Culture of Shanghai

The culture of Shanghai or Shanghainese culture is based on the Wuyue culture from the nearby Jiangsu and Zhejiang province, with a unique "East Meets West" Haipai culture generated through the influx of Western influences since the mid-19th century.[1] Mass migration from all across China and the rest of the world has made Shanghai a melting pot of different cultures. It was in Shanghai, for example, that the first motor car was driven and (technically) the first train tracks and modern sewers were laid. It was also the intellectual battleground between socialist writers who concentrated on critical realism, which was pioneered by Lu Xun, Mao Dun, Nien Cheng and the famous French novel by André Malraux, Man's Fate, and the more "bourgeois", more romantic and aesthetically inclined writers, such as Shi Zhecun, Shao Xunmei, Ye Lingfeng and Eileen Chang.[citation needed]

In past years, Shanghai has been recognized as a new influence and inspiration for cyberpunk culture.[2] Futuristic buildings such as the Oriental Pearl Tower and the neon-illuminated Yan'an Elevated Road are examples that have boosted Shanghai's cyberpunk image. The city is well known for having a vibrant international flair.[3]

Language

[edit]The vernacular language spoken in the city is Shanghainese, a dialect of the Taihu Wu subgroup of the Wu Chinese family. This makes it a different language from the official Chinese language, Mandarin, which is mutually unintelligible with Wu Chinese.[5] Modern Shanghainese is based on other dialects of Taihu Wu: Suzhounese, Ningbonese, and the local dialect of Songjiang Prefecture.[6]

Prior to its expansion, the language spoken in Shanghai was subordinate to those spoken around Jiaxing and later Suzhou,[6] and was known as "the local tongue" (本地闲话), which is now being used in suburbs only.[7] In the late 19th century, downtown Shanghainese (上海闲话) appeared, undergoing rapid changes and quickly replacing Suzhounese as the prestige dialect of the Yangtze River Delta region. At the time, most of the city's residents were immigrants from the two adjacent provinces, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, so Shanghainese was mostly a hybrid between Southern Jiangsu and Ningbo dialects. After 1949, Putonghua has also had a great impact on Shanghainese as a result of being rigorously promoted by the government.[6] Since the 1990s, many migrants outside of the Wu-speaking region have come to Shanghai for education and jobs. They often cannot speak the local language and therefore use Putonghua as a lingua franca. Because Putonghua and English were more favored, Shanghainese began to decline, and fluency among young speakers weakened. However, in recent years, there have been movements within the city to promote the local language and protect it from fading out.[8][9]

Cuisine

[edit]

Shanghai cuisine emphasises the use of condiments and meanwhile retaining the original flavours of the raw ingredients materials. Sugar is an important ingredient in Shanghai cuisine, especially when used in combination with soy sauce.[10] Another characteristic is the use of a great variety of seafood and freshwater food. Followings are Shanghai's signature dishes:

- Xiaolongbao – A type of steamed bun made with a thin skin of dough and stuffed with pork or minced crabmeat, and soup. The delicious soup inside can be hold up until it is bitten.

- Shengjian mantou – A type of small, pan-fried steamed bun which is a specialty of Shanghai. It is made from leavened or semi-leavened dough, wrapped around pork (most commonly found) and gelatin fillings that melts into soup/liquid when cooked.[11]

- Shanghai hairy crab – A variety of Chinese mitten crab. The crab is usually steamed with fragrant ginger, and consumed with a dipping sauce of rice vinegar, sugar and ginger. Mixing crabmeat with lard to make Xiefen, and consuming it in xiaolongbao or with tofu is another highlight of hairy crab season.[12]

- Squirrel-shaped mandarin fish – This dish uses fresh mandarin fish. The fish is deep-fried and has a crispy exterior and soft interior. Yellow and red in color, it is displayed in the shape of a squirrel on the plate. Hot broth is poured over, which produces a high-pitched sound. Sour and sweet flavours are combined in this dish.[13]

- Sweet and sour spare ribs – One of the best known rib dishes. The fresh pork ribs, which appear shiny and red after being cooked, are traditionally deep fried then coated in a delicious sweet and sour sauce.[14]

- Shanghai-style borscht – A Shanghai variety of borscht. The recipe was changed by removing beetroot and using tomato paste to color the soup and to add to its sweetness, cream is replaced by flour to generate thickness without inducing sourness as well.[15]

Architecture

[edit]

Shanghai has a rich collection of buildings and structures of various architectural styles. The Bund, located by the bank of the Huangpu River, is home to a row of early 20th-century architecture, ranging in style from the neoclassical HSBC Building to the Art Deco Sassoon House (now part of the Peace Hotel). Many areas in the former foreign concessions are also well-preserved, the most notable being the French Concession.[16] Shanghai is also home to many architecturally distinctive and even eccentric buildings, including the Shanghai Museum, the Shanghai Grand Theatre, the Shanghai Oriental Art Center, and the Oriental Pearl Tower. Despite rampant redevelopment, the Old City still retains some traditional architecture and designs, such as the Yu Garden, an elaborate Jiangnan style garden.[17]

Art Deco

[edit]As a result of its construction boom during the 1920s and 1930s, Shanghai has among the most Art Deco buildings in the world.[16] One of the most famous architects working in Shanghai was László Hudec, a Hungarian-Slovak who lived in the city between 1918 and 1947.[18] His most notable Art Deco buildings include the Park Hotel, the Grand Theatre, and the Paramount.[19] Other prominent architects who contributed to the Art Deco style are Clement Palmer and Arthur Turner, who together designed the Peace Hotel, the Metropole Hotel, and the Broadway Mansions;[20] and Austrian architect GH Gonda, who designed the Capitol Theater. The Bund has been revitalized several times. The first was in 1986, with a new promenade by the Dutch architect Paulus Snoeren.[21] The second was before the 2010 Expo, which includes restoration of the century-old Waibaidu Bridge and reconfiguration of traffic flow.[22]

Shikumen

[edit]

One uniquely Shanghainese cultural element is the shikumen (石库门, "stone storage door") residence, typically two- or three-story gray brick houses with the front yard protected by a heavy wooden door in a stylistic stone arch.[23] Each residence is connected and arranged in straight alleys, known as longtang[a] (弄堂). The house is similar to western-style terrace houses or townhouses, but distinguishes by the tall, heavy brick wall and archway in front of each house.[25]

The shikumen is a cultural blend of elements found in Western architecture with traditional Jiangnan Chinese architecture and social behavior.[23] Like almost all traditional Chinese dwellings, it has a courtyard, which reduces outside noise. Vegetation can be grown in the courtyard, and it can also allow for sunlight and ventilation to the rooms.[26]

Soviet neoclassical

[edit]Some of Shanghai's buildings feature Soviet neoclassical architecture or Stalinist architecture, though the city has fewer such structures than Beijing. These buildings were mostly erected between the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 and the Sino-Soviet Split in the late 1960s. During this time period, large numbers of Soviet experts, including architects, poured into China to aid the country in the construction of a communist state. An example of Soviet neoclassical architecture in Shanghai is the modern-day Shanghai Exhibition Center.[27]

Skyscrapers

[edit]

Shanghai—Lujiazui in particular—has numerous skyscrapers, making it the fifth city in the world with the most skyscrapers.[28] Among the most prominent examples are the 421 m (1,381 ft) high Jin Mao Tower, the 492 m (1,614 ft) high Shanghai World Financial Center, and the 632 m (2,073 ft) high Shanghai Tower, which is the tallest building in China and the second tallest in the world.[29] Completed in 2015, the tower takes the form of nine twisted sections stacked atop each other, totaling 128 floors.[30] It is featured in its double-skin facade design, which eliminates the need for either layer to be opaqued for reflectivity as the double-layer structure has already reduced the heat absorption.[31] The futuristic-looking Oriental Pearl Tower, at 468 m (1,535 ft), is located nearby at the northern tip of Lujiazui.[32] Skyscrapers outside of Lujiazui include the White Magnolia Plaza in Hongkou, the Shimao International Plaza in Huangpu, and the Shanghai Wheelock Square in Jing'an.

-

The Shanghai Museum

-

The Shanghai Exhibition Center, an example of Stalinist architecture

-

The Oriental Pearl Tower at night

-

The Shanghai Tower

Museums

[edit]

Cultural curation in Shanghai has seen significant growth since 2013, with several new museums having been opened in the city.[33] This is in part due to the city's most recently released city development plans, with aims in making the city "an excellent global city".[34] As such, Shanghai has several museums[35] of regional and national importance.[36] The Shanghai Museum has one of the best collections of Chinese historical artifacts in the world, including a large collection of ancient Chinese bronzes. The China Art Museum, located in the former China Pavilion of Expo 2010, is the largest art museum in Asia. Power Station of Art is built in a converted power station, similar to London's Tate Modern. The Shanghai Natural History Museum and the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum are major natural history and science museums. In addition, there is a variety of smaller, specialist museums housed in important archaeological and historical sites such as the Songze Museum, the Museum of the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, the site of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, the former Ohel Moshe Synagogue (Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum), and the General Post Office Building (Shanghai Postal Museum). The Rockbund Art Museum is also in Shanghai. There are also many art galleries, concentrated in the M50 Art District and Tianzifang. Shanghai is also home to one of China's largest aquariums, the Shanghai Ocean Aquarium. MoCA, Museum of Contemporary Art of Shanghai, is a private museum centrally located in People's Park on West Nanjing Road, and is committed to promote contemporary art and design.

Visual arts

[edit]

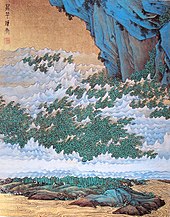

The Songjiang School (淞江派), containing the Huating School (华亭派) founded by Gu Zhengyi,[37] was a small painting school in Shanghai during the Ming and the Qing Dynasty.[38] It was represented by Dong Qichang.[39] The school was considered as a further development of the Wu School in Suzhou, the cultural center of the Jiangnan region at the time.[40]

In the mid 19th century, the Shanghai School movement commenced, focusing less on the symbolism emphasized by the Literati style but more on the visual content of the painting through the use of bright colors. Secular objects like flowers and birds were often selected as themes.[41] Western art was introduced to Shanghai in 1847 by Spanish missionary Joannes Ferrer (范廷佐), and the city's first western atelier was established in 1864 inside the Tushanwan orphanage.[42] During the Republic of China, many famous artists including Zhang Daqian, Liu Haisu, Xu Beihong, Feng Zikai and Yan Wenliang settled in Shanghai thus it gradually became the art center of China. Various art forms—photography, wood carving, sculpture, comics (Manhua) and Lianhuanhua—thrived. Sanmao, one of the most well-known comics in China, was created then to dramatize the chaos brought to society by the Second Sino-Japanese War.[43]

Today, the most comprehensive art and cultural facility in Shanghai is the China Art Museum. In addition, the Chinese painting academy features the Guohua,[44] while the Power Station of Art plays an important role in the contemporary art.[45] First held in 1996, the Shanghai Biennale has now become an important place for Chinese and foreign arts to interact.[46]

Performing arts

[edit]

Traditional Xiqu became the main way of entertainment for the public in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, monologue and burlesque in Shanghainese appeared in Shanghai, absorbing elements from traditional dramas. The Great World opened in 1912 is a significant stage at the time.[47]

In 1920s, Pingtan expanded from Suzhou to Shanghai.[48] With the abundant commercial radio stations, Pingtan art developed rapidly to 103 programs every day by the 1930s. At the same time, Shanghai also formed a Shanghai-style Beijing Opera led by Zhou Xinfang and Gai Jiaotian, and attracted many Xiqu masters like Mei Lanfang to the city.[49] At the same time, a small troupe from Shengxian (now Shengzhou) also began to promote Yue opera on the Shanghainese stage.[50] A unique style of opera, Shanghai opera, is formed when the local folksongs collided with modern operas.[51] As of 2012, the well-known Xiqu troupes in Shanghai include Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company, Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe, Shanghai Yue Opera House and Shanghai Huju Opera House.[52]

Drama appeared in missionary schools in Shanghai in the late 19th century. Back then, it was mainly performed in English. Scandals in Officialdom (官场丑史), staged in 1899, was one of the earliest recorded plays.[53] In 1907, Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly (黑奴吁天录) was performed at the Lyceum Theatre.[54] After the New Culture Movement, drama had become a popular way for students and intellectuals to express their views.

Numerous influential musicals and operas have taken place in Shanghai, including Les Misérables, Cats[55] and La bohème by Giacomo Puccini.[56] Many dramas and stage plays set in Shanghai too, for example, The Bund series produced by TVB and Secret Love for the Peach Blossom Spring directed by Stan Lai.[57]

Shanghai Conservatory of Music, Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, Shanghai Opera House and Shanghai Theatre Academy are four major institutes of theater training in Shanghai. Notable theaters in Shanghai include the Shanghai Grand Theatre, the Oriental Art Center and the People's Theatre.

Cinema

[edit]

Shanghai was the birthplace of Chinese cinema[58] and theater. China's first short film, The Difficult Couple (1913), and the country's first fictional feature film, An Orphan Rescues His Grandfather (孤儿救祖记, 1923) were both produced in Shanghai. These two films were very influential, and established Shanghai as the center of Chinese film-making. Shanghai's film industry went on to blossom during the early 1930s, generating great stars such as Hu Die, Ruan Lingyu, Zhou Xuan, Jin Yan, and Zhao Dan. Another film star, Jiang Qing, went on to become Madame Mao Zedong. The exile of Shanghainese filmmakers and actors as a result of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Communist revolution contributed enormously to the development of the Hong Kong film industry.[59] Many aspects of Shanghainese popular culture ("Shanghainese Pops") were transferred to Hong Kong by the Shanghainese emigrants and refugees after the Communist Revolution. The movie In the Mood for Love directed by Wong Kar-wai, a native Shanghainese, depicts a slice of the displaced Shanghainese community in Hong Kong[60] and the nostalgia for that era, featuring 1940s music by Zhou Xuan.

Fashion

[edit]

Other Shanghainese cultural artifacts include the cheongsam (Shanghainese: zansae), a modernization of the traditional Manchurian qipao. This contrasts sharply with the traditional qipao, which was designed to conceal the figure and be worn regardless of age. The cheongsam went along well with the western overcoat and the scarf, and portrayed a unique East Asian modernity, epitomizing the Shanghainese population in general. As Western fashions changed, the basic cheongsam design changed, too, introducing high-neck sleeveless dresses, bell-like sleeves, and the black lace frothing at the hem of a ball gown. By the 1940s, cheongsams came in transparent black, beaded bodices, matching capes and even velvet. Later, checked fabrics became also quite common. The 1949 Communist Revolution ended the cheongsam and other fashions in Shanghai. However, the Shanghainese styles have seen a recent revival as stylish party dresses. The fashion industry has been rapidly revitalizing in the past decade. Like Shanghai's architecture, local fashion designers strive to create a fusion of western and traditional designs, often with innovative if controversial results.

Since 2001, Shanghai has held its own fashion week called Shanghai Fashion Week. It is held twice every year in April and October. The April session is a part of the Shanghai International Fashion Culture Festival, which usually lasts for a month, while Shanghai Fashion Week lasts for seven days, and the main venue is in Fuxing Park, Shanghai, while the opening and closing ceremony is in Shanghai Fashion Center.[61] Supported by the People's Republic Ministry of Commerce, Shanghai Fashion Week is a major business and culture event of national significance hosted by the Shanghai Municipal Government. Shanghai Fashion Week is aiming to build up an international and professional platform, gathering all of the top design talents of Asia. The event features international designers but the primary purpose is to showcase Chinese designers.[62] The international presence has included many of the most promising young British fashion designers.[63]

LGBT

[edit]Shanghai has a thriving LGBT community with gay bars and LGBTQIA+ institutions. Fudan University is the first university in mainland China to offer courses on LGBT studies in 2005.[64] Shanghai Pride, first held in 2009 as the first mass LGBT event in mainland China, is held in the city annually in June.[65]

Sports

[edit]

Shanghai is home to several soccer teams, including two in the Chinese Super League: Shanghai Greenland Shenhua F.C. and Shanghai SIPG F.C. Another professional team, Shanghai Shenxin F.C., is currently in China League One. China's top-tier basketball team, the Shanghai Sharks of the Chinese Basketball Association, developed Yao Ming before he entered the NBA. Shanghai also has an ice hockey team, China Dragon, and a baseball team, the Shanghai Golden Eagles, which plays in the China Baseball League.

The Shanghai Cricket Club is a cricket club based in Shanghai. The club dates back to 1858 when the first recorded cricket match was played between a team of British Naval officers and a Shanghai 11. Following a 45-year dormancy after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the club was re-established in 1994 by expatriates living in the city and has since grown to over 300 members. The Shanghai cricket team was a cricket team that played various international matches between 1866 and 1948. With cricket in the rest of China almost non-existent, for that period they were the de facto Chinese national side.[66]

Shanghai is home to many prominent Chinese professional athletes, such as basketball player Yao Ming, 110-meter hurdler Liu Xiang, table tennis player Wang Liqin, and badminton player Wang Yihan.

Shanghai is the annual host of several international sports events. Since 2004, it has hosted the annual Chinese Grand Prix, a round of the Formula One World Championship. The race is staged annually at the Shanghai International Circuit.[67] It hosted the 1000th Formula One race on 14 April 2019. In 2010, Shanghai also became the host city of Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters (DTM), which raced in a street circuit in Pudong. In 2012, Shanghai started to host 6 Hours of Shanghai as one round from the inaugural season of the FIA World Endurance Championship. The city also hosts the Shanghai Masters tennis tournament, which is part of ATP World Tour Masters 1000, as well as golf tournaments including the BMW Masters and WGC-HSBC Champions.[68]

On 21 September 2017, Shanghai hosted a National Hockey League (NHL) ice hockey exhibition game in an effort to increase fan interest for the 2017–18 NHL season.[69]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Shanghainese romanization: longdhang; Wu Chinese pronunciation: [lòŋdɑ̃́][24]

References

[edit]- ^ "Shanghai-style Culture". Top China Travel. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Sahr Johnny, "Cybercity – Sahr Johnny's Shanghai Dream" That's Shanghai, October 2005; quoted online by [1] Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Blagden, Natalee; Bremner, Jade; Holland, Peter; Schmitt, Kelly; Beaton, Jessica (July 12, 2017). "50 Reasons Why Shanghai is the World's Greatest City". CNN. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ (七)上海市民语言应用能力调查 (in Chinese). Shanghai Municipal Government. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Chinese languages". britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Chen, Zhongmin. 上海市区话语音一百多年来的演变 [Changes in the downtown Shanghainese pronunciations in the past one hundred years] (in Chinese). p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ You, Rujie (16 October 2018). “上海闲话”和“本地闲话”为何差别这么大?. Shanghai Observer. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Zat Liu (20 August 2010). "Is Shanghai's local dialect, and culture, in crisis?". CNN GO. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Jia Feishang (13 May 2011). "Stopping the local dialect becoming derelict". Shanghai Daily. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "A Brief Intro to Shanghai "Hu" Cuisine". theculturetrip.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ shanghailander. 正宗的上海生煎馒头在哪里?. moment.douban.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "The That's Guide to Gorging on Shanghai Hairy Crab". www.thatsmags.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ 名家名菜—松鼠鳜鱼. home.meishichina.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ 上海糖醋小排. www.meishij.net. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ 一百个上海人有一百种罗宋汤 [One hundred types of borscht for one hundred Shanghainese]. 新浪网. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ a b Loh, Juliana (16 February 2016). "An art deco journey through Shanghai's belle époque". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Shanghai Architectural History". shanghaiguide.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Kabos, Ladislav. "The man who changed Shanghai". Who is L.E.Hudec. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Jin, Zhihao (12 July 2011). 一个外国建筑设计师的上海传奇----邬达克和他设计的经典老房子 (in Chinese (China)). Shanghai Archives Bureau. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "FAIRMONT PEACE HOTEL – A HISTORY". Accor. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Strolling Shanghai's Bund (Part 2)". EVERETT POTTER'S TRAVEL REPORT. 13 August 2018. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Bigger and better: The Shanghai Bund is back – CNN Travel". cnngo.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b Goldberger, Paul (2005-12-26). "Shanghai Surprise: The radical quaintness of the Xintiandi district". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Qian, Nairong (2007). 上海话大词典. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. ISBN 9787532622481.

- ^ "Shikumen Residence". www.travelchinaguide.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Mo, Yan (18 January 2010). 文汇报:从石库门走入上海城市文化. Wenhui Bao (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Lonely Planet review for Shanghai Exhibition Centre". Lonely Planet. NC2 Media. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Number of 150m+ Completed Buildings – The Skyscraper Center". Skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Alfred Joyner. "Shanghai Tower: Asia's new tallest skyscraper presents a future vision of 'vertical cities'". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Shanghai Tower News Release" (PDF). Gensler. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ CleanTechies (25 March 2010). "The Shanghai Tower: The Beginnings of a Green Revolution in China". Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Culture of Shanghai". SkyscraperPage.

- ^ "3 New Museums to Look Out for in 2018". Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ hermesauto (5 January 2018). "Shanghai releases blueprint for becoming global cosmopolis by 2035". Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Museums in Shanghai". www.shanghaitourmap.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Museums in Shanghai – SmartShanghai". www.smartshanghai.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ 崔庆国 (9 April 2009). 松江画派:价格与地位不符. 《鉴宝》 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ 上海通志>>第三十八卷文化艺术(上)>>第六章美术、书法、摄影>>节 (in Chinese). Office of Shanghai Chronicles. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 《上海地方志》>>1989年第五期>>"松江画派"源流 (in Chinese). Office of Shanghai Chronicles. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 單國霖 (May 2005). 董其昌與松江畫派 (PDF). www.mam.gov.mo (in Chinese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ 海上画派的艺术特点及对后世的影响. www.sohu.com (in Chinese). 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ 171年前一个西班牙人来到上海,西洋绘画由此传播开来. www.sohu.com (in Chinese). 17 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "三毛"最早诞生于1935年7月28日《晨报》副刊 (in Chinese). 解放日报. 29 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 上海中国画院 (in Chinese). 今日艺术. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ 钱雪儿 (22 November 2018). 特稿|11月的上海,何以成为全球最热的当代艺术地标 (in Chinese). THE PAPER. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ 钱雪儿 (10 November 2018). 现场|第12届上海双年展开幕:进退之间,无序或矛盾 (in Chinese). THE PAPER. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ 王无能. 易文网. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 历史上的今天 3月2日. 中国网. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 梅兰芳的几次出国演出(附图). 上海档案信息网. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 怀想当年"越剧十姐妹"绍兴将共演《山河恋》. 搜狐娱乐. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Stock, Jonathan (2003). Huju: Traditional Opera in modern Shanghai. Oxford ; New York : Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. ISBN 0197262732.

- ^ 所属院团. 上海戏曲艺术中心. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ 剧变沧桑:第1集 舞台西洋风. 文明网. 21 February 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 话剧百年 "兰心"之韵 (in Chinese). 城市经济导报. 11 March 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ 经典音乐剧《猫》3月28日大剧院首演. 新浪上海. 25 February 2003. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ 从《阿蒂拉》上演看意大利歌剧在上海. Wenhui Bao. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ William Peterson (12 November 2018). "Worlds and theatre collide in Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Group, SEEC Media. "Shanghai Film Museum". timeoutshanghai.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ 上海电影对香港电影的影响 [The influence of Shanghai film on Hong Kong film]. 香港电影论文 (in Chinese). 31 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Setting His Tale Of Love Found In a City Long Lost". The New York Times. 28 January 2001. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ 历届回顾 COLLECTION. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Photos of Shanghai Fashion Week – Scene Asia – Scene Asia – WSJ". The Wall Street Journal. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Leisa Barnett (27 October 2008). "Aminaka Wilmont to show in Shanghai (Vogue.com UK)". Vogue.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ "Shanghai University to Offer China’s First Program In Gay Culture Archived 2014-09-23 at the Wayback Machine" (Archive). Associated Press at Diverse Education. September 8, 2005. Retrieved on September 26, 2014.

- ^ "China Comes Out With First Gay Pride". On Top Magazine. 6 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ "About the Shanghai Cricket Club". Shanghai Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Grand Prix Shanghai Set to Go". China.org.cn. 22 October 2002. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ "European Tour, CGA unveil BMW Masters". China Daily. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "Kings defeat Canucks in shootout to sweep China Games". NHL. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

External links

[edit]- Falanitule, Dahvida (2018-06-02). "The key ingredients of Shanghai's unique haipai culture". Shanghai Daily.