Modafinil

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Not determined due to the aqueous insolubility |

| Protein binding | 60% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, including CYP3A4 and other pathways |

| Elimination half-life | 12–15 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (as metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.168.719 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

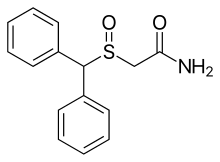

| Formula | C15H15NO2S |

| Molar mass | 273.35 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| (verify) | |

Modafinil (Provigil, Alertec, Modavigil, Modalert, Modiodal, Modafinilo, Carim) is an analeptic drug manufactured by Cephalon, and is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder,[2][3] and excessive daytime sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnea.[4] The European Medicines Agency has recommended it be prescribed only for narcolepsy[5].

Despite extensive research into the interaction of modafinil with a large number of neurotransmitter systems, a precise mechanism or set of mechanisms of action remains unclear.[6][7] It seems that modafinil, like other stimulants, increases the release of monoamines, specifically the catecholamines norepinephrine and dopamine, from the synaptic terminals. However, modafinil also elevates hypothalamic histamine levels,[8] leading some researchers to consider Modafinil a "wakefulness promoting agent" rather than a classic amphetamine-like stimulant (as evidenced by the difference in c-Fos distribution caused by modafinil as compared to amphetamine).[9] Despite modafinil's histaminergic action, it still partially shares the actions of amphetamine-class stimulants due to its effects on norepinephrine and dopamine.

An NIAAA study highlighted "the need for heightened awareness for potential abuse of and dependence on modafinil in vulnerable populations" due to the drug's effect on dopamine in the brain's reward center.[10] However, the synergistic actions of modafinil on both catecholaminergic and histaminergic pathways lowers abuse potential as compared to traditional stimulant drugs while maintaining the effectiveness of the drug as a wakefulness promoting agent. Studies have suggested that modafinil "has limited potential for large-scale abuse"[11] and "does not possess an addictive potential in naive [new] individuals."[12]

Although there was some speculation modafinil could be effective in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) due to its similarity to amphetamine-class stimulants, in 2006 it was found by the FDA to be unfit for use by children for that purpose due to the risk of potentially serious side effects. Cephalon's own label for Provigil now discourages its use by children for any purpose.[13] Other potentially effective, but unapproved targets include the treatment of depression,[14] opiate[15] & cocaine dependence,[16] Parkinson's disease,[17] schizophrenia,[18] and disease-related fatigue.[19][20]

Under the US Food and Drug Act, drug companies are not allowed to market their drugs for off-label uses (conditions other than those officially approved by the FDA)[21]; Cephalon was reprimanded in 2002 by the FDA because its promotional materials were found to be "false, lacking in fair balance, or otherwise misleading".[22] Cephalon pled guilty to a criminal violation and paid several fines, including $50 and $425 million fines to the U.S. government in 2008 due to its marketing[23].

Modafinil and its chemical precursor adrafinil were developed by Lafon Laboratories, a French company acquired by Cephalon in 2001.[24] Modafinil is the primary metabolite of adrafinil, and, while its activity is similar, adrafinil requires a higher dose to achieve equipotent effects. Modafinil is a racemic mixture; the (R)-enantiomer is known as armodafinil (Nuvigil).

Indications

In the United States, modafinil is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration only for the treatment of narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea and shift work sleep disorder. In some countries, it is also approved for idiopathic hypersomnia (all forms of excessive daytime sleepiness where causes can't be established). It generally begins to work within one to two days.

Off-label use

Modafinil is widely used off-label to suppress the need for sleep. It is also used off-label in combating general fatigue unrelated to lack of sleep such as in treating ADHD and as an adjunct to antidepressants (particularly in individuals with significant residual fatigue).

There is a disagreement whether the cognitive effects modafinil showed in healthy non-sleep-deprived people are sufficient to consider it to be a cognitive enhancer.[25][26][27] The researchers agree that modafinil improves some aspects of working memory, such as digit span, digit manipulation and pattern recognition memory, but the results related to spatial memory, executive function and attention are equivocal.[25][26][27][28] Some of the positive effects of modafinil may be limited to "lower-performing"[28] individuals or to the individuals with lower IQ.[29]

There is also evidence that it has neuroprotective effects.[30]

Modafinil may be also an effective and well-tolerated treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression [31]

Doping agent

Modafinil has received some publicity in the past when several athletes (such as cyclist David Clinger in 2010[32]) were discovered allegedly using it as a performance-enhancing doping agent. It is not clear how widespread this practice is. Since there are no studies pertaining to this sort of use, it is unknown what impact modafinil has on an athlete's performance. However, anecdotal evidence indicates that modafinil does indeed enhance physical performance, likely due to its amphetamine-mimicking properties. Modafinil was added to the World Anti-Doping Agency "Prohibited List" in 2004 as a prohibited stimulant (see Modafinil Legal Status).

Multiple sclerosis

Modafinil is not approved for, but has been used to allay symptoms of the neurological fatigue reported by some with multiple sclerosis. Patients follow either the standard usage or take a single dose of 200–400 mg at the start of days self-assessed as being potentially excessively fatiguing. In 2000, Cephalon conducted a study to evaluate modafinil as a potential treatment for MS-related fatigue. A group of 72 people with MS of varying degrees of severity tested two different doses of modafinil and an inactive placebo over nine weeks. Fatigue levels were self-evaluated on standardized scales. Participants taking a lower dose of modafinil reported feeling less fatigued and there was a statistically significant difference in fatigue scores for the lower dose versus the placebo. The higher dose of modafinil was not reported to be significantly more effective.[33]

ADHD

As of February 2007, there are at least seven English-language articles on randomized clinical trials in humans in the Medline database addressing the use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)[citation needed]. Some studies have shown the use of modafinil in the treatment of ADHD is associated with significant improvements in primary outcome measures.[citation needed] Cognitive function in ADHD patients was also found to improve following modafinil treatment, in some studies.[citation needed] Studies for ADHD report insomnia and headache were the most common adverse effects, seen in approximately 20% of treated individuals.[citation needed] These studies were not adequate to demonstrate that the beneficial effects of modafinil are maintained with chronic administration. Additional large, long-term studies using flexible titration methods to establish safety and efficacy and head-to-head comparisons between modafinil and stimulants are needed to determine the role of modafinil in the treatment of ADHD.[34]

In December 2004, Cephalon submitted a supplemental new drug application (sNDA) to market Sparlon, a brand name of tablets containing higher doses of modafinil for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents ages 6 through 17. However, in March 2006, the FDA advisory committee voted 12 to 1 against approval, citing concerns about a number of reported cases of skin rash reactions in a 1000-patient trial, including one which was thought to be likely a case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.[35][36] Final rejection occurred in August 2006, although subsequent follow-up indicated that the skin rash reaction was not Stevens-Johnson syndrome.[citation needed] Cephalon then decided to discontinue development of the Sparlon product for use in pediatric cases, though there is potential for use in treating Adult ADHD. The high coincidence of day time sleepyness, sudden onset of day time sleep episodes (clinically indistinguishable from narcolepsy) in adult ADHD patients during inattentive-boring episodes of inactivity suggest a potential benefit of modafinil in ADHD patients suffering from episodic sleep disturbances.

Modafinil is relatively contraindicated for patients with a history of cardiac events. However, one 2005 case report[37] positively describes transitioning a 78 year old with "significant cardiac comorbidity" from methylphenidate (5 mg b.i.d.) to modafinil; however, this was in the context of severe treatment-resistant depression, not ADHD.

Other uses

Modafinil is also used off-label to treat sedation and fatigue in depression,[38][39], fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, myotonic dystrophy,[40] opioid-induced sleepiness,[41] spastic cerebral palsy,[42] and Parkinson’s disease.[43] It increases subjective mood and friendliness, at least among shift workers.[44]

It has been used to help jet-lag[45].

During high-risk, large-scale, and extended law enforcement or homeland security operations, tactical paramedics in Maryland (US) may administer 200 mg of modafinil once daily to law enforcement personnel in order to "enhance alertness / concentration" and "facilitate functioning with limited rest periods."[46]

Recently modafinil has become popular in performance-enhancing use by university students in the United Kingdom. Some students obtain the drug through illicit means (diversion of prescribed medication), although others obtain it through online pharmacy [47].

Experimental uses

Cocaine addiction

A single 8-week double-blind study of modafinil for cocaine dependence produced inconclusive results. The number of cocaine-positive urine samples was significantly lower in the modafinil group as compared to the placebo group in the middle of the trial, but by the end of the 8 weeks the difference stopped being significant. Even before the treatment began, the modafinil group had lower cocaine consumption further confounding the results. As compared to placebo, modafinil did not reduce cocaine craving or self-reported cocaine use, and the physicians ratings were only insignificantly better.[48] Dan Umanoff, of the National Association for the Advancement and Advocacy of Addicts, criticized the authors of the study for leaving the negative results out of the discussion part and the abstract of the article.[49][50]

Weight loss

Studies on modafinil (even those on healthy weight individuals) indicate that it has an appetite reducing/weight loss effect.[44][51][52][53][54] All studies on modafinil in the Medline database that are for one month or longer which report weight changes find that modafinil users experience weight loss compared to placebo.[55] However, the prescribing information for Provigil notes that "There were no clinically significant differences in body weight change in patients treated with PROVIGIL compared to placebo-treated patients in the placebo-controlled clinical trials." [56]

In experimental studies, the appetite reducing effect of modafinil appears to be similar to that of amphetamines, but, unlike amphetamines, the dose of modafinil that is effective at decreasing food intake does not significantly increase heart rate. Also, an article published in the Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, presented the case of a 280 pound patient (BMI=35.52) who lost 40 pounds over the course of a year on Modafinil (to 30.44 BMI). After three years, his weight stabilized at a 50 pound weight loss (29.59 BMI). The authors conclude that placebo controlled studies should be conducted on using Modafinil as a weight loss agent.[51] Conversely, a US patent (#6,455,588) on using modafinil as an appetite stimulating agent has been filed by Cephalon in 2000.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Modafinil has been shown to improve excessive daytime somnolence and fatigue in primary biliary cirrhosis. After two months of treatment significant improvement was observed in symptoms of fatigue using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.[57]

Post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment

Modafinil has been used off-label in trials with people with symptoms of Post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment, also known as "chemobrain".[58] A University of Rochester study of 68 subjects had significant results. "We knew from previous studies that modafinil does alleviate problems with memory and attention, and were hoping it would do the same for breast-cancer patients experiencing chemo-brain, which it did," related the study's lead author Sadhna Kohli, Ph.D, a research assistant professor at the University of Rochester's James P. Wilmot Cancer Center.[59]

Mood elevation

Modafinil used in a randomized double-blind study showed that normal healthy volunteers between the ages of 30-44 showed general improvement in alertness as well as mood. In the three-day study, counterbalanced, randomized, crossover, inpatient trial of modafinil 400 mg was administered as well as a placebo to the control group. The conclusion demonstrated that modafinil may have general mood-elevating effects in particular for the adjunctive use in treatment-resistant depression.[57]

Contraindications and warnings

Literature distributed by maker Cephalon advises that it is important to consult with your physician before using Modafinil, particularly for those with:

- Hypersensitivity to the drug or other constituents of the tablets, or

- Previous cardiovascular problems, particularly while using other stimulants, or

- Cirrhosis, or

- Cardiac conditions, particularly:

- Left ventricular hypertrophy, or

- Mitral valve prolapse.

- Asymptomatic MVP is not uncommon, but neither is it prominently discussed in Modafinil's context.

Side effects

In 2007, the FDA ordered Cephalon to modify the Provigil leaflet in bold-face print of several serious and potentially fatal conditions attributed to modafinil use, including TEN, DRESS syndrome, and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS).

The long term safety and effectiveness of modafinil has not been determined.[60]

Modafinil may have an adverse effect on hormonal contraceptives, lasting for a month after cessation of dosage.[61] Modafinil toxicity levels vary widely among species. In mice and rats, the median lethal dose LD50 of modafinil is approximately or slightly greater than 1250 mg/kg. Oral LD50 values reported for rats range from 1000 mg/kg to 3400 mg/kg. Intravenous LD50 for dogs is 300 mg/kg. In clinical trials on humans, taking up to 1200 mg/day for 7 to 21 days or one-time doses up to 4500 mg did not appear to cause life-threatening effects, although a number of adverse experiences were observed, including excitation or agitation, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, aggressiveness, confusion, nervousness, tremor, palpitations, sleep disturbances, nausea, and diarrhea. As of 2004, FDA is not aware of any fatal overdoses involving modafinil alone (as opposed to multiple drugs, including modafinil).[62] Consequently, oral LD50 of modafinil in humans is not known exactly. However, it appears to be higher than oral LD50 of caffeine. Basti and Jouvet (1988) describe a suicide attempt using 4500 mg of modafinil; the suicidee survived with no long-term effects but temporary nervousness, nausea, and insomnia[63]

Severe adverse reactions

Modafinil may induce severe dermatologic reactions requiring hospitalization. From the date of initial marketing, December 1998, to January 30, 2007, FDA received six cases of severe cutaneous adverse reactions associated with modafinil, including erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) involving adult and pediatric patients. The FDA issued a relevant alert. In the same alert, the FDA also noted that angioedema and multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions have also been reported in postmarketing experience.[64]

Military and astronaut use

Militaries of several countries are known to have expressed interest in Modafinil as an alternative to amphetamines—the drug traditionally employed in combat situations where troops face sleep deprivation, such as during lengthy missions. The French government indicated that the Foreign Legion used modafinil during certain covert operations. The United Kingdom's Ministry of Defence commissioned research into Modafinil[65] from QinetiQ and spent £300,000 on one investigation.[66]

In the United States military, Modafinil has been approved for use on certain Air Force missions, and it is being investigated for other uses.[67] One study of helicopter pilots suggested that 600 mg of modafinil given in three doses can be used to keep pilots alert and maintain their accuracy at pre-deprivation levels for 40 hours without sleep.[68] However, significant levels of nausea and vertigo were observed. Another study of fighter pilots showed that modafinil given in three divided 100 mg doses sustained the flight control accuracy of sleep-deprived F-117 pilots to within about 27 percent of baseline levels for 37 hours, without any considerable side effects.[69] In an 88-hour sleep loss study of simulated military grounds operations, 400 mg/day doses were mildly helpful at maintaining alertness and performance of subjects compared to placebo, but the researchers concluded that this dose was not high enough to compensate for most of the effects of complete sleep loss.[70]

The Canadian Medical Association Journal also reports that Modafinil is used by astronauts on long-term missions aboard the International Space Station. Modafinil is "available to crew to optimize performance while fatigued" and helps with the disruptions in circadian rhythms and with the reduced quality of sleep astronauts experience.[71]

Pharmacology

The exact mechanism of action of Modafinil is unclear, although numerous studies have shown it to increase the levels of various monoamines, namely; dopamine in the striatum and nucleus accumbens,[72][73] noradrenaline in the hypothalamus and ventrolateral preoptic nucleus,[74][75] and serotonin in the amygdala and frontal cortex.[76] While the co-administration of a dopamine antagonist is known to decrease the stimulant effect of amphetamine, it does not entirely negate the wakefulness-promoting actions of modafinil. Modafinil activates glutamatergic circuits while inhibiting GABAergic neurotransmission.

A considered mechanism of action involves brain peptides called orexins, also known as hypocretins. Orexin neurons are found in the hypothalamus but project to many different parts of the brain, including several areas that regulate wakefulness. Activation of these neurons increases dopamine and norepinephrine in these areas, and excites histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons increasing histamine levels there. It has been shown in rats that modafinil increases histamine release in the brain, and this may be a possible mechanism of action in humans.[77] There are two receptors for hypocretins, namely hcrt1 and hcrt2. Animal studies have shown that animals with defective orexin systems show signs and symptoms similar to narcolepsy for which Modafinil is FDA approved. Modafinil seems to activate these orexin neurons in animal models, which would be expected to promote wakefulness [78][79]. However, a study of genetically modified dogs lacking orexin receptors showed that modafinil still promoted wakefulness in these animals, suggesting that orexin activation is not required for the effects of modafinil (reference needed). Additionally, a study looking at orexin-knockout mice, found that not only did not modafinil promote wakefulness in these mice but did so even more effectively than in the wild-type mice [80].

Since modafinil's substantial, but incomplete, independence from both monoaminergic systems and those of the orexin peptides has proven baffling with respect to the better understood mechanisms of stimulants such as cocaine, enhanced electrotonic coupling has been suggested by several studies. While chemical synapses present an obvious target for drug treatments, neurons are also be coupled electrotonically via gap junctions. In support of this theory, Urbano et al. determined that modafinil increased activity in the thalamocortical loop (critical in organizing sensory input and modulating global brain activity) via enhancements in electrotonic coupling.[81] Administration of the gap junction blocker mefloquine abolished this effect, verifying the suspicion that the effect was consequent of improved electrical coupling. Further research by the same group also noted the capacity of the calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor, KN-93, to abolish modafinil's enhancement of electrotonic coupling. They came to the conclusion that modafinil's effect is mediated, at least in part, by a CaMKII-dependent exocytosis of gap junctions between GABAergic interneurons and possibly even glutamatergic pyramidal cells. Additionally, Garcia-Rill et al. discovered that modafinil has pro electrotonic effects on specific populations of neurons in two sites in the reticular activating system. These sites, the subcoeruleus nucleus and the pedunculopontine nucleus, are thought to enhance arousal via cholinergic inputs to the thalamus.[82]

Looking more closely at electrotonic coupling, gap junctions permit the diffusion of current across linked cells and result in higher resistance to action potential induction since excitatory post-synaptic potentials must to diffuse across a greater membrane area. This means, however, that when action potentials do arise in coupled cell populations, the entire populations tend to fire in a synchronized manner.[83] Thus enhanced electrotonic coupling results in lower tonic activity of the coupled cells while increasing rhythmicity. Agreeing with data implicating catecholaminergic mechanisms, modafinil increases phasic activity in the locus coeruleus (the source for CNS norepinephrine) while reducing tonic activity with respect to interconnections with the prefrontal cortex.[84] This implies an increased signal-to-noise ratio in the circuits connecting the two regions. Greater neuronal coupling theoretically could enhance gamma band rhythmicity, a potential explanation for modafinil's nootropic effects.[85] Modafinil's beneficial effects on working memory and motor networks are suggestive of heightened gamma band activity.[85]

Direct links between electrotonic coupling and wakefulness were provided by Beck et al. who showed that administration of modafinil enhanced arousal-specific P13 evoked potentials in a gap-junction dependent manner.[86] Tying into inconclusive effects on monoamine systems, enhanced electrotonic coupling is thought to reduce activity in localized populations of GABAergic neurons whose normal function is to reduce neurotransmitter release in other cells.[83] For example, dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens has been demonstrated to be the result of to decreased GABAergic tone.[87] Thus, while modafinil's unique stimulant profile features interactions with monoamine systems, these may very well be downstream events secondary to effects on specific, electrotonically-coupled populations of GABAergic interneurons. It is likely that modafinil's exact pharmacology will feature the interaction of direct effects on electrotonic coupling and various receptor-mediated events.

Recently, modafinil was screened at a large panel of receptors and transporters in an attempt to elucidate its pharmacology.[88] Of the sites tested, it was found to significantly act only on the dopamine transporter (DAT), inhibiting the reuptake of dopamine with an IC50 value of 4 μM.[88] Accordingly, it produces locomotor activity and extracellular dopamine concentrations in a manner similar to the selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor (DRI) vanoxerine, and also blocks methamphetamine-induced dopamine release.[88] As a result, it appears that modafinil exerts its effects by acting as a weak DRI, though it cannot be ruled out that other mechanisms may also be at play.[88] On account of its action as a DRI and lack of abuse potential, modafinil was suggested as a treatment for methamphetamine addiction by the authors of the study.[88]

The (R)-enantiomer of modafinil has also recently been found to act as a D2 receptor partial agonist, with a Ki of 16 nM, an intrinsic activity of 48%, and an EC50 of 120 nM, in rat striatal tissue.[89] The (S)-enantiomer is inactive (Ki > 10,000).[89]

Pharmacokinetics

Modafinil induces the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP3A4, as well as inhibiting CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 in vitro. It may also induce P-glycoprotein, which may affect drugs transported by Pgp, such as digoxin. The bioavailability of Modafinil is greater than 80% of the administered dose. In vitro measurements indicate that 60% of Modafinil is bound to plasma proteins at clinical concentrations of the drug. This percentage actually changes very little when the concentration is varied.[90] Cmax occurs approximately 2–3 hours after administration. Food will slow absorption, but does not affect the total AUC. Half-life is generally in the 10–12 hour range, subject to differences in CYP genotypes, liver function and renal function. It is metabolized in the liver, and its inactive metabolite is excreted in the urine. Urinary excretion of the unchanged drug ranges from 0% to as high as 18.7%, depending on various factors.[90]

Detection in body fluids

Modafinil and/or its major metabolite, modafinil acid, may be quantified in plasma, serum or urine to monitor dosage in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in the forensic investigation of a vehicular traffic violation. Instrumental techniques involving gas or liquid chromatography are usually employed for these purposes.[91][92]

History

Modafinil originated with the late 1970s invention of a series of benzhydryl sulfinyl compounds, also including adrafinil, by scientists working with the French pharmaceutical company Lafon. Adrafinil was first offered as an experimental treatment for narcolepsy in France in 1986. Modafinil is the primary metabolite of adrafinil and has similar activity but is much more widely used. It has been prescribed in France since 1994 under the name Modiodal, and in the US since 1998 as Provigil. It was approved for use in the UK in December 2002. Modafinil is marketed in the US by Cephalon Inc., who leased the rights from Lafon. Cephalon eventually purchased Lafon in 2001. In 2005, a petition by a private individual was filed with the FDA requesting over-the-counter sale of modafinil.[93]

Patent protection and antitrust litigation

A U.S. patent 4,927,855 was granted to Lafon for modafinil in 1990. The FDA granted modafinil orphan drug status in 1993. The formulation patent expired on 30 March 2006. The particle size patent was filed by Cephalon U.S. patent 5,618,845, covering pharmaceutical compositions of modafinil, in 1994. That patent, granted in 1997, was reissued in 2002 as RE 37,516, which provides Cephalon with patent protection for certain preparations of the drug in the United States until 2014, which is now apparently extended to April 6, 2015 after Cephalon received a six-month patent extension from the FDA.[94][95]

Some competing generic pharmaceutical manufacturers applied to the FDA to market a generic form of modafinil in 2006 (the year of patent expiry of the active ingredient). At least one withdrew its application after early opposition by Cephalon based on its new patent on particle sizes (set to expire in 2015). There is some question as to whether a particle size patent is sufficient protection against the manufacture of generics. Pertinent questions include whether modafinil may be modified or manufactured to avoid the granularities specified in the new Cephalon patent, and whether patenting particle size is invalid because particles of appropriate sizes are likely to be obvious to practitioners skilled in the art. However, under United States patent law, a patent is entitled to a legal presumption of validity, meaning that in order to invalidate the patent, much more than "pertinent questions" are required. To date, no generic manufacturer has been able to invalidate Cephalon's particle size patent, and, indeed, those that attempted to do so were not successful such that the patent remains in force.

Cephalon made an agreement with four major generics manufacturers Teva, Barr Pharmaceuticals, Ranbaxy Laboratories, Mylan Inc, and Carlsbad Technologies/Watson Pharmaceuticals between 2005-2006 to delay sales of generic modafinil in the US until April 2012 by these companies in exchange for upfront and royalty payments.[96] Litigation arising from these agreements is still pending including an FTC suit filed in April 2008.[97] Apotex received regulatory approval in Canada despite a suit from Cephalon's marketing partner in Canada, Shire Pharmaceuticals.[98] [99]

Legal status

Modafinil is currently[update] classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance under United States federal law; it is illegal to import by anyone other than a DEA-registered importer without a prescription.[100] However, one may legally bring up to 50 dosage units (i.e. pills) of Modafinil to the United States in person from a foreign country, provided that he or she has a prescription for it, and the drug is properly declared at the border crossing.[101] Note that Adrafinil, a drug that is closely related to Modafinil, is currently not classified as a controlled substance, and therefore it is not as severely regulated.

The following countries do not classify Modafinil as a controlled substance:

- Canada (not listed in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, but it is a Schedule F prescription drug[102], so it is subject to seizure by Canada Customs)

- Mexico[103]

- United Kingdom (not listed in the Misuse of Drugs Act and is available by prescription without legal restrictions)[104]

- Australia (listed as a Schedule 4 prescription drug)

- In Germany the classification has been changed from controlled substance (BtM) to prescription drug (RP) effective March 1, 2008.

- In India, generic retailing as Modalert is available from Sun Pharmaceuticals; Indian firms are not required to respect patents filed before 1995.

Currently, use of modafinil is controversial in the sporting world, with high profile cases attracting press coverage since several prominent American athletes have tested positive for the substance (see Modafinil as a doping agent). Some athletes who were found to have used modafinil protested that the drug was not on the prohibited list at the time of their offenses. However, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains that it was related to already banned substances. The Agency added modafinil to its list of prohibited substances on August 3, 2004, ten days before the start of the 2004 Summer Olympics.

See also

- Adrafinil, prodrug to modafinil

- Armodafinil, the (−)-(R)-modafinil stereoisomer

- Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder

- CRL-40941

- Eugeroic

- Orexin-A

- Human reliability

- Hypopnea syndrome

- Narcolepsy

- Nootropics

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

- Shift work sleep disorder (SWSD)

- Sleep apnea

- Sleep disorder

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Erman MK, Rosenberg R, For The U S Modafinil Shift Work Sleep Disorder Study Group. "Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with chronic shift work sleep disorder: effects on patient functioning and health-related quality of life." Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2007;9(3):188-94. Full Text

- ^ Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, Hughes RJ, Wright KP, Kingsbury L, Arora S, Schwartz JRL, Niebler GE, Dinges DF (2005). "Modafinil for Excessive Sleepiness Associated with Shift-Work Sleep Disorder". N Engl J Med. 353 (5): 476–486. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041292. PMID 16079371.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Provigil (Modafinil) Site." 24 December 1998 [1].

- ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE66L5ZN20100722

- ^ Gerrard, P. Malcolm, R. (2007). "Mechanisms of Modafinil: A Review of Current Research". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–64. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. (2008). "Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1477–502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ishizuka T, Murakami M, Yamatodani A (2008). "Involvement of central histaminergic systems in modafinil-induced but not methylphenidate-induced increases in locomotor activity in rats". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 578 (2–3): 209–15. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.009. PMID 17920581.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Engber TM, Koury EJ, Dennis SA, Miller MS, Contreras PC, Bhat RV (1998). "Differential patterns of regional c-Fos induction in the rat brain by amphetamine and the novel wakefulness-promoting agent modafinil". Neurosci. Lett. 241 (2–3): 95–8. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00962-2. PMID 9507929.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Zhu W, Telang F, Wang GJ, Jayne M, Hooker JM, Wong C, Hubbard B, Carter P, Warner D, King P, Shea C, Xu Y, Muench L, Apelskog-Torres K (2009). "Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications". JAMA. 2009 Mar 18;301(11):1148-54. 301 (11): 1148–54. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.351. PMC 2696807. PMID 19293415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Myrick, Hugh; Malcolm, R; Taylor, B; Larowe, S (2004-04-01). "Modafinil: Preclinical, Clinical, and Post-Marketing Surveillance—A Review of Abuse Liability Issues". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 16 (2): 101–9. doi:10.1080/10401230490453743. PMID 15328903. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ V., DEROCHE-GAMONET; M., Darnaudéry; L., Bruins-Slot; F., Piat; Moal, M. Le; P., Piazza (2002). "Study of the addictive potential of modafinil in naive and cocaine-experienced rats". Psychopharmacologia. 161 (4): 387–395. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1080-8. PMID 12073166. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Biederman J, Pliszka SR (2008). "Modafinil improves symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across subtypes in children and adolescents". J. Pediatr. 152 (3): 394–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.07.052. PMID 18280848.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Arora S, Hughes RJ (2007). "Modafinil augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy in MDD partial responders with persistent fatigue and sleepiness". Ann Clin Psychiatry. 19 (3): 153–9. doi:10.1080/10401230701464858. PMID 17729016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://medicine.journalfeeds.com/psychiatry/neuropsychopharmacology/modafinil-blocks-reinstatement-of-extinguished-opiate-seeking-in-rats-mediation-by-a-glutamate-mechanism/20100716/

- ^ Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP (2005). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (1): 205–11. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. PMID 15525998.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Vliet SA, Vanwersch RA, Jongsma MJ, van der Gugten J, Olivier B, Philippens IH (2006). "Neuroprotective effects of modafinil in a marmoset Parkinson model: behavioral and neurochemical aspects". Behav Pharmacol. 17 (5–6): 453–62. doi:10.1097/00008877-200609000-00011. PMID 16940766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turner DC, Clark L, Pomarol-Clotet E, McKenna P, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2004). "Modafinil improves cognition and attentional set shifting in patients with chronic schizophrenia". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (7): 1363–73. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300457. PMID 15085092.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rammohan KW, Rosenberg JH, Lynn DJ, Blumenfeld AM, Pollak CP, Nagaraja HN (2002). "Efficacy and safety of modafinil (Provigil) for the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a two centre phase 2 study". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 72 (2): 179–83. doi:10.1136/jnnp.72.2.179. PMC 1737733. PMID 11796766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rabkin JG, McElhiney MC, Rabkin R, Ferrando SJ (2004). "Modafinil treatment for fatigue in HIV+ patients: a pilot study". J Clin Psychiatry. 65 (12): 1688–95. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n1215. PMID 15641875.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987 (PDMA), PL 100-293 Link

- ^ FDA Letter to Cephalon 01/03/2002

- ^ "Cephalon executives have repeatedly said that they do not condone off-label use of Provigil, but in 2002 the company was reprimanded by the FDA for distributing marketing materials that presented the drug as a remedy for tiredness, "decreased activity" and other supposed ailments. And in 2008 Cephalon paid $425m and pleaded guilty to a federal criminal charge relating to its promotion of off-label uses for Provigil and two other drugs." http://www.law360.com/articles/127434

- ^ News Release (Cephalon). "Cephalon, Inc. Plans to Acquire France's Group Lafon." WEST CHESTER, Pa., December 3, 2001 (PR Newswire) Link

- ^ a b Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ (2003). "Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 165 (3): 260–9. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1250-8. PMID 12417966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Randall DC, Viswanath A, Bharania P, Elsabagh SM, Hartley DE, Shneerson JM, File SE (2005). "Does modafinil enhance cognitive performance in young volunteers who are not sleep-deprived?". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 25 (2): 175–9. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000155816.21467.25. PMID 15738750.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Baranski JV, Pigeau R, Dinich P, Jacobs I (2004). "Effects of modafinil on cognitive and meta-cognitive performance". Hum Psychopharmacol. 19 (5): 323–32. doi:10.1002/hup.596. PMID 15252824.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Müller U, Steffenhagen N, Regenthal R, Bublak P (2004). "Effects of modafinil on working memory processes in humans". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 177 (1–2): 161–9. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1926-3. PMID 15221200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Randall DC, Shneerson JM, File SE (2005). "Cognitive effects of modafinil in student volunteers may depend on IQ". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 82 (1): 133–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2005.07.019. PMID 16140369.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jenner, P; Zeng, B.-Y.; Smith, L.A.; Pearce, R.K.B.; Tel, B.; Chancharme, L.; Moachon, G. (July 2000). "Antiparkinsonian and neuroprotective effects of modafinil in the mptp-treated common marmoset". Experimental Brain Research. 133 (2): 178–188. doi:10.1007/s002210000370.

- ^ Modafinil treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression: an open-label pilot study, Journal of affective disorders, 2004 August;81(2):173-8.

- ^ http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2010/more/06/21/usada.violations.ap/

- ^ Rammohan, K W; Rosenberg, JH; Lynn, DJ; Blumenfeld, AM; Pollak, CP; Nagaraja, HN (2002). "Efficacy and safety of modafinil (Provigil) for the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a two centre phase 2 study". Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 72 (2): 179–183. doi:10.1136/jnnp.72.2.179. PMC 1737733. PMID 11796766.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ Lindsay SE, Gudelsky GA, Heaton PC (2006). "Use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Ann Pharmacother. 40 (10): 1829–33. doi:10.1345/aph.1H024. PMID 16954326.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (transcript)". FDA. 2006-03-23.

- ^ "Modafinil (CEP-1538) Tablets Supplemental NDA 20-717/S-019 ADHD Indication Briefing Document for Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting" (PDF). FDA. 2006-03-23. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Xiong, M.D., Glen L.; Christopher, EJ; Goebel, J (2005). "Modafinil as an Alternative to Methylphenidate as Augmentation for Depression Treatment". Psychosomatics. 46 (6). Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine: 578–579. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.6.578. PMID 16288139.

Case report: Modafinil 200 mg daily replacing Methylphenidate 5 mg b.i.d in 78 year old cardiac patient

- ^ Menza, MA; Kaufman, KR; Castellanos, A (2000). "Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (5): 378–381. PMID 10847314.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ DeBattista, C; Lembke, A; Solvason, HB; Ghebremichael, R; Poirier, J (2004). "A prospective trial of modafinil as an adjunctive treatment of major depression". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24 (1): 87–90. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000104910.75206.b9. PMID 14709953.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ MacDonald, JR; H; T (24 December 2002). "Modafinil reduces excessive somnolence and enhances mood in patients with myotonic dystrophy". Neurology. 59 (12): 1876–1880. PMID 12499477.

- ^ Webster, L; Andrews, M; Stoddard, G (June 2003). "Modafinil treatment of opioid-induced sedation". Pain Med. 4 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03014.x. PMID 12873263.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ Hurst, DL; Lajara-Nanson, W (March 2002). "Use of modafinil in cerebral palsy". J Child Neurology. 17 (3): 169–172. doi:10.1177/088307380201700303. PMID 12026230.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ Nieves, AV; Lang, AE (March 2002). "Treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with Parkinson's disease with modafinil". Clin. Neuropharmacol. 25 (2): 111–114. doi:10.1097/00002826-200203000-00010. PMID 11981239.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ a b Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Gunderson E, Foltin RW (2006). "Modafinil attenuates disruptions in cognitive performance during simulated night-shift work". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (7): 1526–36. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300991. PMID 16395298.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ O'Connor, Anahad (2004-06-29). "Wakefulness Finds a Powerful Ally". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ http://www.miemss.org/home/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=WKeNmP-DJ9w%3d&tabid=106&mid=534

- ^ "Are 'smart drugs' safe for students?". The Guardian. London. 2010-04-06. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- ^ Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP (2005). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (1): 205–11. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. PMID 15525998.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Umanoff DF (2005). "Trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (12): 2298, author reply 2299–300. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300866. PMID 16294193.

- ^ Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP (2005). "Reply: Do Self-Reports Reliably Assess Abstinence in Cocaine-Dependent Patients?". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (12): 2299–300. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300867.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Henderson, David; Louie, Pearl; Koul, Pamposh; Namey, Leah; Daley, Tara; Nguyen, Dana (April–June 2005). "Modafinil-Associated Weight Loss in a Clozapine-Treated Schizoaffective Disorder Patient". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry;. 17 (2): 95–97. doi:10.1080/10401230590932407.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Efficacy and Safety of Modafinil Film-Coated Tablets in Children and Adolescents

- ^ Vaishnavi S, Gadde K, Alamy S, Zhang W, Connor K, Davidson JR (2006). "Modafinil for atypical depression: effects of open-label and double-blind discontinuation treatment". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 26 (4): 373–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000227700.263.75.39. PMID 16855454.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thase ME, Fava M, DeBattista C, Arora S, Hughes RJ (2006). "Modafinil augmentation of SSRI therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and excessive sleepiness and fatigue: a 12-week, open-label, extension study". CNS Spectr. 11 (2): 93–102. PMID 16520686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Makris AP, Rush CR, Frederich RC, Kelly TH (2004). "Wake-promoting agents with different mechanisms of action: comparison of effects of modafinil and amphetamine on food intake and cardiovascular activity". Appetite. 42 (2): 185–95. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2003.11.003. PMID 15010183.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 11613_Provigil_PI_4pgr_lo4.indd

- ^ "Doctors are finding it harder to deny 'Chemobrain'", The Virginian-Pilot, © October 2, 2007.

- ^ Modafinil Relieves Cognitive Chemotherapy Side Effects Psychiatric News, Stephanie Whyche, August 3, 2007 Volume 42 Number 15, page 31

- ^ Banerjee D, Vitiello MV, Grunstein RR (2004). "Pharmacotherapy for excessive daytime sleepiness". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (5): 339–54. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.03.002. PMID 15336235.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Modafinil". NIH. 2005-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ "FDA Approved Labeling Text for Provigil" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2004-01-23.

- ^ "Successful treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy with modafini", http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2906157

- ^ "Modafinil (marketed as Provigil): Serious Skin Reactions". FDA. 2007.

- ^ BBC report on MoD research into Modafinil

- ^ MoD's secret pep pill to keep forces awake

- ^ Modafinil and Management of Aircrew Fatigue - United States Air Force memo

- ^ The Effects of Modafinil on Aviator Performance During 40 Hours of Continuous Wakefulness

- ^ The efficacy of Modafinil for sustaining alertness and simulator flight performance in F-117 pilots during 37 hours of continuous wakefulness

- ^ A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Investigation of the Efficacy of Modafinil for Maintaining Alertness and Performance in Sustained Military Ground Operations

- ^ http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/reprint/180/12/1216

- ^ Dopheide MM, Morgan RE, Rodvelt KR, Schachtman TR, Miller DK (2007). "Modafinil evokes striatal [(3)H]dopamine release and alters the subjective properties of stimulants". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 568 (1–3): 112–23. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.03.044. PMID 17477916.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Murillo-Rodríguez E, Haro R, Palomero-Rivero M, Millán-Aldaco D, Drucker-Colín R (2007). "Modafinil enhances extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and increases wakefulness in rats". Behav. Brain Res. 176 (2): 353–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.016. PMID 17098298.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Saint Hilaire Z, Orosco M, Rouch C, Blanc G, Nicolaidis S (2001). "Variations in extracellular monoamines in the prefrontal cortex and medial hypothalamus after modafinil administration: a microdialysis study in rats". Neuroreport. 12 (16): 3533–7. doi:10.1097/00001756-200111160-00032. PMID 11733706.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gallopin T, Luppi PH, Rambert FA, Frydman A, Fort P (2004). "Effect of the wake-promoting agent modafinil on sleep-promoting neurons from the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus: an in vitro pharmacologic study". Sleep. 27 (1): 19–25. PMID 14998233.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferraro L, Fuxe K, Tanganelli S, Tomasini MC, Rambert FA, Antonelli T (2002). "Differential enhancement of dialysate serotonin levels in distinct brain regions of the awake rat by modafinil: possible relevance for wakefulness and depression". J. Neurosci. Res. 68 (1): 107–12. doi:10.1002/jnr.10196. PMID 11933055.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ishizuka T, Sakamoto Y, Sakurai T, Yamatodani A (2003). "Modafinil increases histamine release in the anterior hypothalamus of rats". Neurosci. Lett. 339 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00006-5. PMID 12614915.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. (199). "Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation". Cell. 98 (4): 437–51. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81973-X. PMID 10481909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Miller MS, Saper CB. (2000). "Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness". J Neurosci. 20 (22): 8620–8628. PMID 11069971.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Willie JT, Renthal W, Chemelli RM, Miller MS, Scammell TE, Yanagisawa M, Sinton CM. (2005). "Modafinil more effectively induces wakefulness in orexin-null mice than in wild-type littermates". Neuroscience. 130 (40): 983–95. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.005. PMID 15652995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Urbano F, Leznik E, Llinas R (2007). "Modafinil enhances thalamocortical activity by increasing neuronal electrotonic coupling". PNAS. 104 (30): 12554–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705087104. PMC 1925036. PMID 17640897.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Garcia-Rill E, Heister D, Ye Meijun, Charlesworth A, Hayar A (2007). "Electrotonic coupling: novel mechanism for sleep-wake control". Sleep. 30 (11): 1405–14. PMC 2082101. PMID 18041475.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Template:Cite article

- ^ Minzenberg M, Watrous A, Yoon J, Ursu S, Carter C (2008). "Modafinil Shifts Human Locus Coeruleus to Low-Tonic, High-Phasic Activity During Functional MRI". Science. 322 (5908): 1700–2. doi:10.1126/science.1164908. PMID 19074351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Minzenberg M, Carter C (2007). "Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1477–1502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Beck P, Odle A, Wallace-Huitt T, Skinner RD, Garcia-Rill E (2008). "Modafinil increases arousal determined by P13 potential amplitude: an effect blocked by gap junction antagonists". Sleep. 31 (12): 1647–54. PMC 2603487. PMID 19090320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferraro L, Tanganelli s, o'Conoor W, Antonelli T, Rambert F, Fuxe K (1996). "The vigilance promoting drug modafinil increases dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens via the involvement of a local GABAergic mechanism". European Journal of Pharmacology. 306 (1–3): 33–9. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(96)00182-3. PMID 8813612.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19197004, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19197004instead. - ^ a b Seeman P, Guan HC, Hirbec H (2009). "Dopamine D2High receptors stimulated by phencyclidines, lysergic acid diethylamide, salvinorin A, and modafinil". Synapse (New York, N.Y.). 63 (8): 698–704. doi:10.1002/syn.20647. PMID 19391150.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE DATA: doi=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hardman, Joel and Limbird, Lee. 2001. "Goodman and Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics." Edition 10. pp 1984t. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Wong YN, King SP, Laughton WB, McCormick GC, Grebow PE. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of modafinil and methylphenidate given alone or in combination in healthy male volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 38(3): 276-282, 1998.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1152-1153.

- ^ "Dockets Entered On December 26, 2006". FDA. 2006-12-26. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

2005P-0265 Over-the Counter Sale of Modafinil

- ^ "Cephalon gets six-month Provigil patent extension". Philadelphia Business Journal. 2006-03-28. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ "Details for Patent: RE37516".

- ^ "Cephalon Inc., SEC 10K 2008 disclosure, pages=9–10". 23 February 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - ^ "CVS, Rite Aid Sue Cephalon Over Generic Provigil". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Canada IP Year in Review 2008". 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Shire v. Canada". Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Is It Illegal to Obtain Controlled Substances From the Internet?". United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ "USC 201 Section 1301.26 Exemptions from import or export requirements for personal medical use". United States Department of Justice. 1997-03-24.

- ^ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (1184 — Modafinil)" ([dead link] – Scholar search). Canada Gazette. 140 (20). 2006-10-04.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - ^ "Estupefacientes y Psicotrópicos" (in Spanish). Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Julia Llewellyn Smith (2004-01-06). "The 44-hour day". London: The Telegraph.

External links

- Provigil corporate website

- The New Yorker magazine December 3, 2001 "Eyes Wide Open" — (article about modafinil research by the U.S. military)

- "Brain Gain: The underground world of 'neuroenhancing' drugs" -(article about use of nootropics and other drugs in general)

- "Wake Up, Little Susie" article and reporter's diary on taking modafinil from March 7, 2003 Slate magazine

- "Get ready for 24-hour living" from 18 February 2006 New Scientist

- RxList Patient Information for modafinil users

- Minzenberg, Michael J.; Carter, Cameron S (2008). "Modafinil: A Review of Neurochemical Actions and Effects on Cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1477–502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350.

- "My experiment with smart drugs: Viagra for the brain?" -(essay by Johann Hari; online version of an Evening Standard article)

- "Mayo Clinic Proceedings Publishes Study of NUVIGIL in Patients with Shift Work Disorder"

- http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/DrJohnson/story?id=128275

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Modafinil

- "Judge slams FTC in pay-for-delay generic drug case" -(Reuters)