Phenoperidine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Excretion | Bile and Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.391 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

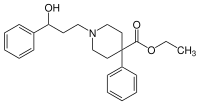

| Formula | C23H29NO3 |

| Molar mass | 367.481 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Phenoperidine was discovered by Janssen Pharmaceutica 1960.[1] Marketed as its hydrochloride as Operidine or Lealgin, is an opioid used as a general anesthetic. It is a derivative of isonipecotic acid, like pethidine, and is metabolized in part to norpethidine. It is 20-200 times as potent as pethidine as an analgesic. The greatly increased potency essentially eliminates the toxic effects of norpethidine accumulation which are seen when pethidine is administered in high doses or for long periods of time.

In humans 1 milligram is equipotent with 10 mg morphine. It has less effect on the circulatory system and is less hypnotic than morphine, but it has about the same emetic effect. The nausea can be prevented by giving droperidol or haloperidol. After an intravenous dose the analgesia sets in after 3–5 minutes.[2]

Phenoperidine shares structural similarities with both pethidine and haloperidol (and related butyrophenone antipsychotics, e.g. droperidol). While not commonly used today in clinical practice, it is of historical interest as a precursor in the development of some of the most widely used neuroleptic drugs on the market today.

Introduction

Phenoperidine behaves in a similar way to morphine and is classified as a narcotic analgesic. It can be used as a neuroleptanalgesia, with droperidol for instance. [3]

History and Synthesis

Phenoperidine was developed in 1957 through modifications of an existing drug. To begin, two key analgesic compounds, pethidine (meperidine) and methadone, were both synthesized by Otto Eisleb. Methadone preluded the synthesis of pethidine in 1939. Analogues of both of these drugs were investigated during World War II and years after, with the primary focus being on methadone. Janssen Pharmaceutica located in Belgium synthesized dextromoramide from methadone in 1954 and afterwards the company pursued pethidine analogues due in part to the less complicated chemistry of the compound. In doing so, the methyl group attached to the pethidine nitrogen was replaced by a propiophenone group. With this modification, phenoperidine was synthesized in 1957. Phenoperidine was determined to have decreased stability and enhanced lipophilicity compared to pethidine. Soon after, studies in mice showed that phenoperidine was over 100 times more potent than pethidine. [4] At the time, phenoperidine was the “most potent opioid in the world” and was used extensively in the European market but not in the United States. Through further advances, Janssen Pharmaceutica created fentanyl in 1960, which proved to be ten times more potent than phenoperidine. [5] Interestingly, additional modifications led to the discovery of one of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines, claimed to be “one of the greatest advances of the 20th century psychiatry”—haloperidol. [6]

Opioid Market

In 2011, the total global morphine equivalent opioid consumption per person was 61.66 mg/capita. While in the Americas, the total morphine equivalent opioid consumption was roughly 750 mg/capita. [7]

References

- ^ BE Patent 576331

- ^ Farmacevtiska specialiteter i Sverige (FASS) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Linfo. 1983. ISBN 91-85314-44-7.

- ^ "Phenoperidine". University of Rochester Medical Center. University of Rochester Medical Center. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Lopez-Munoz, Francisco; Alamo, Cecilio (2009). "The Consolidation of Neuroleptic Therapy: Janssen, the Discovery of Haloperidol and Its Introduction into Clinical Practice". Brain Research Bulletin. 79: 130-141.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Stanley, Theodore (2014). "The Fentanyl Story". The Journal of Pain. 15 (12): 1215-1226.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lopez-Munoz, Francisco; Alamo, Cecilio (2009). "The Consolidation of Neuroleptic Therapy: Janssen, the Discovery of Haloperidol and Its Introduction into Clinical Practice". Brain Research Bulletin. 79: 130-141.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Regional". Pain & Policy Studies Group. Pain & Policy Studies, University of Wisconsin—Madison. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

External links

- Kintz, P.; Godelar, B.; Mangin, P.; Lugnier, A.; Chaumont, A. (1989). "Simultaneous Determination of Pethidine (Meperidine), Phenoperidine, and Norpethidine (Normeperidine), their Common Metabolite, by Gas Chromatography with Selective Nitrogen Detection". Forensic Science International. 43 (3): 267–273. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(89)90154-0. PMID 2613140.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Claris, O.; Bertrix, L. (1988). "Phenoperidine: Pharmacology and Use in Pediatric Resuscitation". Pédiatrie (in French). 43 (6): 509–513. PMID 3186421.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Antipsychotics - Reference pathway". Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Kanehisa Laboratories, Kyoto University, University of Tokyo. Retrieved 2007-01-16.