Bangladesh Liberation War

| Bangladesh Liberation War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Paramilitary Forces : | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

File:Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami logo.png Ghulam Azam (Shanti committee) File:Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami logo.png Motiur Rahman Nizami (Al-Badr) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Bangladesh Forces: 175,000[2][3] India: 250,000[2] |

Pakistan Armed Forces: ~ 365,000 (90,000 in East Pakistan)[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Bangladesh Forces: 30,000 India: 1,426 KIA 3,611 Wounded (Official) 1,525 KIA 4,061 Wounded[5] |

Pakistan (56,694 Armed Forces 12,192 Paramilitary rest civilians)[5][7] | ||||||||

| Civilian death toll: Estimated between 300,000[8] and 3,000,000[9] | |||||||||

The Bangladesh Liberation War(i) (Bengali: মুক্তিযুদ্ধ Muktijuddho) was a revolutionary war of independence in 1971 that established the sovereign nation of Bangladesh.[10] The war pitted East Pakistan and India against West Pakistan, and lasted over a duration of nine months. It witnessed large-scale atrocities, the exodus of 10 million refugees and the displacement of 30 million people.[11]

The war broke out on 26 March 1971, when the Pakistani Army launched a military operation called Operation Searchlight against Bengali civilians, students, intelligentsia and armed personnel, who were demanding that the Pakistani military junta accept the results of the 1970 first democratic elections of Pakistan, which were won by an eastern party, or to allow separation between East and West Pakistan. Bengali politicians and army officers announced the declaration of Bangladesh's independence in response to Operation Searchlight. Bengali military, paramilitary and civilians formed the Mukti Bahini (Bengali: মুক্তি বাহিনী "Liberation Army"), which engaged in guerrilla warfare against Pakistani forces. The Pakistan Army, in collusion with religious extremist[12][13] militias (the Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams), engaged in the systematic genocide and atrocities of Bengali civilians, particularly nationalists, intellectuals, youth and religious minorities.[14][15][16][17][18] Neighbouring India provided economic, military and diplomatic support to Bengali nationalists, and the Bangladesh government-in-exile was set up in Calcutta.

India entered the war on 3 December 1971, after Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on northern India. Overwhelmed by two war fronts, Pakistani defences soon collapsed. On 16 December, the Allied Forces of Bangladesh and India defeated Pakistan in the east. The subsequent surrender resulted in the largest number of prisoners-of-war since World War II.

Nomenclature

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (December 2013) |

.

Encyclopaedia of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh mentions this war as Bangladesh Liberation war.[19] This war is known in Bangla as Muktijuddho or Shawdhinota Juddho.[20]

Background

In August 1947, the official birth of two states Pakistan and India;[21] gave a permanent home for Hindus and Muslims from the departure of the British. The Dominion of Pakistan comprised two geographically and culturally separate areas to the east and the west with India in between.[22] The western zone was popularly (and for a period of time, also officially) termed West Pakistan and the eastern zone (modern-day Bangladesh) was initially termed East Bengal and later, East Pakistan. Although the population of the two zones was close to equal, political power was concentrated in West Pakistan and it was widely perceived that East Pakistan was being exploited economically, leading to many grievances. Administration of two discontinuous territories was also seen as a challenge.[23] On 25 March 1971, after an election won by an East Pakistani political party (the Awami League) was ignored by the ruling (West Pakistani) establishment, rising political discontent and cultural nationalism in East Pakistan was met by brutal[24] suppressive force from the ruling elite of the West Pakistan establishment,[25] in what came to be termed Operation Searchlight.[26]

The violent crackdown by West Pakistan forces[27] led to Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declaring East Pakistan's independence as the state of Bangladesh on 26 March 1971.[28] Pakistani President Agha Mohammed Yahya ordered the Pakistani military to restore the Pakistani government's authority, beginning the civil war.[28] The war led to a sea of refugees (estimated at the time to be about 10 million)[29][30] flooding into the eastern provinces of India.[29] Facing a mounting humanitarian and economic crisis, India started actively aiding and organising the Bangladeshi resistance army known as the Mukti Bahini.

Language controversy

In 1948, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan's first Governor-General, declared in Dhaka (then usually spelled Dacca in English) that "Urdu, and only Urdu" would be the common language for all of Pakistan.[31] This proved highly controversial, since Urdu was a language that was only spoken in the West by Muhajirs and in the East by Biharis, although the Urdu language had been promoted as the lingua franca of Indian Muslims by political and religious leaders such as Sir Khwaja Salimullah, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Nawab Viqar-ul-Mulk and Maulvi Abdul Haq. The language was considered a vital element of the Islamic culture for Indian Muslims; Hindi and the Devanagari script were seen as fundamentals of Hindu culture. The majority groups in the western wing of the Dominion of Pakistan (provinces, states and tribal areas merged in 1956 as West Pakistan) spoke Punjabi, while the Bengali language was spoken by the vast majority of East Bengalis (from 1956, East Pakistan).[32] The language controversy eventually reached a point where East Bengal revolted while the other part of Pakistan remained calm even though Punjabi was spoken by the majority of the population of the western wing. Several students and civilians lost their lives in a police crackdown on 21 February 1952.[32] The day is revered in Bangladesh and in West Bengal as the Language Martyrs' Day. Later, in memory of the 1952 deaths, UNESCO declared 21 February as the International Mother Language Day in 1999.[33]

In the western wing, the movement was seen as a sectional uprising against Pakistani national interests[34] and the founding ideology of Pakistan, the Two-Nation Theory.[35] West Pakistani politicians considered Urdu a product of Indian Islamic culture,[36] as Ayub Khan said, as late as 1967, "East Pakistanis... still are under considerable Hindu culture and influence."[36] However, the deaths led to bitter feelings among East Bengalis, and they were a major factor in the push for independence in 1971.[35][36]

Disparities

Although East Pakistan had a larger population, West Pakistan dominated the divided country politically and received more money from the common budget.

| Year | Spending on West Pakistan (in millions of Pakistani rupees) | Spending on East Pakistan (in millions of Pakistani rupees) | Amount spent on East as percentage of West |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–55 | 11,290 | 5,240 | 46.4 |

| 1955–60 | 16,550 | 5,240 | 31.7 |

| 1960–65 | 33,550 | 14,040 | 41.8 |

| 1965–70 | 51,950 | 21,410 | 41.2 |

| Total | 113,340 | 45,930 | 40.5 |

| Source: Reports of the Advisory Panels for the Fourth Five Year Plan 1970–75, Vol. I, published by the planning commission of Pakistan. | |||

Bengalis were under-represented in the Pakistan military. Officers of Bengali origin in the different wings of the armed forces made up just 5% of overall force by 1965; of these, only a few were in command positions, with the majority in technical or administrative posts.[37] West Pakistanis believed that Bengalis were not "martially inclined" unlike Pashtuns and Punjabis; the "Martial Races" notion was dismissed as ridiculous and humiliating by Bengalis.[37] Moreover, despite huge defence spending, East Pakistan received none of the benefits, such as contracts, purchasing and military support jobs. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 over Kashmir also highlighted the sense of military insecurity among Bengalis, as only an under-strength infantry division and 15 combat aircraft without tank support were in East Pakistan to thwart any Indian retaliations during the conflict.[38][39]

Political differences

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population,[40] political power remained in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "One Unit" scheme, where all of West Pakistan was considered one province. This was solely to counterbalance the East wing's votes.

After the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan's first prime minister, in 1951, political power began to devolve to the President of Pakistan, and eventually, the military. The nominal elected chief executive, the Prime Minister, was frequently sacked by the establishment, acting through the President.

The East Pakistanis observed that the West Pakistani establishment would swiftly depose any East Pakistanis elected Prime Minister of Pakistan, such as Khawaja Nazimuddin, Muhammad Ali Bogra, or Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Their suspicions were further influenced by the military dictatorships of Ayub Khan (27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969) and Yahya Khan (25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971), both West Pakistanis. The situation reached a climax in 1970, when the Awami League, the largest East Pakistani political party, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a landslide victory in the national elections. The party won 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan, and thus a majority of the 313 seats in the National Assembly. This gave the Awami League the constitutional right to form a government. However, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (a Sindhi and former Foreign Minister), the leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, refused to allow Rahman to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan.[41] Instead, he proposed the idea of having two Prime Ministers, one for each wing. The proposal elicited outrage in the east wing, already chafing under the other constitutional innovation, the "one unit scheme". Bhutto also refused to accept Rahman's Six Points. On 3 March 1971, the two leaders of the two wings along with the President General Yahya Khan met in Dhaka to decide the fate of the country. After their discussions yielded no satisfactory results, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called for a nationwide strike. Bhutto feared a civil war, therefore, he sent his trusted companion, Dr. Mubashir Hassan.[41] A message was convened and Mujib decided to meet Bhutto.[41] Upon his arrival, Mujib met with Bhutto and both agreed to form a coalition government with Mujib as Premier and Bhutto as President.[41] However, the military was unaware of these developments, and Bhutto increased his pressure on Mujib to reach a decision.[41]

On 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (soon to be the prime minister) delivered a speech at the Racecourse Ground (now called the Suhrawardy Udyan). In this speech he mentioned a further four-point condition to consider at the National Assembly Meeting on 25 March:

- The immediate lifting of martial law.

- Immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks.

- An inquiry into the loss of life.

- Immediate transfer of power to the elected representative of the people before the assembly meeting 25 March.

He urged his people to turn every house into a fort of resistance. He closed his speech saying, "Our struggle is for our freedom. Our struggle is for our independence." This speech is considered the main event that inspired the nation to fight for its independence. General Tikka Khan was flown into Dhaka to become Governor of East Bengal. East-Pakistani judges, including Justice Siddique, refused to swear him in.

Between 10 and 13 March, Pakistan International Airlines cancelled all their international routes to urgently fly "government passengers" to Dhaka. These "government passengers" were almost all Pakistani soldiers in civilian dress. MV Swat, a ship of the Pakistan Navy carrying ammunition and soldiers, was harboured in Chittagong Port, but the Bengali workers and sailors at the port refused to unload the ship. A unit of East Pakistan Rifles refused to obey commands to fire on the Bengali demonstrators, beginning a mutiny among the Bengali soldiers.

Response to the 1970 cyclone

The 1970 Bhola cyclone made landfall on the East Pakistan coastline during the evening of 12 November, around the same time as a local high tide,[42] killing an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people. Though the exact death toll is not known, it is considered the deadliest tropical cyclone on record.[43] A week after the landfall, President Khan conceded that his government had made "slips" and "mistakes" in its handling of the relief efforts due to a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the disaster.[44]

A statement released by eleven political leaders in East Pakistan ten days after the cyclone hit charged the government with "gross neglect, callous and utter indifference". They also accused the president of playing down the magnitude of the problem in news coverage.[45] On 19 November, students held a march in Dhaka protesting the slowness of the government's response.[46] Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani addressed a rally of 50,000 people on 24 November, where he accused the president of inefficiency and demanded his resignation.

As the conflict between East and West Pakistan developed in March, the Dhaka offices of the two government organisations directly involved in relief efforts were closed for at least two weeks, first by a general strike and then by a ban on government work in East Pakistan by the Awami League. With this increase in tension, foreign personnel were evacuated over fears of violence. Relief work continued in the field, but long-term planning was curtailed.[47] This conflict widened into the Bangladesh Liberation War in December and concluded with the creation of Bangladesh. This is one of the first times that a natural event helped to trigger a civil war.[48]

Operation Searchlight

A planned military pacification carried out by the Pakistan Army – codenamed Operation Searchlight – started on 25 March to curb the Bengali nationalist movement[49] by taking control of the major cities on 26 March, and then eliminating all opposition, political or military,[50] within one month. Before the beginning of the operation, all foreign journalists were systematically deported from East Pakistan.[51]

The main phase of Operation Searchlight ended with the fall of the last major town in Bengali hands in mid-May. The operation also began the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities. These systematic killings served only to enrage the Bengalis, which ultimately resulted in the secession of East Pakistan later in the same year. The international media and reference books in English have published casualty figures which vary greatly, from 5,000–35,000 in Dhaka, and 200,000–3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole,[52] and the atrocities have been referred to as acts of genocide.[53][54]

According to the Asia Times,[55]

At a meeting of the military top brass, Yahya Khan declared: "Kill 3 million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands." Accordingly, on the night of 25 March, the Pakistani Army launched Operation Searchlight to "crush" Bengali resistance in which Bengali members of military services were disarmed and killed, students and the intelligentsia systematically liquidated and able-bodied Bengali males just picked up and gunned down.

Although the violence focused on the provincial capital, Dhaka, it also affected all parts of East Pakistan. Residential halls of the University of Dhaka were particularly targeted. The only Hindu residential hall – the Jagannath Hall – was destroyed by the Pakistani armed forces, and an estimated 600 to 700 of its residents were murdered. The Pakistani army denied any cold blooded killings at the university, though the Hamood-ur-Rehman commission in Pakistan concluded that overwhelming force was used at the university. This fact and the massacre at Jagannath Hall and nearby student dormitories of Dhaka University are corroborated by a videotape secretly filmed by Prof. Nurullah of the East Pakistan Engineering University, whose residence was directly opposite the student dormitories.[56]

The scale of the atrocities was first made clear in the West when Anthony Mascarenhas, a Pakistani journalist who had been sent to the province by the military authorities to write a story favourable to Pakistan's actions, instead fled to the United Kingdom and, on 13 June 1971, published an article in the Sunday Times describing the systematic killings by the military. The BBC wrote: "There is little doubt that Mascarenhas' reportage played its part in ending the war. It helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and encouraged India to play a decisive role", with Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi herself stating that Mascarenhas' article has led her "to prepare the ground for India's armed intervention".[57]

Hindu areas suffered particularly heavy blows. By midnight, Dhaka was burning, especially the Hindu dominated eastern part of the city. Time magazine reported on 2 August 1971, "The Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Pakistani military hatred."[58]

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested by the Pakistani Army. Yahya Khan appointed Brigadier (later General) Rahimuddin Khan to preside over a special tribunal prosecuting Mujib with multiple charges. The tribunal's sentence was never made public, but Yahya caused the verdict to be held in abeyance in any case. Other Awami League leaders were arrested as well, while a few fled Dhaka to avoid arrest. The Awami League was banned by General Yahya Khan.[59]

Declaration of independence

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971, proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these outrages, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Today Bangladesh is a sovereign and independent country. On Thursday night, West Pakistani armed forces suddenly attacked the police barracks at Razarbagh and the EPR headquarters at Pilkhana in Dhaka. Many innocent and unarmed have been killed in Dhaka city and other places of Bangladesh. Violent clashes between E.P.R. and Police on the one hand and the armed forces of Pakistan on the other, are going on. The Bengalis are fighting the enemy with great courage for an independent Bangladesh. May Allah aid us in our fight for freedom. Joy Bangla [May Bangladesh be victorious].

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Mujib was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 am (as per Radio Pakistan's news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in Chittagong. The message was translated to Bengali by Dr. Manjula Anwar. The students failed to secure permission from higher authorities to broadcast the message from the nearby Agrabad Station of Radio Pakistan. They crossed Kalurghat Bridge into an area controlled by an East Bengal Regiment under Major Ziaur Rahman. Bengali soldiers guarded the station as engineers prepared for transmission. At 7:45 PM on 26 March 1971,[60] Major Ziaur Rahman broadcast announcement of the declaration of independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

This is Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra. I, Major Ziaur Rahman, at the direction of Bangobondhu Mujibur Rahman, hereby declare that Independent People's Republic of Bangladesh has been established. At his direction , I have taken the command as the temporary Head of the Republic. In the name of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, I call upon all Bengalees to rise against the attack by the West Pakistani Army. We shall fight to the last to free our motherland. Victory is, by the Grace of Allah, ours. Joy Bangla.[61]

The Kalurghat Radio Station's transmission capability was limited, but the message was picked up by a Japanese ship in Bay of Bengal. It was then re-transmitted by Radio Australia[62] and later by the British Broadcasting Corporation.

M A Hannan, an Awami League leader from Chittagong, is said to have made the first announcement of the declaration of independence over the radio on 26 March 1971.[63] There is controversy now as to when Major Zia gave his speech. BNP sources maintain that it was 26 March, and there was no message regarding declaration of independence from Mujibur Rahman. Pakistani sources, like Maj. Gen. Fazal Muqeem Khan in his book "PAKISTAN’S CRISIS IN LEADERSHIP"[64] Brigadier Zahir Alam Khan in his book "THE WAY IT WAS"[65] and Lt. Gen. Kamal Matinuddin in his book "TRAGEDY OF ERRORS:EAST PAKISTAN CRISIS, 1968–1971"[66] had written that they heard Major Zia's speech on 26 March 1971 but Maj. Gen. Hakeem A. Qureshi in his book "THE 1971 INDO-PAK WAR: A SOLDIER'S NARRATIVE"[67] (Oxford University Press, Karachi,2002), gives the date of Major Zia's speech as 27 March 1971.

26 March 1971 is considered the official Independence Day of Bangladesh, and the name Bangladesh was in effect henceforth. In July 1971, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi openly referred to the former East Pakistan as Bangladesh.[68] Some Pakistani and Indian officials continued to use the name "East Pakistan" until 16 December 1971.

Liberation war

March to June

At first resistance was spontaneous and disorganised, and was not expected to be prolonged.[69] However, when the Pakistani Army cracked down upon the population, resistance grew. The Mukti Bahini became increasingly active. The Pakistani military sought to quell them, but increasing numbers of Bengali soldiers defected to the underground "Bangladesh army". These Bengali units slowly merged into the Mukti Bahini and bolstered their weaponry with supplies from India. Pakistan responded by airlifting in two infantry divisions and reorganising their forces. They also raised paramilitary forces of Razakars, Al-Badrs and Al-Shams (who were mostly members of the Muslim League, Jamaat E Islami and other Islamist groups), as well as other Bengalis who opposed independence, and Bihari Muslims who had settled during the time of partition.

On 17 April 1971, a provisional government was formed in Meherpur district in western Bangladesh bordering India with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was in prison in Pakistan, as President, Syed Nazrul Islam as Acting President, Tajuddin Ahmed as Prime Minister, and General Muhammad Ataul Ghani Osmani as Commander-in-Chief, Bangladesh Forces. As fighting grew between the occupation army and the Bengali Mukti Bahini, an estimated 10 million Bengalis, sought refuge in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal.[70]

June – September

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col. M. A. G. Osmani as commander-in-chief (C-in-C) with the status of Cabinet Minister, Lt. Col., Abdur Rabb as chief of Staff (COS), Group Captain A K Khandker as Deputy Chief of Staff (DCOS) and Major A R Chowdhury as Assistant Chief of Staff (ACOS).

General Osmani had differences of opinion with the Indian leadership regarding the role of the Mukti Bahini in the conflict. Indian leadership initially envisioned Bengali forces to be trained into a small elite guerrilla force of 8,000 members, led by the surviving East Bengal Regiment soldiers operating in small cells around Bangladesh to facilitate the eventual Indian intervention,[71] but the Bangladesh Government in exile and General Osmani favoured the following strategy:[72][73]

- Bengali conventional force would occupy lodgment areas inside Bangladesh and then Bangladesh government would request international diplomatic recognition and intervention. Initially Mymensingh was picked for this operation, but Gen. Osmani later settled on Sylhet.

- Sending the maximum number to guerrillas inside Bangladesh as soon as possible with the following objectives:[74][75]

- Increasing Pakistani casualties through raids and ambush.

- Cripple economic activity by hitting power stations, railway lines, storage depots and communication networks.

- Destroy Pakistan army mobility by blowing up bridges/culverts, fuel depots, trains and river crafts.

- The strategic objective was to make the Pakistanis spread their forces inside the province, so attacks could be made on isolated Pakistani detachments.

Bangladesh was divided into eleven sectors in July,[76] each with a commander chosen from defected officers of the Pakistani army who joined the Mukti Bahini to conduct guerrilla operations and train fighters. Most of their training camps were situated near the border area and were operated with assistance from India. The 10th Sector was directly placed under the Commander in Chief (C-in-C) General M. A. G. Osmani and included the Naval Commandos and C-in-C's special force.[77] Three brigades (11 Battalions) were raised for conventional warfare; a large guerrilla force (estimated at 100,000) was trained.[78]

Three brigades (8 infantry battalions and 3 artillery batteries) were put into action between July – September.[79] During June – July, Mukti Bahini had regrouped across the border with Indian aid through Operation Jackpot and began sending 2000 – 5000 guerrillas across the border,[80] the so-called Moonsoon Offensive, which for various reasons (lack of proper training, supply shortage, lack of a proper support network inside Bangladesh etc.) failed to achieve its objectives.[81][82][83] Bengali regular forces also attacked BOPs in Mymensingh, Comilla and Sylhet, but the results were mixed. Pakistani authorities concluded that they had successfully contained the Monsoon Offensive, which proved a near-accurate observation.[84][85]

Guerrilla operations, which slackened during the training phase, picked up after August. Economic and military targets in Dhaka were attacked. The major success story was Operation Jackpot, in which naval commandos mined and blew up berthed ships in Chittagong, Mongla, Narayanganj and Chandpur on 15 August 1971.[86][87]

October – December

Bangladesh conventional forces attacked border outposts. Kamalpur, Belonia and the Battle of Boyra are a few examples. 90 out of 370 BOPs fell to Bengali forces. Guerrilla attacks intensified, as did Pakistani and Razakar reprisals on civilian populations. Pakistani forces were reinforced by eight battalions from West Pakistan. The Bangladeshi independence fighters even managed to temporarily capture airstrips at Lalmonirhat and Shalutikar.[88] Both of these were used for flying in supplies and arms from India. Pakistan sent another 5 battalions from West Pakistan as reinforcements.

Indian involvement

|

Major battles |

Wary of the growing involvement of India, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) launched a pre-emptive strike on Indian Air Force bases on 3 December 1971. The attack was modelled on the Israeli Air Force's Operation Focus during the Six-Day War, and intended to neutralise the Indian Air Force planes on the ground. The strike was seen by India as an open act of unprovoked aggression. This marked the official start of the Indo-Pakistani War.

As a response to the attack, both India and Pakistan formally acknowledged the "existence of a state of war between the two countries", even though neither government had formally issued a Declaration of War.[89]

Three Indian corps were involved in the liberation of East Pakistan. They were supported by nearly three brigades of Mukti Bahini fighting alongside them, and many more fighting irregularly. This was far superior to the Pakistani army of three divisions.[90] The Indians quickly overran the country, selectively engaging or bypassing heavily defended strongholds. Pakistani forces were unable to effectively counter the Indian attack, as they had been deployed in small units around the border to counter guerrilla attacks by the Mukti Bahini.[91] Unable to defend Dhaka, the Pakistanis surrendered on 16 December 1971.

The air and naval war

The Indian Air Force carried out several sorties against Pakistan, and within a week, IAF aircraft dominated the skies of East Pakistan. It achieved near-total air supremacy by the end of the first week as the entire Pakistani air contingent in the east, PAF No.14 Squadron, was grounded because of Indian and Bangladesh airstrikes at Tejgaon, Kurmitolla, Lal Munir Hat and Shamsher Nagar. Sea Hawks from INS Vikrant also struck Chittagong, Barisal and Cox's Bazar, destroying the eastern wing of the Pakistan Navy and effectively blockading the East Pakistan ports, thereby cutting off any escape routes for the stranded Pakistani soldiers. The nascent Bangladesh Navy (comprising officers and sailors who defected from the Pakistani Navy) aided the Indians in the marine warfare, carrying out attacks, most notably Operation Jackpot.[citation needed]

Surrender and aftermath

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Army forces located in East Pakistan signed the Instrument of Surrender. At the time of surrender only a few countries had provided diplomatic recognition to the new nation. Over 93,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian forces, making it the largest surrender since World War II.[6][92] Bangladesh sought admission in the UN with most voting in its favour, but China vetoed this as Pakistan was its key ally.[93] The United States, also a key ally of Pakistan, was one of the last nations to accord Bangladesh recognition.[94] To ensure a smooth transition, in 1972 the Simla Agreement was signed between India and Pakistan. The treaty ensured that Pakistan recognised the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani PoWs. India treated all the PoWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925.[95] It released more than 93,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months.[6] Further, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were also pardoned by India. The accord also gave back more than 13,000 km2 (5,019 sq mi) of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas;[96] most notably Kargil (which would in turn again be the focal point for a war between the two nations in 1999). This was done as a measure of promoting "lasting peace" and was acknowledged by many observers as a sign of maturity by India. However, some in India[who?] felt that the treaty had been too lenient to Bhutto, who had pleaded for leniency, arguing that the fragile democracy in Pakistan would crumble if the accord was perceived as being overly harsh by Pakistanis.

Reaction in West Pakistan to the war

Reaction to the defeat and dismemberment of half the nation was a shocking loss to top military and civilians alike. No one had expected that they would lose the formal war in under a fortnight, and there was also unsettlement over what was perceived as a meek surrender of the army in East Pakistan. Yahya Khan's dictatorship collapsed and gave way to Bhutto, who took the opportunity to rise to power. General Niazi, who surrendered along with 93,000 troops, was viewed with suspicion and contempt upon his return to Pakistan. He was shunned and branded a traitor. The war also exposed the shortcomings of Pakistan's declared strategic doctrine that the "defence of East Pakistan lay in West Pakistan".[97][98][99] Pakistan also failed to gather international support, and found itself fighting a lone battle with only the USA providing any external help. This further embittered the Pakistanis, who had faced the worst military defeat of an army in decades. The debacle immediately prompted an enquiry headed by Justice Hamoodur Rahman.

Atrocities

During the war there were widespread killings and other atrocities – including the displacement of civilians in Bangladesh (East Pakistan at the time) and widespread violations of human rights – carried out by the Pakistan Army with support from political and religious militias, beginning with the start of Operation Searchlight on 25 March 1971. Bangladeshi authorities claimed that three million people were killed,[52] while the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, an official Pakistan Government investigation, put the figure at 26,000 civilian casualties.[100] The international media and reference books in English by authors and genocide scholars such as Samuel Totten have also published figures of up to 3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole,[101] although independent researchers put the toll at 300,000 to 500,000.[8] A further eight to ten million people fled the country to seek safety in India.[102]

A 2008 British Medical Journal study by Ziad Obermeyer, Christopher J. L. Murray, and Emmanuela Gakidou estimated that up to 269,000 civilians died as a result of the conflict; the authors note that this is far higher than a previous estimate of 58,000 from Uppsala University and the Peace Research Institute, Oslo.[103] According to Serajur Rahman, the official Bangladeshi estimate of "3 lakhs" (300,000, written "3,00,000") was wrongly translated into English as 3 million.[104]

A large section of the intellectual community of Bangladesh were murdered, mostly by the Al-Shams and Al-Badr forces,[105] at the instruction of the Pakistani Army.[106] Just two days before the surrender, on 14 December 1971, Pakistan Army and Razakar militia (local collaborators) picked up at least 100 physicians, professors, writers and engineers in Dhaka, and murdered them, leaving the dead bodies in a mass grave.[107] There are many mass graves in Bangladesh, with an increasing number discovered throughout the proceeding years (such as one in an old well near a mosque in Dhaka, located in the non-Bengali region of the city, which was discovered in August 1999).[108] The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dhaka to the United States State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dhaka University and other civilians.[109] Numerous women were tortured, raped and killed during the war; the exact numbers are not known and are a subject of debate. Bangladeshi sources cite a figure of 200,000 women raped, giving birth to thousands of war babies.[110][111][112] The Pakistan Army also kept numerous Bengali women as sex-slaves inside the Dhaka Cantonment. Most of the girls were captured from Dhaka University and private homes.[113] There was significant sectarian violence not only perpetrated and encouraged by the Pakistani army,[114] but also by Bengali nationalists against non-Bengali minorities, especially Biharis.[115]

On 16 December 2002, the George Washington University's National Security Archive published a collection of declassified documents, consisting mostly of communications between US embassy officials and United States Information Service centres in Dhaka and India, and officials in Washington DC.[116] These documents show that US officials working in diplomatic institutions within Bangladesh used the terms "selective genocide"[117] and "genocide" (see The Blood Telegram) for information on events they had knowledge of at the time). Genocide is the term that is still used to describe the event in almost every major publication and newspaper in Bangladesh,[118][119] although elsewhere, particularly in Pakistan, the actual death toll, motives, extent, and destructive impact of the actions of the Pakistani forces are disputed.

Aftermath

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (December 2013) |

In the second decade of the 21st century a spate of death sentences were handed out leading to opposition protests.

Foreign reaction

United Nations

Though the United Nations condemned the human rights violations during and following Operation Searchlight, it failed to defuse the situation politically before the start of the war.

Following Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration of independence in March 1971, India undertook a world-wide campaign to drum up political, democratic and humanitarian support for the people of Bangladesh for their liberation struggle. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi toured a large number of countries in a bid to create awareness of the Pakistani atrocities against Bengalis. This effort was to prove vital later during the war, in framing the world's context of the war and to justify military action by India.[120] Also, following Pakistan's defeat, it ensured prompt recognition of the newly independent state of Bangladesh.

Following India's entry into the war, Pakistan, fearing certain defeat, made urgent appeals to the United Nations to intervene and force India to agree to a cease fire. The UN Security Council assembled on 4 December 1971 to discuss the hostilities in South Asia. After lengthy discussions on 7 December, the United States made a resolution for "immediate cease-fire and withdrawal of troops". While supported by the majority, the USSR vetoed the resolution twice. In light of the Pakistani atrocities against Bengalis, the United Kingdom and France abstained on the resolution.[89][121]

On 12 December, with Pakistan facing imminent defeat, the United States requested that the Security Council be reconvened. Pakistan's Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was rushed to New York City to make the case for a resolution on the cease fire. The council continued deliberations for four days. By the time proposals were finalised, Pakistan's forces in the East had surrendered and the war had ended, making the measures merely academic. Bhutto, frustrated by the failure of the resolution and the inaction of the United Nations, ripped up his speech and left the council.[121]

Most UN member nations were quick to recognise Bangladesh within months of its independence.[120]

Bhutan

As the Bangladesh Liberation War approached the defeat of the Pakistan Army, Bhutan became the first country in the world to recognize the newly independent state on 6 December 1971. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first President of Bangladesh visited Bhutan to attend the coronation of Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the fourth King of Bhutan in June, 1974.[122]

USA and USSR

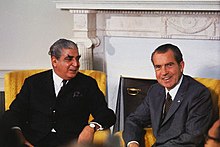

The United States supported Pakistan[123] both politically and materially. US President Richard Nixon denied getting involved in the situation, saying that it was an internal matter of Pakistan, but when Pakistan's defeat seemed certain, Nixon sent the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal,[124] a move deemed by the Indians as a nuclear threat. Enterprise arrived on station on 11 December 1971. On 6 and 13 December, the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of ships, armed with nuclear missiles, from Vladivostok; they trailed US Task Force 74 in the Indian Ocean from 18 December until 7 January 1972.[125]

Nixon and Henry Kissinger feared Soviet expansion into South and Southeast Asia. Pakistan was a close ally of the People's Republic of China, with whom Nixon had been negotiating a rapprochement and which he intended to visit in February 1972. Nixon feared that an Indian invasion of West Pakistan would mean total Soviet domination of the region, and that it would seriously undermine the global position of the United States and the regional position of America's new tacit ally, China. To demonstrate to China the bona fides of the United States as an ally, and in direct violation of the US Congress-imposed sanctions on Pakistan, Nixon sent military supplies to Pakistan and routed them through Jordan and Iran,[126] while also encouraging China to increase its arms supplies to Pakistan. The Nixon administration also ignored reports it received of the genocidal activities of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan, most notably the Blood telegram.

The Soviet Union supported Bangladesh and Indian armies, as well as the Mukti Bahini during the war, recognising that the independence of Bangladesh would weaken the position of its rivals – the United States and China. It gave assurances to India that if a confrontation with the United States or China developed, the USSR would take countermeasures. This was enshrined in the Indo-Soviet friendship treaty signed in August 1971. The Soviets also sent a nuclear submarine to ward off the threat posed by USS Enterprise in the Indian Ocean.

At the end of the war, the Warsaw Pact countries were among the first to recognise Bangladesh. The Soviet Union accorded recognition to Bangladesh on 25 January 1972.[127] The United States delayed recognition for some months, before according it on 8 April 1972.[128]

China

As a long-standing ally of Pakistan, the People's Republic of China reacted with alarm to the evolving situation in East Pakistan and the prospect of India invading West Pakistan and Pakistani-controlled Kashmir. Believing that just such an Indian attack was imminent, Nixon encouraged China to mobilise its armed forces along its border with India to discourage it. The Chinese did not, however, respond to this encouragement, because unlike the 1962 Sino-Indian War when India was caught entirely unaware, this time the Indian Army was prepared and had deployed eight mountain divisions to the Sino-Indian border to guard against such an eventuality.[89] China instead threw its weight behind demands for an immediate ceasefire.

When Bangladesh applied for membership to the United Nations in 1972, China vetoed their application[129] because two United Nations resolutions regarding the repatriation of Pakistani prisoners of war and civilians had not yet been implemented.[130] China was also among the last countries to recognise independent Bangladesh, refusing to do so until 31 August 1975.[120][129]

See also

- Timeline of the Bangladesh War

- Artistic depictions of Bangladesh Liberation War

- Mukti Bahini

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- Movement demanding trial of war criminals (Bangladesh)

- Liberation War Museum

- Rape during the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Recipients of Bangladeshi military awards in 1971

- Jahanara Imam

- Shafi Imam Rumi

- The Concert for Bangladesh

Footnotes

- ^ "Gen. Tikka Khan, 87; 'Butcher of Bengal' Led Pakistani Army". Los Angeles Times. 30 March 2002.

- ^ a b c India – Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction – Tom Cooper, Khan Syed Shaiz Ali

- ^ Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway By Owen Bennett-Jones, Lindsay Brown, John Mock, Sarina Singh, Pg 30

- ^ p. 442 Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 [ISBN 81-7062-014-7]

- ^ a b Figures from The Fall of Dacca by Jagjit Singh Aurora in The Illustrated Weekly of India dated 23 December 1973 quoted in Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 [ISBN 81-7062-014-7]

- ^ a b c "54 Indian PoWs of 1971 war still in Pakistan". Daily Times. 19 January 2005. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Figure from Pakistani Prisoners of War in India by Col S.P. Salunke p.10 quoted in Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 (ISBN 81-7062-014-7)

- ^ a b "Bangladesh Islamist leader Ghulam Azam charged". BBC. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ "Bangladesh sets up war crimes court – Central & South Asia". Al Jazeera. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Library of Congress

- ^ en, Samuel; Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs. Dictionary of Genocide: A-L. Volume 1: Greenwood. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-313-32967-8.

- ^ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "New Year 2013". The Daily Star. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Bangladesh Genocide Archive | Collaborators and War Criminals. Genocidebangladesh.org. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ New York Times, 30 July 1971

- ^ The Wall Street Jornal, 27 July 1971.

- ^ Daily Sangram, 15 September 1971

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Encyclopaedia of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Page 235

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Bangladesh, Page 289

- ^ "Britain Proposes Indian Partition". Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: The Leader-Post. BUP. 2 June 1947.

- ^ Grover, Preston (8 June 1947). "India Partition Will Present Many Problems". Sarasota, Florida, USA: Herald-Tribune, via Google News. Associated Press.

- ^ "Problems of Partition". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia. 14 June 1947.

- ^ "''Genocide in Bangladesh, 1971.'' Gendercide Watch". Gendercide.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "''Emerging Discontent, 1966–70.'' Country Studies Bangladesh". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971: Military Action: Operation Searchlight Bose S Economic and Political Weekly Special Articles, 8 October 2005[dead link]

- ^ The Pakistani Slaughter That Nixon Ignored, Syndicated Column by Sydney Schanberg, The New York Times, 3 May 1994

- ^ a b "Civil War Rocks East Pakistan". Daytona Beach, Florida, USA: Daytona Beach Morning Journal, via Google News. Associated Press. 27 March 1971.

- ^ a b Crisis in South Asia – A report by Senator Edward Kennedy to the Subcommittee investigating the Problem of Refugees and Their Settlement, Submitted to U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, 1 November 1971, U.S. Govt. Press.pp6-7

- ^ "''India and Pakistan: Over the Edge.'' TIME 13 December 1971 Vol. 98 No. 24". Time. 13 December 1971. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Al Helal, Bashir, Language Movement, Banglapedia

- ^ a b "Language Movement". Banglapedia – The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original (PHP) on 1 March 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "International Mother Language Day – Background and Adoption of the Resolution". Government of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (1997). "Language and Ethnicity in Pakistan". Asian Survey. 37 (9): 833–839. doi:10.1525/as.1997.37.9.01p02786. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645700.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rahman, Tariq (1997). "The Medium of Instruction Controversy in Pakistan" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 18 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1080/01434639708666310. ISSN 0143-4632. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ a b c Oldenburg, Philip (1985). "'A Place Insufficiently Imagined': Language, Belief, and the Pakistan Crisis of 1971". The Journal of Asian Studies. 44 (4): 711–733. doi:10.2307/2056443. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2056443.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Library of Congress studies". Memory.loc.gov. 1 July 1947. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ "Demons of December – Road from East Pakistan to Bangladesh". Defencejournal.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rounaq Jahan (1972). Pakistan: Failure in National Integration. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03625-6. Pg 166–167

- ^ Sayeed, Khalid B. (1967). The Political System of Pakistan. Houghton Mifflin. p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e

Hassan, Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dr. Professor Mubashir (2000). "§Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: All Power to People! Democracy and Socialism to People!". The Mirage of Power (in English). Oxford University, United Kingdom: Dr. Professor Mubashir Hassan, professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology and the Oxford University Press. pp. 50–90. ISBN 978-0-19-579300-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ India Meteorological Department (1970). "Annual Summary – Storms & Depressions" (PDF). India Weather Review 1970. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ Kabir, M. M.; Saha B. C.; Hye, J. M. A. "Cyclonic Storm Surge Modelling for Design of Coastal Polder" (PDF). Institute of Water Modelling. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[dead link] - ^ Schanberg, Sydney (22 November 1970). "Yahya Condedes 'Slips' In Relief". The New York Times.

- ^ Staff writer (23 November 1970). "East Pakistani Leaders Assail Yahya on Cyclone Relief". The New York Times. Reuters.

- ^ Staff writer (18 November 1970). "Copter Shortage Balks Cyclone Aid". The New York Times.

- ^ Durdin, Tillman (11 March 1971). "Pakistanis Crisis Virtually Halts Rehabilitation Work in Cyclone Region". The New York Times.

- ^ Olson, Richard (21 February 2005). "A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964–2003" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ Sarmila Bose Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971: Military Action: Operation Searchlight[dead link] Economic and Political Weekly Special Articles, 8 October 2005

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness To Surrender, pp 63, 228–9, id = ISBN 984-05-1373-7

- ^ From Deterrence and Coercive Diplomacy to War – The 1971 Crisis in South Asia. Asif Siddiqui, Journal of International and Area Studies Vol.4 No.1, 1997. 12. pp 73–92.

- ^ a b White, Matthew, Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century

- ^ Zunaid Kazi. "History : The Bangali Genocide, 1971". Virtual Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rummel, Rudolph. "Chapter 8: Statistics of Pakistan's Democide Estimates, Calculations, And Sources". Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900. p. 544. ISBN 978-3-8258-4010-5.

"...They also planned to indiscriminately murder hundreds of thousands of its Hindus and drive the rest into India. ... This despicable and cutthroat plan was outright genocide'.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Debasish Roy Chowdhury (23 June 2005). "Indians are bastards anyway". Asia Times Online.

- ^ Malik, Amita (1972). The Year of the Vulture. New Delhi: Orient Longmans. pp. 79–83. ISBN 0-8046-8817-6.

- ^ "Bangladesh war: The article that changed history", BBC, 16 December 2011

- ^ "The Hindu genocide that Hindus and the world forgot". India Tribune. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica – Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ HISTORY OF FREEDOM MOVEMENT IN BANGLADESH, 1943–1973: SOME INVOLVEMENT WRITTEN BY JYOTI SEN GUPTA, NAYA PROKASH, 206, BIDHAN SARANI, CALCUTTA-6, FIRST EDITION, 1974, CHAPTER-15, PAGE-325 and 326. Books.google.com.bd. 1974. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ HISTORY OF FREEDOM MOVEMENT IN BANGLADESH, 1943–1973: SOME INVOLVEMENT WRITTEN BY JYOTI SEN GUPTA, NAYA PROKASH, 206, BIDHAN SARANI, CALCUTTA-6, FIRST EDITION, 1974, CHAPTER-15, PAGE-325 and 326. Books.google.com.bd. 1974. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ HISTORY OF FREEDOM MOVEMENT IN BANGLADESH, 1943–1973: SOME INVOLVEMENT WRITTEN BY JYOTI SEN GUPTA, NAYA PROKASH, 206, BIDHAN SARANI, CALCUTTA-6, FIRST EDITION, 1974, CHAPTER-15, PAGE-325 and 326. Books.google.com.bd. 1974. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Virtual Bangladesh

- ^ Maj. Gen. Fazal Muqeem Khan – Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership; National Book Foundation, Islamabad, 1973; page 79

- ^ Brigadier Zahir Alam Khan – THE WAY IT WAS; Dynavis Pvt.Ltd, Karachi, September 1998

- ^ Lt. Gen. Kamal Matinuddin – Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis, 1968–1971; Wajidalis, Lahore, 1994; page 255

- ^ "THE 1971 INDO-PAK WAR: A SOLDIER'S NARRATIVE"

- ^ M1 India, Pakistan, and the United States: Breaking with the Past By Shirin R. Tahir-Kheli ISBN 0-87609-199-0, 1997, Council on Foreign Relations. pp 37

- ^ Pakistan Defence Journal, 1977, Vol 2, pp. 2–3

- ^ "Bangladesh". State.gov. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, pp90 – pp91

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, pp42 – pp44, pp90 – pp91

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara’ 71, pp45 – pp46

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, pp. 227, 235

- ^ Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M., Bangladesh at War, pp161 – pp163

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, pp. 226–231

- ^ Bangladesh Liberation Armed Force, Liberation War Museum, Bangladesh.

- ^ Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar, O GENERAL MY GENERAL (Life and Works of General M. A. G. Osmani), pp. 35–109, ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, pp44

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, pp 44

- ^ Ali, Maj. Gen. Rao Farman, How Pakistan Got Divided, pp 100

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, pp 64 – 65

- ^ Khan, Maj. Gen. Fazal Mukeem, Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership, pp125

- ^ Ali, Rao Farman, When Pakistan Got Divided, p 100

- ^ Niazi, Lt. Gen. A.A.K, The Betrayal of East Pakistan, p 96

- ^ Roy, Mihir, K (1995). War in the Indian Ocean. 56, Gautaum Nagar, New-Delhi, 110049, India: Lancer Publisher & Distributor. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robi,, Mir Mustak Ahmed (2008). Chetonai Ekattor. 38, Bangla Bazar (2nd Floor), Dhaka-1100, Bangladesh: Zonaki Publisher. p. 69. ISBN 984-70226-0011-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid prefix (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "India – Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction By Tom Cooper, with Khan Syed Shaiz Ali". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "India and Pakistan: Over the Edge". Time. 13 December 1971. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Out of War, a Nation Is Born". Time. 20 December 1971. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Indian Army after Independence by Maj KC Praval 1993 Lancer, p. 317 ISBN 1-897829-45-0

- ^ "The 1971 war". BBC News. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Section 9. Situation in the Indian Subcontinent, 2. Bangladesh's international position – Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- ^ Guess who's coming to dinner Naeem Bangali

- ^ "Bangladesh: Unfinished Justice for the crimes of 1971 – South Asia Citizens Web". Sacw.net. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Simla Agreement 1972 – Story of Pakistan". Storyofpakistan.com. 1 June 2003. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Defencejournal". Defencejournal. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Redefining security imperatives by M Sharif[dead link]

- ^ "General Niazi's Failure in High Command". Ghazali.net. 21 August 2000. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, chapter 2, paragraph 33

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs. Dictionary of Genocide: A-L. Volume 1: Greenwood. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-313-32967-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Rummel, Rudolph J., "Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900", ISBN 3-8258-4010-7, Chapter 8, Table 8.2 Pakistan Genocide in Bangladesh Estimates, Sources, and Calculations: lowest estimate two million claimed by Pakistan (reported by Aziz, Qutubuddin. Blood and tears Karachi: United Press of Pakistan, 1974. pp. 74,226), all the other sources used by Rummel suggest a figure of between 8 and 10 million with one (Johnson, B. L. C. Bangladesh. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1975. pp. 73,75) that "could have been" 12 million.

- ^ Obermeyer, Ziad, et al., "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme", British Medical Jornal, June 2008.

- ^ Rahman, Serajur, "Mujib's confusion on Bangladeshi deaths", Letters, The Guardian, May 23, 2011.

- ^ Many of the eyewitness accounts of relations that were picked up by "Al Badr" forces describe them as Bengali men. The only survivor of the Rayerbazar killings describes the captors and killers of Bengali professionals as fellow Bengalis. See 57 Dilawar Hossain, account reproduced in 'Ekattorer Ghatok-dalalera ke Kothay' (Muktijuddha Chetona Bikash Kendro, Dhaka, 1989)

- ^ Asadullah Khan The loss continues to haunt us in The Daily Star 14 December 2005

- ^ "125 Slain in Dacca Area, Believed Elite of Bengal". The New York Times. New York, NY, USA. 19 December 1971. p. 1. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

At least 125 persons, believed to be physicians, professors, writers and teachers were found murdered today in a field outside Dacca. All the victims' hands were tied behind their backs and they had been bayoneted, garroted or shot. They were among an estimated 300 Bengali intellectuals who had been seized by West Pakistani soldiers and locally recruited supporters.

- ^ DPA report Mass grave found in Bangladesh in The Chandigarh Tribune 8 August 1999

- ^ Sajit Gandhi The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971 National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79 16 December 2002

- ^ "Bengali Wives Raped in War Are Said to Face Ostracism" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 January 1972. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Menen, Aubrey (23 July 1972). "The Rapes of Bangladesh" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Astrachan, Anthony (22 March 1972). "U.N. Asked to Aid Bengali Abortions" (PDF). The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ East Pakistan: Even the Skies Weep, Time, 25 October 1971.

- ^ U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Sitrep: Army Terror Campaign Continues in Dacca; Evidence Military Faces Some Difficulties Elsewhere, 31 March 1971, Confidential, 3 pp

- ^ Sen, Sumit (1999). "Stateless Refugees and the Right to Return: the Bihari Refugees of South Asia, Part 1" (PDF). International Journal of Refugee Law. 11 (4): 625–645. doi:10.1093/ijrl/11.4.625. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help) - ^ Gandhi, Sajit, ed. (16 December 2002), The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971: National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79

- ^ U.S. Consulate in Dacca (27 March 1971), Selective genocide, Cable (PDF)

- ^ Editorial "The Jamaat Talks Back" in The Bangladesh Observer 30 December 2005

- ^ Dr. N. Rabbee "Remembering a Martyr" Star weekend Magazine, The Daily Star 16 December 2005

- ^ a b c "The Recognition Story". Bangladesh Strategic and Development Forum. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's farewell speech to the United Nations Security Council – Wikisource". En.wikisource.org. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Constitution Issued: Rahman Resigns". Altus, Oklahoma, USA: The Altus Times-Democrat, via Google News. Associated Press. 11 January 1972.

- ^ "Nixon and Pakistan: An Unpopular Alliance". Miami, Florida, USA: The Miami News, via Google News. Reuters. 17 December 1971.

- ^ Scott, Paul (21 December 1971). "Naval 'Show of Force' By Nixon Meant as Blunt Warning to India". Bangor Daily News. Google News.

- ^ India's Borderland Disputes: China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal, Anna Orton

- ^ Shalom, Stephen R., The Men Behind Yahya in the Indo-Pak War of 1971

- ^ "USSR, Czechoslovakia Recognize Bangladesh". Sumter, South Carolina, USA: The Sumter Daily Item, via Google News. Associated Press. 25 January 1972.

- ^ "Nixon Hopes for Subcontinent Peace". Spartanburg, South Carolina, USA: Herald-Journal, via Google News. Associated Press. 9 April 1972.

- ^ a b "China Recognizes Bangladesh". Oxnard, California, USA: The Press Courier, via Google News. Associated Press. 1 September 1975.

- ^ "China Veto Downs Bangladesh UN Entry". Montreal, Quebec, Canada: The Montreal Gazette, via Google News. United Press International. 26 August 1972.

References

- Pierre Stephen and Robert Payne: Massacre, Macmillan, New York, (1973). ISBN 0-02-595240-4

- Christopher Hitchens "The Trials of Henry Kissinger", Verso (2001). ISBN 1-85984-631-9

- Library of Congress Country Studies

Further reading

- Ayoob, Mohammed and Subrahmanyam, K., The Liberation War, S. Chand and Co. pvt Ltd. New Delhi, 1972.

- Bhargava, G.S., Crush India or Pakistan's Death Wish, ISSD, New Delhi, 1972.

- Bhattacharyya, S. K., Genocide in East Pakistan/Bangladesh: A Horror Story, A. Ghosh Publishers, 1988.

- Brownmiller, Susan: Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, Ballantine Books, 1993.

- Choudhury, G.W., "Bangladesh: Why It Happened." International Affairs. (1973). 48(2): 242–249.

- Choudhury, G.W., The Last Days of United Pakistan, Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Govt. of Bangladesh, Documents of the war of Independence, Vol 01-16, Ministry of Information.

- Kanjilal, Kalidas, The Perishing Humanity, Sahitya Loke, Calcutta, 1976

- Johnson, Rob, 'A Region in Turmoil' (New York and London, 2005)

- Malik, Amita, The Year of the Vulture, Orient Longmans, New Delhi, 1972.

- Mascarenhas, Anthony, The Rape of Bangla Desh, Vikas Publications, 1972.

- Matinuddin, General Kamal, Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis, 1968–1971, Wajidalis, Lahore, Pakistan, 1994.

- Mookherjee, Nayanika, A Lot of History: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, D. Phil thesis in Social Anthropology, SOAS, University of London, 2002.

- National Security Archive, The Tilt: the U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971

- Quereshi, Major General Hakeem Arshad, The 1971 Indo-Pak War, A Soldiers Narrative, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Rummel, R.J., Death By Government, Transaction Publishers, 1997.

- Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, Oxford University Press, Karachi, Pakistan, 1977.

- Sisson, Richard & Rose, Leo, War and secession: Pakistan, India, and the creation of Bangladesh, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1990.

- Totten, Samuel et al., eds., Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views, Garland Reference Library, 1997

- US Department of State Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States: Nixon-Ford Administrations, vol. E-7, Documents on South Asia 1969–1972[dead link]

- Zaheer, Hasan: The separation of East Pakistan: The rise and realisation of Bengali Muslim nationalism, Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar (2010). O GENERAL MY GENERAL (Life and Works of General M. A. G. Osmani). The Osmani Memorial Trust, Dhaka, Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4.

External links

- Banglapedia article on the Liberation war of Bangladesh

- 1971 Bangladesh Genocide Archive

- Video Streaming of 5 Liberation war documentaries[dead link]

- Video, audio footage, news reports, pictures and resources from Mukto-mona

- Picture Gallery of the Language Movement 1952 & the Independence War 1971 of Bangladesh[dead link]

- Bangladesh Liberation War. Mujibnagar. Government Documents 1971[dead link]

- Torture in Bangladesh 1971–2004 (PDF)[dead link]

- Eyewitness Accounts: Genocide in Bangladesh

- Genocide 1971[dead link]

- The women of 1971. Tales of abuse and rape by the Pakistan Army.

- Mathematics of a Massacre, Abul Kashem

- The complete Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report

- 1971 Massacre in Bangladesh and the Fallacy in the Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, Dr. M.A. Hasan[dead link]

- Women of Pakistan Apologize for War Crimes, 1996

- Pakistan Army not involved

- Sheikh Mujib wanted a confederation: US papers, by Anwar Iqbal, Dawn, 7 July 2005[dead link]

- Page containing copies of the surrender documents

- A website dedicated to Liberation war of Bangladesh

- Video clip of the surrender by Pakistan[dead link]

- Bangladesh Liberation War Picture Gallery Graphic images, viewer discretion advised

- Use dmy dates from July 2013

- Secession in Pakistan

- Bangladesh Liberation War

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Civil wars post-1945

- History of Bangladesh

- History of Pakistan

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- War crimes in Bangladesh

- Surrenders

- Wars involving Bangladesh

- 1971 in India

- Military history of Bangladesh

- Torture in Bangladesh