Batman

It has been suggested that Batman (Jace Fox) be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2024. |

| Batman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

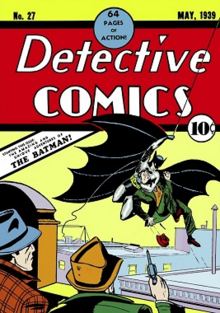

| First appearance | Detective Comics #27 (cover-dated May 1939; published March 30, 1939)[1] |

| Created by | |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Bruce Wayne |

| Place of origin | Gotham City |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities |

|

Batman[a] is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in the 27th issue of the comic book Detective Comics on March 30, 1939. In the DC Universe continuity, Batman is the alias of Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American playboy, philanthropist, and industrialist who resides in Gotham City. Batman's origin story features him swearing vengeance against criminals after witnessing the murder of his parents Thomas and Martha as a child, a vendetta tempered with the ideal of justice. He trains himself physically and intellectually, crafts a bat-inspired persona, and monitors the Gotham streets at night. Kane, Finger, and other creators accompanied Batman with supporting characters, including his sidekicks Robin and Batgirl; allies Alfred Pennyworth, James Gordon, and love interest Catwoman; and foes such as the Penguin, the Riddler, Two-Face, and his archenemy, the Joker.

DC has featured Batman in many comic books, including comics published under its imprints such as Vertigo and Black Label. The longest-running Batman comic, Detective Comics, is the longest-running comic book in the United States. Batman is frequently depicted alongside other DC superheroes, such as Superman and Wonder Woman, as a member of organizations such as the Justice League and the Outsiders. In addition to Bruce Wayne, other characters have taken on the Batman persona on different occasions, such as Jean-Paul Valley / Azrael in the 1993–1994 "Knightfall" story arc; Dick Grayson, the first Robin, from 2009 to 2011; and Jace Fox, son of Wayne's ally Lucius, as of 2021.[4] DC has also published comics featuring alternate versions of Batman, including the incarnation seen in The Dark Knight Returns and its successors, the incarnation from the Flashpoint (2011) event, and numerous interpretations from Elseworlds stories.

One of the most iconic characters in popular culture, Batman has been listed among the greatest comic book superheroes and fictional characters ever created. He is one of the most commercially successful superheroes, and his likeness has been licensed and featured in various media and merchandise sold around the world; this includes toy lines such as Lego Batman and video games like the Batman: Arkham series. Batman has been adapted in live-action and animated incarnations, including the 1960s Batman television series played by Adam West and in film by Michael Keaton in Batman (1989), Batman Returns (1992), and The Flash (2023), Val Kilmer in Batman Forever (1995), George Clooney in Batman & Robin (1997), Christian Bale in The Dark Knight trilogy (2005–2012), Ben Affleck in the DC Extended Universe (2016–2023), and Robert Pattinson in The Batman (2022). Many actors, most prolifically Kevin Conroy, have provided the character's voice in animation and video games.

Publication history

Creation

In early 1939, the success of Superman in Action Comics prompted editors at National Comics Publications (the future DC Comics) to request more superheroes for its titles. In response, Bob Kane created "the Bat-Man".[6] Collaborator Bill Finger recalled that "Kane had an idea for a character called 'Batman,' and he'd like me to see the drawings. I went over to Kane's, and he had drawn a character who looked very much like Superman with kind of ...reddish tights, I believe, with boots ...no gloves, no gauntlets ...with a small domino mask, swinging on a rope. He had two stiff wings that were sticking out, looking like bat wings. And under it was a big sign ...BATMAN".[7] According to Kane, the bat-wing-like cape was inspired by his childhood recollection of Leonardo da Vinci's sketch of an ornithopter flying device.[8]

Finger suggested giving the character a cowl instead of a simple domino mask, a cape instead of wings, and gloves; he also recommended removing the red sections from the original costume.[9][10][11][12] Finger said he devised the name Bruce Wayne for the character's secret identity: "Bruce Wayne's first name came from Robert the Bruce, the Scottish patriot. Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock ...then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne."[13] He later said his suggestions were influenced by Lee Falk's popular The Phantom, a syndicated newspaper comic-strip character with which Kane was also familiar.[14]

Kane and Finger drew upon contemporary 1930s popular culture for inspiration regarding much of the Bat-Man's look, personality, methods, and weaponry. Details find predecessors in pulp fiction, comic strips, newspaper headlines, and autobiographical details referring to Kane himself.[15] As an aristocratic hero with a double identity, Batman has predecessors in the Scarlet Pimpernel (created by Baroness Emmuska Orczy, 1903) and Zorro (created by Johnston McCulley, 1919). Like them, Batman performs his heroic deeds in secret, averts suspicion by playing aloof in public, and marks his work with a signature symbol. Kane noted the influence of the films The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Bat Whispers (1930) in the creation of the character's iconography. Finger, drawing inspiration from pulp heroes like Doc Savage, The Shadow, Dick Tracy, and Sherlock Holmes, made the character a master sleuth.[16][17]

In his 1989 autobiography, Kane detailed Finger's contributions to Batman's creation:

One day I called Bill and said, 'I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I've made some crude, elementary sketches I'd like you to look at.' He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman's face. Bill said, 'Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?' At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit; the wings, trunks, and mask were black. I thought that red and black would be a good combination. Bill said that the costume was too bright: 'Color it dark grey to make it look more ominous.' The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to his arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized that these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope. Also, he didn't have any gloves on, and we added them so that he wouldn't leave fingerprints.[14]

Subsequent creation credit

Kane signed away ownership in the character in exchange for, among other compensation, a mandatory byline on all Batman comics. This byline did not originally say "Batman created by Bob Kane"; his name was simply written on the title page of each story. The name disappeared from the comic book in the mid-1960s, replaced by credits for each story's actual writer and artists. In the late 1970s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster began receiving a "created by" credit on the Superman titles, along with William Moulton Marston being given the byline for creating Wonder Woman, Batman stories began saying "Created by Bob Kane" in addition to the other credits.

Finger did not receive the same recognition. While he had received credit for other DC work since the 1940s, he began, in the 1960s, to receive limited acknowledgment for his Batman writing; in the letters page of Batman #169 (February 1965) for example, editor Julius Schwartz names him as the creator of the Riddler, one of Batman's recurring villains. However, Finger's contract left him only with his writing page rate and no byline. Kane wrote, "Bill was disheartened by the lack of major accomplishments in his career. He felt that he had not used his creative potential to its fullest and that success had passed him by."[13] At the time of Finger's death in 1974, DC had not officially credited Finger as Batman co-creator.

Jerry Robinson, who also worked with Finger and Kane on the strip at this time, has criticized Kane for failing to share the credit. He recalled Finger resenting his position, stating in a 2005 interview with The Comics Journal:

Bob made him more insecure, because while he slaved working on Batman, he wasn't sharing in any of the glory or the money that Bob began to make, which is why ...[he was] going to leave [Kane's employ]. ...[Kane] should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there. ...That was one thing I would never forgive Bob for, was not to take care of Bill or recognize his vital role in the creation of Batman. As with Siegel and Shuster, it should have been the same, the same co-creator credit in the strip, writer, and artist.[18]

Although Kane initially rebutted Finger's claims at having created the character, writing in a 1965 open letter to fans that "it seemed to me that Bill Finger has given out the impression that he and not myself created the ''Batman, t' [sic] as well as Robin and all the other leading villains and characters. This statement is fraudulent and entirely untrue." Kane himself also commented on Finger's lack of credit. "The trouble with being a 'ghost' writer or artist is that you must remain rather anonymously without 'credit'. However, if one wants the 'credit', then one has to cease being a 'ghost' or follower and become a leader or innovator."[19]

In 1989, Kane revisited Finger's situation, recalling in an interview:

In those days it was like, one artist and he had his name over it [the comic strip] — the policy of DC in the comic books was, if you can't write it, obtain other writers, but their names would never appear on the comic book in the finished version. So Bill never asked me for it [the byline] and I never volunteered — I guess my ego at that time. And I felt badly, really, when he [Finger] died.[20]

In September 2015, DC Entertainment revealed that Finger would be receiving credit for his role in Batman's creation on the 2016 superhero film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and the second season of Gotham after a deal was worked out between the Finger family and DC.[2] Finger received credit as a creator of Batman for the first time in a comic in October 2015 with Batman and Robin Eternal #3 and Batman: Arkham Knight Genesis #3. The updated acknowledgment for the character appeared as "Batman created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger".[3]

Golden Age

Early years

The first Batman story, "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate", was published in Detective Comics #27 (cover dated May 1939). It largely duplicated the plot of the story "Partners of Peril" in The Shadow #113, which was written by Theodore Tinsley and illustrated by Tom Lovell.[21] Finger said, "Batman was originally written in the style of the pulps",[22] and this influence was evident with Batman showing little remorse over killing or maiming criminals. Batman proved a hit character, and he received his own solo title in 1940 while continuing to star in Detective Comics. By that time, Detective Comics was the top-selling and most influential publisher in the industry; Batman and the company's other major hero, Superman, were the cornerstones of the company's success.[23] The two characters were featured side by side as the stars of World's Finest Comics, which was originally titled World's Best Comics when it debuted in fall 1940. Creators including Jerry Robinson and Dick Sprang also worked on the strips during this period.

Over the course of the first few Batman strips elements were added to the character and the artistic depiction of Batman evolved. Kane noted that within six issues he drew the character's jawline more pronounced, and lengthened the ears on the costume. "About a year later he was almost the full figure, my mature Batman", Kane said.[24] Batman's characteristic utility belt was introduced in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939), followed by the boomerang-like batarang and the first bat-themed vehicle, the Batplane, in #31 (September 1939). The character's origin was revealed in #33 (November 1939), unfolding in a two-page story that establishes the brooding persona of Batman, a character driven by the death of his parents. Written by Finger, it depicts a young Bruce Wayne witnessing his parents' murder at the hands of a mugger. Days later, at their grave, the child vows that "by the spirits of my parents [I will] avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals".[25][26][27]

The early, pulp-inflected portrayal of Batman started to soften in Detective Comics #38 (April 1940) with the introduction of Robin, Batman's junior counterpart.[28] Robin was introduced, based on Finger's suggestion, because Batman needed a "Watson" with whom Batman could talk.[29] Sales nearly doubled, despite Kane's preference for a solo Batman, and it sparked a proliferation of "kid sidekicks".[30] The first issue of the solo spin-off series Batman was notable not only for introducing two of his most persistent enemies, the Joker and Catwoman, but for a pre-Robin inventory story, originally meant for Detective Comics #38, in which Batman shoots some monstrous giants to death.[31][32] That story prompted editor Whitney Ellsworth to decree that the character could no longer kill or use a gun.[33]

By 1942, the writers and artists behind the Batman comics had established most of the basic elements of the Batman mythos.[34] In the years following World War II, DC Comics "adopted a postwar editorial direction that increasingly de-emphasized social commentary in favor of lighthearted juvenile fantasy". The impact of this editorial approach was evident in Batman comics of the postwar period; removed from the "bleak and menacing world" of the strips of the early 1940s, Batman was instead portrayed as a respectable citizen and paternal figure that inhabited a "bright and colorful" environment.[35]

Silver and Bronze Ages

1950s and early 1960s

Batman was one of the few superhero characters to be continuously published as interest in the genre waned during the 1950s. In the story "The Mightiest Team in the World" in Superman #76 (June 1952), Batman teams up with Superman for the first time and the pair discover each other's secret identity.[36] Following the success of this story, World's Finest Comics was revamped so it featured stories starring both heroes together, instead of the separate Batman and Superman features that had been running before.[37] The team-up of the characters was "a financial success in an era when those were few and far between";[38] this series of stories ran until the book's cancellation in 1986.

Batman comics were among those criticized when the comic book industry came under scrutiny with the publication of psychologist Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent in 1954. Wertham's thesis was that children imitated crimes committed in comic books, and that these works corrupted the morals of the youth. Wertham criticized Batman comics for their supposed homosexual overtones and argued that Batman and Robin were portrayed as lovers.[39] Wertham's criticisms raised a public outcry during the 1950s, eventually leading to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, a code that is no longer in use by the comic book industry. The tendency towards a "sunnier Batman" in the postwar years intensified after the introduction of the Comics Code.[40] Scholars have suggested that the characters of Batwoman (in 1956) and the pre-Barbara Gordon Bat-Girl (in 1961) were introduced in part to refute the allegation that Batman and Robin were gay, and the stories took on a campier, lighter feel.[41]

In the late 1950s, Batman stories gradually became more science fiction-oriented, an attempt at mimicking the success of other DC characters that had dabbled in the genre.[42] New characters such as Batwoman, the original Bat-Girl, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were introduced. Batman's adventures often involved odd transformations or bizarre space aliens. In 1960, Batman debuted as a member of the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold #28 (February 1960), and went on to appear in several Justice League comic book series starting later that same year.

"New Look" Batman and camp

By 1964, sales of Batman titles had fallen drastically. Bob Kane noted that, as a result, DC was "planning to kill Batman off altogether".[43] In response to this, editor Julius Schwartz was assigned to the Batman titles. He presided over drastic changes, beginning with 1964's Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), which was cover-billed as the "New Look". Schwartz introduced changes designed to make Batman more contemporary, and to return him to more detective-oriented stories. He brought in artist Carmine Infantino to help overhaul the character. The Batmobile was redesigned, and Batman's costume was modified to incorporate a yellow ellipse behind the bat-insignia. The space aliens, time travel, and characters of the 1950s such as Batwoman, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were retired. Bruce Wayne's butler Alfred was killed off (though his death was quickly reversed) while a new female relative for the Wayne family, Aunt Harriet Cooper, came to live with Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson.[44]

The debut of the Batman television series in 1966 had a profound influence on the character. The success of the series increased sales throughout the comic book industry, and Batman reached a circulation of close to 900,000 copies.[45] Elements such as the character of Batgirl and the show's campy nature were introduced into the comics; the series also initiated the return of Alfred. Although both the comics and TV show were successful for a time, the camp approach eventually wore thin and the show was canceled in 1968. In the aftermath, the Batman comics themselves lost popularity once again. As Julius Schwartz noted, "When the television show was a success, I was asked to be campy, and of course when the show faded, so did the comic books."[46]

Starting in 1969, writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Neal Adams made a deliberate effort to distance Batman from the campy portrayal of the 1960s TV series and to return the character to his roots as a "grim avenger of the night".[47] O'Neil said his idea was "simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after."[48]

O'Neil and Adams first collaborated on the story "The Secret of the Waiting Graves" in Detective Comics #395 (January 1970). Few stories were true collaborations between O'Neil, Adams, Schwartz, and inker Dick Giordano, and in actuality these men were mixed and matched with various other creators during the 1970s; nevertheless the influence of their work was "tremendous".[49] Giordano said: "We went back to a grimmer, darker Batman, and I think that's why these stories did so well ..."[50] While the work of O'Neil and Adams was popular with fans, the acclaim did little to improve declining sales; the same held true with a similarly acclaimed run by writer Steve Englehart and penciler Marshall Rogers in Detective Comics #471–476 (August 1977 – April 1978), which went on to influence the 1989 movie Batman and be adapted for Batman: The Animated Series, which debuted in 1992.[51] Regardless, circulation continued to drop through the 1970s and 1980s, hitting an all-time low in 1985.[52]

Modern Age

The Dark Knight Returns

Frank Miller's limited series The Dark Knight Returns (February–June 1986) returned the character to his darker roots, both in atmosphere and tone. The comic book, which tells the story of a 55-year-old Batman coming out of retirement in a possible future, reinvigorated interest in the character. The Dark Knight Returns was a financial success and has since become one of the medium's most noted touchstones.[53] The series also sparked a major resurgence in the character's popularity.[54]

That year Dennis O'Neil took over as editor of the Batman titles and set the template for the portrayal of Batman following DC's status quo-altering 12-issue miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths. O'Neil operated under the assumption that he was hired to revamp the character and as a result tried to instill a different tone in the books than had gone before.[55] One outcome of this new approach was the "Year One" storyline in Batman #404–407 (February–May 1987), in which Frank Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli redefined the character's origins.[56] Writer Alan Moore and artist Brian Bolland continued this dark trend with 1988's 48-page one-shot issue Batman: The Killing Joke, in which the Joker, attempting to drive Commissioner Gordon insane, cripples Gordon's daughter Barbara, and then kidnaps and tortures the commissioner, physically and psychologically.[57]

The Batman comics garnered major attention in 1988 when DC Comics created a 900 number for readers to call to vote on whether Jason Todd, the second Robin, lived or died. Voters decided in favor of Jason's death by a narrow margin of 28 votes (see Batman: A Death in the Family).[56]

Knightfall

The 1993 "Knightfall" story arc introduced a new villain, Bane, who critically injures Batman after pushing him to the limits of his endurance. Jean-Paul Valley, known as Azrael, is called upon to wear the Batsuit during Bruce Wayne's convalescence. Writers Doug Moench, Chuck Dixon, and Alan Grant worked on the Batman titles during "Knightfall", and would also contribute to other Batman crossovers throughout the 1990s. 1998's "Cataclysm" storyline served as the precursor to 1999's "No Man's Land", a year-long storyline that ran through all the Batman-related titles dealing with the effects of an earthquake-ravaged Gotham City. At the conclusion of "No Man's Land", O'Neil stepped down as editor and was replaced by Bob Schreck.[58]

Another writer who rose to prominence on the Batman comic series, was Jeph Loeb. Along with longtime collaborator Tim Sale, they wrote two miniseries (The Long Halloween and Dark Victory) that pit an early-in-his-career version of Batman against his entire rogues gallery (including Two-Face, whose origin was re-envisioned by Loeb) while dealing with various mysteries involving serial killers Holiday and the Hangman.

21st century

Hush and Under the Hood

In 2003, Loeb teamed with artist Jim Lee to work on another mystery arc: "Batman: Hush" for the main Batman book. The 12–issue story line has Batman and Catwoman teaming up against Batman's entire rogues gallery, including an apparently resurrected Jason Todd, while seeking to find the identity of the mysterious supervillain Hush.[59] While the character of Hush failed to catch on with readers, the arc was a sales success for DC. The series became #1 on the Diamond Comic Distributors sales chart for the first time since Batman #500 (October 1993) and Todd's appearance laid the groundwork for writer Judd Winick's subsequent run as writer on Batman, with another multi-issue arc, "Under the Hood", which ran from Batman #637–650 (April 2005 – April 2006).

All Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder

In 2005, DC launched All Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder, a stand-alone comic book miniseries set outside the main DC Universe continuity. Written by Frank Miller and drawn by Jim Lee, the series was a commercial success for DC Comics,[60][61] although it was widely panned by critics for its writing, characterization, and strong depictions of violence.[62][63]

Grant Morrison's Batman Run

Starting in 2006, Grant Morrison and Paul Dini were the regular writers of Batman and Detective Comics, with Morrison reincorporating controversial elements of Batman lore. Most notably of these elements were the science fiction-themed storylines of the 1950s Batman comics, which Morrison revised as hallucinations Batman experienced under the influence of various mind-bending gases and extensive sensory deprivation training. In Batman and Son, Morrison re-introduced the son of Bruce Wayne and Talia Al Ghul, Damian Wayne, to continuity, who had been raised by his mother in the League of Assassins. A son of Wayne and Al Ghul had previously appeared as an infant in the non-canon Son of the Demon. In the storyline The Three Ghosts of Batman, Morrison expanded upon the gun-wielding imposter Batman from his first issue on the series, introducing two more imposter Batmen, all former police officers.[64][65] Morrison created an apocalyptic possible future in Batman #666, where Damian Wayne has adopted the role of Batman following his father's death, but unlike Bruce Wayne, having no issue with killing criminals. Following this story, Morrison reintroduced a number of Silver Age characters such as Knight and Squire, El Gaucho, and Man of Bats in The Batmen of All Nations, laying the groundwork for their future work on Batman Incorporated.

The New 52

In September 2011, DC Comics' entire line of superhero comic books, including its Batman franchise, were cancelled and relaunched with new #1 issues as part of The New 52 reboot. Bruce Wayne is the only character to operate under the Batman identity and is featured in Batman, Detective Comics, Batman and Robin, and Batman: The Dark Knight. Dick Grayson returns to the mantle of Nightwing and appears in his own ongoing series. While many characters have their histories significantly altered to attract new readers, Batman's history remained mostly intact.

Batman Incorporated was relaunched in 2012 to complete Grant Morrison's "Leviathan" storyline . It also contextualized the possible future of Batman #666 as a vision Bruce Wayne experienced while travelling through time following Final Crisis, and reached its conclusion in 2013. The final act of Morrison's run reached its emotional climax with the death of Damian Wayne at the hands of his evil clone, the Heretic. The run concluded with Leviathan's plan to destroy the world thwarted by the members of Batman Incorporated, the reveal that Kathy Kane was alive and working for the organization Spyral, and the death of Talia Al Ghul at Kane's hands. In the final pages of issue #13, Ra's Al Ghul stands in a room of clones of Damian Wayne, declaring "Sons of Batman. Rise!", which would be touched on in Peter Tomasi's Batman and Robin soon after.

With the beginning of The New 52, Scott Snyder took over as writer of the Batman title. His first major story arc was "Night of the Owls", where Batman confronts the Court of Owls, a secret society that has controlled Gotham for centuries. It was followed by Batman vol. 2 #0, published in June 2012, a brief flashback to Zero Year, teasing the upcoming Zero Year arc. The second story arc was "Death of the Family", in which the Joker returns to Gotham and attacks each member of the Batman family in an attempt to prove Batman's extended cast makes the character weaker.

The third story arc was "Batman: Zero Year", which redefined Batman's origin in The New 52, replacing the previous Year One storyline. The final story before the Convergence (2015) storyline was "Endgame", depicting the supposed final battle between Batman and the Joker when he unleashes the deadly Endgame virus onto Gotham City. The storyline ends in issue #40 with Batman and Joker's apparent deaths.

Starting with Batman vol. 2 #41, Commissioner James Gordon takes over Bruce's mantle as a new, state-sanctioned, robotic-Batman, debuting in the Free Comic Book Day special comic Divergence. However, Bruce Wayne is soon revealed to be alive, albeit now with almost total amnesia of his life as Batman, but, with Alfred's help, remembers his life as Bruce Wayne. Bruce Wayne finds happiness and proposes to his girlfriend, Julie Madison, but Mr. Bloom heavily injures Jim Gordon and takes control of Gotham City and threatens to destroy the city by energizing a particle reactor to create a "strange star" to swallow the city. Bruce Wayne discovers the truth that he was Batman and after talking to a stranger who smiles a lot (it is heavily implied that this is the amnesic Joker) he forces Alfred to implant his memories as Batman, but at the cost of his memories as the reborn Bruce Wayne. He returns and helps Jim Gordon defeat Mr. Bloom and shut down the reactor. Gordon gets his job back as the commissioner, and the government Batman project is shut down.[66]

In 2015, DC Comics released The Dark Knight III: The Master Race, the sequel to Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Again.[67]

DC Rebirth and Infinite Frontier

In June 2016, the DC Rebirth event relaunched DC Comics' entire line of comic book titles. Batman was rebooted as starting with a one-shot issue entitled Batman: Rebirth #1 (August 2016). The series then began shipping twice-monthly as a third volume, starting with Batman vol. 3 #1 (August 2016). The third volume of Batman was written by Tom King, and artwork was provided by David Finch and Mikel Janín. The Batman series introduced two vigilantes, Gotham and Gotham Girl. Detective Comics resumed its original numbering system starting with June 2016's #934, and the New 52 series was labeled as volume 2, with issues numbering from #0-52.[68] Similarly with the Batman title, the New 52 issues were labeled as volume 2 and encompassed issues #0-52. Writer James Tynion IV and artists Eddy Barrows and Alvaro Martinez worked on Detective Comics #934, and the series initially featured a team consisting of Tim Drake, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, and Clayface, led by Batman and Batwoman.

DC Comics ended the DC Rebirth branding in December 2017, opting to include everything under a larger DC Universe banner and naming. The continuity established by DC Rebirth continues across DC's comic book titles, including volume 1 of Detective Comics and volume 3 of Batman.[69][70]

After the conclusion of Batman vol. 3 #85[71] a new creative team consisting of James Tynion IV with art by Tony S. Daniel and Danny Miki replaced Tom King, David Finch and Mikel Janín. Following Tynion's departure from DC Comics, Joshua Williamson, who previously wrote the backup story in issue #106, briefly became the new head writer in December 2021 starting with issue #118.[72] Chip Zdarsky then became the head writer with artist Jorge Jimenez returning after having previously illustrated parts of Tynion's run. Their run begun with issue #125, which was released on July 5, 2022 and starts with "Failsafe", a six-issue story arc.[73]

Characterization

Bruce Wayne

Batman's secret identity is Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American industrialist. As a child, Bruce witnessed the murder of his parents, Dr. Thomas Wayne and Martha Wayne, which ultimately led him to craft the Batman persona and seek justice against criminals. He resides on the outskirts of Gotham City in his personal residence, Wayne Manor. Wayne averts suspicion by acting the part of a superficial playboy idly living off his family's fortune and the profits of Wayne Enterprises, his inherited conglomerate.[74][75] He supports philanthropic causes through his nonprofit Wayne Foundation, which in part addresses social issues encouraging crime as well as assisting victims of it, but is more widely known as a celebrity socialite.[76] In public, he frequently appears in the company of high-status women, which encourages tabloid gossip while feigning near-drunkenness with consuming large quantities of disguised ginger ale since Wayne is actually a strict teetotaler to maintain his physical and mental prowess.[77] Although Bruce Wayne leads an active romantic life, his vigilante activities as Batman account for most of his time.[78]

Various modern stories have portrayed the extravagant, playboy image of Bruce Wayne as a facade.[79] This is in contrast to the Post-Crisis Superman, whose Clark Kent persona is the true identity, while the Superman persona is the facade.[80][81] In Batman Unmasked, a television documentary about the psychology of the character, behavioral scientist Benjamin Karney notes that Batman's personality is driven by Bruce Wayne's inherent humanity; that "Batman, for all its benefits and for all of the time Bruce Wayne devotes to it, is ultimately a tool for Bruce Wayne's efforts to make the world better". Bruce Wayne's principles include the desire to prevent future harm and a vow not to kill. Bruce Wayne believes that our actions define us, we fail for a reason, and anything is possible.[82]

Writers of Batman and Superman stories have often compared and contrasted the two. Interpretations vary depending on the writer, the story, and the timing. Grant Morrison[83] notes that both heroes "believe in the same kind of things" despite the day/night contrast their heroic roles display. Morrison notes an equally stark contrast in their real identities. Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent belong to different social classes: "Bruce has a butler, Clark has a boss." T. James Musler's book Unleashing the Superhero in Us All explores the extent to which Bruce Wayne's vast personal wealth is important in his life story, and the crucial role it plays in his efforts as Batman.[84]

Will Brooker notes in his book Batman Unmasked that "the confirmation of the Batman's identity lies with the young audience ...he doesn't have to be Bruce Wayne; he just needs the suit and gadgets, the abilities, and most importantly the morality, the humanity. There's just a sense about him: 'they trust him ...and they're never wrong."[85]

Personality

Batman's primary character traits can be summarized as "wealth; physical prowess; deductive abilities and obsession".[86] The details and tone of Batman comic books have varied over the years with different creative teams. Dennis O'Neil noted that character consistency was not a major concern during early editorial regimes: "Julie Schwartz did a Batman in Batman and Detective and Murray Boltinoff did a Batman in the Brave and the Bold and apart from the costume they bore very little resemblance to each other. Julie and Murray did not want to coordinate their efforts, nor were they asked to do so. Continuity was not important in those days."[87]

The driving force behind Bruce Wayne's character is his parents' murder and their absence. Bob Kane and Bill Finger discussed Batman's background and decided that "there's nothing more traumatic than having your parents murdered before your eyes".[88] Despite his trauma, he sets his mind on studying to become a scientist[89][90] and to train his body into physical perfection[89][90] to fight crime in Gotham City as Batman, an inspired idea from Wayne's insight into the criminal mind.[89][90] He also speaks over 40 languages.[91]

Another of Batman's characterizations is that of a vigilante; in order to stop evil that started with the death of his parents, he must sometimes break the law himself. Although manifested differently by being re-told by different artists, it is nevertheless that the details and the prime components of Batman's origin have never varied at all in the comic books, the "reiteration of the basic origin events holds together otherwise divergent expressions".[92] The origin is the source of the character's traits and attributes, which play out in many of the character's adventures.[86]

Batman is often treated as a vigilante by other characters in his stories. Frank Miller views the character as "a dionysian figure, a force for anarchy that imposes an individual order".[93] Dressed as a bat, Batman deliberately cultivates a frightening persona in order to aid him in crime-fighting,[94] a fear that originates from the criminals' own guilty conscience.[95] Miller is often credited with reintroducing anti-heroic traits into Batman's characterization,[96] such as his brooding personality, willingness to use violence and torture, and increasingly alienated behavior. Batman, shortly a year after his debut and the introduction of Robin, was changed in 1940 after DC editor Whitney Ellsworth felt the character would be tainted by his lethal methods and DC established their own ethical code, subsequently he was retconned to have a stringent moral code,[33][97] which has stayed with the character of Batman ever since. Miller's Batman was closer to the original pre-Robin version, who was willing to kill criminals if necessary.[98]

Others

On several occasions former Robin Dick Grayson has served as Batman; most notably in 2009 while Wayne was believed dead, and served as a second Batman even after Wayne returned in 2010.[59] As part of DC's 2011 continuity relaunch, Grayson returned to being Nightwing following the Flashpoint crossover event.

In an interview with IGN, Morrison detailed that having Dick Grayson as Batman and Damian Wayne as Robin represented a "reverse" of the normal dynamic between Batman and Robin, with, "a more light-hearted and spontaneous Batman and a scowling, badass Robin". Morrison explained their intentions for the new characterization of Batman: "Dick Grayson is kind of this consummate superhero. The guy has been Batman's partner since he was a kid, he's led the Teen Titans, and he's trained with everybody in the DC Universe. So he's a very different kind of Batman. He's a lot easier; He's a lot looser and more relaxed."[99]

Over the years, there have been numerous others to assume the name of Batman, or to officially take over for Bruce during his leaves of absence. Jean-Paul Valley, also known as Azrael, assumed the cowl after the events of the Knightfall saga.[59] Jim Gordon donned a mecha-suit after the events of Batman: Endgame, and served as Batman in 2015 and 2016. In 2021, as part of the Fear State crossover event, Lucius Fox's son Jace Fox succeeds Bruce as Batman in a 2021 storyline, depicted in the series I Am Batman, after Batman was declared dead.

Additionally, members of the group Batman Incorporated, Bruce Wayne's experiment at franchising his brand of vigilantism, have at times stood in as the official Batman in cities around the world.[59] Various others have also taken up the role of Batman in stories set in alternative universes and possible futures, including, among them, various former proteges of Bruce Wayne.

Supporting characters

Batman's interactions with both villains and cohorts have, over time, developed a strong supporting cast of characters.[86]

Enemies

Batman faces a variety of foes ranging from common criminals to outlandish supervillains. Many of them mirror aspects of the Batman's character and development, often having tragic origin stories that lead them to a life of crime.[100] These foes are commonly referred to as Batman's rogues gallery. Batman's "most implacable foe" is the Joker, a homicidal maniac with a clown-like appearance. The Joker is considered by critics to be his perfect adversary, since he is the antithesis of Batman in personality and appearance; the Joker has a maniacal demeanor with a colorful appearance, while Batman has a serious and resolute demeanor with a dark appearance. As a "personification of the irrational", the Joker represents "everything Batman [opposes]".[34] Other long-time recurring foes that are part of Batman's rogues gallery include Catwoman (a cat burglar anti-heroine who is variously an ally and romantic interest), the Penguin, Ra's al Ghul, Two-Face (Harvey Dent), the Riddler, the Scarecrow, Mr. Freeze, Poison Ivy, Harley Quinn, Bane, Clayface, and Killer Croc, among others. Many of Batman's adversaries are often psychiatric patients at Arkham Asylum.

Allies

- Alfred

Batman's butler, Alfred Pennyworth, first appeared in Batman #16 (1943). He serves as Bruce Wayne's loyal father figure and is one of the few persons to know his secret identity. Alfred raised Bruce after his parents' death and knows him on a very personal level. He is sometimes portrayed as a sidekick to Batman and the only other resident of Wayne Manor aside from Bruce. The character "[lends] a homely touch to Batman's environs and [is] ever ready to provide a steadying and reassuring hand" to the hero and his sidekick.[100]

- "Batman family"

The informal name "Batman family" is used for a group of characters closely allied with Batman, generally masked vigilantes who either have been trained by Batman or operate in Gotham City with his tacit approval.

- Civilians

Lucius Fox, a technology specialist and Bruce Wayne's business manager who is well aware of his employer's clandestine vigilante activities (Lucius' son Luke would later become aware of Bruce's secret identity and adopt the superhero mantle of Batwing as well as become a member of the Justice League); Dr. Leslie Thompkins, a family friend who like Alfred became a surrogate parental figure to Bruce Wayne after the deaths of his parents, and is also aware of his secret identity; Vicki Vale, an investigative journalist who often reports on Batman's activities for the Gotham Gazette; Ace the Bat-Hound, Batman's canine partner who was mainly active in the 1950s and 1960s;[101] and Bat-Mite, an extra-dimensional imp mostly active in the 1960s who idolizes Batman.[101]

- GCPD

As Batman's ally in the Gotham City police, Commissioner James "Jim" Gordon debuted along with Batman in Detective Comics #27 and has been a consistent presence ever since. As a crime-fighting everyman, he shares Batman's goals while offering, much as the character of Dr. Watson does in Sherlock Holmes stories, a normal person's perspective on the work of Batman's extraordinary genius.

- Justice League

Batman is at times a member of superhero teams such as the Justice League of America and the Outsiders. Batman has often been paired in adventures with his Justice League teammate Superman, notably as the co-stars of World's Finest Comics and Superman/Batman series. In Pre-Crisis continuity, the two are depicted as close friends; however, in current continuity, they are still close friends but an uneasy relationship, with an emphasis on their differing views on crime-fighting and justice. In Superman/Batman #3 (December 2003), Superman observes, "Sometimes, I admit, I think of Bruce as a man in a costume. Then, with some gadget from his utility belt, he reminds me that he has an extraordinarily inventive mind. And how lucky I am to be able to call on him."[102]

- Robin

Robin, Batman's vigilante partner, has been a widely recognized supporting character for many years; each iteration of the Robin character, of which there have been five in the mainstream continuity, function as members of the Batman family, but additionally, as Batman's "central" sidekick in various media.[103] Bill Finger stated that he wanted to include Robin because "Batman didn't have anyone to talk to, and it got a little tiresome always having him thinking."[104] The first Robin, Dick Grayson, was introduced in 1940. In the 1970s he finally grew up, went off to college and became the hero Nightwing. A second Robin, Jason Todd, appeared in the 1980s. In the stories he was eventually badly beaten and then killed in an explosion set by the Joker, but was later revived. He used the Joker's old persona, the Red Hood, and became an antihero vigilante with no qualms about using firearms or deadly force. Carrie Kelley, the first female Robin to appear in Batman stories, was the final Robin in the continuity of Frank Miller's graphic novels The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Again, fighting alongside an aging Batman in stories set out of the mainstream continuity.

The third Robin in the mainstream comics is Tim Drake, who first appeared in 1989. He went on to star in his own comic series, and currently goes by the Red Robin, a variation on the traditional Robin persona. In the first decade of the new millennium, Stephanie Brown served as the fourth in-universe Robin between stints as her self-made vigilante identity the Spoiler, and later as Batgirl.[105] After Brown's apparent death, Drake resumed the role of Robin for a time. The role eventually passed to Damian Wayne, the 10-year-old son of Bruce Wayne and Talia al Ghul, in the late 2000s.[106] Damian's tenure as du jour Robin ended when the character was killed off in the pages of Batman Incorporated in 2013.[107] Batman's next young sidekick is Harper Row, a streetwise young woman who avoids the name Robin but followed the ornithological theme nonetheless; she debuted the codename and identity of the Bluebird in 2014. Unlike the Robins, the Bluebird is willing and permitted to use a gun, albeit non-lethal; her weapon of choice is a modified rifle that fires taser rounds.[108] In 2015, a new series began titled We Are...Robin, focused on a group of teenagers using the Robin persona to fight crime in Gotham City. The most prominent of these, Duke Thomas, later becomes Batman's crimefighting partner as The Signal.

Relationships

Children

Batman has had numerous adopted and biological children across the character's many interpretations and iterations. The first of these is Dick Grayson, Batman’s original ward and the first Robin, who eventually became Nightwing and was officially adopted by Bruce in multiple storylines. Jason Todd succeeded Grayson as Robin but eventually became Red Hood. His introduction spanned pre- and post-Crisis on Infinite Earths continuities, and despite their tumultuous relationship, Jason viewed Bruce as a father figure. Tim Drake stands out among the Robins for not being an orphan initially; he was eventually adopted by Bruce after his parents' deaths, as depicted in the Face the Face arc. Cassandra Cain, introduced in the No Man's Land storyline, became Batgirl and, after initially being more Barbara Gordon’s ward, was officially adopted by Bruce. Stephanie Brown, known as Spoiler and briefly as Robin and Batgirl, has a complex and often strained relationship with Batman but remains part of the Bat-Family. Duke Thomas, a newer addition who emerged from the We Are Robin movement, lost his parents to Joker venom and is under Bruce’s care without formal adoption. Lastly, from Earth-31, Carrie Kelley is the Robin in The Dark Knight Returns. Although not formally adopted, she is a significant member of the Bat-Family. Additionally, Bruce’s biological son, Damian Wayne, raised by Talia al Ghul, represents a complex part of Batman’s family dynamic.[109]

Romantic interests

Batman, has had a significant number of romantic entanglements over his long history in DC Comics, each adding depth and complexity to his character. His first love interest was Julie Madison, introduced in Detective Comics #31 (1939). Initially Bruce's fiancée, Julie left due to his playboy lifestyle but later returned in the New 52 continuity. Selina Kyle, or Catwoman, first appeared in Batman #1 (1940).Their relationship has been one of Batman's most enduring, characterized by a blend of romance and rivalry, culminating in their engagement during the Rebirth era. In 1941, Bruce dated Linda Page, a socialite turned nurse introduced in Batman #5. Their relationship was brief and complicated by Bruce's secret identity. Vicki Vale, a journalist introduced in Batman #49 (1948), attempted to uncover Batman's true identity, leading to a sporadic romantic involvement that grew more serious in the early 1980s. Kathy Kane, the original Batwoman, debuted in Detective Comics #233 (1956). Her relationship with Bruce was partly created to counter claims of homoerotic subtext in the comics, but she has been an enduring figure, returning in significant storylines like Batman Inc.

Talia al Ghul, daughter of Ra's al Ghul, first appeared in Detective Comics #411 (1971). Their relationship, fraught with conflict due to her father's criminal activities, resulted in the birth of Damian Wayne, who would become the latest Robin. Silver St. Cloud, introduced in Detective Comics #469 (1978), deduced Bruce's secret and ended their relationship due to the inherent dangers. Alfred's daughter, Julia Remarque, appeared in Detective Comics #501 (1981), briefly dated Bruce before being erased from continuity by Crisis on Infinite Earths. Natalia Knight, known as Nocturna, debuted in Detective Comics #529 (1983). A criminal, she became romantically involved with Bruce and adopted Jason Todd, the second Robin. Dr. Shondra Kinsolving, introduced in Batman #481 (1992), helped Bruce recover from his injuries after his battle with Bane and developed a romantic relationship with him until she was kidnapped and left with brain damage. Vesper Fairchild, a radio talk show host introduced in Batman #540 (1997), shared a relationship with Bruce that ended tragically with her murder being pinned on him. Sasha Bordeaux, introduced in Detective Comics #751 (2000), discovered Bruce's secret identity while working as his bodyguard and later joined the organization Checkmate. Batman's relationship with Wonder Woman, explored in JLA (2003), included a passionate kiss during a moment of crisis, although it remained largely unexplored due to their commitments. Rachel Dawes, an original character from the 2005 film Batman Begins who grew up with Bruce and became a significant romantic interest in the film trilogy, though she never appeared in the comics. Jezebel Jet, introduced in Batman #656 (2006), initially seemed a genuine romantic interest but later revealed her true intentions as part of a villainous plot. An infamous and controversial romantic pairing occurred in the animated adaptation of Batman: The Killing Joke (2016), where Batman and Batgirl (Barbara Gordon) were depicted as having a brief romantic involvement, which was widely criticized by fans.[110]

Abilities

Skills and training

Batman has no inherent superhuman powers; he relies on "his own scientific knowledge, detective skills, and athletic prowess".[28] Batman's inexhaustible wealth gives him access to advanced technologies, and as a proficient scientist, he is able to use and modify these technologies to his advantage. In the stories, Batman is regarded as one of the world's greatest detectives, if not the world's greatest crime solver.[111] Batman has been repeatedly described as having a genius-level intellect, being one of the greatest martial artists in the DC Universe, and having peak human physical and mental conditioning.[112] As a polymath, his knowledge and expertise in countless disciplines is nearly unparalleled by any other character in the DC Universe. He has shown prowess in assorted fields such as mathematics, biology, physics, chemistry, and several levels of engineering.[113] He has traveled the world acquiring the skills needed to aid him in his endeavors as Batman. In the Superman: Doomed story arc, Superman considers Batman to be one of the most brilliant minds on the planet.[114]

Batman has trained extensively in various fighting styles, making him one of the best hand-to-hand fighters in the DC Universe. He possesses a photographic memory[115]and He has fully utilized his photographic memory to master a total of 127 forms of martial arts including, but not limited to, aikido, boxing, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, capoeira, eskrima, fencing, gatka, hapkido, Jeet Kune Do, judo, kalaripayattu, karate, kenjutsu, kenpō, kickboxing, kobudō, Krav Maga, kyūdō, bōjutsu, Muay Thai, ninjutsu, pankration, sambo, savate, silat, taekwondo, wrestling, numerous styles of Wushu (kung fu) (such as baguazhang, Chin Na, Hung Ga, Shaolinquan, tai chi, Wing Chun), and Yaw-Yan.[116] In terms of his physical condition, Batman is described as peak human and far beyond an Olympic-athlete-level condition, able to perform feats such as easily running across rooftops in a Parkour-esque fashion, pressing thousands of pounds regularly, and even bench pressing six hundred pounds of soil and coffin in a poisoned and starved state. Superman describes Batman as "the most dangerous man on Earth", able to defeat an entire team of superpowered extraterrestrials by himself in order to rescue his imprisoned teammates in Grant Morrison's first storyline in JLA.

Batman is strongly disciplined, and he has the ability to function under great physical pain and resist most forms of telepathy and mind control. He is a master of disguise, multilingual, and an expert in espionage, often gathering information under the identity of a notorious gangster named Matches Malone. Batman is highly skilled in stealth movement and escapology, which allows him to appear and disappear at will and to break free of nearly inescapable deathtraps with little to no harm. He is also a master strategist, considered DC's greatest tactician, with numerous plans in preparation for almost any eventuality.

Batman is an expert in interrogation techniques and his intimidating and frightening appearance alone is often all that is needed in getting information from suspects. Despite having the potential to harm his enemies, Batman's most defining characteristic is his strong commitment to justice and his reluctance to take a life. This unyielding moral rectitude has earned him the respect of several heroes in the DC Universe, most notably that of Superman and Wonder Woman.

Among physical and other crime fighting related training, he is also proficient at other types of skills. Some of these include being a licensed pilot (in order to operate the Batplane), as well as being able to operate other types of machinery. In some publications, he even underwent some magician training.

Technology

Batman utilizes a vast arsenal of specialized, high-tech vehicles and gadgets in his war against crime, the designs of which usually share a bat motif. Batman historian Les Daniels credits Gardner Fox with creating the concept of Batman's arsenal with the introduction of the utility belt in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939) and the first bat-themed weapons the batarang and the "Batgyro" in Detective Comics #31 and 32 (Sept. and October 1939).[24]

- Personal armor

Batman's batsuit aids in his combat against enemies, having the properties of both Kevlar and Nomex. It protects him from gunfire and other significant impacts, and incorporates the imagery of a bat in order to frighten criminals.[117]

The details of the Batman costume change repeatedly through various decades, stories, media and artists' interpretations, but the most distinctive elements remain consistent: a scallop-hem cape; a cowl covering most of the face; a pair of bat-like ears; a stylized bat emblem on the chest; and the ever-present utility belt. His gloves typically feature three scallops that protrude from long, gauntlet-like cuffs, although in his earliest appearances he wore short, plain gloves without the scallops.[118] The overall look of the character, particularly the length of the cowl's ears and of the cape, varies greatly depending on the artist. Dennis O'Neil said, "We now say that Batman has two hundred suits hanging in the Batcave so they don't have to look the same ...Everybody loves to draw Batman, and everybody wants to put their own spin on it."[119]

Finger and Kane originally conceptualized Batman as having a black cape and cowl and grey suit, but conventions in coloring called for black to be highlighted with blue.[117] Hence, the costume's colors have appeared in the comics as dark blue and grey;[117] as well as black and grey. In the Tim Burton's Batman and Batman Returns films, Batman has been depicted as completely black with a bat in the middle surrounded by a yellow background. Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Trilogy depicted Batman wearing high-tech gear painted completely black with a black bat in the middle. Ben Affleck's Batman in the DC Extended Universe films wears a suit grey in color with a black cowl, cape, and bat symbol. Seemingly following the suit of the DC Extended Universe outfit, Robert Pattinson's uniform in The Batman restores the more traditional gray bodysuit and black appendage design, notably different from prior iterations by mostly utilizing real world armor and apparel pieces from modern military and motorcycle gear.

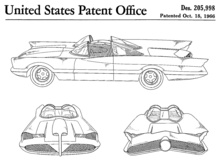

- Batmobile

Batman's primary vehicle is the Batmobile, which is usually depicted as an imposing black car, often with tailfins that suggest a bat's wings.

Batman also has an aircraft called the Batplane (originally a relatively traditionally, but bat-motifed plane, later seen as the much more unique "Batwing" starting in the 1989 film), along with various other means of transportation.

In proper practice, the "bat" prefix (as in Batmobile or batarang) is rarely used by Batman himself when referring to his equipment, particularly after some portrayals (primarily the 1960s Batman live-action television show and the Super Friends animated series) stretched the practice to campy proportions. For example, the 1960s television show depicted a Batboat, Bat-Sub, and Batcycle, among other bat-themed vehicles. The 1960s television series Batman has an arsenal that includes such "bat-" names as the Bat-computer, Bat-scanner, bat-radar, bat-cuffs, bat-pontoons, bat-drinking water dispenser, bat-camera with polarized bat-filter, bat-shark repellent bat-spray, and Bat-rope. The storyline "A Death in the Family" suggests that given Batman's grim nature, he is unlikely to have adopted the "bat" prefix on his own. In The Dark Knight Returns, Batman tells Carrie Kelley that the original Robin came up with the name "Batmobile" when he was young, since that is what a kid would call Batman's vehicle.

The Batmobile, which was before frequently depicted to resemble a sports car, was redesigned in 2011 when DC Comics relaunched its entire line of comic books, with the Batmobile being given heavier armor and new aesthetics.

- Utility belt

Batman keeps most of his field equipment in his utility belt. Over the years it has shown to contain an assortment of crime-fighting tools, weapons, and investigative and technological instruments. Different versions of the belt have these items stored in compartments, often as pouches or hard cylinders attached evenly around it.

Since the 1989 film, Batman is often depicted as carrying a projectile which shoots a retractable grappling hook attached to a cable (before this, a he employed a traditionally thrown grappling hook.) This allows him to attach to distant objects, be propelled into the air, and thus swing from the rooftops of Gotham City.

An exception to the range of Batman's equipment are hand guns, which he refuses to use on principle, since a gun was used in his parents' murder. In modern stories in terms of his vehicles, Batman compromises on that principle to install weapon systems on them for the purpose of non-lethally disabling other vehicles, forcing entry into locations and attacking dangerous targets too large to defeat by other means.

- Bat-Signal

When Batman is needed, the Gotham City police activate a searchlight with a bat-shaped insignia over the lens called the Bat-Signal, which shines into the night sky, creating a bat-symbol on a passing cloud which can be seen from any point in Gotham. The origin of the signal varies, depending on the continuity and medium.

In various incarnations, most notably the 1960s Batman TV series, Commissioner Gordon also has a dedicated phone line, dubbed the Bat-Phone, connected to a bright red telephone (in the TV series) which sits on a wooden base and has a transparent top. The line connects directly to Batman's residence, Wayne Manor, specifically both to a similar phone sitting on the desk in Bruce Wayne's study and the extension phone in the Batcave.

- Batcave

The Batcave is Batman's secret headquarters, consisting of a series of caves beneath his mansion, Wayne Manor. As his command center, the Batcave serves multiple purposes; supercomputer, surveillance, redundant power-generators, forensics lab, medical infirmary, private study, training dojo, fabrication workshop, arsenal, hangar and garage. It houses the vehicles and equipment Batman uses in his campaign to fight crime. It is also a trophy room and storage facility for Batman's unique memorabilia collected over the years from various cases he has worked on.

In both the comic book Batman: Shadow of the Bat #45 and the 2005 film Batman Begins, the cave is said to have been part of the Underground Railroad.

Fictional character biography

Batman's history has undergone many retroactive continuity revisions, both minor and major. Elements of the character's history have varied greatly. Scholars William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson noted in the early 1990s, "Unlike some fictional characters, the Batman has no primary urtext set in a specific period, but has rather existed in a plethora of equally valid texts constantly appearing over more than five decades."[120]

20th century

Origin

The central fixed event in the Batman stories is the character's origin story.[86] As a young boy, Bruce Wayne was horrified and traumatized when he watched his parents, the physician Dr. Thomas Wayne and his wife Martha, murdered with a gun by a mugger named Joe Chill. Batman refuses to utilize any sort of gun on the principle that a gun was used to murder his parents. This event drove him to train his body to its peak condition and fight crime in Gotham City as Batman. Pearson and Uricchio also noted beyond the origin story and such events as the introduction of Robin, "Until recently, the fixed and accruing and hence, canonized, events have been few in number",[86] a situation altered by an increased effort by later Batman editors such as Dennis O'Neil to ensure consistency and continuity between stories.[121]

Golden Age

In Batman's first appearance in Detective Comics #27, he is already operating as a crime-fighter.[122] Batman's origin is first presented in Detective Comics #33 (November 1939) and is later expanded upon in Batman #47. As these comics state, Bruce Wayne is born to Dr. Thomas Wayne and his wife Martha, two very wealthy and charitable Gotham City socialites. Bruce is brought up in Wayne Manor, and leads a happy and privileged existence until the age of 8, when his parents are killed by a small-time criminal named Joe Chill while on their way home from a movie theater. That night, Bruce Wayne swears an oath to spend his life fighting crime. He engages in intense intellectual and physical training; however, he realizes that these skills alone would not be enough. "Criminals are a superstitious cowardly lot", Wayne remarks, "so my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible ..." As if responding to his desires, a bat suddenly flies through the window, inspiring Bruce to craft the Batman persona.[123]

In early strips, Batman's career as a vigilante earns him the ire of the police. During this period, Bruce Wayne has a fiancé named Julie Madison.[124] In Detective Comics #38, Wayne takes in an orphaned circus acrobat, Dick Grayson, who becomes his vigilante partner, Robin. Batman also becomes a founding member of the Justice Society of America,[125] although he, like Superman, is an honorary member,[126] and thus only participates occasionally. Batman's relationship with the law thaws quickly, and he is made an honorary member of Gotham City's police department.[127] During this time, Alfred Pennyworth arrives at Wayne Manor, and after deducing the Dynamic Duo's secret identities, joins their service as their butler.[128]

Silver Age

The Silver Age of Comic Books in DC Comics is sometimes held to have begun in 1956 when the publisher introduced Barry Allen as a new, updated version of the Flash. Batman is not significantly changed by the late 1950s for the continuity which would be later referred to as Earth-One. The lighter tone Batman had taken in the period between the Golden and Silver Ages led to the stories of the late 1950s and early 1960s that often feature many science-fiction elements, and Batman is not significantly updated in the manner of other characters until Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), in which Batman reverts to his detective roots, with most science-fiction elements jettisoned from the series.

After the introduction of DC Comics' Multiverse in the 1960s, DC established that stories from the Golden Age star the Earth-Two Batman, a character from a parallel world. This version of Batman partners with and marries the reformed Earth-Two Catwoman (Selina Kyle). The two have a daughter, Helena Wayne, who becomes the Huntress. She assumes the position as Gotham's protector along with Dick Grayson, the Earth-Two Robin, once Bruce Wayne retires to become police commissioner. Wayne holds the position of police commissioner until he is killed during one final adventure as Batman. Batman titles, however, often ignored that a distinction had been made between the pre-revamp and post-revamp Batmen (since unlike the Flash or Green Lantern, Batman comics had been published without interruption through the 1950s) and would occasionally make reference to stories from the Golden Age.[129] Nevertheless, details of Batman's history were altered or expanded upon through the decades. Additions include meetings with a future Superman during his youth, his upbringing by his uncle Philip Wayne (introduced in Batman #208 (February 1969)) after his parents' death, and appearances of his father and himself as prototypical versions of Batman and Robin, respectively.[130][131] In 1980, then-editor Paul Levitz commissioned the Untold Legend of the Batman miniseries to thoroughly chronicle Batman's origin and history.

Batman meets and regularly works with other heroes during the Silver Age, most notably Superman, whom he began regularly working alongside in a series of team-ups in World's Finest Comics, starting in 1954 and continuing through the series' cancellation in 1986. Batman and Superman are usually depicted as close friends. As a founding member of the Justice League of America, Batman appears in its first story, in 1960's The Brave and the Bold #28. In the 1970s and 1980s, The Brave and the Bold became a Batman title, in which Batman teams up with a different DC Universe superhero each month.

Bronze Age

In 1969, Dick Grayson attends college as part of DC Comics' effort to revise the Batman comics. Additionally, Batman also moves from his mansion, Wayne Manor into a penthouse apartment atop the Wayne Foundation building in downtown Gotham City, in order to be closer to Gotham City's crime. In 1974's "Night of the Stalker" storyline, a diploma on the wall reveals Bruce Wayne as a graduate of Yale Law School.[132] Batman spends the 1970s and early 1980s mainly working solo, with occasional team-ups with Robin and/or Batgirl. Batman's adventures also become somewhat darker and more grim during this period, depicting increasingly violent crimes, including the first appearance (since the early Golden Age) of the Joker as a homicidal psychopath, and the arrival of Ra's al Ghul, a centuries-old terrorist who knows Batman's secret identity. In the 1980s, Dick Grayson becomes Nightwing.[133]

In the final issue of The Brave and the Bold in 1983, Batman quits the Justice League and forms a new group called the Outsiders. He serves as the team's leader until Batman and the Outsiders #32 (1986) and the comic subsequently changed its title.

Modern Age

After the 12-issue miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC Comics retconned the histories of some major characters in an attempt at updating them for contemporary audiences. Frank Miller retold Batman's origin in the storyline "Year One" from Batman #404–407, which emphasizes a grittier tone in the character.[134] Though the Earth-Two Batman is erased from history, many stories of Batman's Silver Age/Earth-One career (along with an amount of Golden Age ones) remain canonical in the Post-Crisis universe, with his origins remaining the same in essence, despite alteration. For example, Gotham's police are mostly corrupt, setting up further need for Batman's existence. The guardian Phillip Wayne is removed, leaving young Bruce to be raised by Alfred Pennyworth. Additionally, Batman is no longer a founding member of the Justice League of America, although he becomes leader for a short time of a new incarnation of the team launched in 1987. To help fill in the revised backstory for Batman following Crisis, DC launched a new Batman title called Legends of the Dark Knight in 1989 and has published various miniseries and one-shot stories since then that largely take place during the "Year One" period.[135]

Subsequently, Batman begins exhibiting an excessive, reckless approach to his crimefighting, a result of the pain of losing Jason Todd. Batman works solo until the decade's close, when Tim Drake becomes the new Robin.[136]

Many of the major Batman storylines since the 1990s have been intertitle crossovers that run for a number of issues. In 1993, DC published "Knightfall". During the storyline's first phase, the new villain Bane paralyzes Batman, leading Wayne to ask Azrael to take on the role. After the end of "Knightfall", the storylines split in two directions, following both the Azrael-Batman's adventures, and Bruce Wayne's quest to become Batman once more. The story arcs realign in "KnightsEnd", as Azrael becomes increasingly violent and is defeated by a healed Bruce Wayne. Wayne hands the Batman mantle to Dick Grayson (then Nightwing) for an interim period, while Wayne trains for a return to the role.[137]

The 1994 company-wide crossover storyline Zero Hour: Crisis in Time! changes aspects of DC continuity again, including those of Batman. Noteworthy among these changes is that the general populace and the criminal element now consider Batman an urban legend rather than a known force.

Batman once again becomes a member of the Justice League during Grant Morrison's 1996 relaunch of the series, titled JLA. During this time, Gotham City faces catastrophe in the decade's closing crossover arc. In 1998's "Cataclysm" storyline, Gotham City is devastated by an earthquake and ultimately cut off from the United States. Deprived of many of his technological resources, Batman fights to reclaim the city from legions of gangs during 1999's "No Man's Land".

Meanwhile, Batman's relationship with the Gotham City Police Department changed for the worse with the events of "Batman: Officer Down" and "Batman: War Games/War Crimes"; Batman's long-time law enforcement allies Commissioner Gordon and Harvey Bullock are forced out of the police department in "Officer Down", while "War Games" and "War Crimes" saw Batman become a wanted fugitive after a contingency plan of his to neutralize Gotham City's criminal underworld is accidentally triggered, resulting in a massive gang war that ends with the sadistic Black Mask the undisputed ruler of the city's criminal gangs. Lex Luthor arranges for the murder of Batman's on-again, off-again love interest Vesper Lynd (introduced in the mid-1990s) during the "Bruce Wayne: Murderer?" and "Bruce Wayne: Fugitive" story arcs. Though Batman is able to clear his name, he loses another ally in the form of his new bodyguard Sasha, who is recruited into the organization known as "Checkmate" while stuck in prison due to her refusal to turn state's evidence against her employer. While he was unable to prove that Luthor was behind the murder of Vesper, Batman does get his revenge with help from Talia al Ghul in Superman/Batman #1–6.

21st century

2000s

DC Comics' 2005 miniseries Identity Crisis reveals that JLA member Zatanna had edited Batman's memories to prevent him from stopping the Justice League from lobotomizing Dr. Light after he raped Sue Dibny. Batman later creates the Brother I satellite surveillance system to watch over and, if necessary, kill the other heroes after he remembered. The revelation of Batman's creation and his tacit responsibility for the Blue Beetle's death becomes a driving force in the lead-up to the Infinite Crisis miniseries, which again restructures DC continuity. Batman and a team of superheroes destroy Brother EYE and the OMACs, though, at the very end, Batman reaches his apparent breaking point when Alexander Luthor Jr. seriously wounds Nightwing. Picking up a gun, Batman nearly shoots Luthor in order to avenge his former sidekick, until Wonder Woman convinces him to not pull the trigger.

Following Infinite Crisis, Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson (having recovered from his wounds), and Tim Drake retrace the steps Bruce had taken when he originally left Gotham City, to "rebuild Batman".[138] In the Face the Face storyline, Batman and Robin return to Gotham City after their year-long absence. Part of this absence is captured during Week 30 of the 52 series, which shows Batman fighting his inner demons.[139] Later on in 52, Batman is shown undergoing an intense meditation ritual in Nanda Parbat. This becomes an important part of the regular Batman title, which reveals that Batman is reborn as a more effective crime fighter while undergoing this ritual, having "hunted down and ate" the last traces of fear in his mind.[140][141] At the end of the "Face the Face" story arc, Bruce officially adopts Tim (who had lost both of his parents at various points in the character's history) as his son.[142] The follow-up story arc in Batman, Batman and Son, introduces Damian Wayne, who is Batman's son with Talia al Ghul. Although originally, in Batman: Son of the Demon, Bruce's coupling with Talia was implied to be consensual, this arc retconned it into Talia forcing herself on Bruce.[143]

Batman, along with Superman and Wonder Woman, reforms the Justice League in the new Justice League of America series,[144] and is leading the newest incarnation of the Outsiders.[145]

Grant Morrison's 2008 storyline, "Batman R.I.P." featured Batman being physically and mentally broken by the enigmatic villain Doctor Hurt and attracted news coverage in advance of its highly promoted conclusion, which would speculated to feature the death of Bruce Wayne.[146] However, though Batman is shown to possibly perish at the end of the arc, the two-issue arc "Last Rites", which leads into the crossover storyline "Final Crisis", shows that Batman survives his helicopter crash into the Gotham City River and returns to the Batcave, only to be summoned to the Hall of Justice by the JLA to help investigate the New God Orion's death. The story ends with Batman retrieving the god-killing bullet used to kill Orion, setting up its use in "Final Crisis".[147] In the pages of Final Crisis Batman is reduced to a charred skeleton.[148] In Final Crisis #7, Wayne is shown witnessing the passing of the first man, Anthro.[149][150] Wayne's "death" sets up the three-issue Battle for the Cowl miniseries in which Wayne's ex-proteges compete for the "right" to assume the role of Batman, which concludes with Grayson becoming Batman,[151] while Tim Drake takes on the identity of the Red Robin.[152] Dick and Damian continue as Batman and Robin, and in the crossover storyline "Blackest Night", what appears to be Bruce's corpse is reanimated as a Black Lantern zombie,[153] but is later shown that Bruce's corpse is one of Darkseid's failed Batman clones. Dick and Batman's other friends conclude that Bruce is alive.[154][155]

2010s

Bruce subsequently returned in Morrison's miniseries Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne, which depicted his travels through time from prehistory to present-day Gotham.[156][157][158] Bruce's return set up Batman Incorporated, an ongoing series which focused on Wayne franchising the Batman identity across the globe, allowing Dick and Damian to continue as Gotham's Dynamic Duo. Bruce publicly announced that Wayne Enterprises will aid Batman on his mission, known as "Batman, Incorporated". However, due to rebooted continuity that occurred as part of DC Comics' 2011 relaunch of all of its comic books, The New 52, Dick Grayson was restored as Nightwing with Wayne serving as the sole Batman once again. The relaunch also interrupted the publication of Batman, Incorporated, which resumed its story in 2012–2013 with changes to suit the new status quo.

The New 52

During The New 52, all of DC's continuity was reset and the timeline was changed, making Batman the first superhero to emerge. This emergence took place during Zero Year, where Bruce Wayne returns to Gotham and becomes Batman, fighting the original Red Hood[159] and the Riddler.[160] In the present day, Batman discovers the Court of Owls, a secret organization operating in Gotham for decades.[161] Batman somewhat defeats the Court by defeating Owlman,[162] although the Court continues to operate on a smaller scale.[163] The Joker returns after losing the skin on his face (as shown in the opening issue of the second volume of Detective Comics) and attempts to kill the Batman's allies, though he is stopped by Batman.[164] After some time, Joker returns again, and both he and Batman die while fighting each other. Jim Gordon temporarily becomes Batman, using a high-tech suit, while it is revealed that an amnesiac Bruce Wayne is still alive.[citation needed] Gordon attempts to fight a new villain called Mr. Bloom, while Wayne, regains his memories with the help of Alfred Pennyworth and Julie Madison. Once with his memories, Wayne becomes Batman again and defeats Mr. Bloom with the help of Gordon.[citation needed]

DC Rebirth

The timeline was reset again during Rebirth, although no significant changes were made to the Batman mythos. [citation needed] Batman meets two new superheroes operating in Gotham named Gotham and Gotham Girl. Psycho-Pirate gets into Gotham's head and turns against Batman, and is finally defeated when he is killed. This event is very traumatic for Gotham Girl and she begins to lose her sanity.[165]

Batman forms his own Suicide Squad, including Catwoman, and attempts to take down Bane. The mission is successful, and Batman breaks Bane's back.[166] Batman proposes to Catwoman.

After healing from his wounds, an angry Bane travels to Gotham, where he fights Batman and loses.[167] Batman then tells Catwoman about the War of Jokes and Riddles, and she agrees to marry him.[168] Bane takes control of Arkham Asylum and manipulates Catwoman into leaving Wayne before the wedding.[169] This causes Wayne to become very angry, and, as Batman, lashes out against criminals, nearly killing Mr. Freeze.[170]