Siberia

60°0′N 105°0′E / 60.000°N 105.000°E

Siberia (/saɪˈbɪəriə/; Russian: Сиби́рь, romanized: Sibir', IPA: [sʲɪˈbʲirʲ] ) is an extensive geographical region, and by the broadest definition is also known as North Asia. Siberia has historically been a part of Russia since the 16th and 17th centuries.

The territory of Siberia extends eastwards from the Ural Mountains to the watershed between the Pacific and Arctic drainage basins. The Yenisei River conditionally divides Siberia into five parts, Western and Eastern. Siberia stretches southwards from the Arctic Ocean to the hills of north-central Kazakhstan and to the national borders of Mongolia and China.[1] With an area of 13.1 million square kilometres (5,100,000 sq mi), Siberia accounts for 77% of Russia's land area, but it is home to just 40 million people—27% of the country's population. This is equivalent to an average population density of about 3 inhabitants per square kilometre (7.8/sq mi) (approximately equal to that of Australia), making Siberia one of the most sparsely populated regions on Earth. If it were a country by itself, it would still be the largest country in area, but in population it would be the world's 35th-largest and Asia's 14th-largest.

Worldwide, Siberia is well known primarily for its long, harsh winters, with a January average of −25 °C (−13 °F), as well as its extensive history of use by Russian and Soviet administrations as a place for prisons, labor camps, and exile.

Etymology

The origin of the name is unknown. Some sources say that "Siberia" originates from the Siberian Tatar word for "sleeping land" (Sib Ir).[2] Another account sees the name as the ancient tribal ethnonym of the Sirtya (also "Syopyr" (sʲɵpᵻr)), a folk, which spoke a language that later evolved into the Ugric languages. This ethnic group was later assimilated to the Siberian Tatar people.

The modern usage of the name was recorded in the Russian language after the Empire's conquest of the Siberian Khanate. A further variant claims that the region was named after the Xibe people.[3] The Polish historian Chycliczkowski has proposed that the name derives from the proto-Slavic word for "north" (север, sever),[4] but Anatole Baikaloff has dismissed this explanation.[5] He said that the neighbouring Chinese, Turks and Mongolians (who have similar names for the region) would not have known Russian. He suggests that the name is a combination of two words, "su" (water) and "bir" (wild land).

Prehistory

The region is of paleontological significance, as it contains bodies of prehistoric animals from the Pleistocene Epoch, preserved in ice or permafrost. Specimens of Goldfuss cave lion cubs, Yuka (mammoth) and another woolly mammoth from Oymyakon, a woolly rhinoceros from the Kolyma River, and bison and horses from Yukagir have been found here.[6]

The Siberian Traps were formed by one of the largest-known volcanic events of the last 500 million years of Earth's geological history. They continued for a million years and are considered a possible cause of the "Great Dying" about 250 million years ago,[7] which is estimated to have killed 90% of species existing at the time.[8]

At least three species of human lived in Southern Siberia around 40,000 years ago: H. sapiens, H. neanderthalensis, and the Denisovans.[9] The last was determined in 2010, by DNA evidence, to be a new species.

History

Siberia was inhabited by different groups of nomads such as the Enets, the Nenets, the Huns, the Scythians and the Uyghurs. The Khan of Sibir in the vicinity of modern Tobolsk was known as a prominent figure who endorsed Kubrat as Khagan of Old Great Bulgaria in 630. The Mongols conquered a large part of this area early in the 13th century. [citation needed]

With the breakup of the Golden Horde, the autonomous Khanate of Sibir was established in the late 15th century. Turkic-speaking Yakut migrated north from the Lake Baikal region under pressure from the Mongol tribes during the 13th to 15th century.[10] Siberia remained a sparsely populated area. Historian John F. Richards wrote: "... it is doubtful that the total early modern Siberian population exceeded 300,000 persons."[11]

The growing power of Russia in the West began to undermine the Siberian Khanate in the 16th century. First, groups of traders and Cossacks began to enter the area. The Russian Army was directed to establish forts farther and farther east to protect new settlers from European Russia. Towns such as Mangazeya, Tara, Yeniseysk and Tobolsk were developed, the last being declared the capital of Siberia. At this time, Sibir was the name of a fortress at Qashlik, near Tobolsk. Gerardus Mercator, in a map published in 1595, marks Sibier both as the name of a settlement and of the surrounding territory along a left tributary of the Ob.[12] Other sources[which?] contend that the Xibe, an indigenous Tungusic people, offered fierce resistance to Russian expansion beyond the Urals. Some suggest that the term "Siberia" is a Russification of their ethnonym.

By the mid-17th century, Russia had established areas of control that extended to the Pacific. Some 230,000 Russians had settled in Siberia by 1709.[13] Siberia was a destination for sending exiles.[14]

The first great modern change in Siberia was the Trans-Siberian Railway, constructed during 1891–1916. It linked Siberia more closely to the rapidly industrialising Russia of Nicholas II. Around seven million people moved to Siberia from European Russia between 1801 and 1914.[15] From 1859 to 1917, more than half a million people migrated to the Russian Far East.[16] Siberia has extensive natural resources. During the 20th century, large-scale exploitation of these was developed, and industrial towns cropped up throughout the region.[17]

At 7:15 a.m. on 30 June 1908, millions of trees were felled near the Podkamennaya Tunguska (Stony Tunguska) River in central Siberia in the Tunguska Event. Most scientists believe this resulted from the air burst of a meteor or a comet. Even though no crater has ever been found, the landscape in the (uninhabited) area still bears the scars of this event.

In the early decades of the Soviet Union (especially the 1930s and 1940s), the government established the GULAG state agency to administer a system of penal labour camps, replacing the previous katorga system.[18] According to semi-official Soviet estimates, which were not made public until after the fall of the Soviet government, from 1929 to 1953 more than 14 million people passed through these camps and prisons, many of which were in Siberia. Another 7 to 8 million people were internally deported to remote areas of the Soviet Union (including entire nationalities or ethnicities in several cases).[19]

Half a million (516,841) prisoners died in camps from 1941 to 1943[20] due to food shortages caused by World War II. At other periods, mortality was comparatively lower.[21] The size, scope, and scale of the GULAG slave labour camps remains a subject of much research and debate. Many Gulag camps were positioned in extremely remote areas of northeastern Siberia. The best known clusters are Sevvostlag (The North-East Camps) along the Kolyma River and Norillag near Norilsk, where 69,000 prisoners were kept in 1952.[22] Major industrial cities of Northern Siberia, such as Norilsk and Magadan, developed from camps built by prisoners and run by ex-prisoners.[23]

Geography

| Physical map of Northern Asia (with parts of Central and East Asia) | ||

|---|---|---|

With an area of 13.1 million square kilometres (5,100,000 sq mi), Siberia makes up roughly 77% of Russia's total territory and almost 10% of Earth's land surface (148,940,000 km2, 57,510,000 sq mi). While Siberia falls entirely within Asia, many authorities such as the UN geoscheme will not subdivide countries and will place all of Russia as part of Europe and/or Eastern Europe. Major geographical zones include the West Siberian Plain and the Central Siberian Plateau.

Eastern and central Sakha comprises numerous north-south mountain ranges of various ages. These mountains extend up to almost 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), but above a few hundred metres they are almost completely devoid of vegetation. The Verkhoyansk Range was extensively glaciated in the Pleistocene, but the climate was too dry for glaciation to extend to low elevations. At these low elevations are numerous valleys, many of them deep and covered with larch forest, except in the extreme north where the tundra dominates. Soils are mainly turbels (a type of gelisol). The active layer tends to be less than one metre deep, except near rivers.

The highest point in Siberia is the active volcano Klyuchevskaya Sopka, on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Its peak is at 4,750 metres (15,580 ft).

Mountain ranges

Lakes and rivers

Grasslands

- Ukok Plateau — part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site[24]

Geology

The West Siberian Plain consists mostly of Cenozoic alluvial deposits and is somewhat flat. Many deposits on this plain result from ice dams which produced a large glacial lake. This mid- to late-Pleistocene lake blocked the northward flow of the Ob and Yenisei rivers, resulting in a redirection southwest into the Caspian and Aral seas via the Turgai Valley.[25] The area is very swampy, and soils are mostly peaty histosols and, in the treeless northern part, histels. In the south of the plain, where permafrost is largely absent, rich grasslands that are an extension of the Kazakh Steppe formed the original vegetation, most of which is not visible anymore.[why?]

The Central Siberian Plateau is an ancient craton (sometimes named Angaraland) that formed an independent continent before the Permian (see the Siberian continent). It is exceptionally rich in minerals, containing large deposits of gold, diamonds, and ores of manganese, lead, zinc, nickel, cobalt and molybdenum. Much of the area includes the Siberian Traps—a large igneous province. This massive eruptive period was approximately coincident with the Permian–Triassic extinction event. The volcanic event is said to be the largest known volcanic eruption in Earth's history. Only the extreme northwest was glaciated during the Quaternary, but almost all is under exceptionally deep permafrost, and the only tree that can thrive, despite the warm summers, is the deciduous Siberian Larch (Larix sibirica) with its very shallow roots. Outside the extreme northwest, the taiga is dominant, covering a significant fraction of the entirety of Siberia.[26] Soils here are mainly turbels, giving way to spodosols where the active layer becomes thicker and the ice content lower.

The Lena-Tunguska petroleum province includes the Central Siberian platform (some authors refer to it as the Eastern Siberian platform), bounded on the northeast and east by the Late Carboniferous through Jurassic Verkhoyansk foldbelt, on the northwest by the Paleozoic Taymr foldbelt, and on the southeast, south and southwest by the Middle Silurian to Middle Devonian Baykalian foldbelt.[27]: 228 A regional geologic reconnaissance study begun in 1932, followed by surface and subsurface mapping, revealed the Markova-Angara Arch (anticline). This led to the discovery of the Markovo Oil Field in 1962 with the Markovo 1 well, which produced from the Early Cambrian Osa Horizon bar-sandstone at a depth of 2,156 metres (7,073 ft).[27]: 243 The Sredne-Botuobin Gas Field was discovered in 1970, producing from the Osa and the Proterozoic Parfenovo Horizon.[27]: 244 The Yaraktin Oil Field was discovered in 1971, producing from the Vendian Yaraktin Horizon at depths of up to 1,750 metres (5,740 ft), which lies below Permian to Lower Jurassic basalt traps.[27]: 244

Climate

|

|

polar desert

tundra

alpine tundra

taiga

montane forest |

| Vegetation in Siberia is mostly taiga, with a tundra belt on the northern fringe, and a temperate forest zone in the south. |

The climate of Siberia varies dramatically, but all of it basically has short summers and long and extremely cold winters. On the north coast, north of the Arctic Circle, there is a very short (about one-month-long) summer.

Almost all the population lives in the south, along the Trans-Siberian Railway. The climate in this southernmost part is Humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) with cold winters but fairly warm summers lasting at least four months. The annual average is about 0.5 °C (32.9 °F). January averages about −20 °C (−4 °F) and July about +19 °C (66 °F) while daytime temperatures in summer typically are above 20 °C (68 °F).[28][29] With a reliable growing season, an abundance of sunshine and exceedingly fertile chernozem soils, southern Siberia is good enough for profitable agriculture, as was proven in the early 20th century.

By far the most commonly occurring climate in Siberia is continental subarctic (Koppen Dfc or Dwc), with the annual average temperature about −5 °C (23 °F) and an average for January of −25 °C (−13 °F) and an average for July of +17 °C (63 °F),[30] although this varies considerably, with a July average about 10 °C (50 °F) in the taiga–tundra ecotone. The Business oriented website and blog Business Insider lists Verkhoyansk and Oymyakon, in Siberia's Sakha Republic, as being in competition for the title of the Northern Hemisphere's Pole of Cold. Oymyakon is a village which recorded a temperature of −67.7 °C (−89.9 °F) on 6 February 1933. Verkhoyansk, a town further north and further inland, recorded a temperature of −69.8 °C (−93.6 °F) for 3 consecutive nights: 5, 6 and 7 February 1933. Each town is alternately considered the Northern Hemisphere's Pole of Cold, meaning the coldest inhabited point in the Northern hemisphere. Each town also frequently reaches 86 °F (30 °C) in the summer, giving them, and much of the rest of Russian Siberia, the world's greatest temperature variation between summer's highs and winter's lows, often being well over 170–180+ °F (94–100+ °C) between the seasons.[31][failed verification]

Southwesterly winds bring warm air from Central Asia and the Middle East. The climate in West Siberia (Omsk, Novosibirsk) is several degrees warmer than in the East (Irkutsk, Chita) where in the north an extreme winter subarctic climate (Köppen Dfd or Dwd) prevails. But summer temperatures in other regions can reach +38 °C (100 °F). In general, Sakha is the coldest Siberian region, and the basin of the Yana River has the lowest temperatures of all, with permafrost reaching 1,493 metres (4,898 ft). Nevertheless, as far as Imperial Russian plans of settlement were concerned, cold was never viewed as an impediment. In the winter, southern Siberia sits near the center of the semi-permanent Siberian High, so winds are usually light in the winter.

Precipitation in Siberia is generally low, exceeding 500 millimetres (20 in) only in Kamchatka where moist winds flow from the Sea of Okhotsk onto high mountains – producing the region's only major glaciers, though volcanic eruptions and low summer temperatures allow limited forests to grow. Precipitation is high also in most of Primorye in the extreme south where monsoonal influences can produce quite heavy summer rainfall.

| Climate data for Novosibirsk, Siberia's largest city | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −12.2 (10.0) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −16.2 (2.8) |

−14.7 (5.5) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −20.1 (−4.2) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19 (0.7) |

14 (0.6) |

15 (0.6) |

24 (0.9) |

36 (1.4) |

58 (2.3) |

72 (2.8) |

66 (2.6) |

44 (1.7) |

38 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

24 (0.9) |

442 (17.4) |

| Source: [32] | |||||||||||||

Researchers, including Sergei Kirpotin at Tomsk State University and Judith Marquand at Oxford University, warn that Western Siberia has begun to thaw as a result of global warming. The frozen peat bogs in this region may hold billions of tons of methane gas, which may be released into the atmosphere. Methane is a greenhouse gas 22 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.[33] In 2008, a research expedition for the American Geophysical Union detected levels of methane up to 100 times above normal in the atmosphere above the Siberian Arctic, likely the result of methane clathrates being released through holes in a frozen 'lid' of seabed permafrost, around the outfall of the Lena River and the area between the Laptev Sea and East Siberian Sea.[34][35]

Fauna

Order Artiodactyla

Order Carnivora

Family Felidae

Family Ursidae

Flora

Politics

Borders and administrative division

The term "Siberia" has a long history. Its meaning has gradually changed during ages. Historically, Siberia was defined as the whole part of Russia to the east of Ural Mountains, including the Russian Far East. According to this definition, Siberia extended eastward from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific coast, and southward from the Arctic Ocean to the border of Russian Central Asia and the national borders of both Mongolia and China.[44]

Soviet-era sources (Great Soviet Encyclopedia and others)[45] and modern Russian ones[46] usually define Siberia as a region extending eastward from the Ural Mountains to the watershed between Pacific and Arctic drainage basins, and southward from the Arctic Ocean to the hills of north-central Kazakhstan and the national borders of both Mongolia and China. By this definition, Siberia includes the federal subjects of the Siberian Federal District, and some of the Ural Federal District, as well as Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, which is a part of the Far Eastern Federal District. Geographically, this definition includes subdivisions of several other subjects of Urals and Far Eastern federal districts, but they are not included administratively. This definition excludes Sverdlovsk Oblast and Chelyabinsk Oblast, both of which are included in some wider definitions of Siberia.

Other sources may use either a somewhat wider definition that states the Pacific coast, not the watershed, is the eastern boundary (thus including the whole Russian Far East)[47] or a somewhat narrower one that limits Siberia to the Siberian Federal District (thus excluding all subjects of other districts).[48] In Russian, the word for Siberia is used as a substitute for the name of the federal district by those who live in the district itself and less commonly used to denote the federal district by people residing outside of it.

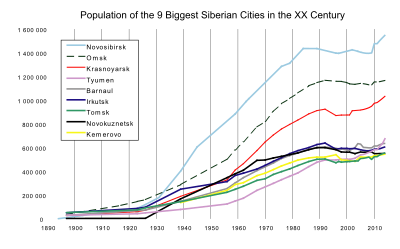

Major cities

The most populous city of Siberia, as well as the third most populous city of Russia, is the city of Novosibirsk. Other major cities include:

Wider definitions of Siberia also include:

- Chelyabinsk

- Khabarovsk

- Vladivostok

- Yekaterinburg - Some sources such as Encyclopædia Britannica include this city as it lies in the Ural Mountains. Inhabitants have distanced themselves though saying that there is a difference between Siberian and Urals culture.[49]

Economy

Siberia is extraordinarily rich in minerals, containing ores of almost all economically valuable metals. It has some of the world's largest deposits of nickel, gold, lead, coal, molybdenum, gypsum, diamonds, diopside, silver and zinc, as well as extensive unexploited resources of oil and natural gas.[50] Around 70% of Russia's developed oil fields are in the Khanty-Mansiysk region.[51] Russia contains about 40% of the world's known resources of nickel at the Norilsk deposit in Siberia. Norilsk Nickel is the world's biggest nickel and palladium producer.[52]

Siberian agriculture is severely restricted by the short growing season of most of the region. However, in the southwest where soils are exceedingly fertile black earths and the climate is a little more moderate, there is extensive cropping of wheat, barley, rye and potatoes, along with the grazing of large numbers of sheep and cattle. Elsewhere food production, owing to the poor fertility of the podzolic soils and the extremely short growing seasons, is restricted to the herding of reindeer in the tundra—which has been practiced by natives for over 10,000 years.[citation needed] Siberia has the world's largest forests. Timber remains an important source of revenue, even though many forests in the east have been logged much more rapidly than they are able to recover. The Sea of Okhotsk is one of the two or three richest fisheries in the world owing to its cold currents and very large tidal ranges, and thus Siberia produces over 10% of the world's annual fish catch, although fishing has declined somewhat since the collapse of the USSR.[53]

Sport

Professional football teams include FC Tom Tomsk, FC Sibir Novosibirsk and FK Yenisey Krasnoyarsk.

The Yenisey Krasnoyarsk basketball team has played in the VTB United League since 2011–12.

Russia's third most popular sport, bandy,[54] is important in Siberia. In the 2015–16 Russian Bandy Super League season Yenisey from Krasnoyarsk became champions for the third year in a row by beating Baykal-Energiya from Irkutsk in the final.[55][56] Two or three more teams (depending on the definition of Siberia) play in the Super League, the 2016-17 champions SKA-Neftyanik from Khabarovsk as well as Kuzbass from Kemerovo and Sibselmash from Novosibirsk. In 2007 Kemerovo got Russia's first indoor arena specifically built for bandy.[57] Now Khabarovsk has the world's biggest indoor arena specifically built for bandy, Arena Yerofey.[58] It will be the venue for Division A of the 2018 World Championship.

The 2019 Winter Universiade will be hosted by Krasnoyarsk.

Demographics

According to the Russian Census of 2010, the Siberian and Far Eastern Federal Districts, located entirely east of the Ural Mountains, together have a population of about 25.6 million. Tyumen and Kurgan Oblasts, which are geographically in Siberia but administratively part of the Urals Federal District, together have a population of about 4.3 million. Thus, the whole region of Asian Russia (or Siberia in the broadest usage of the term) is home to approximately 30 million people.[59] It has a population density of about three people per square kilometre.

All Siberians are Russian citizens, and of these Russian citizens of Siberia, most are Slavic-origin Russians and russified Ukrainians.[60] The remaining Russian citizens of Siberia consists of other groups of non-indigenous ethnic origins and those of indigenous Siberian origin.

Among the largest non-Slavic group of Russian citizens of Siberia are the approximately 400,000 ethnic Volga Germans.[61] The original indigenous groups of Siberia, including Mongol and Turkic groups such as Buryats, Tuvinians, Yakuts, and Siberian Tatars still mostly reside in Siberia, though they are minorities outnumbered by all other non-indigenous Siberians. Indeed, Slavic-origin Russians by themselves outnumber all of the indigenous peoples combined, both in Siberia as a whole and its cities, except in the Republic of Tuva.

Slavic-origin Russians make up the majority in the Buryat, Sakha, and Altai Republics, outnumbering the indigenous Buryats, Sakha, and Altai. The Buryat make up only 25% of their own republic, and the Sakha and Altai each are only one-third, and the Chukchi, Evenk, Khanti, Mansi, and Nenets are outnumbered by non-indigenous peoples by 90% of the population.[62]

According to the 2002 census there are 500,000 Tatars in Siberia, but of these, 300,000 are Volga Tatars who also settled in Siberia during periods of colonization and are thus also non-indigenous Siberians, in contrast to the 200,000 Siberian Tatars which are indigenous to Siberia.[63]

Of the indigenous Siberians, the Buryats, numbering approximately 500,000, are the most numerous group in Siberia, and they are mainly concentrated in their homeland, the Buryat Republic.[64] According to the 2002 census there were 443,852 indigenous Yakuts.[65] Other ethnic groups indigenous to Siberia include Kets, Evenks, Chukchis, Koryaks, Yupiks, and Yukaghirs.

About seventy percent of Siberia's people live in cities, mainly in apartments. Many people also live in rural areas, in simple, spacious, log houses. Novosibirsk is the largest city in Siberia, with a population of about 1.5 million. Tobolsk, Tomsk, Tyumen, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, and Omsk are the older, historical centers.

Religion

There are a variety of beliefs throughout Siberia,[66][need quotation to verify] including Orthodox Christianity, other denominations of Christianity, Tibetan Buddhism and Islam.[67] An estimated 70,000 Jews live in Siberia,[68] some in the Jewish Autonomous Region.[69] The predominant religious group is the Russian Orthodox Church.

Tradition regards Siberia the archetypal home of shamanism, and polytheism is popular.[70] These native sacred practices are considered by the tribes to be very ancient. There are records of Siberian tribal healing practices dating back to the 13th century.[71] The vast territory of Siberia has many different local traditions of gods. These include: Ak Ana, Anapel, Bugady Musun, Kara Khan, Khaltesh-Anki, Kini'je, Ku'urkil, Nga, Nu'tenut, Numi-Torem, Numi-Turum, Pon, Pugu, Todote, Toko'yoto, Tomam, Xaya Iccita, Zonget. Places with sacred areas include Olkhon, an island in Lake Baikal.

Transport

Many cities in northern Siberia, such as Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, cannot be reached by road, as there are virtually none connecting from other major cities in Russia or Asia. The best way to tour Siberia is through the Trans-Siberian Railway. The Trans-Siberian Railway operates from Moscow in the west to Vladivostok in the east. Cities that are located far from the railway are best reached by air or by the separate Baikal-Amur-Railway (BAM).

Culture

Cuisine

Stroganina is a raw fish dish of the indigenous people of northern Arctic Siberia made from raw, thin, long-sliced frozen fish.[72] It is a popular dish with native Siberians.[73]

See also

References

- ^ "Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)". Encycl.yandex.ru. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Euan Ferguson. "Trans-Siberian for softies". the Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). The Manchus. Peoples of Asia. Vol. 14 (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 213. ISBN 0-631-23591-4. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Czaplicka, M.C. (1915). Aboriginal Siberia.

- ^ Baikaloff, Anatole (December 1950). "Notes on the origin of the name "Siberia"". Slavonic and East European Review. 29 (72): 288.

- ^ "Meet this extinct cave lion, at least 10,000 years old – world exclusive". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ ""Yellowstone's Super Sister"". Archived from the original on 14 March 2005. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). Discovery Channel. - ^ Benton, M. J. (2005). When Life Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass Extinction of All Time. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28573-2.

- ^ "DNA identifies new ancient human dubbed 'X-woman'," BBC News. 25 March 2010.

- ^ Pakendorf, B.; Novgorodov, I. N.; Osakovskij, V. L.; Danilova, A. B. P.; Protod'Jakonov, A. P.; Stoneking, M. (2006). "Investigating the effects of prehistoric migrations in Siberia: Genetic variation and the origins of Yakuts". Human Genetics. 120 (3): 334–353. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0213-2. PMID 16845541.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Richards, 2003 p. 538.

- ^ Asia ex magna Orbis terrae descriptione Gerardi Mercatoris desumpta, studio & industria G.M. Iunioris

- ^ Sean C. Goodlett. "Russia's Expansionist Policies I. The Conquest of Siberia". Falcon.fsc.edu. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ https://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21705305-prison-without-roof?fsrc=scn/tw/te/pe/ed/prisonwithoutaroof https://twitter.com/TheEconomist/status/768263225708257284

- ^ "Review: The Great Siberian Migration: Government and Peasant in Resettlement from Emancipation to the First World War". Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ The Russian Far East: A History. John J. Stephan (1996). Stanford University Press. p.62. ISBN 0-8047-2701-5

- ^ Fiona Hill, Russia — Coming In From the Cold? Archived 24 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Globalist, 23 February 2004

- ^ The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin's Special Settlements. Lynne Viola (2007). Oxford University Press US. p.3. ISBN 0-19-518769-5

- ^ Robert Conquest in "Victims of Stalinism: A Comment," Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 49, No. 7 (Nov. 1997), pp. 1317–1319 states: "We are all inclined to accept the Zemskov totals (even if not as complete) with their 14 million intake to Gulag 'camps' alone, to which must be added 4–5 million going to Gulag 'colonies', to say nothing of the 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labour settlements'. However taken, these are surely 'high' figures."

- ^ Zemskov, "Gulag," Sociologičeskije issledovanija, 1991, No. 6, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Stéphane Courtois, Mark Kramer. Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression. Harvard University Press, 1999. p. 206. ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ Courtois and Kramer (1999), Livre noir du Communisme, p.239.

- ^ "Gulag: a History of the Soviet Camps". Arlindo-correia.org. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Altai: Saving the Pearl of Siberia". Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ Lioubimtseva E.U., Gorshkov S.P. & Adams J.M.; A Giant Siberian Lake During the Last Glacial: Evidence and Implications; Oak Ridge National Laboratory Archived 13 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2011. Taiga. eds. M.McGinley & C.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ^ a b c d Meyerhof, A. A., 1980, "Geology and Petroleum Fields in Proterozoic and Lower Cambrian Strata, Lena-Tunguska Petroleum Province, Eastern Siberia, USSR", in Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade: 1968–1978, AAPG Memoir 30, Halbouty, M. T., editor, Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, ISBN 0891813063

- ^ "Novosibirsk climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ "Omsk climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ "Kazachengoye climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Business Insider, February 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/verkhoyansk-russia-most-miserable-place-2014-2

- ^ Гидрометцентр России (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ian Sample, "Warming hits 'tipping point'". The Guardian, 11 August 2005

- ^ Connor, Steve (23 September 2008). "Exclusive: The methane time bomb". The Independent. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ N. Shakhova, I. Semiletov, A. Salyuk, D. Kosmach, and N. Bel'cheva (2007), Methane release on the Arctic East Siberian shelf, Geophysical Research Abstracts, 9, 01071

- ^ Valerius Geist (January 1998). Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour, and Ecology. Stackpole Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8117-0496-0. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of vulnerable.

- ^ Uphyrkina, O.; Miquelle, D.; Quigley, H.; Driscoll, C.; O’Brien, S. J. (2002). "Conservation Genetics of the Far Eastern Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis)" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. 93 (5): 303–11. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.5.303. PMID 12547918. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ Farjon, A. (2013). "Pinus pumila". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. IUCN: e.T42405A2977712. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42405A2977712.en. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ A. Farjon (2013). "Picea obovata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. IUCN: e.T42331A2973177. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42331A2973177.en. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Малый энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона (The Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, in Russian)

- ^ Сибирь—Большая советская энциклопедия (The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, in Russian)

- ^ Сибирь- Словарь современных географических названий (in Russian)

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Siberia-Britannica online encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ ""Siberia"". Archived from the original on 24 August 2000. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition - ^ David Filipov (5 January 2017). "This Russian city says: 'Don't call us Siberia'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Statistics on the Development of Gas Fields in Western Siberia, Daily Questions on Energy and Economy

- ^ Schlindwein, Simone (26 August 2008). "The City Built on Oil: EU-Russia Summit Visits Siberia's Boomtown". Spiegel. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Norilsk raises 2010 nickel output forecast". Reuters. 29 January 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "FAO National Aquaculture Sector Overview (NASO)". 16 January 2005. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Google Translate". Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Google Translate". Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ https://i.ytimg.com/vi/_Y0lhvnE7pU/hqdefault.jpg

- ^ "Информация о стадионе "КЛМ стадиона «Химик", Кемерово – Реестр – Федерация хоккея с мячом России". rusbandy.ru. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Информация о стадионе "Арена «Ерофей", Хабаровск – Реестр – Федерация хоккея с мячом России". rusbandy.ru. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Census 2010 official results (Russian) Archived 23 May 2013 at WebCite"

- ^ "Ukrainians in Russia's Far East try to maintain community life". The Ukrainian Weekly. May 4, 2003.

- ^ "Siberian Germans". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Batalden 1997, p. 37.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2002. Retrieved 21 February 2003.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Russian Federation: Buryats.

- ^ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Russian Federation: Yakuts.

- ^ "Russian Embassy website — Religion in Russia". Archived from the original on 26 September 2000. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Arnold, Thomas Walker (1896). The Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 206–207. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

Of the spread of Islam among the Tatars of Siberia, we have a few particulars. It was not until the latter half of the sixteenth century that it gained a footing in this country, but even before this period Muhammadan missionaries had from time to time made their way into Siberia with the hope of winning the heathen population over to the acceptance of their faith, but the majority of them met with a martyr's death. When Siberia came under Muhammadan rule, in the reign of Kuchum Khan, the graves of seven of these missionaries were discovered [...]. [...] Kuchum Khan [...] made every effort for the conversion of his subjects, and sent to Bukhara asking for missionaries to assist him in this pious undertaking.

- ^ "Planting Jewish roots in Siberia". Fjc.ru. 24 May 2004. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Why some Jews would rather live in Siberia than Israel", The Christian Science Monitor. 7 June 2010

- ^ Hoppál 2005:13

- ^ "Secrets of Siberian Shamanism | New Dawn : The World's Most Unusual Magazine". www.newdawnmagazine.com. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Rasputin, V.; Winchell, M.; Mikkelson, G. (1997). Siberia, Siberia. Northwestern University Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-0-8101-1575-0.

- ^ Motarjemi, Yasmine; Moy, Gerald; Todd, E. C. D. (2013). Encyclopedia of Food Safety. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, Academic Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-12-378613-5.

Bibliography

- Batalden, Stephen K. (1997). The Newly Independent States of Eurasia: Handbook of Former Soviet Republics. Contributor Sandra L. Batalden (revised ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0897749405. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765952. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765960. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, Jeremy (2008). War and the World: Military Power and the Fate of Continents, 1450–2000. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300147694. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Abby Schrader and Willard Sunderland (eds), Peopling the Russian Periphery: Borderland Colonization in Eurasian history (London, Routledge, 2007).

- Etkind, Alexander (2013). Internal Colonization: Russia's Imperial Experience. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0745673546. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477719. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James Forsyth, A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony, 1581–1990 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- Jack, Zachary Michael, ed. (2008). Inside the Ropes: Sportswriters Get Their Game On. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803219075. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Steven G. Marks, Road to Power: The Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Colonization of Asian Russia, 1850–1917 (London, I.B. Tauris, 1991).

- Mote, Victor L. (1998). Siberia: Worlds Apart. Westview series on the post-Soviet republics (illustrated ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 0813312981. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Igor V. Naumov, The History of Siberia. Edited by David Collins (London, Routledge, 2009) (Routledge Studies in the History of Russia and Eastern Europe).

- Stephan, John J. (1996). The Russian Far East: A History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804727015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pesterev, V. (2015). Siberian frontier: the territory of fear. Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wood, Alan (2011). Russia's Frozen Frontier: A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East 1581 – 1991 (illustrated ed.). A&C Black. ISBN 034097124X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Alan Wood (ed.), The History of Siberia: From Russian Conquest to Revolution (London, Routledge, 1991).

- Condé Nast's Traveler, Volume 36. Condé Nast Publications. 2001. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yearbook. Contributor International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. 1992. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: others (link)