New England

| |

| Regional statistics | |

|---|---|

| Composition | |

| Demonym | New Englander, Yankee |

| Area - Total |

71,991.8 sq mi (186,458.8 km²) (Slightly larger than Washington.) |

| Population - Total - Density |

14,429,720 (2009 est.)[1] 198.2/sq mi (87.7/km²) |

| Largest city | Boston (pop. 645,169) |

| GDP | $763.7 billion (2007)[2] |

| Largest Metropolitan Area | Boston-Cambridge-Quincy (pop. 4,522,858) |

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. New England is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean, Canada, and the State of New York. lauren drayton In one of the earliest European settlements in North America, Pilgrims from England first settled in New England in 1620, to form Plymouth Colony. Ten years later, the Puritans settled north of Plymouth Colony in Boston, thus forming Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. In the late 18th century, the New England Colonies would be among the first North American British colonies to demonstrate ambitions of independence from the British Crown through the American Revolution, although they would later oppose the War of 1812 between the United States and United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

New England produced the first pieces of American literature and philosophy and was home to the beginnings of free public education. In the 19th century, it played a prominent role in the movement to abolish slavery in the United States. It was the first region of the United States to be transformed by the Industrial Revolution.

Today, New England is a major center of education, high technology, insurance, medicine, and tourism. It is known for its universities, historic cities and landmarks, and natural beauty.

Politically, the states of New England are largely divided into small, unique, incorporated municipalities known as New England towns, which are often governed by town meeting. Voters have voted more often for liberal candidates at the state and federal level than those of any other region in the United States.

New England has the only non-geographic regional name recognized by the federal government. It maintains a strong sense of cultural identity set apart from the rest of the country, although the terms of this identity are often contested, paradoxically combining Puritanism with liberalism, agrarian life with industry, and isolation with immigration.

History

Eastern Algonquin peoples

Present-day New England's earliest inhabitants were Native Americans who spoke a variety of the Eastern Algonquian languages. Some of the more prominent tribes include the Abenaki, the Penobscot, the Pequot, the Mohegans, the Pocumtuck, and the Wampanoag. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Western Abenakis inhabited New Hampshire and Vermont, as well as parts of Quebec and western Maine. Their principal town was Norridgewock, in present-day Maine. The Penobscot were settled along the Penobscot River in Maine. The Wampanoag occupied southeastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket; the Pocumtucks, Western Massachusetts. The Connecticut region was inhabited by the Mohegan and Pequot tribes prior to European colonization. The Connecticut River Valley, which includes parts of Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, linked different indigenous communities in cultural, linguistic, and political ways.[7]

According to archaeological evidence, the indigenous people of the warmer parts of Southern New England had started agricultural endeavers over a thousand years ago. They grew corn, tobacco, kidney beans, squash, and Jerusalem artichoke. Trade with the Algonquin peoples of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, where the growing season was shorter, likely provided for a robust economy.

As early as 1600, French, Dutch, and English traders, exploring the New World, began to trade metal, glass, and cloth for local beaver pelts.[7]

The Virginia Companies compete

On April 10, 1606, King James I of England issued two charters, one each for the Virginia Companies, of London and Plymouth, respectively.[8][9][10] Due to a duplication of territory (between Chesapeake Bay and Long Island Sound), the two companies were required to maintain a separation of 100 miles (160 km), even where the two charters overlapped.[8][9][10]

These were privately-funded proprietary ventures, and the purpose of each was to claim land for England, trade, and return a profit.[11] Competition between the two companies grew to where their potential New World territory overlapped, and would be finalized based upon results.

The London Company was authorized to make settlements from North Carolina to New York (31 to 41 degrees North Latitude), provided there was no conflict with the Plymouth Company’s charter.

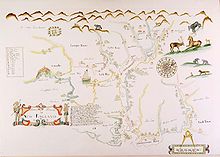

The Popham Colony was planted at the mouth of Maine's Kennebec River by the Virginia Company of Plymouth in the fall of 1607. Unlike the Jamestown Settlement, it was not successful, and was abandoned the following spring.[12] The Virginia Company of Plymouth's charter included land extending as far as present-day northern Maine.[13] Captain John Smith, exploring the shores of the region in 1614, named the region "New England"[14] in his account of two voyages there, published as A Description of New England.

The next notable settlement in New England took place in the winter of 1616-1617 at Winter Harbor, thenafter called Biddeford Pool, by Captain Richard Vines. This location is in current-day Biddeford, Maine. This 1616 landing at Saco Bay by a European pre-dates the Mayflower landing in Plymouth, Massachusetts (located 100 miles (160 km) to the south) by approximately four years.[15]

Plymouth Council for New England

The name "New England" was officially sanctioned on November 3, 1620,[16] when the charter of the Virginia Company of Plymouth was replaced by a royal charter for the Plymouth Council for New England, a joint stock company established to colonize and govern the region.[17] Shortly afterwards, in December 1620, a permanent settlement was established near present-day Plymouth by the Pilgrims, English religious separatists arriving via Holland, after they famously disembarked at Plymouth Rock. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, which would come to dominate the area, was established in 1628 with its major city of Boston established in 1630.

Banished from Massachusetts for heresy, Roger Williams led a group south, and founded Providence, Rhode Island in 1636. On March 3 of the same year, Thomas Hooker left Massachusetts and the Connecticut Colony was granted a charter, establishing its own government in Hartford. At this time, Vermont was yet unsettled, and the territories of New Hampshire and Maine were governed by Massachusetts.

Even during the early stages of English colonization, relations with the indigenous peoples of New England began to sour. Preliminary trade with Europeans had already significantly reduced and weakened native populations via disease and epidemic. The fur supply was soon exhausted, forcing hunters to travel farther into the territories of neighboring tribes, such as the Mohawk and the Haudenosaunee of Eastern New York. As demand for local goods, like beaver pelts, by English companies rose, so did tensions between existing indigenous communities. Permanent English settlement, through which colonists seized or claimed land and began to apply Puritan laws to native peoples, only exacerbated the situation.[7]

New England Confederation

In these early years, relationships between colonists and Native Americans alternated between peace and armed skirmishes. Six years after the bloodiest of these, the Pequot War in 1643, which resulted in the Mystic massacre, the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, New Haven, and Connecticut joined together in a loose compact called the New England Confederation (officially "The United Colonies of New England"). The confederation was designed largely to coordinate mutual defense against possible wars with Americans, the Dutch in the New Netherland colony to the west, the Spanish in the south, and the French in New France to the north, as well as to assist in the return of runaway slaves. The confederation lost its influence when Massachusetts refused to commit itself to a war against the Dutch.

In 1675, internecine conflict broke out amongst the Wampanoag of southeastern Massachusetts, soon drawing into it several other tribes. The New England Confederation, joined by the Pequot and the and the Mohegan tribes, declared war, and undertook what became known as King Philip's War. Thousands of colonists and natives, including women and children, met gruesome deaths. For well over a year, New Englanders lived in terror. In the meantime, the English militiae committed numerous atrocities against their enemies. The colonists were eventually victorious, executing or selling into slavery the remaining prisoners.[7]

The first coins struck in the Colonies, prompted by a shortage of change, were the New England coins produced by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The first series was a simple design including "NE" on the obverse and the various denominations on the reverse. Other series included the "Willow," "Oak," and "Pine Tree." The "Pine Tree" coinage was the last type in the series, struck by coiner John Hull. Although the majority were dated 1652, it is generally acknowledged that production spanned about thirty years, despite the disapproval of King Charles II.[18]

Since the New England colonies were settled largely by families and tradesmen, they became relatively self-sufficient. During this period, the Puritan work ethic, which defines a part of New England culture even to this day, prevailed. There were blacksmiths, wheelwrights, carpenters, joiners, cordwainers, tanners, ironworkers, spinners, and weavers, when someone needed something - unlike the Southern colonies, who had to buy these items from England.[19]

Dominion of New England

In 1686, King James II, concerned about the increasingly independent ways of the colonies, including their self-governing charters, open flouting of the Navigation Acts, and increasing military power, established the Dominion of New England, an administrative union comprising all of the New England colonies. On August 11, 1688,[20] the provinces of New York and New Jersey, seized from the Dutch in 1664, and confirmed on September 12, 1673, were added.[20] The union, imposed from the outside and contrary to the rooted democratic tradition of the region, was highly unpopular among the colonists.

Nevertheless, those two present states are reckoned as "greater New England" in a social or cultural context, as that is where Yankee colonists expanded to; before 1776. Cultural identity in that era changed once one moved to Pennsylvania, as the Pennamite-Yankee War attests to. Colonists from New England proper in that era, were rather well received in the Mohawk Valley and on Long Island in New York.

After the Glorious Revolution in 1689, Bostonians imprisoned the Royal Governor and other sympathizers of King James II on April 18, 1689, thus ending the Dominion Of New England de facto.[21][22] The charters of the colonies were significantly modified after this change in English politics, with the appointment of Royal Governors to nearly every colony. An uneasy tension existed between the Royal Governors, their officers, and the elected governing bodies of the colonies. The governors wanted unlimited authority, and the different layers of locally elected officials would often resist them. In most cases, the local town governments continued operating as self-governing bodies, just as they had before the appointment of the Royal Governors. This tension culminated itself in the American Revolution, boiling over with the breakout of the American War of Independence in 1775. The first battles of the war were fought in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, eventually leading to the Siege of Boston by continental troops. Today, Evacuation Day is still celebrated in Suffolk County, Massachusetts to commemorate the departure of British troops from Boston.

Region of the United States

After the War of Independence, New England ceased to be a meaningful political unit, but remained a defined historical and cultural region consisting of its now-sovereign constituent states. By 1784, all of the states in the region had introduced the gradual abolition of slavery, with Vermont and Massachusetts introducing total abolition in 1777 and 1783, respectively.[23] During the War of 1812, there was a limited amount of talk of secession from the Union, as New England merchants, just getting back on their feet, opposed the war with their greatest trading partner—Great Britain.[24] Delegates from all over New England met in Hartford in the winter of 1814-15. The gathering was called the Hartford Convention. The twenty-seven delegates met to discuss changes to the US Constitution that would protect the region from similar legislation and attempt to keep political power in the region.

In 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, the territory of Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a state. Today, New England is always defined as coextensive with the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.[25]

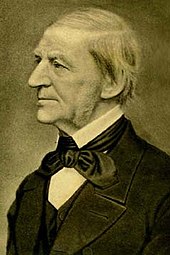

For the remainder of the antebellum period, New England remained distinct. In terms of politics, it often went against the grain of the rest of the country. Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the last refuges of the Federalist Party, and, when the Second Party System began in the 1830s, New England became the strongest bastion of the new Whig Party. The Whigs were usually dominant throughout New England, except in the more Democratic Maine and New Hampshire. Leading statesmen — including Daniel Webster — hailed from the region. New England was distinct in other ways. It was, as a whole, the most urbanized part of the country (the 1860 Census showed that 32 of the 100 largest cities in the country were in New England), as well as the most educated. Notable literary and intellectual figures produced by the United States in the Antebellum period were New Englanders, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, George Bancroft, William H. Prescott, and others.

New England was an early center of the industrial revolution.[26]

The Blackstone Valley has been called the birthplace of America's industrial revolution.[27] In the North Shore seaport of Beverly, Massachusetts the first cotton mill in America was founded in 1787, the Beverly Cotton Manufactory.[28] The Manufactory was also considered the largest cotton mill of its time. Technological developments and achievements from the Manufactory led to the development of other, more advanced cotton mills later, including Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Several textile mills were already underway during the time. Towns like Lawrence, Massachusetts, Lowell, Massachusetts, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Lewiston, Maine became famed as centers of the textile industry following models from Slater Mill and the Beverly Cotton Manufactory. The textile manufacturing in New England was growing rapidly, which caused a shortage of workers. Recruiters were hired by mill agents to bring young women and children from the countryside to work in the factories. Between 1830 and 1860, thousands of farm girls came from their rural homes in New England to work in the mills. Farmers’ daughters left their homes to aid their families financially, save for marriage, and widen their horizons. They also left their homes due to population pressures to look for opportunities in expanding New England cities. Stagecoach and railroad services made it easier for the rapid flow of workers to travel from the country to the city. The majority of female workers came from rural farming towns in northern New England. As the textile industry grew, immigration grew as well. As the number of Irish workers in the mills increased, the number of young women working in the mills decreased. Mill employment of women caused a population boom in urban centers.[29]

New England and areas settled from New England, like Upstate New York, Ohio's Western Reserve and the upper midwestern states of Michigan and Wisconsin, proved to be the center of the strongest abolitionist sentiment in the country. Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips were New Englanders, and the region was home to anti-slavery politicians like John Quincy Adams, Charles Sumner, and John P. Hale. When the anti-slavery Republican Party was formed in the 1850s, all of New England, including areas that had previously been strongholds for both the Whig and the Democratic Parties, became strongly Republican, as it would remain until the early 20th century, when immigration would begin to turn the formerly solidly Republican states of Lower New England towards the Democrats.

Geography

New England's long rolling hills, mountains, and jagged coastline are glacial landforms resulting from the retreat of ice sheets approximately 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial period. The coast of the region, extending from southwestern Connecticut to northeastern Maine, is dotted with lakes, hills, swamps, and sandy beaches. Further inland are the Appalachian Mountains, extending through Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Among them, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire is Mount Washington, which at 1,917 m (6,289 ft), is the highest peak in the northeast United States. It is the site of the highest recorded wind speed on Earth.[30] Vermont's Green Mountains, which become the Berkshire Hills in western Massachusetts and Connecticut, are smaller than the White Mountains. Valleys in the region include the Connecticut River Valley and the Merrimack Valley.

The longest river is the Connecticut River, which flows from northeastern New Hampshire for 655 km (407 mi), emptying into Long Island Sound, roughly bisecting the region. Lake Champlain, wedged between Vermont and New York, is the largest lake in the region, followed by Moosehead Lake in Maine and Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire.

Climate

Weather patterns vary throughout the region. Most of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont have a humid continental short summer climate ,[31] with mild summers and cold winters. Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Southern New Hampshire and Vermont, and Coastal Maine have a humid continental long summer climate,[31] with warm summers and cold winters. Owing to thick deciduous forests, fall in New England brings bright and colorful foliage, which comes earlier than in other regions, attracting tourism by 'leaf peepers'.[32] Springs are generally wet and cloudy. Average rainfall generally ranges from 1,000 to 1,500 mm (40 to 60 in) a year, although the northern parts of Vermont and Maine see slightly less, from 500 to 1,000 mm (20 to 40 in). Snowfall can often exceed 2,500 mm (98 in) annually. As a result, the mountains and ski resorts of Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont are popular destinations in the winter.[26][33]

The lowest recorded temperature in New England was −50 °F (−46 °C) at Bloomfield, Vermont, on December 30, 1933. This was tied by Big Black River, Maine in 2009.[34]

The area is geologically part of the New England province.

Demographics

According to the 2006-2008 American Community Survey, New England had a population of 14,265,187, of which 48.7% were male and 51.3% were female. Approximately 22.4% of the population were under 18 years of age; 13.5% were over 65 years of age.

In terms of race and ethnicity, White Americans made up 84.9% of New England's population, of which 81.2% were whites of non-Hispanic origin. Black Americans comprised 5.7% of the region's population, of which 5.3% were blacks of non-Hispanic origin. Native Americans made up only 0.3% of the population; they numbered at 37,234. There were just over 500,000 Asian Americans residing in New England at the time of the survey. Americans of Asian origin form 3.5% of the region's population. Chinese Americans formed 1.1% of the region's total population, and numbered at 158,282. Indian Americans made up 0.8% of the populace, and numbered at 119,140. Japanese Americans numbered very little; only 14,501 residents of New England were of Japanese descent, equivalent to just 0.1% of the population.

Pacific Islander Americans were even fewer. Only 4,194 people were members of this group, equivalent to 0.03% of the populace. There were only 138 Samoan Americans residing in the region. Multiracial Americans made up 1.8% of New England's population. The largest mixed-race group were those of African and European descent; there were 84,143 people of black and white ancestry, equal to 0.6% of the population. People of Native American and European American ancestry made up 0.4% of the population. People of Asian and European heritage made up 0.3% of the population.

Hispanic and Latino Americans are New England's largest minority, and they are the second-largest group in the region behind non-Hispanic European Americans. Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 7.9% of New England's population, and there were over 1.1 million Hispanic and Latino individuals reported in the survey. Puerto Ricans were the most numerous of the Hispanic and Latino subgroups. Over half a million (507,000) Puerto Ricans live in New England, forming 3.6% of the population. Just over 100,000 Mexican Americans make New England their home. The Dominican population is more than 70,000.[36] Americans of Cuban descent are scant in number; there were roughly 20,000 Cuban Americans in the region. People of other Hispanic and Latino ancestries (e.g. Salvadoran, Colombian, Bolivian, etc.) formed 3.5% of New England's population, and exceeded 492,000 in number.[37]

New England's European American population is ethnically diverse. The majority of the Euro-American population is of Irish, Italian, English, French, and German descent. Smaller, but significant populations of Poles, French Canadians, and Portuguese exist as well.

According to the 2006-2008 survey, the top ten largest European ancestries were the following:

- Irish: 21.1% (Over 3 million)

- Italian: 14.4% (Over 2 million)

- English: 13.7% (1.9 million)

- French: 10.4% (1.5 million)

- German: 8.2% (1.2 million)

- Polish: 5.6% (Roughly 800,000)

- French Canadian: 4.9% (Roughly 700,000)

- Portuguese: 3.5% (Over 500,000)

- Scottish: 3.1% (Over 440,000)

- Scotch-Irish: 2.1% (Over 290,000)

English is, by far, the most commonly spoken language at home by inhabitants. Approximately 82.7% of all residents (11.1 million people) over the age of five spoke English only at home. The remaining 17.3% of the population spoke non-English languages at home. Roughly 885,000 people (6.6% of the population) spoke Spanish at home. Roughly 1,023,000 people (7.6% of the population) spoke other Indo-European languages at home. In addition, over 313,000 people (2.3% of the population) spoke an Asian or Pacific Island language at home. Roughly 99,000 people (0.7% of the population) spoke other languages at home.

The vast majority of New England's inhabitants are native to the United States. However, there is a significant foreign-born population in the region. Roughly 12.3 million people (86.3% of the population) were born in the United States. In addition, 2.2% of the population (315,000 people) were born in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, or abroad to American parents. Altogether, the native population totals at roughly 12,630,000 people, or 88.5% of the population. The foreign-born population forms over ten percent (11.5%) of New England's total population. There are roughly 1.6 million foreigners residing in the region. Thirty-five percent of foreigners were born in Latin America, 27.9% were born in Europe, 24.5% were born in Asia, and 6.9% were born in Africa. People born in other parts of North America made up 5.3% of the foreign-born populace. Oceania-born residents formed only 0.4% of the foreign population, and numbered just over 6,000. Of the 1.6 million foreigners, 47.7% were naturalized citizens of the U.S. and the majority (52.3%) were not U.S. citizens.[38]

In 2005, the total population of New England was 14,239,724 people, roughly a 50% increase from its 1929 population of 9,813,000.[39] The region's average population density is 221.66 inhabitants/sq mi (85.59/km²), although a great disparity exists between its northern and southern portions, as noted below. It is much greater than that of the United States as a whole (79.56/sq mi) or even just the contiguous 48 states (94.48/sq mi).

In 2009, two states were among the five highest in the country in divorce rates. Maine was second highest with 13.6% of people over 15 divorced; Vermont was fifth with 12.6% divorced.[40] Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, on the other hand, have below-average divorce rates. Massachusetts is tied with Georgia with the lowest divorce rate in the U.S., at 2.4%.[41]

Three-quarters of the population of New England and most of the major cities are in the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Their combined population density is 786.83/sq mi, compared to northern New England's 63.56/sq mi (2000 census). The most populous state is Massachusetts, and the most populous city is Massachusetts' political and cultural capital, Boston.

The coastline is more urban than western New England, which is typically rural, even in urban states like Massachusetts. This characteristic of the region's population is due mainly to historical factors; the original colonists settled mostly on the coastline of Massachusetts Bay. The only New England state without access to the Atlantic Ocean, Vermont, is also the least urbanized.[42] After nearly 400 years, the region still maintains, for the most part, its historical population layout.

New England's coast is dotted with urban centers, such as Portland, Portsmouth, Boston, New Bedford, Fall River, Providence, New Haven, Bridgeport, and Stamford as well as smaller cities, like Newburyport, Gloucester, Biddeford, Bath, Rockland, Newport, Westerly, Rhode Island, and the small twin cities of Groton, Connecticut and New London.

Southern New England forms an integral part of the BosWash megalopolis, a conglomeration of urban centers that spans from Boston to Washington, D.C.. The region includes three of the four most densely populated states in the United States; only New Jersey has a higher population density than the states of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Greater Boston, which includes parts of southern New Hampshire, has a total population of approximately 4.4 million,[43] while over half the population of New England falls inside Boston's Combined Statistical Area of over 7.4 million.[44] The most populous cities are as of 2000 Census (2008 estimates in parenthesis):[45][46]

- Boston, Massachusetts: 589,141[47] (620,535)

- Providence, Rhode Island: 173,618 (171,557)

- Worcester, Massachusetts: 172,648 (182,596)

- Springfield, Massachusetts: 152,082 (150,640)

- Bridgeport, Connecticut: 139,529 (136,405)

- Hartford, Connecticut: 124,558 (124,062)

- New Haven, Connecticut: 123,626 (123,669)

- Stamford, Connecticut: 117,083 (119,303)

- Waterbury, Connecticut: 107,271 (107,037)

- Manchester, New Hampshire: 107,006 (108,586)

- Lowell, Massachusetts: 105,167 (103,615)

- Cambridge, Massachusetts: 101,355 (105,596)

During the 20th century, urban expansion in regions surrounding New York City has become an important economic influence on neighboring Connecticut, parts of which belong to the New York Metropolitan Area. The US Census Bureau groups Fairfield, New Haven and Litchfield counties in western Connecticut together with New York City, and other parts of New York and New Jersey as a combined statistical area.[48]

Public health and safety

In 2006, Massachusetts adopted health care reform that requires nearly all state residents obtain health insurance.[49] In 2009, the Connecticut legislature overrode a veto by Governor M. Jodi Rell to pass SustiNet, the first significant public-option health care reform legislation in the nation.[citation needed]

The six states ranked within the top thirteen "healthiest states" in 2007.[50] In 2008, they all placed within the top eleven states. New England had the largest proportion of its population covered by health insurance.[51]

For 2006, four states in the region, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, joined 12 others nationwide, where death from drugs had overtaken traffic fatalities. This was due in part to declining traffic fatalities and partly due to increased deaths from prescription drugs.[52]

In comparing national obesity rates by state, four of the six lowest obesity states were Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and Rhode Island. New Hampshire and Maine had the 15th and 18th lowest obesity rates, making New England the least overweight part of the United States.[53]

In 2008, three of New England's states had the least number of uninsured motorists (out of the top five states) - Massachusetts - 1%, Maine - 4%, and Vermont - 6%.[54]

Nursing home care can be expensive in the region. A private room in Connecticut averaged $125,925 annually. A one-bedroom in an assisted living facility averaged $55,137 in Massachusetts. Both are national highs.[55]

Economy

Overview

Several factors contribute to the uniqueness of the New England economy. The region is geographically isolated from the rest of the United States, and is relatively small. It has a climate and a supply of natural resources (such as granite, lobster, and codfish) that are different from other parts of the country. Its population is concentrated on the coast and in its southern states, and its residents have a strong regional identity.[57] America's textile industry began along the Blackstone River with the Slater Mill at Pawtucket, Rhode Island.[58] This was soon duplicated at similar sources of water power such as Woonsocket, Rhode Island, Uxbridge, Massachusetts, and the manufacturing centers of Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts.

In the early 20th century, the region underwent a long period of deindustrialization as traditional manufacturing companies relocated to the Midwest. In the mid-to-late 20th century, manufacturing was replaced by education, health services, finance, and high technology (including computer and electronic equipment manufacturing) as the region's most important economic motors.

As of 2007, the inflation-adjusted combined GSPs of the six states of New England was $763.7 billion, with Massachusetts ($365 billion) contributing the most, and Vermont ($25.4 billion) the least.[59]

Exports

Exports consist mostly of industrial products, including specialized machines and weaponry (aircraft and missiles especially), built by the region's educated workforce. About half of the region's exports consist of industrial and commercial machinery, such as computers and electronic and electrical equipment. This, when combined with instruments, chemicals, and transportation equipment, makes up about three-quarters of the region's exports. Granite is quarried at Barre, Vermont,[60] guns made at Springfield, Massachusetts and Saco, Maine, boats at Groton, Connecticut and Bath, Maine, and hand tools at Turners Falls, Massachusetts. Insurance is a driving force in and around Hartford, Connecticut.[57]

New England exports food products, ranging from fish to lobster, cranberries, Maine potatoes, and maple syrup. The service industry is important, including tourism, education, financial and insurance services, plus architectural, building, and construction services. The U.S. Department of Commerce has called the New England economy a microcosm for the entire United States economy.[57]

Manufacturing

In 2010, a University of Connecticut study indicated that five of the six states rank 43rd or lower as costliest for manufacturing. Only Maine was less costly. Vermont, Rhode Island and New Hampshire tied for last place.[61]

Agriculture

Agriculture is limited by the area's rocky soil and cooler climate. Some New England states, however, are ranked highly among U.S. states for particular areas of production. Maine is ranked ninth for aquaculture,[62] and has abundant potato fields in its northeast part. Vermont fifteenth for dairy products,[63] and Connecticut and Massachusetts seventh and eleventh for tobacco, respectively.[64][65] Cranberries are grown in Massachusetts' Cape Cod-Plymouth-South Shore area, and blueberries in Maine.

Energy

The region is mostly very energy efficient compared to the country at large. Rhode Island has the lowest per capita energy consumption of any state in the country and five of the New England states placed in the lowest eleven. Maine, by contrast, had the 17th-highest per capita consumption.[66]

Maine is leading New England in wind power production, and the state's agenda states that by 2030, the state will produce twice the amount of energy in wind power than it consumes.[67] Three of the six New England states are among the country's highest consumers of nuclear power: Vermont (first, 73.7%), Connecticut (fourth, 48.9%), and New Hampshire (sixth, 46%).[68]

The six New England states, as of 2008, collectively have the highest electricity costs in the nation. The lowest rates are in Vermont, which stands at 41st in the country; Rhode Island is ranked 50th (out of 51) with the highest rates in the region.[69]

Employment

As of June 2010, the unemployment rate in New England was 8.6%, below the national average. New Hampshire, with the lowest of the six states, had a rate of 5.9%. The highest was Rhode Island, with 12.0%. As of May 2010, the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) with the lowest rate, 4.8%, was Burlington-South Burlington, Vermont; the MSA with the highest rate, 14.6%, was Lawrence-Methuen-Salem, in Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire.[70]

According to the 2000 census, New England has two of the ten poorest cities (by percentage living below the poverty line) in the United States: the state capital cities of Providence, Rhode Island and Hartford, Connecticut.[71] These cities have struggled as manufacturing, their traditional economic mainstay, has declined.[72] On the other hand, New Hampshire, as of 2008, had the lowest poverty rate in the United States.[73]

Politics

The early European settlers of New England were English Protestants fleeing religious persecution. This, however, did not prevent them from establishing colonies where religion was legislated to an extreme, and where those who deviated from the established doctrine were persecuted greatly. The early history of much of New England is marked by religious intolerance and harsh laws. In the beginning, there was no separation of church and state in these places, and the activities of the individual were severely restricted.[74] This contrasts sharply with the strong separation of church and state upon which Rhode Island was founded. Providence had no public burial ground and no Common until the year 1700 (64 years after its founding) because religious and government institutions were so rigorously kept distinct.[75]

Contemporary politics

New England today is politically a relatively liberal region. Since 1962, the dominant party in New England has been the Democratic Party. In every New England state, both legislative houses have a majority of Democratic representatives. Since 2006, the parties have split the governor's positions with Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts being Democratic and Connecticut, Rhode Island and Vermont being held by Republicans. The latter three states have legislatures with veto-overriding Democratic super-majorities.[76][77][78]

In the election of 2008, the Democratic Party won all of New England's seats in the lower house of Congress, as Congressman Chris Shays of Connecticut's fourth Congressional District, New England's lone Republican in the House of Representatives, lost to Democrat Jim Himes.

Due to the liberal lean of the region, the state Republican parties and the elected Republican officials have been more politically and socially moderate than the national Republican Party, including Senators Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe of Maine and Scott Brown of Massachusetts as well as Governors Donald Carcieri (RI), Jodi Rell (CT) and Jim Douglas (VT). Republican Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire has been moderate-to-conservative, but this is reflective of New Hampshire being the most conservative state in the region, as New Hampshire, prior to the 2006 election, had the only Republican-controlled legislature in New England.

Collectively, New England has as many electoral votes (34) as Texas, though they are decided by each state. Comparatively, New England has better electoral representation—the population of New England is over 14 million while the population of Texas just under 24 million. In the 2000 presidential election, Democratic candidate Al Gore carried all of the New England states except for New Hampshire, and in 2004, John Kerry, a New Englander himself, won all six New England states.[79] In both the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections, every congressional district with the exception of New Hampshire's 1st district were won by Gore and Kerry respectively. During the 2008 Democratic primaries, Hillary Clinton won the three New England states containing Greater Boston (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire), while Barack Obama won the three that did not (Connecticut, Maine, and Vermont). In the 2008 presidential election, the Democratic candidate, Barack Obama, carried all six states by 9 percentage points or more.[80] He carried every county in New England except for Piscataquis County, Maine, which he lost by 4% to Senator John McCain (R-AZ).

The six states of New England voted for the Democratic Presidential nominee in the 1992, 1996, 2004, and 2008 elections, and every state but New Hampshire voted for Al Gore in the presidential election of 2000. It is one of the most liberal regions in the United States.[81][82][83] Currently all members of the United States House of Representatives from New England belong to or caucus with the Democratic Party. The only democratic socialist in the United States Congress is from New England. New England has the only current independent senators-Bernie Sanders representing Vermont and Joseph Lieberman representing Connecticut.

New Hampshire primary

Historically, the New Hampshire primary has been the first in a series of nationwide political party primary elections held in the United States every four years. Held in the state of New Hampshire, it usually marks the beginning of the U.S. presidential election process. Even though few delegates are chosen from New Hampshire, the primary has always been pivotal to both New England and American politics. Colleges such as the University of New Hampshire, Dartmouth College and Saint Anselm College have had presidential candidates visit their campuses and campaign to students. Local factories and diners are valuable photo-ops for candidates, who hope to use this quintessential New England image to their advantage by portraying themselves as sympathetic to blue collar workers. Media coverage of the primary enables candidates low on funds to "rally back"; an example of this was President Bill Clinton who referred to himself as "The Comeback Kid" following the 1992 primary. National media outlets have converged on small New Hampshire towns, such as during the 2007 and 2008 national presidential debates held at Saint Anselm College in the town of Goffstown.[84][85] Goffstown and other towns in New Hampshire have been experiencing this influx of national media since the 1950s.

Anti-nuclear movement

The national movement against nuclear power had its roots in New England in the 1970s. Its beginnings can be traced to 1974 when activist Sam Lovejoy toppled a weather tower at the site of the proposed Montague Nuclear Power Plant in Western Massachusetts.[86] The movement “reached critical mass’’ with the arrests at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant on May 1, 1977, when 1,414 anti-nuclear activists from the Clamshell Alliance were arrested at the Seabrook site. Harvey Wasserman, a Clamshell spokesman at Seabrook, and Frances Crowe of Northampton, an American Friends Service Committee member, played key roles in the movement.[86]

Government

In a study from 2005 to 2008, three New England states, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Hampshire were among the five states with the highest average property taxes, in percent of home value, in the country.[87]

Town meetings

A derivative of meetings held by church elders, town meetings were and are an integral part of governance of many New England towns. At such meetings, any citizen of the town may discuss issues with other members of the community and vote on them. This is the strongest example of direct democracy in the United States today, and the form of dialogue has been adopted under certain circumstances elsewhere, most strongly in the states closest to the region, such as New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Such a strong democratic tradition was even apparent in the early 19th century, when Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America that in:

New England, where education and liberty are the daughters of morality and religion, where society has acquired age and stability enough to enable it to form principles and hold fixed habits, the common people are accustomed to respect intellectual and moral superiority and to submit to it without complaint, although they set at naught all those privileges which wealth and birth have introduced among mankind. In New England, consequently, the democracy makes a more judicious choice than it does elsewhere.[88]

James Madison, a critic of town meetings, however, wrote in Federalist No. 55 that, regardless of the assembly, "passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob."[89] Today, the use and effectiveness of town meetings, as well as the possible application of the format to other regions and countries, is still discussed by scholars.[90]

Notable laws

The New England states abolished the death penalty for robbery and burglary in the 19th century, before much of the rest of the United States did. New Hampshire and Connecticut are the only New England states that allow capital punishment.[91] Although New Hampshire currently has one death row inmate, it has not held an execution since 1939. Connecticut held an execution in 2005, the first in New England since a previous Connecticut execution in 1960.[92]

Same-sex marriage is permitted in four New England states. In 2010, it was being debated in the Rhode Island legislature. In Maine, it was legalized by the legislature in 2009, but defeated in a referendum (53% voted to ban it versus 47% who voted to legalize it) later the same year.

Education

Colleges and universities

New England contains some of the oldest and most renowned institutions of higher learning in the United States. The first such institution, subsequently named Harvard College, was founded at Cambridge, Massachusetts, to train preachers, in 1636. Yale University was founded in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, in 1701, and awarded the nation's first doctoral (Ph.D.) degree in 1861. Yale moved to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1718 where it has remained to the present day. Brown University, the first college in the nation to accept students of all religious affiliations and seventh-oldest institution of higher learning, was founded in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1764. Dartmouth College was founded five years later in Hanover, New Hampshire, with the mission of educating the local American Indian population as well as English youth. The University of Vermont, the fifth oldest university in New England, was founded in 1791, the same year Vermont joined the Union.

In addition to four out of eight Ivy League schools, New England also contains the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Little Three, four of the original seven sisters, the bulk of institutions identified as the Little Ivies, and the Five Colleges consortium in western Massachusetts.

Private and independent secondary schools

At the pre-college level, New England is home to a number of American independent schools (also known as private schools). The concept of the elite "New England prep school" (preparatory school) and the "preppy" lifestyle is an iconic part of the region's image.[93] The region has several of the highest ranked high schools in the United States, such as the Maine School of Science and Mathematics located in Limestone, Maine.[94]

- See the list of private schools for each state:

Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont.

Public education

New England is home to some of the oldest public schools in the nation. Boston Latin School is the oldest public high school in America. Several signatories of the Declaration of Independence attended Boston Latin.[95] Portland High School in Portland, Maine is the second oldest operating high school in the United States.[96]

New England states fund their public schools with expenditures per student, and teacher salaries above the national median. As of 2005, the National Education Association ranked Connecticut with the highest-paid teachers in the country. Massachusetts and Rhode Island ranked eighth and ninth, respectively.

Three New England states, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont, have cooperated in developing a New England Common Assessment Program test under the No Child Left Behind guidelines. These states can compare the resultant scores with each other.

Maine's Maine Learning Technology Initiative program supplies all 7-8th graders and half of the states high schoolers with Apple MacBook laptops.

Academic journals and press

Several academic journals and publishing companies are published in the region, including The New England Journal of Medicine, Harvard University Press, and Yale University Press. Some of its institutions lead the open access alternative to conventional academic publication, including MIT, the University of Connecticut, and the University of Maine. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston publishes the New England Economic Review.[97]

Culture

New England has a history of shared heritage and culture primarily shaped by waves of immigration from Europe.[98] In contrast to other American regions, many of New England's earliest Puritan settlers came from eastern England, contributing to New England's distinctive accents, foods, customs, and social structures.[99] Within modern New England a cultural divide exists between urban New Englanders living along the densely-populated coastline and rural New Englanders in western Massachusetts, northwestern Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, where population density is low.[100]

Today, New England is the least religious part of the United States. In 2009, less than half of those polled in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont claimed that religion was an important part of their daily lives. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, also among the top ten least religious states, only 55 and 53 percent, respectively, of those polled claimed that it was.[101]

Cultural roots

The first European colonists of New England were focused on maritime affairs such as whaling and fishing, rather than more continental inclinations such as surplus farming. One of the older American regions, New England has developed a distinct cuisine, dialect, architecture, and government. New England cuisine is known for its emphasis on seafood and dairy; clam chowder, lobster, and other products of the sea are among some of the region's most popular foods.

Aside from the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, or "New Scotland", New England is the only North American region to inherit the name of a kingdom in the British Isles. New England has largely preserved its regional character, especially in its historic places. Today, the region is more ethnically diverse, having seen waves of immigration from Ireland, Quebec, Italy, Portugal, Asia, Latin America, Africa, other parts of the United States, and elsewhere. The enduring European influence can be seen in the region, from use of traffic rotaries to the bilingual French and English towns of northern Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire, as innocuous as the sprinkled use of British spelling, and as obvious as the region's heavy prevalence of English town and county names, and its unique, often non-rhotic coastal dialect reminiscent of southeastern England.

New England is the traditional center of ethnic English ancestry and culture in the United States. The only place in the U.S. outside New England with a significant majority English ethnicity is Utah-Eastern Idaho, the traditional core of the Jello Belt region, whose proportion of English Americans is actually higher today than that of New England, with Utah being the most English of U.S. states with 29.0% English ancestry, followed by New England states Maine with 21.5% and Vermont with 18.4%. Americans of English descent form a plurality of the white population in literally every southern state as well[102][103][104][105]. The population in Utah and Idaho is, in contrast, far more conservative than modern New England and is mainly LDS in religion, but its substratal cultural character is largely reminiscent of both early 19th-century New England and Victorian England (due to later direct handcart immigration).

Accents

There are several American English accents spoken in the region including New England English and Boston English.

The often-parodied Boston accent is native to the region. Many of its most stereotypical features (such as r-dropping and the so-called broad A) are believed to have originated in Boston from the influence of England's Received Pronunciation, which shares those features. While at one point Boston accents were most strongly associated with the so-called "Eastern Establishment" and Boston's upper class, today the accent is predominantly associated with blue-collar natives as exemplified by movies like Good Will Hunting and The Departed. The Boston accent and accents closely related to it cover eastern Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine.[106]

Social activities and music

In much of rural New England, particularly Maine, Acadian and Québécois culture are included in the region's music and dance. Contra dancing and country square dancing are popular throughout New England, usually backed by live Irish, Acadian, or other folk music.

Traditional knitting, quilting and rug hooking circles in rural New England have become less common; church, sports, and town government are more typical social activities. New Englanders of all ages also enjoy ice cream socials.[citation needed] These traditional gatherings are often hosted in individual homes or civic centers; larger groups regularly assemble at special-purpose ice cream parlors that dot the countryside. In fact, New England leads the country in ice cream consumption per capita.[107][108]

In the United States, candlepin bowling is essentially confined to New England, where it was invented in the 19th century.[109]

New England was for some time an important center of American classical music. The Second New England School was instrumental in reinvigorating the tradition in the United States. Prominent modernist composers also come from the region, including Charles Ives and John Adams. Boston is the site of the New England Conservatory and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In terms of rock music, the region has produced bands as different as Aerosmith, the Pixies, and Boston. Dick Dale, a Quincy, Massachusetts native, helped popularize surf rock. The region is also home to prominent hardcore and punk scenes.

Media

The leading national cable sports broadcaster ESPN is headquartered in Bristol, Connecticut. New England has several regional cable networks, including New England Cable News (NECN) and the New England Sports Network (NESN). New England Cable News is the largest regional news network in the United States, broadcasting to more than 3.2 million homes in all of the New England states. Its studios are located in Newton, Massachusetts, outside of Boston, it maintains bureaus in Manchester, New Hampshire; Hartford, Connecticut; Worcester, Massachusetts; Portland, Maine; and Burlington, Vermont.[110] In Connecticut, Litchfield, Fairfield, and New Haven counties also broadcast New York based news programs—this is due in part to the immense influence New York has on this region's economy and culture, and also to enable Connecticut broadcasters the ability to compete with overlapping media coverage from New York-area broadcasters.

NESN broadcasts the Boston Red Sox and Boston Bruins throughout the region, save for Fairfield County, Connecticut.[111] Most of Connecticut (save for Tolland and Windham counties in the state's northeast corner) and even southern Rhode Island gets YES network, the channel which the New York Yankees are broadcasted on. For the most part, the same areas also carry SNY, Sports New York, which is the channel New York Mets games are broadcasted on.

Comcast SportsNet New England carries the Boston Celtics, New England Revolution and Boston Cannons.

While most New England cities have daily newspapers, the Boston Globe and New York Times are distributed widely throughout the region. Major newspapers also include The Providence Journal, and Hartford Courant, the nation's oldest continuously published newspaper.[112]

Comedy

New Englanders are well represented in American comedy. Writers for The Simpsons often come by way of the Harvard Lampoon. Family Guy, an animated sitcom situated in Rhode Island, as well as American Dad, were created by Connecticut native and Rhode Island School of Design graduate Seth MacFarlane. A number of Saturday Night Live (SNL) cast members have origins in New England, from Adam Sandler to Amy Poehler, who also stars in the NBC television series Parks and Recreation. Former Daily Show show correspondents Rob Corddry and Steve Carell are from Massachusetts, with the latter also being involved in film and the American adaptation of The Office. Late night television hosts Jay Leno and Conan O'Brien have origins in the Boston area. Notable stand-up comedians, including Dane Cook, Sarah Silverman, Lisa Lampanelli, and Louis CK, are also from the region. Former SNL cast member Seth Meyers once attributed the region's imprint on American humor to its "sort of wry New England sense of pointing out anyone who's trying to make a big deal of himself," with the Boston Globe suggesting that irony and sarcasm, as well as Irish influences, are its trademarks.[113]

Literature

The literature of New England has had an enduring influence on American literature in general, with themes such as religion, race, the individual versus society, social repression, and nature, emblematic of the larger concerns of American letters.[114]

New England has been the birthplace of American authors and poets. Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston. Henry David Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, where he famously lived, for some time, by Walden Pond, on Emerson's land. Nathaniel Hawthorne, romantic era writer, was born in historical Salem; later, he would live in Concord at the same time as Emerson and Thoreau; all three writers have strong connections to The Old Manse, a home in the Emmerson family and a key center of the Transcendentalist movement. Emily Dickinson lived most of her life in Amherst, Massachusetts. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was from Portland, Maine. Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston. According to reports, the famed Mother Goose, the author of fairy tales and nursery rhymes was originally a person named Elizabeth Foster Goose or Mary Goose who lived in Boston. Poets James Russell Lowell, Amy Lowell, and Robert Lowell, a Confessionalist poet and teacher of Sylvia Plath, were all New England natives. Anne Sexton, also taught by Lowell, was born and died in Massachusetts. Much of the work of Nobel Prize laureate Eugene O'Neill is often associated with the city of New London, Connecticut where he spent many summers. The 14th U.S. Poet Laureate Donald Hall, a New Hampshire resident, continues the line of renowned New England poets. Noah Webster, the Father of American Scholarship and Education, was born in West Hartford, Connecticut. Pulitzer Prize winning poets Edwin Arlington Robinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Robert P. T. Coffin were born in Maine. Poets Stanley Kunitz and Elizabeth Bishop were both born in Worcester, Massachusetts. Pulitzer Prize winning poet Galway Kinnell was born in Providence, Rhode Island. Oliver La Farge was a New Englander of French and Narragansett descent, won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel, the predecessor to the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, in 1930 for his book Laughing Boy. John P. Marquand grew up in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Novelist Edwin O'Connor, who was also known as a radio personality and journalist, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his novel The Edge of Sadness. Pulitzer Prize winner John Cheever, a novelist and short story writer, was born in Quincy, Massachusetts set most of his fiction in old New England villages based on various South Shore towns around his birthcity. E. Annie Proulx was born in Norwich, Connecticut. David Lindsay-Abaire, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2007 for his play Rabbit Hole, was raised in Boston.

Ethan Frome, written in 1911 by Edith Wharton, is set in turn-of-the-century New England, in the fictitious town of Starkfield, Massachusetts. Like much literature of the region, it plays off themes of isolation and hopelessness. New England is also the setting for most of the gothic horror stories of H. P. Lovecraft, who lived his life in Providence, Rhode Island. Real New England towns such as Ipswich, Newburyport, Rowley, and Marblehead are given fictional names such as Dunwich, Arkham, Innsmouth, Kingsport, and Miskatonic and then featured quite often in his stories. Lovecraft had an immense appreciation for the New England area, and when he had to re-locate to New York City, he longed to return to his beloved native land.

The region has also drawn the attention of authors and poets from other parts of the United States. Mark Twain found Hartford to be the most beautiful city in the United States and made it his home, and wrote his masterpieces there. He lived directly next door to Harriett Beecher Stowe, a local whose most famous work is Uncle Tom's Cabin. John Updike, originally from Pennsylvania, eventually moved to Ipswich, Massachusetts, which served as the model for the fictional New England town of Tarbox in his 1968 novel Couples. Robert Frost was born in California, but moved to Massachusetts during his teen years and published his first poem in Lawrence; his frequent use of New England settings and themes ensured that he would be associated with the region. Arthur Miller, a New York City native, used New England as the setting for some of his works, most notably The Crucible. Herman Melville, originally from New York City, bought the house now known as Arrowhead in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and while he lived there he wrote his greatest novel Moby-Dick. Poet Maxine Kumin was born in Philadelphia, currently resides in Warner, New Hampshire. Pulitzer Prize winning poet Mary Oliver was born in Maple Heights, Ohio has lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts for the last forty years. Charles Simic who was born in Belgrade, Serbia (at that time Yugoslavia) grew up in Chicago and lives in Strafford, New Hampshire, on the shore of Bow Lake and is the professor emeritus of American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire. Pulitzer Prize winning novelist and short story writer Steven Millhauser, whose short story "Eisenheim the Illusionist" was adapted into the 2006 film The Illusionist, was born in New York City and raised in Connecticut.

More recently, Stephen King, born in Portland, Maine, has used the small towns of his home state as the setting for much of his horror fiction, with several of his stories taking place in or near the fictional town of Castle Rock. Just to the south, Exeter, New Hampshire was the birthplace of best-selling novelist John Irving and Dan Brown, author of The Da Vinci Code. Rick Moody has set many of his works in southern New England, focusing on wealthy families of suburban Connecticut's Gold Coast and their battles with addiction and anomie. Derek Walcott, a playwright and poet, who won the 1992 Nobel Prize for Literature, teaches poetry at Boston University. Pulitzer Prize winner Cormac McCarthy, whose novel No Country for Old Men was made into the Academy Award for Best Picture winning film in 2007, was born in Providence (although he moved to Tennessee when he was a boy). New York Times Bestselling author Dennis Lehane, another native of the Boston area, who was born in Dorchester, wrote the novels that were adapted into the films Mystic River, Gone Baby Gone and Shutter Island.

Largely on the strength of its local writers, Boston was for some years the center of the U.S. publishing industry, before being overtaken by New York in the middle of the nineteenth century. Boston remains the home of publishers Houghton Mifflin and Pearson Education, and was the longtime home of literary magazine The Atlantic Monthly. Merriam-Webster is based in Springfield, Massachusetts. Yankee, a magazine for New Englanders, is based in Dublin, New Hampshire.

Sports

Two popular American sports were invented in New England. Basketball was invented by James Naismith (a Canadian) in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891.[115] Volleyball was invented by William G. Morgan in Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1895.[116] Additionally, Walter Camp is credited with developing modern American football in New Haven, Connecticut in the 1870s and 1880s.[117]

New Hampshire Motor Speedway is an oval racetrack which has hosted several NASCAR and American Championship Car Racing races, whereas Lime Rock Park is a traditional road racing venue home of sports car races. Events at these venues have had the "New England" moniker, such as the NASCAR Cup Series New England 300, the NASCAR Nationwide Series New England 200, the IndyCar Series New England Indy 200 and the American Le Mans Series New England Grand Prix.

Professional and semi-professional sports teams

The major professional sports teams in New England are based in the Boston area: the Boston Red Sox, the New England Patriots (based in Foxborough, Massachusetts), the Boston Celtics, the Boston Bruins, the Boston Cannons and the New England Revolution (also based in Foxborough). Hartford had a professional hockey team, the Hartford Whalers from 1975 until they moved to North Carolina in 1997. Bridgeport had a professional lacrosse team the Bridgeport Barrage until they moved to Philadelphia and later ceased operation. A WNBA team, the Connecticut Sun, are based in southeastern Connecticut at the Mohegan Sun resort. Hartford currently has a professional football franchise, the Hartford Colonials, of the fledgling United Football League.

There are also minor league baseball and hockey teams based in larger cities such as the Pawtucket Red Sox (baseball), the Providence Bruins (hockey), the Worcester Tornadoes (baseball) and the Worcester Sharks (hockey), the Lowell Spinners (baseball) and the Lowell Devils (hockey), the Portland Sea Dogs (baseball) and the Portland Pirates (hockey), the Bridgeport Bluefish (baseball) and the Bridgeport Sound Tigers (hockey), the Connecticut Defenders (baseball), the New Britain Rock Cats (baseball), the Vermont Lake Monsters (baseball), the New Hampshire Fisher Cats (baseball) and the Manchester Monarchs (hockey), the Brockton Rox (baseball), the Hartford Wolf Pack (hockey), and the Springfield Falcons (hockey).

The NBA Development League fields two teams in New England: the Maine Red Claws, based in Portland, Maine, and the Springfield Armor in Springfield, Massachusetts. The Red Claws are affiliated with the Boston Celtics and the Charlotte Bobcats and the Armor are affiliated with the New Jersey Nets, New York Knicks, and Philadelphia 76ers. New England is also represented in the Premier Basketball League by the Vermont Frost Heaves of Barre, Vermont and, until recently, the Manchester Millrats from Manchester, New Hampshire.

Thanksgiving Day high school football rivalries date back to the 19th century, and the Harvard-Yale rivalry ("The Game") is the oldest active rivalry in college football. The Boston Marathon, run on Patriots' Day every year, is a New England cultural institution and the oldest annual marathon in the world. While the race offers far less prize money than many other marathons, and the Newton hills have helped ensure that no world record has been set on the course since 1947, the race's difficulty and long history make it one of the world's most prestigious marathons.[118]

Notable places

Historic

New England features many of the oldest cities and towns in the country. The following places are replete with historic buildings, parks, and streetscapes (following the coast from New Haven):

- Windsor, Vermont

- New Haven, Connecticut

- Hartford, Connecticut

- Springfield, Massachusetts

- Providence, Rhode Island

- Newport, Rhode Island

- Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Boston and its surrounding area

- Quincy, Massachusetts

- Salem, Massachusetts

- Gloucester, Massachusetts

- Newburyport, Massachusetts

- Portsmouth, New Hampshire

- Portland, Maine

- Eastport, Maine

- Cape Elizabeth, Maine

Recreational

The Appalachian Mountains run through northern New England which make for excellent skiing. Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine are home to various ski resorts.

Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts are popular tourist destinations for their small-town charm and beaches. All have restrictive zoning laws to prevent sprawl and overdevelopment.

Acadia National Park, off the coast of Maine, preserves most of Mount Desert Island and includes mountains, an ocean shoreline, woodlands, and lakes.

Additionally, the coastal New England states are home to many oceanfront beaches.

The financial magazine Money, in a 2006 survey entitled "Best Places to Live," ranked several New England towns and cities in the top one hundred. In Connecticut, Fairfield, part of the New York, New Jersey, Connecticut area, was ranked ninth, while Stamford was ranked forty-sixth. In Maine, Portland ranked eighty-ninth. In Massachusetts, Newton was ranked twenty-second. In New Hampshire, Nashua, a past number one, was ranked eighty-seventh. In Rhode Island, Cranston was ranked seventy-eighth, while Warwick was ranked eighty-third.[120]

Infrastructure

Six mainline Interstate highways cross New England, with at least one serving each state and its respective capital city:

![]() Interstate 84 enters New England at Danbury, Connecticut, and crosses that state to the northeast; connecting the city of Waterbury and the state capital of Hartford before terminating at a junction with Interstate 90 in Massachusetts.

Interstate 84 enters New England at Danbury, Connecticut, and crosses that state to the northeast; connecting the city of Waterbury and the state capital of Hartford before terminating at a junction with Interstate 90 in Massachusetts.

![]() Interstate 90, also signed east-west, carries the Massachusetts Turnpike designation as it crosses the state. I-90 enters Massachusetts at West Stockbridge and travels eastward to its terminus in Boston; connecting the cities of Springfield and Worcester and intersecting many of New England's major north-south routes.

Interstate 90, also signed east-west, carries the Massachusetts Turnpike designation as it crosses the state. I-90 enters Massachusetts at West Stockbridge and travels eastward to its terminus in Boston; connecting the cities of Springfield and Worcester and intersecting many of New England's major north-south routes.

![]() Interstate 89, signed north-south, begins at a junction with Interstate 93 just south of Concord, New Hampshire. I-89 travels to the northwest towards its terminus at the Canadian border, connecting Lebanon, the state capital of Montpelier, and Burlington (Vermont's largest city) along the way.

Interstate 89, signed north-south, begins at a junction with Interstate 93 just south of Concord, New Hampshire. I-89 travels to the northwest towards its terminus at the Canadian border, connecting Lebanon, the state capital of Montpelier, and Burlington (Vermont's largest city) along the way.

![]() Interstate 91 begins in New Haven, Connecticut at a junction with Interstate 95, running north from there throughout Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Vermont until it reaches the Canadian border. I-91 parallels U.S. Route 5 for its entire length, and much of the route also follows the Connecticut River, linking many of the major cities and towns along the river including Hartford, Springfield, and Brattleboro. I-91 is the only Interstate route within New England that intersects all five of the others.

Interstate 91 begins in New Haven, Connecticut at a junction with Interstate 95, running north from there throughout Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Vermont until it reaches the Canadian border. I-91 parallels U.S. Route 5 for its entire length, and much of the route also follows the Connecticut River, linking many of the major cities and towns along the river including Hartford, Springfield, and Brattleboro. I-91 is the only Interstate route within New England that intersects all five of the others.

![]() Interstate 93 begins in Canton, Massachusetts at a junction with Interstate 95, running northeastward from there through the city of Boston. I-93 travels north from Boston and into New Hampshire, where it serves as the main Interstate highway through that state and links many of the larger cities and towns (including the capital, Concord, and Manchester). I-93 eventually enters Vermont and reaches its northern terminus at a junction with Interstate 91.

Interstate 93 begins in Canton, Massachusetts at a junction with Interstate 95, running northeastward from there through the city of Boston. I-93 travels north from Boston and into New Hampshire, where it serves as the main Interstate highway through that state and links many of the larger cities and towns (including the capital, Concord, and Manchester). I-93 eventually enters Vermont and reaches its northern terminus at a junction with Interstate 91.

![]() Interstate 95, which runs along the East Coast, enters New England at Greenwich, Connecticut, and runs in a general northeastern direction along the Atlantic Ocean, eventually heading through Maine's sparsely-populated north country to its northern terminus at the Canadian border. I-95 serves many of the coastline's cities, including the state capitals of Providence and Augusta, while serving as a partial beltway around Boston. I-95 travels through every New England state except Vermont, and is the only two-digit Interstate highway to enter the states of Rhode Island and Maine.

Interstate 95, which runs along the East Coast, enters New England at Greenwich, Connecticut, and runs in a general northeastern direction along the Atlantic Ocean, eventually heading through Maine's sparsely-populated north country to its northern terminus at the Canadian border. I-95 serves many of the coastline's cities, including the state capitals of Providence and Augusta, while serving as a partial beltway around Boston. I-95 travels through every New England state except Vermont, and is the only two-digit Interstate highway to enter the states of Rhode Island and Maine.

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) provides rail and subway service within the Boston metropolitan area, bus service in Greater Boston, and commuter rail service throughout Eastern Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island. The New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Metro-North Commuter Railroad provides rail, serving many commuters in Southwestern Connecticut, while the Connecticut Department of Transportation operates the Shore Line East commuter rail service along the Connecticut coastline east of New Haven.

Amtrak provides interstate rail service throughout New England. Boston is the northern terminus of the Northeast Corridor line. The Vermonter connects Vermont to Massachusetts and Connecticut, while the Downeaster links Maine to Boston.

See also

- Extreme points of New England

- Historic New England

- List of amusement parks in New England

- List of beaches in New England

| class="col-break " |

| class="col-break " |

Notes

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ "News Release: GDP by State". Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Edward O’Connor. "Alternate flags for New England". E. O’Connor. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ a b David B. Martucci. "The New England Flag". D. Martucci. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ^ 'Historical Flags of Our Ancestors'. "Flags of the Early North American Colonies and Explorers".

- ^ "New England flags (U.S.)". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ a b c d Bain, Angela Goebel; Manring, Lynne; and Mathews, Barbara. Native Peoples in New England. Retrieved July 21, 2010, from Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

- ^ a b Paullin, Charles O.; Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States.; Edited by John K. Wright; New York, New York and Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington and American Geographical Society of New York, 1932:Plate 42. ; Excellent section on International and interstate boundary disputes.

- ^ a b Swindler, William F.., ed. Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. 10 Volumes; Dobbs Ferry, New York; Oceana Publications, 1973-1979; Vol. 10; Pps. 17-23; The most complete and up-to-date compilation for the states.

- ^ a b Van Zandt, Franklin K.; Boundaries of the United States and the Several States; Geological Survey Professional Paper 909. Washington, D.C.; Government Printing Office; 1976. The standard compilation for its subject.; Page 92.

- ^ "In addition to claiming land for England and bringing the faith of the Church of England to the native peoples, each of the Virginia Companies was also enjoined both by the crown and its members to make a tidy profit by whatever means it found expedient." NPS.gov

- ^ Woodard, Colin. The Lobster Coast. New York. Viking/Penguin, ISBN 0-670-03324-3, 2004, pp. 78-80

- ^ "The Virginia Company: Lecture Transcript One". Annenberg Media. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ "New England". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ State Street Trust Company. Towns of New England and Old England. Boston, 1921.

- ^ Swindler, William F., ed; Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. 10 Volumes; Dobbs Ferry, New York; Oceana Publications, 1973-1979. Volume 5: Pages 16-26.

- ^ "...joint stock company organized in 1620 by a charter from the British crown with authority to colonize and govern the area now known as New England." New England, Council for. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 13, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service: Britannica.com

- ^ Charles French and Scott Mitchell. American Guide To U.S. Coins: The Most Up-to-Date Coin Prices Available. Available Coin-collecting.info . Retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 112. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b O’Callaghan, E. B., ed; Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Volumes 1 - 11.;Albany, New York; 1853-1887 ; Volume 3: Page 537

- ^ Craven, Wesley Frank; Colonies in Transition, 1660 – 1713.;New York, New York: Harper and Row, 1968. Page 224.

- ^ Morris, Gerald E., and Kelly, Richard D., eds; Maine Bicentennial Atlas: An Historical Survey. Plate 11. Portland, Maine; Portland Historical Society; 1976.

- ^ "Slavery in New Hempshire". Slavenorth.com. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ James Schouler, History of the United States vol 1 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. 1891; copyright expired).

- ^ "New England". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ a b "New England," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived 2006-10-13

- ^ "Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor - History & Culture (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. 2009-06-11. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ Bagnall, William R. The Textile Industries of the United States: Including Sketches and Notices of Cotton, Woolen, Silk, and Linen Manufacturers in the Colonial Period. Vol. I. Pg 97. The Riverside Press, 1893.

- ^ Dublin, Thomas. "Lowell Millhands." Transforming Women's Work. Ithaca: Cornell UP. 77-118.

- ^ "The Story of the World Record Wind". Mount Washington Observatory. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ a b "city-data.com".

- ^ "New England's Fall Foliage". Discover New England. Archived from the original on 2007-08-16. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ New England Climate Initiative. Available at Unh.edu . Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ^ Adams, Glenn (February 11, 2009). Maine ties Vt. for record low temperature. Burlington Free Press.

- ^ Steinbicker, Earl (2000). 50 one day adventures—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire. Hastings House/Daytrips

Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0803820089.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 24 (help) - ^ [1], Encountering American Fault Lines: Race, Class, and the Dominican Experience in Providence by Jose Itzigsohn.(2009)