Petro Poroshenko

Petro Poroshenko Петро Порошенко | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th President of Ukraine | |

| Assumed office 7 June 2014 | |

| Prime Minister | Arseniy Yatsenyuk |

| Preceded by | Oleksandr Turchynov (Acting) |

| 2nd Minister of Trade and Economic Development | |

| In office 23 March 2012 – 24 December 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Mykola Azarov |

| Preceded by | Andriy Klyuyev |

| Succeeded by | Ihor Prasolov |

| 9th Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 9 October 2009 – 11 March 2010 | |

| Prime Minister | Yulia Tymoshenko Oleksandr Turchynov (Acting) |

| Preceded by | Volodymyr Khandohiy |

| Succeeded by | Kostyantyn Gryshchenko |

| 4th Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council | |

| In office 8 February 2005 – 8 September 2005 | |

| President | Viktor Yushchenko |

| Preceded by | Volodymyr Radchenko |

| Succeeded by | Anatoliy Kinakh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Petro Oleksiyovych Poroshenko 26 September 1965 Bolhrad, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party (1990–2001) Independent (2001–2002; 2012–2014) Our Ukraine Bloc (2002–2012) Petro Poroshenko Bloc (2014–present) |

| Spouse | Maryna Perevedentseva |

| Children | Olexiy Yevheniya Oleksandra Mykhaylo |

| Residence(s) | Mariyinsky Palace (official) Kozyn, Kiev Oblast (private) |

| Alma mater | Taras Shevchenko National University |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Soviet Army |

| Years of service | 1984–1986 |

Petro Poroshenko | |

|---|---|

| Deputy | People's Deputy of Ukraine |

Petro Oleksiyovych Poroshenko (Template:Lang-uk, Ukrainian pronunciation: [pɛˈtrɔ oɫɛˈksijovɪt͡ʃ poroˈʃɛnko]; born 26 September 1965) is the fifth and current President of Ukraine, in office since 2014.[8] He served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2009 to 2010, and as the Minister of Trade and Economic Development in 2012. From 2007 until 2012, Poroshenko headed the Council of Ukraine's National Bank.

Outside government, Poroshenko has been a prominent oligarch[9] with a lucrative career in acquiring and building assets. His most recognized ownerships are Roshen, the large-scale confectionery company which has earned him the nickname of 'Chocolate King',[9] and a TV channel 5 kanal, an all-news national TV broadcaster. Due to the scale of his business holdings in manufacturing, agriculture and financial industry, his political influence that included several stints at government prior to his presidency, and ownership of an influential mass-media outlet. Poroshenko has long been considered one of the prominent Ukrainian oligarchs even though not the most influential among them.

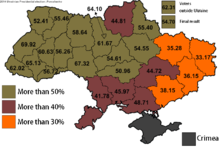

He was elected president on 25 May 2014, capturing more than 54% of the vote in the first round, thereby winning outright and avoiding a run-off.[10][11][12][13][14]

Early life and education

Poroshenko was born in the city of Bolhrad, in Odessa Oblast, on 26 September 1965.[15][16] He also spent his childhood and youth in Bendery (Moldavian SSR, now officially Moldova but under de facto control of the unrecognised breakaway state Transnistria).[17] where his father Oleksiy was heading a machine building plant.

In his youth, Poroshenko practiced judo and sambo, and was Candidate for Master of Sport of the USSR.[18] Despite good grades he was not awarded the normal gold medal at graduation, and on his report card he was given a "C" for his behavior.[2] After getting into a fight with four Soviet Army cadets at the military commissariat, he was sent to army service in the distant Kazakh SSR.[2]

In 1989, Poroshenko graduated, having started studying in 1982, with a degree in economics from the international relations and law department (subsequently the Institute of International Relations) at the Kiev State University.[19] At this university he was friends with Mikheil Saakashvili who he in May 2015 would appoint as Governor of Odessa Oblast (region) and who is a former President of Georgia .[20]

In 1984 Poroshenko married a medical student, Maryna Perevedentseva (born 1962).[18] Their first son, Oleksiy, was born in 1985 (his three other children were born in 2000 and 2001).[18]

From 1989 to 1992 Poroshenko was an assistant at the university's international economic relations department.[18] While still a student, he founded a legal advisory firm mediating the negotiation of contracts in foreign trade, and then he undertook the negotiations himself, starting to supply cocoa beans to the Soviet chocolate industry in 1991.[18] At the same time, he was deputy director of the 'Republic' Union of Small Businesses and Entrepreneurs, and the CEO "Exchange House Ukraine".[18]

Poroshenko's brother, Mykhailo, older by eight years, died in a 1997 car accident under mysterious circumstances.[21]

Business career

In 1993, Poroshenko, together with his father Oleksiy and colleagues from the Road Traffic Institute in Kiev, created the UkrPromInvest Ukrainian Industry and Investment Company, which specialised in confectionery (and later other agricultural processing industries) and the automotive industry.[18] Poroshenko was director-general of the company from its founding until 1998, when in connection with his entry into parliament he handed the title over to his father, while retaining the title of honorary president.[18]

Between 1996 and 1998, UkrPromInvest acquired control over several state-owned confectionery enterprises which were combined into the Roshen group in 1996, creating the largest confectionery manufacturing operation in Ukraine.[18] His business success in the confectionery industry earned him the nickname "Chocolate King".[22] Poroshenko's business empire also includes several car and bus plants, Leninska Kuznya shipyard, the 5 Kanal television channel,[23] as well as other businesses in Ukraine.

Although not the most prominent in the list of his business holdings, the assets that drew much recent media attention, and often controversy, are the confectionery factory in Lipetsk, Russia, that became controversial due to the 2014–15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, the Sevastopol Marine Plant (Sevmorzavod) that has been confiscated after the 2014 Russian forcible annexation of Crimea and the media outlet 5 kanal, particularly because of Poroshenko's repeated refusal to sell an influential media asset following his accession to presidency.

Billionaires lists rankings

In March 2012, Forbes placed him on the Forbes list of billionaires at 1,153rd place, with $1 billion.[24] As of May 2015, Poroshenko's net worth was about $720 million (Bloomberg estimate), losing 25 percent profit ever since Russia's ban of Roshen products and the state of the Ukrainian economy.[25]

According to the annual ranking of the richest people in Ukraine[26] published by the Ukrainian journal Novoye Vremya and conducted jointly with Dragon Capital, a leading investment company in Ukraine, published in October 2015, president Poroshenko was found the only one from the top ten of the list whose asset value grew since the previous ranking. The estimate of his assets was set at 979 million US dollars, a 20% growth, and his ranking changed from 9-th to 6-th wealthiest person in Ukraine. The article noted that Poroshenko remained one of the only two European leaders who owned a business empire of such scale, with Silvio Berlusconi being the other one.

Associated businesses

A number of businesses were once part of the Ukrprominvest which Poroshenko headed in 1993–1998. The investment group was dissolved in April 2012.[27] Poroshenko has stated that upon beginning his political activity he passed on his holdings to a trust fund.[18]

- Bogdan group (Poroshenko sold his share in connection with the collapse of its production after the 2008 economic crisis in 2009)[18]

- Roshen group

- 5 Kanal television channel

- Leninska Kuznya shipyard[18]

Early political career

Poroshenko first won a seat in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian Parliament) in 1998 for the 12th single-mandate constituency. He was initially a member of the United Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (SDPU), the party loyal to president Leonid Kuchma at the time.[18] Poroshenko left SDPU(o) in 2000 to create an independent left-of-center faction, naming it Solidarity.[18][28] In 2001 Poroshenko was instrumental in creating the Party of Regions, also loyal to Kuchma, but Solidarity never completed the merger.[29]

Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council

In December 2001 Poroshenko broke ranks with Kuchma supporters to become campaign chief of Viktor Yushchenko's Our Ukraine Bloc opposition faction. After parliamentary elections in March 2002 in which Our Ukraine won the biggest share of the popular vote and Poroshenko won a seat in parliament,[18][30] Poroshenko served as head of the parliamentary budget committee, where he was accused of "misplacing 47 million hryvnias" (USD$8.9 million).[31] As a consequence of Poroshenko's Our Ukraine Bloc membership tax inspectors launched an attack on his business.[18] Despite great difficulties, UkrPromInvest managed to survive until Yushchenko became President of Ukraine in 2005.[18]

Poroshenko was considered a close confidant of Yushchenko, who is godfather to Poroshenko's daughters. Poroshenko was likely to have been the wealthiest oligarch[9] among Yushchenko supporters, and was often named as one of the main financial backers of Our Ukraine and the Orange Revolution.[32] After Yushchenko won the presidential elections in 2004, Poroshenko was appointed Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council.[18][19]

In September 2005, highly publicized mutual allegations of corruption erupted between Poroshenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko involving the privatizations of state-owned firms.[1] Poroshenko, for example, was accused of defending the interests of Viktor Pinchuk, who had acquired state firm Nikopol Ferroalloy for $80 million, independently valued at $1 billion.[33] In response to the allegations, Yushchenko dismissed his entire cabinet of ministers, including Poroshenko and Tymoshenko.[34] State prosecutors dismissed an abuse of power investigation against Poroshenko the following month,[35] immediately after Yushchenko dismissed Svyatoslav Piskun, General Prosecutor of Ukraine. Piskun claimed that he was sacked because he refused to institute criminal proceedings against Tymoshenko and refused to drop proceedings against Poroshenko.[36]

In the March 2006 parliamentary election Poroshenko was re-elected to the Ukrainian parliament with the support of Our Ukraine electoral bloc.[18] He chaired the parliamentary Committee on Finance and Banking. Allegedly, since Poroshenko claimed the post of Chairman of the Ukrainian Parliament for himself, the Socialist Party of Ukraine chose to be part of the Alliance of National Unity because it was promised that their party leader, Oleksandr Moroz, would be elected chairman if the coalition were formed.[34] This left Poroshenko's Our Ukraine and their ally Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc out of the Government.

Poroshenko did not run in the September 2007 parliamentary election.[18] Poroshenko started heading the Council of Ukraine's National Bank in February 2007.[34][37] Between 1999 and 2012 he was a board member of the National Bank of Ukraine.[18]

Foreign Minister and Minister of Trade

Ukrainian President Yushchenko nominated Poroshenko for Foreign Minister on 7 October 2009.[37][38] Poroshenko was appointed by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament) on 9 October 2009.[39][40] On 12 October 2009, President Yushchenko re-appointed Poroshenko to the National Security and Defense Council.[41] Poroshenko supported Ukrainian NATO-membership. However, he also stated NATO membership should not be a goal in itself.[42] Although Poroshenko was dismissed as foreign minister on 11 March 2010, President Viktor Yanukovych expressed hope for further cooperation with him.[23]

In late February 2012 Poroshenko was named as the new Minister of Trade and Economic Development in the Azarov Government;[43][44][45] on 9 March 2012 President Yanukovych stated he wanted Poroshenko to work in the government in the post of economic development and trade minister.[46] On 23 March 2012 Poroshenko was appointed economic development and trade minister of Ukraine by Yanukovych.[47] The same month he stepped down as head of the Council of Ukraine's National Bank.[48]

Poroshenko claims that he became Minister of Trade and Economic Development in order to help bring Ukraine closer to the EU and get Yulia Tymoshenko released from prison.[2] After he took the post, tax inspectors launched an attack on his business.[2]

Return to parliament

Poroshenko returned to the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) after the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election after winning (with more than 70%) as an independent candidate in single-member district number 12 (first-past-the-post wins a parliamentary seat) located in Vinnytsia Oblast.[49][50][51] He did not enter any faction in parliament[52] and became member of the committee on European Integration.[2] Poroshenko's father Oleksiy did intend to take part in the elections too in single-member district number 16 (also located in Vinnytsia Oblast), but withdrew his candidacy for health reasons.[53][54] In mid-February 2013, Poroshenko hinted he would run for Mayor of Kiev in the 2013 Kiev mayoral election.[55]

2014 Ukrainian revolution

During the Euromaidan protests, between November 2013 and February 2014, Poroshenko actively supported the protest, including with financial support.[18] This led to an upsurge of his popularity.[18] He did not participate in negotiations between then President Yanukovych and the Euromaidan Maidan parliamentary opposition parties Batkivshchyna, Svoboda and UDAR.[18]

Poroshenko refused to join the Yatsenyuk Government (although he introduced his colleague Volodymyr Groysman, the mayor of Vinnitsa, into it), and nor did he join any of the two newly created parliamentary factions Economic Development and Sovereign European Ukraine.[18] During the 2014 Crimean crisis Poroshenko visited Simferopol, in Crimea, prior to its annexation by Russia; "We have to find a compromise," Poroshenko told a crowd gathered in front of the Crimean parliament, but his appeal was drowned by shouts of "Russia, Russia."[2]

In an interview with Lally Weymouth, Poroshenko said: "From the beginning, I was one of the organizers of the Maidan. My television channel — Channel 5 — played a tremendously important role. ... At that time, Channel 5 started to broadcast, there were just 2,000 people on the Maidan. But during the night, people went by foot — seven, eight, nine, 10 kilometers — understanding this is a fight for Ukrainian freedom and democracy. In four hours, almost 30,000 people were there."[56] The BBC reported, "Mr Poroshenko owns 5 Kanal TV, the most popular news channel in Ukraine, which showed clear pro-opposition sympathies during the months of political crisis in Kiev."[9]

2014 presidential campaign

Following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the resulting removal of Viktor Yanukovych from the office of President of Ukraine, new presidential elections were scheduled to take place on 25 May 2014.[57] In pre-election polls from March 2014, Poroshenko garnered the most support of all the prospective candidates, with one poll conducted by SOCIS giving him a rating of over 40%.[58] On 29 March he stated that he would run for president; at the same time Vitali Klitschko left the presidential contest, choosing to support Poroshenko's bid.[59][60][61][62]

On 2 April Poroshenko stated, "If I am elected, I will be honest and sell the Roshen Concern."[63] He also said in early April that the level of popular support for the idea of Ukraine's joining NATO was too small to put on the agenda "so as not to ruin the country."[64] He also vowed not to sell his 5 Kanal television channel.[65] On 14 April, Poroshenko publicly endorsed the campaign of Jarosław Gowin's party Poland Together of neighbouring Poland in this year's elections to the European Parliament, thanking Gowin's party colleague Paweł Kowal for supporting Ukraine.[66]

Poroshenko's election slogan was: "Live in a new way – Poroshenko!".[2] On 29 May, the Central Election Commission of Ukraine announced that Poroshenko had won 25 May presidential election, with 54.7% of the votes.[67]

During his visit in Berlin, Poroshenko stated that separatists "don't represent anybody. We have to restore law and order and sweep the terrorists off the street."[68] He described as "fake" a planned 11 May Donbass status referendums.[68]

Presidency

When it became clear he had won the election on election day evening (on 25 May 2014) Poroshenko announced "My first presidential trip will be to Donbas", where armed pro-Russian rebels had declared the separatist republics Donetsk People's Republic and Lugansk People's Republic and control a large part of the region.[65][69] Poroshenko also vowed to continue the military operations by the Ukrainian government forces to end the armed insurgency claiming "The anti-terrorist operation cannot and should not last two or three months. It should and will last hours."[70] He compared the armed pro-Russian rebels to Somali pirates.[70] Poroshenko also called for negotiations with Russia in the presence of international intermediaries.[70] Russia responded by saying it did not need an intermediary in its bilateral relations with Ukraine.[70] As president-elect Poroshenko promised to return Crimea,[70] which was annexed by Russia in March 2014.[69][71][a] He also vowed to hold new parliamentary elections in 2014.[73]

Inauguration

Poroshenko was inaugurated in the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) on 7 June 2014.[8] In his inaugural address he stressed that Ukraine would not give up Crimea and stressed the unity of Ukraine.[74] He promised an amnesty "for those who do not have blood on their hands" to the separatist and pro-Russia insurgents of the 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine and to the Ukrainian nationalist groups that oppose them, but added: "Talking to gangsters and killers is not our path".[74] He also called for early regional elections in Eastern Ukraine.[74] Poroshenko also stated that he would sign the economic part of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement and that this was the first step towards full Ukrainian EU Membership.[74] During the speech he stated he saw "Ukrainian as the only state language" but also spoke of the "guarantees [of] the unhindered development of Russian and all the other languages".[74] Part of the speech was in Russian.[74]

The inauguration was attended by about 50 foreign delegations, including US Vice President Joe Biden, President of Poland Bronisław Komorowski, President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko, President of Lithuania Dalia Grybauskaitė, President of Switzerland and the OSCE Chairman-in-Office Didier Burkhalter, President of Germany Joachim Gauck, President of Georgia Giorgi Margvelashvili, Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Hungary Viktor Orbán, President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy, the OSCE Secretary General Lamberto Zannier, UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Jeffrey Feldman, China's Minister of Culture Cai Wu and Ambassador of Russia to Ukraine Mikhail Zurabov[75][76] Former Prime Minister of Ukraine Yulia Tymoshenko was also present.[74][75] After the inauguration ceremony Tymoshenko said about Poroshenko "I think Ukraine has found a very powerful additional factor of stability".[77]

Domestic policy

Peace plan for Eastern Ukraine

At the time of his inauguration armed pro-Russian rebels, after a disputed referendums, considered to be illegitimate by the international community, had declared the separatist republics Donetsk People's Republic and Lugansk People's Republic and control a large part of Eastern Ukraine.[65][69] Poroshenko (after his inauguration) launched a so-called "peace" plan envisaged for the recognition of the presidential elections in Ukraine by Russia, a cease-fire by the separatists (named "terrorists" by Poroshenko himself) and the establishment of humanitarian corridor for civilians ("who are not involved in the conflict").[78] Poroshenko warned that he had a "Plan B".[79]

Poroshenko pledged revenge against separatists after 19 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in a rocket attack: "Militants will pay hundreds of their lives for each life of our servicemen. Not a single terrorist will avoid responsibility. Each of them will be punished".[80]

First Lady of Ukraine Maryna Poroshenko met with Iryna Herashchenko, an envoy to the Peace plan for Eastern Ukraine to discuss possible assistance for people in the affected region.[81]

In December 2014, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KhPG) condemned Poroshenko for granting Ukrainian citizenship to Belarusian neo-Nazi and Azov Battalion commander of reconnaissance Serhiy Korotkykh.[82]

Poroshenko didn't agree to give the autonomous status for Donbass,[83] saying, "Despite strong insistence, we didn't agree to any autonomous status. .. We didn't agree to any compromise on federalization either. There is no autonomy or federalization in the [Minsk] document."[84]

Reforms in Ukraine

Constitutional reform

Decentralization of power

In mid-June Poroshenko started the process of amending Ukraine's constitution to achieve Ukraine's administrative decentralization.[85] According to Poroshenko (on 16 June 2014) this was "a key element of the peace plan".[85] In his draft constitutional amendments of June 2014 proposed changing the administrative divisions of Ukraine, which should include regions (replacing the current oblasts), districts and "hromadas" (communities).[86] In these amendments he also proposed that "Village, city, district and regional administrations will be able to determine the status of the Russian language and other national minority languages of Ukraine in accordance with the procedure established by the law and within the borders of their administrative and territorial units".[87] He proposed that Ukrainian remained the only state language of Ukraine.[87] Poroshenko further proposed to create the post of presidential representatives who would supervise the enforcement of the Ukrainian constitution and laws and the observation of human rights and freedoms in oblasts and raions/raions of cities.[88] In case of an "emergency situation or martial law regime" they will "guide and organize" in the territories they are stationed in.[88] Batkivshchyna, key coalition partner in the Yatsenyuk Government, came out against the plan.[89]

Poroshenko has repeatedly spoken out against federalization.[84][90]

Poroshenko does not seek to increase his presidential powers.[91]

1 July 2015 decentralization draft law gave local authorities the right to oversee how their tax revenues are spent.[92] The draft law did not give an autonomous status to Donbass, as demanded by the pro-Russian rebels there, but gave the region partial self-rule for three years.[92]

Dissolution of Parliament

On 25 August 2014, Poroshenko called a snap election to the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament), to be held 26 October 2014.[93][94] According to him this was necessary "to purify the Rada of the mainstay of [former president] Viktor Yanukovych". These deputies, Poroshenko said, "clearly do not represent the people who elected them".[95] Poroshenko also said that these Rada deputies were responsible for "the [January 2014] Dictatorship laws that took the lives of the Heavenly hundred".[95] Poroshenko also stated that many of the (then) current MPs were "direct sponsors and accomplices or at least sympathizers of militants-separatists".[95]

Poroshenko had pressed for the elections since his victory in the May 2014 presidential election.[96][97][98]

During a 27 August 2014, the party congress of the party "Solidarity" adopted a new name: "Petro Poroshenko Bloc".[99] "Solidarity" was Poroshenko's former party.[100][101] Because in Ukraine the President is not allowed to be member of a party,[102] Poroshenko became "Bloc of Petro Poroshenko" "Honorary Leader".[99]

Nuclear weapons

On 13 December 2014 Poroshenko stated that he did not want Ukraine to become a nuclear power again.[103]

Decommunization and deoligarchization

On 15 May 2015 Poroshenko signed a bill into law that started a six months period for the removal of communist monuments and the mandatory renaming of streets and other public places and settlements with a name related to Communism.[104] According to Poroshenko this was "I did what I had to"; adding "Ukraine as a state has done its job, then historians should work, while the government should take care of the future".[104] Poroshenko believes that the Nazi crimes are on a par with the communist crimes of the Soviet Union.[105] The legislation (Poroshenko signed on 15 May 2015) also provides "public recognition to anyone who fought for Ukrainian independence in the 20th century",[106] including the controversial Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) combatants led by Roman Shukhevych and Stepan Bandera.[104] Poroshenko sees UPA separatist rebels fighting Polish and Soviet authorities in west Ukraine in the 1930s and 1940s as "an example of heroism and patriotism to Ukraine."[107]

Poroshenko said in an interview with Germany's Bild newspaper that "If I am elected, I'll wipe the slate clean and will sell the Roshen concern. As president of Ukraine, I will and want to only focus on the well-being of the nation."[108]

On 23 March 2015 Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko has accepted the resignation of billionaire Ihor Kolomoisky as governor of Dnipropetrovsk region over the control of oil companies.[109] "There will be no more oligarchs in Ukraine," Poroshenko said adding that "oligarchs must pay more [taxes] that the middle class and more than small business." The president underscored that "the program of de-oligarchization will be put into life". Poroshenko promise that he will fight against the Ukrainian oligarchs.[110]

Anti-corruption

Poroshenko has signed a decree to approve regulations on the Council of Public Control under the Anti-Corruption Bureau and regulations on setting up the mentioned council.

Foreign policy

United States

On 7 December 2015 Poroshenko had a meeting with U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Kiev which discussed the Ukrainian-American cooperation.[111]

Russia

In June 2014 Poroshenko forbade any cooperation with Russia in the military sphere.[112]

At the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe on 26 June 2014 Poroshenko stated that bilateral relations with Russia cannot be normalized unless Russia undoes its unilateral annexation of Crimea and returns its control of Crimea to Ukraine.[113]

On Poroshenko's June 2014 Peace plan for Eastern Ukraine Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov commented "it looks like an ultimatum".[79]

On 26 August 2014 Poroshenko met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Minsk where Putin called on Ukraine not to escalate its offensive. Poroshenko responded by demanding Russia halt its supplying of arms to separatist fighters. He said his country wanted a political compromise and promised the interests of Russian-speaking people in eastern Ukraine would be considered.[114]

European Union

The European Union (EU) and Ukraine signed the economic part of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement on 27 June 2014.[115] Poroshenko stated that the day was "Ukraine's most historic day since independence in 1991", describing it as a "symbol of faith and unbreakable will".[115] He saw the signing as the start of preparations for Ukrainian EU Membership.[115]

NATO

At his speech at the opening session of the new parliament on 27 November 2014 Poroshenko stated "we've decided to return to the course of NATO integration" because "the nonalignment status of Ukraine proclaimed in 2010 couldn't guarantee our security and territorial integrity".[116] The Ukrainian parliament on 23 December 2014 voted 303 to 8 to repeal a 2010 bill that had made Ukraine a non-aligned state in a bill submitted by Poroshenko.[117] On 29 December 2014 Poroshenko vowed to hold a referendum on joining NATO.[118] On 22 September 2015 Poroshenko claimed that "Russia's aggressive actions" proved need for the enlargement of NATO and that the Ukrainian referendum on joining NATO would be held after "every condition for the Ukrainian compliance with NATO membership criteria" was met by "reforming our country".[119]

International

Poroshenko was criticized by Committee to Protect Journalists for signing a decree which banned 41 international journalists and bloggers from entering Ukraine for one year, being labeled as threats to national security.[120] The list includes three BBC journalists, and two Spanish journalist currently missing in Syria, all of whom previously covered the Ukraine crisis.[121]

International trips

Panama Papers

Poroshenko set up an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands during the peak of the war in Donbass.[122] Leaked documents from the Panama Papers show that Poroshenko registered the company, Prime Asset Partners Ltd, on 21 August 2014. Records in Cyprus show him as the firm's only shareholder.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). He said that he had done nothing wrong, and the legal firm, Avellum, overseeing the sale of Roshen, Poroshenko's confectionery company, said that "any allegations of tax evasion are groundless". The anti-corruption group Transparency International believes that the "creation of businesses while serving as president is a direct violation of the constitution".[123]

Personal life

Poroshenko has been married to Maryna since 1984.[18] The couple have four children: Oleksiy (born 1985), the twins Yevheniya and Oleksandra (born 2000) and Mykhaylo (born 2001).[18] Oleksiy is a representative in the regional parliament of Vinnytsia Oblast.[2] Maryna Poroshenko is a cardiologist, who does not take part in public life, apart from her participation in the activities of the Petro Poroshenko Charity Foundation.[18] Poroshenko became a grandfather on the day of his presidential inauguration of 7 June 2014.[124]

Poroshenko is a member of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.[1][2] Poroshenko has financed the restoration of its buildings and monasteries.[1] In high-level meetings he is often seen with a crucifix.[1]

Poroshenko speaks fluent Ukrainian, Russian, English and Romanian.

Cultural and political image

In Ukraine, Poroshenko is widely seen as a pragmatic politician who sees Ukraine's future in the European Union, but hopes to mend relations with Russia.[9] He is nicknamed 'Chocolate King' because of his ownership of a large confectionery business.[9]

In 2006, John Herbst, US Ambassador to Ukraine, described Poroshenko as a "disgraced oligarch."[125] Later that same year Sheila Gwaltney, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Ukraine, said that "Poroshenko was tainted by credible corruption allegations."[125]

Poroshenko has stated that "Oligarchs are people who seek power in order to further enrich themselves. But I have long fought against bandits who are robbing our country and have destroyed free enterprise".[2] In early 2014, the Russian television station NTV aired a film which portrayed Poroshenko extremely negatively.[2]

Awards

Ukraine : Order of Merit

Ukraine : Order of Merit Moldova : Order of the Republic (Moldova)

Moldova : Order of the Republic (Moldova) Poland : Order of the White Eagle

Poland : Order of the White Eagle Spain : Order of Civil Merit

Spain : Order of Civil Merit Ukraine : Medal of winner of Ukraine State Prize in Science and Technology

Ukraine : Medal of winner of Ukraine State Prize in Science and Technology

Notes

- ^ The status of the Crimea and of the city of Sevastopol is currently under dispute between Russia and Ukraine; Ukraine and the majority of the international community consider the Crimea to be an autonomous republic of Ukraine and Sevastopol to be one of Ukraine's cities with special status, while Russia, on the other hand, considers the Crimea to be a federal subject of Russia and Sevastopol to be one of Russia's three federal cities.[69][72]

References

- ^ a b c d e Luke Harding and Oksana Grytsenko (23 May 2014). "Chocolate tycoon heads for landslide victory in Ukraine presidential election". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"The Return of the Prodigal Son, Who Never Left Home". The Ukrainian Week. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Who will lead Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and where?". Den. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Ukraine Election: The Chocolate King Rises". Spiegel Online. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the III convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the IV convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "Registered candidates". Elections of the People's Deputies of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the V convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the VII convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ a b Lukas Alpert (29 May 2014). "Petro Poroshenko to Be Inaugurated as Ukraine President June 7". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Rada decides to hold inauguration of Poroshenko on June 7 at 1000". Interfax-Ukraine. 3 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Poroshenko sworn in as Ukrainian president". Interfax-Ukraine. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f "Profile: Ukraine's President Petro Poroshenko". BBC. 7 June 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine talks set to open without pro-Russian separatists". The Washington Post. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine elections: Runners and risks". BBC News. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Q&A: Ukraine presidential election". BBC News. 7 February 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko wins presidential election with 54.7% of vote – CEC". Radio Ukraine International. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Внеочередные выборы Президента Украины (in Russian). Телеграф. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Ukrainian president will be elected for 5-year term – Constitutional Court". Interfax-Ukraine. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Petro Poroshenko Net Worth". The Richest. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kerry heads for crisis talks over Ukraine". The Scotsman. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Marcin Kosienkowski (2012). "Continuity and Change in Transnistria's Foreign Policy after the 2011 Presidential Elections". Academia.edu. p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Tadeusz A. Olszański; Agata Wierzbowska-Miazga (28 May 2014). "Poroshenko, President of Ukraine". OSW, Poland. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Ukraine's tycoon Poroshenko confirms plans to sell assets". ITAR-TASS. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Uk icon Saakashvili took over as head of the Odessa Regional State Administration, Deutsche Welle (30 May 2015)

- ^ Template:Ru icon/(website has automatic Google Translate option) Short bio, LIGA

- ^ Abram Brown (31 March 2014). "The Willy Wonka of Ukraine Is Now The Leading Presidential Candidate". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Poroshenko is not going to sell Channel 5 TV". Kyiv Post. 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 1 December 2008 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brian Bonner (8 March 2012). "Eight Ukrainians make Forbes magazine's list of world billionaires". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Billionaire No More: Ukraine President's Fortune Fades With War". Bloomberg Business. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Vitaliy Sych (30 October 2015). Порошенко растет, Ахметов падает – свежий Топ-100 самых богатых украинцев [Poroshenko grows, Akhmetov falls – Fresh Top 100 richest Ukrainians] (in Russian). Novoe Vremia. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Концерн "Укрпромінвест" оголосив про ліквідацію (in Ukrainian). UNIAN. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 1 December 2008 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Kuzio, Taras; Frishberg, Alex (21 February 2008). "Ukrainian Political Update" (PDF). Frishberg & Partners, Attorneys at Law. p. 22.

- ^ "New "region" formed in Ukrainian Parliament No. 13/2013" (PDF). Central European University. 26 March 2001. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Results of voting in single-mandate constituencies". Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Retrieved 23 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Freedom House (2004). Nations in Transit 2004: Democratization in East Central Europe and Eurasia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 638–. ISBN 978-1-4617-3141-2.

- ^ Hanly, Ken (25 May 2014). "Op-Ed: Petro Poroshenko the oligarch poised to become Ukraine president". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alex Rodriguez (27 September 2005). "In Ukraine, old whiff of scandal in new regime". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Biography" (in Russian). Korrespondent.net. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Prosecutors Close Criminal Case Against Yushchenko's Close Ally". Kiev Ukraine News Blog. 21 October 2005.

- ^ Tammy M. Lynch (28 October 2005). "Independent standpoint on Ukraine:Dismissal of Prosecutor-General, Closure of Poroshenko Case Create New". ForUm. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Regions Party not to vote for Poroshenko's appointment Ukraine's foreign minister". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "Ukrainian president proposes Petro Poroshenko for foreign minister". Interfax-Ukraine. 7 October 2009.

- ^ "Rada appoints Poroshenko Ukraine's foreign minister". Interfax-Ukraine. 9 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ By 240 out of 440 MPs registered in the session hall. In particular, 151 MPs of the Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko faction, 63 of the Our Ukraine-People's Self-Defense Bloc, 20 members of the Bloc of Volodymyr Lytvyn, one deputy of the Party of Regions, one member of the Communist Party faction, and four deputies not belonging to any faction voted for the nomination.

- ^ "Poroshenko put on Ukraine's NSCD". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 12 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko: Ukraine could join NATO in 1–2 years, with political, public will". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "Mass Media:Poroshenko heads Ministry of Economy". UNIAN. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Regions Party: Poroshenko appointed economy minister, Kolobov appointed finance minister". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "President:Prime Minister nominated Petro Poroshenko for Minister of Economy". President.gov.ua. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Ukrainian president wants Poroshenko to head economic development and trade ministry". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko appointed economic development and trade minister of Ukraine". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Poroshenko explains reasons behind accepting economy minister's post". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012. - ^ Порошенко Петр Алексеевич [Petr Aleksiyovych Poroshenko] (in Russian). LIGA.net. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Uk icon Candidates single-mandate constituency № 12, RBC Ukraine

- ^ Полтавська область. Одномандатний виборчий округ №112 (in Ukrainian). Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Minister Poroshenko and his father registered as self-nominees for Vinnytsia region". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko not intending to join any faction". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Poroshenko fears uncontrolled economic situation in Ukraine due to foreign borrowing". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Uk icon Candidates single-mandate constituency № 16, RBC Ukraine

- ^ "Poroshenko's father changes his mind to withdraw his candidacy from elections". UNIAN. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko appears set to join race for Kyiv mayor". Ukraine Business Online. 12 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Interview with Ukrainian presidential candidate Petro Poroshenko". The Washington Post. 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: Speaker Oleksandr Turchynov named interim president". BBC News. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Ukraine protests timeline". BBC News. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 1 December 2008 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Главная | Центр соціальних та маркетингових досліджень SOCIS. Socis.kiev.ua. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Klitschko will run for mayor of Kyiv". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Klitschko believes only presidential candidate from democratic forces should be Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 11 October 2014 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Colin Freeman (29 March 2014). "Petro Poroshenko, the billionaire chocolate baron hoping to become Ukraine's next president". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine: former boxer Vitaliy Klitschko ends presidential bid and backs Poroshenko". Euronews. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko ready to sell Roshen if elected president". Interfax-Ukraine. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Question of Ukraine's membership of NATO may split country – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Poroshenko Declares Victory in Ukraine Presidential Election". The Wall Street Journal. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Polska Razem czarnym koniem? Mocne słowa Gowina" (in Polish). 12 April 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko wins presidential election with 54.7% of vote – CEC". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 May 2014 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Poroshenko: 'No negotiations with separatists'". Deutsche Welle. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Ukraine crisis timeline". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Poroshenko promises calm 'in hours' amid battle to control Donetsk airport". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "EU & Ukraine 17 April 2014 FACT SHEET" (PDF). European External Action Service. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Gutterman, Steve; Polityuk, Pavel (18 March 2014). "Putin signs Crimea treaty, will not seize other Ukraine regions". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "In Ukrainian election, chocolate tycoon Poroshenko claims victory". The Washington Post. 25 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ukraine president vows not to give up Crimea". The Guardian. theguardian.com. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Ukraine's Poroshenko sworn in and sets out peace plan". BBC News. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Excerpts from Poroshenko's speech". BBC News Online. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Ukraine's President Poroshenko pushes for peace at inauguration". Euronews. 7 June 2014.

"Poroshenko offers escape for rebels but no compromise over weapons". Euronews. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Промова президента України під час церемонії інавгурації. Повний текст [Speech by President of Ukraine during the inauguration ceremony. Full text]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. - ^ a b На інавгурацію Порошенка прибудуть делегації з 56 країн. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine: International recognition for President Poroshenko". Euronews. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Тимошенко: президент Порошенко – потужний фактор стабільності. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko doesn't rule out roundtable in Donetsk involving parties to conflict". Interfax-Ukraine. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko warns of 'detailed Plan B' if Ukraine ceasefire fails". Al Jazeera. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine president vows revenge after 19 soldiers killed in rebel rocket attack". The Washington Post. 11 July 2014.

- ^ "Maryna Poroshenko: 'I read Kyiv Post'". Kyiv Post. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Coynash, Halya (8 December 2014). "Poroshenko grants Belarusian Neo-Nazi Ukrainian citizenship". Human Rights in Ukraine. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine's warring parties agree to February 15 ceasefire". France 24. 12 February 2015

- ^ a b "Documents signed in Minsk don't envision federalization, autonomy for Donbas – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Amendments to Ukraine's Constitution to be tabled in parliament this week – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko suggests granting status of regions to Crimea, Kyiv, Sevastopol, creating new political subdivision of 'community'". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Authorities in Ukrainian regions may be allowed to determine status of national minority languages". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Ukrainian president proposes to appoint representatives to regions". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine's Poroshenko names new defence chiefs in shake-up". Reuters. 3 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Poroshenko rules out federalization of Ukraine. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 June 2015.

Ukraine to remain unitary state after constitution is amended – Poroshenko. Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2015. - ^ Semi-presidential form of government is optimal for Ukraine – Poroshenko. Interfax-Ukraine. 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b Poroshenko Unveils Constitutional Changes, Radio Free Europe (1 July 2015)

- ^ "Ukraine President Poroshenko Calls Snap General Election". Bloomberg News. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: President calls snap vote amid fighting". BBC News. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Ukrainian President dissolves Parliament, announces early elections, United Press International (25 August 2014)

"Ukraine's Petro Poroshenko Dissolves Parliament, Sets Election Date". The Moscow Times. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

President's address on the occasion of early parliamentary elections of 26 October, Presidential Administration of Ukraine (25 August 2014) - ^ "Poroshenko hopes early parliamentary elections in Ukraine will take place in October". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poroshenko hopes for early parliamentary elections in Ukraine this fall – presidential envoy". Interfax-Ukraine. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "In Ukrainian election, chocolate tycoon Poroshenko claims victory". The Washington Post. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko wants coalition to be formed before parliamentary elections". Interfax-Ukraine. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 July 2014 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Solidarity Party to be renamed Bloc of Petro Poroshenko – congress". Interfax-Ukraine. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Петро Порошенко виходить на роботу" [Poroshenko goes to work]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 6 June 2014.

- ^ Порошенко і порожнеча (in Ukrainian). 16 May 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine's Party of Regions to choose new leader". RIA Novosti. 23 April 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ukraine has no ambitions to become nuclear power again – Poroshenko, Interfax-Ukraine (13 December 2014)

- ^ a b c Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunization. Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes, Interfax-Ukraine. 15 May 20

Poroshenko: Time for Ukraine to resolutely get rid of Communist symbols, UNIAN. 17 May 2015

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015) - ^ Порошенко: час очистити Україну від комуністичних символів [Poroshenko: time to clear Ukraine of communist symbols]. BBC Ukrainian (in Ukrainian). 17 May 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine to rewrite Soviet history with controversial 'decommunisation' laws ". The Guardian. 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine Makes Amnesia the Law of the Land ". 21 May 2015.

- ^ "Poroshenko to Sell Roshen If Elected Ukrainian President: Bild". Bloomberg. 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Powerful Ukrainian Governor Kolomoyskiy Resigns". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "IN UKRAINE THERE WILL BE NO MORE OLIGARCHS – POROSHENKO". 5.ua. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Meeting Poroshenko and Biden: main results". nv.ua. 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Порошенко заборонив будь-яку співпрацю з Росією у військовій сфері. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine cannot normalize relations with Russia without return of Crimea, says Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Eastern Ukraine tensions figure in Putin and Poroshenko talks". Moscow News. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "EU signs pacts with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova". BBC News. 27 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ A Tilt Toward NATO in Ukraine as Parliament Meets, The Wall Street Journal (27 November 2014)

- ^ "Ukraine has no alternative to Euro-Atlantic integration – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Ukraine abolishes its non-aligned status – law". Interfax-Ukraine. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Ukraine's complicated path to NATO membership". Euronews. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Ukraine Takes Step Toward Joining NATO". New York Times. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Ukraine Ends 'Nonaligned' Status, Earning Quick Rebuke From Russia". The Wall Street journal. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Year, new hope as Ukraine paves way for NATO membership". Euronews. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Russia's actions prove need for NATO expansion – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Decision on referendum regarding Ukraine's membership in NATO to be made after reforms – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

"Ukraine-NATO cooperation is crucially important for global security due to Russian aggression – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2016. - ^ "Ukraine bans 41 international journalists and bloggers". CPJ. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Umberto Bacchi (17 September 2015). "Ukraine: BBC boss slams 'shameful' ban on international journalists". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel; Prentice, Alessandra (4 April 2016). "Ukraine's Poroshenko defends record after Panama leaks". Reuters. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Panama Papers: Ukraine President Poroshenko denies tax claims". BBC News. 4 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Порошенко став дідом. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The not-very-nice things U.S. officials used to say about Ukraine's new president". The Washington Post. 29 May 2014.

External links

- Official website for the President of Ukraine

- Official page on Facebook

- Official page on Twitter

- Official channel on YouTube

- Official page on Google+

- Official page on Vkontakte

- Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Template:Uk icon

- Euromaidan Overview

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Pages with reference errors that trigger visual diffs

- 1965 births

- Businesspeople in confectionery

- Candidates for President of Ukraine (2014)

- Economic development and trade ministers of Ukraine

- Foreign ministers of Ukraine

- Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit

- Independent politicians in Ukraine

- Petro Poroshenko Bloc politicians

- Living people

- People from Bolhrad

- People of the Euromaidan

- People of the Orange Revolution

- Presidents of Ukraine

- Pro-Ukrainian people of the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Ukraine), 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Ukraine), 3rd class

- Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (united) politicians

- Third convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada

- Fourth convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada

- Fifth convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada

- Seventh convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada

- Secretaries of National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine

- Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv alumni

- Ukrainian anti-communists

- Ukrainian billionaires

- Ukrainian manufacturing businesspeople

- Ukrainian mass media owners

- Members of Ukrainian Orthodox church bodies

- Pro-Ukrainian people of the war in Donbass

- Solidarity Party (Ukraine) politicians