Immigration to the United States: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Citation needed}} |

m →Crime: absolute crime can't be known, only crime which is reported. |

||

| Line 986: | Line 986: | ||

Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partly explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal|last=Wadsworth|first=Tim|date=June 1, 2010|title=Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop? An Assessment of the Influence of Immigration on Changes in Violent Crime Between 1990 and 2000|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x/abstract|journal=Social Science Quarterly|volume=91|issue=2|pages=531–53|doi=10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x|issn=1540-6237|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906003850/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x/abstract|archivedate=September 6, 2015|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stowell|first=Jacob I.|last2=Messner|first2=Steven F.|last3=Mcgeever|first3=Kelly F.|last4=Raffalovich|first4=Lawrence E.|date=August 1, 2009|title=Immigration and the Recent Violent Crime Drop in the United States: A Pooled, Cross-Sectional Time-Series Analysis of Metropolitan Areas|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x/abstract|journal=Criminology|language=en|volume=47|issue=3|pages=889–928|doi=10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x|issn=1745-9125|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160316090136/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x/abstract|archivedate=March 16, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sampson |first=Robert J. |date=2008-02-01 |title=Rethinking Crime and Immigration |url=https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2008.7.1.28 |journal=Contexts |language=en |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=28–33 |doi=10.1525/ctx.2008.7.1.28 |issn=1536-5042}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ferraro|first=Vincent|date=February 14, 2015|title=Immigration and Crime in the New Destinations, 2000–2007: A Test of the Disorganizing Effect of Migration|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y|journal=Journal of Quantitative Criminology|language=en|volume=32|issue=1|pages=23–45|doi=10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y|issn=0748-4518}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|date=August 2014|title=Safer Cities: A Macro-level analysis of Recent Immigration, Hispanic-owned Businesses, and Crime Rates in the United States|journal=Journal of Urban Affairs|volume=36|issue=3|pages=503–18|doi=10.1111/juaf.12051|last1=Stansfield |first1=Richard}}</ref> A 2005 study showed that immigration to large U.S. metropolitan areas does not increase, and in some cases decreases, crime rates there.<ref>{{cite journal|last2=Weiss|first2=Harald E.|last3=Adelman|first3=Robert M.|last4=Jaret|first4=Charles|date=December 2005|title=The immigration–crime relationship: Evidence across US metropolitan areas|journal=Social Science Research|volume=34|issue=4|pages=757–80|doi=10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.01.001|last1=Reid|first1=Lesley Williams}}</ref> A 2009 study found that recent immigration was not associated with homicide in [[Austin, Texas]].<ref>{{cite journal|last2=Rumbaut|first2=R. G.|last3=Stansfield|first3=R.|date=June 10, 2009|title=Immigration, Economic Disadvantage, and Homicide: A Community-level Analysis of Austin, Texas|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=13|issue=3|pages=307–14|doi=10.1177/1088767909336814|last1=Akins|first1=S.}}</ref> The low crime rates of immigrants to the United States despite having lower levels of education, lower levels of income and residing in urban areas (factors that should lead to higher crime rates) may be due to lower rates of antisocial behavior among immigrants.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Vaughn|first=Michael G.|last2=Salas-Wright|first2=Christopher P.|last3=DeLisi|first3=Matt|last4=Maynard|first4=Brandy R.|date=November 29, 2013|title=The immigrant paradox: immigrants are less antisocial than native-born Americans|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00127-013-0799-3|journal=Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology|language=en|volume=49|issue=7|pages=1129–37|doi=10.1007/s00127-013-0799-3|issn=0933-7954|pmc=4078741|pmid=24292669}}</ref> A 2015 study found that Mexican immigration to the United States was associated with an increase in aggravated assaults and a decrease in property crimes.<ref>{{cite journal|date=May 2015|title=The Long-Run Effect of Mexican Immigration on Crime in US Cities: Evidence from Variation in Mexican Fertility Rates|journal=American Economic Review|volume=105|issue=5|pages=220–25|doi=10.1257/aer.p20151043|last1=Chalfin|first1=Aaron}}</ref> A 2016 study finds no link between immigrant populations and violent crime, although there is a small but significant association between undocumented immigrants and drug-related crime.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Green|first=David|date=May 1, 2016|title=The Trump Hypothesis: Testing Immigrant Populations as a Determinant of Violent and Drug-Related Crime in the United States|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.12300/abstract|journal=Social Science Quarterly|language=en|pages=n/a–n/a|doi=10.1111/ssqu.12300|issn=1540-6237|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604062341/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.12300/abstract|archivedate=June 4, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partly explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal|last=Wadsworth|first=Tim|date=June 1, 2010|title=Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop? An Assessment of the Influence of Immigration on Changes in Violent Crime Between 1990 and 2000|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x/abstract|journal=Social Science Quarterly|volume=91|issue=2|pages=531–53|doi=10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x|issn=1540-6237|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906003850/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x/abstract|archivedate=September 6, 2015|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stowell|first=Jacob I.|last2=Messner|first2=Steven F.|last3=Mcgeever|first3=Kelly F.|last4=Raffalovich|first4=Lawrence E.|date=August 1, 2009|title=Immigration and the Recent Violent Crime Drop in the United States: A Pooled, Cross-Sectional Time-Series Analysis of Metropolitan Areas|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x/abstract|journal=Criminology|language=en|volume=47|issue=3|pages=889–928|doi=10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x|issn=1745-9125|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160316090136/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00162.x/abstract|archivedate=March 16, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sampson |first=Robert J. |date=2008-02-01 |title=Rethinking Crime and Immigration |url=https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2008.7.1.28 |journal=Contexts |language=en |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=28–33 |doi=10.1525/ctx.2008.7.1.28 |issn=1536-5042}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ferraro|first=Vincent|date=February 14, 2015|title=Immigration and Crime in the New Destinations, 2000–2007: A Test of the Disorganizing Effect of Migration|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y|journal=Journal of Quantitative Criminology|language=en|volume=32|issue=1|pages=23–45|doi=10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y|issn=0748-4518}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|date=August 2014|title=Safer Cities: A Macro-level analysis of Recent Immigration, Hispanic-owned Businesses, and Crime Rates in the United States|journal=Journal of Urban Affairs|volume=36|issue=3|pages=503–18|doi=10.1111/juaf.12051|last1=Stansfield |first1=Richard}}</ref> A 2005 study showed that immigration to large U.S. metropolitan areas does not increase, and in some cases decreases, crime rates there.<ref>{{cite journal|last2=Weiss|first2=Harald E.|last3=Adelman|first3=Robert M.|last4=Jaret|first4=Charles|date=December 2005|title=The immigration–crime relationship: Evidence across US metropolitan areas|journal=Social Science Research|volume=34|issue=4|pages=757–80|doi=10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.01.001|last1=Reid|first1=Lesley Williams}}</ref> A 2009 study found that recent immigration was not associated with homicide in [[Austin, Texas]].<ref>{{cite journal|last2=Rumbaut|first2=R. G.|last3=Stansfield|first3=R.|date=June 10, 2009|title=Immigration, Economic Disadvantage, and Homicide: A Community-level Analysis of Austin, Texas|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=13|issue=3|pages=307–14|doi=10.1177/1088767909336814|last1=Akins|first1=S.}}</ref> The low crime rates of immigrants to the United States despite having lower levels of education, lower levels of income and residing in urban areas (factors that should lead to higher crime rates) may be due to lower rates of antisocial behavior among immigrants.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Vaughn|first=Michael G.|last2=Salas-Wright|first2=Christopher P.|last3=DeLisi|first3=Matt|last4=Maynard|first4=Brandy R.|date=November 29, 2013|title=The immigrant paradox: immigrants are less antisocial than native-born Americans|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00127-013-0799-3|journal=Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology|language=en|volume=49|issue=7|pages=1129–37|doi=10.1007/s00127-013-0799-3|issn=0933-7954|pmc=4078741|pmid=24292669}}</ref> A 2015 study found that Mexican immigration to the United States was associated with an increase in aggravated assaults and a decrease in property crimes.<ref>{{cite journal|date=May 2015|title=The Long-Run Effect of Mexican Immigration on Crime in US Cities: Evidence from Variation in Mexican Fertility Rates|journal=American Economic Review|volume=105|issue=5|pages=220–25|doi=10.1257/aer.p20151043|last1=Chalfin|first1=Aaron}}</ref> A 2016 study finds no link between immigrant populations and violent crime, although there is a small but significant association between undocumented immigrants and drug-related crime.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Green|first=David|date=May 1, 2016|title=The Trump Hypothesis: Testing Immigrant Populations as a Determinant of Violent and Drug-Related Crime in the United States|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.12300/abstract|journal=Social Science Quarterly|language=en|pages=n/a–n/a|doi=10.1111/ssqu.12300|issn=1540-6237|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604062341/http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.12300/abstract|archivedate=June 4, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

||

Research finds that [[Secure Communities and administrative immigration policies|Secure Communities]], an immigration enforcement program which led to a quarter of a million of detentions (when the study was published; November 2014), had no observable impact on the crime rate.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Miles|first=Thomas J.|last2=Cox|first2=Adam B.|date=October 21, 2015|title=Does Immigration Enforcement Reduce Crime? Evidence from Secure Communities|url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/680935|journal=The Journal of Law and Economics|volume=57|issue=4|pages=937–973|doi=10.1086/680935}}</ref> A 2015 study found that the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which legalized almost 3 million immigrants, led to "decreases in crime of 3–5 percent, primarily due to decline in property crimes, equivalent to 120,000-180,000 fewer violent and property crimes committed each year due to legalization".<ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last=Baker|first=Scott R.|title=Effects of Immigrant Legalization on Crime †|url=http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/aer.p20151041|journal=American Economic Review|volume=105|issue=5|pages=210–13|doi=10.1257/aer.p20151041}}</ref> According to one study, [[Sanctuary city|sanctuary cities]]—which adopt policies designed to not prosecute people solely for being an illegal |

Research finds that [[Secure Communities and administrative immigration policies|Secure Communities]], an immigration enforcement program which led to a quarter of a million of detentions (when the study was published; November 2014), had no observable impact on the crime rate.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Miles|first=Thomas J.|last2=Cox|first2=Adam B.|date=October 21, 2015|title=Does Immigration Enforcement Reduce Crime? Evidence from Secure Communities|url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/680935|journal=The Journal of Law and Economics|volume=57|issue=4|pages=937–973|doi=10.1086/680935}}</ref> A 2015 study found that the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which legalized almost 3 million immigrants, led to "decreases in crime of 3–5 percent, primarily due to decline in property crimes, equivalent to 120,000-180,000 fewer violent and property crimes committed each year due to legalization".<ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last=Baker|first=Scott R.|title=Effects of Immigrant Legalization on Crime †|url=http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/aer.p20151041|journal=American Economic Review|volume=105|issue=5|pages=210–13|doi=10.1257/aer.p20151041}}</ref> According to one study, [[Sanctuary city|sanctuary cities]]—which adopt policies designed to not prosecute people solely for being an illegal immigrant—have no statistically meaningful effect on reported crime.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/03/sanctuary-cities-do-not-experience-an-increase-in-crime/|title=Sanctuary cities do not experience an increase in crime|website=Washington Post|access-date=October 3, 2016|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161003200516/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/03/sanctuary-cities-do-not-experience-an-increase-in-crime/|archivedate=October 3, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

||

One of the first political analyses in the U.S. of the relationship between immigration and crime was performed in the beginning of the 20th century by the [[Dillingham Commission]], which found a relationship especially for immigrants from non-Northern European countries, resulting in the sweeping 1920s [[immigration reduction]] acts, including the [[Emergency Quota Act]] of 1921, which favored immigration from [[Northern Europe|northern]] and [[western Europe]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/dillingham.html|title=Open Collections Program: Immigration to the US, Dillingham Commission (1907-1910)|publisher=|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130125123555/http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/dillingham.html|archivedate=January 25, 2013|df=mdy-all}}</ref> Recent research is skeptical of the conclusion drawn by the Dillingham Commission. One study finds that "major government commissions on immigration and crime in the early twentieth century relied on evidence that suffered from aggregation bias and the absence of accurate population data, which led them to present partial and sometimes misleading views of the immigrant-native criminality comparison. With improved data and methods, we find that in 1904, prison commitment rates for more serious crimes were quite similar by nativity for all ages except ages 18 and 19, for which the commitment rate for immigrants was higher than for the native-born. By 1930, immigrants were less likely than natives to be committed to prisons at all ages 20 and older, but this advantage disappears when one looks at commitments for violent offenses."<ref name=":28">{{Cite journal|last=Moehling|first=Carolyn|last2=Piehl|first2=Anne Morrison|date=November 1, 2009|title=Immigration, crime, and incarceration in early twentieth-century america|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1353/dem.0.0076|journal=Demography|volume=46|issue=4|pages=739–63|doi=10.1353/dem.0.0076|issn=0070-3370}}</ref> |

One of the first political analyses in the U.S. of the relationship between immigration and crime was performed in the beginning of the 20th century by the [[Dillingham Commission]], which found a relationship especially for immigrants from non-Northern European countries, resulting in the sweeping 1920s [[immigration reduction]] acts, including the [[Emergency Quota Act]] of 1921, which favored immigration from [[Northern Europe|northern]] and [[western Europe]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/dillingham.html|title=Open Collections Program: Immigration to the US, Dillingham Commission (1907-1910)|publisher=|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130125123555/http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/dillingham.html|archivedate=January 25, 2013|df=mdy-all}}</ref> Recent research is skeptical of the conclusion drawn by the Dillingham Commission. One study finds that "major government commissions on immigration and crime in the early twentieth century relied on evidence that suffered from aggregation bias and the absence of accurate population data, which led them to present partial and sometimes misleading views of the immigrant-native criminality comparison. With improved data and methods, we find that in 1904, prison commitment rates for more serious crimes were quite similar by nativity for all ages except ages 18 and 19, for which the commitment rate for immigrants was higher than for the native-born. By 1930, immigrants were less likely than natives to be committed to prisons at all ages 20 and older, but this advantage disappears when one looks at commitments for violent offenses."<ref name=":28">{{Cite journal|last=Moehling|first=Carolyn|last2=Piehl|first2=Anne Morrison|date=November 1, 2009|title=Immigration, crime, and incarceration in early twentieth-century america|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1353/dem.0.0076|journal=Demography|volume=46|issue=4|pages=739–63|doi=10.1353/dem.0.0076|issn=0070-3370}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:45, 20 September 2017

Immigration to the United States is the international movement of individuals who are not natives or do not possess citizenship in order to settle, reside, study or to take-up employment in the United States. It has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of the United States. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants, settlement patterns, impact on upward social mobility, crime, and voting behavior.

Prior to 1965, policies such as the national origins formula limited immigration and naturalization opportunities for people from areas outside Western Europe. Exclusion laws enacted as early as the 1880s generally prohibited or severely restricted immigration from Asia, and quota laws enacted in the 1920s curtailed Eastern European immigration. The Civil Rights Movement led to the replacement[1] of these ethnic quotas with per-country limits.[2] Since then, the number of first-generation immigrants living in the United States has quadrupled.[3][4]

Research suggests that immigration to the United States is beneficial to the US economy. With few exceptions, the evidence suggests that immigration on average has positive economic effects on the native population, but is mixed as to whether low-skilled immigration adversely affects low-skilled natives. Studies also indicate that immigration either has no impact on the crime rate or that it reduces the crime rate in the United States.[5][6] Research shows that the United States excels at assimilating first- and second-generation immigrants relative to many other Western countries.

History

American immigration history can be viewed in four epochs: the colonial period, the mid-19th century, the start of the 20th century, and post-1965. Each period brought distinct national groups, races and ethnicities to the United States. During the 17th century, approximately 400,000 English people migrated to Colonial America.[7] Over half of all European immigrants to Colonial America during the 17th and 18th centuries arrived as indentured servants.[8] The mid-19th century saw mainly an influx from northern Europe; the early 20th-century mainly from Southern and Eastern Europe; post-1965 mostly from Latin America and Asia.

Historians estimate that fewer than 1 million immigrants came to the United States from Europe between 1600 and 1799.[9] The 1790 Act limited naturalization to "free white persons"; it was expanded to include blacks in the 1860s and Asians in the 1950s.[10] In the early years of the United States, immigration was fewer than 8,000 people a year,[11] including French refugees from the slave revolt in Haiti. After 1820, immigration gradually increased. From 1836 to 1914, over 30 million Europeans migrated to the United States.[12] The death rate on these transatlantic voyages was high, during which one in seven travelers died.[13] In 1875, the nation passed its first immigration law, the Page Act of 1875.[14]

After an initial wave of immigration from China following the California Gold Rush, Congress passed a series of laws culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, banning virtually all immigration from China until the law's repeal in 1943. In the late 1800s, immigration from other Asian countries, especially to the West Coast, became more common.

The peak year of European immigration was in 1907, when 1,285,349 persons entered the country.[15] By 1910, 13.5 million immigrants were living in the United States.[16] In 1921, the Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The 1924 Act was aimed at further restricting immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, particularly Jews, Italians, and Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s, and consolidated the prohibition of Asian immigration.[17]

Immigration patterns of the 1930s were dominated by the Great Depression. In the final prosperous year, 1929, there were 279,678 immigrants recorded,[18] but in 1933, only 23,068 came to the U.S.[9] In the early 1930s, more people emigrated from the United States than to it.[19] The U.S. government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands were deported against their will.[20] Altogether about 400,000 Mexicans were repatriated.[21] Most of the Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis and World War II were barred from coming to the United States.[22] In the post-war era, the Justice Department launched Operation Wetback, under which 1,075,168 Mexicans were deported in 1954.[23]

First, our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. Under the proposed bill, the present level of immigration remains substantially the same.... Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.... Contrary to the charges in some quarters, [the bill] will not inundate America with immigrants from any one country or area, or the most populated and deprived nations of Africa and Asia.... In the final analysis, the ethnic pattern of immigration under the proposed measure is not expected to change as sharply as the critics seem to think.

— Ted Kennedy, chief Senate sponsor of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[24]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Cellar Act, abolished the system of national-origin quotas. By equalizing immigration policies, the act resulted in new immigration from non-European nations, which changed the ethnic make-up of the United States.[25] In 1970, 60% of immigrants were from Europe; this decreased to 15% by 2000.[26] In 1990, George H. W. Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990,[27] which increased legal immigration to the United States by 40%.[28] In 1991, Bush signed the Armed Forces Immigration Adjustment Act 1991, allowing foreign service members who had serve 12 or more years in the US Armed Forces to qualify for permanent residency and, in some cases, citizenship.

In November 1994, California voters passed Proposition 187 amending the state constitution, denying state financial aid to illegal immigrants. The federal courts voided this change, ruling that it violated the federal constitution.[29]

Appointed by Bill Clinton,[30] the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform recommended reducing legal immigration from about 800,000 people per year to approximately 550,000.[31] While an influx of new residents from different cultures presents some challenges, "the United States has always been energized by its immigrant populations," said President Bill Clinton in 1998. "America has constantly drawn strength and spirit from wave after wave of immigrants [...] They have proved to be the most restless, the most adventurous, the most innovative, the most industrious of people."[32]

In 2001, President George W. Bush discussed an accord with Mexican President Vincente Fox. Possible accord was derailed by the September 11 attacks. From 2005 to 2013, the US Congress discussed various ways of controlling immigration. The Senate and House are unable to reach an agreement. In 2012 and 2014, President Obama initiated policies that were intended to ease the pressure on deporting people who use anchor babies as a means of immigrating to the United States.[29]

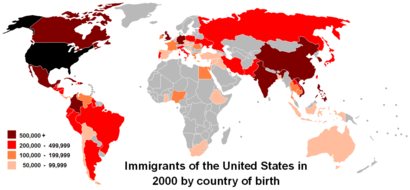

Nearly 14 million immigrants entered the United States from 2000 to 2010,[33] and over one million persons were naturalized as U.S. citizens in 2008. The per-country limit[2] applies the same maximum on the number of visas to all countries regardless of their population and has therefore had the effect of significantly restricting immigration of persons born in populous nations such as Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines—the leading countries of origin for legally admitted immigrants to the United States in 2013;[34] nevertheless, China, India, and Mexico were the leading countries of origin for immigrants overall to the United States in 2013, regardless of legal status, according to a U.S. Census Bureau study.[35] As of 2009[update], 66% of legal immigrants were admitted on the basis of family ties, along with 13% admitted for their employment skills and 17% for humanitarian reasons.[36]

Nearly 8 million people immigrated to the United States from 2000 to 2005; 3.7 million of them entered without papers.[37][38] In 1986 president Ronald Reagan signed immigration reform that gave amnesty to 3 million undocumented immigrants in the country.[39] Hispanic immigrants suffered job losses during the late-2000s recession,[40] but since the recession's end in June 2009, immigrants posted a net gain of 656,000 jobs.[41] Over 1 million immigrants were granted legal residence in 2011.[42]

For those who enter the US illegally across the Mexico–United States border and elsewhere, migration is difficult, expensive and dangerous.[43] Virtually all undocumented immigrants have no avenues for legal entry to the United States due to the restrictive legal limits on green cards, and lack of immigrant visas for low-skilled workers.[44] Participants in debates on immigration in the early twenty-first century called for increasing enforcement of existing laws governing illegal immigration to the United States, building a barrier along some or all of the 2,000-mile (3,200 km) Mexico-U.S. border, or creating a new guest worker program. Through much of 2006 the country and Congress was immersed in a debate about these proposals. As of April 2010[update] few of these proposals had become law, though a partial border fence had been approved and subsequently canceled.[45]

In January 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order temporarily suspending entry to the US from Yemen, Sudan, Somalia, Iraq, Iran, and Libya, and a suspension of entry from Syria for an indefinite period.[46][47] The order also limited the number of refugees permitted to enter the United States in 2017 to 50,000 and suspended the United States Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days to allow authorities to review the application and adjudication processes.[48] The order was replaced with a new executive order in March 2017 with various changes including removing Iraq from the list of countries with suspended immigration, clarifying that legal immigrants are exempt from the ban, and reducing the ban on Syrian immigrants to a 120-day suspension.[49] Another executive order called for the immediate construction of a wall across the U.S.–Mexico border, the hiring of 5,000 new border patrol agents and 10,000 new immigration officers, and federal funding penalties for Sanctuary Cities.[50]

On February 3, 2017, a federal judge in Washington State ordered a nationwide halt to the enforcement of Trump's executive action.[51] And on February 4, 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security suspended the rules that flagged travelers under the executive order.[52]

- Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status Fiscal Years[53]

| Year | Year | Year | Year | Year | Year | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 241,700 | 1950 | 249,187 | 1970 | 373,326 | 1990 | 1,535,872 | 2006 | 1,266,129 | 2010 | 1,042,625 | 2014 | 1,016,518 |

| 1935 | 34,956 | 1955 | 237,790 | 1975 | 385,378 | 1995 | 720,177 | 2007 | 1,052,415 | 2011 | 1,062,040 | 2015 | 1,051,031 |

| 1940 | 70,756 | 1960 | 265,398 | 1980 | 524,295 | 2000 | 841,002 | 2008 | 1,107,126 | 2012 | 1,031,631 | ||

| 1945 | 38,119 | 1965 | 296,697 | 1985 | 568,149 | 2005 | 1,122,257 | 2009 | 1,130,818 | 2013 | 990,553 |

| Decade | Average per year |

|---|---|

| 1930–39 | 69,900 |

| 1940–49 | 85,700 |

| 1950–59 | 249,900 |

| 1960–69 | 321,400 |

| 1970–79 | 424,800 |

Source: US Department of Homeland Security, Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status: Fiscal Years 1820 to 2015[53]

Contemporary immigration

Until the 1930s most legal immigrants were male. By the 1990s women accounted for just over half of all legal immigrants.[54] Contemporary immigrants tend to be younger than the native population of the United States, with people between the ages of 15 and 34 substantially overrepresented.[55] Immigrants are also more likely to be married and less likely to be divorced than native-born Americans of the same age.[56]

Immigrants are likely to move to and live in areas populated by people with similar backgrounds. This phenomenon has held true throughout the history of immigration to the United States.[57] Seven out of ten immigrants surveyed by Public Agenda in 2009 said they intended to make the U.S. their permanent home, and 71% said if they could do it over again they would still come to the US. In the same study, 76% of immigrants say the government has become stricter on enforcing immigration laws since the September 11, 2001 attacks ("9/11"), and 24% report that they personally have experienced some or a great deal of discrimination.[58]

Public attitudes about immigration in the U.S. were heavily influenced in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. After the attacks, 52% of Americans believed that immigration was a good thing overall for the U.S., down from 62% the year before, according to a 2009 Gallup poll.[59] A 2008 Public Agenda survey found that half of Americans said tighter controls on immigration would do "a great deal" to enhance U.S. national security.[60] Harvard political scientist and historian Samuel P. Huntington argued in Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity that a potential future consequence of continuing massive immigration from Latin America, especially Mexico, could lead to the bifurcation of the United States.[61][62]

The population of illegal Mexican immigrants in the US fell from approximately 7 million in 2007 to 6.1 million in 2011[63] Commentators link the reversal of the immigration trend to the economic downturn that started in 2008 and which meant fewer available jobs, and to the introduction of tough immigration laws in many states.[64][65][66][67] According to the Pew Hispanic Center the net immigration of Mexican born persons had stagnated in 2010, and tended toward going into negative figures.[68]

More than 80 cities in the United States,[69] including Washington D.C., New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, Detroit, Jersey City, Minneapolis, Miami, Denver, Baltimore, Seattle, Portland, Oregon and Portland, Maine, have sanctuary policies, which vary locally.[70]

Ethnicity

- Inflow of New Legal Permanent Residents by region, in 2013, 2014 and 2015

| Region | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | 396,605 | 398,069 | 438,435 | |

| Asia | 400,548 | 430,508 | 419,297 | |

| Africa | 98,304 | 98,413 | 101,415 | |

| Europe | 86,556 | 83,266 | 85,803 | |

| Australia and Oceania | 5,277 | 5,122 | 5,404 | |

| Unknown | 3,263 | 1,150 | 677 | |

| Total | 990,553 | 1,016,518 | 1,051,031 |

Source: US Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics[72][73][71]

Top 10 sending countries in 2014 and 2015[74]

| Country | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Mexico | 134,052 | 158,619 |

| 2. China | 76,089 | 74,558 |

| 3. India | 77,908 | 64,116 |

| 4. Philippines | 49,996 | 56,478 |

| 5. Cuba | 46,679 | 54,396 |

| 6. Dominican Rep. | 44,577 | 50,610 |

| 7. Vietnam | 30,283 | 30,832 |

| 8. Iraq | 19,153 | 21,107 |

| 9. El Salvador | 19,273 | 19,487 |

| 10. Pakistan | 18,612 | 18,057 |

| Total | 1,016,518 | 1,051,031 |

Demography

Extent and destinations

| Year[75] | Number of foreign-born | Percent foreign-born |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,244,602 | 9.7 |

| 1860 | 4,138,697 | 13.2 |

| 1870 | 5,567,229 | 14.4 |

| 1880 | 6,679,943 | 13.3 |

| 1890 | 9,249,547 | 14.8 |

| 1900 | 10,341,276 | 13.6 |

| 1910 | 13,515,886 | 14.7 |

| 1920 | 13,920,692 | 13.2 |

| 1930 | 14,204,149 | 11.6 |

| 1940 | 11,594,896 | 8.8 |

| 1950 | 10,347,395 | 6.9 |

| 1960 | 9,738,091 | 5.4 |

| 1970 | 9,619,302 | 4.7 |

| 1980 | 14,079,906 | 6.2 |

| 1990 | 19,767,316 | 7.9 |

| 2000 | 31,107,889 | 11.1 |

| 2010[76] | 39,956,000 | 12.9 |

| 2015[77] | 43,290,000 | 13.4 |

The United States admitted more legal immigrants from 1991 to 2000, between ten and eleven million, than in any previous decade. In the most recent decade, the ten million legal immigrants that settled in the U.S. represent an annual growth of only about 0.3% as the U.S. population grew from 249 million to 281 million. By comparison, the highest previous decade was the 1900s, when 8.8 million people arrived, increasing the total U.S. population by one percent every year. Specifically, "nearly 15% of Americans were foreign-born in 1910, while in 1999, only about 10% were foreign-born."[78]

By 1970, immigrants accounted for 4.7 percent of the US population and rising to 6.2 percent in 1980, with an estimated 12.5 percent in 2009.[79] As of 2010[update], 25% of US residents under age 18 were first- or second-generation immigrants.[80] Eight percent of all babies born in the U.S. in 2008 belonged to illegal immigrant parents, according to a recent analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by the Pew Hispanic Center.[81]

Legal immigration to the U.S. increased from 250,000 in the 1930s, to 2.5 million in the 1950s, to 4.5 million in the 1970s, and to 7.3 million in the 1980s, before resting at about 10 million in the 1990s.[82] Since 2000, legal immigrants to the United States number approximately 1,000,000 per year, of whom about 600,000 are Change of Status who already are in the U.S. Legal immigrants to the United States now are at their highest level ever, at just over 37,000,000 legal immigrants. Illegal immigration may be as high as 1,500,000 per year with a net of at least 700,000 illegal immigrants arriving every year.[83][84] Immigration led to a 57.4% increase in foreign born population from 1990 to 2000.[85]

While immigration has increased drastically over the last century, the foreign born share of the population is, at 13.4, only somewhat below what it was at its peak in 1910 at 14.7%. A number of factors may be attributed to the decrease in the representation of foreign born residents in the United States. Most significant has been the change in the composition of immigrants; prior to 1890, 82% of immigrants came from North and Western Europe. From 1891 to 1920, that number dropped to 25%, with a rise in immigrants from East, Central, and South Europe, summing up to 64%. Animosity towards these different and foreign immigrants rose in the United States, resulting in much legislation to limit immigration.[citation needed]

Contemporary immigrants settle predominantly in seven states, California, New York, Florida, Texas, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Illinois, comprising about 44% of the U.S. population as a whole. The combined total immigrant population of these seven states was 70% of the total foreign-born population in 2000. If current birth rate and immigration rates were to remain unchanged for another 70 to 80 years, the U.S. population would double to nearly 600 million.[86]

In 1900, when the U.S. population was 76 million, there were an estimated 500,000 Hispanics.[87] The Census Bureau projects that by 2050, one-quarter of the population will be of Hispanic descent.[88] This demographic shift is largely fueled by immigration from Latin America.[89][90]

Origin

- Foreign born population of the United States by country of birth in 2013 (U.S. Census Bureau)[91] and number of immigrants between 1986 and 2012 by country of birth[92]

A country is included in the table if it exceeded 50,000 in either category.

| Country of birth | Population (2013) | Immigrants (1986–2012) |

|---|---|---|

| 316,497,531 | 3,132 | |

| Total foreign born | 41,347,945 | 26,147,963 |

| 11,584,977 | 5,551,757 | |

| 2,383,831 | 1,399,667 | |

| 2,034,677 | 1,323,011 | |

| 1,843,989 | 1,480,946 | |

| 1,281,010 | 955,967 | |

| 1,252,067 | 676,776 | |

| 1,144,024 | 666,657 | |

| 1,070,335 | 609,321 | |

| 991,046 | 904,721 | |

| 902,293 | 353,122 | |

| 840,192 | 394,790 | |

| 714,743 | 507,741 | |

| 695,489 | 383,037 | |

| 694,600 | 661,493 | |

| 677,231 | 498,551 | |

| 593,980 | 536,657 | |

| 584,184 | 192,676 | |

| 533,598 | 178,321 | |

| 440,292 | 320,611 | |

| 432,601 | 360,669 | |

| 427,906 | 243,217 | |

| 390,934 | 476,306 | |

| 363,972 | 358,586 | |

| 354,305 | 69,111 | |

| 345,187 | 306,203 | |

| 342,603 | 347,237 | |

| 339,970 | 172,893 | |

| 337,040 | 214,266 | |

| 259,815 | 214,995 | |

| 240,619 | 191,701 | |

| 234,465 | 227,497 | |

| 233,547 | 174,168 | |

| 232,026 | 157,689 | |

| 203,179 | 215,164 | |

| 200,894 | 153,897 | |

| 197,724 | 143,411 | |

| 196,154 | 110,235 | |

| 195,805 | 202,518 | |

| 182,473 | 53,831 | |

| 176,443 | 153,755 | |

| 170,394 | 87,601 | |

| 170,086 | 98,999 | |

| 164,746 | 106,183 | |

| 157,302 | 140,887 | |

| 149,377 | 130,542 | |

| 137,084 | 37,406 | |

| 128,350 | 104,586 | |

| 127,079 | 106,568 | |

| 124,256 | 113,727 | |

| 116,775 | 94,792 | |

| 112,240 | 129,481 | |

| 110,678 | 92,891 | |

| 109,667 | 85,415 | |

| 102,475 | 41,328 | |

| 101,024 | 57,628 | |

| 97,585 | 54,573 | |

| 95,191 | 69,992 | |

| 88,894 | n/a | |

| 87,456 | 58,841 | |

| 85,085 | 35,117 | |

| 81,047 | 84,031 | |

| 79,924 | 52,177 | |

| 79,122 | 62,201 | |

| 78,934 | 68,864 | |

| 78,909 | 74,632 | |

| 78,797 | 12,926 | |

| 78,659 | 47,648 | |

| 74,213 | 31,365 | |

| 68,956 | n/a | |

| 67,941 | 68,768 | |

| 67,169 | 59,480 | |

| 65,618 | 104,168 | |

| 64,354 | 27,354 | |

| 63,798 | 76,622 | |

| 52,499 | 25,444 | |

| 51,268 | 51,675 | |

| 50,934 | 58,254 | |

| 50,296 | n/a |

Note: Counts of immigrants since 1986 for Russia includes "Soviet Union (former)", and for Czech Republic includes "Czechoslovakia (former)".

Effects of immigration

Demographics

The Census Bureau estimates the US population will grow from 317 million in 2014 to 417 million in 2060 with immigration, when nearly 20% will be foreign born.[93] A 2015 report from the Pew Research Center projects that by 2065, non-Hispanic whites will account for 46% of the population, down from the 2005 figure of 67%.[94] Non-Hispanic whites made up 85% of the population in 1960.[95] It also foresees the Hispanic population rising from 17% in 2014 to 29% by 2060. The Asian population is expected to nearly double in 2060.[93] Overall, the Pew Report predicts the population of the United States will rise from 296 million in 2005 to 441 million in 2065, but only to 338 million with no immigration.[94]

In 35 of the country's 50 largest cities, non-Hispanic whites were at the last census or are predicted to be in the minority.[96] In California, non-Hispanic whites slipped from 80% of the state's population in 1970 to 42% in 2001[97] and 39% in 2013.[98]

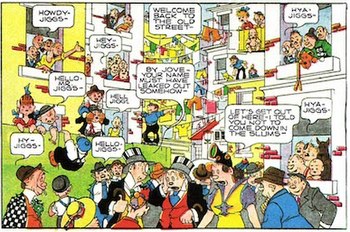

Immigrant segregation declined in the first half of the 20th century, but has been rising over the past few decades. This has caused questioning of the correctness of describing the United States as a melting pot. One explanation is that groups with lower socioeconomic status concentrate in more densely populated area that have access to public transit while groups with higher socioeconomic status move to suburban areas. Another is that some recent immigrant groups are more culturally and linguistically different from earlier groups and prefer to live together due to factors such as communication costs.[99] Another explanation for increased segregation is white flight.[100]

- Place of birth for the foreign-born population in the United States

| Top ten countries | 2015 | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 11,643,298 | 11,711,103 | 9,177,487 | 4,298,014 |

| China | 2,676,697 | 2,166,526 | 1,518,652 | 921,070 |

| India | 2,389,639 | 1,780,322 | 1,022,552 | 450,406 |

| Philippines | 1,982,369 | 1,777,588 | 1,369,070 | 912,674 |

| El Salvador | 1,352,357 | 1,214,049 | 817,336 | 465,433 |

| Vietnam | 1,300,515 | 1,240,542 | 988,174 | 543,262 |

| Cuba | 1,210,674 | 1,104,679 | 872,716 | 736,971 |

| Dominican Republic | 1,063,239 | 879,187 | 687,677 | 347,858 |

| South Korea | 1,060,019 | 1,100,422 | 864,125 | 568,397 |

| Guatemala | 927,593 | 830,824 | 480,665 | 225,739 |

| All of Latin America | 21,224,087 | 16,086,974 | 8,407,837 | |

| All Immigrants | 43,289,646 | 39,955,854 | 31,107,889 | 19,767,316 |

Source: 1990, 2000 and 2010 decennial Census and 2015 American Community Survey

Economic

A survey of leading economists shows a consensus behind the view that high-skilled immigration makes the average American better off.[101] A survey of the same economists also shows strong support behind the notion that low-skilled immigration makes the average American better off.[102] According to David Card, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston, "most existing studies of the economic impacts of immigration suggest these impacts are small, and on average benefit the native population".[103] In a survey of the existing literature, Örn B Bodvarsson and Hendrik Van den Berg write, "a comparison of the evidence from all the studies... makes it clear that, with very few exceptions, there is no strong statistical support for the view held by many members of the public, namely that immigration has an adverse effect on native-born workers in the destination country."[104]

Overall economic prosperity

Whereas the impact on the average native tends to be small and positive, studies show more mixed results for low-skilled natives, but whether the effects are positive or negative, they tend to be small either way.[105]

Immigrants may often do types of work that natives are largely unwilling to do, contributing to greater economic prosperity for the economy as a whole: for instance, Mexican migrant workers taking up manual farm work in the United States has close to zero effect on native employment in that occupation, which means that the effect of Mexican workers on U.S. employment outside farm work was therefore most likely positive, since they raised overall economic productivity.[106] Research indicates that immigrants are more likely to work in risky jobs than U.S.-born workers, partly due to differences in average characteristics, such as immigrants' lower English language ability and educational attainment.[107] Further, some studies indicate that higher ethnic concentration in metropolitan areas is positively related to the probability of self-employment of immigrants.[108]

Research also suggests that diversity has a net positive effect on productivity[109][110] and economic prosperity.[111][111][112][113][114] A study by Harvard economist Nathan Nunn, Yale economist Nancy Qian and LSE economist Sandra Sequeira found that the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1920) has had substantially beneficial long-term effects on U.S. economic prosperity: "locations with more historical immigration today have higher incomes, less poverty, less unemployment, higher rates of urbanization, and greater educational attainment. The long-run effects appear to arise from the persistence of sizeable short-run benefits, including earlier and more intensive industrialization, increased agricultural productivity, and more innovation."[115] The authors also find that the immigration had short-term benefits: "that there is no evidence that these long-run benefits come at short-run costs. In fact, immigration immediately led to economic benefits that took the form of higher incomes, higher productivity, more innovation, and more industrialization."[116]

Research also finds that migration leads to greater trade in goods and services.[117][118][119][120] Using 130 years of data on historical migrations to the United States, one study finds "that a doubling of the number of residents with ancestry from a given foreign country relative to the mean increases by 4.2 percentage points the probability that at least one local firm invests in that country, and increases by 31% the number of employees at domestic recipients of FDI from that country. The size of these effects increases with the ethnic diversity of the local population, the geographic distance to the origin country, and the ethno-linguistic fractionalization of the origin country."[121]

Fiscal effects

A 2011 literature review of the economic impacts of immigration found that the net fiscal impact of migrants varies across studies but that the most credible analyses typically find small and positive fiscal effects on average.[122] According to the authors, "the net social impact of an immigrant over his or her lifetime depends substantially and in predictable ways on the immigrant's age at arrival, education, reason for migration, and similar".[122]

A 2016 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that over a 75-year time horizon, “the fiscal impacts of immigrants are generally positive at the federal level and generally negative at the state and local level.”[123] The reason for the costs to state and local governments is that the cost of educating the immigrants' children falls on state and local governments.[124] According to a 2007 literature review by the Congressional Budget Office, "Over the past two decades, most efforts to estimate the fiscal impact of immigration in the United States have concluded that, in aggregate and over the long term, tax revenues of all types generated by immigrants—both legal and unauthorized—exceed the cost of the services they use."[125]

According to James Smith, a senior economist at Santa Monica-based RAND Corporation and lead author of the United States National Research Council's study "The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration", immigrants contribute as much as $10 billion to the U.S. economy each year.[126] The NRC report found that although immigrants, especially those from Latin America, caused a net loss in terms of taxes paid versus social services received, immigration can provide an overall gain to the domestic economy due to an increase in pay for higher-skilled workers, lower prices for goods and services produced by immigrant labor, and more efficiency and lower wages for some owners of capital. The report also notes that although immigrant workers compete with domestic workers for low-skilled jobs, some immigrants specialize in activities that otherwise would not exist in an area, and thus can be beneficial for all domestic residents.[127]

Immigration and foreign labor documentation fees increased over 80% in 2007, with over 90% of funding for USCIS derived from immigration application fees, creating many USCIS jobs involving immigration to US, such as immigration interview officials, finger print processor, Department of Homeland Security, etc.[128]

Inequality

Overall immigration has not had much effect on native wage inequality[129][130] but low-skill immigration has been linked to greater income inequality in the native population.[131]

Impact of undocumented immigrants

Research on the economic effects of undocumented immigrants is scant but existing peer-reviewed studies suggest that the effects are positive for the native population[132][133] and public coffers.[125] A 2015 study shows that "increasing deportation rates and tightening border control weakens low-skilled labor markets, increasing unemployment of native low-skilled workers. Legalization, instead, decreases the unemployment rate of low-skilled natives and increases income per native."[134] Studies show that legalization of undocumented immigrants would boost the U.S. economy; a 2013 study found that granting legal status to undocumented immigrants would raise their incomes by a quarter (increasing U.S. GDP by approximately $1.4 trillion over a ten-year period),[135] and 2016 study found that "legalization would increase the economic contribution of the unauthorized population by about 20%, to 3.6% of private-sector GDP."[136]

A 2007 literature by the Congressional Budget Office found that estimating the fiscal effects of undocumented immigrants has proven difficult: "currently available estimates have significant limitations; therefore, using them to determine an aggregate effect across all states would be difficult and prone to considerable error". The impact of undocumented immigrants differs on federal levels than state and local levels,[125] with research suggesting modest fiscal costs at the state and local levels but with substantial fiscal gains at the federal level.[137]

In 2009, a study by the Cato Institute, a free market think tank, found that legalization of low-skilled illegal resident workers in the US would result in a net increase in US GDP of $180 billion over ten years.[138] The Cato Institute study did not examine the impact on per capita income for most Americans. Jason Riley notes that because of progressive income taxation, in which the top 1% of earners pay 37% of federal income taxes (even though they actually pay a lower tax percentage based on their income), 60% of Americans collect more in government services than they pay in, which also reflects on immigrants.[139] In any event, the typical immigrant and his children will pay a net $80,000 more in their lifetime than they collect in government services according to the NAS.[140] Legal immigration policy is set to maximize net taxation. Illegal immigrants even after an amnesty tend to be recipients of more services than they pay in taxes. In 2010, an econometrics study by a Rutgers economist found that immigration helped increase bilateral trade when the incoming people were connected via networks to their country of origin, particularly boosting trade of final goods as opposed to intermediate goods, but that the trade benefit weakened when the immigrants became assimilated into American culture.[141]

According to NPR in 2005, about 3% of illegal immigrants were working in agriculture.[142] The H-2A visa allows U.S. employers to bring foreign nationals to the United States to fill temporary agricultural jobs.[143] The passing of tough immigration laws in several states from around 2009 provides a number of practical case studies. The state of Georgia passed immigration law HB 87 in 2011;[144] this led, according to the coalition of top Kansas businesses, to 50% of its agricultural produce being left to rot in the fields, at a cost to the state of more than $400 million. Overall losses caused by the act were $1 billion; it was estimated that the figure would become over $20 billion if all the estimated 325,000 undocumented workers left Georgia. The cost to Alabama of its crackdown in June 2011 has been estimated at almost $11 billion, with up to 80,000 unauthorized immigrant workers leaving the state.[145]

Impact of refugees

Studies of refugees' impact on native welfare are scant but the existing literature shows a positive fiscal impact and mixed results (negative, positive and no significant effects) on native welfare.[146][147][148][149] A 2017 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that refugees to the United States pay "$21,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits over their first 20 years in the U.S."[148] An internal study by the Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration, which was suppressed and not shown to the public, found that refugees to the United States brought in $63 billion more in government revenues than they cost the government.[149] According to labor economist Giovanni Peri, the existing literature suggests that there are no economic reasons why the American labor market could not easily absorb 100,000 Syrian refugees in a year.[150] Refugees integrate more slowly into host countries' labor markets than labor migrants, in part due to the loss and depreciation of human capital and credentials during the asylum procedure.[151]

Innovation and entrepreneurship

According to one survey of the existing economic literature, "much of the existing research points towards positive net contributions by immigrant entrepreneurs."[152] Areas where immigrant are more prevalent in the United States have substantially more innovation (as measured by patenting and citations).[153] Immigrants to the United States create businesses at higher rates than natives.[154] Mass migration can also boost innovation and growth, as shown by the examples of German Jewish Émigrés to the US[155] and the Mariel boatlift.[156] Immigrants have been linked to greater invention and innovation in the US.[157] According to one report, "immigrants have started more than half (44 of 87) of America's startup companies valued at $1 billion or more and are key members of management or product development teams in over 70 percent (62 of 87) of these companies."[158] Foreign doctoral students are a major source of innovation in the American economy.[159] In the United States, immigrant workers hold a disproportionate share of jobs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM): "In 2013, foreign-born workers accounted for 19.2 percent of STEM workers with a bachelor's degree, 40.7 percent of those with a master's degree, and more than half—54.5 percent—of those with a Ph.D."[160]

The Kauffman Foundation's index of entrepreneurial activity is nearly 40% higher for immigrants than for natives.[161] Immigrants were involved in the founding of many prominent American high-tech companies, such as Google, Yahoo, YouTube, Sun Microsystems, and eBay.[162]

Social

Discrimination

Irish immigration was opposed in the 1850s by the nativist Know Nothing movement, originating in New York in 1843. It was engendered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by Irish Catholic immigrants. On March 14, 1891, a lynch mob stormed a local jail and lynched several Italians following the acquittal of several Sicilian immigrants alleged to be involved in the murder of New Orleans police chief David Hennessy. The Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at limiting immigration overall, and making sure that the nationalities of new arrivals matched the overall national profile.

Business

A 2014 meta-analysis of racial discrimination in product markets found extensive evidence of minority applicants being quoted higher prices for products.[166] A 1995 study found that car dealers "quoted significantly lower prices to white males than to black or female test buyers using identical, scripted bargaining strategies."[167] A 2013 study found that eBay sellers of iPods received 21 percent more offers if a white hand held the iPod in the photo than a black hand.[168]

Criminal justice system

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of racial minorities among crime suspects.[169][170][171][172] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for racial minorities.[173][174][175][176][177] A 2012 study found that "(i) juries formed from all-white jury pools convict black defendants significantly (16 percentage points) more often than white defendants, and (ii) this gap in conviction rates is entirely eliminated when the jury pool includes at least one black member."[175] Research has found evidence of in-group bias, where "black (white) juveniles who are randomly assigned to black (white) judges are more likely to get incarcerated (as opposed to being placed on probation), and they receive longer sentences."[177] In-group bias has also been observed when it comes to traffic citations, as black and white cops are more likely to cite out-groups.[171]

Education

A 2015 study using correspondence tests "found that when considering requests from prospective students seeking mentoring in the future, faculty were significantly more responsive to White males than to all other categories of students, collectively, particularly in higher-paying disciplines and private institutions."[178] Through affirmative action, there is reason to believe that elite colleges favor minority applicants.[179]

Housing

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial discrimination in the American housing market.[166] Minority applicants for housing needed to make many more enquiries to view properties.[166] Geographical steering of African-Americans in US housing remained significant.[166] A 2003 study finds "evidence that agents interpret an initial housing request as an indication of a customer's preferences, but also are more likely to withhold a house from all customers when it is in an integrated suburban neighborhood (redlining). Moreover, agents' marketing efforts increase with asking price for white, but not for black, customers; blacks are more likely than whites to see houses in suburban, integrated areas (steering); and the houses agents show are more likely to deviate from the initial request when the customer is black than when the customer is white. These three findings are consistent with the possibility that agents act upon the belief that some types of transactions are relatively unlikely for black customers (statistical discrimination)."[180]

A report by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development where the department sent African-Americans and whites to look at apartments found that African-Americans were shown fewer apartments to rent and houses for sale.[181]

Labor market

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the American labor market.[166][182][183] A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests—tests where identical CVs for stereotypically black and white names were sent to employers—in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North-America.[183] These correspondence tests showed that equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.[183][184] A study that examine the job applications of actual people provided with identical résumés and similar interview training showed that African-American applicants with no criminal record were offered jobs at a rate as low as white applicants who had criminal records.[185]

Discrimination between minority groups

Racist thinking among and between minority groups does occur;[186][187] examples of this are conflicts between blacks and Korean immigrants,[188] notably in the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, and between African Americans and non-white Latino immigrants.[189][190] There has been a long running racial tension between African American and Mexican prison gangs, as well as significant riots in California prisons where they have targeted each other, for ethnic reasons.[191][192] There have been reports of racially motivated attacks against African Americans who have moved into neighborhoods occupied mostly by people of Mexican origin, and vice versa.[193][194] There has also been an increase in violence between non-Hispanic Anglo Americans and Latino immigrants, and between African immigrants and African Americans.[195]

Assimilation

Measuring assimilation can be difficult due to "ethnic attrition", which refers to when ancestors of migrants cease to self-identify with the nationality or ethnicity of their ancestors. This means that successful cases of assimilation will be underestimated. Research shows that ethnic attrition is sizable in Hispanic and Asian immigrant groups in the United States.[196][197] By taking account of ethnic attrition, the assimilation rate of Hispanics in the United States improves significantly.[196][198] A 2016 paper challenges the view that cultural differences are necessarily an obstacle to long-run economic performance of migrants. It finds that "first generation migrants seem to be less likely to success the more culturally distant they are, but this effect vanishes as time spent in the USA increases."[199]

Religious diversity

Immigration from South Asia and elsewhere has contributed to enlarging the religious composition of the United States. Islam in the United States is growing mainly due to immigration. Hinduism in the United States, Buddhism in the United States, and Sikhism in the United States are other examples.[200]

Since 1992, an estimated 1.7 million Muslims, approximately 1 million Hindus, and approximately 1 million Buddhists have immigrated legally to the United States.[201]

Labor unions

The American Federation of Labor (AFL), a coalition of labor unions formed in the 1880s, vigorously opposed unrestricted immigration from Europe for moral, cultural, and racial reasons. The issue unified the workers who feared that an influx of new workers would flood the labor market and lower wages.[202] Nativism was not a factor because upwards of half the union members were themselves immigrants or the sons of immigrants from Ireland, Germany and Britain. However, nativism was a factor when the AFL even more strenuously opposed all immigration from Asia because it represented (to its Euro-American members) an alien culture that could not be assimilated into American society. The AFL intensified its opposition after 1906 and was instrumental in passing immigration restriction bills from the 1890s to the 1920s, such as the 1921 Emergency Quota Act and the Immigration Act of 1924, and seeing that they were strictly enforced.[203][204]

Mink (1986) concludes that the link between the AFL and the Democratic Party rested in part on immigration issues, noting the large corporations, which supported the Republicans, wanted more immigration to augment their labor force.[205]

United Farm Workers during Cesar Chavez tenure was committed to restricting immigration. Chavez and Dolores Huerta, cofounder and president of the UFW, fought the Bracero Program that existed from 1942 to 1964. Their opposition stemmed from their belief that the program undermined U.S. workers and exploited the migrant workers. Since the Bracero Program ensured a constant supply of cheap immigrant labor for growers, immigrants could not protest any infringement of their rights, lest they be fired and replaced. Their efforts contributed to Congress ending the Bracero Program in 1964. In 1973, the UFW was one of the first labor unions to oppose proposed employer sanctions that would have prohibited hiring illegal immigrants.

On a few occasions, concerns that illegal immigrant labor would undermine UFW strike campaigns led to a number of controversial events, which the UFW describes as anti-strikebreaking events, but which have also been interpreted as being anti-immigrant. In 1969, Chavez and members of the UFW marched through the Imperial and Coachella Valleys to the border of Mexico to protest growers' use of illegal immigrants as strikebreakers. Joining him on the march were Reverend Ralph Abernathy and U.S. Senator Walter Mondale.[citation needed] In its early years, the UFW and Chavez went so far as to report illegal immigrants who served as strikebreaking replacement workers (as well as those who refused to unionize) to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[206][207][208][209][210]

In 1973, the United Farm Workers set up a "wet line" along the United States-Mexico border to prevent Mexican immigrants from entering the United States illegally and potentially undermining the UFW's unionization efforts.[211] During one such event, in which Chavez was not involved, some UFW members, under the guidance of Chavez's cousin Manuel, physically attacked the strikebreakers after peaceful attempts to persuade them not to cross the border failed.[212][213][214]

Political

A Boston Globe article attributed Barack Obama's win in the 2008 U.S. Presidential election to a marked reduction over the preceding decades in the percentage of whites in the American electorate, attributing this demographic change to the Immigration Act of 1965.[25] The article quoted Simon Rosenberg, president and founder of the New Democrat Network, as having said that the Act is "the most important piece of legislation that no one's ever heard of," and that it "set America on a very different demographic course than the previous 300 years."[25]

Immigrants differ on their political views; however, the Democratic Party is considered to be in a far stronger position among immigrants overall.[215][216] Research shows that religious affiliation can also significantly impact both their social values and voting patterns of immigrants, as well as the broader American population. Hispanic evangelicals, for example, are more strongly conservative than non-Hispanic evangelicals.[217] This trend is often similar for Hispanics or others strongly identifying with the Catholic Church, a religion that strongly opposes abortion and gay marriage.

The key interests groups that lobby on immigration are religious, ethnic and business groups, together with some liberals and some conservative public policy organizations. Both the pro- and anti- groups affect policy.[218][dead link]

Studies have suggested that some special interest group lobby for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when affecting other groups.[citation needed]

A 2007 paper found that both pro- and anti-immigration special interest groups play a role in migration policy. "Barriers to migration are lower in sectors in which business lobbies incur larger lobbying expenditures and higher in sectors where labor unions are more important."[219] A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."[220]

After the 2010 election, Gary Segura of Latino Decisions stated that Hispanic voters influenced the outcome and "may have saved the Senate for Democrats".[221] Several ethnic lobbies support immigration reforms that would allow illegal immigrants that have succeeded in entering to gain citizenship. They may also lobby for special arrangements for their own group. The Chairman for the Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get—'as will every other ethnic group in the country.'"[222][223] The irrendentist and ethnic separatist movements for Reconquista and Aztlán see immigration from Mexico as strengthening their cause.[224][225]

The book Ethnic Lobbies and US Foreign Policy (2009) states that several ethnic special interest groups are involved in pro-immigration lobbying. Ethnic lobbies also influence foreign policy. The authors write that "Increasingly, ethnic tensions surface in electoral races, with House, Senate, and gubernatorial contests serving as proxy battlegrounds for antagonistic ethnoracial groups and communities. In addition, ethnic politics affect party politics as well, as groups compete for relative political power within a party". However, the authors argue that currently ethnic interest groups, in general, do not have too much power in foreign policy and can balance other special interest groups.[226]

In a 2012 news story, Reuters reported, "Strong support from Hispanics, the fastest-growing demographic in the United States, helped tip President Barack Obama's fortunes as he secured a second term in the White House, according to Election Day polling."[227]

Lately, there is talk among several Republican leaders, such as governors Bobby Jindal and Susana Martinez, of taking a new, friendlier approach to immigration. Former US Secretary of Commerce Carlos Gutierrez is promoting the creation of Republicans for Immigration Reform.[228][229]

Bernie Sanders opposes guest worker programs[230] and is also skeptical about skilled immigrant (H-1B) visas, saying, "Last year, the top 10 employers of H-1B guest workers were all offshore outsourcing companies. These firms are responsible for shipping large numbers of American information technology jobs to India and other countries."[122][231] In an interview with Vox he stated his opposition to an open borders immigration policy, describing it as:

...a right-wing proposal, which says essentially there is no United States...you're doing away with the concept of a nation-state. What right-wing people in this country would love is an open-border policy. Bring in all kinds of people, work for $2 or $3 an hour, that would be great for them. I don’t believe in that. I think we have to raise wages in this country, I think we have to do everything we can to create millions of jobs.[232][233]

Health

The issue of the health of immigrants and the associated cost to the public has been largely discussed. On average, per capita health care spending is lower for immigrants than it is for native-born Americans.[234] The non-emergency use of emergency rooms ostensibly indicates an incapacity to pay, yet some studies allege disproportionately lower access to unpaid health care by immigrants.[235] For this and other reasons, there have been various disputes about how much immigration is costing the United States public health system.[236] University of Maryland economist and Cato Institute scholar Julian Lincoln Simon concluded in 1995 that while immigrants probably pay more into the health system than they take out, this is not the case for elderly immigrants and refugees, who are more dependent on public services for survival.[237]

Immigration from areas of high incidences of disease is thought to have fueled the resurgence of tuberculosis (TB), chagas, and hepatitis in areas of low incidence.[238] According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), TB cases among foreign-born individuals remain disproportionately high, at nearly nine times the rate of U.S.-born persons.[239][240] To reduce the risk of diseases in low-incidence areas, the main countermeasure has been the screening of immigrants on arrival.[241] HIV/AIDS entered the United States in around 1969, likely through a single infected immigrant from Haiti.[242][243] Conversely, many new HIV infections in Mexico can be traced back to the United States.[244] People infected with HIV were banned from entering the United States in 1987 by executive order, but the 1993 statute supporting the ban was lifted in 2009. The executive branch is expected to administratively remove HIV from the list of infectious diseases barring immigration, but immigrants generally would need to show that they would not be a burden on public welfare.[245] Researchers have also found what is known as the "healthy immigrant effect", in which immigrants in general tend to be healthier than individuals born in the U.S.[246][247]

Crime

There is no empirical evidence that immigration increases crime in the United States.[5] In fact, a majority of studies in the U.S. have found lower crime rates among immigrants than among non-immigrants, and that higher concentrations of immigrants are associated with lower crime rates.[6]

Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partly explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate.[248][249][250][251][252] A 2005 study showed that immigration to large U.S. metropolitan areas does not increase, and in some cases decreases, crime rates there.[253] A 2009 study found that recent immigration was not associated with homicide in Austin, Texas.[254] The low crime rates of immigrants to the United States despite having lower levels of education, lower levels of income and residing in urban areas (factors that should lead to higher crime rates) may be due to lower rates of antisocial behavior among immigrants.[255] A 2015 study found that Mexican immigration to the United States was associated with an increase in aggravated assaults and a decrease in property crimes.[256] A 2016 study finds no link between immigrant populations and violent crime, although there is a small but significant association between undocumented immigrants and drug-related crime.[257]

Research finds that Secure Communities, an immigration enforcement program which led to a quarter of a million of detentions (when the study was published; November 2014), had no observable impact on the crime rate.[258] A 2015 study found that the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which legalized almost 3 million immigrants, led to "decreases in crime of 3–5 percent, primarily due to decline in property crimes, equivalent to 120,000-180,000 fewer violent and property crimes committed each year due to legalization".[259] According to one study, sanctuary cities—which adopt policies designed to not prosecute people solely for being an illegal immigrant—have no statistically meaningful effect on reported crime.[260]

One of the first political analyses in the U.S. of the relationship between immigration and crime was performed in the beginning of the 20th century by the Dillingham Commission, which found a relationship especially for immigrants from non-Northern European countries, resulting in the sweeping 1920s immigration reduction acts, including the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which favored immigration from northern and western Europe.[261] Recent research is skeptical of the conclusion drawn by the Dillingham Commission. One study finds that "major government commissions on immigration and crime in the early twentieth century relied on evidence that suffered from aggregation bias and the absence of accurate population data, which led them to present partial and sometimes misleading views of the immigrant-native criminality comparison. With improved data and methods, we find that in 1904, prison commitment rates for more serious crimes were quite similar by nativity for all ages except ages 18 and 19, for which the commitment rate for immigrants was higher than for the native-born. By 1930, immigrants were less likely than natives to be committed to prisons at all ages 20 and older, but this advantage disappears when one looks at commitments for violent offenses."[262]

For the early twentieth century, one study found that immigrants had "quite similar" imprisonment rates for major crimes as natives in 1904 but lower for major crimes (except violent offenses; the rate was similar) in 1930.[262] Contemporary commissions used dubious data and interpreted it in questionable ways.[262]

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of immigrants among crime suspects.[263][170][264][172] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for immigrants.[173][174][175][176][177]

Education

Scientific laboratories and startup internet opportunities have been a powerful American magnet. By 2000, 23% of scientists with a PhD in the U.S. were immigrants, including 40% of those in engineering and computers.[265] Roughly a third of the United State's college and universities graduate students in STEM fields are foreign nationals—in some states it is well over half of their graduate students. On Ash Wednesday, March 5, 2014, the presidents of 28 Catholic and Jesuit colleges and universities, joined the "Fast for Families" movement.[266] The "Fast for Families" movement reignited the immigration debate in the fall of 2013 when the movement's leaders, supported by many members of Congress and the President, fasted for twenty-two days on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[267]

A study on public schools in California found that white enrollment declined in response to increases in the number of Spanish-speaking Limited English Proficient and Hispanic students. This white flight was greater for schools with relatively larger proportions of Spanish-speaking Limited English Proficient.[100]

A North Carolina study found that the presence of Latin American children in schools had no significant negative effects on peers, but that students with limited English skills had slight negative effects on peers.[268]

Public opinion