synthesis described in Merck's patent involves brominating safrole to 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-bromopropane and then reacting this adduct with methylamine.[73][74] Most illicit MDMA is synthesized using MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone) as a precursor. MDP2P in turn is generally synthesized from piperonal, safrole or isosafrole.[13] One method is to isomerize safrole to isosafrole in the presence of a strong base, and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another method uses the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P intermediate with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been prepared, a reductive amination leads to racemic MDMA (an equal parts mixture of (R)-MDMA and (S)-MDMA).[citation needed]

Yield

Relatively small quantities of essential oil are required to make large amounts of MDMA. The essential oil of Ocotea cymbarum typically contains between 80 and 94% safrole. This allows 500 ml of the oil to produce between 150 and 340 grams of MDMA.[75]

Detection in body fluids

MDMA and MDA may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Some drug abuse screening programs rely on hair, saliva, or sweat as specimens. Most commercial amphetamine immunoassay screening tests cross-react significantly with MDMA or its major metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and separately measure each of these substances. The concentrations of MDA in the blood or urine of a person who has taken only MDMA are, in general, less than 10% those of the parent drug.[76][77][78]

History

Early research

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch. At the time, Merck was interested in developing substances that stopped abnormal bleeding. Merck wanted to avoid an existing patent held by Bayer for one such compound: hydrastinine. Köllisch developed a preparation of a hydrastinine analogue, methylhydrastinine, at the request of his coworkers, Walther Beckh and Otto Wolfes. MDMA was an intermediate compound in the synthesis of methylhydrastinine and Merck was not interested in its properties at the time.[79] On 24 December 1912, Merck filed two patent applications that described the synthesis of MDMA[80] and its subsequent conversion to methylhydrastinine.[81]

Merck records indicate its researchers returned to the compound sporadically. In 1927, Max Oberlin studied the pharmacology of MDMA and observed that its effects on blood sugar and smooth muscles were similar to those of ephedrine. Research was stopped "particularly due to a strong price increase of safrylmethylamine". Albert van Schoor performed simple toxicological tests with the drug in 1952, most likely while researching new stimulants or circulatory medications. Seven years later, in 1959, Wolfgang Fruhstorfer also synthesized MDMA while researching stimulants.[79]

Outside of Merck, other researchers began to investigate MDMA. In 1953 and 1954, the United States Army commissioned a study of toxicity and behavioral effects in animals injected with mescaline and several analogues, including MDMA. Conducted at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, these investigations were declassified in October 1969 and published in 1973.[82] A 1960 Polish paper describing the synthesis of MDMA was the first published scientific paper on the substance.[79]

Shulgin's research

Chemist Alexander Shulgin reported that he synthesized MDMA in 1965 while researching methylenedioxy compounds at Dow Chemical Company, but did not test the psychoactivity of the compound at this time. Around 1970, Shulgin sent instructions for N-methylated MDA (MDMA) synthesis to the founder of a Los Angeles chemical company who had requested them. This individual later provided these instructions to a client in the Midwest.[83] MDMA was being used recreationally in the Chicago area by August 1970.[83][84]

Shulgin first heard of the effects of N-methylated MDA in 1975 from a student acquaintance who reported "amphetamine-like content".[83] Around late May 1976, Shulgin again heard about the effects of N-methylated MDA,[83] this time from a graduate student in a medicinal chemistry group he advised at San Francisco State University.[85][86] Following the self-trials of a colleague at the University of San Francisco, Shulgin synthesized MDMA and tried it himself in September and October 1976.[83][85] Shulgin first reported on MDMA in a presentation at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland in December 1976.[83] Two years later, he and David E. Nichols published a report on the drug's psychotropic effect in humans. They described MDMA as inducing "an easily controlled altered state of consciousness with emotional and sensual overtones" comparable "to marijuana, to psilocybin devoid of the hallucinatory component, or to low levels of MDA".[87] Believing MDMA allowed users to strip away habits and perceive the world clearly, Shulgin called the drug "window".[88]

Shulgin took to occasionally using MDMA for relaxation, referring to it as "my low-calorie martini", and giving the drug to his friends, researchers, and other people whom he thought could benefit from it.[89] One such person was psychotherapist Leo Zeff, who had been known to use psychedelics in his practice. When he tried the drug in 1977, Zeff was so impressed with the effects of MDMA that he came out of his semi-retirement to promote its use in psychotherapy. Over the following years, Zeff traveled around the U.S. and occasionally to Europe, eventually introducing roughly four thousand psychotherapists to the use of MDMA in therapy.[90][91] Zeff named the drug "Adam", believing it put users in a state of primordial innocence.[85]

Rising use

In the late seventies and early eighties, MDMA spread through personal networks of psychotherapists, psychiatrists, users of psychedelics, and yuppies. Hoping MDMA could avoid criminalization like LSD and mescaline, psychotherapists and experimenters attempted to limit the spread of MDMA and information about it while conducting informal research.[92] By the time MDMA was criminalized in 1985, this network of MDMA users consumed an estimated 500,000 doses.[15][93]

A small recreational market for MDMA had developed by the late 1970s.[94] Into the early 1980s, production of MDMA was dominated by a small group of Boston chemists known as the "Boston group".[95] With demand for MDMA growing, the Southwest distributor for the "Boston group" started the "Texas group"[95] supported by several former cocaine dealers who had experienced MDMA.[93][94] The "Texas group" mass-produced MDMA in a Texas lab[92] or imported it from California[88] and marketed tablets using pyramid sales structures and toll-free numbers with credit card purchase options. Under the brand name "Sassyfras", MDMA was sold in brown bottles[92] and advertised as a "fun drug" and "good to dance to".[94] MDMA was openly distributed in Dallas area bars and nightclubs and became popular with yuppies, college students, and gays.[93] "Ecstasy" was recognized as slang for MDMA by 1981,[95] named by "Texas group" leader Michael Clegg,[96] over the alternative "empathy", for broader marketing appeal.[92]

Scheduling

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) began collecting information about MDMA in 1982 with the intention of banning the drug if enough evidence for abuse could be found.[93] By mid-1984, MDMA use was becoming more noticed. Bill Mandel reported on "Adam" in a June 10 San Francisco Chronicle article, but misidentified the drug as methyloxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA). In the next month, the World Health Organization identified MDMA as the only substance out of twenty phenethylamines to be seized a significant number of times.[92] The drug was first proposed for scheduling by the DEA on 27 July 1984 with a request for comments and objections.[97] The DEA was surprised when a number of physicians, therapists, and researchers objected to the proposed scheduling and requested a hearing.[95] In a Newsweek article published the next year, a DEA pharmacologist stated that the agency had been unaware of its use among psychiatrists.[98]

MDMA was classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the U.S. on 31 May 1985 on an emergency basis.[99] No double blind studies had yet been conducted as to the efficacy of MDMA for psychotherapy. However, as a result of several expert witnesses testifying that MDMA had an accepted medical usage, the administrative law judge presiding over the hearings recommended that MDMA was classified as a Schedule III substance. Despite this, DEA administrator John C. Lawn overruled and classified the drug as Schedule I.[95] Later Harvard psychiatrist Lester Grinspoon sued the DEA, claiming that the DEA had ignored the medical uses of MDMA, and the federal court sided with Grinspoon, calling Lawn's argument "strained" and "unpersuasive", and vacated MDMA's Schedule I status. Despite this, less than a month later Lawn reviewed the evidence and reclassified MDMA as Schedule I again, claiming that the expert testimony of several psychiatrists claiming over 200 cases where MDMA had been used in a therapeutic context with positive results could be dismissed because they weren't published in medical journals.[95][citation needed] In 1985 the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, which is its current status.[100]

Post-scheduling

In the late 1980s, MDMA began to be widely used in Ibiza,[101] the UK and other parts of Europe, becoming an integral element of rave culture and other psychedelic-influenced music scenes. Spreading along with rave culture, illicit MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later, in high schools. MDMA became one of the four most widely used illicit drugs in the U.S., along with cocaine, heroin, and cannabis.[88] According to some estimates as of 2004, only marijuana attracts more first time users in the U.S.[88]

After MDMA was criminalized, most medical use stopped, although some therapists continued to prescribe the drug illegally. Later,[when?] Charles Grob initiated an ascending-dose safety study in healthy volunteers. Subsequent legally-approved MDMA studies in humans have taken place in the U.S. in Detroit (Wayne State University), Chicago (University of Chicago), San Francisco (UCSF and California Pacific Medical Center), Baltimore (NIDA–NIH Intramural Program), and South Carolina, as well as in Switzerland (University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zürich), the Netherlands (Maastricht University), and Spain (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).[102]

"Molly", short for 'molecule', was recognized as a slang term for crystalline or powder MDMA in the 2000s.[103][104]

In 2010, the BBC reported that use of MDMA had decreased in the UK in previous years. This may be due to increased seizures during use and decreased production of the precursor chemicals used to manufacture MDMA. Unwitting substitution with other drugs, such as mephedrone and methamphetamine,[105] as well as legal alternatives to MDMA, such as BZP, MDPV, and methylone, are also thought to have contributed to its decrease in popularity.[106]

Society and culture

| Substance | Mean estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | 177.63 | 125.30 | 227.27 |

| Cocaine | 17.24 | 13.99 | 20.92 |

| MDMA | 18.75 | 9.4 | 28.24 |

| Opiates | 16.37 | 12.80 | 20.23 |

| Opioids | 33.04 | 28.63 | 38.16 |

| Substituted amphetamines |

34.40 | 13.94 | 54.81 |

Legal status

MDMA is legally controlled in most of the world under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and other international agreements, although exceptions exist for research and limited medical use. In general, the unlicensed use, sale or manufacture of MDMA are all criminal offences.

In Australia, MDMA was declared illegal in 1986 because of its harmful effects and potential for abuse. It is classed as a Schedule 9 Prohibited Substance in the country, meaning it is available for scientific research purposes only. Any other type of sale, use or manufacture is strictly prohibited by law. Permits for research uses on humans must be approved by a recognized ethics committee on human research.

In the United Kingdom, MDMA was made illegal in 1977 by a modification order to the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Although MDMA was not named explicitly in this legislation, the order extended the definition of Class A drugs to include various ring-substituted phenethylamines,[107] thereby making it illegal to sell, buy, or possess the drug without a licence. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking.

In the United States, MDMA is currently placed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[108] In a 2011 federal court hearing the American Civil Liberties Union successfully argued that the sentencing guideline for MDMA/ecstasy is based on outdated science, leading to excessive prison sentences.[109] Other courts have upheld the sentencing guidelines. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee explained its ruling by noting that "an individual federal district court judge simply cannot marshal resources akin to those available to the Commission for tackling the manifold issues involved with determining a proper drug equivalency."[110]

In the Netherlands, the Expert Committee on the List (Expertcommissie Lijstensystematiek Opiumwet) issued a report in June 2011 which discussed the evidence for harm and the legal status of MDMA, arguing in favor of maintaining it on List I.[110][111][112]

In Canada, MDMA is listed as a Schedule 1[113] as it is an analogue of amphetamine.[114] The CDSA was updated as a result of the Safe Streets Act changing amphetamines from Schedule III to Schedule I in March 2012.

Economics

Europe

In 2008 the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction noted that although there were some reports of tablets being sold for as little as €1, most countries in Europe then reported typical retail prices in the range of €3 to €9 per tablet, typically containing 25–65 mg of MDMA.[115] By 2014 the EMCDDA reported that the range was more usually between €5 and €10 per tablet, typically containing 57–102 mg of MDMA, although MDMA in powder form was becoming more common.[116]

North America

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime stated in its 2014 World Drug Report that U.S. ecstasy retail prices range from US$1 to $70 per pill, or from $15,000 to $32,000 per kilogram.[117] A new research area named Drug Intelligence aims to automatically monitor distribution networks based on image processing and machine learning techniques, in which an Ecstasy pill picture is analyzed to detect correlations among different production batches.[118] These novel techniques allow police scientists to facilitate the monitoring of illicit distribution networks.

Australia

MDMA is particularly expensive in Australia, costing A$15–A$30 per tablet. In terms of purity data for Australian MDMA, the average is around 34%, ranging from less than 1% to about 85%. The majority of tablets contain 70–85 mg of MDMA. Most MDMA enters Australia from the Netherlands, the UK, Asia, and the U.S.[119]

Controversy

Harm assessment

Some scientists such as David Nutt have disagreed with the categorization of MDMA with other drugs they view as more harmful. A 2007 UK study ranked MDMA 18th in harmfulness out of 20 recreational drugs. Rankings for each drug were based on the risk for acute physical harm, the propensity for physical and psychological dependency on the drug, and the negative familial and societal impacts of the drug. The authors did not evaluate or rate the negative impact of 'ecstasy' on the cognitive health of ecstasy users, e.g., impaired memory and concentration.[120][121] A later 2010 UK study which took into account impairment of cognitive functioning placed MDMA at number 17 out of 20 recreational drugs.[122]

Research

MAPS is currently funding pilot studies investigating the use of MDMA in PTSD therapy[123] and social anxiety therapy for autistic adults.[124]

A review of the safety and efficacy of MDMA as a treatment for various disorders, particularly PTSD, indicated that MDMA has therapeutic efficacy in some patients;[16] however, it emphasized that MDMA is not a safe medical treatment due to lasting neurotoxic and cognition impairing effects in humans.[16] The author noted that oxytocin and D-cycloserine are potentially safer co-drugs in PTSD treatment, albeit with limited evidence of efficacy.[16] This review and a second corroborating review by a different author both concluded that, because of MDMA's demonstrated potential to cause lasting harm in humans (e.g., serotonergic neurotoxicity and persistent memory impairment), "considerably more research must be performed" on its efficacy in PTSD treatment to determine if the potential treatment benefits outweigh its potential to cause long-term harm to a patient.[15][16]

References

- ^ a b c "3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

/EPIDEMIOLOGY STUDIES/ /Investigators/ compared the prevalence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version IV (DSM-IV) mental disorders in 30 current and 29 former ecstasy users, 29 polydrug and 30 drug-naive controls. Groups were approximately matched by age, gender and level of education. The current ecstasy users reported a life-time dose of an average of 821 and the former ecstasy users of 768 ecstasy tablets. Ecstasy users did not significantly differ from controls in the prevalence of mental disorders, except those related to substance use. Substance-induced affective, anxiety and cognitive disorders occurred more frequently among ecstasy users than polydrug controls. The life-time prevalence of ecstasy dependence amounted to 73% in the ecstasy user groups. More than half of the former ecstasy users and nearly half of the current ecstasy users met the criteria of substance-induced cognitive disorders at the time of testing. Logistic regression analyses showed the estimated life-time doses of ecstasy to be predictive of cognitive disorders, both current and life-time. ... Cognitive disorders still present after over 5 months of ecstasy abstinence may well be functional consequences of serotonergic neurotoxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) [Thomasius R et al; Addiction 100(9):1310-9 (2005)] **PEER REVIEWED** PubMed Abstract

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

MDMA has been proven to produce lesions of serotonin neurons in animals and humans.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy)". Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Luciano, Randy L.; Perazella, Mark A. (25 March 2014). "Nephrotoxic effects of designer drugs: synthetic is not better!". Nature Reviews Nephrology. 10 (6): 314–324. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.44. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy or Molly)". http://www.drugabuse.gov. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/01/nyregion/safer-electric-zoo-festival-brings-serious-beats-and-tight-security.html?_r=0

- ^ http://nypost.com/2013/09/12/drug-dealers-tricking-club-kids-with-deadly-bath-salts-not-molly/

- ^ http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324755104579073524185820910

- ^ http://www.mixmag.net/words/features/drug-molly-everything-but-the-girl

- ^ http://www.dailyprogress.com/news/dea-molly-use-akin-to-playing-russian-roulette/article_944a6886-1d8a-11e3-ac75-001a4bcf6878.html

- ^ [7][8][9][10][11]

- ^ a b c d Mohan, J, ed. (June 2014). World Drug Report 2014 (PDF). Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. pp. 2, 3, 123–152. ISBN 978-92-1-056752-7. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. World Health Organization. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-92-4-156235-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Meyer JS (2013). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives". Subst Abuse Rehabil. 4: 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. PMC 3931692. PMID 24648791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Parrott AC (2014). "The potential dangers of using MDMA for psychotherapy". J Psychoactive Drugs. 46 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.873690. PMID 24830184.

Human Psychopharmacology recently published my review into the increase in empirical knowledge about the human psychobiology of MDMA over the past 25 years (Parrott, 2013a). Deficits have been demonstrated in retrospective memory, prospective memory, higher cognition, complex visual processing, sleep architecture, sleep apnoea, pain, neurohormonal activity, and psychiatric status. Neuroimaging studies have shown serotonergic deficits, which are associated with lifetime Ecstasy/MDMA usage, and degree of neurocognitive impairment. Basic psychological skills remain intact. Ecstasy/MDMA use by pregnant mothers leads to psychomotor impairments in the children. Hence, the damaging effects of Ecstasy/MDMA were far more widespread than was realized a few years ago. ... Rogers et al. (2009) concluded that recreational ecstasy/MDMA is associated with memory deficits, and other reviews have come to similar conclusions. Nulsen et al. (2010) concluded that 'ecstasy users performed worse in all memory domains'. Laws and Kokkalis (2007) concluded that abstinent Ecstasy/MDMA users showed deficits in both short-term and long-term memory, with moderate to large effects sizes. Neither of these latter reviews suggested that the empirical literature they were reviewing was of poor quality (Laws and Kokkalis, 2007; Nulsen et al., 2010).

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy')". EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347.

MDMA has become a popular recreational drug of abuse at nightclubs and rave or techno parties, where it is combined with intense physical activity (all-night dancing), crowded conditions (aggregation), high ambient temperature, poor hydration, loud noise, and is commonly taken together with other stimulant club drugs and/or alcohol (Parrott 2006; Von Huben et al. 2007; Walubo and Seger 1999). This combination is probably the main reason why it is generally seen an increase in toxicity events at rave parties since all these factors are thought to induce or enhance the toxicity (particularly the hyperthermic response) of MDMA. ... Another report showed that MDMA users displayed multiple regions of grey matter reduction in the neocortical, bilateral cerebellum, and midline brainstem brain regions, potentially accounting for previously reported neuropsychiatric impairments in MDMA users (Cowan et al. 2003). Neuroimaging techniques, like PET, were used in combination with a 5-HTT ligand in human ecstasy users, showing lower density of brain 5-HTT sites (McCann et al. 1998, 2005, 2008). Other authors correlate the 5-HTT reductions with the memory deficits seen in humans with a history of recreational MDMA use (McCann et al. 2008). A recent study prospectively assessed the sustained effects of ecstasy use on the brain in novel MDMA users using repeated measurements with a combination of different neuroimaging parameters of neurotoxicity. The authors concluded that low MDMA dosages can produce sustained effects on brain microvasculature, white matter maturation, and possibly axonal damage (de Win et al. 2008).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reynolds, Simon (1999). Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 0415923735.

- ^ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. May 2000.[dead link]

- ^ Liechti ME, Gamma A, Vollenweider FX (2001). "Gender Differences in the Subjective Effects of MDMA". Psychopharmacology. 154 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1007/s002130000648. PMID 11314678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Greene SL, Kerr F, Braitberg G (October 2008). "Review article: amphetamines and related drugs of abuse". Emerg. Med. Australas. 20 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x. PMID 18973636.

Clinical manifestation ...

hypertension, aortic dissection, arrhythmias, vasospasm, acute coronary syndrome, hypotension ... Agitation, paranoia, euphoria, hallucinations, bruxism, hyperreflexia, intracerebral haemorrhage ... pulmonary oedema/ARDS ... Hepatitis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, gastrointestinal ischaemia ... Hyponatraemia (dilutional/SIADH), acidosis ... Muscle rigidity, rhabdomyolysis

Desired effects

[entactogen] – euphoria, inner peace, social facilitation, 'heightens sexuality and expands consciousness', mild hallucinogenic effects ...

Clinical associations

Bruxism, hyperthermia, ataxia, confusion, hyponatraemia (SIADH), hepatitis, muscular rigidity, rhabdomyolysis, DIC, renal failure, hypotension, serotonin syndrome, chronic mood/memory disturbances ... human data have shown that long-term exposure to MDMA is toxic to serotonergic neurones.75,76{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Keane M (February 2014). "Recognising and managing acute hyponatraemia". Emerg Nurse. 21 (9): 32–6, quiz 37. doi:10.7748/en2014.02.21.9.32.e1128. PMID 24494770.

- ^ a b c d e f Michael White C (March 2014). "How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms". J Clin Pharmacol. 54 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1002/jcph.266. PMID 24431106.

Hyponatremia can occur from free water uptake in the collecting tubules secondary to the ADH effects and from over consumption of water to prevent dehydration and overheating. ... Hyperpyrexia resulting in rhabdomyolysis or heat stroke has occurred due to serotonin syndrome or enhanced physical activity without recognizing clinical clues of overexertion, warm temperatures in the clubs, and dehydration.1,4,9 ... Hepatic injury can also occur secondary to hyperpyrexia with centrilobular necrosis and microvascular steatosis.

- ^ "The Agony of Ecstasy: MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) and the Kidney".

- ^ "Polydipsia as another mechanism of hyponatremia after 'ecstasy' (3,4 methyldioxymethamphetamine) ingestion".

- ^ Spauwen, L. W. L.; Niekamp, A.-M.; Hoebe, C. J. P. A.; Dukers-Muijrers, N. H. T. M. (23 October 2014). "Drug use, sexual risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infections among swingers: a cross-sectional study in The Netherlands". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 91 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051626.

It is known that some recreational drugs (eg, MDMA or GHB) may hamper the potential to ejaculate or maintain an erection.

- ^ a b c d de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J (2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Therapeutic drug monitoring. 26 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

It is known that some recreational drugs (e.g., MDMA or GHB) may hamper the potential to ejaculate or maintain an erection.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 35 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i "3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

Over the course of a week following moderate use of the drug, many MDMA users report feeling a range of emotions, including anxiety, restlessness, irritability, and sadness that in some individuals can be as severe as true clinical depression. Similarly, elevated anxiety, impulsiveness, and aggression, as well as sleep disturbances, lack of appetite, and reduced interest in and pleasure from sex have been observed in regular MDMA users.

- ^ a b Halpin LE, Collins SA, Yamamoto BK (February 2014). "Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine". Life Sci. 97 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.014. PMID 23892199.

In contrast, MDMA produces damage to serotonergic, but not dopaminergic axon terminals in the striatum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Battaglia et al., 1987, O'Hearn et al., 1988). The damage associated with Meth and MDMA has been shown to persist for at least 2 years in rodents, non-human primates and humans (Seiden et al., 1988, Woolverton et al., 1989, McCann et al., 1998, Volkow et al., 2001a, McCann et al., 2005)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boyle NT, Connor TJ (September 2010). "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine ('Ecstasy')-induced immunosuppression: a cause for concern?" (PDF). British Journal of Pharmacology. 161 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00722.x. PMC 2962814. PMID 20718737.

- ^ Singer LT, Moore DG, Fulton S, Goodwin J, Turner JJ, Min MO, Parrott AC (2012). "Neurobehavioral outcomes of infants exposed to MDMA (Ecstasy) and other recreational drugs during pregnancy". Neurotoxicol Teratol. 34 (3): 303–10. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2012.02.001. PMC 3367027. PMID 22387807.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verheyden SL, Henry JA, Curran HV (2003). "Acute, sub-acute and long-term subjective consequences of 'ecstasy' (MDMA) consumption in 430 regular users". Hum Psychopharmacol. 18 (7): 507–17. doi:10.1002/hup.529. PMID 14533132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verheyden SL, Maidment R, Curran HV (2003). "Quitting ecstasy: an investigation of why people stop taking the drug and their subsequent mental health". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 17 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1177/0269881103174014. PMID 14870948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laws KR, Kokkalis J (2007). "Ecstasy (MDMA) and memory function: a meta-analytic update". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 22 (6): 381–88. doi:10.1002/hup.857. PMID 17621368.

- ^ Rodgers J, Buchanan T, Scholey AB, Heffernan TM, Ling J, Parrott AC (2003). "Patterns of drug use and the influence of gender on self-reports of memory ability in ecstasy users: a web-based study". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 17 (4): 389–96. doi:10.1177/0269881103174016. PMID 14870950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f John; Gunn, Scott; Singer, Mervyn; Webb, Andrew Kellum. Oxford American Handbook of Critical Care. Oxford University Press (2007). ASIN: B002BJ4V1C. Page 464.

- ^ de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J (2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Ther Drug Monit. 26 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chummun H, Tilley V, Ibe J (2010). "3,4-methylenedioxyamfetamine (ecstasy) use reduces cognition". Br J Nurs. 19 (2): 94–100. PMID 20235382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/wrenthal. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN (2015). "Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (2): 696–717 (Figure 1). doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8. PMC 4359351. PMID 24939695.

- ^ a b c Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ a b c Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- ^ Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: Role of ΔFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–3255. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

- ^ a b Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Tronson N, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR (September 2006). "DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens regulates food-reinforced instrumental behavior and motivation". J. Neurosci. 26 (36): 9196–204. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-06.2006. PMID 16957076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ Silins E, Copeland J, Dillon P (2007). "Qualitative review of serotonin syndrome, ecstasy (MDMA) and the use of other serotonergic substances: Hierarchy of risk". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 41 (8): 649–655. doi:10.1080/00048670701449237. PMID 17620161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vuori E, Henry JA, Ojanperä I, Nieminen R, Savolainen T, Wahlsten P, Jäntti M (2003). "Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide". Addiction. 98 (3): 365–8. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00292.x. PMID 12603236.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMID 21272013.

- ^ Fitzgerald JL, Reid JJ (1990). "Effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine on the release of monoamines from rat brain slices". European Journal of Pharmacology. 191 (2): 217–20. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(90)94150-V. PMID 1982265.

- ^ Bogen IL, Haug KH, Myhre O, Fonnum F (2003). "Short- and long-term effects of MDMA ("ecstasy") on synaptosomal and vesicular uptake of neurotransmitters in vitro and ex vivo". Neurochemistry International. 43 (4–5): 393–400. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00027-5. PMID 12742084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Battaglia G, Brooks BP, Kulsakdinun C, De Souza EB (1988). "Pharmacologic profile of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) at various brain recognition sites". European Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (1–2): 159–63. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(88)90056-8. PMID 2899513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lyon RA, Glennon RA, Titeler M (1986). "3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): stereoselective interactions at brain 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors". Psychopharmacology. 88 (4): 525–6. doi:10.1007/BF00178519. PMID 2871581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nash JF, Roth BL, Brodkin JD, Nichols DE, Gudelsky GA (1994). "Effect of the R(-) and S(+) isomers of MDA and MDMA on phosphatidyl inositol turnover in cultured cells expressing 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C receptors". Neuroscience Letters. 177 (1–2): 111–5. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90057-4. PMID 7824160.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Setola V, Hufeisen SJ, Grande-Allen KJ, Vesely I, Glennon RA, Blough B, Rothman RB, Roth BL (2003). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") induces fenfluramine-like proliferative actions on human cardiac valvular interstitial cells in vitro". Molecular Pharmacology. 63 (6): 1223–9. doi:10.1124/mol.63.6.1223. PMID 12761331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dumont GJ, Sweep FC, van der Steen R, Hermsen R, Donders AR, Touw DJ, van Gerven JM, Buitelaar JK, Verkes RJ (2009). "Increased oxytocin concentrations and prosocial feelings in humans after ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) administration" (PDF). Soc Neurosci. 4 (4): 359–366. doi:10.1080/17470910802649470. PMID 19562632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baumann MH, Rothman RB (6 November 2009). "NEURAL AND CARDIAC TOXICITIES ASSOCIATED WITH 3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE (MDMA)". International Review of Neurobiology. International Review of Neurobiology. 88 (1): 257–296. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(09)88010-0. ISBN 9780123745040. PMC 3153986. PMID 19897081.

- ^ Matsumoto RR (July 2009). "Targeting sigma receptors: novel medication development for drug abuse and addiction". Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2 (4): 351–8. doi:10.1586/ecp.09.18. PMC 3662539. PMID 22112179.

- ^ a b R. De La Torre, M. Farré, J. Ortuño, M. Mas, R. Brenneisen, P. N. Roset, ; et al. (February 2000). "Non-linear pharmacokinetics of MDMA ('ecstasy') in humans". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 49 (2): 104–109. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00121.x.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. DE LA TORRE, M. FARRÉ, P. N. ROSET, C. HERNÁNDEZ LÓPEZ, M. MAS, J. ORTUÑO; et al. (September 2000). "Pharmacology of MDMA in humans". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 914 (1): 225–237. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05199.x.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verebey K, Alrazi J, Jaffe JH (1988). "The complications of 'ecstasy' (MDMA)". JAMA. 259 (11): 1649–1650. doi:10.1001/jama.259.11.1649. PMID 2893845.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kolbrich, Erin A; Goodwin, Robert S; Gorelick, David A; Hayes, Robert J; Stein, Elliot A; Huestis, Marilyn A (June 2008). "Plasma Pharmacokinetics of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine After Controlled Oral Administration to Young Adults". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 30 (3): 320–332. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181684fa0.

- ^ Shima N, Kamata H, Katagi M, Tsuchihashi H, Sakuma T, Nemoto N (2007). "Direct Determination of Glucuronide and Sulfate of 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxymethamphetamine, the Main Metabolite of MDMA, in Human Urine". J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 857 (1): 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.07.003. PMID 17643356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fallon JK, Kicman AT, Henry JA, Milligan PJ, Cowan DA, Hutt AJ (1 July 1999). "Stereospecific Analysis and Enantiomeric Disposition of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy) in Humans". Clinical Chemistry. 45 (7): 1058–1069. PMID 10388483.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mueller M, Peters FT, Maurer HH, McCann UD, Ricaurte GA (October 2008). "Nonlinear Pharmacokinetics of (±)3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") and Its Major Metabolites in Squirrel Monkeys at Plasma Concentrations of MDMA That Develop After Typical Psychoactive Doses". JPET. 327 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.141366. PMID 18591215.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Milhazes N, Martins P, Uriarte E, Garrido J, Calheiros R, Marques MP, Borges F (2007). "Electrochemical and spectroscopic characterisation of amphetamine-like drugs: application to the screening of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and its synthetic precursors". Anal. Chim. Acta. 596 (2): 231–41. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2007.06.027. PMID 17631101.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Milhazes N, Cunha-Oliveira T, Martins P, Garrido J, Oliveira C, Rego AC, Borges F (2006). "Synthesis and cytotoxic profile of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy") and its metabolites on undifferentiated PC12 cells: A putative structure-toxicity relationship". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19 (10): 1294–304. doi:10.1021/tx060123i. PMID 17040098.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reductive aminations of carbonyl compounds with borohydride and borane reducing agents. Baxter, Ellen W.; Reitz, Allen B. Organic Reactions (Hoboken, New Jersey, United States) (2002), 59.

- ^ Gimeno P, Besacier F, Bottex M, Dujourdy L, Chaudron-Thozet H (2005). "A study of impurities in intermediates and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) samples produced via reductive amination routes". Forensic Sci. Int. 155 (2–3): 141–57. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.11.013. PMID 16226151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palhol, Fabien; Boyer, Sophie; Naulet, Norbert; Chabrillat, Martine (28 August 2002). "Impurity profiling of seized MDMA tablets by capillary gas chromatography". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 374 (2): 274–281. doi:10.1007/s00216-002-1477-6.

- ^ Renton, RJ; Cowie, JS; Oon, MC (August 1993). "A study of the precursors, intermediates and reaction by-products in the synthesis of 3,4-methylenedioxymethylamphetamine and its application to forensic drug analysis". Forensic Sci. Int. 60 (3): 189–202. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(93)90238-6. PMID 7901132.

- ^ Nov 2005 DEA Microgram newsletter, p. 166. Usdoj.gov (11 November 2005). Retrieved on 12 August 2013.

- ^ Kolbrich EA, Goodwin RS, Gorelick DA, Hayes RJ, Stein EA, Huestis MA. Plasma pharmacokinetics of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine after controlled oral administration to young adults. Ther. Drug Monit. 30: 320–332, 2008.

- ^ Barnes AJ, De Martinis BS, Gorelick DA, Goodwin RS, Kolbrich EA, Huestis MA (2009). "Disposition of MDMA and metabolites in human sweat following controlled MDMA administration" (PDF). Clinical chemistry. 55 (3): 454–62. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.117093. PMC 2669283. PMID 19168553.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, California, 2011, pp. 1078–1080.

- ^ a b c Bernschneider-Reif S, Oxler F, Freudenmann RW (2006). "The origin of MDMA ('Ecstasy') – separating the facts from the myth". Pharmazie. 61 (11): 966–972. doi:10.5555/phmz.61.11.966. PMID 17152992.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Firma E. Merck in Darmstadt (16 May 1914). "German Patent 274350: Verfahren zur Darstellung von Alkyloxyaryl-, Dialkyloxyaryl- und Alkylendioxyarylaminopropanen bzw. deren am Stickstoff monoalkylierten Derivaten". Kaiserliches Patentamt. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ Firma E. Merck in Darmstadt (15 October 1914). "German Patent 279194: Verfahren zur Darstellung von Hydrastinin Derivaten". Kaiserliches Patentamt.

- ^ Hardman HF, Haavik CO, Seevers MH (1973). "Relationship of the Structure of Mescaline and Seven Analogs to Toxicity and Behavior in Five Species of Laboratory Animals". Toxicology Applied Pharmacology. 25 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1016/S0041-008X(73)80016-X. PMID 4197635.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Benzenhöfer, Udo; Passie, Torsten (9 July 2010). "Rediscovering MDMA (ecstasy): the role of the American chemist Alexander T. Shulgin". Addiction. 105 (8): 1355–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02948.x.

- ^ The first confirmed sample was seized and identified by Chicago Police in 1970, see Sreenivasan VR (1972). "Problems in Identification of Methylenedioxy and Methoxy Amphetamines". Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology & Police Science. 63 (2). The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, Vol. 63, No. 2: 304–312. doi:10.2307/1142315. JSTOR 1142315.

- ^ a b c Brown, Ethan (September 2002). "Professor X". http://archive.wired.com. Wired. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Alexander 'Sasha' Shulgin". http://shulginresearch.org. Alexander Shulgin Research Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Shulgin AT; Nichols DE (1978). "Characterization of Three New Psychotomimetics". In Willette, Robert E.; Stillman, Richard Joseph (ed.). The Psychopharmacology of Hallucinogens. New York: Pergamon Press. pp. 74–83. ISBN 0-08-021938-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Jennings, Peter (1 April 2004). "Ecstasy Rising". Primetime Thursday. No. Special edition. ABC News.

- ^ Shulgin, Alexander; Shulgin, Ann (1991). "Part I, Chapter 12". PiHKAL : A Chemical Love Story (7th printing, 1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: Transform Press. ISBN 0963009605.

- ^ Bennett, Drake (30 January 2005). "Dr. Ecstasy". New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Shulgin, Ann (2004). "Tribute to Jacob". In Doblin, Rick (ed.). The Secret Chief Revealed (PDF) (2nd ed.). Sarasota, Fl: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-9660019-6-6. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Eisner, Bruce (1994). Ecstasy : The MDMA Story (Expanded 2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Ronin Publishing. ISBN 0914171682.

- ^ a b c d Doblin, Rick; Rosenbaum, Marsha (1991). "Chapter 6: Why MDMA Should Not Have Been Made Illegal". In Inciardi, James A. (ed.). The Drug Legalization Debate (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN 0803936788. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Collin, Matthew; Godfrey, John (2010). "The Technologies of Pleasure". Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House (Updated new ed.). London: Profile Books. ISBN 9781847656414.

- ^ a b c d e f Pentney AR (2001). "An exploration of the history and controversies surrounding MDMA and MDA". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 33 (3): 213–21. doi:10.1080/02791072.2001.10400568. PMID 11718314.

- ^ Power, Mike (2013). "2: The Great Ecstasy of Toolmaker Shulgin". Drugs 2.0 : the web revolution that's changing how the world gets high. London: Portobello. p. 50. ISBN 9781846274596.

- ^ "Schedules of Controlled Substances Proposed Placement of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine in Schedule I" (PDF). Federal Register. 49 (146): 30210. 27 July 1984. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ Adler, Jerry; Abramson, Pamela; Katz, Susan; Hager, Mary (15 April 1985). "Getting High on 'Ecstasy'" (PDF). Newsweek. Life/Style: Newsweek Magazine. p. 96. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "U.S. WILL BAN 'ECSTASY,' A HALLUCINOGENIC DRUG". The New York Times. 1 June 1985. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ 22nd report of the Expert Committee on Drug Dependence World Health Organization, 1985. (PDF) . Retrieved on 29 August 2012.

- ^ McKinley, Jr., James C. (12 September 2013). "Overdoses of 'Molly' Led to Electric Zoo Deaths". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Bibliography of Psychedelic Research Studies. collected by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies [dead link]

- ^ Susan Donaldson James (23 February 2015). "What Is Molly and Why Is It Dangerous?". NBCNews.com. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

Why is it called Molly? That's short for "molecule." "You can put a ribbon and bow on it and call it a cute name like 'Molly' and people are all in," said Paul Doering, professor emeritus of pharmacology at the University of Florida.

- ^ Aleksander, Irina (21 June 2013). "Molly: Pure, but Not So Simple". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Mephedrone (4-Methylmethcathinone) appearing in "Ecstasy" in the Netherlands". 19 September 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Why ecstasy is 'vanishing' from UK nightclubs". BBC News. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Statutelaw.gov.uk (5 January 1998). Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

- ^ Schedules of Controlled Substances; Scheduling of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Into Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act; Remand, 53 Fed. Reg. 5,156 (DEA 22 February 1988).

- ^ Court Rejects Harsh Federal Drug Sentencing Guideline as Scientifically Unjustified | American Civil Liberties Union. Aclu.org (15 July 2011). Retrieved on 29 August 2012.

- ^ a b "An Examination of Federal Sentencing Guidelines' Treatment of MDMA ('Ecstasy') by Alyssa C. Hennig :: SSRN".

- ^ Rapport Drugs in Lijsten | Rapport. Rijksoverheid.nl (27 June 2011). Retrieved on 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Committee: the current system of the Opium Act does not have to be changed". government.nl. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

As regards MDMA, better known as XTC, the committee concludes that investigations show that damage to the health of the individual in the long term is less serious than was initially assumed. But the extent of the illegal production and involvement of organised crime leads to damage to society, including damage to the image of the Netherlands abroad. This argues in favour of maintaining MDMA on List I.

- ^ "Schedule I". Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Isomer Design. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "Definitions and interpretations". Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Isomer Design. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 49. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6.

- ^ European Drug Report 2014, page 26

- ^ "Ecstasy-type substances Retail and wholesale prices* and purity levels, by drug, region and country or territory". http://www.unodc.org/wdr2014/. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Camargo J, Esseiva P, González F, Wist J, Patiny L (30 November 2012). "Monitoring of illicit pill distribution networks using an image collection exploration framework". Forensic Science International. 223 (1): 298–305. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.10.004. PMID 23107059. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Drugtext – 10 years of ecstasy and other party drug use in Australia: What have we done and what is there left to do?. Drugtext.org. Retrieved on 11 June 2011. [dead link]

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17382831, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17382831instead. - ^ Scientists want new drug rankings, BBC News (23 March 2007).

- ^ Nutt, David J; King, Leslie A; Phillips, Lawrence D (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". The Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Zarembo, Alan (15 March 2014). "Exploring therapeutic effects of MDMA on post-traumatic stress". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Danforth, Alicia L.; Struble, Christopher M.; Yazar-Klosinski, Berra; Grob, Charles S. (March 2015). "MDMA-assisted therapy: A new treatment model for social anxiety in autistic adults". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.03.011. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ (Text color) Transcription factors