Monosodium glutamate

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

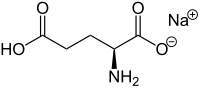

| IUPAC name

Sodium 2-aminopentanedioate

| |

| Identifiers | |

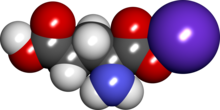

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.035 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E621 (flavour enhancer) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H8NO4Na | |

| Molar mass | 169.111 g/mol (anhydrous), 187.127 g/mol (monohydrate) |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Density | 322 |

| Melting point | 232 °C (450 °F; 505 K) |

| 740 g/L | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

16600 mg/kg (oral, rat)[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Monosodium glutamate (MSG), also known as sodium glutamate, is a sodium salt of glutamic acid. MSG is found naturally in some foods including tomatoes and cheese in this glutamic acid form.[2][3][4] MSG is used in cooking as a flavor enhancer with a savory taste that intensifies the umami flavor of food, as naturally occurring glutamate does in foods such as stews and meat soups.[5][6]

MSG was first prepared in 1908 by Japanese biochemist Kikunae Ikeda, who tried to isolate and duplicate the savory taste of kombu, an edible seaweed used as a broth (dashi) for Japanese cuisine. MSG balances, blends, and rounds the perception of other tastes.[7][8] MSG, along with disodium ribonucleotides, is commonly used and found in stock (bouillon) cubes, soups, ramen, gravy, stews, condiments, savory snacks, etc.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given MSG its generally recognized as safe (GRAS) designation.[9] It is a popular misconception that MSG can cause headaches and other feelings of discomfort, known as "Chinese restaurant syndrome". Several blinded studies show no such effects when MSG is combined with food in normal concentrations, and are inconclusive when MSG is added to broth in large concentrations.[9][10][11] The European Union classifies it as a food additive permitted in certain foods and subject to quantitative limits. MSG has the HS code 2922.42 and the E number E621.[12]

Use

[edit]Pure MSG is reported not to have a highly pleasant taste until it is combined with a savory aroma.[13] The basic sensory function of MSG is attributed to its ability to enhance savory taste-active compounds when added in the proper concentration.[7] The optimal concentration varies by food; in clear soup, the "pleasure score" rapidly falls with the addition of more than one gram of MSG per 100 mL.[14]

The sodium content (in mass percent) of MSG, 12.28%, is about one-third of that in sodium chloride (39.34%), due to the greater mass of the glutamate counterion.[15] Although other salts of glutamate have been used in low-salt soups, they are less palatable than MSG.[16] Food scientist Steve Witherly noted in 2017 that MSG may promote healthy eating by enhancing the flavor of food such as kale while reducing the use of salt.[17]

The ribonucleotide food additives disodium inosinate (E631) and disodium guanylate (E627), as well as conventional salt, are usually used with monosodium glutamate-containing ingredients as they seem to have a synergistic effect. "Super salt" is a mixture of 9 parts salt, to one part MSG and 0.1 parts disodium ribonucleotides (a mixture of disodium inosinate and disodium guanylate).[18]

Safety

[edit]MSG is generally recognized as safe to eat.[2][19] A popular belief is that MSG can cause headaches and other feelings of discomfort, but blinded tests have not provided strong evidence of this.[10] International bodies governing food additives currently consider MSG safe for human consumption as a flavor enhancer.[20] Under normal conditions, humans can metabolize relatively large quantities of glutamate, which is naturally produced in the gut in the course of protein hydrolysis. The median lethal dose (LD50) is between 15 and 18 g/kg body weight in rats and mice, respectively, five times the LD50 of table salt (3 g/kg in rats). The use of MSG as a food additive and the natural levels of glutamic acid in foods are not of toxic concern in humans.[20] Specifically MSG in the diet does not increase glutamate in the brain or affect brain function.[21]

A 1995 report from the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) for the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concluded that MSG is safe when "eaten at customary levels" and, although a subgroup of otherwise-healthy individuals develop an MSG symptom complex when exposed to 3 g of MSG in the absence of food, MSG as a cause has not been established because the symptom reports are anecdotal.[22]

According to the report, no data supports the role of glutamate in chronic disease. High quality evidence has failed to demonstrate a relationship between the MSG symptom complex and actual MSG consumption. No association has been demonstrated, and the few responses were inconsistent. No symptoms were observed when MSG was used in food.[23][24][25][26]

Adequately controlling for experimental bias includes a blinded, placebo-controlled experimental design and administration by capsule, because of the unique aftertaste of glutamates.[25] In a 1993 study, 71 fasting participants were given 5 g of MSG and then a standard breakfast. One reaction (to the placebo, in a self-identified MSG-sensitive individual) occurred.[23] A study in 2000 tested the reaction of 130 subjects with a reported sensitivity to MSG. Multiple trials were performed, with subjects exhibiting at least two symptoms continuing. Two people out of the 130 responded to all four challenges. Because of the low prevalence, the researchers concluded that a response to MSG was not reproducible.[27]

Studies exploring MSG's role in obesity have yielded mixed results.[28][29]

Although several studies have investigated anecdotal links between MSG and asthma, current evidence does not support a causal association.[30]

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) MSG technical report concludes,

"There is no convincing evidence that MSG is a significant factor in causing systemic reactions resulting in severe illness or mortality. The studies conducted to date on Chinese restaurant syndrome (CRS) have largely failed to demonstrate a causal association with MSG. Symptoms resembling those of CRS may be provoked in a clinical setting in small numbers of individuals by the administration of large doses of MSG without food. However, such effects are neither persistent nor serious and are likely to be attenuated when MSG is consumed with food. In terms of more serious adverse effects such as the triggering of bronchospasm in asthmatic individuals, the evidence does not indicate that MSG is a significant trigger factor."[31][32]

However, the FSANZ MSG report says that although no data is available on average MSG consumption in Australia and New Zealand, "data from the United Kingdom indicates an average intake of 590mg/day, with extreme users (97.5th percentile consumers) consuming 2,330mg/day" (Rhodes et al. 1991).[33] In a highly seasoned restaurant meal, intakes as high as 5,000 mg or more may be possible (Yang et al. 1997).[34] When very large doses of MSG (>5 g MSG in a bolus dose) are ingested, plasma glutamate concentration will significantly increase. However, the concentration typically returns to normal within two hours. In general, foods providing metabolizable carbohydrates significantly attenuate peak plasma glutamate levels at doses up to 150mg/kg body weight. Two earlier studies – the 1987 Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and the 1995 Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) – concluded, "there may be a small number of unstable asthmatics who respond to doses of 1.5–2.5 g of MSG in the absence of food". The FASEB evaluation concluded, "sufficient evidence exists to indicate some individuals may experience manifestations of CRS when exposed to a ≥3 g bolus dose of MSG in the absence of food".[31]

Production

[edit]MSG has been produced by three methods: hydrolysis of vegetable proteins with hydrochloric acid to disrupt peptide bonds (1909–1962); direct chemical synthesis with acrylonitrile (1962–1973), and bacterial fermentation (the current method).[35] Wheat gluten was originally used for hydrolysis because it contains more than 30 g of glutamate and glutamine per 100 g of protein. As demand for MSG increased, chemical synthesis and fermentation were studied. The polyacrylic fiber industry began in Japan during the mid-1950s, and acrylonitrile was adopted as a base material to synthesize MSG.[36]

As of 2016, most MSG worldwide is produced by bacterial fermentation in a process similar to making vinegar or yogurt. Sodium is added later, for neutralization. During fermentation, Corynebacterium species, cultured with ammonia and carbohydrates from sugar beets, sugarcane, tapioca or molasses, excrete amino acids into a culture broth from which L-glutamate is isolated. Kyowa Hakko Kogyo (currently Kyowa Kirin) developed industrial fermentation to produce L-glutamate.[37]

The conversion yield and production rate (from sugars to glutamate) continues to improve in the industrial production of MSG, keeping up with demand.[35] The product, after filtration, concentration, acidification, and crystallization, is glutamate, sodium ions, and water.

Chemical properties

[edit]The compound is usually available as the monohydrate, a white, odorless, crystalline powder. The solid contains separate sodium cations Na+

and glutamate anions in zwitterionic form, −OOC-CH(NH+

3)-(CH

2)2-COO−.[38] In solution it dissociates into glutamate and sodium ions.

MSG is freely soluble in water, but it is not hygroscopic and is insoluble in common organic solvents (such as ether).[39] It is generally stable under food-processing conditions. MSG does not break down during cooking and, like other amino acids, will exhibit a Maillard reaction (browning) in the presence of sugars at very high temperatures.[40]

History

[edit]Glutamic acid was discovered and identified in 1866 by the German chemist Karl Heinrich Ritthausen, who treated wheat gluten (for which it was named) with sulfuric acid.[41] Kikunae Ikeda of Tokyo Imperial University isolated glutamic acid as a taste substance in 1908 from the seaweed Laminaria japonica (kombu) by aqueous extraction and crystallization, calling its taste umami ("delicious taste").[42][43] Ikeda noticed that dashi, the Japanese broth of katsuobushi and kombu, had a unique taste not yet scientifically described (not sweet, salty, sour, or bitter).[42] To determine which glutamate could result in the taste of umami, he studied the taste properties of numerous glutamate salts such as calcium, potassium, ammonium, and magnesium glutamate. Of these salts, monosodium glutamate was the most soluble and palatable, as well as the easiest to crystallize.[44] Ikeda called his product "monosodium glutamate" and submitted a patent to produce MSG;[45] the Suzuki brothers began commercial production of MSG in 1909 using the term Ajinomoto ("essence of taste").[35][40][46]

Society and culture

[edit]Regulations

[edit]United States

[edit]MSG is one of several forms of glutamic acid found in foods, in large part because glutamic acid (an amino acid) is pervasive in nature. Glutamic acid and its salts may be present in a variety of other additives, including hydrolyzed vegetable protein, autolyzed yeast, hydrolyzed yeast, yeast extract, soy extracts, and protein isolate, which must be specifically labeled. Since 1998, MSG cannot be included in the term "spices and flavorings". However, the term "natural flavor/s" is used by the food industry for glutamic acid (chemically similar to MSG, lacking only the sodium ion). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not require disclosure of components and amounts of "natural flavor/s."[47]

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]Standard 1.2.4 of the Australia and New Zealand Food Standards Code requires MSG to be labeled in packaged foods. The label must have the food-additive class name (e.g. "flavour enhancer"), followed by the name of the additive ("MSG") or its International Numbering System (INS) number, 621.[48]

Pakistan

[edit]The Punjab Food Authority banned Ajinomoto, commonly known as Chinese salt, which contains MSG, from being used in food products in the Punjab Province of Pakistan in January 2018.[49]

Names

[edit]The following are alternative names for MSG:[50][51]

- Chemical names and identifiers

- Monosodium glutamate or sodium glutamate

- Sodium 2-aminopentanedioate

- Glutamic acid, monosodium salt, monohydrate

- L-Glutamic acid, monosodium salt, monohydrate

- L-Monosodium glutamate monohydrate

- Monosodium L-glutamate monohydrate

- MSG monohydrate

- Sodium glutamate monohydrate

- UNII-W81N5U6R6U

- Flavour enhancer E621

- Trade names

- Accent, produced by B&G Foods Inc., Parsippany, New Jersey, US[52][53]

- Aji-No-Moto, produced by Ajinomoto, 26 countries, head office Japan[54][55]

- Tasting Powder

- Ve-Tsin by Tien Chu Ve-Tsin

- Sazón, distributed by Goya Foods, Jersey City, NJ[56]

Stigma in Western countries

[edit]Origin

[edit]A controversy surrounding the safety of MSG began on 4 April 1968, when Robert Ho Man Kwok wrote a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, coining the term "Chinese restaurant syndrome".[57][58] In his letter, Kwok suggested several possible causes before he nominated MSG for his symptoms.[59][23] This letter was initially met with insider satirical responses, some using race as prop for humorous effect, within the medical community.[57] Some claimed that during the discursive uptake in media, the conversations were recontextualized as legitimate while the supposed race-based motivations of the humor were not parsed.[57]

In January 2018, Howard Steel claimed to Jennifer Lemesurier of Colgate University (who had published an article on the letter) that the letter was actually a prank submission by him under the pseudonym Ho Man Kwok.[58][60] However, there was a Robert Ho Man Kwok who worked at the National Biomedical Research Foundation, both names Steel claimed to have invented.[60] Kwok's children, his colleague at the research foundation, and the son of his boss there confirmed that Robert Ho Man Kwok, who had died in 2014, wrote this letter.[60] When told this about Kwok's family, Steel's daughter Anna was not very surprised that the story her late father had told so many times over the years was false. He liked to prank people.[60]

Reactions

[edit]Researchers, doctors, and activists have tied the controversy about MSG to xenophobia and racism against Chinese culture,[61][62][63][64][65] saying that East Asian cuisine is being targeted while the widespread use of MSG in other ultra-processed foods has not been stigmatized.[66] These activists have claimed that the perpetuation of the negative image of MSG through the Chinese restaurant syndrome was caused by "xenophobic" or "racist" biases.[67][68]

Food historian Ian Mosby wrote that fear of MSG in Chinese food is part of the US's long history of viewing the "exotic" cuisine of Asia as dangerous and dirty.[69] In 2016, Anthony Bourdain stated in Parts Unknown that "I think MSG is good stuff ... You know what causes Chinese restaurant syndrome? Racism."[70]

In 2020, Ajinomoto, the first corporation to mass-produce MSG for consumers and today its leading manufacturer, launched a campaign called "Redefine CRS" to combat what it said was the myth that MSG is harmful to people's health, saying it intended to highlight the xenophobic prejudice against East Asian cuisine and the scientific evidence.[71]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pinto-Scognamiglio, W.; Amorico, L.; Gatti, G. L. (1972). "[Toxicity and tolerance to monosodium glutamate studied by a conditioned avoidance test]". Il Farmaco; Edizione Pratica. 27 (1): 19–27. ISSN 0430-0912. PMID 5059711.

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers on Monosodium glutamate (MSG)". www.fda.gov. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 19 November 2012.

MSG occurs naturally in many foods, such as tomatoes and cheeses

- ^ "Monosodium glutamate (MSG) – Questions and Answers". Government of Canada. 29 January 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Agostoni C, Carratù B, Boniglia C, Riva E, Sanzini E (August 2000). "Free amino acid content in standard infant formulas: comparison with human milk". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 19 (4): 434–8. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718943. PMID 10963461. S2CID 3141583.

- ^ Ikeda K (November 2002). "New seasonings". Chem Senses. 27 (9): 847–49. doi:10.1093/chemse/27.9.847. PMID 12438213.

- ^ Hayward, Tim (22 May 2015). "OMG I love MSG". Financial Times. Nikkei. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b Loliger J (April 2000). "Function and importance of Glutamate for Savory Foods". Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4s Suppl): 915s–20s. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.915S. PMID 10736352.

- ^ Yamaguchi S (May 1991). "Basic properties of umami and effects on humans". Physiology & Behavior. 49 (5): 833–41. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(91)90192-Q. PMID 1679557. S2CID 20980527.

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers on Monosodium glutamate (MSG)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Obayashi, Y; Nagamura, Y (17 May 2016). "Does monosodium glutamate really cause headache?: a systematic review of human studies". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 17 (1): 54. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0639-4. PMC 4870486. PMID 27189588.

- ^ Wei, Will (16 June 2014). The Truth Behind Notorious Flavor Enhancer MSG. Business Insider (Podcast). Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Food.gov.uk. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Rolls, Edmund T. (September 2009). "Functional neuroimaging of umami taste: what makes umami pleasant?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (3): 804S–13S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462R. PMID 19571217.

- ^ Kawamura Y, Kare MR, eds. (1987). Umami: a basic taste. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Shizuko; Takahashi, Chikahito (January 1984). "Interactions of monosodium glutamate and sodium chloride on saltiness and palatability of a clear soup". Journal of Food Science. 49 (1): 82–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb13675.x.

- ^ Ball P, Woodward D, Beard T, Shoobridge A, Ferrier M (June 2002). "Calcium diglutamate improves taste characteristics of lower-salt soup". Eur J Clin Nutr. 56 (6): 519–23. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601343. PMID 12032651.

- ^ Lubin, Gus (2 February 2017). "Everyone should cook with MSG, says food scientist". Business Insider. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Everyone should cook with MSG, says food scientist". Business Insider.

- ^ Barry-Jester, Anna Maria (8 January 2016). "How MSG Got A Bad Rap: Flawed Science And Xenophobia".

- ^ a b Walker R, Lupien JR (April 2000). "The safety evaluation of monosodium glutamate". Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 1049S–52S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.1049S. PMID 10736380.

- ^ Fernstrom, John D. (2018). "Monosodium Glutamate in the Diet Does Not Raise Brain Glutamate Concentrations or Disrupt Brain Functions". Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 73 (Suppl. 5): 43–52. doi:10.1159/000494782. PMID 30508818.

- ^ Raiten DJ, Talbot JM, Fisher KD (1996). "Executive Summary from the Report: Analysis of Adverse Reactions to Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)". Journal of Nutrition. 125 (6): 2891S–2906S. doi:10.1093/jn/125.11.2891S. PMID 7472671. S2CID 3945714.

- ^ a b c Freeman, Matthew (2006). "Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: A literature review". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 18 (10): 482–486. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x. PMID 16999713. S2CID 21084909.

- ^ Geha RS, Beiser A, Ren C, et al. (April 2000). "Review of alleged reaction to monosodium glutamate and outcome of a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled study". J. Nutr. 130 (4S Suppl): 1058S–62S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.1058S. PMID 10736382. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012.

- ^ a b Tarasoff L.; Kelly M.F. (1993). "Monosodium L-glutamate: a double-blind study and review". Food Chem. Toxicol. 31 (12): 1019–35. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(93)90012-N. PMID 8282275.

- ^ Walker R (October 1999). "The significance of excursions above the ADI. Case study: monosodium glutamate". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 30 (2 Pt 2): S119–21. doi:10.1006/rtph.1999.1337. PMID 10597625.

- ^ Williams, A. N.; Woessner, K.M. (2009). "Monosodium glutamate 'allergy': menace or myth?". Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 39 (5): 640–46. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03221.x. PMID 19389112. S2CID 20044934.

- ^ Shi, Z; Luscombe-Marsh, ND; Wittert, GA; Yuan, B; Dai, Y; Pan, X; Taylor, AW (2010). "Monosodium glutamate is not associated with obesity or a greater prevalence of weight gain over 5 years: Findings from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study of Chinese adults". The British Journal of Nutrition. 104 (3): 457–63. doi:10.1017/S0007114510000760. PMID 20370941.

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (25 August 2008). "Nutrition: MSG Use is Linked to Obesity". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

Consumption of monosodium glutamate, or MSG, the widely used food additive, may increase the likelihood of being overweight, a new study says.

- ^ Stevenson, D. D. (2000). "Monosodium glutamate and asthma". J. Nutr. 130 (4S Suppl): 1067S–73S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.1067S. PMID 10736384.

- ^ a b Monosodium Glutamate, A Safety Assessment, Technical Report Series No. 20. Food Standards Australia New Zealand, Health Minister Chair, Peter Dutton MP. June 2003. ISBN 978-0642345202. ISSN 1448-3017. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Monosodium glutamate search". FoodStandards.gov.au. Food Standards Australia New Zealand, Health Minister Chair, Peter Dutton MP. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Rhodes J, Titherley AC, Norman JA, Wood R, Lord DW (1991). "A survey of the monosodium glutamate content of foods and an estimation of the dietary intake of monosodium glutamate". Food Additives & Contaminants. 8 (5): 663–672. doi:10.1080/02652039109374021. PMID 1818840. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ Yang WH, Drouin MA, Herbert M, Mao Y, Karsh J (1997). "The MSG symptom complex: assessment in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 99 (6 Pt 1): 757–762. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)80008-5. PMID 9215242. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Sano, Chiaki (September 2009). "History of glutamate production". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (3): 728S–32S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462F. PMID 19640955.

- ^ Yoshida T (1970). "Industrial manufacture of optically active glutamic acid through total synthesis". Chemie Ingenieur Technik. 42 (9–10): 641–44. doi:10.1002/cite.330420912.

- ^ Kinoshita, Shukuo; Udaka, Shigezo; Shimamoto, Masakazu (1957). "Studies on amino acid fermentation. Part I. Production of L-glutamic acid by various microorganisms". J Gen Appl Microbiol. 3 (3): 193–205. doi:10.2323/jgam.3.193.

- ^ Sano, Chiaki; Nagashima, Nobuya; Kawakita, Tetsuya; Iitaka Yoichi (1989). "Crystal and Molecular Structures of Monosodium L-Glutamate Monohydrate". Analytical Sciences. 5 (1): 121–22. doi:10.2116/analsci.5.121.

- ^ Win. C., ed. (1995). Principles of Biochemistry. Boston, MA: Brown Pub Co.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, Shizuko; Ninomiya, Kumiko (1998). "What is umami?". Food Reviews International. 14 (2 & 3): 123–38. doi:10.1080/87559129809541155.

- ^ Plimmer, R.H.A. (1912) [1908]. R.H.A. Plimmer; F.G. Hopkins (eds.). The Chemical Constitution of the Protein. Monographs on biochemistry. Vol. Part I. Analysis (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 114. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ a b Lindemann, Bernd; Ogiwara Yoko; Ninomiya, Yuzo (November 2002). "The discovery of umami". Chem Senses. 27 (9): 843–44. doi:10.1093/chemse/27.9.843. PMID 12438211.

- ^ Renton, Alex (10 July 2005). "If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn't everyone in Asia have a headache?". The Guardian.

- ^ "Kikunae Ikeda". Umami Information Center. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Ikeda K (1908). "A production method of seasoning mainly consists of salt of L-glutamic acid". Japanese Patent 14804.

- ^ Kurihara K (September 2009). "Glutamate: from discovery as a food flavor to role as a basic taste (umami)?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (3): 719S–22S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462D. PMID 19640953.

- ^ "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Vol 6, Part 501, Subpart B – Specific Animal Food Labeling Requirements". FDA.gov. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Standard 1.2.4 Labelling of Ingredients". Food Standards Code. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ "Punjab Food Authority bans Chinese salt after scientific panel finds it hazardous for health". Dawn. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Singh, K. K.; Desai, Pinakin. "Glutamate Chemical". TriveniInterChem.com. Riveni InterChem of Triveni Chemicals, manufacturer & supplier of industrial chemicals, India. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Desmo Exports Limited, Chemical Manufacturers and Importers of India (2011). "Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)". DesmoExports.com. Desmo Exports. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Accent Flavor Enhancer". AccentFlavor.com. B&G Foods, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "B&G Foods, Incorporated". Grocery.com. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Monosodium glutamate(MSG)". Umami Global Website. Ajinomoto Co., Inc. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "To Greet the Next 100 Years (Corporate Guide)" (PDF). AAjinomoto Co., Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Sazon Seasoning : Substitutes, Ingredients, Equivalents Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. GourmetSleuth. Retrieved on 4 November 2016.

- ^ a b c LeMesurier, Jennifer L. (8 February 2017). "Uptaking Race: Genre, MSG, and Chinese Dinner". Poroi. 12 (2): 1–23. doi:10.13008/2151-2957.1253.

- ^ a b Blanding, Michael (17 January 2020). "The Strange Case of Dr. Ho Man Kwok". Colgate Magazine. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Kwok, Robert Ho Man (4 April 1968). "Chinese-Restaurant Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 278 (14): 796. doi:10.1056/NEJM196804042781419. PMID 25276867.

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, Lilly (15 February 2019). "668: The Long Fuse". This American Life. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Wahlstedt, Amanda; Bradley, Elizabeth; Castillo, Juan; Gardner Burt, Kate (2021). "MSG Is A-OK: Exploring the Xenophobic History of and Best Practices for Consuming Monosodium Glutamate". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 122 (1): 25–29. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2021.01.020. PMID 33678597. S2CID 232143333.

- ^ Liang, Michelle (18 May 2020). "From MSG to COVID-19: The Politics of America's Fear of Chinese Food". arts.duke.edu. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Jiang, Irene (15 January 2020). "McDonald's is testing chicken sandwiches with MSG, and people are freaking out. Here's why they shouldn't care one bit". Business Insider.

- ^ Nierenberg, Amelia (16 January 2020). "The Campaign to Redefine 'Chinese Restaurant Syndrome'". The New York Times.

- ^ Davis, River (27 April 2019). "The FDA Says It's Safe, So Feel Free to Say 'Yes' to MSG". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Why Do People Freak Out About MSG in Chinese Food?". AJ+ (on YouTube). Al Jazeera Media Network. 14 August 2018. Event occurs at 0:00–1:00m and 5:20–8:30m. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ LeMesurier, Jennifer L. (8 February 2017). "Uptaking Race: Genre, MSG, and Chinese Dinner". Poroi. 12 (2): 1–23. doi:10.13008/2151-2957.1253.

Introduction: 'Chinese Restaurant Syndrome' as Rhetorical [...] Finally, I trace how the journalistic uptakes of this discussion, in only taking up certain medical phrases and terms, reproduce the tacit racism of this boundary policing while avowing the neutrality of medical authority.

- ^ Germain, Thomas (2017). "A Racist Little Hat: The MSG Debate and American Culture". Columbia Undergraduate Research Journal. 2. doi:10.52214/curj.v2i1.4115.

- ^ Anna Barry-Jester, "How MSG Got A Bad Rap: Flawed Science And Xenophobia," FiveThirtyEight, 8 January 2016

- ^ Yeung, Jessie (19 January 2020). "MSG in Chinese food isn't unhealthy – you're just racist, activists say". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Yeung, Jessie (19 January 2020). "MSG in Chinese food isn't unhealthy – you're just racist, activists say". CNN.

External links

[edit]- The Facts on Monosodium Glutamate (EUFIC) Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Dunning, Brian (17 December 2019). "Skeptoid #706: MSG: How a Friendly Flavor Became Your Enemy". Skeptoid.