Salbutamol

| |

(S)-Salbutamol | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, inhalational, IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3.8 - 6 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.038.552 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

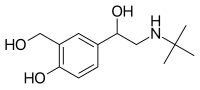

| Formula | C13H21NO3 |

| Molar mass | 239.311 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Salbutamol (INN) or albuterol (USAN) is a short-acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonist used for the relief of bronchospasm in conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD).[3] It is marketed as Ventolin among other brand names.

Salbutamol was the first selective β2-receptor agonist to be marketed in 1968. It was first sold by Allen & Hanburys (UK) under the brand name Ventolin, and has been used for the treatment of asthma ever since.[4] It was approved for use in the US by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 1982.[5]

The drug is usually manufactured and distributed as salbutamol sulfate.

Salbutamol is mostly taken by the inhaled route for direct effect on bronchial smooth muscle. This is usually achieved through a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), nebulizer, or other proprietary delivery devices. In these forms of delivery, the maximal effect of salbutamol can take place within five to 20 minutes of dosing, though some relief is immediately seen. Mean duration of effect is roughly 2 hours.[6] It can also be given intravenously.[7] Salbutamol is also available in oral form (tablets, syrup).

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[8] Compliance with the Montreal Protocol, which requires the banning of the use of ozone-layer depleting CFCs, has caused the price of inhalers, however, to increase as much as ten-fold as generics were forced off the market from 2009 to 2013 by new patents obtained by pharmaceutical companies for non-CFC delivery systems.

Medical uses

Salbutamol is typically used to treat bronchospasm (due to any cause, allergen asthma or exercise-induced), as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[9] Emergency medical practice commonly treats people presenting with asthma who report taking their salbutamol inhaler as prescribed with salbutamol. In general, people tolerate large doses well.

Other uses include in cystic fibrosis and subtypes of congenital myasthenic syndromes associated to mutations in Dok-7.[citation needed]

As a β2-agonist, salbutamol also finds use in obstetrics. Intravenous salbutamol can be used as a tocolytic to relax the uterine smooth muscle to delay premature labor. While preferred over agents such as atosiban and ritodrine, its role has largely been replaced by the calcium-channel blocker nifedipine, which is more effective, better tolerated and orally administered.[10]

Salbutamol is used to treat acute hyperkalemia as it stimulates potassium to flow in cells thus lowering the level in the blood.[11][12]

Salbutamol has also been trialed in spinal muscular atrophy where it appears to show modest benefits. The drug is speculated to modulate the alternative splicing of the SMN2 gene, increasing the amount of the SMN protein whose deficiency is regarded as the root cause of the disease.[13][14]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects are fine tremor, anxiety, headache, muscle cramps, dry mouth, and palpitation.[15] Other symptoms may include tachycardia, arrhythmia, flushing, myocardial ischemia (rare), and disturbances of sleep and behaviour.[15] Rarely occurring, but of importance, are allergic reactions of paradoxical bronchospasm, urticaria, angioedema, hypotension, and collapse. High doses or prolonged use may cause hypokalaemia, which is of concern especially in patients with renal failure and those on certain diuretics and xanthine derivatives.[15]

Chemistry

Structure-activity relationships

The tertiary butyl group in salbutamol (or albuterol) makes it more selective for β₂-receptors. The drug is sold as a racemic mixture mainly because the (S)-enantiomer blocks metabolism pathways while the (R)-enantiomer shows activity.[16]

Society and culture

Bodybuilding

Salbutamol has been shown to improve muscle weight in rats [17] and anecdotal reports hypothesis that it might be an alternative to clenbuterol for purposes of fat burning and muscle gain, with multiple studies supporting this claim.[18][19][20][21][22] Abuse of the drug may be confirmed by detection of its presence in plasma or urine, typically exceeding 1000 µg/L.[23]

Doping

Clinical studies show no compelling evidence that salbutamol and other β2-agonists can increase performance in healthy athletes.[24] In spite of this, salbutamol required "a declaration of Use in accordance with the International Standard for Therapeutic Use Exemptions" under the 2010 WADA prohibited list. This requirement was relaxed when the 2011 list was published to permit the use of "salbutamol (maximum 1600 micrograms over 24 hours) and salmeterol when taken by inhalation in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommended therapeutic regimen." [25][26]

According to two small and limited studies, performed on eight and 16 subjects, respectively, salbutamol increases the performance even for a person without asthma.[27][28][29]

Another study contradicts the above findings, however. The double blind, randomised test conducted on 12 non-asthmatic athletes concluded that salbutamol had a negligible effect on endurance performance. Nevertheless, the study also showed that the drug's bronchodilating effect may have improved respiratory adaptation at the beginning of exercise.[30]

Detection of use

Salbutamol may be quantified in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in a forensic investigation. Urinary salbutamol concentrations are frequently measured in competitive sports programs, for which a level in excess of 1000 μg/L is considered to represent abuse. The window of detection for urine testing is on the order of just 24 hours, given the relatively short elimination half-life of the drug[23][31][32] (estimated at between 5 and 6 hours following oral administration of 4 mg[33]).

Brand names

It is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline as Ventolin, Ventoline, Ventilan, Aerolin, or Ventorlin, depending on the market; by Cipla as Asthalin and Asthavent; by Schering-Plough as Proventil, by Teva as ProAir and Novo-Salbutamol HFA (Canada), Salamol, or Airomir, by Beximco (Bangladesh) as AZMASOL by Ad-din Pharma as Ventosol and by Alphapharm as Asmol.

See also

References

- ^ Health Canada

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ "Ventolin". HealthExpress. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ "Ventolin remains a breath of fresh air for asthma sufferers, after 40 years" (PDF). The Pharmaceutical Journal. 279 (7473): 404–405.

- ^ MedicineNet, Inc. http://www.medicinenet.com/albuterol/article.htm

- ^ Measured by a 15% increase from baseline in FEV1. "Albuterol Sulfate", Rx List: The Internet Drug Index, 6/12/2008, retrieved 2014-07-13

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Ventolin Solution for IV Infusion". Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Albuterol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Rossi, S (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook. AMH. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003235.pub2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003235.pub2instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/emj.17.3.188, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/emj.17.3.188instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22031667, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22031667instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s11910-011-0240-9, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s11910-011-0240-9instead. - ^ a b c "3.1.1.1 Selective beta2 agonists – side effects". British National Formulary (57 ed.). London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and Royal Pharmaceutical Society Publishing. March 2008. ISBN 0-85369-778-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mehta, Akul. "Medicinal Chemistry of the Peripheral Nervous System – Adrenergics and Cholinergics their Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Structure Activity Relationships". Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ Carter WJ, Lynch ME (September 1994). "Comparison of the effects of salbutamol and clenbuterol on skeletal muscle mass and carcass composition in senescent rats". Metab. Clin. Exp. 43 (9): 1119–25. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(94)90054-X. PMID 7916118.

- ^ Caruso, JF; Signorile, JF; Perry, AC; Leblanc, B; Williams, R; Clark, M; Bamman, MM (Nov 1995). "The effects of albuterol and isokinetic exercise on the quadriceps muscle group". Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 27 (11): 1471–6. doi:10.1249/00005768-199511000-00002. PMID 8587482.

- ^ Caruso, J. (20 January 2005). "Albuterol aids resistance exercise in reducing unloading-induced ankle extensor strength losses". Journal of Applied Physiology. 98 (5): 1705–1711. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01015.2004.

- ^ Caruso, John F. (2005). "Oral Albuterol Dosing During the Latter Stages of a Resistance Exercise Program". The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 19 (1): 102. doi:10.1519/R-14793.1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Caruso, JF; Hamill, JL; Yamauchi, M; Mercado, DR; Cook, TD; Keller, CP; Montgomery, AG; Elias, J (Jun 2004). "Albuterol helps resistance exercise attenuate unloading-induced knee extensor losses". Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 75 (6): 505–11. PMID 15198276.

- ^ Caruso, JF (Feb 2005). "Oral albuterol dosing during the latter stages of a resistance exercise program". Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 19 (1): 102–7. doi:10.1519/00124278-200502000-00018. PMID 15705021.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 33–35. ISBN 0-9626523-6-9.

- ^ Davis, E; Loiacono, R; Summers, R J (2008). "The rush to adrenaline: drugs in sport acting on the β-adrenergic system". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 584–97. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.164. PMC 2439523. PMID 18500380.

- ^ "THE 2010 PROHIBITED LIST INTERNATIONAL STANDARD" (PDF). WADA. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ "THE 2011 PROHIBITED LIST INTERNATIONAL STANDARD" (PDF). WADA. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ Collomp, K; Candau, R; Lasne, F; Labsy, Z; Préfaut, C; De Ceaurriz, J (2000). "Effects of short-term oral salbutamol administration on exercise endurance and metabolism". Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985). 89 (2): 430–6. PMID 10926623.

- ^ "Salbutamol: Ergogenic effects of salbutamol". Retrieved 2010-10-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Van Baak, MA; De Hon, OM; Hartgens, F; Kuipers, H (2004). "Inhaled salbutamol and endurance cycling performance in non-asthmatic athletes". International journal of sports medicine. 25 (7): 533–8. doi:10.1055/s-2004-815716. PMID 15459835.

- ^ Goubault, C; Perault, MC; Leleu, E; Bouquet, S; Legros, P; Vandel, B; Denjean, A (2001). "Effects of inhaled salbutamol in exercising non-asthmatic athletes". Thorax. 56 (9): 675–679. doi:10.1136/thorax.56.9.675. PMC 1746141. PMID 11514686.

- ^ Berges, Rosa; S; V; F; M; F; M; D (2000). "Discrimination of Prohibited Oral Use of Salbutamol from Authorized Inhaled Asthma Treatment". Clinical Chemistry. 46 (9): 1365–75. PMID 10973867.

- ^ Schweizer, C; Saugy, M; Kamber, M (2004). "Doping test reveals high concentrations of salbutamol in a Swiss track and field athlete". Clin. J. Sport Med. 14 (5): 312–315. doi:10.1097/00042752-200409000-00018. PMID 15377972.

{{cite journal}}:|first4=missing|last4=(help) - ^ "Albuterol Sulfate", Rx List: The Internet Drug Index, 6/12/2008, retrieved 2014-07-13

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Additional notes

- Moore, NG; Pegg, GG; Sillence, MN (September 1994). "Anabolic effects of the beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist salmeterol are dependent on route of administration". Am. J. Physiol. 267 (3 Pt 1): E475–84. PMID 7943228.

- Schiffelers, SL; Saris, WH; Boomsma, F; Van Baak, MA (May 2001). "beta(1)- and beta(2)-Adrenoceptor-mediated thermogenesis and lipid utilization in obese and lean men". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86 (5): 2191–9. doi:10.1210/jc.86.5.2191. PMID 11344226.

- Van Baak, MA; Mayer, LH; Kempinski, RE; Hartgens, F (July 2000). "Effect of salbutamol on muscle strength and endurance performance in nonasthmatic men". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 32 (7): 1300–6. doi:10.1097/00005768-200007000-00018. PMID 10912897.

- Caruso, JF; Hamill, JL; De Garmo, N (February 2005). "Oral albuterol dosing during the latter stages of a resistance exercise program". J Strength Cond Res. 19 (1): 102–7. doi:10.1519/00124278-200502000-00018. PMID 15705021.

- Caruso JF, Signorile JF, Perry AC; et al. (November 1995). "The effects of albuterol and isokinetic exercise on the quadriceps muscle group". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 27 (11): 1471–6. doi:10.1249/00005768-199511000-00002. PMID 8587482.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martineau, L; Horan, MA; Rothwell, NJ; Little, RA (November 1992). "Salbutamol, a beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist, increases skeletal muscle strength in young men". Clin. Sci. 83 (5): 615–21. PMID 1335400.S

- Desaphy, JF; Pierno, S; De Luca, A; Didonna, P; Camerino, DC (March 2003). "Different ability of clenbuterol and salbutamol to block sodium channels predicts their therapeutic use in muscle excitability disorders". Mol. Pharmacol. 63 (3): 659–70. doi:10.1124/mol.63.3.659. PMID 12606775.

- Maki, KC; Skorodin, MS; Jessen, JH; Laghi, F (June 1996). "Effects of oral albuterol on serum lipids and carbohydrate metabolism in healthy men". Metab. Clin. Exp. 45 (6): 712–7. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90136-5. PMID 8637445.