Solar power in India: Difference between revisions

rm source |

data rearranged |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

{{Use Indian English|date=December 2012}} |

{{Use Indian English|date=December 2012}} |

||

[[File:India GHI mid-size-map 156x194mm-300dpi v20191015.png|thumb|Solar potential of India]] |

[[File:India GHI mid-size-map 156x194mm-300dpi v20191015.png|thumb|Solar potential of India]] |

||

'''Solar power in India''' is a fast developing industry. The country's solar installed capacity was 35,739 MW as of 31 August 2020.<ref name=ach/ |

'''Solar power in India''' is a fast developing industry. The country's solar installed capacity was 35,739 MW as of 31 August 2020.<ref name=ach/> |

||

The Indian government had an initial target of 20 GW capacity for 2022, which was achieved four years ahead of schedule.<ref name="ToiOnSolarJan2018">{{cite web|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/developmental-issues/india-hits-20gw-solar-capacity-milestone/articleshow/62715512.cms|title=India hits 20 GW solar capacity milestone|accessdate=4 February 2018}}</ref> |

The Indian government had an initial target of 20 GW capacity for 2022, which was achieved four years ahead of schedule.<ref name="ToiOnSolarJan2018">{{cite web|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/developmental-issues/india-hits-20gw-solar-capacity-milestone/articleshow/62715512.cms|title=India hits 20 GW solar capacity milestone|accessdate=4 February 2018}}</ref> |

||

| Line 1,048: | Line 1,048: | ||

The average bid in [[reverse auction]]s in April 2017 is {{INRConvert|3.15}} per kWh, compared with {{INRConvert|12.16}} per kWh in 2010, which is around 73% drop over the time window.<ref>{{cite web |title=Solar power tariff hits a new low at Rs 3.15 levelised rate |url=http://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/solar-power-tariff-hits-a-new-low-at-rs-3-15-levelised-rate/58139132 |accessdate=12 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Solar tariffs in India have fallen by 73 percent since 2010 |url=http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/solar-tariffs-in-india-have-fallen-by-73-percent-since-2010/articleshow/57809228.cms |accessdate=24 March 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Solar tariffs in India have fallen by 73% since 2010 |url=http://www.livemint.com/Industry/xkdwxNscR9K6omngOwOaAN/Solar-tariffs-in-India-have-fallen-by-73-since-2010-Mercom.html |accessdate=24 March 2017|date=24 March 2017 }}</ref> The current prices of solar PV electricity is around 18% lower than the average [[Cost of electricity by source|price of electricity]] generated by coal-fired plants.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40120770 |title=Five effects of a US pull-out from Paris climate deal |last=McGrath |first=Matt |publisher=BBC |date=1 June 2017 |accessdate=1 June 2017 |format= }}</ref> By the end of 2018, competitive reverse auctions, falling panel and component prices, the introduction of solar parks, lower borrowing costs and large power companies have contributed to the fall in prices.<ref>{{cite news |title=How Low Did It Go: 5 Lowest Solar Tariffs Quoted in 2018 |url=https://mercomindia.com/lowest-solar-tariffs-quoted-2018/ |accessdate=9 January 2018}}</ref> The cost of solar PV power in India, China, Brazil and 55 other emerging markets fell to about one-third of its 2010 price, making solar the cheapest form of renewable energy and cheaper than power generated from fossil fuels such as coal and gas.<ref>{{cite web |title=This Just Became the World's Cheapest Form of Electricity Out of Nowhere |url=http://fortune.com/2016/12/15/solar-electricity-energy-generation-cost-cheap/ |website=Fortune |accessdate=5 February 2017}}</ref> |

The average bid in [[reverse auction]]s in April 2017 is {{INRConvert|3.15}} per kWh, compared with {{INRConvert|12.16}} per kWh in 2010, which is around 73% drop over the time window.<ref>{{cite web |title=Solar power tariff hits a new low at Rs 3.15 levelised rate |url=http://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/solar-power-tariff-hits-a-new-low-at-rs-3-15-levelised-rate/58139132 |accessdate=12 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Solar tariffs in India have fallen by 73 percent since 2010 |url=http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/solar-tariffs-in-india-have-fallen-by-73-percent-since-2010/articleshow/57809228.cms |accessdate=24 March 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Solar tariffs in India have fallen by 73% since 2010 |url=http://www.livemint.com/Industry/xkdwxNscR9K6omngOwOaAN/Solar-tariffs-in-India-have-fallen-by-73-since-2010-Mercom.html |accessdate=24 March 2017|date=24 March 2017 }}</ref> The current prices of solar PV electricity is around 18% lower than the average [[Cost of electricity by source|price of electricity]] generated by coal-fired plants.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40120770 |title=Five effects of a US pull-out from Paris climate deal |last=McGrath |first=Matt |publisher=BBC |date=1 June 2017 |accessdate=1 June 2017 |format= }}</ref> By the end of 2018, competitive reverse auctions, falling panel and component prices, the introduction of solar parks, lower borrowing costs and large power companies have contributed to the fall in prices.<ref>{{cite news |title=How Low Did It Go: 5 Lowest Solar Tariffs Quoted in 2018 |url=https://mercomindia.com/lowest-solar-tariffs-quoted-2018/ |accessdate=9 January 2018}}</ref> The cost of solar PV power in India, China, Brazil and 55 other emerging markets fell to about one-third of its 2010 price, making solar the cheapest form of renewable energy and cheaper than power generated from fossil fuels such as coal and gas.<ref>{{cite web |title=This Just Became the World's Cheapest Form of Electricity Out of Nowhere |url=http://fortune.com/2016/12/15/solar-electricity-energy-generation-cost-cheap/ |website=Fortune |accessdate=5 February 2017}}</ref> |

||

India has the lowest capital cost per MW globally of installing [[solar power]] plants.<ref>{{cite news|title=India becomes lowest-cost producer of solar power |url=https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/india-becomes-lowest-cost-producer-of-solar-power/69565769|accessdate=1 June 2019}}</ref> However the global [[Cost of electricity by source|levelized cost]] of solar PV electricity fell to 1.31¢ US per kWh (₹0.97 per kWh) in April 2020, much cheaper than the lowest solar PV tariff in India.<ref>{{cite web |title=India Unable to Compete With Record Low Solar Tariffs in Gulf Region|url=https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/India-Unable-to-Compete-with-Record-Low-Solar-Tariffs_August-2020.pdf |accessdate= 28 August 2020 }}</ref><ref name="por">{{cite web|title=‘Historic’ result as Portugal claims record-low prices in 700MW solar auction|url=https://www.pv-tech.org/news/historic-result-as-portugal-claims-record-low-prices-in-700mw-solar-auction|accessdate=27 August 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Abu Dhabi announces world’s lowest tariff for solar power |url=https://www.arabnews.com/node/1666846/business-economy |accessdate= 29 April 2020 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pv-tech.org/guest-blog/ultra-low-solar-bid-of-0.01997-kwh-in-the-us-not-quite-so-sunny |title=Ultra-low solar bid of $0.01997/kWh in the US – not quite so sunny |accessdate=5 August 2019 }}</ref> The intermittent / non-dispatchable solar PV at the prevailing low tariffs clubbed with [[Thermal energy storage#Pumped-heat electricity storage|Pumped-heat electricity storage]] can offer cheapest [[Dispatchable generation|dispatchable power]] round the clock on demand. |

|||

The Indian government has reduced the solar PV power purchase price from the maximum allowed {{INRConvert|4.43|2}} per KWh to {{INRConvert|4.00|2}} per KWh, reflecting the steep fall in cost of solar power-generation equipment.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://indianexpress.com/article/business/solar-power-tariff-dips-to-all-time-low-of-rs-4-per-unit-4363579/ |title=Solar power tariff dips to all-time low of Rs 4 per unit|accessdate=10 November 2016|date=8 November 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://indianpowersector.com/2015/12/seci-lowers-the-solar-tariff-to-inr-4-43-per-unit-fixed-for-upcoming-biddings/ |title=SECI lowers the solar tariff to INR 4.43 per unit fixed for upcoming biddings |accessdate=25 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.financialexpress.com/article/economy/cerc-capital-cost-move-suggests-solar-tariff-to-fall-further-in-fy17/183752/ |title=CERC capital cost move suggests solar tariff to fall further in FY17 |accessdate=25 December 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151225153324/http://www.financialexpress.com/article/economy/cerc-capital-cost-move-suggests-solar-tariff-to-fall-further-in-fy17/183752/ |archive-date=25 December 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The applicable tariff is offered after applying [[Public–private partnership|viability gap funding]] (VGF) or accelerated depreciation (AD) incentives.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/grid-solar/Scheme-2000MW-Grid-Connected-SPV-with-VGF-under-JNNSM.pdf |title=Grid Connected SPV with VGF under JNNSM |accessdate=25 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/solar-auction-companies-seeking-lowest-state-support-win/articleshow/52138023.cms |title=Solar auction companies seeking lowest state support to win |accessdate=10 May 2016|newspaper=The Economic Times |date=6 May 2016 |last1=Chandrasekaran |first1=Kaavya }}</ref> In January 2019, the time period for commissioning the solar power plants is reduced to 18 months for units located outside the solar parks and 15 months for units located inside the solar parks from the date of power purchase agreement.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://mercomindia.com/amendment-bidding-guidelines-solar-pv/ |title=MNRE Amends Bidding Guidelines for Solar Projects; Reduces Commissioning Time Frame |accessdate=11 January 2017}}</ref> |

The Indian government has reduced the solar PV power purchase price from the maximum allowed {{INRConvert|4.43|2}} per KWh to {{INRConvert|4.00|2}} per KWh, reflecting the steep fall in cost of solar power-generation equipment.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://indianexpress.com/article/business/solar-power-tariff-dips-to-all-time-low-of-rs-4-per-unit-4363579/ |title=Solar power tariff dips to all-time low of Rs 4 per unit|accessdate=10 November 2016|date=8 November 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://indianpowersector.com/2015/12/seci-lowers-the-solar-tariff-to-inr-4-43-per-unit-fixed-for-upcoming-biddings/ |title=SECI lowers the solar tariff to INR 4.43 per unit fixed for upcoming biddings |accessdate=25 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.financialexpress.com/article/economy/cerc-capital-cost-move-suggests-solar-tariff-to-fall-further-in-fy17/183752/ |title=CERC capital cost move suggests solar tariff to fall further in FY17 |accessdate=25 December 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151225153324/http://www.financialexpress.com/article/economy/cerc-capital-cost-move-suggests-solar-tariff-to-fall-further-in-fy17/183752/ |archive-date=25 December 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The applicable tariff is offered after applying [[Public–private partnership|viability gap funding]] (VGF) or accelerated depreciation (AD) incentives.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/grid-solar/Scheme-2000MW-Grid-Connected-SPV-with-VGF-under-JNNSM.pdf |title=Grid Connected SPV with VGF under JNNSM |accessdate=25 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/solar-auction-companies-seeking-lowest-state-support-win/articleshow/52138023.cms |title=Solar auction companies seeking lowest state support to win |accessdate=10 May 2016|newspaper=The Economic Times |date=6 May 2016 |last1=Chandrasekaran |first1=Kaavya }}</ref> In January 2019, the time period for commissioning the solar power plants is reduced to 18 months for units located outside the solar parks and 15 months for units located inside the solar parks from the date of power purchase agreement.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://mercomindia.com/amendment-bidding-guidelines-solar-pv/ |title=MNRE Amends Bidding Guidelines for Solar Projects; Reduces Commissioning Time Frame |accessdate=11 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:05, 3 October 2020

This article contains promotional content. (October 2020) |

Solar power in India is a fast developing industry. The country's solar installed capacity was 35,739 MW as of 31 August 2020.[1]

The Indian government had an initial target of 20 GW capacity for 2022, which was achieved four years ahead of schedule.[2] In 2015 the target was raised to 100 GW of solar capacity (including 40 GW from rooftop solar) by 2022, targeting an investment of US$100 billion.[3][4] India has established nearly 42 solar parks to make land available to the promoters of solar plants.[5]

Rooftop solar power accounts for 2.1 GW, of which 70% is industrial or commercial.[6] In addition to its large-scale grid-connected solar photovoltaic (PV) initiative, India is developing off-grid solar power for local energy needs.[7] Solar products have increasingly helped to meet rural needs; by the end of 2015 just under one million solar lanterns were sold in the country, reducing the need for kerosene.[8] That year, 118,700 solar home lighting systems were installed and 46,655 solar street lighting installations were provided under a national program;[8] just over 1.4 million solar cookers were distributed in India.[8]

The International Solar Alliance (ISA), proposed by India as a founder member, is headquartered in India. India has also put forward the concept of "One Sun One World one Grid" and "World Solar Bank" to harness abundant solar power on global scale.[9][10]

National solar potential

With about 300 clear and sunny days in a year, the calculated solar energy incidence on India's land area is about 5000 trillion kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year (or 5 EWh/yr).[11][12] The solar energy available in a single year exceeds the possible energy output of all of the fossil fuel energy reserves in India. The daily average solar-power-plant generation capacity in India is 0.30 kWh per m2 of used land area,[citation needed] equivalent to 1400–1800 peak (rated) capacity operating hours in a year with available, commercially-proven technology.[13][14][15]

Installations by region

Installed cumulative national and state-wise capacity

| Year | Cumulative Capacity (in MW) |

|---|---|

| 2010 | |

| 2011 | |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2015 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2019 | |

| 2020 |

| State | 31 March 2015 | 31 March 2016 | 31 March 2017 | 31 March 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajasthan | 942.10 | 1,269.93 | 1,812.93 | 3,226.79 |

| Punjab | 185.27 | 405.06 | 793.95 | 905.62 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 71.26 | 143.50 | 336.73 | 960.10 |

| Uttarakhand | 5.00 | 41.15 | 233.49 | 306.75 |

| Haryana | 12.80 | 15.39 | 81.40 | 224.52 |

| Delhi | 5.47 | 14.28 | 40.27 | 126.89 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 0.00 | 1.36 | 1.36 | 14.83 |

| Chandigarh | 4.50 | 6.81 | 17.32 | 34.71 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 22.68 |

| Total Northern Region |

3318.18 | 6102.05 (21.43%) | ||

| Gujarat | 1,000.05 | 1,119.17 | 1,249.37 | 2,440.13 |

| Maharashtra | 360.75 | 385.76 | 452.37 | 1,633.54 |

| Chhattisgarh | 7.60 | 93.58 | 128.86 | 231.35 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 558.58 | 776.37 | 857.04 | 1,840.16 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.97 | 5.46 |

| Goa | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 3.81 |

| Daman and Diu | 0.00 | 4.00 | 10.46 | 14.47 |

| Total Western Region |

2701.78 | 6169.03 (21.67%) | ||

| Tamil Nadu | 142.58 | 1,061.82 | 1,691.83 | 2,575.22 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 137.85 | 572.97 | 1,867.23 | 3,085.68 |

| Telangana | 167.05 | 527.84 | 1,286.98 | 3,592.09 |

| Kerala | 0.03 | 13.05 | 74.20 | 138.59 |

| Karnataka | 77.22 | 145.46 | 1,027.84 | 6,095.56 |

| Puducherry | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 3.14 |

| Total Southern Region |

5948.16 | 15490.28 (54.42%) | ||

| Bihar | 0.00 | 5.10 | 108.52 | 142.45 |

| Odisha | 31.76 | 66.92 | 79.42 | 394.73 |

| Jharkhand | 16.00 | 16.19 | 23.27 | 34.95 |

| West Bengal | 7.21 | 7.77 | 26.14 | 75.95 |

| Sikkim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Total Eastern Region |

237.35 | 648.09 (2.27%) | ||

| Assam | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.78 | 22.40 |

| Tripura | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.09 | 5.09 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 5.39 |

| Mizoram | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| Manipur | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 3.44 |

| Meghalaya | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Nagaland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Total North Eastern Region |

17.78 | 37.94 (0.13%) | ||

| Andaman and Nicobar | 5.10 | 5.10 | 6.56 | 11.73 |

| Lakshadweep | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Others | 0.00 | 58.31 | 58.31 | 0.00 |

| Total Islands and others |

65.62 | 16.78 (0.06%) | ||

| Total India | 3,743.97 | 6,762.85 | 12,288.83 | 28,180.66 |

Andhra Pradesh

Installed photo-voltaic capacity in Andhra Pradesh was 3,531 MW as of 31 August 2020.[17] The state is planning to add 10,050 MW solar power capacity to provide power supply to farming sector during the day time.[18][19] The state has also offered five Ultra Mega Solar Power Projects with a total capacity of 12,200 MW to developers under renewable power export policy outside the state.[20][21][22][23][24] Andhra Pradesh is endowed with abundant pumped hydroelectric energy storage to make available solar power in to round the clock power supply for meeting its ultimate energy needs.[25][26][27]

In 2015, NTPC agreed with APTransCo to install the 250-MW NP Kunta Ultra Mega Solar Power Project near Kadiri in Anantapur district.[28][29] In October 2017, 1000 MW was commissioned at Kurnool Ultra Mega Solar Park which has become the world's largest solar power plant at that time.[30] In August 2018, Greater Visakhapatnam commissioned a 2 MW Mudasarlova Reservoir grid-connected floating solar project which is the largest operational floating solar PV project in India.[31] NTPC Simhadri has awarded BHEL to install a 25 MW floating solar PV plant on its water supply reservoir.[32] APGENCO commissioned 400 MW Ananthapuram - II solar park located at Talaricheruvu village near Tadipatri.[33]

Delhi

Delhi being the Capital and a city state in India, has limitation in installing ground mounted solar power plants. However it is leading in rooftop solar PV installations by adopting fully flexible net metering system.[34] The installed solar power capacity is 106 MW as on 30 September 2018. Delhi government has announced that the Rajghat thermal power plant will be officially shut at the 45 acre plant site and turned into a 5 MW solar power PV plant.

Gujarat

Gujarat is one of India's most solar-developed states, with its total photovoltaic capacity reaching 1,637 MW by the end of January 2019. Gujarat has been a leader in solar-power generation in India due to its high solar-power potential, availability of vacant land, connectivity, transmission and distribution infrastructure and utilities. According to a report by the Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP) report, these attributes are complemented by political will and investment.[full citation needed] The 2009 Solar Power of Gujarat policy framework, financing mechanism and incentives have contributed to a green investment climate in the state and targets for grid-connected solar power.[35][36]

The state has commissioned Asia's largest solar park near the village of Charanka in Patan district.[37] The park is generating 345 MW by March 2016 of its 500 MW total planned capacity and has been cited as an innovative and environmentally-friendly project by the Confederation of Indian Industry.[full citation needed] In December 2018, 700 MW Solar PV plant at Raghanesda Solar Park is contracted at 2.89 Rs/unit levelised tariff.[38]

To make Gandhinagar a solar-power city, the state government has begun a rooftop solar-power generation scheme. Under the scheme, Gujarat plans to generate 5 MW of solar power by putting solar panels on about 50 state-government buildings and 500 private buildings.

It also plans to generate solar power by putting solar panels along the Narmada canals. As part of this scheme, the state has commissioned the 1 MW Canal Solar Power Project on a branch of the Narmada Canal near the village of Chandrasan in Mehsana district. The pilot project is expected to stop 90,000 litres (24,000 US gal; 20,000 imp gal) of water per year from evaporating from the Narmada River.

Haryana

State has set the 4.2 GW solar power (including 1.6 GW solar roof top) target by 2022 as it has high potential since it has at least 330 sunny days. Haryana is one of the fastest growing state in terms of solar energy with installed and commissioned capacity of 73.27 MW. Out of this, 57.88 MW was commissioned in FY 2016/17. Haryana solar power policy announced in 2016 offers 90% subsidy to farmers for the solar powered water pumps, which also offers subsidy for the solar street lighting, home lighting solutions, solar water heating schemes, solar cooker schemes. It is mandatory for new residential buildings larger than 500 square yards (420 m2) to install 3% to 5% solar capacity for no building plan sanctioning is required, and a loan of up to Rs. 10 lacs is made available to the residential property owners. Haryana provides 100% waiver of electricity taxes, cess, electricity duty, wheeling charges, cross subsidy charges, transmission and distribution charges, etc. for rooftop solar projects.

In December 2018, Haryana had installed solar capacity of 48.80 MW,[39] and in January 2019 Haryana floated tender for 300 MW grid-connected solar power,[40] and additional 16 MW tender for the canal top solar power.[41]

Karnataka

Karnataka is the top solar state in India exceeding 5,000 MW installed capacity by the end of financial year 2017–18.[42] The installed capacity of Pavagada Solar Park is 2050 MW by the end of year 2019 which was the world biggest solar park at that time.[43]

Kerala

Kerala's largest floating solar power plant was set upon the Banasura Sagar Dam reservoir in Wayanad district, Kerala.[44] The 500 kW (kilowatt peak) solar plant of the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) floats on 1.25 acres of the water surface of the reservoir. The solar plant has 1,938 solar panels which have been installed on 18 Ferro concrete floaters with hollow insides.[45]

Ladakh

Ladakh, though a late entrant in solar power plants, is planning to install nearly 7,500 MW capacity in few years.[46]

Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh is one of India's most solar-developed states, with its total photovoltaic capacity reaching 1,117 MW by the end of July 2017. The Welspun Solar MP project, the largest solar-power plant in the state, was built at a cost of ₹1,100 crore (US$130 million) on 305 ha (3.05 km2) of land and will supply power at ₹8.05 (9.6¢ US) per kWh. A 130 MW solar power plant project at Bhagwanpura, a village in Neemuch district, was launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It is the largest solar producer, and Welspun Energy is one of the top three companies in India's renewable-energy sector.[47] A planned 750 MW solar-power plant in Rewa district, the Rewa Ultra Mega Solar plant, was completed and inagurated on 10 July 2020.[48] Spread over 1,590 acres, it is Asia's largest solar power plant and was constructed at a cost of ₹4,500 crore.[49][50]

Maharashtra

The 125-MW Sakri solar plant is the largest solar-power plant in Maharashtra. The Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust has the world's largest solar steam system. It was constructed at the Shirdi shrine at an estimated cost of ₹1.33 crore (US$160,000), ₹58.4 lakh (US$70,000) which was paid as a subsidy by the renewable-energy ministry. The system is used to cook 50,000 meals per day for pilgrims visiting the shrine, resulting in annual savings of 100,000 kg of cooking gas, and was designed to generate steam for cooking even in the absence of electricity to run the circulating pump. The project to install and commission the system was completed in seven months, and the system has a design life of 25 years.[51][52][53] The Osmanabad region in Maharashtra has abundant sunlight, and is ranked the third-best region in India in solar insolation. A 10 MW solar power plant in Osmanabad was commissioned in 2013. The total power capacity of Maharashtra is about 500 MW.

Rajasthan

Rajasthan is one of India's most solar-developed states, with its total photovoltaic capacity reaching 2289 MW by end of June 2018. Rajasthan is also home to the world's largest Fresnel type 125 MW CSP plant at the Dhirubhai Ambani Solar Park.[54][55] Jodhpur district leads the state with installed capacity of over 1,500 MW, followed by Jaisalmer and Bikaner.

The Bhadla Solar Park, with total installed capacity of 2,245 MW, is the biggest plant in the world as on March 2020.

The only tower type solar thermal power plant (2.5 MW) in India is located in Bikaner district.[56]

In March 2019, The lowest tariff in India is ₹2.48/kWh for installing the 750 MW solar power plants in the state.[57]

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu has the 5th highest operating solar-power capacity in India in May 2018. The total operating capacity in Tamil Nadu is 1.8 GW.[42] On 1 July 2017, Solar power tariff in Tamil Nadu has hit an all-time low of Rs 3.47 per unit when bidding for 1500 MW capacity was held.[58][59]

The 648-MW Kamuthi Solar Power Project is the biggest operating project in the state. On 1 January 2018, NLC India Limited (NLCIL) commissioned a new 130 MW solar power project in Neyveli.[60]

Telangana

Telangana ranks second when it comes to solar energy generation capacity in India. The state is trailing behind Karnataka with a solar power generation capacity of 3400 MW and plans to achieve a capacity of 5000 MW by 2022. NTPC Ramagundam has placed work order on BHEL to install 100 MW floating solar PV plant on its water supply reservoir.[32]

Electricity generation

The country's solar installed capacity was 35,739 MW as of 30 June 2020.[1] Solar electricity generation from April 2019 to March 2020 was 50.1 TWh,[61] or 3.6% of total generation (1,391 TWh).[62][61]

| Year | Solar power generation (TWh) |

|---|---|

| 2013–14 | |

| 2014–15 | |

| 2015–16 | |

| 2016–17 | |

| 2017–18 | |

| 2018–19 | |

| 2019–20 |

| Month | Regional solar power generation (GWh)[63] | Total (GWh) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | West | South | East | North East | ||

| April 2019 | 839.92 | 903.75 | 2,358.89 | 64.69 | 1.41 | 4,168.67 |

| May 2019 | 942.89 | 926.49 | 2,402.74 | 53.94 | 1.37 | 4,327.42 |

| June 2019 | 932.40 | 787.48 | 2,136.10 | 61.13 | 1.02 | 3,918.13 |

| July 2019 | 785.69 | 702.83 | 1,889.87 | 48.44 | 1.23 | 3,428.06 |

| August 2019 | 796.67 | 630.70 | 2,111.37 | 36.03 | 0.97 | 3,575.73 |

| September 2019 | 885.50 | 585.18 | 2,054.69 | 38.84 | 0.93 | 3,565.14 |

| October 2019 | 988.51 | 763.85 | 2,074.86 | 54.23 | 0.97 | 3,882.41 |

| November 2019 | 807.47 | 776.97 | 2,305.09 | 46.22 | 1.07 | 3,936.82 |

| December 2019 | 851.38 | 803.72 | 2,228.86 | 43.31 | 1.13 | 3,928.39 |

| January 2020 | 945.68 | 904.87 | 2,712.82 | 48.35 | 1.00 | 4,612.72 |

| February 2020 | 1,151.87 | 979.12 | 2,906.16 | 51.97 | 1.54 | 5,090.66 |

| March 2020 | 1,218.18 | 1,091.06 | 3,253.81 | 68.66 | 1.59 | 5,633.30 |

| Total (GWh) | 11,146.16 | 9,856.02 | 28,498.91 | 615.81 | 14.2 | 50,131.10 |

Installations by application

| Application | 31 July 2019 |

|---|---|

| Solar power ground mounted | 27,930.32 |

| Solar power rooftop | 2,141.03 |

| Off-grid solar power | 919.15 |

| TOTAL | 30,990.50 |

As of July 2019 by far the largest segment of solar PV installed in India was ground mounted at 27,930 MW installed capacity. This sector comprises mostly larger scale solar projects and even larger utility solar projects that generate power centrally and disperse it over the grid. The next largest segment was rooftop solar at 2,141 MW which can be divided into residential solar, commercial and industrial solar roofs as well as a range of installations including agricultural buildings, community and cultural centres. 70 percent of rooftop solar in 2018 was in the industrial and commercial sectors, with just 20 percent as residential rooftop solar.[6] Rooftop solar as a proportion of total solar installations is much less than is typical in other leading solar countries but was forecast to grow to 40 GW by 2022 under national targets.[4] A rough calculation would imply that India had around just 430 MW of residential rooftop solar, whilst the UK with around half the overall solar capacity of India had over 2,500 MW of residential solar in 2018. The smallest segment was off-grid solar at 919 MW which could help play a role in reaching villages and dwellings without access to the national grid.

Major photovoltaic power stations

Below is a list of solar power generation facilities with a capacity of at least 10 MW.[65]

| Plant | State | Coordinates | DC peak power (MW) | Commissioned | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhadla Solar Park | Rajasthan | 27°32′22.81″N 71°54′54.91″E / 27.5396694°N 71.9152528°E | 2245 | March 2020 | World's biggest solar park in terms of generation and Second largest in terms of area as on March 2020 | [66][67][68] |

| Pavagada Solar Park | Karnataka | 14°15′7″N 77°26′51″E / 14.25194°N 77.44750°E | 2,050 | December 2019 | Second biggest solar park in the world and world's largest in terms of area as on March 2020 | [69] |

| Kurnool Ultra Mega Solar Park | Andhra Pradesh | 15°40′53″N 78°17′01″E / 15.681522°N 78.283749°E | 1,000 | 2017 | [70] | |

| NP Kunta | Andhra Pradesh | 14°01′N 78°26′E / 14.017°N 78.433°E | 900 | 2020 | In Nambulapulakunta Mandal. Total planned capacity 1500 MW | [71][72][73] |

| Rewa Ultra Mega Solar | Madhya Pradesh | 24°28′49″N 81°34′28″E / 24.48028°N 81.57444°E | 750 | 2018 | [74] | |

| Charanka Solar Park | Gujarat | 23°54′N 71°12′E / 23.900°N 71.200°E | 690 | 2012 | Situated at Charanka village in Patan district. Capacity expected to go up to 790 MW in 2019. | [75][76][77] |

| Kamuthi Solar Power Project | Tamil Nadu | 9°20′51″N 78°23′32″E / 9.347568°N 78.392162°E | 648 | March 2017 | With a generating capacity of 648 MWp at a single location, it is the world's 12th largest solar park based on capacity. | |

| Ananthapuramu - II | Andhra Pradesh | 14°58′49″N 78°02′45″E / 14.98028°N 78.04583°E | 400 | 2019 | Located at Talaricheruvu village in Tadipatri mandal of Anantapur district. Planned capacity 500 MW | [78][79] |

| Galiveedu solar park | Andhra Pradesh | 14°6′21″N 78°27′57″E / 14.10583°N 78.46583°E | 400 | 2020 | Located at Marrikommadinne village in Galiveedu mandal of kadapa district. | [80] |

| Mandsaur Solar Farm | Madhya Pradesh | 24°5′17″N 75°47′59″E / 24.08806°N 75.79972°E | 250 | 2017 | [81] | |

| Kadapa Ultra Mega Solar Park | Andhra Pradesh | 14°54′59″N 78°17′31″E / 14.91639°N 78.29194°E | 250 | 2020 | Total planned capacity 1000 MW | [82][83] |

| Gujarat Solar Park-1[84] | Gujarat | 221 | April 2012 | |||

| Welspun Solar MP project[85] | Madhya Pradesh | 151 | February 2014 | |||

| ReNew Power, Nizamabad | Telangana | 143 | 15 April 2017[86] | |||

| Sakri solar plant | Maharashtra | 125 | March 2013 | |||

| NTPC solar plants[87] | 110 | 2015 | ||||

| Maharashtra I | Maharashtra | 67 | 2017 | |||

| Green Energy Development Corporation (GEDCOL)[88] | Odisha | 50 | 2014 | |||

| Tata Power Solar Systems (TPS), Rajgarh[89] | Madhya Pradesh | 50 | March 2014 | |||

| Welspun Energy, Phalodhi[90] | Rajasthan | 50 | March 2013 | |||

| Jalaun Solar Power Project | Uttar Pradesh | 50 | 27 January 2016 | |||

| GEDCOL[91] | Odisha | 48 | 2014 | |||

| Karnataka I | Karnataka | 40 | 2018 | |||

| Bitta Solar Power Plant[92] | Gujarat | 40 | January 2012 | |||

| Dhirubhai Ambani Solar Park, Pokhran[93] | Rajasthan | 40 | April 2012 | |||

| Rajasthan Photovoltaic Plant[94] | Rajasthan | 35 | February 2013 | |||

| Welspun, Bathinda[95] | Punjab | 34 | August 2015 | |||

| Moser Baer, Patan district[96] | Gujarat | 30 | October 2011 | |||

| Lalitpur Solar Power Project[97] | Uttar Pradesh | 30 | 2015 | |||

| Mithapur Solar Power Plant[98] | Gujarat | 25 | 25 January 2012 | |||

| GEDCOL[99] | Odisha | 20 | 2014 | |||

| Kadodiya Solar Park | Madhya Pradesh | 15 | 2014 | |||

| Telangana I | Telangana | 12 | 2016 | |||

| Telangana II | Telangana | 12 | 2016 | |||

| NTPC | Odisha | 10 | 2014 | |||

| Sunark Solar | Odisha | 10 | 2011 | |||

| RNS Infrastructure Limited, Pavagada | Karnataka | 10 | 2016 | |||

| Bolangir Solar Power Project | Odisha | 10 | 2011 | |||

| Azure Power, Sabarkantha[100][101] | Gujarat | 10 | June 2011 | |||

| Green Infra Solar Energy, Rajkot[102][103] | Gujarat | 10 | November 2011 | |||

| Waa Solar Power Plant, Surendranagar[104] | Gujarat | 10 | December 2011 | |||

| Sharda Construction, Latur[105] | Maharashtra | 10 | June 2015 | |||

| Ushodaya Project, Midjil | Telangana | 10 | December 2013 |

Solar photovoltaic growth forecasts

In August 2016, the forecast for solar photovoltaic installations was about 4.8 GW for the calendar year. About 2.8 GW was installed in the first eight months of 2016, more than all 2015 solar installations. India's solar projects stood at about 21 GW, with about 14 GW under construction and about 7 GW to be auctioned.[106] The country's solar capacity reached 19.7 GW by the end of 2017, making it the third-largest global solar market.[107]

In mid-2018 the Indian power minister RK Singh flagged a tender for a 100GW solar plant at an event in Delhi, while discussing a 10GW tender due to be issued in July that year (at the time, a world record). He also increased the government target for installed renewable energy by 2022 to 227GW.[108]

Solar thermal power

The installed capacity of commercial solar thermal power plants (non storage type) in India is 227.5 MW with 50 MW in Andhra Pradesh and 177.5 MW in Rajasthan.[109] The existing solar thermal power plants (non-storage type) in India, which are generating costly intermittent power on daily basis, can be converted into storage type solar thermal plants to generate 3 to 4 times more base load power at cheaper cost and not depend on government subsidies.[110] In March 2020, SECI called for 5000 MW tenders which can be combination of solar PV with battery storage, solar thermal with thermal energy storage (including biomass firing as supplementary fuel) and coal based power (minimum 51% from renewable sources) to supply round the clock power at minimum 80% yearly availability.[111]

Hybrid solar plants

Solar power, generated mainly during the daytime in the non-monsoon period, complements wind which generate power during the monsoon months in India.[112][113] Solar panels can be located in the space between the towers of wind-power plants.[114] It also complements hydroelectricity, generated primarily during India's monsoon months. Solar-power plants can be installed near existing hydropower and pumped-storage hydroelectricity, utilizing the existing power transmission infrastructure and storing the surplus secondary power generated by the solar PV plants.[115][116] Floating solar plants on the reservoirs of pumped-storage hydroelectric plants are complementary to each other.[117] Solar PV plants clubbed with pumped-storage hydroelectric plants are also under construction to supply peaking power.[118]

During the daytime, the additional auxiliary power consumption of a solar thermal storage power plant is nearly 10% of its rated capacity for the process of extracting solar energy in the form of thermal energy.[119] This auxiliary power requirement can be made available from cheaper solar PV plant by envisaging hybrid solar plant with a mix of solar thermal and solar PV plants at a site. Also to optimise the cost of power, generation can be from the cheaper solar PV plant (33% generation) during the daylight whereas the rest of the time in a day is from the solar thermal storage plant (67% generation from Solar power tower and parabolic trough types) for meeting 24 hours baseload power.[120] When solar thermal storage plant is forced to idle due to lack of sunlight locally during cloudy days in monsoon season, it is also possible to consume (similar to a lesser efficient, huge capacity and low cost battery storage system) the cheap excess grid power when the grid frequency is above 50 hz for heating the hot molten salt to higher temperature for converting stored thermal energy in to electricity during the peak demand hours when the electricity sale price is profitable.[121][122][123]

Solar heating

Generating hot water or air or steam using concentrated solar reflectors, is increasing rapidly. Presently concentrated solar thermal installation base for heating applications is about 20 MWth in India and expected to grow rapidly.[124][125] Cogeneration of steam and power round the clock is also feasible with solar thermal CHP plants with thermal storage capacity.

Bengaluru has the largest deployment of roof-top solar water heaters in India, generating an energy equivalent of 200 MW.[126] It is India's first city to provide a rebate of ₹50 (60¢ US) on monthly electricity bills for residents using roof-top thermal systems,[127] which are now mandatory in all new structures. Pune has also made solar water heaters mandatory in new buildings.[128] Photovoltaic thermal (PVT) panels produce simultaneously the required warm water/air along with electricity under sunlight.[129]

Rural electrification

The lack of an electricity infrastructure is a hurdle to rural India's development. India's power grid is under-developed, with large groups of people still living off the grid.[130] In 2004, about 80,000 of the nation's villages still did not have electricity, 18,000 out of them could not be electrified by extending the conventional grid due to inconvenience. A target of electrifying 5,000 such villages was set for the 2002–2007 Five-Year Plan. By 2004 more than 2,700 villages and hamlets were electrified, primarily with solar photovoltaic systems.[11] The development of inexpensive solar technology is considered a potential alternative, providing an electricity infrastructure consisting of a network of local-grid clusters with distributed electricity generation.[131] It could bypass (or relieve) expensive, long-distance, centralized power-delivery systems, bringing inexpensive electricity to large groups of people.[132] In Rajasthan during Financial Year 2016–17, 91 villages have been electrified with a solar standalone system and over 6,200 households have received a 100W solar home-lighting system.[citation needed]

India has sold or distributed about 1.2 million solar home-lighting systems and 3.2 million solar lanterns, and has been ranked the top Asian market for solar off-grid products.[133][134][135][136]

Lamps and lighting

By 2012, a total of 4,600,000 solar lanterns and 861,654 solar-powered home lights were installed. Typically replacing kerosene lamps, they can be purchased for the cost of a few months' worth of kerosene with a small loan. The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy is offering a 30- to 40-percent subsidy of the cost of lanterns, home lights and small systems (up to 210 Wp).[137] Twenty million solar lamps are expected by 2022.[138]

Agricultural support

Solar photovoltaic water-pumping systems are used for irrigation and drinking water.[139] Most pumps are fitted with a 200–3,000 W (0.27–4.02 hp) motor powered with a 1,800 Wp PV array which can deliver about 140,000 litres (37,000 US gal) of water per day from a total hydraulic head of 10 m (33 ft). By 31 October 2019 a total of 181,521 solar photovoltaic water pumping systems were installed and total solar photovoltaic water pumping systems would reach 3.5 million by the year 2022 under PM KUSUM scheme.[140][141] During hot sunny daytime when the water needs are more for watering the fields, solar pumps performance can be improved by maintaining pumped water flowing/sliding over the solar panels to keep them cooler and clean.[142] Agro photovoltaics is the electricity generation without losing agriculture production by using the same land.[143] Solar driers are used to dry harvests for storage.[144] Low cost solar powered bicycles are also available to ply between fields and village for agricultural activity, etc.[145]

Rainwater harvesting

In addition to solar energy, rainwater is a major renewable resource of any area. In India, large areas are being covered by solar PV panels every year. Solar panels can also be used for harvesting most of the rainwater falling on them and drinking or breweries water quality, free from bacteria and suspended matter, can be generated by simple filtration and disinfection processes, as rainwater is very low in salinity.[146][147] Good quality water resources, closer to populated areas, are becoming a scarcity and increasingly costly for consumers. Exploitation of rainwater for value-added products like bottled drinking water makes solar PV power plants profitable even in high rainfall and cloudy areas by the increased income from drinking water generation.[148]

Refrigeration and air conditioning

Thin-film solar cell panels offer better performance than crystalline silica solar panels in tropical hot and dusty places like India; there is less deterioration in conversion efficiency with increased ambient temperature, and no partial shading effect. These factors enhance the performance and reliability (fire safety) of thin-film panels.[149][150][151] Maximum solar-electricity generation during the hot hours of the day can be used for meeting residential air-conditioning requirements regardless of other load requirements, such as refrigeration, lighting, cooking and water pumping. Power generation of photovoltaic modules can be increased by 17 to 20 percent by equipping them with a tracking system.[152][153]

Residential electricity consumers who are paying higher slab rates more than ₹5 (6.0¢ US) per unit, can form in to local groups to install collectively rooftop off-grid solar power units (without much battery storage) and replace the costly power used from the grid with the solar power as and when produced. Hence power draw from the grid which is an assured power supply without much power cuts nowadays, serves as cheaper back up source when grid power consumption is limited to lower slab rate by using solar power during the day time. The maximum power generation of solar panels during the sunny daytime is complementary with the enhanced residential electricity consumption during the hot/summer days due to higher use of cooling appliances such as fans, refrigerators, air conditioners, desert coolers, etc. It would discourage the Discoms to extract higher electricity charges selectively from its consumers.[154] There is no need of any permission from Discoms similar to DG power sets installation. Cheaper discarded batteries of electric vehicle can also be used economically to store the excess solar power generated in the daylight.[155][156]

Grid stabilisation

Solar-power plants equipped with battery storage systems where net energy metering is used can feed stored electricity into the power grid when its frequency is below the rated parameter (50 Hz) and draw excess power from the grid when its frequency is above the rated parameter.[157] Excursions above and below the rated grid frequency occur about 100 times daily.[158][159] The solar-plant owner would receive nearly double the price for electricity sent into the grid compared to that consumed from the grid if a frequency-based tariff is offered to rooftop solar plants or plants dedicated to a distribution substation.[160][161] A power-purchase agreement (PPA) is not needed for solar plants with a battery storage systems to serve ancillary-service operations and transmit generated electricity for captive consumption using an open-access facility.[162][163] Battery storage is popular in India, with more than 10 million households using battery backup during load shedding.[164] Battery storage systems are also used to improve the power factor.[165] Solar PV or wind paired with four-hour battery storage systems is already cost competitive, without subsidy and power purchase agreement by selling peak power in Indian Energy Exchange, as a source of dispatchable generation compared with new coal and new gas plants in India”.[166][167]

Battery storage is also used economically to reduce daily/monthly peak power demand for minimising the monthly demand charges from the utility to the commercial and industrial establishments.[168] Construction power tariffs are very high in India.[169] Construction power needs of long gestation mega projects can be economically met by installing solar PV plants for permanent service in the project premises with or without battery storage for minimising use of Standby generator sets or costly grid power.[170]

Challenges and opportunities

The land price is costly for acquisition in India. Dedication of land for the installation of solar arrays must compete with other needs. The amount of land required for utility-scale solar power plants is about 1 km2 (250 acres) for every 40–60 MW generated. One alternative is to use the water-surface area on canals, lakes, reservoirs, farm ponds and the sea for large solar-power plants.[171][172][173] Due to better cooling of the solar panels and the sun tracking system, the output of solar panels is enhanced substantially.[174] These water bodies can also provide water to clean the solar panels.[175] Floating solar plants installation cost has reduced steeply by 2018.[176] In January 2019, Indian Railways announced the plan to install 4 GW capacity along its tracks.[177][178] Highways and railways may also avoid the cost of land nearer to load centres, minimising transmission-line costs by having solar plants about 10 meters above the roads or rail tracks.[179] Solar power generated by road areas may also be used for in-motion charging of electric vehicles, reducing fuel costs.[180] Highways would avoid damage from rain and summer heat, increasing comfort for commuters.[181][182][183]

The architecture best suited to most of India would be a set of rooftop power-generation systems connected via a local grid.[184] Not only the roof top area but also outer surface area of tall buildings can be used for solar PV power generation by installing PV modules in vertical position in place of glass panels to cover facade area.[185] Such an infrastructure, which does not have the economy of scale of mass, utility-scale solar-panel deployment, needs a lower deployment price to attract individuals and family-sized households. The cost of high efficiency and compact mono PERC modules and battery storage systems have reduced to make roof top solar PV more economical and feasible in a microgrid[186][156]

Greenpeace[11][187][188] recommends that India adopt a policy of developing solar power as a dominant component of its renewable-energy mix, since its identity as a densely-populated country[189] in the tropical belt[190][191] of the subcontinent has an ideal combination of high insolation[190] and a large potential consumer base.[192][193][194] In one scenario[188] India could make renewable resources the backbone of its economy by 2030, curtailing carbon emissions without compromising its economic-growth potential. A study suggested that 100 GW of solar power could be generated through a mix of utility-scale and rooftop solar, with the realizable potential for rooftop solar between 57 and 76 GW by 2024.[195]

During the 2015-16 fiscal year NTPC, with 110 MW solar power installations, generated 160.8 million kWh at a capacity utilisation of 16.64 percent (1,458 kWh per kW)—more than 20 percent below the claimed norms of the solar-power industry.[87] The annual net peak solar power generation is around 20,000 MW only (nearly 60% of name plate DC rating of 34,000 MW) after accounting the applicable derating factors and system losses before feeding in to the high voltage power grid since the name plate capacity of solar PV plants is actually the gross DC capacity of the installed PV modules.[196]

It is considered prudent to encourage solar-plant installations up to a threshold (such as 7,000 MW) by offering incentives.[197] Otherwise, substandard equipment with overrated nameplate capacity may tarnish the industry.[198][199] The purchaser, transmission agency and financial institution should require capacity utilisation and long-term performance guarantees for the equipment backed by insurance coverage in the event that the original equipment manufacturer ceases to exist.[200][201][202] Alarmed by the low quality of equipment, India issued draft quality guide lines in May 2017 to be followed by the solar plant equipment suppliers conforming to Indian standards.[203][204][205]

Government support

Fifty-one solar radiation resource assessment stations have been installed across India by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to create a database of solar-energy potential. Data is collected and reported to the Centre for Wind Energy Technology (C-WET) to create a solar atlas. In June 2015, India began a ₹40 crore (US$4.8 million) project to measure solar radiation with a spatial resolution of 3 by 3 kilometres (1.9 mi × 1.9 mi). This solar-radiation measuring network will provide the basis for the Indian solar-radiation atlas. According to National Institute of Wind Energy officials, the Solar Radiation Resource Assessment wing (121 ground stations) would measure solar radiation's three parameters—Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI), Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) and Diffuse Horizontal Irradiance (DHI)—to accurately measure a region's solar radiation.[206][207]

The Indian government is promoting solar energy. It announced an allocation of ₹1,000 crore (US$120 million) for the National Solar Mission and a clean-energy fund for the 2010-11 fiscal year, an increase of ₹380 crore (US$46 million) from the previous budget. The budget encouraged private solar companies by reducing the import duty on solar panels by five percent. This is expected to reduce the cost of a rooftop solar-panel installation by 15 to 20 percent.

Solar PV tariff

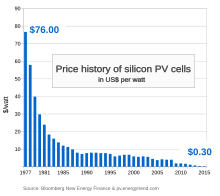

The average bid in reverse auctions in April 2017 is ₹3.15 (3.8¢ US) per kWh, compared with ₹12.16 (15¢ US) per kWh in 2010, which is around 73% drop over the time window.[211][212][213] The current prices of solar PV electricity is around 18% lower than the average price of electricity generated by coal-fired plants.[214] By the end of 2018, competitive reverse auctions, falling panel and component prices, the introduction of solar parks, lower borrowing costs and large power companies have contributed to the fall in prices.[215] The cost of solar PV power in India, China, Brazil and 55 other emerging markets fell to about one-third of its 2010 price, making solar the cheapest form of renewable energy and cheaper than power generated from fossil fuels such as coal and gas.[216]

India has the lowest capital cost per MW globally of installing solar power plants.[217] However the global levelized cost of solar PV electricity fell to 1.31¢ US per kWh (₹0.97 per kWh) in April 2020, much cheaper than the lowest solar PV tariff in India.[218][219][220][221] The intermittent / non-dispatchable solar PV at the prevailing low tariffs clubbed with Pumped-heat electricity storage can offer cheapest dispatchable power round the clock on demand.

The Indian government has reduced the solar PV power purchase price from the maximum allowed ₹4.43 (5.3¢ US) per KWh to ₹4.00 (4.8¢ US) per KWh, reflecting the steep fall in cost of solar power-generation equipment.[222][223][224] The applicable tariff is offered after applying viability gap funding (VGF) or accelerated depreciation (AD) incentives.[225][226] In January 2019, the time period for commissioning the solar power plants is reduced to 18 months for units located outside the solar parks and 15 months for units located inside the solar parks from the date of power purchase agreement.[227]

Solar PV generation cost fell to ₹2.97 (3.6¢ US) per kWh for the 750 MW Rewa Ultra Mega Solar power project, India's lowest electricity-generation cost.[228][229] In first quarter of calendar year 2020, large scale ground mounted solar power installations cost fell to Rs 35 million/MW by 12% in a year.[230] Solar panel prices are lower than those of mirrors by unit area.[139][231]

In an auction of 250 MW capacity of the second phase in Bhadla solar park, South Africa's Phelan Energy Group and Avaada Power were awarded 50 MW and 100 MW of capacity respectively in May 2017 at ₹2.62 (3.1¢ US) per kilowatt hour.[232] The tariff is also lower than NTPC's average coal power tariff of ₹3.20 per kilowatt hour. SBG Cleantech, a consortium of Softbank Group, Airtel and Foxconn, was awarded the remaining 100 MW capacity at a rate of ₹2.63 (3.2¢ US) per kWh.[233][234] Few days later in a second auction for another 500 MW at the same park, solar tariff has further fallen to ₹2.44 (2.9¢ US) per kilowatt hour which are the lowest tariffs for any solar power project in India.[235] These tariffs are lower than traded prices for day time in non-monsoon period in IEX and also for meeting peak loads on daily basis by using cheaper solar PV power in pumped-storage hydroelectricity stations indicating there is no need of any power purchase agreements and any incentives for the solar PV power plants in India.[236][237][238] Solar PV power plant developers are forecasting that solar power tariff would drop to ₹1.5 (1.8¢ US) /unit in near future.[239][208]

The lowest solar tariff in May 2018 is Rs 2.71/kWh (without incentives) which is less than the tariff of Bhadla solar park (₹2.44 per kWh with VGF incentive) after the clarification that any additional taxes are pass through cost with hike in the tariff.[240][241] In early July 2018 bids, the lowest solar PV tariff has touched ₹2.44 (2.9¢ US) per kWh without viability gap funding incentive.[242][243] In June 2019, The lowest tariff is ₹2.50 (3.0¢ US)/kWh for feeding in to the high voltage interstate transmission system (ISTS).[244][245][246]

The tariff for rooftop installations are also falling with the recent offer of ₹3.64 (4.4¢ US) with 100% locally made components.[247] In February 2019, the lowest solar power tariff is ₹1.24 (1.5¢ US) per kWh for 50 MW contracted capacity at Pavagada Solar Park.[248]

In May 2020, the discovered first year tariff is ₹2.90 (3.5¢ US) per KWh with ₹3.60 (4.3¢ US) per KWh levelized tariff for round the clock hybrid renewable power supply.[249] In June 2020, Solar PV power tariff has fallen to ₹2.36 (2.8¢ US) per KWh.[250]

Incentives

At the end of July 2015, the chief incentives were:

- Viability Gap Funding: Under the reverse bidding process, bidders who need least viability gap funding at the reference tariff (RS 4.93 per unit in 2016) is selected.[251] Funding was Rs 1 Crore/MW for open projects on average in 2016.

- Depreciation: For profit-making enterprises installing rooftop solar systems, 40 percent of the total investment could be claimed as depreciation in the first year (decreasing taxes).

- Liberal external commercial borrowing facility for the solar power plants.[252]

- To protect the local solar panel manufacturers, 25% safe guard duty is imposed for two years period from August 2018 on the imports from China & Malaysia who are suspected of dumping solar panels in to India.[253]

- Capital subsidies were applicable to rooftop solar-power plants up to a maximum of 500 kW. The 30-percent subsidy was reduced to 15 percent.

- Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs): Tradeable certificates providing financial incentives for every unit of green power generated.[254]

- Net metering incentives depend on whether a net meter is installed and the utility's incentive policy. If so, financial incentives are available for the power generated.[255]

- Assured Power Purchase Agreement (PPA): The power-distribution and -purchase companies owned by state and central governments guarantee the purchase of solar PV power when produced only during daylight. The PPAs offer fair market determined tariff for the solar power which is a secondary power or negative load and an intermittent energy source on a daily basis.

- Interstate transmission system (ISTS) charges and losses are not levied during the period of PPA for the projects commissioned before 31 March 2022.[256]

- Union government offers 70% and 30% subsidy for the hill states and other states respectively for the installation of rooftop solar units.[6] Additional incentives are offered to rooftop solar power plants from various state governments.[257][258]

Indian initiative of International solar alliance

In January 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and French President François Hollande laid the foundation stone for the headquarters of the International Solar Alliance (ISA) in Gwal Pahari, Gurgaon. The ISA will focus on promoting and developing solar energy and solar products for countries lying wholly or partially between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The alliance of over 120 countries was announced at the Paris COP21 climate summit.[259] One hope of the ISA is that wider deployment will reduce production and development costs, facilitating the increased deployment of solar technologies to poor and remote regions.

Solar-panel manufacturing in India

The 2018 manufacturing capacity of solar cells and solar modules in India was 1,590 MW and 5,620 MW, respectively.[260][261] Except for crystalline silicon wafers or cadmium telluride photovoltaics or Float-zone silicon, nearly 80 percent of solar-panel weight is flat glass.[262] 100-150 tons of flat glass is used to manufacture a MW of solar panels. Low-iron flat or float glass is manufactured from soda ash and iron-free silica. Soda-ash manufacturing from common salt is an energy-intensive process if it is not extracted from soda lakes or glasswort cultivation in alkali soil. To increase installation of photovoltaic solar-power plants, the production of flat glass and its raw materials must expand commensurately to eliminate supply constraints or future imports.[263]

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), India, has issued a memorandum to ensure the quality of solar cells and solar modules.[264][265] Compliance with the requisite specifications will grant manufacturers and their specific products an entry in the ALMM (Approved List of Models and Manufacturers.) [266][267][268] Indian manufacturers are gradually enhancing the production capacity of monocrystalline silicon PERC cells to supply better performing and enduring solar cells to local market.[186]

For utility scale solar projects, top solar module suppliers in 2016-17 were: Waaree energy ltd, Trina Solar, JA Solar, Canadian Solar, Risen, and Hanwha.[269]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Physical Progress (Achievements)". Ministry of New & Renewable Energy. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "India hits 20 GW solar capacity milestone". Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Krishna N. Das (2 January 2015). "India's Modi raises solar investment target to $100 bln by 2022". Reuters. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ a b "India releases state targets for 40GW rooftop solar by 2022". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "List of solar parks in India". Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b c "Renewable energy in India: why rooftop remains the most untapped solar source". Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Solar water pumps can help India surpass 100 GW target: Report". Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Annual Report 2015-2016". Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "MNRE Invites Proposals to Develop Institutional Framework for 'One Sun One World One Grid' Implementation". Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "India Set To Propose World Solar Bank & Mobilize $50 Billion In Solar Funding". Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Muneer, T.; Asif, M.; Munawwar, S. (2005). "Sustainable production of solar electricity with particular reference to the Indian economy". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 9 (5): 444. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2004.03.004. (publication archived in ScienceDirect, needs subscription or access via university)

- ^ "Solar". Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Govt. of India. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "How to calculate the annual solar energy output of a photovoltaic system?". Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Comprehensive technical data of PV modules". Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Goodbye Polycrystalline Solar Modules, Hello Mono PERC, HJT, Bifacial". Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Page 15, Solar power - Overview" (PDF). Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Status of Renewable Energy Power Projects Commissioned in AP State, NREDCAP" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "10,050 MW mega solar power plants to come up in two phases in Andhra Pradesh". Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Bid documents (6050 MW) submitted for judicial review (s.no. 6 to 15)". Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Kadiri ultra-mega solar park (4000 MW)" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Obuladevucheruvu ultra-mega solar park (2400MW)" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Ralla Anantapuram ultra-mega solar park (2400 MW)" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Badvel ultra-mega solar park (1400MW)" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Kalasapadu ultra-mega solar park (2000MW)" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Andhra Pradesh gov't approves 2.75GW solar-wind-pumped hydro project by Greenko". Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Interactive map showing the feasible locations of PSS projects in Andhra Pradesh state". Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Elon Musk Should Build Pumped Hydro With Tesla Energy, The Boring Co., & Coal Miners". Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ India, Press Trust of (10 May 2016). "Power generation begins at Kunta ultra mega solar project". Business Standard India. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "NTPC signs PPA for phase 1 of 1,000 mw ultra solar project with AP discoms". Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "The World's Largest Solar Park - Kurnool, India". Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Floating Solar Tender of 15 MW Announced by Greater Visakhapatnam Smart City". Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b "BHEL bags Rs 100-cr EPC order from NTPC to set up solar power plant". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Solar plant commissioned". Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Delhi: Multiple consumers can benefit from a single solar plant at one location". Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Pioneering and scaling up solar energy in India – webinar and related resources". The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership.

- ^ "Gujarat government buys solar power at Rs 15 per unit from 38 firms". 4 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Charanka Solar Park" (PDF). Ministry of New and Renewable Energy.

- ^ "Foreign players sweep Gujarat solar auction". Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ DiSPA Asks Haryana to Remove Upper Cap of 500 MW for Open Access Solar Projects, Dec 2018.

- ^ Haryana solar tender 300 mw, mercomindia.com, 4 January 2019.

- ^ Haryana Calls Developers to Set Up 16 MW of Canal Top Solar Projects, mercomindia.com, 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b "India's Top 10 Solar States in Charts". 17 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "World's Largest Solar Park at Karnataka's Pavagada is Now Fully Operational". Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "India's largest floating solar power plant opens in Kerala - Watt a sight!". The Economic Times. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "India's largest floating solar power plant opens in Kerala". Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Site decided, Govt clears mega solar project in Leh and Kargil". Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Solar Projects". Welspun Renewables. Welspun Renewables. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015., http://www.welspunenergy.com

- ^ "'Sure, pure and secure': PM Modi inaugurates Asia's largest solar plant in MP's Rewa". Hindustan Times. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ 9 Jul, TIMESOFINDIA COM /; 2020; Ist, 20:48. "PM Modi to inaugurate Asia's Second largest 750-MW Rewa solar plant tomorrow: All you need to know | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Electricity | District Rewa, Government of Madhya Pradesh | India". Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Shirdi Gets Largest Solar Cooking System".

- ^ "Shirdis solar cooker finds place". 30 July 2009.

- ^ "Shirdi Gets worlds largest solar steam system".

- ^ "India's solar capacity to cross 20GW in next 15 months: Piyush Goyal". Economic Times. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ "Reliance Power commissions world's largest Solar CSP project in Rajasthan". 12 November 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "ACME solar tower plant". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Lowest Quoted Tariff Dips to ₹2.48/kWh in SECI's 750 MW Solar Auction for Rajasthan". Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "Solar power tariff plunges to record low in Tamil Nadu". Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "NLC biggest winner in 1,500 Megawatt Tamil Nadu solar auction". Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "130-MW solar power plant commissioned at Neyveli". The Hindu. Cuddalore. 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b http://www.cea.nic.in/reports/monthly/executivesummary/2020/exe_summary-04.pdf

- ^ http://www.cea.nic.in/reports/monthly/executivesummary/2020/exe_summary-03.pdf

- ^ "Monthly Renewable Energy Generation, CEA" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Physical Progress (Achievements) | Ministry of New and Renewable Energy | Government of India". mnre.gov.in. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Plant wise details of Renewable Energy Installed Capacity" (PDF). Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Country's Biggest Solar Park In Rajasthan, At The Heart Of India's Clean Energy Push". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Solar plants of 620 MW get operational at Bhadla park Archived 3 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Times of India, 2 October 2018

- ^ "Azure Power commissions 150 Mw solar project in Rajasthan". Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "World's largest solar park in Karnataka is now fully operational". cnbctv18.com. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "The World's Largest Solar Park - Kurnool, India". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ NTPC commissioned 50 MW of NP Kunta Ultra Mega Solar Power Project Stage-I in Anantapuramu Archived 4 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, India Infoline News Service, 1 August 2016

- ^ "Solar Projects Totaling 127 MW Commissioned This Week". Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Tata Power commissions 100 MW solar power capacity in AP". Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ 750MW Madhya Pradesh solar plant starts operations, to serve Delhi Metro Archived 13 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The New Indian Express, 6 July 2018

- ^ "GIPCL commissions 75 MW solar power project in Gujarat". Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ India Pushes Ultra-Mega Scheme To Scale Solar PV Archived 26 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, William Pentland, 9 September 2014

- ^ "Gujarat riding on the suns chariot". Times of India. 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2019.</ref

- ^ "Solar plant commissioned". Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Ananthapuramu -II ultra mega solar park 500 MW - Land details". Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "SECI Refuses to Lower Tariffs for Andhra Solar Projects". Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "NTPC's Rs 1,500 crore solar power plant inaugurated by MP Chief Minister". Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "ENGIE fully commissions 250 MW Kadapa solar project in Andhra Pradesh". Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "List of projects that are part of Kadapa Mega Solar Park". Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Gujarat flips switch on Asia's largest solar field, leading India's renewable energy ambitions". Washington Post. New Delhi, India. 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Neemuch Solar Plant inaugurated by Narendra Modi and MP CM Shivraj Singh Chauhan". Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Telangana gets largest solar farm in Nizamabad district - Times of India".

- ^ a b "NTPC solar power plants performance". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Green Energy Corp to set up 50 mw Solar Power Plant". Odisha Sun Times. Bhubaneswar, India. 5 December 2013.

- ^ "NTPC's 50 MW solar power plant in Madhya Pradesh commissioned". Economic Times. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Welspun Energy commissions largest solar project". Economic Times. Jaipur, India. 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Odisha to float tenders soon for 48 MW solar power". Business Standard. Bhubaneswar, India. 30 December 2011.

- ^ "Adani Group commissions largest solar power project". Economic Times. New Delhi, India. 5 January 2012.

- ^ "Reliance Power to Buy First Solar Panels for U.S.-Backed Project". Bloomberg. India. 5 September 2011.

- ^ "Industry". 14 February 2013.

- ^ "Welspun Renewables commissions 34 MW solar project in Punjab".

- ^ "Moser Baer commissions 30-MW solar farm in Gujarat". The Hindu. 12 October 2011.

- ^ "Akhilesh launches 30MW solar plants in Lalitpur - Times of India".

- ^ Tata Power commissions 25MW solar project in Gujarat

- ^ "GEDCOL seeks land transfer for 20 Mw solar plant". Business Standard. Bhubaneswar, India. 1 April 2014.

- ^ "World-Bank Backed Azure Starts Up Solar-Power Plant in India". Bloomberg. 8 June 2011.

- ^ Bay Area News Group, Sunday 1 January 2012; Sun-drenched India sucks up the rays, author=Vikas Bajaj

- ^ MW scale Grid Solar Power Plants Commissioned in India

- ^ Green Infra

- ^ Surendranagar Solar Farm

- ^ Waaree Energies commissions 10 MW solar power plant Archived 12 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Maharashtra Projects

- ^ http://mercomcapital.com/solar-installations-in-india-to-reach-4.8-gw-in-2016-with-a-21-gw-development-pipeline

- ^ "Four States Accounted for 75 Percent of India's Utility-Scale Solar Installations in 2017". 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Safi, Michael. "India's huge solar ambitions could push coal further into shade". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "DOE Energy storage database". Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Concentrating Solar Power Isn't Viable Without Storage, Say Experts". November 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "SECI Issues Tender for 5 GW of Round-the-Clock Renewable Power Bundled with Thermal". Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Adani Quotes Lowest Tariff of ₹2.69/kWh in SECI's 1.2 GW Solar-Wind Hybrid Auction". Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ "SB Energy and Adani Green win 840 MW at hybrid auction". Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Siemens Gamesa bags Wind-Solar hybrid energy project in Karnataka". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Shapoorji Pallonji bags country's first large-scale floating solar project". Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "Integrated Solar-Hydro Project Takes Float". September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Floating Solar On Pumped Hydro, Part 1: Evaporation Management Is A Bonus". Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "India Allocates 1.2 Gigawatts In World's Largest Renewable Energy Storage Tender". Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Aurora: What you should know about Port Augusta's solar power-tower". 21 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Cheap Baseload Solar At Copiapó Gets OK In Chile". 25 August 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Controllable solar power – competitively priced for the first time in North Africa". Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Lewis, Dyani (5 April 2017). "Salt, silicon or graphite: energy storage goes beyond lithium ion batteries". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Commercializing Standalone Thermal Energy Storage". Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The sleeping giant is waking up". 29 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Solar thermal industry seeks govt attention". 13 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "Solar Water Heater". Dnaindia.com. 28 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Solar Water Heater Rebate". The Hindu. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Dipannita Das (29 November 2009). "More homes opt for solar energy". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "PVT panels". Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "DC solar products are lighting up rural India: What's driving the increased demand?". Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Roul, Avilash (15 May 2007). "India's Solar Power: Greening India's Future Energy Demand". Ecoworld.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Can India Provide Free Solar-Powered Irrigation To All Its Farmers?". Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Upadhyay, Anindya (3 January 2015). "China's cheap solar panels cause dark spots in Indian market". The Economic Times. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Solar power in 3,000 Odisha villages by 2014". Newkerala.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "The Orissa Renewable Energy Development Agency (OREDA) was constituted as a State Nodal agency in the 1984". Oredaorissa.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "The Energy Business – India Energy News, Nuclear Energy News, Renewable Energy News, Oil & Gas Sector News, Power Sector News " Orissa approves nine solar power projects". Energybusiness.in. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Government Provides 30% subsidy for Solar Lanterns and Home Lights

- ^ Action Plan to Increase Renewable Energy

- ^ a b "Indian Module Makers Beat Chinese Prices In 300 Megawatt Tender". 23 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ "Over 181,000 Solar Water Pumps Installed in India". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ "Budget 2020: Govt expands PM KUSUM scheme for solar pumps, targets to cover 20 lakh farmers". Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "How hot do solar panels get? Effect of temperature on solar performance". 15 June 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Driving synergy in energy and agriculture through Agro-Photovoltaics". Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Solar chilli drier". 1 September 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Meet this engineering student from Pune who has built a solar powered bicycle". Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Rain fed solar-powered water purification systems". Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "New rooftop solar hydro panels harvest drinking water and energy at the same time". Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Inverted Umbrella Brings Clean Water & Clean Power To India". 4 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Now, solar energy can power air conditioner, refrigerator". Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "Thin Film Solar PV vs Silicon Wafer – Which is Better?". Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Panasonic HIT solar module achieves world's best output temperature coefficient". 22 June 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "The use of solar trackers is picking up fast in India". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ "Bifacial Plus Tracking Boosts Solar Energy Yield by 27 Percent". 18 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Sengupta, Debjoy (19 October 2016). "Rs 3 per KWh – lowest tariff for third-party rooftop solar power installations". The Economic Times. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Giving electric vehicle batteries a second life in solar projects". 20 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ a b "The Death Of The World's Most Popular Battery". Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "AES Energy Storage and Panasonic Target India for Grid Batteries". Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Frequency Profile, NLDC, GoI". Retrieved 6 August 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "India Plans 750 MW Solar Power Park With 100 MW Storage Capacity". 25 February 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Real Time DSM tariff". Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ "Deviation Settlement Mechanism and related matters, CERC, GoI" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ "Rays Future Energy executes 60 MW of capacity under open access". Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Audi claims to be buying batteries at ~$114/kWh for its upcoming electric cars, says CTO". 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Global Solar Storage Market: A Review Of 2015". 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Storing The Sun's Energy Just Got A Whole Lot Cheaper". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Los Angeles seeks record sub-two cent solar power price". Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Solar and wind now the cheapest power source says Bloomberg NEF". Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "Energy storage already cost-competitive in commercial sector". 30 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Construction power tariff" (PDF). 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Construction Site Power and Lighting". 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Floating solar energy transforming India into a greener nation". Retrieved 31 October 2018.