Michael Jackson: Difference between revisions

Awardmaniac (talk | contribs) →Further sexual abuse allegations: trimmed |

Awardmaniac (talk | contribs) →Further sexual abuse allegations: removed unnecessary to many sources |

||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

===Further sexual abuse allegations=== |

===Further sexual abuse allegations=== |

||

In 2013, choreographer [[Wade Robson]] and James Safechuck filed a $1.5 billion-dollar civil lawsuit claiming Jackson had sexually abused them as children.<ref>{{cite magazine|first= Joe |last= Vogel |title= What You Should Know About the New Michael Jackson Documentary |magazine= Forbes |date= January 29, 2019 |accessdate= February 10, 2019 |url= https://www.forbes.com/sites/joevogel/2019/01/29/what-you-should-know-about-the-new-michael-jackson-documentary/}}</ref> Both Robson and Safechuck had been friends with Michael Jackson, and both had been witnesses for the defence when Jackson was accused of child sexual abuse during his lifetime.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-sundance-michael-jackson-robson-safechuck-20190124-story.html|title=Michael Jackson documentary accusers Wade Robson and James Safechuck: A brief history of their abuse claims|first=Amy|last=Kaufman|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=January 25, 2019|accessdate=March 5, 2019}}</ref> On May 16, 2013, Robson alleged on ''[[Today (U.S. TV program)|The Today Show]]'' that Jackson had abused him for seven years, beginning when Robson was seven years old.<ref>{{cite news|title= Choreographer: Michael Jackson 'sexually abused me' |work= [[Today (U.S. TV program)|Today]] |url= https://www.today.com/video/choreographer-michael-jackson-sexually-abused-me-30450243877 |date= May 16, 2013 |accessdate= October 21, 2017}}</ref> Robson had previously testified in defense of Jackson in the 2005 trial.<ref>{{cite news|first= John M. |last= Broder |title= 2 Witnesses Say They Shared Jackson's Bed and Were Never Molested |date= May 6, 2005 |newspaper= The New York Times |url= https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/06/us/2-witnesses-say-they-shared-jacksons-bed-and-were-never-molested.html |accessdate= May 31, 2015}}</ref> On December 19, 2017, Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff dismissed the lawsuit because Robson had filed too late.<ref>{{cite press release|first= Andrew |last= Dalton |title= APNewsBreak: Michael Jackson Sex Abuse Lawsuit Dismissed |agency= Associated Press |date= December 20, 2017 |accessdate= December 21, 2017 |url= https://www.usnews.com/news/entertainment/articles/2017-12-19/apnewsbreak-michael-jackson-sex-abuse-lawsuit-dismissed}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title= |

In 2013, choreographer [[Wade Robson]] and James Safechuck filed a $1.5 billion-dollar civil lawsuit claiming Jackson had sexually abused them as children.<ref>{{cite magazine|first= Joe |last= Vogel |title= What You Should Know About the New Michael Jackson Documentary |magazine= Forbes |date= January 29, 2019 |accessdate= February 10, 2019 |url= https://www.forbes.com/sites/joevogel/2019/01/29/what-you-should-know-about-the-new-michael-jackson-documentary/}}</ref> Both Robson and Safechuck had been friends with Michael Jackson, and both had been witnesses for the defence when Jackson was accused of child sexual abuse during his lifetime.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-sundance-michael-jackson-robson-safechuck-20190124-story.html|title=Michael Jackson documentary accusers Wade Robson and James Safechuck: A brief history of their abuse claims|first=Amy|last=Kaufman|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=January 25, 2019|accessdate=March 5, 2019}}</ref> On May 16, 2013, Robson alleged on ''[[Today (U.S. TV program)|The Today Show]]'' that Jackson had abused him for seven years, beginning when Robson was seven years old.<ref>{{cite news|title= Choreographer: Michael Jackson 'sexually abused me' |work= [[Today (U.S. TV program)|Today]] |url= https://www.today.com/video/choreographer-michael-jackson-sexually-abused-me-30450243877 |date= May 16, 2013 |accessdate= October 21, 2017}}</ref> Robson had previously testified in defense of Jackson in the 2005 trial.<ref>{{cite news|first= John M. |last= Broder |title= 2 Witnesses Say They Shared Jackson's Bed and Were Never Molested |date= May 6, 2005 |newspaper= The New York Times |url= https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/06/us/2-witnesses-say-they-shared-jacksons-bed-and-were-never-molested.html |accessdate= May 31, 2015}}</ref> On December 19, 2017, Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff dismissed the lawsuit because Robson had filed too late.<ref>{{cite press release|first= Andrew |last= Dalton |title= APNewsBreak: Michael Jackson Sex Abuse Lawsuit Dismissed |agency= Associated Press |date= December 20, 2017 |accessdate= December 21, 2017 |url= https://www.usnews.com/news/entertainment/articles/2017-12-19/apnewsbreak-michael-jackson-sex-abuse-lawsuit-dismissed}}</ref> The documentary ''[[Leaving Neverland]]'' (2019) covers Jackson's alleged sexual abuse of Robson and Safechuck.<ref>{{cite news |title=Michael Jackson 'abused us hundreds of times' |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-47403951 |date=February 28, 2019}}</ref> It was the first to cover the case in a detailed fashion from the point of view of the alleged victims.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/2/27/18241432/leaving-neverland-review-michael-jackson-hbo-safechuck-robson|title=Leaving Neverland makes a devastating case against Michael Jackson|first=Alissa|last=Wilkinson|date=February 27, 2019|website=Vox}}</ref> The Jackson family condemned ''Leaving Neverland'' as a "public lynching" and insisted he was innocent.<ref>{{cite magazine|title= Michael Jackson's Family Calls 'Leaving Neverland' Documentary a 'Public Lynching |magazine= [[Variety (magazine)|Variety]] |date= January 28, 2019 |accessdate= January 29, 2019 |url= https://variety.com/2019/music/news/michael-jackson-family-leaving-neverland-public-lynching-1203120387/}}</ref> |

||

The documentary ''[[Leaving Neverland]]'' (2019) covers Jackson's alleged sexual abuse of Robson and Safechuck.<ref>{{cite news |title=Michael Jackson 'abused us hundreds of times' |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-47403951 |date=February 28, 2019}}</ref> It was the first to cover the case in a detailed fashion from the point of view of the alleged victims.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/2/27/18241432/leaving-neverland-review-michael-jackson-hbo-safechuck-robson|title=Leaving Neverland makes a devastating case against Michael Jackson|first=Alissa|last=Wilkinson|date=February 27, 2019|website=Vox}}</ref> The Jackson family condemned ''Leaving Neverland'' as a "public lynching" and insisted he was innocent.<ref>{{cite magazine|title= Michael Jackson's Family Calls 'Leaving Neverland' Documentary a 'Public Lynching |magazine= [[Variety (magazine)|Variety]] |date= January 28, 2019 |accessdate= January 29, 2019 |url= https://variety.com/2019/music/news/michael-jackson-family-leaving-neverland-public-lynching-1203120387/}}</ref> |

|||

=== Posthumous releases === |

=== Posthumous releases === |

||

Revision as of 10:53, 6 March 2019

Michael Jackson | |

|---|---|

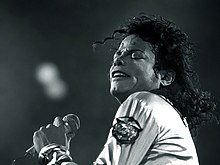

Performing at the Wiener Stadion in Vienna, Austria on June 2, 1988 | |

| Born | Michael Joseph Jackson August 29, 1958 Gary, Indiana, US |

| Died | June 25, 2009 (aged 50) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Cause of death | Cardiac arrest induced by acute propofol and benzodiazepine intoxication |

| Burial place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, US |

| Other names | Michael Joe Jackson |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Michael Jr., Paris, and Blanket |

| Parents |

|

| Family | Jackson family |

| Awards | List of awards and nominations |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals |

| Years active | 1964–2009 |

| Labels | |

| Website | michaeljackson |

| Signature | |

| |

Michael Joseph Jackson (August 29, 1958 – June 25, 2009) was an American singer, songwriter and dancer. Dubbed the "King of Pop", he is regarded as one of the most significant cultural icons of the 20th century and one of the greatest entertainers of all time. Jackson's contributions to music, dance, and fashion, along with his publicized personal life made him a global figure in popular culture for over four decades.

The eighth child of the Jackson family, Michael made his professional debut in 1964 with his elder brothers Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, and Marlon as a member of the Jackson 5. He began his solo career in 1971 while at Motown Records. With his albums Off the Wall (1979) and Thriller (1982)—the latter estimated as the best-selling album of all time—Jackson became a dominant figure in popular music and began setting numerous sales records, including with Bad (1987), the first album to have five number-one singles in the US. His music videos are credited with breaking racial barriers and transforming the medium into an art form and promotional tool, and their popularity helped bring the television channel MTV to fame. He continued to innovate with his music videos throughout the 1990s and forged a reputation as a touring artist. Through stage and video performances, Jackson popularized a number of complicated dance techniques, such as the robot and the moonwalk, to which he gave the name. His distinctive sound and style has influenced numerous artists of various genres.

Jackson is the third-best-selling music artist of all time, with estimated sales of over 350 million records worldwide.[nb 1] Several of his albums rank among the world's best-selling. He won hundreds of awards, more than any other artist in the history of popular music, is one of the few artists to have been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice, and is the only dancer from pop and rock to have been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Dance Hall of Fame. His other achievements include Guinness world records (including the Most Successful Entertainer of All Time), 15 Grammy Awards, 26 American Music Awards (more than any other artist), and 13 number-one singles in the US during his solo career—more than any other male artist in the Hot 100 era.

Jackson became a figure of controversy in the late 1980s due to his changing appearance, relationships, and behavior. In 1993, he was accused of sexually abusing the child of a family friend; the case led to an investigation and was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount in 1994. In 2005, he was tried and acquitted of further child sexual abuse allegations and several other charges. In 2009, while preparing for a series of comeback concerts, This Is It, Jackson died of acute propofol and benzodiazepine intoxication. Jackson's death triggered a global outpouring of grief, and a live broadcast of his public memorial service was viewed around the world. Conrad Murray, his personal physician, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and incarcerated. In 2014, Jackson became the first artist in history to have a top ten single in the Billboard Hot 100 in five different decades. In 2016, Jackson's estate earned $825 million, the highest yearly amount ever recorded by Forbes.

Life and career

1958–1975: Early life and the Jackson 5

Michael Joseph Jackson[8][9] was born in Gary, Indiana, near Chicago, on August 29, 1958.[10][11] He was the eighth of ten children in the Jackson family, a working-class African-American family living in a two-bedroom house on Jackson Street.[12][13] His mother, Katherine Esther Jackson (née Scruse), left the Baptist tradition in 1963 to become a devout Jehovah's Witness.[14] She played clarinet and piano and had aspired to be a country-and-western performer; she worked part-time at Sears to support the family.[15] His father, Joseph Walter "Joe" Jackson, a former boxer, was a steelworker at U.S. Steel. Joe played guitar with a local rhythm and blues band, the Falcons, to supplement the family's income.[16] Despite being a convinced Lutheran, Joe followed his wife's faith, as did all their children.[14] His father's great-grandfather, July "Jack" Gale, was a Native American medicine man and US Army scout.[17] Michael grew up with three sisters (Rebbie, La Toya, and Janet) and five brothers (Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, Marlon, and Randy).[18] A sixth brother, Marlon's twin Brandon, died shortly after birth.[19]

Jackson had a troubled relationship with his father.[20][21] In 2003, Joe acknowledged that he had regularly whipped him.[22] Joe was also said to have verbally abused his son, often saying that he had a "fat nose".[23] Jackson stated that he was physically and emotionally abused during incessant rehearsals; he credited his father's strict discipline with playing a large role in his success.[20] He recalled that Joe often sat in a chair with a belt in his hand as he and his siblings rehearsed, and that "if you didn't do it the right way, he would tear you up, really get you".[24][25]

Katherine Jackson later stated that although whipping is considered abuse today, it was common at the time.[26][27][28] Jackie, Tito, Jermaine and Marlon have said that their father was not abusive and that the whippings, which were harder on Michael because he was younger, kept them disciplined and out of trouble.[29] In an interview with Oprah Winfrey broadcast in February 1993, Jackson acknowledged that his youth had been lonely and isolating.[30] His deep dissatisfaction with his appearance, his nightmares and chronic sleep problems, his tendency to remain hyper-compliant, especially with his father, and to remain childlike in adulthood are consistent with the effects of the maltreatment he endured as a child.[31]

In 1964, Michael and Marlon joined the Jackson Brothers—a band formed by their father which included brothers Jackie, Tito, and Jermaine—as backup musicians playing congas and tambourine.[32] In 1965, Michael began sharing lead vocals with his older brother Jermaine, and the group's name was changed to the Jackson 5.[18] The following year, the group won a major local talent show with Jackson performing the dance to Robert Parker's 1965 hit "Barefootin'" and singing lead to The Temptations' "My Girl".[33] From 1966 to 1968 they toured the Midwest, frequently performing at a string of black clubs known as the "chitlin' circuit" as the opening act for artists such as Sam & Dave, the O'Jays, Gladys Knight, and Etta James. The Jackson 5 also performed at clubs and cocktail lounges, where striptease shows were featured, and at local auditoriums and high school dances.[34][35] In August 1967, while touring the East Coast, the group won a weekly amateur night concert at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.[36]

The Jackson 5 recorded several songs, including their first single "Big Boy" (1968), for Steeltown Records, a Gary record label,[37] then signed with Motown in 1969.[18] They left Gary in 1969 and relocated to Los Angeles, where they continued to record for Motown.[38] Rolling Stone later described the young Michael as "a prodigy" with "overwhelming musical gifts" who "quickly emerged as the main draw and lead singer."[39] The group set a chart record when its first four singles—"I Want You Back" (1969), "ABC" (1970), "The Love You Save" (1970), and "I'll Be There" (1970)—peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100.[18] In May 1971, the Jackson family moved into a large home on a two-acre estate in Encino, California.[40] During this period, Michael evolved from child performer into a teen idol.[41] As he began to emerge as a solo performer in the early 1970s, he maintained ties to the Jackson 5 and Motown. Between 1972 and 1975, Michael released four solo studio albums with Motown: Got to Be There (1972), Ben (1972), Music & Me (1973), and Forever, Michael (1975).[42] "Got to Be There" and "Ben", the title tracks from his first two solo albums, became successful singles, as did a cover of Bobby Day's "Rockin' Robin".[43]

The Jackson 5 were later described as "a cutting-edge example of black crossover artists".[44] Their sales began to decline in 1973, and the members chafed under Motown's refusal to allow them creative input, but they achieved several top 40 hits, including the top five single "Dancing Machine" (1974), before leaving Motown in 1975.[45] Jackson's performance of "Dancing Machine" on an episode of Soul Train popularized the robot dance.[46]

1975–1981: Move to Epic and Off the Wall

In June 1975, the Jackson 5 signed with Epic Records, a subsidiary of CBS Records,[45] and renamed themselves the Jacksons. Younger brother Randy formally joined the band around this time; Jermaine chose to stay with Motown and pursue a solo career.[47] The Jacksons continued to tour internationally, and released six more albums between 1976 and 1984. Michael, the group's lead songwriter during this time, wrote hits such as "Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground)" (1979), "This Place Hotel" (1980), and "Can You Feel It" (1980).[32]

In 1978, Jackson moved to New York City to star as the Scarecrow in The Wiz, a musical directed by Sidney Lumet. It costarred Diana Ross, Nipsey Russell, and Ted Ross.[48] The film was a box-office failure.[49] Its score was arranged by Quincy Jones, whom Jackson had previously met when he was 12 at Sammy Davis Jr.'s house.[50] Jones agreed to produce Jackson's next solo album.[51] During his time in New York, Jackson frequented the Studio 54 nightclub and was exposed to early hip hop, influencing his beatboxing on future tracks such as "Working Day and Night".[52] In 1979, Jackson broke his nose during a complex dance routine. A rhinoplasty was not a complete success; he complained of breathing difficulties that later affected his career. He was referred to Steven Hoefflin, who performed Jackson's subsequent operations.[53]

Jackson's fifth solo album, Off the Wall (1979), co-produced by Jackson and Jones, established him as a solo performer. The album helped Jackson move from the bubblegum pop of his youth to the more complex sounds he created as an adult.[41] Songwriters for the album included Jackson, Rod Temperton, Stevie Wonder, and Paul McCartney. Off the Wall was the first solo album to generate four top 10 hits in the US: "Off the Wall", "She's Out of My Life", and the chart-topping singles "Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough" and "Rock with You".[54][55] The album reached number three on the Billboard 200 and sold over 20 million copies worldwide.[56] In 1980, Jackson won three awards at the American Music Awards for his solo work: Favorite Soul/R&B Album, Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist, and Favorite Soul/R&B Single for "Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough".[57][58] He also won Billboard Year-End awards for Top Black Artist and Top Black Album, and a Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance for 1979 with "Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough".[59] In 1981 Jackson was the American Music Awards winner for Favorite Soul/R&B Album and Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist.[60] Despite its commercial success, Jackson felt Off the Wall should have made a bigger impact, and was determined to exceed expectations with his next release.[61] In 1980, he secured the highest royalty rate in the music industry: 37 percent of wholesale album profit.[62]

Jackson recorded with Queen singer Freddie Mercury from 1981 to 1983, recording demos of "State of Shock", "Victory" and "There Must Be More to Life Than This".[63] The recordings were intended for an album of duets but, according to Queen's then-manager Jim Beach, the relationship soured when Jackson insisted on bringing a llama into the recording studio,[64] and Jackson was upset by Mercury's drug use.[65] The collaborations were released in 2014.[66] Jackson went on to record "State of Shock" with Mick Jagger for the Jacksons' album Victory (1984),[67] and Mercury included the solo version of "There Must Be More To Life Than This" on his album Mr. Bad Guy (1985).[68] In 1982, Jackson combined his interests in songwriting and film when he contributed "Someone in the Dark" to the storybook for the film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. The song, produced by Jones, won a Grammy for Best Recording for Children for 1983.[69]

1982–1983: Thriller and Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever

Jackson's sixth album, Thriller, was released in late 1982. It earned Jackson seven more Grammys[69] and eight American Music Awards, and he became the youngest artist to win the Award of Merit.[70] It was the best-selling album worldwide in 1983,[71][72] and became the best-selling album of all time in the US[73] and the best-selling album of all time worldwide, selling an estimated 66 million copies.[74] It topped the Billboard 200 chart for 37 weeks and was in the top 10 of the 200 for 80 consecutive weeks. It was the first album to have seven Billboard Hot 100 top 10 singles, including "Billie Jean", "Beat It", and "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'".[75] In December 2015, Thriller was certified for 30 million shipments by the RIAA, one of only two albums to do so in the U.S.[5] Thriller won Jackson and Quincy Jones the Grammy award for Producer of the Year (Non-Classical) for 1983. It also won Album of the Year, with Jackson as the album's artist and Jones as its co-producer, and a Best Pop Vocal Performance, Male, award for Jackson. "Beat It" won Record of the Year, with Jackson as artist and Jones as co-producer, and a Best Rock Vocal Performance, Male, award for Jackson. "Billie Jean" won Jackson two Grammy awards, Best R&B Song, with Jackson as its songwriter, and Best R&B Vocal Performance, Male, as its artist.[69] Thriller also won another Grammy for Best Engineered Recording – Non Classical in 1984, awarding Bruce Swedien for his work on the album.[76] The AMA Awards for 1984 gave Jackson an Award of Merit and AMAs for Favorite Male Artist, Soul/R&B, and Favorite Male Artist, Pop/Rock. "Beat It" won Jackson AMAs for Favorite Video, Soul/R&B, Favorite Video, Pop/Rock, and Favorite Single, Pop/Rock. Thriller won him AMAs for Favorite Album, Soul/R&B, and Favorite Album, Pop/Rock.[70][77]

Jackson released "Thriller", a 14-minute music video directed by John Landis, in 1983.[78] The zombie-themed video "defined music videos and broke racial barriers" on MTV, a fledgling entertainment television channel at the time.[41] In December 2009, the Library of Congress selected the "Thriller" music video to be preserved in the National Film Registry as a work of "enduring importance to American culture", the only music video to have been inducted into the registry.[79][80][78][81]

Jackson had the highest royalty rate in the music industry at that point, about $2 for every album sold, and was making record-breaking profits. The videocassette of the documentary The Making of Michael Jackson's Thriller sold over 350,000 copies in a few months. Dolls modeled after Jackson appeared in stores in May 1984 for $12 each.[82] J. Randy Taraborrelli writes that "Thriller stopped selling like a leisure item—like a magazine, a toy, tickets to a hit movie—and started selling like a household staple."[83] In 1985, The Making of Michael Jackson's Thriller won a Grammy for Best Music Video, Longform.[69] Time described Jackson's influence at that point as "star of records, radio, rock video. A one-man rescue team for the music business. A songwriter who sets the beat for a decade. A dancer with the fanciest feet on the street. A singer who cuts across all boundaries of taste and style and color too".[82] The New York Times wrote that "in the world of pop music, there is Michael Jackson and there is everybody else".[84]

On March 25, 1983, Jackson reunited with his brothers for a performance at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium for Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever, an NBC television special. The show aired on May 16, 1983, to an estimated audience of 47 million, and featured the Jacksons and other Motown stars.[85] Jackson's solo performance of "Billie Jean" earned him his first Emmy nomination.[86] Wearing a black-sequined jacket and a golf glove decorated with rhinestones, he debuted his signature dance move, the moonwalk, which Jeffrey Daniel had taught him three years earlier.[87] Jackson had originally turned down the invitation to perform at the show, believing he had been doing too much television; at the request of Motown founder Berry Gordy, he agreed to perform in exchange for time to do a solo performance.[88] Rolling Stone reporter Mikal Gilmore called the performance "extraordinary".[41] Jackson's performance drew comparisons to Elvis Presley's and the Beatles' appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show.[89] Anna Kisselgoff of The New York Times wrote in 1988: "The moonwalk that he made famous is an apt metaphor for his dance style. How does he do it? As a technician, he is a great illusionist, a genuine mime. His ability to keep one leg straight as he glides while the other bends and seems to walk requires perfect timing."[90] Gordy described being "mesmerized" by the performance.[91]

1984–1985: Pepsi, "We Are the World", and business career

In November 1983, Jackson and his brothers partnered with PepsiCo in a $5 million promotional deal that broke records for a celebrity endorsement. The first Pepsi campaign, which ran in the US from 1983 to 1984 and launched its "New Generation" theme, included tour sponsorship, public relations events, and in-store displays. Jackson helped to create the advertisement, and suggested using his song "Billie Jean" as its jingle with revised lyrics.[92] Brian J. Murphy, executive VP of branded management at TBA Global, said: "You couldn't separate the tour from the endorsement from the licensing of the music, and then the integration of the music into the Pepsi fabric."[92]

On January 27, 1984, Michael and other members of the Jacksons filmed a Pepsi commercial overseen by Phil Dusenberry,[93] a BBDO ad agency executive, and Alan Pottasch, Pepsi's Worldwide Creative Director, at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. During a simulated concert before a full house of fans, pyrotechnics accidentally set Jackson's hair on fire, causing second-degree burns to his scalp. Jackson underwent treatment to hide the scars and had his third rhinoplasty shortly thereafter.[53] Pepsi settled out of court, and Jackson donated the $1.5 million settlement to the Brotman Medical Center in Culver City, California; its Michael Jackson Burn Center is named in his honor.[94] Dusenberry recounted the episode in his memoir, Then We Set His Hair on Fire: Insights and Accidents from a Hall of Fame Career in Advertising. Jackson signed a second agreement with Pepsi in the late 1980s for $10 million. The second campaign had a global reach of more than 20 countries and provided financial support for Jackson's Bad album and 1987–88 world tour.[92] Jackson had endorsements and advertising deals with other companies, such as LA Gear, Suzuki, and Sony, but none were as significant as his deals with Pepsi, which later signed Britney Spears and Beyoncé to promote its products.[92][95]

On May 14, 1984, Jackson was invited to the White House to receive an award from President Ronald Reagan for his support of charities that helped people overcome alcohol and drug abuse,[96] and in recognition of his support for the Ad Council's and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Drunk Driving Prevention campaign. Jackson donated the use of "Beat It" for the campaign's public service announcements.[97]

The Victory Tour of 1984 headlined the Jacksons and showcased Jackson's new solo material to more than two million Americans. It was the last tour he did with his brothers.[98] Following controversy over the concert's ticket sales, Jackson held a press conference and announced that he would donate his share of the proceeds, an estimated $3 to 5 million, to charity.[99] His charitable work continued with the release of "We Are the World" (1985), co-written with Lionel Richie,[100] which raised money for the poor in the US and Africa.[101] It earned $63 million,[101] and became one of the best-selling singles of all time, with 20 million copies sold.[102] It won four Grammys for 1985, including Song of the Year for Jackson and Richie as its writers.[100] The American Music Awards directors removed the charity song from the competition because they felt it would be inappropriate, but the AMA show in 1986 concluded with a tribute to the song on its first anniversary. The project's creators received two special AMA honors: one for the creation of the song and another for the USA for Africa idea. Jackson, Jones, and entertainment promoter Ken Kragan received special awards for their roles in the song's creation.[100][103][104][105]

Jackson collaborated with Paul McCartney in the early 1980s, and learned that McCartney was making $40 million a year from owning the rights to other people's songs.[101] By 1983, Jackson had begun buying publishing rights to others' songs, but he was careful with his acquisitions, only bidding on a few of the dozens that were offered to him. Jackson's early acquisitions of music catalogs and song copyrights such as the Sly Stone collection included "Everyday People" (1968), Len Barry's "1-2-3" (1965), and Dion DiMucci's "The Wanderer" (1961) and "Runaround Sue" (1961).

In 1984 Robert Holmes à Court, the Australian investor who owned ATV Music Publishing, announced he was putting the ATV catalog up for sale.[106] ATV owned the publishing rights to nearly 4000 songs, among them the Northern Songs catalog that included the majority of the Lennon–McCartney compositions recorded by the Beatles.[106] In 1981, McCartney had been offered the ATV music catalog for £20 million ($40 million).[101][107][108] When he and McCartney were unable to make a joint purchase, McCartney, who did not want to be the sole owner of the Beatles' songs, did not pursue an offer on his own.[107][108] Jackson submitted a bid of $46 million on November 20, 1984.[106] His agents thought they had a deal several times, but encountered new bidders or new areas of debate. In May 1985, Jackson's team left talks after having spent more than $1 million and four months of due diligence work on the negotiations.[106] In June 1985, Jackson and Branca learned that Charles Koppelman's and Marty Bandier's The Entertainment Company had made a tentative offer to buy ATV Music for $50 million; in early August, Holmes à Court's team contacted Jackson and talks resumed. Jackson raised his bid to $47.5 million, which was accepted because he could close the deal more quickly, having already completed due diligence.[106] Jackson also agreed to visit Holmes à Court in Australia, where he would appear on the Channel Seven Perth Telethon.[109] Jackson's purchase of ATV Music was finalized on August 10, 1985.[106][101]

1986–1990: Changing appearance, tabloids, Bad, films, autobiography, and Neverland

Jackson's skin had been a medium-brown color during his youth, but from the mid-1980s gradually grew paler. The change gained widespread media coverage, including rumors that he might have been bleaching his skin.[110][111][112] According to J. Randy Taraborrelli's biography, in 1984 Jackson was diagnosed with vitiligo, which causes white patches on the skin. Taraborrelli stated that Jackson had also been skin bleaching. He said that Jackson was diagnosed with lupus, which was in remission. Both illnesses made Jackson's skin sensitive to sunlight. The treatments Jackson used for his condition further lightened his skin, and, with the application of pancake makeup to even out blotches he could appear even paler.[113] Jackson stated that he used makeup to control the patchy appearance of his skin, but never purposely bleached his skin. He said of his vitiligo: "It is something I cannot help. When people make up stories that I don't want to be who I am, it hurts me. It's a problem for me. I can't control it."[114] Jackson was also diagnosed with vitiligo in his autopsy, though not lupus.[115]

Jackson stated he had had only two rhinoplasties and no other facial surgery, but mentioned having had a dimple created in his chin. He lost weight in the early 1980s because of a change in diet and a desire for "a dancer's body".[116] Witnesses reported that he was often dizzy, and speculated he was suffering from anorexia nervosa. Periods of weight loss would become a recurring problem later in life.[117] During the course of his treatment, Jackson made two close friends: his dermatologist, Arnold Klein, and Klein's nurse Debbie Rowe. Rowe later became Jackson's second wife and the mother of his two eldest children. He also relied heavily on Klein for medical and business advice.[118]

Why not just tell people I'm an alien from Mars? Tell them I eat live chickens and do a voodoo dance at midnight. They'll believe anything you say, because you're a reporter. But if I, Michael Jackson, were to say, "I'm an alien from Mars and I eat live chickens and do a voodoo dance at midnight," people would say, "Oh, man, that Michael Jackson is nuts. He's cracked up. You can't believe a single word that comes out of his mouth."

—Jackson to his biographer[119]

In 1986, the tabloids ran a story claiming that he slept in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber to slow aging, and was pictured lying in a glass box. The claim was untrue; widely cited tabloid reports state that Jackson disseminated the fabricated story himself.[120] When Jackson bought a chimpanzee named Bubbles from a laboratory, he was reported as increasingly detached from reality.[121] It was reported that Jackson had offered to buy the bones of Joseph Merrick (the "Elephant Man") and, although the story was untrue, Jackson did not deny it.[122] He initially saw these stories as opportunities for publicity, but stopped leaking them to the press as they became more sensational. The media then began fabricating stories.[120][123][124] These stories became embedded in the public consciousness, inspiring the nickname "Wacko Jacko", which Jackson came to despise.[9][125]

Jackson collaborated with filmmakers George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola on the 17-minute 3D film Captain EO, which debuted in September 1986 at the original Disneyland and at Epcot in Florida, and in March 1987 at Tokyo Disneyland. The $30 million film was a popular attraction at all three parks. A Captain EO attraction also featured at Euro Disneyland after the park opened in 1992, and was the last to close, in 1998.[126] The attraction returned to Disneyland in 2010 after Jackson's death.[127] In 1987, Jackson disassociated himself from the Jehovah's Witnesses.[128] Katherine Jackson said this might have been because some Witnesses strongly opposed the Thriller video;[129] Jackson had denounced it in a Witness publication in 1984.[130]

Jackson's first album in five years, Bad (1987), was highly anticipated, with the industry expecting another major hit.[131] It produced nine singles, with seven charting in the US Five ("I Just Can't Stop Loving You", "Bad", "The Way You Make Me Feel", "Man in the Mirror", and "Dirty Diana") reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100, a record for the most number-one Hot 100 singles from a single album.[132] It won the 1988 Grammy for Best Engineered Recording – Non Classical and the 1989 Grammy for Best Music Video, Short Form for "Leave Me Alone".[69][76] Jackson won an Award of Achievement at the American Music Awards in 1989 after Bad became the first album to generate five number-one singles in the US, the first album to top in 25 countries, and the best-selling album worldwide in 1987 and 1988.[133][134][135][136] By 2012, it had sold between 30 and 45 million copies worldwide.[137][138][139][140]

The Bad world tour began on September 12, 1988, finishing on January 14, 1989.[141] Jackson performed a total of 123 concerts to an audience of 4.4 million people.[142] In Japan alone, the tour had 14 sellouts and drew 570,000 people, nearly tripling the previous record of 200,000 in a single tour.[143] 504,000 people attended seven sold-out shows at Wembley Stadium, setting a new Guinness world record.[144]

In 1988, Jackson released his autobiography, Moonwalk, which took four years to complete. It sold 200,000 copies[145] and reached the top of the New York Times bestsellers list.[146] He wrote about his childhood, the abuse from his father, and the Jackson 5;[147] he also wrote about changing facial appearance, attributing it to puberty, weight loss, a strict vegetarian diet, a change in hairstyle, and stage lighting.[116] Jackson released a film, Moonwalker, which featured live footage and short films starring Jackson and Joe Pesci. Due to financial problems, the film was only released theatrically in Germany; in other markets it was released direct-to-video. It debuted at the top of the Billboard Top Music Video Cassette chart, and stayed there for 22 weeks, until it was displaced by Michael Jackson: The Legend Continues.[148]

In March 1988, Jackson purchased 2,700 acres (11 km2) of land near Santa Ynez, California, to build a new home, Neverland Ranch, at a cost of $17 million.[149] He installed several carnival rides, including a Ferris wheel, carousel, menagerie, movie theater and zoo.[149][150][151] A security staff of 40 patrolled the grounds.[150] In 2003, it was valued at $100 million.[152] In 1989, Jackson's annual earnings from album sales, endorsements, and concerts were estimated at $125 million for that year alone.[153] Shortly afterwards, he became the first Westerner to appear in a television advertisement in the Soviet Union.[148]

Jackson's success earned him the nickname the "King of Pop".[154][10][155] It was popularized by Elizabeth Taylor when she presented him with the Soul Train Heritage Award in 1989, proclaiming him "the true king of pop, rock and soul,"[156] and the release of the "Black or White" video.[157] President George H. W. Bush designated him the White House's "Artist of the Decade".[158] From 1985 to 1990, Jackson donated $455,000 to the United Negro College Fund,[159] and all profits from his single "Man in the Mirror" went to charity.[160] His rendition of "You Were There" at Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th birthday celebration won Jackson a second Emmy nomination.[86][148]

1991–1993: Dangerous, Heal the World Foundation, and Super Bowl XXVII

In March 1991, Jackson renewed his contract with Sony for $65 million, a record-breaking deal,[161] displacing Neil Diamond's renewal contract with Columbia Records.[162] In 1991, he released his eighth album, Dangerous, co-produced with Teddy Riley.[163] Dangerous was certified seven times platinum in the US, and by 2008 had sold 30 million copies worldwide.[164][165] In the US, the first single, "Black or White", was the album's biggest hit, reaching number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and remaining there for seven weeks, with similar chart performances worldwide.[166] The second single, "Remember the Time", spent eight weeks in the top five in the US, peaking at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.[167] At the end of 1992, Dangerous was awarded the best-selling album of the year worldwide and "Black or White" was awarded best-selling single of the year worldwide at the Billboard Music Awards. Jackson also won an award as best-selling artist of the 1980s.[168] In 1993, he performed the song at the Soul Train Music Awards in a chair, saying he had suffered an injury in rehearsals.[169] In the UK and other parts of Europe, "Heal the World" was the album's most successful song; it sold 450,000 copies in the UK and spent five weeks at number two in 1992.[167]

Jackson founded the Heal the World Foundation in 1992. The charity brought underprivileged children to Jackson's ranch to use the property's theme park rides, and sent millions of dollars around the globe to help children threatened by war, poverty, and disease. In the same year, Jackson published his second book, Dancing the Dream, a collection of poetry. The Dangerous World Tour began on June 27, 1992, and finished on November 11, 1993, having grossed $100 million; Jackson performed to 3.5 million people in 70 concerts.[167][170] He sold the broadcast rights to the tour to HBO for $20 million, a record-breaking deal that still stands.[171]

Following the death of AIDS spokesperson Ryan White, Jackson helped draw public attention to HIV/AIDS, something that was controversial at the time. He pleaded with the Clinton administration at Bill Clinton's inaugural gala to give more money to HIV/AIDS charities and research.[172][173] Jackson visited Africa; on his first stop in Gabon he was greeted by more than 100,000 people, some of them carrying signs that read "Welcome Home Michael."[174] During his trip to Ivory Coast, Jackson was crowned "King Sani" by a tribal chief.[174] He thanked the dignitaries in French and English, signed official documents formalizing his kingship, and sat on a golden throne while presiding over ceremonial dances.[174]

In January 1993, Jackson performed at the Super Bowl XXVII halftime show in Pasadena, California. Because of a dwindling interest during halftime in the preceding years, the NFL decided to seek big-name talent that would keep ratings high.[175][176] It was the first Super Bowl whose half-time performance drew greater audience figures than the game itself. The performance began with Jackson catapulting onto the stage as fireworks went off behind him, followed by four songs: "Jam", "Billie Jean", "Black or White", and "Heal the World". Jackson's Dangerous album rose 90 places in the album chart after the performance.[110]

Jackson gave a 90-minute interview to Oprah Winfrey on February 10, 1993, his second television interview since 1979. He grimaced when speaking of his childhood abuse at the hands of his father; he believed he had missed out on much of his childhood, and said that he often cried from loneliness. He denied tabloid rumors that he had bought the bones of the Elephant Man, slept in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, or bleached his skin, and stated for the first time that he had vitiligo. Dangerous re-entered the album chart in the top 10, more than a year after its original release.[25][110][167]

In February 1993, Jackson was given the "Living Legend Award" at the 35th Annual Grammy Awards in Los Angeles. "Black or White" was Grammy-nominated for best vocal performance. "Jam" gained two nominations: Best R&B Vocal Performance and Best R&B Song.[167] The Dangerous album won a Grammy for Best Engineered – Non Classical, awarding the work of Bruce Swedien and Teddy Riley.[76] In the same year, Jackson won three American Music Awards for Favorite Pop/Rock Album (Dangerous), Favorite Soul/R&B Single ("Remember the Time"), and was the first to win the International Artist Award of Excellence, for his global performances and humanitarian concerns.[177][178]

1993–1994: First child sexual abuse allegations and first marriage

In mid-1993, Jackson was accused of child sexual abuse by a 13-year-old boy, Jordan Chandler, and his father, Evan Chandler.[179][180][181] Jackson began taking painkillers, Valium, Xanax and Ativan to deal with the stress of the allegations. By late 1993, he was addicted to the drugs.[182] The Chandler family demanded payment from Jackson, which he refused. Jordan Chandler told the police that Jackson had sexually abused him;[122][183] Jordan's mother said that there had been no wrongdoing on Jackson's part.[181] Evan was recorded discussing his intention to pursue charges[181] and Jackson used the recording to argue that he was the victim of a jealous father trying to extort money.[181] In January 1994, after an investigation, deputy Los Angeles County district attorney Michael J. Montagna stated that Chandler would not be charged with extortion, due to lack of cooperation from Jackson's party and its willingness to negotiate with Chandler for several weeks, among other reasons.[184]

In August 1993, police raided Jackson's home and found books and photographs in his bedroom featuring young boys with little or no clothing.[185] The books were legal to purchase and own in the US, and Jackson was not indicted.[186] Jordan Chandler gave police a description of Jackson's intimate parts; a strip search revealed that Jordan had correctly claimed Jackson had patchy-colored buttocks, short pubic hair, and pink and brown marked testicles.[187] He also drew accurate pictures of a dark spot on Jackson's penis only visible when it was lifted.[188] Some jurors felt that the photos did not match the description,[189] but the DA and the sheriff's photographer stated that the description was accurate.[190]

The investigation was inconclusive and no charges were filed.[189] Jackson described the search in an emotional public statement, and proclaimed his innocence.[179][187][191] On January 1, 1994, Jackson settled with the Chandlers out of court for an undisclosed amount.[192] A Santa Barbara County grand jury and a Los Angeles County grand jury disbanded on May 2, 1994, without indicting Jackson.[193] The Chandlers stopped co-operating with the criminal investigation around July 6, 1994.[194][195][196]

In 2004 Jackson's defense said that Jackson had never been criminally indicted, his settlement admitted no wrongdoing or evidence of criminal misconduct, and that the 1994 settlement was made without his consent.[194] A later disclosure by the FBI of investigation documents compiled over nearly 20 years led Jackson's attorney to suggest that no evidence of molestation or sexual impropriety from Jackson toward minors existed.[197] The Department of Children and Family Services (Los Angeles County) investigated Jackson beginning in 1993 with the Chandler allegation and again in 2003. The LAPD and DCFS did not find credible evidence of abuse or sexual misconduct.[198][199]

In May 1994, Jackson married Lisa Marie Presley, the daughter of Elvis and Priscilla Presley. They had met in 1975, when a seven-year-old Presley attended one of Jackson's family engagements at the MGM Grand Hotel and Casino, and reconnected through a mutual friend.[200] A friend of Presley's said they first met as adults in November 1992.[201] They stayed in contact every day over the telephone. As the child molestation accusations became public, Jackson became dependent on Presley for emotional support; she was concerned about his faltering health and addiction to drugs.[182] Presley said: "I believed he didn't do anything wrong and that he was wrongly accused and yes I started falling for him. I wanted to save him. I felt that I could do it."[202] Shortly afterward, she tried to persuade Jackson to settle the allegations out of court and go into rehabilitation to recover—he subsequently did both.[182]

Jackson proposed to Presley over the telephone in late 1993, saying: "If I asked you to marry me, would you do it?"[182] They married in the Dominican Republic in secrecy, denying it for nearly two months afterwards.[203] The marriage was, in her words, "a married couple's life ... that was sexually active."[204] The tabloid media speculated that the wedding was a ploy to prop up Jackson's public image.[203] The marriage ended less than two years later with an amicable divorce settlement.[205] In a 2010 interview with Oprah Winfrey, Presley said they had spent four more years after the divorce "getting back together and breaking up" until she decided to stop.[206]

1995–1997: HIStory, second marriage, and fatherhood

In June 1995, Jackson released the double album HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I. The first disc, HIStory Begins, is a greatest hits album (reissued in 2001 as Greatest Hits: HIStory, Volume I). The second disc, HIStory Continues, contains 13 original songs and two cover versions. The album debuted at number one on the charts and has been certified for seven million shipments in the US.[207] It is the best-selling multi-disc album of all time, with 20 million copies (40 million units) sold worldwide.[166][208] HIStory received a Grammy nomination for Album of the Year.[209]

The first single released from HIStory was "Scream/Childhood". "Scream", a duet with Jackson's youngest sister Janet, protests the media, particularly its treatment of Jackson during the 1993 child abuse allegations. The single had the highest debut on the Billboard Hot 100 at number five, and received a Grammy nomination for "Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals".[209] The second single, "You Are Not Alone", holds the Guinness world record for the first song to debut at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[153] It was seen as a major artistic and commercial success, receiving a Grammy nomination for "Best Pop Vocal Performance".[209]

In late 1995, Jackson was rushed to a hospital after collapsing during rehearsals for a televised performance, caused by a stress-related panic attack.[210] In November, Jackson merged his ATV Music catalog with Sony's music publishing division, creating Sony/ATV Music Publishing. He retained ownership of half the company, earning $95 million up front as well as the rights to more songs.[211][212] "Earth Song" was the third single released from HIStory, and topped the UK Singles Chart for six weeks over Christmas 1995; it sold a million copies, making it Jackson's most successful single in the UK.[209] The track "They Don't Care About Us" became controversial when the Anti-Defamation League and other groups criticized its allegedly antisemitic lyrics. Jackson quickly released a revised version of the song without the offending lyrics.[213] In 1996, Jackson won a Grammy for Best Music Video, Short Form for "Scream" and an American Music Award for Favorite Pop/Rock Male Artist.[69][214]

HIStory was promoted with the HIStory World Tour, beginning on September 7, 1996, and ending on October 15, 1997. Jackson performed 82 concerts in five continents, 35 countries and 58 cities to over 4.5 million fans, and grossed a total of $165 million, becoming Jackson's most attended tour.[141] During the tour, Jackson married Debbie Rowe, a dermatology nurse, in an impromptu ceremony in Sydney, Australia. Rowe was six months pregnant with the couple's first child at the time. Originally, Rowe and Jackson had no plans to marry, but Jackson's mother Katherine persuaded them to do so.[215] Michael Joseph Jackson Jr. (commonly known as Prince) was born on February 13, 1997; his sister Paris-Michael Katherine Jackson was born a year later on April 3, 1998.[205][216] The couple divorced in 1999, and Jackson received full custody of the children. The subsequent custody suit was settled in 2006.[217][218]

In 1997, Jackson released Blood on the Dance Floor: HIStory in the Mix, which contained remixes of hit singles from HIStory and five new songs. Worldwide sales stand at 6 million copies, making it the best-selling remix album of all time.[219] It reached number one in the UK, as did the title track.[219][220] In the US, the album was certified platinum, but only reached number 24.[164][209] Forbes placed Jackson's annual income at $35 million in 1996 and $20 million in 1997.[152]

1997–2002: Label dispute and Invincible

From October 1997 to September 2001, Jackson worked on his tenth solo album, Invincible. The album cost $30 million to record, not including promotional expenditures.[221] In June 1999, Jackson joined Luciano Pavarotti for a War Child benefit concert in Modena, Italy. The show raised a million dollars for the refugees of Kosovo, FR Yugoslavia, and additional funds for the children of Guatemala.[222] Later that month, Jackson organized a series of "Michael Jackson & Friends" benefit concerts in Germany and Korea. Other artists involved included Slash, The Scorpions, Boyz II Men, Luther Vandross, Mariah Carey, A. R. Rahman, Prabhu Deva Sundaram, Shobana, Andrea Bocelli, and Luciano Pavarotti. The proceeds went to the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, the Red Cross and UNESCO.[223] From August 1999 to 2000, he lived in New York City at 4 East 74th Street.[224] At the turn of the century, Jackson won an American Music Award as Artist of the 1980s.[225] In 2000, Guinness World Records recognized him for supporting 39 charities, more than any other entertainer.[226]

In September 2001, two 30th Anniversary concerts were held at Madison Square Garden to mark Jackson's 30th year as a solo artist. Jackson appeared onstage alongside his brothers for the first time since 1984. The show also featured performances by artists including Mýa, Usher, Whitney Houston, NSYNC, Destiny's Child, Monica, Luther Vandross, and Slash.[227] After 9/11, Jackson helped organize the United We Stand: What More Can I Give benefit concert at RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. on October 21, 2001. Jackson performed "What More Can I Give" as the finale.[228]

The release of Invincible was preceded by a dispute between Jackson and his record label, Sony Music Entertainment. Jackson had expected the licenses to the masters of his albums to revert to him some time in the early 2000s, after which he would be able to promote the material however he pleased and keep the profits; clauses in the contract set the revert date years into the future. Jackson discovered that the attorney who had represented him in the deal had also been representing Sony.[220] Sony had been pressuring him to sell his share in its music catalog venture, and he feared that Sony might have had a conflict of interest, since if Jackson's career failed, he would have had to sell his share of the catalog at a low price.[228] Jackson sought an early exit from his contract.[220]

Invincible was released on October 30, 2001. It was Jackson's first full-length album in six years, and the last album of original material he released in his lifetime.[220] It debuted at number one in 13 countries and went on to sell 6 million copies worldwide, receiving double-platinum certification in the US.[164][166] Sales for Invincible were lower than Jackson's previous releases, due in part to the record label dispute and the lack of promotion or tour, and its release at a bad time[229] for the music industry in general.[228] Invincible spawned three singles, "You Rock My World", "Cry", and "Butterflies", the latter without a music video.

On January 22, 2002, Jackson won his 22nd American Music Award for Artist of the Century.[230] In the same year, his third child, Prince Michael Jackson II (nicknamed "Blanket") was born. The mother's identity was not announced, but Jackson said Prince was the result of artificial insemination from a surrogate mother and his own sperm.[217] Jackson alleged in July 2002 that Sony Music chairman Tommy Mottola was a "devil" and "racist" who did not support his African-American artists, using them merely for his own gain.[228] He charged that Mottola had called his colleague Irv Gotti a "fat nigger".[231] Sony refused to renew Jackson's contract, and claimed that a $25 million promotional campaign had failed because Jackson refused to tour in the US.[221]

2002–2005: Second child sexual abuse allegations and acquittal

Beginning in May 2002, Jackson allowed a documentary film crew, led by British journalist Martin Bashir, to follow him nearly everywhere he went. On November 20, Jackson brought his infant son Prince onto the balcony of his room at the Hotel Adlon in Berlin as fans stood below, holding him in his right arm with a cloth loosely draped over Prince's face. He briefly held Prince out over a railing, four stories above ground level, prompting widespread criticism in the media. Jackson apologized for the incident, calling it "a terrible mistake".[232] Bashir's crew was with Jackson during this incident; the program was broadcast in March 2003 as Living with Michael Jackson. In one scene, Jackson was seen holding hands and discussing sleeping arrangements with a young boy.[233]

As soon as the documentary aired, the Santa Barbara county attorney's office began a criminal investigation. After the young boy involved in the documentary and his mother had told investigators that Jackson had behaved improperly, Jackson was arrested in November 2003 and charged with seven counts of child molestation and two counts of administering an intoxicating agent in relation to the 13-year-old boy shown in the film.[233] Jackson denied the allegations, saying the sleepovers were not sexual in nature. The People v. Jackson trial began on January 31, 2005, in Santa Maria, California, and lasted until the end of May. On June 13, 2005, Jackson was acquitted on all counts.[234][235][236] After the trial he moved to the Persian Gulf island of Bahrain as a guest of Sheikh Abdullah.[237] Jermaine Jackson later said the family had planned to send him there had he been convicted.[238]

On November 17, 2003, three days before Jackson's arrest, Sony released Number Ones, a compilation of Jackson's hits on CD and DVD. In the US, the album was certified triple platinum by the RIAA; in the UK it was certified six times platinum for shipments of at least 1.2 million units.[164][239]

2006–2009: Closure of Neverland, final years, and This Is It

In March 2006, amidst reports that Jackson was having financial problems, the main house at Neverland Ranch was closed as a cost-cutting measure.[240] Jackson had failed to make repayments of a $270 million loan secured against his music publishing holdings, which were making him $75 million a year.[241] Bank of America sold the debt to Fortress Investments. Sony proposed a restructuring deal which would give them a future option to buy half of Jackson's stake in their jointly-owned publishing company, leaving Jackson with a 25% stake.[212] Jackson agreed to a Sony-backed refinancing deal in April 2006; the details were not made public.[242]

Throughout 2006, Sony repackaged 20 singles from the 1980s and 1990s as the Michael Jackson: Visionary series, which later became a box set. Most of the singles returned to the charts as a result. In 2006, Jackson and his ex-wife Debbie Rowe settled their long-running child custody suit. Jackson retained custody of their two children.[218]

In early 2006, it was announced that Jackson had signed a contract with a Bahrain-based startup, Two Seas Records; nothing came of the deal, and Two Seas CEO Guy Holmes later stated that it had never been finalized.[243][244] That October, Fox News entertainment reporter Roger Friedman said that Jackson had been recording at a studio in rural County Westmeath, Ireland. It was not known at the time what Jackson was working on, or who had paid for the sessions, since his publicist had recently issued a statement claiming that he had left Two Seas.[244][245] In November 2006, Jackson invited an Access Hollywood camera crew into the studio in Westmeath, and MSNBC reported that he was working on a new album, produced by will.i.am.[166] Jackson performed at the World Music Awards in London on November 15, 2006, and accepted a Diamond Award for selling over 100 million records.[166][246] During his period in Ireland he sought Patrick Treacy for cosmetic treatment after reading about his experience with HLA fillers and his charitable work in Africa.[247] Treacy became his doctor when he lived in Ireland in 2006. He started as Jackson's personal dermatologist and developed a friendship with him.[248] Jackson returned to the US after Christmas 2006 to attend James Brown's funeral in Augusta, Georgia, where he gave one of the eulogies, saying that "James Brown is my greatest inspiration".[249]

In 2007, Jackson and Sony bought another music publishing company, Famous Music LLC, formerly owned by Viacom. This deal gave him the rights to songs by Eminem and Beck, among others.[250][251] In March 2007, Jackson gave a brief interview to the Associated Press in Tokyo, where he said: "I've been in the entertainment industry since I was 6 years old, and as Charles Dickens would say, 'It's been the best of times, the worst of times.' But I would not change my career ... While some have made deliberate attempts to hurt me, I take it in stride because I have a loving family, a strong faith and wonderful friends and fans who have, and continue, to support me."[252] That month, Jackson visited a US Army post in Japan, Camp Zama, to greet over 3,000 troops and their families. The hosts presented Jackson with a Certificate of Appreciation.[253][254]

In September 2007, Jackson was still working on his next album, but it was never completed.[255] In 2008, Jackson and Sony released Thriller 25 to mark the 25th anniversary of the original Thriller. The album featured the previously unreleased song "For All Time", an outtake from the original sessions, as well as remixes by younger artists who had been inspired by Jackson's work.[256] Two remixes were released as singles with modest success: "The Girl Is Mine 2008" (with will.i.am), based on an early demo version of the original song without Paul McCartney, and "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin' 2008" (with Akon).[256][257][258][259] In anticipation of Jackson's 50th birthday, Sony BMG released a series of greatest hits albums, King of Pop. Slightly different versions were released in various countries, based on polls of local fans.[260] King of Pop reached the top 10 in most countries where it was issued, and also sold well as an import in other countries, including the US.[261][262]

In late 2008, Fortress Investments threatened to foreclose on Neverland Ranch, which Jackson used as collateral for loans running into many tens of millions of dollars. Fortress opted to sell Jackson's debts to Colony Capital LLC. In November, Jackson transferred Neverland Ranch's title to Sycamore Valley Ranch Company LLC, a joint venture between Jackson and Colony Capital LLC. The deal cleared Jackson's debt and earned him an additional $35 million. At the time of his death, Jackson still owned a stake of unknown size in Neverland/Sycamore Valley.[263][264] In September 2008, Jackson entered negotiations with Julien's Auction House to display and auction a large collection of memorabilia in 1,390 lots. The auction was scheduled to take place between April 22 and 25.[265] An exhibition of the lots opened as scheduled on April 14, but Jackson cancelled the auction.[266]

In March 2009, Jackson held a press conference at London's O2 Arena to announce a series of comeback concerts titled This Is It. The shows were planned to be Jackson's first major series of concerts since the HIStory World Tour finished in 1997. Jackson suggested he would retire after the shows. The initial plan was for 10 concerts in London, followed by shows in Paris, New York City and Mumbai. Randy Phillips, president and chief executive of AEG Live, stated that the first 10 dates would earn Jackson £50 million.[267] The London residency was increased to 50 dates after record-breaking ticket sales: over one million were sold in less than two hours.[268] The concerts would have commenced on July 13, 2009, and finished on March 6, 2010. Jackson rehearsed in Los Angeles in the weeks leading up to the tour under the direction of choreographer Kenny Ortega. Most rehearsals took place at the Staples Center, owned by AEG.[269]

Death, memorial service, and aftermath

On June 25, 2009, less than three weeks before the first show was due to begin in London, with all concerts sold out, Jackson suffered cardiac arrest and died.[270] Conrad Murray, his personal physician, had given Jackson various medications in an attempt to help him sleep at his rented mansion in Holmby Hills, Los Angeles. Attempts at resuscitating Jackson were unsuccessful.[271][272] Los Angeles Fire Department paramedics received a 911 call at 12:22 pm (PDT, 19:22 UTC), arriving three minutes later.[273][274] Jackson was not breathing and CPR was performed.[275] Resuscitation efforts continued en route to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, and for more than an hour after arriving there at 1:13 pm (20:13 UTC). He was pronounced dead at 2:26 pm Pacific time (21:26 UTC).[276][277]

In August 2009, the Los Angeles County Coroner ruled that Jackson's death was a homicide.[278][279] Jackson had taken propofol, lorazepam, and midazolam;[280] his death was caused by acute propofol intoxication.[281]

Jackson's death triggered a global outpouring of grief.[272] The news spread quickly online, causing websites to slow down and crash from user overload,[282] and putting unprecedented strain[283] on services and websites including Google,[284] AOL Instant Messenger,[283] Twitter, and Wikipedia.[284] Overall, web traffic ranged from 11% to at least 20% higher than normal.[285][286] MTV and BET aired marathons of Jackson's music videos.[287] Jackson specials aired on television stations around the world.[288] MTV briefly returned to its original music video format,[289] airing hours of Jackson's music videos, accompanied by live news specials featuring reactions from MTV personalities and other celebrities.[290]

Memorial service

Jackson's memorial was held on July 7, 2009 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, preceded by a private family service at Forest Lawn Memorial Park's Hall of Liberty. Tickets to the memorial were distributed via lottery; over 1.6 million fans applied for tickets during the two-day application period. The final 8,750 recipients were drawn at random, and each recipient received two tickets.[291] The memorial service was one of the most watched events in streaming history,[292] with an estimated US audience of 31.1 million, a number comparable to the 35.1 million who watched the 2004 burial of former president Ronald Reagan and the 33.1 million Americans who watched the 1997 funeral for Princess Diana.[293]

Mariah Carey, Stevie Wonder, Lionel Richie, John Mayer, Jennifer Hudson, Usher, Jermaine Jackson, and Shaheen Jafargholi performed at the event. Berry Gordy and Smokey Robinson gave eulogies, while Queen Latifah read "We Had Him", a poem written for the occasion by Maya Angelou.[294] Al Sharpton received a standing ovation with cheers when he told Jackson's children, "Wasn't nothing strange about your daddy. It was strange what your daddy had to deal with. But he dealt with it anyway."[295] Jackson's 11-year-old daughter Paris Katherine, speaking publicly for the first time, wept as she addressed the crowd.[296][297] The Rev. Lucious Smith provided a closing prayer.[298] Jackson's body was entombed on September 3, 2009, at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.[299]

Criminal investigation and prosecution

Law enforcement officials investigated Jackson's personal physician, Conrad Murray, and charged him with involuntary manslaughter in Los Angeles on February 8, 2010.[300] The California Medical Board issued an order preventing Murray from administering heavy sedatives.[301] Murray's trial began on September 27, 2011;[302] on November 7, 2011, he was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter[303] and held without bail to await sentencing.[304] On November 29, 2011, Murray received the maximum sentence of four years in prison.[305] He was released on October 28, 2013[306] due to California prison overcrowding and good behavior.[307]

Aftermath

On June 25, 2010, the first anniversary of Jackson's death, fans, family and friends visited Jackson's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, his family home, and Forest Lawn Memorial Park. Many carried tributes to leave at the sites.[308][309] On June 26, fans marched in front of the Los Angeles Police Department's Robbery-Homicide Division at the old Parker Center building, and submitted a petition with thousands of signatures, demanding justice in the homicide investigation.[310][311] The Jackson Family Foundation and Voiceplate presented "Forever Michael", an event uniting Jackson family members, celebrities, fans, supporters and the community. A portion of the proceeds were presented to charity.[312][313][314]

In April 2011, billionaire businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed, chairman of Fulham Football Club, unveiled a statue of Jackson outside the club stadium, Craven Cottage.[315] Fulham fans failed to see the relevance of Jackson to the club;[316] Al-Fayed defended the statue and told the fans to "go to hell" if they did not appreciate it.[315] The statue was removed in September 2013[317] and moved to the National Football Museum in Manchester in May 2014.[318]

In 2012, in an attempt to end a family dispute, Jackson's brother Jermaine Jackson retracted his signature on a public letter criticizing executors of Michael Jackson's estate and his mother's advisers over the legitimacy of his brother's will.[319] T.J. Jackson, son of Tito Jackson, was given co-guardianship of Michael Jackson's children after false reports surfaced of Katherine Jackson going missing.[320]

Further sexual abuse allegations

In 2013, choreographer Wade Robson and James Safechuck filed a $1.5 billion-dollar civil lawsuit claiming Jackson had sexually abused them as children.[321] Both Robson and Safechuck had been friends with Michael Jackson, and both had been witnesses for the defence when Jackson was accused of child sexual abuse during his lifetime.[322] On May 16, 2013, Robson alleged on The Today Show that Jackson had abused him for seven years, beginning when Robson was seven years old.[323] Robson had previously testified in defense of Jackson in the 2005 trial.[324] On December 19, 2017, Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff dismissed the lawsuit because Robson had filed too late.[325] The documentary Leaving Neverland (2019) covers Jackson's alleged sexual abuse of Robson and Safechuck.[326] It was the first to cover the case in a detailed fashion from the point of view of the alleged victims.[327] The Jackson family condemned Leaving Neverland as a "public lynching" and insisted he was innocent.[328]

Posthumous releases

Following a surge in sales following Jackson's death, Sony extended its distribution rights for his music, which had been due to expire in 2015.[329] On March 16, 2010, Sony Music Entertainment, spearheaded by its Columbia/Epic Label Group division, signed a $250 million deal with the Jackson estate to extend their distribution rights to Jackson's back catalogue until at least 2017 and release ten new albums of previously unreleased material and new collections of released work.[330]

The first posthumous Jackson song, "This Is It", co-written in the 1980s with Paul Anka, was released in n October 2009. The surviving Jackson brothers reunited to record backing vocals.[331] On October 28, 2009, Sony released a documentary film about the rehearsals, Michael Jackson's This Is It.[332] Despite a limited two-week engagement, it became the highest-grossing documentary or concert film of all time, with earnings of more than $260 million worldwide.[333] Jackson's estate received 90% of the profits.[334] The film was accompanied by a compilation album of the same name.[335] At the 2009 American Music Awards, Jackson won four posthumous awards, two for him and two for his album Number Ones, bringing his total American Music Awards to 26.[336][337]

In late 2010, Sony released the first posthumous album, Michael, with the promotional single "Breaking News" released on November 8.[338] Sony Music paid the Jackson estate $250 million for the deal, plus royalties, making it the most expensive music contract for a single artist in history.[329][339] Video game developer Ubisoft released a music video game featuring Jackson for the 2010 holiday season, Michael Jackson: The Experience; it was among the first games to use Kinect and PlayStation Move, the motion-detecting camera systems for Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 respectively.[340] Xscape, an album of unreleased material,[341] was released on May 13, 2014.[342] Later that year, Queen released three duets recorded with Jackson and Freddie Mercury in the 1980s.[66] A compilation album, Scream, was released on September 29, 2017.[343] In 2017, Sony Music Entertainment extended its partnership with the Michael Jackson estate,[344] and in July 2018, Sony/ATV bought the Jackson estate's stake in EMI for $287.5 million.[345]

In October 2011, the theater company Cirque du Soleil launched Michael Jackson: The Immortal World Tour in Montreal, with a permanent show resident in Las Vegas.[346] The 90-minute $57-million production combined Jackson's music and choreography with the Cirque's 65 aerial dancers.[347] A compilation soundtrack album, Immortal, accompanied the tour.[348] A larger and more theatrical Cirque show, Michael Jackson: One, designed for residency at the Mandalay Bay resort in Las Vegas, opened on May 23, 2013 in a renovated theater.[349][350]

In December 2015, Thriller became the first album in the US to surpass 30 million shipments, certifying it 30× platinum.[5] A year later, it was certified again at 33× platinum, after Soundscan added streams and audio downloads to album certifications.[351] In 2018, its US sales record was overtaken by the Eagles' album Greatest Hits 1971–75, with 38× platinum.[352]

Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough, a jukebox musical, is set to debut on Broadway in 2020.[353] The production is directed and choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon and written by Lynn Nottage.[354]

Artistry

Influences

Jackson was influenced by musicians including Little Richard, James Brown,[355] Jackie Wilson, Diana Ross, Fred Astaire,[355] Sammy Davis Jr.,[355] Gene Kelly,[355][356] David Ruffin,[357] the Isley Brothers, and the Bee Gees.[358] Little Richard had a substantial influence on Jackson,[359] but James Brown was his greatest inspiration; he later said that as a small child, his mother would waken him whenever Brown appeared on television. Jackson described being "mesmerized".[360]

Jackson owed his vocal technique in large part to Diana Ross, especially his use of the oooh interjection, which he used from a young age; Ross had used this effect on many of the songs recorded with the Supremes.[361] Not only a mother figure to him, she was often observed in rehearsal as an accomplished performer.[362] He said: "I got to know her well. She taught me so much. I used to just sit in the corner and watch the way she moved. She was art in motion. I studied the way she moved, the way she sang – just the way she was." He told her: "I want to be just like you, Diana." She said: "You just be yourself."[363]

Choreographer David Winters, who met and befriended Jackson while choreographing the 1971 Diana Ross TV special Diana!, said that Jackson watched the musical West Side Story almost every week, and it was his favorite film; he paid tribute to it in "Beat It" and the "Bad" video.[358][364][365]

Musicianship

Jackson had no formal music training and could not read or write music notation.[366] He is credited for playing instruments including guitar, keyboard and drums, but was proficient in none.[366] Instead, when composing, he recorded ideas by beatboxing and imitating instruments vocally.[366] Describing his process, he said: "I'll just sing the bass part into the tape recorder. I'll take that bass lick and put the chords of the melody over the bass lick and that’s what inspires the melody."[366] Engineer Robert Hoffman recalled Jackson dictating a guitar chord note by note, and singing entire string arrangements part by part into a cassette recorder.[366]

Themes and genres

Jackson explored genres including pop, soul, rhythm and blues, funk, rock, disco, post-disco, dance-pop and new jack swing.[9][150][367][368][369][370] Steve Huey of AllMusic wrote that Thriller refined the strengths of Off the Wall; the dance and rock tracks were more aggressive, while the pop tunes and ballads were softer and more soulful.[9] Its tracks included the ballads "The Lady in My Life", "Human Nature", and "The Girl Is Mine", the funk pieces "Billie Jean" and "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'", and the disco set "Baby Be Mine" and "P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing)".[9][371][372][373] With Thriller, Christopher Connelly of Rolling Stone commented that Jackson developed his long association with the subliminal theme of paranoia and darker imagery.[373] AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine noted this is evident on the songs "Billie Jean" and "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'".[371] In "Billie Jean", Jackson sings about an obsessive fan who alleges he has fathered a child of hers.[9] In "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'" he argues against gossip and the media.[373] "Beat It" decried gang violence in an homage to West Side Story, and was Jackson's first successful rock cross-over piece, according to Huey.[9][39] He also observed that the title track "Thriller" began Jackson's interest with the theme of the supernatural, a topic he revisited in subsequent years.[9] In 1985, Jackson co-wrote the charity anthem "We Are the World"; humanitarian themes later became a recurring theme in his lyrics and public persona.[9]

In Bad, Jackson's concept of the predatory lover is seen on the rock song "Dirty Diana".[377] The lead single "I Just Can't Stop Loving You" is a traditional love ballad, while "Man in the Mirror" is a ballad of confession and resolution. "Smooth Criminal" is an evocation of bloody assault, rape and likely murder.[131] AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine states that Dangerous presents Jackson as a paradoxical individual.[378] He comments the album is more diverse than his previous Bad, as it appeals to an urban audience while also attracting the middle class with anthems like "Heal the World".[378] The first half of the record is dedicated to new jack swing, including songs like "Jam" and "Remember the Time".[379] It was the first Jackson album in which social ills become a primary theme; "Why You Wanna Trip on Me", for example, protests world hunger, AIDS, homelessness and drugs.[379] Dangerous contains sexually charged songs such as the multifaceted love song "In the Closet".[379] The title track continues the theme of the predatory lover and compulsive desire.[379] The second half includes introspective, pop-gospel anthems such as "Will You Be There", "Heal the World" and "Keep the Faith"; these songs show Jackson opening up about various personal struggles and worries.[379] In the ballad "Gone Too Soon", Jackson gives tribute to his friend Ryan White and the plight of those with AIDS.[380]